Abstract

Objective:

Perception of physical attractiveness (PPA) is a fundamental aspect of human relationships and may help explain alcohol's rewarding and harmful effects. Yet PPA is rarely studied in relation to alcohol, and existing approaches often rely on simple attractiveness ratings. The present study added an element of realism to the attractiveness assessment by asking participants to select four images of people they were led to believe might be paired with them in a subsequent study.

Method:

Dyads of platonic, same-sex male friends (n = 36; ages 21–27; predominantly White, n = 20) attended two laboratory sessions wherein they consumed alcohol and a no-alcohol control beverage (counterbalanced). Following beverage onset, participants rated PPA of targets using a Likert scale. They also selected four individuals from the PPA rating set to potentially interact with in a future study.

Results:

Alcohol did not affect traditional PPA ratings but did significantly enhance the likelihood that participants would choose to interact with the most attractive targets, χ2(1, N = 36) = 10.70, p < .01.

Conclusions:

Although alcohol did not affect traditional PPA ratings, alcohol did increase the likelihood of choosing to interact with more attractive others. Future alcohol–PPA studies should include more realistic contexts and provide assessment of actual approach behaviors toward attractive targets, to further clarify the role of PPA in alcohol's hazardous and socially rewarding effects.

Although Alcohol is regularly consumed in social contexts, little research has examined its effects in social settings (Fairbairn & Sayette, 2014), highlighting significant limitations in understanding social processes contributing to drinking behavior. We sought to address this gap by investigating relations between alcohol consumption and perceptions of physical attractiveness (PPA). Physical attractiveness is a powerful psychological feature (Berscheid, 1980). The “attractiveness halo effect” refers to tendencies to judge attractive faces more positively, wherein attractive people are associated with superiority in nonphysical qualities (e.g., intelligence, sociability) and receive preferential treatment (Dion, 2002).

Attractiveness also promotes risky behavior, as individuals emphasize PPA above relevant risk cues when determining sexual behavior intentions (Agocha & Cooper, 1999). Indeed, attractiveness stimulates multiple positive and negative social experiences. Inasmuch as alcohol is regularly consumed in social contexts and PPA influences social lives, alcohol's effect on PPA likely influences typical drinking experiences. Investigation of alcohol–PPA relations may clarify alcohol's rewarding and harmful effects.

A meta-analysis revealed a significant, although surprisingly small, alcohol–PPA association, with many individual studies reporting null effects (Bowdring & Sayette, 2018). Individuals consuming alcohol tended to report higher PPA than did individuals not consuming alcohol (an effect colloquially referred to as “beer goggles”). The small magnitude of the association may have been dampened by suboptimally designed studies (e.g., static stimuli displaying neutral facial expressions; Bowdring et al., 2021). We examined alcohol's PPA effects across four visual displays: static-neutral, static-smiling, dynamic-neutral, and dynamic-smiling images. We also presented targets who had, and had not, consumed alcohol, permitting assessment of the effect of target drink-condition on PPA (Van Den Abbeele et al., 2015).

Perhaps more important than image type is stimuli realism. Typical approaches to studying alcohol and PPA require participants to rate PPA of individuals with whom they have no prospect of interacting (Bowdring & Sayette, 2018). This diverges from typical intoxicated PPA experiences (e.g., in a bar), where individuals perceive attractiveness of individuals with whom they have potential to interact. Zebrowitz (2011) argues from an ecological perspective that perception is a functional process facilitating attainment of affordances (target qualities that benefit the perceiver). Many believe drinking enhances sexual desire and sexual experiences (Brown et al., 1987)—when these expectancies are activated by alcohol consumption or cues, individuals should be more attuned to social affordances (e.g., potential sexual relations) offered by targets and perceive targets as more attractive (Friedman et al., 2005). Notably, perception processes likely differ according to whether targets are the gender that the perceiver desires, because of differences in affordances encompassed by these distinct PPA experiences (Zebrowitz & Montepare, 2006).

