Abstract

Nucleic acid nanotechnology utilizes natural and synthetic structural motifs to build versatile nucleic acid nanoparticles (NANPs). These rationally designed assemblies can be further equipped with functional nucleic acids and other molecules such as peptides, fluorescent dyes, etc. In addition to nucleic acids that directly interact with the regulated target gene transcripts, NANPs can display decoys, wherein the oligonucleotide stretches with transcription factor binding sequences, preventing transcription initiation. The nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) is a group of five crucial transcription factors regulating the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases and cancer; as such, they are relevant targets for therapy. One therapeutic approach involves interdependent self-recognizing hybridized DNA/RNA fibers designed to bind NF-κB and prevent its interaction with the promotor region of NF-κB-dependent genes involved in inflammatory responses. Decoying NF-κB results in the inability to initiate transcription of regulated genes, showing a promising approach to gene regulation and gene therapy. The protocol described herein provides detailed steps for the synthesis of NF-κB decoy fibers, as well as their characterization using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (to confirm desired physicochemical properties and purity) and functional bioassays (to confirm desired biological activity).

Keywords: Nucleic acid nanoparticles (NANPs), Hybrid fibers, Decoys, NF-κB regulation

1. Introduction

Nucleic acid nanoparticles (NANPs) are assemblies integrating various individual functional nucleic acids into their structure [1]. These assemblies can be further rationally designed to specifically respond to trigger molecules that activate their functionalities. The conditional activation of NANPs results from a toehold interaction between (i) a pair of cooperating sense/antisense NANPs [2] and (ii) recognition of endogenous complementary nucleic acid sequence [3] or (iii) by specific interaction to protein through NANP 3D structure [4]. The interplay between NANPs or cognate molecules subsequently releases functional DNA/RNA molecules with the potential for synergistic effects.

Reconfigurable NANPs offer a promising approach to providing decoys to regulate the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), a crucial transcription factor in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases [5]. The NF-κB transcription factors form homo- or heterodimers in two distinct signaling pathways. While canonical signaling plays an important role in innate and adaptive immune responses, the alternative pathway is involved in the development of lymphoid organs, B cell survival and maturation, and osteoclast differentiation [6, 7]. The canonical pathway is triggered by pro-inflammatory cytokines and pathogen- and damage-associated molecular patterns through their receptors. The regulation through the canonical pathway plays an important role in innate immunity. However constitutively activated NF-κB promotes tumorigenesis by proliferation and survival of cancer cells. The NF-κB is expressed in cancer cells as well as in cells of the tumor microenvironment [8].

The expression of NF-κB is ubiquitous in various types of mammalian cells. We can regulate the expression and activity of NF-κB with the nanoparticles functionalized with various molecules, such as small interfering RNAs (siRNA), aptamers, and antisense oligonucleotides [9–11]. Numerous functionalized nanoparticles or simpler chimeric therapeutic nucleic acids can be targeted to a specific cell type via aptamers [12]. However, aptamer-mediated targeting remains challenging. The conditional activation of functionalized NANPs represents an alternative approach to specific cell targeting. Conditional activation doesn’t rely on specific delivery but on the presence of activating molecule, which may be co-delivered or is of cellular origin.

We developed a protocol focusing on interdependent self-recognizing hybrid DNA/RNA fibers that, upon mutual interaction in the cytoplasm, re-associate into multiple dicer substrate (DS) RNAs and DNA duplexes containing NF-κB decoys that regulate NF-κB translocation to the nucleus and thus transcription initiation of NF-κB regulated genes [13]. The protocol described herein provides a detailed recipe for the assembly, as well as physicochemical and biological characterization of NF-κB decoy DNA/RNA fibers to confirm their integrity and intended biological function.

2. Materials

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Hybrid RNA/DNA Fibers

Individual ssDNAs, ssRNAs, and fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides.

Hybridization buffer (HB): 89 mM Tris, 80 mM boric acid (pH 8.3), 2 mM magnesium acetate.

8% Native-PAGE gel (19:1 acrylamide/bis-acrylamide).

Native loading buffer (50% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1× Tris-borate buffer (pH 8.3), 0.01% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue, and 0.01% (wt/vol) xylene cyanol tracking dyes).

Native running buffer: 1X Tris buffer, 2 mM Mg2+.

