Abstract

The recent global wave of organic food consumption and the vitality of nutraceuticals for human health benefits has driven the need for applying scientific methods for phytochemical testing. Advanced in vitro models with greater physiological relevance than conventional in vitro models are required to evaluate the potential benefits and toxicity of nutraceuticals. Organ-on-chip (OOC) models have emerged as a promising alternative to traditional in vitro models and animal testing due to their ability to mimic organ pathophysiology. Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of OOC models in identifying pharmaceutically relevant compounds and accurately assessing compound-induced toxicity. This review examines the utility of traditional in vitro nutraceutical testing models and discusses the potential of OOC technology as a preclinical testing tool to examine the biomedical potential of nutraceuticals by reducing the need for animal testing. Exploring the capabilities of OOC models in carrying out plant-based bioactive compounds can significantly contribute to the authentication of nutraceuticals and drug discovery and validate phytochemicals medicinal characteristics. Overall, OOC models can facilitate a more systematic and efficient assessment of nutraceutical compounds while overcoming the limitations of current traditional in vitro models.

1. Introduction

The term nutraceutical is used to describe food or food products that offer health benefits beyond their basic nutritional value. Typically considered functional foods, nutraceuticals contain bioactive compounds that possess potential medicinal properties and are intended to supplement the diet.1 Approximately 80% of the population in developing countries depends on plants for medicinal purposes.2 Many nutraceutical products, i.e., Saw palmetto, Echinacea, and turmeric/curcumin, are derived from plants or herbs and contain natural compounds or phytochemicals that sometimes have been extensively studied for their ability to provide health benefits. These products may include a range of natural substances, including vitamins, minerals, and herbal compounds, which have been shown to improve immunity and the anti-inflammatory effect and protect against chronic diseases and cancers. Nutraceuticals are often sold in the form of capsules, tablets, powders, or beverages and are commonly marketed as dietary supplements. They are generally considered to be safe and nontoxic and usually have been scientifically proven to provide a range of health benefits that can help to treat and prevent disease.3,4 This review aims to examine the various in vitro models for the toxicity and efficacy testing of phytochemicals and the protective and health-promoting effects of specific plant constituents, and the primary objective of this study is to elucidate the implications that arise from the collected data, thereby providing a foundation for future endeavors in the areas of development, discovery, and utilization of phytochemicals as nutraceuticals.4,6 Phytochemicals may provide health benefits as they act as substrates or cofactors in enzymatic reactions, inhibit the enzymatic reactions, enhance the absorption and stability of essential nutrients, prebiotics, or probiotics for beneficial bacteria, or provide selective inhibition for the harmful bacteria.4,5 Research supporting the beneficial role of phytochemicals against cancer, coronary heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, inflammation, and microbial, viral, and parasitic infections is based on the investigations of chemical mechanisms of nutraceuticals using traditional in vitro models. Although such mechanisms of action certainly need to be established in vitro, the efficacy, potency, and safety of these active substances must also be proven in vivo.6 Phytochemicals, such as carotenoids, tannins, polyphenols, and phenols, act as natural radical scavengers and organic sources of antioxidants.2−7 Due to antimicrobial resistance and the toxicity issues of synthetic antimicrobial agents, there is an unmet need to discover novel therapeutic sources to counter infectious diseases.8 The lack of efficacy and the risk of potential side effects of current pharmaceuticals have led researchers to explore advanced chemoprotective solutions that prescribe plant extracts as natural compounds. Many cultivated and wild plant species have been examined for their pharmaceutical potential to inhibit free radicals.9−11 Several studies have successfully led to drug discovery processes from herbal sources and identified a diverse source of phyto-antioxidants.2−6 The plant metabolites responsible for the high antioxidant potential, mainly flavonoids and phenols, can be further characterized by biochemical assays. In recent decades, plants have been used not only for their nutritional value but also for treating many health problems.12

2. Preliminary Analysis for Nutraceuticals

Indigenous inhabitants have reported ethnobotanical applications of various plant species against various diseases, i.e., asthma, diarrhea complication, and acne.55−58 Thousands of scientifically unidentified plant species are an untapped source of natural metabolites which could have high anticancer, antimicrobial, and antiaging potential. Much attention has been paid to extracts of plants and herbs, which, due to their natural source, possess various biochemicals to inhibit cancer cells.9−12 It is generally accepted that the heritage of nutraceuticals is naturally adapted and nourished with precious natural resources, i.e., high altitude, volcanic soil, characteristic temperature, for treating metabolic and infectious diseases, but a preliminary analysis is required to scientifically justify the utility of plant extracts and preparations for the application of potentially active nutraceuticals as demonstrated in Figure 1.13−15 Therefore, finding the preliminary scientific justification to defend their utility as potentially or nutritionally active ingredients is crucial.16 Plant extracts have discrete bioactivities that have biochemical properties by involving the physiological metabolism and their ability to improve homeostasis. For instance, their antioxidant activity can help prevent oxidative stress linked to numerous pathologies, including metabolic dysfunctions, obesity, neurodegeneration, and malignant tumors.21,22

Figure 1.

Scientific justification for the use of potentially active nutraceuticals (A) Nutraceuticals with discrete bioactivities. (B) Classification of biochemical properties of extracts. (C) Extraction of cofactors accelerates enzymatic reactions, enhancing the bioactivity of nutraceuticals. (D) Nutraceuticals can act as inhibitors for specific enzymatic reactions, indicating potential therapeutic applications. (E) Certain nutraceuticals are beneficial in assisting the absorption and stability of essential nutrients. (F) Supernatant separation and transfer after centrifugation allow for the isolation and concentration of desired nutraceutical components. (G) Nutraceuticals can boost the production of selective growth factors. (H) Nutraceuticals aid human metabolism, potentially improving overall health.

Before preparing or isolating plant extracts, biological authentication of the plant should be performed by professional plant taxonomists. Mechanical maceration of the plant is carried out to get the crude extracts for chemical isolation and quantification. The crude extract is usually subject to a qualitative chemical test to detect phytochemicals such as flavonoids, alkaloids, glycosides, saponins, terpenoids (phytosterols), and tannins. After the preliminary phytochemical analysis or screening, the plant extracts are subject to the measurement of various efficacy screening experiments for finding antimicrobial, anticancer, antiaging, antidiabetic, or cosmetic potential. Traditional in vitro models, i.e., cell culture models, transwell model, permeability models, and toxicity screening models, are used for stability, efficacy, potency, toxicity, and safety testing.12,14 As depicted in Figure 2, phytochemical extraction and measurement techniques have been described for the preliminary identification of plant extracts. Various solvent extracts (such as methanolic, butanoic, n-hexane, chloroform, etc.) of selected plants are subjected to the preliminary screening of phytochemicals. While different techniques can be used to assess the functional chemical quantification of the crude extracts for biological activities such as antibacterial activity, anticancer activity, antiparasitic activity, antifungal activity, antiviral activity, and antihemolytic activity, by employing traditional in vitro tests.15 The crude extracts are subject to a qualitative chemical test to detect per reported methods.16 Phytochemical metabolites are rich in their structural and functional diversity and provide several effective bioactive compounds in extracts that are effective against infections and cancer development.21−23 Additionally, nutraceuticals can act as anti-inflammatory agents, which can be particularly beneficial since inflammation is a critical immunological reaction in the body triggered by various factors, e.g., localized or systemic inflammation activated by pathogens, tissue injury, chronic diseases, and autoimmune disorders. Furthermore, the neuroprotective properties of certain nutraceuticals, e.g., omega-3 fatty acids, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), and phycocyanin, particularly those found in algae extracts, have been shown to interact with brain receptors and may have the potential to treat neurological disorders. Lastly, these compounds can have cytotoxic and antitumoral properties by altering DNA binding sites and oxidizing cysteine residues, leading to genomic instability and carcinogenesis.5,12,15−17

Figure 2.

Plant extract preparation and efficacy: (A) Mechanical maceration of the plant is carried out to get the crude extracts; (B) chemical quantification; (C) crude extract is subjected to a qualitative chemical test to detect phytochemicals; (D) after the preliminary phytochemical analysis screening, the plant extract solution is placed at room temperature. Measurement of the efficacy of plant extracts: (E) Plant extracts screening experiment; (F) 2D in vitro models for efficacy and toxicity analysis; (G) cell viability assays; (H) results.