Although it is challenging to conduct controlled experiments enabling participants to rate PPA of individuals with whom they may interact, alcohol arguably reveals its most pronounced impact on PPA under these circumstances (Bowdring & Sayette, 2018). Alcohol reduces fear of social rejection and enhances desire to bond (Fairbairn & Sayette, 2014). Excluding real-world contingencies from PPA research likely limits ability to sensitively assess the alcohol–PPA association. We aimed to approach this naturalistic context by telling participants they might have the opportunity to engage in a subsequent experiment with individuals whose attractiveness they were rating. After PPA ratings, participants selected which targets they would be most interested in interacting with if they were invited to participate in this future study. This design permitted us to test alcohol's effect on PPA and potential moderators (target facial expression, target motion, target drink condition, sexual orientation match, sexual desire expectancies), and offered an initial test of the association between perceiver drink condition and attractiveness of targets with whom they would like to interact, which enabled testing of a liquid courage perspective. We were also interested in examining mood as a potential pathway through which alcohol alters PPA, as alcohol affects mood (Bowdring & Sayette, 2021) and mood influences perceptions (Schwarz, 2012). Thus, we tested whether post-drink mood affected PPA. We pre-registered the traditional PPA but not the selection task. We hypothesized a positive association between alcohol and PPA (for both perceiver- and target-drink) and that the association would be strongest (a) among raters with stronger sexual-desire alcohol expectancies; (b) when targets were a gender to which perceivers were sexually attracted; (c) for smiling versus neutral expressive images; and (d) for dynamic versus static images. We anticipated that individuals who reported more positive post-drink mood would provide higher PPA ratings. We also hypothesized that alcohol would enhance the likelihood of selecting to interact with more attractive targets.

Method

Participants

A total of 36 men participated in a two-session experiment.1 As described in a prior report from this project (Bowdring & Sayette, 2021), participants were recruited via newspaper ads, paper flyering, and online sites. Ads asked individuals to call the Alcohol and Smoking Research Laboratory (ASRL) if they and a friend were social drinkers who were interested in earning money for research participation. Individuals who responded underwent eligibility screening.

Eligible participants were male social drinkers ages 21–28 (the same ages as those represented in the target stimuli). Participants had to drink at least 1 day per week and affirm that they could comfortably drink at least three drinks in 30 minutes (Sayette et al., 2012). They had to consume five or more drinks on one occasion in the past 6 months. To mitigate variability in alcohol absorption, participants had to be within 20% of the normed weight for their height and weigh less than 200 lb (Harrison, 1985). Participants had to have a nonromantic same-sex friend with whom they regularly drank who also would pursue participation.

Per past research (e.g., McCarthy et al., 2012), participants were excluded if they had any medical or psychiatric conditions that contraindicated alcohol consumption (e.g., diabetes, bipolar disorder), were currently taking medication contraindicated by alcohol, or had ever intentionally abstained from alcohol because of either formal diagnosis or concern about having a substance use disorder. Participants were excluded if they denied English fluency, as it could reduce understanding of task instructions, or if they had uncorrected visual impairment, which could diminish perception of stimulus facial features.

Eligible individuals invited a nonromantic same-sex friend with whom they regularly drank to contact the ASRL to undergo screening. Recruiting dyads facilitated a social context for the drinking period that more closely matched participants’ (who self-identified as social drinkers) drinking experiences outside the lab, as social context alters drinking experiences (Pliner & Cappell, 1974).

Procedure

Eligible dyads were required to (a) abstain from alcohol for 24 hours—and food and caffeine for 4 hours—before each session; (b) provide a breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) sample each session (breath reading of < .003%); and (c) consume alcohol during one session. Dyads who agreed to these terms were scheduled for two sessions.

Session one

As described elsewhere (Bowdring & Sayette, 2021), at session one participants underwent informed consent and initial study procedures separately. Participants were weighed, provided a BrAC sample, and completed questionnaires (see the Materials section) while consuming a bagel (amount determined by weight) (Sayette et al., 2001). Next, the experimenter mixed the drinks in front of the participants. Drink condition (alcohol vs. no-alcohol control) was randomized by dyad and counter-balanced across sessions. For the alcohol condition, a 0.82 g/kg dose of alcohol was provided using 100-proof vodka and 3.5 parts cranberry juice cocktail. Participants were told that their drinks contained alcohol. For the control condition, participants received cranberry juice cocktail and were told that their drinks did not contain alcohol. Total beverage was isovolumetric across conditions. After drinks were mixed, the dyad was seated together.

