Abstract

A representative sample of 21 Salmonella typhi strains isolated from cultures of blood from patients at the Christian Medical College and Hospital, Vellore, India, were tested for their susceptibilities to various antimicrobial agents. Eleven of the S. typhi strains possessed resistance to chloramphenicol (256 mg/liter), trimethoprim (64 mg/liter), and amoxicillin (>128 mg/liter), while four of the isolates were resistant to each of these agents except for amoxicillin. Six of the isolates were completely sensitive to all of the antimicrobial agents tested. All the S. typhi isolates were susceptible to cephalosporin agents, gentamicin, amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid, and imipenem. The antibiotic resistance determinants in each S. typhi isolate were encoded by one of four plasmid types. Plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance genes were identified with specific probes in hybridization experiments; the genes responsible for chloramphenicol, trimethoprim, and ampicillin resistance were chloramphenicol acetyltransferase type I, dihydrofolate reductase type VII, and TEM-1 β-lactamase, respectively. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis of XbaI-generated genomic restriction fragments identified a single distinct profile (18 DNA fragments) for all of the resistant isolates. In comparison, six profiles, different from each other and from the resistance profile, were recognized among the sensitive isolates. It appears that a single strain containing a plasmid conferring multidrug-resistance has emerged within the S. typhi bacterial population in Vellore and has been able to adapt to and survive the challenge of antibiotics as they are introduced into clinical medicine.

Typhoid fever is distressingly prevalent in developing countries, where it remains a major health problem (3, 39). The annual global incidence of this disease has been estimated to be 21 million cases, with more than 700,000 deaths (36). Infection with Salmonella typhi, the causative organism of this disease, requires effective antimicrobial chemotherapy in order to reduce mortality (8). Chloramphenicol was the “gold standard” agent for the treatment of this infection (17), but with the emergence of chloramphenicol-resistant strains, ampicillin and trimethoprim were considered suitable alternatives (8). Since 1989, however, multidrug-resistant (MDR) S. typhi strains that are no longer susceptible to these three first-line antibiotics have emerged (18, 37). Indeed, these MDR S. typhi strains have become a serious problem globally and have been reported not only in the Indian subcontinent but also in Latin America, Egypt, Nigeria, China, Korea, Vietnam, and the Philippines (27). As a result, the potential of other antimicrobial agents including broad-spectrum cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones for the treatment of typhoid fever have been investigated (13, 21).

Antibiotic resistance in S. typhi is often plasmid mediated. In particular, resistance to chloramphenicol, ampicillin, trimethoprim, sulfonamides, and tetracycline is often encoded by plasmids belonging to the incompatibility complex group IncHI (31). These plasmids are large (∼180 kb) and conjugative and originate from Southeast Asia (16, 37).

Until recently, it had been suggested that, with few exceptions, S. typhi represented a single clone with little intraspecies divergence (29). New molecular biology-based techniques, however, in particular pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), are extremely discriminatory and indicate genetic heterogeneity among S. typhi isolates (24, 35, 36). Use of this technique for the fingerprinting of each strain provides a tool that can successfully be used in the epidemiological investigation of S. typhi outbreaks.

Between 1990 and 1994 MDR S. typhi strains with reduced susceptibilities to the fluoroquinolones (4) were isolated in Vellore, in southern India, as the cause of epidemic typhoid. Concurrently, chloramphenicol-sensitive S. typhi strains continued to be isolated, suggesting that both varieties are endemic (19). This unusual phenomenon prompted this investigation. In this paper, the antibiotic resistance levels in S. typhi are reported, the genes associated with the antibiotic resistance are identified, and the isolates are typed at the molecular level and compared with a coexisting subpopulation of chloramphenicol-sensitive S. typhi.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

S. typhi strains were isolated at the Christian Medical College and Hospital, Vellore, India, between 1992 and 1994. MDR S. typhi strains were defined as those strains possessing chloramphenicol, ampicillin, and trimethoprim resistance. Each isolate was confirmed as being S. typhi with API 20E test strips (BióMerieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France).

Sensitivity testing.

The MICs of chloramphenicol, trimethoprim, amoxicillin, amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid, cefotaxime, and imipenem were determined as described previously (25). For antibiogram analysis the same method as that used for the MIC determinations was used, except that a fixed concentration of antimicrobial agent was incorporated into the Iso-Sensitest agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) plates.

PFGE.

