Abstract

The hypothalamic melanocortin system is critically involved in sensing stored energy and communicating this information throughout the brain, including to brain regions controlling motivation and emotion. This system consists of first-order agouti-related peptide (AgRP) and pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons located in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus and downstream neurons containing the melanocortin-3 (MC3R) and melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R). Although extensive work has characterized the function of downstream MC4R neurons, the identity and function of MC3R-containing neurons are poorly understood. Here, we used neuroanatomical and circuit manipulation approaches in mice to identify a novel pathway linking hypothalamic melanocortin neurons to melanocortin-3 receptor neurons located in the paraventricular thalamus (PVT) in male and female mice. MC3R neurons in PVT are innervated by hypothalamic AgRP and POMC neurons and are activated by anorexigenic and aversive stimuli. Consistently, chemogenetic activation of PVT MC3R neurons increases anxiety-related behavior and reduces feeding in hungry mice, whereas inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons reduces anxiety-related behavior. These studies position PVT MC3R neurons as important cellular substrates linking energy status with neural circuitry regulating anxiety-related behavior and represent a promising potential target for diseases at the intersection of metabolism and anxiety-related behavior such as anorexia nervosa.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Animals must constantly adapt their behavior to changing internal and external challenges, and impairments in appropriately responding to these challenges are a hallmark of many neuropsychiatric disorders. Here, we demonstrate that paraventricular thalamic neurons containing the melanocortin-3 receptor respond to energy-state-related information and external challenges to regulate anxiety-related behavior in mice. Thus, these neurons represent a potential target for understanding the neurobiology of disorders at the intersection of metabolism and psychiatry such as anorexia nervosa.

Keywords: anxiety, feeding behavior, MC3R, melanocortins, paraventricular thalamus

Introduction

Animals must constantly adapt their behavior to changing internal (i.e., hunger/satiety) and environmental challenges (i.e., threats in the environment), and select the appropriate behavioral response to underlying needs. For example, although increased behavioral approach and food seeking is necessary to prevent starvation in hungry animals, the same behavior is not adaptive in sated animals as this may result in exposure to predators or injury (Burnett et al., 2016, 2019; Sutton and Krashes, 2020). Inappropriate behavioral responses to internal and external challenges commonly occur in multiple neuropsychiatric disorders, such as anorexia nervosa (AN), anxiety disorders, and mood disorders. In the case of AN, patients do not appropriately seek and consume food despite severe hunger as the psychosocial stress and stigma associated with food consumption presumably override the homeostatic drive to eat (Keski-Rahkonen et al., 2007; Herpertz-Dahlmann et al., 2012). Thus, it is of critical importance to understand the downstream neural circuitry mediating behavioral responses to hunger, particularly given the lack of effective therapeutics for neuropsychiatric eating disorders (Hay et al., 2012).

The central melanocortin system consists of agouti-related protein (AgRP) and pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus, which sense stored energy in the form of leptin from fat, gut-derived satiety hormones and glucose levels in the blood (Cone, 2005; Garfield et al., 2009). AgRP neurons are activated during hunger (Takahashi and Cone, 2005), resulting in the release of the melanocortin receptor antagonist AgRP at downstream brain regions containing melanocortin receptor 3 or 4 (Cone, 2005, 2006). Conversely, POMC neurons are activated in the satiated state (Cowley et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2015; Mandelblat-Cerf et al., 2015) or in response to stress (Liu et al., 2007; Qu et al., 2020), resulting in the release of the melanocortin receptor agonist alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone (aMSH). Further, AgRP and POMC neurons are rapidly modulated by the sight of food and/or by cues predicting food availability (Betley et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2015; Mandelblat-Cerf et al., 2015; Beutler et al., 2017; Su et al., 2017), indicating that these neurons sense both current physiological state and predicted outcomes to adaptively control behavior. Chemogenetic and optogenetic activation of AgRP and POMC neurons produces opposing effects on feeding and behavior, with AgRP neuron stimulation increasing feeding (Aponte et al., 2011; Krashes et al., 2011, 2013) and reducing anxiety-related behavior (Dietrich et al., 2015; Burnett et al., 2016, 2019; Padilla et al., 2016; Li et al., 2019), and POMC neuron stimulation reducing feeding (Zhan et al., 2013) and increasing anxiety-related behavior (Lee et al., 2020; Qu et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2021). Thus, POMC and AgRP neurons sense the energy state of the animal and environmental conditions predicting food availability in real time and communicate this information to downstream melanocortin-receptor-expressing neurons to initiate an appropriate behavioral response to hunger or satiety. However, the cell types and neural circuits mediating downstream behavioral responses to hunger and satiety are incompletely understood.

An extensive literature has characterized the critical role of MC4R in mediating the anorexic effects of melanocortins (Cone, 2005; Krashes et al., 2016) as global deletion of MC4R leads to hyperphagic obesity in both rodents (Huszar et al., 1997) and humans (Farooqi et al., 2000; Vaisse et al., 2000; Farooqi et al., 2003). AgRP and POMC neurons project to MC4R-containing neurons in the paraventricular hypothalamus (PVN) where aMSH activates MC4R to reduce feeding, while AgRP inhibits MC4R to increase feeding (Fenselau et al., 2017; Ghamari-Langroudi et al., 2015; Cone, 2005; Sweeney et al., 2021a; Shah et al., 2014). In contrast to MC4R, MC3R knock-out mice exhibit a complicated metabolic and endocrine phenotype characterized by minor late-onset obesity, defective fast-induced refeeding, increased anxiety, delayed puberty and growth, and an enhanced response to anorexic stimuli (Butler et al., 2000; Sweeney et al., 2021b; Ghamari-Langroudi et al., 2018; Lam et al., 2021). Although MC3R is expressed throughout the brain, the specific function of MC3R is unknown in most MC3R-containing sites (Bedenbaugh et al., 2022).

One candidate MC3R-containing site for mediating downstream behavioral effects of AgRP and POMC neurons is the paraventricular thalamic nucleus (PVT). AgRP and POMC neurons project densely throughout the PVT (Betley et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015), and activation of AgRP projections to the PVT increases feeding (Betley et al., 2013) while also prioritizing attention and cognition toward smells and cues associated with food versus nonfood objects (Livneh et al., 2017; Horio and Liberles, 2021). Prior studies support an important role for PVT circuits in regulating motivation (Labouèbe et al., 2016; Campus et al., 2019; Choi et al., 2019; Otis et al., 2019; Hill-Bowen et al., 2020; McNally, 2021), anxiety (Kirouac, 2015, 2021; Penzo et al., 2015; Choi and McNally, 2017; Levine et al., 2021), and aversive behavior (Kirouac, 2015; Penzo et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2016; Levine et al., 2021) and for balancing reward seeking with threat avoidance (Kirouac, 2015; Choi and McNally, 2017; Choi et al., 2019; Hill-Bowen et al., 2020; McNally, 2021; Penzo and Gao, 2021). Thus, the PVT is a critical neural structure mediating adaptive behavioral responses to underlying needs and environmental conditions (Choi and McNally, 2017; Choi et al., 2019; Meffre et al., 2019; Otis et al., 2019; Hill-Bowen et al., 2020; McGinty and Otis, 2020; McNally, 2021). However, although previous work has established the importance of hypothalamic-derived peptides (i.e., orexin) in regulating anxiety-related behavior in PVT (Li et al., 2010a, b; Heydendael et al., 2011; Meffre et al., 2019), the specific cell types in PVT linking energy homeostasis to anxiety-related behavior are unknown. Here, we use a combination of circuit manipulation approaches, neuroanatomy, molecular genetics, and in vivo imaging to characterize a novel role of PVT MC3R neurons in controlling anxiety-related behavior.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the University of Illinois Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All experiments were performed on littermate mice that were approximately matched for age and body weight between experimental and control groups. Experiments were performed on an approximate equal amount of male and female mice (depending on the number of each sex generated during breeding). For illustrating main effects of manipulations, data from both sexes are collapsed in the main text figures, and any interactions between sex and outcome variables are also illustrated in main text figures. Transgenic mouse lines included MC4R-Cre (catalog #030759, The Jackson Laboratory), MC3R-Cre (Ghamari-Langroudi et al., 2018), MC3R floxed, and tdtomato floxed (catalog #007914, The Jackson Laboratory). Transgenic MC3R-Cre, MC4R-Cre, and MC3R-Flox mice were genotyped by submitting ear samples to Transnetyx to confirm the presence of Cre and Flox alleles, respectively. Tdtomato mice were bred as homozygous mice and crossed to either MC3R-Cre or MC4R-Cre heterozygous mice to generate either MC4R-Cre; tdtomato or MC3R-Cre; tdtomato transgenic lines. Both MC4R-Cre (Garfield et al., 2015) and MC3R-Cre mice (Ghamari-Langroudi et al., 2018; Sweeney et al., 2021b) have been previously published, and Cre expression was verified to faithfully label MC4R- or MC3R-containing cells (Bedenbaugh et al., 2022), respectively.

MC3R floxed mice were generated by Taconic using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing approaches. Guide RNA to the MC3R gene, donor vector containing loxP sites, and Cas9 mRNA were coinjected into fertilized mouse eggs to generate targeted conditional knock-out offspring. Filial (F)0 founder animals were identified by PCR followed by sequence analysis and were bred to wild-type mice to test germline transmission and F1 animal generation. MC3R floxed mice were bred as heterozygote × heterozygote to generate littermate flox/flox and WT mice for experiments.

Before social isolation, all mice were caged in groups of two to five of the same sex. Mice were housed in temperature-controlled (19–21°C) and humidity-controlled cages. The room was under a 12 h light/dark cycle with the light period beginning at 6:00 A.M. and the dark cycle beginning at 6:00 P.M. All mice had ad libitum access to regular chow and water, unless otherwise noted in the text and figure legends. During experiments that required fasting, the mice were fasted overnight from 4:00 P.M. to 10:00 A.M.

Viral vectors

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors used included Cre-dependent Gcamp8m (AAV1-syn-FLEX-jGCamp8m), Cre-dependent hM3Dq (AAV5-syn-DIO-hM3D-mCherry), Cre-dependent hM4Di (AAV5-hsyn-DIO-hM4D-mCherry), Cre-dependent control virus (AAV5-syn-DIO-mcherry), Cre-dependent Kir 2.1 (AAV-EF1a-DIO-Kir2.1-P2A-dTomato), and Cre-expressing virus (AAV9-hSyn-HI.eGFP Cre). All viral vectors were purchased from Addgene, with the exception of Kir2.1 which was a gift from Benjamin Arenkiel (Baylor University).

Stereotaxic viral injections

In advance to stereotaxic surgery, mice went through anesthesia inside an isoflurane chamber and were positioned in a stereotaxic frame (Kopf) with a constant flow of isoflurane. A dental drill was used to drill a hole on top of the viral injection site, and the dura was removed. The AAV viral vectors were injected into the paraventricular thalamus (PVT) using a micromanipulator (Narishige) attached to a pulled glass pipette with a pipette holder (Ronal Tool). Viral injection coordinates for the PVT were as follows: AP, −0.75 mm and −1.40 mm (from the bregma); ML, 0.0 mm; DV, −3.00 mm, −2.85 mm, and −2.75 mm (from surface of the brain). In each AP coordinate, three injections of viral vectors were delivered in three DV coordinates, and 75 nl of virus was injected in each DV site at a rate of 50 nl/min. After the injection, the glass pipette was left in place for an additional 5 min to prevent leaking of virus from the targeted brain region. For fiber photometry experiments, GCamp8m was injected into PVT using the same injection coordinates and volumes described above. In the same surgery, a 200 um fiber optic fiber (0.66 NA, Plexon) was implanted directly into PVT with the coordinates as follows (AP, −1.20; ML, 0.0; DV, −2.70). Fiber optic cannula were secured to the skull using dental cement (C&B Metabond). Silicone sealant (Kwik-Cast) was used to fill the incision site. Mice were returned to their home cages and went through a recovery period of at least 2 weeks for viral expression and recovery from surgery before the experiments. After the injections, 3 d of carprofen injection was administered subcutaneously (5 mg/kg) to reduce pain.

Perfusion, sectioning, and immunohistochemistry

Following experiments all virally injected mice were perfused with 10% formalin followed by removal of brain tissue. Brains were transferred to a 10% formalin solution for 24 h for further fixation, followed by 24 h of increasing amounts of sucrose concentration (10, 20, and 30%). Brain slices containing PVT were then obtained by sectioning on a Leica (CM3050 S) cryostat at a 40 µm thickness. These sections were then placed into 24 well plates containing 500 µl of blocking buffer (100 ml 1× PBS, 2 g bovine serum albumin, and 100 µl of Tween 20) and placed on a shaker at room temperature and allowed to sit for 2 h. Next, a master mix of the following relevant antibodies: c-fos (9F6 rabbit mAb, 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit AgRP (1:1000; catalog #H-003-57, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals), rabbit POMC (1:1000; catalog #H-029-30, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals) in blocking buffer was prepared. Then 500 µl of this master mix was added to each well containing brain sections and placed onto a shaker in a cold room (4°C) and incubated for 24 h. The primary antibody mixture was then removed and replaced with 500 µl of ultra-pure 1× PBS and placed on a shaker at room temperature for 10 min. The PBS was then replaced with fresh ultra-pure PBS and placed back on the shaker for another 10 min with the process repeated one more time. A 1:500 concentration of secondary antibodies [goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488] was prepared in blocking buffer. After removing the ultra-pure PBS from the well plate, 500 µl of the 1:500 secondary was added to each well and placed on a shaker at room temperature and incubated for an additional 2 h. Following three 10 min wash steps with 1× ultra-pure PBS, the sections were mounted on Superfrost glass slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and imaged with confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM 510).

c-fos Quantification and analysis

For c-fos quantification, tissue was prepared as described above. Injections of CNO (0.3 mg/kg, i.p., 200 μl saline; Enzo Life Sciences) or saline (0.9% NaCL, 200 μl, i.p.) were performed 1 h before perfusion to confirm designer receptor exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADD) mediating activation of PVT MC3R neurons. For fed versus refed analysis, mice were fasted overnight and allowed to refeed for 1 h before perfusion, whereas fed ad libitum mice were perfused at the same time of day but were not fasted. For setmelanotide experiments, setmelanotide (1 mg/kg, i.p., 200 ul saline; catalog #A20689, AdooQ Bioscience) or saline (200 ul, i.p.) was injected 1 h before perfusion, and mice were returned to their home cage after intraperitoneal injections with food and water ad libitum. This time point was chosen (1 h poststimulus) because we previously demonstrated robust c-fos labeling in other cell types expressing hM3Dq DREADD between 30 min to 1 h after CNO injections (Ghamari-Langroudi et al., 2018; Sweeney and Yang, 2015). For each experiment, the overlap between PVT MC3R neurons and c-fos was performed using ImageJ software. The total number of PVT MC3R cells was first counted (labeled with mCherry), and the percentage of these cells coexpressing with c-fos was quantified. For each mouse, we counted overlap from at least three to five representative PVT sections, and an average percentage of overlap was calculated for each mouse from these representative sections for statistical comparison.

