ABSTRACT.

Chikungunya fever is a global vector-borne viral disease. Patients with acute chikungunya are usually treated symptomatically. The arthritic phase may be self-limiting. However, many patients develop extremely disabling arthritis that does not improve after months. The aim of this study was to describe the treatment of chikungunya arthritis (CHIKA) patients. A medical records review was conducted in 133 CHIKA patients seen at a rheumatology practice. Patients were diagnosed by clinical criteria and confirmed by the presence of anti-chikungunya IgM. Patients were treated with methotrexate (20 mg/week) and/or leflunomide (20 mg/day) and dexamethasone (0–4 mg/day) for 4 weeks. At baseline visit and 4 weeks after treatment, Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28) and pain (using a visual analog scale) were ascertained. Five months after the end of treatment, patients were contacted to assess pain, tender joint count, and swollen joint count. The mean age of patients was 58.6 ± 13.7 years, and 119 (85%) were female. After 4 weeks of treatment, mean (SD) DAS28-erythrocyte sedimentation rate (6.0 [1.2] versus 2.7 [1.0], P < 0.001) and pain (81.8 [19.2] to 13.3 [22.9], P < 0.001) scores significantly decreased. A total of 123 patients were contacted 5 months after the end of treatment. Pain score, tender joint count, and swollen joint count significantly declined after 4 weeks of treatment, and the response was sustained for 5 months. In this group of patients with CHIKA, 4-week treatment induced a rapid clinical improvement that was maintained 5 months after the end of therapy; however, the contribution of treatment to these outcomes is uncertain.

INTRODUCTION

Chikungunya fever (CHIKF), caused by chikungunya virus (CHIKV), is a global vector-borne disease.1 The disease has waxed and waned for centuries and reemerged after the global expansion of Aedes mosquito vectors. Beginning in 2004, CHIKV spread through Africa, India, southern Europe, and Southeast Asia. Since 2013, chikungunya (CHIK) has returned to the Americas, with 2.9 million cases reported from 45 Western hemisphere countries including Brazil, where the CHIK epidemic remains active.1,2

The CHIKV causes a biphasic illness. Acute CHIKF is characterized by the abrupt onset of high fever, disabling polyarthritis, and maculopapular rash associated with other symptoms including headache, myalgia, nausea, and vomiting.3 Although CHIKF generally resolves within 5 to 14 days in most patients, more than 40% develop a second phase of arthritic manifestations.4 When arthritis persists for more than 3 months after the acute illness, this is defined as chronic chikungunya arthritis (CCA).3 Chronic chikungunya arthritis often causes disabling pain and polyarthritis that can mimic rheumatoid arthritis (RA).3–5

Patients with acute CHIKF are usually treated symptomatically. The arthritic phase may also be self-limiting.6 However, many patients develop extremely disabling arthritis that does not improve after months, despite common analgesics, opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), gabapentinoids, and corticosteroids. For these CCA patients, methotrexate (MTX) has been effective.7,8 In the chronic phase, the Brazilian guidelines recommend analgesics, followed by NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and in patients with refractory disease, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs); preferably, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) may be used for the treatment of joint symptoms, alone or in combination with MTX or sulfasalazine. For patients with persistent chikungunya arthritis (CHIKA), the guidelines recommend that MTX be administered at a minimum initial dose of 10 mg/week only when there are persistent joint symptoms or as a corticosteroid-sparing strategy and when there is difficulty in withdrawing corticosteroids after 6 to 8 weeks of use.9

Chikungunya virus infection causes chronic disabling pain in widespread epidemics. In Europe, Asia, and Africa, CHIKF cases have declined over the past several years, but in Brazil a major epidemic continues.1,9 In Brazil alone, more than 1 million cases of CHIKF have been reported since 2014, with 170,000 cases documented in 2022 (an incidence rate of 79.8 cases per 100,000 inhabitants).10 This has created a major public health concern. Chronic chikungunya arthritis limits functional capacity, affecting employment, leisure, family relations, and quality of life measures.11

In this study, we report our experience with a large cohort of CHIKA patients and describe their clinical features and treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