Genomic DNA was prepared as described by Butler et al. (5). DNA restricted with XbaI (TCTAGA) was separated by PFGE by using a CHEF DR II system (Bio-Rad) at 14°C for 22 h at 200 V with a pulse time of 1 to 60 s. The similarity between two restriction fragment length polymorphisms was scored with the coefficient of similarity (F) or the Dice coefficient (9), in which an F value of 1.0 indicates that two isolates have identical PFGE patterns.

Conjugational transfer of drug resistance and plasmid analysis.

Conjugation experiments with the MDR S. typhi strains were performed by the method of Amyes and Gould (2). The conjugations were performed for 18 h at 28 and 37°C. Plasmids were isolated by a modification of the method described by Takahashi and Nagano (34). The plasmid DNA was digested for 2 h at 37°C with 10 U of EcoRI restriction endonuclease according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Gibco BRL, Paisley, United Kingdom). A repeat digest of this plasmid DNA was performed under the same conditions described above but with 10 U of MluI restriction endonuclease (Gibco BRL). MluI was chosen specifically because this restriction enzyme does not cut within the TEM-1, dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) type VII, or the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase type I (CAT-I) gene. The digested DNA was analyzed in each case by electrophoresis on a 0.6% agarose gel at 50 V for 21 h.

DNA hybridizations.

Dot blots and Southern blots of the plasmid DNA from the transconjugants were prepared on a transfer membrane (Hybond N+) as instructed by the manufacturer (Amersham International plc, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Control plasmids encoding the type Ia, Ib, V, and VII DHFRs (1) and CAT-I, -II, and -III (all provided by Kevin Towner, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom), and plasmids R1 (14) and R1010 (28) encoding the TEM-1 and SHV-1 β-lactamases, respectively, were used.

Oligonucleotide probes for distinguishing between different DHFR genes were used as described by Adrian et al. (1). A heterogeneous sequence that occurs throughout the same region of the CAT-I, -II, and -III genes was selected for the construction of a 30-base oligonucleotide probe specific for the CAT-I gene, as follows: 5′-TATGTGTAGAAACTGCCGGAAATCGTCGTG. This probe was tested for homology with other DNA sequences in the GenBank database. A TEM-1 gene probe was prepared from a TEM-derived PCR product generated with oligonucleotide primers described previously (6). Hybridizations were carried out with either an ECL 3′ oligo labelling kit or a random prime labelling and detection kit according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Amersham International plc). Stringency washes were performed as described previously (15).

β-Lactamase analysis.

β-Lactamases from the transconjugants were isolated and investigated by isoelectric focusing and biochemical analysis as described elsewhere (25).

PCR amplification for incompatibility testing.

A 365-bp region of the RepHI1A replicon was amplified from plasmid DNA by use of a Taq polymerase kit obtained from Gibco BRL. The final volume in the tubes for amplification was 100 μl and consisted of 10× Taq PCR buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 200 μM, 10 pmol of each primer (5′-GGTCCAACCCATTGCTTTAC and 5′-CACGGAAAGAAATCACAAC, as recommended by Gabant et al. [11] and purchased from Oswel DNA Service, University of Southampton), 0.1 μg of DNA, and 2 U of Taq polymerase. The amplification reaction, conducted in a Techne thermocycler, consisted of 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. A final extension step ran at 72°C for 10 min.

RESULTS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 21 S. typhi isolates from Vellore, India, were investigated in the study: 15 MDR S. typhi strains and 6 chloramphenicol-sensitive S. typhi strains.

Antimicrobial sensitivity testing.

As determined previously (4), none of the isolates were clinically resistant to ciprofloxacin. All of the chloramphenicol-sensitive S. typhi strains were sensitive to all the antimicrobial agents tested, namely, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim, amoxicillin, amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid, cefotaxime, and imipenem (Table 1). In contrast, all of the MDR isolates were resistant to chloramphenicol (MIC, 256 mg/liter) and trimethoprim (MIC, 64 mg/liter). Resistance to ampicillin (MIC, >128 mg/liter) was detected in 11 of these isolates; isolates ST3, ST5, ST7, and ST12 were sensitive to this agent. All the isolates were susceptible to amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid, cefotaxime, and imipenem.

TABLE 1.

