Abstract

Purpose

To assess the choroidal vascularity index (CVI) in patients affected by Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) compared to patients affected by dominant optic atrophy (DOA) and healthy subjects.

Methods

In this retrospective study, we considered three cohorts: LHON eyes (48), DOA eyes (48) and healthy subjects’ eyes (48). All patients underwent a complete ophthalmologic examination, including best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) acquisition. OCT parameters as subfoveal choroidal thickness (Sub-F ChT), mean choroidal thickness (ChT), total choroidal area (TCA), luminal choroidal area (LCA) were calculated. CVI was obtained as the ratio of LCA and TCA.

Results

Subfoveal ChT in LHON patients did not show statistically significant differences compared to controls, while in DOA a reduction in choroidal thickness was observed (p = 0.344 and p = 0.045, respectively). Mean ChT was reduced in both LHON and DOA subjects, although this difference reached statistical significance only in DOA (p = 0.365 and p = 0.044, respectively). TCA showed no significant differences among the 3 cohorts (p = 0.832). No changes were detected in LCA among the cohorts (p = 0.389), as well as in the stromal choroidal area (SCA, p = 0.279). The CVI showed no differences among groups (p = 0.898): LHON group was characterized by a similar CVI in comparison to controls (p = 0.911) and DOA group (p = 0.818); the DOA group was characterized by a similar CVI in comparison to controls (p = 1.0).

Conclusion

CVI is preserved in DOA and LHON patients, suggesting that even in the chronic phase of the neuropathy the choroidal structure is not irreversibly compromised.

Subject terms: Hereditary eye disease, Eye manifestations

Introduction

Leber optic hereditary neuropathy (LHON) and dominant optic atrophy (DOA) are the most common inherited optic neuropathies that are secondary to mitochondrial impairment [1].

Although LHON is rare (incidence ranges between 1:31,000 and 1:54,000), this disease has a significant impact on vision in affected patients as it eventually leads to a bilateral severe visual loss due to optic atrophy [2]. This disease primarily affects males and many mutations in mtDNA have been associated with this disease, although 11778 G > A/ND4, 3460 G > A/ND1 and 14484 T > C/ND6 mutations are the most frequent [3]. Conversely, dominant mutations in the OPA1 gene determine the DOA phenotype. Bilateral progressive visual loss and optic atrophy, albeit slower and less severe than LHON, are the common features of DOA [4].

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT), beside its wide use in retinal pathology, has been successfully applied to hereditary optic neuropathies. For instance, reduced thicknesses in retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) and ganglion cell layer (GCL) are considered significant biomarkers of disease progression in both LHON and DOA patients [5].

Furthermore, OCT may easily provide a precise and repeatable longitudinal assessment of these structural changes [6]. Besides the structural neural damage, recent studies highlighted the potential role of a vascular damage in LHON and DOA patients. During the pre-symptomatic LHON phase, a swelling in superior and inferior fibre arcades was demonstrated to be associated with a more severe microangiopathy [7]. Moreover, a thickening in choroidal thickness (ChT) during the LHON acute phase was shown to be followed by a reduction of this parameter in the chronic phase [8]. Thus, it may be inferred that the choroid could play a dynamic role in the progression of the neurodegenerative disorder. However, it is still to be assessed if the choroidal changes observed are a clue for the understanding of the disease mechanisms or only a secondary phenomenon.

Importantly, the choroidal thickness appeared as a crucial indicator of eye vascular health: many ocular and systemic diseases were observed to be associated with choroidal modifications [9, 10]. However, the wide disparity in values and the scarce reliability and repeatability in many clinical studies have dampened the potential of ChT as a valuable disease marker [11]. A new technology, enhanced depth imaging (EDI) OCT, has allowed a more precise definition of choroidal vasculature and external boundaries even in presence of a thicker choroid [12, 13]. Furthermore, the application of choroidal vascularity index (CVI) has allowed a more precise characterization and quantification of the two main choroidal components: interstitial stroma and vascular lumen [11]. CVI can be considered as a more reliable vascular parameter and this has been demonstrated in many ocular diseases from glaucoma to retinal disorders [14–16].