Before drinking, participants were informed that they could talk during the drinking period but were asked to refrain from discussing their perceived intoxication; they also learned that at the midpoint of the drinking period they would view a series of images on a computer and be prompted to rate the attractiveness of each image (PPA task). Participants were told that the images were of participants from a recent study who may participate in a future ASRL study and that they (the present-study participants) also might be invited to participate in the future study. In addition, participants learned that, following the PPA task, they would select four individuals they rated whom they would be interested in potentially interacting with during the future study (although no such study occurred). We informed participants of this posttask prompt before drinking to ensure that all participants were sober at the time they received this key information. This use of deception, which was disclosed to participants following session two, aimed to enhance beliefs that they had potential to interact with the individuals whom they were rating, as PPA may differ when individuals have potential to interact with the targets (Zebrowitz & Montepare, 2006).

Participants received half of their beverage at Minute 0 and the other at Minute 18, such that they consumed the entire beverage across 36 minutes. They were asked to drink each half evenly over the 18 minutes.

Computer-based tasks. At Minute 18, participants received the second drink portion and began the PPA task. They consumed the second half of their drink during the task to permit assessment of alcohol's effect on PPA while BrACs continued to rise steeply (Sayette, 2017). Attractiveness stimuli were derived from video images of participants who participated in a previous ASRL study (see Materials section regarding stimuli development). Each participant recorded their responses using a keyboard. Responses were obfuscated on screen and a barrier between the two keyboards prevented participants from viewing each other's responses.

Participants were asked to refrain from discussing their reactions to images but were otherwise permitted to talk. After completing all ratings, a screen with an image of each target was displayed and participants were prompted to select four individuals with whom they would be interested in interacting in a future study.

Posttask. After drinking, participants provided BrACs, completed questionnaires, were asked to refrain from discussing their ratings, and were compensated ($25 of $90). Participants in the alcohol condition could depart once BrACs dropped below .04% and they confirmed that they would not be driving themselves (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, n.d.).

Session two

Session two mirrored session one, except for the following: Participants received the beverage type they did not receive in session one; they viewed a different set of PPA images than they did during session one (Peskin & Newell, 2004);2 and after providing the post-drink BrAC sample and completing post-drink measures, subjects completed additional tasks unrelated to the present report. Finally, participants were debriefed and were paid the remaining $65.

Materials

Before the drinking period at session one, participants reported their demographic information, including sexual orientation. For participants self-identified as heterosexual, female targets were coded as orientation-matched and male targets were considered orientation-mismatched. The opposite was true for gay participants, and for bisexual participants both male and female targets were coded as orientation-matched. Pre-drink mood was assessed each session using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988). Before and after the drinking period, participants reported subjective intoxication using a Likert scale, ranging from 0 (not at all intoxicated) to 100 (the most intoxicated I have ever been). After the drinking period, participants completed an eight-item mood measure that is sensitive to alcohol's effects (Fairbairn et al., 2015). Participants also estimated how many ounces of vodka they had consumed during the session (Sayette et al., 2012). Following session two tasks, participants responded to a series of questions on their relationship with their friend (adapted from Dimoff et al., 2019) and reported their alcohol expectancies, using the “desire” factor of the Sexual Effects of Drinking Questionnaire (SEDQ; Skinner, 1992).3 Participants’ BrACs were assessed on both sessions using DataMaster Breath Alcohol tester (National Patent Analytical Systems, Mansfield, OH).

PPA task

Attractiveness stimuli were derived from video footage of individuals who participated in a previous ASRL study (see Sayette et al., 2012) and consented to having their videos used in future research. Videos were obtained during a triadic group-formation drinking period, wherein 240 three-person groups of strangers consumed alcoholic, placebo, or control beverages in the laboratory. Three cameras captured participants’ faces. The present study only derived images from the alcohol and control groups to mirror the perceiver drink conditions.

Stimuli (static-neutral, static-smiling, dynamic-neutral, and dynamic-smiling images) were extracted from video footage of the last 12 minutes of the drinking period in the previous study to ensure that alcohol-consuming participants were captured nearest peak intoxication.4 See the supplemental materials regarding PPA task development. (Supplemental material appears as an online-only addendum to this article on the journal's website.)

Consistent with prior recommendations, every participant viewed each target (16 targets per session; 32 targets total) presented in all four stimulus formats (Bowdring et al., 2021). Presentation duration of static and dynamic images was held constant at 5 seconds and participants were given just one opportunity to view each image. After each image presentation, a screen prompting participants to rate PPA was presented until participants clicked to progress to the next image. PPA ratings were reported using a Likert scale of 1 (very unattractive) to 10 (very attractive). This task was hosted on Qualtrics (Provo, UT).

