Abstract

The present study involves synthesis a new series of α-aminophosphonates 2a-f and 4a-d derivatives in good yield with a simple workup via Kabachnik-Fields reaction in the presence of lithium perchlorate as Lewis acid catalyst. All the newly synthesized compounds were confirmed using various physical, spectroscopic, and analytical data. The in vitro anticancer activities of each compound were evaluated against colorectal carcinoma Colon cancer (HCT-116) and Epdermoid carcinoma (HEP2) and also Human lung fibroblast normal cell line (WI38) compared with Doxorubicin. The results showed that Compounds 2a, 4b and 4d exhibited more potent inhibitory activity for Epdermoid Carcinoma (HEP2) compared with doxorubicin. For colon carcinoma cells (HCT-116) Compounds 2a, 2d and 4b gave the strongest activity among all compounds compared with doxorubicin. Moreover, all designed structures were docked into the active site of VEGFR2 and FGFR1 proteins. The result reveals that compound 2b and have the strongest inhibitory activity of the VEGFR2 and FGFR1 proteins indicating that these substances might conceivably operate as VEGFR2 and FGFR1 inhibitors and hence might take role in anticancer activities with various binding interactions. The 3D-QSAR models produced strong statistical results since they were defined by PLS factors 4 and confirmed by parameters as R2, R2 CV, Stability, F-value, P-value, RMSE, Q2, and Pearson-r.

Subject terms: Chemical biology, Computational biology and bioinformatics

Introduction

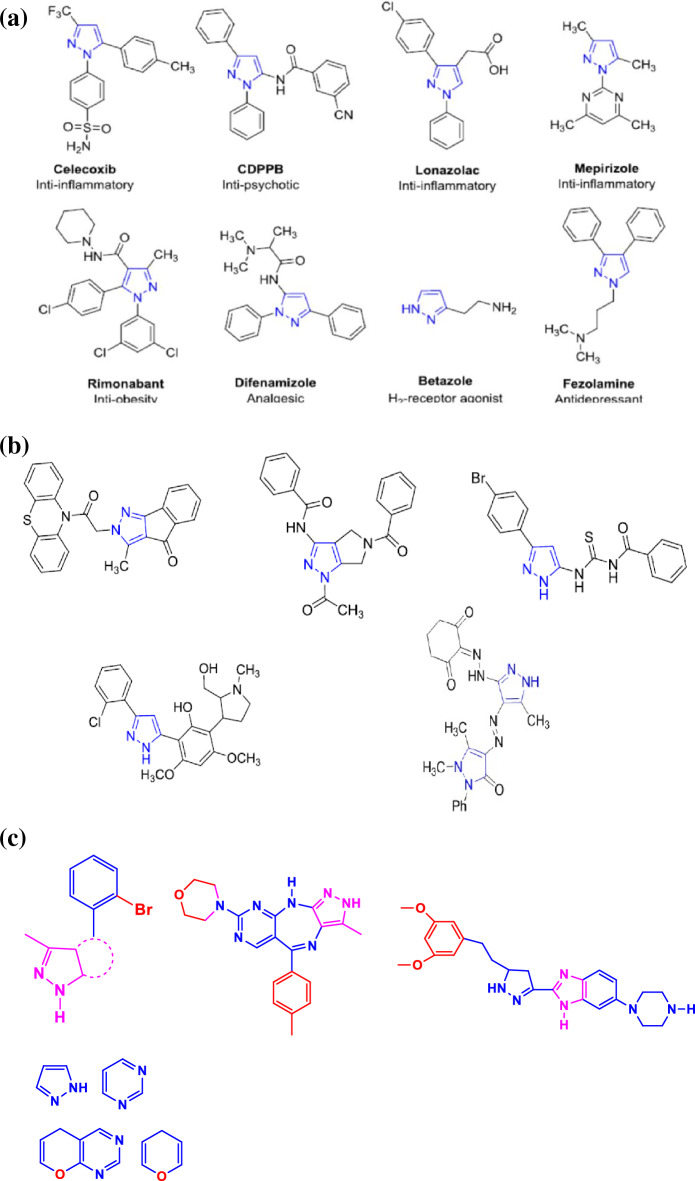

At least half of all organic chemistry research worldwide is focused on heterocyclic chemistry, which is also known as the major area of classical organic synthesis1. Heterocyclic compounds play a vitally important role in medicinal chemistry and are receiving healthy funding with a wider range of potential for processing and synthesizing a wide variety of pharmacological characteristics. Along with being widely present in natural products2. There are numerous therapeutic applications for heterocyclic compounds, including pharmacological and medicinal properties3–13. Pyrazole-containing compounds represent one of the most significant families of N-heterocycles. Due to their shown utility and adaptability as synthetic intermediates in the synthesis of key molecules in biological, physical–chemical, material science, and industrial applications, As a result, it is extremely desirable to synthesize pyrazole derivatives with a variety of structural characteristics, and numerous researchers are still working to create this useful scaffold and discover new and better uses for it. Moreover, The pyrazole moiety has been shown to have pharmacological potential by its presence in a variety of therapeutic agents, including the antipsychotic CDPPB, the anti-obesity medication rimonabant, the analgesic difenamizole, the H2-receptor agonist betazole, and the antidepressant fezolamide (Fig. 1a)14, 15.

Figure 1.

(a) Represented FDA-approved drugs containing a pyrazole nucleus. (b) Pyrazole derivatives showing anticancer activity. (c) Pyrazole derivatives showing VEGFR-2, FGFR1 inhibitory activities.

According to literature survey, a series of some new pyrazolyl derivatives were synthesized and investigated for their antitumor activity against different cancer cell lines. These results indicated that the pyrazolyl derivatives displayed antiproliferative activity in a range of human tumor cell lines, including HCT116 human colon carcinoma and Epdermoid Carcinoma (HEP2), Epdermoid Carcinoma (HEP2) and also Human lung fibroblast normal cell line (WI38) besides different tumor cell lines. For the moment, researchers have been drawn to the design of more potent pyrazole derivatives having great diversity of biological activity (Fig. 1b)14. Moreover, the literature survey results introduce novel pyrazole-based moieties as dihydro-pyrano-pyrazole and pyrazolo-pyrimidine derivatives with 2-bromophenyl moiety as promising scaffolds to produce potent VEGFR-2 inhibitors. Additionally, over the last decade, the family of the fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs) has become an attractive validated therapeutic target notably in cancer diseases.

A series of novel pyrazole-benzimidazole derivatives was identified as a selective and potent pan-FGFR inhibitor. pyrazolo[4,3-b]pyrimido[4,5-e][1,4]diazepine scaffold was identified as a selective and potent pan-FGFR and VEGFR-2 inhibitors(Fig. 1c)16–18.

The biological and therapeutic properties of 5-amino-pyrazoles as well as their flexibility in synthetic processes have recently drawn a lot of attention and given them a prominent position19. The -NH2 functionality makes 5-amino-pyrazoles one of a class of adaptable aromatic heterocycles containing nitrogen that have a high degree of controllability for creating different synthesis schemes. α-Aminophosphonates (AAPs) are most important group of organophosphorus compounds that are structural analogues of amino acids where a carboxylic substituent is substituted by phosphonic acid or related groups20. Recently, α-aminophosphonates have received enormous attention from scientific researchers in pharmaceutical and medicinal chemistry due to they have extremely high levels of wide biological activities such as anti-HIV, peptidemimics, antibacterial, antibiotics, inhibitors of serine hydrolase, herbicidal, antiviral, anticancer, enzyme inhibitors, antifungal, and anti-proliferative, enzyme inhibitors, inhibitors of serine hydrolase anti-Alzheimer and apoptosis inducing21, 22. Moreover, α-aminophosphonate derivatives containing a pyrazole moiety showed a significant inhibitory effect on acetylcholinesterase (AChE)23. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a key signalling molecule that controls the tumor angiogenesis process. VEGF overexpression was discovered in a number of cancer, including Epdermoid carcinoma (HEP2) and Colon cancer (HCT-116). All VEGF responses in endothelial cells are mediated by VEGFR-2. Therefore, VEGFR-2 should be the primary target of any new drugs being developed to treat cancers in humans that are dependent on angiogenesis24.

Various methods for the synthesis of α-aminophosphonates were reported. However, one pot Kabachnik-Fields reaction, a one-pot multicomponent synthesis involving an amine, an aldehyde, and a phosphite in the presence of a Lewis acid catalyst remains the most efficient, simple, general, and high yielding method25.

Based on these facts and keeping in view the wide range of biological activities of pyrazole moieties, and aminophosphonate scaffolds, in this work, we expect that the incorporation of these moieties in the same scaffold structure may lead to good activities and potent powerful anticancer medicines. Thus, as a continuation of our prior work in the synthesis of biologically active heterocycles26–28, we have designed and synthesized a series of new α-aminophosphonates derivatives bearing pyrazole moiety and were evaluated against references and cancer cell lines. Additionally, the newly synthesized compounds’ biological activity was examined in connection to changes in their molecular and electronic structure using density functional theory in an effort to connect theoretical and experimental results. To determine the target enzyme and the most active compound's mechanisms of action, a molecular docking simulation will be run.

Results and discussion

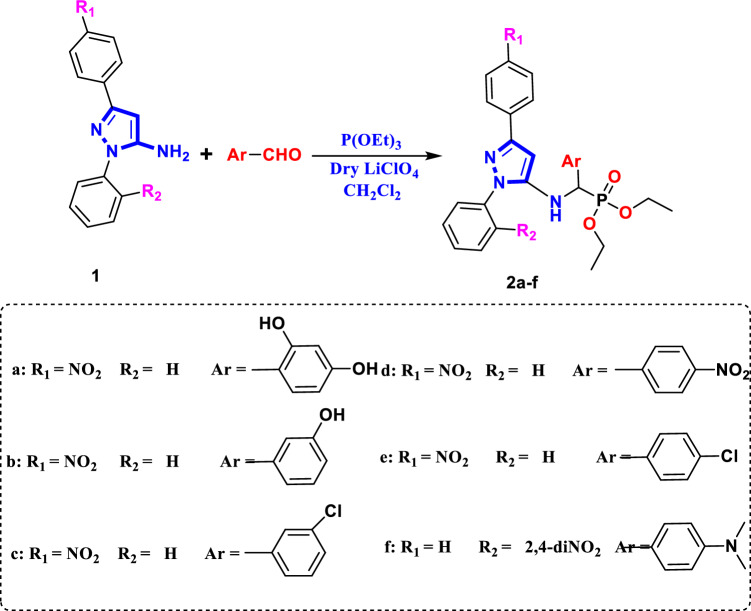

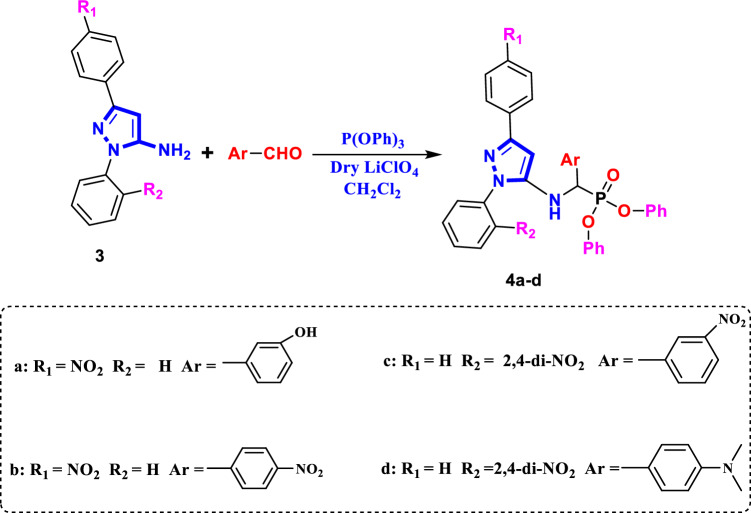

Synthesis of aminophosphonates and spectroscopic characterization

A new series of α-aminophosphonates bearing pyrazole skeleton were synthesized via three component Kabachnic-Fields reaction of 3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine 1/or 3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine 2, different aromatic aldehydes, triethylphosphite/or triphenylphosphite in CH2Cl2 in the presence of lithum perchlorate as a Lewis acid catalyst via one-pot Kabachnik–Fields25, gives Diethyl{(3-(Aryl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ylamino)(Aryl′)} methyl phosphonate 2a-f and Diphenyl{(1-(Aryl)-3-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ylamino)(Aryl′)} methyl phosphonate 4a-d, respectively, in a very good yield (Figs. 2 and 3). The structures of investigated α-aminophosphonates 2a-f and 4a-d, were confirmed by corrected elemental analysis, FT-IR, 1H NMR and 13C-NMR spectroscopy. The FT-IR spectrum was characterized by the following absorption bands: A band at 1267–1193 cm–1 is attributed to the stretching vibration of P=O group. υ (P–O–C) appeared at 1104–1011 cm–1 and υ (P–CH) is absorbed at 765–701 cm–1.The CH aromatic stretching band is absorbed at 3162–3025 cm–1, while the CH aliphatic bands are appeared at 2982–2853 cm–1. Finally, NH/OH groups are absorbed at 3464–3413 cm–1.

