Abstract

Internalized or self-stigma can be damaging to psychological and social functioning and recovery, especially for people with serious mental illness. Most studies have focused on the effects of high self-stigma, which has included both moderate and high self-stigma, vs low levels of self-stigma which has included no, minimal, or mild self-stigma. Therefore, little is known about the variation within these categories (e.g. Minimal vs Mild self-stigma) and its impact on recovery. This paper examines differences in the demographic, clinical and psychosocial variables associated with different levels of self-stigma severity. Baseline data (N = 515) from two concurrent randomized controlled trials of a psychosocial intervention aimed at reducing internalized stigma and its effects among adults with serious mental illnesses was examined. We found that participants with greater psychological sense of belonging, and greater perceived recovery were significantly less likely to have Mild or Moderate/High internalized stigma than Minimal stigma. Those reporting a greater frequency of stigma experiences, however, were more likely to have Mild or Moderate/High internalized stigma than Minimal stigma. Our findings further underscore the multifaceted nature and impact of self-stigma, particularly in interpersonal relationships and interactions, and demonstrates the importance of attending to even mild levels of self-stigma endorsement.

Keywords: self-stigma, internalized stigma, serious mental illness, psychological functioning, social functioning

Internalized stigma, also known as self-stigma, is the internalization of stigmatizing messages regarding social identity groups that one belongs to (Dickerson et al., 2002; Herek, et al., 2015; Mossakowski, 2003). People with mental illness face many such stigmatizing stereotypes (Link & Phelan, 2001; Drapalski et al., 2013). Internalizing these beliefs can be difficult to avoid and can harm self-esteem, self-efficacy, coping and motivation, and treatment engagement, putting people at risk for demoralization, depression, and hopelessness (Lucksted & Drapalski, 2015; Rusch, et al., 2005; Yanos, et al., 2008).

Unfortunately, self-stigma among individuals with mental health concerns is not uncommon. Numerous studies have found rates of moderate/high levels of self-stigma among individuals with mental illness to be substantial, with prevalence rates ranging from 21% to 47% across studies (Brohan et al., 2010; Brohan et al., 2011; Dubreucq, et al., 2021; Drapalski et al., 2013). While some suggest that rates may differ somewhat based on mental health diagnosis, they still show that self-stigma is a challenge for many of these individuals, regardless of their specific mental health condition (Brohan et al., 2010; Brohan et al., 2011).

To better understand its impacts, a number of studies have examined demographic, clinical, and psychosocial correlates of self-stigma. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of such studies showed that demographic variables, such as age, gender, education, employment, etc., are not consistently or strongly related to internalized stigma; that clinical variables, such as symptoms, treatment adherence, insight, are moderately correlated with internalized stigma, and that self-stigma may contribute to greater worsening symptoms over time (Boyd, et al.; 2016; Cavelti, et al., 2014), and that psychosocial variables, such as hope, self-esteem, empowerment, quality of life are strongly and consistently related to self-stigma (Dubreucq, et al., 2021; Gerlinger et al., 2013; Livingston & Boyd, 2010). In addition, aspects of social and interpersonal functioning such as sense of belonging (Wastler et al., 2021), perceived social support (Zhang et al., 2019; Cullen et al., 2017), and social network size (Cullen et al., 2017) have been shown to be associated with greater self-stigma. This is not surprising given that one of the key components of self-stigma is sense of alienation from others (Gerlinger et al., 2013). In addition, self-stigma has also been shown to be strongly related to self-reported recovery status Drapalski et al., 2013; Kasli, et al., 2021; Oxele et al., 2017) and, when present, is associated with less recovery over time (Oxele et al., 2017). These studies corroborate that greater self-stigma is associated with more detrimental outcomes, particularly those related to psychosocial functioning and recovery. However, it remains unclear whether there is a minimum amount of self-stigma that is harmful, or if even mild levels may lead to potentially negative outcomes.

A few studies have attempted to investigate this by examining differences among individuals with different levels of self-stigma, using predefined categories. Most often such studies have used the midpoint of a self-stigma measure to categorize individuals as experiencing high vs. low stigma. While practical for data management, such dichotomous categorization limits understanding of how degrees of self-stigma are differentially associated with demographic, clinical, or psychosocial factors and of the clinical implications of reducing self-stigma.

In response, others have proposed and used (Lysaker et al., 2007) a 4-level system to differentiate minimal, mild, moderate, and high self-reported self-stigma. Several studies have used these categories (Harris et al., 2015; Lysaker et al., 2012), but few have examined them in relation to factors or outcomes typically associated with self-stigma. For example, Lysaker and colleagues (2007) examined whether individuals with schizophrenia with low insight/mild stigma, high insight/minimal stigma, or high insight/moderate stigma, differed with regards to hope, self-esteem and social functioning. While there were no differences between groups on interpersonal functioning, the high insight/moderate stigma group demonstrated poorer self-esteem and less hope than either the low insight/mild stigma or the high insight/minimal stigma group after controlling for symptoms. In the two other studies, Brohan and colleagues conducted a mail survey of 1182 individuals with bipolar disorder or depression from 13 countries (Brohan, et al., 2011) and 1,229 individuals with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders from 14 countries (Brohan, et al., 2010) to assess self-stigma and its relationship to perceived discrimination, self-esteem/self-efficacy, power/powerlessness, social contact, and demographic factors. Although they provided the percentages of individuals reporting self-stigma levels in minimal, mild, moderate, and high categories (45.6% minimal, 30.8% low or mild, 18.1% moderate, and 3.6% strong or high; (Brohan et al., 2011) and 23% minimal, 34% low or mild, 29.4% moderate, and 12.3% strong or high (Brohan et al., 2010), respectively), their multivariate analyses compared only two groups -- minimal/mild vs moderate/severe (21.7% and 41.7% in moderate high, respectively). Therefore, we still know little about whether differentiating minimal, mild, moderate and high levels of stigma is clinically meaningful and if so, in what ways. This is particularly important given that, as these studies suggest, a large proportion of individuals with mental health concerns report levels of self-stigma in the mild or minimal range.

