Structured Abstract

Objective:

Postpartum women can develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in response to complicated, traumatic childbirth; prevalence of these events remains high in the U.S. Currently, there is no recommended treatment approach in routine peripartum care for preventing maternal childbirth-related PTSD (CB-PTSD) and lessening its severity. Here, we provide a systematic review of available clinical trials testing interventions for the prevention and indication of CB-PTSD.

Data Sources:

We conducted a systematic review of PsycInfo, PsycArticles, PubMed (MEDLINE), ClinicalTrials.gov, CINAHL, ProQuest, Sociological Abstracts, Google Scholar, Embase, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and Scopus through December 2022 to identify clinical trials involving CB-PTSD prevention and treatment.

Study Eligibility Criteria:

Trials were included if they were interventional, evaluated CB-PTSD preventive strategies or treatments, and reported outcomes assessing CB-PTSD symptoms. Duplicate studies, case reports, protocols, active clinical trials, and studies of CB-PTSD following stillbirth were excluded.

Study Appraisal and Synthesis Methods:

Two independent coders evaluated trials using a modified Downs and Black methodological quality assessment checklist. Sample characteristics and related intervention information were extracted via an Excel-based form.

Results:

A total of 33 studies, including 25 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 8 non-RCTs, were included. Trial quality ranged from Poor to Excellent. Trials tested psychological therapies most often delivered as secondary prevention against CB-PTSD onset (n=21); some examined primary (n=3) and tertiary (n=9) therapies. Positive treatment effects were found for early interventions employing conventional trauma-focused therapies, psychological counseling, and mother-infant dyadic focused strategies. Therapies’ utility to aid women with severe acute traumatic stress symptoms or reduce incidence of CB-PTSD diagnosis is unclear, as is whether they are effective as tertiary intervention. Educational birth plan-focused interventions during pregnancy may improve maternal health outcomes, but studies remain scarce.

Conclusions:

An array of early psychological therapies delivered in response to traumatic childbirth, rather than universally, in the first postpartum days and weeks, may potentially buffer CB-PTSD development. Rather than one treatment being suitable for all, effective therapy should consider individual-specific factors. As additional RCTs generate critical information and guide recommendations for first-line preventive treatments for CB-PTSD, the psychiatric consequences associated with traumatic childbirth could be lessened.

Keywords: Antepartum Education, Cesarean Section, Childbirth-related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (CB-PTSD), Childbirth Trauma, Delivery, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), Maternal-Infant Attachment, Maternal Morbidity, Maternal Near-Miss, Obstetric Complications, Obstetrics, Postpartum Period, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Preterm, Psychological Counseling, Psychological Debriefing, Psychological Intervention, Skin to Skin, Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Trauma-Focused Expressive Writing

Introduction

Childbirth is a profound experience often entailing extreme physical and psychological stress. Among delivering women, an estimated 1/3 experience highly stressful and potentially traumatic birth,1–3 and ~60,000 women in the U.S. each year experience severe maternal morbidity (SMM).4 SMM rates in the U.S. are among the highest in Western countries5–7 and steadily continue to increase.5,8–10

Complicated deliveries may undermine maternal psychological welfare. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the formal psychiatric disorder resulting from exposure to an event involving life-threat or physical harm and associated psychological symptoms that do not resolve naturally over time.11 Existing research supports the validity of PTSD following childbirth, or childbirth-related PTSD (CB-PTSD).12 The prevalence of this condition is estimated at 5–6% of all postpartum women;3,13,14 this translates nationally to 240,000 affected American women each year. In complicated deliveries, 18.5% to 41.2% of women14–16 report CB-PTSD symptoms. Black and Latinx women are nearly three times more likely to endorse a childbirth-related traumatic stress response.17

Although highly co-morbid with peripartum depression,18–20 CB-PTSD is a distinct condition largely consistent with the formal symptom constellation of PTSD.21 Exposure to a traumatic childbirth can result in childbirth-related involuntary intrusion symptoms such as flashbacks and nightmares; attempts to avoid reminders of childbirth; negative alterations in cognitions and mood, and marked arousal and reactivity manifested in irritability, sleep and concentration problems, hypervigilance, and other symptoms.22–24

When left untreated, CB-PTSD can impair maternal functioning during the important postpartum period. Women with CB-PTSD may exhibit reduced maternal affection, bonding, and sensitive behavior toward their infant,25–28 which may increase the risk for social and emotional developmental problems in the infant.27,29 Available research suggests that maternal CB-PTSD associates with infant behavioral problems, as well as sleep and feeding problems, including less favorable breastfeeding outcomes.29 Untreated CB-PTSD can also result in avoidance of partner intimacy and disincentivize future pregnancies.30–32

CB-PTSD has unique attributes that support the potential for early intervention and even prevention. PTSD symptoms begin after a specified external traumatic event (here, childbirth) and appear in the first days following exposure,18,33,34 suggesting that CB-PTSD follows a clear onset. Theoretical models of non-childbirth PTSD pathogenesis suggest that beyond pre-existing vulnerabilities, biological and psychological mechanisms underlie an individual’s immediate response to a traumatic event that could be targeted by interventions to buffer and avert the PTSD trajectory.35–38 Consequently, early interventions could produce favorable outcomes. Unlike other forms of trauma, childbirth is a relatively time-defined event for which women often stay in the hospital after parturition. This suggests an important opportunity to identify and treat women before they develop the full traumatic stress syndrome.

Presently, there is a critical gap in knowledge to inform recommendations to prevent and treat CB-PTSD. Early review studies on this topic used the limited number of available clinical trials, preventing firm conclusions about the utility of psychological debriefing and individual counseling therapies.39–41 In recent years, 6 systematic reviews have been performed that focused mostly on early interventions; they included 45 trials published up to 2022.42–47 The reviews concluded that early-administered trauma-focused interventions that work through exposure and reprocessing of the traumatic memory and related cognitions appear helpful for alleviating symptoms of CB-PTSD in the short term, but that more studies were warranted to establish clinical recommendations.

Objectives

We provide a comprehensive systematic review of randomized and non-randomized controlled clinical trials for preventing CB-PTSD onset or reducing symptoms severity in affected women. We used a quantitative rating system to evaluate the published trials’ quality.48 To the best of our knowledge, this approach has not previously been implemented. We reviewed the potential benefits of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention approaches for CB-PTSD to provide insight into which therapies are most promising, what the optimal timing for intervention may be, and which populations will benefit most from these interventions. Publication dates range from December 1998 to December 2022.

Methods

a. Eligibility Criteria, Information Sources and Search Strategy

To be included in this review, studies were independently evaluated based on the following inclusion criteria: a) interventional study; b) indication of CB-PTSD prevention or treatment; and c) inclusion of outcome measure(s) assessing CB-PTSD symptoms or diagnosis. Duplicate studies, case reports, study protocols, active clinical trials, and studies involving mothers who exclusively experienced stillbirth were excluded.

This systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines,49 and our protocol is registered on PROSPERO (CRD42020207086). Our search strategy targeted all published studies measuring CB-PTSD or its symptoms as a primary treatment outcome. Articles published through December 2022 were included from the following databases: PsycInfo, PsycArticles, PubMed (MEDLINE), ClinicalTrials.gov, CINAHL, ProQuest, Sociological Abstracts, Google Scholar, Embase, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and Scopus. The search criteria employed any combination of these keywords: “Postpartum OR postnatal OR childbirth PTSD” OR “traumatic childbirth” OR “childbirth induced post-traumatic stress” AND “treatment OR intervention OR therapy OR prevention”. Published reviews on CB-PTSD therapies served as additional resources.

b. Study Selection

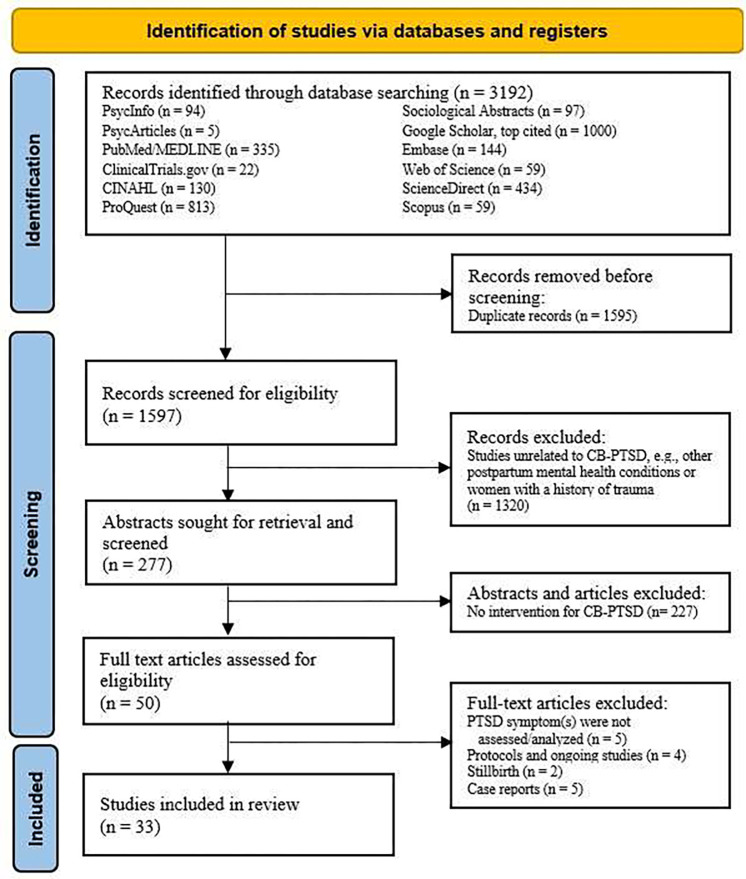

A total of 33 studies published from December 1998 to December 2022 met inclusion criteria and were reviewed. This selection followed the PRISMA workflow process;49 for more information regarding study selection, see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram detailing the source selection process of both randomized and non-randomized clinical studies targeting childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder (CB-PTSD) in at-risk and universal samples.

c. Data Extraction

Two reviewers (J.P. and R.N.) extracted data using an Excel-based form. For each study, the reviewers collected: sample characteristics, treatment type (prevention/treatment) and modality, intervention frequency/duration, primary outcome measures, and outcome time points (immediate, moderate, and long-term). We report treatment effects on CB-PTSD symptoms and related conditions. Details are presented in Table 1.

d. Assessment of Risk of Bias, and Quality Assessment

We adopted the well-validated, commonly used Downs and Black checklist48 that is recommended for evaluating the quality of randomized and non-randomized healthcare interventions. This 27-item checklist offers a quantitative rating scale that is a composite measurement of external validity, internal validity/confounding bias, and statistical power. Individual items are scored on an integer scale of 0 to 1, for a total score of 28 (with item 5 scored 0–2). A study’s overall quality score is calculated using the checklist’s assigned point system, with higher score indicating higher study quality. In this review, to better identify high-quality trials, items 20, 21, and 27 (“Were the main outcome measures used accurate?”; “Were the patients in different intervention groups or were the cases and controls recruited from the same population?”; “Were study subjects randomized to intervention groups?”, respectively) were scored on a 0–2 scale, as done in previous studies,50–52 with a maximum total score of 31. Modified quality score ranges were specified as: Excellent (29–31); Good (22–28); Fair (17–21); Poor (≤16).

The two reviewers independently scored all 33 studies. Inter-rater reliability was high (91%), and any discrepancy in scores was discussed until 100% agreement was achieved. The quality scores and adopted checklist are presented in Table 1 and Appendix A, respectively.

Results

a. Study Selection

In this review of 33 studies, 25 were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 8 were non-RCTs. Among all trials, 3 tested primary preventive interventions delivered during pregnancy; 19 tested secondary preventions in which treatment was provided after childbirth but not later than 1 month postpartum, i.e., before a DSM PTSD diagnosis can be confirmed;11 and 11 trials involved tertiary prevention delivered more than 1 month postpartum, in cases with confirmed or probable CB-PTSD.

Of the 33 studies, 31 entailed psychologically oriented therapies. These included trauma-focused structured and non-structured interventions (n=19), i.e., psychological debriefing, crisis intervention, Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT), Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), and Trauma-Focused Expressive Writing (TF-EW); mother-infant dyad therapies (n=3); psychological counseling (n=5); and other psychological approaches, i.e., visual biofeedback (n=1) and visual spatial cognitive task (n=2). The remaining 3 trials were educational interventions (Table 1).

In most trials, treatment response was determined using validated patient self-administered questionnaires to measure endorsement of CB-PTSD symptoms (n=30). Clinician evaluation to determine CB-PTSD endorsement was performed in 3 trials. Assessment of sustained treatment outcomes usually targeted the first months following the intervention (n=27, ≥1.5 months, ≤6 months); longer effects (≥12 months post-intervention) were measured in 6 trials.

b. Study Characteristics and Risk of Bias Results

Detailed information on the study characteristics and quality assessment results are presented in Table 1.

c. Synthesis of Results

Psychologically Oriented

Debriefing or Trauma-Focused Psychological Therapies (TFPT)

Psychological debriefing in the postpartum is usually performed as an early intervention via midwife-led dialogue involving delivery-related emotions.44,53,54 When treating CB-PTSD, the stressful aspects of the childbirth experience are addressed. Debriefing was tested in 4 RCTs as early secondary prevention and 1 NRCT as later (tertiary) prevention. Quality scores ranged from Fair to Good (17–28).

Overall, although women generally consider debriefing of value, no evidence supports the psychological benefit of midwife-led postpartum debriefing following healthy55,56 or complicated57,58 deliveries. A single structured 15–60 minute debriefing session within 72 hours post-delivery vs. treatment as usual (TAU) was not associated with reduction in traumatic stress, depression,55,56 anxiety, or parenting distress,55 nor the proportion of incidences meeting CB-PTSD diagnosis.56 A sub-group of women receiving debriefing who experienced more medical interventions had more negative perceptions of childbirth than controls.55 Similarly, no sustained benefits were documented when debriefing was offered to women following complicated, traumatic deliveries, compared with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and/or TAU.57,58

Debriefing offered as a later treatment for women possibly affected by CB-PTSD symptoms is associated with positive outcomes; however, evidence is derived from a single NRCT. Compared with TAU (no debriefing), a single (60–90 minutes) debriefing session delivered ~16 weeks postpartum upon maternal request/referral reduced CB-PTSD symptoms and negative appraisals of childbirth, but not depression, in a sample of 80 women who met DSM Criterion A.59

Crisis Intervention

Trauma-Focused (TF) crisis intervention entails providing information about the impact of stress, identifying relevant resources, and learning relaxation techniques and coping strategies in the aftermath of trauma.60 A single NRCT tested TF intervention as secondary prevention for CB-PTSD; quality score was Fair (19).60

An early single-session TF crisis intervention performed in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in women experiencing premature delivery and therefore at elevated risk for CB-PTSD showed short-term benefits.60 The intervention was tested in an NRCT of 50 mothers of premature infants and was coupled with brief psychological aid and intense support during critical times. At time of hospital discharge, mothers receiving the intervention compared with TAU (can receive hospital minister counseling) had fewer overall CB-PTSD symptoms and fewer intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal symptoms.

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT) for CB-PTSD involves a manualized protocol in which cognitive distortions regarding the traumatic childbirth and related stressors are challenged to reorient adaptive thoughts and behaviors.23,42,61 TF-CBT was tested in 1 RCT and 1 NRCT as secondary prevention,62–64 and in 2 RCTs as tertiary prevention.65,66 Quality scores ranged from Fair to Good (20–27).

