The last dozen years have seen a surge in research pertaining to environmental health literacy (EHL), or people’s knowledge and understanding of health threats around them, as well as relevant prevention and risk-reduction strategies.1,2 Concomitantly, research productivity has increased related to the design and evaluation of report-back strategies that inform study participants of exposure-related biological and/or environmental findings at both the individual and community levels.3 A simple PubMed search underscores substantial growth in peer-reviewed publications for both EHL and exposure report-back research in recent years.

The study of EHL has emerged and evolved in large part through translational and community engagement efforts advanced by university-based, federally funded environmental health research centers, as well as through individual grants focused on environmental exposure assessment.4,5 Although centers and grants also have contributed to recent growth in research about exposure report-back, the act of reporting study findings back to participants has been a central tenet of community-based and community-engaged research for decades,6,7 with academic institutional review boards sometimes creating structural barriers to the process.8 Both EHL and report-back share common goals: understanding and reducing human exposures to harmful contaminants and improving health outcomes for people who already have experienced environmental exposures.9–11 Given this shared foundation, it is unsurprising that a number of scholars—including Boronow et al., reporting in this issue of Environmental Health Perspectives12—conduct research that spans both EHL and report-back.13–15 Importantly, such intersections of content and expertise exist not just within academic institutions and communities but also across them.16–19

From my perspective, such collaborations indicate recognition of an ethical imperative to share data and learn with people potentially affected by environmental exposures, thereby helping reduce risk and better manage these exposures and related health outcomes. In addition, I believe these research partnerships also indicate a desire to build evidence for how best to accomplish these goals. It is no accident that some research teams, including Boronow et al., use EHL metrics to evaluate the impact of report-back materials20–22 or that other research teams deploy assessments of EHL to inform targeted messaging that supports the accessibility, understandability, and actionability of report-back materials.23–25 Together, these different types of studies strongly imply a bidirectional relationship between the goals and outcomes of EHL and exposure-related report-back.

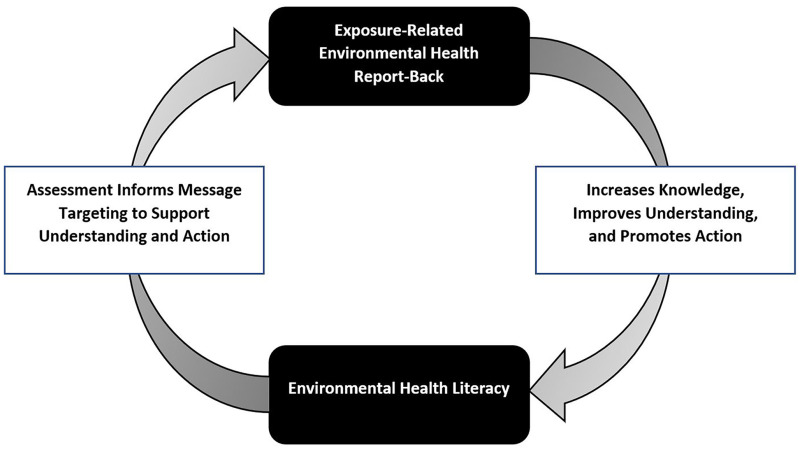

With the growth of and linkages between these two critically important environmental health research areas, perhaps the time has come to articulate a formal conceptual model of the relationship that can help inform future research, practice, and evaluation. An initial attempt at producing such a model illustrates the iterative processes and goals that connect EHL and exposure-related report-back (Figure 1). In short, by knowing current EHL levels, researchers can reach target populations with improved exposure report-back to ensure that research participants understand the informational materials, which themselves then become tools for building the additional knowledge and understanding that comprise EHL.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model illustrating communication and educational connections between environmental health literacy and exposure-related environmental health report-back.

The work described by Boronow et al. implicitly reflects such a change model, connecting information-sharing and knowledge-building through distinct communication and educational processes, respectively. Their article acknowledges the importance of including participants and community partners at each stage of study design and implementation to optimize impact, finding both promising levels of foundational EHL among research participants and the ability of exposure-related report-back to correct misconceptions. When we explicitly articulate these connections within a shared conceptual model, we can better delineate and promote the complementary roles of environmental and health scientists, communication and STEM researchers, study participants, community leaders, and others in developing effective report-back strategies that can help build EHL, prompt action, and protect environmental public health. By increasing levels of knowledge, concern, and action, Boronow et al. add to the evidence for building a conceptual model that explicitly connects evolving research on EHL and report-back, thereby pointing the way for future work at the convergence of these exciting research areas.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks E. Hahn, E. Haynes, B. May, L. Ormsbee, K. Pennell, and S. Stanifer at the University of Kentucky for their timely feedback on this manuscript. She also expresses gratitude to the numerous scientific collaborators from Kentucky’s communities and universities, as well as the NIEHS Partnerships for Environmental Public Health network, who have informed her understanding of and approaches to these topics over nearly two decades.

The author has conducted relevant research through several funding mechanisms. Support for these studies has been provided by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS)/National Institutes of Health (NIH) (5P42ES007380; 5P30ES026529; 1R01ES030380; 1R01 ES032396; 2P42ES007380), the National Library of Medicine/NIH (G08LM013185-01), and the National Institute on Drug Abuse/NIH (1U01DA053903).