Therefore, the goal of this paper was to examine differences in the demographic, clinical and psychosocial variables associated with Lysaker’s four different levels of self-stigma severity (Lysaker et al., 2007): minimal, mild, moderate, and high. Examining these differences will help us better understand if and how lower levels of self-stigma are potentially harmful and whether distinguishing between these levels is clinically useful. This, in turn, could help inform how self-stigma is used as an outcome for both understanding the impact of self-stigma and evaluating the impact of new programs/interventions or programmatic changes that aim to address self-stigma. We generated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: We expect that mild, moderate and high levels of self-stigma will all be associated with clinical variables (e.g., worse psychiatric symptoms) and psychosocial variables (e.g., social/interpersonal functioning; sense of belonging) in univariable analyses.

Hypothesis 2: We expect that in multivariable analysis, more stigma and discrimination experiences, personal recovery, and poorer social/interpersonal functioning will all be unique uniquely associated with mild, moderate, and high self-stigma.

Methods

Participants

Baseline data from two randomized controlled trials of a group intervention aimed at reducing internalized stigma and its effects among adults with serious mental illnesses (SMI; Drapalski et al., 2020, Lucksted et al, 2017), one that compared the intervention to treatment as usual and the other that compared it to a psychoeducational group, were used for the present paper. Participants (N = 515 were recruited from five Maryland community-based psychosocial rehabilitation programs and mental health clinics/programs in three large Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers. Most participants were male (73.3%), Black (51.9%) or White (39.3%), unmarried (89.1%), and not employed (92.6%). Mean age of participants was 48.9 years (SD = 11.7). Most had at least a high school education (80.4%) and approximately half were living in a supervised living facility (45.8%). Psychiatric diagnoses included the following: schizophrenia (28.1%), schizoaffective disorder (23.7%), bipolar disorder (34.2%), major depressive disorder with psychosis (6.5%), major depressive disorder without psychosis (4.5%), and other psychosis (2.2%). A little over half of the participants were Veterans (50.6%).

Procedures

Participants were recruited through clinician referrals, recruitment flyers posted in participating clinics, and verbal invitation at program community meetings between June 2011 and May 2014. At the VA sites, participants were also recruited from review of clinic and program rosters; a partial HIPAA waiver was obtained to allow review of charts to confirm eligibility. Individuals who were eligible were approached in-person at appointments or sent letters regarding the study. Eligible individuals for both studies were between 18 and 80 years of age for VA or 90 years of age for community, willing and able to participate in all aspects of the study, and willing and able to give full informed consent.

At the VA sites, eligibility criteria also included a chart diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or major depression with psychotic features. In the community study, participants were recruited from programs that serve adults meeting Maryland’s “severely mentally ill priority population” definition, which requires a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, recurrent major depressive disorder, schizotypal or borderline personality disorder, or another delusional or psychotic disorder, with documented functional impairments (Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2008). Exclusion criteria for both studies included a documented history of severe or profound intellectual disability.

All participants provided written informed consent. Baseline assessments, lasting approximately 1 ½ hours, typically occurred immediately following consent, immediately after which participants were randomly assigned to their study condition. In addition, all participants were asked to complete a post-intervention and 6-month post-intervention follow-up assessment. Study procedures for the two concurrent RCTs, and later procedures for combining their baseline data, were all approved by the University of Maryland School of Medicine Institutional Review Board, which also oversees VA research at the VA Maryland Health Care System Medical Centers.

Measures

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics.

Demographic information, including age, race/ethnicity, gender, education, living situation, marital status, and employment, was obtained from all participants. Mental health diagnosis was obtained from the participant’s clinical chart.

General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES; Chen, et al., 2001).

The GSES is an 8-item measure used to assess self-efficacy, the degree to which the respondent perceives him or herself as capable of attaining goals, overcoming challenges, and performing well on tasks. For example, items included “I believe I can succeed at most any endeavor to which I set my mind to” and “I am confident that I can perform effectively on many different tasks”. Items are rated on a 5-point response scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Responses are averaged to produce an overall score. The GSES has strong psychometric properties, performing favorably when compared to other measures of the same construct (Chen, et al., 2001; Sherbaum, et al., 2006). Cronbach’s alpha was .89 for this sample, indicating good internal consistency reliability.

Sense of Belonging Instrument (SOBI: Hagerty & Patusky, 1995; Hagerty & Williams, 1999):

The SOBI is a 32-item measure of perceived belongingness. The measure includes two subscales: the psychological subscale (SOBI-P) which measures psychological experiences of belonging (e.g., “It is important to me that I am valued or accepted by others”) and the antecedents subscale (SOBI-A) that measures antecedents that foster belonging (e.g. “I feel like an outsider in most situations”). Items are rated on a 4-point response scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. High scores on the SOBI-P indicate greater belonging; high scores on the SOBI-A indicate greater antecedents that foster belonging. Cronbach’s alpha was .93 for the SOBI-P and .80 for the SOBI-A.