Early TF-CBT delivered during premature infant’s hospitalization in women at risk for CB-PTSD shows benefits.62,63 The therapy involves cognitive restructuring, muscle relaxation, construction of a narrative of the traumatic childbirth and NICU experience, psychoeducation, and infant redefinition.62,63 Consecutive (6, ~50 minutes) TF-CBT one-on-one sessions delivered 1–2 weeks following childbirth, vs. standard care, in an RCT of 105 women with clinically significant acute stress, yielded fewer CB-PTSD and postpartum depression (PPD) symptoms; positive treatment effects were sustained 6 months after childbirth.62,63 Similarly, consecutive (6, 90 minutes) TF-CBT group sessions in the NICU in 19 women (no controls) was associated with improved PPD, CB-PTSD, and anxiety symptoms, at 6 weeks and 6 months post-intervention, respectively.64

Findings are mixed for TF-CBT sessions focused on exposure and cognitive restructuring delivered in the months and years postpartum to affected women.65,66 A series of 6–8 consecutive TF-CBT internet sessions delivered 2–4 months following medically complicated delivery was not associated with better long-term outcomes vs. TAU (conventional support) in an RCT (N = 266).65 Improvement in CB-PTSD and PPD symptoms, and reported quality of life, assessed 1-year post-treatment were observed in both study conditions. In contrast, consecutive (8 weekly) sessions delivered ~2.8 years postpartum in women with provisional CB-PTSD66 were associated with improvement in CB-PTSD symptoms and reported quality of life compared with delayed (post 5 months) treatment in an RCT of 56 women, although improvement in anxiety and PPD symptoms was observed in both treatment conditions.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

Trauma-Focused Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (TF-EMDR) for CB-PTSD involves a standardized protocol in which women are instructed to focus briefly on their traumatic memories of childbirth while receiving bilateral eye stimulation to reprocess and alleviate childbirth-related traumatic stress.44 EMDR was tested in 1 RCT as secondary prevention67 and 2 NRCTs as tertiary prevention.68,69 Quality scores ranged from Poor to Good (13–25).

An early TF-EMDR intervention delivered during maternity hospitalization stay can reduce CB-PTSD symptoms in postpartum women at high risk for CB-PTSD, endorsing acute traumatic stress. A single (90-minute) session delivered within 72 hours post-delivery vs. TAU (standard psychological supportive therapy) in women with childbirth-related traumatic stress (N = 37) yielded significant reduction of CB-PTSD symptoms and subjective distress regarding recent and future deliveries, assessed 6 weeks and 3 months later.67 However, no group differences were found in the prevalence of CB-PTSD diagnosis post-treatment, and improvement in mother-infant bonding and PPD symptoms was noted in both conditions. In consecutive EMDR sessions in the months and years following childbirth in affected women endorsing CB-PTSD, positive outcomes are reported;68,69 it should be noted that the findings are derived from two NRCTs without control groups.

Trauma-Focused Expressive Writing

Trauma-Focused Expressive Writing (TF-EW) for CB-PTSD involves constructing a narrative about childbirth through writing with a focus on describing related thoughts and feelings.42,70 This is intended to facilitate reprocessing of the birth experience and enhance meaning making.71 TF-EW was tested in a total of 6 RCTs including 4 trials as secondary prevention and 2 trials as tertiary prevention. Quality scores ranged from Fair to Good (20–27).

TF-EW delivered in the very first days following uncomplicated pregnancies shows benefits. A single (10–15 minute) EW session about childbirth, compared with no writing, performed 48 hours postpartum in samples of 64(72) and 242(73) women, was associated with fewer hyperarousal and avoidance symptoms post-intervention. Sustained positive treatment effects (for hyperarousal) were observed at 2 months72,73 and 1 year73 following childbirth. Likewise, a single (~20 minute) TF-EW session about childbirth, compared with writing about daily events, performed ~96 hours post-delivery (N = 176), was associated at 3 months post-treatment with positive effects in reducing depressive and PTSD (hyperarousal and avoidance) symptoms.74 Immediate treatment effects were observed for depression.

Consecutive TF-EW sessions can benefit postpartum women who are at risk of CB-PTSD. In a non-selective sample of 113 women, early TF-EW (2 sessions in a single day) about childbirth delivered in the first postpartum days, compared with neutral writing, produced greater reduction in CB-PTSD (avoidance and hyperarousal) symptoms, and depressive symptoms 3 months later, especially for women with relatively higher stress at baseline.75 Likewise, in a high-risk sample of 67 women, TF-EW (3, 15-minute sessions) in the months following prematurity, focused on the childbirth and infant’s hospitalization, had positive outcomes. Compared with TAU (standard postpartum care), EW was associated with improvements in post-traumatic stress and depressive symptoms, and overall mental health status, 1 month following intervention. Treatment effects (for depression) were sustained 3 months later.76 Similarly, TF-EW (4, 30-minute sessions) post-discharge vs. waiting-list, in a sample of 38 postpartum women following premature delivery, was associated with improvement in post-traumatic stress 1 month post-intervention.77

Psychological Counseling

Psychological counseling for CB-PTSD in postpartum women usually entails semi-structured midwife-led intervention emphasizing the therapeutic relationship, acceptance of childbirth experiences, expression of emotions, social support, problem solving,39,78,79 and discussion of baby care-related issues.80 Psychological counseling was tested in 4 RCTs as secondary prevention, and 1 RCT as tertiary prevention. Quality scores ranged from Fair to Good (18–26).

One-on-one midwife-led psychological counseling in which the core intervention is conducted as a single session in the postpartum unit for women who experience traumatic childbirth shows positive effects.81,82 Two studies of 90 and 103 postpartum women, respectively, who experienced birth trauma and thus met DSM Criterion A, tested a single (40–60 minutes) counseling session within 72 hours post-delivery coupled with a phone session (40–60 minutes) 4–6 weeks postpartum vs. TAU.81,82 Counseling was associated with reduction in CB-PTSD and PPD symptoms,81,82 less self-blame, and greater confidence about future pregnancies 3 months later,82 although not reducing incidences of CB-PTSD diagnosis.82

A more intense early counseling therapy entailing consecutive sessions delivered in the postpartum unit and subsequently during postpartum weeks to women who experienced traumatic childbirth also showed benefits.80,83 A single one-on-one (45–60 minutes) counseling session delivered 24–48 hours post-delivery followed by a 45–90-minute session during postpartum care visit at 10–15 days, and a brief (15–20 minutes) counseling session via phone 4–6 weeks after delivery vs. TAU (routine post-partum care), were tested in a sample of 166 postpartum women meeting PTSD DSM Criterion A.80 Counseling sessions were associated with reduced CB-PTSD and PPD symptoms, and improved maternal-infant bonding at 2 months postpartum.80 Likewise, consecutive (2, 45–60 minutes) counseling sessions about the implications and consequences of an emergency Cesarean section, delivered before hospital discharge, and 2 additional sessions performed 2–3 weeks postpartum vs. TAU were tested in 99 postpartum women.83 Counseling was associated with fewer CB-PTSD symptoms, less general mental distress, and more positive appraisals of recent childbirth at 1 month postpartum, with effects sustained 6 months postpartum. However, the treatment was insufficient for women with substantial post-traumatic stress reactions or general distress.83

In contrast, intervention of later postpartum counseling group-format intervention sessions in months following traumatic childbirth does not appear promising. Consecutive (2, 60 minutes) sessions vs. TAU in 162 women who had emergency Cesarean section did not reduce level of fear of childbirth, nor CB-PTSD or PPD symptoms, at 6 months postpartum.84

Mother-Infant-Focused Interventions

Mother-infant dyad interventions target the maternal-infant interaction through various modalities including skin-to-skin contact and play sessions. Improvement in the mother-infant interaction is thought to promote maternal mental health.85–87 Dyad interventions were tested in 3 RCTs including 1 secondary prevention and 2 tertiary preventions.88–90 Study quality scores were Good (23–26).

