Abstract

Delay diagnosis of spondyloarthritis (SpA) is associated with poor functional ability and quality of life. Uveitis is the most frequent extraarticular manifestation in SpA, and its prevalence increases with longer disease duration. This study examines the effect of uveitis on the disease activity and functional outcome of undiagnosed SpA. We reviewed published and unpublished studies. Data were pooled using the random-effects model; pooled means, and mean differences (MDs) were calculated. In the included 14 studies, disease activity, functional index, and inflammatory markers were measured in 2581 patients with SpA with uveitis and 13,972 without. The pooled mean delay in diagnosis of SpA with uveitis (6.08 years; 95% CI 4.77 to 7.38) was longer than those without (5.41 years; 95% CI 3.94 to 6.89). The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) score was the highest for a delay of 2–5 years (5.60, 95% CI 5.47 to 5.73) and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI) score was the lowest for a delay of < 2 years (2.92, 95% CI 2.48 to 3.37) and gradually increased to delay of > 10 years (4.17, 95% CI 2.93 to 5.41). Patients with SpA with uveitis had higher trend of Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS)-CRP and BASDAI. The delay to diagnosis was longer in SpA with uveitis, and disease activity was often higher than those without uveitis. Early diagnosis of SpA with timely initiation of an appropriate management plan may reduce the adverse effects of the disease and improve functional ability.

Subject terms: Immunology, Rheumatology

Introduction

Spondyloarthritis (SpA) is a chronic inflammatory disease that predominantly manifests in the spine with an insidious onset involving deep, dull pain in the lower back. SpA involves spinal and extraspinal signs and symptoms1. For clinical purposes, five disease subtypes of SpA are recognized: ankylosing spondylitis (AS), psoriatic spondyloarthritis (PsA), reactive arthritis, SpA associated with inflammatory bowel disease, and undifferentiated SpA2. Moreover, SpA can result in peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and other extraarticular manifestations (EAMs), with uveitis being the most commonly (observed in 25–30% of patients)3,4.

The diagnosis of SpA is often considerably delayed, and early diagnosis and intervention can slow down the development and progression of structural changes4. The pathological basis for SpA-related inflammation is recurrent mechanical stress triggering the tissue microdamage and repair processes that occur exactly at the same target sites such as the anterior uveal tract, aortic root and valve, lung apex, and enthesis organ structures5. Several studies have examined the prevalence of SpA with uveitis, and a longer disease duration and a higher proportion of human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27) were noted3,4,6–10. Delay of diagnosis is longer in SpA than in many other rheumatic diseases11. Prolonged delay was associated with poor outcomes including functional impairment and decreased quality of life11. Uveitis may be diagnosed before SpA or even before the occurrence of SpA symptoms12. As the most common EAM of SpA, uveitis may be the earliest or first symptom of SpA12 and thus may provide an opportunity for early SpA recognition. The Dublin Uveitis Evaluation Tool (DUET) assessment algorithm can aid in the early diagnosis of SpA in patients with uveitis, boasting a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 98%13. However, studies examining the effect of uveitis on the disease activity and functional outcome of SpA have reported inconsistent results6,10,14,15.

In clinical practice, the functional ability of patients with SpA is evaluated using the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI). Moreover, disease activity is quantified using two evaluation tools, namely the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) and Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS)16. The BASDAI contains only subjective clinical items, whereas the ASDAS contains both subjective clinical items and objective laboratory measures including the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and the C-reactive protein (CRP) level1.

Due to inconclusive emerging data regarding the disease activity and functional ability of patients with SpA with and without uveitis7,9,15,17–21, this study aimed to provide further insight by conducting a meta-analysis of existing studies. Specifically, the study examined the disease activity and functional outcome of SpA, while also analyzing differences between patients with SpA with and without uveitis.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

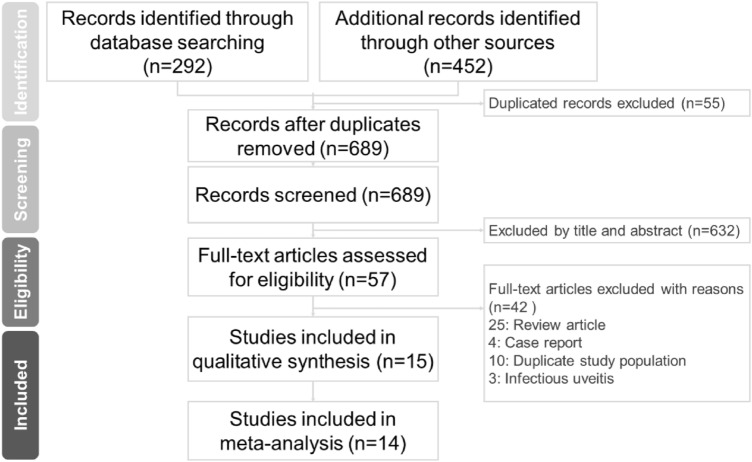

In the present study, we identified 689 articles from the online databases, among which 632 irrelevant articles were excluded. The remaining 57 articles were assessed for eligibility. Finally, 11 articles6–10,14,15,17–19,21 and 3 conference proceedings20,22,23 including 16,553 patients with SpA were included in the meta-analysis. The PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1) for studies retrieved through the electronic search and the selection process for study inclusion. The quality of the included studies was assessed using the RoBANS tool24 (Supplementary Fig. S1). In particular, the studies included 2581 patients with SpA with uveitis and 13,972 patients with SpA without uveitis. Table 1 lists the detailed characteristics of each study. Among the included studies, three were conducted in Asian populations, including two studies in China9,10 and one study in Taiwan17. Another 11 studies examined Caucasian populations from Europe, Latin America, and Turkey6–8,14,15,18–23 (Table 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for studies retrieved through the electronic search and the selection processes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Characteristics | Criteria | Patient (n)* | % male | Delay (y)* | Duration (y)* | HLA-B27 (+) %* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen 200717 | Taiwan, cross-sectional, AS | NY | 23/123 | 70.5 | 9.6/8.7 | 9.7/8.7 | 100/87 |

