Abstract

Background

Therapeutic modalities including chemo, radiation, immunotherapy, etc. induce PD-L1 expression that facilitates the adaptive immune resistance to evade the antitumour immune response. IFN-γ and hypoxia are some of the crucial inducers of PD-L1 expression in tumour and systemic microenvironment which regulate the expression of PD-L1 via various factors including HIF-1α and MAPK signalling. Hence, inhibition of these factors is crucial to regulate the induced PD-L1 expression and to achieve a durable therapeutic outcome by averting the immunosuppression.

Methods

B16-F10 melanoma, 4T1 breast carcinoma, and GL261 glioblastoma murine models were established to investigate the in vivo antitumour efficacy of Ponatinib. Western blot, immunohistochemistry, and ELISA were performed to determine the effect of Ponatinib on the immunomodulation of tumour microenvironment (TME). CTL assay and flow cytometry were such as p-MAPK, p-JNK, p-Erk, and cleaved caspase-3 carried out to evaluate the systemic immunity induced by Ponatinib. RNA sequencing, immunofluorescence and Western blot analysis were used to determine the mechanism of PD-L1 regulation by Ponatinib. Antitumour immunity induced by Ponatinib were compared with Dasatinib.

Results

Here, Ponatinib treatment delayed the growth of tumours by inhibiting PD-L1 and modulating TME. It also downregulated the level of PD-L1 downstream signalling molecules. Ponatinib enhanced the CD8 T cell infiltration, regulated Th1/Th2 ratio and depleted tumour associated macrophages (TAMs) in TME. It induced a favourable systemic antitumour immunity by enhancing CD8 T cell population, tumour specific CTL activity, balancing the Th1/Th2 ratio and lowering PD-L1 expression. Ponatinib inhibited FoxP3 expression in tumour and spleen. RNA sequencing data revealed that Ponatinib treatment downregulated the genes related to transcription including HIF-1α. Further mechanistic studies showed that it inhibited the IFN-γ and hypoxia induced PD-L1 expression via regulating HIF-1α. Dasatinib was used as control to prove that Ponatinib induced antitumour immunity is via PD-L1 inhibition mediated T cell activation.

Conclusions

RNA sequencing data along with rigorous in vitro and in vivo studies revealed a novel molecular mechanism by which Ponatinib can inhibit the induced PD-L1 levels via regulating HIF-1α expression which leads to modulation of tumour microenvironment. Thus, our study provides a novel therapeutic insight of Ponatinib for the treatment of solid tumours where it can be used alone or in combination with other drugs which are known to induce PD-L1 expression and generate adaptive resistance.

Subject terms: Cancer immunotherapy, Cancer microenvironment

Background

Programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) on tumour or immune cells engage with Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) on tumour infiltrating lymphocytes which results into their dysfunction and exhaustion [1, 2]. Therapeutic modalities including chemodrugs, radiation, immunotherapeutics, etc showed anti-tumour efficacy by inducing IFN-γ. In tumour microenvironment (TME), inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ induce the PD-L1 upregulation which increases the resistance to IFN-γ mediated apoptosis via reverse signalling by PD-L1 on cancer cells [3, 4]. This process is well known as adaptive immune resistance and is used by cancer cells to evade antitumour immune response [5]. Therefore the upregulated PD-L1 is directly associated with immune invasion and tumour progression [6] by delivering anti-apoptotic signals to cancer cells and is sufficient for inhibition of CD8 T cell cytotoxicity even in the absence of PD-1 expressing T cells [7]. Hence, it is crucial to inhibit the PD-L1 overexpression which would not only allow the T cells to proliferate and enhance their antitumour activity but also promote the apoptosis of cancer cells. Previous studies have shown that PD-L1 expression is regulated by epigenetic modifiers (MLL1, BRD4), transcription factors (HIF-1α, NF-κβ etc), post-transcriptional regulators (AMP-activated protein kinases, CSN5), and microRNAs (miR570) [8]. Hypoxia and IFN-γ are the main inducers of PD-L1 expression in tumours and systemic environment which increase the resistance to adaptive immunity [9]. Notably, anticancer therapies including radiation, chemo and immunotherapy induce the PD-L1 overexpression which ultimately results into the resistance to the therapy, causing tumour relapse and provide an unsatisfactory therapeutic outcome [10, 11]. Hence, the importance of PD-L1 regulation has opened a new door to the development of drug which can specifically modulate the induced PD-L1 expression and its associated signalling pathway [12].

Ponatinib, a multi-targeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor inhibits Bcr-Abl and is approved by FDA for refractory chronic myelogenous leukaemia (CML) positive for the Philadelphia chromosome [13]. It is also known to inhibit several other important tyrosine kinases including fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs) [14]. Previously, we have shown that Ponatinib can bind to PD-L1 and inhibit the growth of melanoma [15]. Hence in this study, we wanted to check if Ponatinib can inhibit the induced PD-L1 expression and investigate the mechanism of PD-L1 inhibition and the antitumour immunity induced by Ponatinib in different tumour models.

We showed that Ponatinib delayed the growth of tumours by modulating antitumour immunity and by regulating PD-L1 expression. In tumour, it also inhibited the PD-L1 associated pathway by inhibiting the phosphorylation of MAPK, Erk, and JNK. Ponatinib induced an immunomodulatory effect in tumour microenvironment (TME) by increasing the CD8-T cell infiltrate and regulating Th1/Th2 balance. Furthermore, Ponatinib treatment also reduced the FoxP3 expression and infiltration of tumour associated macrophages in TME which are known to create immunosuppressive environment and lead to immune resistance and poor outcome [16, 17]. Moreover, Ponatinib modulated the systemic immunity by promoting cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) activity, T cell proliferation in spleen and shifted the Th1/Th2 ratio towards a dominating Th1 population. It also inhibited PD-L1 expression in both spleen and serum. RNA sequencing analysis of tumour revealed that Ponatinib downregulated transcription related genes including HIF-1α. Further in vitro mechanistic study confirmed that Ponatinib inhibited the PD-L1 overexpression induced by both IFN-γ and hypoxia via inhibition of HIF-1α. Taken together, RNA sequencing data along with rigorous in vitro and in vivo studies revealed a novel therapeutic insight of Ponatinib which delay the growth of tumours and improved the survival by remodelling the immune-suppressive TME through the inhibition of induced PD-L1 levels. Finally, to show that Ponatinib mediated antitumour immunity was via PD-L1 inhibition, Dasatinib was used as control and the results indicated that Dasatinib did not induce CD8 T cell infiltration and activation in tumour whereas Ponatinib increased the activation of CD8 T cell and also inhibited the exhaustion of CD8 T cells.

Materials and methods

Drug and reagents

Ponatinib was obtained from Selleckchem, USA. FITC anti-mouse CD3 Antibody (Cat #100204), APC anti-mouse CD4 Antibody (Cat #100412), APC anti-mouse CD8 (Cat # 100712), PD-L1 antibody (Cat #124302), FoxP3 antibody (Cat #126401), p-Erk antibody (Cat #675505) and p-P38 antibody (Cat #690202), APC-Cy7 anti-mouse CD45 (Cat #147718), PE anti-mouse CD69 (Cat #104507), PE anti-mouse TIM3 (Cat #134003), APC anti-mouse PD1 (Cat #135210), anti-mouse F4/80 (Cat #123102), anti-mouse CD86 (Cat #105002), anti-mouse Arg1 (Cat #678802) were purchased from Biolegend, USA. p-JNK antibody (Cat no. 9251S); Cleaved Caspase-3 (Cat no. 9661S) antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling, Danvers, USA. ELISA kits for IL2 (Cat no. E-EL-M0042), IL4 (Cat no. E-EL-M0043) and IFN-γ (Cat no. E-EL-M0048) were purchased from Elabsciences, USA. HIF-1α antibody (Cat no. E-AB-31662) was purchased from Elabsciences, USA.

Cell line and cell cultures

Mouse melanoma cell line B16-F10 and MCF-7 cells were purchased from National centre for cell sciences (NCCS), India. 4T1 and GL-261 cell line was a kind gift from Dr. Rajkumar Banerjee and Dr. Sumana Chakravarty respectively (IICT, Hyderabad). The cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator and at 37 °C.

Animals

Female C57BL/6 J and BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old) were used for in vivo experiments. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with Institutional Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under protocols approved by the NII Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

In vivo tumour isograft model and dosing regimen

B16-F10 melanoma tumour model was established by injecting 2 × 105 cells with matrigel subcutaneously into right flank of C57/BL6J mice. Similarly, 4T1 breast carcinoma model was established by injecting 8 × 105 cells in mammary pad of BALB/c female mice. For GL261 glioblastoma model, 1 × 106 cells were implanted in the right flank of C57/BL6 mice. The mice were randomly divided into either two or three groups, once the tumour volume reached 50–100 mm3, and the drug was administered daily for 10 days. Mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with Ponatinib or Dasatinib (15 mg kg−1 BW) dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or DMSO alone (control).

Tumour volumes and BW were measured every day. Tumour volumes were determined by direct measurement with a caliper and calculated according to the following formula:

Immune cell population in tumours and spleens of melanoma bearing mice

At the end of the experiment both B16-F10, 4T1, and GL261 bearing mice were sacrificed and tumours were harvested and single cell suspension was prepared. Briefly, tumours were cut into tiny pieces and mechanically dissociated with the back of the syringe in a buffer containing 0.25 M EDTA with 2% FBS and 2 % BSA. This suspension was incubated for 5 mins at room temperature and the upper layer of the suspension was passed through a 28 G syringe in a fresh tube. Cells were then washed, resuspended in staining buffer.