MICs of a range of antibiotics for MDR and chloramphenicol-sensitive S. typhi strains

| Strain type and no. | MIC (mg/liter)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chloramphenicol | Trimethoprim | Amoxicillin | Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | Cefotaxime | Imipenem | |

| Range of MICs | 0.25–128 | 0.032–32 | 0.25–128 | 0.25–128 | 0.004–128 | 0.125–32 |

| MDR isolates | ||||||

| ST1 | >128 | >32 | >128 | 4 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| ST2 | >128 | >32 | >128 | 4 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| ST3 | >128 | >32 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| ST4 | >128 | >32 | >128 | 4 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| ST5 | >128 | >32 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| ST6 | >128 | >32 | >128 | 4 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| ST7 | >128 | >32 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| ST8 | >128 | >32 | >128 | 4 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| ST9 | >128 | >32 | >128 | 4 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| ST10 | >128 | >32 | >128 | 4 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| ST11 | >128 | >32 | >128 | 4 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| ST12 | >128 | >32 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| ST13 | >128 | >32 | >128 | 4 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| ST14 | >128 | >32 | >128 | 4 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| ST15 | >128 | >32 | >128 | 4 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| Chloramphenicol-sensitive isolates | ||||||

| ST45 | 2 | 0.0625 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| ST46 | 2 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0312 | 0.125 |

| ST48 | 2 | 0.0625 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0312 | 0.125 |

| ST49 | 2 | 0.0312 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0312 | 0.125 |

| ST51 | 2 | 0.0625 | 1 | 1 | 0.0625 | 0.125 |

| ST52 | 2 | 0.0312 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0312 | 0.125 |

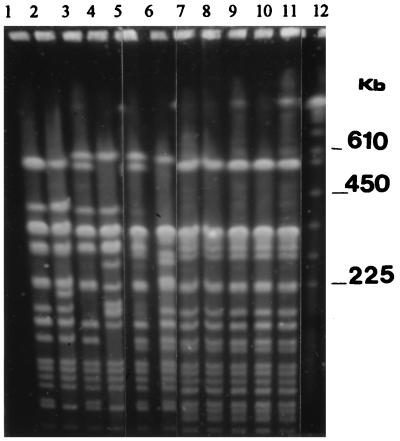

Molecular typing.

After digestion of the chromosomal DNA from each of the MDR S. typhi strains with XbaI, a single restriction endonuclease analysis (REA) pattern, which consisted of 18 distinct DNA fragments, was generated by PFGE (Fig. 1). In contrast, after digestion of the chromosomal DNA of the chloramphenicol-sensitive S. typhi strains with XbaI, six separate REA patterns were produced by PFGE (Fig. 1). The F values for these isolates were found to range between 0.68 and 0.93. When compared with the MDR S. typhi profile, the F values of each of the chloramphenicol-sensitive S. typhi isolates ranged from 0.66 to 0.88. Each REA pattern produced by PFGE was confirmed to be stable and reproducible with repeated digestion of the genomic DNA preparations.

FIG. 1.

PFGE of XbaI-digested chloramphenicol-sensitive and representative MDR S. typhi strains. Lanes: 1, ST45; 2, ST46; 3, ST48; 4, ST49; 5, ST51; 6, ST52; 7, ST1; 8, ST2; 9, ST3; 10, ST4; 11, ST5; 12, Saccharomyces cerevisiae standard.

Conjugational transfer of drug resistance and plasmid analysis.

Sensitivity testing identified all of the MDR isolates as trimethoprim resistant. This agent was therefore used for selection in the conjugation studies. It is established that the transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in Salmonella spp. occurs more readily at lower temperatures. It was not surprising, therefore, that each strain exhibited the ability to transfer trimethoprim resistance into Escherichia coli J62-2 at 28°C (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

S. typhi isolations, antibiogram profiles, and transfer of resistance determinants into E. coli J62-2

| Strain no. | Yr of isolation | Temp (°C) of transfer into E. coli J62-2 | Plasmid group | Transferable resistance determinantsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST1 | 1994 | 28 | B | Cm Tp Ap Sm Sx Tc Sp |

