ABSTRACT

Objective: To conduct a pilot randomised controlled trial examining the feasibility, acceptability and efficacy of MEmory Training for Recovery-Adolescent (METRA) in improving psychological symptoms among Afghan adolescent boys following a terrorist attack.

Method: A pilot randomised controlled trial compared METRA to a Control Group, with a three-month follow-up. The study occurred in Kabul (June-November 2022). Fifty-eight boys aged 14–19 years (Mage = 16.70, SD = 1.26) with heightened posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms were recruited through a local school that had recently experienced a terrorist attack. Participants were randomised 1:1 to receive METRA (n = 28) (10 session group-intervention) or Control (n = 30) (10 group-sessions of study skills). Primary outcomes were self-reported PTSD symptoms at post-intervention. Secondary outcomes included self-reported anxiety, depression, Afghan-cultural distress symptoms and psychiatric difficulties.

Results: There were challenges in youth participation related to security and competing education demands. For those who did complete METRA, METRA was deemed feasible and acceptable. Following the intent-to-treat principle, linear mixed effects models found at posttreatment the METRA group had a 20.89-point (95%CI −30.66, −11.11) decrease in PTSD symptoms, while the Control Group had a 1.42-point (95%CI −8.11, 5.27) decrease, with the group over time interaction being significant (p < .001). METRA participants had significantly greater reductions in depression, anxiety, Afghan-cultural distress symptoms and psychiatric difficulties than did Controls. All gains were maintained at three-month follow-up.

Conclusions: With some modifications, METRA appears a feasible intervention for adolescent boys in humanitarian contexts in the aftermath of a terrorist attack.

KEYWORDS: Adolescent, terrorist attack, Memory Training for Recovery-Adolescent, trauma, depression

HIGHLIGHTS

Very few adolescents in Afghanistan receive evidence-based psychological interventions.

MEmory Training for Recovery-Adolescents was associated with significant reductions in psychological symptoms.

With some modifications, MEmory Training for Recovery-Adolescents appears a feasible intervention for adolescent boys in humanitarian contexts in the aftermath of a terrorist attack.

Abstract

Objetivo: Realizar un ensayo piloto controlado aleatorio que examine la viabilidad, aceptabilidad y eficacia de MEmory Training for Recovery-Adolescent (Entrenamiento de la Memoria para la Recuperación-Adolescente; METRA) para mejorar los síntomas psicológicos entre los adolescentes afganos después de un ataque terrorista.

Método: Un ensayo aleatorizado piloto y controlado comparó METRA con un grupo de control, con un seguimiento de tres meses. El estudio tuvo lugar en Kabul (junio-noviembre de 2022). Cincuenta y ocho niños de 14 a 19 años (Medad = 16.70, SD = 1.26) con síntomas elevados de trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT) fueron reclutados a través de una escuela local que recientemente había experimentado un ataque terrorista. Los participantes fueron aleatorizados 1:1 para recibir METRA (n = 28) (10 sesiones grupales de intervención) o Control (n = 30) (10 sesiones grupales de habilidades de estudio). Los resultados primarios fueron síntomas de TEPT auto reportados después de la intervención. Los resultados secundarios incluyeron ansiedad auto reportada, depresión, síntomas de angustia cultural afgana y dificultades psiquiátricas.

Resultados: Hubo desafíos en la participación de los jóvenes relacionados con la seguridad y las demandas de competencias educativas. Para aquellos que completaron METRA, METRA se consideró factible y aceptable. Siguiendo el principio de intención de tratar, los modelos lineales de efectos mixtos encontrados en el postratamiento, el grupo METRA tuvo una disminución de 20.89 puntos (IC 95%: −30,66, −11,11) en los síntomas de TEPT, mientras que el grupo de control tuvo una disminución de 1.42 puntos (95% %IC −8.11, 5.27), siendo significativa la interacción del grupo en el tiempo (p < .001). Los participantes de METRA tuvieron reducciones significativamente mayores en depresión, ansiedad, síntomas de angustia cultural afgana y dificultades psiquiátricas que los controles. Todas las ganancias se mantuvieron a los tres meses de seguimiento.