RNAscope in situ hybridization and mRNA quantification

RNAscope analysis was performed on C57BL/6J mice. Mice were perfused as described above, and 20 um sections were directly mounted onto Superfrost glass slides for RNAscope in situ hybridization. RNAscope multiplex fluorescent in situ hybridization version 2 protocol was followed according to the protocol described in the kit using the Mm-Mc3r-C2 probes (catalog #412541-C2), Mm-Slc17a6 (catalog #319171), and Mm-Slc32a1 (catalog #319191), and images were obtained via confocal microscopy. The mRNA count was performed using Fiji/ImageJ software, where a region of interest (ROI) was created and placed on the area with high mRNA (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, catalog # 323100) expression in the PVT region. The mRNA was manually counted, and the same ROI size was used for all the images.

Behavioral experiments

Feeding behavior assays

For feeding experiments, mice were single housed for at least 1 week before testing, with the exception of social-isolation-induced anorexia assays (see below). A premeasured amount of food was placed in the food hopper, and the mice were changed to a new cage daily. Food intake was measured at ascending time points by weighing the food in the hopper and subtracting from the original food weight. For chemogenetic experiments injections of CNO (0.3 mg/kg, 200 ul in saline, i.p.) or saline (200 ul, i.p.) were administered 15 min before testing.

Social isolation anorexia

Social isolation anorexia experiments were performed as previously described (Sweeney et al., 2021b; Possa-Paranhos et al., 2023). Briefly, mice were single caged, and food intake was measured 1 h later. On the next day, food intake was measured again at the same time of day, and the difference in food intake on the social isolation day was compared with the following day. For experiments with chemogenetic inhibition, CNO (0.3 mg/kg) was administered 15 min before social isolation.

Open field test

Before beginning open field experiments mice were allowed 30 min to acclimate to the new environment of the behavioral testing room. An open field box (40 × 40 cm), was placed underneath a behavioral tracking camera connected to a Plexon system for tracking mouse movement (Plexon CineLyzer). Mice had not been exposed previously to the open field, and thus this represented a novel experience. The center area of the open field was added to the Plexon system to automatically register when the mice were in the center area of the open field. Mice were then placed in the corner of the open field, and the Plexon system began recording their movement. Mice were allowed to explore the open field for 5 min before being removed. The open field was then cleaned with 70% alcohol before another mouse was added. For experiments involving the injection of CNO, mice were injected 15 min before their entry into the open field. The Plexon system recorded time spent in the center, entries to the center, total distance traveled, and tracked movement in space.

Elevated zero maze

Before the start of the elevated zero maze test (EZM; MazeEngineers) mice were allowed 30 min to acclimate to the new environment of the behavioral testing room. The elevated zero maze consists of a raised circular platform that has two high-walled sections along the circular walkway as well as two no-walled sections. The section of the maze with high walls is considered the closed arms area and is designated as such in the Plexon software. The area with no walls is considered the open-arms area and is again designated as such in the Plexon software. At the start of the test, mice are placed into one of the closed-arms areas and allowed to move freely around the maze for 5 min. During this time the behavioral camera and tracking system monitored the entries of the mice into the open arms, time in open arms, as well as distance traveled and speed. For experiments requiring intraperitoneal injection of CNO, mice were injected 15 min before their entry into the maze. The maze was cleaned with 70% alcohol between each mouse.

Novelty suppressed feeding test

The day before novelty suppressed feeding (NSF) testing, food was removed from the cages, and the mice were placed into fresh cages without food at 4:00 P.M. The following morning mice were brought to the behavioral room at 9:30 A.M. and allowed 30 min to acclimate to the new environment. The same box used for the open field test (OFT) was used for the NSF test, but there was a period of 1 week between the tests to allow for the environment of the box to remain novel. The arena of the box was mapped alongside a center arena where the food pellet was placed. The test began by first placing a new food pellet in the center arena and then placing a mouse in one of the corners of the arena. The mouse was then allowed to explore the environment and consume the food pellet for 10 min. After 10 min the mouse was removed from the arena, and the arena was then cleaned with 70% alcohol before placing a new mouse and pellet in the arena. For experiments requiring intraperitoneal injection of CNO, mice were injected 15 min before their entry into the arena. Latency to consume food was measured after testing for each mouse by visually inspecting NSF videos after testing. Eating was counted when the mouse chewed on the food pellet for at least 5 s.

Order of behavioral and feeding experiments

Following surgical intervention mice were allowed 2 weeks to recover and allow for viral expression. During this period mice were group caged with two to five mice per cage and remained this way until feeding studies were performed. For all cohorts, mice were run through behavioral experiments (i.e., EZM, OFT) while group caged before feeding experiments were performed. The only exception to this was a single cohort of MC3R-Flox mice where social isolation was performed before the beginning of behavioral experiments. Subsequent cohorts of MC3R-Flox mice that had behavioral experiments while group caged showed statistically similar results to the cohort that was single caged before behavioral tests. and as such these cohorts were combined for statistical analysis. Open field tests were performed first followed 1–2 d later by the EZM. Social isolation and feeding experiments followed 3–5 d after the completion of behavioral experiments.

Fiber photometry behavioral studies

Following surgery for GCamp expression and fiber optic placement, mice were allowed 2 weeks to recover and for expression of the GCamp protein. This was followed by a 3–5 d acclimation period. During this period mice were brought into the behavioral room and had an optical patch cable attached and then were allowed to walk freely around their cages for 10 min. Fiber photometry experiments were performed using a Plexon multiwavelength photometry system.

In the water presentation task mice were attached to the fiber optic patch cord, and the calcium signal was recorded for 2 min in the mouse home cage. Following 2 min of baseline recording, mice were introduced to a small piece of Kimwipes soaked in water (5 ml) and placed in a small Petri dish at the corner of the cage. The Petri dish was covered with a lid to prevent the mice from directly contacting the Kimwipe. Changes in signal were recorded for an additional 5 min following the presentation of water. For each mouse the average Z-scored signal and the maximum Z-scored signal was calculated in both the baseline 2 min period and the 5 min period following water exposure. The difference between these two signals (after water minus before water) was calculated for the 5 min following water exposure for each mouse for statistical comparison.

For EZM experiments mice were allowed to explore the elevated zero maze for 5 min while recording calcium activity. Plexon video tracking software automatically scored the time that the mice spent in the open arms versus closed arms during 5 min in the EZM. Calculated times were independently scored manually to confirm the computers calculations. Time in the open arms and time in the closed arms were aligned to the fiber photometry software and the Z-scored average and Z-scored maximum signal was compared for each mouse during the time in the open arms and the time in the closed arms. The difference in this signal (open arms minus closed arms) was calculated for each mouse for statistical comparison.

To record calcium signal changes in response to trimethylthiazoline (TMT) exposure, experiments were performed identically as described for water exposure except that mice were exposed to a Kimwipe containing TMT (5 ml). For acute restraint experiments calcium signal was recorded for 1 min for a baseline recording. Mice were then manually restrained by the experimenter by grabbing the mouse and preventing movement for 10 s. Following this 10 s restraint period, mice were released from restraint and calcium signal was recording for an additional 1 min. The mean and maximum Z-scored calcium signal was calculated for the 1 min baseline period (prerestraint) and for the 10 s restraint period. The change in mean and maximum Z-scored calcium signal was computed for each mouse by subtracting the baseline signal (prerestraint) from the signal during restraint.

Fiber photometry analysis

Fiber photometry numerical and graphical results were tabulated through custom code written in R software using the rshiny package to display a graphical interface. The interface accepts data input via two file selection bars that each accept a CSV file. The first selection bar accepts raw photometry data, and the second accepts event-related data. The raw photometry data CSV file is formatted with three relevant columns that come directly from the Plexon fiber photometry system. These columns include a times tamp, raw 410 nm fluorescence data (isobestic control channel for potential nonspecific effects of motion), and raw 465 nm fluorescence data (GCAMP signal). Through this format of CSV, baseline (410 nm) and signal data (465 nm) are encoded for each time point throughout an experiment and can be manipulated within the program. The second CSV file for events is composed of three relevant columns, an event description (i.e., entering the open arm), an event starting time, and an event ending time. These event segments are superimposed on the fluorescence data. To calculate the Z-score normalized photometry data we first subtracted the control channel (410 nm) from the signal channel (465 nm) and then divided by the control channel. The resultant baseline normalized values were then scaled so that measurements are represented in SDs from a mean. All plots were rendered using the ggplot2 and plotly packages in R. Changes in signal during behavioral experiments were calculated by comparing the average and maximum Z-score of fluorescence during the event versus before the event for water exposure, restraint, and TMT presentation. For EZM tests the mean and maximum Z-score of fluorescent activity was compared during periods where the mice were in the open arms versus periods when they were in the closed arms, and the difference between the open arms and closed arms signals was calculated for each mouse (open arm signal minus closed arm signal).

Data analysis and statistics

All mice with viral injections were perfused and sectioned following experiments. Only animals with viral targeting localized to the PVT were included in analysis. Normality tests were performed on all data to determine whether data followed a normal distribution. Normally distributed data were analyzed with parametric tests, whereas data without a normal distribution were analyzed with nonparametric tests. Specific statistical tests are further outlined in the figure legends. Data were analyzed using GraphPad software.

Results

PVT MC3R neurons are anatomically positioned between hypothalamic melanocortin neurons and subcortical anxiety circuitry

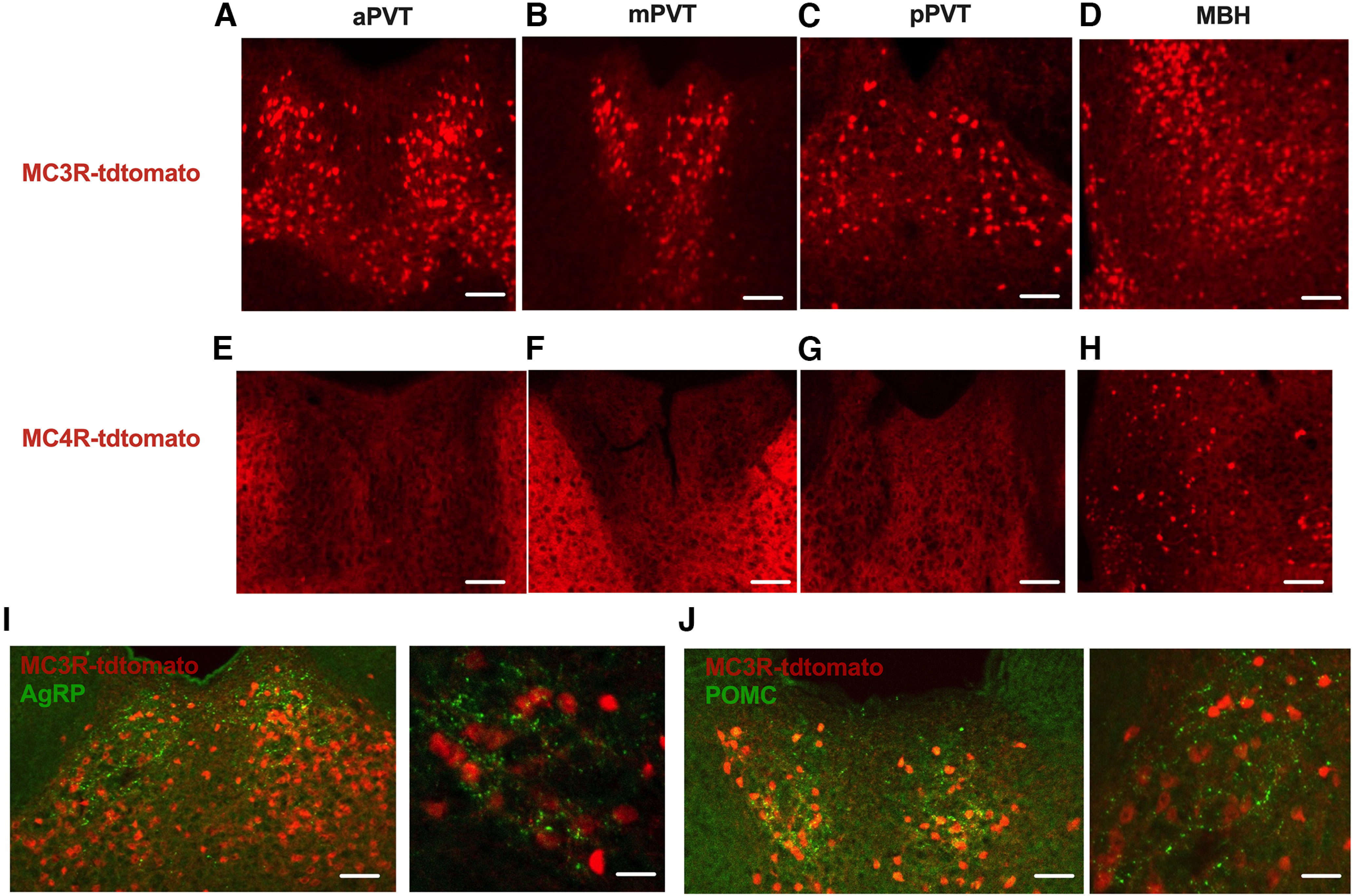

Hypothalamic AgRP and POMC neurons project throughout the brain to secondary sites containing the MC3R and MC4R (Betley et al., 2013; Sternson and Atasoy, 2014; Wang et al., 2015). The paraventricular thalamus is one site that is densely innervated by AgRP and POMC neurons (Betley et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015), although the molecular identity of the postsynaptic cells in PVT is unknown. First, to map the expression of melanocortin receptors in the PVT, we characterized the expression of MC3R- and MC4R-containing cells throughout the anterior–posterior extent of the PVT by using MC3R-Cre or MC4R-Cre mice bred with tdtomato reporter mice. Dense expression of MC3R-containing cells was observed throughout the PVT (Fig. 1A–C) and the medial-basal hypothalamus (Fig. 1D). However, we did not detect MC4R-containing cells in any region of the PVT (Fig. 1E–G) but detected sparse MC4R-containing cells localized in the medial-basal hypothalamus (Fig. 1H). Thus, although both MC3R and MC4R are expressed in the hypothalamus, the paraventricular thalamus exclusively contains MC3R-expressing cells. Next, to determine whether AgRP and POMC neurons innervate MC3R-containing cells in the PVT we performed immunofluorescence for both AgRP and POMC in MC3R-Cre; tdtomato reporter mice (Fig. 1I,J) (Ghamari-Langroudi et al., 2018; Sweeney et al., 2021b). PVT MC3R neurons were densely innervated by both AgRP and POMC immunoreactive fibers (Fig. 1I,J) throughout the extent of PVT. These results suggest a pathway connecting hypothalamic melanocortin neurons to MC3R cells in PVT, although further functional studies are required to establish the functional connectivity between hypothalamic melanocortin neurons and MC3R-containing cells in PVT.