Figure 2.

Synthesis pathway of compounds 2a-f.

Figure 3.

Synthesis pathway of compounds 4a-d.

The 1H-NMR (DMSO) spectra of α-aminophosphonate derivatives, 2a-f, showed the following signals: δ 5.02–5.76 as singlet was assigned to P–CH and the singlet signals at the range of δ 6.23–7.12 were attributed to pyrazole–CH. The Ar–H signals appeared at the range of δ 6.32–9.26 ppm, also the –NH proton appeared at δ 5.61–5.99 and signals at δ 6.42–7.21 were attributed to pyrazole–CH. The methylene and methyl protons of P–O–CH2CH3 resonated as quarter and triplet respectively at δ 3.62–4.39 and 1.26–1.39 ppm. The 13C-NMR (DMSO) of the studied compounds are shown as the following signals at δ 146.42–167.94 and 143.32–158.29 (C=Nimine) and (C=N pyrazole ring), respectively, 139.33–148.97 (C–NO2), 54.04–66.82 (P–CH aliphatic), 81.93–89.39 (CHpyrazole), 114.35–148.34 (CAromatic). Additionally, a peak at m/z corresponding to the product’s molecular ion was visible in the mass spectrum for the all product. By using elemental microanalysis to characterize the examined substances, it was found that the calculated value and the measured value agreed well. The selected spectroscopic data are reported in the (“Experimental” section) (Figs. S1–S30 in supplementary materials).

Biological evaluation

Antitumor activity

Nitrogen-containing heterocycles exhibit anticancer effect in various types of cancer through inhibiting cell growth and induction of cell differentiation and apoptosis.

Moreover, therapeutic drugs that inhibiting EGFR and VEGFR-2 can enhance the effectiveness of cancer therapy and resolve resistance issues29.

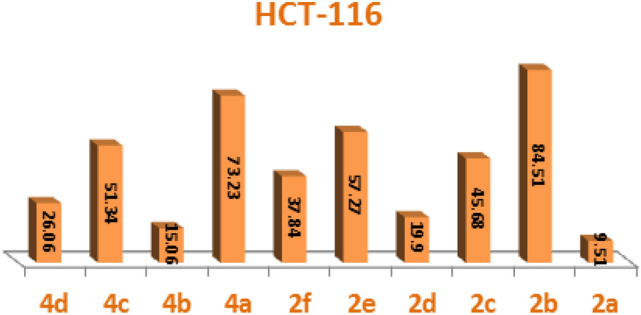

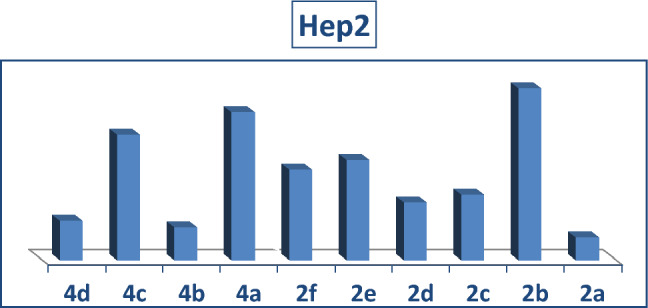

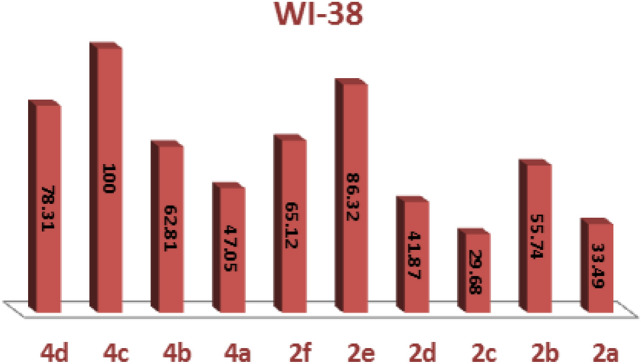

To create novel molecules with high inhibitory potentials, pyrazole derivatives were widely utilized30.The cytotoxic potency of the synthesized phosphonates, 2a-f and 4a-d was determined in vitro using the standard MTT method31 against Colorectal carcinoma Colon cancer (HCT-116) and Epdermoid Carcinoma (HEP2) and also Human lung fibroblast normal cell line (WI38), using Doxorubicin as a positive control. The IC50 values were estimated for each compound and the results are shown in (Figs. 4, 5 and 6) and summarized in (Table 1). Compounds 2a, 4b and 4d gave the highest activity for Epdermoid Carcinoma (HEP2), while the rest compounds have moderate to weak activity against the same cell line as shown in Table 1. For colon carcinoma cells (HCT-116) Compounds 2a, 2d and 4b gave the strongest activity among all compounds. Finally, all the studied phosphonate compounds have moderate to weak cytotoxicity activity on the normal cell WI-38.

Figure 4.

IC50 of compounds 2a-f and 4a-d, against colon carcinoma cells (HCT-116).

Figure 5.

IC50 of compounds, 2a-f and 4a-d, against Epdermoid Carcinoma (HEP2).

Figure 6.

IC50 of compounds 2a-f and 4a-d, against normal cell line (WI38).

Table 1.

Cytotoxic activity in compounds 2a-f and 4a-d, against 2 human tumor cells and 1 normal cell.

| Compound | In vitro cytotoxicity IC50 (µM)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 83IW | 611CCH | Hep2 | |

| XOD | 570 ± H776 | 57I ± 076I | 57H ± W708 |

| 6a | 678 ± II783 | 577 ± 370C | 573 ± C6760 |

| 2b | I7C ± 00778 | 876 ± W870C | 07C ± 3I7I8 |

| 2c | 676 ± 637HW | 67W ± 807HW | 670 ± I073I |

| 2d | 677 ± 8C7W7 | C7H ± C3735 | 67I ± IC7H0 |

| 2e | 878 ± WH7I6 | I78 ± 07767 | I76 ± 087I7 |

| 2f. | I7H ± H07C6 | 678 ± I77W8 | 673 ± 837C5 |

| 4a | 673 ± 87750 | I73 ± 7I76I | 876 ± W57IC |

| 4b | I70 ± H67WC | C7C ± C075H | C78 ± C777H |

| 4c | C55 > | I75 ± 0C7I8 | I70 ± HW7CH |

| 4d | I73 ± 7W7IC | C73 ± 6H75H | C7W ± 6C76W |

*IC50 (µM): 1–10 (very strong), 11–20 (strong), 21–50 (moderate), 51–100 (weak) and above 100 (non-cytotoxic), DOX doxorubicin.

From the above data, we could conclude that compound 2a which contain 2, 3-diOH electron donating substituent and compounds 2d and 4b which have electron withdrawing NO2 group, are the most potent derivatives against the tested cancer cell lines and also have low cytotoxic activity on the normal cell line (Table 1).

Structure–activity relationship (SAR) of studied compounds 2a-f and 4a-d

The experimental cytotoxicity of the investigated compounds to their structures was used to postulate a structure–activity relationship of the produced α-aminophosphonate derivatives:

-

(i)

The variety of substituents in the aryl aldehyde moiety of AAPs is important for the wide range of cytotoxic activity against different cell lines (HCT-116, Hep2 and WI-38), (Figs. 4, 5 and 6).

-

(ii)

Compound 2b which has one OH group in position 3 in the aryl aldehyde moiety is in more active compound towards the cell lines, but compound 2a which has 2-OH groups in position 2 and 3 in the aryl aldehyde moiety enhanced the cytotoxic activity and showed a medium cytotoxic activity against the normal lung cell WI-38 compared with doxorubicin which has OH moieties.

-

(iii)

Compound 2c which has one Cl group in position 3 in the aryl aldehyde moiety enhance the biological activity against the tested cell lines.

-

(iv)

The di-ethyl phosphonate, 2d, and the di-phenyl phosphonate compound 4b which have electron withdrawing substituent NO2 in the aryl aldehyde moiety have potent cytotoxic activity against the cell line among all compounds.

-

(v)

The di-phenyl phosphonate compound 4d which has electron donating group N(CH3) in the aryl substituted aldehyde moiety is more active than the di-ethyl phosphonate of the same substituent 2f which is may be due to the increasing number of phenyl rings which increase the resonance and accordingly increase the antitumor activity.

-

(vi)

The presence of two electron donating OH group in compounds 2a improves potency more than compound 2d which have an electron withdrawing group NO2 (Table 1).

Molecular computational calculation

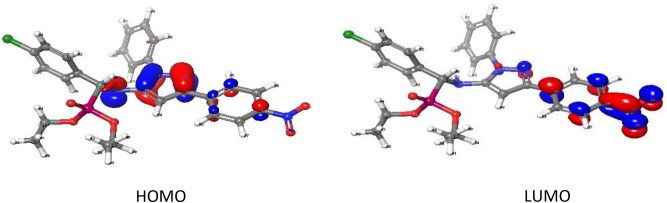

Geometry optimization and global reactivity descriptors using DFT

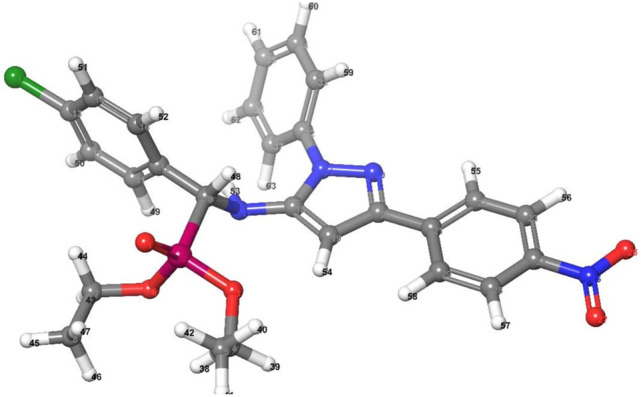

Figure 7 and Fig. S31 in supplementary materials illustrate the molecular structure and atom numbering of the examined compounds. One can come to the conclusion that the values of bond lengths and angles are close to the actual values based on the analysis of the data generated for bond lengths and angles (Tables S1–S20 in supplementary materials).

Figure 7.

Optimized molecular structure of 2e.

The “HOMO energy level” that occupies the highest molecular orbital is essentially an electron donor molecular orbital. The lowest unoccupied molecular orbital, or “LUMO”, is mostly used as an electron acceptor. Both orbitals were called frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs) (Fig. 8 and Figs. S32 and S33 in supplementary materials) have evaluated kinetic stability, electronic transitions, and electro-optical properties32. The FMOs theory proposed that aromatic compounds have a coordination site (electrophilic attack). Furthermore, most reactions are caused by the interaction of one moiety's HOMO and another’s LUMO.

Figure 8.

3D plots frontier orbital energies HOMO and LUMO using DFT method for 2e.

Table 2 displays the energy gap (ΔE = EHOMO—ELUMO), and chemical descriptors for the examined compounds. These descriptors can be assessed using the formulae provided by Pearson, and Padmanabhan et al.33, 34.

Table 2.

