OBJECTIVE: Pregnant individuals are a high-risk group for COVID-19 because of an increased risk for adverse outcomes.1 Vaccines are effective at preventing severe disease.2 However, obstacles to universal vaccine uptake remain.3

There are several factors that could impact vaccine acceptance during pregnancy, including the source of medical information upon which individuals rely. It is unknown whether the use of social media for medical information during pregnancy influences COVID-19 vaccination uptake.

We examined the Assessing the Safety of Pregnancy in the Coronavirus Pandemic (ASPIRE) cohort4 to test the hypothesis that the use of social media for medical information during pregnancy would be associated with a reduced likelihood of COVID-19 vaccination.

STUDY DESIGN: Between April 2020 and December 2021, 7880 pregnant individuals aged ≥18 years at <10 weeks’ gestation consented to an institutional review board–approved prospective cohort study of pregnancy and infant outcomes in relation to pandemic factors, including COVID-19 infection and vaccination (ASPIRE).4 A total of 3018 participants from all 50 US states completed online questionnaires. The research team was based in San Francisco, California. At the end of the third trimester, participants were asked about the sources of medical information used during pregnancy, categorized as healthcare provider, friends and family, social media, and other pregnancy websites. Individuals were asked to indicate all sources and their primary resource.

To evaluate associations between the baseline characteristics and social media use as a source of medical information, bootstrapped (1000 reps) linear regression models and multinomial logistic regression models were used. A logistic regression was used to test for the association between social media use and vaccination with adjustment for other sources of medical information and covariates selected a priori, including age, race, ethnicity, education, household income, recruitment cohort, and healthcare worker status. Statistical analyses were performed in STATA v17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS: The most common sources of medical information were healthcare provider (86%) and pregnancy websites (85%). A total of 52% of participants used social media and 54% reported friends or family as sources. Most participants reported multiple information sources. Of the 3018 participants, 2664 (88%) received COVID-19 vaccines (2121 during pregnancy).

Social media use was more common among Hispanic individuals, individuals who were employed full time, and who did not work in a healthcare field (P<.05) (Table).

Table.

Sociodemographic characteristics by social media use for medical information

| Characteristic or group | No social media use | Social media use | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or n (row %) | Mean (SD) or n (row %) | ||

| Sample | |||

| Community | 1080 (48.2) | 1161 (51.8) | .746 |

| SART | 363 (48.4) | 387 (51.6) | |

| Maternal age (y) | 33.46 (4.29) | 33.10 (4.18) | .068 |

| Gestational age at enrollment (wk) | 7.09 (1.39) | 7.00 (1.43) | .125 |

| Race | |||

| White | 1267 (48.1) | 1366 (51.9) | .978 |

| Black | 36 (53.7) | 31 (46.3) | |

| Asian | 59 (44.4) | 74 (55.6) | |

| Native American | 7 (53.9) | 6 (46.2) | |

| Mixed or other | 48 (45.7) | 57 (54.3) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Not Hispanic | 1294 (48.5) | 1374 (51.5) | .010 |

| Hispanic | 106 (41.1) | 152 (58.9) | |

| Education | |||

| Less than bachelor's degree | 200 (50.8) | 194 (49.2) | .197 |

| Bachelor's degree | 479 (46.6) | 548 (53.4) | |

| Graduate degree | 759 (48.2) | 815 (51.8) | |

| Household income | |||

| <$50,000 | 125 (49.6) | 127 (50.4) | .901 |

| $50,000–$99,000 | 366 (48.7) | 385 (51.3) | |

| $100,000–$250,000 | 750 (48.2) | 807 (51.8) | |

| >$250,000 | 198 (45.5) | 237 (54.5) | |

| Work status | |||

| Unemployed | 60 (50.9) | 58 (49.1) | .034 |

| Full-time homemaker | 169 (51.2) | 161 (48.8) | |

| Part-time employment | 176 (52.5) | 159 (47.5) | |

| Full-time employment | 1033 (46.7) | 1177 (53.3) | |

| Works in healthcare field (patient care) | |||

| No | 1103 (46.0) | 1295 (54.0) | <.001 |

| Yes | 335 (56.3) | 260 (43.7) | |

| Region of residence | |||

| Midwest | 346 (48.4) | 369 (51.6) | .766 |

| Northeast | 259 (46.7) | 296 (53.3) | |

| South | 378 (49.0) | 394 (51.0) | |

| West | 433 (47.5) | 479 (52.5) | |

| Lives in a metropolitan area | |||

| No | 519 (50.3) | 513 (49.7) | .060 |

| Yes | 899 (46.7) | 1025 (53.3) | |

| Dominant SARS-CoV-2 strainb | |||

| Alpha | 340 (46.0) | 399 (54.0) | .389 |

| Delta | 1011 (49.0) | 1054 (51.0) | |

| Omicron | 101 (47.2) | 113 (52.8) | |

| Vaccination timing | |||

| Unvaccinated | 170 (48.0) | 184 (52.0) | .376 |

| Vaccinated >12 wk before pregnancy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Vaccinated within 12 wk of pregnancy | 108 (58.7) | 76 (41.3) | |

| Vaccinated during pregnancy | 1017 (48.0) | 1104 (52.0) | |

| Vaccinated within 12 wk of delivery | 142 (43.6) | 184 (56.4) | |

| Vaccinated >12 wk after delivery | 15 (45.4) | 18 (54.6) |

The results for n=3018 participants are presented.