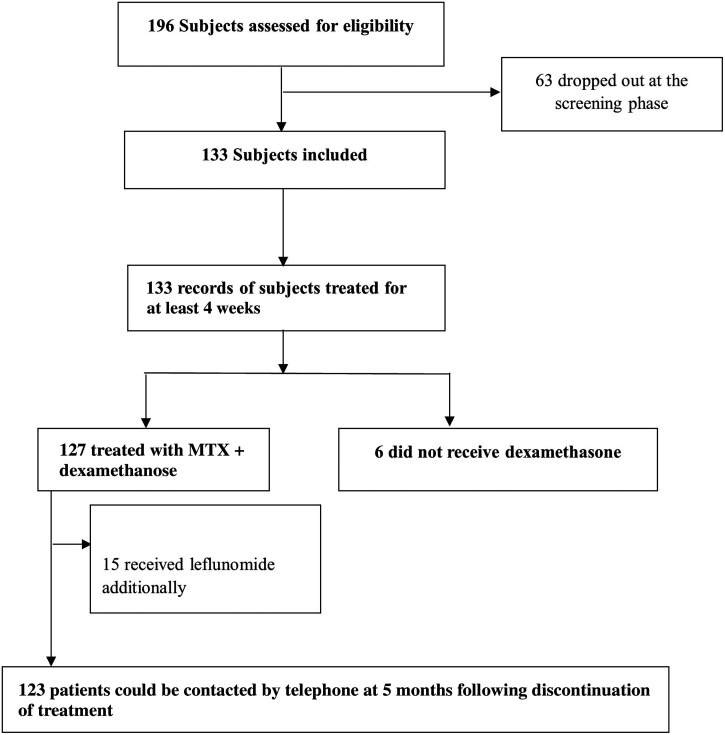

A retrospective study was conducted using medical records of CHIKA patients who attended the Institute of Diagnostic Medicine of Cariri, Brazil, between March and May 2022; 196 patients who developed inflammatory arthritis symptoms during a CHIKF outbreak were evaluated in a Brazilian rheumatology practice. Chikungunya arthritis was defined as acute (less than 15 days), subacute (16–90 days), or chronic (greater than 90 days). Among the 196 patients seen, 63 did not complete laboratory testing at baseline (40 patients) or did not return for a 4-week follow-up (23 patients) and were excluded from this report. Results are reported for 133 patients who completed a baseline and 4-week follow-up visit and in whom laboratory results confirmed the diagnosis of CHIKV infection by CHIKV-specific IgM serology by immunochromatography or ELISA (VIRCLIA IgM MONOTEST VCM063).

The medical records presented a clinical questionnaire appropriately created to assess patients with CHIK and included questions about the duration of the illness, the location of the arthritis/arthralgia, the number of tender and swollen joints, the intensity of the pain, previous treatment, and previous rheumatic disease. We also assessed patient demographics. We quantified pain using a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS)12 and calculated disease activity using the Disease Activity Score 28-erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28-ESR).13 Other tests such as complete blood count, hepatic transaminases, creatinine, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and serology for hepatitis B and C were requested to assess treatment safety.

At the first visit, treatment with MTX 20 mg/week (with folic acid supplementation 5 mg/week) and/or leflunomide was initiated in all patients, as well as dexamethasone 2 or 4 mg daily in all but six patients, regardless of the stage of the disease. After 4 weeks of treatment, the treatment response was assessed using the pain VAS and DAS28-ESR.13 After the week 4 assessment, MTX and/or leflunomide and dexamethasone were discontinued. Five months after the end of treatment, patients were contacted by telephone to assess the presence of symptoms and durability of the therapeutic response. During all consultations for these patients with CHIK, they had their pain assessed using the VAS. Whenever the scale was applied, it was explained to the patient. During the telephone contact via Whatsapp, the same figure that was used as a scale in the visits was presented to the patients.

Descriptive analysis was performed using mean, SD, median, first quartile, and third quartile, and statistical analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon test for two paired samples to compare the results between the first and second visits and the Friedman test for paired samples comparing the first visit, second visit, and contact after the end of treatment.

The data in this study were extracted retrospectively between March and May 2022 from patients’ medical records using a standardized structured questionnaire. This study was granted a waiver of approval, Protocol n° 5.562.805, by the Ethics Committee of the Regional University of Cariri (Ceará, Brazil).

RESULTS

Participants.

