Abstract

Healthy neurocognitive aging has been associated with the microstructural degradation of white matter pathways that connect distributed gray matter regions, assessed by diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). However, the relatively low spatial resolution of standard DWI has limited the examination of age-related differences in the properties of smaller, tightly curved white matter fibers, as well as the relatively more complex microstructure of gray matter. Here, we capitalize on high-resolution multi-shot DWI, which allows spatial resolutions < 1 mm3 to be achieved on clinical 3T MRI scanners. We assessed whether traditional diffusion tensor-based measures of gray matter microstructure and graph theoretical measures of white matter structural connectivity assessed by standard (1.5 mm3 voxels, 3.375 μl volume) and high-resolution (1 mm3 voxels, 1μl volume) DWI were differentially related to age and cognitive performance in 61 healthy adults 18-78 years of age. Cognitive performance was assessed using an extensive battery comprising 12 separate tests of fluid (speed-dependent) cognition. Results indicated that the high-resolution data had larger correlations between age and gray matter mean diffusivity, but smaller correlations between age and structural connectivity. Moreover, parallel mediation models including both standard and high-resolution measures revealed that only the high-resolution measures mediated age-related differences in fluid cognition. These results lay the groundwork for future studies planning to apply high-resolution DWI methodology to further assess the mechanisms of both healthy aging and cognitive impairment.

Keywords: fluid cognition, healthy aging, gray matter microstructure, white matter connectivity, graph theory

Healthy older adults exhibit decline in fluid cognitive abilities that require the rapid processing and integration of novel information, such as attention and memory (Park & Reuter-Lorenz, 2009; Salthouse, 1996; Salthouse & Madden, 2007). This type of normal age-related cognitive decline has been attributed, at least in part, to the microstructural degradation of the white matter connections between distributed gray matter (GM) regions (Bennett & Madden, 2014; Madden et al., 2017; O'Sullivan et al., 2001; Salat, 2011). White matter (WM) microstructure (e.g., axonal density, degree of myelination) and connectivity (i.e., the number of structural connections between GM regions) can be assessed noninvasively using diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), which is a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technique that is sensitive to the movement, or diffusion, of water molecules in neural tissue (Beaulieu, 2002; Jones, 2008; Mori & Zhang, 2006). However, standard in vivo whole-brain DWI acquisitions on 3T clinical MRI scanners typically require lower spatial resolution (~2 mm3 voxels) to achieve adequate signal-to-noise ratios (SNR; Anderson et al., 2020). This methodological limitation precludes the examination of connectivity in smaller WM regions and the relatively more complex microstructure of GM tissue (e.g., synaptic density, dendritic arborization), both of which may help further explain age-related cognitive decline.

Estimates of brain microstructure are most often obtained by using the diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) model, which measures the degree of restricted water diffusion (i.e., fractional anisotropy, FA) and rate of water diffusion (i.e., mean diffusivity, MD) in each voxel. DTI is well-suited for studying WM microstructure, even using standard DWI data, because the microstructural properties of these large, highly aligned fiber bundles restrict the molecular movement of water such that the primary direction of water diffusion runs parallel, rather than perpendicular, to the length of a WM pathway, resulting in high FA and low MD (Beaulieu, 2002). As age increases, water diffusion becomes less restricted as WM microstructure begins to deteriorate (e.g., axonal shrinkage, demyelination), leading to diffusion in multiple directions and lower FA/higher MD (Bennett & Madden, 2014; Madden et al., 2012). DTI has also occasionally been applied to study GM microstructure (for a review, see Assaf, 2019) and how it varies in aging (Abe et al., 2008; Bhagat & Beaulieu, 2004). But in contrast to the highly aligned nature of most WM fiber bundles, GM is comprised of distinct layers with more heterogenous microstructural properties that cannot be summarized as well by a single tensor, at least in standard DWI data (Assaf, 2019). High-resolution DWI data may provide more precise tensor-based estimates of GM microstructure in aging by permitting tensor fitting within smaller voxels, and therefore smaller subsets of GM tissue, and by decreasing partial volume effects (i.e., voxels that include both WM and GM tissue or are contaminated by cerebrospinal fluid [CSF]).

In addition to GM microstructure, complementary measures of WM structural connectivity between GM regions may help explain age-related differences in fluid cognition (e.g., Fjell et al., 2017; Hall et al., 2022). Age-related differences in structural connectivity can be assessed using graph theory (Hagmann et al., 2008; Rubinov & Sporns, 2010), which is a mathematical model that partitions the brain into networks comprised of individual GM regions (nodes) and the WM connections between them (edges). Structural connectivity is then measured as the sum of the number of WM connections (i.e., tractography-based streamlines) between pairs of GM nodes. Increased age is associated with a decrease in the number of structural connections among nodes within individual networks and between nodes from different networks, suggesting that these networks become structurally separated in aging (Betzel et al., 2014; Madden et al., 2020). Relative to standard DWI data, however, high-resolution DWI data may distribute the termination of streamlines across the cortical ribbon more uniformly (Schilling et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2022) and track superficial WM fibers (i.e., u-fibers) with small diameters and high curvature more accurately (Guevara et al., 2020). Assessing these more fine-grained anatomical properties is important, because the microstructure (Wu et al., 2016) and volume (Schilling et al., 2023) of some superficial WM regions appear to be less affected by aging than the properties of long-range, deep WM tracts. Graph theory analyses of standard resolution DWI data, as in most previous studies, may thus provide biased estimates of age-related differences in structural connectivity.

There is already some evidence that high-resolution DWI can better resolve tensor-based estimations of GM microstructure than standard DWI (Chen et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2011; Vu et al., 2015), as a result of reduced partial volume effects in high-resolution DWI (Vu et al., 2015). A handful of studies have also demonstrated that high-resolution DWI improves the estimation of the structural connectome in rodents (Anderson et al., 2020; Crater et al., 2022), ex vivo human brains (Miller et al., 2011), and relatively small samples (n < 10) of healthy, younger human volunteers (Caiazzo et al., 2018; Chang et al., 2015). At least one study further demonstrated that high-resolution DWI measures of WM structural connectivity are related more closely to cognition in healthy younger adults, as compared to standard DWI measures (Mansour et al., 2021). In aging, poorer memory performance has been correlated with both WM structural connectivity of the medial temporal lobe (Granger et al., 2023) and GM microstructure of the hippocampus (Granger et al., 2022; Solar et al., 2021) using high-resolution DWI.

The goal of this study is to compare age-related differences in high-resolution and standard DWI measures of GM microstructure and WM structural connectivity, and their ability to explain differences in fluid cognitive performance across the adult lifespan (n = 61; ages 18-78 years). Fluid cognition was assessed using an extensive battery of 12 tests of perceptual-motor speed, executive function, and memory, as previously described (Howard et al., 2022; Madden et al., 2020; Merenstein et al., 2023). We acquired standard 1.5 mm3 resolution data using a DWI sequence in line with the human connectome project (HCP; Glasser et al., 2016; Harms et al., 2018) and high-resolution 1 mm3 data using a Multiplexed Sensitivity Encoding (MUSE) DWI sequence (Chen et al., 2013). MUSE achieves high spatial resolutions on 3T clinical MRI scanners by incorporating simultaneous multi-slice imaging and reverse polarity gradients between shots, resulting in a three-fold increase in resolution relative to the standard HCP-style DWI data and sufficiently high SNR.

If the high-resolution DWI data estimates GM microstructure and connectivity of small, tightly curved WM fibers more accurately than the standard DWI data, then the high-resolution data may exhibit significantly larger age-related differences in both GM microstructure and connectivity. Differences between the high-resolution and standard DWI sequences may be more apparent for MD than for FA, because FA represents the diffusion of water along a particular direction, for example as restricted by the axonal myelin sheath, which is less likely in GM tissue, where there are less uniform anatomical restrictions (Benedetti et al., 2006; Helenius et al., 2002). Finally, we conducted mediation analyses within the context of ordinary linear regression (Hayes & Rockwood, 2017) to compare the high-resolution and standard DWI measures in their ability to account for the age-related variance in fluid cognition. Regardless of their relations to age, we hypothesized that the high-resolution MUSE measures would be more tightly linked with behavior and would significantly mediate age-related differences in fluid cognition, beyond the effect of the standard DWI measures.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This study was conducted in compliance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans and with the Institutional Review Board for Duke University Medical Center. Each participant provided informed consent and was compensated for their participation.

Prior to enrolling in the study, all participants reported that they had completed at least a high school education and were free of major neurological (e.g., epilepsy, stroke) and medical (e.g., diabetes, emphysema, uncontrolled hypertension) conditions. Participation in the study involved an initial 2-hr. screening and psychometric testing session, followed by a 1.5-hr. MRI scan completed approximately one month later (median interval = 32 days). The screening session included the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975) to screen for general cognitive performance (score > 27), the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III vocabulary subtest (WAIS; Wechsler, 1997) to screen for general intelligence (score > 50th percentile), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, 1978) to screen for depression (score < 15), and the Freiburg Visual Acuity Test (FRACT; Bach, 1996) to screen for corrected visual acuity (Snellen score > 20/40).

