Abstract

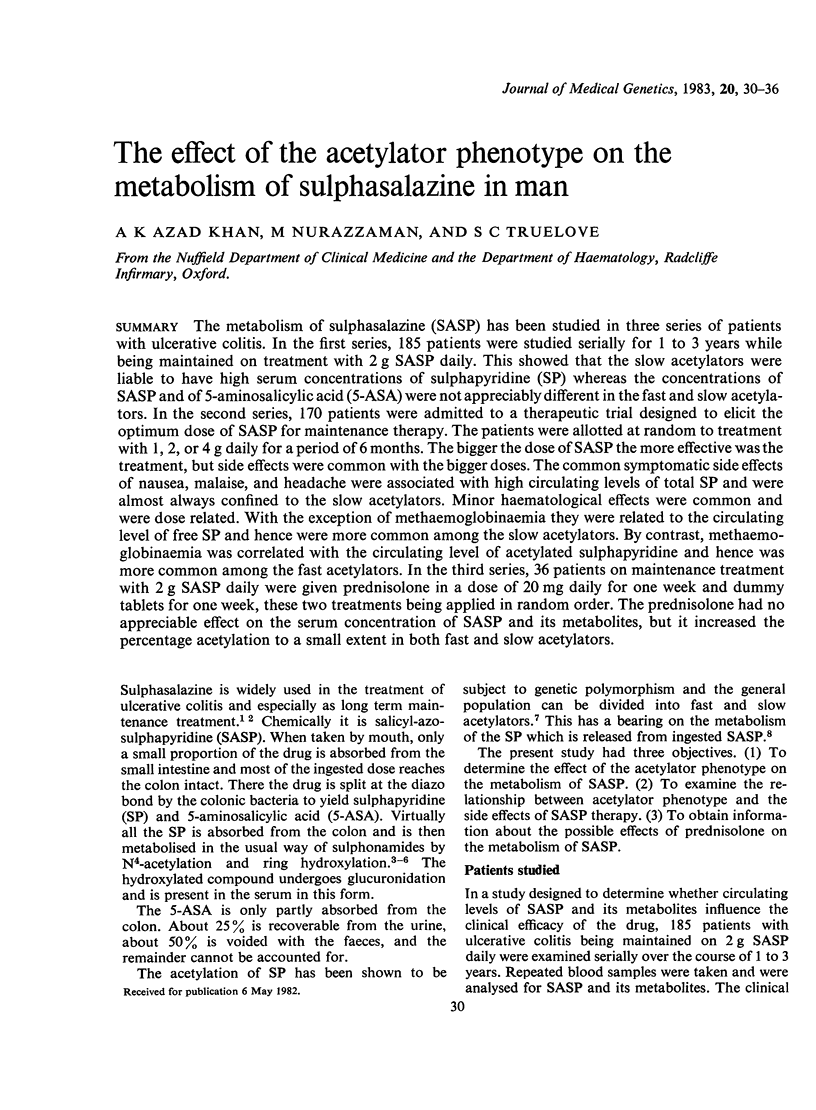

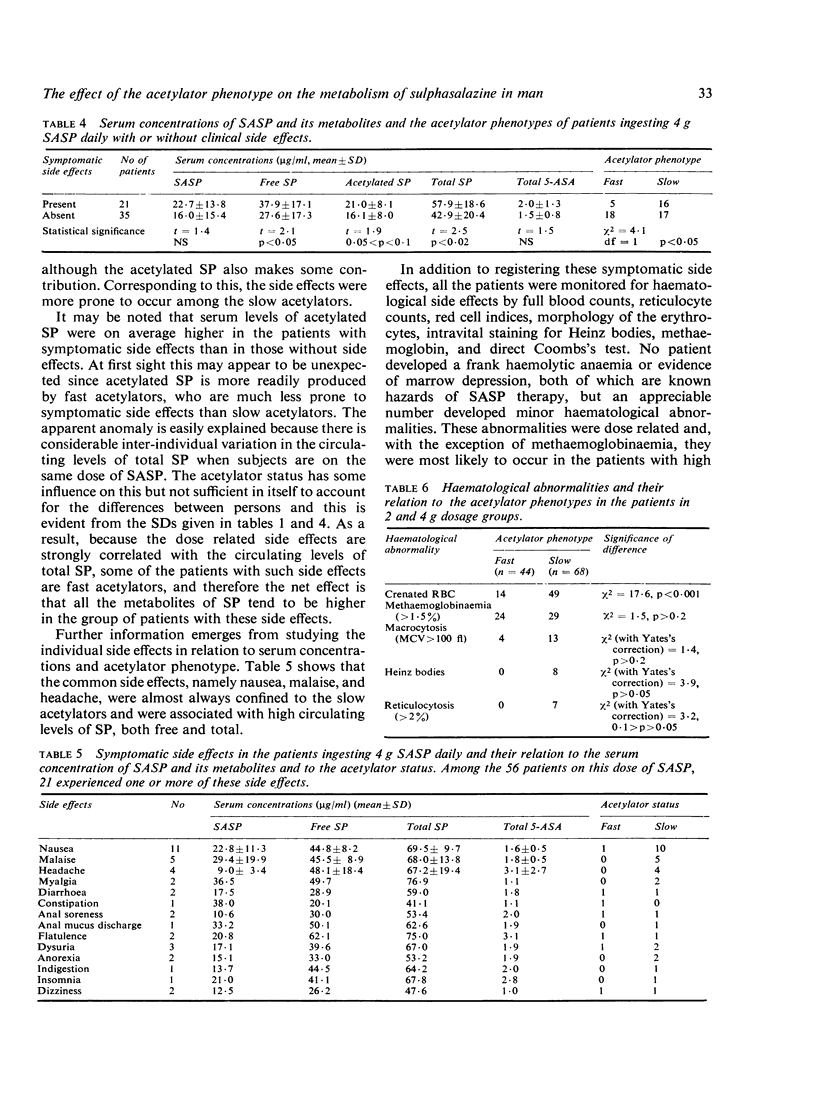

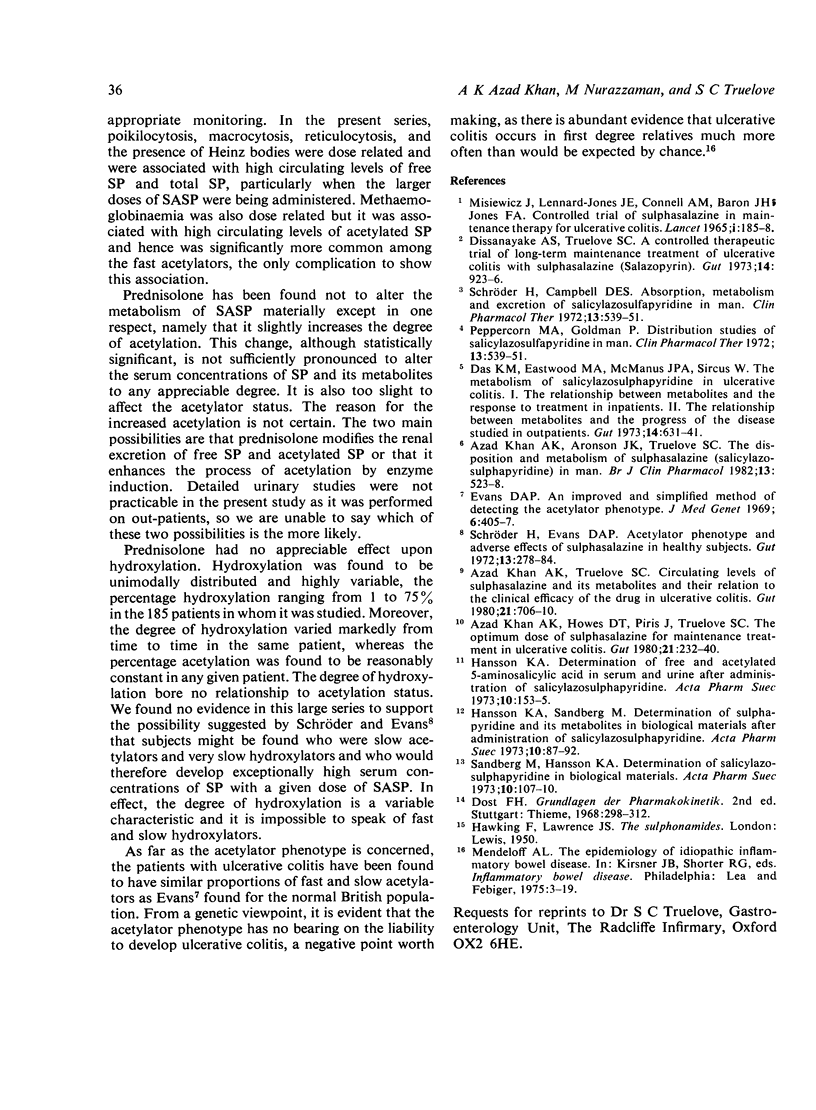

The metabolism of sulphasalazine (SASP) has been studied in three series of patients with ulcerative colitis. In the first series, 185 patients were studied serially for 1 to 3 years while being maintained on treatment with 2 g SASP daily. This showed that the slow acetylators were liable to have high serum concentrations of sulphapyridine (SP) whereas the concentrations of SASP and of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) were not appreciably different in the fast and slow acetylators. In the second series, 170 patients were admitted to a therapeutic trial designed to elicit the optimum dose of SASP for maintenance therapy. The patients were allotted at random to treatment with 1, 2, or 4 g daily for a period of 6 months. The bigger the dose of SASP the more effective was the treatment, but side effects were common with the bigger doses. The common symptomatic side effects of nausea, malaise, and headache were associated with high circulating levels of total SP and were almost always confined to the slow acetylators. Minor haematological effects were common and were dose related. With the exception of methaemoglobinaemia they were related to the circulating level of free SP and hence were more common among the slow acetylators. By contrast, methaemoglobinaemia was correlated with the circulating level of acetylated sulphapyridine and hence was more common among the fast acetylators. In the third series, 36 patients on maintenance treatment with 2 g SASP daily were given prednisolone in a dose of 20 mg daily for one week and dummy tablets for one week, these two treatments being applied in random order. The prednisolone had no appreciable effect on the serum concentration of SASP and its metabolites, but it increased the percentage acetylation to a small extent in both fast and slow acetylators.