Abstract

Cancer immunoprevention, the engagement of the immune system to prevent cancer, is largely overshadowed by therapeutic approaches to treating cancer after detection. Vaccines, or alternatively, the utilization of genetically engineered memory T cells, could be methods of engaging and creating cancer specific T cells with superb memory, lenient activation requirements, potent antitumor cytotoxicity, tumor surveillance, and resilience against immunosuppressive factors in the tumor microenvironment. This review analyzes memory T cell subtypes based on their potential utility in cancer immunoprevention with regard to longevity, localization, activation requirements, and efficacy in fighting cancers. A particular focus is on how both tissue-resident memory T cells and stem memory T cells could be promising subtypes for engaging in immunoprevention.

Background/introduction:

The prognosis of various cancers/neoplasms is dramatically better when the tumor is detected early (1). Similarly, the widespread usage of cancer vaccines for oncogenic viruses, such as the human papilloma virus (HPV) and hepatitis B (HBV) vaccines, has led to a decrease in the incidence of cancers caused by those viral infections (2, 3). As the incidence of cancer continues to rise (4), we need to innovate better methods for the prevention or early detection of cancer.

Preventive approaches to cancer are likely to be more effective than therapeutics. As cancer progresses and becomes more metastatic, it often gains more mutations (5) and generates a more immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME). The immune system is already quite effective in combating cancer, however, through immunoediting, cancer cells can escape elimination, exhaust T cells, activate tolerogenic regulatory T (TREG) cells, and outcompete immune cells for resources (6–9). One could potentially overcome immune escape by either increasing the frequency of certain subtypes of non-exhausted tumor-specific lymphocytes, or by altering those existing lymphocytes to be less affected by immunoedited cancer cells. Hence, the elimination of cancer/precancer cells prophylactically through increased immunosurveillance could be a viable option for cancer prevention.

Probably the greatest limitation to innovating cancer immunoprevention strategies is knowing which tumor antigens one should target, as there is no way to predict a priori who will get cancer, when, what type of cancer they will acquire, and which mutations it will harbor. However, with the revolution in cancer genetics over the past decade, catalyzed by next generation tumor sequencing, we currently have a wealth of common target mutations. Moreover, the likelihood of developing cancer in one’s lifetime is 1:2 in males and 1:3 in females (10), nearly as high as acquiring a prevalent pathogen like CMV. Therefore, it isn’t unreasonable to consider cancer vaccines in much the same way we do childhood vaccines for pathogens. To extend the analogy, while unaware of when and which pathogen a child will encounter, the likelihood that they will encounter it is exceedingly high; hence, we vaccinate against various pathogens early on in life, protecting against them with specific memory T and B cells. Likewise, the breadth of cancer predisposing events is vast; however, we are arguably entering an era in which we can consider prophylactically addressing these common features prospectively.

Cellular immunotherapies, such as dendritic cell (DC) (11, 12), tumor infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL), and chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) therapies (13), have emerged as treatment strategies for a range of cancer types. Simultaneously, our understanding of memory T cells and their various types has increased. Memory T cells could serve as potential candidates for novel forms of cancer immunoprevention due to their extended lifespans as well as their rapid and robust responses (14). As memory T cells are functionally diverse, certain subtypes possess characteristics that could be preferable over others for the prevention of cancer. Through determining which subtypes have good memory, versatility of location, diverse methods of reactivation, and strong correlations/causations with potent antitumor responses, this review article seeks to discuss the subtypes of currently recognized memory T cells in the prevention and protection against cancer. Though discussed briefly below, the types of potential cancer vaccines have been reviewed elsewhere (15, 16).

Methods of Cancer immunoprevention:

Preventive Cancer Vaccination

Except for the few highly effective prophylactic vaccines against virally induced cancers caused by HPV and HBV, most attempts to vaccinate against non-virally induced cancers remain experimental, and are used therapeutically, after cancer diagnosis and mostly after metastasis. However, the advance in knowledge of common cancer oncogenes and inherent risk based on demographics, coupled with the identification of T cells that can recognize oncogenic mutations, makes the idea of prophylactic cancer vaccines more viable.

The possibility of prevention is often sidelined due to the perceived lack of, or perhaps surplus of targets; there being a great diversity of cancer types one could develop, and an even greater variety of antigens displayed on those cancer cells. However, there are established common mutations or neoantigens that could be vaccinated against, like KRAS G12V/G12D, BRAF V600E, IDH1 132H, etc. (17). Numerous feasible vaccination types exist to expose our immune systems to such antigens, including mRNA, viral vector, long peptide, or DNA vaccines (18). One could even ensure local immunity through prime and pull methods, where memory T cells are induced through vaccination, then pulled into tissues commonly associated with developing cancer (19).

In the pursuit of therapy, one should also take into consideration the role of bystander memory T cells (identified by a lack of CD39) (20). While not targeting tumor antigens, these cells can make “cold” tumors “hot” again following reactivation by inflammatory cytokines (21–23). Bystander T cells that have been reactivated multiple (2 to 4) times, are more sensitive to inflammatory cytokines, and hence can reactivate as prolifically as antigen-induced memory T cells (23). Likely, these bystander memory T cells could be useful in cancer prevention, especially for tumors that may have lost expression of tumor antigens, by recruiting other types of immune cells that have tumoricidal properties like macrophages and NK cells.

Preventive T-cell therapy

An alternative paradigm that has yet to receive significant consideration is that of preventive T-cell therapy (PTCT), the autologous/allogeneic administration of genetically modified T cells that recognize common tumor antigens for cancer prevention (i.e., seeding the host with an increased number of memory T cells prior to cancer onset). The principal reason for therapeutically administering genetically modified T cells is to provide patients with effector and memory T cells that can recognize tumor antigens known to be expressed by the malignant cancer cells (e.g., CD19 on B cell lymphoma) already present in the host. In contrast, the rationale for prophylactically administering cellular therapy would be to provide the cancer patients of the future with memory T cells that recognize common tumor antigens that they may begin to be expressed in cells as they become malignant. Such antigens may include common mutations (TP53, PIK3CA, RAS family), or tumor-associated antigens (typically unmutated) (e.g., cancer-testis antigens or oncofetal antigens). Preventive T-cell therapies have not been considered, partly due to the fact that it would be difficult to predict the actual epitope that could be expressed in a patient’s future tumor and fear of transferring self-reactive T cells. Additional concerns are exorbitant costs, and the need for autologous approaches to ensure human leukocyte antigen (HLA) matching for graft-versus-host disease avoidance (24). Some ways to overcome these hurdles include matching of patient HLAs with donor T cells or through the replacement of α/β TCRs with non-specific γ/δ, or HLA-independent TCRs (25–29). Alternatively, CAR T cells could be affordably generated in vivo (30–34). Given the long-lived nature of transferred T cells, it would also be important to have mechanisms to temporarily, or permanently turn off functionality to avoid any unnecessary toxicity. Indeed, self-destruct and on/off CARs are already in development (Figure 1) (35, 36).

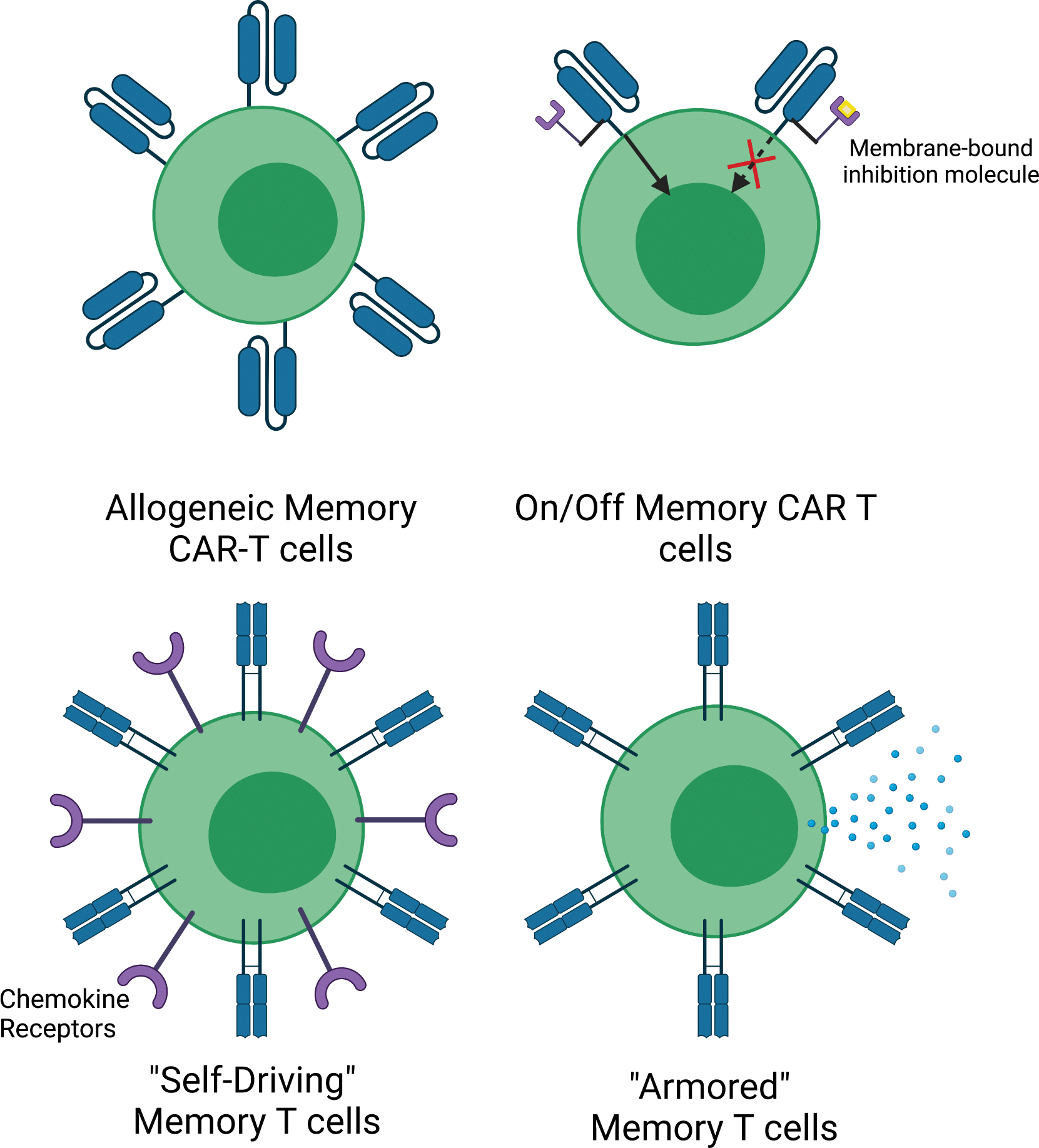

Figure 1: Various potential memory T cell modifications to enhance antitumor efficacy.

