Abstract

Dental cements are widely used in the clinical routine, specifically for root canal sealing. Within this context, it is expected that these materials present antimicrobial activity, since it would help in the prevention of apical and periapical infections. The present study aimed to comparatively verify the antimicrobial activity of four dental cements against microorganisms that are routinely isolated from endodontic infections. Reference strains of Enterococcus faecalis, Candida albicans and Escherichia coli were submitted to the agar diffusion test and to modified direct contact test using four different sealers: an eugenol zinc oxide compound, an epoxy resin associated to calcium hydroxide and bismuth, a mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) and a bioceramics. Different E. coli, C. albicans and E. faecalis growth inhibition profiles were observed in the agar diffusion assay. In the direct contact test, the bioceramics presented a higher microbicide activity on all microorganisms tested herein. Dental cements have different antimicrobial activities, being that the bioceramics present the most consistent antimicrobial activity, and that the direct contact test presented more uniform results than the agar diffusion test. This study reveals the antimicrobial activities of different cements and allow dentists to decide which material to employ in their daily practice.

Keywords: Candida albicans, Endodontics cements, Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli

Introduction

The endodontic treatment aims to promote root canal disinfection and to eliminate microorganisms and their products, improving apical healing and preventing development of apical lesions [1–3]. Enterococcus faecalis [4], Candida albicans [5] and Escherichia coli [6] are frequently found in treatment-resistant cases. These microorganisms present the ability to invade dentinal tubules and withstand prolonged nutritional deprivation [7]. Therefore, root canal fillings are intended to ensure three-dimensional sealing and prevent reinfection [1, 8]. Hence, it is expected that endodontic sealers present antibacterial activity, aiming a better inhibition of bacterial growth and prevention of biofilm development [3, 9–11].

Several endodontic sealers have already been developed and are currently available for routine clinical use. These cements present different compositions and, in this way, can present a variation on its physicochemical characteristics and antimicrobial properties. The eugenol zinc oxide is used as a standard in many academic researches, and it induces the production of reactive oxygen species and acts on bacterial membrane proteins [12], being able to inhibit E. faecalis growth [4, 13–15]. The epoxy resin and its modifications, such as AH26 (association with calcium hydroxide and bismuth), are responsible for adapting the filling to the dentinal walls, present high adhesion power and significant antibacterial effects [15]. The mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) has been used for more than a decade as a cement, and its antibacterial activity is mainly based on its alkaline pH [11]. Recently, bioceramics are gaining more visibility, due to their ability to stimulate the osteoblastic activity and the mineralization of the dentin structure [16–19], associated to the prevention of E. faecalis growth and a complete sealing of the root canal structure [20].

Considering the diversity of sealers that are currently commercially available, this work had the objective to compare the antibacterial activity of four different cements. Two different techniques were used, and the results of these two assays were compared.

Material and methods

Microorganisms and sealers

It was used in this study reference strains of Enterococcus faecalis (ATCC 29,212), Candida albicans (FIOCRUZ 2508) and Escherichia coli (ATCC 25,922). These microorganisms were chosen since they are the most common ones isolated from infected root canals [21, 22]. Different sealers were evaluated herein: a eugenol zinc oxide compound (Dentsply Sirona, Rio de Janeiro—Brazil); an epoxy resin associated with calcium hydroxide and bismuth (Sealer26, Dentsply Sirona, Rio de Janeiro—Brazil); a MTA (Angelus, Londrina, Brazil) and a bioceramics (BioRoot RCS; Septodont, Sait-Maur-de-fosses, France). They were chosen with the objective to include different chemical compounds that are commercially available as sealers, and because they are widely used by dentistry professionals.