Spleens were harvested and single cell suspension were prepared by mechanical dissociation with back of the syringe followed by passing through 70 µm strainer. Cells were and resuspended in staining buffer (PBS containing 4% FBS) after washing 2–3 times with PBS.

For staining, 106 splenocytes or cells isolated from tumours were stained with different antibodies. The cell populations were acquired on BD FACSVerse flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA) and the data were analysed using FlowJo software (FlowJo LLC, OR, USA).

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity in melanoma-bearing mice

For CTL activity, splenocytes isolated from both B16-F10 and 4T1 bearing mice were co-cultured with their respective cancer cells where splenocytes were used as effector cells (E) and B16-F10 and 4T1 cells were used as target cells (T).

Briefly, B16-F10 or 4T1 cells were seeded in a cell culture treated 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well in DMEM complete medium. Splenocyte (E) from respective models were added to target cells (T) in the ratio of 20:1 and 40:1 (effector cells to target cells). The plates were then incubated at 37 °C and after 24 h, 20 µL of MTT solution (5 mg mL−1) was added to each well and the plates were incubated for 3 h. The medium was discarded, formazan crystals were dissolved by 100 µL of 100% DMSO. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a BioTek SynergyH1 multiplate reader, USA. The percentage of the killed target cells were determined using following equation:

where ODE, ODT, and ODS, are optical density (absorbance) of control effector cells, control target cells, and co-cultured cells, respectively.

Expression of cytokine in tumour and spleen of the tumour bearing mice

The single cell suspension of tumours was prepared by enzymatic treatment (collagen 0.1 mg mL−1, DnaseI 10 µg mL−1). Splenocytes were obtained as described above. Tumour and spleen cells were lysed by Radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer. The level of IL-2, IL-4 and IFN-γ in the supernatants were detected using murine ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Tissue cytokine concentrations were compared using unpaired t test by GraphPad Prism 6 software.

Immunohistochemistry

At the end of the experiment, tumours were collected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and paraffinised. Serial microsections were prepared for IHC analysis. After deparaffinisation, antigen was retrieved. The sections were then blocked with serum by incubating them for 1 h, and then incubated with the anti-CD8 or anti-PD-L1 or anti-FoxP3 or anti-HIF-1α antibody overnight at 4 °C. The sections were washed three times in PBS and incubated with alexafluor-conjugated secondary antibody for 3 h. Following washing with PBS. The slides were washed with water for 10–15 min, and then counterstained with haematoxylin. The sections were dehydrated by using series of ethanol and xylene. The images were obtained by cell imaging multi-mode reader, Cytation 3, Biotek, USA.

Western blot analysis

The protein content of B16-F10 and MCF-7 cell lysate or the spleen and tumour homogenates from the B16-F10 bearing mice were measured by Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. Blood samples were collected from the tip of the tail and diluted into PBS with heparin (1000 U ml−1). The blood was centrifuged (1500 r.p.m., 10 min, 4 °C) and serum were collected to measure the protein content by BCA assay. The protein samples (100 µg per lane) were separated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. The membranes were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in tris buffered saline with tween 20 (TBST) and incubated with primary antibodies (1:2000) against β-actin, PD-L1, FoxP3, anti-p-P38, anti-p-Erk, anti-p-JNK, anti-Cleaved Caspase-3 or HIF-1α overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were then washed with TBST and incubated with HRP conjugated secondary antibody (1:2000) for 1 h at room temperature. After repetitive washing with TBST, the blots were developed using Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents and visualised by G:Box Chemi XRQ imaging system (Syngene USA Inc.).

RNA sequencing

Quality assessment of the raw fastq reads of the sample was performed using FastQC v.0.11.9 (default parameters) and summarised using MultiQC v.1.9. The raw fastq reads were preprocessed using Fastp v.0.20.1(parameters: --qualified_quality_phred 30 --trim_front1 9 --trim_front2 9 --trim_tail1 0 --trim_tail2 0 --length_required 50 –correction --trim_poly_g), followed by quality re-assessment using FastQC and summarised using MultiQC. The splicesites and exons were extracted from mouse genome (NCBI: mouse genome (GRCm39), and indexed using HISAT2 v.2.2.1 (Parameters: hisat2-build –ss genome_splicesites.txt --exon genome_exons.txt). The indexed genome was then mapped against processed reads using HISAT2 (parameters: --dta --mm --summary-file --un-conc-gz --al-conc-gz). Aligned reads were converted to bam and sorted using Samtools v.1.7 (sort parameters: sort -l 9). The Aligned reads from individual samples were quantified using feature count v. 0.46. 1 (parameters: -g gene_id -F GTF -p) to obtain gene counts. These gene counts were used as inputs to DESeq2 [18] for differential expression estimation (parameters: threshold of statistical significance --alpha 0.05; p-value adjustment method: BH).

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was done using gProfiler (parameter: organism= Mus musculus) online server. Pathway enrichment analysis was done using InnateDB web server. Gene ontology and metabolic pathway enrichment analysis were also performed using Network Analyst (https://www.networkanalyst.ca/) online server [19]. The featureCout generated count file was converted to NetworkAnalyst input format and processed using default parameters. Geneset Network Analysis was done using Moderated Welch’s T test.

In vitro IFN-γ and hypoxia-induced PD-L1 inhibition

MCF and B16-F10 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates. The cells were incubated at 37 °C for 16 h. For IFN-γ induction, MCF-7 cells were treated with 20 ng ml−1 IFN-γ or different concentration of Ponatinib and 20 ng ml−1 IFN-γ for 24 h. Similarly, for hypoxia induction, B16-F10 cells were treated with 100 µM CoCl2 or different concentration of Ponatinib and 100 µM CoCl2 for 24 h. Cells were scrapped and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min. The cell pellets were lysed by incubating in RIPA buffer for 10 min on ice. The suspension was sonicated for 5 cycles of 10 s pulse with 1 min intervals at 30% amplitude using a probe sonicator. The lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min and supernatants were collected. Total protein was estimated by Bradford colorimetric assay (Thermo Scientific™ Micro BCA™ Protein Assay Kit). Western blotting experiment was performed by incubating the PVDF membrane with anti-PD-L1 and anti-HIF-1α antibodies, followed by the HRP-tagged secondary antibody. β-actin was used as control for the analysis.

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were performed in triplicate. The results show a mean of at least three experiments ± 95% CI. Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism 6 and P values were calculated by the unpaired t test, one way ANOVA, and two way ANOVA multiple comparison tests. The significance of the difference between two groups were analysed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. The animals were randomised according to their body weight and tumour volume before the administration of drug or control to avoid any bias and analysis was blinded. All the experiments were performed in triplicates and minimum number of mice were 5/group.

Results

Ponatinib delayed the growth of B16-F10 melanoma and 4T1 breast tumour

The in vivo antitumour efficacy of Ponatinib was evaluated in mice bearing B16-F10 melanoma by injecting the Ponatinib intraperitoneally daily for 10 days (15 mg kg−1 body weight (BW) (Fig. 1a). Mice treated with Ponatinib showed significant delay in tumour growth compared to vehicle treated mice (Fig. 1b). At day 23, the mice treated with Ponatinib had a mean volume of 342.8 ± 44.54 mm3 versus 2514 ± 63.4 mm3 for mice received vehicle only (Unpaired t test, P < 0.0001, Ponatinib treated group compared with vehicle treated group, n = 5). No change in body weight of the mice was observed during the course of the experiment (Fig. 1c). At the end of the experiment, all the mice were sacrificed and the tumour weights were measured. The mean tumour weight was found 1.223 ± 0.1138 g, and 4.636 ± 0.2342 g, respectively, for the mice treated with Ponatinib, and the vehicle (Unpaired t test, P < 0.0001, Ponatinib treated group compared with control group, n = 5) (Fig. 1d). The above data clearly indicated that Ponatinib treatment is potent in delaying the tumour growth and reducing tumour weights as well.

Fig. 1. Tumour growth inhibition study in B16-F10 melanoma and 4T1 breast carcinoma model.

a The schematic diagram of experimental design. Tumour cells (B16-F10) were subcutaneously inoculated in the right flank of the mice on day 1. When the tumour volume reached 50–100 mm3, mice were received i.p. dose of Ponatinib (15 mg kg−1 BW, n = 5) or vehicle only (n = 5). b Change in tumour volume up to 23 days. Tumour volume was measured every alternate days till the end of the experiment (mean ± 95% CI, n = 5). c Body weight of mice were measured throughout the experiment. d Tumour weight on day 23. At the end of the experiment, the mice were sacrificed and the weight of excised tumours were analysed (mean ± 95% CI, unpaired t test, P < 0.0001, n = 5). P values for the Ponatinib relative to vehicle group is: ****P < 0.0001. e Schematic of dosing regimen in 4T1 tumour model. f Tumour volume was measured every other day for 18 days. g Mice body weight was measured throughout the course of study. h At day 18, mice were sacrificed and excised tumours were weighed (mean ± 95% CI, unpaired t test, P < 0.0001, n = 5).

To check that Ponatinib can show the anti-tumour efficacy across other tumour types, mice bearing orthotopic 4T1 tumour were injected thrice every alternate day with Ponatinib (15 mg kg−1 BW) (Fig. 1e). Similar delay in tumour growth was observed in mice bearing 4T1 tumour treated with Ponatinib compared to mice received vehicle only (Fig. 1f). At day 18, Ponatinib treated mice had a mean tumour volume of 102.7 ± 11.07 mm3 versus 601.4 ± 26.18 mm3 for mice received vehicle only (Unpaired t test, P < 0.0001, treatment group compared with vehicle treated group, n = 5). Similar to melanoma model, no change in body weight of the mice was observed throughout the course of study (Fig. 1g). At day 18, the mean tumour weight for the mice treated with Ponatinib, and the vehicle was found 0.128 ± 0.01828 and 0.43 ± 0.03728 g, respectively (Unpaired t test, P < 0.0001, Ponatinib-treated group compared with control group, n = 5) (Fig. 1h). The above data clearly indicates that Ponatinib can significantly delay the tumour growth in both B16F10 and 4T1 models.