| Wendling 20126 | French, cohort, SPA | ESSG | 60/648 | 46.3 | 1.9/1.6 | NA | 63.3/57.1 |

| Gehlen 201218 | Brazil, cross- sectional, SPA | ESSG | 22/80 | 58.8 | 17.9/13.1 | NA | 66.6/69.0 |

| Sampaio-Barros 201319 | RESPONDIA, cohort, SPA | ESSG | 372/1640 | NA | 7.9/5.9 | NA | 72.1/60.6 |

| Berg 20147 | Norway, cross-sectional, AS | NY | 84/75 | 61.6 | NA | 26.8/21.4 | 75/68 |

| Diss 201420 | UK, cohort, SPA, AS, PsA | ESSG, NY, CASPAR | 24/43 | 37.5 | NA | 15.5/11.3 | 100/100 |

| Costa 201521 | Brazil, cohort, SPA | ESSG | 285/1207 | 72.3 | NA | NA | NA |

| Lian 201510 | China, cohort, SPA | ASAS | 182/854 | 87.7 | NA | 5.1/5.7 | 91.8/94.0 |

| Essers 201514 | OASIS, cohort, AS | NY | 39/177 | 71.3 | NA | 25.9/19.3 | 89.7/83.1 |

| Przepiera-Bedzak 20168 | Poland, cohort AS, PsA, SAPHO | NY, CASPAR, Kahn | 35/252 | 54.7 | NA | 11.3/5.3 | 94.4/47.1 |

| Kasifoglu 201822 | Turkey, cohort, SPA | NA | 269/2359 | 56.8 | 3.0/2.0 | 10.7/6.7 | 69.2/49.5 |

| Bilge 201923 | Turkey, cohort, SPA | NA | 491/4066 | 56.1 | 3.1/2.0 | 11.2/7.4 | 70.5/49.3 |

| Redeker 202015 | Germany, cohort, SPA | NA | 463/1266 | 53.8 | 5.6/5.6 | 29.8/23.5 | 90.4/84.6 |

| Man 20219 | China, cohort, SPA | NY | 232/1182 | NA | 9.9/7.6 | 9.9/7.8 | 87.8/83.3 |

Delay delay time of diagnosis, NA not available, NY 1984 modified New York criteria for ankylosing spondylitis, ESSG European Spondylarthropathy Study Group criteria for SPA, ASAS Assessment of Spondylarthritis International Society classification Criteria for SPA, CASPAR Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis, Kahn Classification Criteria for SAPHO syndrome, AS Ankylosing Spondylitis, SPA Spondylarthritis, PsA Psoriatic Arthritis, SAPHO syndrome synovitis acne pustulosis hyperostosis osteitis syndrome.

*Uveitis (+)/Uveitis (−).

Eleven studies presented BASDAI and BASFI results6,7,10,14,15,17–20,22,23, whereas two studies examined only the BASDAI in the patient population8,21. Five studies reported ASDAS results with ESR and CRP levels6–8,10,14, and one study examined the ASDAS only with CRP9. Three studies19,22,23 reported ESR and CRP levels without evaluating the ASDAS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical data in spondylarthritis patients with and without uveitis of the Included studies.

| Study | BASDAI | BASFI | ASDAS-CRP | CRP | ESR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uveitis | Uveitis | Uveitis | Uveitis | Uveitis | ||||||

| + yes | − no | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | |

| Chen 200717 | 4.9 (2.4) | 3.9 (2.0) | 4.2 (2.9) | 2.8 (2.4) | ||||||

| Wendling 20126 | 4.3 (2.1) | 4.5 (2.0) | 2.6 (2.2) | 3.1 (2.3) | 2.6 (1.0) | 2.5 (1.0) | 9.2 (12.2) | 9.0 (14.6) | 11.8 (13.0) | 14.0 (15.1) |

| Gehlen 201218 | 4.4 (2.4) | 3.3 (2.5) | 3.4 (3.3) | 4.7 (3.0) | ||||||

| Sampaio-Barros 201319 | 4.3 (2.4) | 4.3 (4.5) | 4.5 (2.9) | 4.2 (2.9) | 11.4 (18.3)) | 8.0 (14.5) | 25.3 (21.2) | 24.0 (19.8)) | ||

| Berg 20147 | 4.0 (2.0) | 3.5 (1.7) | 2.7 (2.2) | 1.7 (1.7) | 2.4 (1.0) | 2.2 (0.9) | 5.0 (5.2) | 5.0 (7.4) | 17.0 (14.8) | 17.0 (16.3) |

| Diss 201420 | 5.9 (0.4) | 5.8 (0.3) | 4.5 (0.6) | 4.5 (0.4) | ||||||

| Costa 201521 | 4.2 (2.5) | 4.2 (2.6) | ||||||||

| Lian 201510 | 6.6 (2.8) | 5.9 (3.1) | 5.7 (2.6) | 6.5 (3.7) | 2.4 (0.6) | 2.2 (0.5) | 38.4 (17.9) | 40.3 (19.3) | 78.6 (24.5) | 92.3 (33.1) |