Agar diffusion test (ADT)

The ADT has already been described in the literature as a methodology that can identify the inhibition of microbial growth through the diffusion of cements in a semisolid medium [23]. Briefly, solutions containing the microorganisms were seeded in culture Petri dishes filled with Mueller–Hinton agar medium (Scharlau Chemie, Barcelona, Spain). Then, four wells were made at the medium using a Pasteur pipette. Freshly mixed sealers, prepared according to the manufacturers’ instructions, were then immediately transferred to the wells. After an overnight incubation at 37 °C, the inhibition halos were measured (in millimeters). Additionally, positive control plates were prepared with the microorganisms and no root canal sealers. In each experiment, triplicates were made for each microorganism/sealer combination, and the experiment was repeated three times.

Modified direct contact test (DCT)

This experiment was conducted as previously described by Hui Zhang et al. (2009) and expresses the microbicidal activity of each sealer. The microorganisms were grown overnight at 37 °C for 24 h. The inoculums were then prepared according to the 0.5 Mc Farland scale (1.5 × 108 CFU/mL). The cements used in the test were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions and applied with a dental insertion spatula in the side of each well of a 96-well sterile culture plate. After different drying periods (20 min, simulating a recently applied sealer; and 72 h, representing a more consolidated sealer) into an oven, under a humid atmosphere and at 37 °C, 10 μL of each microbial suspension was applied to the surface of each cement and incubated for 60 min; all these procedures were made with the plates maintained in a vertical position; 240 µL of Mueller–Hinton broth (Scharlau Chemie) or Sabouraud Dextrose broth (Titan Biotech, Rajasthan, India), for the bacteria or the fungus, respectively, was added to the plates, further collected, and serial dilutions (1:10, 1:100 and 1:1000) were performed in the respective broths. These solutions were plated in Mueller–Hinton agar (Scharlau Chemie) or SDA (Sabouraud Dextrose Agar, Titan Biotech), respectively, and after a 48-h incubation at 37 °C in an incubator with a 5% CO2 supplemented atmosphere, the colony forming units (CFUs) were counted. In addition, positive and negative controls were prepared. The experiments were carried three times, each one in triplicates [24].

Results

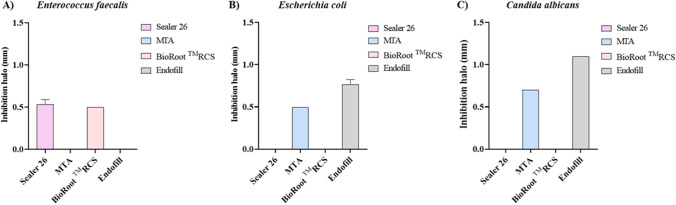

The results found using the ADT methodology are shown in Fig. 1. The epoxy resin and the bioceramics inhibited the E. faecalis growth. C. albicans was inhibited by the zinc oxide eugenol and the MTA, while the growth of E. coli was inhibited by these same sealers.

Fig. 1.

Growth inhibition of (A) E. faecalis, (B) E. coli and (C) C. albicans by different endodontic sealers. These results were achieved using the agar diffusion test (ADT) and are expressed as means of the inhibition halos from three independent experiments. Standard deviation bars are shown above the columns

Considering the microbicidal properties of the sealers, it was seen that the epoxy resin was able to kill the three microorganisms, but only after a 20-min drying period; when the resin was left to dry for 72 h, it was observed that the sealer did not present a microbicide activity against E. faecalis and E. coli. The MTA presented the less significant results, being only microbicide to C. albicans after a 20-min drying period. The bioceramics were able to completely kill E. coli, E. faecalis and C. albicans both after a 20-min and 72-h drying period. Regarding the zinc oxide eugenol, it presented a significant bactericide activity against E. faecalis and E. coli, being that it was only possible to see the growth of only one colony-forming unit of C. albicans when it was incubated with this sealer after a 72-h drying period (Table 1).

Table 1.