From top left to bottom right: Allogeneic memory CAR T cells, which do not cause GVHD due to the ablation of certain HLA and TCR types (25, 197), On/Off Memory CAR T cells, which can be inactivated/activated based on encounter with a small molecule (35, 36), “Self-Driving” CAR memory T cells, which have been modified to express certain chemokine receptors (198), and “Armored” Memory T cell are more resistant to immunosuppression because they have been engineered to lack PD-1 and express cytokines or proteins that boost anti-tumor immunity, e.g., IL-2, CD40L, 4–1BBL (199, 200).

Preventive T-cell therapy could fill a niche that vaccination cannot, with the ability to embed primed, anti-cancer TCRs or CARs intraepithelially at a high density for sustained immunosurveillance. Moreover, the cellular therapeutics could be engineered for certain traits (e.g., immunosuppression resistance), and the propensity to target non-immunogenic/non-MHC restricted cancer antigens. Importantly, the cellular approach could be used in tandem with cancer vaccination strategies to provide a holistic cancer prevention strategy (37, 38).

Anti-tumor memory T cells:

Around 20 years ago, two distinct subtypes of memory T cell were identified, CCR7− CD62L−, or CCR7+ CD62L+ cells, subsequently named the effector memory T cell (TEM), and the central memory T cell (TCM) respectively. The TEM primarily circulate within the blood, whereas the TCM can reside in lymph nodes and circulate the periphery (39). Since the original paper, several other subtypes of memory T cells, identified by function, phenotype, and location were discovered, including the stem memory T cell (TSCM), the tissue-resident memory T cell (TRM), and others (14, 40). Below are the defining phenotypical and functional characteristics of such cells, and their efficacies against cancer; critical when optimizing for the best form of cancer immunoprevention.

Central and Effector memory T cells

The central memory T cell (TCM) can be identified through its high expression of CCR7 and CD62L, which allows it to circulate and reside within lymph nodes, home to secondary lymphoid organs, and cross high endothelial venules (41). These cells produce high IL-2 but lower levels of effector cytokines (42), and as a result, tend to persist and proliferate greatly in response to antigen stimulation; albeit at the cost of low immediate effector capacity (43). Effector memory T cells (TEM) typically express no, or less CCR7/CD62L compared to TCM (39). In general, TEM circulate in the blood, and possess high immediate effector capacity (Perforin, IFN-γ, IL-5, and IL-4) (42).

TEM are the most common memory T cells in various cancers, including breast and melanoma (44–47). There is a positive correlation between TEM frequencies and survival in advanced melanoma patients receiving ipilimumab treatment. Those with high TEM frequencies (>30%) had a median overall survival (OS) of 80 weeks, compared to 34 weeks in those with low TEM frequencies (48). However, likely due to their regenerative potential of secondary effector cells, TCM have more potent and proliferative responses against several murine tumor models than TEM (49–51). TCM are more effective against tumors and have longer persistence in the spleen, bone marrow (BM), and blood than TEM, which had tumor progression rates analogous to control mice (52). After adoptive T cell treatment in murine models, donor cells with higher percentages of TEM correlated with lower rates of both therapeutic efficacy and T cell expansion (53, 54). Overall, while TEM are prevalent in varying cancer types, these cells have mixed results in terms of impact on tumor growth, and it appears that TCM are appreciably more effective at combating tumors.

Tissue-resident memory T cells

Many tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM) stably express CD69 (55,56), which enhances tissue retention, and CD103 (55,57), which alongside CD49a, is believed to help with tissue adherence and surveillance (55–57). Expressing these proteins allows TRM to reside in and patrol intraepithelial spaces, acting as the niche-specific first responders to pathogens (58–61). TRM have been identified in almost every single tissue examined (59, 62–69). In their respective niches, TRM require different cytokines and chemokines to thrive, contributing to their tissue-specific functions (69). For example, 4–1BB and CXCR3 in the lungs, CXCR6 and CCR10 in the skin, and CCL28/CCL25 in the gut (59, 70–77).

The phenotypic characteristics of TRM render them extremely promising candidates for immunosurveillance within niche tissues, with the unique potential to address tissue-specific cancers (78). Indeed, TRM show great promise in fending off tumor growth, with immunosurveillance showing significant correlations with prolonged disease-free-survival, relapse-free survival, and overall survival in a broad range of solid tumors (37, 44, 47, 56, 79–96). (59,87,98). Additionally, TRM have been shown to amplify existing circulating memory T cells responses (97). Overall, TRM have enormous potential as tissue-specific immunosurveillers of cancers.

Stem memory T cells

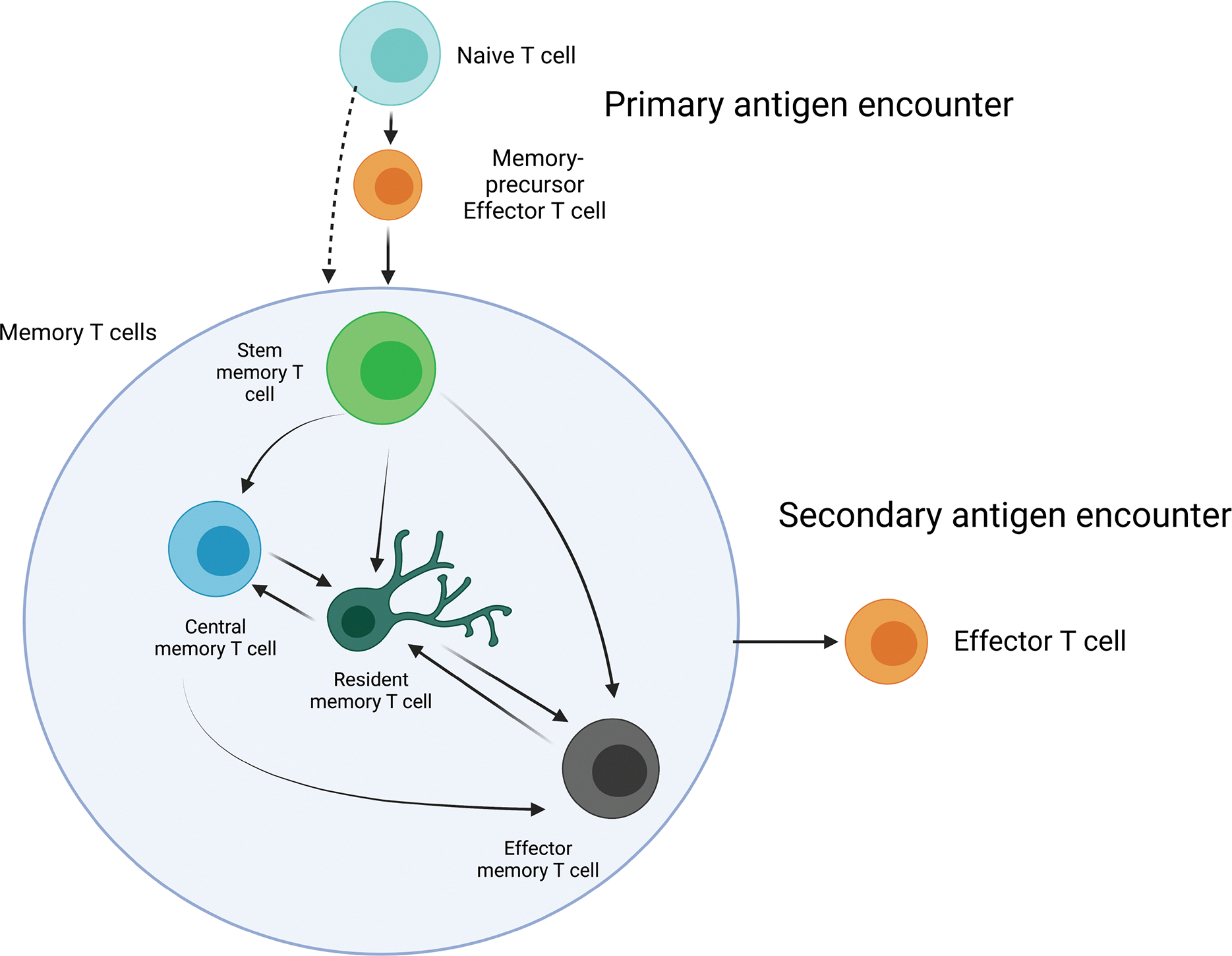

Stem memory T cells (TSCM) are CD45RO-/CD45RA+, and CD95+, yet CD31−, differentiating themselves from TCM and naive T cells (TN). Compared to TN and TCM, the TSCM subset diverges in the expression of genes associated with functional differentiation, categorizing them as “highest stemness” antigen-experienced T cell (Figure 2) (98). TSCM are found in blood and lymph nodes, potentially reactivating more effectively in lymph nodes, as they express CCR7 and CD62L (98, 99).

Figure 2: Plasticity in phenotype and function.

Memory T cells aren’t restricted to one phenotype from the moment they differentiate post initial antigen encounter. Subtypes could be looked at like states of differentiation, with the order of differentiation, from least to greatest being TSCM, then TCM, then TEM. Phenotypes can be fluid, differentiating based on cytokine encounters. For example, TSCM has a bias towards becoming TCM, TEM, or TRM, (98, 201). TCM has the capability of turning into TRM or TEM (97, 202, 203). TRM can turn into TCM and TEM, being able to reconstitute blood memory as TEM, with TEM being capable of morphing into TRM as well (112, 114, 121, 177, 203). This paints a very interesting picture, with memory T cells morphing in phenotype when the time arises, not necessarily restricted to one subtype or another. The induction of highly differentiated cells may not be the most ideal for cancer immunoprevention, as it has been detailed that patients with a mainly TEM phenotype of CAR T cell 30 days post-treatment had their CAR presence disappear 2–4 months after, whereas greater endurance was acquired in factions with high TSCM and TCM presence during transplantation (106).