| 2.5 (0.7)* | 2.8 (0.9)* | |||||||||

| Essers 201514 | 3.4 (2) | 3.5 (2.2) | 3.3 (2.3) | 3.4 (2.7) | 2.7 (0.8) | 2.7 (1.1) | 15.4 (15.1) | 18.6 (26.2) | 11.7 (7.9) | 15.3 (17.0) |

| Przepiera-Bedzak 20168 | 5.8 (2.8) | 3.9 (2.7) | 2.8 (0.9)* | 2.4 (0.9)* | 11.4 (13.7) | 6.1 (7.0) | 18.0 (22.2) | 14.7 (13.7) | ||

| Kasifoglu 201822 | 5.6 (2.2) | 5.7 (2.1) | 3.6 (2.4) | 4.3 (2.7) | 17.9 (20.7) | 14.8 (17.0) | 29 (27.4) | 24.7 (21.5) | ||

| Bilge 201923 | 5.3 (2.3) | 5.6 (2.1) | 3.6 (2.4) | 4.3 (2.7) | 17.5 (21.4) | 14.7 (17.0) | 27.7 (26.0) | 23.3 (20.7) | ||

| Redeker 202015 | 4.4 (0.1) | 4.5 (0.1) | 4.2 (0.1) | 4.0 (0.1) | ||||||

| Man 20219 | 2.2 (1.0) | 2.0 (1.0) | ||||||||

Values are shown as mean (SD).

BASDAI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, BASFI Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index, ASDAS Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score, CRP C-reactive protein, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

*ASDAS-ESR.

Statistical pooling of outcomes and meta-analysis

The pooled mean values of the BASDAI and BASFI for delay in the diagnosis (the time from the onset of symptoms to the diagnosis) of SpA (including with and without uveitis patients) were grouped into the following periods: ≤ 2, 2–5, 5–10, and > 10 years. The pooled mean values of the BASDAI and BASFI were 4.46 (95% CI 4.32 to 4.61) and 2.92 (95% CI 2.48 to 3.37), respectively, for ≤ 2 years; 5.60 (95% CI 5.47 to 5.73) and 3.98 (95% CI 3.67 to 4.28), respectively, for 2–5 years; 4.40 (95% CI 4.32 to 4.49) and 4.06 (95% CI 3.91 to 4.20), respectively, for 5–10 years; and 3.74 (95% CI 2.63 to 4.85) and 4.17 (95% CI 2.93 to 5.41), respectively, for > 10 years (Table 3).

Table 3.

The pooled mean and mean difference of clinical data in spondyloarthritis patients with and without uveitis of the included studies.

| Subgroup | Uveitis (+) | Uveitis (–) | Mean difference | 95% CI | p value (I2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled mean | 95% CI | Pooled mean | 95% CI | ||||

| Delay diagnosis (y) | 6.08 | 4.77 to 7.38 | 5.41 | 3.94 to 6.89 | 1.04 | 0.28 to 1.80 | 0.008 (83%) |

| ASDAS | 2.47 | 2.31 to 2.64 | 2.32 | 2.15 to 2.50 | 0.18 | 0.11 to 0.25 | < 0.001 (0%) |

| BASDAI | 4.87 | 4.41 to 5.32 | 4.53 | 4.11 to 4.96 | 0.11 | − 0.06 to 0.28 | 0.21 (76%) |

| BASFI | 3.89 | 3.53 to 4.25 | 3.97 | 3.65 to 4.28 | − 0.12 | − 0.46 to 0.21 | 0.47 (92%) |

| CRP (mg/L) | 15.78 | 8.38 to 23.18 | 14.53 | 8.69 to 20.38 | 1.48 | − 0.17 to 3.14 | 0.08 (64%) |

| ESR (mm/h) | 28.19 | 7.64 to 48.75 | 28.16 | 17.91 to 38.42 | − 0.80 | − 4.62 to 3.03 | 0.68 (90%) |

| ASDAS-CRP | 2.42 | 2.26 to 2.59 | 2.31 | 2.11 to 2.51 | 0.17 | 0.10 to 0.24 | < 0.001 (0%) |

| ASDAS-ESR | 2.76 | 2.47 to 3.05 | 2.37 | 2.26 to 2.48 | 0.03 | − 0.65 to 0.72 | 0.92 (94%) |

| Subgroup | BASDAI | BASFI | Study number | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled mean | 95% CI | Pooled mean | 95% CI | ||||

| ≤ 2 years | 4.46 | 4.32 to 4.61 | 2.92 | 2.48 to 3.37 | 1 (6) | ||

| > 2 years, ≤ 5 years | 5.60 | 5.47 to 5.73 | 3.98 | 3.67 to 4.28 | 2 (22, 23) | ||

| > 5 years, ≤ 10 years | 4.40 | 4.32 to 4.49 | 4.06 | 3.91 to 4.20 | 3 (15, 17, 19) | ||