Microbicide activity of different endodontic sealers. These results were achieved through the modified direct contact test (DCT), made after a 20-min or 72-h sealer drying period. The results are expressed as means of the number of colony-forming units (CFUs) found in three different experiments. The symbols “-” stands for no bacterial growth

| Enterococcus faecalis | Escherichia coli | Candida albicans | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 min | 72 h | 20 min | 72 h | 20 min | 72 h | |

| Sealer 26 | ⁃ | 3 | ⁃ | 33 | ⁃ | ⁃ |

| MTA | 41 | 41 | 41 | 41 | ⁃ | 41 |

| Bioroot RCS | ⁃ | ⁃ | ⁃ | ⁃ | ⁃ | ⁃ |

| Endofill | ⁃ | ⁃ | ⁃ | ⁃ | ⁃ | 1 |

Discussion

The complete elimination of microorganisms and the prevention of root canal system reinfections are situations that cannot be currently achieved, even with debridement, shaping and irrigation of the root canals with antimicrobial agents [25–27]. Therefore, the use of root filling materials that present antimicrobial activity can help in achieving this goal [9, 26, 27], and may be the cause of the success rate of root canal treatment when completed in just one or more appointments [28]. The most important requirements for sealers are biocompatibility, excellent seal properties, adequate adhesion and antimicrobial activities [24, 29]. Any microorganism that remains in the root canal has the potential to cause treatment failures [5]. In the present study, E. faecalis, E. coli and C. albicans, were tested, which are endodontic pathogens that can be associated with persistent endodontic diseases. These microorganisms can produce biofilm, and it is a situation that can lead to a more difficult treatment of microbial oral diseases, since the biofilm is a structure that protects the microbes from the action of antibiotics and antifungals [30]. It was already described that higher concentrations of antifungals are necessary for the inhibition of C. albicans in biofilms [31].

Inhibition tests, such as the ADT, were widely used to assess the antimicrobial activity of endodontic sealers [32, 33]. However, the limitations of these methods are currently well-recognized, since the results obtained through these assays are not likely to reflect the true antimicrobial potential of the various sealers or disinfecting agents [34]. Direct contact tests (DCTs) circumvent many of the problems of the ADT [34, 35] in the evaluation of the antimicrobial effect of endodontic sealers and root-end filling materials. DCTs are quantitative and reproducible assays that allow testing of insoluble materials, and can be used to assess the microbicide activity, demonstrating more reliable results than the agar diffusion test [25, 35].

The zinc oxide eugenol has been widely used in endodontics and is considered a standard sealer in many academic works. In previous studies, it has already exhibited a significant antibacterial activity [25]. This cement has already shown the capacity to inhibit E. faecalis [25] in a similar way that was detected in our DCT results. In addition, we were able to observe a significant microbicide activity on E. coli. However, the ADT did not show any inhibition of the E. faecalis growth, a situation that can be linked to the capacity of the eugenol to diffuse on the agar support.

It was already reported that the antimicrobial properties of MTA sealers can be affected by the exposition time [21]. These authors described that the activity of sealers in the direct technique was higher than the indirect technique, a situation that may be related to the fact that the sealer needs a longer time to exert its effect on microorganisms in the indirect technique [21]. Our study was able to observe that MTA has a bacteriostatic/fungistatic effect on E. coli and C. albicans but did not show any bactericide/fungicide activity on the three microorganisms studied herein. MTA has its antimicrobial activity based solely on its pH, and this situation can explain our results, since several oral pathogens are only susceptible to a pH above 12 [5].

Bioceramics have been considered promising materials because of their excellent biocompatibility and physicochemical properties, as well as due to its hard tissue repair properties [16, 36, 37]. These sealers have lower cytotoxicity and genotoxicity than conventional sealers, have already presented a similar antibacterial effect against E. faecalis [38] and induced lower postoperative pain when compared to the epoxy resin [39]. In our study, the bioceramics, as expected, did not show significant results at the ADT, and this situation can be a consequence of the fact that this sealer infiltration pattern in the agar substrate frequently hides the inhibition zone [16]. However, the bioceramics exhibited promising results at the DCT, being able to kill all the microorganisms studied herein.