Selection to interact task

Participants were presented with a screen with static-smiling images of all 16 targets from that session. They were asked to indicate four targets whom they would most want to interact with during a future study.

To determine the most attractive targets within each set, we averaged each target's PPA rating (from the original task) across participants and ordered them from highest (1) to lowest (16). We then calculated a count for each participant of how many of the top-four most attractive targets they selected. The count outcome ranged from 0 (none of the top-four attractive targets were selected) to 4 (each of the top-four attractive targets were selected).

Analytic plan

All analyses were conducted using R statistical software (R Foundation; Vienna, Austria). Analyses and hypotheses for examinations related to alcohol's effects on PPA were pre-registered, although with a larger intended (pre-COVID-19) sample size (available at https://osf.io/bhr9f and https://osf.io/bdn48). Significance cutoffs were set at p < .05 for all tests.

For all analyses, order of drink condition and pre-drink mood were entered as covariates but removed if they did not significantly increase model fit. Data were analyzed using a series of mixed-effects models using lme4, lrtest, and ordinal extensions (Bates et al., 2014; Christensen, 2019; Zeileis & Hothorn, 2002). For each study design effectiveness significance test and main analysis, intercepts for perceivers (nested within dyads) and targets were entered as random effects to account for non-independence of responses within each grouping. Variables of interest were entered as fixed effects. Likelihood ratio tests were used to compare the full models with the effect(s) of interest against a model with the effect(s) of interest removed. The p value yielded by model comparison was assessed to determine if the effects of interest significantly enhanced the variance explained in the outcome. Assessment of the effect of sexual-desire expectancies was limited to orientation-matched ratings, as we would not predict these expectancies to alter PPA for orientation-mismatched ratings. We used linear mixed-effects models for analyses related to the PPA task. For our selection to interact analysis, because of the ordinal nature of the outcome, we ran a cumulative link mixed-effects model.

Results

Participants

Participants’ ages ranged from 21 to 27 years (M = 22.69, SD = 1.67). Most participants were White (n = 20 White, 14 Asian, 2 Black), heterosexual (34 heterosexual, 1 gay, 1 bisexual), and not in a romantic relationship (n = 20 not in a romantic relationship, 16 in a romantic relationship). Participants reported drinking 2.28 days per week (SD = 0.88) and consuming 4.14 drinks per occasion (SD = 1.94). Participants reported knowing the friend with whom they participated for 3.51 years (SD = 2.36). They reported drinking with their friend 3.88 times per month (SD = 2.08) and, on a scale of 0 (not at all close) to 10 (very close), they reported their feelings of closeness with their friend as 8.09 (SD = 1.27).

One dyad was excluded after consenting to participate, as one participant's weight fell outside the required range. Data from two dyads are not included in analyses because they only completed one session before the suspension of data collection due to COVID-19. Analyses are based on 36 participants clustered in 18 dyads that completed both sessions.

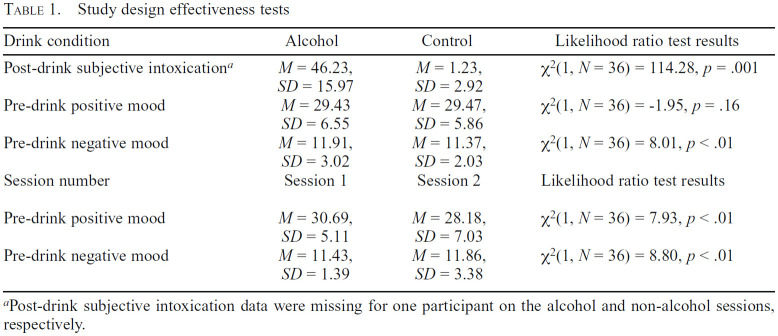

Study design effectiveness

As previously reported (Bowdring & Sayette, 2021), BrACs approximately 5 minutes after the drinking period during the alcohol session were .065% (SD = .01), 50 minutes after the drinking period were .070% (SD = .01), and 95 minutes after the drinking period were .063% (SD =.01). All participants who estimated ounces of alcohol consumed following the alcohol session reported nonzero estimates (M = 5.29, SD = 1.36). On the non-alcohol session, all but one participant (who estimated two ounces) reported believing they had consumed zero ounces of alcohol. See Table 1 for details on post-drink subjective intoxication, and pre-drink positive and negative mood split by drink condition and session.5

Table 1.

