Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a liver cancer, highly heterogeneous both at the histopathological and molecular levels. It arises from hepatocytes as the result of the accumulation of numerous genomic alterations in various signaling pathways, including canonical WNT/β-catenin, AKT/mTOR, MAPK pathways as well as signaling associated with telomere maintenance, p53/cell cycle regulation, epigenetic modifiers, and oxidative stress. The role of WNT/β-catenin signaling in liver homeostasis and regeneration is well established, whereas in development and progression of HCC is extensively studied. Herein, we review recent advances in our understanding of how WNT/β-catenin signaling facilitates the HCC development, acquisition of stemness features, metastasis, and resistance to treatment. We outline genetic and epigenetic alterations that lead to activated WNT/β-catenin signaling in HCC. We discuss the pivotal roles of CTNNB1 mutations, aberrantly expressed non-coding RNAs and complexity of crosstalk between WNT/β-catenin signaling and other signaling pathways as challenging or advantageous aspects of therapy development and molecular stratification of HCC patients for treatment.

Keywords: Cancer stem cells, CTNNB1 mutations, Liver cancer, Non-coding RNA, Tumor heterogeneity

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of liver cancer accounting for approximately 80% of primary liver tumors.1 Hepatocarcinogenesis is a multistep process that starts from precancerous lesions (dysplastic nodules) that develop in cirrhosis or from hepatocellular adenomas that arise in the normal liver.2 Although hepatocarcinogenesis is a multifactorial process, most HCC cases are associated with chronic hepatitis B (HBV) or C (HCV) infections.3 Other risk factors include hepatitis D (HDV) coinfection, metabolic factors (obesity, insulin resistance, type II diabetes, or dyslipidemia in nonalcoholic HCC), or toxin/environmental factors (e.g., alcohol or smoking).4 Early-stage HCC can be treated by local ablation, surgical resection, or liver transplantation, however, due to the asymptomatic nature of HCC at an early stage of disease, the majority of patients are diagnosed at advanced stages.5 While systemic treatment options (sorafenib, lenvatinib, cabozantinib, regorafenib, ramucirumab, bevacizumab plus atezolizumab, etc.) for patients with advanced HCC provide limited survival benefits, they rapidly evolve.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 The accumulation of various genetic and epigenetic modifications leads to signaling dysregulation that triggers the transformation of normal hepatocytes toward malignant phenotypes and disease progression.14 The gradual loss of differentiation phenotype and acquisition of stemness features may explain the extensive heterogeneity of the HCC tumor.15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Molecular subtyping of HCC substantially advanced the knowledge of mechanisms that contribute to the progression of the disease.20 Several signaling pathways, e.g., WNT/β-catenin, RAS/RAF/MAPK, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), as well as the signaling associated with telomere maintenance, p53/cell cycle regulation, epigenetic modifiers, oxidative stress, and ubiquitin/proteasome degradation are involved in HCC initiation and/or progression, either in response to viral infection or exposure to toxic agents.20

Among signaling pathways implicated in the pathogenesis of HCC, WNT/β-catenin signaling is one of the most frequently activated.21,22 Aberrant WNT signaling contributes to the development of various cancer types.23, 24, 25, 26 This review is focused on WNT signaling in HCC and highlights the assumption that understanding the aberrant activation of this signaling in HCC is important for the development of novel treatment strategies and better stratification of HCC patients for targeted therapies and immunotherapies.

WNT signaling pathways

The WNT signaling pathway plays a key role in embryonic development, adult tissue homeostasis, and regeneration. WNT signaling can be divided into canonical β-catenin-dependent pathway and non-canonical β-catenin-independent pathway (the latter can be further divided into WNT/planar cell polarity (PCP) and calcium pathways).27 Despite this distinction, canonical and non-canonical pathways form a network with concomitant crosstalk and mutual regulation.28 The family of WNT ligands includes 19 secreted cysteine-rich glycoproteins, and the mode of WNT signaling is largely determined by the type of ligand.20,29,30

Canonical WNT signaling pathway

β-catenin is the main component of canonical WNT signaling.30 In the absence of WNT ligands, β-catenin is involved in cell adhesion, acting as a bridge between E-cadherin and cytoskeleton-associated actin to form adherent junctions between the adjacent cells.19, 31 β-catenin that is kept in adhesion complexes forms a pool of protein capable of nuclear signaling in response to several stimuli.