The Sealer 26 is an epoxy resin that contains calcium hydroxide [40], urotropine, titanic dioxide and bismuth trioxide [41]. In this study, this sealer showed an antifungal activity similar to the eugenol zinc oxide, but its antibacterial effect decreased after 72 h, both for E. faecalis and E. coli. It was already observed an decrease in the antimicrobial effect of these cements during drying periods (from 1 to 7 days), and it is believed that the non-polymerization of some components (amines and epoxy) favors an immediate antimicrobial effect associated with a further reduction on this activity [42, 43].

In conclusion, the modified DCT was able to generate more reliable and consistent results. Among all cements tested herein, the bioceramics demonstrated better antibacterial and antifungal properties, even over 72-h drying period.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Francisca Soares (LABIMUNO-UFBA) for technical assistance.

Author contribution

ARS, CFA and LEL conducted the experimental work. ARS and SEA wrote the manuscript. DBA and RDP critically reviewed the manuscript. RM and RDP supervised the project. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundação de Apoio à Pesquisa e Extensão (FAPEX), through continuous resources obtained from extension projects. RDP is a Technical Development fellow from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPQ—Proc. 310058/2022-8).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, RDP.

Declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nair PN. On the causes of persistent apical periodontitis: a review. Int Endod J. 2006;39(4):249–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agrawal V, Kapoor S, Agrawal I. Critical review on eliminating endodontic dental infections using herbal products. J Diet Suppl. 2017;14(2):229–240. doi: 10.1080/19390211.2016.1207004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saha S, Dhinsa G, Ghoshal U, Afzal Hussain ANF, Nag S, Garg A. Influence of plant extracts mixed with endodontic sealers on the growth of oral pathogens in root canal: an in vitro study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2019;37(1):39–45. doi: 10.4103/JISPPD.JISPPD_66_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wainstein M, Morgental RD, Waltrick SB, Oliveira SD, Vier-pelisser FV, Figueiredo JA, Steier L, Tavares CO, Scarparo RK. In vitro antibacterial activity of a silicone-based endodontic sealer and two conventional sealers. Braz Oral Res. 2016;30:S1806–83242016000100216. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2016.vol30.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yasuda Y, Kamaguchi A, Saito T. In vitro evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of a new resin-based endodontic sealer against endodontic pathogens. J Oral Sci. 2008;50(3):309–313. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.50.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang Y, Li X, Mandal P, Wu Y, Liu L, Gui H, Liu J. The in vitro antimicrobial activities of four endodontic sealers. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19(1):118. doi: 10.1186/s12903-019-0817-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stuart CH, Schwartz SA, Beeson TJ, Owatz CB. Enterococcus faecalis: its role in root canal treatment failure and current concepts in retreatment. J Endod. 2006;32(2):93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byström A, Sundqvist G. Bacteriologic evaluation of the efficacy of mechanical root canal instrumentation in endodontic therapy. Scand J Dent Res. 1981;89(4):321–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1981.tb01689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komabayashi T, Colmenar D, Cvach N, Bhat A, Primus C, Imai Y. Comprehensive review of current endodontic sealers. Dent Mater J. 2020;39(5):703–720. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2019-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh G, Elshamy FM, Homeida HE, Boreak N, Gupta I. An in vitro comparison of antimicrobial activity of three endodontic sealers with different composition. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2016;17(7):553–556. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faria-júnior NB, Tanomaru-filho M, Berbert FL, Guerreiro-tanomaru JM. Antibiofilm activity, pH and solubility of endodontic sealers. Int Endod J. 2013;46(8):755–762. doi: 10.1111/iej.