Study design effectiveness tests

| Drink condition | Alcohol | Control | Likelihood ratio test results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-drink subjective intoxicationa | M =46.23, SD = 15.97 | M = 1.23, SD = 2.92 | χ2(1, N = 36)= 114.28, p = .001 |

| Pre-drink positive mood | M = 29.43 SD = 6.55 | M = 29.47, SD = 5.86 | χ2(1, N = 36) = -1.95, p =.16 |

| Pre-drink negative mood | M = 11.91, SD = 3.02 | M = 11.37, SD = 2.03 | χ2(1, N =36) = 8.01, p <.01 |

| Session number | Session 1 | Session 2 | Likelihood ratio test results |

| Pre-drink positive mood | M = 30.69, SD = 5.11 | M =28.18, SD = 7.03 | χ2(1, N = 36) = 7.93, p < .01 |

| Pre-drink negative mood | M = 11.43, SD = 1.39 | M = 11.86, SD = 3.38 | χ2(1, N = 36) = 8.80, p < .01 |

Post-drink subjective intoxication data were missing for one participant on the alcohol and non-alcohol sessions, respectively.

Alcohol's effect on PPA using a traditional assessment

Supplementary tables provide full model results. In contrast to hypotheses, perceivers’ PPA ratings were similar between alcohol and control sessions, χ2(1, N = 36) = 0.02, p = .90, and were unaffected by target drink, χ2(1, N = 36) = 0.10, p = .76. As hypothesized, there was not a significant interaction between perceiver and target drink condition on PPA, χ2(1, N = 36) = 3.53, p = .06. We also did not find significant interactions between perceiver-drink and orientation-match on PPA, χ2(1, N = 36) = 1.14, p = .29, or target-drink and orientation-match on PPA, χ2(1, N = 36) = 1.60, p = .21. Nor were there significant interactions between perceiver-drink and perceiver sexual-desire alcohol expectancies on PPA, χ2(1, N = 36) = 3.77, p = .05, perceiver-drink and target facial expression on PPA, χ2(1, N = 36) = 2.53, p = .11, or perceiver-drink and target motion on PPA, χ2(1, N = 36) = 3.30, p = .07.

We also examined the effect of post-drink mood on PPA. Post-drink positive mood significantly enhanced model fit, χ2(1, N = 36) = 7.27, p < .01, but, contrary to hypotheses, was not a significant individual predictor (p = .80). Also contrary to the hypotheses, post-drink negative mood did not significantly enhance model fit, χ2(1, N = 36) = 1.24, p = .27.

Alcohol's effect on selection to interact with attractive others

In contrast to the absence of effects of alcohol using traditional PPA assessment, when participants selected targets to potentially interact with in a future study, alcohol's effects emerged. Specifically, we assessed the effect of beverage condition on participants’ choices to interact with most attractive targets. As hypothesized, alcohol enhanced the likelihood of selecting to interact with the top-four most attractive targets, χ2(1, N = 36) = 10.70, p < .01. Odds of selecting the top-four attractive targets after consuming alcohol were 1.71 (95% CI [0.61, 2.81]) times that after consuming no-alcohol control beverages. The average number of top-four attractive targets selected by participants drinking alcohol was 2.69 (SD = 0.82) and control beverages was 2.17 (SD = 1.03).