Conclusiones: Con algunas modificaciones, METRA parece una intervención factible para los adolescentes varones en contextos humanitarios después de un ataque terrorista.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Adolescente, ataque terrorista, MEmory for Recovery-Adolescent, trauma, depresión

Abstract

目的:进行一项随机对照试验,考查青少年恢复记忆训练(METRA)在改善阿富汗男孩恐怖袭击后心理症状方面的可行性、可接受性和有效性。

方法:一项随机对照试验将 METRA组 与对照组进行了比较,并进行了三个月的随访。该研究在喀布尔进行(2022 年 6 月至 11 月)。招募了 58 名在当地一所学校最近经历了恐怖袭击、患有严重创伤后应激障碍 (PTSD) 症状的 14–19 岁男孩(平均年龄 = 16.70,SD = 1.26)。 参与者以 1:1 的比例随机分配接受 METRA组 (n = 28),10 次小组干预)或对照组(n = 30,10 次小组学习技能)。主要结果是干预后自我报告的PTSD症状。次要结果包括自我报告的焦虑、抑郁、阿富汗文化困扰症状和精神困难。

结果:青年参与安全和竞争性教育需求具有挑战。 对于那些完成 METRA 的人来说,METRA 被认为是可行且可接受的。遵循意向治疗原则,线性混合效应模型发现,治疗后 METRA 组的 PTSD 症状减少了 20.89 分(95% CI −30.66,−11.11),而对照组则减少了 1.42 分(95%CI −8.11, 5.27),随时间与组别交互效应显著 (p < .001)。 与对照组相比,METRA 参与者的抑郁、焦虑、阿富汗文化困扰症状和精神困难显著减少。所有好处均在三个月的随访中得以维持。

结论:在人道主义背景下,经过一些修改的METRA 对恐怖袭击后的青少年男孩来说似乎是一种可行的干预措施。

关键词: 青少年, 恐怖袭击, 青少年恢复记忆训练, 创伤;抑郁

Adolescents in Afghanistan have been exposed to one of the world’s most severe humanitarian contexts (Ahmadi et al. (2022). Exposure to social injustices, conflict and terrorist attacks have significantly impacted youth mental health (Panter-Brick et al., 2009). Among a community sample of 376 Afghan adolescents, around half met criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression or anxiety (Ahmadi et al., 2022). However, due to a shortage of professionals and limited services, few adolescents receive evidence-based psychological interventions (Alemi et al., 2018; Juengsiragulwit, 2015). There is a need for evidence-based psychological interventions that can be readily implemented in Afghanistan.

MEmory Training for Recovery-Adolescent (METRA) is an evidence-based, low-intensity training targeting two memory disruptions associated with PTSD. PTSD is associated with difficulties recalling specific autobiographical memories (i.e. memories of events that occurred at a particular time and place) and is instead associated with overgeneral memory retrieval (Williams et al., 2007). Among adolescents, overgeneral memory retrieval predicts on-going psychological difficulties that can continue into adulthood (Hitchcock et al., 2014) and is associated with executive functioning impairments, rumination, avoidance, and problems accessing specific information about the past and future; processes instrumental in PTSD recovery (Hitchcock et al., 2014; Williams et al., 2007). As memory specificity training improves PTSD symptoms (Moradi et al., 2014), Module 1 targets memory specificity (Ahmadi et al., 2023). Second, given trauma memories are often intrusive and distressing, evidence-based PTSD interventions target the trauma memory (Brewin, 2011). Module 2 is a writing for recovery, written exposure training, whereby adolescents simply write about their trauma (Ahmadi et al., 2023).

METRA appears promising in improving posttraumatic distress among adolescents in humanitarian contexts. The efficacy, acceptability and feasibility of Module 2 (trauma writing) was assessed among Afghan adolescent girls following a terrorist attack (Ahmadi et al., 2022). Afghan adolescent girls assigned to Module 2 reported high satisfaction, had high acceptability (15% drop-out) and significantly less PTSD symptomatology compared to no-contact controls at post-intervention and follow-up (Ahmadi et al., 2022). However, this study only examined Module 2 of METRA. Recently, the efficacy of METRA (Modules 1 and 2) in improving psychological symptoms among war-exposed Afghan adolescent girls was examined (Ahmadi et al., 2023). Participants assigned to METRA had significantly greater reductions in symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety, Afghan-cultural distress and psychiatric difficulties than did Treatment as Usual participants. All gains were maintained at three-month follow-up. Dropout in the METRA group was 22.5% (Ahmadi et al., 2023). Thus, METRA may provide a feasible intervention for adolescents in humanitarian contexts. However, both studies focused on girls. Thus, there is a need to explore METRA among adolescent boys in a humanitarian context.