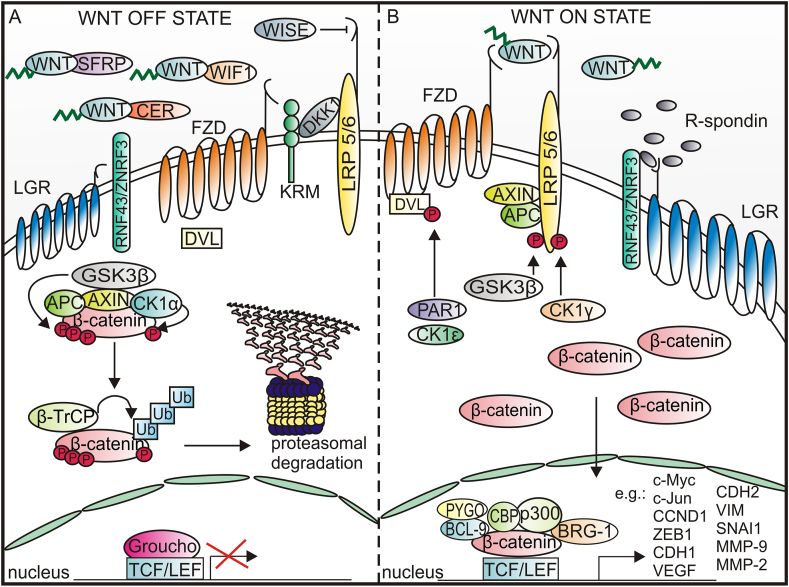

Canonical WNT signaling is usually inactive in adult tissues, even if the WNT ligands are produced constitutively. This is because the activity of canonical WNT signaling is modulated by several agonists and antagonists of ligands and receptors e.g., WNT inhibitory factor 1 (WIF1), Dickkopf-1 (DKK1), secreted frizzled-related proteins (SFRPs), WNT modulator in surface ectoderm (WISE), Cerberus protein (CER), and Kremen (KRM).29,32 DKK1 by interacting with low-density-lipoprotein-related protein 5/6 (LRP5/6) receptors and co-receptor Kremen triggers LRP5/6 endocytosis, thereby preventing formation of the LRP-5/6-WNT-FZD complex, whereas CER, SFRPs and WIF1 prevent WNTs from binding to their receptors.33 DKK1 is considered an early-stage HCC biomarker with a sensitivity for the detection in the range of 70%–72%,34 and diagnostic and prognostic utility of serum levels of DKK1 have been shown recently.35 The activity of WNTs can be also modulated by a feedback antagonist NOTUM that enzymatically inhibits WNT signaling by removing the palmitoleate moiety from WNTs.20 In WNT OFF state, the level of cytoplasmic β-catenin is low, because of β-catenin interaction with the “destruction complex” formed by adenomatosis polyposis coli (APC), axis inhibition protein (AXIN), glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), and casein kinase 1α (CK1α). AXIN is a scaffold protein that directly interacts with all other components of the destruction complex.36 In the destruction complex, β-catenin is phosphorylated on Ser 45 by CK1α and subsequently on Ser 33, Ser 37, and Thr41 by GSK3β. The phosphorylated motif is then recognized by F-box containing protein E3 ubiquitin ligase, β-transducin repeat-containing protein (β-TrCP) that mediates ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of β-catenin20 (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of canonical WNT signaling. (A) In WNT OFF state, WNTs are bound by antagonists, and β-catenin is either immobilized by E-cadherin in adherent junctions or phosphorylated in cytoplasm by the destruction complex consisting of AXIN, APC, GSK3β, and CK1α. CK1α phosphorylates β-catenin on Ser 45 residue that initiates phosphorylation of Thr41, Ser 37, and Ser 33 residues by GSK3β. The phosphorylation of β-catenin leads to its ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation. (B) In WNT ON state, WNT ligands interact with FZD receptors and LRP co-receptors. AXIN associates with LRP5/6, whereas DVL is recruited to FZD. After inhibition of GSK3β, stable unphosphorylated β-catenin translocates to the nucleus to activate the expression of target genes.

β-catenin-dependent signaling is initiated by the binding of WNT ligand to the seven-pass transmembrane frizzled (FZD) receptor and LRP5/6 receptor (Fig. 1B). Conformational changes of FZD and LRP5/6 receptors are followed by phosphorylation of LRP5/6, triggered by GSK3β and casein kinase 1 γ (CK1γ). Disheveled (DVL) is recruited to the plasma membrane, interacts with the C-terminal tail of FZD, and is concomitantly phosphorylated by protein kinases e.g., protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR1) and casein kinase 1ε (CK1ε). Activated DVL separates AXIN from the destruction complex and released AXIN binds to the phosphorylated LRP5/6 receptor. The sequestration of AXIN prevents phosphorylation of β-catenin and its proteasomal degradation. Canonical WNT signaling can be potentiated by the leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled receptor 5/a roof plate-specific spondin (LGR5/RSPO) complex.37 The LRG5/RSPO complex promotes WNT/β-catenin signaling through the neutralization of ring finger protein 43 (RNF43) and zinc and ring finger protein 3 (ZNRF3) that mediate endocytosis and lysosomal degradation of FZD receptors.38 As a result, stable, unphosphorylated β-catenin is accumulated in the cytoplasm and translocated to the nucleus, where after displacing the transcriptional repressor Groucho, β-catenin interacts with T cell factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (TCF/LEF), and other proteins e.g., brahma-related gene-1 (BRG-1), TATA-binding protein, CREB-binding protein/its homolog p300 (CBP/p300), and B-cell CLL/lymphoma 9 protein (BCL-9) that links the N terminal part of β-catenin with pygopus (PYGO).19

