Abstract

Background

Prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) is a serious infection associated with high mortality that often requires surgical treatment.

Methods

Study on clinical characteristics and prognosis of a large contemporary prospective cohort of prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) that included patients diagnosed between January 2008 and December 2020. Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with in-hospital mortality was performed.

Results

The study included 1354 cases of PVE. The median age was 71 years with an interquartile range of 62–77 years and 66.9% of the cases were male. Patients diagnosed during the first year after valve implantation (early onset) were characterized by a higher proportion of cases due to coagulase-negative staphylococci and Candida and more perivalvular complications than patients detected after the first year (late onset). In-hospital mortality of PVE in this series was 32.6%; specifically, it was 35.4% in the period 2008–2013 and 29.9% in 2014–2020 (p = 0.031). Variables associated with in-hospital mortality were: Age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index (OR: 1.15, 95% CI: 1.08–1.23), intracardiac abscess (OR:1.78, 95% CI:1.30–2.44), acute heart failure related to PVE (OR: 3. 11, 95% CI: 2.31–4.19), acute renal failure (OR: 3.11, 95% CI:1.14–2.09), septic shock (OR: 5.56, 95% CI:3.55–8.71), persistent bacteremia (OR: 1.85, 95% CI: 1.21–2.83) and surgery indicated but not performed (OR: 2.08, 95% CI: 1.49–2.89). In-hospital mortality in patients with surgical indication according to guidelines was 31.3% in operated patients and 51.3% in non-operated patients (p<0.001). In the latter group, there were more cases of advanced age, comorbidity, hospital acquired PVE, PVE due to Staphylococcus aureus, septic shock, and stroke.

Conclusions

Not performing cardiac surgery in patients with PVE and surgical indication, according to guidelines, has a significant negative effect on in-hospital mortality. Strategies to better discriminate patients who can benefit most from surgery would be desirable.

Introduction

Prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) constitutes 20–30% of cases of infective endocarditis (IE) and is associated with high mortality [1, 2]. The lesser detection of signs of PVE on imaging techniques, such as vegetations and/or periannular complications typical of IE, and the possible visualization of residual findings using these techniques, which could be explained by the previous valve surgery itself, makes it more challenging to establish an adequate diagnosis in cases of prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) compared to native valve endocarditis (NVE) [1–4].

The frequent extension of the infection around the prosthetic valve implies a greater challenge in surgical treatment compared to NVE [3, 5–7]. Patients who present surgical indication but do not undergo surgery are a matter of great concern that should be carefully analyzed for its prognostic implications [7, 8]. The percentage of patients with PVE and surgical indication who ultimately do not undergo surgery was higher than 40% in some series [9]. Among the reasons given for discouraging surgical intervention in these patients are severe sepsis, cerebral embolism, cardiogenic shock, and acute renal failure [10]. Improving knowledge of the prognostic variables of patients with PVE and the causes of disregard for surgical treatment seem to be important aspects to optimize the clinical management of these patients [11–13].

The aim of this study was to describe the clinical presentation and prognosis of patients with PVE. Specifically, we sought to explore the clinical characteristics and the prognosis of patients with surgical indication according to the guidelines who did not undergo surgery. To achieve this objective, we conducted an analysis of patients included in a large contemporary cohort of IE cases.

Patients and methods

From January 2008 to December 2020, consecutive patients with a definite diagnosis IE, according to Duke’s modified criteria, were prospectively included. These patients received treatment in a group of Spanish hospitals, collectively serving approximately 30% of the nation’s population. At each center, a multidisciplinary team completes a standardized form with the IE episode and a follow-up form after one year of the episode. The register included sections for demographic, clinical, microbiological, echocardiographic, management and prognostic information. The cohort registration received approval of regional and local ethics committees. Specifically, the Ethics and Clinical Research Board of one of participant hospitals approved the study protocol and publication of data (Gregorio Marañón Hospital in Madrid, number 18/07). Informed consent was obtained in cases where the patient could be adequately informed. For patients in coma or incapable of giving consent, the ethics committees waived the requirement for investigators to obtain consent to avoid patient inclusion bias. Data and samples were collected from January 2008 to December 2021. Subsequently, the study data were analyzed during the years 2022 and 2023. The authors did not have access to information that could identify individual participants during or after data collection.

Definitions

General variables

General definitions correspond to those published in other studies on endocarditis [14, 15]. Healthcare-associated infections were defined as previously published [16]. Patients were categorized into either early or late PVE, depending on whether the diagnosis was made before or after the first year following prosthetic valve implantation, respectively [1, 12]. Persistent bacteremia was defined as persistence of positive blood cultures after 7 days of appropriate antibiotic treatment initiation. Systemic embolization included embolism to any major arterial vessel, excluding stroke, which was defined by acute neurological deficit of vascular origin lasting >24 hours. Episodes with neurological symptoms lasting less than 24 hours, but showing imaging scans suggestive of infarction, were classified as stroke [17].

Exposures of interest

Surgical indications followed the latest current European guidelines available at the time of diagnosis [2, 18, 19]. Particular focus was directed to identifying patients with surgical indications and, within this group, those who were not operated on.

Outcomes of interest

In-hospital mortality and 1-year mortality were defined as death from any cause during hospital admission or within the 365 days following admission in which PVE was treated, respectively. Recurrent IE was defined as a new episode of IE during the first year of follow-up [20].