Figure 1.

PVT MC3R neurons are functionally downstream of arcuate AgRP and POMC neurons. A–C, Representative images from transgenic MC3R-cre x tdtomato mouse displaying MC3R distribution along the anterior to posterior axis of the PVT. D, Image of the medial basal hypothalamus (MBH) from the same MC3R-tdotmato mouse. E–G, Representative images from MC4R-cre x tdtomato mice showing lack of MC4R-expressing cells along the anterior to posterior axis of PVT. H, Image of the MBH from the same MC4R-tdtomato mouse verifying the validity of this mouse line for labeling MC4R-containing cells. I, Immunohistochemistry for AgRP in MC3R-Cre x tdtomato transgenic mice. J, Immunohistochemistry for POMC in MC3R-Cre x tdtomato mice. Immunopositive fibers for AgRP and POMC overlap extensively with MC3R cells in PVT. Scale bars: A–H, C (left), 100 um; I, J (left), 100 um; I, J (right), 10 um.

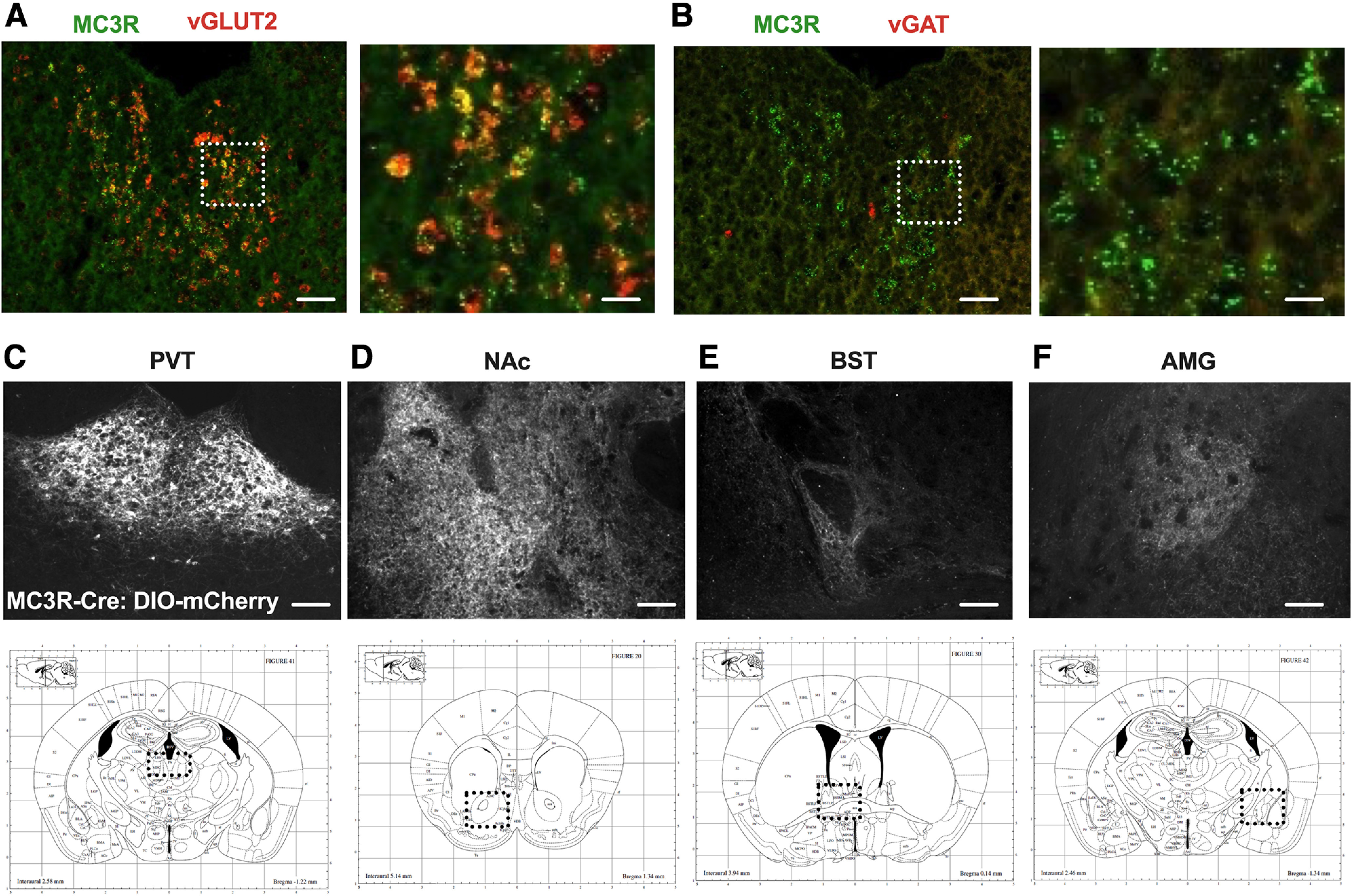

PVT MC3R neurons are glutamatergic and innervate subcortical anxiety circuits

To confirm that MC3R mRNA is expressed within the PVT, and to identify the neurochemical identity of PVT MC3R neurons, we next performed dual color RNAscope fluorescent in situ hybridization to localize MC3R expression in PVT. Consistent with immunofluorescent experiments (Fig. 1), MC3R mRNA was observed throughout the anterior–posterior axis of PVT (Fig. 2A,B). Previous work indicates that most PVT cells are glutamatergic (Curtis et al., 2021), although this has not been confirmed for the MC3R-containing cells in PVT. Confirming the presumed glutamatergic nature of PVT MC3R neurons, we detected a high degree of colocalization of MC3R expression with the glutamatergic marker vGLUT2 (Fig. 2A) and did not colocalize MC3R with the GABAergic marker vGAT (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

PVT MC3R neurons are glutamatergic and project to NAc, BST, and AMG. A, Representative images of MC3R (green) and vGLUT2 (red) mRNA using RNA in situ hybridization in PVT. B, Representative images of MC3R (green) and vGAT (red) mRNA using RNA in situ hybridization in PVT. C, Viral expression of Cre-dependent virus expressing mCherry in PVT MC3R neurons. D–F, Representative images showing projections from PVT MC3R neurons to downstream regions including NAc (D), BST (E), and AMG (F). Scale bars: A, B (left), 100 um, (right) 10 um; C–F, 100 um. PVT images in A and B taken from mid-/posterior PVT (bregma, −1.2). Bottom row indicates a schematic of the neuroanatomical location shown in C–F. NAc (nucleus accumbens), BST (bed nucleus of the stria terminalis), AMG (amygdala).

We next used neuroanatomical tracing approaches to map the projections of PVT MC3R cells. Viral vectors expressing a Cre-recombinase-dependent virus containing the mCherry fluorescent protein were targeted to the PVT in MC3R-Cre mice (Fig. 2C). Projections of PVT MC3R neurons were subsequently identified by immunofluorescence. Consistent with prior studies (Li et al., 2021), we identified MC3R PVT projections in the nucleus accumbens, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and amygdala (Fig. 2D–F). Therefore, PVT MC3R neurons are anatomically positioned to regulate motivation and anxiety-related behavior via projections to subcortical regions critically involved in motivation, anxiety-related behavior, and reward (Fig. 2C–F).

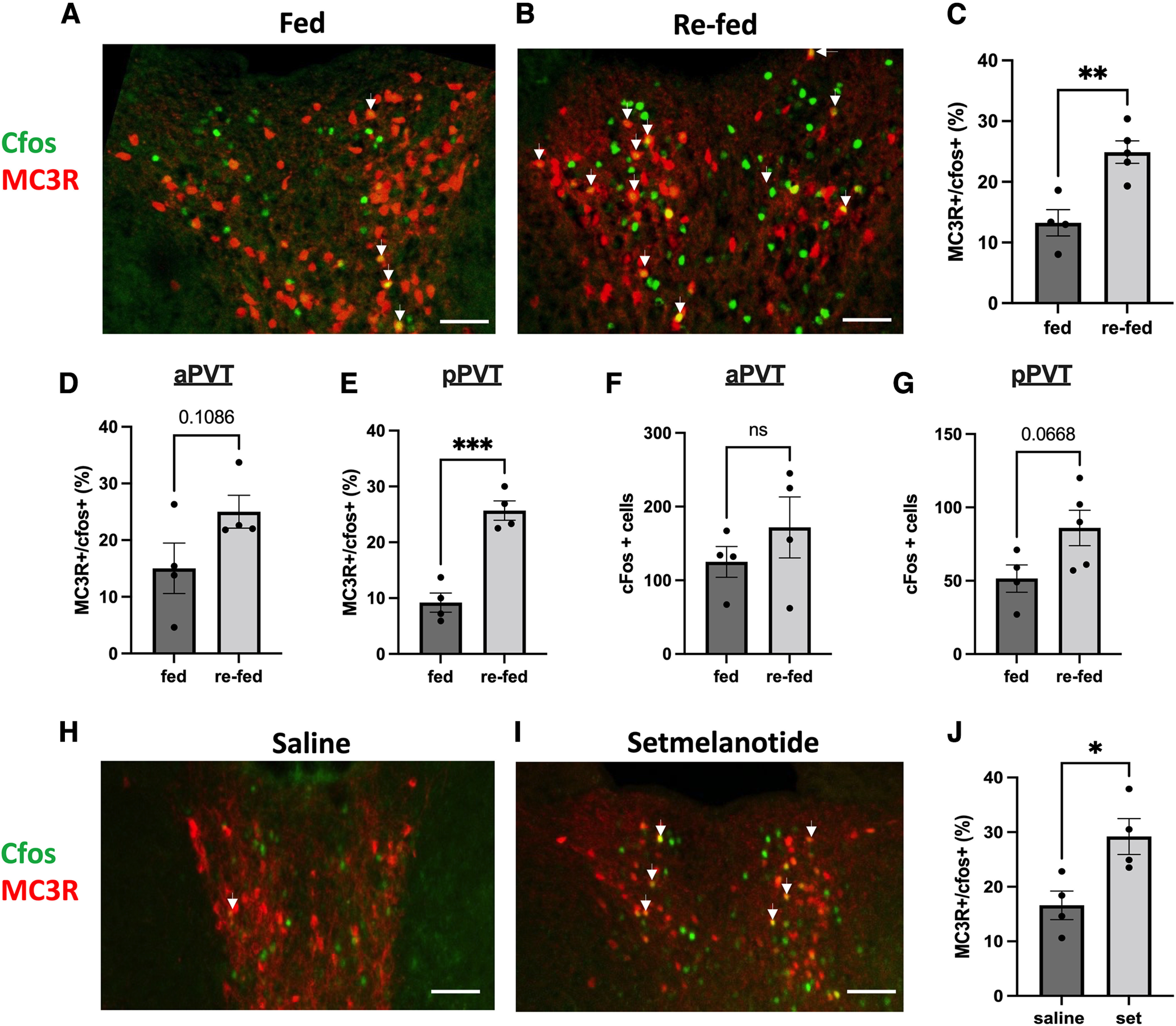

PVT MC3R neurons are activated by satiating stimuli

Prior neuroanatomical data (Fig. 1I,J) suggest that PVT MC3R neurons may be sensitive to energy-state-related information, downstream of hypothalamic AgRP and POMC neurons. Therefore, to determine whether PVT MC3R neurons are sensitive to the energy state of the animal we next performed immunohistochemical analysis for c-fos protein in MC3R-Cre x tdtomato transgenic mice. Importantly, prior studies used dual RNA in situ hybridization for MC3R and mCherry to establish that this genetic targeting strategy labels bona fide MC3R-containing cells (Bedenbaugh et al., 2022). Thus, this approach allows for a simple (albeit indirect) strategy to map neuronal activation of MC3R-containing cells in vivo. Consistent with a role in sensing energy state, we observed increased c-fos protein colocalization in PVT MC3R neurons following refeeding after a fast (Fig. 3A–C). This increased colocalization was more prominent in the posterior portions of the PVT than anterior PVT, although a trend toward increased c-fos colocalization was also observed in the anterior PVT (Fig. 3D,E). In contrast, no significant difference in total c-fos protein expression was observed between fed ad libitum and refed mice in both the anterior and posterior PVT (Fig. 3F,G), although higher baseline c-fos protein levels were observed in more anterior portions of PVT.