This pilot randomised controlled trial examined the feasibility, acceptability and efficacy of METRA in addressing PTSD symptoms among adolescent boys in the aftermath of a terrorist attack in Afghanistan. We aimed to investigate (1) feasibility and acceptability of METRA; (2) efficacy of METRA in reducing PTSD and other psychological symptoms; and (3) whether any improvements were maintained at three-month follow-up. We predicted adolescents in the METRA group would have significantly fewer PTSD and general psychological symptoms post-intervention and at three-month follow-up than controls.

1. Method

1.1. Design

The study was approved by Afghanistan Public Health Ministry (A.1121.0385). It was a follow-up pilot randomised controlled trial of the preregistered trial (ACTRN126210011608201). We compared METRA to a Control group and assessed participants at baseline, post-Module 1, post-Module 2, and 3-month follow-up.

1.2. Participants

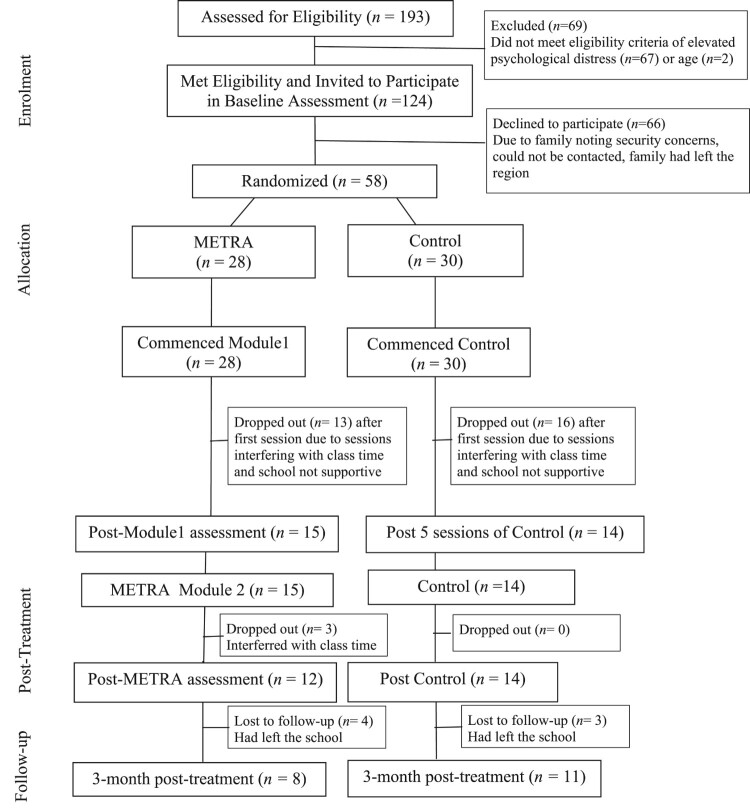

Adolescent boys were approached through a government boys’ school in Kabul, which had recently experienced a terrorist bombing. We screened 193 boys, of which 124 boys (Mage = 17.19 years, SD = 1.18) met eligibility criteria and were invited to participate. Sixty-six adolescents declined. Fifty-eight participants (aged 14–19 years, Mage = 16.70, SD = 1.24) were randomly allocated to METRA or Control. Eligibility criteria were: (1) aged 14–19 years; (2) exposed to the school bombing; (3) experiencing elevated posttraumatic distress, defined as ≥25 on the Child Revised Impact of Event Scale-13 (CRIES-13) (Child Outcomes Research Consortium, 2021); and (4) able to complete the tasks in Dari or Pashto. Exclusion criteria were: high levels of suicidality; unmanaged psychosis/manic episodes in the past month; and/or presence of head trauma/organic brain damage – assessed by a clinical psychologist during a pre-study interview. Given the effect sizes observed in previous studies2 (Ahmadi et al., 2022, 2023), a sample size of 10–15 adolescents per treatment arm was estimated based on current approaches for estimating sample size for pilot studies (Whitehead et al., 2016). Figure 1 depicts the CONSORT Flow Diagram (see Supplementary Material for CONSORT checklist).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participant recruitment and assessment.