Patients

The study analyzed demographic, clinical, echocardiographic, and treatment data of the included patients, as well as morbidity and mortality both at admission and during the first year of follow-up. Endocarditis on transcatheter aortic valve replacement and infection of non-valve aortic graft were not included in the study due to their distinctive clinical characteristics [21, 22]. Patients with atrial or ventricular septal defect closure or cardiovascular implantable electronic devices infection were included only if they had a concomitantly infected prosthetic valve.

Statistical analysis

Categoric variables are expressed as absolute numbers and percentages. Quantitative variables are expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were compared using χ2 test or Fisher test when necessary. Quantitative variables were compared using Mann-Whitney’s U. In the comparison of risk factors for mortality, those variables with p < 0.10 in univariant analysis and that were considered clinically significant, were included in a multivariate logistic regression model, with a maximum of one variable for every 10 events (deaths). The goodness of fit of the final multivariate mode was assessed again by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Adjusted odds ratios and its 95% confident interval are provided. Bilateral p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 25 software (SPSS INC., Chicago, Illinois, USA). The data on which this study is based are available upon reasonable request through the technical office of the research network [(Spanish collaboration on endocarditis (GAMES)] which can be contacted via this e-mail: games08@gmail.com.

Results

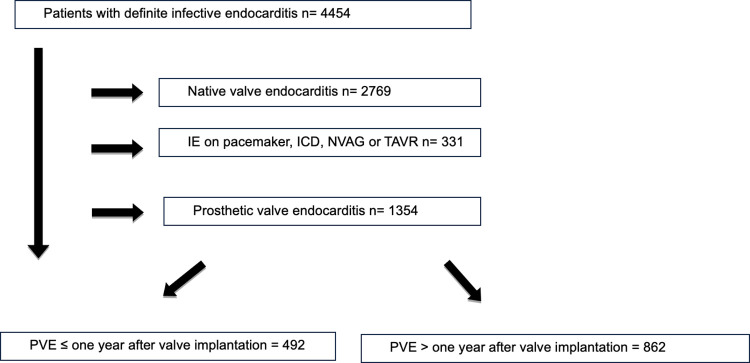

During the study period, a total of 4454 consecutive cases with definitive IE were identified. Among them, 1354 cases (30.4%) corresponded to PVE (Fig 1). Out of the PVE cases, 492 (36.3%) were diagnosed within the first year after prosthetic valve implantation (early PVE) while 862 cases (63.6%) were diagnosed after the first year (late PVE). The proportion of PVE cases over the total of IE cases was 29.7% between 2008 and 2013 (672 out of 2264 cases) and 31.4% between 2014 and 2020 [(682 out of 2190 cases); p = 0.290]). Among the PVE cases, 633 involved mechanical valves (47%), and 718 involved biological valves (53.9%). The number of infected mechanical prostheses in the mitral position was 354 out of 515 prosthetic valves (68,7%) and 358 out of 969 prosthetic valves in the aortic position (36.9%; p<0.001). Simultaneous involvement of prosthetic valves in both the aortic and mitral positions occurred in 173 cases (12.7%).

Fig 1. Flowchart of patients presenting with definite or possible infective endocarditis (IE) according to the type of affected valve (games cohort 2008–2020).

ICD: implantable cardioverter defibrillator. NVAG: non-valve aortic graft. TAVR: transcatheter aortic valve replacement. PVE: prosthetic valve endocarditis.

Clinical characteristics and outcome of patients with PVE

Patients with PVE were older, had a higher comorbidity burden, a greater proportion of patients with surgical indications who did not undergo surgery, and higher mortality compared to patients with NVE (Table 1). The indication of surgery of the episodes of PVE compared to episodes of NVE are shown in Table 1S in the S1 Data. Table 2S in the S1 Data presents a comparison of clinical characteristics between patients with only aortic or mitral prosthetic valve involvement. Patients with aortic PVE were older, had a higher incidence of early PVE, a higher frequency of coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), and more intracardiac complications than patients with mitral PVE.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients with native valve endocarditis compared patients with prosthetic valve endocarditis.

| Native (n = 2769) | Prosthetic (n = 1354) | Overall (N = 4123) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age. years (IQR) | 66 (53–76) | 71 (62–77) | 68 (57–76) | <0.001 |

| Male gender | 1897 (68.5) | 903 (66.9) | 2800 (67.9) | 0.240 |

| Hospital-acquired | 590 (21.3) | 515 (38.0) | 1105 (26.8) | <0.001 |

| Site of infection | ||||

| Aortic | 1386 (50.1) | 969 (71.6) | 2355 (57.1) | <0.001 |

| Mitral | 1469 (53.1) | 515 (38.0) | 1984 (48.1) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Coronary disease | 556 (20.1) | 471 (34.7) | 1027 (24.9) | <0.001 |

| Chronic heart failure | 661 (23.9) | 609 (44.9) | 1270 (30.8) | <0.001 |

| Intravenous drug user | 109 (3.9) | 10 (0.7) | 119 (2.8) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 282 (10.2) | 235 (17.3) | 517 (12.5) | <0.001 |

| Chronic renal failure | 664 (24.0) | 357 (26.4) | 1021 (24.7) | 0.095 |

| Chronic liver disease | 339 (12.2) | 95 (7.1) | 434 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| Age-adjusted Charlson index (IQR) | 4 (3–6) | 5 (3–7) | 5 (3–7) | <0.001 |