| ST2 | 1994 | 28 | B | Cm Tp Ap Sm Sx Tc Sp |

| ST3 | 1992 | 28 and 37 | C | Cm Tp Tc Sp |

| ST4 | 1994 | 28 and 37 | B | Cm Tp Ap Sm Sx Tc Sp |

| ST5 | 1992 | 28 | C | Cm Tp Tc Sp |

| ST6 | 1994 | 28 | B | Cm Tp Ap Sm Sx Tc Sp |

| ST7 | 1993 | 28 | D | Cm Tp Tc Sp |

| ST8 | 1994 | 28 and 37 | B | Cm Tp Ap Sm Sx Tc Sp |

| ST9 | 1994 | 28 and 37 | A | Cm Tp Ap Sm Sx Tc Sp |

| ST10 | 1994 | 28 and 37 | A | Cm Tp Ap Sm Sx Tc Sp |

| ST11 | 1994 | 28 and 37 | B | Cm Tp Ap Sm Sx Tc Sp |

| ST12 | 1992 | 28 and 37 | C | Cm Tp Tc Sp |

| ST13 | 1994 | 28 | B | Cm Tp Ap Sm Sx Tc Sp |

| ST14 | 1994 | 28 | D | Cm Tp Tc Sp |

| ST15 | 1994 | 28 and 37 | B | Cm Tp Ap Sm Sx Tc Sp |

| ST45 | 1993 | |||

| ST46 | 1993 | |||

| ST48 | 1994 | |||

| ST49 | 1994 | |||

| ST51 | 1994 |

The MICs of chloramphenicol (Cm; MIC, 128 mg/liter); trimethoprim (Tp; MIC, 128 mg/liter), and ampicillin (Ap; MIC, 128 mg/liter) were determined. Breakpoint values for streptomycin (Sm; 10 mg/liter), sulfamethoxazole (Sx; 32 mg/liter), tetracycline (Tc; 8 mg/liter), and spectinomycin (Sp; 10 mg/liter) were determined.

For each of the 15 transconjugants, the MICs of chloramphenicol and trimethoprim were 128 mg/liter. For 10 of the transconjugants amoxicillin MICs were 128 mg/liter. The plasmids which originated in ST3, ST5, ST7, and ST12 possessed no resistance to amoxicillin. Interestingly, ST14, which was amoxicillin resistant, contained a plasmid encoding no resistance to this agent. As determined by the breakpoint value, all the transconjugants were resistant to tetracycline and spectinomycin, and in addition, the amoxicillin-resistant transconjugants also possessed resistance to sulfamethoxazole and streptomycin (Table 2).