Discussion

Despite conventional wisdom that alcohol increases PPA and that these enhanced attractiveness perceptions may underlie both drinking motivation and hazardous drinking consequences, this topic has received limited empirical scrutiny. Prior findings on alcohol and PPA are mixed (Bowdring & Sayette, 2018). We aimed to use a host of new methods to test this association. We (a) tested participants while interacting with a friend, (b) systematically manipulated the drinking status of perceivers and targets, (c) controlled for perceiver intoxication and position on the BrAC curve, and (d) varied target expressiveness and motion. These factors were tested using a self-reported PPA rating traditionally used in PPA research (Bowdring & Sayette, 2018; Monk et al., 2020). As with many prior studies (Bowdring & Sayette, 2018), our findings with PPA ratings did not detect effects of alcohol. Neither perceiver nor target drink condition influenced PPA ratings. Nor did sexual-orientation match, target expressiveness, target motion, and perceiver alcohol expectancies moderate the alcohol–PPA relation. Although our a priori power analysis indicated that 36 participants in a within-subjects design provided adequate power to detect an effect of alcohol on PPA of the aggregate magnitude observed in prior work, the premature termination of the study because of COVID is a limitation—a larger sample may be needed to observe effects in a single experiment. In addition, although our supplemental study (see the online-only supplemental material) confirmed that image set did not significantly affect PPA, lack of counterbalancing image sets across conditions is another factor to consider when interpreting the null findings. Beyond these explanations, we suspect the null findings may relate to lack of salience of potential to interact with targets during the traditional PPA task, such that alcohol's effect on person perception only arose when participants were reminded of interaction potential during the selection to interact task.

In contrast to our findings with traditional attractiveness ratings, we observed a significant effect of alcohol on selection to interact with more attractive targets. After consuming alcohol, participants were more likely to prefer to interact with the most attractive targets than they were after having consumed control beverages. Considerable research has demonstrated that people prefer to interact with more attractive others (Lerner et al., 1991; Smolak, 2012). Exposure to attractive others, however, can increase self-awareness and heighten anxiety (Thornton & Moore, 1993), and ultimately lead to social disengagement (McClure & Lydon, 2014). Desire to form connections conflicts with fear of encountering rejection (Murray et al., 2006), and doubting a target's receptivity to social interaction reduces desire for that target (Greitemeyer, 2010). This study suggests that one aspect of beer goggles missing from past experiments is the prospect that one might actually be able to meet, flirt, or perhaps engage intimately with a target. Our measure of partner selection approaches this possibility, and this measure is where alcohol exerted its impact. In this sense, the notion of beer goggles begins to bleed into its neighboring term “liquid courage.” Alcohol increases flirting, sexual imagination, and sexual behavior (Pedersen et al., 2017), and these experiences are linked to PPA. Our finding that alcohol increased the likelihood of selecting the most attractive targets for future interaction accords with the social attribution model of alcohol, which posits that “alcohol enhances social experiences by disabling cognitive processes engaged in the anticipation and elaboration of social threat—freeing us from our preoccupation with rejection and enabling us to access social rewards” (Fairbairn & Sayette, 2014).

If replicated, this finding has implications for clinicians and researchers, as it reveals one process (PPA) that may underlie the rewarding, yet potentially hazardous nature of alcohol. For example, greater reward may be derived from social interactions while intoxicated if alcohol enhances likelihood of interacting with more attractive others (Snyder et al., 1977). Moreover, such an effect may shed light on processes underlying risky sexual behavior (Corbin & Fromme, 2002), as risky sexual practices are more likely when potential partners are perceived as attractive (Agocha & Cooper, 1999). Psychoeducation on the influence of alcohol on social perception (and likely, in turn, behaviors) may open the door for clients to share experiences with alcohol-altered social perception and proactively discuss how they wish to navigate future social situations involving alcohol. We hope the present finding that alcohol led to selecting more attractive targets stimulates methods in alcohol–PPA studies involving more diverse samples of perceivers and targets (e.g., in terms of gender, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, drinking history) that permit actual approach behaviors toward attractive targets (e.g., initiating conversation). Future research would also benefit from parsing pharmacological from expectancy effects by incorporating a placebo condition and manipulating position on the BrAC curve when assessing the alcohol–PPA relation.

Conflict-of-Interest Statement

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the Research Society on Alcoholism Graduate Student Small Grants Award to Molly A. Bowdring, internal funds provided by the Department of Psychology at the University of Pittsburgh to Molly Bowdring, and the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Grant R01 AA015773) to Michael Sayette. This study was pre-registered at https://osf.io/bhr9f.

Although we are disinclined to preference male recruitment, alcohol-related social rewards are particularly strong for male drinkers (Sayette, 2017). As with our prior social bonding research (Kirchner et al., 2006; Sayette et al., 2012), we aim to use the present data to justify a larger follow-up including participants of diverse genders.

Image set was counterbalanced across the first and second sessions. Unfortunately, randomization of image set and drink condition was the same, such that image set 1 was always viewed during alcohol sessions and image set 2 was always viewed during control sessions. This motivated a supplemental online study, which confirmed that image set did not significantly affect PPA (supplemental materials: https://osf.io/mcy6r).