| > 10 years | 3.74 | 2.63 to 4.85 | 4.17 | 2.93 to 5.41 | 1 (18) | ||

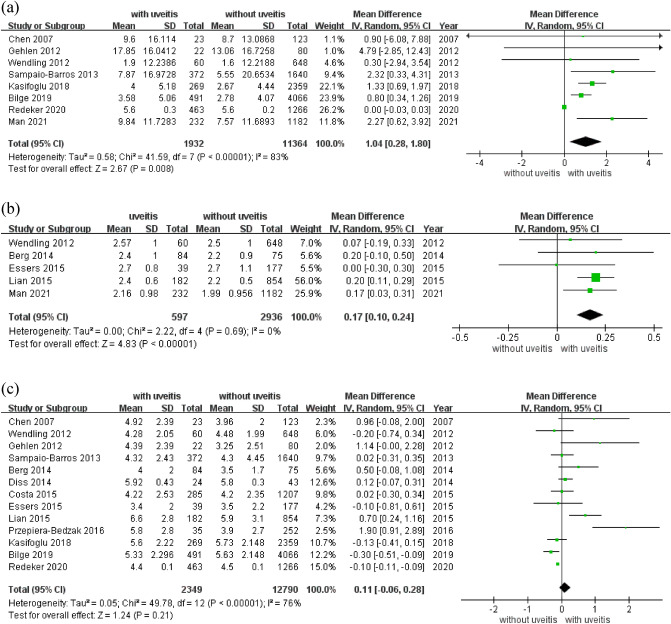

The pooled mean values of delay in the diagnosis of SpA with and without uveitis were 6.08 (95% CI 4.77 to 7.38) years and 5.41 (95% CI 3.94 to 6.89) years, respectively. For continuous variables, mean differences (MDs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. The delay in diagnosis was significantly longer in patients with uveitis than in those without uveitis (MD 1.04; 95% CI 0.28 to 1.80, p = 0.008; Table 3; Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the mean difference of delay diagnosis, ASDAS-CRP, and BASDAI in patients of spondyloarthritis with and without uveitis. (a) delay diagnosis, (b) ASDAS-CRP, (c) BASDAI.

The pooled mean ASDASs were 2.47 (95% CI 2.31 to 2.64) and 2.32 (95% CI 2.15 to 2.50) for patients with and without uveitis, respectively (Table 3; Supplementary Fig. S2). The disease activity was significantly higher in patients with uveitis than in those without uveitis (MD 0.18; 95% CI 0.11 to 0.25, p < 0.001, I2 = 0%; Table 3; Supplementary Fig. S3). Six6–10, 13 of the 14 studies examined the ASDAS, among which four examined the ASDAS-CRP, one10 evaluated both ASDAS-CRP and ASDAS-ESR, and one8 examined only ASDAS-ESR. The ASDAS-CRP score was significantly higher in patients with SpA with uveitis (MD 0.17; 95% CI 0.10 to 0.24, p < 0.001, I2 = 0%; Table 3; Fig. 2). No significant difference in the ASDAS-ESR score was observed between patients with SpA with and without uveitis (MD, 0.03; 95% CI − 0.65 to 0.72, p = 0.92; Table 3; Supplementary Fig. S3).

The pooled mean BASDAI scores were 4.87 (95% CI 4.41 to 5.32) and 4.53 (95% CI 4.11 to 4.96) in patients with and without uveitis, respectively (Table 3; Supplementary Fig. S2). BASDAI score showed a trend of high in disease activity was observed between patients with and without uveitis (MD 0.11; 95% CI − 0.06 to 0.28, p = 0.21, I2 = 76%; Table 3; Fig. 2). The pooled mean BASFI scores were 3.89 (95% CI 3.53 to 4.25) and 3.97 (95% CI 3.65 to 4.28) for patients with and without uveitis, respectively (Table 3; Supplementary Fig. S2). No significant difference in BASFI scores was observed between patients with and without uveitis (MD − 0.12, 95% CI − 0.46 to 0.21, p = 0.47; Table 3; Supplementary Fig. S3).

The pooled mean CRP levels were 15.78 (95% CI 8.38 to 23.18) mg/L and 14.53 (95% CI 8.69 to 20.38) mg/L in patients with and without uveitis, respectively (Table 3; Supplementary Fig. S2). The CRP level was non-significantly higher in patients with uveitis than in those without uveitis (MD 1.48; 95% CI − 0.17 to 3.14 mg/L, p = 0.08; Table 3; Supplementary Fig. S3). The pooled mean ESR levels were 28.19 (95% CI 7.64 to 48.75) mm/h and 28.16 (95% CI 17.91 to 38.42) mm/h in patients with and without uveitis, respectively (Table 3; Supplementary Fig. S2). No significant difference in the ESR level was observed between patients with and without uveitis (MD − 0.80; 95% CI − 4.62 to 3.03 mm/h, p = 0.68; Table 3; Supplementary Fig. S3).

Subgroup analysis

The heterogeneity among the included studies was obvious and we performed subgroup analysis for the mean difference of BASDAI score observed between SpA patients with and without uveitis. In the included studies, there were three study characteristics that may have affected the results. First, the delay diagnosis varied from 1.6 to 17.9 years. Second, the characteristics of participants varied in diagnostic criteria of SpA, sample size of patients and gender ratios. Third, the study design varied between cross-sectional and cohort studies.