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Azad Khan A. K., Howes D. T., Piris J., Truelove S. C. Optimum dose of sulphasalazine for maintenance treatment in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1980 Mar;21(3):232–240. doi: 10.1136/gut.21.3.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azad Khan A. K., Truelove S. C. Circulating levels of sulphasalazine and its metabolites and their relation to the clinical efficacy of the drug in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1980 Aug;21(8):706–710. doi: 10.1136/gut.21.8.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azadkhan A. K., Truelove S. C., Aronson J. K. The disposition and metabolism of sulphasalazine (salicylazosulphapyridine) in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1982 Apr;13(4):523–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1982.tb01415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das K. M., Eastwood M. A., McManus J. P., Sircus W. The metabolism of salicylazosulphapyridine in ulcerative colitis. I. The relationship between metabolites and the response to treatment in inpatients. Gut. 1973 Aug;14(8):631–641. doi: 10.1136/gut.14.8.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake A. S., Truelove S. C. A controlled therapeutic trial of long-term maintenance treatment of ulcerative colitis with sulphazalazine (Salazopyrin). Gut. 1973 Dec;14(12):923–926. doi: 10.1136/gut.14.12.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. A. An improved and simplified method of detecting the acetylator phenotype. J Med Genet. 1969 Dec;6(4):405–407. doi: 10.1136/jmg.6.4.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson K. A. Determination of free and acetylated 5-aminosalicylic acid in serum and urine after administration of salicylazosulphapyridine. Acta Pharm Suec. 1973 May;10(2):153–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson K. A., Sandberg M. Determination of sulphapyridine and its metabolites in biological materials after administration of salicylazosulphapyridine. Acta Pharm Suec. 1973 Mar;10(1):87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg M., Hansson K. A. Determination of salicylazosulphapyridine in biological materials. Acta Pharm Suec. 1973 May;10(2):107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder H., Campbell D. E. Absorption, metabolism, and excretion of salicylazosulfapyridine in man. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1972 Jul-Aug;13(4):539–551. doi: 10.1002/cpt1972134539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder H., Campbell D. E. Absorption, metabolism, and excretion of salicylazosulfapyridine in man. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1972 Jul-Aug;13(4):539–551. doi: 10.1002/cpt1972134539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder H., Evans D. A. Acetylator phenotype and adverse effects of sulphasalazine in healthy subjects. Gut. 1972 Apr;13(4):278–284. doi: 10.1136/gut.13.4.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TITMUSS R. M. ROLE OF THE FAMILY DOCTOR TODAY IN THE CONTEXT OF BRITAIN'S SOCIAL SERVICES. Lancet. 1965 Jan 2;1(7375):1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(65)90918-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]