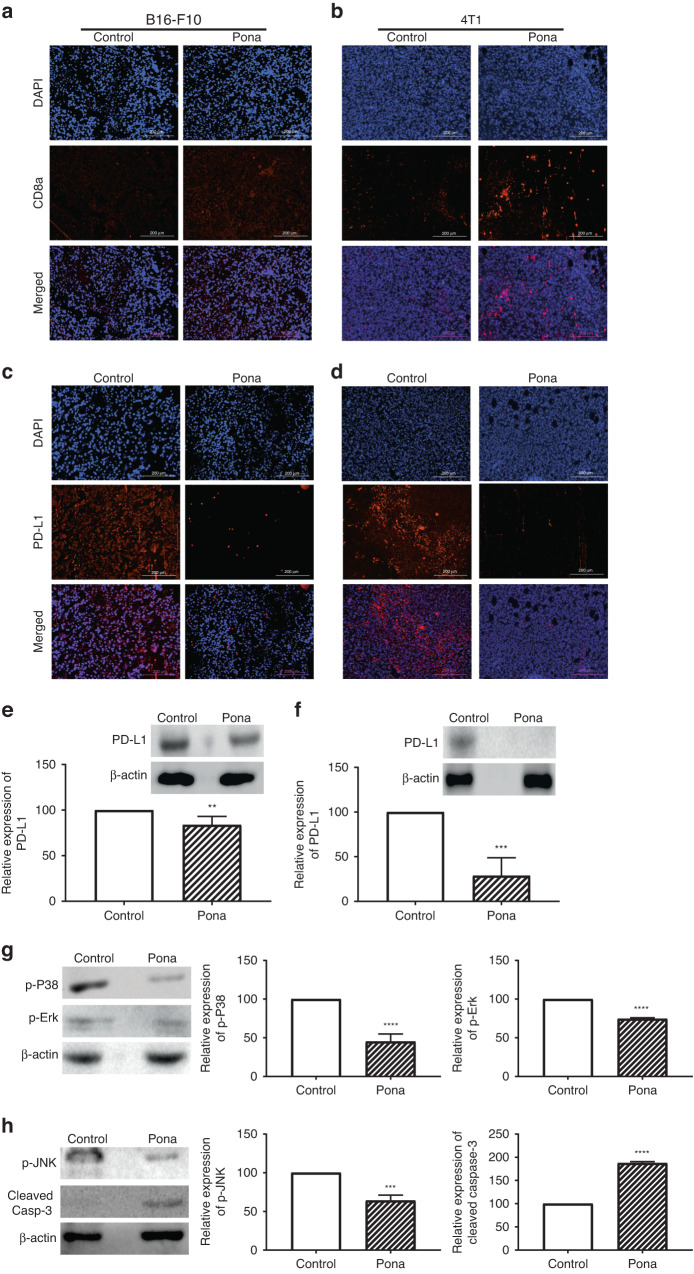

Ponatinib treatment enhanced the CD8 T cell infiltration in TME by downregulating PD-L1 and associated pathways

CD8 T cells plays a critical role in antitumour immunity as they can directly kill the tumour cells by releasing granzyme and perforin [20]. Hence to investigate that the delay in tumour growth by Ponatinib treatment is due to the antitumour immunity, we analysed the CD8 + T cell population in tumour. The population of tumour infiltrated CD8 + T cells was significantly increased in Ponatinib treated mice compared to the control group in both B16-F10 and 4T1 models (Fig. 2a, b, respectively).

Fig. 2. CD8 T cell infiltration and PD-L1 inhibition.

a, b At the end of the experiment, both B16-F10 and 4T1 tumours were excised and the infiltration of CD8 T cells were analysed by IHC. c, d Expression of PD-L1 in tumours was determined by IHC in both the models. e, f The expression of PD-L1 was confirmed by Western blot analysis of tumour lysates of B16-F10 and 4T1 bearing mice, respectively. Tumour PD-L1 expression in the Ponatinib-treated group was calculated as percentage change relative to the vehicle-treated group (mean ± 95% CI, unpaired t test, n = 3). g, h At day 23, tumours were collected from B16-F10-bearing mice treated with Ponatinib or vehicle only and western blot was performed with tumour lysates. Left panel show representative western blot images and the graphs in the right panel show the expression of proteins in treated group relative to control group. Protein levels; p-P38 and p-Erk (g), p-JNK and cleaved caspase-3 (h) are expressed as percentage change with respect to vehicle-treated mice and normalised to β-actin. Results were presented as mean ± 95% CI, unpaired t test, n = 3. P values for the Ponatinib-treated group relative to vehicle group, are represented as: ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01.

PD-L1 overexpression in tumour creates an immunosuppressive TME by interacting with PD-1 on tumour infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and impair their activation [21]. We hypothesised that Ponatinib can regulate the activity of CD8 + T cells by regulating the level of PD-L1. As shown in Fig. 2c, d, Ponatinib treatment significantly decreased the expression of PD-L1 in TME of B16-F10 and 4T1 respectively. We also analysed the expression of PD-L1 expression in tumour by Western blot and the data clearly demonstrated that Ponatinib treatment significantly reduced the level of PD-L1 in both B16-F10 and 4T1 tumours (Unpaired t test, P < 0.0005, treatment group compared with vehicle treated group, n = 3) (Fig. 2e, f respectively). These results suggest that the Ponatinib delayed the tumour growth by lowering the expression of PD-L1 in TME.

PD-L1 has been reported to induce tumour cell proliferation by increasing the phosphorylation of Erk, JNK and P38 proteins, which are members of the MAPK family and play an important role in the transduction of extracellular signalling, thus regulating several cellular functions such as cell proliferation, survival and differentiation [22, 23]. In order to test that the PD-L1 inhibition by BT11 can also inhibit the levels of phosphorylated proteins, we performed Western blot analysis of tumour lysate to determine the levels of p-P38, p-Erk, and p-JNK. As shown in Fig. 2g, h, the levels of p-P38, p-Erk, and p-JNK respectively were significantly reduced in the tumours of mice treated with Ponatinib compared to control group (Unpaired t test, P < 0.005, Ponatinib-treated group vs control group). The phosphorylated Erk is reported to play a role as a promoter of tumour cell proliferation, and their inhibition can induce the cleavage of caspase-3, as a marker of apoptosis [23, 24]. Hence we evaluated the level of cleaved caspase-3 in the tumour lysate. Western blot analysis showed that the cleaved caspase-3 expression was significantly increased in Ponatinib treated mice compared to the control (Unpaired t test, P < 0.0001 Ponatinib treatment vs control, n = 3) (Fig. 2h).

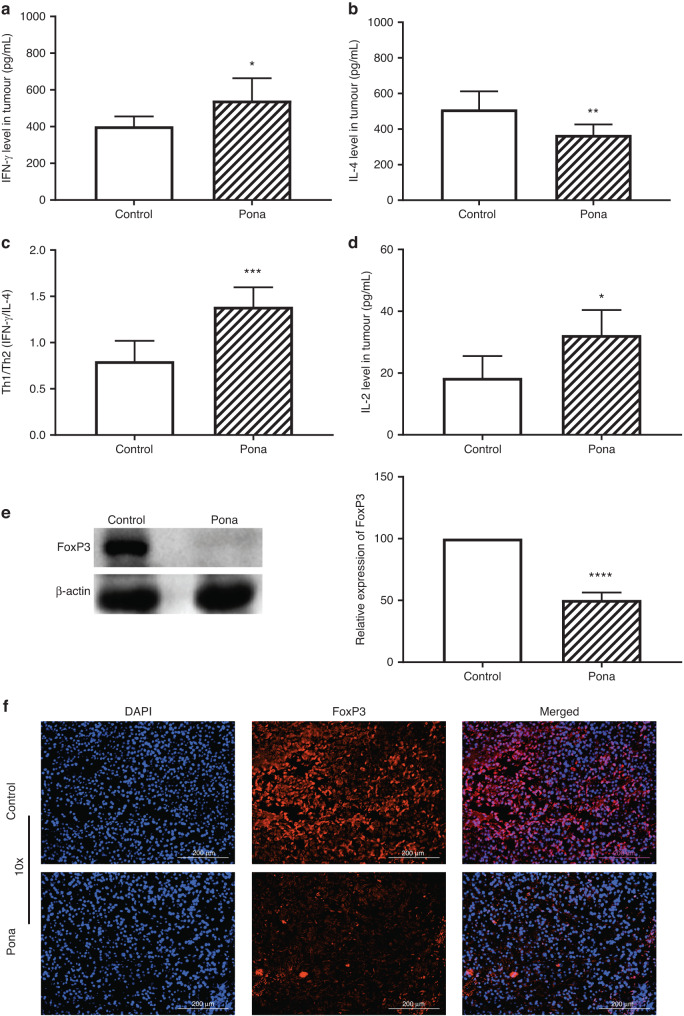

Ponatinib modulates tumour microenvironment (TME) by regulating the Th1/Th2 balance, lowering FoxP3 expression and depleting TAMs

Since the immunosuppressive TME limits the efficacy of immunotherapy, hence modulation of TME is critical to achieve a successful antitumour immunity [25]. Previous clinical data indicates that an imbalance of Th1/Th2 is associated with inhibition of host antitumour immunity and dominant Th1 response has shown a higher survival in cancer patients [26]. Th2 cytokines such as IL-4, IL-10 help the cancer cells to proliferate and survive by suppressing the immune response against tumour while Th1 cytokines including IFN-γ, TNF-α induce the antitumour immunity [27]. Hence, to investigate the Th1/Th2 balance, IFN-γ (cytokine secreted by Th1) and IL-4 (secreted by Th2) in tumour were analysed. ELISA data showed that IFN-γ was significantly higher whereas IL-4 was significantly reduced in mice bearing B16-F10 tumour and were treated with Ponatinib (Unpaired t test, P < 0.05 Ponatinib treatment vs control, n = 3) (Fig. 3a, b). Similar results were observed in 4T1 tumour model where the IFN-γ level was significantly increased while IL-4 levels were significantly lowered (Fig. S1) with Ponatinib treatment versus control. Furthermore, Th1/Th2 were significantly increased in both B16-F10 (Fig. 3c), and 4T1 (Fig. S1) tumours treated with Ponatinib when compared to vehicle treated group (Unpaired t test, P = 0.0008, Ponatinib treatment vs control, n = 3). These results clearly indicate that Th1/Th2 balance was significantly shifted towards Th1 in both B16F10 and 4T1 tumour models.