Experiences of Stigma Survey (WSD; Wahl, 1999):

The WSD was used to measure self-reported experiences of stigma and discrimination associated with mental illness. Participants were asked to indicate the degree to which they experienced each of the 20 concerns about or experiences of stigma-related disrespect (9 items; e.g., I have been advised to lower my expectations in life because I am a consumer”) or discrimination (11 items; e.g., “I have been turned down for a job for which I was qualified when it was revealed that I am a consumer”) due to having a mental illness or using mental health services. Items are rated on a 5-point scale, from never to very often. Cronbach’s alpha was .70 for the stigma scale and .77 for the discrimination scale.

The Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Inventory (ISMI; Ritscher et al., 2003):

The ISMI was used to measure internalized or self-stigma. Respondents are asked to indicate the extent to which they agree with 29 statements. using on a 4-point rating scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. These included statements such as “I feel out of place in the world because I have a mental illness” and “People with mental illness cannot live a good, rewarding life”. In addition to producing an overall score, the ISMI contains five subscales: Alienation, Stereotype Endorsement, Discrimination Experience, Social Withdrawal and Stigma Resistance, each assessing different aspects of self-stigma. Because the Stigma Resistance subscale has had low internal consistency reliability in these samples (Drapalski et al., 2020; Lucksted et al., 2017), we removed its five items and used the average rating from the remaining 24 items (ISMI24) as the overall score. Cronbach’s alpha for the total score, excluding the stigma resistance subscale, was .90.

Social Functioning Scale (SFS; Birchwood et al., 1990):

The SFS is an assessment designed to measure social functioning in individuals with SMI. It provides measures of performance of daily living skills, social engagement/ withdrawal, interpersonal communication, recreation, prosocial behavior. For the purposes of this analysis we used the interpersonal communication subscale, which included items such as “How easy or difficult do you find it talking to people at the present time” and “How often are you able to carry on a sensible or logical conversation”.

Maryland Assessment of Recovery in Serious Mental Illness Scale (MARS; Drapalski et al., 2012, 2016):

The MARS is a 25-item self-report measure of recovery in people with serious mental illness. Statements such as “I believe that getting better is possible” and “I can influence important issues in my life”) are are rated on a 5-point scale from not at all to very much. An overall score is calculated by summing item responses. The MARS has demonstrated excellent internal consistency and test-retest-reliability as well as good validity (Drapalski et al., 2016). Cronbach’s alpha was .95 for the current study.

Brief Symptom Inventory

(BSI; Derogatis, 1983; 1993) is a multidimensional symptom inventory derived from the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R), designed to reflect the psychological symptom patterns of respondents in community, medical and psychiatric settings. Responses to this 53-item measure are used to calculate standardized t-scores across nine primary symptom dimensions and three global indices of distress. The instrument has been shown to have strong psychometric integrity. T-scores above 60 on the global severity index (BSI T>60) were used to reflect psychiatric symptom severity. Cronbach’s alpha was .96 in this study, indicating good internal consistency reliability.

Statistical analyses

Candidate demographic, clinical, and domain scales considered to be plausibly associated with internalized stigma, based on theory and past reports, were identified (see Table 1). The ISMI24 average score (range 1–4) was categorized into three ordinal levels: Moderate/High (ISMI24 > 2.5), Mild (ISMI24 between 2.0 and 2.5), and Minimal (ISMI24< 2.0). Because of the low number of participants in the high category, we collapsed the moderate and high categories in one, called Moderate/High. Univariable tests of association between the three-level ISMI24 and the plausible predictors were performed. ANOVA F-tests were used for continuous predictors, and chi-square tests were used for categorical predictors. Mean imputation was used to impute 30 missing item values (0.5% of total sample) of the SOBI-PE scale across 21 of the 515 participants.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics stratified by level of internalized stigma (minimal, mild, moderate/high) and results of univariable tests of association

| Minimal (N=149) | Mild (N=199) | Moderate/High (N=167) | Comparison | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| N | Mean ± SD | % | N | Mean ± SD | % | N | Mean ± SD | % | Test | df | P | |

| /n | /n | /n | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Community Sample (vs. VA Sample) | 149 | 75 | 50 | 199 | 103 | 52 | 167 | 89 | 53 | .28a | 2 | .871 |

| Veteran Age |

149 | 81 | 54 | 199 | 101 | 51 | 167 | 79 | 47 | 1.57a | 2 | .456 |

| <35 | 149 | 18 | 12 | 199 | 35 | 18 | 167 | 21 | 13 | 7.45a | 6 | .283 |

| 35–49 | 34 | 23 | 55 | 28 | 53 | 32 | ||||||

| 50–59 | 69 | 46 | 81 | 41 | 63 | 38 | ||||||

| >=60 | 28 | 19 | 28 | 14 | 30 | 18 | ||||||

| Male Psychotic vs. Mood Disorder (Other Diagnoses Excluded)* |

149 | 117 | 79 | 199 | 144 | 72 | 167 | 116 | 69 | 3.41a | 2 | .181 |

| Psychotic | 148 | 82 | 55 | 189 | 108 | 57 | 164 | 82 | 50 | 1.91a | 2 | .385 |

| Mood Disorder | 66 | 45 | 81 | 43 | 82 | 50 | ||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Less Than 12 Years | 149 | 26 | 17 | 199 | 47 | 24 | 167 | 30 | 18 | 3.00a | 4 | .558 |