TSCM have superior antitumor responses, greater proliferative capabilities, more tumor infiltration, and mediate longer sustained tumor regression upon transfer than naïve T cells, TCM, and TEM; with differentiation status inversely correlating with antitumor capability (54, 98, 100). TSCM expand at rates 10 times greater than TCM, and 30 times more than TEM post-transfer, with TSCM exhibiting superior survival and antitumor activity (101). Robust effector cell responses were also correlated with the expansion of TSCM in melanoma patients, potentially resulting from TSCM differentiation into effector-type cells (102). CAR-T cell lines with high TSCM frequencies also have a greater proliferative capacity (53, 103), and more effectively eliminate leukemia cells, initiating long-lasting antitumor effects with greater survival (104, 105). Finally, in patients treated with CAR-T, those with greater TSCM and TCM preservation had long-term CAR persistence. More than 2 years after CAR treatments, the contribution of TSCM to the clonal pool in these patients was 60.5%, expanding from initial frequencies of only ~1–2% (106).

Optimal memory T cell characteristics for cancer immunoprevention:

Several considerations arise when evaluating candidate memory T cells for cancer prevention. These factors being: their longevity, plasticity of phenotype, proliferative capacity, methods of reactivation, and whether the goal is to implement localized or global protection against cancers. Arguably, the cell that excels in these factors should be considered most ideal for cancer prevention.

Clonal longevity

The consideration of clonal longevity is extremely important when it comes to cancer immunoprevention design, as one would want to create the longest-lasting immunity for the prevention of a disease that has either yet to happen or will likely reoccur. On an individual basis, most memory T cells are not long-lived. Instead, the memory of a specific antigen is passed down through the process of homeostatic proliferation. Thus, the longevity of an antigen-specific clonal “tribe” is likely more important than that of each memory cell (107).

The lifespan of memory T cells is determined by cytokine interactions (e.g., IL-15 and IL-7), their differentiation state (i.e., memory cell subtype), and the number/type of antigens it encounters over its life. In individuals vaccinated against smallpox, virus-specific T cells can last for decades, decreasing with a half-life of 8–15 years (108). In a more subtype focused study, tumor-associated TEM and TRM clones in patients who had melanoma persisted for 6 to 9 years in the blood and skin (109). TRM display exceptional clonal longevity, surviving long term in the intestinal mucosa (>1 year) (110), the brain (>120 days) (111), transplanted livers (>11 years prior) (112), and the skin (10 years post hematopoietic stem cell transplantation) (113). Mechanisms contributing to TRM persistence seem to vary by tissue type and the ability to be replenished by circulating T cells (lungs, kidneys, and liver) (112, 114). Moreover, TRM have long-lived memory in some tissues, in contrast to shorter memories in other tissues (like the lung, >15 months allograft) (115–119). A quiescent, slow cycling TRM subtype has also been described, hence such TRM may have longer individual lifespans due to lower metabolic demands over time (120, 121). TSCM, and some TCM derived from genetically altered hematopoietic cells were able to maintain their “stemness” and persist for up to 9–12 years (122, 123). Two kinetically heterogeneous subsets of TSCM have been reported, one long-lived and one relatively short-lived, with modelled half-lives of 9 years and 5 months (5.8% and 94.2% of the population) respectively (124). Finally, yellow-fever virus specific TSCM-like cells were identified in individuals who received the yellow fever vaccine more than 25 years ago, while still being functionally competent ex vivo (125).

Since cells that can convey the longest immunity against cancer are the most ideal for immunoprevention, current evidence indicates that In TSCM and TCM might have the advantage over more differentiated subtypes. However, the longevity of TRM should not be under appreciated and more work needs to be done to determine their lifespan in tissues in humans.

Methods of reactivation

APCs and CD28 are vital for the strong response of certain memory cells, whereas others are more promiscuous in mechanisms of reactivation. Depending on the mode of reactivation, the intensity and rapidity of responses differ. In the context of cancer, it is important to have multiple methods of reactivation, as cancer cells deter the attraction of DCs through PGE2, and have extremely low, if any CD28 expression (126, 127).

There is substantial evidence supporting the reliance of TCM on professional APCs for reactivation; seeing as the deletion of DCs impaired TCM reactivation significantly (~90%), leading to a failure in protection against virus challenge (128, 129). In contrast, CD62L− TEM reactivation was impacted, but not as severely as TCM cells, when DCs were depleted. This suggests that TCM have more reliance on DCs than TEM (129). Although fewer studies are available for TSCM, considering their transcriptional similarity with TCM and TN, which are exclusively reliant on professional APCs for reactivation, TSCM reactivation likely depends on conventional DCs (cDCs). This probably stems from the preferred localization of TCM and TSCM in T cell zones of secondary lymphoid organs (129, 130).

Reactivation of TRM differ from circulating memory T cells since the former can be activated by both professional APCs and infected cells with rapid kinetics (131–134). Notably, murine lung TRM reactivation following influenza or LCMV re-infection was largely unaffected by DC depletion (139)Further, non-hematopoietic cells were sufficient to reactivate lung TRM cells in influenza reinfection, showing that lung TRM cells can acquire antigen from both immune and non-immune cells (139)TRM also elicit anti-viral states in tissues locally by activating DCs and NK cells, while also increasing B and T cell infiltration (131), demonstrating the key role for TRM in amplifying and broadening antitumor responses in tissues (135).

Of the cells described in this section, TRM are stand outs with regard to intraepithelial immunosurveillance and immediate response, especially because they also can be reactivated directly by cancer cells themselves. Considering that most cancers start and occur within tissues, and that many cancers have mechanisms of deterring APCs (the deterrence of DCs via PGE2) (126), active cancer immunosurveillance by TRM with their diverse methods of reactivation could prove advantageous.

Putting cancer immunoprevention into practice:

To deploy cancer immunoprevention, certain techniques might benefit memory T cell preservation and efficacy. Additionally, one of the most vital elements to consider is the antigen that the therapy targets. Certain antigens may work well with vaccination, whereas other atypical antigens may be better for cell therapy. Taking this idea to the clinic will require an understanding of potential target antigens, and the methods of phenotypic induction for each of the memory T cell subtypes.

Types of antigens for cancer immunoprevention

Many cancers share mutations in the same genes that have key roles in suppressing the division of cells with damaged DNA (tumor suppressors), expedite the rate at which cells grow (oncogenes), or hitchhike alongside these driver mutations (passengers). Proteins synthesized from the mutated genes are often broken down and presented on the surface of MHC class 1 molecules. Some examples include mutated TP53, which is present in more than 50% of cancers, and the “undruggable” RAS, which is mutated in >30% of cancers; both of which are subject to targeting via CARs and TCRs in clinical trials (136–142). In addition, there are premalignant mutations, such as the mutant adenomatous polyposis coli gene in colorectal cancers, targeting of which could halt tumor progression at a precancerous stage (143–145). Senescent cell elimination via CAR-T cells could be an alternative approach to the prevention of cancer, as uPAR specific CAR-T cells prolong survival in mice with lung adenocarcinomas (146). Another category of targets could be cancer/testis (CT) antigens like MAGEA, NY-ESO-1, SSX2, CT83, and PRAME, due to their prevalence on early cancers, and differential expression on cancer and germline cells (147–153).

Recently, a TCR clone MC.7.G5 was identified capable of eliminating multiple cancer types (e.g., melanoma, colon, leukemia, breast, prostate, ovarian, bone, and lung cancer cells) without a common MHC peptide. Importantly, this TCR clonotype did not react with non-cancerous cells. Interestingly, CRISPR screening identified that MC.7.G5 is restricted by the monomorphic MHC I-like protein MR1, yet the MR1 ligands that MC.7.G5 recognizes to differentiate between cancerous vs non-cancerous cells are still unknown (28). This was not the first time that targeting MR1 was shown to be effective against many cancers (154). Thus, targeting MR1 and other pan-cancer molecules using preventive adoptive therapy could be HLA-agnostic, off the shelf, long-lived, and tissue specific.

Inducing various phenotypes for cancer immunoprevention

To create ideal populations of cells for the prevention of cancer, certain long-lived tumor infiltrating phenotypes should be induced in memory T cells. One could do so by engineering these cells with traits found in TRM (tissue residence and tumor infiltration) and TSCM (proliferative capacity and multipotency to generate effector cells).

Enhancing tissue residence and tumor infiltration

The method of vaccine administration heavily influences the phenotype of cells that one inducts, with the route of induction or transfusion also dictating tissue residency. Intranasal routes, for example, have been effective in inducing TRM populations not only in pulmonary tissues, but also in the reproductive tract (155–167). Intramuscular, intravenous, and subcutaneous approaches can induce TRM in tissues varying from the lungs to the liver, skin, and others (16, 64, 168–170). Using certain antibody, cytokine, nucleic acid, and small molecule adjuvants can increase TRM numbers through DC recruitment, the activation of epithelial cells, and TRM imprinting (64, 162, 164, 166, 171–176).

Location of cell residency is not necessarily set in stone. In skin, TRM are capable of dispersing from the area of initial antigen encounter to other non-infected areas of skin, providing global skin immunity, and forming in the tumor-distant mucosa post vaccination (69, 177, 178). Although TRM localization typically happens near the point of infection, the cells can be directed via a prime and pull/trap method, whereby TRM are activated and then compelled to a certain region via an agent such as a chemokine, cognate antigen, or topical inflammatory drug (64, 167, 179–186). Directing immunity to specific tissues could be possible using “self-driving CARs”, which direct memory T cells to basal chemokines in specific tissues, such as the skin via CCR10, or the intestines via CCR9 (Figure 1) (187–189).