3. In Vitro Models for Nutraceutical Testing

Several bioactivities of nutraceuticals, i.e., antioxidant activity assay, anti-inflammatory activity assay, cytotoxicity assay, immunomodulatory activity assay, analgesic activity assay, and hepatoprotective activity assay, can confirm the ethnomedical significance of plant species. In vitro models are widely used for nutraceutical bioactivity testing due to their cost effectiveness, simplicity, and ethical advantages over animal models. These models include cell-based assays, cell culture-based assays, tissue culture-based assays, and enzyme-based assays. Cell-based assays, i.e., cell viability assay, cell proliferation assay, luciferase activity-based assay, and fluorescence-based assays, may involve using living cells to study the biological effects of nutraceuticals. While tissue culture-based assays, i.e., Boyden chamber assay, 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) assay, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) assay, green fluorescent protein (GFP) assay, immunofluorescence assay, flow cytometry assay, and gene expression assay, utilize human tissue samples, such as liver or intestinal tissue, to evaluate nutraceuticals’ absorption, metabolism, and distribution. Enzyme-based assays measure the activity of specific enzymes involved in metabolic pathways, such as those responsible for antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity.

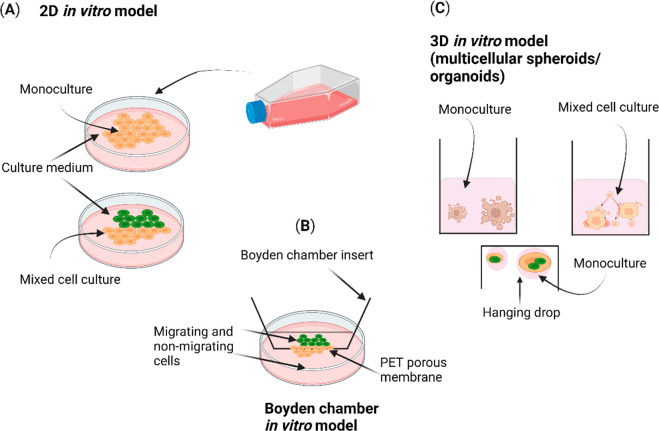

Figure 3 illustrates the different types of in vitro models. Two-dimensional (2D) in vitro models encompass both monoculture and mixed coculture cell models, which are conventional models for toxicity and efficacy testing. The Boyden in vitro model analyzes the migrating cells passing through the polyethylene terephthalate (PET) membrane. Three-dimensional (3D) in vitro models are based on multicellular tissues, spheroids, or organoids. The primary goal of these models is to evaluate the effects of nutraceuticals on various biological processes, such as cell growth, cellular differentiation, cell migration, aging, inflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolism. In this way, these models provide valuable information about the safety, potency, efficacy, toxicity, and mechanisms of action that can be used in nutraceutical-based drug development.31 In the initial primary screening phase of nutraceutical evaluation, preclinical testing is conducted using highly responsive cell lines, e.g., HeLa cells, A549 cells, and SH-SY5Y cells, commonly employed in drug therapy.32,33 If the tested nutraceutical demonstrates growth inhibition, i.e., IC50 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration), EC50 (half-maximal effective concentration), GI50 (growth inhibition 50%), and LD50 (median lethal dose), in at least one cell line, it advances to the subsequent stage, which involves a comprehensive panel of 60 different cell lines.34 In vitro cell culture models play a central role in this process, as they involve the cultivation of isolated cells in a laboratory setting, allowing for exposure to nutraceuticals. These models can be used to evaluate the effects of nutraceuticals on cellular processes and functions. Tissue culture models involve using single or multiple cell types that may be cocultured to create 3D tissue structures that involve multiple cell types that are cultured together to mimic interactions between different tissues or organs.35,36 Such 3D models can be used to evaluate the effects of nutraceuticals on tissue function and communication between different cells.24,25 These traditional in vitro assays or models allow the evaluation of the bioavailability, pharmacokinetics, and biological activity of nutraceuticals. Several factors, i.e., cell type, cell culture technique, and optimal duration of the assay, can influence cell viability assay and cell proliferation assay. Luciferase assay is a reporter gene assay dependent on the promoter driving luciferase expression. Some transcription factors, hormones, cytokines, growth factors, or nutraceutical compounds, may influence the activity of the promoter. Some factors, including autofluorescence, photobleaching, and background fluorescence, can affect fluorescence-based assay and lead to false-positive or false-negative results.19,20 Meanwhile, in vivo or animal models have the property of systematic nutraceutical screening because they determine the drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME), which is assessed in in vivo experiments due to high physiological relevance and complexity and can be used to evaluate the effects of nutraceuticals on communication between other tissues or organs. Despite these qualities, a drawback of in vivo or animal models is their inability to mimic human genetics, and they cannot predict the effect of one extract on other body functions or organs; other flaws are species differences and translation to humans and limited disease models.23

Figure 3.

Different types of in vitro models for nutraceutical testing.

Table 1 specifies the advantages and disadvantages of these in vitro models for nutraceutical efficacy and toxicity screening. As previously mentioned, traditional in vitro and in vivo models have limitations, and advanced models such as the OOC model are potential alternatives to overcome these shortcomings. This phenomenon is partially explained by the fact that cells grown in 2D cultures do not have a complex 3D tissue architecture and lack histological and physiological complexity to clone the complex cellular interactions such as paracrine, autocrine, and endocrine activity, cell–extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions, cell–matrix adhesion, cell polarity, cell migration, cell differentiation, and cell signaling.26Figure 3 shows the different types of in vitro models for nutraceutical testing. 2D and 3D in vitro models use isolated cells or tissues to study the effects of phytochemicals. These models allow for studying specific cellular or molecular mechanisms and may use cell-based assays, biochemical assays, or molecular biology techniques. The 2D in vitro models only partially reflect the pathophysiology of cells because they lack the 3D architecture and microenvironmental cues present in vivo. As a result, researchers have turned to more complex 3D models, such as organoids and spheroids, to mimic the tissue microenvironment and improve the predictiveness of in vitro nutraceuticals-based screening.36 Organoid models involve using differentiated cells representing the tissue-specific cells to create miniaturized versions of human organs. These models can be used to evaluate the effects of nutraceuticals on the phenotype, genotype, and pathophysiology of target organs, e.g., organoids or spheroids consisting of a single type of cell (monoculture), organoids or spheroids consisting of multiple types of cells (mixed cocell culture), and spheroids organoids or created by using the hanging drop method, as shown in Figure 3.22,32,33 The resistance levels of tumors to radiotherapy or chemotherapy can differ between 2D in vitro cultures grown on a flat biocompatible surface and 3D in vitro models. This highlights the significance of employing physiologically relevant in vitro models for nutraceutical testing, as tumors reside within a complex three-dimensional niche in an in vivo system.23 The Boyden chamber is an in vitro cell culture model commonly used in tumor research to assess the effect of nutraceuticals on cell migration and invasion. It consists of two compartments filled with medium and separated by a PET microporous membrane. Cells are seeded in the top compartment and allowed to migrate or invade through the membrane into the bottom compartment in response to a chemoattractant. The Boyden in vitro model is a convenient tool for studying the assessment of cell motility and chemotaxis.27,28 Studies have shown that gene expression profiles and treatment responses in multicellular 3D in vitro models are more like the in vivo microenvironment.29 The utilization of 3D coculture enables the examination of the dynamic behavioral changes exhibited by tumor cells when exposed to nutraceutical drugs. It is achieved by culturing cells using the ECM to 3D model spatial organization, adding various types of cell lines.29,30

Table 1. Advantages and Disadvantages of Different In Vitro Models and Their Comparative Characteristics for Efficacy and Toxicity Screening.