| 12 Years | 63 | 42 | 81 | 41 | 75 | 45 | ||||||

| More Than 12 Years | 60 | 40 | 71 | 36 | 62 | 37 | ||||||

| Race | ||||||||||||

| White | 146 | 54 | 37 | 197 | 72 | 37 | 167 | 75 | 45 | 5.68a | 4 | .224 |

| Black | 81 | 55 | 102 | 52 | 81 | 49 | ||||||

| Other | 11 | 8 | 23 | 12 | 11 | 7 | ||||||

| Married or in Relationship | 148 | 59 | 40 | 196 | 85 | 43 | 163 | 67 | 41 | .45a | 2 | .798 |

| Supervised Living Condition | 149 | 66 | 44 | 198 | 87 | 44 | 167 | 83 | 50 | 1.43a | 2 | .489 |

| Years in Treatment | 144 | 24.5 ± 11.3 | 198 | 21.7 ± 13.5 | 164 | 24.3 ± 12.8 | 2.69d | (2,503) | .069 | |||

| BSI Global T Score>60 | 149 | 5 | 3 | 199 | 13 | 7 | 167 | 32 | 19 | 26.17a | 2 | <.001 |

| SOBI-Psychological Experience | <.001 | |||||||||||

| Total** | 149 | 55.3 ± 9.0 | 199 | 47.8 ± 7.1 | 167 | 40.5 ± 9.4 | 120.14d | (2,512) | ||||

| General Self-Efficacy Scale | 149 | 3.9 ± .7 | 199 | 3.6 ± .6 | 167 | 3.4 ± .8 | 26.33d | (2,512) | <.001 | |||

| MARS Total Score | 149 | 108.4 ± 12.9 | 199 | 97.4 ± 14.5 | 167 | 86.2 ± 18.6 | 80.83d | (2,512) | <.001 | |||

| Social Functioning Scale (SFS) | ||||||||||||

| Withdrawal/Social Engagement*** | 148 | 10.5 ± 2.4 | 198 | 9.9 ± 2.2 | 165 | 9.1 ± 2.2 | 13.56d | (2,508) | <.001 | |||

| Interpersonal Communication*** | 148 | 7.9 ± 1.2 | 198 | 7.2 ± 1.6 | 166 | 6.2 ± 1.9 | 46.88d | (2,509) | <.001 | |||

| Recreation | 149 | 20.8 ± 6.0 | 198 | 19.6 ± 6.4 | 166 | 17.7 ±7.4 | 8.58d | (2,510) | <.001 | |||

| Prosocial | 147 | 21.4 ± 10.0 | 198 | 19.2 ± 10.2 | 164 | 16.8 ± 10.6 | 7.60d | (2,506) | <.001 | |||

| Experiences of Stigma Survey (WSD) | ||||||||||||

| Stigma Experiences*** | 149 | 13.0 ± 6.2 | 199 | 15.8 ± 5.1 | 167 | 21.8 ±6.1 | 99.76d | (2,512) | <.001 | |||

| Stigma Discrimination Scale*** | 148 | 10.1 ± 6.2 | 198 | 11.7 ± 7.1 | 167 | 14.3 ±6.9 | 16.68d | (2,510) | <.001 | |||

Chi-Square test

t Test

Wilcoxon test

F test

Fisher exact

Kruskal Wallis

[Mood disorders included bipolar disorder, major depression; Psychotic disorders included schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, major depression with psychosis. and psychosis nos.]

Mean imputation

NA converted to ‘0’

Candidate variables with test-of-association p-values of less than .15 were selected for entry into a multivariable multinomial logistic regression to examine adjusted associations with the three-level internalized stigma variable. For this three-level ordinal variable, the multinomial regression simultaneously fits two logistic models: one for predicting the odds of Moderate/High versus Minimal internalized stigma, and one for predicting the odds of Mild versus Minimal internalized stigma. The General Self-Efficacy Scale was collinear with the Maryland Assessment of Recovery Scale (r = .65), so the General Self-efficacy Scale was not included. All continuous scales were converted to z-scores prior to entry into the model to standardize beta coefficients and odds ratios. Regression analysis with backward step-wise elimination of the candidate variables was then conducted. The stay criterion for the variables was an omnibus Wald-test p-value less than .05. The Nagelkerke pseudo R2 (Nagelkerke, 1991) was used to approximate proportion of variance explained in the final model.

Results

Univariate Relationships between Levels of Self-Stigma and Clinical and Psychosocial Variables

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and results of the univariable tests of association between the candidate predictors and three-level self-stigma; there were no differences by self-stigma level on demographic variables. Hypothesis 1, that mild, moderate and high levels of self-stigma would be associated with clinical and psychosocial variables, was supported. High symptom severity was associated with a higher level of internalized stigma. Higher scores on self-concept variables such as self-efficacy, recovery, and sense of belonging, and social functioning variables such as withdrawal/social engagement, interpersonal communication, recreation, and prosociality were all strongly associated with lower levels of internalized stigma. In contrast, higher scores on self-reported experiences of stigma and stigma discrimination experiences were strongly associated with higher levels of internalized stigma.