In total, 196 Brazilian patients were evaluated, 173 (88%) of whom attended the second visit. This information is important to highlight the intensity of the outbreak, as all these patients were seen in a single rheumatologist’s office. One hundred and thirty-three patients met the additional study criteria and were included in this report. Of the 133 patients, 119 (85%) were female. The mean (SD) age was 58.6 (13.7) years, with a median age of 58.0 years. The mean (SD) time between onset of symptoms of CHIKF and the first visit was 42.2 (20.5) days, with a median of 40.0 days. We stratified the disease duration into three groups: 13 (9.8%) were in the acute phase, 116 (87.2%) were in the subacute phase, and 4 (3.0%) were in the chronic phase. Notably, 81% of patients had bilateral and symmetric arthritis. The mean (SD) total joint count (TJC) and swollen joint count (SJC) were 17.2 (7.3) and 5.0 (6.6), respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic profile, affected joints, previous rheumatic diseases, and previous treatment in patients with CHIKA

| Number of patients | 133 |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean ± SD | 58.6 ± 13.7 |

| Median (range) | 58.0 (26–82) |

| Time between onset of symptoms and first visit (days) | |

| Mean ± SD | 42.16 ± 20.45 |

| Female, n (%) | 119 (89.5) |

| Affected joints, n (%) | |

| Wrists | 122 (91.7) |

| Proximal interphalangeal | 113 (86.9) |

| Ankles | 111 (83.4) |

| Shoulders | 100 (75.1) |

| Knees | 97 (72.9) |

| Metacarpophalangeal | 72 (54.1) |

| Elbows | 54 (40.6) |

| Prior treatment of CHIKA, n (%) | |

| Corticosteroids | 89 (66.9) |

| Acetaminophen or dipyrone | 78 (58.6) |

| Pregabalin, codeine, or tramadol | 19 (14.2) |

| NSAIDs | 6 (4.5) |

| DMARDs (MTX) | 1 (0.7) |

| Previous reported rheumatic diseases, n (%) | |

| Osteoarthritis | 27 (20.3) |

| Osteoporosis | 16 (12) |

| Tendinitis/bursitis | 6 (4.5) |

| Fibromyalgia | 4 (3) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 (1.5) |

| Rheumatic fever | 1 (0.75) |

CHIKA = chikungunya arthritis; DMARD = disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; MTX = methotrexate; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

At the initial clinic visit, 89 patients (66.9%) were taking corticosteroids including prednisone, prednisolone, dexamethasone, betamethasone, and deflazacort; 78 patients (58.6%) were taking common analgesics, and 19 patients (14.2%) were taking opioids or pregabalin for joint pain (Table 1). The duration of corticosteroid use varied from days to weeks, with daily doses of prednisone between 5 and 20 mg, dexamethasone 4 mg, betamethasone 5 mg, and deflazacort 6 to 30 mg, with little relief in reported pain.

At the first visit, the mean (SD) VAS score for pain was 81.8 (19.2) with a median of 80, reflecting severe pain. The mean (SD) baseline DAS28-ESR was 6.0 (1.2) with a median of 5.9 (Table 2). Using criteria established for DAS28-ESR interpretation in RA,13 105 (78.9%) were classified as having high disease activity, 27 (20.3%) had moderate disease activity, and only 1 (0.75%) had low disease activity at the first visit, despite previous treatments including corticosteroids and NSAIDs. Rheumatoid factor was positive in 22 patients (16.5%).

Table 2.

Disease activity (visual analog scale pain, DAS28-ESR) of N = 133 patients

| Disease activity | First visit (N = 133) | Second visit (N = 133) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual analog scale pain | |||

| Mean score (SD) | 81.8 (19.2) | 13.3 (22.9) | < 0.0001* |

| Median score (1st–3rd interquartile) | 80.0 (70.0–100) | 0.0 (0.0–20.0) | |

| DAS28-ESR | |||

| Mean score (SD) | 6.0 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.0) | < 0.0001* |

| Median score (1st–3rd interquartile) | 5.9 (5.5–6.7) | 2.4 (2.1–3.2) | |

DAS28 = the 28-joint Disease Activity Score; ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Wilcoxon test for two paired samples.

The baseline clinical characteristics of the 63 patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria for this report were similar to those of the patients included: 90.4% were female, the mean (SD) age was 51.9 (16.0) years, and the mean (SD) VAS score for pain was 80.1 (20.8). In this group, the mean (SD) time between the onset of CHIKF symptoms and the first visit was 36 (22.8) days.

After a mean (SD) of 4.7 (0.8) months from the end of treatment, it was possible to make telephone contact with 123 patients to assess pain (per VAS) and self-reported TJC and SJC. In this group, 110 patients (89.4%) were female. The mean (SD) age was 58.5 (13.8) years with a median age of 58 years (Table 3).

