ABSTRACT

Background and Aims:

Direct laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation cause an increase in heart rate (HR) and blood pressure, called as pressor response. This study aimed to compare nebulised forms of fentanyl, dexmedetomidine and magnesium sulphate to attenuate the haemodynamic response to laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation.

Methods:

This double-blinded, randomised study was conducted on 90 patients undergoing elective surgery requiring endotracheal intubation. Nebulisation was done with fentanyl 1 μg/kg (Group A), dexmedetomidine 1 μg/kg (Group B) and magnesium sulphate (MgSO4) (40 mg/kg) (Group C). Systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP) and HR were recorded before nebulisation (T0), post-nebulisation (T1) and at 2, 5 and 10 min after intubation (T2, T3, T4). The statistical analysis for comparing continuous variables between the groups was performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), and a P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results:

Compared to T0, an increase in HR at T2 and T3 was seen in Group A only, which reached baseline values at T4 (P values <0.0001 and 0.037, respectively). No HR value was higher than the baseline readings in groups B and C. The decreasing trend of SBP, DBP and MAP was seen in all three groups. Groups B and C had a statistically significant decrease in all the values from baseline (P values <0.0001).

Conclusion:

Nebulised form of dexmedetomidine (1 μg/kg) and magnesium (40 mg/kg) seems to be superior to fentanyl (1 μg/kg) in blunting the stress response to laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation.

Keywords: Dexmedetomidine, fentanyl, intubation, laryngoscopy, magnesium, pressor, airway

INTRODUCTION

Direct laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation increase the heart rate (HR) and blood pressure resulting from sympathetic nervous system stimulation called ‘pressor response’. It may cause serious complications such as pulmonary oedema, myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular haemorrhage.[1] Several studies have been conducted on drugs like opioids, vasodilators, beta-blockers, lignocaine and α2-agonists to attenuate the pressor response. None of the techniques is exemplary.[2,3] It was reported that dexmedetomidine[4] and magnesium sulphate (MgSO4)[5] were effective in decreasing the pressor response in a nebulised form. Fentanyl is commonly used in an intravenous (IV) form to attenuate pressor response; the nebulised form has not been used for pressor response suppression. However, it has been used in nebulised form for pain relief.[6] Hence, this study was planned to compare the nebulised form of fentanyl, dexmedetomidine and MgSO4 to attenuate haemodynamic response to laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation.

The study’s primary objective was to observe the alteration in HR from baseline pre-nebulisation (T0) to 2 min after intubation (T2) in response to laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation. Secondary objectives were to observe the alteration in HR at other time points, that is, 5 min after intubation (T3) and 10 min after intubation (T4), and to observe the systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP) at pre-nebulisation (T0), post-nebulisation (T1) and post-intubation at 2, 5 and 10 min (T2, T3 and T4).

METHODS

This double-blinded randomised study was carried out in a tertiary care centre. After ethical committee approval (vide approval number IEC/134 X/11/13/2021- IEC/31 dated 10 August 2021), the study was registered in Clinical Trials Registry – India (CTRI) (vide registration number CTRI/2021/09/036806, https://ctri.nic.in/). The confidentiality of subjects was maintained. The study was conducted from October 2021 to April 2022 in accordance with the principles of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki, 1975, revised in 2013. Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients for participating in the study and using the patient data for research and educational purposes.

Patients aged between 18 and 60 years, of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I and II and Mallampati grading I to II, undergoing elective surgery requiring endotracheal intubation, were included in the study. Patients with drug allergies, body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2, a history of cardiovascular diseases like ischaemic heart disease and uncontrolled hypertension, a history of alcohol intake, chronic analgesic or drug abuse, and pregnant patients were excluded from the study. Patients who required tracheal intubation time >20 s were excluded from the analysis.

Ninety patients were recruited for the studies and randomised into three groups using computer-generated random numbers. Allocation concealment was done using a serially labelled sealed envelope that was opened once the patient arrived in the pre-operative area. Nebulisation was done with fentanyl 1 μg/kg (Group A), dexmedetomidine 1 μg/kg (Group B) and magnesium sulphate (MgSO4) (40 mg/kg) (Group C). Basal HR, SBP, DBP and MAP were recorded in the pre-operative room 30 min before shifting the patient to the operation theatre (T0). The patient and the observer were unaware of the interventional group being allotted. The primary investigator prepared and handed over the drug to a senior resident, who was unaware of the drug made and was supposed to administer the drug and handle that particular case along with the table consultant.

