Abstract

COVID-19 may cause sudden serious illness, and relatives having to act on patients’ behalf, emphasizing the relevance of advance care planning (ACP). We explored how ACP was portrayed in newspapers during year one of the pandemic. In ‘LexisNexis Uni’, we identified English-language newspaper articles about ACP and COVID-19, published January–November 2020. We applied content analysis; unitizing, sampling, recording or coding, reducing, inferring, and narrating the data. We identified 131 articles, published in UK (n = 59), Canada (n = 32), US (n = 15), Australia (n = 14), Ireland (n = 6), and one each from Israel, Uganda, India, New-Zealand, and France. Forty articles (31%) included definitions of ACP. Most mentioned exploring (93%), discussing (71%), and recording (72%) treatment preferences; 28% described exploration of values/goals, 66% encouraged engaging in ACP. No false or sensationalist information about ACP was provided. ACP was often not fully described. Public campaigns about ACP might improve the full picture of ACP to the public.

Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) is aimed at enabling individuals to define their goals and preferences for future medical treatment and care, to discuss these with family and healthcare professionals, and to record and review these if appropriate (Rietjens et al., 2017). ACP has evolved from discussing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) preferences to an ongoing process of preparation for medical decision-making by exploring goals, values, treatment, and care preferences, discussing these with relatives and healthcare professionals, and preparing personal representatives for their role in case the patient becomes incapacitated (Heyland, 2020; Rietjens et al., 2017; Sudore & Fried, 2010). ACP can contribute to care being consistent with patients’ preferences (Brinkman-Stoppelenburg et al., 2014; Jimenez et al., 2018; Rietjens et al., 2017). Public campaigns have been used to increase awareness about ACP (Seymour, 2018). During the COVID-19 pandemic, ACP is increasingly prioritized by healthcare systems as a part of care (Curtis et al., 2020; Grant et al., 2021). A qualitative interview study among general practitioners in the Netherlands indicated that during the COVID-19 pandemic, they felt more aware of the importance of discussing ACP, and that their patients felt an increased need to discuss ACP due to messages about ACP in the media (Dujardin, 2021). However, people can also experience fear and uncertainty due to news messages about COVID-19 and the scarcity of healthcare and IC beds (Dujardin et al., 2021; Selman et al., 2020a; Sowden et al., 2021).

News media such as newspapers, television, or social media, are an important source of health information for the public since most people do not frequently meet their healthcare professionals (Schwitzer et al., 2005). News media may determine how people perceive formerly unknown phenomena (Schwitzer et al., 2005), such as ACP. Furthermore, both public and healthcare professionals use social media to discuss disease-related experiences and views, also about ACP (Cutshall et al., 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, preventive measures such as wearing facemasks and staying at home were communicated through mass-media channels such as television, radio, and newspapers (Maunder, 2021). Several studies have explored the news coverage of, for instance, end-of-life, palliative care, euthanasia, or voluntary assisted dying in the (news) media (Kis-Rigo et al., 2021; Rietjens et al., 2013; Van Gorp et al., 2021). A study by Mitchinson et al. (2021) focused on how barriers and attempts to delivery of end-of-life care during the pandemic and its impact on healthcare staff were described in printed media including newspapers and in social media. Nelson-Becker and Victor (2020) explored concerns and practices about dying alone during the COVID-19 pandemic and before in a newspaper analysis. Research has shown that the news about COVID-19 has increased public awareness of the relevance of ACP (Dujardin et al., 2021). However, misperceptions about ACP are common among the public (Grant et al., 2021), and such public misperceptions of ACP may be influenced by media attention during the COVID-19 pandemic (Grant et al., 2021).

It is unknown how ACP was represented to the public during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess how ACP was portrayed in newspapers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

Content analysis approach

We chose to analyze the portrayal of ACP in newspapers (traditional print newspapers, digitalized traditional print newspapers, and web-based newspapers) since newspapers are a common source of news for people of all ages. Furthermore, we focused on newspapers instead of social media, since although social media can be platforms for legitimate news information, systems to support a systematic search of the entire content of ‘legitimate social media’ are not available.

We used the content analysis method described by Krippendorff (2004); this method consists of six components; Unitizing, Sampling, Recording/Coding, Reducing, Inferring, and Narrating (Krippendorff, 2004). The first four components consider ‘Data making’, and the last two components consider the presentation of the results (Krippendorff, 2004). First, we searched for newspaper articles in LexisNexis Uni, an international digital archive of newspapers (Unitizing). We identified and selected articles about ACP and COVID-19, published in 2020 (1 January to 4 November) (Sampling). We extracted data using a pre-defined data extraction form (Recording or coding). We represented the data in the tables (Reducing data). We reflected on and inferred the meaning and implications of the data (Inferring). Lastly, we described the results in a narrative (Narrating) (Krippendorff, 2004).