| models | advantages | disadvantages | applications | examples | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D in vitro models | cost-effective drug screening system | lack of physiological and histological features due to the absence of 3D tissue structures and shear stress | drug screening, toxicity studies | monolayer cell cultures, transwell inserts | (34−36) |

| Boyden’s in vitro models | used to study the migration of tumor cells and substance invasiveness | lacks direct intercellular interactions | assessing cell motility, chemotaxis, and invasion studies | transwell migration assays, matrigel invasion assays | (26,37,38) |

| 3D in vitro models (organ-on-chips) | can exhibit intercellular interactions | do not reproduce interactions between ECM and cells; difficult to standardize | tissue engineering, disease modeling, and drug screening | organoids, hydrogels, spheroids | (11,23,39) |

| characteristics of in vitro models | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| features | 2D in vitro models | 3D in vitro models | ref |

| cell morphology | grows on a flat surface and appears flat and stretched | grows into 3D aggregates having the 3D environment and retain the natural shape | (34) |

| cell shape | characterized by monolayer arrangement, where cells form a single layer. | 3D in vitro models exhibit complex cell arrangements, called multilayered, stratified, or three-dimensional structures | (35) |

| intercellular contact | limited interaction | physiological intercellular interaction as in vivo models | (19,26,38) |

| culture medium distribution | an equal amount of medium is received by cells during growth | unequal distribution | (42) |

| gene expression | gene expression profile differs as compared to in vivo models | gene expression profile similar as compared to in vivo models | (39) |

| differentiation of cells | fairly differentiated | accurately differentiated | (23) |

| stimuli response | poor response | good response | (28) |

| cell viability | sensitive to cytotoxin | shows greater viability | |

| drug sensitivity | cells show more sensitivity and high efficacy | drugs show low potency and cells show more resistant | (32) |

| culture duration | allow cells to grow up to 1 week | allow cell to grow up to 4 weeks | (30) |

| cell stiffness | high stiffness | low stiffness | (31) |

Cell culture is an essential element of most traditional in vitro models. Moreover, usually different cell lines can be used for this purpose. Various end point cell viability assays based on colorimetry, i.e., MTT and MTS assays, can be performed to quantify viable cells, which evaluates the mechanism of action of nutraceuticals. It mainly involves the growth of cells in an artificial environment composed of an appropriate surface and nutrient supply.40,41 Usually, cells are grown in in vitro models for days or weeks in a sterile environment. These in vitro models allow the study of the cellular response to potential drugs.42−44 Numerous cell lines have been used in 2D and 3D in vitro models, e.g., human colon carcinoma cell (Caco-2) is commonly used to determine the absorption of drug candidates. Caco-2 cells are used because they form a tight junction in a 2D monolayer in vitro model, miming intestinal epithelium that implies drug transport, making them an explicit model for testing drug absorption.45 Primary human hepatocytes (PHHs) are considered the gold standard for nutraceutical testing in vitro and an excellent model for evaluating drug metabolism.12,26 However, due to PHHs availability and high-cost limitations, several immortalized human hepatocyte cell lines like HepG2, HepaRG, and Huh7 have been extensively used for nutraceutical drug efficacy and toxicity testing as they depict the proper expression of metabolic enzymes.13,27 Each cell line can be selected based on its relevance to the disease or health condition being targeted by the nutraceutical as well as their availability, ease of culture, and reproducibility of results. While 2D models offer valuable preclinical data for drug testing, their ability to accurately predict drug responses in in vivo models sometimes needs to be improved. Therefore, it is crucial to acknowledge the limitations of 2D models when interpreting results and to complement them with other 3D models to validate findings.46,47Table 1 shows the comparative characteristics of different in vitro models for efficacy and toxicity screening. 3D in vitro models receive more attention as they properly carry expression patterns, intracellular pathways, and intracellular junctions, i.e., expression of the target gene proteins, intracellular signaling pathways (PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, MAPK/ERK pathway, tNF-κB pathway), and cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions, which are essential for sustaining tissue integrity and function like in vivo states, compared to 2D in vitro models.19,40,45,48

A 3D in vitro model is developed to recapitulate the histology of culture tissue and the physiological relevance for in vitro experiments. It refers to the culture of living cells inside a chamber or on a biocompatible scaffold to mimic in vivo tissue and for organ-specific microarchitecture.49 3D in vitro models permit better intercellular, paracrine, autocrine, or endocrine signaling and cell-to-cell structural contact that assist in achieving the required cell polarity and allow cells to differentiate and form complex cellular structures.50,51 3D in vitro models have been used in different stages of drug discovery and development, including drug efficacy, drug screening, target identification, biomarker validation, and expression pattern toxicity assessment.52 3D culture models behave similarly to the cells in vivo. They have also been used in the early stages of drug discovery, primarily in cytotoxicity testing such as MTS assay, flow cytometry MTT assay, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay, and trypan blue exclusion assay, which are used to assess the potential toxicity of nutraceutical compounds on cells by measuring changes in cell viability, membrane integrity, and other cellular functions.53 The most effective cell-based assays with 3D in vitro models are cell viability, proliferation, signaling, and the Boyden chamber model (mainly used for assessing cell migration and chemotaxis). It is scientifically proven that cells act differently in 3D in vitro and 2D in vitro models because cells grown in 3D models have more complex cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions, as cells grown in 2D models lack these interactions. In 3D models, cells are exposed to nutrient and oxygen gradients, which can affect the distribution and metabolism of nutraceutical compounds. In 2D models, cells are typically exposed to a uniform distribution, which may not accurately reflect the physiological conditions. The 3D models provide controlled recapitulation of the tissue and organ’s structural and functional aspects; this allows a precise evaluation of the nutraceutical compound’s effects on specific cell types and their interactions with surrounding cells.54 Hence, 3D in vitro models bridge the gap between traditional 2D in vitro models and in vivo animal models. In contrast, microfluidic models involve using microchannels and microchambers designed to mimic the human tissues’ physicochemical and mechanical microenvironments. These microfluidic models can be employed to gauge the effects of nutraceuticals on tissue function under controlled biological conditions, such as shear stress, dynamic environment, and mechanical cues.55−58

4. Organ-on-Chip Model for Nutraceutical Testing

Organ-on-chip (OOC) technology is a cutting edge technology that evolved in the early 2010s and is based on microfluidics and bioengineering for mimicking human organs’ complex physiomechanical cues in the form of dynamic 3D in vitro cell culture models. OOC technology has emerged as a promising tool for various applications in biomedical research, including drug discovery and development, personalized medicine, stem cell engineering, reverse engineering of human organs, toxicology, and disease modeling. OOC models provide an advanced platform to investigate the interactions between nutraceuticals and human tissues, enabling researchers to better understand their mechanisms of action, efficacy, potency, safety, and toxicity profiles. By replicating the microenvironment of specific tissues on miniature chips, OOC technology allows for more accurate and predictive assessments of the effects of nutraceuticals than traditional in vitro models. OOC models typically consist of microfluidic channels or chambers seeded with mammalian cells, creating a physiologically relevant microenvironment which mimics the physiology and responses of the target organ.31,53,59 In contrast, traditional in vitro models for assessing efficacy or toxicity can produce false negative results in a candidate compound due to lack of physiological relevance, missing cellular components, absence of systemic factors, metabolism, and biodistribution differences,43,44 while the OOC model integrated with a real-time monitoring system could provide a robust, noninvasive method for estimating the efficacy of nutraceuticals compared to traditional in vitro models.19,20 It creates miniature versions of human organs that are being used to study the effects of phytochemicals, drug candidates, toxicants, or other substances on specific cells, tissues, or organs in a controlled microenvironment. The phytochemical extracts can be assessed and evaluated according to their potential antimicrobial activities and cytotoxicity assessment, which can revolutionize the field of drug discovery and development. Varying concentrations of the extracts of plants can be perfused through the cell culture media. OOC systems can be used to emulate the dynamic nature of human physiology, including factors such as blood flow, impulse, chemotaxis, tissue–tissue interfaces, and shear stress. This dynamic microenvironment is crucial for studying the ADME mechanism of nutraceuticals as well as their interactions with target cells. Furthermore, OOC systems can be integrated with traditional analytical techniques, such as high-throughput screening systems, automated imaging systems, and molecular analysis, to provide comprehensive insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the effects of nutraceuticals. This can aid in identifying biomarkers, elucidating cellular signaling pathways, and optimizing the formulation and delivery of nutraceuticals.12,13,36,42

The OOC model involves the use of cell culture on ECM-loaded biocompatible membranes, which is subjected to physical and electrical signals through sensors, and microfluidic channels to induce physiological shear stress and simulate the in vivo microenvironment. These physical signals are generated through dynamic flow, microfluidics-based channels, and sensors, i.e., transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) sensors which can be integrated into the OOC model to monitor and control the cellular microenvironment and provide noninvasive results and improved consistency of tissue structures for study of organ-level function for nutraceutical testing and drug discovery.62,63 OOC models can potentially reconstruct and replicate cell migration, microenvironment, and microcirculation. OOC models are microfluidic systems that can reproduce a specific fluid flow, optimum temperature, circulating medium, fluid pressure, and chemical gradients for recapitulating human physiology.64Figure 4 shows the construction of a standard OOC model.