Ninety-eight healthy, community-dwelling individuals between 18 and 84 years of age participated in the initial screening session. Of these participants, five were lost to follow up, nine scored below the cutoffs for the screening criteria, four did not meet MRI safety requirements (e.g., claustrophobia, body size, or metal implant), and two were outliers (> 3 standard deviations) on one or more of the cognitive tests (described below, Cognitive Data). The remaining 78 participants completed MRI scanning, but time constraints prohibited the acquisition of the high-resolution DWI data for seven individuals. Ten additional participants were excluded because of excessive head motion, MRI artifacts or image processing issues, or poor cognitive performance (accuracy < 75%) on a visual attention task completed during functional MRI (fMRI) scanning (Merenstein et al., 2023). Details on the final sample of 61 participants ages 18-78 years (52% female, 11% Hispanic, 82% White) are provided in Table 1. The age distribution of participants by decade is as follows: 18-30 years (n = 15), 30s (n = 10), 40s (n = 11), 50s (n = 6), 60s (n = 11), and 70s (n = 8). This sample is identical to that reported by the Merenstein et al. (2023) analysis of task-related fMRI activation (n = 68), except that, as noted previously, seven participants did not have high-resolution DWI data available.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Measure | Mean | (SD) | r with age |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education (years) | 17.336 | (2.429) | −0.027 |

| MMSE | 29.541 | (0.621) | 0.004 |

| BDI | 2.590 | (3.100) | 0.145 |

| Vocabulary | 58.344 | (4.604) | 0.007 |

| Color Vision | 13.869 | (0.499) | −0.239 |

| Corrected Visual Acuity | −0.010 | (0.087) | 0.393 |

Note. n = 61; values are presented as mean (standard deviation, SD); MMSE = score on the Mini-Mental State Exam (Folstein et al., 1975); BDI = score on the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck, 1978); Vocabulary = raw score on the vocabulary subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence (WAIS) Scale III (Wechsler, 1997); Color Vision = score on Dvorine color plates (Dvorine, 1963); Corrected Visual Acuity = logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (MAR), for the Freiburg Visual Acuity Test (Bach, 1996). A log MAR score of 0 corresponds to Snellen 20/20, with negative values indicating better resolution. Thus, the positive correlation for acuity represents age-related decline in this measure. Significant effects are presented in bold.

Cognitive Data

As previously described (Howard et al., 2022; Madden et al., 2020; Merenstein et al., 2023), cognitive performance was assessed using 12 computerized reaction time (RT), standardized psychometric, or National Institutes of Health (NIH) Toolbox (Gershon et al., 2013) tests. Four tests were administered for each of three domains of fluid cognition: perceptual-motor speed, executive function, and memory. Perceptual-motor speed was measured using a simple RT task, two versions of choice RT, and number correct in 85 s from the NIH Toolbox Pattern Comparison Test. Executive function was measured using two-choice digit symbol comparison RT, the flanker task (i.e., incompatible RT divided by compatible RT), the Trail Making Test (i.e., Trails B minus Trails A; Reitan, 1971), and the computed score from the NIH Toolbox Dimensional Change Card Sort Test. Memory was measured using a non-verbal working memory task (Saults & Cowan, 2007), 20-min delayed recall of 16 words, the WAIS logical memory test (Wechsler, 1997), and the computed score from the NIH Toolbox Picture Sequence Memory Test. We used the unrotated first factor from a factor analysis of all 12 tests as a measure of general fluid cognition, and the first factor from each set of four tests for perceptual-motor speed, executive function, and memory as indicators of these domains (Hedden et al., 2016; Hedden et al., 2012; Madden et al., 2020; Madden et al., 2017; Salthouse et al., 2015).

Imaging Data Acquisition

The imaging data were acquired at Duke University Medical Center on a 3T GE Signa Ultra High Performance whole-body 60 cm bore MRI scanner (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) equipped with a 48 channel receive-only head coil. Participants wore earplugs to reduce scanner noise, and foam pads were used to minimize head motion.

A high-resolution T1-weighted image was acquired using a 3D fast inverse-recovery-prepared spoiled gradient recalled (SPGR) sequence with the following parameters: 292 straight axial slices, repetition time (TR) = 2203.5 ms, echo time (TE) = 3.076 ms, inversion recovery time = 900 ms, field of view (FOV) = 240 x 240 mm, flip angle = 8°, voxel size = 0.50 x 0.47 x 0.47 mm, acquisition matrix = 512 x 512 mm, and sensitivity encoding (SENSE) factor = 2.

Whole-brain standard resolution HCP-style (Glasser et al., 2016; Harms et al., 2018) DWI data were acquired using a single-shot spin-echo echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence with the following parameters: 92 contiguous slices, TR = 4894 ms, TE = 64.7 ms, FOV = 220 x 220 mm, flip angle = 90°, voxel size = 1.5 mm3, acquisition matrix = 144 x 144 mm, multiband factor = 3, and SENSE factor = 1. Diffusion-weighted gradients were applied in 90 directions with b values of 1500 s/mm2 and 3000 s/mm2 and with two non-diffusion-weighted b = 0 images. For 54 of the 61 participants, a second diffusion sequence was acquired with six phase-encoding directions of opposite polarity using identical parameters, except that TR = 5260 ms.

Whole-brain high-resolution DWI data were acquired using a four-shot Multiplexed Sensitivity Encoding (MUSE) spin-echo EPI sequence (Chen et al., 2013) with the following parameters: 90 contiguous slices, TR = 10000 ms, TE = 60.8 ms, FOV = 256 x 256 mm, flip angle = 90°, voxel size = 1 mm3, acquisition matrix = 256 x 256 mm, multiband factor = 1, and SENSE factor = 3. Diffusion-weighted gradients were applied in 15 directions with a b value of 1000 s/mm2 and with three non-diffusion-weighted b = 0 images.

During scanning, we also acquired resting-state fMRI, task-related fMRI (Merenstein et al., 2023), susceptibility-weighted angiography (Howard et al., 2022), and fluid attenuated inversion recovery imaging, to be reported separately.

DWI Processing

We processed the raw DWI data using MRtrix3 (Tournier et al., 2019) and FSL (FMRIB's Software Library; Smith et al., 2004). The data were first denoised (dwidenoise) and then corrected for motion and eddy current-induced distortions (dwifslpreproc). The standard HCP-style data were additionally corrected for susceptibility-induced off-resonance distortions for the 54 participants with reverse polarity data available (topup). During acquisition of the MUSE data, susceptibility-induced off-resonance distortions were estimated by incorporating reverse polarity gradients between shots, which allowed for distortion correction to instead be completed during image reconstruction. Lastly, all data were bias-corrected (dwibiascorrect) and non-brain tissue was removed to generate a whole-brain mask (dwi2mask).

All processed DWI scans were visually inspected and found acceptable for the degree of brain mask coverage, quality of motion and susceptibility-induced distortion corrections, the presence of MR artifacts (e.g., ghosting, radio frequency inhomogeneities), and anatomical abnormalities. We also calculated the average SNR for each sequence by estimating the level of noise across all volumes (dwidenoise) and then dividing this estimate by the mean intensity values in the average skull-stripped, preprocessed b = 0 image. Both the standard (mean = 43.920 ± standard error = 0.830) and high-resolution (30.059 ± 0.544) data exhibited sufficiently high SNR levels (Bastiani et al., 2019; Edelstein et al., 1986). However, the SNR was significantly higher for the standard data, t(60) = 3.709, p < 0.001, which was expected because SNR decreases as voxel size decreases (Uğurbil et al., 2013).

Microstructure Measures

To assess GM microstructure, we created anatomical masks of standard GM networks defined from resting-state fMRI data in an independent sample of 1,000 healthy younger adults (Yeo et al., 2011). The masks were created using nodes from the Brainnetome atlas (Fan et al., 2016) in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 152 template space (1 mm3 resolution). The Brainnetome atlas includes 210 cortical, 36 subcortical, and 28 cerebellar nodes, but we excluded the 28 cerebellar nodes and 12 cortical nodes (located primarily within the inferior temporal lobe) due to incomplete spatial coverage in the high-resolution data for > 50% of participants. The 198 remaining cortical nodes were combined into separate binary masks depending on which of the seven cortical networks they belonged to: dorsal attention, default mode, frontoparietal, limbic, sensorimotor, ventral attention, and visual networks (Yeo et al., 2011). The 36 subcortical nodes were combined into one subcortical network mask, similar to prior work (Capogna et al., 2022; Luo et al., 2020). The same node to network assignments were used for the estimation of structural connectivity (see Structural Connectivity).

To mitigate partial volume effects, especially in the standard HCP-style data, each network mask was eroded by a 1 mm kernel (fslmaths). For each participant, the standard space masks were then aligned to native diffusion space using the following registration steps (Glenn et al., 2022; Merenstein et al., 2022): (1) aligning the T1-weighted image to the standard MNI 152 1 mm3 template image using an affine transformation with 12 degrees of freedom; (2) aligning the mean b = 0 diffusion image to the T1-weighted image using a boundary-based registration with six degrees of freedom; (3) concatenating the diffusion-T1 and T1-MNI transformations; (4) inverting this concatenated transformation; and (5) applying the inverted transformation to align the standard masks to native diffusion space. Visual inspections deemed the quality of alignments and degree of coverage to be acceptable for each GM mask.