Nebulisation was done in a sitting position using the Romsons Aeromist Nebuliser accessories kit (Romsons Scientific and Surgical Pvt. Ltd, Delhi, India). According to randomisation, the drug was diluted in normal saline up to 5 ml, and nebulisation was done with oxygen at a rate of 6 l/min, 15–20 min before anaesthesia induction. The independent anaesthesiologist observed that the nebuliser could create a fine mist till the entire volume was dispersed – usually within 10–15 min. Nebulisation was stopped when no further mist on tapping the volume chamber was seen. The primary investigator observed the side effects of the nebulised drugs, like bradycardia, increased sedation or decreased peripheral oxygen saturation. If any such event was witnessed, nebulisation was stopped immediately, and the patient was treated accordingly. If the nebulisation procedure was uneventful, post-nebulisation (T1) readings were recorded.

Patients were shifted to the operation theatre and ASA standard monitors were attached. All patients were pre-oxygenated and pre-medicated with IV fentanyl 2 μg/kg; after waiting for 3 min, anaesthesia was induced with IV propofol 2–3 mg/kg, and doses were titrated to the loss of verbal response. After administration of IV vecuronium bromide 0.1 mg/kg, the trachea was intubated by a senior anaesthesiologist with experience of at least five years of anaesthesia. Anaesthesia was maintained with oxygen: air (50:50) and sevoflurane to achieve a minimal alveolar concentration (MAC) of 1. The HR, SBP, DBP and MAP at 2, 5 and 10 min after intubation (T2, T3 and T4) was noted. Surgery was started 10 min after laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation. The cases were handled as per the standard general anaesthesia protocol. Trachea was extubated at the end of the surgery.

During the study period, any fall in SBP >30% from the baseline for >60 s was treated with IV mephentermine 3 mg. Any increase in SBP >30% from baseline for >60 s was to be treated with IV esmolol 0.5 mg/kg aliquots, and bradycardia (HR <45/min) was treated with IV atropine 0.6 mg.

Since three groups were taken for the study, the sample size was calculated based on the expected difference between the two groups while adjusting the alpha error for multiple comparisons (three comparisons in the case of three groups). The sample size for the study was based on Sheth et al.,[7] who reported the mean HR after tracheal intubation as 104.16 ± 5.44 beats/min, where patients were nebulised with dexmedetomidine. The sample size was calculated to detect a difference as low as five beats/minute, assuming 80% power and 95% confidence interval (CI); the minimum sample size required was 26 in each group. Allowing for 10% dropouts, the final sample size was 26/0.9 ≈ 30/group.

Statistical analysis was done using International Business Machine Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY) version 20. The statistical analysis for comparing continuous variables like age, HR, SBP, DBP and MAP were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), and a P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Bonferroni analysis was performed for variables with a significant difference between the groups. The categorical variables like gender and ASA physical status were compared using the Chi-square or Fisher exact tests when the expected cell values were <5.

RESULTS

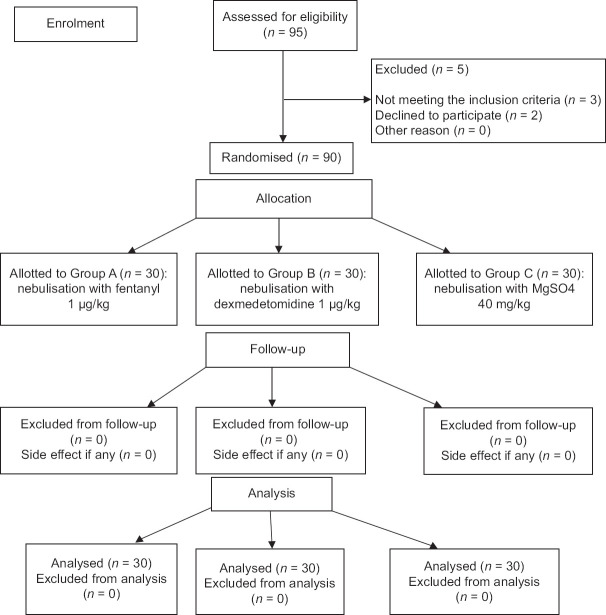

Ninety-five patients were assessed for eligibility, and 90 patients were randomised and allocated to three groups [Figure 1]. No exclusion was done post-randomisation. All three groups’ demographic parameters were comparable [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram of the participants in the study

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients in the three groups

| Characteristics | Group A (n=30) | Group B (n=30) | Group C (n=30) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40.5±14.8 | 42.3±10.5 | 39.4±12.3 |

| Gender | |||

| Male: Female | 16:14 | 16:14 | 15:15 |

| Weight (kg) | 53.6±9.8 | 56±7.3 | 57.6±10.2 |

| ASA-I: II | 16:14 | 15:15 | 14:16 |

Data presented as mean±standard deviation or numbers. ASA=American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status