| Microbiology | ||||

| Gram-positive bacteria | ||||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 766 (27.7) | 208 (15.4) | 974 (23.6) | <0.001 |

| MRSA | 116 (4.1) | 42 (3.1) | 158 (3.8) | 0.088 |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | 285 (10.3) | 437 (32.3) | 722 (17.5) | <0.001 |

| Enterococcus spp | 441 (15.9) | 217 (16.0) | 658 (15.9) | 0.934 |

| Streptococcus spp | 932 (33.7) | 262 (19.4) | 1194 (28.9) | <0.001 |

| Gram-negative bacilli | 91 (3.3) | 63 (4.7) | 154 (3.7) | 0.030 |

| Anaerobic bacteria | 16 (0.6) | 30 (2.2) | 46 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Fungi | ||||

| Candida spp | 31 (1.1) | 33 (2.4) | 64 (1.5) | 0.001 |

| Other fungi | 10 (0.4) | 2 (0.1) | 12 (0.3) | 0.358 |

| Polymicrobial | 34 (1.2) | 18 (1.3) | 52 (1.2) | 0.784 |

| Other microorganisms | 65 (2.3) | 36 (2.7) | 101 (2.4) | 0.544 |

| Negative cultures (no growth) | 78 (2.8) | 37 (2.7) | 115 (2.7) | 0.877 |

| Echocardiographic findings | ||||

| Vegetation | 2359 (85.2) | 928 (68.5) | 3287 (79.7) | <0.001 |

| Intracardiac complications | 971 (35.1) | 569 (42.0) | 1540 (37.3) | <0.001 |

| Valve perforation or rupture | 633 (22.9) | 50 (3.6) | 683 (16.5) | <0.001 |

| Pseudoaneurysm | 144 (5.2) | 148 (10.9) | 292 (7.0) | <0.001 |

| Perivalvular abscess | 366 (13.2) | 460 (34.0) | 826 (20.0) | <0.001 |

| Intracardiac fistula | 59 (2.1) | 63 (4.6) | 122 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Clinical course | ||||

| Acute heart failure | 1271 (45.9) | 542 (40.0) | 1813 (43.9) | <0.001 |

| Persistent bacteremia | 326 (11.8) | 153 (11.3) | 479 (11.6) | 0.656 |

| Stroke | 602 (21.7) | 320 (23.6) | 922 (22.3) | 0.171 |

| Embolism a | 721 (26.0) | 285 (21.0) | 1006 (24.3) | <0.001 |

| Mycotic aneurism | 75 (2.7) | 30 (2.2) | 105 (2.5) | 0.345 |

| Acute renal failure | 948 (34.2) | 571 (42.1) | 1519 (36.8) | <0.001 |

| Septic shock | 376 (13.6) | 183 (13.5) | 559 (13.5) | 0.955 |

| Surgical indication | 1887 (68.1) | 1009 (74.5) | 2896 (70.2) | <0.001 |

| Surgery performed b | 1306 (69.2) | 650 (64.4) | 1956 (67.5) | 0.009 |

| Surgery indicated. not performed | 581 (30.8) | 359 (35.6) | 940 (32.4) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality | 709 (25.6) | 442 (32.6) | 1151 (27.9) | <0.001 |

| First year mortality | 876 (31.6) | 507 (37.4) | 1383 (33.5) | <0.001 |

| Recurrence c | 28 (1.3) | 21 (2.3) | 49 (1.6) | 0.063 |

IQR: Interquartile range. MRSA: methicillin-resistant S. aureus.

a Excluding cases with stroke.

b Percentages calculated considering only patients with surgical indications.

c during the first year after diagnosis calculated on patients discharged from the hospital (n = 2972).

Seventy cases (5.1%) showed concomitant involvement of native and prosthetic valves.

CoNS were the most common bacteria causing PVE in this series. The proportion of CoNS PVE cases increased from 30.5% in the first period (2008–2013) to 34% in the second period (2014–2020), although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.167, Table 3S in the S1 Data). In addition, CoNS were identified in 43.5% of early PVE cases during the first period (2008–2013) and in 54.3% during the second period (2014–2020; p = 0.017). Staphylococcus aureus caused 20% of PVE cases on mechanical valves and 11.3% on biological valves (p<0.0019. in cases due to CoNS, this proportion was 27.8% and 36.2%, respectively (p = 0.001).

In-hospital mortality of PVE in this series was 32.6% (Table 1). Table 2 shows the characteristics of the patients according to in-hospital mortality. Variables independently associated with in-hospital mortality were age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index (OR: 1.15, 95% CI: 1.08–1.23), intracardiac abscess (OR:1.78, 95% CI:1.30–2.44), acute heart failure related to PVE (OR: 3. 11, 95% CI: 2.31–4.19), acute renal failure (OR: 3.11, 95% CI:1.14–2.09), septic shock (OR: 5.56, 95% CI:3.55–8.71), persistent bacteremia (OR: 1.85, 95% CI: 1.21–2.83) and surgery indicated but not performed (OR: 2.08, 95% CI: 1.49–2.89) (Table 3). Given the significant association between septic shock and in-hospital mortality, a multivariate analysis was performed without this variable (Table 4). The result was very similar, except that mitral involvement and PVE due to S. aureus were identified as independent prognostic variables in this second analysis, and persistent bacteremia was no longer statistically significant.