Search strategy

We developed a search strategy in collaboration with the medical library of the Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam, aimed at finding articles in newspapers on ACP in relation to COVID-19. We analyzed articles that were published during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 (1 January to 4 November), because in this first year of the pandemic, there was still much uncertainty about COVID-19 (Koffman et al., 2020a, 2020b), and much media attention.

On 4 November 2020, we searched newspapers published between 1 January 2020, a start date just before the COVID-19 pandemic was announced to ensure we included all relevant articles from the start of the pandemic onwards (World Health Organization, 2020, 2022), to 4 November 2020. We searched for articles in newspapers (traditional print newspapers, digitalized traditional print newspapers, and web-based newspapers) that contained information about both ACP and COVID-19; written in English, in LexisNexis Uni, an international digital archive of newspapers. We used the terms “advance care planning” and different versions of the term “COVID-19”, for example, “coronavirus”, and “SARS-CoV-2”. A search in the digital newspaper archive ‘ProQuest’ did not result in additional articles. We included news reports, opinion articles, letters to the editor and interviews.

To compare how often ACP was described in newspaper articles in 2020 versus before the pandemic, we also counted the total number of published articles using the term “advance care planning” in 2019. Supplemental File 1 describes the search strategies.

Article selection

Two researchers (DS and ML) independently screened the articles adhering to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were: (1) The article is published on or after 1 January 2020; (2) The article is written in English; (3) The article is a newspaper article or web-based newspaper publication; and (4) The article contains information about both ACP and COVID-19. The exclusion criteria were: (1) The article is a duplicate (based on full-text) – where we had evidence it had been published more than once in the same or in different newspapers; and (2) The article is a news update or liveblog, referring to the original article. When DS and ML were unable to reach a consensus about inclusion or exclusion, other authors were consulted (JACR, IJK). Any disagreements were discussed to reach a consensus.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed by ML and DS using a pre-defined data extraction form that was based on studies on ACP and media analyses (Rietjens et al., 2013; van der Smissen et al., 2020), and was refined through pilot testing with 20 articles. When DS and ML were unable to reach a consensus on the data extraction, other authors were consulted (JACR, IJK). We registered the article characteristics, including the name of the newspaper, country of publication, date of publication, the title of the article, word count, article type, and the type of author (e.g., journalist, researcher, healthcare professional). In addition, we registered the types of the newspaper: national or regional; broadsheet/high-quality newspapers (typically containing more serious perspectives of major news stories), middle-market (typically containing important news events as well as entertainment news), or tabloid newspapers (typically containing politically diverse content, some of which may be considered sensationalist) (based on the distribution of the quality of newspapers from previously conducted media analyses (Hayes et al., 2007; Nimegeer et al., 2019; Patterson et al., 2016; Reintjes et al., 2016). Furthermore, we extracted the setting described in the article and whether the article concerned specific populations. In addition, we registered whether the article provided a definition of ACP, and whether it contained the key elements of ACP as indicated in the consensus definition of ACP; the exploration, discussion and recording of treatment and care preferences (Rietjens et al., 2017). Finally, we extracted whether reasons were provided to consider engagement in ACP. We used the software ‘Microsoft Excel’ during the data extraction and analysis of the data.