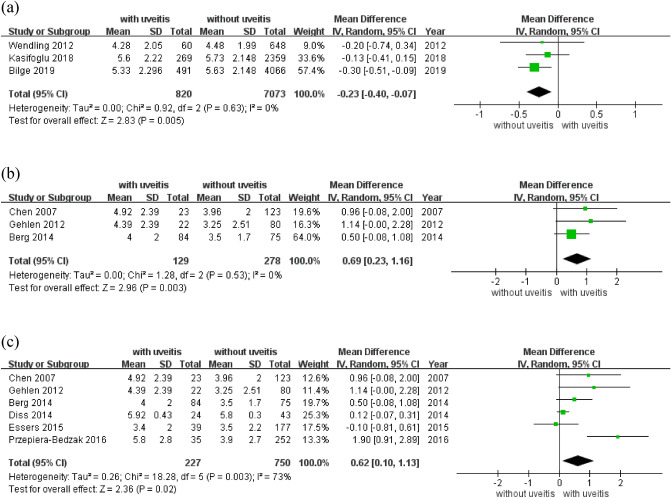

In the subgroup analysis, the BASDAI score was significantly low in patients of SpA with uveitis and delay diagnosis less than 5 years (MD − 0.23; 95% CI − 0.40 to − 0.07, p = 0.005, I2 = 0%) and it was high in study design as cross-sectional method (MD 0.69; 95% CI 0.23 to 1.16, p = 0.003, I2 = 0%; Table 4; Fig. 3). This could be due to the disease activity of SpA with uveitis is higher than without. However, if diagnosed and treated within the first five years from symptom onset, the disease activity of SpA with uveitis can be lower than without. The non-significant result and heterogeneity was found in study design as cohort method (MD 0.03; 95% CI − 0.14 to 0.20, I2 = 76%). A possible explanation could be that the cohort studies included multiple confounding factors. The score in sample size ≤ 500 patients was significant in high but with moderate heterogeneity (MD 0.62; 95% CI 0.10 to 1.13, p = 0.003, I2 = 73%; Table 4; Fig. 3). In the six studies of subgroup of sample size ≤ 500 patients, there were three cross-sectional7,17,18 and three cohort studies8,14,20, the heterogeneity may be attributed to differences in study design. There was a nonsignificant difference in delay diagnosis over 5 years (MD 0.15; 95% CI − 0.22 to 0.51). BASDAI scores also had nonsignificant differences in the groups of diagnostic criteria of SpA, the sample size of patients > 500 patients and gender ratios (Table 4; Supplementary Fig. S4).

Table 4.

Subgroup analysis of mean difference of BASDAI score in spondyloarthritis patients with and without uveitis of the included studies.

| Subgroup | Mean difference | 95% CI | p value | I2 (%) | n* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delay diagnosis | |||||

| ≤ 5 years | − 0.23 | − 0.40 to − 0.07 | 0.005 | 0 | 3 |

| > 5 years | 0.15 | − 0.22 to 0.51 | 0.43 | 67 | 4 |

| Diagnostic criteria | |||||

| NY | 0.38 | − 0.15 to 0.92 | 0.16 | 36 | 3 |

| ESSG | 0.04 | − 0.23 to 0.31 | 0.79 | 31 | 4 |

| Study design | |||||

| Cross-sectional | 0.69 | 0.23 to 1.16 | 0.003 | 0 | 3 |

| Cohort | 0.03 | − 0.14 to 0.20 | 0.72 | 76 | 10 |

| Sample size | |||||

| ≤ 500 patients | 0.62 | 0.10 to 1.13 | 0.02 | 73 | 6 |

| > 500 patients | − 0.05 | − 0.21 to 0.10 | 0.50 | 63 | 7 |

| % male | |||||

| > 70% | 0.33 | − 0.14 to 0.79 | 0.17 | 64 | 4 |

| ≤ 70% | 0.05 | − 0.16 to 0.26 | 0.63 | 79 | 8 |

*Number of study.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the subgroup analysis of BASDAI in patients of spondyloarthritis with and without uveitis. (a) Delay diagnosis less than 5 years, (b) Study Design: Cross-sectional, (c) Sample Size <500 patients.

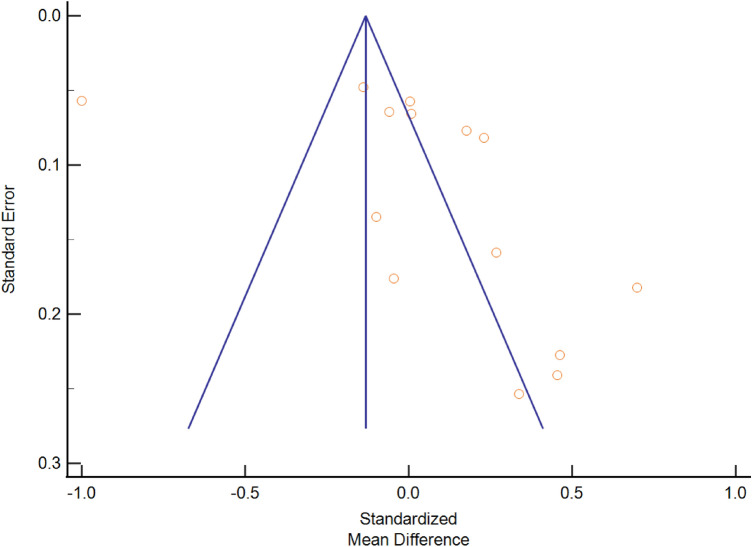

Publication bias

The asymmetrical funnel plot indicated the publication bias in this meta-analysis (Fig. 4). We performed Egger’s test to confirm the existence of bias but without significance (t value = 4.25, df = 13, p = 0.14).

Figure 4.

Funnel plot for publication bias.

Discussion

In a previous meta-analysis, the mean delay in the diagnosis of SpA was 6.7 (95% CI 6.2 to 7.2) years11, and in the present study, that of SpA with and without uveitis was 6.08 and 5.41 years, respectively. The delay in the diagnosis of SpA significantly differed between patients with and without uveitis (Table 3).