Figure 4.

Organ-on-chip model.

The components of the OOC system may consist of a microfluidic chip comprising monolayer, bilayer, and multilayer configurations.33,39,41 Monolayer chips consist of a single layer of microfluidic channels and are simpler to fabricate, while bilayer and multilayer chips have more complex structures. Bilayer chips have two parallel layers of microfluidic channels separated by a porous membrane (pore sizes range from 0.1 to 10 mm), allowing cell–cell interactions and molecules to transport between the layers. Multilayer chips can have three or more layers, each with different types of cells or tissues, and can mimic complex organ systems. Other components include cell culture media reservoirs, peristaltic pumps, bubble traps, and impedance sensors.57,66,74,88,91 An impedance sensor can be used to monitor cell viability, proliferation, and differentiation as well as drug effects with an electrical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analyzer.65 Three-dimensional structures or scaffolds are essential to provide a support structure for cells to grow and interact; therefore, OOC systems using matrigel matrices, i.e., collagen–matrigel hydrogel matrices, ECM, fibrin, polyethylene glycol (PEG), decellularized extracellular matrix (dECK), and alginate, made OOC systems possible to reproduce the microenvironment conditions for studying the efficacy, safety, potency, and toxicity of nutraceutical drugs.21,88,94,97,101 OOC systems can be constructed containing two microfluidic channels and a porous membrane sandwiched between them. The top channel can be representative of epithelial cells. The bottom channel can act as a vascular equivalent by cultured endothelial cells.66,67 The top channel can be representative of epithelial cells. The bottom channel can act as a vascular equivalent by cultured endothelial cells. In this case, endothelial cells showed in vivo-like behavior under flow conditions. The components include a microfluidic chip that includes monolayer, bilayer, and multilayer chips. Monolayer chips consist of a single layer of microfluidic channels and are simpler to fabricate, while bilayer and multilayer chips have more complex structures. Bilayer chips have two parallel layers of microfluidic channels separated by a porous membrane (pores size range from 0.1 to 10 mm), allowing cell–cell interactions and molecules to transport between the layers. Multilayer chips can have three or more layers, each with different types of cells or tissues, and can mimic complex organ systems. Other components include cell culture media reservoirs, peristaltic pumps, bubble traps, and impedance sensors. An impedance sensor can be used to monitor cell viability, proliferation, and differentiation as well as drug effects with an electrical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analyzer.69−73 The measurements of cellular resistance and electrical cell–substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) in OOC models are emerging as an alternative to conventional biochemical and molecular assays as ECIS is more specific, sensitive, and rapid.18 The applicability of impedance sensing in OOC systems is to measure cell barrier integrity for cell-to-cell tight junction estimation, extracellular matrix (ECM) quantification, and evaluation of the nutraceutical drug toxicity.5,15,16

5. Types of OOC Models for Nutraceutical Testing

The OOC model is a microfluidic system that can reproduce a 3D microenvironment with constant fluid flow and shear stress by depicting precise flow dynamics.102−108,114 The OOC model can be an elegant system to predict the preclinical target efficacy, toxicity, and metabolic conversion rate. Thus, different OOC models can be used to study reliable assessments of the efficacy of plant-based extracts and compounds vs animal-based in vivo studies.115 The kidney OOC model incorporates renal tubular cells, endothelial cells, and vascular components to mimic the kidney’s intricate structure and filtration processes. Nutraceutical compounds can be administered to kidney-on-chip models to assess their impact on renal transport, filtration, and reabsorption. Additionally, these models enable the evaluation of nutraceutical-induced nephrotoxicity, including the assessment of cellular viability, renal biomarkers, i.e., blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), cystatin C, TNF-α, and kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), to evaluate tubular integrity.69−73 The liver-on-chip model includes liver-specific cell types, i.e., primary hepatocytes, hepatic stellate cells, Kupffer cells, and liver vascular endothelial cells, or utilizes induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) differentiated into liver cell types to mimic the metabolic functions of the hepatocytes to assess the metabolism, toxicity, and efficacy of nutraceuticals as well as evaluate their impact on liver-related diseases and drug interactions. The liver-on-chip model evaluates the metabolic activity by measuring drug metabolism enzymes, i.e., cytochrome P450 enzymes, drug transporters, and metabolite production. These biomarker measurements give insights into the biotransformation and pharmacokinetics of nutraceuticals. Various biomarkers of hepatotoxicity can also be assessed, including liver enzyme levels, i.e., alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), oxidative stress markers, i.e., reactive oxygen species (ROS), lipid peroxidation, and cell viability assays, i.e., lactate dehydrogenase release, ATP levels. The liver-on-chip model, also employed to study the impact of inflammatory markers, such as IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-8, can also be measured to evaluate the presence of an inflammatory response induced by nutraceuticals. To study the impact of nutraceuticals on hepatic cells, it is vital to access the metabolism, including drug metabolism, detoxification processes, and metabolic activation of prodrugs.74−81 The brain-on-chip model integrates neuronal cell types, i.e., primary neuronal cultures, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), astrocytes, microglia, pericytes, and endothelial cells, to form the blood–brain barrier to recreate the complex environment of the brain. Nutraceutical compounds can be administered to assess the effects on neuronal activity, neuroinflammation, synaptic function, and neuroprotective mechanisms as well as enable the study of nutraceuticals’ potential in mitigating neurotoxicity on neuronal cells, including assessment of cell viability, neuronal activity, neurotransmitter release, and markers of neuroinflammation. Meanwhile, blood–brain barrier (BBB) function evaluation investigates the impact of nutraceuticals on the integrity and permeability of the BBB using brain OOC models incorporating endothelial cells and neuronal cultures.5,15,16 Bone marrow is a synthetic site for hematopoiesis and immune cell synthesis. The bone marrow-on-chip model aims to recreate the complex hematopoietic stem cell microenvironment comprises of stromal cells and a vascular network from the bone marrow niche. Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), stromal cells, and endothelial cells have been used to mimic the bone marrow-on-chip model. Cell proliferation, differentiation markers, and colony-forming assays can be used to assess the impact of nutraceutical compounds on hematopoietic cell production and differentiation within the model. Biomarkers of bone marrow toxicity, including apoptosis markers (e.g., caspase activity, Annexin V staining), DNA damage markers, i.e., γ-H2AX, and cell viability assays, can be employed to evaluate the potentially toxic effects of nutraceutical compounds on bone marrow cells. For the toxicity analysis of nutraceuticals, certain parameters, i.e., cell viability, proliferation, differentiation, and cytokine production, can be used to determine the impact of nutraceutical compounds on bone marrow function and immune response. While interacting with immune cells, nutraceutical compounds can modulate immune responses. This model can be utilized to investigate the interaction of nutraceuticals with T lymphocyte cells, B lymphocyte cells, and macrophages as well as immune cell activation, cytokine secretion, and antigen presentation to better understand the immunomodulatory effects of nutraceutical compounds.23,32,33,54,58 The gut is responsible for the absorption and metabolism of nutrients, including nutraceutical compounds. The gut-on-chip model enables the evaluation of nutraceutical-induced gastrointestinal toxicity. The parameters cellular viability, barrier integrity, and inflammation markers determine the safety profile of nutraceutical compounds. This includes evaluating the potential for gut epithelial cell damage, disruption of tight junctions, or inflammatory responses. This model can evaluate the enzymatic activity and potential drug–drug interactions within the intestinal epithelial cells to understand nutraceuticals’ metabolic fate and their potential interactions with other coadministered drugs. Gut-on-chip models comprise primary intestinal epithelial cells, i.e., Caco-2 or HT-29 cells, to form the epithelial barrier that lines the gut lumen, microvilli, and peristaltic motions to simulate the physiological functions of the gut. These models evaluate the nutraceutical ADME mechanism by investigating nutraceutical compounds’ absorption, bioavailability, and transport mechanisms across intestinal epithelial cells. Parameters, i.e., TEER, and permeability assays, e.g., paracellular flux assay, transepithelial permeability assay, and fluorescent imaging, can be used to evaluate the integrity of the gut barrier and assess the impact of nutraceuticals on barrier function.82−90 The lung-on-chip model comprises of lung-specific cell types, i.e., primary alveolar epithelial cells, primary bronchial epithelial cells, primary lung fibroblasts, and endothelial cells or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), can be differentiated into different cell types to mimic the physiological structure and barrier function. After exposure to nutraceutical compounds, the lung-on-chip model enables the assessment of parameters such as cell viability, pro-inflammatory cytokine release, oxidative stress markers, and pulmonary barrier integrity. The lung-on-chip model can be employed to study the toxicity testing and the impact of nutraceuticals on lung toxicity, including the evaluation of lung tissue damage, cytotoxicity, and inflammation markers, i.e., tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), IL-6, IL-1β, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3), and C-reactive protein (CRP). Elevated levels of these biomarkers indicate the presence of an inflammatory response.91−95 The heart-on-chip model typically merges the primary cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells to replicate the contractile and vascular properties of the cardiac system. Nutraceutical compounds can be administered to evaluate the effects of cardiac contractility, electrophysiology, and vascular integrity. In terms of toxicity testing, the heart-on-chip model allows the assessment of nutraceutical-induced cardiotoxicity, including the evaluation of cellular viability, cardiac biomarkers, i.e., Troponin T (cTnT), creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), cardiac troponins I and C (cTnI and cTnC), pro-brain natriuretic peptide (proBNP), and contractile dysfunction. The inflammation biomarkers mentioned in the above OOC models can be measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), or immunofluorescence staining depending on the specific requirements of the OOC model. OOC models employ specific approaches with several of them outlined in Table 2.96−101