Calculated gas phase energy, and energetic descriptors for investigated compound.

| Compound | Gas phase energy | EH | EL | (EH -EL) | Χ | µ | η | S | ω | Ϭ | ∆Nmax | Dipole |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Kcal/mol) | (eV) | (eV) | (eV) | (eV) | (eV) | (eV) | (eV–1) | (eV) | (eV) | (e) | (debye) | |

| 2a | − 2.09 × 1003 | − 5.5368 | − 2.1340 | 3.403 | 3.835 | − 3.835 | 1.701 | 0.851 | 4.323 | 0.588 | 2.2543 | 11.735 |

| 2b | − 2.02 × 1003 | − 5.6493 | − 2.2011 | 3.448 | 3.925 | − 3.925 | 1.724 | 0.862 | 4.468 | 0.580 | 2.2766 | 10.703 |

| 2c | − 2.40 × 1003 | − 5.7892 | − 2.2519 | 3.537 | 4.021 | − 4.021 | 1.769 | 0.884 | 4.570 | 0.565 | 2.2732 | 8.202 |

| 2d | − 2.15 × 1003 | − 5.9575 | − 2.7981 | 3.159 | 4.378 | − 4.378 | 1.580 | 0.790 | 6.066 | 0.633 | 2.7713 | 5.145 |

| 2e | − 2.40 × 1003 | − 6.0750 | − 2.2486 | 3.826 | 4.162 | − 4.162 | 1.913 | 0.957 | 4.527 | 0.523 | 2.1753 | 8.256 |

| 2f. | − 2.28 × 1003 | − 5.2973 | − 3.1307 | 2.167 | 4.214 | − 4.214 | 1.083 | 0.542 | 8.196 | 0.923 | 3.8901 | 5.439 |

| 4a | − 2.32 × 1003 | − 5.5697 | − 2.1003 | 3.469 | 3.835 | − 3.835 | 1.735 | 0.867 | 4.239 | 0.576 | 2.2108 | 12.066 |

| 4b | − 2.45 × 1003 | − 6.1983 | − 2.6910 | 3.507 | 4.445 | − 4.445 | 1.754 | 0.877 | 5.633 | 0.570 | 2.5345 | 4.465 |

| 4c | − 2.53 × 1003 | − 5.9731 | − 2.9909 | 2.982 | 4.482 | − 4.482 | 1.491 | 0.746 | 6.736 | 0.671 | 3.0058 | 6.499 |

| 4d | − 2.59 × 1003 | − 5.3781 | − 2.9557 | 2.422 | 4.167 | − 4.167 | 1.211 | 0.606 | 7.168 | 0.826 | 3.4404 | 8.026 |

The additional electronic charge is derived by the formula provided by Geerlings et al. and Pearson33, 34. and is equal to the maximum number of electrons moved in the chemical process (ΔNmax).

Using the computation findings provided in Table 2:

The gas phase energy decreases with the order: 2b > 2a > 2d > 2f > 4a > 2e > 2c > 4b > 4c > 4d. This order indicates that the stability of 4d is higher than that of other compounds.

The EHOMO and ELUMO values are both negative, suggesting that the isolated compounds are stable35, 36.

Hard molecules have larger HOMO–LUMO disparities, whereas soft and active molecules have smaller energy differences. The chemical potential ‘μ’ which quantifies electrons’ ability to escape from the equilibrium structure, is decreased as follows: 4a (− 3.835 eV) > 2a (− 3.835 eV) > 2b (− 3.925 eV) > 2c (− 4.021 eV) > 2e (− 4.162 eV) > 4d (− 4.167 eV) > 2f (− 4.214 eV) > 2d (– 4.378 eV) > 4b (− 4.445 eV) > 4c (− 4.482 eV).

ΔNmax is the reaction index, which gauges the bond energy’s stability. The computation of ΔNmax reveals that 2f has the greatest value (3.8900 e), which is greater than other compounds, showing its high electron acceptance.

The dipole moment value of the 4a is greater than other compounds’ values which may increase its hydrophilic nature and, as a result, its biological potency.

Computation of vibrational frequency

A frequency calculation study was performed to determine the spectroscopic signature of substances (Fig. S34 in supplementary materials). Because the calculations were conducted for free molecules in a vacuum whereas the tests were performed for solid samples, there are modest discrepancies in theoretical and practical vibrational wavenumbers as displayed in (Fig. S34 in supplementary materials). Because of the poor symmetry of compounds, the modes of vibration are extremely complicated. Because of mixing with ring modes and substituent modes, in/out of plane, and torsion manners are the hardest to assign. Though, there are several strong frequencies in the IR spectrum that are important to define (Fig. S35 in supplementary materials) depicts the correlation graphic that described the agreement between theoretical and experimental wavenumbers. Table 3 shows the linear relationships between computed and experimental wavenumbers for all substances. For each figure, the correlation coefficient R2 was obtained, where R2 is a statistical number indicating how closely the regression line approximates the true data points. As a result, a good connection was discovered for the examined chemicals, as shown in (Fig. S35 in supplementary materials).

Table 3.

Comparison of experimental and theoretical IR spectra of investigated compounds.

| Comp. no | (FT–IR (cm–1)) | Intercept | Slope | R2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | νNH | H-νArom. | H-νAliph. | νP= O | C–O–vP | CH-νP | ||||

| 2a | Exp. | 3248 | 3029 | 2925 | 1254 | 1086 | 761 | − 58.81 ± 128.60 | 0.025 ± 1.11 | 0.99734 |

| Calc. | 3572 | 3201 | 3049 | 1270 | 1049 | 748 | ||||

| 2b | Exp. | 3413 | 3025 | 2917 | 1265 | 1006 | 700 | − 22.77 ± 34.05 | 0.009 ± 1.06 | 0.99957 |

| Calc. | 3593 | 3201 | 3050 | 1271 | 1051 | 726 | ||||

| 2c | Exp. | 3435 | 3029 | 2982 | 1193 | 1104 | 758 | − 50.81 ± 80.41 | 0.021 ± 1.06 | 0.99793 |

| Calc. | 3545 | 3203 | 3059 | 1256 | 1041 | 712 | ||||

| 2d | Exp. | 3430 | 3068 | 2853 | 1230 | 1083 | 764 | − 42.92 ± 91.13 | 0.018 ± 1.08 | 0.99855 |

| Calc. | 3578 | 3207 | 3066 | 1235 | 1040 | 758 | ||||

| 2e | Exp. | 3447 | 3162 | 2922 | 1239 | 1069 | 765 | − 33.49 ± 42.90 | 0.014 ± 1.04 | 0.99908 |

| Calc. | 3565 | 3205 | 3059 | 1262 | 1066 | 750 | ||||

| 2f. | Exp. | 3422 | 3065 | 2919 | 1267 | 1011 | 701 | − 35.82 ± 6.28 | 0.015 ± 1.029 | 0.99889 |

| Calc. | 3520 | 3198 | 2997 | 1255 | 1043 | 773 | ||||

| 4a | Exp. | 3432 | 3032 | – | 1234 | 1015 | 701 | − 11.70 ± 26.63 | 0.005 ± 1.06 | 0.9999 |

| Calc. | 3598 | 3205 | – | 1275 | 1052 | 717 | ||||

| 4b | Exp. | 3432 | 3065 | 2925 | 1235 | 1025 | 765 | − 22.55 ± 29.23 | 0.010 ± 1.04 | 0.99962 |

| Calc. | 3543 | 3206 | – | 1238 | 1052 | 781 | ||||

| 4c | Exp. | 3434 | 3063 | 2924 | 1237 | 1064 | 764 | − 15.12 ± 83.96 | 0.006 ± 1.07 | 0.99984 |

| Calc. | 3607 | 3202 | – | 1222 | 1057 | 755 | ||||

| 4d | Exp. | 3464 | 3025 | 2921 | 1252 | 1080 | 732 | − 49.80 ± 48.13 | 0.021 ± 1.04 | 0.99795 |

| Calc. | 3556 | 3198 | 2987 | 1220 | 1057 | 773 | ||||

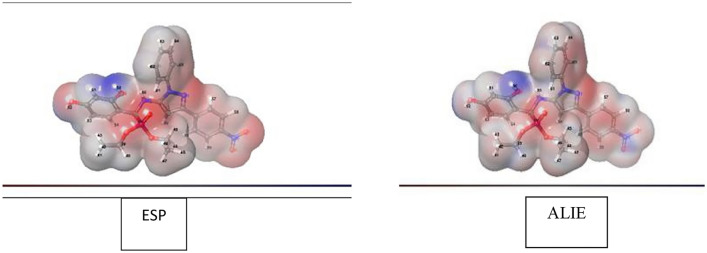

Electrostatic potential (ESP) and average local ionization energy (ALIE) properties on the molecular surface

Electrostatic potential V(r) and average local ionization energy (r) of the investigated compounds have been demonstrated to be dynamic guides to its reactive performance37.

Figure 9 and supplementary material (Figs. S36 and S37) depicted the electrostatic potential V(r) and average local ionization energy (r) of all compounds. Also, computed molecular surface data recorded in Table 3 and the following parameters are listed in this table:

The most positive VS,max and the most negative VS,min.

The whole surface potential value S, with its positive averages and negative averages .

Most positive S,max and most negative S,min, and the average over the surface of the local ionization energy S,ave.

Internal charge transfer (local polarity) Π, is derived as a sign of internal charge separation and is present even in molecules with zero dipole moment due to symmetry.

The variances,, and describe the intensities and variations of the positive, negative, and overall surface potentials, respectively38.

An electrostatic balancing parameter ν, that indicates the degree of equilibrium between positive and negative potentials; it has a maximum value of 0.25 when = .

Figure 9.

The surface structure of ESP and ALIE using DFT method for 2a.

Table 4 shows that 2a has the largest Π with value 12.52 kcal/mol followed by 2b. This is because to their strong polar structures. While 2c exhibits lowest value of Π = 10.16 kcal/mol and may be related to its structural symmetry.

Table 4.

Computed molecular surface properties (ESP) and (ALIE).

| Compound | Vs, min | Vs, max | S | ν | Π | S, min | S, max | S | S, ave | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | − 39.10 | 61.78 | 0.78 | 12.33 | − 12.84 | 117.43 | 107.86 | 225.29 | 0.250 | 12.52 | 189.27 | 381.58 | 267.27 | 22.79 |

| 2b | − 38.02 | 58.37 | 0.79 | 11.52 | − 12.58 | 73.07 | 102.34 | 175.41 | 0.243 | 11.92 | 192.16 | 375.08 | 267.06 | 21.05 |

| 2c | − 37.36 | 28.3 | 1.46 | 10.11 | − 10.69 | 38.38 | 95.32 | 133.69 | 0.205 | 10.16 | 193.92 | 351.37 | 266.53 | 20.70 |

| 2d | − 36.12 | 34.45 | 3.44 | 11.88 | − 12.01 | 44.80 | 93.45 | 138.25 | 0.219 | 11.18 | 198.19 | 366.83 | 273.56 | 20.49 |

| 2e | − 37.86 | 28.56 | 2.42 | 11.06 | − 11.66 | 41.59 | 115.89 | 157.48 | 0.194 | 10.88 | 197.39 | 350.82 | 267.00 | 20.99 |

| 2f. | − 36.81 | 29.96 | 1.08 | 10.23 | − 13.03 | 33.47 | 67.45 | 100.92 | 0.222 | 11.12 | 200.02 | 372.03 | 270.14 | 21.46 |

| 4a | − 39.53 | 60.9 | 0.56 | 11.61 | − 11.61 | 75.18 | 93.02 | 168.20 | 0.247 | 11.59 | 190.00 | 380.37 | 264.67 | 23.28 |

| 4b | − 35.03 | 37.36 | 3.99 | 12.1 | − 11.68 | 48.15 | 90.56 | 138.71 | 0.227 | 11.04 | 205.19 | 363.89 | 272.38 | 21.14 |

| 4c | − 38.51 | 60.02 | 1.09 | 12.16 | − 11.48 | 90.48 | 66.21 | 156.68 | 0.244 | 11.80 | 198.28 | 378.52 | 268.13 | 22.92 |

| 4d | − 31.64 | 44.58 | 1.45 | 11.6 | − 11.48 | 49.65 | 57.73 | 107.38 | 0.249 | 11.42 | 199.24 | 367.48 | 267.99 | 21.19 |

Units: Vs, min, Vs, max, S,, , Π, S, min, S, max, S and S, ave are in kcal/mol, , , are in (kcal/mol)2; ν is unitless.