Immediate postpartum mother-infant skin-to-skin contact can have positive effects in reducing CB-PTSD symptoms following traumatic childbirth.91 Skin-to-skin during the ‘magical’ first postpartum hour vs. TAU (routine postpartum skin-to-skin) in 84 women meeting DSM PTSD Criterion A was associated with fewer CB-PTSD symptoms 2 weeks and 3 months post-intervention.88

Brief therapist-led one-on-one consecutive dyad observational and play intervention sessions following prematurity and performed at a later postpartum time point show positive outcomes in improving maternal sensitivity and post-traumatic stress symptoms. A 3-phase (33 and 42 weeks post-conception, and infant age 4 months) intervention of ~5 observational and free play sessions (several hours in total) of mothers and their premature infants improved the quality of interactions in comparison with TAU (preterm without intervention) in a randomized sub-sample of 26 pairs.89 The treatment was associated with increase in maternal sensitivity and infant cooperation, decrease in infant difficulty, and significant decrease in CB-PTSD symptoms from time of intervention up to 12 months postpartum.89 In contrast, an earlier dyad-focused intervention initiated ~33 days postpartum and during infant NICU hospitalization stay was not associated with improved outcomes. A series of 6 sessions (5 in NICU and the last at home at 2–4 weeks post-discharge) focused on reading infants’ cues and responding was not found more helpful than TAU (standard care) in 121 women with very low birth weight infants.90

Other Psychologically Oriented Interventions

Other psychological interventions for CB-PTSD include biofeedback tested as primary prevention in an NRCT;92 and a cognitive visuospatial task tested as secondary and tertiary preventions in an RCT and NRCT, respectively.93,94 Study quality score ranged from Fair to Good (18–26).

Visual biofeedback ultrasound during the second stage of labor, involving the physician conveying a visual representation for the future mother of her pushing efforts and fetus movement in real time, shows benefits in reducing CB-PTSD risk. In an NRCT of 95 nulliparous women,92 ~5 minutes of biofeedback vs. TAU (standard obstetrical coaching) increased maternal-newborn connectedness in the immediate postpartum, which in turn was associated with reduced acute stress in initial postpartum days and subsequently reduced CB-PTSD symptoms at 1 month.92 There were no direct effects of the treatment on CB-PTSD symptoms.

A brief visuospatial cognitive task procedure performed in the immediate postpartum following emergency Cesarean delivery shows short-term positive effects.93 This therapy is thought to interfere with consolidation of the traumatic visual memory, making the memory less perceptual and less intrusive.95–97 A single 15-minute computer game Tetris session within 6 hours postpartum vs. TAU in a randomized sample of 56 women was found acceptable by subjects and was associated with fewer intrusive traumatic memories of childbirth 1 week post-delivery.93 However, no significant treatment effects were observed for CB-PTSD, anxiety, or depression symptoms at 1 month postpartum.93 Likewise, in a pilot NRCT of 18 women (without control group) with severe childbirth-related re-experiencing symptoms ~2 years postpartum, administered a single 20-minute Tetris session during childbirth recollection for the purpose of traumatic memory blockage,94 the majority reported fewer intrusive memories 1–2 weeks and 5–6 weeks post-intervention. For subjects who met CB-PTSD diagnosis, none met diagnosis at 1 month post-intervention.

Educational Interventions

Antenatal education aims to help expecting mothers via strategies for managing pregnancy, childbirth, and parenthood, and may also include postpartum interventions.98–100 Education interventions are provided by midwives and nurses. This review included 1 RCT101 and 1 NRCT102 primary educational prevention and 1 RCT secondary educational prevention.103 Study quality scores ranged from Good to Excellent (22–31).

Antenatal educational consecutive group sessions show benefit in non-high-risk women.102 Consecutive (4, 240 minutes) sessions focused on psychological and physiological adaption vs. TAU in a non-randomized sample of 90 second- and third-trimester pregnant women were associated with less fear of childbirth in pregnancy and more expected self-efficacy, and later at 6–8 weeks postpartum, with less fear of childbirth and fewer CB-PTSD symptoms.102 Likewise, consecutive one-on-one sessions focused on developing a birth plan vs. TAU in a randomized sample of 106 non-high-risk third-trimester women were associated with less fear of childbirth, improved childbirth experience, and fewer CB-PTSD and PPD symptoms 4–6 weeks post-delivery.101

In contrast, an early postpartum educational intervention utilizing self-help materials for women who had traumatic childbirth and were at risk for CB-PTSD without professional support was insufficient to reduce CB-PTSD symptoms. In an RCT of 678 women meeting PTSD DSM-IV Criterion A, subjects receiving self-help materials on how to manage early psychological responses during postpartum visit plus usual care, vs. TAU, did not show reduction in incidence of CB-PTSD diagnosis or sub-diagnosis assessed 6–12 weeks postpartum.103

Comment

a. Principal Findings

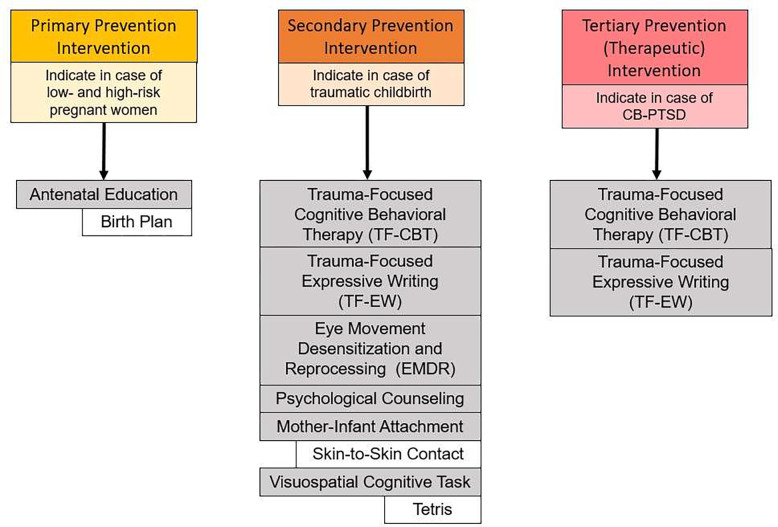

This systematic review provides insight derived from published randomized and non-randomized clinical trials of interventions tested in pregnant and postpartum women to inform evidence-based recommendations for primary and secondary prevention of CB-PTSD, and guidance for determining treatment approaches. Available studies (N=33) reviewed here range in quality between Poor and Excellent. They demonstrate that structured trauma-focused therapies and semi-structured midwife-led psychological counseling strategies are promising treatments (Figure 2). Other treatments to consider are traumatic memory blockage, mother-infant dyadic focused, and educational interventions (Figure 2). As additional RCTs are conducted, stronger evidence to support the efficacy of treatments for primary, secondary, or tertiary approaches will become available.

Figure 2.

Recommended primary, secondary, and tertiary (i.e., therapeutic) interventions to mitigate or prevent the development of childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder (CB-PTSD). Recommendations are based on 16 studies employing randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs) and reporting positive results. Grey boxes indicate categories of therapy strategy, and white boxes indicate specific implementations of those strategies. Trauma-Focused Expressive Writing (TF-EW) for secondary prevention was tested in universal samples.