Fig. 3. Modulation of TME by Ponatinib treatment.

a At day 23, mice bearing B16-F10 tumours were sacrificed and the tumours were excised. The modulation of TME was determined by measuring, IFN-γ (a), IL-4 (b), and IL-2 (d) levels by ELISA (mean ± 95% CI, unpaired t test, n = 4). c The ratio of Th1 vs Th2 was determined by calculating IFN-γ/IL-4 (mean ± 95% CI, unpaired t test, n = 4). e FoxP3 level was evaluated by performing Western blot of tumour lysate. Left panel shows representative Western blot images and the graph in the right panel shows the expression of FoxP3 in treated group relative to control group (mean ± 95% CI, n = 3). Unpaired t test was performed for statistical analysis (****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.0005, **P < 0.005, *P < 0.05). f Tumour FoxP3 expression was confirmed by IHC. Scale bar 200 μm.

IL-2 is one of the key cytokine which plays a critical role in growth and differentiation of T cells [28]. It is known to mediate the tumour regression by modulating TME, hence the level of IL-2 was analysed in tumour and we found that IL-2 was significantly higher in the tumour of Ponatinib treated mice when compared to vehicle treated group in both B16-F10 (Fig. 3d) and 4T1 (Fig. S2) tumour models (Unpaired t test, P < 0.0001, n = 3).

Next to evaluate the effect of Ponatinib on regulatory immunity, we analysed the expression of FoxP3 in the tumour. FoxP3 is a marker for regulatory T cells (Tregs) in TME which suppress the antitumour immunity by inhibiting the T cell activation [29]. Hence we analysed the expression of FoxP3 in tumour and Western blot data showed that the FoxP3 level was significantly reduced in the tumour of the mice treated with Ponatinib compare to the mice received vehicle only in both B16-F10 (Unpaired t test, P = 0.0001) (Fig. 3e) and 4T1 (Unpaired t test, P = 0.005) (Fig. S3) tumour models. FoxP3 expression in tumours were also confirmed by IHC and as shown in Fig. 3f, it was drastically decreased in Ponatinib treated tumour when compared to control. The reduced FoxP3 expression in tumour suggests that Tregs activity might be lowered in Ponatinib treated mice.

In solid tumours TAMs promote the tumour progression and high TAMs infiltration is correlated with poor survival by creating an immunosuppressive TME [17, 30]. Hence we analysed whether Ponatinib also depleted the TAMs infiltration in TME, we analysed the population of F4/80+ cells (indicator of TAMs) by IHC. As shown in Fig. S4, F4/80+ cells were significantly diminished in the TME treated with Ponatinib in both B16-F10 and 4T1 tumour models.

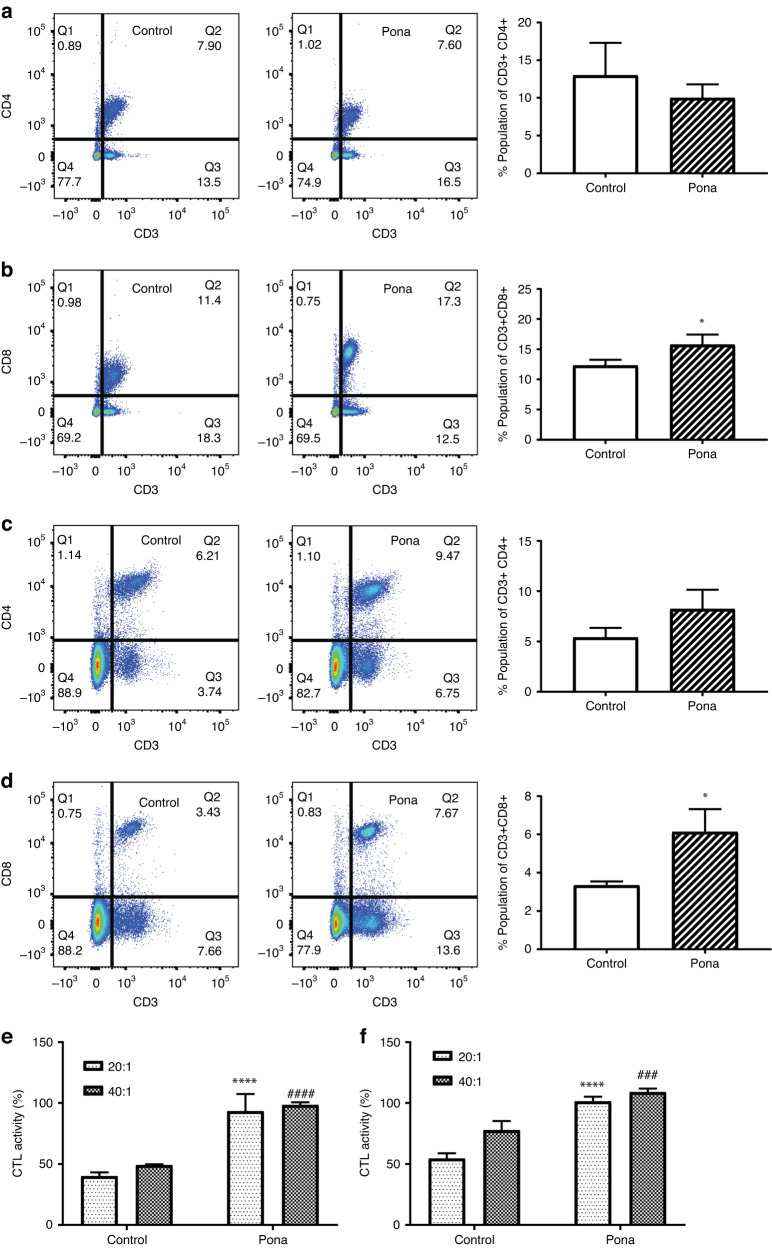

Ponatinib regulates the systemic immunity by enhancing the T cells population and CTL activity in spleen and inhibiting PD-L1 expression in spleen and serum

In addition to the immune response in TME, the continuous communication with the periphery is critical to achieve a successful immunotherapeutic outcome as T cell priming events occur in lymphoid organs [31, 32]. Recent clinical studies have shown the importance of peripheral immune cells to an effective antitumour immunity [31]. Hence, to get a thorough understanding of peripheral immune responses induced by Ponatinib, we evaluated T cell subpopulations and CTL activity of splenocytes. There was no significant change in CD3 + CD4 + T cells observed in either B16-F10 or 4T1 models (Fig. 4a, c respectively). However, the population of CD3 + CD8 + T cells were significantly higher in the spleen of Ponatinib treated mice in both B16-F10 (Fig. 4b) and 4T1 (Fig. 4d) tumour models (15.77 ± 0.9735, n = 3 and 6.133 ± 0.6888, n = 3 respectively) compare to the control mice (12.3 ± 0.5508, n = 3 in B16-F10 and 3.333 ± 0.1202, n = 3 in 4T1 tumour model) (Unpaired t test, P < 0.01, n = 3). Next we evaluated the cytotoxic activity of splenocytes (E—Effector cells) against B16-F10 cells (T—Target cells). The CTL activity of splenocytes at E/T ratios of 20:1 and 40:1 were increased in Ponatinib treatment group in B16-F10-bearing mice than the mice received vehicle only (Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, P < 0.0001 at every ratio, n = 3) (Fig. 4e). Similar results were observed in 4T1 tumour model as the CTL activity of splenocyte was found significantly higher in Ponatinib treated mice and with both E/T ratios (Fig. 4f) (Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, P < 0.0001 for each ratio, Ponatinib treated group vs control).

Fig. 4. Ponatinib enhanced T cell populations and CTL activity.

a–d Spleens were collected from each group (n = 3) at the end of the experiment, and the single-cell suspensions were prepared. Cell counts for CD3 + CD4+ and CD3 + CD8 + T cells in B16-F10 (a, b) and 4T1 (c, d) tumour models were determined by flow cytometry. e, f The cytotoxic activity of splenocytes were measured by co-culturing respective splenocytes with B16-F10 cells (e) and 4T1 (f) at E/T ratio of 20:1 and 40:1. The results were presented as mean ± 95% CI (Sidak’s multiple comparisons test). (*P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001, ####P < 0.0001, ###P < 0.0005).