Uveitis can be the first presenting symptom of SpA, and studies have reported a prevalence of 40–50% of previously undiagnosed SpA in patients presenting with uveitis3,13. Wendling et al.6 reported that uveitis occurred before the first symptom of inflammatory back pain in 37% and simultaneously in 18% of cases. The delay in the diagnosis of SpA is associated with poor functional impairment, rapid radiographic progression, poor quality of life, and decreased treatment response11. In the present study, the pooled mean BASDAI score was the highest for a delay of 2–5 years (5.60, 95% CI 5.47 to 5.73). By contrast, the pooled mean BASFI score was the lowest for a delay of < 2 years (2.92, 95% CI 2.48 to 3.37), and its severity gradually increased to a delay of > 10 years (4.17, 95% CI 2.93 to 5.41; Table 3). Early recognition can lead to the early initiation of the most appropriate and effective therapy. Early diagnosis of SpA may reduce the adverse effects of the disease and improve functional ability. In this study, we found that patients with SpA with uveitis had a prolonged delay in diagnosis, which was highly associated with higher BASFI scores and poorer prognostic outcomes (Table 3). Awareness regarding uveitis is crucial considering its role in the diagnostic process of SpA for treatment choices and health-related quality of life4.

Backache or arthralgia were not the primary symptom of patients with SpA with uveitis during their presentation to an ophthalmologist. The degree of pain and disability, as reflected by BASDAI and BASFI scores, was often noted to be mild13. In the present study, the BASDAI score was significant lower in patients of SpA with uveitis with delay diagnosis less than 5 years (MD − 0.23; 95% CI − 0.40 to − 0.07). Previous studies have examined disease activity by using different assessment systems. Approximately 40–65% of patients with low BASDAI scores (< 4) had high disease activity, as measured using the ASDAS (≥ 2.1)25–27. In this study, we found a higher disease activity, as measured using the ASDAS (MD 0.18; 95% CI 0.11 to 0.25), in patients with SpA with uveitis than in those without. Measuring the BASDAI rather than the ASDAS is routine in clinical practice. However, some patients of uveitis especially early undiagnosed SpA suspected to have high disease activity despite low BASDAI scores should be examined using the ASDAS.

In the present study, we found no significant difference in the ESR between patients with and without uveitis (MD − 0.80; 95% CI − 4.62 to 3.03 mm/h). However, the CRP level tended to be higher in patients with uveitis (MD 1.48; 95% CI − 0.17 to 3.14 mg/L). Furthermore, we performed a subgroup analysis of ASDAS-CRP and ASDAS-ESR. Although the ASDAS might be affected by infectious or inflammatory conditions, it is regarded as more objective than the BASDAI. The ASDAS-CRP was significantly higher in patients with SpA with uveitis (MD 0.17; 95% CI 0.10 to 0.24). However, ASDAS-ESR did not differ between patients with and without uveitis (MD 0.03; 95% CI − 0.65 to 0.72; Table 3).

Uveitis may be a key feature leading to SpA diagnosis6,12,17. The nonspecific and often subtle symptoms of inflammatory back pain make early diagnosis and subsequent treatment challenging. In the subgroup analysis, the BASDAI score was significant higher in SpA patients with uveitis in study design as cross-sectional method (MD, 0.69; 95% CI 0.23 to 1.16). Patients with SpA with uveitis exhibited a marked reduction in the activities of daily living compared with those without uveitis (47.1% vs. 23.5%)17,28. However, in this study, no significant difference in BASFI scores was noted (MD − 0.12; 95% CI − 0.46 to 0.21). Because the delay in diagnosis was significantly longer in patients with uveitis, we further analyzed the pooled mean BASFI score. The lowest in delay diagnosis of < 2 years was 2.92 (95% CI 2.48 to 3.37), and the scores gradually increased to delay in diagnosis of > 10 years (4.17, 95% CI 2.93 to 5.41). Prolonged delay in diagnosis is common among patients with SpA and the occurrence of uveitis may be the reason for their first interaction with medical care, the occurrence of uveitis presents a unique opportunity for identifying such patients with undiagnosed SpA29. Therefore, awareness regarding uveitis among ophthalmologists and primary care physicians is vital considering its role in the diagnostic process and the selection of appropriate treatment for improving health-related quality of life4.

This study has some limitations that should be addressed. First, in our included studies, the disease activity indices of BASDAI, ASDAS and BASFI all require patients to answer the questionnaire and it is quite challenging for physician and patients to determine and make the assessment. Most of the SpA-related uveitis was diagnosed by ophthalmologists, however some of the history of uveitis was patients’ self-reported and this may reduce the accuracy. This may cause variations in findings among different geographical regions. Moreover, in terms of baseline characteristics, the included studies did not provide the age of uveitis diagnosis. We found the BASDAI was significant lower in patients of SpA with uveitis in delay diagnosis less than 5 years (MD − 0.23; 95% CI − 0.40 to − 0.07). Uveitis may occur before SpA symptoms or diagnosis6,12,17. The reason for a longer delay in diagnosis of SpA in patients with uveitis may be due to the mild symptoms of SpA. Additional cohort studies focusing on the age at diagnosis in patients of SpA and uveitis should be conducted.