Results

Inclusion of newspaper articles

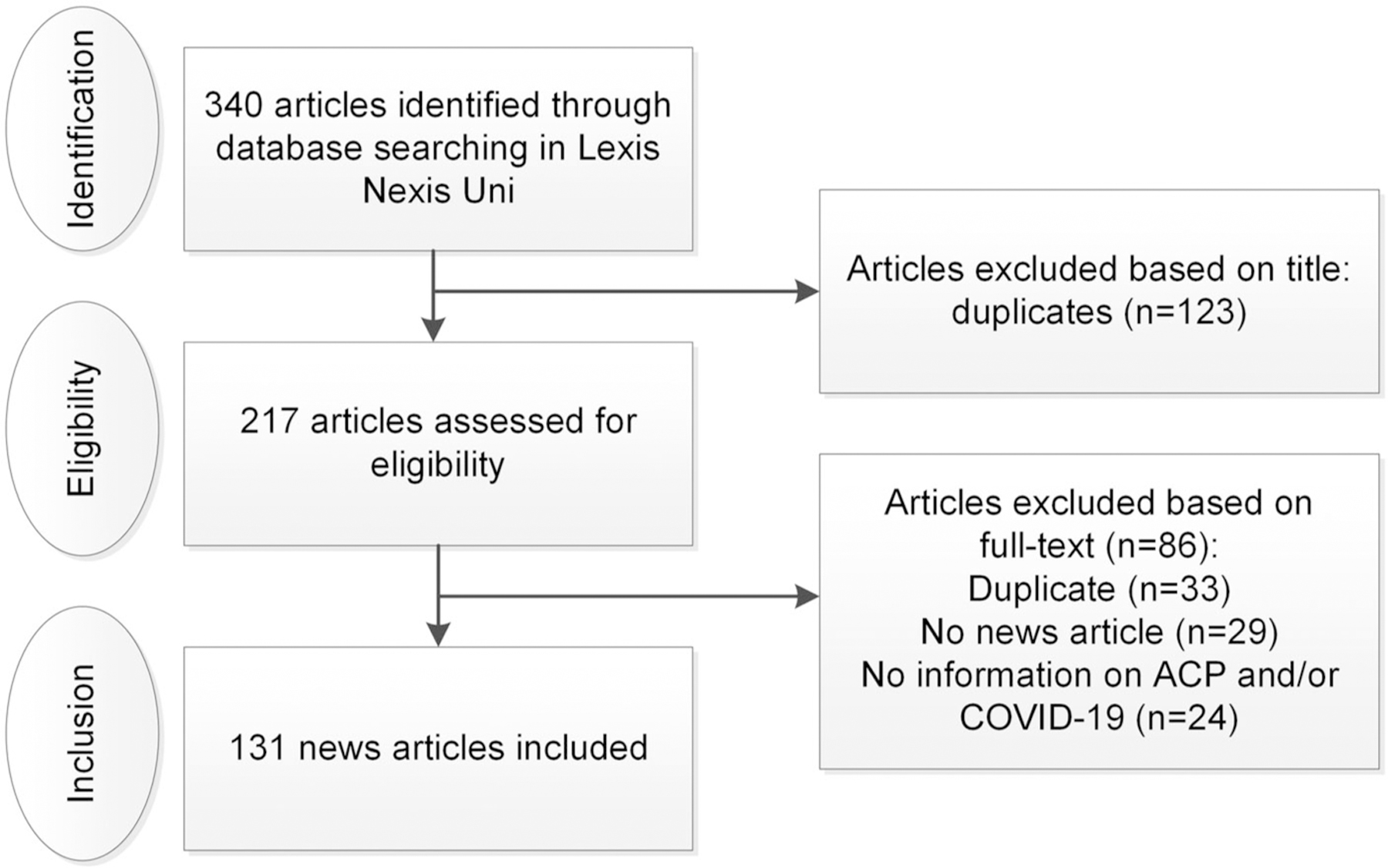

We identified 340 newspaper articles about both ACP and COVID-19. After removing duplicates, 217 articles were assessed for eligibility of which 86 articles were excluded (Figure 1), resulting in 131 included articles. Forty-seven of the 131 included articles were published at least twice (in the same country).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the inclusion of newspaper articles.

In 2020, 473 articles using the term “advance care planning” were published. This compared to 364 articles in 2019, prior to the pandemic.

Article characteristics

Of the 131 newspaper articles, most were published in the United Kingdom (UK) (n = 59; 45%), followed by Canada (n = 32; 24%), and the United States (US) (n = 15; 11%). Most articles were published in April 2020 (72 articles). In the remaining months, 10 articles or less per month were published. The mean number of article words was 545 (range: 80–3113 words). Most articles were news reports (n = 102; 78%) or opinion articles (n = 22; 17%). Of the 102 news reports, 65 cited professionals (50%), including healthcare professionals, government spokespersons or researchers; six cited patients, family, or the general public (5%), and 17 cited both professionals and patients, family, or the general public (13%). Articles were mainly authored by journalists (n = 89; 68%); 20 were authored by healthcare professionals (15%). About half (69, 53%) of the articles were published in national newspapers. The national newspapers were broadsheet/high-quality newspapers (n = 44, 34%), middle-market newspapers (5, 4%) or tabloid newspapers (n = 14, 11%), for six newspapers the type was unknown, see Supplemental File 2.

Of the 131 included newspaper articles, 47 (36%) focused on nursing homes, hospitals (n = 29, 22%), general practice (20, 15%) or intensive care units (n = 14, 11%). Furthermore, articles included announcements of the government (e.g., about COVID-19 measures) (n = 49, 37%), legal matters (e.g., about rules and laws related to ACP) (n = 25, 19%) and financial matters (e.g., about costs or funds in healthcare in general, or about getting financial matters in order) (n = 9, 7%).

Several articles mentioned specific populations including residents of nursing homes and care homes (n = 37; 28%), older adults (n = 10; 8%), and vulnerable people (this was mentioned in relation to older adults, people with disabilities or care home residents, patients with comorbidities) (n = 13; 10%). Table 1 presents the characteristics of the 131 included newspaper articles.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the newspaper articles that referred to advance care planning and COVID-19 (n = 131).