The positive surface potential () and negative surface potential () of 2a are strong with balanced with ν = 0.250. While, the weaker surface potentials with ν = 0.194 is related to 2e. Furthermore, the largest value of for 2a shows the strong and variable + ve and -ve surface potentials.

Figure 9, is presented the VS(r) and S(r) on surfaces of 2a as a representative example and shows the locations of the various most positive, VS,max and most negative, VS,min as well as the highest, S,max and lowest, S,min. On a particular molecular surface, there are frequently many local minima and maxima of each attribute. The highest negative electrostatic potential on the surface of 2a is related to the oxygen (O27), VS,min = − 39.1 kcal/mol, followed by a weaker value of − 39.07 kcal/mol on the oxygen (O28). As a result, VS(r) incorrectly guess electrophilic attack to arise specially at the oxygen atom. However, the lowest value of S(r) is found on the (C20), with S,min = 189.27 kcal/mol; as well as, there is an S,min by the nitrogen (N31), but it is significantly higher, 198.28 kcal mol–1. Thus, S(r) demonstrates that the least-tightly-bound electrons, and most reactive are at (C20), correctly suggesting that these sites are more vulnerable to electrophiles. On contrast, the extremely significantly positive electrostatic potential of hydrogen (H50), VS,max = 61.78 kcal/mol, and the VS,min = 7.16 kcal/mol of the hydrogen (H41) show their proclivity for noncovalent H-bonding as a donor.

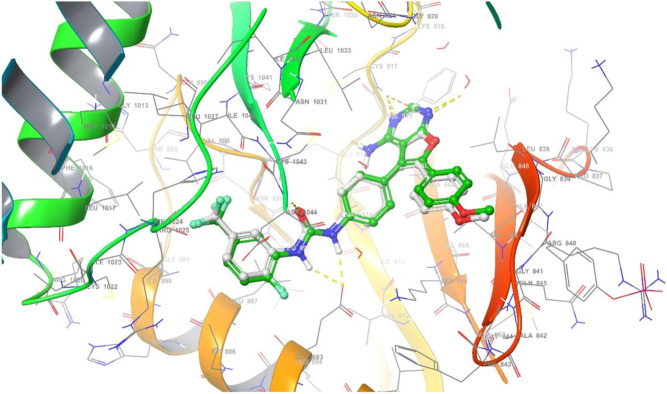

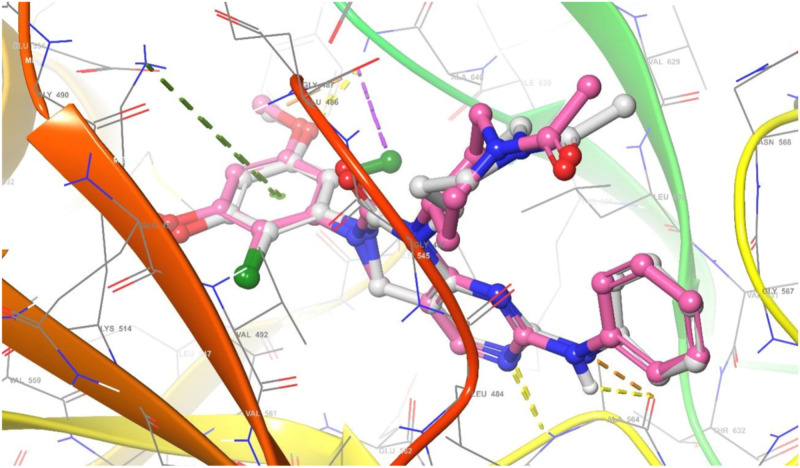

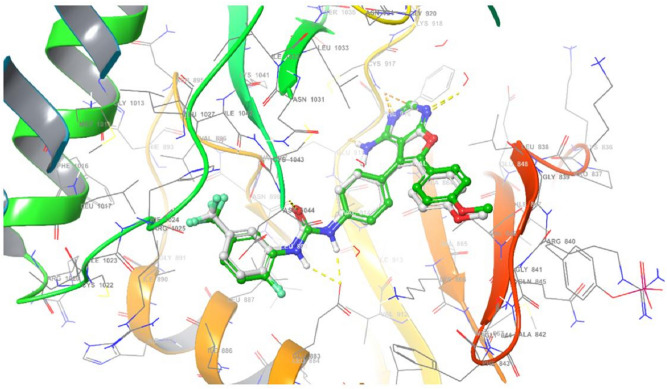

Molecular docking

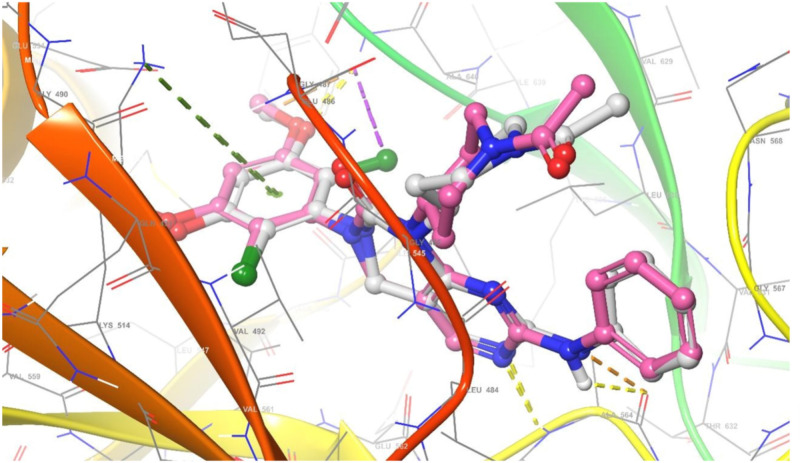

Molecular docking with VEGFR‐2 and FGFR1 proteins

The relevance of molecular docking in drug development is well acknowledged. According to the Glide S-score, the Maestro programme was used to dock the most extensive docking pocket and hits (Tables 5 and 6). Higher Glide S-score and lower RMSD values were used to identify the best docking hit compounds. Thus, the results in Table 5, reveals that the standard drug Doxorubicin exhibits the highest inhibitory activity against both proteins. Furthermore, the compounds 2b and 2a have the strongest inhibitory activity of the VEGFR2 and FGFR1 proteins, respectively. The sequence of inhibitory activity to the VEGFR2 protein is 2b > 2f > 4a > 2a > 4b > 4d > 2e > 2c > 2d. While the sequence of inhibitory action to the FGFR1 protein is 2a > 2b > 2f > 4d > 4a. Furthermore, 4c doesn’t exhibit any interactions with the VEGFR‐2 protein. Also compounds 4c, 2e, 2d, 4b, and 2c don’t show any interactions with the FGFR1 protein. From these data, one can notice that compound 4c has no interaction with FGFR1 protein and agree with experimental data of in vitro cytotoxicity against WI38 (IC50 > 100). The examined substances demonstrate that H-donor and H-acceptor interactions are the most common kind of interaction with VEGFR2 and FGFR1 receptors (Figs. 10, 11 and Figs. S38–S45 in supplementary materials). The interactions of chemical 2a with both proteins were shown as illustrative instances in (Figs. 10 and 11). From VEGFR‐2-2a interaction (Fig. 10), hydrogen donor interaction from the hydroxyl group of 2a to water molecule with distance 1.83 Å, in addition, H-acceptor interactions from water molecule to (P-O) group, PTR1052 to (N=O) and LYS1053 to (N=O) with distances 1.97, 2.22 and 2.74 Å, respectively. While the interaction of 2a with FGFR1 protein (Fig. 11) exhibits hydrogen donor interaction from the hydroxyl group of 2a to ASP641 and hydrogen acceptor interaction from LYS514 to the same hydroxyl group of 2a with distances 1.63 and 2.39 Å, respectively. The good interactions of 2a with both receptors may be due to the highest positive and negative surface potentials of 2a obtained from electrostatic potential calculations. The molecular docking result for the interactions of investigated compounds, with both proteins reveals that the most common types of interactions are hydrophobic interactions, such as π-cation, as well as H-acceptor, H-donor, halogen bond, and salt bridge interactions.

Table 5.

Molecular docking glid G-scoring, RMSD, interaction results of the investigated compounds towards VEGFR‐2 receptor (PDB ID: 1YWN).

| Compounds | Glid G-score | RMSD | Interaction | Type | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Re-docked inhibitor | − 12.827 | 0.618 | NH→GLU883 | H-Bond | 1.99, 2.23 |

| NH2→GLU915 | H-Bond | 2.08 | |||

| H2O→(C=N) | H-Bond | 2.46 | |||

| ASP1044→(C=O) | H-Bond | 2.23 | |||

| Doxorubicin | − 4.988 | 1.667 | OH→ASP1026 | H-Bond | 1.98 |

| OH→ASP1026 | H-Bond | 1.64 | |||

| OH→ASN1031 | H-Bond | 2.46 | |||

| AlA842→OH | H-Bond | 1.93 | |||

| 2e | − 2.862 | 1.313 | GLU883--(N+–O) | Salt bridge | 3.41 |

| Cl→GLU915 | Halogen bond | 3.09 | |||

| CYS917→Cl | Halogen bond | 2.46 | |||

| 2f. | − 4.466 | 0.915 | ARG1030→(N=O) | H-Bond | 1.95 |

| ASN921→(N=O–) | H-Bond | 2.34 | |||

| 4d | − 3.014 | 1.451 | ARG840→(N=O) | H-Bond | 2.62 |

| ARG1030--(N=O–) | Salt bridge | 3.40 | |||

| 4c | No interaction | ||||

| 2d | − 2.774 | 0.982 | GLU883--(N+–O) | Salt bridge | 3.15 |

| LYS866--Ar.ring | π-cation | 6.52 | |||

| 4b | − 3.637 | 1.331 | LYS866--Ar. ring | π-cation | 3.15 |

| GLU883--(N+–O) | Salt bridge | 3.23 | |||

| ARG1030--(N=O–) | Salt bridge | 3.91 | |||

| LYS1053--(N=O–) | Salt bridge | 4.38 | |||

| 2a | − 4.132 | 1.454 | OH→H2O | H-Bond | 1.83 |

| H2O→(P–O) | H-Bond | 1.97 | |||

| PTR1052→(N=O) | H-Bond | 2.22 | |||

| LYS1053→(N=O) | H-Bond | 2.74 | |||

| 2b | − 4.763 | 0.000 | ASP1044→(C=N) | H-Bond | 2.40 |

| OH→H2O→ASP1044 | H-Bond via H2O molecule | 1.86, 1.99 | |||

| OH→H2O→GLU883 | H-Bond via H2O molecule | 1.86, 2.17 | |||

| OH→H2O←LYS866 | H-Bond via H2O molecule | 1.86, 2.44 | |||

| 4a | − 4.303 | 1.077 | OH→GLY844 | H-Bond | 2.09 |

| NH→LEU838 | H-Bond | 2.74 | |||

| ASP1026--(N+–O) | Salt bridge | 5.00 | |||

| 2c | − 2.798 | 1.289 | GLU883--(N+–O) | Salt bridge | 3.41 |

Glide G-score: Kcal/mol, RMSD and distance: Å.

Table 6.