Table 2. Characteristics of patients with PVE according to in-hospital mortality.

| Survivors (n = 912) | Non-survivors (n = 442) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age. years (IQR) | 69 (61–76) | 73 (65–78) | <0.001 |

| Male gender | 623 (68.3) | 280 (63.3) | 0.069 |

| Hospital-acquired | 313 (34.3) | 202 (45.7) | <0.001 |

| Site of infection | |||

| Aortic | 645 (70.7) | 324 (73.3) | 0.324 |

| Mitral | 322 (35.3) | 193 (43.7) | 0.003 |

| Tricuspid | 13 (1.4) | 3 (0.7) | 0.293 |

| Pulmonary | 25 (2.7) | 2 (0.5) | 0.005 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Chronic heart failure | 380 (41.6) | 229 (51.8) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 250 (27.4) | 155 (35.0) | 0.004 |

| Intravenous drug user | 10 (1.0) | 0 | - |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 70 (7.6) | 57 (12.8) | 0.002 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 153 (16.6) | 82 (18.5) | 0.419 |

| Neoplasia | 139 (15.2) | 77 (17.4) | 0.304 |

| Chronic renal failure | 207 (22.7) | 150 (33.9) | <0.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 55 (6.0) | 40 (9.0) | 0.041 |

| Congenital heart disease | 68 (7.4) | 16 (3.6) | 0.006 |

| Age-adjusted Charlson index (IQR) | 4 (3–6) | 5 (4–7) | <0.001 |

| Early PVE | 319 (35.0) | 173 (39.1) | 0.135 |

| Late PVE | 593 (65.0) | 269 (60.9) | 0.135 |

| Microbiology | |||

| Gram-positive bacteria | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 105 (11.5) | 103 (23.3) | <0.001 |

| CoNS | 285 (31.3) | 152 (34.4) | 0.247 |

| Enterococcus | 161 (17.7) | 56 (12.7) | 0.019 |

| Streptococcus | 199 (21.8) | 63 (14.3) | 0.001 |

| Gram-negative bacilli | 45 (4.9) | 18 (4.1) | 0.480 |

| Anaerobic bacteria | 24 (2.6) | 6 (1.4) | 0.135 |

| Fungi | |||

| Candida | 17 (1.9) | 16 (3.6) | 0.049 |

| Other fungal species | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0.546 |

| Polymicrobial | 11 (1.2) | 7 (1.6) | 0.569 |

| Other microorganisms | 27 (3.0) | 9 (2.0) | 0.322 |

| Echocardiographic findings | |||

| Vegetation | 615 (67.4) | 313 (70.8) | 0.209 |

| Intracardiac complications | 344 (37.7) | 225 (50.9) | <0.001 |

| Valve perforation or rupture | 25 (2.7) | 25 (5.6) | 0.008 |

| Pseudoaneurysm | 90 (9.8) | 58 (13.1) | 0.072 |

| Perivalvular abscess | 286 (31.4) | 174 (39.4) | 0.012 |

| Intracardiac fistula | 40 (4.3) | 23 (5.5) | 0.503 |

| Clinical course | |||

| Acute heart failure | 271 (29.7) | 271 (61.3) | <0.001 |

| Persistent bacteremia | 86 (9.4) | 67 (15.1) | 0.002 |

| Stroke | 176 (19.2) | 144 (32.5) | <0.001 |

| Embolism a | 192 (21.0) | 93 (21.0) | 0.996 |

| Acute renal failure | 317 (34.7) | 254 (57.4) | <0.001 |

| Septic shock | 43 (4.7) | 140 (31.6) | <0.001 |

| Surgical indication | 622 (68.2) | 387 (87.6) | <0.001 |

| Surgery performed b | 447 (71.9) | 203 (52.4) | 0.238 |

| Surgery indicated not performed | 175 (28.1) | 184 (47.6) | <0.001 |

IQR: Interquartile range.

a Excluding cases with stroke.

b Percentages calculated considering only patients with surgical indications.

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of clinical factors of PVE associated with in-hospital mortality.

| OR | CI 95% | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 1.08 | 0.99–1.22 | 0.255 |

| Mitral affected | 1.33 | 0.97–1.81 | 0.070 |

| Age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity, points | 1.15 | 1.08–1.23 | <0.001 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1.38 | 0.91–2.09 | 0.120 |

| Acute heart failure | 3.11 | 2.31–4.19 | <0.001 |

| Persistent bacteremia | 1.85 | 1.21–2.83 | 0.005 |

| Septic Shock | 5.56 | 3.55–8.71 | <0.001 |

| Acute renal failure | 1.55 | 1.14–2.09 | 0.005 |

| Nosocomial | 1.23 | 0.91–1.67 | 0.165 |

| Intracardiac Abscess | 1.78 | 1.30–2.44 | <0.001 |

| Surgery indicated. not performed | 2.08 | 1.49–2.89 | <0.001 |

Table 4. Multivariate analysis of clinical factors of PVE associated with in-hospital mortality without considering “septic shock”.

| OR | CI 95% | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 1.07 | .99–1.01 | 0.226 |

| Mitral affected | 1.36 | 1.03–1.78 | 0.026 |

| Age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity, points | 1.12 | 1.05–1.19 | <0.001 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1.86 | 1.31–2.64 | <0.001 |

| Acute heart failure | 3.08 | 2.37–4.01 | <0.001 |

| Persistent bacteremia | 1.46 | .99–1.01 | 0.055 |

| Acute renal failure | 1.82 | 1.39–2.37 | <0.01 |

| Nosocomial | 1.35 | 1.03–1.76 | 0.028 |

| Intracardiac Abscess | 1.66 | 1.26–2.20 | <0.001 |

| Surgery indicated. not performed | 2.34 | 1.75–3.11 | <0.001 |

A comparison of patient characteristics was made according to the period in which the diagnosis was made (2008–2013 vs. 2014–2020; Table 3S in the S1 Data). It was evident that comorbidity, late PVE, intracardiac complications and septic shock were more frequent in patients treated during the second period (2014–2020). Additionally, in-hospital mortality in the second period (29.9%) was lower than in the first period (35.4%, p = 0.031).