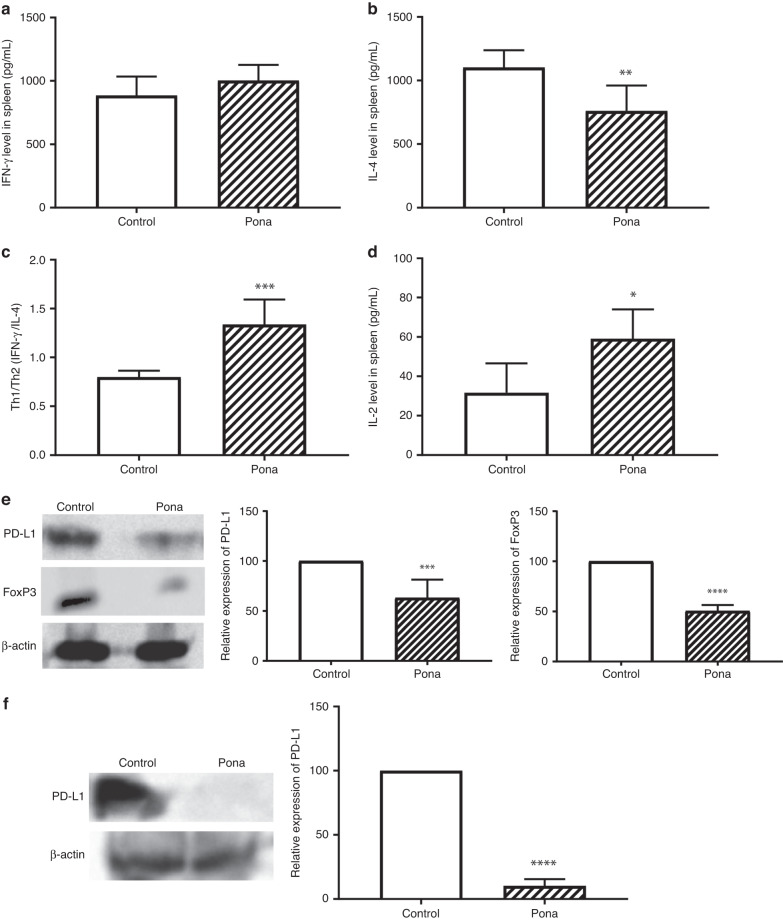

Next to investigate whether Ponatinib balance the systemic Th1/Th2 ratio as well, we evaluated the IFN-γ and IL-4 levels in spleen. As shown in Fig. 5a, there was no significant change in IFN-γ level whereas IL-4 was significantly decreased in the spleen of B16-F10 tumour model (Unpaired t test, P < 0.05, n = 4) (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 5c, Th1/Th2 were significantly increased in spleen of mice treated with Ponatinib when compared to vehicle treated group (Unpaired t test, P < 0.001, Ponatinib treatment vs control, n = 4) in B16-F10-bearing mice. The increase in Th1/Th2 ratio shows that in spleen the Th1 population was dominated which is required for an activated immune response. CD4 + T cells release IL-2 which helps in the T cell differentiation into mature CD4+ and CD8 + T cells to enhance the adaptive immunity [30], hence we determined the IL-2 levels in spleen. As shown in Fig. 5d, IL-2 levels were significantly elevated in mice treated with Ponatinib compared to the control group (Unpaired t test, P < 0.05, n = 4). Similar results were observed in the spleen of 4T1 tumour model as well (Fig. S5).

Fig. 5. Modulation of splenic microenvironment.

At the end of the experiment, mice were sacrificed and the spleens were excised. Various cytokines responsible for splenic immunity were analysed by ELISA: IFN-γ (a), IL-4 (b), and IL-2 (d) levels (mean ± 95% CI, n = 4). c The ratio of Th1 vs Th2 was analysed by calculating IFN-γ/IL-4 (mean ± 95% CI, n = 4). e PD-L1 and FoxP3 level was evaluated by performing Western blot of spleen lysate. Left panel shows representative Western blot images and the graph in the right panel shows the expression of PD-L1 and FoxP3 in Ponatinib treated group relative to control group (mean ± 95% CI, n = 3). f FoxP3 expression in serum was analysed by Western blot, left panel shows the representative Western blot image, while the graph in right panel shows the relative expression of PD-L1 in treated group (mean ± 95% CI, n = 3). Unpaired t test was performed for statistical analysis (****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.0005, **P < 0.005, *P < 0.05).

Further to analyse that Ponatinib affect the systemic PD-L1 expression, we evaluated the PD-L1 expression in spleen. Western blot data showed that PD-L1 is significantly decreased in spleen of mice treated with Ponatinib compared to control group (Unpaired t test, P < 0.005) (Fig. 5e). Similar to tumour, FoxP3 levels in spleen indicate the activity of Tregs which limit the antitumour immunity by diminishing the CD8 T cell activity [33]. Western blot analysis of spleen lysate showed that Ponatinib inhibited the FoxP3 expression in spleen (Fig. 5e).

Several studies showed that presence of soluble PD-L1 in human serum released from PD-L1-positive cells and immune cells and increased serum PD-L1 levels is known for poor treatment responses in cancer patients [34]. Hence we determined the PD-L1 level in serum and a significant decrease in serum PD-L1 level was observed in the mice treated with Ponatinib when compared to control (P < 0.001, Ponatinib treated group vs control group, n = 3) (Fig. 5f). This data clearly demonstrated that Ponatinib can lower the expression of cell surface and soluble PD-L1 as well.

Ponatinib inhibits IFN-γ and hypoxia induced PD-L1 overexpression via regulating HIF-1α

To explore the molecular mechanism by which Ponatinib regulate PD-L1 expression in tumour microenvironment, we performed RNA-sequencing to identify the signalling pathways altered by Ponatinib in tumour. We found 322 genes and 1124 genes were significantly upregulated and downregulated respectively upon treatment with Ponatinib (Fig. 6a). To identify the underlying biological processes that are affected by Ponatinib treatment, we further performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and the bubble plot of the enriched Reactome pathway demonstrated that the downregulated genes were significantly enriched in “gene expression and transcription” related genes (Fig. 6b). In particular, GSEA showed that HIF-1α was significantly downregulated in tumour with Ponatinib treatment compared to vehicle treatment (Table 1, Supporting Information). Previous studies have reported that HIF-1α transcriptionally regulates PD-L1 expression by binding on hypoxia response elements (HRE) of its promoter [8, 35]. Hence we hypothesised that Ponatinib could inhibit the PD-L1 expression via the regulation of HIF-1α expression. To test this hypothesis, we analysed the expression of HIF-1α in Ponatinib treated tumours. IHC data showed that HIF-1α was drastically decreased in both B16-F10 and 4T1 tumour models (Fig. 6c) which is correlated to the PD-L1 expression in tumour as shown in Fig. 2c, d respectively. These data suggested that Ponatinib may inhibit PD-L1 level via regulating HIF-1α expression in both B16-F10 and 4T1 tumour models.

Fig. 6. Ponatinib inhibits the PD-L1 expression via HIF-1α downregulation.

a Volcano plot of expressed genes of Ponatinib treated group compared to control group. The y axis illustrates −log 10 P values, and the x axis corresponds to a log 2-fold change of gene expression between the treated and control groups. The red and blue points represent statistically significant genes (P < 0.05). The genes represented in black (NS) and green (logFC) points denote the ones that were not statistically significant and were not considered for downstream analyses. b Bubble plot of the enriched Reactome pathway terms for genes upregulated or downregulated in B16-F10 tumours isolated from mice treated with Ponatinib or vehicle control. Size and colour of the bubbles are based on the number of genes and −log10 of FDR values, respectively. c At the end of experiment, mice bearing B16-F10 tumours were sacrificed and expression of HIF-1α in tumour sections were analysed by IHC. d MCF-7 cells were treated with IFN-γ followed by Ponatinib treatment for 24 h. Cells were lysed and expression of PD-L1 and HIF-1α were analysed by Western blot. Left panel shows representative Western blot images and the graph in the right panel shows the expression of PD-L1 and HIF-1α in treated groups relative to control group (mean ± 95% CI, n = 3). e B16-F10 cells were treated with CoCl2 to mimic the hypoxia and then treated with Ponatinib. After 24 h, cells were lysed and PD-L1 and HIF-1α expression were determined with Western blot analysis (mean ± 95% CI, n = 3). Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used for statistical analysis. (****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.0005, **P < 0.005, *P < 0.05).

To prove whether Ponatinib can inhibit PD-L1 expression in human cancer cells in vitro, we added IFN-γ to the MCF-7 cells to induce the PD-L1 overexpression and treated with different concentrations of Ponatinib. Western blot data revealed that IFN-γ treatment induced the expression of PD-L1 and HIF-1α significantly (Fig. 6d). Further Ponatinib treatment lowered the expression of HIF-1α in a dose dependent manner and hence PD-L1 was also inhibited in a similar fashion (Fig. 6d). We confirmed the effect of Ponatinib treatment on the expression of PD-L1 by immunofluorescence and as shown in Fig. S6, Ponatinib significantly inhibited the IFN-γ induced expression of PD-L1 in MCF-7 cells. Further to confirm that Ponatinib also inhibits the expression of PD-L1 induced by hypoxia via regulation of HIF-1α, we mimicked the hypoxic condition in B16-F10 cells by pretreating them with CoCl2. The cells were then treated with different concentration of Ponatinib. As shown in Fig. 6e, the treatment of CoCl2 significantly increased the expression of HIF-1α and hence it upregulated the PD-L1 expression as well. Furthermore, Ponatinib lowered the HIF-1α level and PD-L1 expression in a similar fashion. Taken together, these data suggested that Ponatinib can lower the PD-L1 expression induced by either IFN-γ or hypoxia via inhibition of HIF-1α.