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banoee M, Seif S, Nazari ZE, Jafari-fesharaki P, Shahverdi HR, Moballegh A, Moghaddam KM, Shahverdi AR. ZnO nanoparticles enhanced antibacterial activity of ciprofloxacin against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2010;93(2):557–561. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poggio C, Lombardini M, Colombo M, Dagna A, Saino E, Arciola CR, Visai L. Antibacterial effects of six endodontic sealers. Int J Artif Organs. 2011;34(9):908–913. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barbosa VM, Pitondo-silva A, Oliveira silva M, Matorano AS, Rizzi-maia CC, Silva-souza TC, Castro-raucci LMS, Neto WR. Antibacterial activity of a new ready to use calcium silicate-based sealer. Braz Dent J. 2020;31(6):611–616. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440202003870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batista RF, Hidalgo MM, Hernandes L, Consolaro A, Velloso TR, Cuman RK, Caparroz-assef SM, Bersani-Amado CA. Microscopic analysis of subcutaneous reactions to endodontic sealer implants in rats. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;81(1):171–177. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kharouf N, Arntz Y, Eid A, Zghal J, Sauro S, Haikel Y, Mancino D. Physicochemical and antibacterial properties of novel, premixed calcium silicate-based sealer compared to powder-liquid bioceramic sealer. J Clin Med. 2020;9(10):3096. doi: 10.3390/jcm9103096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siboni F, Taddei P, Zamparini F, Prati C, Gandolfi MG. Properties of BioRoot RCS, a tricalcium silicate endodontic sealer modified with povidone and polycarboxylate. Int Endod J. 2017;50(Suppl 2):e120–e136. doi: 10.1111/iej.12856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dimitrova-nakov S, Uzunoglu E, Ardila-osorio H, Baudry A, Richard G, Kellermann O, Goldberg M. In vitro bioactivity of Bioroot™ RCS, via A4 mouse pulpal stem cells. Dent Mater. 2015;31(11):1290–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2015.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prüllage RK, Urban K, Schäfer E, Dammaschke T. Material properties of a tricalcium silicate-containing, a mineral trioxide aggregate-containing, and an epoxy resin-based root canal sealer. J Endod. 2016;42(12):1784–1788. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arias-moliz MT, Camilleri J. The effect of the final irrigant on the antimicrobial activity of root canal sealers. J Dent. 2016;52:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jafari F, SamadiKafil H, Jafari S, Aghazadeh M, Momeni T. Antibacterial activity of MTA Fillapex and AH 26 root canal sealers at different time intervals. Iran Endod J. 2016;11(3):192–197. doi: 10.7508/iej.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gajan EB, Aghazadeh M, Abashov R, Salem Milani A, Moosavi Z. Microbial flora of root canals of pulpally-infected teeth: Enterococcus faecalis a prevalent species. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2009;3(1):24–27. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2009.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farmakis ET, Kontakiotis EG, Tseleni-kotsovili A, Tsatsas VG. Comparative in vitro antibacterial activity of six root canal sealers against Enterococcus faecalis and Proteus vulgaris. J Investig Clin Dent. 2012;3(4):271–275. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1626.2012.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H, Ya Shen N, Ruse D, Haapasalo M. Antibacterial activity of endodontic sealers by modified direct contact test against Enterococcus faecalis. J Endod. 2009;35(7):1051–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anumula L, Kumar S, Kumar VS, Sekhar C, Krishna M, Pathapati RM, VenkataSarath P, Vadaganadam Y, Manne RK, Mudlapudi S. An assessment of antibacterial activity of four endodontic sealers on Enterococcus faecalis by a direct contact test: an in vitro Study. ISRN Dent. 2012;2012:989781. doi: 10.5402/2012/989781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beyth N, KeslerShvero D, Zaltsman N, Houri-Haddad Y, Abramovitz I, Davidi MP, Weiss EI. Rapid kill-novel endodontic sealer and Enterococcus faecalis. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e78586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prado M, Simao RA, Gomes BP. A microleakage study of gutta-percha/AH Plus and Resilon/Real self-etch systems after different irrigation protocols. J Appl Oral Sci. 2014;22(3):174–179. doi: 10.1590/1678-775720130174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zandi H, Rodrigues RC, Kristoffersen AK, Enersen M, Mdala I, Ørstavik D, Rôças IN, Siqueira JF., Jr Antibacterial effectiveness of 2 root canal irrigants in root-filled teeth with infection: a randomized clinical trial. J Endod. 