Figure 3.

PVT MC3R neurons are activated by refeeding and melanocortin agonist treatment. A, B, Colocalization of c-fos protein in PVT MC3R neurons (MC3R-Cre x tdtomato transgenic mice) in the fed ad libitum state (A) or following 1 h of refeeding after an 18 h fast (B). C, Quantification of the percentage of total PVT MC3R cells colabeled with the c-fos protein in the fed (n = 4 mice) and refed (n = 5 mice) state. Significantly more PVT MC3R cells colocalized for c-fos in the refed versus the fed state (Student's unpaired t test, t(7) = 4.12, p = 0.004). D, E, Percentage of PVT MC3R cells containing c-fos in the anterior PVT (D; t(6) = 1.884, p = 0.108) and posterior PVT (E; t(6) = 6.740, p = 0.0005) in ad libitum fed mice and mice refed for 1 h following fasting. F, Total number of c-fos-positive cells in the anterior portions of PVT (bregma −0.3 to −1.0) in mice fed ad libitum and mice refed for 1 h following fasting (t(6) = 1.009, p = 0.35). G, Total number of c-fos-positive cells in the posterior portions of PVT (bregma −1.1 to −2.0) in mice fed ad libitum and mice refed for 1 h following fasting (t(7) = 2.17, p = 0.067). H, I, Representative images showing the colocalization of c-fos in PVT MC3R neurons following intraperitoneal injections of saline or setmelanotide. J, Quantification of the number of MC3R cells colabeled with c-fos protein in PVT following injections of saline (n = 4) or the melanocortin agonist setmelantoide (n = 4 mice, 5 mg/kg, i.p.). Significantly more MC3R cells were colabeled with c-fos protein following setmleanotide injections relative to control saline injections (Student's unpaired t test, t(6) = 3.01, p = 0.02). Arrows in A, B, H, and I indicate colabeled cells. All data analyzed with unpaired Student's t test). ns, Not significant; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Individual data points in C–G and J indicate individual mice. Scale bars: 100 um.

As more PVT MC3R neurons coexpressed c-fos protein following refeeding (relative to fed ad libitum conditions, Fig. 3A–C), we next tested whether PVT MC3R neurons are responsive to pharmacologically induced satiety by injecting the melanocortin receptor agonist setmelanotide (1 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline in MC3R-Cre x tdtomato mice (Fig. 3H–J). Administration of setmelanotide increased the percentage of PVT MC3R cells coexpressing c-fos protein, suggesting that PVT MC3R neurons are more active following both physiological and pharmacological-induced satiety (Fig. 3H–J). However, future work is required to more fully map how changes in energy state affect the electrophysiological properties of PVT MC3R neurons.

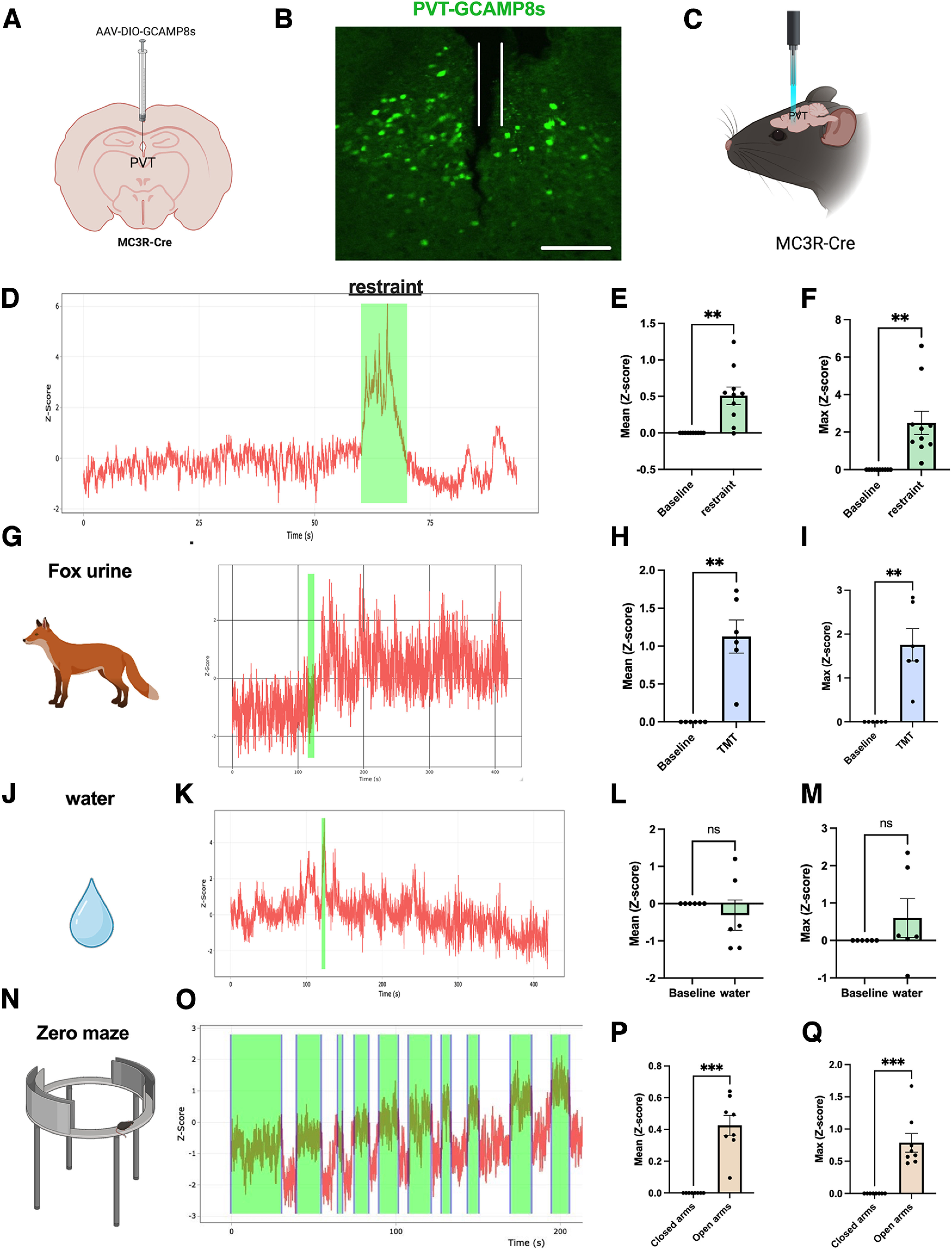

PVT MC3R neurons are activated by aversive and anxiogenic stimuli

As PVT MC3R neurons project to critical neural circuitry controlling aversion and anxiety-related behavior (Fig. 2C–F), we hypothesized that PVT MC3R neurons may encode aversive and anxiogenic related information. To determine how PVT MC3R neuronal activity changes in awake-behaving mice during stressful stimuli, we used in vivo fiber photometry to record changes in calcium in PVT MC3R neurons (Fig. 4A–C). AAV viral injections of the Cre-recombinase-dependent genetically encoded calcium indicator GCAMP8m were targeted to the PVT in MC3R-Cre mice (Fig. 4A,B). In the same surgical procedure, a fiber optic cannula was inserted directly into PVT to detect changes in fluorescence, which provides a readout of calcium levels in the cell, and an indirect readout of neuronal activity (Fig. 4B,C; Gunaydin et al., 2014). MC3R neurons were robustly activated following restraint stress, suggesting that these cells are recruited during aversive stimuli (Fig. 4D–F). This activation was time locked to physical restraint, increasing during physical restraint, and decreasing to baseline levels following the cessation of restraint. We next tested whether PVT MC3R neurons are also sensitive to other forms of stress/aversion, such as the aversive predator odor TMT (Fig. 4G). PVT MC3R neurons were robustly activated following exposure to TMT (Fig. 4H,I). In contrast to physical restraint (Fig. 4D–F), this neuronal activation persisted for the entire period of TMT exposure, likely reflecting the irreversibility of aversive olfactory exposure (Fig. 4G). Importantly, no change in neuronal activity was observed when a Kimwipe containing water was presented in the home cage of the mouse in the same manner as TMT (Fig. 4J–M).

Figure 4.

PVT MC3R neurons are activated by anxiogenic and aversive stimuli. A, Viral injection strategy for expressing the genetically encoded calcium indicator GCAMP8 in PVT MC3R neurons. B, Representative image of GCAMP8s expression in PVT MC3R neurons with a fiber optic cannula inserted into the PVT. Cannula trace marked in white. C, Schematic depicting in vivo fiber photometry calcium imaging of PVT MC3R neuronal activity in awake, behaving mice. D, Schematic of approach used for restraint stress experiments and representative trace of calcium activity (Z-scored) during restraint stress. Restraint period highlighted in green. E, F, Mean change in calcium activity during restraint versus before restraint (E; t(9) = 4.3, p = 0.002, n = 10 mice), and maximum calcium activity (F; t(9) = 4.03, p = 0.003, n = 10 mice) during restraint versus before restraint. G, Schematic of approach used for TMT imaging experiments and representative trace of calcium activity in PVT MC3R neurons on introduction of the predator odor TMT. H, I, Mean change in calcium activity (H; t(5) = 5.13, p = 0.004, n = 6 mice) and maximum calcium activity (I; t(5) = 4.77, p = 0.005, n = 6 mice) before and after TMT exposure. J, K, Representative trace of calcium activity following the presentation of water, presented in an identical manner as TMT exposure experiments. L, M, Mean change in calcium activity (L; t(5) = 0.76, p = 0.48, n = 6 mice) and maximum calcium activity (M; t(5) = 1.16, p = 0.30, n = 6 mice) after water exposure (relative to before water exposure). N, O, Representative trace of calcium activity during elevated zero maze test. Time in the open arms is highlighted in green. P, Q, Mean change in calcium activity in the open arms versus closed arms (P; t(7) = 6.82, p = 0.0002, n = 8 mice) and maximum calcium activity in the open arms versus the closed arms (Q; t(7) = 5.46, p = 0.0009, n = 8 mice). Data analyzed by paired Student's t test; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). ns, Not significant). Data points represent individual mice. Introduction of the stimulus is highlighted in green for G and J. Scale bar, B, 200 um.

Because AgRP and POMC neurons also regulate anxiety-related behavior (Dietrich et al., 2015; Li et al., 2019; Qu et al., 2020; Fang et al., 2021), and PVT circuitry has been previously linked to anxiety-related behaviors (Choi and McNally, 2017; Choi et al., 2019; Kirouac, 2021; McNally, 2021; Penzo and Gao, 2021), we next tested whether PVT MC3R neurons are sensitive to anxiogenic environments. PVT MC3R neurons were robustly activated when animals entered the anxiogenic open arms of the EZM (Fig. 4N–Q). Neuronal activity was time locked to exposure to the anxiogenic open arms, rising as mice entered the open arms and falling as they re-entered the closed arms (Fig. 4O). This neuronal response repeated during each open arm entry/exit (Fig. 4O), suggesting an important role for these neurons in signaling anxiety-provoking stimuli.

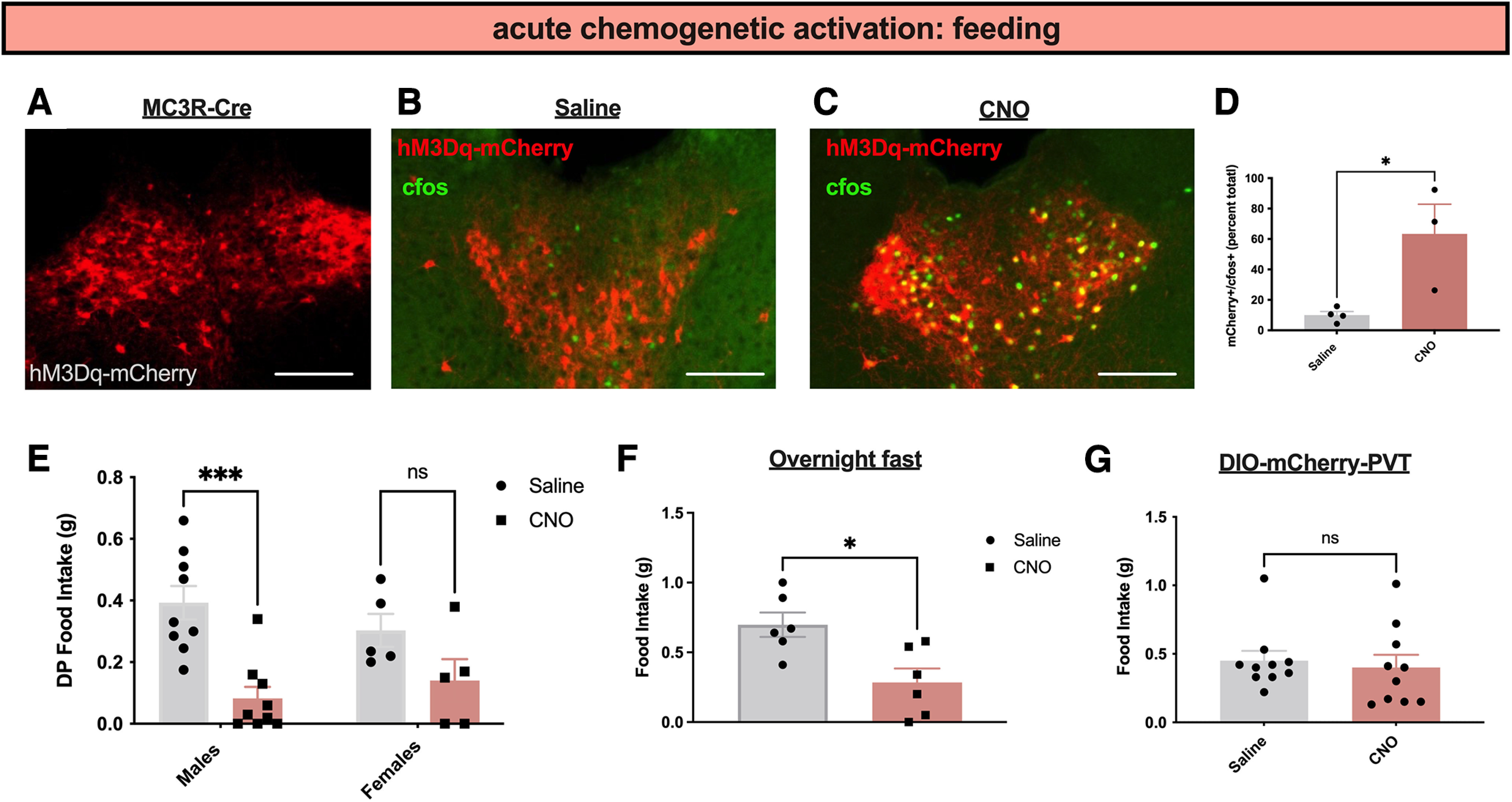

Activation of PVT MC3R neurons reduces feeding and increases anxiety-related behavior