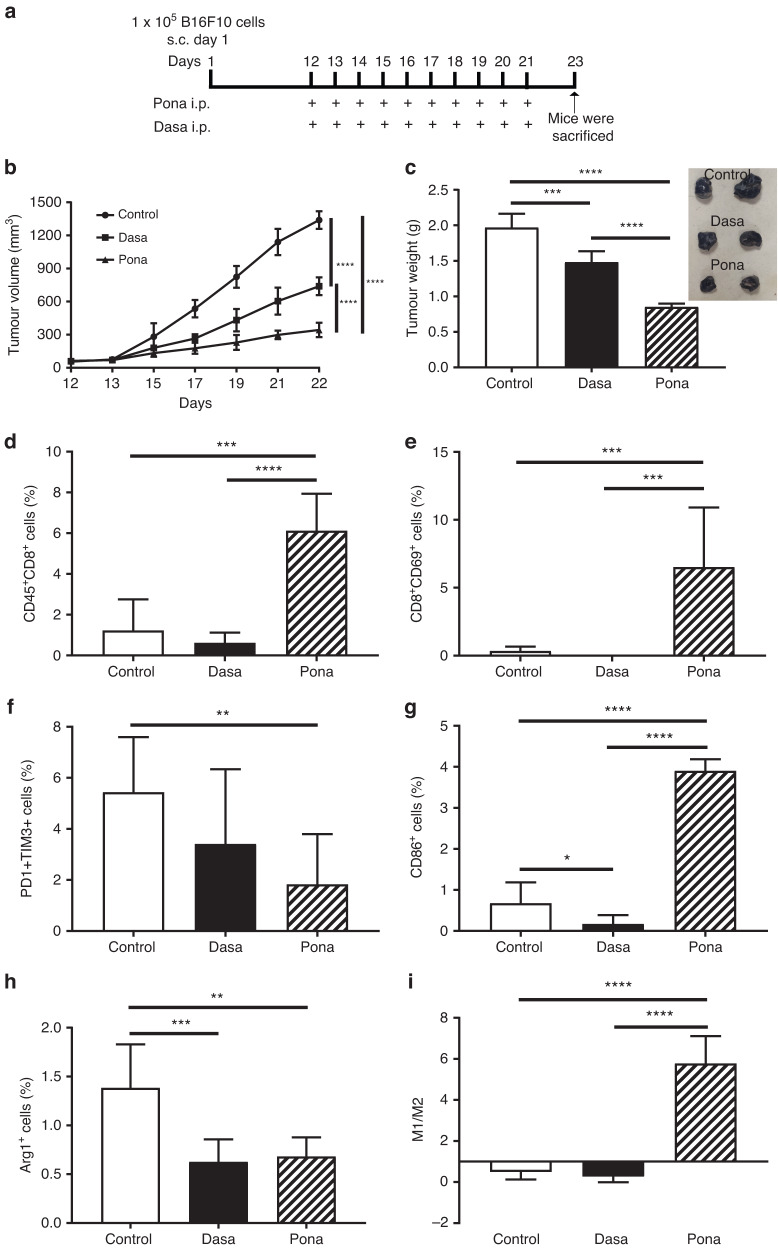

Modulation of TME by Ponatinib in comparison with Dasatinib

Previous reports have shown that TKIs including Ponatinib, Dasatinib etc. inhibit early signalling in T cell proliferation and activation in a dose dependent manner [36, 37]. However, as shown in Fig. 2, Ponatinib inhibited PD-L1 expression which indicated that Ponatinib might inhibit the exhaustion of T cells in later stages in peripheral tissues and tumour. PD-L1-related T cell apoptosis is one of several crucial mechanisms of T cell deletion in tumour and a higher PD-L1 expression is associated with lower number of T cells infiltration [38]. To substantiate the hypothesis that Ponatinib mediated antitumour efficacy is due to PD-L1 down-regulation induced T cell proliferation and activation, we used Dasatinib as control and evaluated its antitumour efficacy in tumour models (Figs. 7a and S8). As shown in Fig. 7b, Ponatinib was more potent than Dasatinib in inhibiting the growth of B16F10 melanoma tumour. A significant decrease in tumour weights were observed with Dasatinib treatment when compared to control, however Ponatinib reduced the weight significantly more than Dasatinib (Fig. 7c). Interestingly, when compared to control, Dasatinib inhibited the CD8 T cell infiltration (Fig. 7d) and its activation in tumour (Fig. 7e and S7). Interestingly, in our study, we demonstrated that Ponatinib treatment significantly increased the infiltration and activation of CD8 T cells compared to control (Figs. 7d, e and S7). Inhibition of PD-L1 not only induces the activated T cell infiltration but also reduces the population of exhausted T cells which are identified by the co-expression of PD1 and TIM3, showed impaired function after stimulation [39, 40]. Abundance of these cells in tumour have shown aggressiveness and high risk of relapse in cancer patients [41]. Hence, to check whether Ponatinib treatment inhibited the exhaustion of CD8 T cells in tumour, we analysed PD1+TIM3+ CD8 T cells in tumour and as shown in Fig. 7f, Ponatinib treatment significantly lowered the population when compared to control and Dasatinib (Fig. S7).

Fig. 7. Modulation of TME by Ponatinib in comparison with Dasatinib.

a Schematic diagram of experimental design. Tumour cells (B16-F10) were subcutaneously inoculated in the right flank of the mice on day 1. When the tumour volume reached 50–70 mm3, mice were received i.p. dose of Ponatinib or Dasatinib (15 mg kg−1 BW, n = 5), or vehicle only (n = 5). b Change in tumour volume up to 22 days. Tumour volume was measured every alternate days till the end of the experiment (mean ± 95% CI, n = 5). c Tumour weight on day 23. At the end of the experiment, the mice were sacrificed and the weight of excised tumours were analysed (mean ± 95% CI, n = 5). d–i Tumours were processed into single-cell suspension and the immune cell populations were analysed by flow cytometry (mean ± 95% CI, n = 5). d CD45+CD8+ cells. e CD8+CD69+ cells. f PD1+TIM3+ among CD8+ cells. g CD86+ cells. h F4/80+Arg1+ cells. i M1 vs M2 plotted by calculating CD86+ cells vs Arg1+ cells. (One-way ANOVA was performed for statistical analysis (****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001 **P < 0.01, and *P < 0.05).

To investigate whether these results would translate across tumour types, we analysed and compared the in vivo efficacy in GL261 glioblastoma model. Figure S8 demonstrated that Ponatinib and Dasatininb showed similar results as observed in B16F10 model.

T cell exhaustion and suppression are also largely regulated by M2 type TAMs having PD-L1 overexpression [42]. In our study, we observed that Ponatinib treatment significantly increased M1 macrophages (Fig. 7g) and depleted M2 macrophages (Fig. 7h) whereas both M1 and M2 population were significantly lowered with Dasatinib treatment compared to control (Figs. 7g, h and S9). Moreover, Ponatinib significantly increased M1 vs M2 ratio and a dominated M1 population was observed in tumour whereas Dasatinib and control group showed a dominated M2 population (Fig. 7i).

Further we also analysed T cell status in spleen of mice bearing B16F10 tumour and treated with either Ponatinib or Dasatinib. As shown in Fig. S10, Dasatinib significantly lowered the activated T cell population when compared to control, whereas a significant increase in activated CD8 T cells were observed with Ponatinib treatment.

Discussion

PD-L1 overexpression is associated with poor prognosis in many cancers including lung cancer, ovarian cancer [43], melanoma, and renal cell cancer [44]. Previous studies showed that PD-L1 promoted the growth of cancer cells by inhibiting the CTL activity [45]. PDL-1 also increases the aggressiveness and invasiveness which results in reduced overall survival [46]. Overexpression of PD-L1 is associated with anticancer drug resistance which causes the immune evasion by cancer cells and hence helps in cancer progression [47]. Hence inhibiting the expression of PD-L1 could provide an effective antitumour immunity. PD-L1 expression is regulated by transcription factors, post-translation regulators or, epigenetic modifiers [8]. Hypoxia and IFN-γ are some of the crucial factors which induce the PD-L1 expression via various pathways such as regulating HIF-1α [9], PI3K/Akt and MAPK signalling [48, 49]. These signalling are also involved in promoting the cell survival and proliferation by inhibiting the apoptosis and cause the resistance to anticancer therapies [10, 11] by inducing the PD-L1. To this end, inhibiting these factors could deplete PD-L1 expression and regulate the cell proliferation which might improve the overall antitumour efficacy.

Ponatinib, a multi tyrosine kinase inhibitor is being used for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML). Earlier, we have shown that Ponatinib can bind to PD-L1 and induce antitumour activity [15]. In this study, first time we demonstrated that Ponatinib can inhibit the PD-L1 overexpression on tumour. In murine tumour models, inhibition of PD-L1 expression led to an enhanced antitumour immunity and an effective tumour regression. In this study, Ponatinib treatment showed significant delay in tumour growth compare to control and also significantly inhibited the PD-L1 expression. Ponatinib enhanced the infiltration of activated CD8 T cells and reduced the population of exhausted CD8 T cells in tumour which correlates with the delay of tumour growth.

Next to assess the effect of Ponatinib on the signalling pathways associated with PD-L1, we studied MAPK pathway which is known to regulate and induce the expression of PD-L1 and create an immunosuppressive environment by increasing the phosphorylation of Erk, MAPK and JNK [22]. In B16-F10 melanoma model, Ponatinib treatment significantly reduced the phosphorylation of Erk, MAPK and JNK. Previous studies have also reported that Erk and JNK inhibition resulted in suppression of PD-L1 expression [50]. The phosphorylated Erk promotes tumour cell proliferation and its inhibition induces the cleavage of caspase-3, a marker of apoptosis [23]. We observed that the levels of cleaved caspase-3 in tumour was increased with Ponatinib treatment. These data suggested that Ponatinib inhibits the expression of PD-L1 and its associated pathways.