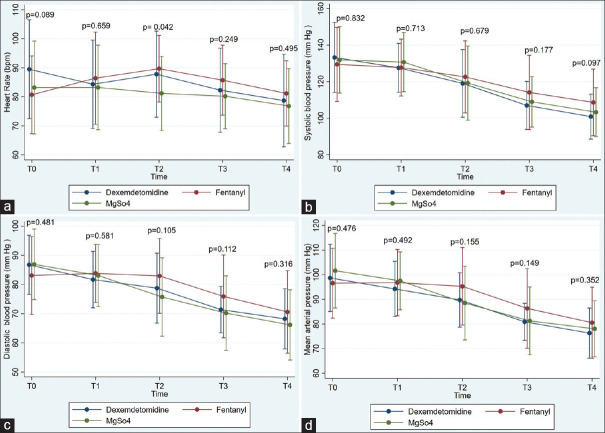

HR readings at T0 and T1 were comparable in all three groups [Figure 2]. Patients of Group C showed a significant decrease in HR at T2 compared to Group A patients (P = 0.042). However, there was no statistically significant difference between all groups at other time frames on intergroup analysis. On intragroup analysis, Group A patients showed a statistically significant increase in HR at T2 and T3 compared to T0 (P < 0.001 and 0.037, respectively); HR reached near-baseline values at T4, showing no significant difference between T0 and T4. In Group B, there was no significant change in HR at T2 compared to T0; however, a significant decrease in HR at T1 (P = 0.028), T3 (P value 0.002) and T4 (P < 0.001) compared to baseline values was seen. Patients of Group C showed a persistent decrease in HR from the baseline values; there was no significant change in HR at T2 compared to T0, and a statistically significant decrease was seen at T4 compared to T0 (P = 0.007).

Figure 2.

Variations in haemodynamics at different time intervals: (a) heart rate, (b) systolic blood pressure, (c) diastolic blood pressure, (d) mean arterial blood pressure. Values are presented as mean ± SD. T0: baseline pre-nebulisation, T1: post-nebulisation, T2: 2 min after intubation, T3: 5 min after intubation, T4: 10 min after intubation. SD = standard deviation, MgSO4 = Magnesium Sulphate

On intergroup analysis, there was no statistically significant difference in SBP, DBP and MAP [Figure 2] in all three groups at all the time points, that is, T0, T1, T2, T3 and T4. On intragroup analysis, in Group A, there was a statistically significant decrease in SBP between T0 and T2 readings (P = 0.039). There was no significant difference in DBP and MAP among T0, T1 and T2 readings. Group A showed a persistent decrease in SBP, DBP and MAP at T3 and T4 compared to T0 (P = <0.001). In Group B, there was a persistent decrease in SBP, DBP and MAP at T2, T3 and T4 compared to T0 values (P < 0.001). T0 and T1 readings of SBP and MAP were comparable. However, there was a statistically significant decrease in DBP between T0 and T1 readings (P = 0.036). In Group C, there was a persistent decrease in SBP, DBP and MAP at T2, T3 and T4 compared to T0 (P < 0.001). There was no significant difference between T0 and T1 readings. After completion of the study period and before the commencement of surgery, hypotension was observed in two Group C patients treated with IV mephentermine 6 mg.

DISCUSSION

In our study, an increase in HR post-tracheal intubation was seen in the fentanyl group only, reaching baseline values in 10 min. No value was higher than the baseline readings in the magnesium and dexmedetomidine groups. Also, the decreasing trend of SBP, DBP and MAP was seen in all three groups at 5 and 10 min post-intubation compared to baseline values. At 2 min post-intubation, magnesium and dexmedetomidine showed a statistically significant decrease in all the values from baseline (P < 0.001). But in the fentanyl group, baseline values were comparable to those 2 min post-intubation for DBP and MAP.