Molecular docking glid G-scoring, RMSD, interaction results of the investigated compounds towards FGFR1 receptor (PDB ID: 5UR1).

| Compounds | Glid G-score | RMSD | Interaction | Type | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Re-docked inhibitor | − 6.290 | 0.792 | NH→ALA564 | H-Bond | 2.34 |

| ASP641→(C–O) | H-Bond | 2.17 | |||

| ALA564→(C = N) | H-Bond | 2.34 | |||

| LYS514—Ar. ring | π-cation | 5.51 | |||

| ASP641→Cl | halogen bond | 2.92 | |||

| Doxorubicin | − 5.760 | 0.565 | OH→ASN628 | H-Bond | 1.97 |

| ASN568→(C=O) | H-Bond | 2.58 | |||

| ASP641→(C=O) | H-Bond | 2.63 | |||

| ASP641→(C–O) | H-Bond | 2.60 | |||

| LYS514—Ar. ring | π-cation | 5.19 | |||

| 2e | No interaction | ||||

| 2f | − 3.015 | 0.814 | ARG576→(N=O) | H-Bond | 1.85 |

| ARG576—(N=O–) | Salt bridge | 4.83 | |||

| LYS566—(N=O–) | Salt bridge | 4.79 | |||

| LYS482—Ar. ring | π-cation | 6.31 | |||

| 4d | − 2.002 | 0.789 | LYS482—(N=O–) | Salt bridge | 2.9 |

| LYS482—Ar. ring | π-cation | 6.29 | |||

| 4c | No interaction | ||||

| 2d | No interaction | ||||

| 4b | No interaction | ||||

| 2a | − 5.440 | 1.900 | OH→ASP641 | H-Bond | 1.63 |

| LYS514→OH | H-Bond | 2.39 | |||

| 2b | − 3.744 | 1.764 | ASP641→OH | H-Bond | 2.06 |

| 4a | − 1.978 | 1.925 | NH→ASP641 | H-Bond | 2.1 |

| 2c | No interaction | ||||

Glide G-score: Kcal/mol, RMSD and distance: Å.

Figure 10.

Superimposition of re-docked inhibitor (green) onto co-crystallized complex (grey) in the active site (RMSD = 0.792 Å) towards VEGFR‐ 2 receptor.

Figure 11.

Superimposition of re-docked inhibitor (violet) onto co-crystallized complex (grey) in the active site (RMSD = 0.618 Å) towards FGFR1 receptor.

One possible source of the difference between the theoretical and experimental data is the limitations of molecular docking computational calculations. These calculations rely on mathematical functions, algorithms, and active site sensitivity to predict the interactions between drugs and biological targets. However, these calculations do not consider the factors that affect the drug delivery method or mechanism, the experimental variations, or the biological target properties39.

Docking validation

The re-docking was done to test the docking strategy and efficiency. The re-dockin approach used the same procedures as earlier. The peptide original inhibitor was precisely attached to the active site pocket of the VEGFR2 receptor by completely 5- hydrogen bonds were formed with distances (1.99, 2.23), 2.08, 2.46, and 2.23 Å. While the original inhibitor linked to the active site pocket of FGFR1 receptor through four hydrogen bonds with distances 2.34, 2.17, 2.34, and 2.92 Å as well as π-cation interaction between the aromatic ring and LYS514 with distance 5.51 Å. The re-docked original ligand was overlaid onto the native co-crystallized (Figs. 12 and 13). The re-docked inhibitor linked to VEGFR‐2 and FGFR1 receptors has molecular docking scoring (-12.827 and -6.290 kcal mol−1) and the RMSD of (0.618 and 0.792 Å), respectively).

Figure 12.

Superimposition of re-docked inhibitor (green) onto co-crystallized complex (grey) in the active site (RMSD = 0.792 Å) towards VEGFR‐2 receptor.

Figure 13.

Superimposition of re-docked inhibitor (violet) onto co-crystallized complex (grey) in the active site (RMSD = 0.618 Å) towards FGFR1 receptor.

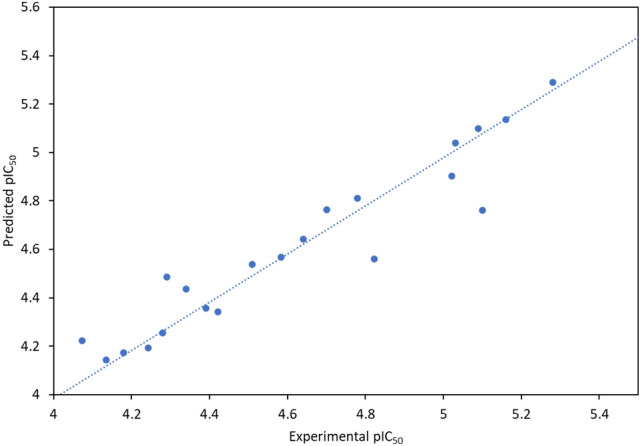

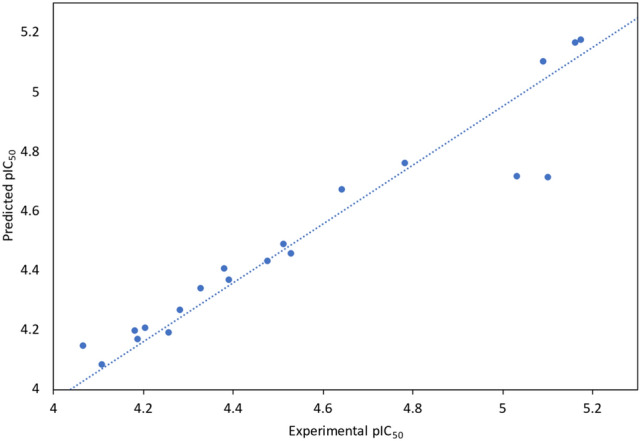

3D- QSAR studies

To create the model, we employed the atom-based QSAR module. For all categories, we used four PLS factors. We used the cross-correlation coefficient40 to assess the models’ prediction abilities (Table 7). The comprehensive data for the QSAR investigation is shown in Table 8. Each set’s best model result is presented in this table.

Table 7.

Prediction of QSAR models on drug compounds.

| Compounds | VEGFR2 model | FGFR1 model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental pIC50 | Predicted pIC50 | Prediction error | Experimental pIC50 | Predicted pIC50 | Prediction error | |

| 2a | 5.022 | 4.902 | − 0.120 | 4.475 | 4.431 | − 0.044 |

| 2b | 4.073 | 4.223 | 0.150 | 4.254 | 4.192 | − 0.062 |

| 2c | 4.340 | 4.437 | 0.097 | 4.528 | 4.459 | − 0.069 |

| 2d | 4.701 | 4.763 | 0.062 | 4.378 | 4.408 | 0.030 |

| 2e | 4.242 | 4.193 | − 0.049 | 4.064 | 4.148 | 0.084 |

| 2f | 4.422 | 4.343 | − 0.079 | 4.186 | 4.170 | − 0.016 |

| 4a | 4.135 | 4.143 | 0.008 | 4.327 | 4.342 | 0.015 |

| 4b | 4.822 | 4.560 | − 0.262 | 4.202 | 4.208 | 0.006 |

| 4c | 4.290 | 4.487 | 0.197 | 4.000 | 4.027 | 0.027 |

| 4d | 4.584 | 4.569 | − 0.015 | 4.106 | 4.083 | − 0.023 |

| AFATINIB | 4.390 | 4.357 | − 0.033 | 4.390 | 4.370 | − 0.020 |

| AXITINIB | 4.640 | 4.643 | 0.003 | 4.640 | 4.672 | 0.032 |

| DACOMITINIB | 5.160 | 5.137 | − 0.023 | 5.160 | 5.168 | 0.008 |

| Doxorubicin | 5.281 | 5.290 | 0.009 | 5.173 | 5.177 | 0.004 |

| ENTRECTINIB | 5.030 | 5.039 | 0.009 | 5.030 | 4.717 | − 0.313 |

| ERDAFITINIB | 4.180 | 4.174 | − 0.006 | 4.180 | 4.197 | 0.017 |

| GEFITINIB | 4.280 | 4.256 | − 0.024 | 4.280 | 4.269 | − 0.011 |

| OLMUTINIB | 5.100 | 4.761 | − 0.339 | 5.100 | 4.714 | − 0.386 |

| OSIMERTINIB | 4.510 | 4.538 | 0.028 | 4.510 | 4.491 | − 0.019 |

| ROCILETINIB | 4.780 | 4.810 | 0.030 | 4.780 | 4.763 | − 0.018 |

| TUCATINIB | 5.090 | 5.098 | 0.008 | 5.090 | 5.105 | 0.015 |

Table 8.

Statistical parameters of atom-based QSAR model.

| Model | PLS factors | SD | R2 | R2 CV | R2 scramble | Stability | F | P | RMSE | Q2 | Pearson-r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGFR2 | 1 | 0.2626 | 0.5784 | − 0.3838 | 0.6475 | 0.226 | 17.8 | 9.96 × 10–04 | 0.25 | 0.4519 | 0.805 |

| 2 | 0.1454 | 0.8806 | − 0.354 | 0.8538 | − 0.252 | 44.3 | 2.89 × 10–06 | 0.24 | 0.5078 | 0.9345 | |

| 3 | 0.0794 | 0.9674 | − 0.1024 | 0.9274 | − 0.0795 | 108.7 | 1.86 × 10–08 | 0.21 | 0.6324 | 0.8979 | |

| 4 | 0.0585 | 0.9839 | − 0.1924 | 0.969 | − 0.185 | 152.7 | 6.41 × 10–09 | 0.2 | 0.6352 | 0.9086 | |

| FGFR1 | 1 | 0.2727 | 0.5421 | 0.1043 | 0.589 | 0.822 | 15.4 | 1.75 × 10–03 | 0.26 | 0.5515 | 0.9424 |

| 2 | 0.1293 | 0.905 | − 0.2142 | 0.8128 | − 0.0954 | 57.2 | 7.35 × 10–07 | 0.24 | 0.6174 | 0.9542 | |

| 3 | 0.0544 | 0.9846 | − 0.0246 | 0.897 | 0.00916 | 234.1 | 3.04 × 10−10 | 0.2 | 0.7334 | 0.9774 | |

| 4 | 0.0451 | 0.9903 | − 0.097 | 0.9558 | − 0.0759 | 256.5 | 4.98 × 10–10 | 0.2 | 0.7242 | 0.9812 |

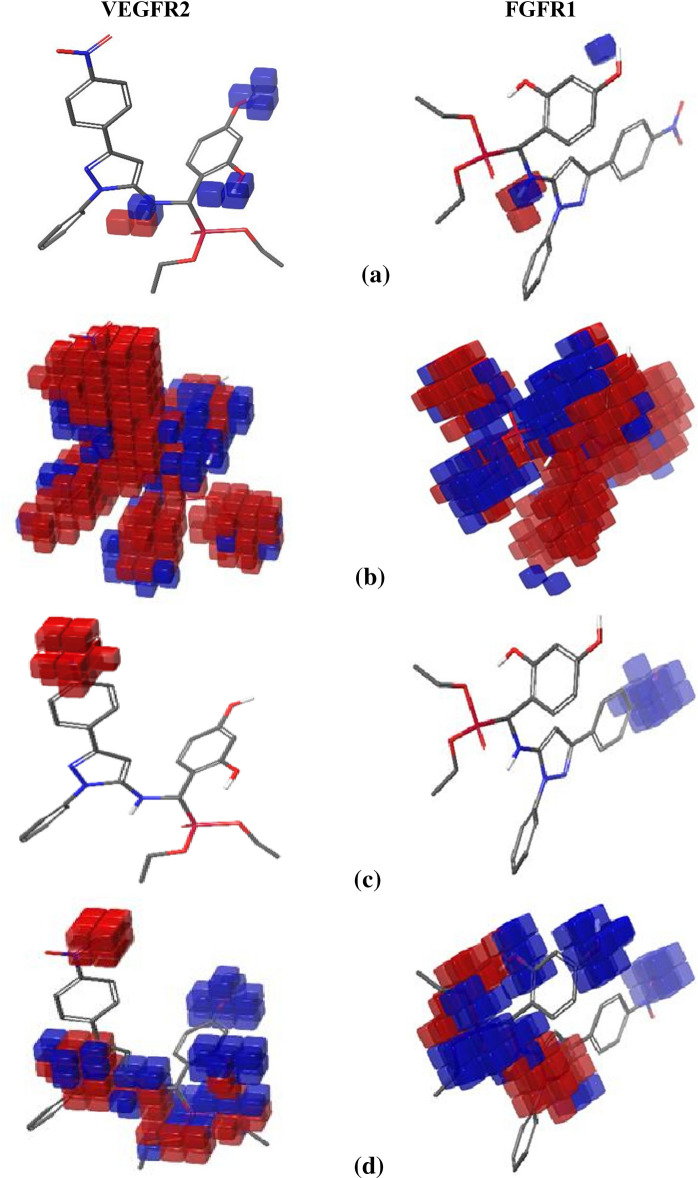

The models have R2, the regression coefficient, ~ 0.5–0.9, while the PLS factor 4 has R2 ~ 0.9, indicating the model's robustness. The cross-correlation coefficient and regression coefficient are close, indicating that the model is stable. The models have a very high F variance and low P values, indicating that they are statistically significant. The cross-correlation coefficient Q2 for the models is 0.635 and 0.724, respectively. This shows that the models are feasible. Figures 14 and 15 show the graphs for the models' training and test sets.