Table 2. Organ-on-Chip Models Show the Features of Organ-Specific OOC Models.

| organ-on-chip models | cell types | cell number | chip dimensions | chip materials | culture media | media flow | chip coating | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kidney-on-chip | primary human glomerular microvascular endothelial cells, (GMVECs) | 1 × 105 cells per cm2 | 0.1 mm height × 0.1 mm width × 24 mm length | PDMS containing a central porous (7 μm diameter) membrane separating two channels | GMVEC media | 60 μL h–1 | precoated with collagen IV and laminin | (64,65) |

| primary human renal proximal tubule epithelial cells | 1.2 × 105 cells per cm2 | renal basal media (renal proximal tubule) | ||||||

| liver-on-chip | human primary liver sinusoidal microvascular endothelial cells | 1 × 105 cells per cm2 | 0.1 mm height × 0.1 mm width × 24 mm length | porous PDMS membrane (7 μm diameter) membrane | hepatocyte maintenance medium | 60 μL h–1 | precoating with matrigel (and collagen type I) | (40,86−88) |

| human primary hepatocytes | 2.5 × 105 cells per cm2 | |||||||

| brain-on-chip | primary HBMEC | 4 × 107 cells per cm2 | 5 mm width × 20 mm length × 300 μm height | PDMS 10 μm porous membrane 5 μm diameter holes | neuronal maintenance medium (NM1) | 60 μL h–1 | collagen IV and fibronectin | (89) |

| HUVEC | 3 × 106 cells per cm2 | |||||||

| bone marrow-on-chip | HUVECs primary human CD34+ progenitor cells | 1 × 105 cells per cm2 | 0.1 mm height × 0.1 mm width × 24 mm length | PDMS precoated with fibronectin and collagen (7 μm diameter) membrane | StemSpan SFEM II medium | 67 μL min–1 | precoating with matrigel (and collagen type I) | (25,33,90,91) |

| primary osteoblast cells | 1 × 104 cells per cm2 | |||||||

| gut-on-chip | endothelial cells | 1.5 × 105 cells per cm2 | 0.1 mm height × 0.1 mm width × 24 mm length | PDMS (7 μm diameter) membrane | DMEM, EGM-2 | 60 μL h–1 | precoating with matrigel (and collagen type I) | (92) |

| lung-on-chip | primary alveolar epithelial cells, primary human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells | 1 × 105 cells per cm2 | 0.1 mm height × 5 mm 0 width × 10 mm length | PDMS 2-channel microporous | DMEM/F12 | 60 μL h–1 | precoated with collagen IV and laminin | |

| heart-on-chip | primary cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells | 1 × 106 cells per cm2 | 0.1 mm height × 5 mm width × 21 mm length | PDMS 2-channel microporous membrane | DMEM supplement with FBS | 1.3 μL min–1 | collagen IV and fibronectin |

5.1. Features of OOC Models

The OOC model is a state-of-the-art microfluidic model that translates the tissue-specific vital functions of human organs and their mutual interactions.73−81 Pathophysiological aspects of the microfluidic environment in the OOC model can also be validated by monitoring cell-to-cell tight junction proteins and extracellular composition. OOC technology can also be used to explore the effects of plant-based bioactive compounds, which may contribute to drug discovery and validation of plant characteristics.51−62 By using OOC models to study the effects of nutraceutical compounds on human tissues and organs, researchers can gain a better understanding of how they work and potentially identify new drug candidates. This approach may also reduce the need for animal testing in the early stages of drug development. During the initial stages of preclinical drug development, the OOC model can identify and validate specific molecular targets to evaluate the therapeutic effect of nutraceutical compounds. OOC models can be utilized to investigate the interactions between nutraceuticals and relevant cellular targets to study the target engagement, modulation of signaling pathways, and downstream cellular responses. After target identification, nutraceutical compounds undergo efficacy screening and optimization.119−121 OOC-based safety assessment provides insights into the potential adverse effects and helps guide the selection of safe nutraceutical candidates for further development. OOC models can be utilized to study the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties of nutraceuticals. This information aids in predicting the compound’s pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics profiles and optimizing dosing regimens.121−123 Nutraceutical testing using OOC models can be linked to various stages of preclinical drug development for better predictive approach to assess screening, safety, efficacy, target validation, pharmacokinetics, and target interactions; therefore, by leveraging the advantages of OOC models, researchers can enhance the preclinical evaluation of nutraceuticals contributing to the efficient and informed development of nutraceutical interventions.55−69 The integration of OOC platforms in nutraceutical testing can provide valuable insights and complement traditional preclinical in vitro models. Target validation and screening are essential during the early stages of preclinical drug development.70−72 Evaluating the efficacy of nutraceuticals is a crucial step in preclinical drug development. The OOC model can help to assess the compound’s impact on metabolic pathways, detoxification processes, and biomarker expressions. This includes evaluating cellular viability, organ-specific biomarkers, inflammation markers, and barrier integrity. OOC-based safety assessment can help identify potential adverse effects and guide the selection of safer nutraceutical compounds for further development.123 By utilizing OOC platforms, researchers can elucidate the molecular pathways, signaling cascades, and cellular responses involved in the nutraceutical’s mechanism of action. OOC models can facilitate comparative assessments by providing a controlled and standardized platform. This comparative analysis can help make informed decisions regarding the selection and prioritization of nutraceutical candidates for further development.73−79Figure 5 briefs the prerequisite considerations for the development of OOC models including cell types, chip dimension, infrastructure required, ECM, and microenvironment.96−101 OOC models provide an opportunity to perform various toxicity tests specific to each organ system for nutraceuticals, i.e., acute toxicity assessments, chronic toxicity studies, genotoxicity evaluations, and immunotoxicity assays, by incorporating specific cell types and organ functionalities. The OOC platform can also be utilized for diagnostic purposes in nutraceutical research. These applications involve integrating sensing technologies, biomarkers, and imaging modalities to monitor and evaluate organ health and function. For instance, biomarkers associated with organ-specific toxicity or disease conditions can be measured in real time using biosensors integrated into the OOC system. This allows for the early detection of adverse effects or disease-related changes induced by nutraceutical compounds aiding in developing effective interventions.101−107

Figure 5.

Considerations for the development of organ-on-chip models.