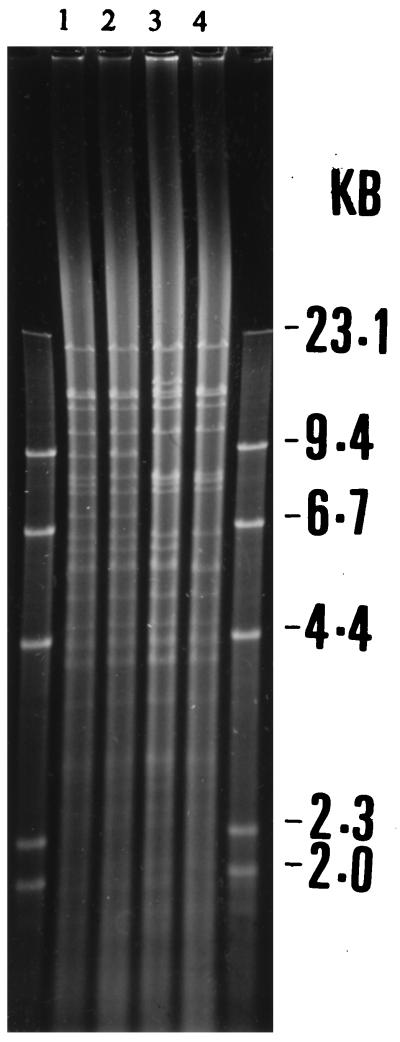

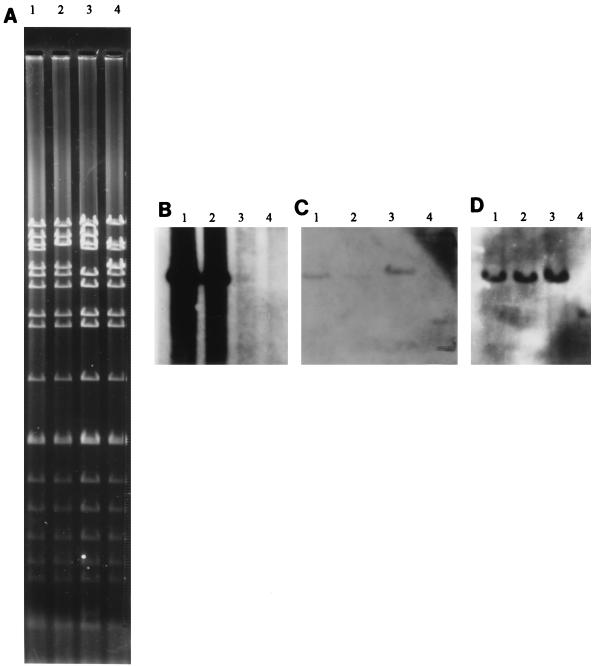

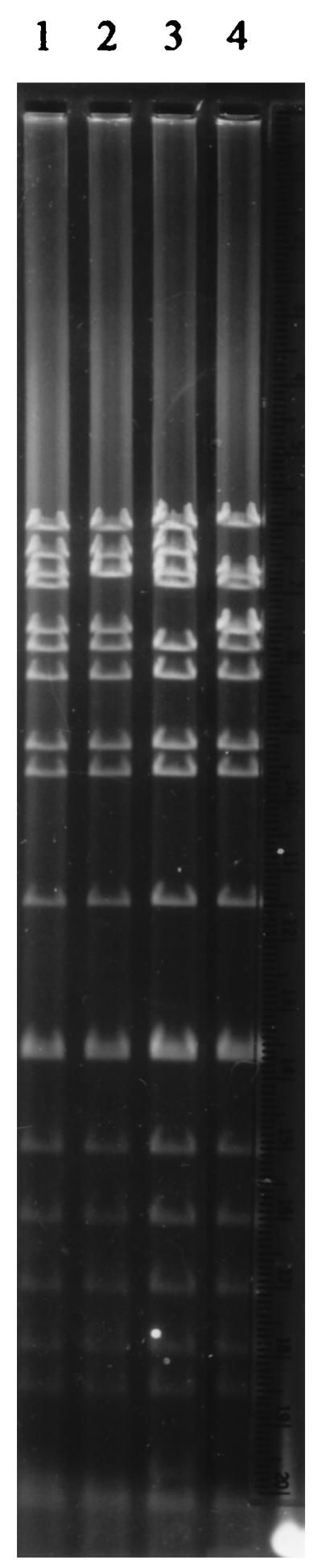

Among the 15 plasmids, four different plasmid profiles were identified after digestion with the EcoRI restriction endonuclease (Fig. 2). Plasmids with identical restriction fragment length polymorphisms were allocated to the same group. Digestion with the MluI restriction endonuclease (Fig. 3) confirmed the presence of four plasmid groups designated groups A to D. Two plasmids, 160 kb in size, were present in group A. These plasmids originated in strains isolated in 1994. Group B contained eight plasmids which were calculated as being 150 kb in size, and all originated in strains isolated in 1994. The three plasmids in group C, all originating in strains isolated in 1992, were 170 kb and mediated no resistance to ampicillin. Finally, two plasmids were allocated to group D and were calculated as being 140 kb in size. These plasmids originated in strains isolated in 1993 and 1994 and, like group C, did not mediate resistance to ampicillin (Table 2).

FIG. 2.

DNA from representative plasmids restricted with EcoRI on a 0.6% agarose gel. Lanes: 1, group A; 2, group B; 3, group D; 4, group C.

FIG. 3.

DNA from representative plasmids restricted with MluI on a 0.6% agarose gel. Lanes: 1, group A; 2, group B; 3, group D; 4, group C.

Gene detection.

Isoelectric focusing of each of the β-lactamase preparations from the ampicillin-resistant transconjugants identified the presence of an enzyme that cofocused with the TEM-1 β-lactamase control at a pI value of 5.4. No extended-spectrum activity was possessed, as established by hydrolysis assays. Positive plasmid DNA dot blot hybridizations with a TEM-1 gene probe confirmed its presence (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

DNA from representative plasmids restricted with the MluI restriction endonuclease on a 0.6% agarose gel (A). Southern blots, prepared from panel A, show the DNA fragments from representative plasmids which hybridized to the TEM-1 β-lactamase gene probe (B), the type VII DHFR oligonucleotide probe (C), and the CAT-I oligonucleotide probe (D). Lanes: 1, plasmid group A; 2, plasmid group B; 3, plasmid group D; 4, plasmid group C.

DNA dot blot hybridizations with the DHFR and CAT oligonucleotide probes indicated that each plasmid, regardless of the restriction endonuclease profile, encoded the dfrVII and the cat-1 genes, respectively. Southern blots of each plasmid digested with the MluI restriction endonuclease indicated that for each of the four different plasmid types, the two oligonucleotide probes and the gene probe all positively hybridized to DNA fragments of the same size (Fig. 4B and C). None of the group C or group D plasmids possessed ampicillin resistance, and correspondingly, there was no hybridization with the TEM-1 gene probe (Fig. 4A).