1.3. Procedure

Enrolment began in June 2022 and data collection ended in November 2022. Informed consent was obtained from adolescents and parents/guardians. Following baseline assessment, participants were randomised in a 1:1 ratio to METRA or Control using a computer-generated randomisation sequence. A researcher in Kabul (independent of intervention delivery) monitored generation of the allocation sequence, participant enrolment, and assigning participants to interventions. Assessments were conducted by independent raters who had no therapeutic relationship with participants and were blind to group allocation. Those allocated to METRA received Module 1 (five sessions delivered within a week) and then four days later Module 2 (five sessions delivered daily). The Control Group received 10 sessions (similarly spaced to METRA). Both interventions were delivered at the school.

1.4. Feasibility and acceptability

Feasibility of recruitment was assessed by determining the number of adolescents who were approached and agreed to participate in METRA. Acceptability of intervention was assessed by measuring loss to follow-up. We determined acceptability of treatment based on the number of METRA sessions attended. Following METRA and at follow-up, we conducted 10 interviews with adolescents and facilitators to gain feedback on METRA.

1.5. Measures

CRIES-13 (Child Outcomes Research Consortium, 2021) is a 13-item self-report measure of PTSD, with higher scores indicating greater PTSD symptoms. The CRIES-13 has good psychometric properties (Angold et al., 1995) and been used with Afghan adolescents (Panter-Brick et al., 2009). Internal consistency was good (McDonald’s Omega = .86).

Secondary outcomes were assessed using the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire-Short Form (depression) (Angold et al., 1995), Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale (anxiety) (Reynolds & Richmond, 1978), Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (psychiatric difficulties) (Goodman et al., 1998) and Afghan Symptom Checklist (culture-specific idioms of distress) (Miller et al., 2006). All measures have been used with Afghan youth (Ahmadi et al., 2022; Panter-Brick et al., 2009). Internal consistency was good (McDonald’s Omegas > .78) (see Supplementary Material).

1.6. Interventions

1.6.1. Control

The Control group received group study sessions delivered by a local non-government organisation. This course of intervention is commonly delivered within Kabul schools; 10 daily sessions of an adolescent group programme (8–12 adolescents/group) that focused on creative and critical thinking, study methods and problem-solving.

1.6.2. METRA

METRA is a manualized group training comprised of two modules. Module 1 is based on MEmory Specificity Training (Raes et al., 2009). Session 1 provided psycho-education. In Sessions 1–3 participants recalled specific memories in response to positive, neutral and negative cues. For homework participants generated a specific memory for 10 cues. Session 4 involved exercises using negative and ‘counterpart’ positive cues. Session 5 included further practice and a summary. Module 2 was a modified form of written exposure therapy and writing for recovery (Kalantari et al., 2012; Sloan et al., 2018). Session 1 included a brief outline of Module 2. In Sessions 1–5 adolescents repeatedly wrote about the terrorist attack for a full 30-min. After the 30-mins the facilitator asked adolescents to finish up and ensured adolescents were ready to leave.

1.7. Facilitators and treatment fidelity

METRA was delivered by counsellors with mental health training. Each facilitator received 6–8 h of METRA training provided by a clinical psychologist. Facilitators received weekly supervision from clinical psychologists and were able to access clinical psychologists daily if needed regarding the delivery of METRA, managing participant distress, or regarding their self-care.3 A random 25% of the audio-recorded sessions were rated for manual adherence using a Therapist Adherence Scoring sheet. Participants were requested to not discuss the treatment with others.

1.8. Data analysis plan

Data were analysed using Stata (Version 17). Analyses were on intent-to-treat principle, with all randomised participants analysed in their allocation condition. Objectives 2 and 3 were examined using linear mixed effects models with intervention type, time, and intervention by time interaction as fixed factors. Repeated assessments of individuals were modelled as random intercept. Of primary interest was the intervention by time interaction, which compared the levels of change over time in outcomes of the METRA and Control groups.4

2. Results

2.1. Group characteristics

Group characteristics are presented in Table 1. Supplemental Table 2 provides a summary of baseline data for those who dropped-out and those who completed the interventions. Overall sample size for primary analyses included 28 adolescents in the METRA group and 30 adolescents in the Control group.

Table 1.