Multivariable Analysis of Predictors of Level of Self-Stigma

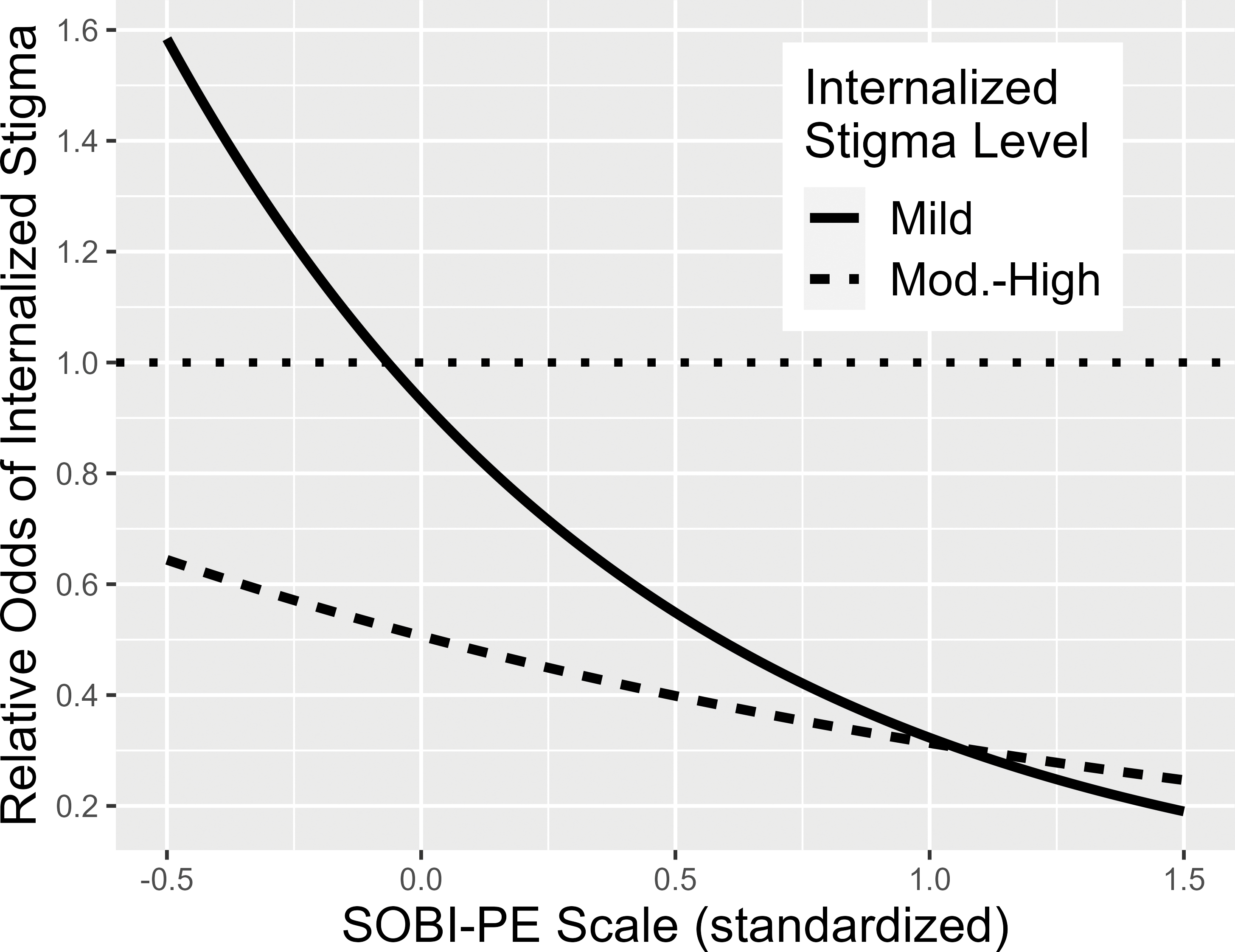

Hypothesis 2 was partially supported. In the backward, stepwise regression analysis years in treatment, the indicator variable for BSI Global T > 60, the discrimination subscale of the Experiences of Stigma Survey, and the Withdrawal/Social Engagement, Recreation, and Prosocial subscales of the SFS were dropped from the model according to the analytic plan. All remaining continuous predictors were checked for linearity on the log odds scale by including square terms for these variables. Results of the final model indicated that participants with greater psychological sense of belonging, and greater perceived recovery were significantly less likely (AORs < 1.0) to have Mild or Moderate/High internalized stigma than Minimal internalized stigma (see Table 2). Those with better self-rated interpersonal communication were significantly less likely to have moderate/high than minimal internalized stigma, but there was no difference between mild and minimal. Those reporting a greater frequency of stigma experiences, however, were more likely (AORs > 1.0) to have Mild or Moderate/High internalized stigma than Minimal stigma.

Table 2.

Final multivariable multinomial regression model for level of internalized stigma (mild, moderate/high versus minimal)1

| Independent Variables2 | Dependent Variable |

Beta (SE) | Wald ϰ2 | p value | AOR3 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| SOBI-PE (Psychological Experience) | Moderate/High | −.92 (.22) | 17.04 | <.0001 | ---4 |

| Mild | −.60 (.18) | 10.60 | .001 | ---4 | |

| SOBI-PE squared5 | Moderate/High | −.24 (.16) | 2.12 | .145 | ---4 |

| Mild | −.53 (.15) | 12.95 | .0003 | ---4 | |

| MARS Total score | Moderate/High | −.79 (.20) | 15.58 | <.0001 | .45 (.31 – .67) |

| Mild | −.53 (.18) | 9.20 | .002 | .59 (.42 – .83) | |

| SFS: Interpersonal communication | Moderate/High | −.63 (.19) | 10.63 | .001 | .54 (.37 – .78) |

| Mild | −.32 (.17) | 3.51 | .061 | .73 (.53 – 1.02) | |

| WSD Stigma Scale | Moderate/High | 1.31 (.20) | 43.13 | <.0001 | 3.69 (2.50 – 5.45) |

| Mild | .37 (.16) | 5.36 | .021 | 1.44 (1.06 – 1.96) | |

Model fit – Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = 0.52

All independent variables standardized to z-scores.

Adjusted odds ratios

Because of a non-linear relationship, the AOR changes depending on SOBI-PE score. See figure 1.

Squared after standardization.