Using structural OCT, the aim of this study is to provide a comprehensive assessment of the choroidal tissue in patients affected by LHON and DOA, as compared with an age-matched control group.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study, including patients affected by LHON, DOA and a control group of healthy subjects. Demographic and clinical data of patients presenting between January 2020 and June 2021 at the Neuro-Ophthalmologic Unit of the Department of Ophthalmology of University Vita-Salute San Raffaele in Milan, Italy and Unit of Neurology, Department of Biomedical and NeuroMotor Sciences (DIBINEM), University of Bologna, Italy, were collected. The study was directed in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects and was approved by the Ethics Committee of San Raffaele Institute. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants enrolled. The present study consists of three distinct cohorts: LHON patients, DOA patients and healthy patients (control group).

Inclusion criteria for the LHON and DOA cohorts were: 1) diagnosis of genetic-tested LHON/DOA in a chronic phase of disease, 2) high imaging quality, with a minimum quality index score of 70 (DRI OCT Triton).

Exclusion criteria for all cohorts were: 1) history of any other neuroophthalmological or chorio-retinal disorder, 2) history of any systemic diseases, 3) inadequate fixation or lacking of patient collaboration to acquire high-quality images, 4) myopia greater than 6 dioptres (D) of sphere or 3D of cylinder, and/or axial length > 25.5 mm. An additional exclusion criterium for the LHON cohort was the onset before 12 years of age (childhood-onset LHON).

Both eyes from the same patient were enrolled if they simultaneously fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

All patients underwent an extensive ophthalmologic examination, including best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) using LogMAR charts, and OCT acquisition. All OCT examinations were performed using the enhanced depth imaging (EDI) OCT in order to achieve a good visualization of the choroid. Structural OCT was performed after pupil dilation using swept source (SS) OCT DRI Triton device (Topcon; Tokyo, Japan). A SS-OCT horizontal 9 mm-line passing through the fovea centre intercepting the optic disc was used to perform the further analysis. Furthermore, a 3-dimensional wide scan protocol with a size of 12 × 9 mm consisting of 256 B-scans was employed to obtain RNFL and ganglion cells layer (GCL) thickness measurements. From this scan, the peripapillary RNFL thickness was expressed as 3.4 mm diameter circle including thicknesses measured from 4 quadrants (superior, nasal, inferior and temporal), whereas GCL as a six sectors 6-mm diameter circular annulus centred on the fovea.