Incompatibility group testing.

The incompatibility group of the plasmids isolated from each of the transconjugants was determined by PCR. In each case, a 365-bp region of the RepHI1A replicon was amplified, providing evidence that each transconjugant contained a plasmid belonging to incompatibility group IncHI1.

DISCUSSION

There has been increasing concern about the prevalence of MDR S. typhi strains that are insusceptible to chloramphenicol, ampicillin, and trimethoprim (23, 38). Indeed there is an urgent need to examine the status of resistant S. typhi so that a rational approach to therapy may be adopted. In this study, we investigated 21 S. typhi isolates, obtained from patients with typhoid fever in Vellore, India, between 1992 and 1994. MIC determinations indicated that 15 of the isolates were resistant to chloramphenicol and trimethoprim. While high-level resistance to ampicillin predominated among 11 S. typhi strains, strains ST3, ST5, ST7, and ST12 were completely sensitive to this agent. It has been suggested that the emergence of chloramphenicol-resistant strains of S. typhi may be a result of the indiscriminate use of this agent and the use of this agent in irrational combinations (32). This is also the probable explanation for the emergence of trimethoprim and ampicillin resistance.

In response to the emergence of multiantibiotic-resistant S. typhi, a number of studies have investigated the efficacies of newer compounds including expanded-spectrum cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones (13, 21). Specifically, ceftriaxone has been very successful, with low rates of fever relapse, but this agent, like other expanded-spectrum cephalosporins, including cefotaxime and ceftazidime, is hindered by its expense and the need for parenteral administration (26). The MIC results in the current investigation revealed that S. typhi is sensitive to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins, suggesting that, at present, these drugs may remain clinically effective. It should be remembered, however, that the appearance in other gram-negative species of extended-spectrum β-lactamases possessing resistance to the later cephalosporins was a direct result of the extensive use of these agents in the hospital environment (7).

Studies investigating clinical isolates of S. typhi in Vellore suggest the coexistence of two populations of organisms: those which are chloramphenicol sensitive and those which are MDR (19). The epidemiology of these MDR S. typhi strains was elucidated after PFGE, which allows differentiation of the strains. In this study, XbaI, an enzyme that recognizes the rare tetranucleotide CTAG which is counterselected in many bacterial genomes, was used (30). In previous studies that have investigated S. typhi strain variation, this enzyme has been used and has produced clear REA patterns with approximately 20 fragments. Furthermore, these studies have established that sporadic outbreaks of typhoid fever are associated with heterogeneous isolates of S. typhi (24, 36). In the current study, a single REA pattern of 18 fragments was identified in all the MDR isolates, indicating the clonal spread of this resistant strain of S. typhi through the community in Vellore. Interestingly, genetic variation clearly existed between MDR S. typhi isolates and the S. typhi isolates from the chloramphenicol-sensitive subpopulation. It is unclear if this MDR strain type has a particular predisposition for the acquisition of plasmids encoding antibiotic resistance genes.

Previous studies have revealed plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance in S. typhi (10, 12, 20, 22, 37). Similarly, in the current investigation each of these resistance determinants was transferable to a standard laboratory host strain. More recent reports suggest that these plasmids, which belong to the IncHI incompatibility group, frequently encode resistance to chloramphenicol, trimethoprim, ampicillin, sulfonamides, and tetracyclines, and have been estimated as being between 110 and 120 mDa (165 and 180 kb) (37). The plasmids detailed in the current investigation were also found to belong to the IncHI group, specifically IncHI1, and were calculated as being between 140 and 170 kb.

This is the first investigation which has identified the particular genes responsible for plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance in S. typhi. The identification of a TEM-1 group β-lactamase as the determinant of β-lactam resistance in the S. typhi isolates is perhaps not surprising because this β-lactamase has been found extensively among other clinical isolates. The clinical implications of the presence of TEM-1 is of concern because this β-lactamase is recognized as the progenitor to many extended-spectrum β-lactamases and inhibitor-resistant β-lactamases.