As in vivo imaging data demonstrate that PVT MC3R neurons are more active during anxiety-provoking and aversive stimuli (Fig. 4), we next used chemogenetic approaches to test the causal contribution of PVT MC3R neurons to feeding and anxiety-related behavior. To selectively activate PVT MC3R neurons, we targeted the PVT with viral injections of an AAV viral construct expressing a Cre-recombinase-dependent version of the activating DREADD hM3Dq-mCherry in MC3R-Cre mice (Fig. 5A). Immunohistochemistry analysis confirmed expression of hM3Dq-mCherry specifically in the PVT MC3R cells (Fig. 5A) and increased neuronal activity of these cells following administration of the DREADD agonist CNO (0.3 mg/kg, i.p.; Fig. 5B–D). To test the functional effects of activating PVT MC3R neurons we performed a series of feeding and anxiety-related behavioral assays in these mice. Previously, we demonstrated that chemogenetic activation of PVT MC3R neurons reduces feeding in mice fed ad libitum (Ghamari-Langroudi et al., 2018). Here, we confirmed that activation of PVT MC3R neurons reduces feeding in both male and female mice (Fig. 5E) and reduces feeding following an overnight fast (Fig. 5F). No difference in food intake was detected in control mCherry-expressing mice following intraperitoneal CNO injections (fed ad libitum dark period food intake; Fig. 5G).

Figure 5.

Activation of PVT MC3R neurons reduces feeding. A, Representative image showing the DREADD activator hM3Dq-mCherry expression in PVT MC3R neurons. B, C, Images showing colabeling of c-fos immunohistochemistry with hM3Dq-mCherry virus in saline-injected mice (B) or mice injected with CNO (C). D, Quantification of the percentage of MC3R-mCherry cells expressing c-fos in PVT following intraperitoneal injections of saline or CNO (n = 4 mice for saline group and n = 3 mice for CNO group; unpaired Student's t test, t(4) = 2.95, p = 0.04). E, Dark period food intake (2 h food intake) of male (n = 9) and female (n = 5) hM3Dq mice that were injected with saline or CNO (0.3 mg/kg, i.p.). There was no interaction between sex and food intake (2-way ANOVA, F(1,24) = 1.787, p value = 0.1939) but a significant main effect of chemogenetic activation (2-way ANOVA, F(1,24) = 18.40, p value = 0.0003) on food intake. F, Two-hour food intake following intraperitoneal injection of CNO (0.3 mg/kg; n = 6 mice) or saline (n = 6 mice) in mice targeted with the DREADD activator hM3Dq in PVT MC3R neurons (Student's unpaired t test, t(10) = 3.12, p = 0.01) following an overnight fast. G, Two-hour food intake in MC3R-cre mice containing DIO-mCherry in PVT that were injected with saline or CNO (n = 10 male mice). No difference was detected between saline- and CNO-injected mice (t(9) = 0.38, p = 0.72); *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. Individual data points indicate individual mice. Scale bars: 200 um.

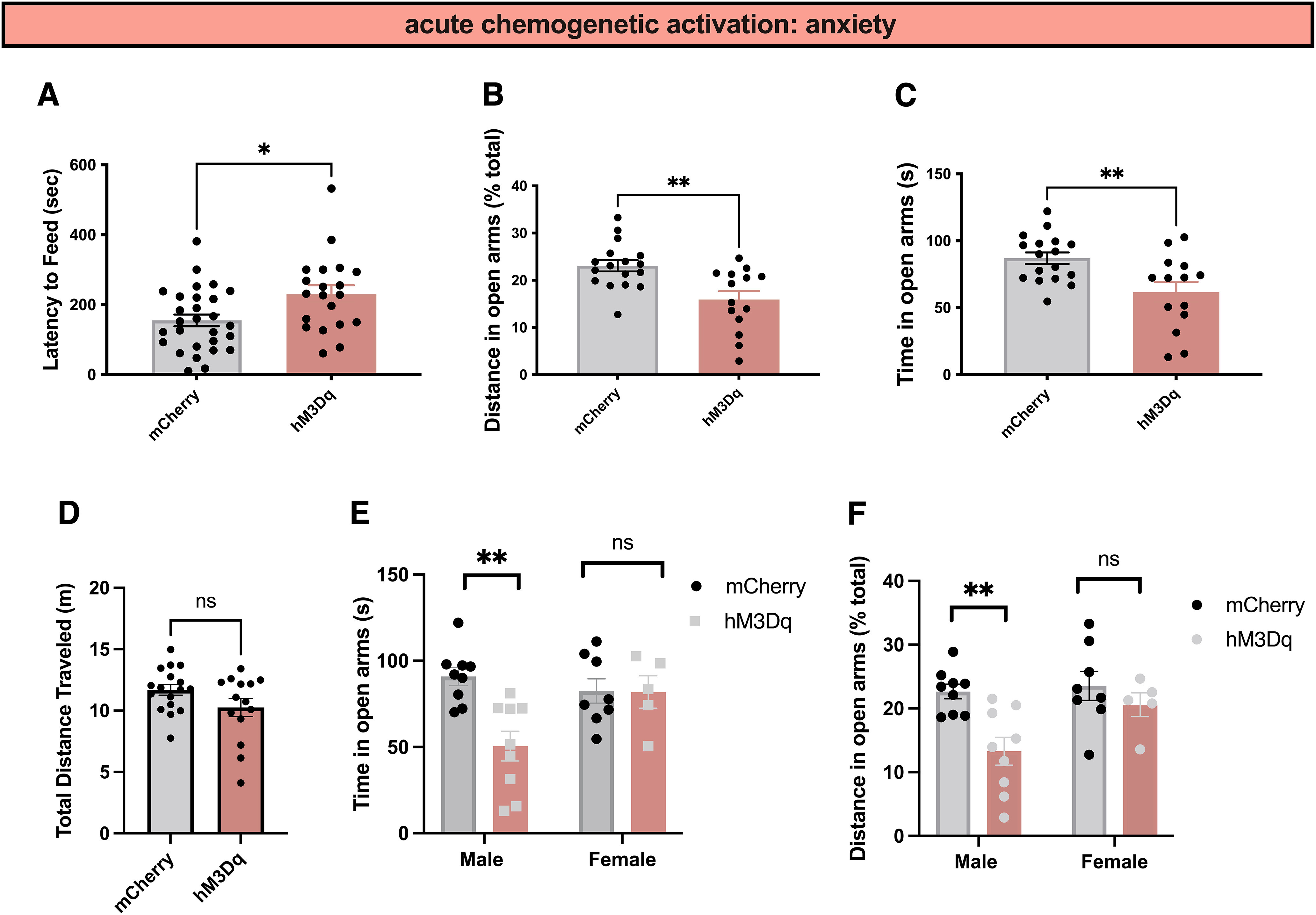

Next, we tested whether PVT MC3R neurons regulate anxiety-related behavior by performing NSF and EZM tests of anxiety-related behavior in new cohorts of mice (Fig. 6). Activation of PVT MC3R neurons increased the latency to feed in the NSF test (Fig. 6A). Consistently, stimulation of PVT MC3R neurons decreased both time in the open arms and distance traveled in the open arms in the elevated zero maze (Fig. 6B,C), without affecting the total distance traveled (Fig. 6D). This effect was more significant in male mice than female animals (Fig. 6E,F). Together, these findings indicate that activation of PVT MC3R neurons is sufficient to reduce feeding and increase anxiety-related behavior in mice.

Figure 6.

Activation of PVT MC3R neurons increases anxiety-related behavior. A, Latency to feed during novelty-suppressed feeding tests in control mCherry (n = 28 mice) and hM3D mice (n = 20 mice) injected with CNO (0.3 mg/kg; Mann–Whitney test, two-tailed p value, 0.0115, Mann–Whitney U = 160); this figure includes mCherry and hM3D mice from cohorts 1 and 2 combined. B, C, Distance traveled in the open arms (B; Mann–Whitney test, two-tailed p value = 0.0040, Mann–Whitney U = 48) and time in the open arms (C; Student's unpaired t test, t(29) = 3.03, p = 0.005) during the elevated zero maze test. Activation of PVT MC3R neurons decreased both distance traveled in the open arms (B) and time in the open arms (C) relative to control mCherry-injected mice (n = 17 mice in mCherry group and n = 14 mice in hM3Dq group). D, Total distance traveled (in meters) for mCherry (n = 17 mice) and hM3Dq (n = 14 mice) mice. No statistically significant difference was observed in the total distance traveled between mCherry and hM3Dq mice following CNO administration (unpaired Students t test, t(29) = 1.75, p = 0.09). E, Time spent in the open arms during the elevated zero maze in mCherry male (n = 9 mice), mCherry female (n = 8), hM3Dq male (n = 9), and hM3Dq female (n = 5) mice. There is an interaction between sex and time in the open arms, with male mice, and not females, exhibiting a significant reduction in time in the open arms following activation of PVT MC3R neurons (2-way ANOVA, F(1,27) = 6.566, p value = 0.0163). F, Percentage of distance traveled in the open arms in mCherry male (n = 9 mice), mCherry female (n = 8), hM3Dq male (n = 9), and hM3Dq female (n = 5) mice (no significant interaction between sex and distance in open arms, 2-way ANOVA, F(1,27) = 2.537, p value = 0.1228; main effect of hM3Dq activation, F(1,27) = 9.4, p value = 0.0049). Activation of PVT MC3R neurons reduced distance traveled in the open arms in male, but not female, mice; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Individual data points indicate individual mice.

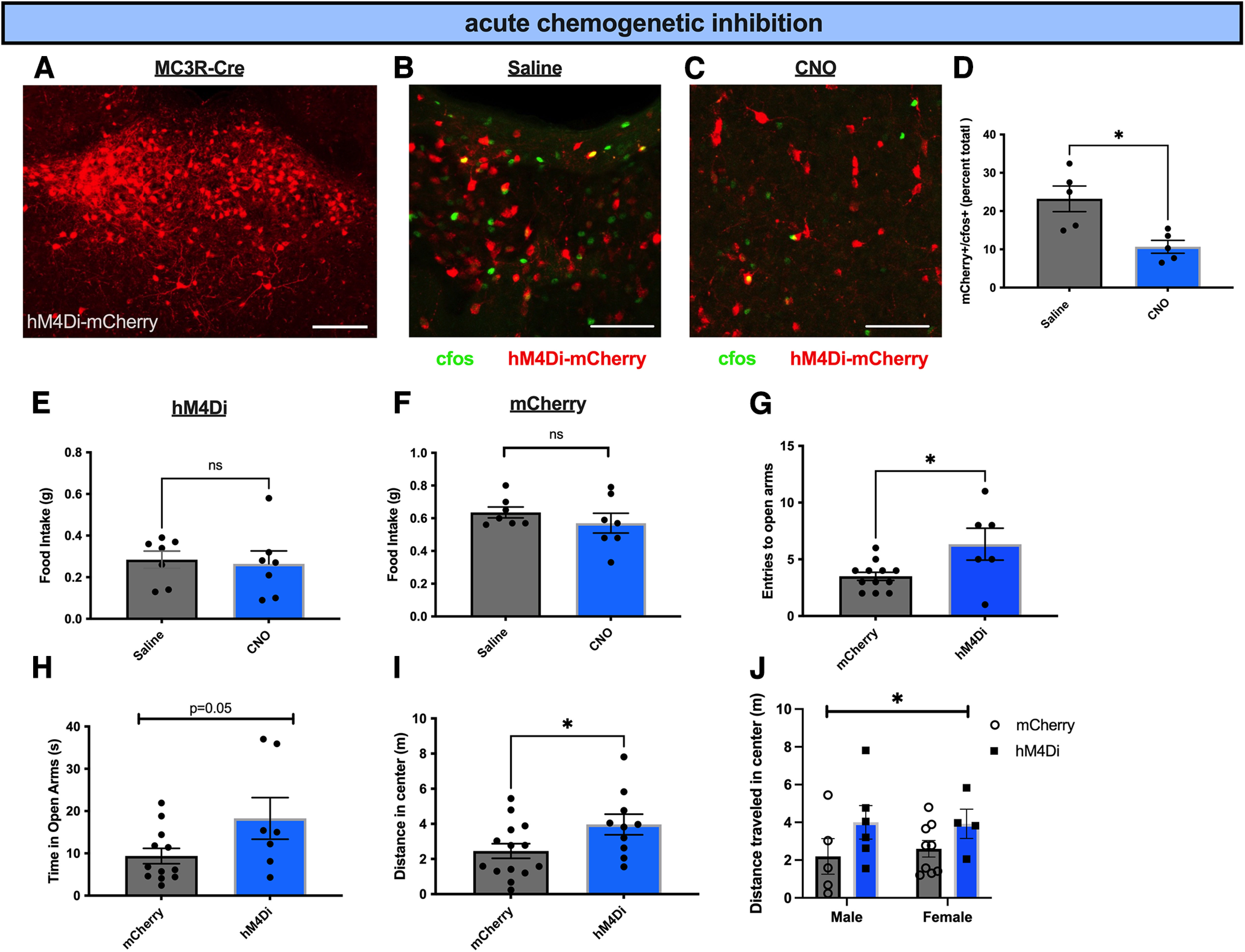

Inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons reduces anxiety-related behavior