Imaging analysis

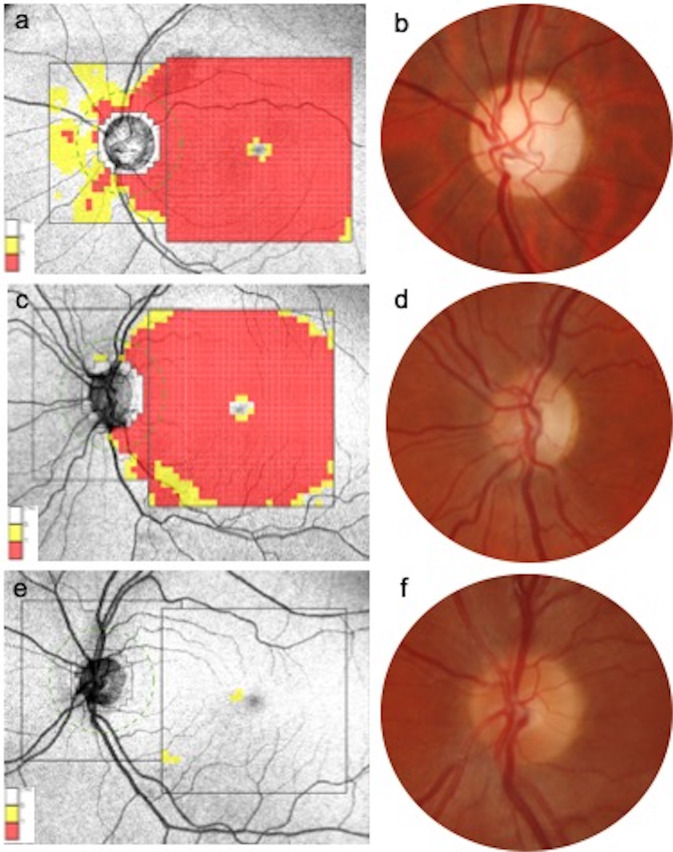

Three parameters, subfoveal choroidal thickness (ChT), mean ChT, and central macular thickness (CMT), were recorded. Two trained examiners (MB and GL) measured the distance from Bruch’s membrane, by means of the Triton calliper, to the sclerochoroidal interface in the subfoveal area (subfoveal ChT) from a single SS-OCT horizontal 9 mm line and the value obtained was used for statistical analyses. In addition, the ChT was calculated 500 μm nasally and temporally to the fovea, and the mean value among the 3 measurements (subfoveal, 500 μm nasally, and 500 μm temporally to the fovea) was used in order to calculate the mean ChT. CMT was identified as the orthogonal distance from the Bruch’s membrane and interface between retina and vitreous in the 1 mm-diameter foveal area. All subjects underwent RNFL and GCL (as the distance from the inner boundary of the GCL to the outer boundary of the inner plexiform layer) thickness measurement. In particular, the peripapillary RNFL thickness was measured using a 360° 3.4 mm diameter circle scan with thicknesses measured across the superior, nasal, inferior and temporal sectors and segmentation analysis of the macula measured across six sectors of the 6 mm diameter circular annulus centred on the foveal included GCL (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell layer thickness diagrams and optic nerve head appearance comparison.

a Severe retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and ganglion cells layer (GCL) thickness reduction in the LE of a patient affected by Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON). b Fundus photograph of the same eye revealing a diffuse pallor of the optic disc and angiopathy. Severe GCC impairment with almost preserved RNFL thickness in a case of dominant optic atrophy (DOA, c). d The optic disc of the same eye demonstrates a temporal pallor. RNFL, GCC thickness and clinical appearance of the optic nerve in a healthy subject, as comparison (e, f).

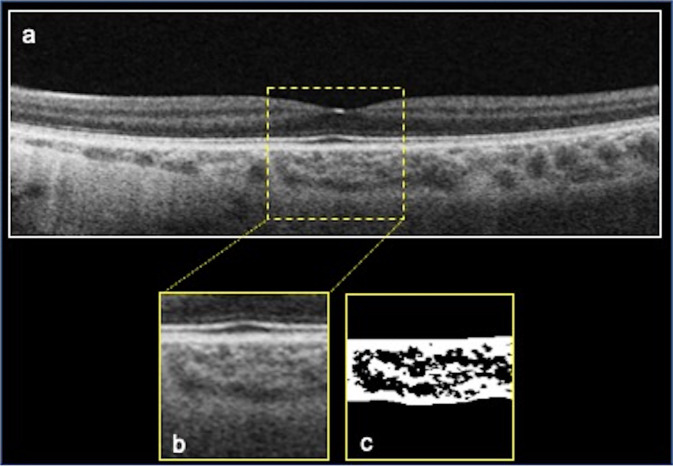

The 9 mm horizontal structural EDI OCT scan was exported by the DRI Triton software and imported into the software FIJI (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) in order to calculate the CVI using a previously reported method [17–19]. This consists in selecting a region of interest (ROI) of 1000 μm wide, centred on the fovea by means of the polygon tool. The upper and lower ROI boundaries consists of the choroidal-RPE junction and the sclerochoroidal junction, respectively. The image could be modified in order to adjust the brightness through the average value obtained from the lumen of three choroidal vessels of the ROI. The Niblack’s autolocal threshold was used to binarize images. The total choroidal area (TCA) was obtained as the total area of the ROI. The luminal choroidal area (LCA) was calculated as the dark pixels of the ROI after binarization. Conversely, the stromal choroidal area (SCA) resulted as the white pixels of the ROI after binarization. CVI was calculated as the ratio between LCA and TCA (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Choroidal vascularity index (CVI) calculation procedure.

a Structural horizontal b-scan OCT in a case of Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) passing through the fovea. A region of interest (ROI) of 1000 µm centered on the fovea was delineated (b) and binarized (c) using Niblack’s auto-local threshold to calculate the CVI. The luminal area is represented by dark pixels, instead the stromal area by the white pixel. CVI was obtained as the ratio between the luminal area and the total choroidal area.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics Version 20 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). All descriptive values analysis was expressed as counts and percentages for categorical variables; quantitative variables were indicated as mean ± SD (standard deviation). The level of agreement between individual measurements of ChT from both readers was performed using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC; 95% CI).