Demographic variables.

| Variable | METRA Group | Control Group | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age – years | 16.87 (1.46) | 16.50 (1.02) | t(27) = .78, p = .44 |

| School Year (9:10:11:12) | 2:5:5:3 | 1:3:7:3 | χ2(3,N= 29) = 1.13, p = .77 |

| Number of Family Members | 8.30 (3.40) | 8.38 (2.79) | t(21) = .07, p = .95 |

| Birth order in Family 1:2:3:4:5:6:7:8 | 4:6:1:1:1:1:1 | 4:4:3:0:0:1:1 | χ2(6,N = 28) = 3.27, p = .77 |

| Father’s Education Level (Illiterate: High School:University) | 13:1:1 | 13:0:0 | χ2(2,N = 28) = 1.87, p = .39 |

| Mother’s Education Level (Illiterate: High School:University) | 13:1:1 | 13:1:0 | χ2(2,N = 29) = .97, p = .62 |

Note: Not all participants provided age and number of family members.

2.2. Feasibility and acceptability

While 124 boys were invited to participate, 66 adolescents declined because their families (a) expressed security concerns, (b) could not be contacted, or (c) had left the region. Acceptability of randomisation was high; no participants dropped out after they learned their randomisation status. While all participants allocated to METRA commenced METRA, from Session 2 onwards there were only 15 adolescents in the METRA group (13 dropped-out; 46.43%) and 14 adolescents in the Control group (16 dropped-out; 43.33%), χ2(1,58) = 0.06, p = .80. In both groups, participants reported they had dropped out because the programmes interfered with their class time and teachers did not support their attendance. The demographics and baseline symptoms did not differ significantly between those who dropped-out and those who completed the interventions.5 During Module 2, three participants dropped-out of METRA due to school commitments, while no Control participants dropped-out. Seven participants (METRA n = 4, Controls n = 3) were lost to follow-up; all participants had left the school.

Table 2 summarises qualitative findings. Adolescents noted improvements in cognition, mood and sleep. Several adolescents perceived participating in METRA as a sign of weakness and that boys do not participate in this type of programme. Facilitators noted several teachers were not supportive of METRA. The students belonged to various classes and some teachers were particularly stringent and did not permit their students to participate in the study. Some boys felt ashamed to participate, as METRA was run at school. Participants felt greater satisfaction with METRA after the three months than immediately following METRA. Most participants had continued using METRA skills and taught these skills to others. Some participants noted while in Module 2 they initially felt anger and distress, they now felt less afraid. For those who completed METRA there were no important harms or unintended effects reported.

Table 2.

Summary of the qualitative feedback.

| Theme | Details |

|---|---|

| Post-Intervention Feedback | |

| Memory Improvement | Some participants mentioned improvements in their memory. In this regard, they were more satisfied with Module 1. |

| Increased Concentration | Several participants reported that they now have better concentration at school. |

| Reduction in Sadness and Depression | Many participants reported that after METRA they felt less sad and happier. |

| Improved Sleep | Several participants reported that they now fall asleep easily and no longer have nightmares. |

| Improved Decision-Making | Some participants noted they now have the ability to make better decisions. |

| Gender Influences | Several participants perceived METRA being for those who are weak and that boys do not do this type of programme, with one adolescent noting, ‘I think I am strong. I shouldn't tell anyone my story and I shouldn't show my feelings’. |

| School Context | Facilitators noted that several teachers were not supportive of the programme and that given the programme was run in school, some boys felt ashamed to participate. |

| Feedback at Follow-up | |

| Greater Satisfaction after Three Months | All participants reported that they felt greater satisfaction after the three months than immediately following METRA. |

| Continued Use of Skill | Most participants reported that they had applied the techniques learnt in METRA to other similar traumas they had experienced. For instance participants noted that after the Kaj terrorist attack (September 2022) they used the techniques learnt during METRA (e.g. the Stop Technique in Module 1) to help them to face the trauma. |

| Taught Friends | Several participants noted that they had taught the skills learnt in METRA to their friends and their friends had noted that it was useful for them. |

| Initial Anger and Distress | Some participants noted that initially in Module 2, writing about the terrorist attack made them angry, upset and increased their heart rate. A few participants noted that they did not like it. However, now after the intervention and time passing, they are no longer afraid to remember and speak about the terrorist attack. They noted that they now easily remember details from their lives, talk to others about these memories and that it even feels good talking about these memories. |

| Remembering Positive Memories | For some participants they noted that a highlight of METRA was remembering specific positive events that had happened in their lives in Module 1. |