To test whether PVT MC3R neurons are required for normal feeding and anxiety-related behaviors, we expressed the chemogenetic inhibitor DREADD hM4Di in PVT MC3R neurons (Fig. 7A). To validate that hM4Di inhibited the activity of PVT MC3R neurons, we performed immunohistochemistry for the immediate early gene c-fos following administration of control saline or CNO (0.3 mg/kg, i.p.) to mice expressing hM4Di in PVT MC3R neurons (Fig. 7B–D). Administration of CNO reduced the expression of c-fos specifically in PVT MC3R neurons (Fig. 7B–D), confirming effective DREADD-mediated inhibition of these neurons.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons decreases anxiety-related behavior. A, Representative image showing the DREADD inhibitor hM4Di-mCherry expression in PVT MC3R neurons. B, C, Representative image showing colabeling of c-fos immunohistochemistry with hm4di-mCherry viral expression in saline-injected mice (B) or CNO-injected mice (C). D, Quantification of the percentage of PVT MC3R neurons activated by c-fos in hM4Di-mCherry-expressing mice following injections of saline or CNO (n = 5 mice for both saline- and CNO-injected groups, Student's unpaired t test, t(8) = 3.34, p = 0.01). E, Two-hour food intake following intraperitoneal injection of CNO (0.3 mg/kg) or saline in mice targeted with the DREADD inhibitor hM4Di in PVT MC3R neurons (n = 7 mice; Student's unpaired t test, t(6) = 0.02, p = 0.78). F, Two-hour dark period food intake in control mCherry-expressing mice following injections of saline or CNO (0.3 mg/kg, i.p.). No difference in food intake was detected between saline- and CNO-injected mice (n = 7 mice, Student's paired t test, t(6) = 1.14, p = 0.30). G, H, Number of entries to the open arms (G) and time in the open arms (H) during the elevated zero maze. Inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons in hM4Di-injected mice increased the number of entries compared with mCherry mice (n = 12 mice in mCherry group and n = 7 mice in hM4Di group, Students unpaired t test, t(16) = 2.59, p = 0.019) and trended toward increasing the time spent in the open arms (n = 12 mice in mCherry group and n = 7 mice in hM4Di group, Student's unpaired t test, t(17) = 2.02, p = 0.059). I, Distance traveled in the center of the open field arena in mCherry- or hM4Di targeted mice during open field tests. Inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons increased the distance traveled in the center of the open field arena compared with mCherry control injected mice (n = 10 mice in hM4Di group and n = 14 mice in mCherry group, Student's unpaired t test, t(22) = 2.16, p = 0.04). J, Total distance traveled in the center (in meters) of the OFT arena between mCherry male (n = 5), mCherry female (n = 9), hM4Di male (n = 6), and hM4Di female (n = 4) mice. There is no interaction between sex and distance traveled in the center (2-way ANOVA, F(1,20) = 6.566, p value = 0.7503) but a significant main effect of hM4Di-mediated inhibition on distance traveled in the center (2-way ANOVA, F(1,20) = 4.307, p value = 0.05; *p < 0.05. ns, Not significant. Individual data points represent individual mice. Scale bar: A, 100 um; B, C, 250 um.

Following validation of DREADD-mediated inhibition, we performed feeding and anxiety-related behavioral assays to characterize the effects of inhibiting PVT MC3R neurons. Acute chemogenetic inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons did not change feeding behavior on a regular chow diet in ad libitum fed conditions (Fig. 7E). Further, CNO injections did not alter food intake in control mCherry-injected mice (fed ad libitum; Fig. 7F). Thus, acute inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons does not regulate feeding behavior on a regular chow diet. To determine whether PVT MC3R neurons are required for regulating anxiety-related behavior we performed elevated zero maze tests following chemogenetic inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons (Fig. 7G,H). Inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons increased entries to the open arms and trended toward increasing time spent in the open arms (Fig. 7G,H). In a second cohort of mice, to confirm the effects on anxiety-related behavior, we performed open field tests of anxiety-related behavior (Fig. 7I). Consistent with prior elevated zero maze results, inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons increased the distance traveled in the center of the open field (Fig. 7I), with similar results obtained in both male and female mice (Fig. 7).

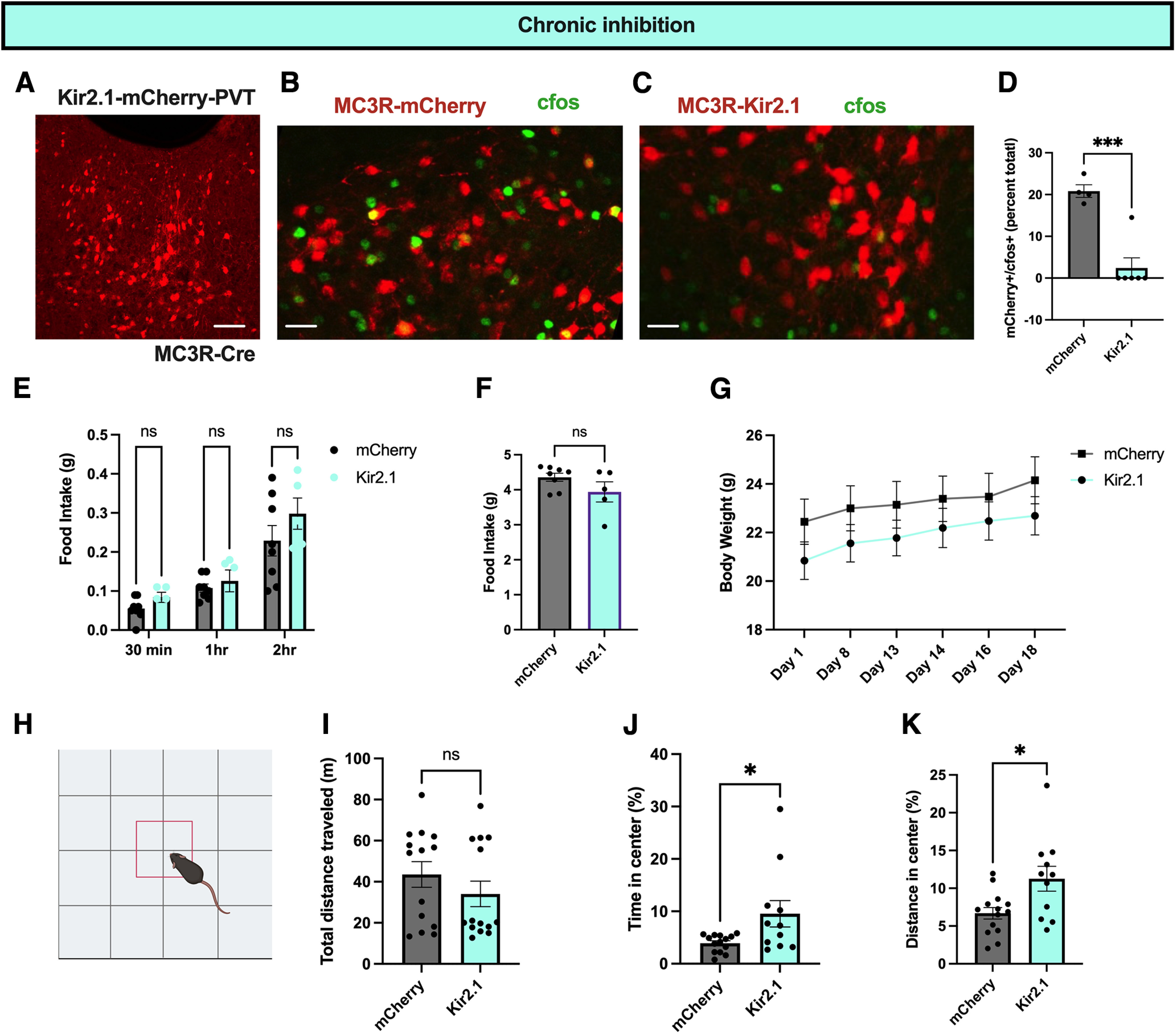

Given these findings, we next tested the effects of chronic PVT MC3R neuronal inhibition on feeding and anxiety-related behavior by targeting AAV viral vectors expressing the ion channel Kir2.1 specifically to PVT MC3R neurons (Fig. 8A; Zhu et al., 2020). To validate the effectiveness of Kir2.1 in inhibiting PVT MC3R neurons, we measured c-fos protein levels in mice expressing either control mCherry-expressing virus or Kir2.1 in PVT MC3R neurons (Fig. 8B–D). We observed several MC3R-mCherry; c-fos colocalized cells in the control group but observed few PVT MC3R neurons colocalized with c-fos in the Kir2.1 group (Fig. 8B–D), demonstrating successful neuronal inhibition with Kir2.1. Although acute inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons did not alter feeding (Fig. 7E), it is possible that longer-term inhibition of these neurons may produce changes in energy homeostasis. To test this hypothesis, we measured the food intake and body weight change in mice with Kir2.1 or control mCherry virus in PVT MC3R neurons in the weeks following viral injection. Chronic inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons did not alter acute or daily food intake (Fig. 8E,F). Further, control and Kir2.1-expressing mice demonstrated similar changes in body weight in the weeks following viral injection (Fig. 8G).

Figure 8.

Chronic inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons reduces anxiety-related behavior. A, Representative image of the viral expression of Kir2.1-mCherry in PVT MC3R neurons. B, C, Image of colabeling of c-fos immunohistochemistry with mCherry viral expression in control mCherry-expressing mice (B), or mice with Kir2.1-mCherry in PVT MC3R neurons. D, Quantification of the percentage of PVT MC3R neurons containing c-fos in mCherry (n = 4) and Kir2.1-mCherry-expressing mice (n = 4 mice in mCherry group and n = 6 mice in Kir2.1 group, Student's unpaired t test, t(8) = 5.667, p value = 0.0005). E, Food intake of mCherry and Kir2.1 mice during the dark period in ad libitum fed conditions. No difference in food intake was detected between control mCherry- and Kir2.1-expressing mice (n = 8 mice for mCherry condition and n = 5 mice for Kir2.1 condition, 2-way ANOVA, main effect of viral injection condition, F(1,33) = 3.12, p = 0.09). F. Twenty-four-hour food intake of mCherry and Kir2.1 targeted mice during ad libitum access to regular chow (n = 8 mice in mCherry group and n = 5 mice in Kir 2.1 group, Student's unpaired t test, t(11) = 1.57, p = 0.145). G, Body weight curve of mCherry- and Kir2.1-injected mice over the course of the experiments. H, Image of open field test apparatus used for open field tests. I, Total distance traveled during the open field tests for both mCherry and Kir2.1 targeted mice (n = 14 mice in mCherry group and 11 mice in Kir2.1 groups, Mann–Whitney test, two-tailed p value = 0.8508, Mann–Whitney U = 73). J, Percentage of time in the center of the open field test in mCherry-injected mice and Kir2.1-injected mice. Chronic inhibition significantly increased the percentage of time the mice spent in the center (n = 14 mice in mCherry group and n = 11 mice in Kir2.1 group; Mann–Whitney test, p value = 0.038, Mann–Whitney U = 39). K, Percentage of distance traveled in the center of the open field test in mCherry-injected mice and Kir2.1-injected mice. Chronic inhibition significantly increased the percentage of distance traveled in the center of the open field test (n = 14 mice in mCherry group and n = 11 mice in Kir2.1 group; Student's unpaired t test, t(23) = 2.694, p = 0.01); *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. ns, Not significant. Individual data points indicate individual mice. Scale bars: A, 100 um; B and C, 50 um.

To test whether chronic inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons regulates anxiety-related behavior, we performed open field tests 1 month following Kir2.1 or control mCherry viral injections. Mice with Kir2.1 expression in PVT MC3R neurons spent more time in the center of the open field and traveled more distance in the center of the open field, without any significant change in total distance traveled (Fig. 8H–K). Thus, both acute and chronic inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons reduces anxiety-related behavior in mice without producing significant effects on feeding or body weight.

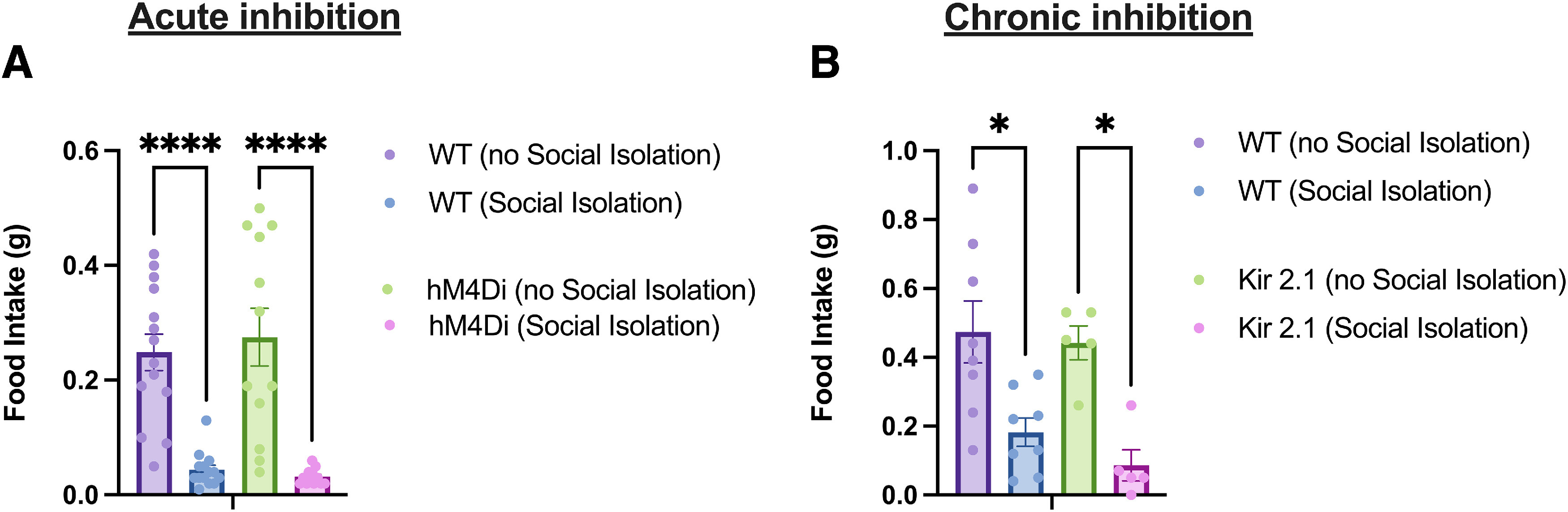

As stimulation of PVT MC3R neurons reduces feeding, and PVT MC3R neurons are activated by stressful stimuli, we tested whether these neurons are required for stress-induced anorexia. To measure the anorexigenic response to stress, we used social-isolation-induced anorexia assays, as described in our previous study (Sweeney et al., 2021b). Social isolation significantly reduced food intake in control mice and to a similar extent in mice with acute or chronic inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons (Fig. 9). Therefore, PVT MC3R neurons exert a specific function in controlling anxiety-related behavior and are not required for the acute anorexigenic responses to stress.