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| United Kingdom | 59 (45) |

| Canada | 32 (24) |

| United States | 15 (11) |

| Australia | 14 (11) |

| Ireland | 6 (5) |

| Other: Uganda (1), India (1), New Zealand (1), Israel (1) and France (1) | 5 (4) |

| Article type | |

| News report | 102 (78) |

| Citing professionals (e.g., healthcare professionals, government spokesperson, researcher) | 65 (50) |

| Citing patient/family/public | 6 (5) |

| Citing both professionals and patients, family, or the general public | 17 (13) |

| Opinion articles | 22 (17) |

| Letters to the editor | 6 (5) |

| Interview | 1 (1) |

| Author | |

| Journalist | 89 (68) |

| Healthcare professional | 20 (15) |

| Healthcare / ACP organization | 10 (8) |

| Researcher | 6 (5) |

| Governmental organization | 3 (2) |

| Other | 3 (2) |

| Setting described in the article | |

| Healthcare setting | |

| Nursing home | 47 (36) |

| Hospital | 29 (22) |

| Legal | 25 (19) |

| General practice | 20 (15) |

| Intensive care unit | 14 (11) |

| Palliative care | 15 (11) |

| Hospice | 9 (7) |

| Other setting | |

| Government | 49 (37) |

| Financial | 9 (7) |

| Other | 3 (2) |

Definition and elements of ACP

In 40 (31%) of the 131 articles, a definition of ACP was provided including one or more of the three key ACP elements: an exploration of values, goals, treatment, and care preferences (26 articles, 65%), discussion of preferences with relatives or healthcare professionals (22 articles, 55%) and recording of treatment and care preferences (22 articles, 55%). In nine articles, all three key ACP elements were mentioned in their definition of ACP; exploration, discussion and recording of preferences. Three examples of how ACP was explained to readers are: (1) article 41: “Start the conversations about advanced care planning, the process of making sure that your wishes for the end of your life, whenever that may be, are known and respected”, (2) article 67: “Advanced Care Planning is about knowing what you would want or wouldn’t want to happen when you or someone you love has to make decisions about your care should you become severely ill. It is an opportunity for families to talk about the important things that matter when it comes to end of life care” and 3) article 86: “We call it advanced care planning, it means having the conversation with people about ‘what you would want to happen if you get sick”.

Most articles provided information on one or more of the three key ACP elements. Specifically, 122 (93%) articles mentioned exploration of treatment and care preferences, 93 (71%) articles mentioned discussion of treatment and care preferences, 94 (72%) articles mentioned recording of treatment and care preferences, and 65 articles (50%) mentioned all three. Of the 131 included articles, 82 (63%) provided information about ACP, such as its nature and why it is important. The remaining 49 (37%) only mentioned the term “advance care planning” and related terms such as “advance care plan”, or “advanced care planning” without explaining the concept. Readiness/timing for ACP was mentioned in 57 articles (44%), by describing the importance of exploring the extent to which people are ready to initiate ACP or by indicating the appropriate timing to initiate ACP. Treatment and care options, mostly CPR (n = 49; 37%), admission to the hospital (n = 45; 34%), artificial ventilation (n = 40; 31%) or admission to the intensive care unit (n = 18; 14%) were mentioned in 105 articles (80%). Less than a third of the articles mentioned the exploration of values/goals (n = 37; 28%) and the appointment of a personal representative (e.g., power of attorney) (n = 35; 27%). Table 2 shows the elements of ACP as discussed in the articles.

Table 2.

Elements of advance care planning (ACP) which were discussed in the newspaper articles (n = 131).

| ACPa elements | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Information about ACP | 82 (63) |

| Readiness/timing for ACP | 57 (44) |

| Exploration of treatment and care preferences | 122 (93) |

| Exploration of values/goals | 37 (28) |

| Treatment and care options | 105 (80) |

| Do-not-resuscitate orders (DNR)/Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) | 49 (37) |

| Admission to hospital/hospital treatment | 45 (34) |

| Artificial ventilation | 40 (31) |

| Admission to the intensive care unit | 18 (14) |

| Treatment and care preferences | 95 (73) |

| Discussion of treatment and care preferences | 93 (71) |

| Discussion with relatives | 73 (56) |

| Discussion with healthcare professionals | 67 (51) |

| Recording of treatment and care preferences | 94 (72) |

| Appointment of a personal representative | 35 (27) |

| Recording of ACP preferences | 90 (69) |

| Sharing the document | 33 (25) |

Advance care planning.

Several terms were used to describe the concept of ACP, for example, “advance care planning” (n = 56) or “advanced care planning” (n = 40). Also, different terms were used to describe the concept of advance directives, such as “advance care plan” (n = 40), “advanced care plan” (n = 32) or “living will” (n = 8). In addition, different terms for personal representatives were used, such as “substitute decision-maker” (n = 9) or “power of attorney” (n = 7). Supplemental File 3 shows an overview of the use of ACP-related terms and their frequency of appearance in the articles.