Participants completed the SEDQ at the end of session two because even alcohol-related words can alter PPA (Friedman et al., 2005) and we did not want the measure to prime participants before the PPA task.

Consistent with prior work, perceivers in the present study were not informed of target drink condition (Van Den Abbeele et al., 2015).

All but four participants reported zero for pre-drink subjective intoxication. On the non-alcohol session, two participants reported 1 and 2, respectively, and on the alcohol session, two participants reported 5 and 100, respectively. We suspect that the participant who reported 100 misunderstood the question.

References

- Agocha V. B., Cooper M. L. Risk perceptions and safer-sex intentions: Does a partner's physical attractiveness undermine the use of risk-relevant information? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999;25:751–765. doi:10.1177/0146167299025006009. [Google Scholar]

- Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. 2014 Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/1406.5823. [Google Scholar]

- Berscheid E.1980An overview of the psychological effects of physical attractivenessIn Lucker G. W., Ribbens K. A., McNamara J. A., Jr. (Eds.), Psychological aspects of facial form (Monograph No. 11: Craniofacial growth series Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan [Google Scholar]

- Bowdring M. A., Sayette M. A. Perception of physical attractiveness when consuming and not consuming alcohol: A meta-analysis. Addiction. 2018;113:1585–1597. doi: 10.1111/add.14227. doi:10.1111/add.14227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowdring M. A., Sayette M. A. The effect of alcohol on mood among males drinking with a platonic friend. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2021;45:2160–2166. doi: 10.1111/acer.14682. doi:10.1111/acer.14682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowdring M. A., Sayette M. A., Girard J. M., Woods W. C. In the eye of the beholder: A comprehensive analysis of stimulus type, perceiver, and target in physical attractiveness perceptions. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 2021;45:241–259. doi:10.1007/s10919-020-00350-2. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. A., Christiansen B. A., Goldman M. S. The Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire: An instrument for the assessment of adolescent and adult alcohol expectancies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1987;48:483–491. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1987.48.483. doi:10.15288/jsa.1987.48.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen R. H. B.Regression models for ordinal data [R package ordinal version 2019.12-10] 2019. Retrieved from https://r.search.yahoo.com/_ylt=AwrEs9H6CTdk8PIORglXNyoA;_ylu=Y29sbwNiZjEEcG9zAzEEdnRpZAMyNTQzNFNDXzEEc2VjA3Ny/RV=2/RE=1681357435/RO=10/RU=https%3a%2f%2fwww.semanticscholar.org%2fpaper%2fRegression-Models-for-Ordinal-Data-Introducing-Christensen%2fa4ddf910eddf0f2abc742a91ac18308cf82ef04e/RK=2/RS=XRufvlYo3xoBYgrrpmtgsHbLzx8-

- Corbin W. R., Fromme K. Alcohol use and serial monogamy as risks for sexually transmitted diseases in young adults. Health Psychology. 2002;21:229–236. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.3.229. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.21.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimoff J. D., Sayette M. A., Levine J. M. Experiencing cigarette craving with a friend: A shared reality analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2019;33:721–729. doi: 10.1037/adb0000519. doi:10.1037/adb0000519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dion K. K.2002Cultural perspectives on facial attractivenessIn Rhodes G., Zebrowitz L. A. (Eds.), Advances in visual cognitionVol. 1pp. 239–259.New York, NY: Ablex Publishing [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn C. E., Sayette M. A. A social-attributional analysis of alcohol response. Psychological Bulletin. 2014;140:1361–1382. doi: 10.1037/a0037563. doi:10.1037/a0037563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn C. E., Sayette M. A., Wright A. G. C., Levine J. M., Cohn J. F., Creswell K. G. Extraversion and the rewarding effects of alcohol in a social context. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2015;124:660–673. doi: 10.1037/abn0000024. doi:10.1037/abn0000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman R. S., McCarthy D. M., Förster J., Denzler M. Automatic effects of alcohol cues on sexual attraction. Addiction. 2005;100:672–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01056.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greitemeyer T. Effects of reciprocity on attraction: The role of a partner's physical attractiveness. Personal Relationships. 2010;17:317–330. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01278.x. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison G. G. Height-weight tables. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1985;103:989–994. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-6-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner T. R., Sayette M. A., Cohn J. F., Moreland R. L., Levine J. M. Effects of alcohol on group formation among male social drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:785–793. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.785. doi:10.15288/jsa.2006.67.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner R. M., Lerner J. V., Hess L. E., Schwab J., Jovanovic J., Talwar R., Kucher J. S. Physical attractiveness and psychosocial functioning among early adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1991;11:300–320. doi:10.1177/0272431691113001. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy D. M., Niculete M. E., Treloar H. R., Morris D. H., Bartholow B. D. Acute alcohol effects on impulsivity: Associations with drinking and driving behavior. Addiction. 2012;107:2109–2114. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03974.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03974.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure M. J., Lydon J. E. Anxiety doesn't become you: How attachment anxiety compromises relational opportunities. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2014;106:89–111. doi: 10.1037/a0034532. doi:10.1037/a0034532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk R. L., Qureshi A. W., Lee S., Darcy N., Darker G., Heim D. Can beauty be-er ignored? A preregistered implicit examination of the beer goggles effect. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2020;34:477–483. doi: 10.1037/adb0000555. doi:10.1037/adb0000555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray S. L., Holmes J. G., Collins N. L. Optimizing assurance: The risk regulation system in relationships. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:641–666. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.641. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Administering alcohol in human studies. n.d.. Retrieved from https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/Resources/ResearchResources/job22.htm.