In the present study, we found that patients with SpA with uveitis had a longer delay in diagnosis than did those without. Uveitis is the most frequent EAM in SpA3 and may affect disease activity, quality of life, and treatment decisions. In our meta-analysis, we found a significant difference in ASDAS-CRP and BASDAI between patients with and without uveitis. Screening patients of uveitis by using validated evaluation tool such as the DUET assessment algorithm13 allows for early identification of patients and the provision of an appropriate management plan. Early diagnosis of SpA may reduce the adverse effects of the disease and improve functional outcome of SpA patients.

Methods

Data source and search strategy

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines30. The protocol for this review was registered in advance (PROSPERO: CRD42021285146). We performed a comprehensive search of peer-reviewed articles indexed in the electronic databases of PubMed, EMBASE, and Scopus. In addition, we examined the reference lists of the retrieved articles to identify additional studies for inclusion. The timeframe for the electronic search spanned from January 2000 to December 2021, and no language restriction was applied. Search terms were “ankylosing spondylitis”, “AS”, “spondylarthropathy”, “spondylarthritis”, “spondyloarthropathy”, “spondyloarthritis”, “SpA”, “uveitis”, “disease activity”, “BASDAI”, “BASFI”, and “ASDAS”. An extended search by using conference proceedings, conference abstracts, dissertations, and editorials was conducted to identify potentially relevant unpublished or gray literature.

Study selection

Studies that met the following criteria were included in this study: (a) those including diagnostic criteria for SpA and AS, (b) those including patients diagnosed as having uveitis, and (c) those providing the mean value with the standard deviation (SD) of the BASDAI, BASFI, or ASDAS. We excluded review articles, case reports, and studies of duplicate populations.

Two authors (SL and CY) independently conducted the electronic search. Any disagreement was resolved by a third author (KY). When multiple articles were published for a single study, we used the most relevant publication and supplemented it with data from the authors’ other publications when necessary. The authors of studies were contacted when pertinent information was not available in the published version.

Variables and outcome measures

The patients were diagnosed as having SpA according to the classification criteria of the European Spondylarthropathy Study Group31 and the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society32. The diagnosis of AS was established according to the modified New York criteria33. PsA and SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis) syndrome were diagnosed according to the Caspar classification criteria34 and Kahn criteria35, respectively.

The BASDAI consists of six numerical rating scales (scores ranging from 0 to 10) for measuring the severity of fatigue, spinal and peripheral joint pain, enthesitis, localized tenderness, and morning stiffness in patients with SpA16. The ASDAS includes the self-reported indices of back pain, duration of morning stiffness, peripheral joint pain and swelling, and patients’ global assessment of disease activity. In addition, the ASDAS includes laboratory measures, such as the CRP level and ESR, and each parameter is weighted and not simply added up as in the BASDAI1,25. The BASFI is used for assessing physical functioning in patients with SpA36.

Quality assessment

We examined the risk of bias in the included studies according to the following six key domains by using the risk-of-bias assessment tool for nonrandomized studies (RoBANS)24: (a) selection of participants, (b) confounding variables, (c) measurement of exposure, (d) blinding of outcome assessments, (e) incomplete outcome data, (f) selective outcome reporting, and (g) other sources of bias. We graded each potential source of bias as yes, no, or unclear if the potential for bias was high, low, or unknown, respectively.

Data synthesis and analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager 5.4 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) and MedCalc (Version 19.5.3, Ostend, Belgium)37. For continuous variables, mean differences (MDs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. To perform a generic inverse variance meta-analysis, pooled mean values and 95% CIs were calculated from reported mean values with standard errors. When the mean delay to diagnosis was not reported, it was imputed as the difference in the mean age at symptom onset and the mean age at diagnosis. When the SD of diagnostic delay was missing, we imputed it by using methods recommended by Cochrane (based on the SD of age at onset, age at diagnosis, and their correlation in all studies)38.

Heterogeneity across studies was assessed through the I2 statistic. An I2 statistic of > 50% was considered to indicate substantial heterogeneity39. If substantial heterogeneity existed, subgroup analyses would be conducted to explore the heterogeneity. The primary analysis was based on published studies and unpublished conference proceedings. Because the meta-analysis included ≥ 10 studies, we investigated publication bias by using funnel plots40. A two-sided p value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

S.C.L. was the chief investigator of the study. S.C.L. and C.H.Y. were responsible for the literature search and study identification. The risk of bias assessment was performed by K.H.Y and Y.C.T. Data extraction and statistical analysis were conducted by S.C.L. S.C.L. prepared the first draft of the paper. All authors reviewed the draft and contributed to the final version.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-41971-z.