2016;42(9):1307–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meng Y, Zhang D, Jia X, Xiao K, Lin X, Yang Y, Xu D, Wang Q. Antimicrobial activity of nano-magnesium hydroxide against oral bacteria and application in root canal sealer. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e922920. doi: 10.12659/MSM.922920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma D, Misba L, Khan AU. Antibiotics versus biofilm: an emerging battleground in microbial communities. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8:76. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0533-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sokolonski AR, Fonseca MS, Machado BAS, Deegan KR, Araújo RPC, Umza-guez MA, Meyer R, Portela RW. Activity of antifungal drugs and Brazilian red and green propolis extracted with different methodologies against oral isolates of Candida spp. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2021;21(1):286. doi: 10.1186/s12906-021-03445-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sipert CR, Hussne RP, Nishiyama CK, Torres SA. In vitro antimicrobial activity of Fill Canal, Sealapex, Mineral Trioxide Aggregate, Portland cement and EndoRez. Int Endod J. 2005;38(8):539–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2005.00984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siqueira JF, Jr, Favieri A, Gahyva SM, Moraes SR, Lima KC, Lopes HP. Antimicrobial activity and flow rate of newer and established root canal sealers. J Endod. 2000;26(5):274–277. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200005000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heyder M, Kranz S, Völpel A, Pfister W, Watts DC, Jandt KD, Sigusch BW. Antibacterial effect of different root canal sealers on three bacterial species. Dent Mater. 2013;29(5):542–549. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiss EI, Shalhav M, Fuss Z. Assessment of antibacterial activity of endodontic sealers by a direct contact test. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1996;12(4):179–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1996.tb00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raghavendra SS, Jadhav GR, Gathani KM, Kotadia P. Bioceramics in endodontics—a review. J Istanb Univ Fac Dent. 2017;51(Suppl 1):S128–S137. doi: 10.17096/jiufd.63659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Candeiro GT, Correia FC, Duarte MA, Ribeiro-Siqueira DC, Gavini G. Evaluation of radiopacity, pH, release of calcium ions, and flow of a bioceramic root canal sealer. J Endod. 2012;38(6):842–845. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Candeiro GTM, Moura-netto C, D'almeida-couto RS, Azambuja-Júnior N, Marques MM, Cai S, Gavini G. Cytotoxicity, genotoxicity and antibacterial effectiveness of a bioceramic endodontic sealer. Int Endod J. 2016;49(9):858–864. doi: 10.1111/iej.12523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khandelwal A, Jerry J, Kavalipurapu-venkata T, Ajitha P. Comparative evaluation of postoperative pain and periapical healing after root canal treatment using three different base endodontic sealers—a randomized control clinical trial. J Clin Exp Dent. 2022;14(2):e144–e152. doi: 10.4317/jced.59034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cunha SA, Soares CJ, Rosatto CMP, Vieira JVSM, Pereira RADS, Soares PBF, Leles CR, Moura CCG. Effect of endodontic sealer in young molars treated by undergraduate students—a randomized clinical trial. Braz Dent J. 2020;31(6):589–597. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440202003258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacobsen EL, BeGole EA, Vitkus DD, Daniel JC. An evaluation of two newly formulated calcium hydroxide cements: a leakage study. J Endod. 1987;13(4):164–169. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(87)80134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Özcan E, Eldeniz AU, Arı H. Bacterial killing by several root filling materials and methods in an ex vivo infected root canal model. Int Endod J. 2011;44(12):1102–1109. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang TH, Yang JJ, Li H, Kao CT. The biocompatibility evaluation of epoxy resin-based root canal sealers in vitro. Biomaterials. 2002;23(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, RDP.