2.3. Symptomatology post-Intervention

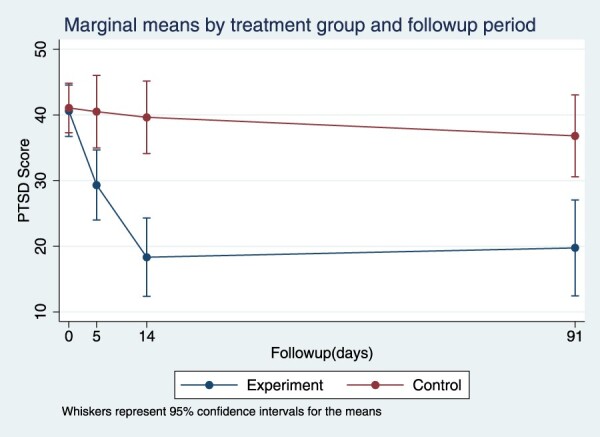

Descriptive data for PTSD symptom outcomes is provided in Table 3 and Figure 2. We found for PTSD symptoms the group over time interaction was significant, p < .001. At post-intervention, the METRA group had a 20.89-point (95%CI −30.66, −11.11) decrease in PTSD symptoms from baseline, while Controls had a 1.42-point (95%CI −8.11, 5.27) decrease.

Table 3.

Outcome measures (marginal means [95%CI]) by condition and time point.

| Outcome Measure | Baseline | Post-Module 1 | Post-Intervention | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD Symptoms | ||||

| METRA | 40.64 [36.74–44.55] | 29.33 [24.00–34.67] | 18.33 [12.37–24.30] | 19.75 [12.44–27.06] |

| Control | 41.07 [37.29–44.84] | 40.50 [34.98–46.02] | 39.64 [34.12–45.17] | 36.82 [30.59–43.05] |

| Depression Symptoms | ||||

| METRA | 13.43 [11.11–15.75] | 9.75 [6.85–12.66] | 6.32 [3.18–9.45] | 5.41 [1.79–9.03] |

| Control | 14.35 [11.94–16.75] | 14.14 [11.14–17.15] | 13.86 [10.85–16.86] | 11.51 [8.26–14.75] |

| SDQ Difficulties | ||||

| METRA | 16.64 [14.67–18.62] | 13.24 [10.68–15.79] | 9.85 [7.06–12.64] | 9.67 [6.39–12.95] |

| Control | 17.81 [15.76–19.86] | 16.51 [13.87–19.15] | 18.01 [15.37–20.65] | 16.66 [13.76–19.55] |

| Afghan-Cultural Distress Symptoms | ||||

| METRA | 41.79 [36.18–47.39] | 27.34 [20.18–34.50] | 17.92 [10.13–25.71] | 17.88 [8.79–26.98] |

| Control | 43.27 [37.45–49.09] | 41.21 [33.80–48.62] | 42.64 [35.23–50.05] | 35.45 [27.37–43.52] |

| Anxiety | ||||

| METRA | 19.64 [17.52–21.76] | 21.20 [18.60–23.81] | 17.45 [14.65–20.25] | 15.34 [12.15–18.54] |

| Control | 20.92 [18.72–23.12] | 24.99 [22.29–27.68] | 25.27 [22.58–27.97] | 22.54 [19.64–25.43] |

Note: SDQ: Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

Figure 2.

Marginal means for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms by treatment group and follow-up period.

Descriptive data for outcome of psychological symptoms are provided in Table 3 and Supplemental Figures 1–4. At post-intervention, compared to baseline, the METRA group had a 6.62-point (95%CI −10.72, −2.52) decrease in depression symptoms (Controls had a 0.49-point [95%CI −3.31, 2.33] decrease), 6.54-point (95%CI −10.07, −3.02) decrease in anxiety symptoms (Controls had a 4.35-point [95%CI 1.92, 6.78] increase), 23.24-point (95%CI −33.86,−12.61) decrease in Afghan-cultural distress symptoms (Controls had a 0.63-point [95%CI −7.94, 6.68] decrease) and 6.99-point (95%CI −10.90,−3.09) decrease in psychiatric difficulties (Controls had a 0.20-point [95%CI −2.49, 2.89] increase). For all findings p < .01.

2.4. Follow-up analyses

At follow-up, compared to baseline, the METRA group had an 16.64-point (95%CI −27.68, −5.61) decrease in PTSD symptoms (Controls = 4.25-point, 95%CI −11.53, 3.04, decrease) (p < .01), 5.18-point (95%CI −9.82, −0.53) decrease in depression (Controls = 2.84-point, 95%CI −5.92, 0.24, decrease) (p = .03), 5.91-point (95%CI −9.91, −1.92) decrease in anxiety (Controls = 1.61-point, 95%CI −1.03, 4.26, increase)(p < .01), 16.08-point (95%CI −28.13, −4.03) decrease in Afghan-cultural distress symptoms (Controls = 7.82-point, 95%CI −15.81, 0.16, decrease) (p < .01), and 5.82-point (95%CI −10.25, −1.39) decrease in psychiatric difficulties (Controls = 1.15-point, 95%CI −4.09, 1.78, decrease)(p = .01).