Because of the high degree of homology found in the conserved regions of the DHFRs, it is vital that specific oligonucleotide probes be used in order to distinguish between the different DHFRs (1). The identification of the plasmid-encoded type VII DHFR in S. typhi confirms the ubiquitous distribution of this particular DHFR. This enzyme has already been isolated in Sweden, Finland, Nigeria, Sri Lanka, the United Kingdom, and more recently, South Africa (33).

As far as we are aware, no oligonucleotide probes have been used in the screening of plasmid-mediated chloramphenicol resistance among members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. It is difficult, therefore, to establish the incidence of this particular group of enzymes. Among the isolates screened, only the cat1 gene was identified.

We may conclude that in Vellore a specific strain of S. typhi has been established and has persisted in the bacterial population. Furthermore, through the acquisition of a plasmid conferring MDR, this individual strain has undergone the necessary and appropriate adaptation for survival in the changing antibiotic environment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank The Scottish Hospital Endowment Research Trust for providing a research fellowship (fellowship 1276) to P. M. A. Shanahan and The Indian National Science Academy for the fellowship for M. V. Jesudason.

We are grateful to the Sir Samuel Scott of Yews Research Trust for the grant which supported this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adrian P V, Klugman K P, Amyes S G B. Prevalence of trimethoprim resistant dihydrofolate reductase genes identified with oligonucleotide probes in plasmids from isolates of commensal faecal flora. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:497–508. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amyes S G B, Gould I M. Trimethoprim resistance plasmids in faecal bacteria. Ann Microbiol Inst Pasteur. 1984;135B:177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arora R K, Gupta A, Joshi N M, Kataria V K, Lall P, Anand A C. Multidrug resistant typhoid fever: study of an outbreak in Calcutta. Indian Pediatr. 1992;29:61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown J C, Shanahan P M A, Jesudason M V, Thomson C J, Amyes S G B. Mutations responsible for reduced susceptibility to 4-quinolones in clinical isolates of multi-resistant Salmonella typhi in India. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:891–900. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.5.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler S L, Doherty C J, Hughes J E, Nelson J W, Govan J R W. Burkholderia cepacia and cystic fibrosis: do natural environments present a potential hazard? J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1001–1004. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.1001-1004.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chanal C, Poupart M, Sirot D, Labia R, Sirot J, Cluzel R. Nucleotide sequences of CAZ-2, CAZ-6, and CAZ-7 β-lactamase genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1817–1820. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.9.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du Bois S K, Marriott M S, Amyes S G B. TEM- and SHV-derived extended-spectrum β-lactamases: relationship between selection, structure and function. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:7–22. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DuPont H L. Quinolones in Salmonella typhi infection. Drugs. 1993;45:119–124. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199300453-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Adhami W, Roberts L, Vickery A, Inglis B, Gibbs A, Stewart P. Epidemiological analysis of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus outbreak using restriction fragment length polymorphisms of genomic DNA. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:2713–2720. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-12-2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finch M J, Franco A, Gotuzzo E, Carrillo C, Benavente L, Wasserman S S, Levine M M, Morris J G., Jr Plasmids in Salmonella typhi in Lima, Peru, 1987–1988: epidemiology and lack of association with severity of illness or clinical complications. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:390–396. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabant P, Newnham P, Taylor D, Couturier M. Isolation and location on the R27 map of two replicons and an incompatibility determinant specific for IncHI1 plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7697–7701. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.23.7697-7701.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein F W, Chumpitaz J C, Guevara J M. Plasmid mediated resistance to multiple antibiotics in S. typhi. J Infect. 1986;153:261–266. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gulati S, Marwaha R K, Singhi S, Ayyagari A, Kumar L. Third generation cephalosporins in multi-drug resistant typhoid fever. Indian Pediatr. 1992;29:513–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedges R W, Datta N, Kontomichalou P, Smith J T. Molecular specificities of R factor-determined beta-lactamases: correlation with plasmid compatibility. J Bacteriol. 1974;117:56–62. doi: 10.1128/jb.117.1.56-62.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heikkila E, Sundstrom L, Skurnik M, Huovinen P. Analysis of genetic localization of the type I trimethoprim resistance gene from Escherichia coli isolated in Finland. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1562–1569. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.8.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hermans P W M, Saha S K, van Leeuwen W J, Verbrugh H A, van Belkum A, Goessens W H F. Molecular typing of Salmonella typhi strains from Dhaka (Bangladesh) and development of DNA probes identifying plasmid-encoded multidrug-resistant isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1373–1379. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1373-1379.