Reasons to consider engaging in ACP

In 87 of the 131 articles (66%) the reader was encouraged to consider engaging in ACP to discuss preferences with relatives or healthcare professionals (69 articles; 79%), or to make an advance directive (54 articles; 62%). In 39 (45%) articles, a toolkit or a web-based tool was recommended to the reader, for example by providing links. In the remaining 44 (34%) articles the reader was neither encouraged nor discouraged to consider engaging in ACP.

Thirty-one of the 87 articles (36%) mentioned that engagement in ACP is important to avoid a situation where an individual cannot communicate and their preferences are unknown, 24 articles (28%) mentioned engaging in ACP to avoid unwanted medical treatment, and 22 of the 87 articles (25%) mentioned to engage in ACP to avoid family and friends being put in a difficult position if they are required to make decisions in the absence of knowing their dependent’s/relative’s preferences. Twenty-two articles (25%) mentioned the shortage of resources due to COVID-19; for instance, by mentioning that intensive care beds and mechanical ventilation should not be used for people who do not wish to be treated in intensive care settings, and fewer healthcare professionals may be available to conduct ACP discussions with patients about their treatment and care preferences. Table 3 shows the different reasons and examples of those reasons.

Table 3:

Reasons to consider engaging in advance care planning as described in the newspaper articles (n = 87).

| Reason | n (%) | Illustrative example |

|---|---|---|

| To avoid a situation where an individual cannot communicate and their preferences are unknown. | 31 (36) | “Having a health directive is a gift that we can give our loved ones, so they don’t have to guess, and we still participate in our healthcare even when we lose the ability to communicate or if we lose capacity to do those things” (article 124, Canada) (McCall, 2020) |

| To avoid unwanted medical treatment. | 24 (28) | “If you become seriously unwell with COVID-19 and are likely to benefit from active treatment and need a ventilator or are dying, do those closest to you know what type of care you would want?” (article 55, Australia) (Hickman, 2020) |

| To avoid family and friends being put in a difficult position if they are required to make decisions in the absence of knowing their dependent’s/relative’s preferences. | 22 (25) | “With an advance care plan in place, relatives and clinicians have a much clearer idea what the patient would want medically, even if they are too unwell to express it. This translates into a better bereavement process for relatives, should the patient die.” (article 46, UK) (Selman, 2020b) |

| The shortage of resources due to COVID-19 (i.e., shortage of healthcare professionals to discuss preferences, shortage of IC beds). | 22 (25) | “Do I use the last ventilator for the frail 80-year-old grandmother who has a small chance of surviving the coronavirus or the 35-year-old mother who has a much higher chance? These will be devastating decisions for all involved, including my colleagues. Now, imagine that last ventilator is used on a patient who did not really want it or did not want it for long. If her loved ones had taken the time to ask, I would have the information I need to make the best decisions when it matters most.” (article 128, Canada) (Ruenfeld, 2020) |

| The increased risk of severe illness or risk of dying due to COVID-19. | 11 (13) | “With more than 170,000 coronavirus deaths worldwide so far, including 71 in Australia, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of talking to your loved ones about dying and your wishes at the end of your life.” (article 55, Australia) (Hickman, 2020) |

| To reduce pressure/stress among healthcare professionals. | 9 (10) | “There have been an increasing number of stories in the media about the extreme stress the COVID-19 pandemic is placing on front-line workers including physicians, being put in the untenable position of having to make end-of-life decisions for patients – without clear direction from them – only increases the stress.” (article 8, USA) (Compassion & Choices, 2020) |

Three articles presented reasons to engage in ACP as well as disadvantages associated with ACP and reasons not to engage in it, namely: (1) advance care plans are not always shared with healthcare professionals and hence not effective; (2) people living in a care home should not be confronted with ACP any more than other people of their age, their condition should be individually assessed, treatment and care options should be thoroughly discussed so that any future treatment should not be considered to be futile; and (3) the focus should be on discussing what matters to an individual should they become unwell with COVID-19 instead of discussing Do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders; this should be limited to individuals who become severely unwell.

Reasons to consider engaging in ACP per country

Of the articles in which the reader was encouraged to engage in ACP, most were published in the UK (29 of 59 articles, 49%), Canada (26 of 32 articles, 81%), the US (13 of 15 articles, 87%), and Australia (9 of 14 articles, 64%). Articles from the UK, US, and Australia most frequently mentioned considering engaging in ACP to avoid a situation where an individual cannot communicate and their preferences are unknown; UK: 10 articles (34%), US: 7 articles (54%) and Australia: 3 articles (33%). The most frequently mentioned reason in Canadian (11 articles, 42%) and Australian (3 articles, 33%) newspapers was “to avoid family and friends being put in a difficult position if they are required to make decisions in the absence of knowing their relative’s preferences”.