Enhancing proliferative capacity, longevity and multipotency

Methods of TSCM induction via vaccination have not been well defined. Following both yellow-fever (125) and lentiviral vaccination against HCC, TSCM were induced (190). Methods for inducing TSCM ex-vivo; however, are well known, and include the use of certain cytokines like IL-7, IL-21, but most significantly, IL-15, which induces a TSCM-like CCR7+ CD45RA+ phenotype that provides greater antitumor responses and enhanced self-renewal (100, 103, 104, 191, 192). Typically, naive T cells are the starting source for TSCM, but alternative approaches have emerged, where TEM or TCM are induced into an “iTSCM” phenotype via DLL1-expressing OP9 stromal cells alongside IL-7 (101, 193, 194). Another important consideration when triggering a TSCM phenotype is the Wnt/β-catenin pathway; GSK-3ß inhibitors and Wnt3a have been shown to induce naive T cells into a TSCM phenotype through the signaling of this pathway (98, 101).

Conclusions:

Immunoprevention could benefit at least four groups of individuals: [1] those with cancer who have gone into remission but are wary that malignancy will return, [2] those with an early detection of cancer, [3] those genetically predisposed to cancers in certain tissues, and [4] those without any malignancy or predisposal whatsoever.

For individuals in remission, memory T cells could either target prominent antigens/neoantigens present on their previous cancer, or possess a TCR from effective TILs. These memory T cells could either be tissue-specific or circulating globally in search of metastases. Those who undergo early detection, potentially via liquid biopsy, could benefit from a less invasive prevention strategy employing memory T cells specific for antigens predicted by circulating DNA (195). For the third group, TRM could be transferred into tissues that have a genetic or hereditary predisposition to cancer, like the breast in those with a BRCA family mutation. The target antigen should be present in the cancers one prevents; for instance, those with BRCA1 mutations typically have triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Hence, an exemplative preventive antigen target could be α-lactalbumin, which is genetically overexpressed in ~70% of all TNBCs (152). The final group consists of those otherwise healthy, who lack a genetic predisposition to cancer. Applying immunoprevention to this category of individuals could be difficult, as uncertainty arises when determining what to target. Risk-benefit analysis would be especially important for this group, considering the lack of immediate medical need. This fourth group could utilize long-lived circulating TSCM against targets that aren’t restricted to one type of cancer, like MR1 and those listed in the section above.

While there are several challenges to cancer immunoprevention, like the vast landscape of tumor antigens, the need to target enough antigens to prevent tumor escape, and the potential for autoimmune responses when targeting certain antigens (196), these are all currently being tackled. Strategies such as identifying shared antigens, using combination therapies, utilizing precision medicine approaches, and conducting preclinical studies all show promise, moving the potential of cancer immunoprevention closer to reality.

Memory T cells are critical for maintaining immunity against both pathogens and cancers. Over the last two decades, the discovery of memory T cell subtypes differing in function and phenotype, has elucidated key players in memory retention. This review sought to identify the ideal memory T cell subtype for cancer prevention using the criteria of clonal longevity, location, residence, activation requirements, and efficacy in cancer response. Tissue-resident memory T cells could act as the niche protectors of specific tissues, for example, if one is genetically predisposed to colorectal or breast cancer. Increasing the density of TRM specific for those cancers in said regions could provide local immunity before a tumor can take hold. In tandem, a less differentiated memory T cell, such as the stem memory T cell, could act as a circulating bastion of cancer-fighting cells, providing whole-body immunity to cancer, potentially even targeting antigens that are not conventionally immunized against, and universally present, like MR1. Through the utilization of memory T cell subtypes that confer long-lived, intraepithelial, or whole-body immunity, one could enact robust and precise protection against a range of cancers.

Funding:

R01 AI066232

References:

- 1.Etzioni R, Urban N, Ramsey S, McIntosh M, Schwartz S, Reid B, Radich J, Anderson G, and Hartwell L. 2003. The case for early detection. Nature Reviews Cancer 2003 3:4 3: 243–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lei J, Ploner A, Elfström KM, Wang J, Roth A, Fang F, Sundström K, Dillner J, and Sparén P. 2020. HPV Vaccination and the Risk of Invasive Cervical Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 383: 1340–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang MH 2010. Hepatitis B Virus and Cancer Prevention. Recent Results in Cancer Research 188: 75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bray F, and Møller B. 2005. Predicting the future burden of cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 2006 6:1 6: 63–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogelstein B, and Kinzler KW. 2004. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nature Medicine 2004 10:8 10: 789–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bian Y, Li W, Kremer DM, Sajjakulnukit P, Li S, Crespo J, Nwosu ZC, Zhang L, Czerwonka A, Pawłowska A, Xia H, Li J, Liao P, Yu J, Vatan L, Szeliga W, Wei S, Grove S, Liu JR, McLean K, Cieslik M, Chinnaiyan AM, Zgodziński W, Wallner G, Wertel I, Okła K, Kryczek I, Lyssiotis CA, and Zou W. 2020. Cancer SLC43A2 alters T cell methionine metabolism and histone methylation. Nature 2020 585:7824 585: 277–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salvatore V, Teti G, Focaroli S, Mazzotti MC, Mazzotti A, Falconi M, Salvatore V, Teti G, Focaroli S, Carla Mazzotti M, Mazzotti A, and Falconi M. 2016. The tumor microenvironment promotes cancer progression and cell migration. Oncotarget 8: 9608–9616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Togashi Y, Shitara K, and Nishikawa H. 2019. Regulatory T cells in cancer immunosuppression — implications for anticancer therapy. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2019 16:6 16: 356–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Donnell JS, Teng MWL, and Smyth MJ. 2018. Cancer immunoediting and resistance to T cell-based immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2018 16:3 16: 151–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis D, Chen H, Feuer E, and K. (eds) Cronin. 2021. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2018 based on November 2020 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER website. National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santos PM, and Butterfield LH. 2018. Dendritic Cell–Based Cancer Vaccines. The Journal of Immunology 200: 443–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar A, Watkins R, and Vilgelm AE. 2021. Cell Therapy With TILs: Training and Taming T Cells to Fight Cancer. Front Immunol 12: 1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.June CH, O’Connor RS, Kawalekar OU, Ghassemi S, and Milone MC. 2018. CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science (1979) 359: 1361–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jameson SC, and Masopust D. 2018. Understanding Subset Diversity in T Cell Memory. Immunity 48: 214–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finn OJ 2018. The dawn of vaccines for cancer prevention. Nat Rev Immunol 18: 183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knight FC, and Wilson JT. 2021. Engineering Vaccines for Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells. Adv Ther (Weinh) 4: 2000230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grossman RL, Heath AP, Ferretti V, Varmus HE, Lowy DR, Kibbe WA, and Staudt LM. 2016. Toward a Shared Vision for Cancer Genomic Data. New England Journal of Medicine 375: 1109–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saxena M, van der Burg SH, Melief CJM, and Bhardwaj N. 2021. Therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nature Reviews Cancer 2021 21:6 21: 360–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernstein DI, Cardin RD, Bravo FJ, Awasthi S, Lu P, Pullum DA, Dixon DA, Iwasaki A, and Friedman HM. 2019. Successful application of prime and pull strategy for a therapeutic HSV vaccine. npj Vaccines 2019 4:1 4: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simoni Y, Becht E, Fehlings M, Loh CY, Koo SL, Teng KWW, Yeong JPS, Nahar R, Zhang T, Kared H, Duan K, Ang N, Poidinger M, Lee YY, Larbi A, Khng AJ, Tan E, Fu C, Mathew R, Teo M, Lim WT, Toh CK, Ong BH, Koh T, Hillmer AM, Takano A, Lim TKH, Tan EH, Zhai W, Tan DSW, Tan IB, and Newell EW. 2018. Bystander CD8+ T cells are abundant and phenotypically distinct in human tumour infiltrates. Nature 557: 575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosato PC, Wijeyesinghe S, Stolley JM, Nelson CE, Davis RL, Manlove LS, Pennell CA, Blazar BR, Chen CC, Geller MA, Vezys V, and Masopust D. 2019. Virus-specific memory T cells populate tumors and can be repurposed for tumor immunotherapy. Nat Commun 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erkes DA, Smith CJ, Wilski NA, Caldeira-Dantas S, Mohgbeli T, and Snyder CM. 2017. Virus-Specific CD8+ T Cells Infiltrate Melanoma Lesions and Retain Function Independently of PD-1 Expression. The Journal of Immunology 198: 2979–2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danahy DB, Berton RR, and Badovinac VP. 2020. Cutting Edge: Antitumor Immunity by Pathogen-Specific CD8 T Cells in the Absence of Cognate Antigen Recognition. The Journal of Immunology 204: 1431–1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiorenza S, Ritchie DS, Ramsey SD, Turtle CJ, and Roth JA. 2020. Value and affordability of CAR T-cell therapy in the United States. Bone Marrow Transplantation 2020 55:9 55: 1706–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kagoya Y, Guo T, Yeung B, Saso K, Anczurowski M, Wang CH, Murata K, Sugata K, Saijo H, Matsunaga Y, Ohashi Y, Butler MO, and Hirano N. 2020. Genetic Ablation of HLA Class I, Class II, and the T-cell Receptor Enables Allogeneic T Cells to Be Used for Adoptive T-cell Therapy. Cancer Immunol Res 8: 926–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garber K 2020. γδ T cells bring unconventional cancer-targeting to the clinic - again. Nat Biotechnol 38: 389–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fisher J, and Anderson J. 2018. Engineering approaches in human gamma Delta T cells for cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol 9: 1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crowther MD, Dolton G, Legut M, Caillaud ME, Lloyd A, Attaf M, Galloway SAE, Rius C, Farrell CP, Szomolay B, Ager A, Parker AL, Fuller A, Donia M, McCluskey J, Rossjohn J, Svane IM, Phillips JD, and Sewell AK. 2020. Genome-wide CRISPR–Cas9 screening reveals ubiquitous T cell cancer targeting via the monomorphic MHC class I-related protein MR1. Nature Immunology 2020 21:2 21: 178–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mansilla-Soto J, Eyquem J, Haubner S, Hamieh M, Feucht J, Paillon N, Zucchetti AE, Li Z, Sjöstrand M, Lindenbergh PL, Saetersmoen M, Dobrin A, Maurin M, Iyer A, Garcia Angus A, Miele MM, Zhao Z, Giavridis T, van der Stegen SJC, Tamzalit F, Rivière I, Huse M, Hendrickson RC, Hivroz C, and Sadelain M. 2022. HLA-independent T cell receptors for targeting tumors with low antigen density. Nature Medicine 2022 28:2 28: 345–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agarwal S, Weidner T, Thalheimer FB, and Buchholz CJ. 2019. In vivo generated human CAR T cells eradicate tumor cells. Oncoimmunology 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurup SP, Moioffer SJ, Pewe LL, and Harty JT. 2020. p53 Hinders CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Targeted Gene Disruption in Memory CD8 T Cells In Vivo. The Journal of Immunology 205: 2222–2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nawaz W, Huang B, Xu S, Li Y, Zhu L, Yiqiao H, Wu Z, and Wu X. 2021. AAV-mediated in vivo CAR gene therapy for targeting human T-cell leukemia. Blood Cancer Journal 2021 11:6 11: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfeiffer A, Thalheimer FB, Hartmann S, Frank AM, Bender RR, Danisch S, Costa C, Wels WS, Modlich U, Stripecke R, Verhoeyen E, and Buchholz CJ. 2018. In vivo generation of human CD19-CAR T cells results in B-cell depletion and signs of cytokine release syndrome. EMBO Mol Med 10: e9158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rurik JG, Tombácz I, Yadegari A, Méndez Fernández PO, v Shewale S, Li L, Kimura T, Soliman OY, Papp TE, Tam YK, Mui BL, Albelda SM, Puré E, June CH, Aghajanian H, Weissman D, Parhiz H, and Epstein JA. 2022. CAR T cells produced in vivo to treat cardiac injury. Science 375: 91–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jan M, Scarfò I, Larson RC, Walker A, Schmidts A, Guirguis AA, Gasser JA, Słabicki M, Bouffard AA, Castano AP, Kann MC, Cabral ML, Tepper A, Grinshpun DE, Sperling AS, Kyung T, Sievers QL, Birnbaum ME, Maus MV, and Ebert BL. 2021. Reversible ON- And OFF-switch chimeric antigen receptors controlled by lenalidomide. Sci Transl Med 13: 6295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giordano-Attianese G, Gainza P, Gray-Gaillard E, Cribioli E, Shui S, Kim S, Kwak MJ, Vollers S, Corria Osorio ADJ, Reichenbach P, Bonet J, Oh BH, Irving M, Coukos G, and Correia BE. 2020. A computationally designed chimeric antigen receptor provides a small-molecule safety switch for T-cell therapy. Nature Biotechnology 2020 38:4 38: 426–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nizard M, Roussel H, Diniz MO, Karaki S, Tran T, Voron T, Dransart E, Sandoval F, Riquet M, Rance B, Marcheteau E, Fabre E, Mandavit M, Terme M, Blanc C, Escudie JB, Gibault L, Barthes FLP, Granier C, Ferreira LCS, Badoual C, Johannes L, and Tartour E. 2017. Induction of resident memory T cells enhances the efficacy of cancer vaccine. Nature Communications 2017 8:1 8: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumai T, Kobayashi H, Harabuchi Y, and Celis E. 2017. Peptide vaccines in cancer — old concept revisited. Curr Opin Immunol 45: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Förster R, Lipp M, and Lanzavecchia A. 1999. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature 1999 401:6754 401: 708–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu G, and Wang S. 2017. Tumor-infiltrating CD45RO+ Memory T Lymphocytes Predict Favorable Clinical Outcome in Solid Tumors. Scientific Reports 2017 7:1 7: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Förster R, Schubel A, Breitfeld D, Kremmer E, Renner-Müller I, Wolf E, and Lipp M. 1999. CCR7 Coordinates the Primary Immune Response by Establishing Functional Microenvironments in Secondary Lymphoid Organs. Cell 99: 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sallusto F, Geginat J, and Lanzavecchia A. 2004. CENTRAL MEMORY AND EFFECTOR MEMORY T CELL SUBSETS: Function, Generation, and Maintenance. Annu. Rev. Immunol 22: 745–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wherry EJ, Teichgräber V, Becker TC, Masopust D, Kaech SM, Antia R, von Andrian UH, and Ahmed R. 2003. Lineage relationship and protective immunity of memory CD8 T cell subsets. Nature Immunology 2003 4:3 4: 225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Savas P, Virassamy B, Ye C, Salim A, Mintoff CP, Caramia F, Salgado R, Byrne DJ, Teo ZL, Dushyanthen S, Byrne A, Wein L, Luen SJ, Poliness C, Nightingale SS, Skandarajah AS, Gyorki DE, Thornton CM, Beavis PA, Fox SB, Darcy PK, Speed TP, MacKay LK, Neeson PJ, and Loi S. 2018. Single-cell profiling of breast cancer T cells reveals a tissue-resident memory subset associated with improved prognosis. Nature Medicine 2018 24:7 24: 986–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murray T, Marraco SAF, Baumgaertner P, Bordry N, Cagnon L, Donda A, Romero P, Verdeil G, and Speiser DE. 2016. Very late antigen-1 marks functional tumor-resident CD8 T cells and correlates with survival of melanoma patients. Front Immunol 7: 573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pagès F, Berger A, Camus M, Sanchez-Cabo F, Costes A, Molidor R, Mlecnik B, Kirilovsky A, Nilsson M, Damotte D, Meatchi T, Bruneval P, Cugnenc P-H, Trajanoski Z, Fridman W-H, and Galon J. 2005. Effector Memory T Cells, Early Metastasis, and Survival in Colorectal Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 353: 2654–2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hartana CA, Ahlén Bergman E, Broomé A, Berglund S, Johansson M, Alamdari F, Jakubczyk T, Huge Y, Aljabery F, Palmqvist K, Holmström B, Glise H, Riklund K, Sherif A, and Winqvist O. 2018. Tissue-resident memory T cells are epigenetically cytotoxic with signs of exhaustion in human urinary bladder cancer. 