Clinical characteristics and outcome of patients with surgical indication that were not operated on

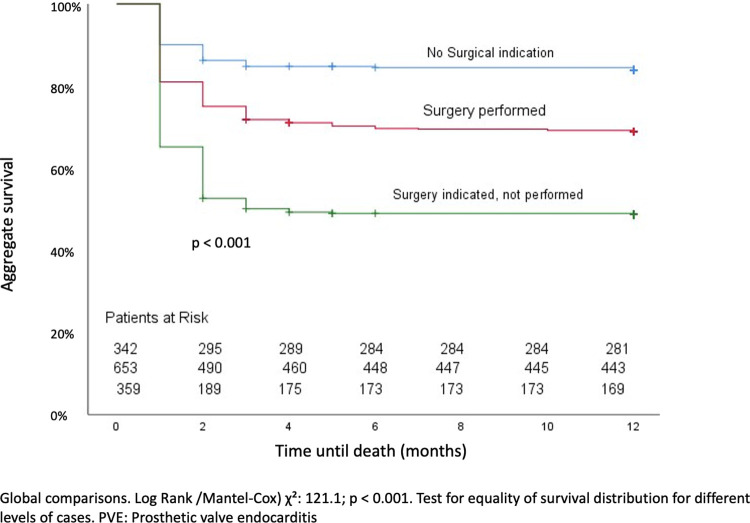

One thousand and nine patients presented surgical indication (74.5%). Six hundred fifty patients (64.4%) underwent surgery, and 359 patients (35.6%) were managed conservatively, with antibiotic treatment only (Table 5). Patients who did not undergo surgery were older, had higher frequency of chronic lung disease, chronic heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, neoplasia, previous renal failure and chronic liver disease with a significant difference in the age-adjusted Charlson index 6 points (IQR: 4–8 points) versus 4 points (IQR: 3–6 points; p = <0.001), respectively. Nosocomial acquisition of infection, PVE due to S. aureus, septic shock and brain involvement were also more frequent among the non-operated patients (Table 2). In-hospital mortality was significantly higher among patients who did not undergo surgery (51.3%) compared to those who underwent surgery (31.3%, p<0.001). Fig 2 shows the survival during the first year in patients without surgical indication, with surgical indication who underwent surgery and with surgical indication who did not undergo surgery.

Table 5. Characteristics of patients with PVE and surgical indication according to whether the patient underwent surgery.

| Surgery performed (n = 650) | Surgery not performed (n = 359) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age. years (IQR) | 69 (59–75) | 73 (65–79) | <0.001 |

| Male gender | 449 (69.0) | 233 (64.9) | 0.175 |

| Hospital-acquired | 247 (38.0) | 158 (44.0) | 0.062 |

| Site of infection | |||

| Aortic | 477 (73.4) | 264 (73.5) | 0.958 |

| Mitral | 229 (35.2) | 147 (40.9) | 0.072 |

| Tricuspid | 7 (1.1) | 8 (2.2) | 0.148 |

| Pulmonary | 11 (1.7) | 9 (2.5) | 0.374 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Chronic heart failure | 273 (42.0) | 195 (54.3) | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 186 (28.6) | 107 (29.8) | 0.690 |

| Intravenous drug user | 5 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) | 0.571 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 49 (7.5) | 42 (11.7) | 0.027 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 111 (17.0) | 60 (16.7) | 0.883 |

| Neoplasia | 74 (11.3) | 75 (20.8) | <0.001 |

| Chronic renal failure | 137 (21.1) | 125 (34.8) | <0.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 35 (5.3) | 42 (11.7) | <0.001 |

| Congenital heart disease | 53 (8.1) | 18 (5.0) | 0.062 |

| Age-adjusted Charlson index (IQR) | 4 (3–6) | 6 (4–8) | <0.001 |

| Early PVE | 255 (39.2) | 134 (37.3) | 0.552 |

| Late PVE | 395 (60.8) | 225 (62.7) | 0.552 |

| Microbiology | |||

| Gram-positive bacteria | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 86 (13.2) | 81 (22.6) | <0.001 |

| CoNS | 245 (37.7) | 120 (33.4) | 0.177 |

| Enterococcus | 88 (13.5) | 51 (14.2) | 0.768 |

| Streptococcus | 108 (16.6) | 57 (15.9) | 0.762 |

| Gram-negative bacilli | 20 (3.1) | 18 (5.0) | 0.122 |

| Anaerobic bacteria | 25 (3.8) | 0 | - |

| Fungi | |||

| Candida | 18 (2.8) | 11 (3.1) | 0.788 |

| Other fungal species | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0.670 |