An array of brief postpartum psychological interventions are safe, acceptable, and feasible to implement as early treatment, often before CB-PTSD presents as a clinically diagnosable disorder, thus minimizing serious consequences. A total of 16 RCTs reveal positive outcomes (Figure 2). Among them, the secondary preventions appear promising for reducing CB-PTSD symptoms compared with usual care in women exposed to traumatic childbirth. Evidence also supports the potential positive sustained effects of brief therapies (1–4 sessions) performed within 48–96 hours postpartum and during maternity hospitalization stay. This “in-house” approach could greatly facilitate access to postpartum care. Although psychological debriefing following childbirth trauma may not be helpful,40,53 the few available RCTs suggest the effectiveness of EMDR67 and Trauma-Focused Expressive Writing (TF-EW),72–75 which largely target fear extinction through reprocessing of the trauma memory; one or few sessions of psychological counseling led by a midwife near bedside;80–83 and interventions focused on the mother-infant dyad (and skin-to-skin contact)88–90 during the “sensitive period” following childbirth. This latter approach suggests a second therapeutic target. What remains unclear is whether useful interventions delivered in the early postpartum have efficacy as standalone treatments for women with acute clinically significant traumatic stress and whether they can reduce CB-PTSD diagnosis incidence.

Antepartum educational interventions delivered universally to pregnant women before childbirth may promote positive mental outcomes during pregnancy and following childbirth.101,102 The limited available evidence, based on two studies, suggests that universal interventions focused on birth plan and preparation are helpful, regardless of potential for exposure to traumatic childbirth. Postpartum educational interventions targeting women experiencing traumatic childbirth do not appear sufficient for reducing CB-PTSD incidence,103 underscoring the importance of the timing of educational interventions.

Interventions for the indication of CB-PTSD (tertiary prevention) with the goals of preventing worsening symptoms and improving functioning for women who endorse symptoms or have a diagnosis may have substantial benefits for the developing child. This review identified 5 RCT-tested interventions supporting the potential benefits of trauma-focused therapies (expressive writing and TF-CBT).

b. Comparison with Existing Literature

A large body of literature addresses treatment approaches for PTSD in non-postpartum individuals.104–106 Although trauma-focused interventions are the gold standard, they suffer from high dropout rate,107–109 and some individuals with PTSD will remain treatment resistant.110–112 This underscores the importance of intervening effectively in the aftermath of trauma to buffer the development of persistent symptoms.

Currently, limited data are available on effective interventions to prevent PTSD.45–47 Childbirth, however, provides a unique opportunity to test early post-birth therapies for PTSD stemming from traumatic childbirth, facilitated by immediate access to postpartum patients. This review provides new insight on promising secondary preventive approaches for CB-PTSD, including the benefits of intervening in the very first post-trauma exposure days, which, with more replicated and high-quality studies, could inform clinical recommendations. This review expands the emerging literature on CB-PTSD therapies by covering trials published through December 2022. The available data favor targeted rather than universal approaches to treat postpartum women.

c. Strengths and Limitations

This review adopts a comprehensive approach to evaluate available data on preventive interventions and treatments for CB-PTSD via quality assessment of all clinical trials published to date, not limited to a specific treatment modality, treatment time period, or maternal population. Hence, we provide insight into all three types of potential interventions, what the optimal timing for intervention may be, and which populations will benefit most. We use a well-validated standardized quantitative approach based on the PRISMA guidelines49 for study selection and data extraction, and assess external validity, internal validity, and power, to evaluate the published trials’ quality. While the primary outcome is CB-PTSD, we also consider co-morbid conditions, such as postpartum depression. Nevertheless, several limitations are worth noting. This review’s quality assessment was performed for each treatment modality separately, and grouping RCTs and non-RCTs studies into the relevant category. The main limitation in this approach is the small number of trials in some categories, which may limit the interpretation of the quality score range. Some studies lacked information about sample characteristics, degree of pre-treatment CB-PTSD severity, and clear time point of treatment outcome assessment, and these characteristics are only partly reflected in the assessment scale. Likewise, the definition of high-risk women exposed to childbirth trauma varied among studies and may have affected the ability to detect treatment effects. We did not intend to perform meta-analyses, which may have provided additional information. Finally, the number of published trials per prevention type is limited, which may prevent drawing strong conclusions.

d. Conclusions and Implications

Maternal psychiatric morbidities are a leading complication of childbirth113–115 and involve heavy public health costs.116–118 Substantial evidence shows that a significant portion of women experiencing traumatic childbirth develop persistent symptoms of childbirth-related PTSD (CB-PTSD),3,12,13,119 which cause functional impairment.24 Standards are lacking regarding what type of psychological therapy should be routinely delivered in postpartum care for the prevention or indication of this disorder, and this can have adverse consequences far beyond the directly affected postpartum woman. The available studies covered in this review suggest that intervening early in the postpartum period, and as soon as feasible, may reduce trauma reactions and in turn prevent CB-PTSD diagnosis. As a first step, this would require accurate identification of high-risk women who have experienced complicated, traumatic childbirth and may also show clinically significant acute stress.120 Early therapy delivered to high-risk women, rather than universally in the maternal population, would allocate available resources to those most in need and lower medical costs. A second critical step is ensuring treatment uptake during postpartum care. As presented in this review, manualized brief therapies delivered during maternity hospitalization stay offer a promising time window for effective therapy that also has the advantage of improving equity in care. A primary preventive approach in high-risk women may involve interventions focused on preparation for forthcoming childbirth delivered to pregnant women when they are already in frequent contact with health providers and during a time of motivation for self-care.

Important areas for future research include replicating the reported studies using adequate sample sizes, assessing long-term outcomes in RCT designs, shifting from exclusive patient self-report to also including mechanistic biomarkers, and identifying the golden hours following childbirth to maximize treatment response and uptake. Additionally, testing adjunctive or alternative non-trauma-focused intervention approaches that appear promising in individuals with general PTSD (e.g., mindfulness,121 yoga,122 metacognitive therapy (MCT)),123 and regarding resilience and psychological growth,124 therapies to enhance those traits, as well as the use of safe drug therapies (e.g., intra-nasal oxytocin),125 will expand available treatment options.

Ultimately, a personalized treatment approach incorporating therapeutic acceptability to the pregnant or postpartum woman and considering degree of symptom severity rather than a “one size fits all” strategy is likely to maximize treatment effectiveness. Based on the current state of knowledge, perinatal and mental health providers are strongly encouraged to consider on a case-by-case basis promising treatment options to prevent post-traumatic stress in the wake of childbirth trauma.

Supplementary Material

Table 1. Descriptions of clinical trials for interventions to prevent or treat childbirth-related maternal PTSD

Appendix A: Modified Downs and Black Checklist used in this systematic review.

Financial Support and Roles of Funding Sources:

Dr. Sharon Dekel was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD108619, R21HD100817, and R21HD109546) and an ISF award from the Massachusetts General Hospital Executive Committee on Research. Dr. Kathleen Jagodnik was supported by a Mortimer B. Zuckerman STEM Leadership Program Postdoctoral Fellowship. Ms. Joanna Papadakis was supported by a grant through the Menschel Cornell Commitment Public Service Internship at Cornell University. None of the funding organizations had a role in designing, conducting, or reporting this work.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Information for Systematic Review:

~ (i) Date of PROSPERO Registration: 07-12-2021

~ (ii) Registration Number: CRD42020207086

REFERENCES

- 1.Sommerlad S, Schermelleh-Engel K, La Rosa VL, Louwen F, Oddo-Sommerfeld S. Trait anxiety and unplanned delivery mode enhance the risk for childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in women with and without risk of preterm birth: a multi sample path analysis. PLoS One 2021;16:e0256681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turkmen H, Yalniz Dilcen H, Akin B. The effect of labor comfort on traumatic childbirth perception, post-traumatic stress disorder, and breastfeeding. Breastfeed Med 2020;15:779–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dekel S, Stuebe C, Dishy G. Childbirth induced posttraumatic stress syndrome: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. Front Psychol 2017;8:560. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control (2023) Reproductive Health: Severe Maternal Morbidity. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/smm/rates-severe-morbidity-indicator.htm Accessed 14 August 2023.