Table 3.

Demographic profile, previous rheumatic diseases, and previous treatment in patients with CHIKA followed after the end of treatment

| Prior treatment to chikungunya arthritis | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 123 |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean ± SD | 58.5 ± 13.8 |

| Median | 58.0 |

| Female | 110 (89.4) |

| Time between the end of treatment and telephone contact (months) | |

| Mean ± SD | 4.7 ± 0.8 |

| Prior treatment for chikungunya arthritis | |

| Corticosteroids | 73 (59.3) |

| Acetaminophen or dipyrone | 78 (63.4) |

| Pregabalin, codeine, or tramadol | 17 (13.8) |

| NSAIDs | 6 (4.8) |

| DMARDs (MTX) | 1 (0.81) |

| Previous reported rheumatic diseases | |

| Osteoarthritis | 26 (21.1) |

| Osteoporosis | 11 (8.9) |

| Tendinitis/bursitis | 6 (4.8) |

| Fibromyalgia | 4 (3.2) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 (1.6) |

| Rheumatic fever | 1 (0.8) |

CHIKA = chikungunya arthritis; DMARD = disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; MTX = methotrexate; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

CHIKA treatment.

Because of ongoing arthritis, at the first clinic visit 127 patients were treated for 4 weeks with MTX 20 mg weekly (10 mg for two doses over a 24-hour time period) and dexamethasone daily up to 4 mg/day with a mean (SD) dose 3.4 (1.1) mg. Six patients (4.5%) did not receive dexamethasone; 29 (21.8%) used 2 mg/day; and 98 (73.7%) used 4 mg/day for 4 weeks. Fifteen patients (11.3%) received leflunomide 20 mg in combination with MTX and dexamethasone because these cases were thought to be severe and to require combination therapy from the beginning (Figure 1). Among the patients receiving leflunomide, the mean (SD) VAS pain at the first visit was 92 (12.1). No other medications were prescribed as rescue therapy for worsening pain. No serious medication-related adverse effects were reported at 4-week follow-up.

Figure 1.

Subjects included and excluded, treatment, and follow-up.

Treatment and response.

Most patients reported significant improvement in joint pain and swelling within the first 2 weeks of treatment with MTX 20 mg/week and/or leflunomide 20 mg daily and dexamethasone 2 to 4 mg/daily. The VAS pain score improved from a mean (SD) of 81.8 (19.2), median 80 at the first visit to 13.3 (22.9) at 4 weeks (P < 0.0001). The mean DAS28-ESR was 6.0 (1.2), median 5.9 at the first visit. After 4 weeks of treatment, the mean DAS28-ESR decreased to 2.7 (1.0), median 2.4 (P < 0.0001) (Table 2). At the first visit, 83.5% of patients had severe pain (VAS ≥ 70). By the second visit at week 4, 86.4% of patients had mild pain (VAS ≤ 30). The mean (SD) TJC and SJC were 2.8 (5.5) and 0.8 (2.6), respectively. Insomnia was the most common adverse effect and was generally associated with dexamethasone use.

Among the 123 patients who could be contacted by telephone at 5 months after discontinuation of treatment, the mean (SD) VAS pain score was 27.3 (27.7). The mean (SD) self-reported TJC and SJC were 4.8 (5.6) and 1.6 (3.1), respectively (Table 4). In this group, 63.4% of patients had mild pain (VAS ≤ 30). During telephone follow-up, no serious adverse effects were reported.

Table 4.

Disease activity (visual analog scale pain, TJC, SJC) of N = 123 patients

| Disease activity | First visit (N = 123) | Second visit (N = 123) | Final visit (N = 123) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual analog scale pain | ||||

| Mean score (SD) | 82.0 (19.7) | 13.1 (22.8) | 27.3 (27.7) | < 0.0001* |

| Median score (1st–3rd interquartile) | 90.0 (70.0–100) | 0.0 (0.0–20.0) | 20.0 (0.0–50.0) | |

| TJC | ||||

| Mean score (SD) | 17.2 (7.5) | 2.8 (5.5) | 4.8 (5.6) | < 0.0001* |

| Median score (1st–3rd interquartile) | 18.0 (12.0–24.0) | 0.0 (0.0–3.0) | 2.0 (0.0–10.0) | |

| SJC | ||||

| Mean score (SD) | 5.0 (6.7) | 0.9 (2.6) | 1.6 (3.1) | < 0.0001* |

| Median score (1st–3rd interquartile) | 2.0 (0.0–9.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | |

SJC = swollen joint count; TJC = tender joint count.