Comparisons of BCVA, CMT, subfoveal ChT, mean ChT, TCA, LCA, SCA, and CVI between the 3 cohorts were performed using the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post-hoc analysis. Pearson’s chi-squared correlation was performed to evaluate the linear correlation between parameters. In all analyses, a p-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Patient demographics and main clinical features

A total of 144 eyes of 72 Caucasian patients, 48 eyes for each group, was included in the study (31 female, 41 male patients). The most common genetic variant found in the LHON cohort was m.11778 G > A/MT-ND4, followed by m.3460 G > A/MT-ND1, m.14484 T > C/MT-ND6 and rare mutations (Supplementary Table 1). The mean age was 36.6 ± 15.4 years (range 14–66 years) for the LHON group, 32.4 ± 19.1 (range 6–66 years) for the DOA group and 36.4 ± 15.0 (range 12–66 years) for the healthy controls and the 3 cohorts of patients did not show statistical differences in terms of age population (p = 0.621) (Table 1). The mean CMT was 219.0 ± 17.4 μm in LHON, 224.0 ± 13.0 μm in DOA and 239.2 ± 16.4 μm in controls (p = 0.993 in LHON vs. DOA, p = 0.002 in LHON vs. controls, and p = 0.004 in DOA vs. controls, respectively) (Table 1). Conversely, BCVA showed significant differences between study populations (p < 0.001). In particular, LHON patients showed the lowest BCVA (1.04 ± 0.02 LogMAR), followed by DOA (0.87 ± 0.04 LogMAR), patients in comparison to control groups (0.09 ± 0.01 LogMAR) (Table 1). Similarly, RNFL and GCL showed dramatic differences between the three cohorts. In particular, lower mean values were observed in the LHON (58.4 ± 32.8 μm (p < 0.0001), 64.8 ± 10.1 μm (p < 0.0001) respectively)) and DOA groups (72.2 ± 31.3 μm (p < 0.0001), 70.0 ± 12.5 μm (p < 0.0001)) compared to the healthy subjects (113.0 ± 35.0 μm; 107.7 ± 5.5 μm). All the demographics and main clinical features of the whole population and of each group were reported in Table 1. No correlation between disease duration, choroidal thickness, RNFL thickness and GCL thickness was found in both LHON and DOA cohorts.

Table 1.

Demographic and OCT characteristics of the study cohorts.

| LHON | DOA | Controls | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients/eyes | 24/48 | 24/48 | 24/48 | |

| M/F (%) | 70.8/29.2 | 50/50 | 50/50 | |

| Mean age (years) ±SD | 36.6 ± 15.4 | 32.4 ± 19.1 | 36.4 ± 15.0 | 0.621 |

| Mean duration of the disease (years) ± SD | 11.0 ± 9.0 | |||

| Best corrected visual acuity (LogMAR) ± SD | 1.04 ± 0.02 | 0.87 ± 0.04 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | < 0.001 |

| Central macular thickness (CMT, μm) ± SD | 219.0 ± 17.4 | 224.0 ± 13.0 | 239.2 ± 16.4 | * |

| RNFL (μm) ± SD | 58.4 ± 32.8 | 72.2 ± 31.3 | 113.0 ± 35.0 | < 0.0001 |

| GCL (μm) ± SD | 64.8 ± 10.1 | 70.0 ± 12.5 | 107.7 ± 5.5 | < 0.0001 |

| Subfoveal choroidal thickness (μm) ± SD | 312.7 ± 114.8 | 279.5 ± 75.9 | 330 ± 70.4 | ** |

| Mean choroidal thickness (μm) ± SD | 313.7 ± 125.0 | 263.3 ± 68.0 | 324.2 ± 64.0 | *** |

LHON Leber hereditary optic atrophy, DOA Dominant optic atrophy, SD Standard deviation, RNFL Retinal nerve fiber layer, GCL Ganglion cells layer.