0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide.

Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP Imager.

Equipment: 1.5 mL microtubes, pipettes and pipette tips, microcentrifuge, vortex, heat block.

2.2. Assessment of Biological Activity of NF-κB Decoy Fibers

2.2.1. Primary Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) for Analysis of Interferon and Cytokine Secretion (to Assess Anti-inflammatory Potential)

Freshly collected PBMC from healthy human donors.

Ultrapure K12 E. coli LPS.

2.2.2. Reporter Cell-Based Assay (to Assess Anti-inflammatory Potential)

HEK-Blue-hTLR4 cells.

Ultrapure K12 E. coli LPS.

Lipofectamine 2000 (L2K).

96-well plates.

Quanti-Blue.

2.2.3. Immunofluorescence Analysis for Detection of NF-κB in Cancer Cell Line (to Assess Biological Activity)

A375 melanoma cells.

24-well plates.

1x PBS.

5% BSA (bovine serum albumin).

Anti-NF-κB, p65 subunit monoclonal antibody (MAB3026, Millipore, 1:100).

AlexaFluor® 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, 1:1000).

Hoechst (25 ug/mL).

Rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, 1:200).

Mounting solution: Glycerol: PBS (1:1).

Fluorescence microscope EVOS FL Auto Imaging System.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism software.

3. Methods

3.1. Synthesis and Physicochemical Characterization of Fibers

Mix equimolar concentrations of individual monomers of the hybrid fibers (see Note 1) in the hybridization buffer.

Heat mixture to 95 °C for 2 min.

Snap cool mixture in ice and then incubate at room temperature for 20 min.

Store fibers at 4 °C until needed.

- Evaluate the assembly of fibers by using 8% native-PAGE gel (see Note 2):

- Mix the reagents to make the native PAGE: 10.5 mL ddiH2O, 3 mL 40% 19:1 acrylamide/bis-acrylamide (from the refrigerator), 1.5 mL 10X TB, 30 μL of 1 M MgCl2, 9 μL of TEMED, and 150 μL of 10% APS, to prepare a Bio-Rad Mini 1.0 mm gel.

- Pour in the gel and let polymerize for 10–15 min.

- Pre-run the gel in 1X TB (supplemented with 2 mM Mg2+) at 150 volts (and 25 mA) for 5 min on the “volt” setting.

- Mix samples with native loading buffer (1:1).

- Load samples and run gel in 1X TB (2 mM Mg2+) at constant 300 volts (and 150 mA) for 20 min.

- Stain the gel in diluted ethidium bromide for 5 min, and wash twice in ddiH2O. Skip this step for fluorescence-labeled oligos.