- Pedersen W., Tutenges S., Sandberg S. The pleasures of drunken one-night stands: Assemblage theory and narrative environments. International Journal on Drug Policy. 2017;49:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.08.005. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peskin M., Newell F. N. Familiarity breeds attraction: Effects of exposure on the attractiveness of typical and distinctive faces. Perception. 2004;33:147–157. doi: 10.1068/p5028. doi:10.1068/p5028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliner P., Cappell H. Modification of affective consequences of alcohol: A comparison of social and solitary drinking. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1974;83:418–425. doi: 10.1037/h0036884. doi:10.1037/h0036884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette M. A. The effects of alcohol on emotion in social drinkers. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2017;88:76–89. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.06.005. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette M. A., Creswell K. G., Dimoff J. D., Fairbairn C. E., Cohn J. F., Heckman B. W., Moreland R. L. Alcohol and group formation: A multimodal investigation of the effects of alcohol on emotion and social bonding. Psychological Science. 2012;23:869–878. doi: 10.1177/0956797611435134. doi:10.1177/0956797611435134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette M. A., Martin C. S., Perrott M. A., Wertz J. M., Hufford M. R. A test of the appraisal-disruption model of alcohol and stress. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:247–256. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.247. doi:10.15288/jsa.2001.62.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N.2012Feelings-as-information theoryIn Van Lange P. A. M., Kruglanski A. W., Higgins E. T. (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychologypp.289–308.Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; doi:10.4135/9781446249215.n15 [Google Scholar]

- Skinner J. B. Drinking to excuse threatening sexual arousal. Dissertation Abstracts International. 1992;52(7-B):3932. [Google Scholar]

- Smolak L.2012Appearance in childhood and adolescenceIn Rumsey N., Harcourt D. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the psychology of appearancepp.123–141New York, NY: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Snyder M., Tanke E. D., Berscheid E. Social perception and interpersonal behavior: On the self-fulfilling nature of social stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1977;35:656–666. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.35.9.656. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton B., Moore S. Physical attractiveness contrast effect: Implications for self-esteem and evaluations of the social self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1993;19:474–480. doi:10.1177/0146167293194012. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Abbeele J., Penton-Voak I. S., Attwood A. S., Stephen I. D., Munafò M. R. Increased facial attractiveness following moderate, but not high, alcohol consumption. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2015;50:296–301. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agv010. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agv010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D., Clark L. A., Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowitz L. A.2011Ecological and social approaches to face perception In The Oxford handbook of face perceptionpp. 31–50.New York, NY: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Zebrowitz L. A., Montepare J. M.2006The ecological approach to person perception: Evolutionary roots and contemporary offshootsIn Schaller M., Simpson J. A., Kendrick D. T. (Eds.), Evolution and social psychologypp. 81–113.New York, NY: Psychosocial Press [Google Scholar]

- Zeileis A., Hothorn T. Diagnostic checking in regression relationships. R News. 2002;2/3:7–10. [Google Scholar]