For each participant and DWI sequence, we estimated a single diffusion tensor for each voxel using the whole-brain mask to limit tensor fitting to brain tissue (dwi2tensor). From the tensor fitting output, we generated voxel-wise diffusion maps for FA and MD (tensor2metric). We then separately multiplied each of the GM masks in native diffusion space by each voxel-wise diffusion map (FA or MD) and averaged the values across voxels in that mask (fslstats). We also created global measures of microstructure by averaging FA or MD values across the eight masks.

For the analyses reported in the main text, tensor fitting was performed using data from both b-values in the standard resolution data. However, higher b-values are more sensitive to hindered and restricted sources of diffusion (Assaf & Basser, 2005; Assaf et al., 2004) and may confound comparisons between the DTI metrics of interest. Stronger b-values (beyond 1500 s/mm2) also result in a pattern of diffusion-weighted signal decay that deviates from the assumptions central to the gaussian DTI model (Mulkern et al., 1999; Steven et al., 2013). To assess the potential impact of b-value on differences in FA and MD between sequences (Assaf & Basser, 2005; Assaf et al., 2004; Mulkern et al., 1999; Steven et al., 2013), we also report findings from analyses limited to the b = 1500 s/mm2 shell in the Supplementary Material.

Structural Connectivity

To assess structural connectivity, we derived fiber orientation distribution (FOD) maps using multi-shell, multi-tissue constrained spherical deconvolution (MSMT-CSD; Jeurissen et al., 2014; Tournier et al., 2019; Tournier et al., 2004), which was based on the dhollander tissue-specific response function from three compartments (GM, WM, CSF) in the multi-shell HCP-style data or two compartments (WM, CSF) in the single-shell MUSE data (Dhollander et al., 2019). Note that CSD in the MUSE data was based on 15 diffusion-weighted directions, which falls below the recommended 30+ direction minimum for CSD (Tournier et al., 2004). However, previous studies using high-resolution MUSE data have demonstrated its improved ability to resolve crossing fiber populations with as few as 12 diffusion-weighted directions (Bruce et al., 2017). In addition to higher angular resolution, MSMT-CSD performs most optimally on multi-shell DWI data, but this simplified version of MSMT-CSD is still suitable for single-shell data, as long as b = 0 s/mm2 volumes are available (Jeurissen et al., 2014). Specifically, because the MUSE data still include two “shells”, we can estimate two compartments (WM, CSF) and achieve similar advantages to those obtained by free water elimination (Jeurissen et al., 2014). For each sequence, we provide a sample FOD map for a representative participant in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Sample fiber orientation distribution (FOD) maps. Example FOD maps are provided for the (A) high-resolution and (B) standard resolution data acquired from a representative 44-year-old (median age of sample) female participant, with a yellow inset figure zooming in on genu of the corpus callosum and adjacent WM regions. The FOD maps were derived from two compartments (WM, CSF) in the high-resolution data or three compartments (WM, GM, CSF) in the standard resolution data.

Next, a GM/WM boundary mask was generated from the high-resolution T1-weighted image (5ttgen; Smith et al., 2012; Tournier et al., 2019). For each DWI sequence, we registered the average skull-stripped, preprocessed b = 0 image to the GM/WM boundary mask using a linear registration with six degrees of freedom (flirt; Jenkinson et al., 2002; Jenkinson & Smith, 2001; Smith et al., 2004) and then applied the inverse of this transformation matrix to register the GM/WM boundary mask to native diffusion space (transformconvert, mrtransform). Using the FOD maps, we performed anatomically constrained probabilistic tractography (ACT; Smith et al., 2012), which limits the extent of streamline propagation and ensures proper termination of streamlines in the GM/WM boundary mask. We set the minimum streamline length to 1 mm, maximum streamline length to 250 mm, and FA cutoff to 0.06. For each participant and DWI sequence, we generated 10 million tracts (tckgen) and used spherical-deconvolution informed filtering of tractograms 2 (tcksift2) in MRtrix (Smith et al., 2015) to assign a weight to each streamline, relative to the underlying apparent fiber density. Incorporating the weighted contribution of all streamlines to the spherical deconvolution diffusion model, rather than removing them (Smith et al., 2013), produces a more biologically meaningful representation of WM tracts (Smith et al., 2015).

For each participant and DWI sequence, we transformed the resulting streamlines in native diffusion space to standard MNI 152 1 mm3 space (tcktransform). Symmetrical structural connectivity matrices were created by assigning the 10 million weighted streamlines to the 198 cortical and 36 subcortical nodes from the Brainnetome Atlas (Fan et al., 2016) with sufficient spatial coverage (tck2connectome). The endpoint of each streamline was assigned to the nearest GM node using a 2 mm radial search (Smith et al., 2015). In the resulting 234 x 234 matrices, each cell represents the sum of the weighted contribution of the streamlines connecting that pair of nodes, scaled to account for differences in node volume (Hagmann et al., 2008; Tournier et al., 2019). As recommended by Civier et al. (2019), we did not threshold the matrices to remove cells with few or no connections assigned to them. For each sequence, a sample connectivity matrix for a representative participant is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Sample connectivity matrices. For the (A) high-resolution and (B) standard resolution data, a 234 x 234 matrix, sorted by network, illustrates the number of estimated streamlines (adjusted for size of the gray matter node) for a 44-year-old (median age of sample) female participant. The matrix is color-coded such that warmer colors indicate higher connections and cooler colors indicate fewer or no connections. As expected, connectivity was highest within networks relative to between networks, and the high-resolution data estimated more connections than the standard resolution data (more warm colors). Networks are abbreviated as dorsal attention (DAN), default mode (DMN), frontoparietal (FPN), limbic (LMB), sensorimotor (SMN), subcortical (SUB), ventral attention (VAN), and visual (VIS).

In the final step, we used the Brain Connectivity Toolbox (Rubinov & Sporns, 2010) to estimate graph theory measures of within-network connectivity (i.e., mean connectivity strength among nodes from one network) and between-network connectivity (i.e., mean connectivity strength between nodes from one network and all nodes outside of that network). Networks were defined using the seven cortical networks (Yeo et al., 2011) and eighth subcortical network that were used to extract GM microstructure. We calculated within- and between-network connectivity separately for each of the eight networks and created a global measure by averaging connectivity values across networks.

Results

Cognitive Performance

To assess age-related differences in cognition, we created standardized residuals of each factor score (general fluid cognition, perceptual-motor speed, executive function, memory) after regressing out WAIS vocabulary scores and dummy-coded sex. For the individual domain scores, we additionally regressed out performance on the two factor scores outside of that domain. Using Pearson correlations with false discovery rate (FDR) procedures (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995) to correct for four comparisons, we found that age was negatively related to general fluid cognition performance, r = −0.860, pFDR < 0.001, but not significantly related to the residual individual domain scores, r ≤ −0.258, pFDR ≥ 0.134 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Age-related differences in cognitive performance. General fluid cognition was measured using a factor score from 12 reaction time and psychometric tests of perceptual-motor speed, executive function, and memory. Perceptual-motor speed, executive function, and memory were each measured using a factor score from the four tests within that domain. All correlations were covaried for sex and WAIS vocabulary scores, and the individual domain correlations were additionally covaried for performance on the other two domains. Following false discovery rate (FDR) correction, significant age-related decline was evident only in the general fluid cognition measure. The shaded gray area around the regression line represents 95% confidence intervals.

Although the number of years of education completed was not significantly related to fluid cognition in this sample, r = 0.091, p = 0.488, there is some evidence that higher educational attainment is associated with higher cognitive functioning in aging (e.g., Tucker & Stern, 2011). However, after repeating the correlations between cognition and age using years of education completed as an additional covariate, the strength of the correlations did not change for fluid cognition, r = −0.862, pFDR < 0.001, or the individual domains, r ≤ −0.261, pFDR ≥ 0.127.

Comparison of DWI Sequences

To determine whether the high-resolution and standard DWI data differed in their estimates of GM microstructure (FA, MD) and WM structural connectivity (within-network, between-network), and whether these estimates varied anatomically, we conducted separate repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) for each outcome measure with Sequence (standard, high-resolution) and Network (eight networks) as within-subject variables. Significant main effects and interactions were probed using post hoc t-tests with the Holm-Bonferroni method applied for multiple comparison correction. For brevity, the post hoc tests for the omnibus main effect of Network are provided in the Supplementary Material (Tables S1-S4).