- 5.Snowden JM, Lyndon A, Kan P, El Ayadi A, Main E, Carmichael SL. Severe maternal morbidity: a comparison of definitions and data sources. Am J Epidemiol 2021;190(9):1890–1897. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwab077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossen LM, Womack LS, Hoyert DL, Anderson RN, Uddin SFG. The impact of the pregnancy checkbox and misclassification on maternal mortality trends in the United States, 1999–2017. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2020;3(44):1–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacDorman MF, Declercq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Is the United States maternal mortality rate increasing? Disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2016;128(3):447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger BO, Jeffers NK, Wolfson C, Gemmill A. Role of maternal age in increasing severe maternal morbidity rates in the United States. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2023;142(2):371–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Declercq ER, Cabral HJ, Cui X, Liu CL, Amutah-Onukagha N, Larson E, Meadows A, Diop H. Using longitudinally linked data to measure severe maternal morbidity. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2022;139(2):165–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirai AH, Owens PL, Reid LD, Vladutiu CJ, Main EK. Trends in severe maternal morbidity in the US across the transition to ICD-10-CM/PCS from 2012–2019. JAMA Network Open 2022;5(7):e2222966–e2222966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan SJ, Thiel F, Kaimal AJ, Pitman RK, Orr SP, Dekel S. Validation of childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder using psychophysiological assessment. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022;227(4):656–659. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.05.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heyne CS, Kazmierczak M, Souday R, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of birth-related posttraumatic stress among parents: a comparative systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2022;94:102157. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yildiz PD, Ayers S, Phillips L. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy and after birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2017;208:634–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thiel F, Dekel S. Peritraumatic dissociation in childbirth-evoked posttraumatic stress and postpartum mental health. Arch Women’s Ment Health 2020;23:189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dekel S, Ein-Dor T, Berman Z, Barsoumian IS, Agarwal S, Pitman RK. Delivery mode is associated with maternal mental health following childbirth. Arch Women’s Mentl Health 2019; 22:817–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iyengar AS, Ein-Dor T, Zhang EX, Chan SJ, Kaimal AJ, Dekel S. Increased traumatic childbirth and postpartum depression and lack of exclusive breastfeeding in Black and Latinx individuals. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2022;158(3):759–761. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ertan D, Hingray C, Burlacu E, Sterlé A, El-Hage W. Post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth. BMC psychiatry 2021;21(155):1–9. 10.1186/s12888-021-03158-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dekel S, Ein-Dor T, Dishy GA, Mayopoulos PA. Beyond postpartum depression: posttraumatic stress-depressive response following childbirth. Arch Women’s Ment Health 2020;23(4):557–564. doi: 10.1007/s00737-019-01006-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayers S, Bond R, Bertullies S, Wijma K. The aetiology of post-traumatic stress following childbirth: a meta-analysis and theoretical framework. Psychol Med 2016;46(6):1121–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thiel F, Ein-Dor T, Dishy G, King A, Dekel S. Examining symptom clusters of childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder.Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2018;20(5):26912. doi: 10.4088/PCC.18m02322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cirino NH, Knapp JM. Perinatal posttraumatic stress disorder: a review of risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey 2019;74(6):369–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.James S. Women’s experiences of symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after traumatic childbirth: a review and critical appraisal. Arch Women’s Ment Health 2015;18(6):761–771. doi: 10.1007/s00737-015-0560-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ayers S, Harris R, Sawyer A, Parfitt Y, Ford E. Posttraumatic stress disorder after childbirth: analysis of symptom presentation and sampling. J Affective Disor 2009;119(1–3):200–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berman Z, Kaim A, Reed T, Felicione J, Hinojosa C, Oliver K, Rutherford H, Mayes L, Shin L, Dekel S. Amygdala response to traumatic childbirth recall is associated with impaired bonding behaviors in mothers with childbirth-related PTSD symptoms: preliminary findings. Biolog Psychiat 2020;87(9):S142. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stuijfzand S, Garthus-Niegel S, Horsch A. Parental birth-related PTSD symptoms and bonding in the early postpartum period: a prospective population-based cohort study. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:570727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dekel S, Thiel F, Dishy G, Ashenfarb AL. Is childbirth-induced PTSD associated with low maternal attachment? Arch Women’s Ment Health 2019;22(1):119–122. doi: 10.1007/s00737-018-0853-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayopoulos GA, Ein-Dor T, Dishy GA, Nandru R, Chan SJ, Hanley LE, Kaimal AJ, Dekel S. COVID-19 is associated with traumatic childbirth and subsequent mother-infant bonding problems. J Affect Disord 2021;282:122–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Sieleghem S, Danckaerts M, Rieken R, Okkerse JM, de Jonge E, Bramer WM, Lambregtse-van den Berg MP. Childbirth related PTSD and its association with infant outcome: A systematic review. Early Human Devel 2022;174:105667. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2022.105667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stramrood C, Slade P. 2017. A woman afraid of becoming pregnant again: posttraumatic stress disorder following childbirth. In: Paarlberg K., van de Wiel H. (eds) Bio-Psycho-Social Obstetrics and Gynecology. Springer, Cham. 10.1007/978-3-319-40404-2_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKenzie-McHarg K, Ayers S, Ford E, Horsch A, Jomeen J, Sawyer A, Stramrood C, Thomson G, Slade P. Post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth: an update of current issues and recommendations for future research. J Reproductive Infant Psychol 2015;33(3):219–237. 10.1080/02646838.2015.1031646 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garthus-Niegel S, Horsch A, Handtke E. et al. The impact of postpartum posttraumatic stress and depression symptoms on couples’ relationship satisfaction: a population-based prospective study. Front Psychol 2018;9:1728. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kranenburg L, Lambregtse-van den Berg M, and Stramrood C. Traumatic childbirth experience and childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a contemporary overview. Int J Environment Res and Public Health 2023;20(4):2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Söderquist J, Wijma B, Wijma K. The longitudinal course of post-traumatic stress after childbirth. J Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology 2006;27(2):113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vermetten E, Zhohar J, Krugers HJ. Pharmacotherapy in the aftermath of trauma; opportunities in the ‘golden hours.’ Curr Psychiatry Rep 2014;16(7):455. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0455-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Marle H. PTSD as a memory disorder. Eur J Psychotraumatology 2015;6(1):27633. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qi W, Gevonden M, Shalev A. Prevention of post-traumatic stress disorder after trauma: current evidence and future directions. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2016;18(2):20. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0655-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carmi L, Fostick L, Burshtein S, Cwikel-Hamzany S, Zohar J. PTSD treatment in light of DSM-5 and the “golden hours” concept. CNS Spectr. 2016;21(4):279–282. doi: 10.1017/S109285291600016X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gamble J, Creedy D. Content and processes of postpartum counseling after a distressing birth experience: a review. Birth. 2004;31(3):213–218. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.00307.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lapp LK, Agbokou C, Peretti CS, Ferreri F. Management of post traumatic stress disorder after childbirth: a review. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 2010;31(3):113–122. doi: 10.3109/0167482X.2010.503330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peeler S, Chung MC, Stedmon J, Skirton H. A review assessing the current treatment strategies for postnatal psychological morbidity with a focus on post-traumatic stress disorder. Midwifery 2013;29(4):377–388. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2012.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Furuta M, Horsch A, Ng ESW, Bick D, Spain D, Sin J. Effectiveness of trauma-focused psychological therapies for treating post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in women following childbirth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry 2018;9:591. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Graaff LF, Honig A, Van Pampus MG, Stramrood CAI. Preventing post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth and traumatic birth experiences: a systematic review. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2018;97(6):648–656. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Bruijn L, Stramrood CA, Lambregtse-van Den Berg MP, Rius Ottenheim N. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder following childbirth. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 2020;41(1):5–14. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2019.1593961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shorey S, Downe S, Chua JYX, Byrne SO, Fobelets M, Lalor JG. Effectiveness of psychological interventions to improve the mental well-being of parents who have experienced traumatic childbirth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse 2023;24(3):1238–1253. doi: 10.1177/15248380211060808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor Miller PG, Sinclair M, Gillen P, et al. Early psychological interventions for prevention and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and post-traumatic stress symptoms in post-partum women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sar V, ed. PLOS ONE 2021;16(11):e0258170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slade PP, Molyneux DR, Watt DA. A systematic review of clinical effectiveness of psychological interventions to reduce post traumatic stress symptoms following childbirth and a meta-synthesis of facilitators and barriers to uptake of psychological care. J Affect Disord 2021;281:678–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52(6):377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, for the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339(Jul21 1):b2535–b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xie T, Brouwer RW, van den Akker-Scheek I, van der Veen HC. Clinical relevance of joint line obliquity after high tibial osteotomy for medial knee osteoarthritis remains controversial: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2023. Jun 20. doi: 10.1007/s00167-023-07486-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trac MH, McArthur E, Jandoc R, et al. Macrolide antibiotics and the risk of ventricular arrhythmia in older adults. Can Med Assoc J 2016;188(7):E120–E129. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corso LML, Macdonald HV, Johnson BT, et al. Is concurrent training efficacious antihypertensive therapy? A meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2016;48(12):2398–2406. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bastos MH, Furuta M, Small R, McKenzie-McHarg K, Bick D. Debriefing interventions for the prevention of psychological trauma in women following childbirth. Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007194.pub2; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Phillips S. Debriefing following traumatic childbirth. Br J Midwifery 2003;11:725–730. 10.12968/bjom.2003.11.12.11866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Selkirk R, McLaren S, Ollerenshaw A, McLachlan AJ, Moten J. The longitudinal effects of midwife-led postnatal debriefing on the psychological health of mothers. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2006;24(2):133–147. doi: 10.1080/02646830600643916 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Priest SR, Henderson J, Evans SF, Hagan R. Stress debriefing after childbirth: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust 2003;178(11):542–545. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05355.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abdollahpour S, Khosravi A, Motaghi Z, Keramat A, Mousavi SA. Effect of brief cognitive behavioral counseling and debriefing on the prevention of post-traumatic stress disorder in traumatic birth: a randomized clinical trial. Community Ment Health J 2019;55(7):1173–1178. doi: 10.1007/s10597-019-00424-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kershaw K, Jolly J, Bhabra K, Ford J. Randomised controlled trial of community debriefing following operative delivery. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2005;112(11):1504–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00723.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meades R, Pond C, Ayers S, Warren F. Postnatal debriefing: have we thrown the baby out with the bath water? Behav Res Ther 2011;49(5):367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jotzo M, Poets CF. Helping parents cope with the trauma of premature birth: an evaluation of a trauma-preventive psychological intervention. Pediatrics 2005;115(4):915–919. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ayers S, McKenzie-McHarg K, Eagle A. Cognitive behaviour therapy for postnatal post-traumatic stress disorder: case studies. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol 2007;28(3):177–184. doi: 10.1080/01674820601142957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shaw RJ, St John N, Lilo EA, et al. Prevention of traumatic stress in mothers with preterm infants: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 2013;132(4):e886–e894. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shaw RJ, St John N, Lilo E, et al. Prevention of traumatic stress in mothers of preterms: 6-month outcomes. Pediatrics 2014;134(2):e481–e488. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Simon S, Moreyra A, Wharton E, et al. Prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder in mothers of preterm infants using trauma-focused group therapy: Manual development and evaluation. Early Hum Dev 2021;154:105282. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sjömark J, Svanberg AS, Larsson M, et al. Effect of internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy among women with negative birth experiences on mental health and quality of life - a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022;22(1):835. doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-05168-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nieminen K, Berg I, Frankenstein K, et al. Internet-provided cognitive behaviour therapy of posttraumatic stress symptoms following childbirth—a randomized controlled trial. Cognitive Behav Therapy 2016;45(4):287–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chiorino V, Cattaneo MC, Macchi EA, et al. The EMDR Recent Birth Trauma Protocol: a pilot randomised clinical trial after traumatic childbirth. Psychol Health 2020;35(7):795–810. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2019.1699088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sandström M, Wiberg B, Wikman M, Willman AK, Högberg U. A pilot study of eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing treatment (EMDR) for post-traumatic stress after childbirth. Midwifery 2008;24(1):62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2006.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kranenburg LW, Bijma HH, Eggink AJ, Knijff EM, Lambregtse-van Den Berg MP. Implementing an Eye Movement and Desensitization Reprocessing treatment-program for women with posttraumatic stress disorder after childbirth. Front Psychol 2022;12:797901. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.797901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Qian J, Zhou X, Sun X, Wu M, Sun S, Yu X. Effects of expressive writing intervention for women’s PTSD, depression, anxiety and stress related to pregnancy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychiatry Res 2020. Jun;288:112933. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thompson-Hollands J, Marx BP, Sloan DM. Brief novel therapies for PTSD: written exposure therapy. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry 2019;6(2):99–106. doi: 10.1007/s40501-019-00168-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Di Blasio P, Ionio C. Childbirth and narratives: how do mothers deal with their child’s birth? J Prenat Perinat Psychol Heal 2002;17(2):143–151. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Di Blasio P, Ionio C, Confalonieri E. Symptoms of postpartum PTSD and expressive writing: a prospective study. J Prenat Perinat Psychol Heal 2009;24:49–66. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Di Blasio P, Miragoli S, Camisasca E, Di Vita AM, Pizzo R, Pipitone L. Emotional distress following childbirth: an intervention to buffer depressive and PTSD symptoms. Eur J Psychol 2015;11(2):214–232. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v11i2.779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Di Blasio P, Camisasca E, Caravita SCS, Ionio C, Milani L, Valtolina GG. The effects of expressive writing on postpartum depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Psychol Rep 2015;117(3):856–882. doi: 10.2466/02.13.PR0.117c29z3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Horsch A, Tolsa JF, Gilbert L, Du Chêne LJ, Müller-Nix C, Graz MB. Improving maternal mental health following preterm birth using an expressive writing intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2016;47(5):780–791. doi: 10.1007/s10578-015-0611-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barry LM, Singer GHS. Reducing maternal psychological distress after the NICU experience through journal writing. J Early Interv. 2001;24(4):287–297. doi: 10.1177/105381510102400404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Navidian A, Saravani Z, Shakiba M. Impact of psychological grief counseling on the severity of post-traumatic stress symptoms in mothers after stillbirths. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2017. Aug;38(8):650–654. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2017.1315623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alder J, Stadlmayr W, Tschudin S, Bitzer J. Posttraumatic symptoms after childbirth: what should we offer? J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2006. Jun;27(2):107–12. doi: 10.1080/01674820600714632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bahari S, Nourizadeh R, Esmailpour K, Hakimi S. The effect of supportive counseling on mother psychological reactions and mother–infant bonding following traumatic childbirth. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2022;43(5):447–454. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2021.1993388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Asadzadeh L, Jafari E, Kharaghani R, Taremian F. Effectiveness of midwife-led brief counseling intervention on post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety symptoms of women experiencing a traumatic childbirth: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):142. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-2826-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gamble J, Creedy D, Moyle W, Webster J, McAllister M, Dickson P. Effectiveness of a counseling intervention after a traumatic childbirth: a randomized controlled trial. Birth 2005;32(1):11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2005.00340.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ryding EL, Wijma K, Wijma B. Postpartum counselling after an emergency cesarean. Clin Psychol Psychother 1998;5(4):231–237. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ryding EL, Wiren E, Johansson G, Ceder B, Dahlstrom AM. Group counseling for mothers after emergency Cesarean section: a randomized controlled trial of intervention. Birth 2004;31(4):247–253. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.00316.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Loh AHY, Ong LL, Yong FSH, Chen HY. Improving mother-infant bonding in postnatal depression - the SURE MUMS study. Asian J Psychiatr 2023. Mar;81:103457. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bieleninik Ł, Lutkiewicz K, Cieślak M, Preis-Orlikowska J, Bidzan M. Associations of maternal-infant bonding with maternal mental health, infant’s characteristics and socio-demographical variables in the early postpartum period: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(16):8517. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Phillips R. The sacred hour: uninterrupted skin-to-skin contact immediately after birth. Newborn Infant Nurs Rev 2013;13(2):67–72. doi: 10.1053/j.nainr.2013.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Abdollahpour S, Khosravi A, Bolbolhaghighi N. The effect of the magical hour on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in traumatic childbirth: a clinical trial. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2016;34(4):403–412. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2016.1185773 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Borghini A, Habersaat S, Forcada-Guex M, et al. Effects of an early intervention on maternal post-traumatic stress symptoms and the quality of mother–infant interaction: The case of preterm birth. Infant Behav Dev 2014;37(4):624–631. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2014.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zelkowitz P, Feeley N, Shrier I, et al. The Cues and Care randomized controlled trial of a neonatal intensive care unit intervention: effects on maternal psychological distress and mother-infant interaction. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2011;32(8):591–599. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318227b3dc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kahalon R, Preis H, Benyamini Y. Mother-infant contact after birth can reduce postpartum post-traumatic stress symptoms through a reduction in birth-related fear and guilt. J Psychosom Res 2022;154:110716. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2022.110716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schlesinger Y, Hamiel D, Rousseau S, et al. Preventing risk for posttraumatic stress following childbirth: Visual biofeedback during childbirth increases maternal connectedness to her newborn thereby preventing risk for posttraumatic stress following childbirth. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy 2022;14(6):1057–1065. doi: 10.1037/tra0000558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Horsch A, Vial Y, Favrod C, et al. Reducing intrusive traumatic memories after emergency caesarean section: a proof-of-principle randomized controlled study. Behav Res Ther 2017;94:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Deforges C, Fort D, Stuijfzand S, Holmes EA, Horsch A. Reducing childbirth-related intrusive memories and PTSD symptoms via a single-session behavioural intervention including a visuospatial task: a proof-of-principle study. J Affect Disord 2022;303:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Iyadurai L, Blackwell S, Meiser-Stedman R. et al. Preventing intrusive memories after trauma via a brief intervention involving Tetris computer game play in the emergency department: a proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. Mol Psychiatry 2018;23:674–682. 10.1038/mp.2017.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kavanagh DJ, Freese S, Andrade J, May J. Effects of visuospatial tasks on desensitization to emotive memories. Br J Clin Psychol 2001;40(3):267–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Andrade J, Kavanagh D, Baddeley A. Eye-movements and visual imagery: A working memory approach to the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Br J Clinical Psychol. 1997;36(Pt 2):209–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. ISBN: 9789241549912. WHO Reference Number: WHO/RHR/16.12 (Executive summary) Accessible at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549912 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gagnon AJ, Sandall J. Individual or group antenatal education for childbirth or parenthood, or both. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007; 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Spinelli A, Baglio G, Donati S, Grandolfo ME, Osborn J. Do antenatal classes benefit the mother and her baby? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2003;13(2):94–101. doi: 10.1080/jmf.13.2.94.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ahmadpour P, Moosavi S, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Jahanfar S, Mirghafourvand M. Effect of implementing a birth plan on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):862. doi: 10.1186/s12884-022-05199-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gökçe İsbir G, İnci F, Önal H, Yıldız PD. The effects of antenatal education on fear of childbirth, maternal self-efficacy and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms following childbirth: an experimental study. Appl Nurs Res 2016;32:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2016.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Slade P, West H, Thomson G, et al. STRAWB2 (Stress and Wellbeing After Childbirth): a randomised controlled trial of targeted self-help materials to prevent post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2020;127(7):886–896. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Astill Wright L, Sijbrandij M, Sinnerton R, Lewis C, Roberts NP, Bisson JI. 2019. Pharmacological prevention and early treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Translational Psychiatry 2019;9(1):334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Roberts NP, Kitchiner NJ, Kenardy J, Lewis CE, Bisson JI. Early psychological intervention following recent trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatology 2019;10(1):1695486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Watkins LE, Sprang KR, Rothbaum BO. Treating PTSD: a review of evidence-based psychotherapy interventions. Front Behav Neurosci 2018;12:258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Varker T, Jones KA, Arjmand HA, Hinton M, Hiles SA, Freijah I, Forbes D, Kartal D, Phelps A, Bryant RA, McFarlane A. Dropout from guideline-recommended psychological treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord Rep 2021;4:100093. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lewis C. Dropout from psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatology 2020;11(1):1709709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Schottenbauer M. Nonresponse and dropout rates in outcome studies on PTSD: review and methodological considerations. Psychiatry 2008;71(2):134–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fonzo GA, Federchenco V, Lara A. Predicting and managing treatment non-response in posttraumatic stress disorder. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry 2020. Jun;7(2):70–87. doi: 10.1007/s40501-020-00203-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dekel S, Gilbertson M, Orr S, Rauch S, Wood N, Pitman R. Chapter 34 - Trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Massachusetts Gen Hosp Compr Clin Psychiatry 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Koek RJ, Schwartz HN, Scully S, Langevin JP, Spangler S, Korotinsky A, Jou K, Leuchter A. Treatment-Refractory Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (TRPTSD): a review and framework for the future. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2016;70:170–218. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Glazer KB, Howell EA. A way forward in the maternal mortality crisis: addressing maternal health disparities and mental health. Arch Womens Ment Health 2021;24:823–830. 10.1007/s00737-021-01161-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Joseph KS, Boutin A, Lisonkova S, Muraca GM, Razaz N, John S, Mehrabadi A, Sabr Y, Ananth CV, Schisterman E. Maternal mortality in the United States: recent trends, current status, and future considerations. Obstet Gynecol 2021;137(5):763–771. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Norhayati MN, Hazlina NN, Asrenee AR, Emilin WW. Magnitude and risk factors for postpartum symptoms: a literature review. J Affect Disord 2015;175:34–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Voit FAC, Kajantie E, Lemola S, Räikkönen K, Wolke D, Schnitzlein DD. Maternal mental health and adverse birth outcomes. Böckerman P, ed. PLOS ONE. 2022;17(8):e0272210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Knapp M, Wong G. Economics and mental health: the current scenario. World Psychiatry 2020;19(1):3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Luca DL, Garlow N, Staatz C, Margiotta C, Zivin K. Societal costs of untreated perinatal mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Mathematica 2019. Apr: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Grekin R, O’Hara MW. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis. Clinic Psychol Rev 2014;34(5):389–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jagodnik KM, Ein-Dor T, Chan SJ, Ashkenazy AT, Bartal A, Dekel S. Screening for post-traumatic stress disorder following childbirth using the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory. medRxiv 2023. doi: 10.1101/2023.04.23.23288976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lang AJ. Mindfulness in PTSD treatment. Curr Opinion Psychology 2017;14:40–43. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bisson JI, van Gelderen M, Roberts NP, Lewis C. Non-pharmacological and non-psychological approaches to the treatment of PTSD: results of a systematic review and meta-analyses. Eur J Psychotraumatology 2020;11(1):1795361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Brown RL, Wood A, Carter JD, Kannis-Dymand L. The metacognitive model of post-traumatic stress disorder and metacognitive therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. Clin Psychology & Psychotherapy 2022;29(1):131–146. 10.1002/cpp.2633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Babu MS, Chan SJ, Ein-Dor T, Dekel S. 2022. Traumatic childbirth during COVID-19 triggers maternal psychological growth and in turn better mother-infant bonding. J Affective Disord, 313:163–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.06.076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Rashidi M, Maier E, Dekel S, et al. Peripartum effects of synthetic oxytocin: the good, the bad, and the unknown. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2022;141:104859. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table 1. Descriptions of clinical trials for interventions to prevent or treat childbirth-related maternal PTSD

Appendix A: Modified Downs and Black Checklist used in this systematic review.