Of the 59 articles from the UK, 28 (47%) referred to concerns that residential and nursing homes for older adults may apply a blanket policy regarding ceilings of the treatment for their residents and apply for DNR orders. A total of 17 articles (article numbers 35, 36, 40, 47, 48, 63, 81, 95, 102, 116, 120–122, 130, 131, 134, 136), cited the former UK Secretary of State for Health and Social Care’s statement that “Advanced care plans including do not attempt to resuscitate orders should not be applied in a blanket fashion to any group of people”. These articles were mostly published in April 2020.

Discussion

Main findings of the study

This content analysis provides insight into the newspaper coverage of ACP during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, insight into the media discourse on ACP, and how ACP is presented to the public. Most articles were published in April 2020 and in newspapers in the UK, Canada, and the US. Most articles were news reports, and most were written by journalists. Although only a third of the articles provided a definition of ACP, most articles described the three key elements of ACP; exploration, discussion, or recording of treatment and care preferences (Rietjens et al., 2017), and half of the articles mentioned all three elements. However, the focus continued to be on treatment and care options, for example, DNR orders/CPR, the use of artificial ventilation, admission to the hospital, and the intensive care unit and less likely (only one-third) to include information on preparation for medical decision making by discussing values and goals, and appointing a personal representative. Most of the articles provided reasons to consider engaging in ACP, for example: to avoid a situation where an individual cannot communicate and their preferences are unknown, or to avoid unwanted medical treatment. The reader was encouraged to engage in ACP in most articles, indicating that ACP was portrayed as useful in the articles during the COVID-19 pandemic.

What this study adds

The COVID-19 pandemic is associated with considerable uncertainty that was amplified by an ‘infodemic’ of misinformation fueled by rumours, stigma, and conspiracy theories (Koffman et al., 2020a; Islam et al., 2020). These public perceptions of ACP may be influenced by media attention during the COVID-19 pandemic (Grant et al., 2021), and research has shown that although the news about COVID-19 may have increased the awareness of the importance of ACP (Dujardin et al., 2021), patients may also experience fear and uncertainty due to news messages (Dujardin et al., 2021; Selman et al., 2020a; Sowden et al., 2021). Although most newspaper articles in our search provided some of the key elements of ACP, the information often did not provide the full picture of ACP. This may result in missed opportunities to engage people in all facets of ACP or to enable them to complete the steps they are most ready to engage in (Zwakman et al., 2021). However, we think it can be questioned whether newspaper articles should be expected to always provide the full ACP concept and all its details. We do think it is important that the articles did not provide false or sensationalist information about ACP and that overall, the articles mentioned important ACP elements. Even the articles about the blanket policy specifically mentioned that advanced care plans including DNR orders should not be applied in a blanket fashion to any group of people, which is in line with the definition of ACP (Rietjens et al., 2017).

To our knowledge, no previous newspaper analyses have been conducted exploring the portrayal of ACP (including exploration of the definition of ACP, elements of ACP, and reasons to engage in ACP), neither before nor during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We recommend education of the public and journalists about the evolving and updated definitions of ACP focused on values and preferences, ongoing discussions of preferences, and designation and preparation of a personal representative (Heyland, 2020; Rietjens et al., 2017; Sudore & Fried, 2010). Researchers, policymakers, and healthcare professionals should promote correct information in (healthcare) information sources about ACP by using appropriate public messaging strategies (Grant et al., 2021; Maunder, 2021). They should be aware that information presented in the media about ACP may be divergent of information about ACP as presented in professional and scientific literature. Healthcare professionals, including palliative care clinicians, should be aware that patients may not fully understand the concept of ACP. To increase public awareness about ACP and to properly inform the public about ACP, public campaigns could be conducted (Seymour, 2018). Public campaigns could refer to publicly accessible (online) ACP programs, since these have been shown to increase knowledge about ACP and engagement in ACP (van der Smissen et al., 2020). Suitable programs are for instance “Making your wishes known” (Green & Levi, 2009), “Prepare for your Care” (Sudore et al., 2014) and “Explore your preferences for treatment and care” (van der Smissen et al., 2022).

Future research could explore the coverage of ACP in social media, an increasingly important source of information used by the public (Smailhodzic et al., 2016), to gain additional insight into the public discourse on ACP. Such research could be conducted by searching for ACP-related terms on social media platforms and by (thematically) analyzing social media posts about ACP, to gain insight into the public awareness of ACP and public discourse about ACP. Furthermore, in future research, the portrayal of ACP-related terms such as “advance directive” and “end-of-life communication” could be studied.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. Our search strategy was formulated in collaboration with the medical library to find relevant articles on ACP and COVID-19. Thorough and systematic content analysis of the articles provided insight into how ACP is portrayed to the public in newspaper articles. Furthermore, we did a cross-country comparison of the articles, providing insight into similarities and differences in the news media portrayal of ACP.

In addition, this study has several limitations. We identified 131 articles on ACP and COVID-19, this number may seem small in comparison to the total number of COVID-19 articles (4 million in 2020). This may have to do with our search strategy focusing on the English term “advance care planning” and not on synonyms or translations of the term. ACP may be less familiar in some countries, and different languages may use different terms to explain ACP.