3. Discussion

This study explored the feasibility, acceptability and efficacy of METRA in addressing psychological distress among Afghan adolescent boys. Our findings are promising but highlight the need for some modifications. There were challenges in youth participation; many boys were unable to participate or dropped-out due to extremely precarious security conditions in Kabul at the time. Additionally, several teachers were not supportive of the programme due to the intervention taking students out of class. These concerns were similarly observed in the Control Group, suggesting they were not METRA-specific but rather reflect competing tensions between providing mental health programmes and educational needs. Before the intervention, we provided information about METRA to the school and teachers. However, we did not have an established training programme for the teachers as there were over 500 teachers in the school and it was practically impossible to establish effective communication and coordination with all staff, particularly as the Taliban and school administration strictly restricted any gatherings. While qualitative data revealed participants reported improvements in memory, concentration, mood, sleep and decision-making, participants also expressed some concerns regarding how METRA was perceived, with some boys noting participating in METRA was seen as a sign of weakness and shameful. Drop-out was considerably higher than found in previous METRA studies (Ahmadi et al., 2022, 2023). Thus, METRA may be better implemented outside of the school context. Alternatively, there may be benefit in METRA being led by teachers and future planning ensuring substantial time in engaging with the school principal, programme advisors and teachers. There may also be a need for further gender-specific considerations.

For those who did complete METRA, METRA appeared feasible and acceptable. At post-intervention adolescents allocated to METRA had fewer symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety, Afghan-cultural distress and psychiatric difficulties than Controls. Improvements were maintained at follow-up. These improvements were similar to that observed in previous METRA studies (Ahmadi et al., 2022, 2023). This study extends the efficacy of METRA to adolescent boys in a humanitarian context.

METRA is a low intensity intervention that can be delivered by those with minimal training. This is important as Afghanistan has exceptionally limited mental health services (Alemi et al., 2018). It is important to note METRA was implemented in exceptionally difficult circumstances (i.e. security concerns, recent socio-political changes). It is essential psychological research continues in humanitarian contexts within low-income countries, as these complexities reflect the reality of these contexts. Afghan youth are needing, and deserving, of evidence-based interventions.

There are several limitations. We focused on adolescents in Kabul. Thus, generalizability may be limited. The lack of long-term follow-up precludes us from knowing whether treatment gains were maintained. As a pilot study, our sample size was small, particularly at follow-up. Thus, findings should be interpreted with caution. Given the long-term conflict in Afghanistan, all participants had been exposed to other trauma types which may have impacted mental health and responsiveness to METRA. However, we did not assess previous trauma exposure because we aimed to make each assessment session brief for security reasons. There were differences between the METRA and Control Groups (e.g. no homework in the Control Group) that may have influenced findings. Another limitation was that we did not collect qualitative data from Controls. Nevertheless, this study suggests METRA, with some modifications, is a promising intervention for adolescent boys in complex humanitarian contexts and further research is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Enhancing Learning and Research for Humanitarian Assistance.

Notes

Registration ACTRN12621001160820 focused on adolescent girls. This is a follow-up study with similar design and measures; however, the focus of the current study was on adolescent boys. The trial protocol can be accessed by contacting the authors.

For Ahmadi et al. (2023), between condition effect size (METRA vs Treatment as Usual) for PTSD symptoms was large (d = 1.71) (N = 125). For Ahmadi et al. (2022), those who received Module 2 of METRA had significantly lower PTSD symptom severity than the no-contact control group (ηp2 = 0.17) (N = 80). Based on current recommendations for medium to large effect sizes, estimated pilot trial sample size per treatment arm is 10–15 participants (Whitehead et al., 2016).

The assessors also had daily access to the clinical psychology team.

See Supplemental Material for a summary of Post-Module 1 analyses.

The only significant difference observed was for Afghan-cultural distress symptoms, whereby those who completed the Control intervention had significantly higher Afghan-cultural distress symptoms at baseline than those that dropped out of the Control intervention.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The research dataset can be accessed at https://osf.io/f8dbh/.