The square term for psychological sense of belonging was significantly associated with internalized stigma (omnibus p = .0013) so it was retained in the model. The quadratic relationship was primarily in the prediction of Mild versus Minimal internalized stigma.

Figure 1 displays model estimated relative odds of Mild and Moderate/High internalized stigma comparing individuals by the standardized sense of belonging score versus individual’s sense of belonging score one standard deviation less. For example, the odds of Mild internalized stigma for an individual whose sense of belonging score is one quarter of a standard deviation below the mean (standardized score = −0.25) relative to an individual one and one quarter standard deviations below the mean is about 20% less, that is, AOR ≈ 1.2). An odds ratio less than 1.0 indicates that the greater sense of belonging score is associated with decreased odds of internalized stigma. For an individual with a standardized score less than ≈ −.08 the odds of Mild internalized stigma is greater versus an individual one standard deviation less, however in all other cases the odds of internalized stigma is reduced with the higher sense-of-belonging score. The negative slope of both curves indicates that the reduction in the odds of internalized stigma is increasing with sense-of-belonging score.

Figure 1.

Adjusted Odds Ratio of Mild and Moderate-to-High Internalized Stigma.

Note: Y axis represents the adjusted relative odds of internalized stigma comparing standardized SOBI-PE score versus the score one standard derviation less.

Discussion

We investigated three levels of internalized stigma, Minimal, Mild, and Moderate/High, and found meaningful differences in the psychological variables associated with each. While previous studies have documented the harmful effects internalized stigma can have (e.g., Brohan, et al., 2011), the common practice of dichotomizing internalized stigma into Low vs. High has left it unclear what, if any, relationship lower levels of internalized stigma might have with demographic, clinical, psychosocial, and recovery related outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first study to extend this previous work by examining a comprehensive list of correlates with three different levels of internalized stigma, thereby allowing for examination of the implications of “mild” levels.

In support of Hypothesis 1, our univariable tests showed that the category of Mild was associated with several clinical, psychosocial, and recovery variables but not with demographic variables compared to Minimal. The absence of demographic associations is in keeping with past related research (Livingston & Boyd, 2010). In partial support of Hypothesis 2, we found that overall recovery, stigma experiences, and sense of belonging were also associated with Mild vs Minimal self-stigma level. These results indicate that even “Mild” levels of internalized stigma merit concern and attention.

Regarding sense of belonging, we found a curious nonlinear relationship comparing the Mild vs Minimal self-stigma levels. If the effect had been linear, as it was with Moderate/High stigma, we would have found that every decrease in sense of belonging would have the same increased likelihood of being in the Mild category vs. Minimal. Instead, individuals with belonging scores two standard deviations above the mean had a smaller, though significant, likelihood of being in the Mild category compared to those with scores one standard deviation below, while those two standard deviations below the mean had a larger likelihood of being the in the Mild category compared to one below. This result provides modest support for a threshold effect. Falling below a certain threshold of sense of belonging may leave people very vulnerable to mild self-stigma; conversely, even modest increases in sense of belonging may protect from mild self-stigma. Because our results are cross-sectional, it is unclear if increasing sense of belonging would have a direct, causal impact on reducing self-stigma. Future studies may want to explicitly test the impact of increasing sense of belonging as a way of preventing mild self-stigma.

Overall, our initial hypotheses were largely supported: a stepwise increase in self-reported exposure to stigmatizing experiences and decreases in sense of belonging, interpersonal communication, and recovery were associated with categories of higher scores on the ISMI, underlining the finding that even “mild” levels of internalized stigma are detrimental.

We also note that the significant predictors in multivariable tests all have strongly interpersonal components. This reflects the social nature of stigmatization and the role of interpersonal relationships/interactions in a person’s risk for and endorsement of self-stigma, which has been well-documented (see Barber, 2019 for review).

Implications and Future Directions

The combination of interpersonal focus and harm at even “mild” levels of internalized stigma has implications for self-stigma interventions. First, the likelihood of multi-directional causality among these associations suggests that many potential points of intervention may be beneficial. For example, interventions designed to benefit one’s sense of belonging directly may also help reduce internalized stigma – perhaps by helping individuals be more resistant to broad feelings of alienation despite encountering societal/interpersonal stigmatization. Related, the social-cognitive model of self-stigma (Watson, et al., 2007; Corrigan, 2004) posits that positive group identification – in this case with others who also have serious mental illness -- can be protective via reducing a person’s agreement with stereotypes about the referent group, making it easier to resist internalizing stigmatizing messages. Results of the current study recommend a closer examination of the role of sense of belonging in the formation of and resistance to self-stigma over time.

Second, our results strongly suggest that people self-reporting “mild” levels of internalized stigma should not be excluded or screened out from self-stigma interventions. Instead, better understanding of whether and how such individuals’ needs differ from those self-reporting much higher self-stigma levels would help calibrate and tailor interventions. For example, they may experience more cognitive dissonance between internalized stigma messages and other aspects of their self-concept compared to people whose personal identity has been largely engulfed by internalized stigma (Conneely, et al. 2021; Wanyee & Arasa, 2020).