| Polymicrobial | 8 (1.2) | 5 (1.4) | 0.827 |

| Other microorganisms | 23 (3.5) | 6 (1.7) | 0.089 |

| Echocardiographic findings | |||

| Vegetation | 460 (70.8) | 251 (69.9) | 0.776 |

| Intracardiac complications | 373 (57.4) | 158 (44.0) | <0.001 |

| Valve perforation or rupture | 35 (5.3) | 14 (3.9) | 0.293 |

| Pseudoaneurysm | 91 (14.0) | 45 (12.5) | 0.514 |

| Perivalvular abscess | 311 (47.8) | 120 (33.4) | <0.001 |

| Intracardiac fistula | 43 (6.6) | 17 (4.7) | 0.227 |

| Clinical course | |||

| Acute heart failure | 294 (45.2) | 177 (49.3) | 0.214 |

| Persistent bacteremia | 67 (10.3) | 51 (14.2) | 0.065 |

| Stroke | 146 (22.4) | 102 (28.4) | 0.036 |

| Embolism a | 146 (22.4) | 82 (22.8) | 0.89 |

| Acute renal failure | 289 (44.4) | 169 (47.0) | 0.425 |

| Septic shock | 74 (11.3) | 86 (23.9) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality | 203 (31.3) | 184 (51.3) | <0.001 |

| First year mortality | 232 (35.7) | 201 (55.9) | <0.001 |

| Recurrence | 7 (1.5) | 4 (2.8) | 0.540 |

IQR: Interquartile range. CoNS: Coagulase-negative staphylococci.

a Excluding cases with stroke

Fig 2. Survival of patient with PVE according to surgery performance.

The reasons given for not performing the intervention were as follows: severe hemodynamic instability leading to poor prognosis (75 patients, 20.9%), neurological complications (73 patients, 20.3%), challenging surgical procedures (45 patients, 12.5%), other medical causes (74 patients, 20.6%), patient refusal (52 patients, 14.5%) and death of the patient during the discussion of the feasibility of intervention (40 patients, 11.1%).

Clinical characteristics and outcome of patients with PVE according to time of onset

Patients diagnosed during the first year after prosthetic valve implantation had a higher frequency of coronary artery disease, chronic renal failure or liver disease, hospital acquisition, aortic PVE and intracardiac complications (such as pseudoaneurysm or abscess) and a lower frequency of mitral and tricuspid valve involvement compared to patients diagnosed with late PVE (Table 4S in the S1 Data). Regarding microbiology, there were more cases due to CoNS and Candida and fewer cases of S. aureus and Streptococcus. Mortality in patients with early PVE was 35.2% and that of patients with late PVE was 31.2% (p = 0.132, Table 4S in the S1 Data) Comparison of the characteristics of patients with PVE who had surgical indication depending on whether they underwent surgery or not and considering separately by the time of onset of PVE (early or late) is presented in Tables 5S and 6S in the S1 Data.

Discussion

We present a comprehensive series of PVE characterized by patients with advanced age and marked comorbidity, as well as by an important role played by CoNS and by the fact that one third of the cases were not operated despite having a surgical indication.

Clinical characteristics and outcome of patients with PVE

Patients with PVE are generally older and have more comorbidities compared to patients with NVE, as has also been evidenced in previous studies [1, 3, 23]. A higher frequency of cases due to CoNS with less involvement of S. aureus and Streptococcus has also been reported [3, 7]. The incidence of PVE due to CoNS was also higher in our study than the 16.9% recorded in another large series of patients diagnosed between 2000 and 2005 [13]. As an additional fact about etiology, it should be noted the greater tendency for S. aureus to infect mechanical valves and for CoNS and Enterococcus to infect biological valves. Although we have not found other studies with similar results, we consider it relevant to study in the future the possible differences in the adherence of bacteria depending on the material of which prosthetic valves are made, due to their possible preventive or therapeutic implications.

Mortality among PVE cases was higher than in NVE cases, however, however, there are studies showing that mortality, when adjusted for risk factors, may be equal to or even lower than that of patients with NVE [3]. Our study identified several variables independently associated with in-hospital mortality, consistent with previous research. These included baseline patient characteristics (age and comorbidity) [13, 23], the development of acute heart failure [2, 7, 13, 24], perivalvular complications [7, 8, 11], severity of infection indicated by septic shock or persistent bacteremia [13] and cases with surgical indication that were not operated on [8, 25]. The reduction in mortality over time observed in this study has also been evidenced in previous investigations [23, 26]. However, we have not found a clear reason for this finding beyond the slightly higher number of patients who underwent TEE during the second period compared to the first. Advances made in recent years in diagnostic acuity, imaging techniques and surgical treatment may have influenced the reduction in mortality during the second period despite including patients with higher severity [8, 23].