Figure 9.

Inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons does not affect acute anorexic response to social isolation stress. A, One-hour food intake in WT or hM4Di targeted mice on the day of social isolation and on the day following social isolation. Acute social isolation reduced food intake in both WT and hM4Di mice (n = 12 mice in hM4Di group, n = 14 mice in WT group; 2-way ANOVA, no significant interaction between social isolation and hM4Di-mediated inhibition, F(1,48) = 0.42, p = 0.52). B, One-hour food intake in WT and Kir2.1 targeted mice on the day of social isolation and the day following social isolation. Social isolation reduced food intake in both groups of mice, with no significant interaction between viral injection condition and social isolation (n = 8 mice in WT group and n = 5 mice in Kir2.1 group; 2-way ANOVA, F(1,22) = 0.22, p = 0.64); *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001. Data points indicate individual mice.

MC3R in PVT regulates anxiety-related behavior

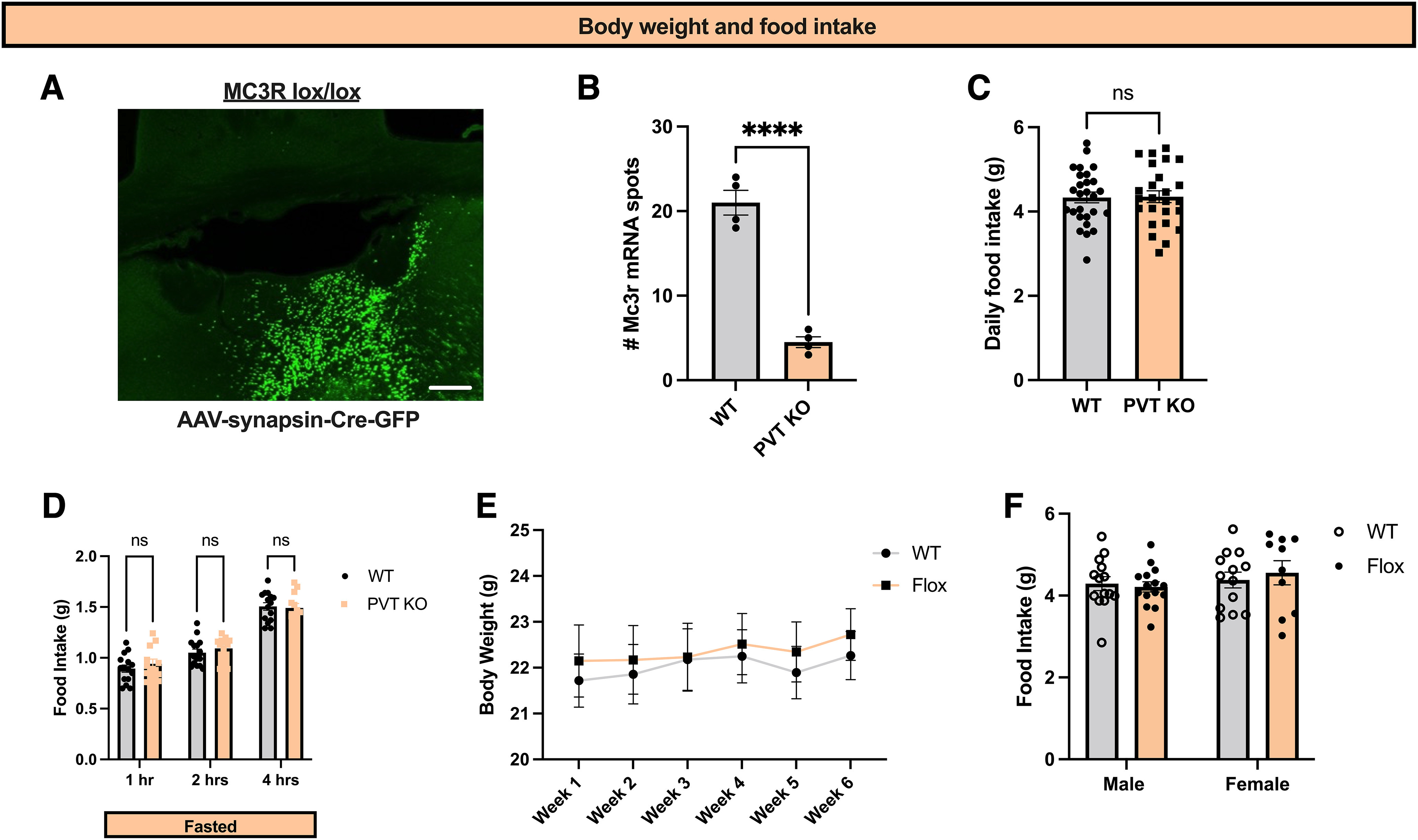

Chemogenetic assays demonstrate that PVT MC3R neurons regulate anxiety-related behavior. However, these findings do not provide information on the role of MC3R signaling in PVT neurons. Therefore, to specifically determine the role of MC3R signaling in PVT we used a novel MC3R floxed mouse line to specifically delete MC3R in the PVT in adult mice. AAV viral injections of virus expressing Cre recombinase fused to green fluorescent protein were targeted to the PVT in MC3R floxed mice or WT control mice (Fig. 10A). RNAscope in situ hybridization confirmed successful deletion of MC3R in the PVT of AAV-Cre targeted mice (Fig. 10B). Consistent with chemogenetic inhibition experiments, deletion of MC3R in PVT did not affect food intake of regular chow diet in basal conditions or following an overnight fast (Fig. 10C,D). Further, PVT MC3R KO and control mice demonstrated similar changes in body weight in the weeks following viral-mediated deletion (Fig. 10E), with similar results obtained in both male and female mice (Fig. 10F).

Figure 10.

MC3R in PVT does not regulate feeding behavior on a standard chow diet. A, Representative image showing viral expression of Cre-GFP in the PVT in MC3R lox/lox mice. B, Quantification of MC3R mRNA levels in PVT in WT (n = 4 mice) and flox/flox (n = 4 mice) mice injected with AAV-Cre-GFP into PVT using RNA in situ hybridization. PVT MC3R KO mice showed a significant reduction in MC3R mRNA compared with WT mice (Student's unpaired t test, t(6) = 10.27, p < 0.0001). C, Ad libitum 24 h food intake for WT (n = 27) and flox/flox (n = 25) mice. No statistical difference in 24 h food intake was observed (Student's unpaired t test, t(50) = 0.085, p = 0.93). D, Acute food intake following an overnight fast in WT (n = 15 mice) and flox/flox mice (n = 12 mice). No statistical difference in food intake following an overnight fast was observed (2-way ANOVA, F(2,50) = 0.7980, p value = 0.4559). E, Weekly body weights of WT and flox/flox mice over the course of the experiments. F, Twenty-four-hour food intake in WT male (n = 14), WT female (n = 13), flox/flox male (n = 15), and flox/flox female mice (n = 10). There is no effect of sex in this context (2-way ANOVA of interaction between sex and food intake, F(1,48) = 0.4467, p value = 0.5071); ****p < 0.0001. ns, Not significant. Individual data points indicate individual mice. Scale bar, A, 50 um.

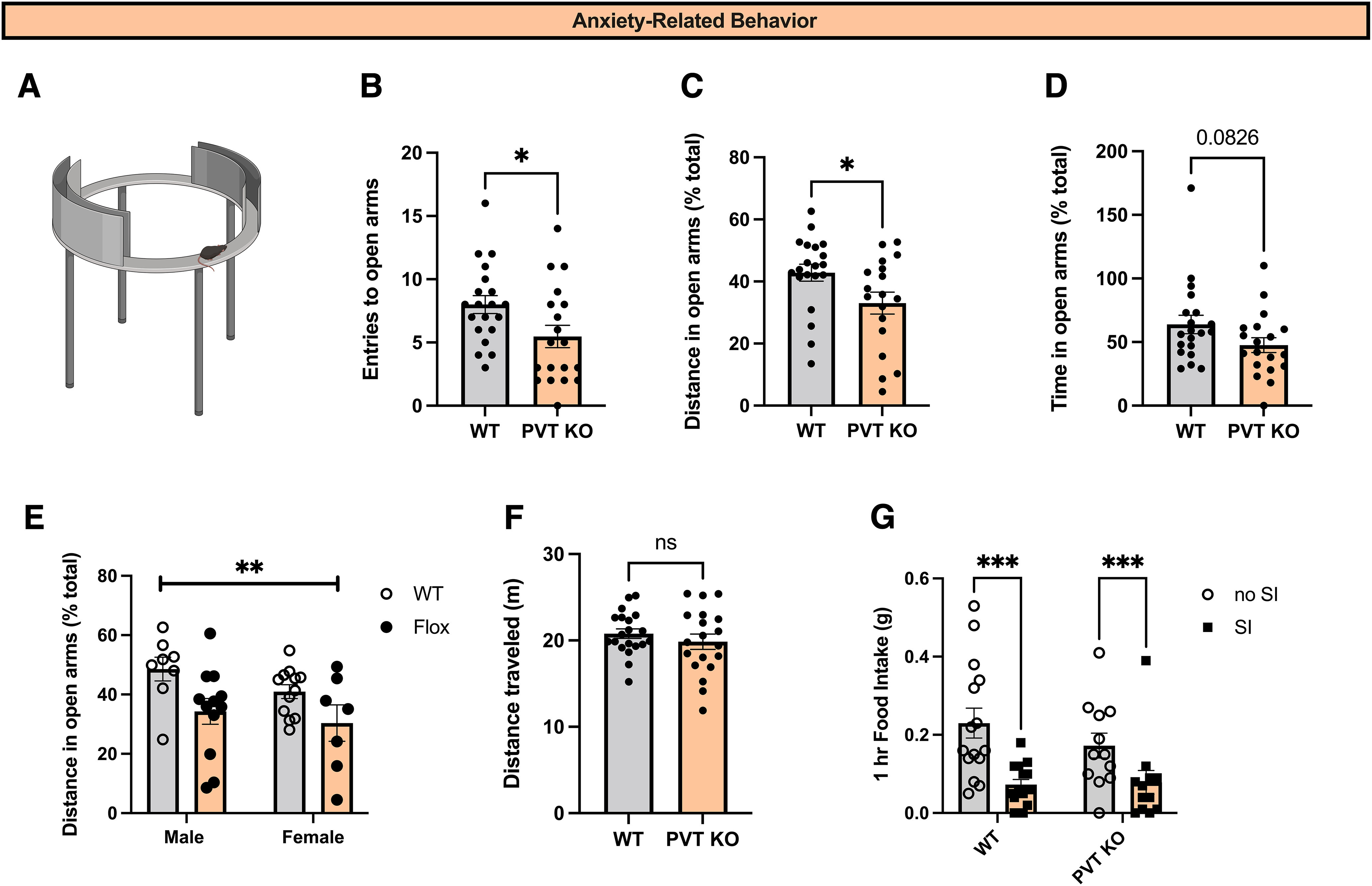

To determine the role of PVT MC3R signaling in anxiety-related behavior, we next performed elevated zero maze tests in mice with PVT-specific deletion of MC3R or control littermates (Fig. 11A). PVT MC3R KO mice entered the open arms less frequently, traveled less distance in the open arms, and trended toward spending less time in the open arms (Fig. 11B–D), with similar results obtained in both male and female mice (Fig. 11E). No difference in locomotor activity was observed between PVT MC3R KO and WT mice, indicating that these changes were not secondary to altered locomotor activity (Fig. 11F). Given that PVT MC3R neurons are activated by stressful stimuli (Fig. 4), and activation of these neurons reduces food intake (Fig. 5), we next tested whether MC3R signaling in PVT regulates the acute anorexic response to stress. Consistent with acute and chronic neuronal inhibition studies (Fig. 9), the deletion of MC3R in PVT did not alter the acute anorexic responses to social isolation stress (Fig. 11G). Together, MC3R signaling in PVT is important for regulating anxiety-like behavior but is not required for the regulation of feeding in basal conditions or the acute anorexic response to social isolation stress.

Figure 11.