*p = 0.993 in LHON vs. DOA, p = 0.002 in LHON vs. controls, and p = 0.004 in DOA vs. controls.

**p = 0.344 in LHON vs controls, p = 0.045 DOA vs controls.

***p = 0.365 in LHON vs controls, p = 0.044 DOA vs controls.

Choroidal analysis

Subfoveal ChT and mean ChT demonstrated significantly different values in the analyses (Table 1). A significant reduction in both subfoveal ChT and mean ChT was displayed in both LHON (312.7 ± 114.8 μm (p = 0.344), 313.7 ± 125.0 μm (p = 0.365) respectively) and DOA patients (279.5 ± 75.9 μm (p = 0.045), 263.3 ± 68.0 μm (p = 0.044), respectively) in comparison to the control group. The Interobserver variability between readers was high for all measurements [ICC = (0.923)].

In the analysis of binarized images, TCA, SCA, LCA and the CVI were obtained. In particular, TCA showed no significant differences among the 3 cohorts (p = 0.832). In detail, no changes were detected in LCA among the cohorts (p = 0.389), as well as in the SCA (p = 0.279) (Table 2). In the post-hoc analysis, we did not find differences among groups (p = 0.993 in LHON vs. DOA, p = 0.002 in LHON vs. controls, and p = 0.004 in DOA vs. controls, respectively).

Table 2.

Choroidal features of the three study cohorts.

| LHON | DOA | Controls | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCA, mm2 (mean ± SD) | 0.1439 ± 0.0457 | 0.1486 ± 0.0467 | 0.1456 ± 0.0458 | 0.832* |

| SCA, mm2 (mean ± SD) | 0.0795 ± 0.0228 | 0.0818 ± 0.0191 | 0.0795 ± 0.0314 | 0.279 |

| LCA, mm2 (mean ± SD) | 0.0644 ± 0.0311 | 0.06671 ± 0.0280 | 0.0661 ± 0.0309 | 0.389 |

| CVI | 44.78 ± 7.37 | 44.90 ± 5.47 | 45.39 ± 4.25 | 0.898** |

*In the post-hoc analysis, p = 0.993 in LHON vs. DOA, p = 0.002 in LHON vs. controls, and p = 0.004 in DOA vs. controls.

**Tukey post-hoc analysis, p = 0.911 in LHON vs controls, p = 0.818 LHON vs DOA; p = 1.0 in DOA vs controls.

Interestingly, analysing the ratio between the choroidal LCA and the TCA, the CVI showed no differences among groups (p = 0.898). Using the Tukey post-hoc analysis, we observed that the LHON group was characterized by a similar CVI in comparison to controls (p = 0.911) and DOA group (p = 0.818); the DOA group was characterized by a similar CVI in comparison to controls (p = 1.0). All choroidal features analysed were reported in Table 2.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we provided a comprehensive analysis of the choroid in patients affected by LHON and DOA, as compared with healthy controls. Overall, both LHON and DOA patients are characterized by a significant alteration of the choroid.

CVI is a relatively new OCT parameter that proved to be a reliable tool for the choroidal analysis in healthy and disease eyes [11, 20]. In comparison to the simple choroidal thickness, CVI is not affected by confounding factors as patients’ age, systolic blood pressure and ocular characteristics including intraocular pressure and axial length [21]. Importantly, Agrawal et al demonstrated that CVI metrics are not affected by the OCT device employed to perform the analysis [22]. The field in which CVI was largely employed is the retinal pathology. In particular, the CVI was found significantly reduced in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and was associated with disease outcomes [23, 24]. In diabetic retinopathy, CVI was increasingly impaired in keeping with progression of the disease, with the lowest value in the proliferative form [25]. Similarly, in inflammatory eye diseases, such as tubercular serpiginous choroiditis, CVI was demonstrated to be reduced [26]. However, CVI has also been employed to characterize optic neuropathies. For instance, the CVI was changed in patients with open-angle glaucoma and the peripapillary microvasculature drop-out has been reported to be a potential risk factor in the worsening of the choroidal ischemia in the peripapillary area [14, 27]. Furthermore, in a cross-sectional retrospective comparative analysis, the macular and peripapillary CVI values were demonstrated to be significantly lower in patients affected by arteritic vs. non-arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy [28].