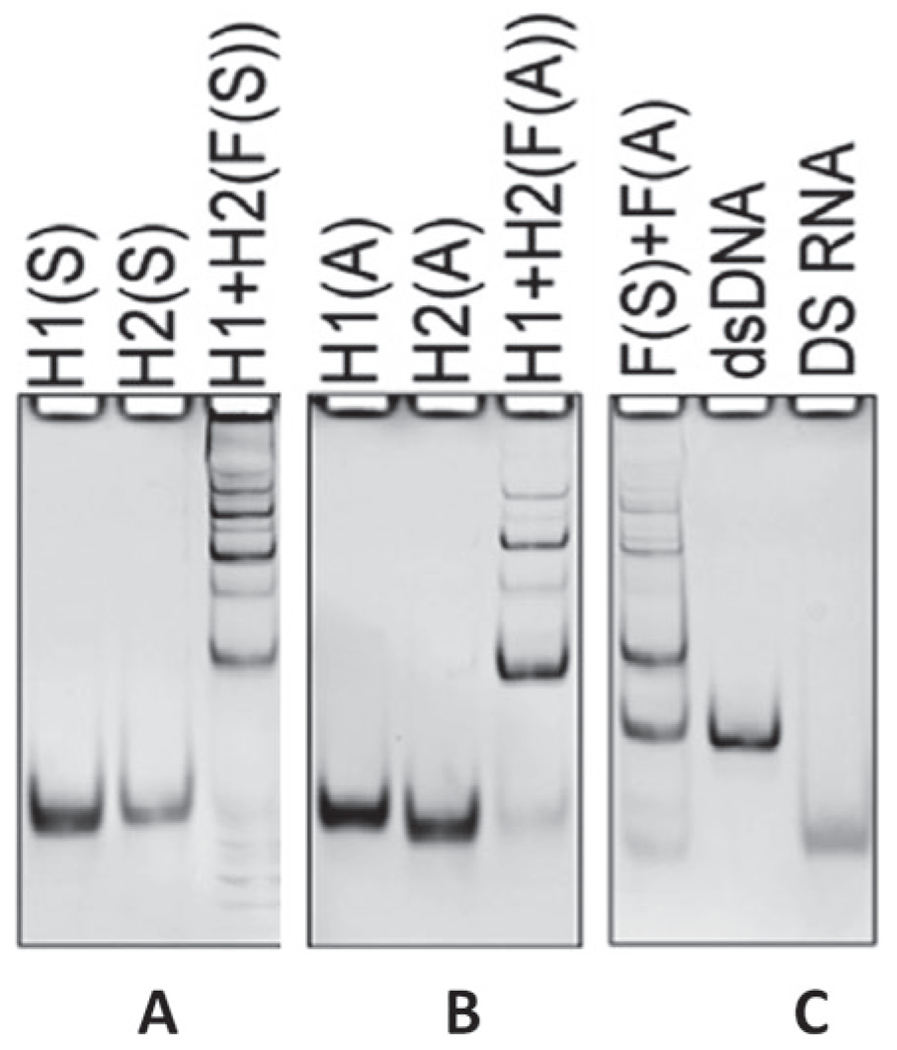

- Image the gel using ChemiDoc to confirm pure assemblies (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Native PAGE confirming the formation of fibers. (Reproduced from Ref. [13])

3.2. Assessment of NF-κB Biological Activity in Cell Models

3.2.1. Primary Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) and Whole-Blood Culture for Analysis of Cytokine Secretion (See Note 3)

Collect blood from pre-screened healthy donors following institutional review board-approved protocol using BD Vacutainer tubes containing Li-heparin as the anticoagulant, and use collected blood within 2 h.

Use whole-blood cultures to analyze chemokine and cytokine induction.

Use PBMC cultures using myeloid cells for type I interferon analysis following the standardized protocol [14].

Analyze supernatants using a chemiluminescence-based multiplex system.

Analyze duplicates of each supernatant on the multiplex plate.

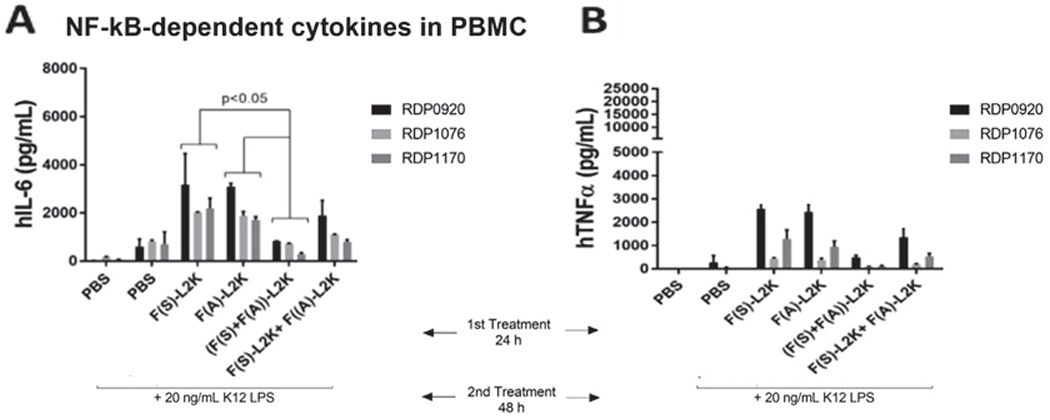

Use 20 ng/mL LPS as positive control for the PBMC assay for cytokine analysis and whole-blood assay (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Assessment of NF-κB-dependent cytokines in PBMCs. First PBMCs were treated for the 24 h with controls or fibers, and after 24 hours they were stimulated with 20 ng/mL of ultrapure bacterial K12 LPS. Levels of IL-6 (a) and TNFα (b) were measured in the supernatants by multiplex ELISA. (Reproduced from Ref. [13])

3.2.2. Reporter Cell-Based Assay for Assessment of NF-κB-Dependent SEAP (See Note 4)

Seed HEK-Blue-hTLR4 cells in a 96-well plate and incubate overnight for cell adherence.