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Islam A, Butler T, Kabir I, Alam N H. Treatment of typhoid fever with ceftriaxone for 5 days or chloramphenicol for 14 days: a randomized clinical trial. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1572–1575. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.8.1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jesudason M V, Jacob John T. Multiresistant Salmonella typhi in India. Lancet. 1990;336:252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jesudason M V, John R, Jacob John T. The concurrent prevalence of chloramphenicol-sensitive and multidrug-resistant Salmonella typhi in Vellore, S. India Epidemiol Infect. 1996;116:225–227. doi: 10.1017/s095026880005247x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karmaker S, Biswas D, Shaikh N M, Chatterjee S K, Kataria V K, Kumar R. Role of a large plasmid of Salmonella typhi encoding multiple drug resistance. J Med Microbiol. 1991;34:149–151. doi: 10.1099/00222615-34-3-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathai D, Kudwa G C, Keystone J S, Kozarsky P E, Jesudason M V, Lalitha M K, Kaur A, Thomas M, John J, Pulimood B M. Short course of ciprofloxacin in enteric fever. J Assoc Physicians India. 1993;41:7428–7430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirza S H, Hart C A. Plasmid encoded multi-drug resistance in Salmonella typhi from Pakistan. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1993;87:373–377. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1993.11812781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mourad A S, Metwally M, Nour El Deen A, Threlfall E J, Rowe B, Mapes T, Hedstrom R, Bourgeois A L, Murphy J R. Multiple-drug-resistant Salmonella typhi. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:135–136. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nair S, Poh C L, Lim Y S, Tay L, Goh K T. Genome fingerprinting of Salmonella typhi by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for subtyping common phage types. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;113:391–402. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800068400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nandivada L S, Amyes S G B. Plasmid-mediated beta-lactam resistance in pathogenic gram-negative bacteria isolated in South India. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;26:279–290. doi: 10.1093/jac/26.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naqvi S H, Bhutta Z A, Farooqui B J. Therapy of multidrug resistant typhoid in 58 children. Scand J Infect Dis. 1992;24:175–179. doi: 10.3109/00365549209052609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pang T, Bhutta Z A, Finlay B B, Altwegg M. Typhoid fever and other salmonellosis: a continuing challenge. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:253–255. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88937-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petrocheilou V, Sykes R B, Richmond M H. Novel R-plasmid-mediated beta-lactamases from Klebsiella aerogenes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977;12:126–128. doi: 10.1128/aac.12.1.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reeves M W, Evins G M, Heiba A A, Plikaytis B D, Farmer J J., III Clonal nature of Salmonella typhi and its genetic relatedness to other salmonellae as shown by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, and proposal of Salmonella bongori comb. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:313–320. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.2.313-320.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romling U, Grothues D, Heuer T, Tummler B. Physical genome analysis of bacteria. Electrophoresis. 1992;13:626–631. doi: 10.1002/elps.11501301128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rowe B, Ward L R, Threlfall E J. Spread of multiresistant Salmonella typhi. Lancet. 1990;337:1065. . (Letter.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh H, Raizada N. Chloramphenicol resistant typhoid fever. Indian Pediatr. 1991;28:433. . (Letter.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sundström L, Swedberg G, Sköld O. Characterization of transposon Tn5086, carrying the site-specifically inserted gene dhfrVII mediating trimethoprim resistance. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1796–1805. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1796-1805.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takahashi S, Nagano Y. Rapid procedure for isolation of plasmid DNA and application to epidemiological analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;20:608–613. doi: 10.1128/jcm.20.4.608-613.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thong K, Cordano A, Yassin R M, Pang T. Molecular analysis of environmental and human isolates of Salmonella typhi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:271–274. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.271-274.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thong K L, Cheong Y M, Puthucheary S, Koh C L, Pang T. Epidemiologic analysis of sporadic Salmonella typhi isolates and those from outbreaks by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1135–1141. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1135-1141.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Threlfall E J, Ward L R, Rowe B, Raghupathi S, Chandrasekaran V, Vandepitte J, Lemmens P. Widespread occurrence of multiple drug-resistant Salmonella typhi in India. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11:990–993. doi: 10.1007/BF01967788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallace M, Yousif A A. Spread of multiresistant Salmonella typhi. Lancet. 1993;336:1065–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zavala Trujillo I, Quiroz C, Gutierrez M A, Arias J, Renteria M. Fluoroquinolones in the treatment of typhoid fever and the carrier state. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;10:334–341. doi: 10.1007/BF01967008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]