To further investigate the antitumour immunity induced by Ponatinib, we analysed the level of different cytokines responsible for the modulation of TME. Under stimulation of different cytokines, CD4 T cells differentiates into Th1 subsets which secrets cytokines such as IL-12 and IFN-γ and Th2 subsets which produces IL-10 and IL-4 [27]. While Th1 is known to induce antitumour immunity, Th2 on the other hand promotes cancer progression [51]. It has been revealed that cytokines produced by Th1 and Th2 regulate the Th1/Th2 balance which plays a crucial role in an effective antitumour immunity [52]. In our study, Ponatinib also regulates the cytokines secreted by Th1 (IFN-γ) and Th2 (IL-4) cells and balanced Th1/Th2 by shifting it towards a dominant Th1 population which is crucial to get an effective antitumour immunity. Tregs is another important subset of T cell which is characterised by FoxP3 expression and dampens the antitumour immunity by suppressing the T cell activation [29]. Our data showed that FoxP3 levels were significantly decreased in Ponatinib treated mice which suggests the lower activity of Tregs. TAMs are one of the most abundant cell population in TME which makes it immunosuppressive and promote the tumour progression [30]. Depletion of TAMs have shown an enhanced CD8 T cell activities in solid cancers [17]. Interestingly, Ponatinib also depleted the TAMs infiltration in the TME of both B16-F10 and 4T1 tumours.

Tumour not only induces local immune exhaustion, but also causes peripheral immune dysfunction and for a long lasting antitumour immune response systemic immunity plays an equally important role as immune response within TME [31]. A localised immunity cannot exist without a continuous crosstalk with the peripheral immune cell such as secondary lymphoid organs where the immune cells priming events occur [53]. Hence, modulation of systemic immunity is equally important to achieve a satisfactory outcome. In this study, we observed that Ponatinib also induced a systemic immunity by increasing the CD8 T cells population and enhancing the CTL activity in spleen. Increased CTL activity in the spleen of Ponatinib treated mice suggested that Ponatinib induced the tumour specific immunity. Notably, IL-2 level was also increased in spleen of mice treated with Ponatinib which is the indication of T cell function and proliferation [28].

Previous studies demonstrated that splenic PD-L1 induces regulatory immune cells and promotes tumour growth [54]. In our study, we also observed that Ponatinib significantly reduced the PD-L1 expression in spleen. PD-L1 level in circulation is an important marker for poor overall and disease free survival and it was reported that mice with low serum PD-L1 level showed better survival than those with high serum PDL-1 [34]. We observed that Ponatinib decreases the serum PD-L1 drastically which is strongly associated with its expression.

Furthermore, RNA sequencing data of B16-F10 tumour revealed that genes related to transcription including HIF-1α were downregulated by Ponatinib treatment. Interestingly, HIF-1α is also known to regulate the PD-L1 expression by binding to HRE of its promoter [35] and it has been observed that hypoxia leads to PD-L1 upregulation on human or murine cancer cells which results into T cell apoptosis in a HIF-1α dependent fashion [9]. Moreover, inhibition of HIF-1α mediated PD-L1 expression enhanced the apoptosis of cancer cells which delayed the tumour growth and metastasis [55]. Our in vitro data demonstrated that Ponatinib inhibits the IFN-γ mediated PD-L1 overexpression on MCF-7 cells in a dose dependent manner by inhibiting HIF-1α. IFN-γ is an important inducer of PD-L1 and is known to upregulate the PD-L1 expression on tumour cells as well as immune cells [56]. Induced PD-L1 expression on cancer cells leads to resistance towards the inhibitory effect of IFN-γ. Inhibition of IFN-γ mediated PD-L1 overexpression have shown an enhanced anti-proliferative effect and hence an improved antitumour efficacy of IFN-γ [57]. Hypoxia is another crucial inducer of PD-L1 which is regulated via HIF-1α, hence we demonstrated whether Ponatinib inhibits the PD-L1 expression induced by hypoxia. We observed that Ponatinib inhibited the hypoxia induced PD-L1 overexpression on B16-F10 cells by inhibiting HIF-1α. Furthermore, our in vivo data revealed that HIF-1α is inhibited in both B16-F10 and 4T1 tumours which was correlated with PD-L1 expression in tumour. Since both IFN-γ and hypoxia are present in TME as well as in secondary lymphoid organs including spleen and lead to PD-L1 overexpression, immune cell dysfunction and exhaustion [56], Ponatinib can inhibit both IFN-γ and hypoxia induced PD-L1 expression and can prevent the immune exhaustion.

Previously, TKIs like Ponatinib and Dasatinib have shown to inhibit early signalling in T cell proliferation and activation in vitro [36, 37]. Hence, in this study, to prove that Ponatinib induced immunomodulation is due to the inhibition of PD-L1, we compared the in vivo immunomodulation efficacy of Ponatinib and Dasatinib in murine tumour models. Interestingly, Ponatinib increased the activated CD8 T cells and decreased the exhausted ones in the tumours whereas, Dasatinib failed to do so. Similarly, PD-L1 overexpression leads to the polarisation M1 to M2 TAMs which play a critical role in T cell exhaustion and suppression. Our study showed that Ponatinib inhibited the number of M2 TAMs and increased the population of M1, however Dasatinib treatment depleted both M1 and M2 population in tumour. These data collectively showed that Ponatinib mediated immunomodulation is due to PD-L1 inhibition which leads to increased activation and decreased exhaustion of CD8 T cell. Similar results were observed with GL261 glioblastoma model indicating that Ponatinib can inhibit PD-L1 overexpression and induce antitumour immunity across tumour types.

In conclusion, Ponatinib delayed the tumour growth in murine tumour models by inducing antitumour immunity via CD8 T cell infiltration in tumour and inhibiting the PD-L1 overexpression. It also modulated the TME by regulating the Th1 vs Th2 balance, depleting FoxP3 and TAMs. In tumour, Ponatinib enhanced the CD8 T cell infiltration and activation while reducing their exhaustion. Furthermore, Ponatinib modulated the systemic immunity by enhancing the tumour-specific CTL activity and CD8 T cell population in spleen. It inhibited the expression of PD-L1 in the spleen and as well as in serum. Finally, our data suggested that Ponatinib inhibited the induced PD-L1 overexpression via inhibiting HIF-1α. Induced PD-L1 expression is known to mediate acquired resistant to many therapies, including chemo [30], radiation and immunotherapies [10, 11]. Hence, Ponatinib can be used to inhibit PD-L1 overexpression to modulate the antitumour immunity in solid tumours and combining Ponatinib with other therapeutic regime which induces the expression of PD-L1 could avoid the acquired resistance and provide a better and durable therapeutic outcome.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the animal facility at National Institute of Immunology, Delhi for allowing to perform the animal studies. AB acknowledges IIT Delhi for providing her doctoral fellowship. We also acknowledge Mr. Amit Kumar from ILBS for helping in IHC slide preparation.

Author contributions

AB and JB conceived and designed the experiments. AB performed the experiments. AB and JB analysed the data and wrote the paper. SD and RT helped with the animal studies. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported through a project by Department of Biotechnology sanctioned to JB (Grant No. BT/PR29866/NNT/28/1586/2018) and a faculty interdisciplinary research project by Indian Institute of Technology Delhi (Grant No. MI02200G) (to JB).

Data availability

All the materials used to produce the data in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the animal experiments in this study has the ethical approval from the National Institute of Immunology institutional animal ethics committee.

Consent for publication

All authors have agreed to publish this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41416-023-02316-9.