Refers to https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP12565

References

- 1.Finn S, O’Fallon L. 2017. The emergence of environmental health literacy—from its roots to its future potential. Environ Health Perspect 125(4):495–501, PMID: , 10.1289/ehp.1409337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoover AG. 2019. Defining environmental health literacy. In: Environmental Health Literacy. Finn S, O’Fallon L, eds. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 3–18, 10.1007/978-3-319-94108-0_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brody JG, Morello-Frosch R, Brown P, Rudel RA, Altman RG, Frye M, et al. 2007. Improving disclosure and consent: “is it safe?”: new ethics for reporting personal exposures to environmental chemicals. Am J Public Health 97(9):1547–1554, PMID: , 10.2105/AJPH.2006.094813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoover E, Renauld M, Edelstein MR, Brown P. 2015. Social science collaboration with environmental health. Environ Health Perspect 123(11):1100–1106, PMID: , 10.1289/ehp.1409283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray KM. 2018. From content knowledge to community change: a review of representations of environmental health literacy. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(3):466, PMID: , 10.3390/ijerph15030466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.López ED, Brakefield-Caldwell W. 2005. Disseminating research findings back to partnering communities: lessons learned from a community-based participatory research approach. Metrop Univ J 16:59–76. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morello-Frosch R, Brody JG, Brown P, Altman RG, Rudel RA, Pérez C. 2009. Toxic ignorance and right-to-know in biomonitoring results communication: a survey of scientists and study participants. Environ Health 8:6, PMID: , 10.1186/1476-069X-8-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown P, Morello-Frosch R, Brody JG, Altman RG, Rudel RA, Senier L, et al. 2010. Institutional review board challenges related to community-based participatory research on human exposure to environmental toxins: a case study. Environ Health 9:39, PMID: , 10.1186/1476-069X-9-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Fallon LR, Collman GW, Dearry A. 2000. The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences’ research program on children’s environmental health. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 10(6 Pt 2):630–637, PMID: , 10.1038/sj.jea.7500117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finn S, Collman G. 2016. The pivotal role of the social sciences in environmental health sciences research. New Solut 26(3):389–411, PMID: , 10.1177/1048291116666485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trottier BA, Carlin DJ, Heacock ML, Henry HF, Suk WA. 2019. The importance of community engagement and research translation within the NIEHS Superfund Research Program. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(17):3067, PMID: , 10.3390/ijerph16173067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boronow KE, Cohn B, Havas L, Plumb M, Brody JG. 2021. The effect of individual or study-wide report-back on knowledge, concern, and exposure-reducing behaviors related to endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Environ Health Perspect 131(9):097005, 10.1289/EHP12565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandhaus S, Kaufmann D, Ramirez-Andreotta M. 2019. Public participation, trust and data sharing: gardens as hubs for citizen science and environmental health literacy efforts. Int J Sci Educ B Commun Public Engagem 9(1):54–71. 2, PMID: , 10.1080/21548455.2018.1542752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dellinger MJ, Lyons M, Clark R, Olson J, Pingatore N, Ripley M. 2019. Culturally adapted mobile technology improves environmental health literacy in Laurentian, Great Lakes Native Americans (Anishinaabeg). J Great Lakes Res 45(5):969–975, PMID: , 10.1016/j.jglr.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanifer S, Hoover AG, Rademacher K, Rayens MK, Haneberg W, Hahn EJ. 2022. Citizen science approach to home radon testing, environmental health literacy and efficacy. Citiz Sci 7(1):26, PMID: , 10.5334/cstp.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramirez-Andreotta MD, Brody JG, Lothrop N, Loh M, Beamer PI, Brown P. 2016. Reporting back environmental exposure data and free choice learning. Environ Health 15:2, PMID: , 10.1186/s12940-015-0080-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray KM, Triana V, Lindsey M, Richmond B, Hoover AG, Wiesen C. 2021. Knowledge and beliefs associated with environmental health literacy: a case study focused on toxic metals contamination of well water. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(17):9298, PMID: , 10.3390/ijerph18179298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohlman D, Samon S, Allan S, Barton M, Dixon H, Ghetu C, et al. 2022. Designing equitable, transparent, community-engaged disaster research. Citiz Sci 7(1):22, PMID: , 10.5334/cstp.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perovich LJ, Ohayon JL, Cousins EM, Morello-Frosch R, Brown P, Adamkiewicz G, et al. 2018. Reporting to parents on children’s exposures to asthma triggers in low-income and public housing, an interview-based case study of ethics, environmental literacy, individual action, and public health benefits. Environ Health 17(1):48, PMID: , 10.1186/s12940-018-0395-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown P, Brody JG, Morello-Frosch R, Tovar J, Zota AR, Rudel RA. 2012. Measuring the success of community science: the northern California Household Exposure Study. Environ Health Perspect 120(3):326–331, PMID: , 10.1289/ehp.1103734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramirez-Andreotta MD, Brody JG, Lothrop N, Loh M, Beamer PI, Brown P. 2016. Improving environmental health literacy and justice through environmental exposure results communication. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13(7):690, PMID: , 10.3390/ijerph13070690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomsho KS, Basra K, Rubin SM, Miller CB, Juang R, Broude S, et al. 2018. Community reporting of ambient air polychlorinated biphenyl concentrations near a superfund site. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 25(17):16389–16400, PMID: , 10.1007/s11356-017-0286-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lichtveld MY, Covert HH, Sherman M, Shankar A, Wickliffe JK, Alcala CS. 2019. Advancing environmental health literacy: validated scales of general environmental health and environmental media-specific knowledge, attitudes and behaviors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(21):4157, PMID: , 10.3390/ijerph16214157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoover AG, Koempel A, Christian WJ, Tumlin KI, Pennell KG, Evans S, et al. 2020. Appalachian environmental health literacy: building knowledge and skills to protect health. J Appalach Health 2(1):47–53, PMID: , 10.13023/jah.0201.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rohlman D, Kile ML, Irvin VL. 2022. Developing a Short Assessment of Environmental Health Literacy (SA-EHL). Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(4):2062, PMID: , 10.3390/ijerph19042062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]