When modeling the OOC system, the cell type, microfluidic design carrying the proper nutrient delivery and oxygenation, ECM composition, shear stress, real-time sensor to monitor cell viability, proliferation, metabolic activity, readouts, and validation of results should be considered as shown in Figure 5.108−111 Selecting the appropriate cell line, whether an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) line or a primary cell line, is crucial for replicating the necessary cell–cell interactions to represent human biology accurately. Failure to incorporate specific cell lines for particular organs may lead to false positive results. However, it is essential to prioritize research on cellular interactions and functions that can benefit from achieving proper cell physiology and barrier function. Additionally, when transitioning from a monolayer model to coculture or triculture models, it is crucial to consider the independent effects of cell type stiffness, shear stress, and media composition.112−115 However, it is necessary to increase the physiological relevance through increased complexity. It is also essential to limit the number of dependent variables in a model to obtain more predictive results so that the results can be easily interpreted.103

Commercializing OOC technology for nutraceutical testing involves developing and validating the OOC platforms. This includes engineering the OOC system to accurately replicate the organ’s physiological conditions, establishing reproducibility, and validating its predictive capabilities in comparison to traditional models. Rigorous testing and validation ensure the reliability and credibility of the technology. Protecting and securing the developed OOC technology and intellectual property rights through patents and other appropriate legal mechanisms is essential. Once the OOC technology is established and validated, the manufacturing process needs to be optimized for large-scale production. This involves identifying suitable materials, establishing quality control measures, and optimizing the fabrication processes to ensure consistent and reliable production of OOC devices. Regulatory compliance is crucial to ensure the safe and effective use of OOC technology for nutraceutical testing regulations, i.e., the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States or the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in Europe may classify OOC platforms as medical devices or in vitro diagnostics.115−120

Consequently, compliance with relevant regulations and standards, i.e., Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) and Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP), is necessary to converge the safety and quality requirements. Before commercialization, preclinical testing must be conducted to demonstrate the effectiveness and safety of the OOC platform for nutraceutical testing, which includes conducting comprehensive studies to evaluate the platform’s performance, sensitivity, specificity, and predictive capabilities. Preclinical data generated through these studies form the basis for regulatory submissions and subsequent approvals. In some cases, clinical trials may be required if the OOC technology is intended for clinical use or as a companion diagnostic tool for nutraceuticals.11−16 These trials assess the performance, safety, and efficacy of the OOC platform in human subjects. Regulatory bodies often review clinical trial data to ensure that the OOC technology meets the necessary standards for human use. After completion of preclinical studies and, if applicable, clinical trials, a regulatory submission is prepared for review by the relevant regulatory authorities. The submission includes comprehensive data on the OOC technology’s performance with nutraceuticals safety and efficacy along with supporting documentation such as manufacturing processes, quality control measures, and labeling information. Regulatory approval is granted upon successful review of the submission, allowing for commercialization and use of the OOC technology for nutraceutical testing. Once regulatory approval is obtained, the OOC technology can be introduced to the market for nutraceutical testing. Market entry strategies must involve establishing partnerships with nutraceutical companies, research institutions, or contract research organizations (CROs) to promote the adoption and usage of the OOC platform.121−126

6. Challenges and Success

For centuries, nutraceuticals have been recognized and valued as an abundant source of therapeutic agents. Consequently, traditional treatments have been employed since ancient times to effectively treat and alleviate various diseases.1−6 The rapid growth of the nutraceuticals industry requires the pharmaceutical industry to address emerging scientific challenges and global public concerns about the efficacy and safety of nutraceuticals claimed to promote health.7−9 Herbal medication offers a rational approach for managing chronic conditions that may be difficult to treat using other medical systems. This has sparked a renewed interest in medicinal plants for disease control, leading to their widespread adoption by individuals seeking complementary and alternative medicine options as well as the pharmaceutical industry.2,9 As a result, there is a growing global use of herbal medicine for addressing various health concerns. Nutraceuticals often exert characteristic effects on specific diseases, particularly cancer. Particular attention should be paid to the use of nutraceuticals to treat cancer due to their specific beneficial and anticancer mechanisms.23,32 Although synthetic drugs are the primary source of infection treatment and are effective against pathogens, they have contradictory effects. Some traditional medicines appear to be effective in treating illnesses with little or no side effects, boosting the body’s immunity. Nutraceuticals are a potential source of antivirals, are rich sources of bioactive compounds, and have significant efficacy. In vitro models have successfully identified bioactive compounds in plant-based materials that have potential therapeutic effects on human health.43,51 In vitro models have enabled the development of new products by identifying active compounds that can be used to create innovative formulations and delivery methods that have been successful in the cost-effective screening of large numbers of compounds for possible therapeutic use. 2D and 3D in vitro models have provided mechanistic insights into how nutraceuticals interact with biological systems, which has helped us to understand their potential health benefits.71−74 Conventional 2D and 3D in vitro models have limited predictive ability for determining how nutraceuticals will behave in humans, which can result in false positives and negatives in identifying active compounds; therefore, these models cannot fully replicate human physiology’s complex and dynamic environment, which can limit their ability to predict nutraceuticals’ effects accurately. In vitro models often oversimplify biological systems, which can lead to a failure to capture the true complexity of the interactions between nutraceuticals and human tissues. In vitro models can produce varying results, making it difficult to determine the true therapeutic potential of a nutraceutical.101,104,109 The OOC model can overcome the shortcomings of conventional traditional in vitro models due to its dynamic microphysiological structure. Figure 6 depicts the parameters essential to model an OOC system for nutraceutical testing. Overall, nutraceutical in vitro models have had some successes in identifying active compounds and providing mechanistic insights. Still, they have also faced challenges related to limited predictive ability, lack of physiological relevance, oversimplification, and inconsistent results. However, developing more advanced in vitro models, such as OOC models, may address some of these challenges and lead to more accurate and reliable nutraceutical efficacy and toxicity predictions.91,93 There is a need to standardize phytochemical preparations for their efficacy, safety, and quality. Phytochemicals require isolating active ingredients, biological analysis of plant extracts, and clinical and toxicological studies. Medicinal preparations are made from plant extracts and are considered effective rather than a single component; the standardization process is complex.14,37

Figure 6.

Parameter requirements for nutraceutical OOC models.

Furthermore, activity loss may be possible due to antagonism of the active ingredients with the extract. The survival of any plant-based drug discovery needs proper standardization. It is a significant effort to isolate active compounds from plants with confirmed efficacy activity leading to the study of their mechanism of action. However, claiming that all of these herbs can be prescribed blindly to patients would be unjustified.21−29 Therefore, it is necessary to establish pharmacological authentication of herbal materials for human consumption and validate all evaluation parameters, such as herb–drug and herb–herb interaction and toxic effects, by toxicity and efficacy testing through OOC models. Research on plant bioactive compound validation through OOC models can contribute significantly to validating plant characteristics. Due to the side effects of synthetic medicine, the world has turned to nutraceuticals to treat infections, which are less likely to cause toxicity and resistance, are relatively more accessible, and are less expensive.11−19

7. Future Recommendations

The future of nutraceuticals testing through OOC models offers exciting opportunities for the pharmaceutical industry to validate and explore the myths behind the nutraceuticals and progress the process of drug discovery and drug development. There is a growing demand among consumers for natural and plant-based products, including nutraceuticals, as they become more health conscious and interested in sustainable, organic, and ethically sourced products. Systematic research should be conducted on these compounds and their scientifically validated health benefits to fully understand the mechanisms of action and safety. The development of novel plant-based extraction and processing techniques creates exciting opportunities for utilizing plant-based ingredients in nutraceutical products, leading to new possibilities and formulations. Governments worldwide increasingly recognize the importance of natural and plant-based products in promoting health, food safety, and wellness. Advances in personalized medicine will likely drive the development of plant-based nutraceuticals tailored to specific health conditions and individual needs. As demand for natural and sustainable products continues to grow and scientific research validates the health benefits of plant-based compounds, the market for plant-based nutraceuticals is likely to expand. The pharmaceutical industry still needs to convince the international drug regulatory agencies of the standardization of phytochemicals to the value of nutraceuticals. Novel nutraceuticals can evolve into a vital aspect of drug discovery for disease prevention. Ongoing research is mainly focused on chemical drugs, but it alters various phytonutrients’ role in preventing anticancer and antiviral diseases. The renewed interest in these compounds will provide much needed insight into structure–function relationships. The individual models reviewed above show us an assessment of the current situation and prove that traditional in vitro efficacy techniques should be moved on to OOC models to yield organ-specific toxicity and efficacy results. The research-intensive process should be moved. Moreover, developing advanced OOC tools to isolate and identify the bioactive components of plant extracts is fundamental to obtaining this information. One challenge remains: to educate the public to make wise choices in nutraceutical compound consumption. Other aspects that determine the role of phytochemicals in evaluating the toxicity, efficacy, and contradictory effects and functionality of plant extracts will also need to market nutraceuticals-based drugs to capture consumer interest.