Third, the way discrimination experience is measured and the role those experiences play in self-stigma among people with SMI should be carefully considered. We found that experiences of discrimination were associated with levels of self-stigma in univariable tests but not in multivariable regressions. Previous studies have also been mixed, with some finding that discrimination is an important part of the internalization process and others finding no impact (Munoz et al. 2011). We suspect this may be due to differences in how “discrimination” is measured across studies. For example, the discrimination subscale of the WSD focuses on experiences of discrimination due to being a consumer of mental health services in areas such as housing, mental health care, and employment (Wald, 1999). In contrast, the stigma experiences subscale of the ISMI emphasized exposures such as hearing, reading, or seeing media stigmatizing people with mental illness and interpersonal concerns such as being treated as less competent or worrying about others’ reactions to one’s mental health consumer status. These tend to occur more frequently and may be more salient in one’s day to day life, particularly since interpersonal stigma experiences often occur in the context of meaningful relationships such as with family members (Aldersey & Whitley, 2015; Barber et al., 2019) or mental health service providers (Amsalem et al., 2018). Our results thus suggest that future self-stigma interventions should be mindful of the diversity of discrimination experiences and how they might relate to self-stigma. Studies assessing stigma longitudinally and measuring discrimination experiences across multiple contexts (e.g., with family, friends, providers, institutions) are needed to better understand the unique ways that diverse stigma experiences and discrimination contribute to internalized stigma.

Fourth, given our findings that concern about interpersonal communication predicted levels of internalized stigma, it is also important to consider the role of “anticipatory stigma” in individuals’ well-being and in the development and trajectory of internalized stigma over time. For example, it is likely that worries about encountering stigma might contribute to social withdrawal, contribute to social withdrawal, reduced social networks, and decreased sense of belonging and interpersonal confidence – which in turn might reinforce self-stigma beliefs. Future work should explore the development and amelioration of self-stigma over time so that prevention and interventions efforts can better target the process of avoiding internalization in the first place, preventing its worsening, and assisting those who have already internalized deleterious self-assumptions with dislodging them.

Limitations

We acknowledge some limitations of the current effort. First, we were unable to examine differences between moderate and high categories of self-stigma due to a low number of people in our sample endorsing high self-stigma. While additional research on the effects of higher levels of self-stigma and distinctions among them are also needed, the hazards of high self-stigma are better recognized and we expect similar relationships. Further, given the cross-sectional nature of our investigation, we were also limited in our ability to posit causal directions or to determine what might contribute to or drive a person’s progression from Minimal to Mild or from Mild to Moderate/High levels of stigma, or vice versa. In addition, we did not measure illness insight, which has been shown to be associated with poorer outcomes when coupled with higher self-stigma. As such, were unable to examine the relationship between insight and varying levels of self-stigma and potential differences in demographic, clinical and psychosocial variables in those with different levels of insight and self-stigma. Finally, because our sample was majority male, and primarily Black or White, our results may have limited generalizability to other demographic groups.

Conclusions

Taken together, our findings underscore the multifaceted nature and impact of self-stigma and demonstrate the importance of attending to even mild levels of self-stigma endorsement. Our results suggest that a majority of individuals experience at least some internalized stigma, and that there are meaningful differences in the impact of stigma on recovery the more it is internalized. While having moderate or high internalized stigma is clearly problematic, even mild internalized stigma was found to be detrimental with regards to interpersonal relationships / interactions, perceived connectedness to others, and personal recovery. This suggests the need for and potential benefit of mental health providers engaging all individuals with whom they work in conversations about internalized stigma and how it may have impacted their recovery. Moreover, it suggests that, when needed, providers should address internalized stigma as part of treatment and not accept “Mild” levels as clinically benign.

The observed roles of interpersonal communications, recovery orientation, and sense of belonging in predicting Mild and Moderate/High levels of self-stigma suggest multiple routes to reducing self-stigma and the potential benefits of addressing them simultaneously. This can involve using interventions or tools that target self-stigmatizing thoughts or beliefs directly, those that aim to promote a sense of belonging and connection with others so as to reduce the alienation often associated with self-stigma, recovery-oriented interventions focus on helping individuals engage meaningful and purposeful life roles and activities, thereby, promoting a positive self-concept, behavioral strategies to avoid or even interrupt stigma in one’s social environments, or many others. Given the role of interpersonal relationships/interactions in a person’s risk for and endorsement of self-stigma, focusing on helping individuals strengthen their sense of belonging, connection, and positive interpersonal interactions with others may be particularly important in reducing the effects of self-stigma. In sum our findings underline the need for providers, programs, and service users to assess and attend to (even mild levels of) internalized stigma as an obstacle and threat to recovery and well-being.

Impact statement:

It has been well-established that internalized stigma or self-stigma can be damaging to psychological and social functioning and recovery, especially for people with serious mental illness. Most studies have focused on the effects of high vs low levels of self-stigma. In this study, we examine predictors of mild self-stigma as an intermediate category. We discuss findings with recommendations to guide future work to address self-stigma.

Author’s Note:

This work was supported by NIMH 1R01MH090036-01A1 and Merit Review 1I01HX00279 from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Services and the VA Capitol Network (VISN5) Mental Illness, Research, Education, and Clinical Center. Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01259427. The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. Dr. Natasha Tonge is now at the Department of Psychology at Notre Dame of Maryland University.