Mix and pre-incubate NANP samples with L2K for 30 min before transfection at room temperature.

Transfect cells with NANPs and incubate for 24 h; triplicates are used for each sample.

Add 25 ng/mL LPS/well to cells 24 h post-transfection and incubate for 24 h.

Mix 20 μL of cell supernatant with 180 μL of Quanti-Blue in a 96-well plate and incubate at 37 °C for up to 3 h.

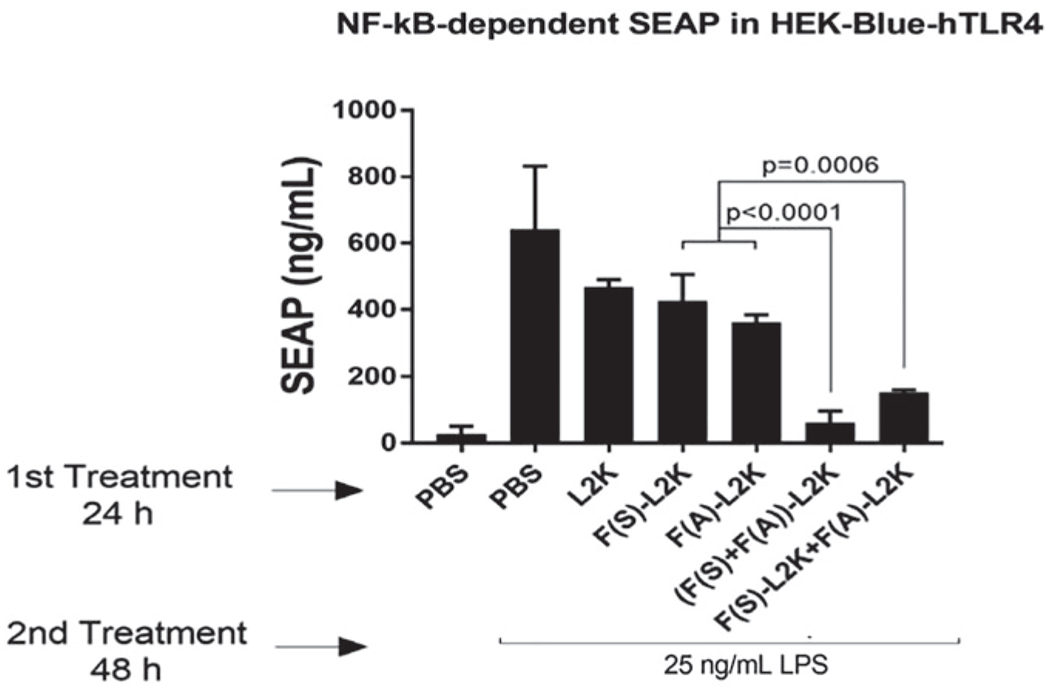

Read the absorbance at 620 nm using a plate reader to measure SEAP production (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Assessment of NF-κB-dependent SEAP in the reporter cell line HEK-Blue hTLR4. Cells were transfected with fibers and, after 24 h, stimulated with ultrapure K12 LPS. Then, cells were incubated for another 24 h, and the levels of SEAP were measured in supernatants. (Reproduced from Ref. [13])

3.2.3. Immunofluorescence Analysis for Detection of NF-κB in Cancer Cells (See Note 5)

Seed A375 melanoma cells at 2.5 × 104 cells/well in a 24-well plate.

Transfect A375 melanoma cells onto uncoated glass coverslips.

Treat designated cells with LPS at 10 μg/mL for 4 h, and fix with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min.

Wash with 1× PBS.

Permeabilize cells with 0.2% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS for 5 min.

Wash cells, and then block cells using 5% BSA for 1 h at room temperature.

Incubate cells overnight at 4 °C with anti-NF-κB, p65 subunit (1:100).

Wash cells with 1x PBS three times for 10 minutes each.

Incubate cells with Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000) and Hoechst (25 μg/mL) at room temperature for 90 min.

Incubate cells with Rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin antibody (1:200) for F-actin staining for 15 min at room temperature.