8. Conclusion

The growing popularity of nutraceuticals can be attributed to their numerous advantages, including cost effectiveness, widespread acceptance among the general population, and reduced side effects. Utilizing OOC models for investigating novel nutraceuticals holds substantial promise in advancing drug discovery and development. In contrast to traditional 2D in vitro models that lack physiological fluid flow dynamics, OOC models provide a revolutionary approach to nutraceutical testing. While effective in controlling infections, synthetic drugs often have severe contradictory complications. Therefore, it is crucial to validate natural drugs by establishing the parameters using OOC models to predict nutraceuticals’ efficacy and toxicity accurately. OOC models offer a more reliable representation of how nutraceuticals interact with human tissues and organs compared to traditional in vitro models. By closely replicating the structure and function of human organs, OOC models surpass their counterparts in terms of accuracy. Additionally, OOC models can reduce reliance on animal testing during preclinical drug development. Exploring plant-based bioactive compounds using OOC models significantly contributes to validating their characteristics. OOC models are highly suitable for high-throughput screening numerous nutraceuticals, enabling efficient identification of promising candidates. Moreover, these models can be customized for personalized medicine by utilizing patient-specific cells, allowing predictions on how nutraceuticals will interact with specific tissues and organs.

In conclusion, ongoing exploration, development, and commercialization of OOC toxicity and efficacy models in nutraceutical testing are essential for advancing the field and achieving reliable outcomes for drug discovery. By harnessing the potential of OOC technology, we can improve the understanding and application of nutraceuticals, ultimately benefiting individuals seeking effective and safe therapeutic options. Integrating OOC models enhances the accuracy and predictability of nutraceuticals, bringing us closer to developing effective and safe treatments for various diseases.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Zoio P.; Lopes-Ventura S.; Oliva A. Barrier-on-a-chip with a modular architecture and integrated sensors for real-time measurement of biological barrier function. Micromachines (Basel) 2021, 12, 816. 10.3390/mi12070816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Fajardo R. A.; González-Pech P. G.; Torres-Acosta J. F. de J.; Sandoval-Castro C. A. Nutraceutical potential of the low deciduous forest to improve small ruminant nutrition and health: A systematic review. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1403. 10.3390/agronomy11071403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tihauan B.-M.; Axinie (Bucos) M.; Marinas I.-C.; Avram I.; Nicoara A.-C.; Gradisteanu-Pircalabioru G.; Dolete G.; Ivanof A.-M.; Onisei T.; Casarica A.; Pirvu L. Evaluation of the putative duplicity effect of novel nutraceuticals using physico-chemical and biological in vitro models. Foods 2022, 11 (11), 1636. 10.3390/foods11111636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting Y.; Zhao Q.; Xia C.; Huang Q. Using in vitro and in vivo models to evaluate the oral bioavailability of nutraceuticals. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 1332–1338. 10.1021/jf5047464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi G. R.; Vasconcelos A. B. S.; Wu D.-T.; Li H.-B.; Antony P. J.; Li H.; Geng F.; Gurgel R. Q.; Narain N.; Gan R.-Y. Citrus flavonoids as promising phytochemicals targeting diabetes and related complications: A systematic review of in vitro and in vivo studies. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2907. 10.3390/nu12102907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtunik-Kulesza K.; Oniszczuk A.; Oniszczuk T.; Combrzynski M.; Nowakowska D.; Matwijczuk A. Influence of in vitro digestion on composition, bioaccessibility and antioxidant activity of food polyphenols—a non-systematic review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1401. 10.3390/nu12051401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandeweerd J. M.; et al. Systematic Review of Efficacy of Nutraceuticals to Alleviate Clinical Signs of Osteoarthritis. J. Vet Intern Med. 2012, 26, 448–456. 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2012.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameye L. G.; Chee W. S. S. Osteoarthritis and nutrition. From nutraceuticals to functional foods: A systematic review of the scientific evidence. Arthritis Res. Ther 2006, 8, R127. 10.1186/ar2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refet-Mollof E.; Najyb O.; Chermat R.; Glory A.; Lafontaine J.; Wong P.; Gervais T. Hypoxic jumbo spheroids on-A-chip (HOnAChip): Insights into treatment efficacy. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 4046. 10.3390/cancers13164046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam H.; Funamoto K.; Jeon J. S. Cancer cell migration and cancer drug screening in oxygen tension gradient chip. Biomicrofluidics 2020, 14, 044107. 10.1063/5.0011216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrabpour A. H.; Long M. Behaviour of intermediate stiffness culverts with recycled concrete aggregate backfill. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology 2021, 115, 104061. 10.1016/j.tust.2021.104061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akram M.; et al. Antiviral potential of medicinal plants against HIV, HSV, influenza, hepatitis, and coxsackievirus: A systematic review. Phytotherapy Research 2018, 32, 811–822. 10.1002/ptr.6024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanira M. O. M.; Ali B. H.; Bashir A. K.; Wasfi I. A.; Chandranath I. Evaluation of the relaxant activity of some United Arab Emirates plants on intestinal smooth muscle. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011, 48, 545–550. 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1996.tb05971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqi M. A.; Ahsan A.; Yousuf S.; Shakoor N.; Farooqi H. M. U. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis E Virus Antibodies (IgG) in the Community of Rawalpindi. Livers 2022, 2, 108–115. 10.3390/livers2030009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dillard C. J; German J B. Phytochemicals: Nutraceuticals and human health. J. Sci. Food Agric 2000, 80, 1744–1756. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kausar F.; Farooqi M.-A.; Farooqi H.-M.-U.; Salih A.-R.-C.; Khalil A.-A.-K.; Kang C.-w.; Mahmoud M. H.; Batiha G.-E.-S.; Choi K.-h.; Mumtaz A.-S. Phytochemical investigation, antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticancer activities of acer cappadocicum gled. Life 2021, 11, 656. 10.3390/life11070656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espín J. C.; García-Conesa M. T.; Tomás-Barberán F. A. Nutraceuticals: Facts and fiction. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 2986–3008. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaeva K. v.; Rutland C. S.; Rizvanov A. A.; Solovyeva V. v. Cell Culture Based in vitro Test Systems for Anticancer Drug Screening. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 1–9. 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moya M. L.; Hsu Y.-H.; Lee A. P.; Hughes C. C.W.; George S. C. In vitro perfused human capillary networks. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2013, 19, 730–737. 10.1089/ten.tec.2012.0430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobrino A.; Phan D. T. T.; Datta R.; Wang X.; Hachey S. J.; Romero-Lopez M.; Gratton E.; Lee A. P.; George S. C.; Hughes C. C. W. 3D microtumors in vitro supported by perfused vascular networks. Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 1–11. 10.1038/srep31589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajal C.; Ibrahim L.; Serrano J. C.; Offeddu G. S.; Kamm R. D. The effects of luminal and trans-endothelial fluid flows on the extravasation and tissue invasion of tumor cells in a 3D in vitro microvascular platform. Biomaterials 2021, 265, 120470. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolic M.; Sustersic T.; Filipovic N. In vitro models and on-chip systems: Biomaterial interaction studies with tissues generated using lung epithelial and liver metabolic cell lines. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018, 6, 1–13. 10.3389/fbioe.2018.00120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadde M.; Phillips C.; Ghousifam N.; Sorace A. G.; Wong E.; Krishnamurthy S.; Syed A.; Rahal O.; Yankeelov T. E.; Woodward W. A.; Rylander M. N. In vitro vascularized tumor platform for modeling tumor-vasculature interactions of inflammatory breast cancer. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2020, 117, 3572. 10.1002/bit.27487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmins N.; Dietmair S.; Nielsen L. Hanging-drop multicellular spheroids as a model of tumour angiogenesis. Angiogenesis 2004, 7, 97–103. 