References

- 1.van der Heijde D, et al. ASDAS, a highly discriminatory ASAS-endorsed disease activity score in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009;68:1811–1818. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.100826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun J, Sieper J. Early diagnosis of spondyloarthritis. Nat. Clin. Pract. Rheumatol. 2006;2:536–545. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Bentum RE, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE. Axial spondyloarthritis in the era of precision medicine. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2020;46:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2020.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stolwijk C, van Tubergen A, Castillo-Ortiz JD, Boonen A. Prevalence of extra-articular manifestations in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015;74:65–73. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watad A, Bridgewood C, Russell T, Marzo-Ortega H, Cuthbert R, McGonagle D. The early phases of ankylosing spondylitis: Emerging insights from clinical and basic science. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:2668. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wendling D, Prati C, Demattei C, Miceli-Richard C, Daures JP, Dougados M. Impact of uveitis on the phenotype of patients with recent inflammatory back pain: Data from a prospective multicenter French cohort. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1089–1093. doi: 10.1002/acr.21648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg IJ, et al. Uveitis is associated with hypertension and atherosclerosis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: A cross-sectional study. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44:309–313. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Przepiera-Bedzak H, Fischer K, Brzosko M. Extra-articular symptoms in constellation with selected serum cytokines and disease activity in spondyloarthritis. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:7617954. doi: 10.1155/2016/7617954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Man S, et al. Characteristics associated with the occurrence and development of acute anterior uveitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and psoriasis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: Data from the Chinese ankylosing spondylitis prospective imaging cohort. Rheumatol. Ther. 2021;8:555–571. doi: 10.1007/s40744-021-00293-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lian F, et al. Anti-TNFalpha agents and methotrexate in spondyloarthritis related uveitis in a Chinese population. Clin. Rheumatol. 2015;34:1913–1920. doi: 10.1007/s10067-015-2989-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao SS, Pittam B, Harrison NL, Ahmed AE, Goodson NJ, Hughes DM. Diagnostic delay in axial spondyloarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology. 2021;60:1620–1628. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yasar BNS, et al. Uveitis-related factors in patients with spondyloarthritis: Treasure real-life results. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021;228:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haroon M, O'Rourke M, Ramasamy P, Murphy CC, FitzGerald O. A novel evidence-based detection of undiagnosed spondyloarthritis in patients presenting with acute anterior uveitis: The DUET (Dublin Uveitis Evaluation Tool) Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015;74:1990–1995. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Essers I, et al. Characteristics associated with the presence and development of extra-articular manifestations in ankylosing spondylitis: 12-year results from OASIS. Rheumatology. 2015;54:633–640. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redeker I, et al. The impact of extra-musculoskeletal manifestations on disease activity, functional status, and treatment patterns in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: Results from a nationwide population-based study. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2020;12:1759720X20972610. doi: 10.1177/1759720X20972610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A. A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: The Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J. Rheumatol. 1994;21:2286–2291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen CH, et al. Association of acute anterior uveitis with disease activity, functional ability and physical mobility in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: A cross-sectional study of Chinese patients in Taiwan. Clin. Rheumatol. 2007;26:953–957. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gehlen M, Regis KC, Skare TL. Demographic, clinical, laboratory and treatment characteristics of spondyloarthritis patients with and without acute anterior uveitis. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2012;130:141–144. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802012000300002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sampaio-Barros PD, et al. An analysis of 372 patients with anterior uveitis in a large Ibero-American cohort of spondyloarthritis: The RESPONDIA Group. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2013;31:484–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diss JKJ, Georgiou A, Michael C, Rajan N, Shah A, Roussou E. Differences in uveitis versus non-uveitis individuals with HLA-B27-postive spondyloarthritis with regard to first presenting symptoms. Rheumatology. 2014;53:i144–i145. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu115.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.da Costa IP, et al. Evaluation of performance of BASDAI (Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index) in a Brazilian cohort of 1,492 patients with spondyloarthritis: Data from the Brazilian Registry of Spondyloarthritides (RBE) Rev. Bras. Reumatol. 2015;55:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.rbr.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kasifoglu T, et al. Factors that may be associated with uveitis in patients with spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70:1843–1844. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bilge, N. S. Y., Kasifoglu, T., & Kalyoncu, U. Uveitis related factors in patients with spondyloarthritis. In EULAR Poster Presentations, 491 (2019).

- 24.Kim SY, et al. Testing a tool for assessing the risk of bias for nonrandomized studies showed moderate reliability and promising validity. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013;66:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nam B, et al. Low BASDAI score alone is not a good predictor of anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment efficacy in ankylosing spondylitis: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2021;22:140. doi: 10.1186/s12891-020-03941-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fagerli KM, et al. Selecting patients with ankylosing spondylitis for TNF inhibitor therapy: Comparison of ASDAS and BASDAI eligibility criteria. Rheumatology. 2012;51:1479–1483. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marona J, et al. Eligibility criteria for biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in axial spondyloarthritis: Going beyond BASDAI. RMD Open. 2020;6:25. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2019-001145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gran JT, Skomsvoll JF. The outcome of ankylosing spondylitis: A study of 100 patients. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1997;36:766–771. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.7.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan MA, Haroon M, Rosenbaum JT. Acute anterior uveitis and spondyloarthritis: More than meets the eye. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2015;17:59. doi: 10.1007/s11926-015-0536-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dougados M, et al. The European Spondylarthropathy Study Group preliminary criteria for the classification of spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:1218–1227. doi: 10.1002/art.1780341003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rudwaleit M, et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society classification criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis and for spondyloarthritis in general. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011;70:25–31. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.133645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:361–368. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor W, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: Development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2665–2673. doi: 10.1002/art.21972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan, M.A. The SAPHO-syndrome. In Psoriatic Arthritis. Bailliere's Clinical Rheumatology (H Wright Ed.), vol, 8 , 333–62 1994 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Calin A, et al. A new approach to defining functional ability in ankylosing spondylitis: The development of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index. J. Rheumatol. 1994;21:2281–2285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schoonjans F, Zalata A, Depuydt CE, Comhaire FH. MedCalc: A new computer program for medical statistics. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 1995;48:257–262. doi: 10.1016/0169-2607(95)01703-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins, J. P. T. et al. Chapter 6, Section 6.5.2.8: Imputing standard deviations for changes from baseline. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-06#section-6-5-2-8.

- 39.Borenstein M. Fixed-effect versus random-effects models. In: Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein S, editors. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Wiley; 2009. pp. 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.