Clinical characteristics and outcome of patients with surgical indication who were not operated on

As seen in previous studies, the decision to forgo surgery in patients with surgical indication has a significant impact on prognosis [8]. Among patients who did not undergo surgery, there was a notable tendency to be older and with more comorbidities. Although patients older than 65 years tend to have worse prognosis due to comorbidities, age alone should not be an exclusive factor to exclude surgery [27–29]. Of note, patients with chronic liver disease underwent surgery less frequently and experienced higher mortality. It is suggested to consider the status of liver disease (Child-Pugh score) before ruling out surgical intervention in these cases [28]. Surprisingly, cases due to S. aureus, which usually require surgical treatment, were operated less frequently. This could be explained by the higher frequency of severe systemic infection, secondary septic foci, or greater surgical complexity in these patients [9, 29]. Similarly, cases with central nervous system involvement were also less likely to receive surgery. Adequate assessment of the type and extent of stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) is essential before discouraging surgery [30]. Considering the improved survival rates in recent years, physicians should strive to identify patients with poor prognostic factors who may still benefit from surgery [1, 27, 31]. Strategies to reduce the number of patients denied surgery may include better patient education about treatment options, adherence to recommended surgical timelines (emergent, urgent, or elective), and facilitation of transfers to hospitals with expertise in complex surgery.

Clinical characteristics of patients with PVE according to time of onset

When comparing patients who were diagnosed within the first year after valve implantation with those diagnosed later, we observed more cases of nosocomial origin, as would be expected. A higher incidence of intracardiac complications during the first year was also detected, emphasizing the increased importance, if possible, of performing transesophageal echocardiography and other imaging tests such as positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) or cardiac CT in suspected cases of early PVE [8, 11, 32]. The percentage of CoNS causing late PVE was lower than that observed in early PVE cases. Despite this fact, empirical coverage for CoNS could be advisable in late PVE given that it originated 23% of these cases. The occurrence of PVE due to Candida was also significantly lower in late cases (1.2% vs. 4.7% in early cases). Given these low figures, empirical treatment with antifungals in early PVE may not be justified.

Limitations

Firstly, we must acknowledge the extended duration of the study, which could have led to differences in the diagnosis and treatment approaches over time. It is also necessary to take into account the impact of changes in diagnosis and treatment of the different IE guidelines considered over time on the homogeneity of the patients included in the study. Finally, we must point out the fact that many patients were referred from hospitals without cardiac surgery, which could have influenced the etiology and certain characteristics of the patients studied. More severe or milder cases could have been transferred less frequently because surgical intervention can be ruled out at the outset. However, these differences should not be very important considering the fluid communication and adequate coordination between the hospitals without cardiac surgery and the referral hospitals.

Conclusions

Patients with PVE account for nearly one third of all episodes of infective endocarditis (IE) and are characterized by advanced age, marked comorbidity, and a prominent role of CoNS, even in late-onset PVE. The proportion of patients with a surgical indication who do not undergo surgery is significant and is associated with higher mortality rates. Efforts should be made to better identify patients who might benefit most from surgery, including consideration of transfer to referral centers, in order to reduce rejection and delay in the performance of the surgery.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Iván Adán for his task as data coordinator of the GAMES cohort and for his statistical support. We are grateful for the contribution of Juan Rivera Rodríguez in the grammatical revision of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- IE

infective endocarditis

- PVE

prosthetic valve endocarditis

- NVE

native valve endocarditis

- CoNS

coagulase-negative staphylococci

- CT

Computed tomography

Data Availability

There is a restriction when it comes to sharing the data set, since both the Research Ethics Committee that approved the study and the data protection legislation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the European Council of 27 April 2016 on Data Protection (RGPD) only allow sharing patient data with health authorities and/or third parties if there is express consent from the data subject. The informed consent signed by our patients did not include the possibility that third parties could freely access their medical information containing some particularly sensitive data such as date of birth, initials, date of admission and discharge and the hospital where the patient was admitted. However, this information can be obtained in justified cases by contacting Ivan Adan from the technical office of the GAMES research network by e-mail: games08@gmail.com.