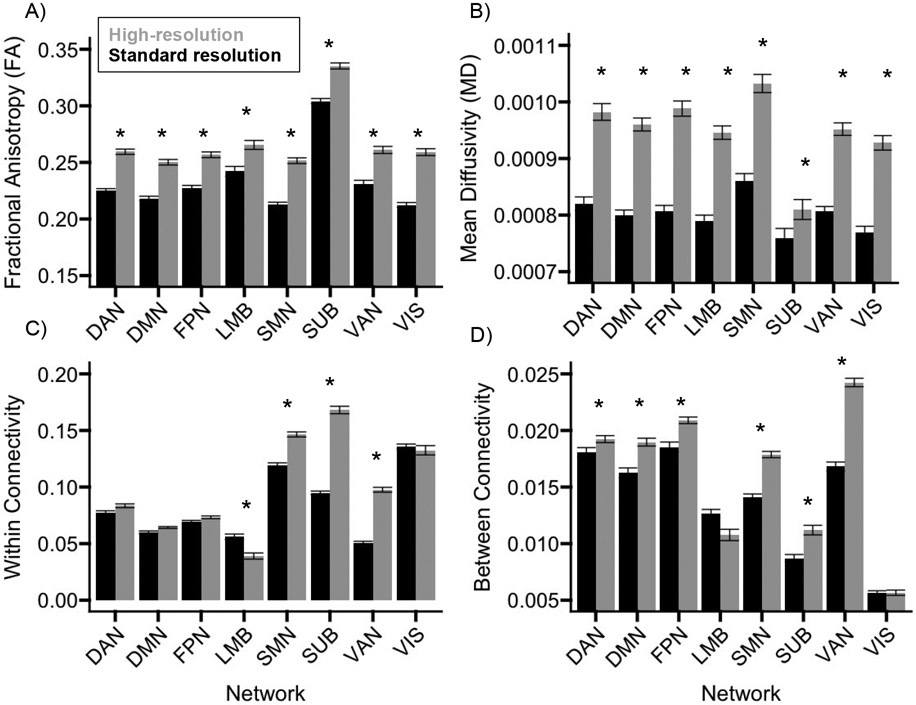

For GM FA, there was a significant main effect of Sequence, F(1, 60) = 272.119, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.819, indicating that FA was higher for the high-resolution (mean = 0.267 ± standard error = 0.004) than the standard (mean = 0.234 ± 0.004) sequence, and Network, F(7, 420) = 266.923, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.816, indicating that FA varied anatomically (Figure 2A and Table S1). A significant Sequence x Network interaction, F(7, 420) = 11.785 p < 0.001, η2p = 0.164, indicated that the difference in FA between sequences was significant in all networks, t(60) ≥ 8.463, p < 0.001, but largest in the subcortical network (difference = 0.047 ± 0.003) and smallest in the ventral attention network (difference = 0.023 ± 0.003; Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Comparison of measures between sequences. For each network, bar graphs display gray matter fractional anisotropy (A) or mean diffusivity (B), and white matter within-network (C) or between-network (D) structural connectivity, separately for the high-resolution (black) or standard resolution (gray) sequence. Networks are abbreviated as dorsal attention (DAN), default mode (DMN), frontoparietal (FPN), limbic (LMB), sensorimotor (SMN), subcortical (SUB), ventral attention (VAN), and visual (VIS). * Holm-Bonferroni p < 0.05. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

For GM MD, there was a significant main effect of Sequence, F(1, 60) = 1478.006, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.961, indicating that MD was higher for the high-resolution (mean = 9.50e-4 ± 1.22e-5) than standard (mean = 7.99e-4 ± 1.23e-5) sequence, and Network, F(7, 420) = 54.549, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.476, indicating that MD varied anatomically (Figure 2B and Table S2). A significant Sequence x Network interaction, F(7, 420) = 81.072, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.575, indicated that the difference in MD between sequences was significant in all networks, t(60) ≥ 8.790, p < 0.001, but was largest in the dorsal attention network (difference = 1.82e-4 ± 5.75e-6) and smallest in the frontoparietal network (difference = 5.05e-5 ± 5.75e-6; Figure 4B).

For within-network connectivity, there was a significant main effect of Sequence, F(1, 60) = 515.739, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.896, indicating that connectivity was higher for the high-resolution (mean = 0.101 ± 0.006) than standard (mean = 0.083 ± 0.004) sequence, and Network, F(7, 420) = 494.432, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.892, indicating that connectivity varied anatomically (Figure 2C). A significant Sequence x Network interaction, F(7, 420) = 81.072, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.575, indicated that connectivity differed between sequences in the sensorimotor (difference = 0.028 ± 0.002), ventral attention (difference = 0.046 ± 0.002), limbic (difference = 0.017 ± 0.002), and subcortical (difference = 0.074 ± 0.002) networks, t(60) ≥ 6.937, p < 0.001, but not the dorsal attention, frontoparietal, default mode, or visual networks, p ≥ 0.084 (Figure 4C and Table S3).

For between-network connectivity, there was a significant main effect of Sequence, F(1, 60) = 64.142, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.517, indicating that connectivity was higher for the high-resolution (mean = 0.016 ± 0.008) than standard (mean = 0.014 ± 0.007) sequence, and Network, F(7, 420) = 338.945, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.850, indicating that connectivity varied anatomically (Figure 2D). A significant Sequence x Network interaction, F(7, 420) = 25.069, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.295, indicated that connectivity differed between sequences in the sensorimotor (difference = 0.005 ± 5.77e-4), dorsal attention (difference = 0.002 ± 5.773e-4), ventral attention (difference = 0.007 ± 5.77e-4), frontoparietal (difference = 0.002 ± 5.77e-4), default mode (difference = 0.003 ± 5.77e-4), and subcortical (difference = 0.002 ± 5.77e-4) networks, t(60) ≥ 3.124, p ≤ 0.042, but not in the limbic or visual networks, p ≥ 0.712 (Figure 4D and Table S4).

Additional comparisons between the high-resolution data and the standard data limited to the b = 1500 s/mm2 shell are provided in the Supplementary Material. As expected, there were some noticeable differences (e.g., slightly larger effect size of sequence for FA, smaller effect for MD), but the overall higher-order pattern of results remained the same as those reported above.

Correlations Between DWI Sequences

Next, we used separate Pearson correlations to examine associations between the high-resolution and standard DWI measures (FDR-corrected for nine comparisons). For GM microstructure, the global measures were moderately correlated for FA, r = 0.511, and strongly correlated for MD, r = 0.956 (Table 2). At the network level, the correlations between sequences ranged from r = 0.205 (limbic network) to r = 0.802 (ventral attention network) for FA, and from r = 0.550 (limbic network) to r = 0.980 (dorsal attention network) for MD (Table 2 and Figure 5).

Table 2.

Age correlations with gray matter microstructure

| R HCP- Age |

(pFDR) | R MUSE- Age |

(pFDR) | R MUSE- HCP |

(pFDR) | Steiger’s z |

(pFDR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fractional Anisotropy (FA) | ||||||||

| Global | −0.244 | (0.095) | −0.270 | (0.063) | 0.511 | (<0.001) | 0.209 | (0.880) |

| DAN | −0.411 | (0.003) | −0.367 | (0.018) | 0.638 | (<0.001) | 0.435 | (0.880) |

| DMN | −0.133 | (0.308) | −0.178 | (0.192) | 0.508 | (<0.001) | 0.351 | (0.880) |

| FPN | −0.240 | (0.095) | −0.338 | (0.024) | 0.458 | (<0.001) | 0.758 | (0.806) |

| LMB | −0.149 | (0.300) | −0.370 | (0.018) | 0.205 | (0.113) | 1.405 | (0.466) |

| SMN | −0.480 | (<0.001) | −0.294 | (0.047) | 0.603 | (<0.001) | 1.758 | (0.356) |

| SUB | −0.144 | (0.300) | −0.161 | (0.216) | 0.623 | (<0.001) | 0.151 | (0.880) |

| VAN | 0.291 | (0.052) | 0.190 | (0.183) | 0.802 | (<0.001) | 1.263 | (0.466) |

| VIS | −0.411 | (0.003) | −0.222 | (0.128) | 0.631 | (<0.001) | 1.786 | (0.356) |

| Mean Diffusivity (MD) | ||||||||

| Global | 0.741 | (<0.001) | 0.805 | (<0.001) | 0.959 | (<0.001) | 2.738 | (0.014) |

| DAN | 0.725 | (<0.001) | 0.730 | (<0.001) | 0.980 | (<0.001) | 0.279 | (0.869) |

| DMN | 0.640 | (<0.001) | 0.773 | (<0.001) | 0.899 | (<0.001) | 3.304 | (0.003) |

| FPN | 0.576 | (<0.001) | 0.741 | (<0.001) | 0.855 | (<0.001) | 3.227 | (0.003) |

| LMB | 0.371 | (0.003) | 0.628 | (<0.001) | 0.550 | (<0.001) | 2.501 | (0.022) |

| SMN | 0.779 | (<0.001) | 0.782 | (<0.001) | 0.975 | (<0.001) | 0.165 | (0.869) |

| SUB | 0.681 | (<0.001) | 0.710 | (<0.001) | 0.959 | (<0.001) | 1.084 | (0.417) |

| VAN | 0.658 | (<0.001) | 0.737 | (<0.001) | 0.968 | (<0.001) | 3.356 | (0.003) |

| VIS | 0.657 | (<0.001) | 0.676 | (<0.001) | 0.967 | (<0.001) | 0.761 | (0.575) |

Note. Networks are abbreviated as dorsal attention (DAN), default mode (DMN), frontoparietal (FPN), limbic (LMB), sensorimotor (SMN), subcortical (SUB), ventral attention (VAN), and visual (VIS). MUSE = high-resolution multiplexed sensitivity encoding, HCP = human connectome project, FDR = false discovery rate corrected p-values for the correlations presented in the preceding column. Significant effects are presented in bold.

Figure 5.

Correlations between sequences. For each pair of networks, heatmaps display correlation coefficients between the gray matter (A) fractional anisotropy and (B) mean diffusivity estimates from the standard resolution (x-axis) or high-resolution (y-axis) data. Cooler colors indicate stronger or more positive correlations; warmer colors indicate weaker or negative correlations. Black squares along the diagonal highlight the correlations between measures from the same network. Networks are abbreviated as dorsal attention (DAN), default mode (DMN), frontoparietal (FPN), limbic (LMB), sensorimotor (SMN), subcortical (SUB), ventral attention (VAN), and visual (VIS).