10.1007/s10456-004-8911-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia C.; Grayson W. L.; Park M.; Hutton D.; Zhou B.; Guo X. E.; Niklason L.; Sousa R. A.; Reis R. L.; Vunjak-Novakovic G. In vitro model of vascularized bone: Synergizing vascular development and osteogenesis. PLoS One 2011, 6, e28352. 10.1371/journal.pone.0028352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.; Kim W.; Lim S.; Jeon J. S. Vasculature-on-a-chip for in vitro disease models. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 8. 10.3390/bioengineering4010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledvina V.; Klepárník K.; Legartová S.; Bártová E. A device for investigation of natural cell mobility and deformability. Electrophoresis 2020, 41, 1238–1244. 10.1002/elps.201900357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing B.; et al. Establishment and application of a dynamic tumor-vessel microsystem for studying different stages of tumor metastasis and evaluating anti-tumor drugs. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 17137–17147. 10.1039/C9RA02069A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y.; Wan Y.; Hao S.; Nisic M.; Harouaka R. A.; Chen Y.; Zou X.; Zheng S.-Y. Nucleus of Circulating Tumor Cell Determines Its Translocation Through Biomimetic Microconstrictions and Its Physical Enrichment by Microfiltration. Small 2018, 14, 1802899. 10.1002/smll.201802899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahai E.; et al. A framework for advancing our understanding of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 174–186. 10.1038/s41568-019-0238-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y. H. V.; Middleton K.; You L.; Sun Y. A review of microfluidic approaches for investigating cancer extravasation during metastasis. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2018, 4, 1–13. 10.1038/micronano.2017.104.31057891 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilardi M.; et al. The driving role of the Cdk5/Tln1/FAKS732 axis in cancer cell extravasation dissected by human vascularized microfluidic models. Biomaterials 2021, 276, 120975. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh D.; Leslie D. C.; Matthews B. D.; Fraser J. P.; Jurek S.; Hamilton G. A.; Thorneloe K. S.; McAlexander M. A.; Ingber D. E. A human disease model of drug toxicity-induced pulmonary edema in a lung-on-a-chip microdevice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 159ra147. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saji Joseph J.; Tebogo Malindisa S.; Ntwasa M. Two-Dimensional (2D) and Three-Dimensional (3D) Cell Culturing in Drug Discovery. Cell Culture 2019, 10.5772/intechopen.81552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Ding Y.; Sun X. S.; Nguyen T. A. Peptide Hydrogelation and Cell Encapsulation for 3D Culture of MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells. PLoS One 2013, 8, e59482. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kausar F.; Kim K.-H.; Farooqi H. M. U.; Farooqi M. A.; Kaleem M.; Waqar R.; Khalil A. A. K.; Khuda F.; Abdul Rahim C. S.; Hyun K.; Choi K.-H.; Mumtaz A. S. Evaluation of antimicrobial and anticancer activities of selected medicinal plants of Himalayas, Pakistan. Plants 2022, 11, 48. 10.3390/plants11010048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen D. H. T.; et al. Biomimetic model to reconstitute angiogenic sprouting morphogenesis in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 6712–6717. 10.1073/pnas.1221526110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollert I.; Seiffert M.; Bachmair J.; Sander M.; Eder A.; Conradi L.; Vogelsang A.; Schulze T.; Uebeler J.; Holnthoner W.; Redl H.; Reichenspurner H.; Hansen A.; Eschenhagen T. In vitro perfusion of engineered heart tissue through endothelialized channels. Tissue Eng. Part A 2013, 20, 854–863. 10.1089/ten.TEA.2013.0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak T. J.; Lee E. In vitro modeling of solid tumor interactions with perfused blood vessels. Sci. Rep 2020, 10, 1–9. 10.1038/s41598-020-77180-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salih A. R. C.; Farooqi H. M. U.; Kim Y. S.; Lee S. H.; Choi K. H. Impact of serum concentration in cell culture media on tight junction proteins within a multiorgan microphysiological system. Microelectron. Eng. 2020, 232, 111405. 10.1016/j.mee.2020.111405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqi H. M. U.; Kang B.; Khalid M. A. U.; Salih A. R. C.; Hyun K.; Park S. H.; Huh D.; Choi K. H. Real-time monitoring of liver fibrosis through embedded sensors in a microphysiological system. Nano Convergence 2021, 8, 3. 10.1186/s40580-021-00253-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqi H. M. U.; Sammantasinghar A.; Kausar F.; Farooqi M. A.; Chethikkattuveli Salih A. R.; Hyun K.; Lim J.-H.; Khalil A. A. K.; Mumtaz A. S.; Choi K. H. Study of the Anticancer Potential of Plant Extracts Using Liver Tumor Microphysiological System. Life 2022, 12, 135. 10.3390/life12020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chethikkattuveli Salih A. R.; Hyun K.; Asif A.; Soomro A. M.; Farooqi H. M. U.; Kim Y. S.; Kim K. H.; Lee J. W.; Huh D.; Choi K. H. Extracellular matrix optimization for enhanced physiological relevance in hepatic tissue-chips. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 3016. 10.3390/polym13173016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. B.; et al. Inflamed neutrophils sequestered at entrapped tumor cells via chemotactic confinement promote tumor cell extravasation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, 7022–7027. 10.1073/pnas.1715932115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M.; Ono D.; Sugita S. Mechanophenotyping of B16 melanoma cell variants for the assessment of the efficacy of (−)-epigallocatechin gallate treatment using a tapered microfluidic device. Micromachines (Basel) 2019, 10, 207. 10.3390/mi10030207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama K.; et al. Generation of metabolically functioning hepatocytes from human pluripotent stem cells by FOXA2 and HNF1α transduction. J. Hepatol 2012, 57, 628–636. 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccalton-Banks L.; Liew C.; Bhandari R.; Fry J.; Shakesheff K. Long-term culture of functional liver tissue: Three-dimensional coculture of primary hepatocytes and stellate cells. Tissue Eng. 2003, 9, 401–410. 10.1089/107632703322066589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J.; Miermont A.; Lim C. T.; Kamm R. D. A 3D microvascular network model to study the impact of hypoxia on the extravasation potential of breast cell lines. Sci. Rep 2018, 8, 1–11. 10.1038/s41598-018-36381-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhas M.; Engelmayr G. C.; Fontanella A. N.; Palmer G. M.; Bursac N. Biomimetic engineered muscle with capacity for vascular integration and functional maturation in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 5508–5513. 10.1073/pnas.1402723111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzel S. G. M.; Platt R. J.; Subramanian V.; Pearl T. M.; Rowlands C. J.; Chan V.; Boyer L. A.; So P. T. C.; Kamm R. D. Microfluidic device for the formation of optically excitable, three-dimensional, compartmentalized motor units. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501429. 10.1126/sciadv.1501429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto Y.; Kato-Negishi M.; Onoe H.; Takeuchi S. Three-dimensional neuron-muscle constructs with neuromuscular junctions. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 9413–9419. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niespodziana K.; Stenberg-Hammar K.; Megremis S.; Cabauatan C. R.; Napora-Wijata K.; Vacal P. C.; Gallerano D.; Lupinek C.; Ebner D.; Schlederer T.; Harwanegg C.; Soderhall C.; van Hage M.; Hedlin G.; Papadopoulos N. G.; Valenta R. PreDicta chip-based high resolution diagnosis of rhinovirus-induced wheeze. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2382. 10.1038/s41467-018-04591-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon J. S.; et al. Human 3D vascularized organotypic microfluidic assays to study breast cancer cell extravasation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, 214–219. 10.1073/pnas.1417115112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer S.; Blocki A.; Cheung M. C. Y.; Wan Z. H. Y.; Mehrjou B.; Kamm R. D. Lectin staining of microvascular glycocalyx in microfluidic cancer cell extravasation assays. Life 2021, 11, 179. 10.3390/life11030179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh D.; et al. Reconstituting organ-level lung functions on a chip. Science (1979) 2010, 328, 1662–1668. 10.1126/science.1188302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J.; Ching H.; Yoon J. K.; Jeon N. L.; Kim Y. T. Microvascularized tumor organoids-on-chips: advancing preclinical drug screening with pathophysiological relevance. Nano Convergence 2021, 8, 12. 10.1186/s40580-021-00261-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke G. A.; Hartse B. X.; Niaraki Asli A. E.; Taghavimehr M.; Hashemi N.; Abbasi Shirsavar M.; Montazami R.; Alimoradi N.; Nasirian V.; Ouedraogo L. J.; Hashemi N. N. Advancement of sensor integrated organ-on-chip devices. Sensors (Switzerland) 2021, 21, 1367. 10.3390/s21041367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]