SART, Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology.

aP value was for the use of social media for medical information, adjusted for use of other websites, provider, or friends and family. Bootstrapped (1000 reps) linear regression was used for continuous characteristics and a multinomial logistic regression was used for categorical characteristics.

bAlpha: before July 2021; Delta: July–November 2021; Omicron: December 2021 or later. Timing based upon completion of health information questionnaire at end of third trimester of pregnancy.

Jaswa. Association between social media use and COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2023.

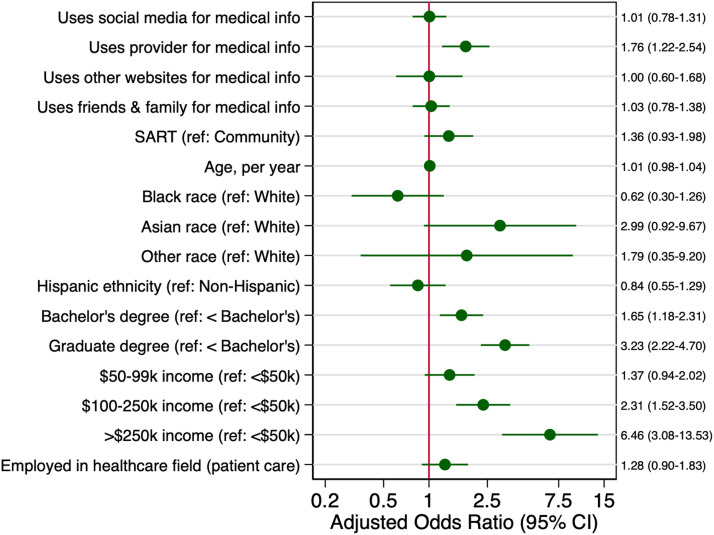

In fully adjusted models, social media use for medical information was not associated with the likelihood of COVID-19 vaccination (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.01; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78–1.31). However, use of healthcare provider was associated with the likelihood of receiving a COVID-19 vaccination (aOR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.22–2.54) (Figure).

Figure.

Adjusted odds ratios (95% CI) of vaccination among study population

Odds ratios are adjusted for other sources of medical information, recruitment cohort (SART vs community), maternal age, race, ethnicity, education, household income, healthcare worker status (yes/no).

CI, confidence interval; SART, Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology

Jaswa. Association between social media use and COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol Glob Rep 2023.

In a sensitivity analysis in which the primary source of medical information was examined, 5% of participants cited social media, 52% cited other websites, 37% cited provider, and 3% cited friends or family. Substituting primary source as the predictor, we again did not observe a relationship between social media use and the odds of receiving a COVID-19 vaccination (aOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.55–1.82; P=.99).

CONCLUSION: Contrary to our hypothesis, the use of social media as a source of medical information during pregnancy was not associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in pregnancy. It is possible that algorithms driving feed content reinforce preconceived healthcare-related attitudes and behaviors (“echo chamber” concept)5 instead of challenge them.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Patient consent was not required because no personal information or details were included.

The Assessing the Safety of Pregnancy in the Coronavirus Pandemic study was funded by the following entities: the Start Small Foundation, California Breast Cancer Research Program (CBCRP), COVID Catalyst Award, Abbvie, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, and individual philanthropists. The funding sources played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.xagr.2023.100262.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.McClymont E, Albert AY, Alton GD, et al. Association of SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy with maternal and perinatal outcomes. JAMA. 2022;327:1983–1991. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.5906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG and SMFM recommend COVID-19 vaccination for pregnant individuals. 2021 [Accessed April 2023]; Available from:https://www.acog.org/news/news-releases/2021/07/acog-smfm-recommend-covid-19-vaccination-for-pregnant-individuals#:~:text=Washington%2C%20D.C.%20%E2%80%93%20The%20American%20College,be%20vaccinated%20against%20COVID%2D19

- 3.Blakeway H, Prasad S, Kalafat E, et al. COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy: coverage and safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.08.007. 236.e1–e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huddleston HG, Jaswa EG, Lindquist KJ, et al. COVID-19 vaccination patterns and attitudes among American pregnant individuals. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2022;4 doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cinelli M, De Francisci Morales G, Galeazzi A, Quattrociocchi W, Starnini M. The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2023301118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.