Additional correlations between the high-resolution data and the standard data limited to the b = 1500 s/mm2 shell are provided in the Supplementary Material. The global measures remained moderately correlated for FA, r = 0.604, and strongly correlated for MD, r = 0.972, with comparable patterns also observed at the network level.

For WM structural connectivity, the global measures were strongly correlated for within-network, r = 0.788, and between-network, r = 0.860, connectivity (Table 3). At the network level, the correlations between sequences ranged from r = 0.290 (limbic network) to r = 0.599 (sensorimotor network) for within-network connectivity, and from r = 0.480 (limbic network) to r = 0.840 (default mode network) for between-network connectivity (Table 3 and Figure 6).

Table 3.

Age correlations with white matter structural connectivity

| R HCP- Age |

(pFDR) | R MUSE- Age |

(pFDR) | R MUSE- HCP |

(pFDR) | Steiger’s z |

(pFDR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within-Network Connectivity | ||||||||

| Global | −0.716 | (<0.001) | −0.653 | (<0.001) | 0.788 | (<0.001) | 1.064 | (0.155) |

| DAN | −0.659 | (<0.001) | −0.527 | (<0.001) | 0.581 | (<0.001) | 1.456 | (0.218) |

| DMN | −0.687 | (<0.001) | −0.412 | (0.004) | 0.410 | (0.001) | 2.518 | (0.036) |

| FPN | −0.549 | (<0.001) | −0.107 | (0.409) | 0.403 | (0.001) | 3.356 | (0.009) |

| LMB | −0.369 | (0.003) | −0.165 | (0.233) | 0.290 | (0.023) | 1.374 | (0.219) |

| SMN | −0.590 | (<0.001) | −0.331 | (0.014) | 0.599 | (<0.001) | 2.570 | (0.036) |

| SUB | −0.222 | (0.086) | −0.268 | (0.049) | 0.544 | (<0.001) | 0.38 | (0.791) |

| VAN | −0.395 | (0.002) | −0.372 | (0.008) | 0.518 | (<0.001) | 0.197 | (0.844) |

| VIS | −0.567 | (<0.001) | −0.349 | (0.012) | 0.452 | (<0.001) | 1.863 | (0.140) |

| Between-Network Connectivity | ||||||||

| Global | −0.779 | (<0.001) | −0.630 | (<0.001) | 0.860 | (<0.001) | 3.176 | (0.003) |

| DAN | −0.782 | (<0.001) | −0.648 | (<0.001) | 0.754 | (<0.001) | 2.259 | (0.036) |

| DMN | −0.762 | (<0.001) | −0.591 | (<0.001) | 0.840 | (<0.001) | 3.285 | (0.003) |

| FPN | −0.799 | (<0.001) | −0.643 | (<0.001) | 0.821 | (<0.001) | 3.071 | (0.004) |

| LMB | −0.625 | (0.003) | −0.281 | (0.028) | 0.480 | (<0.001) | 3.026 | (0.004) |

| SMN | −0.753 | (<0.001) | −0.639 | (<0.001) | 0.764 | (<0.001) | 1.881 | (0.060) |

| SUB | −0.723 | (<0.001) | −0.504 | (<0.001) | 0.808 | (<0.001) | 3.563 | (0.003) |

| VAN | −0.707 | (<0.001) | −0.586 | (<0.001) | 0.834 | (<0.001) | 2.174 | (0.039) |

| VIS | −0.690 | (<0.001) | −0.537 | (<0.001) | 0.715 | (<0.001) | 2.059 | (0.044) |

Note. Networks are abbreviated as dorsal attention (DAN), default mode (DMN), frontoparietal (FPN), limbic (LMB), sensorimotor (SMN), subcortical (SUB), ventral attention (VAN), and visual (VIS). MUSE = high-resolution multiplexed sensitivity encoding, HCP = human connectome project, FDR = false discovery rate corrected p-values for the correlations presented in the preceding column. Significant effects are presented in bold.

Figure 6.

Correlations between sequences. For each pair of networks, heatmaps display correlation coefficients between the white matter (A) within-network and (B) between-network connectivity estimates from the standard resolution (x-axis) or high-resolution (y-axis) data. Cooler colors indicate stronger or more positive correlations; warmer colors indicate weaker or negative correlations. Black squares along the diagonal highlight the correlations between measures from the same network. Networks are abbreviated as dorsal attention (DAN), default mode (DMN), frontoparietal (FPN), limbic (LMB), sensorimotor (SMN), subcortical (SUB), ventral attention (VAN), and visual (VIS).

Correlations with Age

We conducted Pearson correlations between age and each global or network level metric for each sequence (FDR-corrected for nine comparisons) and tested for significant differences in the age correlations between sequences (Steiger, 1980; Weiss, 2011).

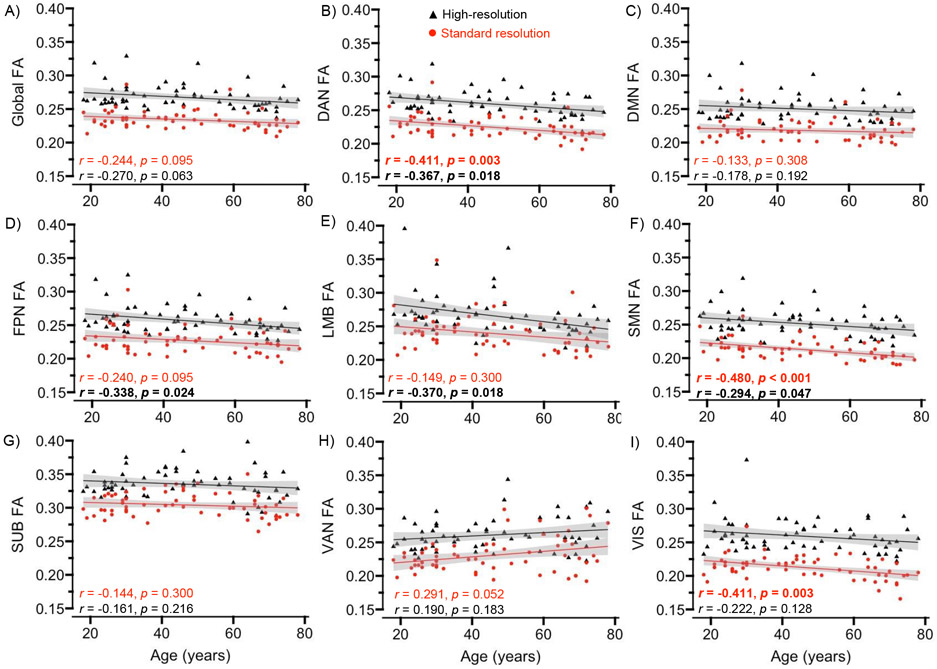

For GM FA, the high-resolution data yielded significant age-related decreases in the dorsal attention, sensorimotor, frontoparietal, and limbic networks, and the standard data yielded significant age-related decreases in the dorsal attention, sensorimotor, and visual networks (Table 2 and Figure 7). For GM MD, both sequences yielded significant age-related increases in the global measure and each network (Table 2 and Figure 8). The Steiger’s z tests indicated that the age correlations for global, default mode, frontoparietal, limbic, and ventral attention MD were significantly larger for the high-resolution relative to standard data, with no significant differences in correlations for FA (Table 2).

Figure 7.

Age correlations with gray matter (GM) fractional anisotropy (FA). Scatterplots display associations between age and GM FA at the global (A) and network (B-I) levels, separately for the high-resolution (black triangles) and standard (red circles) data. Networks are abbreviated as dorsal attention (DAN), default mode (DMN), frontoparietal (FPN), limbic (LMB), sensorimotor (SMN), subcortical (SUB), ventral attention (VAN), and visual (VIS). The shaded gray area around the regression line represents 95% confidence intervals. Significant effects are presented in bold.

Figure 8.

Age correlations with gray matter (GM) mean diffusivity (MD). Scatterplots display associations between age and GM MD at the global (A) and network (B-I) levels, separately for the high-resolution (black triangles) and standard (green circles) data. Networks are abbreviated as dorsal attention (DAN), default mode (DMN), frontoparietal (FPN), limbic (LMB), sensorimotor (SMN), subcortical (SUB), ventral attention (VAN), and visual (VIS). The shaded gray area around the regression line represents 95% confidence intervals. Significant effects are presented in bold.

For within-network connectivity, the high-resolution data yielded significant age-related decreases in the global measure and all networks except the frontoparietal and limbic networks, and the standard data yielded significant age-related decreases in the global measure and all networks except the subcortical network (Table 3 and Figure 9). For between-network connectivity, both sequences yielded significant age-related decreases in the global measure and all networks (Table 3 and Figure 10). The Steiger’s z tests indicated that the age correlations were significantly larger for the standard relative to high-resolution data for within-network connectivity in the default mode, frontoparietal, and sensorimotor networks, and between-network connectivity in the global measure and all networks except the sensorimotor network (Table 3).

Figure 9.