Wash cells with 1× PBS three times for 10 minutes each.

Mount cells in glycerol: PBS (1:1) solution.

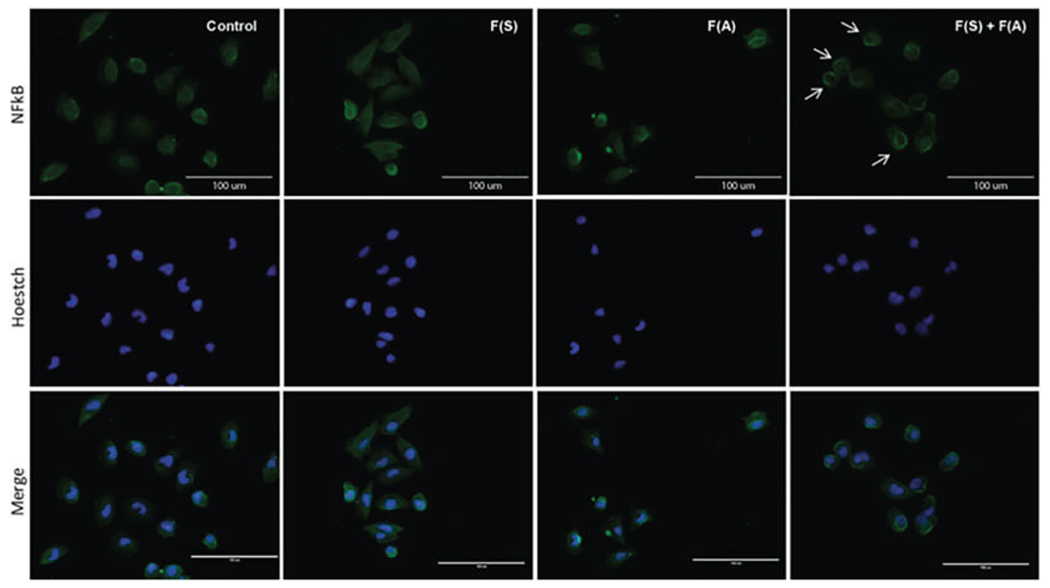

Visualize using the fluorescence microscope (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Immunofluorescence analysis for detection of NF-κB in cancer cells. A375 melanoma cells transfected with fibers were treated with LPS for 4 h. Cells were fixed and permeabilized and then processed for immunofluorescence staining with NF-κB (p65) using Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibodies (green) and Hoechst (blue). Panel F(S) + F(A) reveals perinuclear accumulation of NF-κB (arrows), indicating that re-associated fibers impair NF-κB nuclear translocation induced by LPS (scale bar: 100 μm). (Reproduced from Ref. [13])

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Present results as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Perform statistical analyses on data using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) using GraphPad Prism software.

Consider a p-value of <0.05 as statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R35GM139587 (to K.A.A.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

4 Notes

For the fibers’ assembly, the sequence of strands used is shown below.

To assemble fibers having the sense/antisense strands: mix GFP fiber sense/antisense DNA strand 1 with GFP fiber sense/antisense DNA strand 2 with DS RNA sense/antisense against GFP in (1:1:2) ratio.

GFP fiber sense DNA strand 1:

5′ –AAGGGATTTCCCTCGGTGGTGCAGATGAACTTCAGGGTcaTTCCCTAAAGGGA.

GFP fiber sense DNA strand 2:

5′ – AGGGAAATCCCTTCGGTGGTGCAGATGAACTTCAGGGTcaTCCCTTTAGGGAA.

GFP fiber antisense DNA strand 1:

5′ –TCCCTTTAGGGAATGACCCTGAAGTTCATCTGCACCACCGAGGGAAATCCCTT.

GFP fiber antisense DNA strand 2:

5′ – TTCCCTAAAGGGATGACCCTGAAGTTCATCTGCACCACCGAAGGGATTTCCCT.

DS RNA sense against GFP:

5′ –ACCCUGAAGUUCAUCUGCACCACCG.

DS RNA antisense against GFP:

5′ –CGGUGGUGCAGAUGAACUUCAGGGUCA.

DS RNA sense labeled with Alexa 488:

5′ –ACCCUGAAGUUCAUCUGCACCACCG-Alexa488.