Figure 14.

Experimental vs predicted activity of atom-based QSAR model for VEGFR2 model.

Figure 15.

Experimental vs predicted activity of atom-based QSAR model for VEGFR2 model.

Blue cubes represent favorable locations toward inhibitory action in the models of VEGFR2 and FGFR1 receptors for substances (Fig. 16 and Figs. S42–S58, supplementary materials), whereas red cubes represent unfavorable regions. Compound 2a, for example, demonstrates the hydrogen bond donor action of NH and both phenolic OH groups for the VEGFR2 model but is not very effective for FGFR1 model suppression. The hydrogen bond donor effect of NH is not as good as VEGFR2 inhibition, and the hydrogen bond donor effect of one of the hydroxyl groups for the FGFR1 model is reduced while the impact of the other OH group is vanished.

Figure 16.

QSAR models of compound 2a with VEGFR2 and FGFR1 receptors inhibition for (a) hydrogen bond donor effect, (b) hydrophobic effect, (c) positive ionic effect, and (d) electron withdrawing effect.

The compound’s hydrophobic impact cannot be utilized to differentiate between VEGFR2 and FGFR1 inhibition. The majority of hydrophobic areas behave similarly to both systems.

The electron-drawing effect is likewise insufficient for distinguishing the inhibitory characteristics of VEGFR2 and FGFR1. Also, the electron-withdrawing effect of N(CH3)2 substituent is equally good for inhibiting both models. But the electron-withdrawing effect of (NO2) substituents shows good and poor inhibiting. Finally, the (Cl) substituent doesn’t exhibit any effect.

The positive ionic effect of (NO2) ion made compounds are not favorable for VEGFR2 inhibition. On the other hand, the positive ionic effect of (NO2) toward FGFR1 inhibition is good inhibitor except for the compound 2f and 4d. As a result, the compound’s positive ionic action on both inhibitory systems is very instructive in distinguishing between VEGFR2 and FGFR1 inhibition.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study is based on synthesized and evaluated new series of α-aminophosphonates 2a-f and 4a-d derivatives containing pyrazole moiety by reaction of various aromatic aldehydes with diethyl and/or diphenyl phosphites in presence of LiClO4 as a catalyst under convenient and efficient conditions via the Kabachnik-Fields reaction. The structure of the synthesized compounds was confirmed by elemental analysis, FT-IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and MS spectral data. All of the synthesized compounds were evaluated for their in vitro antitumor activities, against colorectal carcinoma Colon cancer (HCT-116) and Epdermoid carcinoma (HEP2) and also Human lung fibroblast normal cell line (WI38). From the data, we could conclude that all these novel α-aminophosphonates could inhibit tumor cell lines (HCT-116 and HEP2) below 10 µM by the MTT assay. Moreover, Compounds 2a, 4b and 4d exhibited more potent inhibitory activity for Epdermoid Carcinoma (HEP2 with IC50 values (0.9 ± 12.5, 1.40 ± 17.76, and 1.8 ± 21.28 μM), respectively, compared with doxorubicin (0.6 ± 8.54 μM), while the rest compounds have moderate to weak activity against the same cell line. For colon carcinoma cells (HCT-116) Compounds 2a, 2d and 4b gave the strongest activity among all compounds with IC50 values (0.7 ± 9.51, 1.6 ± 19.90, and 1.1 ± 15.06 μM), respectively, compared with doxorubicin (0.3 ± 5.32 μM). Finally, all the studied phosphonate compounds have good to moderate cytotoxicity activity on the normal cell WI-38. The geometry optimization results using DFT exhibits that the stability of 4d is higher than that of other compounds as well as 2f has the highest electron acceptance while dipole moment of 4a is greater than other compounds’ values which may increase hydrophilic nature of 4a. From molecular docking interaction, the results reveals that compounds 2a shows good interactions with VEGFR‐2 and FGFR1 proteins respectively, this behavior may be due to the highest positive and negative surface potentials of 2a obtained from electrostatic potential calculations. On the other hand, compound 4c doesn’t exhibit any interactions with the VEGFR‐2 protein. Also compounds 4c, 2e, 2d, 4b, and 2c don’t show any interactions with the FGFR1 protein. From these data, one can notice that compound 4c has no interaction with FGFR1 protein and agree with experimental data of in vitro cytotoxicity against WI38 with IC50 values (> 100 μM).

Experimental

Materials and instrumentation

All data of chemicals and instruments are available in the supplementary file (Sect. S1). In accordance with literature procedures, the compounds aryl substituted pyrazolamines41 were synthesized.

Chemistry

Synthesis of α-aminophosphonate compounds 2a-e and 4a-d

To a stirred solution of 3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine 1/or 3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-amine 2 (0.01 mol) and appropriate aldehyde derivatives (0.0012 mol) in dry dichloromethane CH2Cl2 (5 ml), triphenyl phosphite and/or triethyl phosphite (0.001 mol) and anhydrous lithium perchlorate LiClO4 (100 mol %) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature (48 h) until the completion of the reaction as indicated by TLC. Then CH2Cl2 was evaporated and the α-amino phosphonates were precipitated using methanol. The precipitate was filtered off affording new α-amino phosphonates in good yield.

Diethyl{(3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ylamino)(2,3-dihydroxyphenyl)}methyphosphonate (2a)

Isolated yield = 85%, Melting point: 277–279 °C, IR: ν/cm–1: 3248 (NH), 3029 (CH-Arom.), 2925 (CH-Aliph), 1254 (P=O), 1086 (P–O–C), 761 (P–CH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 1.32 (m, 6H, 2CH3), 3.65 (m, 4H, 2CH2), 5.07 (s, 1H, CH-P), 6.94 (s, 1H, CH-Pyrazole), 7.14–8.00 (m, 7H, Ar–H), 5.70 (br, 1H, NH, exchangeable with D2O), 9.41, 9.31(2H, OH, exchangeable with D2O). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.23 (2CH3), 52.47 (2CH2), 54.04 (CH-P), 83.24 (CH-Pyrazole), 152.28 (C=N pyrazole), 148.63 (C–NH), 148.47 (C–NO2), 161.43(C–OH), 122.16–148.34 (Ar–C). MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z = 538.73 [M]+. Anal. Calcd. For C26H27N4O7P (538.16) C, 57.99; H, 5.05; N, 10.40. Found; C, 57.91; H, 4.98; N, 10.34.

Diethyl{(3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ylamino)(3-hydroxyphenyl)}methylphosphonate (2b)

Isolated yield = 77%, Melting point: 252–254 °C. IR: ν/cm–1: 3413 (NH), 3025 (CH–Arom.), 2917 (CH–Aliph.), 1265 (P=O); 1006 (P–O–C), 700 (P–CH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 1.23 (m, 6H, 2CH3), 4.25 (m, 4H, 2CH2), 5.29 (s, 1H, CH-P), 6.55 (s, 1H, CH-Pyrazole), 7.14–8.72 (m, 7H, Ar–H), 5.71 (br, 1H, NH, exchangeable with D2O), 9.06 (s, 1H, OH, exchangeable with D2O). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.23 (2CH3), 59.59 (2CH2), 66.81 (CH-P), 81.93 (CH-Pyrazole), 167.94 (C=N pyrazole), 146.24 (C-NH), 145.54 (C–NO2), 117.44–144.20 (Ar–C). MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z = 522.66 [M]+. Anal. Calcd. For C26H27N4O6P (522.17) C, 59.77; H, 5.21; N, 10.72. Found; C, 59.69; H, 5.16; N, 10.65.

Diethyl{(3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ylamino)(3-chlorophenyl)}methylphosphonate (2c)

Isolated yield = 84%, Melting point: 150–152 °C. IR: ν/cm–1: 3435 (NH), 3029 (CH–Arom.), 2982 (CH–Aliph.), 1193 (P=O), 1104 (P–O–C), 758 (P–CH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 1.26 (m, 6H, 2CH3), 3.62 (m, 4H, 2CH2), 5.35 (s, 1H, CH-P), 6.23 (s, 1H, CH-Pyrazole), 6.72–8.52 (m, 7H, Ar–H), 5.61 (br, 1H, NH,exchangeable with D2O). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 22.06 (2CH3), 64.01 (2CH2), 66.82 (CH-P), 85.49 (CH-Pyrazole), 146.42 (C=N pyrazole), 143.77 (C–NH), 139.33 (C-NO2), 119.72–137.88 (Ar–C). MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z = 540.13 [M] +. Anal. Calcd. For C26H26ClN4O5P (540.12) C, 57.73; H, 4.84; N, 10.36. Found; C, 57.67; H, 4.79; N, 10.29.

Diethyl{(3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ylamino)(4-nitrophenyl)}methylphosphonate (2d)

Isolated yield = 75%, Melting point: 234–235 °C. IR: ν/cm-1: 3430 (NH), 3068 (CH–Arom.), 2853 (CH–Aliph.), 1230 (P=O); 1083 (P–O–C), 764 (P–CH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 1.39 (m, 6H, 2CH3), 4.32 (m, 4H, 2CH2), 5.52 (s, 1H, CH-P), 6.81 (s, 1H, CH-Pyrazole), 7.13–8.35 (m, 7H, Ar–H), 5.85 (br, 1H, NH,exchangeable with D2O). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 15.21 (2CH3), 58.29 (2CH2), 59.05 (CH–P), 89.37 (CH–Pyrazole), 148.97 (C = N pyrazole), 144.32 (C–NH), 142.92 (C–NO2), 116.39–135.83 (Ar–C). MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z = 549.12 [M+-2]. Anal. Calcd. For C26H26N5O7P (551.16) C, 56.62; H, 4.75; N, 20.31. Found; C, 56.54; H, 4.69; N, 20.24.

Diethyl{(3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ylamino)(4-chlorophenyl)}methylphosphonate (2e)

Isolated yield = 77%, Melting point: 298–300 °C. IR: ν/cm–1: 3447 (NH), 3162 (CH–Arom.), 2922 (CH–Aliph.), 1239 (P=O), 1069 (P–O–C), 765 (P–CH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 1.31 (m, 6H, 2CH3), 4.39 (m, 4H, 2CH2), 5.49 (s, 1H, CH-P), 6.42 (s, 1H, CH-Pyrazole), 6.72–8.95 (m, 7H, Ar–H), 5.92 (br, 1H, NH, exchangeable with D2O). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 16.97 (2CH3), 41.90 (2CH2), 66.82 (CH-P), 82.89 (CH-Pyrazole), 151.35 (C=N pyrazole), 150.40 (C–NH), 146.87 (C–NO2), 116.97–139.73 (Ar–C). MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z = 540.80 [M] +. Anal. Calcd. For C26H26ClN4O5P (540.13) C, 57.73; H, 4.84; N, 10.36. Found; C, 57.65; H, 4.77; N, 10.29.

Diethyl{(1-(2,4-dinitrophenyl)-3-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ylamino)(4-N,Ndimethylaminophenyl)} methyl phosphonate (2f)

Isolated yield = 82%, Melting point: 244–246 °C. IR: ν/cm–1: 3422 (NH), 3065 (CH–Arom.), 2919 (CH–Aliph.), 1267 (P=O); 1011 (P–O–C), 701(P–CH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 2.61 (s, 6H, 2CH3), 1.41 (m, 6H, 2CH3), 3.93 (m, 4H, 2CH2), 5.31 (s, 1H, CH-P), 6.94 (s, 1H, CH-Pyrazole), 7.14–9.41 (m, 7H, Ar–H), 5.99 (br, 1H, NH, exchangeable with D2O). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 20.61(2CH3), 12.63 (2CH3), 55.16 (2CH2), 64.82 (CH-P), 83.86 (CH-Pyrazole), 161.43 (C = N pyrazole), 152.28 (C–NH), 148.62, 148.47 (2 C–NO2), 119.26–148.34 (Ar–C). MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z = 594.67 [M] +. Anal. Calcd. For C28H31N6O7P (594.20) C, 56.56; H, 5.26; N, 14.13. Found; C, 56.49; H, 5.21; N, 14.07.