Age correlations with within-network connectivity. Scatterplots display associations between age and within-network connectivity at the global (A) and network (B-I) levels, separately for the high-resolution (black triangles) and standard (blue circles) data. Networks are abbreviated as dorsal attention (DAN), default mode (DMN), frontoparietal (FPN), limbic (LMB), sensorimotor (SMN), subcortical (SUB), ventral attention (VAN), and visual (VIS). The shaded gray area around the regression line represents 95% confidence intervals. Significant effects are presented in bold.

Figure 10.

Age correlations with between-network connectivity. Scatterplots display associations between age and between-network connectivity at the global (A) and network (B-I) levels, separately for the high-resolution (black triangles) and standard (purple circles) data. Networks are abbreviated as dorsal attention (DAN), default mode (DMN), frontoparietal (FPN), limbic (LMB), sensorimotor (SMN), subcortical (SUB), ventral attention (VAN), and visual (VIS). The shaded gray area around the regression line represents 95% confidence intervals. Significant effects are presented in bold.

Explaining Age-Related Variance in Fluid Cognition

To test whether the high-resolution data better explained age-related variance in fluid cognition than the standard data, we conducted hierarchical linear regressions with age and the standard measure as predictors in the first block, and age and both the standard and high-resolution measures as predictors in the second block, with fluid cognition as the outcome variable. Each model was conducted separately at the global and network level and for each structural measure of interest. We specifically tested whether there was a significant change (Δ) in R2 when adding the high-resolution variable to the model.

For GM MD, the high-resolution data explained additional variance in fluid cognition beyond age and the standard data in the ventral attention network, Δ R2 = 0.020, p = 0.034. For within-network WM connectivity, the high-resolution data explained additional variance in fluid cognition beyond age and the standard data in the dorsal attention network, Δ R2 = 0.038, p = 0.003. For between-network WM connectivity, the high-resolution data explained additional variance in fluid cognition beyond age and the standard data in the subcortical network, Δ R2 = 0.027, p = 0.012. The change in R2 was not significant at the global or network level for GM FA, p ≥ 0.224, or for any other measure of MD or connectivity, p ≥ 0.069.

Mediation of Fluid Cognition

Finally, for the three high-resolution measures that explained additional age-related variance in cognition beyond the standard measures, we conducted mediation analyses to determine whether they also mediated age-related decline in fluid cognition. We created three mediation models, each of which included age as the predictor variable, general fluid cognition performance as the outcome variable, and a high-resolution measure and the corresponding standard version of it as parallel mediators. Because parallel mediators are covaried for each other, this approach provides a direct comparison of the mediation effects for the two measures. These analyses were conducted using the PROCESS macro (Hayes & Rockwood, 2017), with significant indirect effects (i.e., an interaction between model paths) determined by 95% confidence intervals (CIs) that did not contain zero after 10,000 bootstrap replacements.

Results indicated that the high-resolution, but not the standard, measures of ventral attention network MD (Table 4, Model 1), dorsal attention within-network connectivity (Table 4, Model 2), and subcortical between-network connectivity (Table 4, Model 3) each significantly mediated the relation between age and fluid cognition.

Table 4.

Mediation of Fluid Cognition

| Effect | SE | t | p | Lower CI | Upper CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Ventral Attention Network (VAN) Mean Diffusivity (MD) | ||||||

| Age effect (a path) | ||||||

| MUSE VAN MD | 3.50e-6 | 4.00e-6 | 8.372 | < 0.001 | 2.70e-6 | 4.30e-6 |

| HCP VAN MD | 2.40e-6 | 4.00e-6 | 6.704 | < 0.001 | 1.70e-6 | 3.10e-6 |

| Mediator to outcome (b path) | ||||||

| MUSE VAN MD | −7341.498 | 3384.223 | −2.169 | 0.034 | −14118.330 | −564.665 |

| HCP VAN MD | 7196.650 | 3905.903 | 1.842 | 0.071 | −624.835 | 15018.135 |

| Total effect for age (c path) | ||||||

| −0.045 | 0.004 | −12.965 | < 0.001 | −0.052 | −0.038 | |

| Direct effect for age (c’ path) | ||||||

| −0.037 | 0.005 | −6.972 | < 0.001 | −0.048 | −0.027 | |

| Mediation effect (a x b path interaction) | ||||||

| MUSE VAN MD | −0.026 | 0.012 | – | – | −0.050 | −0.002 |

| HCP VAN MD | 0.017 | 0.010 | – | – | −0.002 | 0.036 |

| Model 2: Dorsal Attention (DAN) Within-Network Connectivity | ||||||

| Age effect (a path) | ||||||

| MUSE DAN Within | −0.0004 | 7.72e-5 | −4.767 | < 0.001 | −0.0005 | −0.0002 |

| HCP DAN Within | −0.0005 | 8.10e-5 | −6.737 | < 0.001 | −0.0007 | −0.0004 |

| Mediator to outcome (b path) | ||||||

| MUSE DAN Within | 18.661 | 5.931 | 3.146 | 0.003 | 6.784 | 30.538 |

| HCP DAN Within | −1.773 | 5.646 | −0.314 | 0.755 | −13.079 | 9.533 |

| Total effect for age (c path) | ||||||

| −0.045 | 0.004 | −12.965 | < 0.001 | −0.052 | −0.038 | |

| Direct effect for age (c’ path) | ||||||

| −0.040 | 0.004 | −8.831 | < 0.001 | −0.049 | −0.031 | |

| Mediation effect (a x b path interaction) | ||||||

| MUSE DAN Within | −0.007 | 0.002 | – | – | −0.011 | −0.003 |

| HCP DAN Within | 0.001 | 0.003 | – | – | −0.004 | 0.006 |

| Model 3: Subcortical (SUB) Between-Network Connectivity | ||||||

| Age effect (a path) | ||||||

| MUSE SUB Between | −9.07e-5 | 2.02e-5 | −4.484 | < 0.001 | −0.0001 | 5.02e-5 |

| HCP SUB Between | −1.00e-4 | 1.25e-5 | −8.042 | < 0.001 | −0.0001 | 7.53e-5 |

| Mediator to outcome (b path) | ||||||

| MUSE SUB Between | −83.407 | 32.280 | −2.583 | 0.012 | −148.048 | −18.767 |

| HCP SUB Between | 72.604 | 52.413 | 1.385 | 0.171 | −32.351 | 177.560 |

| Total effect for age (c path) | ||||||

| −0.045 | 0.004 | −12.965 | < 0.001 | −0.052 | −0.038 | |

| Direct effect for age (c’ path) | ||||||

| −0.046 | 0.005 | −9.225 | < 0.001 | −0.056 | −0.036 | |

| Mediation effect (a x b path interaction) | ||||||

| MUSE DAN Between | 0.008 | 0.003 | – | – | 0.002 | 0.013 |

| HCP DAN Between | −0.007 | 0.005 | – | – | −0.017 | 0.002 |

Note. Mediation models with age as the predictor variable (x), fluid cognition as the outcome variable (y), and high-resolution and standard DWI measures as parallel mediators (m); a = path from predictor to mediator; b = path from mediator to outcome, controlling for a path; c = total effect of predictor; c’ = direct effect of predictor, controlling for mediators; a x b = interaction of a and b paths representing indirect influence of x on y as mediated by m; effect = unstandardized regression coefficient; SE = standard error; Lower/Upper CI = lower/upper bounds of bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals, estimated using 10,000 bootstrap samples. Significant effects are presented in bold.

Discussion

Previous work has associated age-related differences in fluid cognition with the microstructural degradation of neural tissue and disconnection of WM pathways between distributed GM regions. But these prior investigations have primarily used standard DWI acquisitions, which are limited in their spatial resolution and ability to resolve more complex anatomical properties. Here, we compared structural measures of GM microstructure and WM connectivity derived from a high-resolution MUSE DWI sequence to those derived from a standard HCP-style DWI sequence and examined whether these measures were differentially related to age and age-related cognitive decline. Extending earlier animal and postmortem high-resolution DWI studies, our findings suggest that high-resolution and standard DWI sequences differentially estimate GM microstructure and WM connectivity, and that these measures are, in turn, differentially related to chronological age. Moreover, only the structural measures derived from the high-resolution DWI data significantly mediated age-related decline in fluid cognition. Together, this study takes an important first step toward understanding the utility of high-resolution DWI methodology in future investigations of healthy aging or cognitive impairment.

Comparison of Sequences

Although the global structural measures were at least moderately correlated between sequences, we found that estimates of both GM microstructure and WM structural connectivity were higher in the high-resolution MUSE data than the standard HCP-style data (Figure 4). Prior studies report that there are more accurate and coherent patterns of tensor fitting in GM tissue for high-resolution than standard data (Chen et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2011), with one explanation being fewer partial volume effects (Vu et al., 2015). Fewer partial volume effects, especially from less CSF contamination, could explain the higher FA values observed for the high-resolution relative to standard data, as well as the moderate correlation between their global estimates of FA (r = 0.511). But this same explanation cannot also account for the higher estimate of MD that was observed for the high-resolution data because MD should be lower in voxels with less CSF. Instead, the pattern of higher FA/higher MD in the high-resolution data may reflect its ability to better resolve the GM/WM boundary (Vu et al., 2015) and individual subsets of cortex, which has an average thickness of 2.5 mm (Fischl & Dale, 2000). Each 1 mm3 voxel in the high-resolution data has a volume of 1 μl, which is the same size as the thinnest areas of cortex (Fischl & Dale, 2000). In contrast, each 1.5 mm3 voxel in the standard data has a volume of 3.375 μl, which is larger than most areas of cortex. The smaller voxel size also helps prevent premature streamline terminations into gyri with small, tightly curved u-fibers (Guevara et al., 2020; Schilling et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2022), which could explain the pattern of higher WM connectivity observed in the high-resolution data here and in prior studies (Anderson et al., 2020; Caiazzo et al., 2018; Chang et al., 2015; Crater et al., 2022).