Friedman test for paired samples.

DISCUSSION

Limited evidence is available to assess the utility of DMARDs in CHIKA.14 Most of our patients had used corticosteroids before the study and had severe pain at the first visit. Only one of them had previously used MTX, and none had used another DMARD.

We performed a systematic review on the treatment of chronic rheumatic manifestations of CHIK with MTX.7 Only one study by Javelle et al.15 evaluated the therapeutic response in a follow-up after the end of treatment. With a median follow-up time of 21 months (mean, 25 months), MTX led to a positive clinical response in 54 of 72 patients; seven cases developed bone destruction during MTX treatment, whereas recovery was achieved in six patients.

In a recent extensive systematic review, Webb et al.14 highlighted the global scarcity of evidence-based clinical management guidelines for CHIKV to provide optimal care and treatment of different at-risk populations and settings. For CHIKF, there is no effective antiviral treatment, so treatment at this stage is symptomatic. The goal of initial treatment is to control fever and pain, treat dehydration, treat any organ failure, and prevent iatrogenic complications and functional impairment.6,9 French guidelines recommend analgesic treatment of CHIKA during the first 3 weeks of illness with acetaminophen at first followed by weak opioids, tramadol alone or in combination with acetaminophen, and then codeine with acetaminophen. These guidelines do not recommend corticosteroids or NSAIDs.6

The World Health Organization published the “Guidelines on Clinical Management of Chikungunya Fever” in 2018, recommending acetaminophen as the drug of choice for CHIKA, with addition of other analgesics if acetaminophen does not provide relief. These same guidelines recommend NSAIDs if acetaminophen or other analgesics are ineffective and, for arthritis, a short course of corticosteroids if necessary.16 Brazilian guidelines published in 2020 recommend treating CHIK arthralgia/arthritis with analgesics and opioids and discourage the use of NSAIDs owing to the increased risk of bleeding or kidney damage.17 In the subacute phase, these new guidelines recommend corticosteroids for inflammatory arthritis (alone or in combination with common analgesics or weak opioids). After 4 weeks, in patients who show a good response, the corticosteroids should be slowly withdrawn.16 For the chronic phase, the guidelines recommend analgesics, opioids, NSAIDs, and corticosteroids. Only after failure of these drugs is a DMARD recommended, and HCQ is preferred. Methotrexate is recommended only for severe inflammatory joint disease (moderate or severe disease affecting more than five joints, with moderate to severe swelling and pain).17 In the review by Webb et al.,14 11 clinical management guidelines recommended MTX as first-line therapy.

There are concerns about the safety of MTX in virus-induced arthritis because of the potential of MTX, an immunomodulatory drug, promoting viral replication or adverse hepatic effects. However, a recent study led by Bedoui et al.18 found that MTX did not increase the ability of CHIKV to infect and replicate in primary human synovial fibroblasts. The authors recommended that MTX be used to treat CHIKA, as it does not critically affect the antiviral, proinflammatory, and bone tissue–remodeling responses of synovial cells. In addition, the safety of MTX has been demonstrated in many forms of inflammatory arthritis. Although some patients experience adverse events during MTX treatment, these adverse events are usually mild, and withdrawal from MTX for reasons of toxicity is less common than for most other DMARDs.19

In our patients, polyarthralgia/polyarthritis was the most common symptom reported. This finding is consistent with those of other reports.20–23 Nkoghe et al.20 reported a cohort of 270 patients, 230 of whom (71.5%) had arthritis affecting the ankles, 69.1% knees, 57.3% wrists, 32.9% hands, and 29% shoulders. Borgherini et al.21 evaluated 257 CHIKF patients and reported that 251 (96%) had polyarthralgia affecting the ankles in 100 (66.2%), knees in 92 (60.9%), metacarpophalangeal joints in 75 (49.6%), shoulders in 55 (36.4%), elbows in 48 (31.7%), and wrists in 44 (29.1%) patients. Thiberville et al.22 followed 54 patients and noted joint involvement as follows: metacarpophalangeal 40 (74.1%), wrists 39 (72.2%), interphalangeal 37 (68.5%), ankles 37 (68.5%), knees 33 (61.1%), shoulders 26 (48.1%), and elbows 14 (25.9%). In another large series of 690 cases, the joints involved were the wrists in 371 (54.1%), small joints of the hands in 321 (46.8%), ankles in 251 (36.6%), knees in 240 (35.0%), and elbows in 228 (33.2%).23