Diphenyl{(3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ylamino)(3-hydroxyphenyl)}methylphosphonate (4a)

Isolated yield = 81%, Melting point: 266–268 °C. IR: ν/cm–1: 3432 (NH), 3032 (CH–Arom.), 1234 (P=O), 1015 (P–O–C), 701 (P–CH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 5.34 (s, 1H, CH-P), 6.84 (s, 1H, CH-Pyrazole), 6.32–8.64 (m, 7H, Ar–H), 5.74 (br, 1H, NH,exchangeable with D2O), 6.34 (s, 1H, OH, exchangeable with D2O). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 68.35 (CH–P), 89.37 (CH-Pyrazole), 159.05 (C=N) pyrazole, 158.29 (C–NH), 148.97 (C–NO2), 116.39–135.83 (Ar–C). MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z = 617.04 [M+-1]. found,.Anal. Calcd. For C34H27N4O6P (618.17) C, 66.02; H, 4.40; N, 9.06. Found; C, 65.96; H, 4.32; N, 8.99.

Diphenyl{(3-(4-nitrophenyl)-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ylamino)(4-nitrophenyl)}methylphosphonate (4b)

Isolated yield = 83%, Melting point: 167–168 °C. IR: ν/cm–1: 3432 (NH), 3065 (CH–Arom.), 2925 (CH–Aliph.), 1235 (P=O), 1025 (P–O–C), 765 (P–CH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 5.49 (s, 1H, CH–P), 6.61 (s, 1H, CH–Pyrazole), 6.75–8.45 (m, 7H, Ar–H), 5.94 (br, 1H, NH, exchangeable with D2O). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 64.01 (CH–P), 83.77 (CH–Pyrazole), 146.42 (C=N pyrazole), 143.77 (C–NH), 139.33 (C–NO2), 119.72–137.88 (Ar–C). MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z = 647.25 [M] +. Anal. Calcd. For C34H26N5O7P (647.16) C, 63.06; H, 4.05; N, 10.81. Found; C, 62.98; H, 3.97; N, 10.74.

Diphenyl{(1-(2,4-dinitrophenyl)-3-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ylamino)(3-nitrophenyl)}methyl phosphonate (4c)

Isolated yield = 79%, Melting point: 198–200 °C. IR: ν/cm–1: 3434 (NH), 3063 (CH–Arom.), 2924 (CH–Aliph.), 1237 (P=O), 1064 (P–O–C), 764 (P–CH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 5.29 (s, 1H, CH–P), 7.12 (s, 1H, CH–Pyrazole), 7.31–8.73 (m, 7H, Ar–H), 5.75 (br, 1H, NH, exchangeable with D2O), 6.31 (s, 1H, OH, exchangeable with D2O). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 58.28 (CH-P), 89.39 (CH–Pyrazole), 158.28 (C=N pyrazole), 148.96 (C–NH), 147.26 (C–NO2), 160.41(C–OH), 114.75–140.75 (Ar–C). MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z = 663.91 [M] +. Anal. Calcd. For C34H26N5O8P (663.15) C, 61.54; H, 3.95; N, 10.55. Found; C, 61.49; H, 3.89; N, 10.48.

Diphenyl{(1-(2,4-dinitrophenyl)-3-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-5-ylamino)(4-N,N-dimethylaminophenyl)} methyl phosphonate (4d)

Isolated yield = 80%, Melting point: 212–214 °C. IR: ν/cm–1: 3464 (NH), 3025 (CH–Arom.), 2921 (CH–Aliph.), 1252 (P=O), 1080 (P–O–C), 732 (P–CH). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 2.51 (s, 6H, 2CH3), 5.76 (s, 1H, CH–P), 6.87 (s, 1H, CH–Pyrazole), 7.38–9.26 (m, 7H, Ar–H), 5.92 (br, 1H, NH, exchangeable with D2O). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 20.61 (2CH3), 65.16 (CH–P), 88.98 (CH–Pyrazole), 158.36 (C=N pyrazole), 156.46 (C–NH), 148.27, 146.46 (2 C–NO2), 144.35–143.74 (Ar–C). MS (EI, 70 eV): m/z = 690.81 [M] +. Anal. Calcd. For C36H31N6O7P (690.20) C, 62.61; H, 4.52; N, 12.17. Found; C, 62.55; H, 4.46; N, 12.10.

Antitumor screening

The in vitro antitumor activity of the compounds under study in this research was investigated cell growth using the MTT assay30, 31. The human tumor cell lines that used to evaluate the activity are Human lung fibroblast (WI38), Colorectal carcinoma Colon cancer (HCT-116) and Epdermoid Carcinoma (HEP2). The MTT assay is a standard colorimetric assay that is used to measure cell growth. It is used to determine cytotoxicity of potential medicinal agents and other toxic materials. Detailed procedures for the MTT assay method is presented in the supporting information (Sect. S2).

Molecular modelling

The Jaguar 11.2 software40, 41 in Schrödinger’s suite42 was used to optimise the geometry of investigated compounds. The density functional theory (DFT) was utilised to simulate chemical processes and predict material characteristics using the hybrid density functional technique B3LYP-d343 combination with a 6-31G** basis set for examined substances.

Molecular docking

A molecular modeling technique called molecular docking is often used to examine how receptors and investigated compounds interact in detail44.

Protein preparation

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR‐2) was found to be crucial for cell survival, which regulates endothelial differentiation in human colorectal carcinoma (HCT‐116)45, 46. Furthermore, Fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFR1) amplification is commonly observed in 9–20% of squamous non-small cell lung cancer47, 48. Therefore, the three-dimensional complex structures of HCT-116 (PDB ID: 1YWN) and W-I38 (PDB ID: 5UR1) were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank49, 50 which they are related to the biological targets VEGFR‐2 and FGFR1, respectively. The protein structures were created with the Schrödinger suite’s protein preparation wizard51, 52 which eliminated water molecules (> 5A radius) and small molecules from the structural section, built disulfide connections, and added hydrogens to the PDB structures. Constrained minimization with default parameters was performed on the structure using the optimized potentials for liquid simulations (OPLS-2005) force field. The structures created were used to generate receptor grids for docking.

Preparation of ligands

The standard drug Doxorubicin and the optimized target compounds using a basis set 6-31G** were intended to be used for docking and were organized using the default methodology of the Ligprep software53 in Schrödinger’s suite. The glide program52 in Schrödinger’s suite was used for docking studies. The glide dock XP procedure was used to dock all investigated compounds to the target protein. The G-score value is a letter grade that indicates how well a compound binds to a receptor. The RMSD may also be utilised to compare a binding conformation to a reference binding configuration. The G-score and RMSD values can be identified as potential inhibitors54.

Docking validation

The docking procedure was confirmed by removing and redocking 1-{4-[4-Amino-6-(4-methoxyphenyl)furo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-5-yl]phenyl}-3-[2-fluoro-5-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]urea inhibitor from the VEGFR‐2 receptor (PDB ID: 1YWN) and 3-(2,6-dichloro-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-1-{1-[4-(dimethylamino)but-2-enoyl]piperidin-4-yl}-7-(phenylamino)-3,4-dihydropyrimido[4,5-d]pyrimidin-2(1H)-one (PDB ID: 5UR1) inhibitor from the FGFR1 receptor into the active sites using Schrödinger’s suite software using the same approach including function parameters were unaltered in the process. This was done to ensure that the inhibitor binds to the active site pocket accurately and with less variance than the true co-crystallized complex.

Atom-based QSAR model

Three-dimensional QSAR analysis is a high-dimensional QSAR approach in which the descriptors are three-dimensional55. Schrodinger software’s phase module was used to create atom-based QSAR models for the two sets. The dataset should be extremely well aligned with each other56 to derive a statistically valid 3D QSAR model.

The training set for model creation was chosen at random, with 70% of the molecules in the training set and 30% in the test set for developing models for VEGFR2 and FGFR1 receptors. For regression analysis, the partial least squares regression approach with a PLS factor of four was utilized57 The PLS factor establishes the relationship between the dependent and independent variables. The same collection of training and test set molecules is used for QSAR model creation of VEGFR2 and FGFR1 receptors inhibition. The models’ dependability and utility were validated by utilizing an external collection of 10 active medicinal compounds retrieved from the ChEMBL drug. (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Umm Al-Qura University, for supporting this work by Grant code: 23UQU4280406DSR003.

Author contributions

M.H.B.: conceptualization, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. S.A.I.: conceptualization, investigation, visualization, resources, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, supervision. M.M.A.: Supervision, Resources, Writing—review. S.A.A.: Supervision, Investigation, Writing – review. M.M.E.l.: resources, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, Software. H.A.H.: conceptualization, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing.

Data availability

The cell lines were provided from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) via VACSERA, Cairo, Egypt. The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in: Macromolecule protein structure, can be deposited in the worldwide protein data bank repository, (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1YWN and https://www.rcsb.org/structure/5UR1). The Jaguar 11.2 software in Schrödinger’s suite was used to optimize the geometry of investigated compounds. The density functional theory (DFT) was utilized to simulate chemical processes and predict material characteristics using the hybrid density functional technique B3LYP-d3 combination with a 6-31G** basis set for examined substances. The optimized target compounds using a basis set 6-31G** were intended to be used for docking and were organized using the default methodology of the Ligprep software in Schrödinger’s suite. The glide program in Schrödinger’s suite was used for docking studies.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Seham A. Ibrahim, Email: seham.ibrahim@science.tanta.edu.eg, Email: sehamabdelatif@yahoo.com

Saleh A. Ahmed, Email: saahmed@uqu.edu.sa, Email: saleh_63@hotmail.com

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-40265-8.