194: 39–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Coaña YP, Wolodarski M, Poschke I, Yoshimoto Y, Yang Y, Nyström M, Edbäck U, Brage SE, Lundqvist A, G. v. Masucci, J. Hansson, and R. Kiessling. 2017. Ipilimumab treatment decreases monocytic MDSCs and increases CD8 effector memory T cells in long-term survivors with advanced melanoma. Oncotarget 8: 21539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berger C, Jensen MC, Lansdorp PM, Gough M, Elliott C, and Riddell SR. 2008. Adoptive transfer of effector CD8+ T cells derived from central memory cells establishes persistent T cell memory in primates. J Clin Invest 118: 294–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klebanoff CA, Finkelstein SE, Surman DR, Lichtman MK, Gattinoni L, Theoret MR, Grewal N, Spiess PJ, Antony PA, Palmer DC, Tagaya Y, Rosenberg SA, Waldmann TA, and Restifo NP. 2004. IL-15 enhances the in vivo antitumor activity of tumor-reactive CD8+ T Cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101: 1969–1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Torabi-Parizi P, Kerstann K, Cardones AR, Finkelstein SE, Palmer DC, Antony PA, Hwang ST, Rosenberg SA, Waldmann TA, and Restifo NP. 2005. Central memory self/tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells confer superior antitumor immunity compared with effector memory T cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102: 9571–9576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang X, Berger C, Wong CLW, Forman SJ, Riddell SR, and Jensen MC. 2011. Engraftment of human central memory-derived effector CD8+ T cells in immunodeficient mice. Blood 117: 1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arcangeli S, Falcone L, Camisa B, de Girardi F, Biondi M, Giglio F, Ciceri F, Bonini C, Bondanza A, and Casucci M. 2020. Next-Generation Manufacturing Protocols Enriching TSCM CAR T Cells Can Overcome Disease-Specific T Cell Defects in Cancer Patients. Front Immunol 11: 1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Palmer DC, Muranski P, Ji Y, Hinrichs CS, Borman ZA, Kerkar SP, Scott CD, Finkelstein SE, Rosenberg SA, and Restifo NP. 2011. Determinants of Successful CD8+ T-Cell Adoptive Immunotherapy for Large Established Tumors in Mice. Clinical Cancer Research 17: 5343–5352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mackay LK, Braun A, Macleod BL, Collins N, Tebartz C, Bedoui S, Carbone FR, and Gebhardt T. 2015. Cutting Edge: CD69 Interference with Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor Function Regulates Peripheral T Cell Retention. The Journal of Immunology 194: 2059–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reilly EC, Emo KL, Buckley PM, Reilly NS, Smith I, Chaves FA, Yang H, Oakes PW, and Topham DJ. 2020. TRM integrins CD103 and CD49a differentially support adherence and motility after resolution of influenza virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117: 12306–12314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bromley SK, Akbaba H, Mani V, Mora-Buch R, Chasse AY, Sama A, and Luster AD. 2020. CD49a Regulates Cutaneous Resident Memory CD8+ T Cell Persistence and Response. Cell Rep 32: 108085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kumar B. v., Ma W, Miron M, Granot T, Guyer RS, Carpenter DJ, Senda T, Sun X, Ho SH, Lerner H, Friedman AL, Shen Y, and Farber DL. 2017. Human Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells Are Defined by Core Transcriptional and Functional Signatures in Lymphoid and Mucosal Sites. Cell Rep 20: 2921–2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.MacKay LK, Rahimpour A, Ma JZ, Collins N, Stock AT, Hafon ML, Vega-Ramos J, Lauzurica P, Mueller SN, Stefanovic T, Tscharke DC, Heath WR, Inouye M, Carbone FR, and Gebhardt T. 2013. The developmental pathway for CD103+CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells of skin. Nature Immunology 2013 14:12 14: 1294–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ariotti S, Beltman JB, Chodaczek G, Hoekstra ME, van Beek AE, Gomez-Eerland R, Ritsma L, van Rheenen J, Marée AFM, Zal T, de Boer RJ, Haanen JBAG, and Schumacher TN. 2012. Tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells continuously patrol skin epithelia to quickly recognize local antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 19739–19744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takamura S, Kato S, Motozono C, Shimaoka T, Ueha S, Matsuo K, Miyauchi K, Masumoto T, Katsushima A, Nakayama T, Tomura M, Matsushima K, Kubo M, and Miyazawa M. 2019. Interstitial-resident memory CD8+ T cells sustain frontline epithelial memory in the lung. Journal of Experimental Medicine 216: 2736–2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hombrink P, Helbig C, Backer RA, Piet B, Oja AE, Stark R, Brasser G, Jongejan A, Jonkers RE, Nota B, Basak O, Clevers HC, Moerland PD, Amsen D, and van Lier RAW. 2016. Programs for the persistence, vigilance and control of human CD8+ lung-resident memory T cells. Nature Immunology 2016 17:12 17: 1467–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smolders J, Heutinck KM, Fransen NL, Remmerswaal EBM, Hombrink P, ten Berge IJM, van Lier RAW, Huitinga I, and Hamann J. 2018. Tissue-resident memory T cells populate the human brain. Nature Communications 2018 9:1 9: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fernandez-Ruiz D, Ng WY, Holz LE, Ma JZ, Zaid A, Wong YC, Lau LS, Mollard V, Cozijnsen A, Collins N, Li J, Davey GM, Kato Y, Devi S, Skandari R, Pauley M, Manton JH, Godfrey DI, Braun A, Tay SS, Tan PS, Bowen DG, Koch-Nolte F, Rissiek B, Carbone FR, Crabb BS, Lahoud M, Cockburn IA, Mueller SN, Bertolino P, McFadden GI, Caminschi I, and Heath WR. 2016. Liver-Resident Memory CD8+ T Cells Form a Front-Line Defense against Malaria Liver-Stage Infection. Immunity 45: 889–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Booth JS, Toapanta FR, Salerno-Goncalves R, Patil S, Kader HA, Safta AM, Czinn SJ, Greenwald BD, and Sztein MB. 2014. Characterization and functional properties of gastric tissue-resident memory T cells from children, adults, and the elderly. Front Immunol 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sathaliyawala T, Kubota M, Yudanin N, Turner D, Camp P, Thome JJC, Bickham KL, Lerner H, Goldstein M, Sykes M, Kato T, and Farber DL. 2013. Distribution and compartmentalization of human circulating and tissue-resident memory T cell subsets. Immunity 38: 187–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wong MT, Ong DEH, Lim FSH, Teng KWW, McGovern N, Narayanan S, Ho WQ, Cerny D, Tan HKK, Anicete R, Tan BK, Lim TKH, Chan CY, Cheow PC, Lee SY, Takano A, Tan EH, Tam JKC, Tan EY, Chan JKY, Fink K, Bertoletti A, Ginhoux F, Curotto de Lafaille MA, and Newell EW. 2016. A High-Dimensional Atlas of Human T Cell Diversity Reveals Tissue-Specific Trafficking and Cytokine Signatures. Immunity 45: 442–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Takamura S 2018. Niches for the long-term maintenance of tissue-resident memory T cells. Front Immunol 9: 1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Szabo PA, Miron M, and Farber DL. 2019. Location, location, location: Tissue resident memory T cells in mice and humans. Sci Immunol 4: 9673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhou AC, Wagar LE, Wortzman ME, and Watts TH. 2017. Intrinsic 4–1BB signals are indispensable for the establishment of an influenza-specific tissue-resident memory CD8 T-cell population in the lung. Mucosal Immunology 2017 10:5 10: 1294–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhou AC, Batista N. v., and Watts TH. 2019. 4–1BB Regulates Effector CD8 T Cell Accumulation in the Lung Tissue through a TRAF1-, mTOR-, and Antigen-Dependent Mechanism to Enhance Tissue-Resident Memory T Cell Formation during Respiratory Influenza Infection. The Journal of Immunology 202: 2482–2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Slütter B, Pewe LL, Kaech SM, and Harty JT. 2013. Lung Airway-Surveilling CXCR3hi Memory CD8+ T Cells Are Critical for Protection against Influenza A Virus. Immunity 39: 939–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gilchuk P, Hill TM, Guy C, McMaster SR, Boyd KL, Rabacal WA, Lu P, Shyr Y, Kohlmeier JE, Sebzda E, Green DR, and Joyce S. 2016. A Distinct Lung-Interstitium-Resident Memory CD8+ T Cell Subset Confers Enhanced Protection to Lower Respiratory Tract Infection. Cell Rep 16: 1800–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zaid A, Hor JL, Christo SN, Groom JR, Heath WR, Mackay LK, and Mueller SN. 2017. Chemokine Receptor–Dependent Control of Skin Tissue–Resident Memory T Cell Formation. The Journal of Immunology 199: 2451–2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Svensson M, Marsal J, Ericsson A, Carramolino L, Brodén T, Márquez G, and Agace WW. 2002. CCL25 mediates the localization of recently activated CD8αβ+ lymphocytes to the small-intestinal mucosa. J Clin Invest 110: 1113–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Campbell JJ, Haraldsen G, Pan J, Rottman J, Qin S, Ponath P, Andrew DP, Warnke R, Ruffing N, Kassam N, Wu L, and Butcher EC. 1999. The chemokine receptor CCR4 in vascular recognition by cutaneous but not intestinal memory T cells. Nature 1999 400:6746 400: 776–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Homey B, Alenius H, Müller A, Soto H, Bowman EP, Yuan W, McEvoy L, Lauerma AI, Assmann T, Bünemann E, Lehto M, Wolff H, Yen D, Marxhausen H, To W, Sedgwick J, Ruzicka T, Lehmann P, and Zlotnik A. 2002. CCL27–CCR10 interactions regulate T cell–mediated skin inflammation. Nature Medicine 2002 8:2 8: 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Okla K, Farber DL, and Zou W. 2021. Tissue-resident memory T cells in tumor immunity and immunotherapy. Journal of Experimental Medicine 218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang ZQ, Milne K, Derocher H, Webb JR, Nelson BH, and Watson PH. 2016. CD103 and Intratumoral Immune Response in Breast Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 22: 6290–6297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Egelston CA, Avalos C, Tu TY, Rosario A, Wang R, Solomon S, Srinivasan G, Nelson MS, Huang Y, Lim MH, Simons DL, He TF, Yim JH, Kruper L, Mortimer J, Yost S, Guo W, Ruel C, Frankel PH, Yuan Y, and Lee PP. 2019. Resident memory CD8+ T cells within cancer islands mediate survival in breast cancer patients. JCI Insight 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Park MH, Kwon SY, Choi JE, Gong G, and Bae YK. 2020. Intratumoral CD103-positive tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes are associated with favourable prognosis in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Histopathology 77: 560–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lin R, Zhang H, Yuan Y, He Q, Zhou J, Li S, Sun Y, Li DY, Qiu HB, Wang W, Zhuang Z, Chen B, Huang Y, Liu C, Wang Y, Cai S, Ke Z, and He W. 2020. Fatty Acid Oxidation Controls CD8+ Tissue-Resident Memory T-cell Survival in Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res 8: 479–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang B, Wu S, Zeng H, Liu Z, Dong W, He W, Chen X, Dong X, Zheng L, Lin T, and Huang J. 2015. CD103+ Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes Predict a Favorable Prognosis in Urothelial Cell Carcinoma of the Bladder. Journal of Urology 194: 556–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ganesan AP, Clarke J, Wood O, Garrido-Martin EM, Chee SJ, Mellows T, Samaniego-Castruita D, Singh D, Seumois G, Alzetani A, Woo E, Friedmann PS, King E. v., Thomas GJ, Sanchez-Elsner T, Vijayanand P, and Ottensmeier CH. 2017. Tissue-resident memory features are linked to the magnitude of cytotoxic T cell responses in human lung cancer. Nature Immunology 2017 18:8 18: 940–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Djenidi F, Adam J, Goubar A, Durgeau A, Meurice G, de Montpréville V, Validire P, Besse B, and Mami-Chouaib F. 2015. CD8 + CD103 + Tumor–Infiltrating Lymphocytes Are Tumor-Specific Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells and a Prognostic Factor for Survival in Lung Cancer Patients. The Journal of Immunology 194: 3475–3486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Koh J, Kim S, Kim M-Y, Go H, Jeon YK, Chung DH, Koh J, Kim S, Kim M-Y, Go H, Jeon YK, and Chung DH. 2017. Prognostic implications of intratumoral CD103+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 8: 13762–13769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Webb JR, Milne K, and Nelson BH. 2015. PD-1 and CD103 Are Widely Coexpressed on Prognostically Favorable Intraepithelial CD8 T Cells in Human Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 3: 926–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Webb JR, Milne K, Watson P, DeLeeuw RJ, and Nelson BH. 2014. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes Expressing the Tissue Resident Memory Marker CD103 Are Associated with Increased Survival in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 20: 434–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Workel HH, Komdeur FL, Wouters MCA, Plat A, Klip HG, Eggink FA, Wisman GBA, Arts HJG, Oonk MHM, Mourits MJE, Yigit R, Versluis M, Duiker EW, Hollema H, de Bruyn M, and Nijman HW. 2016. CD103 defines intraepithelial CD8+ PD1+ tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes of prognostic significance in endometrial adenocarcinoma. Eur J Cancer 60: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Komdeur FL, Prins TM, van de Wall S, Plat A, Wisman GBA, Hollema H, Daemen T, Church DN, de Bruyn M, and Nijman HW. 2017. CD103+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are tumor-reactive intraepithelial CD8+ T cells associated with prognostic benefit and therapy response in cervical cancer. Oncoimmunology 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lohneis P, Sinn M, Bischoff S, Jühling A, Pelzer U, Wislocka L, Bahra M, Sinn B. v., Denkert C, Oettle H, Bläker H, Riess H, Jöhrens K, and Striefler JK. 2017. Cytotoxic tumour-infiltrating T lymphocytes influence outcome in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Eur J Cancer 83: 290–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hewavisenti R, Ferguson A, Wang K, Jones D, Gebhardt T, Edwards J, Zhang M, Britton W, Yang J, Hong A, and Palendira U. 2020. CD103+ tumor-resident CD8+ T cell numbers underlie improved patient survival in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Han L, Gao QL, Zhou XM, Shi C, Chen GY, Song YP, Yao YJ, Zhao YM, Wen XY, Liu SL, Qi YM, and Gao YF. 2020. Characterization of CD103+ CD8+ tissue-resident T cells in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: may be tumor reactive and resurrected by anti-PD-1 blockade. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 69: 1493–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Edwards J, Wilmott JS, Madore J, Gide TN, Quek C, Tasker A, Ferguson A, Chen J, Hewavisenti R, Hersey P, Gebhardt T, Weninger W, Britton WJ, Saw RPM, Thompson JF, Menzies AM, Long G. v., Scolyer RA, and Palendira U. 2018. CD103+ Tumor-Resident CD8+ T Cells Are Associated with Improved Survival in Immunotherapy-Naïve Melanoma Patients and Expand Significantly During Anti–PD-1 Treatment. Clinical Cancer Research 24: 3036–3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Malik BT, Byrne KT, Vella JL, Zhang P, Shabaneh TB, Steinberg SM, Molodtsov AK, Bowers JS, Angeles C. v., Paulos CM, Huang YH, and Turk MJ. 2017. Resident memory T cells in the skin mediate durable immunity to melanoma. Sci Immunol 2: 6346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Watanabe R, Gehad A, Yang C, Scott LL, Teague JE, Schlapbach C, Elco CP, Huang V, Matos TR, Kupper TS, and Clark RA. 2015. Human skin is protected by four functionally and phenotypically discrete populations of resident and recirculating memory T cells. Sci Transl Med 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Enamorado M, Iborra S, Priego E, Cueto FJ, Quintana JA, Martýnez-Cano S, Mejyás-Perez E, Esteban M, Melero I, Hidalgo A, and Sancho D. 2017. Enhanced anti-tumour immunity requires the interplay between resident and circulating memory CD8+ T cells. Nature Communications 2017 8:1 8: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gattinoni L, Lugli E, Ji Y, Pos Z, Paulos CM, Quigley MF, Almeida JR, Gostick E, Yu Z, Carpenito C, Wang E, Douek DC, Price DA, June CH, Marincola FM, Roederer M, and Restifo NP. 2011. A human memory T cell subset with stem cell–like properties. Nature Medicine 2011 17:10 17: 1290–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hong H, Gu Y, Sheng SY, Lu CG, Zou JY, and Wu CY. 2016. The Distribution of Human Stem Cell–like Memory T Cell in Lung Cancer. J Immunother 39: 233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Alvarez-Fernández C, Escribà-Garcia L, Caballero AC, Escudero-López E, Ujaldón-Miró C, Montserrat-Torres R, Pujol-Fernández P, Sierra J, and Briones J. 2021. Memory stem T cells modified with a redesigned CD30-chimeric antigen receptor show an enhanced antitumor effect in Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Transl Immunology 10: e1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gattinoni L, Zhong XS, Palmer DC, Ji Y, Hinrichs CS, Yu Z, Wrzesinski C, Boni A, Cassard L, Garvin LM, Paulos CM, Muranski P, and Restifo NP. 2009. Wnt signaling arrests effector T cell differentiation and generates CD8+ memory stem cells. Nature Medicine 2009 15:7 15: 808–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gannon PO, Baumgaertner P, Huber A, Iancu EM, Cagnon L, Maillard SA, ene M H. Hajjami el, Speiser DE, and Rufer N. 2017. Rapid and Continued T-Cell Differentiation into Long-term Effector and Memory Stem Cells in Vaccinated Melanoma Patients. Clinical Cancer Research 23: 3285–3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Xu Y, Zhang M, Ramos CA, Durett A, Liu E, Dakhova O, Liu H, Creighton CJ, Gee AP, Heslop HE, Rooney CM, Savoldo B, and Dotti G. 2014. Closely related T-memory stem cells correlate with in vivo expansion of CAR.CD19-T cells and are preserved by IL-7 and IL-15. Blood 123: 3750–3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sabatino M, Hu J, Sommariva M, Gautam S, Fellowes V, Hocker JD, Dougherty S, Qin H, Klebanoff CA, Fry TJ, Gress RE, Kochenderfer JN, Stroncek DF, Ji Y, and Gattinoni L. 2016. Generation of clinical-grade CD19-specific CAR-modified CD8+ memory stem cells for the treatment of human B-cell malignancies. Blood 128: 519–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kondo T, Ando M, Nagai N, Tomisato W, Srirat T, Liu B, Mise-Omata S, Ikeda M, Chikuma S, Nishimasu H, Nureki O, Ohmura M, Hayakawa N, Hishiki T, Uchibori R, Ozawa K, and Yoshimura A. 2020. The NOTCH–FOXM1 Axis Plays a Key Role in Mitochondrial Biogenesis in the Induction of Human Stem Cell Memory–like CAR-T Cells. Cancer Res 80: 471–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Biasco L, Izotova N, Rivat C, Ghorashian S, Richardson R, Guvenel A, Hough R, Wynn R, Popova B, Lopes A, Pule M, Thrasher AJ, and Amrolia PJ. 2021. Clonal expansion of T memory stem cells determines early anti-leukemic responses and long-term CAR T cell persistence in patients. Nature Cancer 2021 2:6 2: 629–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Macallan DC, Borghans JAM, and Asquith B. 2017. Human T Cell Memory: A Dynamic View. Vaccines (Basel) 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hammarlund E, Lewis MW, Hansen SG, Strelow LI, Nelson JA, Sexton GJ, Hanifin JM, and Slifka MK. 2003. Duration of antiviral immunity after smallpox vaccination. Nature Medicine 2003 9:9 9: 1131–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Han J, Zhao Y, Shirai K, Molodtsov A, Kolling FW, Fisher JL, Zhang P, Yan S, Searles TG, Bader JM, Gui J, Cheng C, Ernstoff MS, Turk MJ, and Angeles C. v.. 2021. Resident and circulating memory T cells persist for years in melanoma patients with durable responses to immunotherapy. Nature Cancer 2021 2:3 2: 300–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bartolomé-Casado R, Landsverk OJB, Chauhan SK, Richter L, Phung D, Greiff V, Risnes LF, Yao Y, Neumann RS, Yaqub S, Øyen O, Horneland R, Aandahl EM, Paulsen V, Sollid LM, Qiao SW, Baekkevold ES, and Jahnsen FL. 2019. Resident memory CD8 T cells persist for years in human small intestine. Journal of Experimental Medicine 216: 2412–2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wakim LM, Woodward-Davis A, and Bevan MJ. 2010. Memory T cells persisting within the brain after local infection show functional adaptations to their tissue of residence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 17872–17879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pallett LJ, Burton AR, Amin OE, Rodriguez-Tajes S, Patel AA, Zakeri N, Jeffery-Smith A, Swadling L, Schmidt NM, Baiges A, Gander A, Yu D, Nasralla D, Froghi F, Iype S, Davidson BR, Thorburn D, Yona S, Forns X, and Maini MK. 2020. Longevity and replenishment of human liver-resident memory T cells and mononuclear phagocytes. Journal of Experimental Medicine 217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Strobl J, Pandey RV, Krausgruber T, Bayer N, Kleissl L, Reininger B, Vieyra-Garcia P, Wolf P, Jentus MM, Mitterbauer M, Wohlfarth P, Rabitsch W, Stingl G, Bock C, and Stary G. 2020. Long-term skin-resident memory T cells proliferate in situ and are involved in human graft-versus-host disease. Sci Transl Med 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wijeyesinghe S, Beura LK, Pierson MJ, Stolley JM, Adam OA, Ruscher R, Steinert EM, Rosato PC, Vezys V, and Masopust D. 2021. Expansible residence decentralizes immune homeostasis. Nature 2021 592:7854 592: 457–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Slütter B, van Braeckel-Budimir N, Abboud G, Varga SM, Salek-Ardakani S, and Harty JT. 2017. Dynamic equilibrium of lung Trm dictates waning immunity after Influenza A infection. Sci Immunol 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wu T, Hu Y, Lee Y-T, Bouchard KR, Benechet A, Khanna K, and Cauley LS. 2014. Lung-resident memory CD8 T cells (TRM) are indispensable for optimal cross-protection against pulmonary virus infection. J Leukoc Biol 95: 215–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pizzolla A, Nguyen THO, Smith JM, Brooks AG, Kedzierska K, Heath WR, Reading PC, and Wakim LM. 2017. Resident memory CD8+ T cells in the upper respiratory tract prevent pulmonary influenza virus infection. Sci Immunol 2: 6970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Slütter B, van Braeckel-Budimir N, Abboud G, Varga SM, Salek-Ardakani S, and Harty JT. 2017. Dynamics of influenza-induced lung-resident memory T cells underlie waning heterosubtypic immunity. Sci Immunol 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Snyder