MC3R in PVT regulates anxiety-related behavior. A, Image of elevated zero maze apparatus B, Total number of entries to the open arms during the EZM test in WT (n = 20 mice) and flox/flox (n = 19 mice) mice. Deletion of MC3R from PVT significantly reduced the total number of entries to the open arms during the EZM test (Mann–Whitney test, two-tailed p value = 0.0223, Mann–Whitney U = 109.5). C, Distance traveled in the open arms of the EZM in WT (n = 20) and flox/flox (n = 19) mice as a percentage of the total distance traveled. Deletion of MC3R from PVT significantly decreased the percentage of the distance traveled in the open arms of the EZM test (Mann–Whitney test, two-tailed p value = 0.0208, Mann–Whitney U = 108). D, Time spent in the open arms of the EZM in WT (n = 20) and flox/flox (n = 19) mice. Deletion of MC3R from PVT did not significantly reduce the percentage of time spent in the open arms, although a trend was observed (Mann–Whitney test, two-tailed p value = 0.0826, Mann–Whitney U = 128). E, Distance traveled in the open arms of the EZM as a percentage of the total distance traveled in WT male (n = 8), WT female (n = 12), flox/flox male (n = 12), and flox/flox female (n = 7) mice. There is no effect of sex in this context (2-way ANOVA of interaction between sex and percentage of distance in the open arms, F(1,35) = 0.7593, p value = 0.7593) but a main overall effect of MC3R deletion (2-way ANOVA, main effect of genotype, F(1,35) = 8.7, p = 0.005). F, Distance traveled (in meters) during EZM experiment in WT (n = 20) and flox/flox (n = 19) mice. No statistical difference was observed between WT and flox/flox mice in total distance traveled (Student's unpaired t test, t(37) = 0.91, p = 0.37). G, One-hour food intake on the day of social isolation and the day following social isolation. Deletion of MC3R in PVT did not alter the acute anorexic response to social isolation (2-way ANOVA, interaction between genotype and social isolation, F(1,50) = 1.1, p = 0.29); *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. ns, Not significant. Individual data points indicate individual mice.

Discussion

The paraventricular thalamus is ideally positioned to integrate exteroceptive and interoceptive information and regulate behavior in response to changing conditions (Kirouac, 2015; McGinty and Otis, 2020; Penzo and Gao, 2021). PVT is innervated by hypothalamic and hindbrain regions critical for regulation of energy homeostasis. For example, arcuate nucleus AgRP neurons (Wang et al., 2015), lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons (Meffre et al., 2019), and neurons in the ventral medial hypothalamus (Zhang et al., 2020), zona incerta (Zhang and van den Pol, 2017), and the parasubthalamic nucleus (Zhang and van den Pol, 2017) all directly regulate feeding via projections to PVT. Further, the PVT receives inputs from hindbrain neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract (Dumont et al., 2022) and parabrachial nucleus (Zhu et al., 2022) which may communicate meal-derived satiety signals from the gut directly to PVT. Presumably, hypothalamic and hindbrain projections to PVT act to convey physiological state information to PVT neurons, which directly innervate cortical and subcortical structures controlling behavioral approach/avoidance and motivation (Kelley et al., 2005). PVT neurons are also sensitive to external stressors (Kirouac, 2015, 2021; Penzo et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2018; Campus et al., 2019; Barson et al., 2020) and are innervated by cortical, hippocampal, and subcortical regions conveying external danger and contextual information (Li and Kirouac, 2012). This anatomic structure supports a conceptual framework for the PVT in integrating internal and external state information and communicating this information to subcortical and cortical structures to initiate an appropriate behavioral response (Kelley et al., 2005). Consistent with this interpretation, prior studies indicate that PVT circuitry is critical for prioritizing motivated behaviors toward the underlying need state of the animals (Choi and McNally, 2017; Choi et al., 2019; Meffre et al., 2019; Otis et al., 2019; Horio and Liberles, 2021; Penzo and Gao, 2021).

We propose here that PVT cells containing the MC3R represent a subset of PVT neurons with a specialized role in communicating energy state information with subcortical structures controlling approach/avoidance behaviors, as has been demonstrated for other PVT cell types with dedicated roles in sensing changes in glucose homeostasis (Labouèbe et al., 2016; Sofia Beas et al., 2020; Kessler et al., 2021). Such a circuit architecture would facilitate adaptive decision-making and behavioral approaches in the face of changing internal and external conditions (McGinty and Otis, 2020; Penzo and Gao, 2021). The neuroanatomical and behavioral evidence presented here suggests that PVT MC3R neurons likely mediate their effects by relaying energy state information from hypothalamic melanocortin neurons (Fig. 1) to downstream cells in the nucleus accumbens, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, and amygdala (Fig. 2). However, further work is required to map the functional connections between hypothalamic (arcuate nucleus AgRP and POMC neurons) and hindbrain (nucleus of the solitary tract POMC neurons) melanocortin neurons and MC3R neurons in PVT and to determine the specific function of each of the PVT MC3R projection pathways. Additionally, future work should establish the relationship between signals of satiety [i.e., CCK, PYY (peptide tyrosine-tyrosine), GLP1 (glucagon-like peptide-1] and hunger (i.e., ghrelin) and the activity of PVT MC3R neurons.

PVT MC3R neurons bidirectionally control anxiety-related behavior, with neuronal activation increasing anxiety-related behaviors and inhibition decreasing anxiety-related behaviors (Fig. 5–8). Importantly, these effects are physiologically relevant as PVT MC3R neurons are robustly activated by aversive stimuli and exposure to anxiogenic environments (Fig. 4). Further, deletion of MC3R in the PVT alters anxiety-related behavior (Fig. 11), indicating a functional role for MC3R signaling in PVT in modulating anxiety state. This finding is consistent with a prior report indicating increased anxiety-related behavior in global MC3R KO mice (Sweeney et al., 2021b) and suggests that PVT is one region mediating the anxiogenic effects of MC3R deletion. Here, it is important to note that it is impossible to infer directionality from genetic loss of function studies (i.e., global or site-specific deletion of MC3R) because the dynamics of melanocortin peptide release in terminal regions, including PVT, are unknown. For example, the endogenous melanocortin receptor agonist aMSH is proposed to stimulate MC3R activity, whereas the antagonist AgRP likely inhibits receptor function. As AgRP mRNA levels are elevated in the fasted state, and aMSH levels are elevated in the sated state, the energy state of the animal may profoundly alter the physiological state of MC3R activity in PVT MC3R neurons. Thus, MC3R signaling in PVT may bidirectionally control anxiety-related behavior depending on the energy state of the animal, leading to anxiolytic effects in the fasted state (via AgRP-mediated inhibition of PVT MC3R neurons) or anxiogenic effects in the fed state (via aMSH-mediated activation of PVT MC3R neurons). Further work is required to determine the dynamics of endogenous melanocortin release in postsynaptic sites, such as PVT, and to decipher the intracellular signaling pathways by which melanocortins regulate the activity of MC3R-containing cells in PVT.

The previous literature supports an important role for PVT circuitry in regulating anxiety-related behavior (Kirouac, 2021), and emerging evidence suggests that posterior portions of PVT are particularly important for regulating anxiety-related behavior (relative to anterior PVT; Barson and Leibowitz, 2015; Barson et al., 2020). However, the direction of the observed effects is not always consistent. For example, activation of posterior PVT projections to the amygdala increases behavioral measures of fear and/or anxiety (Do-Monte et al., 2015; Penzo et al., 2015; Pliota et al., 2020), whereas inhibitory infusions of GABA agonists into the pPVT also increase measures of anxiety in the elevated plus maze in rats (Barson and Leibowitz, 2015). Thus, distinct PVT circuitry appear to exert unique effects on anxiety-related behavior depending on the specific downstream circuitry and/or the targeted cell types.

In contrast with the pPVT, the specific role of anterior PVT (aPVT) in anxiety-related behavior is less well established, and the direction of effects on anxiety is again inconsistent across studies (Barson et al., 2020). For instance, aPVT projections to the amygdala and nucleus accumbens promoted anxiety-related and aversive behaviors in one study (Do-Monte et al., 2017), whereas others have reported reduced anxiety-related behavior following activation of aPVT projections to nucleus accumbens (Cheng et al., 2018). Further work is required to establish the importance of anterior versus posterior PVT in the MC3R-related effects reported here. However, we propose that cell-type-specific approaches may be critical for dissecting PVT function, as distinct cell types likely exert specific control over behavior. Advances in understanding the molecular identity of PVT neurons, such as the recently published single nuclei transcriptome of PVT (Gao et al., 2023), should aid in defining the function of distinct PVT cell types and circuits in behavioral control. In addition to the anatomic specificity of PVT circuits, it is important to note that PVT neurons may be more active during the dark period (active period in rodents; Kolaj et al., 2012), and manipulations of PVT may have different effects depending on the time of day (McDevitt and Graziane, 2019; Barson and Leibowitz, 2015; Li et al., 2010a, b). Future work is required to map the temporal kinetics of PVT MC3R neurons across the light/dark cycle and to establish the effect of PVT MC3R manipulations during the dark period.

The neural circuitry regulating energy homeostasis is bidirectionally connected with neural circuitry controlling mood and anxiety-related behavior (Sweeney and Yang, 2017). These circuit interactions are likely involved in the underlying etiology of neuropsychiatric eating disorders and the established link among obesity, anxiety, and depressive disorders (Luppino et al., 2010; Blasco et al., 2020; Fulton et al., 2022). Here, we identify PVT neurons containing the MC3R as a molecularly defined cell type positioned between hypothalamic neurons communicating energy status (Fig. 1) and subcortical circuitry controlling anxiety-related behavior (Fig. 2). These findings add to the literature implicating PVT circuitry in anxiety-related behavior and provide a cellular entry point for further investigation of the neural circuit mechanisms mediating communication between energy state and emotional circuitry. Ultimately, a more comprehensive understanding of the molecular nature of this circuitry may provide therapeutic strategies for treating neuropsychiatric eating disorders and/or psychiatric conditions associated with obesity.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health–National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant R00DK127065 (P.S.), the Foundation for Prader Willi Research (P.S.), and Brain and Behavior Research Foundation Grant 100000874 (P.S.).

P.S. owns stock in Courage Therapeutics. All the other authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Aponte Y, Atasoy D, Sternson SM (2011) AGRP neurons are sufficient to orchestrate feeding behavior rapidly and without training. Nat Neurosci 14:351–355. 10.1038/nn.2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barson JR, Leibowitz SF (2015) GABA-induced inactivation of dorsal midline thalamic subregions has distinct effects on emotional behaviors. Neurosci Lett 609:92–96. 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.10.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barson JR, Mack NR, Gao WJ (2020) The paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus is an important node in the emotional processing network. Front Behav Neurosci 14:598469. 10.3389/fnbeh.2020.598469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedenbaugh MN, Brener SC, Maldonado J, Lippert RN, Sweeney P, Cone RD, Simerly RB (2022) Organization of neural systems expressing melanocortin-3 receptors in the mouse brain: evidence for sexual dimorphism. J Comp Neurol 530:2835–2851. 10.1002/cne.25379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betley JN, Cao ZFH, Ritola KD, Sternson SM (2013) Parallel, redundant circuit organization for homeostatic control of feeding behavior. Cell 155:1337–1350. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betley JN, Xu S, Cao ZFH, Gong R, Magnus CJ, Yu Y, Sternson SM (2015) Neurons for hunger and thirst transmit a negative-valence teaching signal. Nature 521:180–185. 10.1038/nature14416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler LR, Chen Y, Ahn JS, Lin YC, Essner RA, Knight ZA (2017) Dynamics of gut-brain communication underlying hunger. Neuron 96:461–475.e5. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.09.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasco BV, García-Jiménez J, Bodoano I, Gutiérrez-Rojas L (2020) Obesity and depression: its prevalence and influence as a prognostic factor: a systematic review. Psychiatry Investig 17:715–724. 10.30773/pi.2020.0099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett CJ, Li C, Webber E, Tsaousidou E, Xue SY, Brüning JC, Krashes MJ (2016) Hunger-driven motivational state competition. Neuron 92:187–201. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.08.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett CJ, Funderburk SC, Navarrete J, Sabol A, Liang-Guallpa J, Desrochers TM, Krashes MJ (2019) Need-based prioritization of behavior. Elife 8:e44527. 10.7554/eLife.44527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AA, Kesterson RA, Khong K, Cullen MJ, Pelleymounter MA, Dekoning J, Baetscher M, Cone RD (2000) A unique metabolic syndrome causes obesity in the melanocortin-3 receptor-deficient mouse. Endocrinology 141:3518–3521. 10.1210/endo.141.9.7791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campus P, Covelo IR, Kim Y, Parsegian A, Kuhn BN, Lopez SA, Neumaier JF, Ferguson SM, Solberg Woods LC, Sarter M, Flagel SB (2019) The paraventricular thalamus is a critical mediator of top down control of cuemotivated behavior in rats. Elife 8:e49041. 10.7554/eLife.49041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Lin YC, Kuo TW, Knight ZA (2015) Sensory detection of food rapidly modulates arcuate feeding circuits. Cell 160:829–841. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J, Wang J, Ma X, Ullah R, Shen Y, Zhou YD (2018) Anterior paraventricular thalamus to nucleus accumbens projection is involved in feeding behavior in a novel environment. Front Mol Neurosci 11:202. 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi EA, McNally GP (2017) Paraventricular thalamus balances danger and reward. J Neurosci 37:3018–3029. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3320-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi EA, Jean-Richard-Dit-Bressel P, Clifford CWG, McNally GP (2019) Paraventricular thalamus controls behavior during motivational conflict. J Neurosci 39:4945–4958. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2480-18.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone RD (2005) Anatomy and regulation of the central melanocortin system. Nat Neurosci 8:571–578. 10.1038/nn1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone RD (2006) Studies on the physiological functions of the melanocortin system. Endocr Rev 27:736–749. 10.1210/er.2006-0034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley MA, Smart JL, Rubinstein M, Cerdán MG, Diano S, Horvath TL, Cone RD, Low MJ (2001) Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in the arcuate nucleus. Nature 411:480–484. 10.1038/35078085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis GR, Oakes K, Barson JR (2021) Expression and distribution of neuropeptide-expressing cells throughout the rodent paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus. Front Behav Neurosci 14:634163. 10.3389/fnbeh.2020.634163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich MO, Zimmer MR, Bober J, Horvath TL (2015) Hypothalamic Agrp neurons drive stereotypic behaviors beyond feeding. Cell 160:1222–1232. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do-Monte FH, Quiñones-Laracuente K, Quirk GJ (2015) A temporal shift in the circuits mediating retrieval of fear memory. Nature 519:460–463. 10.1038/nature14030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do-Monte FH, Minier-Toribio A, Quiñones-Laracuente K, Medina-Colón EM, Quirk GJ (2017) Thalamic regulation of sucrose seeking during unexpected reward omission. Neuron 94:388–400.e4. 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.03.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]