DS RNA antisense labeled with Alexa 546:

5′ –Alexa 546-CGGUGGUGCAGAUGAACUUCAGGGUCA

When fibers are visualized on 8% native-PAGE gel, bands will appear smeared instead of one distinct, clear band; also, the sample may also get trapped in the well. These findings are attributed to the different lengths that fibers can have when assembled.

This section focuses on assessing the intended anti-inflammatory efficacy of NF-κB decoy delivered through fibers. In this case LPS is used as a positive control for NF-κB induction. When cells are treated with fibers and then induced with LPS, the intended efficacy of the NF-κB decoys should be proven, which is reflected in a decreased cytokine production as compared to samples not treated with NF-κB decoys.

The full protocol for the use of human PBMCs to define immunological properties of NANPs is available (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41596-020-0393-6).

Reporter cell line HEK-Blue hTLR4 is used for assessment of NF-κB-dependent SEAP by assessing the anti-inflammatory effect of the fibers. TLR4 engagement triggers activation of NF-κB which controls the expression of SEAP in this model. When cells are treated with only the positive control (LPS), a high concentration of NF-κB-dependent SEAP is produced, indicating the trigger of NF-κB, hence giving a positive response, while cells transfected with decoy fibers and induced with LPS would show a significantly diminished concentration of SEAP as compared to cells treated with LPS alone. This is attributed to the binding of the NF-κB decoy to the activated NF-κB and hindering its translocation into the nucleus, controlling the expression of SEAP.

Immunofluorescence analysis for detection of NF-κB in cancer cells. A375 melanoma cells are used to assess the biological activity of the fibers. Expected results would show that the re-associated fibers impair NF-κB nuclear translocation induced by LPS. Hence, NF-κB biological activity is impaired.

References

- 1.Afonin KA, Viard M, Koyfman AY, Martins AN, Kasprzak WK, Panigaj M et al. (2014) Multifunctional RNA nanoparticles. Nano Lett 14(10):5662–5671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halman JR, Satterwhite E, Roark B, Chandler M, Viard M, Ivanina A et al. (2017) Functionally-interdependent shape-switching nanoparticles with controllable properties. Nucleic Acids Res 45(4):2210–2220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bindewald E, Afonin KA, Viard M, Zakrevsky P, Kim T, Shapiro BA (2016) Multistrand Structure Prediction of Nucleic Acid Assemblies and Design of RNA Switches. Nano Lett 16(3):1726–1735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Douglas SM, Bachelet I, Church GM (2012) A logic-gated nanorobot for targeted transport of molecular payloads. Science 335(6070):831–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D, Sun SC. (2017) NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu H, Lin L, Zhang Z, Zhang H, Hu H (2020) Targeting NF-kappaB pathway for the therapy of diseases: mechanism and clinical study. Signal Transduct Target Ther 5(1):209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun SC (2017) The non-canonical NF-kappaB pathway in immunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 17(9):545–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taniguchi K, Karin M (2018) NF-kappaB, inflammation, immunity and cancer: coming of age. Nat Rev Immunol 18(5):309–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan H, Duan X, Pan H, Holguin N, Rai MF, Akk A et al. (2016) Suppression of NF-kappaB activity via nanoparticle-based siRNA delivery alters early cartilage responses to injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113(41):E6199–EE208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wurster SE, Maher LJ 3rd. (2008) Selection and characterization of anti-NF-kappaB p65 RNA aptamers. RNA 14(6):1037–1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neurath MF, Fuss I, Schurmann G, Pettersson S, Arnold K, Muller-Lobeck H, et al. (1998) Cytokine gene transcription by NF-kappa B family members in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 859:149–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Panigaj M, Johnson MB, Ke W, McMillan J, Goncharova EA, Chandler M et al. (2019) Aptamers as modular components of therapeutic nucleic acid nanotechnology. ACS Nano 13(11):12301–12321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ke W, Hong E, Saito RF, Rangel MC, Wang J, Viard M et al. (2019) RNA-DNA fibers and polygons with controlled immunorecognition activate RNAi, FRET and transcriptional regulation of NF-kappaB in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res 47(3):1350–1361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobrovolskaia MA, Afonin KA (2020) Use of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells to define immunological properties of nucleic acid nanoparticles. Nat Protoc 15(11):3678–3698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]