The choroidal involvement in hereditary optic neuropathies has been less characterized in the literature. Borrelli et al. suggested that a significant increase in choroidal thickness may be observed in both the macular and peripapillary regions in the acute phase of LHON, that is known to be also characterized by a “pseudoedema” [8]. This compensatory response may be triggered by a pseudo-hypoxia or a high metabolic demand related to the impaired mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Conversely, in the chronic phase of LHON, the choroid was showed to be thinner, the latter feature eventually to be secondary to a reduced oxygen/energy requirement in the setting of deep neural damage. In agreement with the latter hypothesis, a direct proportion between macular/peripapillary choroidal thickness and retinal fibre layer decrease was observed [29]. Based on these results, several studies have proposed that the pathway exerted by the augmented levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) connected to the mitochondrial impairment is the drive for a reactive choroidal engorgement in the acute phase [30, 31]. As the cell loss continues, the overexpressed biochemical stimulus and the relatively-low energy demand may cause a decrease in the choroidal thickness and retinal perfusion [32, 33].

The choroidal remodelling occurring in the LHON chronic phase, seen as a reduction in the macular choroidal thickness, has been considered as a degenerative feature of the latest stage of the disease, similarly to the angiopathy observed in AMD. However, our data may suggest a different progression. In this study, we confirmed the observation of a substantial reduction in the macular choroidal thickness in LHON patients. Nonetheless, we found values of CVI that were comparable to those found in DOA patients and healthy subjects. These results would suggest that the proportion between the luminal and stromal choroidal areas is still preserved in LHON patients. Therefore, a normal ratio between choroidal stroma and luminal area would exclude a disproportionate involution of the choroidal structure, as opposed to the marked CVI reduction highlighted in other disorders including AMD or diabetic retinopathy. Even though choroidal functionality cannot be inferred by an anatomical parameter as CVI, we speculate that the apparent preservation of the choroidal structure is a prerequisite for the vascular homeostasis and could lead to interesting hypothesis for future strategies.

Indeed, a proper choroidal structure would be of interest for future therapeutic strategies, as gene therapy, in LHON patients in which the neural damage has already started. Specifically, the supposed reversibility of the choroidal remodelling would guarantee an adequate vascular supply to the underneath retinal tissue, in particular photoreceptors, and the integrity of the neural pathway from these cells to the optic disc.

The main limitation of this study is its retrospective nature. Furthermore, the relatively low demographic homogeneity of the LHON and DOA cohort could have affected the results, but the rarity of both the diseases should be considered. Another limitation is that axial length, which could have affected the choroidal thickness, and the peripapillary choroidal thickness were not considered. However, no eyes affected by high myopia were enrolled. Lastly, CVI is only an OCT parameter that could give precious information, only appropriate histologic studies can assess the real status of the choroidal stroma.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that CVI in LHON patients is comparable to DOA and healthy subjects. These results may suggest that the proportion between the choroidal lumen and stroma is preserved in these patients. Our findings may be important for future therapeutic trials in LHON subjects.

Summary

What was known before

In Leber hereditary optic neuropathy, the choroidal thickness undergoes changes from the pseudo-oedema acute phase of choroidal engorgement to the chronic atrophic phase.

What this study adds

Even though a choroidal remodelling happens, the quality of the tissue, assessed through the OCT index choroidal vascularity index (CVI), is preserved in the chronic phase of the disease.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

VC reports consultant and Advisory Board activities with GenSight Biologics, Pretzel Therapeutics, Stealth Biotherapeutics and Chiesi Farmaceutici; honoraria from Chiesi Farmaceutici, First Class and Medscape. None of these activities are related to conduction of this study and the writing of the manuscript. FB is Consultant for Allergan, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Fidia Sooft, Hofmann La Roche, Novartis, NTC Pharma, Sifi, Thrombogenics, Zeiss. None of these activities are related to conduction of this study and the writing of the manuscript. PB reports consultancies for GenSight Biologics and received speaker honoraria from Santhera Pharmaceuticals, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Omikron Italia; he is SI for clinical trials sponsored by GenSight Biologics and Santhera. None of these activities are related to conduction of this study and the writing of the manuscript. All other authors declare no financial disclosures.