We further observed that the strength of correlations, and mean differences, between the structural measures varied at the network level. Relative to the standard data, the high-resolution data estimated higher FA/MD for all eight networks, but there was a large range in the correlations between sequences at the network level for both FA and MD (Figure 5; r range ≥ 0.430). Relative to the standard data, the high-resolution data also estimated higher between-network connectivity for most networks (c.f., limbic and visual networks), higher within-network connectivity for the sensorimotor, subcortical, and ventral attention networks, and lower within-network connectivity for the limbic network (Figure 6). Across all four structural measures assessed here, the correlation between sequences was weakest for the limbic network, which could reflect measurement instability from excluding 11 inferior temporal nodes from this network due to poor spatial coverage in the high-resolution data. Regions belonging to the limbic network are also among the most affected by signal dropout in EPI sequences, which is more prevalent in single-shot than multi-shot EPI data (Papanikolaou et al., 2006). While several other anatomical (e.g., degree of cortical curvature or thickness, number of crossing fibers) and methodological (e.g., SNR, quality of mask alignment) factors could explain the range in correlations across networks, researchers should nonetheless consider how these structural measures vary at the network level when comparing findings between standard and high-resolution DWI studies.

Aging and Gray Matter Microstructure

To our knowledge, this study is the first to assess age-related differences in the microstructure of functionally defined GM networks. We found that both DWI sequences yielded significant age-related decreases in FA for the dorsal attention and sensorimotor networks (Figure 7), coupled with increases in MD for all eight networks and the global measure (Figure 8). Age-related decreases in FA were seen also for the limbic and frontoparietal networks in the high-resolution data, and for the visual network in the standard data. This pattern of lower FA/higher MD in aging replicates prior standard resolution studies that have used DTI to assess both WM (for reviews, see Bennett & Madden, 2014; Madden et al., 2012) and GM (Abe et al., 2008; Benedetti et al., 2006; Bhagat & Beaulieu, 2004; Radhakrishnan et al., 2022; Reas et al., 2020) microstructure. Normal age-related differences in GM microstructure likely reflect a combination of neuroinflammation, synaptic loss, and differences in dendritic density (Grussu et al., 2017; Pannese, 2011). However, the current study, based on the diffusion tensor model, is limited in its ability to draw inferences about specific microstructural contributions to the observed age-related differences in GM microstructure and to the differences in FA/MD between the standard and high-resolution data. Disentangling the contributions of these distinct microstructural properties will benefit from future work using multicompartment, biophysical models (e.g., Zhang et al., 2012).

An additional finding from this study is that high-resolution DWI, relative to standard DWI, yielded significantly larger correlations between age and MD for the global measure and the default mode, frontoparietal, limbic, and ventral attention networks (Table 3). Without histological validation of how the DTI metrics from each sequence map onto the underlying anatomy, it is difficult to definitively conclude whether one sequence provides a “better” or more accurate estimate of age-related differences in the complex cytoarchitecture of GM. However, we do know that the 1 mm3 voxel size of the high-resolution data is more similar to the thickness of the cerebral cortex than the 1.5 mm3 standard voxel size (Fischl & Dale, 2000). Thus, the larger age-related differences in MD, as assessed by the high-resolution data, may suggest that healthy brain aging is associated with a greater decline in GM microstructural properties than one would conclude based on standard DWI data. As expected, relative to MD, we observed fewer significant correlations between age and FA for both sequences, which supports the notion that this measure is not as well-suited for the more isotropic nature of GM than WM tissue (Benedetti et al., 2006; Helenius et al., 2002) and raises the possibility that spatial resolutions < 1 mm3 may be needed to accurately assess GM FA in vivo.

Aging and Structural Connectivity

We observed age-related decreases in both within- and between-network WM structural connectivity, at the global and network level, for both the high-resolution and standard data (Figures 9 and 10), consistent with previous graph theory studies (Betzel et al., 2014; Madden et al., 2020). In contrast to the findings for GM microstructure, we found that the standard data, relative to the high-resolution data, yielded significantly larger correlations between age and within-network connectivity in the default mode, frontoparietal, and sensorimotor networks, and between-network connectivity in all networks except the sensorimotor network. Because global connectivity was significantly lower in the standard relative to high-resolution data, the larger correlations with age for the standard data may be driven by an underestimation of streamlines, possibly due to artifacts (e.g., CSF contamination) or measurement inaccuracies (e.g., premature termination of fiber connections) in small, tightly curved u-fibers (Guevara et al., 2020; Schilling et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2022). The lower connectivity estimated by the standard data may therefore contribute to an inflated estimate of age-related differences in connectivity, especially when taken together with evidence that the structural properties of these fine-grained superficial WM regions may be somewhat less affected by healthy aging than larger, long-range tracts (Schilling et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2016). As with the GM microstructure findings, we cannot say whether the larger correlations in the standard data reflect a “better” or more accurate assessment of the underlying anatomical connections using only in vivo data. However, prior work has also demonstrated that lower spatial resolution DWI estimates lower connectivity, especially for smaller WM regions connecting cortical regions (Anderson et al., 2020; Caiazzo et al., 2018). Although speculative, one implication from these findings is that the magnitude of age-related decreases in structural connectivity may be at least some degree smaller than one would conclude from prior standard resolution DWI analyses.

Mediation of Fluid Cognition

Increased adult age was associated with lower general fluid cognition performance, although the age-related effects were not associated specifically with the individual domains of memory, executive function, or perceptual-motor speed (Figure 3). These findings are consistent with previous evidence indicating that measures of fluid cognition share substantial age-related variance (Salthouse, 1996, 2005; Salthouse & Madden, 2007). Here, we assessed whether variability in fluid cognition performance was related to the structural measures derived from the high-resolution data, beyond the effect of chronological age and the structural measures derived from the standard data (i.e., Δ R2). We assumed that if the structural measures are more accurate when derived from one sequence versus the other, then the measures from that sequence should also have greater functional relevance, such as their ability to explain age-related cognitive decline. In support of this notion, we found that the high-resolution data accounted for a unique portion of the variance in cognition for the measures of ventral attention network microstructure (MD), dorsal attention within-network connectivity, and subcortical between-network connectivity. In addition, each of these measures mediated age-related decline in fluid cognition (Table 4). The specificity of the current mediation effects to the dorsal and ventral attention networks could reflect their domain-general role in top-down and bottom-up processing (Kim, 2014; Vossel et al., 2014), and the subcortical network in general alerting and motor response preparation and execution (Kim, 2014; Langner & Eickhoff, 2013; Madden et al., 2004), all of which are components that should be common to each cognitive task used here. Despite the relatively strong correlations between sequences for these measures (r ≥ 0.580), these findings suggest that the high-resolution data captures unique aspects of GM microstructure and WM connectivity that are also helpful for explaining age-related differences in cognition.

To our knowledge, the current study is the first to assess the relevance of high-resolution versus standard DWI measures to age-related differences in general fluid cognition, extending prior high-resolution DWI work limited to the memory domain (Granger et al., 2023; Granger et al., 2022; Solar et al., 2021). At least one earlier study similarly found that high-resolution DWI measures of WM structural connectivity were more closely tied to cognition in healthy younger adults, relative to standard DWI measures (Mansour et al., 2021). Previous work has also demonstrated that, despite having lower SNR, high-resolution DTI measures of WM microstructure exhibited a higher correlation with disease progression in patients with multiple sclerosis, when compared to the lower spatial resolution measures (Laganà et al., 2010). Taken together, these findings suggest that GM microstructural degradation and WM structural disconnection, as assessed by high-resolution DWI, may be sensitive to age-related neurodegenerative disease.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study is strengthened by the recruitment of participants across the adult lifespan, extensively characterized measure of cognition, and collection of both high-resolution and standard DWI sequences from the same individuals. However, the high-resolution MUSE sequence acquired here employed only a single diffusion-weighted shell using a relatively lower b-value of 1000 s/mm2. Single-shell DWI acquisitions are limited in their ability to resolve hindered from restricted components of diffusion (Assaf & Basser, 2005; Assaf et al., 2004), but we decided to use a single, lower b-value to help offset the reductions in SNR that are observed with smaller voxels. Nonetheless, when repeating our primary analyses of FA/MD using only data from the lower, b = 1500 s/mm2 shell in the standard data, the overall higher-order pattern of results did not change, suggesting that differences between DTI metrics primarily reflect differences in spatial resolution. Importantly, while the high-resolution MUSE sequence did exhibit lower SNR than the standard data, the average SNR of this sequence was still well into the acceptable range for DWI data. Nonetheless, differences in SNR should be considered when interpreting differences in tensor-based measures, like FA, which tend to be biased upward as SNR decreases (Farrell et al., 2007; Papanikolaou et al., 2006). Beyond the different b-values and spatial resolutions, differences in angular resolution (i.e., the number of diffusion-weighted directions) may also contribute to differences between sequences (Anderson et al., 2020). Future analyses are needed to address the contributions of high spatial versus high angular resolution to age-related differences in microstructure and connectivity, and their relations to cognition. Doing so is an ongoing line of work in our neuroimaging facility, which is actively developing a multiband MUSE acquisition with at least 28 diffusion-weighted directions (Bruce et al., 2017).