References

- 1.Taube JM, Young GD, McMiller TL, Chen S, Salas JT, Pritchard TS, et al. Differential expression of immune-regulatory genes associated with PD-L1 display in melanoma: implications for PD-1 pathway blockade. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3969–76. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen J, Jiang C, Jin L, Zhang X. Regulation of PD-L1: a novel role of pro-survival signalling in cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:409–16. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jalali S, Price-Troska T, Bothun C, Villasboas J, Kim H-J, Yang Z-Z, et al. Reverse signaling via PD-L1 supports malignant cell growth and survival in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 2019;9:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41408-019-0185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gato-Cañas M, Zuazo M, Arasanz H, Ibañez-Vea M, Lorenzo L, Fernandez-Hinojal G, et al. PDL1 signals through conserved sequence motifs to overcome interferon-mediated cytotoxicity. Cell Rep. 2017;20:1818–29. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–64. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta HB, Clark CA, Yuan B, Sareddy G, Pandeswara S, Padron AS, et al. Tumor cell-intrinsic PD-L1 promotes tumor-initiating cell generation and functions in melanoma and ovarian cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2016;1:1–9. doi: 10.1038/sigtrans.2016.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Escors D, Gato-Cañas M, Zuazo M, Arasanz H, García-Granda MJ, Vera R, et al. The intracellular signalosome of PD-L1 in cancer cells. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2018;3:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41392-018-0022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zerdes I, Matikas A, Bergh J, Rassidakis GZ, Foukakis T. Genetic, transcriptional and post-translational regulation of the programmed death protein ligand 1 in cancer: biology and clinical correlations. Oncogene. 2018;37:4639–61. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0303-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barsoum IB, Smallwood CA, Siemens DR, Graham CH. A mechanism of hypoxia-mediated escape from adaptive immunity in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2014;74:665–74. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dovedi SJ, Adlard AL, Lipowska-Bhalla G, McKenna C, Jones S, Cheadle EJ, et al. Acquired resistance to fractionated radiotherapy can be overcome by concurrent PD-L1 blockade. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5458–68. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zippelius A, Schreiner J, Herzig P, Müller P. Induced PD-L1 expression mediates acquired resistance to agonistic anti-CD40 treatment. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:236–44. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, Moreno BH, Saco J, Escuin-Ordinas H, Rodriguez GA, et al. Interferon receptor signaling pathways regulating PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression. Cell Rep. 2017;19:1189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan FH, Putoczki TL, Stylli SS, Luwor RB. Ponatinib: a novel multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor against human malignancies. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:635. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S189391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Hare T, Shakespeare WC, Zhu X, Eide CA, Rivera VM, Wang F, et al. AP24534, a pan-BCR-ABL inhibitor for chronic myeloid leukemia, potently inhibits the T315I mutant and overcomes mutation-based resistance. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:401–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnwal A, Das S, Bhattacharyya J. Repurposing ponatinib as a PD-L1 inhibitor revealed by drug repurposing screening and validation by in vitro and in vivo experiments. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2023;6:281–9. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.2c00214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spranger S, Spaapen RM, Zha Y, Williams J, Meng Y, Ha TT, et al. Up-regulation of PD-L1, IDO, and Tregs in the melanoma tumor microenvironment is driven by CD8+ T cells. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:200ra116. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cassetta L, Kitamura T. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages as a potential strategy to enhance the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2018;6:38. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2018.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:1–21. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xia J, Gill EE, Hancock RE. NetworkAnalyst for statistical, visual and network-based meta-analysis of gene expression data. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:823–44. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durgeau A, Virk Y, Corgnac S, Mami-Chouaib F. Recent advances in targeting CD8 T-cell immunity for more effective cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2018;9:14. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yi M, Niu M, Xu L, Luo S, Wu K. Regulation of PD-L1 expression in the tumor microenvironment. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-01027-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Concha-Benavente F, Srivastava RM, Trivedi S, Lei Y, Chandran U, Seethala RR, et al. Identification of the cell-intrinsic and-extrinsic pathways downstream of EGFR and IFNγ that induce PD-L1 expression in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76:1031–43. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Passariello M, D’Alise AM, Esposito A, Vetrei C, Froechlich G, Scarselli E, et al. Novel human anti-PD-L1 mAbs inhibit immune-independent tumor cell growth and PD-L1 associated intracellular signalling. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49485-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuenda A, Rousseau S. p38 MAP-kinases pathway regulation, function and role in human diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2007;1773:1358–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Binnewies M, Roberts EW, Kersten K, Chan V, Fearon DF, Merad M, et al. Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat Med. 2018;24:541–50. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0014-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dushyanthen S, Beavis PA, Savas P, Teo ZL, Zhou C, Mansour M, et al. Relevance of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer. BMC Med. 2015;13:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0431-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiyomi A, Makita M, Ozeki T, Li N, Satomura A, Tanaka S, et al. Characterization and clinical implication of Th1/Th2/Th17 cytokines produced from three-dimensionally cultured tumor tissues resected from breast cancer patients. Transl Oncol. 2015;8:318–26. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang T, Zhou C, Ren S. Role of IL-2 in cancer immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1163462. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1163462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li C, Jiang P, Wei S, Xu X, Wang J. Regulatory T cells in tumor microenvironment: new mechanisms, potential therapeutic strategies and future prospects. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:1–23. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1085-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roux C, Jafari SM, Shinde R, Duncan G, Cescon DW, Silvester J, et al. Reactive oxygen species modulate macrophage immunosuppressive phenotype through the up-regulation of PD-L1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:4326–35. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1819473116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hiam-Galvez KJ, Allen BM, Spitzer MH. Systemic immunity in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21:345–59. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00347-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masopust D, Schenkel JM. The integration of T cell migration, differentiation and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:309–20. doi: 10.1038/nri3442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin Y-C, Chang L-Y, Huang C-T, Peng H-M, Dutta A, Chen T-C, et al. Effector/memory but not naive regulatory T cells are responsible for the loss of concomitant tumor immunity. J Immunol. 2009;182:6095–104. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shigemori T, Toiyama Y, Okugawa Y, Yamamoto A, Yin C, Narumi A, et al. Soluble PD-L1 expression in circulation as a predictive marker for recurrence and prognosis in gastric cancer: direct comparison of the clinical burden between tissue and serum PD-L1 expression. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:876–83. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-07112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noman MZ, Desantis G, Janji B, Hasmim M, Karray S, Dessen P, et al. PD-L1 is a novel direct target of HIF-1α, and its blockade under hypoxia enhanced MDSC-mediated T cell activation. J Exp Med. 2014;211:781–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weichsel R, Dix C, Wooldridge L, Clement M, Fenton-May A, Sewell AK, et al. Profound inhibition of antigen-specific T-cell effector functions by dasatinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2484–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-07-4393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flietner E, Wen Z, Rajagopalan A, Jung O, Watkins L, Wiesner J, et al. Ponatinib sensitizes myeloma cells to MEK inhibition in the high-risk VQ model. Sci Rep. 2022;12:10616. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-14114-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR, Tamura H, Hirano F, Flies DB, et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: a potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med. 2002;8:793–800. doi: 10.1038/nm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Granier C, Dariane C, Combe P, Verkarre V, Urien S, Badoual C, et al. Tim-3 expression on tumor-infiltrating PD-1(+)CD8(+) T cells correlates with poor clinical outcome in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2017;77:1075–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-16-0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roussel M, Le KS, Granier C, Llamas Gutierrez F, Foucher E, Le Gallou S, et al. Functional characterization of PD1+TIM3+ tumor-infiltrating T cells in DLBCL and effects of PD1 or TIM3 blockade. Blood Adv. 2021;5:1816–29. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sawada M, Goto K, Morimoto-Okazawa A, Haruna M, Yamamoto K, Yamamoto Y, et al. PD-1+ Tim3+ tumor-infiltrating CD8 T cells sustain the potential for IFN-γ production, but lose cytotoxic activity in ovarian cancer. Int Immunol. 2020;32:397–405. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxaa010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pu Y, Ji Q. Tumor-Associated Macrophages Regulate PD-1/PD-L1 Immunosuppression. Front Immunol. 2022;13:874589.. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.874589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamanishi J, Mandai M, Iwasaki M, Okazaki T, Tanaka Y, Yamaguchi K, et al. Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes are prognostic factors of human ovarian cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3360–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611533104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsu M-C, Hsiao J-R, Chang K-C, Wu Y-H, Su I-J, Jin Y-T, et al. Increase of programmed death-1-expressing intratumoral CD8 T cells predicts a poor prognosis for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:1393–403. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abiko K, Mandai M, Hamanishi J, Yoshioka Y, Matsumura N, Baba T, et al. PD-L1 on tumor cells is induced in ascites and promotes peritoneal dissemination of ovarian cancer through CTL dysfunction. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1363–74. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Massi D, Brusa D, Merelli B, Ciano M, Audrito V, Serra S, et al. PD-L1 marks a subset of melanomas with a shorter overall survival and distinct genetic and morphological characteristics. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:2433–42. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Massi D, Brusa D, Merelli B, Falcone C, Xue G, Carobbio A, et al. The status of PD-L1 and tumor-infiltrating immune cells predict resistance and poor prognosis in BRAFi-treated melanoma patients harboring mutant BRAFV600. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1980–7. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen S, Crabill GA, Pritchard TS, McMiller TL, Wei P, Pardoll DM, et al. Mechanisms regulating PD-L1 expression on tumor and immune cells. J Immunther Cancer. 2019;7:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0770-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gao Y, Yang J, Cai Y, Fu S, Zhang N, Fu X, et al. IFN‐γ‐mediated inhibition of lung cancer correlates with PD‐L1 expression and is regulated by PI3K‐AKT signaling. Int J Cancer. 2018;143:931–43. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang X, Zhou J, Giobbie-Hurder A, Wargo J, Hodi FS. The activation of MAPK in melanoma cells resistant to BRAF inhibition promotes PD-L1 expression that is reversible by MEK and PI3K inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:598–609. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Narsale A, Moya R, Davies JD. Human CD4+ CD25+ CD127hi cells and the Th1/Th2 phenotype. Clin Immunol. 2018;188:103–12. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nishimura T, Nakui M, Sato M, Iwakabe K, Kitamura H, Sekimoto M, et al. The critical role of Th1-dominant immunity in tumor immunology. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2000;46:S52–S61. doi: 10.1007/PL00014051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hanahan D, Coussens LM. Accessories to the crime: functions of cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:309–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bocanegra A, Blanco E, Fernandez-Hinojal G, Arasanz H, Chocarro L, Zuazo M, et al. PD-L1 in systemic immunity: unraveling its contribution to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade immunotherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:5918. doi: 10.3390/ijms21165918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou L, Cha G, Chen L, Yang C, Xu D, Ge M. HIF1α/PD-L1 axis mediates hypoxia-induced cell apoptosis and tumor progression in follicular thyroid carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:6461. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S203724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 56.Van Duijn A, Willemsen KJ, Van Uden NO, Hoyng L, Erades S, Koster J, et al. A secondary role for hypoxia and HIF1 in the regulation of (IFNγ-induced) PD-L1 expression in melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2022;71:529–40. doi: 10.1007/s00262-021-03007-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Minn AJ, Wherry EJ. Combination cancer therapies with immune checkpoint blockade: convergence on interferon signaling. Cell. 2016;165:272–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the materials used to produce the data in this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.