Conclusion

Engagement in ACP tended to be endorsed in newspaper articles about ACP and COVID-19. Most articles focused on exploring, discussing, or documenting preferences, some mentioned the importance of exploring values/goals in ACP. Articles often did not provide the full picture of ACP; however, they provided important ACP elements, and no false or sensationalist information about ACP. We recommend awareness of healthcare professionals that patients may not fully understand ACP. Public campaigns (referring to (online) ACP programs) could be conducted to inform the public about ACP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elise Krabbendam, Sabrina Gunput, Maarten Engel, Wichor Bramer (biomedical information specialists, Medical Library, Erasmus MC University Medical Center Rotterdam) for their support in literature searching.

Funding

Dr. Sudore is funded in part by the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health [K24AG054415]. The funding source had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Research ethics

The study conforms to the ICMJE recommendations for the conduct, reporting, editing and publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals. No human participants were involved in the study.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2023.2180693

Data availability statement

Raw data were generated at the Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [DvdS] on reasonable request.

References

- Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, & Van der Heide A (2014). The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliative Medicine, 28(8), 1000–1025. 10.1177/0269216314526272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compassion & Choices. (2020). Compassion & choices: federal gov’t urged to reverse new waiver that could result in increased rationing of care. Contify Life Science News, 30 April. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis JR, Kross EK, & Stapleton RD (2020). The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA, 323(18), 1771–1772. 10.1001/jama.2020.4894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutshall NR, Kwan BM, Salmi L, & Lum HD (2020). “It makes people uneasy, but it’s necessary.# BTSM”: Using Twitter to explore advance care planning among brain tumor stakeholders. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 23(1), 121–124. 10.1089/jpm.2019.0077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin J, Schuurmans J, Westerduin D, Wichmann AB, & Engels Y (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic: A tipping point for advance care planning? Experiences of general practitioners. Palliative Medicine, 35(7), 1238–1248. 10.1177/02692163211016979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant MS, Back AL, & Dettmar NS (2021). Public perceptions of advance care planning, palliative care, and hospice: a scoping review. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 24(1), 46–52. 10.1089/jpm.2020.0111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MJ, & Levi BH (2009). Development of an interactive computer program for advance care planning. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy, 12(1), 60–69. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00517.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes M, Ross IE, Gasher M, Gutstein D, Dunn JR, & Hackett RA (2007). Telling stories: news media, health literacy and public policy in Canada. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 64(9), 1842–1852. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyland DK (2020). Advance Care Planning (ACP) vs. Advance Serious Illness Preparations and Planning (ASIPP). Healthcare, 8(3), 218. 10.3390/healthcare8030218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman LD (2020). Does anyone know what your wishes are if you’re sick and dying from coronavirus? The Conversation, April 21.

- Islam MS, Sarkar T, Khan SH, Mostofa Kamal AH, Hasan SMM, Kabir A, Yeasmin D, Islam MA, Amin Chowdhury KI, Anwar KS, Chughtai AA, & Seale H (2020). COVID-19-related infodemic and its impact on public health: a global social media analysis. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 103(4), 1621–1629. 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez G, Tan WS, Virk AK, Low CK, Car J, & Ho AHY (2018). Overview of systematic reviews of advance care planning: summary of evidence and global lessons. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 56(3), 436–459.e25. 10.1016/j.jpainsym-man.2018.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kis-Rigo A, Collins A, Panozzo S, & Philip J (2021). Negative media portrayal of palliative care: a content analysis of print media prior to the passage of Voluntary Assisted Dying legislation in Victoria. Internal Medicine Journal, 51(8), 1336–1339. 10.1111/imj.15458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffman J, Gross J, Etkind SN, & Selman L (2020a). Uncertainty and COVID-19: how are we to respond? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 113(6), 211–216. 10.1177/0141076820930665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffman J, Gross J, Etkind SN, & Selman LE (2020b). Clinical uncertainty and Covid-19: Embrace the questions and find solutions. Palliative Medicine, 34(7), 829–831. 10.1177/0269216320933750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff K (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Maunder L (2021). Motivating people to stay at home: using the Health Belief Model to improve the effectiveness of public health messaging during the COVID-19 pandemic. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 11(10), 1957–1962. 10.1093/tbm/ibab080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall DM (2020). Three things you should do while self-isolating at home. Red Deer Advocate, April 8.