References

- Aldersey HM, & Whitley R (2015). Family influence in recovery from severe mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 51(4), 467–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber S, Gronholm PC, Ahuja S, Rüsch N, & Thornicroft G (2020). Microaggressions towards people affected by mental health problems: a scoping review. Epidemiology and psychiatric sciences, 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchwood M, Smith J, Cochrane R, Wetton S, & Copestake S (1990). The Social Functioning Scale. The development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 157(6), 853–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J, Hayward H, Bassett ED, & Hoff R (2016). Internalized stigma of mental illness and depressive and psychotic symptoms in homeless veterans over 6 months. Psychiatry Research, 240, 253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohan E, Elgie R, Sartorius N, et al. (2010). Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with schizophrenia in 14 European countries: The GAMIAN-Europe study. Schizophrenia Research, 122, 232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohan E, Gauci D, Sartorius N, et al. (2011). Self-stigma, empowerment and perceive discrimination among people with bipolar or depression in 13 European countries: The GAMIAN-Europe study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 129, 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavelti M, Rusch N & Vauth R (2014) Is living with psychosis demoralizing? Insight, self-stigma, and clinical outcome among people with schizophrenia across 1 year. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 202(7), 521–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Gully SM, & Eden D (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4(1), 62–83. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe A, Averett P, & Glass JS (2016). Mental illness stigma, psychological resilience, and help seeking: What are the relationships? Mental Health and Prevention, 4(2), 63–68. 10.1016/j.mhp.2015.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conneely M, McNamee P, Gupta V, Richardson J, Priebe S, Jones JM, & Giacco D (2021). Understanding identity changes in psychosis: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 47(2), 309–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen BAM, Mojtobai R, Bordbar E, Everette M, Nugent KL & Eaton WW (2017). Social network, recovery attitudes, and internalized stigma among those with serious mental illness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 63(5), 448–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR (1993). BSI Brief Symptom Inventory, Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual (4th Ed.). National Computer Systems, Minneapolis, MN. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR Melisaratos N. (1983). The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13, 595–605 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson FB, Sommerville J, Origoni AE, Ringel NB, & Parente F (2002). Experiences of stigma among outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 28(1), 143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapalski AL, Medoff D, Unick GJ, Velligan D, Dixon L, Bellack AS (2012). Assessing recovery in people with serious mental illness: Development of a new scale. Psychiatric Services, 63(1), 48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapalski AL, Lucksted A, Perrin PB, Aakre JM, Brown CH, DeForge BR, & Boyd JE (2013). A model of internalized stigma and its effects on people with mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 64(3), 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapalski AL, Medoff D, Dixon L, Bellack AS (2016). The reliability and validity of the Maryland Assessment of Recovery Scale. Psychiatry Research, 239, 259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreucq J, Plasse J, & Franck N (2021). Self-stigma in serious mental illness: a systematic review of frequency, correlates, and consequences. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 47(5), 1261–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlinger G, Hauser M, De Hert M, Lacluyse K, Wampers M, Correll CU, (2013). Personal stigma in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: as systematic review of prevalence rates, correlated, impact, and interventions. World Psychiatry, 12, 155–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerty BM, & Williams A (1999). The effects of sense of belonging, social support, conflict, and loneliness on depression. Nursing research, 48(4), 215–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerty BMK., & Patusky K. (1995). Developing a measure of sense of belonging. Nursing Research, 44, 9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JI, Farchin L, Stull L, et al. (2015). Prediction of changes in self-stigma among Veterans participating in partial psychiatric hospitalization: the role of disability status and military cohort. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 38(2), 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Gillis JR, & Cogan JC (2015). Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Stigma and Health, 1(S), 18–34. 10.1037/2376-6972.1.S.18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasli S, Al O, & Bademli K (2021). Internalized stigmatization and subjective recovery in individuals with chronic mental illness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 67(5), 415–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, & Phelan JC (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JD & Boyd J (2010). Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 71, 2150–2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucksted A, Drapalski AL, (2015). Self-stigma regarding mental illness: Definition, impact, and relationship to societal stigma. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 38(2), 99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Roe D, & Yanos PT (2007). Toward understanding the insight paradox: internalized stigma moderates the association between insight and social functioning, hope, and self-esteem among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 33(1), 192–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysaker PH, Roe D, Ringer J, et al. (2012). Change in self-stigma among persons with schizophrenia enrolled in rehabilitation: associations with self-esteem and positive and emotional discomfort symptoms. Psychological Services, 9(3), 240–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski KN (2003). Coping with perceived discrimination: Does ethnic identity protect mental health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44(3), 318. 10.2307/1519782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagelkerke N (1991). A note on a general definition of the coefficient of determination. Biometrika, 78: 691–692. [Google Scholar]

- Oxele N, Mullerz M, Kawohl W, Xu Z, Viering S, Wyss C, Vetter S, Rusch N (2017). Self-stigma as a barrier to recovery: a longitudinal study. European Archives of Psychiatry & Clinical Neuroscience, 268, 209–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, & Grajales M (2003). Internalized stigma of mental illness: Psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Research, 12, 31–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB & Phelan J (2004). Internalized stigma predicts erosion of morale among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Research, 29, 257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Angermeyer MC, & Corrigan PW (2005). Mental illness stigma: Concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. European Psychiatry, 20(8), 529–539. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent J, Williams RA, Hagerty B, Lynch-Sauer J, & Hoyle K (2002). Sense of belonging as a buffer against depressive symptoms. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 8(4), 120–129. [Google Scholar]

- Scherbaum CA, Cohen-Charash Y, & Kern MJ (2006). Measuring general self-efficacy: A comparison of three measures using item response theory. Educational and psychological measurement, 66(6), 1047–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl OF (1999). Mental health consumers’ experience of stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 25(3), 467–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanyee VW, & Arasa D (2020). Literature review of the relationship between illness identity and recovery outcomes among adults with severe mental illness. Modern Psychological Studies, 25(2), 10. [Google Scholar]

- Yanos PT, Roe D, Markus K, & Lysaker PH (2008). Pathways between internalized stigma and outcomes related to recovery in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services, 59(12), 1437–1442. 10.1176/appi.ps.59.12.1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Wong IY, Yu Y et al. (2019). An integrated model of internalized stigma and recovery-related outcomes among people diagnosed with schizophrenia in rural China. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54, 911–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]