References

- Ahmadi, S. J., Jobson, L., Earnest, A., McAvoy, D., Musavi, Z., Samim, N., & Sarwary, S. A. (2022). Prevalence of poor mental health among adolescents in Kabul, Afghanistan, as of November 2021. JAMA Network Open, 5(6), e2218981. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.18981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, S. J., Jobson, L., Musavi, Z., Rezwani, S. R., Amini, F. A., Earnest, A., Samim, N., Akbar Sawary, S. A., Abbas Saraway, S. A., & McAvoy, D. (2023). A randomized controlled trial of MEmory Training for recovery-adolescent among adolescent girls in Afghanistan. JAMA Network Open, 6(3), e236086. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.6086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, S. J., Musavi, Z., Samim, N., Sadeqi, M., & Jobson, L. (2022). Investigating the feasibility, acceptability and efficacy of using modified-written exposure therapy in the aftermath of a terrorist attack on symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder among Afghan adolescent girls. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 826633. 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.826633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemi, Q., Stempel, C., Koga, P. M., Stempel, C., Koga, P. M., Montgomery, S., Smith, V., Sandhu, G., Villegas, B., & Requejo, J. (2018). Risk and protective factors associated with the mental health of young adults in Kabul, Afghanistan. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 71. 10.1186/s12888-018-1648-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold, A., Costello, E. J., Messer, S. C., & Pickles, A. (1995). Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 5(4), 237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Brewin, C. R. (2011). The nature and significance of memory disturbance in posttraumatic stress disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7(1), 203–227. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Outcomes Research Consortium . (2021). Child revised impact of events scale. Retrieved January 10, 2021, from https://www.corc.uk.net/outcome-experience-measures/child-revised-impact-of-events-scale/.

- Goodman, R., Meltzer, H., & Bailey, V. (1998). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 7(3), 125–130. 10.1007/s007870050057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock, C., Nixon, R. D., & Weber, N. (2014). A review of overgeneral memory in child psychopathology. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(2), 170–193. 10.1111/bjc.12034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juengsiragulwit, D. (2015). Opportunities and obstacles in child and adolescent mental health services in low- and middle-income countries: A review of the literature. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health, 4(2), 110. 10.4103/2224-3151.206680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalantari, M., Yule, W., Dyregrov, A., Neshat-Doost, H., & Ahmadi, S. J. (2012). Efficacy of writing for recovery on traumatic grief symptoms of Afghani refugee bereaved adolescents: A randomized control trial. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 65(2), 139–150. 10.2190/OM.65.2.d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K. E., Omidian, P., Quraishy Abdul Samad, Quraishy Naseema, Nasiry Mohammed Nader, Nasiry Seema, Karyar Nazar Mohammed, Yaqubi Abdul Aziz (2006). The Afghan symptom checklist: A culturally grounded approach to mental health assessment in a conflict zone. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(4), 423–433. 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, A. R., Moshirpanahi, S., Parhon, H., Mirzaei, J., Dalgleish, T., & Jobson, L. (2014). A pilot randomized controlled trial investigating the efficacy of memory specificity training in improving symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 56, 68–74. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panter-Brick, C., Eggerman, M., Gonzalez, V., & Safdar, S. (2009). Violence, suffering, and Mental health in Afghanistan: A school-based survey. The Lancet, 374(9692), 807–816. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raes, F., Williams, J. M. G., & Hermans, D. (2009). Reducing cognitive vulnerability to depression: A preliminary investigation of MEmory Specificity Training in inpatients with depressive symptomatology. Journal of Behavioural Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 40(1), 24–38. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2008.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, C. R., & Richmond, B. O. (1978). What I think and feel: A revised measure of children’s manifest anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 6(2), 271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, D. M., Marx, B. P., Lee, D. J., & Resick, P. A. (2018). A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(3), 233–239. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, A. L., Julious, S. A., Cooper, C. L., & Campbell, M. J. (2016). Estimating the sample size for a pilot randomised trial to minimise the overall trial sample size for the external pilot and main trial for a continuous outcome variable. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 25(3), 1057–1073. 10.1177/0962280215588241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, J. M. G., Barnhofer, T., Crane, C., Herman, D., Raes, F., Watkins, E., & Dalgleish, T. (2007). Autobiographical memory specificity and emotional disorder. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 122–148. 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The research dataset can be accessed at https://osf.io/f8dbh/.