Blettery et al.24 analyzed 147 CHIKA patients with rheumatic manifestations at a mean (SD) of 7.5 (8.0) months after disease onset. Twenty-seven patients had chronic polyarthritis with a DAS28-ESR mean (SD) of 4.8 (1.5). Chang et al.25 measured DAS28-C-reactive protein (CRP) in patients with CHIKA and found a high disease activity DAS28-ESR mean (SD) of 4.5 (0.8). Watson et al.26 examined 40 CHIKA patients and found a median VAS pain score of 73 with interquartile range of 50 to 82. In another study, Tritsch et al.27 reported that among patients who had persistent joint pain after 20 months, the mean (SD) global pain score was 47 (20) (N = 123). Among participants reporting joint pain lasting 40 months, the overall mean pain score was 65 (20) (N = 67). Similarly, most of our patients reported chronic pain and had persistent moderate or severe disease activity as measured by DAS28-ESR.

Some of our patients may have improved spontaneously. Our study had some limitations. It is notable that the sample size was relatively small because of lost to follow-up patients, introducing an unavoidable attrition bias and a low absolute number of cases, which underpowered the statistical analyses we performed. Other limitations include the fact that it is a medical records review from a single practice with a short follow-up period of 4 weeks for the second study visit and a lack of data on optimal treatment time and treatment discontinuation. Finally, patients were assessed 5 months after treatment discontinuation, but documentation of TJC and SJC relied on self-reporting. Although this is considered a limitation, a recent meta-analysis showed a strong correlation between RA patient– and clinician-reported TJCs (0.78, 95% CI: 0.76–0.80) and a moderate correlation for SJCs (0.59, 95%: CI 0.54–0.63).28

CONCLUSION

Although CHIKA can be mild and self-limiting, in some patients, painful polyarthritis is present and unremitting from disease onset. We characterized the clinical features, duration, pain, and disease activity of patients with CHIKA. We treated a cohort of 133 consecutive Brazilian patients with MTX and/or leflunomide and dexamethasone and observed a significant improvement in disease activity and pain at 4 weeks. We demonstrated that CHIKA causes disabling pain that can be rapidly improved with treatment with MTX and/or leflunomide and corticosteroids. Despite an uncertain contribution to a specific treatment in CHIKA, reports of chronicity and destructive behavior similar to AR make this topic important for future studies.

REFERENCES

- 1. Weaver SC, Lecuit M, 2015. Chikungunya virus and the global spread of a mosquito-borne disease. N Engl J Med 372: 1231–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amaral JK, Schoen RT, 2018. Chikungunya in Brazil: rheumatologists on the front line. J Rheumatol 45: 1491–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benjamanukul S, Osiri M, Chansaenroj J, Chirathaworn C, Poovorawan Y, 2021. Rheumatic manifestations of chikungunya virus infection: prevalence, patterns, and enthesitis. PLoS One 16: e0249867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cardona-Ospina JA, Fernanda Urbano-Garzon S, Sebastian Hurtado-Zapata J, 2016. Prevalence of post-chikungunya infection chronic inflammatory arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 68: 1849–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rodriguez-Morales AJ. et al. , 2016. Post-chikungunya chronic inflammatory rheumatism: results from a retrospective follow-up study of 283 adult and child cases in La Virginia, Risaralda, Colombia. F1000 Res 5: 360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simon F. et al. , 2015. French guidelines for the management of chikungunya (acute and persistent presentations). Med Mal Infect 45: 243–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Amaral JK, Sutaria R, Schoen RT, 2018. Treatment of chronic chikungunya arthritis with methotrexate: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 70: 1501–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Amaral JK, Bingham CO, Schoen RT, 2020. Successful methotrexate treatment of chronic chikungunya arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol 26: 119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marques CDL. et al. , 2017. Recommendations of the Brazilian Society of Rheumatology for the diagnosis and treatment of chikungunya fever. Part 2 – treatment. Rev Bras Reumatol Engl 57 ( Suppl 2 ): 438–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ministry of Health of Brazil, Department of Health Surveillance , 2022. . Boletim Epidemiológico: Monitoring of Cases of Dengue and Chikungunya Fever until Epidemiological Week 47, 2022. Available at: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/boletins/epidemiologicos/edicoes/2022/boletim-epidemiologico-vol-53-no44/view. Accessed December 5, 2022.