ME, Finlayson MO, Connors TJ, Dogra P, Senda T, Bush E, Carpenter D, Marboe C, Benvenuto L, Shah L, Robbins H, Hook JL, Sykes M, D’Ovidio F, Bacchetta M, Sonett JR, Lederer DJ, Arcasoy S, Sims PA, and Farber DL. 2019. Generation and persistence of human tissue-resident memory T cells in lung transplantation. Sci Immunol 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Boddupalli CS, Nair S, Gray SM, Nowyhed HN, Verma R, Gibson JA, Abraham C, Narayan D, Vasquez J, Hedrick CC, Flavell RA, Dhodapkar KM, Kaech SM, and Dhodapkar M. v.. 2016. ABC transporters and NR4A1 identify a quiescent subset of tissue-resident memory T cells. J Clin Invest 126: 3905–3916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Christian LS, Wang L, Lim B, Deng D, Wu H, Wang XF, and Li QJ. 2021. Resident memory T cells in tumor-distant tissues fortify against metastasis formation. Cell Rep 35: 109118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Biasco L, Scala S, Basso Ricci L, Dionisio F, Baricordi C, Calabria A, Giannelli S, Cieri N, Barzaghi F, Pajno R, Al-Mousa H, Scarselli A, Cancrini C, Bordignon C, Roncarolo MG, Roncarolo MG, Montini E, Bonini C, and Aiuti A. 2015. In vivo tracking of T cells in humans unveils decade-long survival and activity of genetically modified T memory stem cells. Sci Transl Med 7: 273ra13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Oliveira G, Ruggiero E, Stanghellini MTL, Cieri N, D’Agostino M, Fronza R, Lulay C, Dionisio F, Mastaglio S, Greco R, Peccatori J, Aiuti A, Ambrosi A, Biasco L, Bondanza A, Lambiase A, Traversari C, Vago L, von Kalle C, Schmidt M, Bordignon C, Ciceri F, and Bonini C. 2015. Tracking genetically engineered lymphocytes long-term reveals the dynamics of t cell immunological memory. Sci Transl Med 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Costa Del Amo P, Lahoz-Beneytez J, Boelen L, Ahmed R, Miners KL, Zhang Y, Roger L, Jones RE, Fuertes Marraco SA, Speiser DE, Baird DM, Price DA, Ladell K, Macallan D, and Asquith B. 2018. Human T SCM cell dynamics in vivo are compatible with long-lived immunological memory and stemness. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Fuertes Marraco SA, Soneson C, Cagnon L, Gannon PO, Allard M, Maillard SA, Montandon N, Rufer N, Waldvogel S, Delorenzi M, and Speiser DE. 2015. Long-lasting stem cell-like memory CD8+ T cells with a naïve-like profile upon yellow fever vaccination. Sci Transl Med 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Böttcher JP, Bonavita E, Chakravarty P, Blees H, Cabeza-Cabrerizo M, Sammicheli S, Rogers NC, Sahai E, Zelenay S, and Reis e Sousa C. 2018. NK Cells Stimulate Recruitment of cDC1 into the Tumor Microenvironment Promoting Cancer Immune Control. Cell 172: 1022–1037.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Benhammadi M, Mathé J, Dumont-Lagacé M, Kobayashi KS, Gaboury L, Brochu S, and Perreault C. 2020. IFN-λ Enhances Constitutive Expression of MHC Class I Molecules on Thymic Epithelial Cells. The Journal of Immunology 205: 1268–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Castiglioni P, Hall DS, Jacovetty EL, Ingulli E, and Zanetti M. 2008. Protection against Influenza A Virus by Memory CD8 T Cells Requires Reactivation by Bone Marrow-Derived Dendritic Cells. The Journal of Immunology 180: 4956–4964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zammit DJ, Cauley LS, and Pham Q-M. 2005. Dendritic Cells Maximize the Memory CD8 T Cell Response to Infection. Shedlock and Shen 22: 561–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lumsden JM, Roberts JM, Harris NL, Peach RJ, and Ronchese F. 2000. Differential requirement for CD80 and CD80/CD86-dependent costimulation in the lung immune response to an influenza virus infection. J Immunol 164: 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Schenkel JM, Fraser KA, Beura LK, Pauken KE, Vezys V, and Masopust D. 2014. Resident memory CD8 t cells trigger protective innate and adaptive immune responses. Science (1979) 346: 98–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ariotti S, Hogenbirk MA, Dijkgraaf FE, Visser LL, Hoekstra ME, Song JY, Jacobs H, Haanen JB, and Schumacher TN. 2014. Skin-resident memory CD8+ T cells trigger a state of tissue-wide pathogen alert. Science (1979) 346: 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Woodland DL, and Kohlmeier JE. 2009. Migration, maintenance and recall of memory T cells in peripheral tissues. Nature Reviews Immunology 2009 9:3 9: 153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Low JS, Farsakoglu Y, Amezcua Vesely MC, Sefik E, Kelly JB, Harman CCD, Jackson R, Shyer JA, Jiang X, Cauley LS, Flavell RA, and Kaech SM. 2020. Tissue-resident memory T cell reactivation by diverse antigen-presenting cells imparts distinct functional responses. Journal of Experimental Medicine 217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Menares E, Gálvez-Cancino F, Cáceres-Morgado P, Ghorani E, López E, Díaz X, Saavedra-Almarza J, Figueroa DA, Roa E, Quezada SA, and Lladser A. 2019. Tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells amplify anti-tumor immunity by triggering antigen spreading through dendritic cells. Nature Communications 2019 10:1 10: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Fernández-Medarde A, and Santos E. 2011. Ras in Cancer and Developmental Diseases. Genes Cancer 2: 344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Baines AT, Xu D, and Der CJ. 2011. Inhibition of Ras for cancer treatment: the search continues. 10.4155/fmc.11.121 3: 1787–1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Erlanson DA, and Webster KR. 2021. Targeting mutant KRAS. Curr Opin Chem Biol 62: 101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Leidner R, Sanjuan Silva N, Huang H, Sprott D, Zheng C, Shih Y-P, Leung A, Payne R, Sutcliffe K, Cramer J, Rosenberg SA, Fox BA, Urba WJ, and Tran E. 2022. Neoantigen T-Cell Receptor Gene Therapy in Pancreatic Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 386: 2112–2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Shamalov K, Levy SN, Horovitz-Fried M, and Cohen CJ. 2017. The mutational status of p53 can influence its recognition by human T-cells. Oncoimmunology 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Low L, Goh A, Koh J, Lim S, and Wang CI. 2019. Targeting mutant p53-expressing tumours with a T cell receptor-like antibody specific for a wild-type antigen. Nature Communications 2019 10:1 10: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Wu D, Gallagher DT, Gowthaman R, Pierce BG, and Mariuzza RA. 2020. Structural basis for oligoclonal T cell recognition of a shared p53 cancer neoantigen. Nature Communications 2020 11:1 11: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Zhang L, Theodoropoulos PC, Eskiocak U, Wang W, Moon YA, Posner B, Williams NS, Wright WE, Kim SB, Nijhawan D, de Brabander JK, and Shay JW. 2016. Selective targeting of mutant adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) in colorectal cancer. Sci Transl Med 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Spira A, Disis ML, Schiller JT, Vilar E, Rebbeck TR, Bejar R, Ideker T, Arts J, Yurgelun MB, Mesirov JP, Rao A, Garber J, Jaffee EM, and Lippman SM. 2016. Leveraging premalignant biology for immune-based cancer prevention. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113: 10750–10758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Campbell JD, Mazzilli SA, Reid ME, Dhillon SS, Platero S, Beane J, and Spira AE. 2016. The Case for a Pre-Cancer Genome Atlas (PCGA). Cancer Prevention Research 9: 119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Amor C, Feucht J, Leibold J, Ho YJ, Zhu C, Alonso-Curbelo D, Mansilla-Soto J, Boyer JA, Li X, Giavridis T, Kulick A, Houlihan S, Peerschke E, Friedman SL, Ponomarev V, Piersigilli A, Sadelain M, and Lowe SW. 2020. Senolytic CAR T cells reverse senescence-associated pathologies. Nature 2020 583:7814 583: 127–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Bart J, Groen HJM, van der Graaf WTA, Hollema H, Hendrikse NH, Vaalburg W, Sleijfer DT, and de Vries EGE. 2002. An oncological view on the blood–testis barrier. Lancet Oncol 3: 357–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Coles CH, McMurran C, Lloyd A, Hock M, Hibbert L, Raman MCC, Hayes C, Lupardus P, Cole DK, and Harper S. 2020. T cell receptor interactions with human leukocyte antigen govern indirect peptide selectivity for the cancer testis antigen MAGE-A4. Journal of Biological Chemistry 295: 11486–11494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Abate-Daga D, Speiser DE, Chinnasamy N, Zheng Z, Xu H, Feldman SA, Rosenberg SA, and Morgan RA. 2014. Development of a T Cell Receptor Targeting an HLA-A*0201 Restricted Epitope from the Cancer-Testis Antigen SSX2 for Adoptive Immunotherapy of Cancer. PLoS One 9: e93321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Raza A, Merhi M, Philipose Inchakalody V, Krishnankutty R, Relecom A, Uddin S, and Dermime S. 2020. Unleashing the immune response to NY-ESO-1 cancer testis antigen as a potential target for cancer immunotherapy. J Transl Med 18: 140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Jakobsen MK, and Gjerstorff MF. 2020. CAR T-Cell Cancer Therapy Targeting Surface Cancer/Testis Antigens. Front Immunol 11: 1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Tuohy VK 2014. Retired self-proteins as vaccine targets for primary immunoprevention of adult-onset cancers. 10.1586/14760584.2014.953063 13: 1447–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Tuohy VK, Jaini R, Johnson JM, Loya MG, Wilk D, Downs-Kelly E, and Mazumder S. 2016. Targeted Vaccination against Human α-Lactalbumin for Immunotherapy and Primary Immunoprevention of Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers 2016, Vol. 8, Page 56 8: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Lepore M, Kalinichenko A, Calogero S, Kumar P, Paleja B, Schmaler M, Narang V, Zolezzi F, Poidinger M, Mori L, and de Libero G. 2017. Functionally diverse human T cells recognize non-microbial antigens presented by MR1. Elife 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Schwarz B, Morabito KM, Ruckwardt TJ, Patterson DP, Avera J, Miettinen HM, Graham BS, and Douglas T. 2016. Viruslike Particles Encapsidating Respiratory Syncytial Virus M and M2 Proteins Induce Robust T Cell Responses. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2: 2324–2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Haddadi S, Thanthrige-Don N, Afkhami S, Khera A, Jeyanathan M, and Xing Z. 2017. Expression and role of VLA-1 in resident memory CD8 T cell responses to respiratory mucosal viral-vectored immunization against tuberculosis. Scientific Reports 2017 7:1 7: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.MacDonald DC, Singh H, Whelan MA, Escors D, Arce F, Bottoms SE, Barclay WS, Maini M, Collins MK, and Rosenberg WC. 2013. Harnessing alveolar macrophages for sustained mucosal T-cell recall confers long-term protection to mice against lethal influenza challenge without clinical disease. Mucosal Immunology 2014 7:1 7: 89–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Flórido M, Muflihah H, Lin LCW, Xia Y, Sierro F, Palendira M, Feng CG, Bertolino P, Stambas J, Triccas JA, and Britton WJ. 2018. Pulmonary immunization with a recombinant influenza A virus vaccine induces lung-resident CD4+ memory T cells that are associated with protection against tuberculosis. Mucosal Immunology 2018 11:6 11: 1743–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Morabito KM, Ruckwardt TR, Redwood AJ, Moin SM, Price DA, and Graham BS. 2016. Intranasal administration of RSV antigen-expressing MCMV elicits robust tissue-resident effector and effector memory CD8+ T cells in the lung. Mucosal Immunology 2017 10:2 10: 545–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]