References

- 1.Adnan C, Ercan B, Fikret T. 2-methylindole analogs as cholinesterases and glutathione S-transferase inhibitors: Synthesis, biological evaluation, molecular docking, and pharmacokinetic studies. Arab. J. Chem. 2021;14:103449. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adnan C, Ali D, Abdullah D, Ishak B. Amino acid and dicyclohexylurea linked pyrazole analogues: Synthesis, in silico and in vitro studies. ChemistrySelect. 2023;8(6):e202204926. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Warhi T, Elimam DM, Elsayed ZM, Abdel-Aziz MM, Maklad RM, Al-Karmalawy AA, Afarinkia K, Abourehab MA, Abdel-Aziz HA, Eldehna WM. Development of novel isatin thiazolyl-pyrazoline hybrids as promising antimicrobials in MDR pathogens. RSC Adv. 2022;12:31466–31477. doi: 10.1039/d2ra04385h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aljuhani E, Aljohani MM, Alsoliemy A, Shah R, Abumelha HM, Saad FA, Hossan A, Al-Ahmed ZA, Alharbi A, El-Metwaly NM. Synthesis and characterization of Cu (II)-pyrazole complexes for possible anticancer agents; conformational studies as well as compatible in-silico and in-vitro assays. Heliyon. 2021;7:e08485. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azher OA, Hossan A, Pashameah RA, Alsoliemy A, Alharbi A, Habeebullah TM, El-Metwaly NM. Synthesis, anticancer evaluation, and molecular modeling study of new 2-(phenylamino) pyrazolo [1, 5-a] pyrimidine analogues. Arab. J. Chem. 2023;16:104437. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obaid RJ. New benzimidazole derivatives: Design, synthesis, docking, and biological evaluation. Arab. J. Chem. 2023;16:104505. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Warhi T, Elimam DM, Elsayed ZM, Abdel-Aziz MM, Maklad RM, Al-Karmalawy AA, Afarinkia K, Abourehab MAS, Abdel-Aziz HA, Eldehna WM. Development of novel Isatin thiazolyl-pyrazoline hybrids as promising antimicrobials in MDR pathogens. RSC Adv. 2022;12:31466–31477. doi: 10.1039/d2ra04385h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Soliemy AM, Sabour R, Farghaly TA. Pyrazoles and fused pyrimidines: Synthesis, structure elucidation, antitubercular activity and molecular docking study. Med. Chem. 2022;18:181–198. doi: 10.2174/1573406417666210324131951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Sayed R, Khairou KS. Propoxylated fatty thiazole, pyrazole, triazole, and pyrrole derivatives with antimicrobial and surface activity. J. Surf. Deterg. 2015;18:661–673. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masaret GS. A new approach for the synthesis and biological activities of novel thiazolyl-pyrazole derivatives. ChemistrySelect. 2021;6:974–982. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussein EM, Malik MS, Alsantali RI, Asghar BH, Morad M, Ansari MA, Jamal QMS, Alsimaree AA, Abdalla AN, Al-Qarni AS, Jassas RS, Altass HM, Ahmed SA. Bioactive fluorenes. Part IV: Design, synthesis, and a combined in vitro, in silico anticancer and antibacterial evaluation of new fluorene-heterocyclic sulfonamide conjugates. J. Mol. Struct. 2021;1246:131232. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Labriere C, Andersen JH, Albrigtsen M, Hansen JH, Svenson J. Heterocyclic cellular lipid peroxidation inhibitors inspired by the marine antioxidant barettin. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;84:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moussa Z, Kaddoura R, Saadeh HA, Abutaha N, Ahmed SA. Highly bioactive novel aryl-, benzyl-, and piperazine-selenoureas: Synthesis, structural characterization and in vitro biological evaluation. Heliyon. 2022;8(9):e10709. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khalid K, Smaail R, Youssef R, Jamal T, Yahia NM, Faiz A, M’hammed A. Synthesis and pharmacological activities of Pyrazole derivatives: A review. Molecules. 2018;23:134. doi: 10.3390/molecules23010134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.María-Camila R, Jaime P. Recent advances in synthesis and properties of pyrazoles. Chemistry. 2022;4(3):940–968. doi: 10.3390/chemistry4030065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nashwa MS, Marwa GE, Hala MA, Rana AO. Novel anticancer fused pyrazole derivatives as EGFR and VEGFR-2 dual TK inhibitors. Front. Chem. 2020;7:917. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2019.00917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdellah Y, Daria Z, Joanna L, Aleksandra S, Natalia P, Paulina SS, Patrycja O, Joanna H, Martو M, Karolina D, Krzysztof D, Monika L, Delfina P, Jerzy P, Maciej W. Discovery and optimization of novel pyrazole-benzimidazole CPL304110, as a potent and selective inhibitor of fibroblast growth factor receptors FGFR (1–3) Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021;210:112990. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiumeng Z, Qianqian S, Lixin G, Linjiang T, Jia Li, Yi C, Wei Lu. Pyrazolo[4,3-b]pyrimido[4,5-e][1,4]diazepine derivatives as new multi-targeted inhibitors of Aurora A/B and KDR. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;158:428. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khaliullin FA, Klen EE, Pavlov VN, Samorodov AV, Shepilova SO, Makarova NN, Nurlanova SN, Abzalilov TN. Synthesis and biological activity of 5-alkoxy-and 5-amino-substituted 3-bromo-4-nitro-1-(thietan-3-yl)-1H-pyrazoles. Pharm. Chem. J. 2022;56:316–320. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walęcka-Kurczyk A, Walczak K, Kuźnik A, Stecko S, Październiok-Holewa A. The synthesis of α-aminophosphonates via enantioselective organocatalytic reaction of 1-(N-Acylamino) alkylphosphonium salts with dimethyl phosphite. Molecules. 2020;25(2):405. doi: 10.3390/molecules25020405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amer HH, Ali OM, Salama AA, El-gendy MS, Houssin OK. Synthesis of some new 1, 3, 4-oxadiazole derivatives bearing sugars and α-aminophosphonate derived from 4-nitrophenol as anticancer agents. Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2018;8(9):1275–1286. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bilal L, Abdelghani D, Saida M, Abbes B. Synthesis and potential antimicrobial activity of novel α-aminophosphonates derivatives bearing substituted quinoline or quinolone and thiazole moieties. Med. Chem. Res. 2022;31:60–74. doi: 10.1007/s00044-021-02815-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ren ZL, Zhang J, Li HD, Chu MJ, Zhang LS, Yao XK, Xia Y, Lv XH, Cao HQ. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of α-aminophosphonate derivatives containing a pyrazole moiety. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2016;64:1755–1762. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c16-00622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mostafa AI, Moustafa SA, Mohamed SA, Yousry AA, Ahmed R. A new class of anti-proliferative activity and apoptotic inducer with molecular docking studies for a novel of 1,3-dithiolo[4,5-b]quinoxaline derivatives hybrid with a sulfonamide moiety†. RSC Adv. 2023;13:12589. doi: 10.1039/d3ra01635h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sravya G, Balakrishna A, Zyryanov GV, Mohan G, Reddy CS, Bakthavatchala Reddy N. Synthesis of α-aminophosphonates by the Kabachnik-Fields reaction. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2020;196:353–381. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Awad MK, Abdel-Aal MF, Atlam FM, Hekal HA. Molecular docking, molecular modeling, vibrational and biological studies of some new heterocyclic α-aminophosphonates. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019;206:78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2018.07.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ibrahim SA, Fayed EA, Rizk HF, Desouky SE, Ragab A. Hydrazonoyl bromide precursors as DHFR inhibitors for the synthesis of bis-thiazolyl pyrazole derivatives; antimicrobial activities, antibiofilm, and drug combination studies against MRSA. Bioorg. Chem. 2021;116:105339. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibrahim SA, Ragab A, El-Ghamry HA. Coordination compounds of pyrazolone-based ligand: Design, characterization, biological evaluation, antitumor efficiency, and DNA binding evaluation supported by in silico studies. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2022;36:e6508. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reham R, Yousry AA, Sawsan AF, Sadia AH, Nadia AMS, Ahmed R. Evaluation of the anti-proliferative activity of 2-oxo-pyridine and 1′H-spiro-pyridine derivatives as a new class of EGFRWt and VEGFR-2 inhibitors with apoptotic inducers†. RSC Adv. 2023;13:10440. doi: 10.1039/d3ra00887h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ibrahim SA, Salem MM, Abd Elsalam HA, Noser AA. Design, synthesis, in-silico and biological evaluation of novel 2-Amino-1,3,4-thiadiazole based hydrides as B-cell lymphoma-2 inhibitors with potential anticancer effects. J. Mol. Struct. 2022;1268:133673. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adnan C, Fikret T, Ercan B, Manikanta M. Synthesis, characterization, enzyme inhibitory activity, and molecular docking analysis of a new series of thiophene-based heterocyclic compounds. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2021;57(4):598–604. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaabani A, Nazeri MT, Afshari R. 5-Amino-pyrazoles: Potent reagents in organic and medicinal synthesis. Mol. Divers. 2019;23(3):751–807. doi: 10.1007/s11030-018-9902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Özdemir N, Dayan S, Dayan O, Dinçer M, Kalaycioǧlu NÖ. Experimental and molecular modeling investigation of (E)-N-{2-[(2- hydroxybenzylidene)amino]phenyl}benzenesulfonamide. Mol. Phys. 2013;111(6):707–723. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pearson RG. Absolute electronegativity and hardness: Applications to organic chemistry. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54(6):1423–1430. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Padmanabhan J, Parthasarathi R, Subramanian V, Chattaraj PK. Electrophilicity-based charge transfer descriptor. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2007;111(7):1358–1361. doi: 10.1021/jp0649549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abu El-Reash GM, El-Gammal OA, Ghazy SE, Radwan AH. Characterization and biological studies on Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) complexes of carbohydrazones ending by pyridyl ring. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2013;104:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaber M, Fayed TA, El-Gamil MM, Abu El-Reash GM. Structural, thermogravimetric, B3LYP and biological studies on some heterocyclic thiosemicarbazide copper (II) complexes and evaluation of their molecular docking. J. Mol. Struct. 2018;1151:56–72. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bulat FA, Toro-Labbé A, Brinck T, Murray J, Politzer SP. Quantitative analysis of molecular surfaces: Areas, volumes, electrostatic potentials and average local ionization energies. J. Mol. Mod. 2010;16(11):1679–1691. doi: 10.1007/s00894-010-0692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roy K, Kar S, Das RN. A Primer on QSAR/QSPR Modeling. SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science. Springer; 2015. Statistical methods in QSAR/QSPR; pp. 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray JS, Brinck T, Lane P, Paulsen K, Politzer P. Statistically-based interaction indices derived from molecular surface electrostatic potentials: A general interaction properties function (GIPF) J. Mol. Struct. 1994;307:55–64. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shaabani A, Nazeri MT, Afshari R. 5-Amino-pyrazoles: Potent reagents in organic and medicinal synthesis. Mol. Divers. 2019;23(3):751–807. doi: 10.1007/s11030-018-9902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schrödinger Suite 2021-3 . Schrödinger Suite 2021-3, Protein Preparation Wizard. Schrödinger, LLC; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bochevarov AD, Harder E, Hughes TF, Greenwood JR, Braden DA, Philipp DM, Rinaldo D, Halls MD, Zhang J, Friesner RA. Jaguar: A high-performance quantum chemistry software program with strengths in life and materials sciences. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2013;113(18):2110–2142. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Becke AD. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98(7):5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adnan C. In silico studies on stilbenolignan analogues as SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2021;771:138563. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2021.138563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khaled E, Mohamed KI, Fathalla K, Hamada SA, Ibrahim HE. N-substituted-4-phenylphthalazin-1-amine-derived VEGFR-2 inhibitors: Design, synthesis, molecular docking, and anticancer evaluation studies. Arch. Pharm. 2021;354:e2000219. doi: 10.1002/ardp.202000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhong M, Li N, Qiu X, Ye Y, Chen H, Hua J, Yin P, Zhuang G. TIPE regulates VEGFR2 expression and promotes angiogenesis in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020;16(2):272. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.37906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Helsten T, Elkin S, Arthur E, Tomson BN, Carter J, Kurzrock R. The FGFR landscape in cancer: Analysis of 4853 tumors by next-generation sequencing. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2016;22:259–267. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tiseo M, Gelsomino F, Alfieri R, Cavazzoni A, Bozzetti C, De Giorgi AM, Petronini PG, Ardizzoni A. FGFR as potential target in the treatment of squamous non small cell lung cancer. Cancer. Treat. Rev. 2015;41:527e–539. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schrödinger Suite 2021–3, in: Schrödinger Suite 2021–3, Protein Preparation Wizard; Epik, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, (2021); Impact, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, (2021); Prime, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY (2021).

- 51.Becke AD. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98(7):5648–5652. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miyazaki Y. Novel 4-amino-furo[2,3-d]pyrimidines as Tie-2 and VEGFR2 dual inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15(9):2203–2207. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li X. 2-Oxo-3, 4-dihydropyrimido[4, 5-d]pyrimidinyl derivatives as new irreversible pan fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;135:531–543. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schrödinger Suite 2021-3 . Glide. Schrödinger, LLC; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schrödinger Suite 2021-3 . LigPrep. Schrödinger, LLC; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 56.El-Nahass MN, Bakr EA, El-Gamil MM, Ibrahim SA. Synthesis, characterization, and multifunctional applications of novel metal complexes based on thiazolylazo dye. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2022;36(5):e6652. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suvarna S, Vadakkethil LP, Vasanthakumari D, Kanthimathi BM. Comparative QSAR model generation using pyrazole derivatives for screening Janus kinase-1 inhibitors. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2020;95:503–519. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.13667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The cell lines were provided from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) via VACSERA, Cairo, Egypt. The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in: Macromolecule protein structure, can be deposited in the worldwide protein data bank repository, (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1YWN and https://www.rcsb.org/structure/5UR1). The Jaguar 11.2 software in Schrödinger’s suite was used to optimize the geometry of investigated compounds. The density functional theory (DFT) was utilized to simulate chemical processes and predict material characteristics using the hybrid density functional technique B3LYP-d3 combination with a 6-31G** basis set for examined substances. The optimized target compounds using a basis set 6-31G** were intended to be used for docking and were organized using the default methodology of the Ligprep software in Schrödinger’s suite. The glide program in Schrödinger’s suite was used for docking studies.