- 11. Amaral JK, Bilsborrow JB, Schoen RT, 2019. Brief report: the disability of chronic chikungunya arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 38: 2011–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hjermstad MJ, Fayers RP, Haugen DF, Caraceni A, Hanks GW, Loge JH, Rainsinger R, Aass N, Kaasa S; European Palliative Care Research Collaborative , 2011. Studies comparing numerical rating scales, verbal rating scales, and visual analogue scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage 41: 1073–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wells G, Becker J-C, Teng J, Dougados M, Schiff M, Smolen J, Aletaha D, van Riel PLCM, 2009. Validation of the 28-joint disease activity score (DAS28) and European League Against Rheumatism response criteria based on C-reactive protein against disease progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and comparison with the DAS28 based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Ann Rheum Dis 68: 954–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Webb E. et al., 2022. An evaluation of global chikungunya clinical management guidelines: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine 54: 101672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Javelle E, Ribera A, Degasne I, Gaüzère BA, Marimoutou C, Simon F, 2015. Specific management of post-chikungunya rheumatic disorders: a retrospective study of 159 cases in Reunion Island from 2006–2012. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9: e0003603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization , 2008. Guidelines on Clinical Management of Chikungunya Fever. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/guidelines-on-clinical-management-of-chikungunya-fever. Accessed August 22, 2022.

- 17. Brito CAA. et al. , 2020. Update on the treatment of musculoskeletal manifestations in chikungunya fever: a guideline. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 53: e20190517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bedoui Y, Giry C, Jaffar-Bandjee MC, Selambarom J, Guiraud P, Gasque P, 2018. Immunomodulatory drug methotrexate used to treat patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatisms post-chikungunya does not impair the synovial antiviral and bone repair responses. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12: e0006634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Salliot C, van der Heijde D, 2009. Long-term safety of methotrexate monotherapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature research. Ann Rheum Dis 68: 1100–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nkoghe D, Kassa RF, Caron M, Grard G, Mombo I, Bikié B, Paupy C, Becquart P, Bisvigou U, Leroy EM, 2012. Clinical forms of chikungunya in Gabon, 2010. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6: e1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Borgherini G, Poubeau P, Staikowsky F, Lory M, Le Moullec N, Becquart JP, Wengling C, Michault A, Paganin F, 2017. Outbreak of chikungunya on Reunion Island: early clinical and laboratory features in 157 adult patients. Clin Infect Dis 44: 1401–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thiberville SD, Boisson V, Gaudart J, Simon F, Flahault A, de Lamballerie X, 2013. Chikungunya fever: a clinical and virological investigation of outpatients on Reunion Island, South-West Indian Ocean. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7: e2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rahman MM. et al. , 2019. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of an acute chikungunya outbreak in Bangladesh in 2017. Am J Trop Med Hyg 100: 405–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Blettery M, Lrunier L, Polomat K, Moinet F, Deligny C, Arfi S, Jean-Baptiste G, De Bandt M, 2016. Management of chronic post-chikungunya rheumatic disease: the Martinican experience. Arthritis Rheumatol 68: 2817–2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chang AY. et al. , 2018. Chikungunya arthritis mechanisms in the Americas: a cross-sectional analysis of chikungunya arthritis patients twenty-two months after infection demonstrating no detectable viral persistence in synovial fluid. Arthritis Rheumatol 70: 585–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Watson H, Nogueira-Hayd RL, Rodrigues-Moreno M, Naveca F, Calusi G, Suchowiecki K, Firestein GS, Simon G, Change AY, 2021. Tender and swollen joint counts are poorly associated with disability in chikungunya arthritis compared to rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Rep 11: 18578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tritsch SR. et al. , 2020. Chronic joint pain 3 years after chikungunya virus infection largely characterized by relapsing-remitting symptoms [published correction appears in J Rheumatol 2021 48:1350]. J Rheumatol 47: 1267–1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rampes S, Patel V, Bosworth A, Jacklin C, Nagra D, Yates M, Norton S, Galloway JB, 2021. Systematic review and metaanalysis of the reproducibility of patient self-reported joint counts in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 48: 1784–1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]