The sympathetic response to laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation is well-reported.[7,8] Many studies have investigated different drugs and routes used to blunt the haemodynamic stress response to laryngoscopy, like magnesium, esmolol, fentanyl, lignocaine, α-agonists and many more.[2,3] Many studies have compared IV dexmedetomidine, fentanyl and MgSO4 together or for attenuating response to intubation.[2,9-14] In this study, we used nebulisation to administer the drugs. Any drug given by the nebulised route has lesser side effects than the IV route because of lesser systemic absorption; drug administration by the nebulised route avoids cough, vocal cord irritation, and laryngospasm, which are observed in the intranasal route.[15] Also, nebulisation allows higher bioavailability and greater ease of administration.[5,6]

Nebulised form of the drug has been used to attenuate pressor response in two studies on dexmedetomidine (1 μg/kg)[4,16] and one study on magnesium (240 mg).[5] Nebulised fentanyl has been used to relieve postoperative pain but not for pressor response.[6] Fentanyl, a μ-opioid receptor agonist, has been commonly used as premedication to suppress the stress response.[17,18] However, various studies combine fentanyl with other drugs or use a higher dose of fentanyl >2 μg/kg for attenuation of stress response to intubation, hence correlating with the fact that a dose of 2 μg/kg IV of fentanyl is not enough to suppress the stress response.[16,19,20] In our study, one of the groups received 1 μg/kg nebulised fentanyl as an approach for attenuation of pressor response; a lower dose was used on account of IV fentanyl 2 μg/kg that was already given as premedication. Also, a study compared nebulised fentanyl 2 μg/kg and dexmedetomidine 2 μg/kg and found that fentanyl showed better results than dexmedetomidine.[21] Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective α2 (α2:α1–1620:1) adrenergic receptor agonist which causes a decrease in systemic noradrenaline release and an increase in vagal activity,[20,21] resulting in attenuation of sympathoadrenal responses and haemodynamic stability during laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation. Dexmedetomidine in nebulised form has a bioavailability of 65% through the nasal mucosa and 82% through the buccal mucosa.[15] A dose of 1 μg/kg of dexmedetomidine was chosen in this study as it proved to be clinically effective both by the intranasal and IV routes in previous clinical study.[21] Calcium releases catecholamines from the adrenal medulla and adrenergic nerve terminals, generating a sympathetic response. MgSO4 competes with calcium to bind to the channels, acting as calcium antagonists. Hence, magnesium blocks the release of catecholamines and decreases response to adrenergic stimulations.[22] Administering MgSO4 at a dose of <50 mg/kg to attenuate haemodynamic response to intubation was remarkably effective.[10,13]

Misra et al.[16] found a lower trend of increase in HR in the dexmedetomidine group versus the saline group (P value 0.012), but in our study, in the dexmedetomidine group, there was no significant change in HR at T2 compared to T0. They also found no difference in SBP changes between the two groups (P = 0.904), similar to our study. Kumar et al.[4] found a statistically significant (P < 0.05) decrease in SBP, DBP and MAP at 1, 5 and 10 min after intubation in the nebulised dexmedetomidine group compared to normal saline nebulisation. However, HR was not compared in this study. Similar results were found in our research about SBP, DBP and MAP. Elmeligy and Elmeliegy[5] found that there was significant (P < 0.001) attenuation of HR increase immediately post-intubation and 3 and 6 min after intubation when patients were nebulised by magnesium (P < 0.001). Similar results were found in our study.

Our study has the following limitations: the results cannot be extrapolated to high-risk patients with comorbidities; neuromuscular monitoring like a train of four and depth of anaesthesia monitoring like bispectral index was not used; different doses of the particular drug were not compared. Lower doses of nebulised magnesium (30 mg/kg) can be used in further studies to minimise the side effects.[5] The dose of fentanyl in the nebulisation route may be controversial for showing inferior results, as doses of 3–4 μg/kg have also been used in earlier studies.[6]

CONCLUSION

Nebulised dexmedetomidine (1 μg/kg), magnesium sulphate (40 mg/kg) and fentanyl (1 μg/kg) seem to effectively blunt the stress response to laryngoscopy and intubation with minimal adverse effects. Hence, these drugs may serve as an alternative to fentanyl to attenuate pressor response.

Study data availability

De-identified data may be requested with reasonable justification from the authors (email to the corresponding author) and shall be shared after approval as per the authors’ institution policy.