Conclusions

The Human Connectome Project greatly improved the standards of DWI data acquisition for the field (Glasser et al., 2016; Harms et al., 2018), but high-resolution MUSE acquisitions may help the field move forward even further, especially for examining the multifaceted effects of brain aging on DWI parameters and the relation of these parameters to cognitive performance. We observed that the high-resolution and standard data exhibited correlated, but different, estimates of GM microstructure and WM structural connectivity, and only the high-resolution structural measures mediated age-related decline in fluid cognition. These results lay the groundwork for future studies that may wish to use high-resolution DWI methodology for examining healthy and pathological neurocognitive aging and suggest that high-resolution DWI may serve as an early indicator of atypical age-related cognitive decline.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by R01 AG039684 (D.J.M). We thank Cortney Howard, Shivangi Jain, Alexa Putka, Angela Cook, Matthew Wang, and Nicole Stepovich for their assistance.

References

- Abe O, Yamasue H, Aoki S, Suga M, Yamada H, Kasai K, Masutani Y, Kato N, Kato N, & Ohtomo K (2008). Aging in the CNS: Comparison of gray/white matter volume and diffusion tensor data. Neurobiology of Aging, 29(1), 102–116. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RJ, Long CM, Calabrese ED, Robertson SH, Johnson GA, Cofer GP, O'Brien RJ, & Badea A (2020). Optimizing diffusion imaging protocols for structural connectomics in mouse models of neurological conditions. Frontiers in Physics, 8(1). 10.3389/fphy.2020.00088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assaf Y (2019). Imaging laminar structures in the gray matter with diffusion MRI. Neuroimage, 197(1), 677–688. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.12.096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assaf Y, & Basser PJ (2005). Composite hindered and restricted model of diffusion (CHARMED) MR imaging of the human brain. Neuroimage, 27(1), 48–58. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assaf Y, Freidlin RZ, Rohde GK, & Basser PJ (2004). New modeling and experimental framework to characterize hindered and restricted water diffusion in brain white matter. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 52(5), 965–978. 10.1002/mrm.20274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach M (1996). The Freiburg Visual Acuity Test - Automatic measurement of visual acuity. Optometry and Vision Science, 73(1), 49–53. 10.1097/00006324-199601000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastiani M, Cottaar M, Fitzgibbon SP, Suri S, Alfaro-Almagro F, Sotiropoulos SN, Jbabdi S, & Andersson JLR (2019). Automated quality control for within and between studies diffusion MRI data using a non-parametric framework for movement and distortion correction. Neuroimage, 184(1), 801–812. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.09.073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu C (2002). The basis of anisotropic water diffusion in the nervous system - A technical review. NMR in Biomedicine, 15(7–8), 435–455. 10.1002/nbm.782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT (1978). The Beck Depression Inventory. Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti B, Charil A, Rovaris M, Judica E, Valsasina P, Sormani MP, & Filippi M (2006). Influence of aging on brain gray and white matter changes assessed by conventional, MT, and DT MRI. Neurology, 66(4), 535–539. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000198510.73363.c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, & Hochberg Y (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett IJ, & Madden DJ (2014). Disconnected aging: cerebral white matter integrity and age-related differences in cognition. Neuroscience, 276(1), 187–205. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.11.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betzel RF, Byrge L, He Y, Goñi J, Zuo X-N, & Sporns O (2014). Changes in structural and functional connectivity among resting-state networks across the human lifespan. Neuroimage, 102(1), 345–357. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2014.07.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat YA, & Beaulieu C (2004). Diffusion anisotropy in subcortical white matter and cortical gray matter: Changes with aging and the role of CSF-suppression. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 20(2), 216–227. 10.1002/jmri.20102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce IP, Chang H-C, Petty C, Chen N-K, & Song AW (2017). 3D-MB-MUSE: A robust 3D multi-slab, multi-band and multi-shot reconstruction approach for ultrahigh resolution diffusion MRI. Neuroimage, 159(1), 46–56. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.07.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caiazzo G, Fratello M, Di Nardo F, Trojsi F, Tedeschi G, & Esposito F (2018). Structural connectome with high angular resolution diffusion imaging MRI: assessing the impact of diffusion weighting and sampling on graph-theoretic measures. Neuroradiology, 60(5), 497–504. 10.1007/s00234-018-2003-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capogna E, Sneve MH, Raud L, Folvik L, Ness HT, Walhovd KB, Fjell AM, & Vidal-Piñeiro D (2022). Whole-brain connectivity during encoding: age-related differences and associations with cognitive and brain structural decline. Cerebral Cortex, 33(1), 68–82. 10.1093/cercor/bhac053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H-C, Sundman M, Petit L, Guhaniyogi S, Chu M-L, Petty C, Song AW, & Chen N-K (2015). Human brain diffusion tensor imaging at submillimeter isotropic resolution on a 3 Tesla clinical MRI scanner. Neuroimage, 118(1), 667–675. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen NK, Guidon A, Chang HC, & Song AW (2013). A robust multi-shot scan strategy for high-resolution diffusion weighted MRI enabled by multiplexed sensitivity-encoding (MUSE). Neuroimage, 72(1), 41–47. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civier O, Smith RE, Yeh C-H, Connelly A, & Calamante F (2019). Is removal of weak connections necessary for graph-theoretical analysis of dense weighted structural connectomes from diffusion MRI? Neuroimage, 194(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.02.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crater S, Maharjan S, Qi Y, Zhao Q, Cofer G, Cook JC, Johnson GA, & Wang N (2022). Resolution and b value dependent structural connectome in ex vivo mouse brain. Neuroimage, 255, 119199. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2022.119199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhollander T, Mito R, Raffelt D, & Connelly A (2019). Improved white matter response function estimation for 3-tissue constrained spherical deconvolution. 27th International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Montréal, Québec, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorine I (1963). Quantiative assessment of the color-blind. Journal of General Psychology, 68(2), 255–265. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/00221309.1963.9920533 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein WA, Glover GH, Hardy CJ, & Redington RW (1986). The intrinsic signal-to-noise ratio in NMR imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 3(4), 604–618. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/mrm.1910030413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L, Li H, Zhuo J, Zhang Y, Wang J, Chen L, Yang Z, Chu C, Xie S, Laird AR, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB, Yu C, & Jiang T (2016). The human brainnetome atlas: A new brain atlas based on connectional architecture. Cerebral Cortex, 26(8), 3508–3526. 10.1093/cercor/bhw157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell JAD, Landman BA, Jones CK, Smith SA, Prince JL, Van Zijl PCM, & Mori S (2007). Effects of signal-to-noise ratio on the accuracy and reproducibility of diffusion tensor imaging–derived fractional anisotropy, mean diffusivity, and principal eigenvector measurements at 1.5T. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 26(3), 756–767. 10.1002/jmri.21053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, & Dale AM (2000). Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97(20), 11050–11055. 10.1073/pnas.200033797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjell AM, Sneve MH, Grydeland H, Storsve AB, Amlien IK, Yendiki A, & Walhovd KB (2017). Relationship between structural and functional connectivity change across the adult lifespan: A longitudinal investigation. Human Brain Mapping, 38(1), 561–573. 10.1002/hbm.23403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, & McHugh PR (1975). “Mini-mental state”. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon RC, Wagster MV, Hendrie HC, Fox NA, Cook KF, & Nowinski CJ (2013). NIH toolbox for assessment of neurological and behavioral function. Neurology, 80(11 Suppl 3), S2–S6. 10.1212/wnl.0b013e3182872e5f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser MF, Smith SM, Marcus DS, Andersson JLR, Auerbach EJ, Behrens TEJ, Coalson TS, Harms MP, Jenkinson M, Moeller S, Robinson EC, Sotiropoulos SN, Xu J, Yacoub E, Ugurbil K, & Van Essen DC (2016). The Human Connectome Project's neuroimaging approach. Nature Neuroscience, 19(1), 1175–1187. 10.1038/nn.4361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn DE, Merenstein JL, Bennett IJ, & Michalska KJ (2022). Anxiety symptoms and puberty interactively predict lower cingulum microstructure in preadolescent Latina girls. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 20755. 10.1038/s41598-022-24803-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger SJ, Colon-Perez L, Larson MS, Bennett IJ, Phelan M, Keator DB, Janecek JT, Sathishkumar MT, Smith AP, McMillan L, Greenia D, Corrada MM, Kawas CH, & Yassa MA (2023). Reduced structural connectivity of the medial temporal lobe including the perforant path is associated with aging and verbal memory impairment. Neurobiology of Aging, 121(1), 119–128. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2022.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger SJ, Colon-Perez L, Larson MS, Phelan M, Keator DB, Janecek JT, Sathishkumar MT, Smith AP, McMillan L, Greenia D, Corrada MM, Kawas CH, & Yassa MA (2022). Hippocampal dentate gyrus integrity revealed with ultrahigh resolution diffusion imaging predicts memory performance in older adults. Hippocampus, 32(9), 627–638. 10.1002/HIPO.23456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]