- Mitchinson L, Dowrick A, Buck C, Hoernke K, Martin S, Vanderslott S, Robinson H, Rankl F, Manby L, Lewis-Jackson S, & Vindrola-Padros C (2021). Missing the human connection: A rapid appraisal of healthcare workers’ perceptions and experiences of providing palliative care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliative Medicine, 35(5), 852–861. 10.1177/02692163211004228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson-Becker H, & Victor C (2020). Dying alone and lonely dying: Media discourse and pandemic conditions. Journal of Aging Studies, 55, 100878. 10.1016/j.jaging.2020.100878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimegeer A, Patterson C, & Hilton S (2019). Media framing of childhood obesity: a content analysis of UK newspapers from 1996 to 2014. BMJ Open, 9(4), e025646. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson C, Emslie C, Mason O, Fergie G, & Hilton S (2016). Content analysis of UK newspaper and online news representations of women’s and men’s ‘binge’ drinking: a challenge for communicating evidence-based messages about single-episodic drinking? BMJ Open, 6(12), e013124. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reintjes R, Das E, Klemm C, Richardus JH, Keßler V, & Ahmad A (2016). “Pandemic public health paradox”: Time series analysis of the 2009/10 influenza a/h1n1 epidemiology, media attention, risk perception and public reactions in 5 European countries. PLOS One, 11(3), e0151258. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietjens JAC, Raijmakers NJ, Kouwenhoven PS, Seale C, van Thiel GJ, Trappenburg M, van Delden JJ, & van der Heide A (2013). News media coverage of euthanasia: a content analysis of Dutch national newspapers. BMC Medical Ethics, 14, 11. 10.1186/1472-6939-14-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, van Delden JJ, Drickamer MA, Droger M, van der Heide A, Heyland DK, Houttekier D, Janssen DJA, Orsi L, Payne S, Seymour J, Jox RJ, & Korfage IJ (2017). Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European association for palliative care. The Lancet. Oncology, 18(9), e543–e551. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30582-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruenfeld G (2020). The coronavirus is a chance to have the end-of-life conversation we need. The Globe and Mail, March 17.

- Schwitzer G, Mudur G, Henry D, Wilson A, Goozner M, Simbra M, Sweet M, & Baverstock KA (2005). What are the roles and responsibilities of the media in disseminating health information? PLoS Medicine, 2(7), e215. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selman L, Lapwood S, Jones N, Pocock L, Anderson R, Pilbeam C, Johnston B, Chao D, Roberts N, Short T, & Ondruskova T (2020a). Advance care planning in the community in the context of COVID-19. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford Report, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Selman L (2020b). How coronavirus has transformed the grieving process. The Conversation, April 17.

- Seymour J (2018). The impact of public health awareness campaigns on the awareness and quality of palliative care. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 21(S1) S-30–S-36. 10.1089/jpm.2017.0391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smailhodzic E, Hooijsma W, Boonstra A, & Langley DJ (2016). Social media use in healthcare: A systematic review of effects on patients and on their relationship with healthcare professionals. BMC Health Services Research, 16(1), 442. 10.1186/s12913-016-1691-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowden R, Borgstrom E, & Selman LE (2021). ‘It’s like being in a war with an invisible enemy’: A document analysis of bereavement due to COVID-19 in UK newspapers. PLOS One, 16(3), e0247904. 10.1371/journal.pone.0247904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudore RL, & Fried TR (2010). Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Annals of Internal Medicine, 153(4), 256–261. 10.7326/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudore RL, Knight SJ, McMahan RD, Feuz M, Farrell D, Miao Y, & Barnes DE (2014). A novel website to prepare diverse older adults for decision making and advance care planning: A pilot study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 47(4), 674–686. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Smissen D, Overbeek A, van Dulmen S, van Gemert-Pijnen L, van der Heide A, Rietjens JAC, & Korfage IJ (2020). The feasibility and effectiveness of web-based advance care planning programs: Scoping review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(3), e15578. 10.2196/15578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Smissen D, Rietjens JAC, van Dulmen S, Drenthen T, Vrijaldenhoven-Haitsma F, Wulp M, van der Heide A, & Korfage IJ (2022). The web-based advance care planning program “Explore your preferences for treatment and care”: Development, pilot study, and before-and-after evaluation. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(12), e38561. 10.2196/38561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gorp B, Olthuis G, Vandekeybus A, & van Gurp J (2021). Frames and counter-frames giving meaning to palliative care and euthanasia in the Netherlands. BMC Palliative Care, 20(1), 1–11. 10.1186/s12904-021-00772-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2020). Timeline: WHO’s COVID-19 response: World Health Organisation Retrieved March 03, 2022 from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline

- World Health Organization. (2022). WHO announces COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic: World Health Organization Retrieved March 03, 2022 from: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic.

- Zwakman M, Milota MM, van der Heide A, Jabbarian LJ, Korfage IJ, Rietjens JAC, van Delden JJM, & Kars MC (2021). Unraveling patients’ readiness in advance care planning conversations: a qualitative study as part of the ACTION Study. Supportive Care in Cancer: official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 29(6), 2917–2929. 10.1007/s00520-020-05799-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data were generated at the Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [DvdS] on reasonable request.