Financial support and sponsorship

ESIC Medical College, NH-3, Faridabad

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lakhe G, Pradhan S, Dhakal S. hemodynamic response to laryngoscopy and intubation using McCoy laryngoscope: A descriptive cross-sectional study. J Nepal Med Assoc. 2021;59:554–7. doi: 10.31729/jnma.6752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teong CY, Huang CC, Sun FJ. The haemodynamic response to endotracheal intubation at different times of fentanyl given during induction: A randomised controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2020;10:8829. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-65711-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganesan P, Balachander H, Elakkumanan LB. Evaluation of nebulised lignocaine versus intravenous lignocaine for attenuation of pressor response to laryngoscopy and intubation. Curr Med Issues. 2020;18:184–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar NR, Jonnavithula N, Padhy S, Sanapala V, VasramNaik V. Evaluation of nebulised dexmedetomidine in blunting haemodynamic response to intubation: A prospective randomised study. Indian J Anaesth. 2020;64:874–9. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_235_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elmeligy MSM, Elmeliegy MFM. Effect of magnesium sulfate nebulization on stress response induced tracheal intubation;Prospective, randomized study. Open J Anesth. 2021;11:128–35. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh AP, Jena SS, Meena RK, Tewari M, Rastogi V. Nebulised fentanyl for postoperative pain relief, a prospective double-blind controlled randomised clinical trial. Indian J Anaesth. 2013;57:583–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.123331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheth AP, Hathiwala H, Shah D. Effect of dexmedetomidine by nebuliser for blunting stress response to direct laryngoscopy and intubation. Int J Med Anaesth. 2021;4:76–80. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ismail EA, Mostafa AA, Abdelatif MM. Attenuation of hemodynamic response to laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation with single dose dexmedetomidine in controlled hypertensive patients: A prospective randomized, double-blind study. Ain-Shams J Anesthesiol. 2022;14:57. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shukla S, Kadni RR, Chakravarthy JJ, Zachariah KV. A comparative study of intravenous low doses of dexmedetomidine, fentanyl, and magnesium sulfate for attenuation of hemodynamic response to endotracheal intubation. Indian J Pharmacol. 2022;54:314–20. doi: 10.4103/ijp.ijp_923_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahajan L, Kaur M, Gupta R, Aujla KS, Singh A, Kaur A. Attenuation of the pressor responses to laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation with intravenous dexmedetomidine versus magnesium sulphate under bispectral index-controlled anaesthesia: A placebo-controlled prospective randomised trial. Indian J Anaesth. 2018;62:337–43. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_1_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silpa AR, Koshy KA, Subramanian A, Pradeep KK. Comparison of the efficacy of two doses of dexmedetomidine in attenuating the hemodynamic response to intubation in patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery: A randomised double-blinded study. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2020;36:83–7. doi: 10.4103/joacp.JOACP_235_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tarsis S, Mahilamani P, Thavamani A. The comparative efficacy of intravenous dexmedetomidine versus lidocaine in attenuation of stress response during intubation at tertiary care hospital. EAS J Anesthesiol Crit Care. 2019;5:94–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jain P, Bikrol A, Arora KK, Nema M. Effect of single bolus dose of intravenous magnesium sulfate in attenuating hemodynamic stress response to laryngoscopy and nasotracheal intubation in maxillofacial surgeries. Asian J Med Sci. 2022;8:41–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahiswar AP, Dubey PK, Ranjan A. Comparison between dexmedetomidine and fentanyl bolus in attenuating the stress response to laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation: A randomized double-blind trial. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2022;72:103–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2021.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farzal Z, Basu S, Burke A, Fasanmade OO, Lopez EM, Bennett WD, et al. Comparative studies of simulated nebulized and spray particle deposition in chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019;9:746–58. doi: 10.1002/alr.22324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Misra S, Behera BK, Mitra JK, Sahoo AK, Jena SS, Srinivasan A. Effect of preoperative dexmedetomidine nebulization on the hemodynamic response to laryngoscopy and intubation: A randomized control trial. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2021;74:150–7. doi: 10.4097/kja.20153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohan H, Rajkumar V, Mani V, Bharath S. A comparative study on fentanyl, morphine and nalbuphine in attenuating stress response and serum cortisol levels during endotracheal intubation. Eur J Mol Clin Med. 2022;2:585–95. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yılmaz E, Kadıoğulları N, Menteş S. Comparison of the effects of fentanyl and dexmedetomidine administered in different doses on hemodynamic responses during intubation. Haydarpasa Numune Med J. 2022;62:417–23. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah B, Jaykar S, Govekar S, Jacob R, Kapoor S, Birajdar S, et al. A comparative study of two different doses of fentanyl 2 mcg/kg and 4 mcg/kg in attenuating the hemodynamic stress response during laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation. Indian J Anesth Analg. 2020;7:375–81. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eniya P, Arutselvan US, Anusha A. Comparison of intravenous lignocaine and dexmedetomidine for attenuation of hemodynamic stress response to laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation. Indian J Anesth Analg. 2020;7:873–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niyogi S, Biswas A, Chakraborty I, Chakraborty S, Acharjee A. Attenuation of haemodynamic responses to laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation with dexmedetomidine: A comparison between intravenous and intranasal route. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63:915–23. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_320_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cavalcanti IL, Lima FLT, Silva MJS, Cruz Filho RA, Braga ELC, Verçosa N. Use profile of magnesium sulfate in anesthesia in Brazil. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:429. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]