Author contributions

MB, MLC, and PB were responsible for the ideation, design and conduction of the study. CB, GL, CV, and AB acquired the data and the measurements for the analysis. EB performed the statistical analysis. LC and VC counselled for the genetic. MB, EB, and PB critically reviewed the results obtained. MB, EB, and PB contributed to the writing of the paper. MLC and VC performed the last revision of the paper.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41433-023-02383-5.

References

- 1.Theodorou-Kanakari A, Karampitianis S, Karageorgou V, Kampourelli E, Kapasakis E, Theodossiadis P, et al. Current and emerging treatment modalities for Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy: A review of the literature. Adv Ther. 2018;35:1510–8. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0776-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu-Wai-Man P, Griffiths PG, Brown DT, Howell N, Turnbull DM, Chinnery PF. The epidemiology of Leber hereditary optic neuropathy in the North East of England. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:333–9. doi: 10.1086/346066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace DC, Singh G, Lott MT, Hodge JA, Schurr TG, Lezza AM, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutation associated with Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. Science. 1988;242:1427–30. doi: 10.1126/science.3201231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu-Wai-Man P, Griffiths PG, Burke A, Sellar PW, Clarke MP, Gnanaraj L, et al. The prevalence and natural history of dominant optic atrophy due to OPA1 mutations. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1538–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moster SJ, Moster ML, Bryan MS, Sergott RC. Retinal ganglion cell and inner plexiform layer loss correlate with visual acuity loss in LHON: A longitudinal, segmentation OCT analysis. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016. 10.1167/iovs.15-17328. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Asanad S, Tian JJ, Frousiakis S, Jiang JP, Kogachi K, Felix CM, et al. Optical coherence tomography of the retinal ganglion cell complex in Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy and dominant optic atrophy. Curr Eye Res. 2019;44:638–44. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2019.1567792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barboni P, Carbonelli M, Savini G, Ramos Cdo V, Carta A, Berezovsky A, et al. Natural history of Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy: Longitudinal analysis of the retinal nerve fiber layer by optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:623–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borrelli E, Triolo G, Cascavilla ML, La Morgia C, Rizzo G, Savini G, et al. Changes in Choroidal Thickness follow the RNFL Changes in Leber’s Hereditary Optic Neuropathy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37332.. doi: 10.1038/srep37332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikuno Y, Tano Y. Retinal and choroidal biometry in highly myopic eyes with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009. 10.1167/iovs.08-3325. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Koizumi H, Yamagishi T, Yamazaki T, Kawasaki R, Kinoshita S. Subfoveal choroidal thickness in typical age-related macular degeneration and polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011. 10.1007/s00417-011-1620-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Agrawal R, Gupta P, Tan KA, Cheung CM, Wong TY, Cheng CY. Choroidal vascularity index as a measure of vascular status of the choroid: Measurements in healthy eyes from a population-based study. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21090.. doi: 10.1038/srep21090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Branchini LA, Adhi M, Regatieri CV, Nandakumar N, Liu JJ, Laver N, et al. Analysis of choroidal morphologic features and vasculature in healthy eyes using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1901–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weill Y, Brosh K, Levi Vineberg T, Arieli Y, Caspi A, Potter MJ, et al. Enhanced depth imaging in swept-source optical coherence tomography: Improving visibility of choroid and sclera, a masked study. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2020;30:1295–1300. doi: 10.1177/1120672119863560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park Y, Cho KJ. Choroidal vascular index in patients with open angle glaucoma and preperimetric glaucoma. PLoS One. 2019. 10.1371/journal.pone.0213336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Velaga SB, Nittala MG, Vupparaboina KK, Jana S, Chhablani J, Haines J, et al. Choroidal vascularity index and choroidal thickness in eyes with reticular pseudodrusen. Retina. 2020;40:612–7. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agrawal R, Chhablani J, Tan KA, Shah S, Sarvaiya C, Banker A. Choroidal vascularity index in central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina. 2016;36:1646–51. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000001040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi F, Liu B, Zhou Y, Yu C, Jiang T. Hippocampal volume and asymmetry in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: Meta-analyses of MRI studies. Hippocampus. 2009;19:1055–64. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sonoda S, Sakamoto T, Yamashita T, Shirasawa M, Uchino E, Terasaki H, et al. Choroidal structure in normal eyes and after photodynamic therapy determined by binarization of optical coherence tomographic images. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55:3893–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berenberg TL, Metelitsina TI, Madow B, Dai Y, Ying GS, Dupont JC, et al. The association between drusen extent and foveolar choroidal blood flow in age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2012;32:25–31. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3182150483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agrawal R, Ding J, Sen P, Rousselot A, Chan A, Nivison-Smith L, et al. Exploring choroidal angioarchitecture in health and disease using choroidal vascularity index. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2020;77:100829.. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2020.100829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao M, Alonso-Caneiro D, Lee R, Cheong AMY, Yu WY, Wong HY, et al. Comparison of choroidal thickness measurements using semiautomated and manual segmentation methods. Optom Vis Sci. 2020;97:121–7. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000001473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agrawal R, Seen S, Vaishnavi S, Vupparaboina KK, Goud A, Rasheed MA, et al. Choroidal vascularity index using swept-source and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography: A comparative study. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retin. 2019;50:e26–e32. doi: 10.3928/23258160-20190129-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giannaccare G, Pellegrini M, Sebastiani S, Bernabei F, Moscardelli F, Iovino C, et al. Choroidal vascularity index quantification in geographic atrophy using binarization of enhanced-depth imaging optical coherence tomographic scans. Retina. 2020;40:960–5. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sacconi R, Battista M, Borrelli E, Senni C, Tombolini B, Grosso D, et al. Choroidal vascularity index is associated with geographic atrophy progression. Retina. 2022;42:381–7. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000003305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim M, Ha MJ, Choi SY, Park YH. Choroidal vascularity index in type-2 diabetes analyzed by swept-source optical coherence tomography. Sci Rep. 2018. 10.1038/s41598-017-18511-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Bansal R, Gupta A, Gupta V, Dogra MR, Sharma A, Bambery P. Tubercular serpiginous-like choroiditis presenting as multifocal serpiginoid choroiditis. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2334–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park JW, Suh MH, Agrawal R, Khandelwal N. Peripapillary choroidal vascularity index in glaucoma—A comparison between spectral-domain OCT and OCT angiography. Investig. Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018. 10.1167/iovs.18-24315. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Pellegrini M, Giannaccare G, Bernabei F, Moscardelli F, Schiavi C, Campos EC. Choroidal vascular changes in arteritic and nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;205:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Darvizeh F, Asanad S, Falavarjani KG, Wu J, Tian JJ, Bandello F, et al. Choroidal thickness and the retinal ganglion cell complex in chronic Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy: A prospective study using swept-source optical coherence tomography. Eye (Lond) 2020;34:1624–30. doi: 10.1038/s41433-019-0695-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carelli V, Ross-Cisneros FN, Sadun AA. Mitochondrial dysfunction as a cause of optic neuropathies. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2004. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Chevrollier A, Guillet V, Loiseau D, Gueguen N, de Crescenzo MA, Verny C, et al. Hereditary optic neuropathies share a common mitochondrial coupling defect. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:794–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.21385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadun A, Carelli V, La Morgia C, Karanjia R. Leber’s Hereditary Optic Neuropathy (LHON) mtDNA mutations cause cell death by overproduction of reactive oxygen species. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015. 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2015.0131.

- 33.Borrelli E, Balasubramanian S, Triolo G, Barboni P, Sadda SR, Sadun AA. Topographic macular microvascular changes and correlation with visual loss in chronic leber hereditary optic neuropathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;192:217–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.