Funding Statement

The author received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Hussain ST, Shrestha NK, Gordon SM, Houghtaling PL, Blackstone EH, Pettersson GB. Residual patient, anatomic, and surgical obstacles in treating active left-sided infective endocarditis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148(3):981–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, Del Zotti F, et al. 2015. ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 21;36(44):3075–3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber C, Petrov G, Luehr M, Aubin H, Tugtekin SM, Borger MA, et al. Surgical results for prosthetic versus native valve endocarditis: A multicenter analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021; 161: 609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.09.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martínez A, Pubul V, Jokh EA, Martínez A, El-Diasty M, Fernández AL. Surgicel-Related Uptake on Positron Emission Tomography Scan Mimicking Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021. Nov;112(5):e317–e319. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.02.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robles P. Judicious use of transthoracic echocardiography in the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Heart. 2003. Nov;89(11):1283–1284. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.11.1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pettersson GB, Hussain ST, Shrestha NK, Gordon S, Fraser TG, Ibrahim KS, et al. Infective endocarditis: an atlas of disease progression for describing, staging, coding, and understanding the pathology. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014. Apr;147(4):1142–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weber C, Rahmanian PB, Nitsche M, Gassa A, Eghbalzadeh K, Hamacher S, et al. Higher incidence of perivalvular abscess determines perioperative clinical outcome in patients undergoing surgery for prosthetic valve endocarditis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Habib G, Erba PA, Iung B, Donal E, Cosyns B, Laroche C, et al. Clinical presentation, aetiology and outcome of infective endocarditis. Results of the ESC-EORP EURO-ENDO (European infective endocarditis) registry: A prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(39):3222–3232. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sáez C, Sarriá C, Vilacosta I, Olmos C, López J, García-Granja PE, et al. A contemporary description of staphylococcus aureus prosthetic valve endocarditis. Differences according to the time elapsed from surgery". Medicine (Baltimore). 2019. Aug;98(35):e16903. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alonso-Valle H, Fariñas-Alvarez C, García-Palomo JD, Bernal JM, Martín-Durán R, Gutiérrez Díez JF, et al. Clinical course and predictors of death in prosthetic valve endocarditis over a 20-year period. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010. Apr;139(4):887–893. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.05.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JH, Burner KD, Fealey ME, Edwards WD, Tazelaar HD, Orszulak TA, et al. Prosthetic valve endocarditis: Clinicopathological correlates in 122 surgical specimens from 116 patients (1985–2004). Cardiovasc Pathol [Internet]. 2011;20(1):26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2009.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, Fowler VG Jr, Tleyjeh IM, Rybak MJ, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: Diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015. Oct 13;132(15):1435–1486. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang A, Athan E, Pappas PA, Fowler VG Jr, Olaison L, Paré C, et al. Contemporary clinical profile and outcome of prosthetic valve endocarditis. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;297(12):1354–1361. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.12.1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pericàs JM, Llopis J, Muñoz P, Gálvez-Acebal J, Kestler M, Valerio M, et al. A Contemporary Picture of Enterococcal Endocarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020. Feb;75(5):482–494. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goenaga Sánchez MÁ, Kortajarena Urkola X, Bouza Santiago E, Muñoz García P, Verde Moreno E, Fariñas Álvarez MC, et al. Aetiology of renal failure in patients with infective endocarditis. The role of antibiotics. Med Clin (Barc). 2017. Oct 23;149(8):331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benito N, Miró JM, de Lazzari E, Cabell CH, del Río A, Altclas J, et al. Health care-associated native valve endocarditis: importance of non-nosocomial acquisition. Ann Intern Med. 2009. May;150(9):586–594. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sacco RL, Kasner SE, Broderick JP, Caplan LR, Connors JJ, Culebras A, et al. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013. Jul;44(7):2064–2089. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e318296aeca [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horstkotte D, Follath F, Gutschik E, Lengyel M, Oto A, Pavie A, et al. Guidelines on prevention, diagnosis and treatment of infective endocarditis executive summary; the task force on infective endocarditis of the European society of cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004. Feb;25(3):267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Habib G, Hoen B, Tornos P, Thuny F, Prendergast B, Vilacosta I, et al. Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009): the Task Force on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2009. Oct;30(19):2369–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Appa A, Adamo M, Le S, et al. Patient-Directed Discharges Among Persons Who Use Drugs Hospitalized with Invasive Staphylococcus aureus Infections: Opportunities for Improvement. Am J Med. 2022. Jan;135(1):91–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Del Val D, Panagides V, Mestres CA, Miró JM, Rodés-Cabau J. Infective Endocarditis After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023. Jan 31;81(4):394–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.García-Arribas D, Olmos C, Vilacosta I, Perez-García CN, Ferrera C, Jerónimo A, et al. Infective endocarditis in patients with aortic grafts. Int J Cardiol. 2021. May 1;330: 148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan MZ, Munir MB, Khan MU, Khan SU, Vasudevan A, Balla S. Contemporary Trends and Outcomes of Prosthetic Valve Infective Endocarditis in the United States: Insights From the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. Am J Med Sci. 2021. Nov;362(5):472–479. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2021.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.López J, Sevilla T, Vilacosta I, García H, Sarriá C, Pozo E, Silva J, et al. Clinical significance of congestive acute heart failure in prosthetic valve endocarditis. A multicenter study with 257 patients. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2013. May;66(5):384–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lalani T, Chu VH, Park LP, Cecchi E, Corey GR, Durante-Mangoni E, et al. In-hospital and 1-year mortality in patients undergoing early surgery for prosthetic valve endocarditis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013. Sep 9;173(16):1495–1504. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perrotta S, Jeppsson A, Fröjd V, Svensson G. Surgical Treatment of Aortic Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis: A 20-Year Single-Center Experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016. Apr;101(4):1426–32. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.07.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliver L, Lavoute C, Giorgi R, Salaun E, Hubert S, Casalta JP, et al. Infective endocarditis in octogenarians. Heart. 2017. Oct;103(20):1602–1609. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruiz-Morales J, Ivanova-Georgieva R, Fernández-Hidalgo N, García-Cabrera E, Miró JM, Muñoz P, et al. Left-sided infective endocarditis in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Infect. 2015. Dec;71(6):627–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ragnarsson S, Salto-Alejandre S, Ström A, Olaison L, Rasmussen M. Surgery Is Underused in Elderly Patients With Left-Sided Infective Endocarditis: A Nationwide Registry Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021. Oct 5;10(19):e020221. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.020221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang LQ, Cho S-M, Rice CJ, Khoury J, Marquardt RJ, Buletko AB, et al. Valve surgery for infective endocarditis complicated by stroke: surgical timing and perioperative neurological complications. Eur J Neurol. 2020. Dec;27(12):2430–2438. doi: 10.1111/ene.14438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu VH, Park LP, Athan E, Delahaye F, Freiberger T, Lamas C, et al. Association between surgical indications, operative risk, and clinical outcome in infective endocarditis: a prospective study from the International Collaboration on Endocarditis. Circulation. 2015. Jan;131(2):131–140. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sohail MR, Martin KR, Wilson WR, Baddour LM, Harmsen WS, Steckelberg JM. Medical versus surgical management of Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic valve endocarditis. Am J Med. 2006;119(2):147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.09.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]