The transcriptional role of β-catenin extends beyond the TCF/LEF as β-catenin may be a partner of other transcription factors, e.g., hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF1 ), forkhead box class O family member proteins (FOXOs), sex-determining region Y (SRY)-related HMG box (SOX), mothers against decapentaplegic homolog (SMAD), and octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (OCT4).19,39 β-catenin serves as a transcriptional regulator of the expression of genes that encode regulators of the canonical WNT pathway and proteins involved in proliferation, dedifferentiation, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), migration, invasiveness, and metabolism. In the liver, β-catenin-dependent WNT-signaling is incorporated in hepatobiliary development, cell differentiation, homeostasis, and repair, therefore the abnormalities in this signaling result in liver diseases, including malignancies.22

Non-canonical WNT signaling

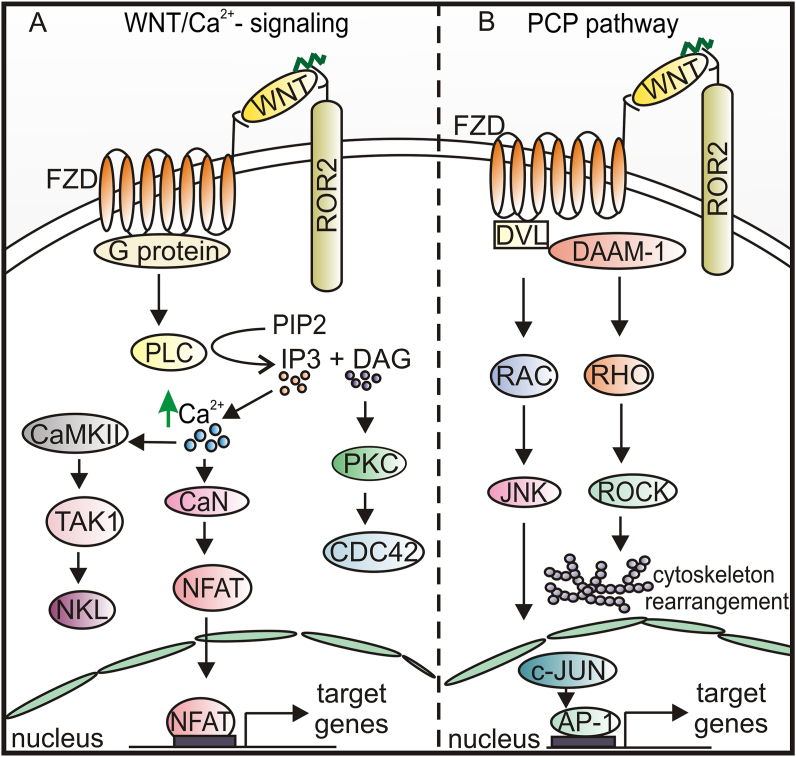

WNT5a plays a crucial role in activating non-canonical WNT pathways (Fig. 2A, B), however, this ligand can also modulate the activity of the canonical WNT pathway and other signaling cascades leading to the activation of numerous protein kinases and transcription factors.30,40 The aberrant WNT5a signaling can generate a dual effect on the tumor microenvironment, first by activating an autocrine RAR-related orphan receptor (ROR1)/AKT/p65 pathway that promotes both inflammation and chemotaxis of immune cells, and then by activating a toll-like receptor (TLR)/MyD88/p50 pathway only in myelomonocytic cells, thus promoting a tolerogenic phenotype.40 In this way WNT5a may contribute to the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and resistance to immunotherapy. Noncanonical WNT5a, WNT9b, WNT10a, and WNT10b can antagonize WNT3a-induced β-catenin/TCF activity and modulate stemness, proliferation, and terminal differentiation of hepatic progenitors.30

Figure 2.

A schematic representation of non-canonical WNT-signaling pathways. (A) WNT/Ca2+ signaling pathway is initiated by WNT binding to FZD and ROR, with further activation of G-protein, that triggers PLC activation leading to PIP2 hydrolysis to DAG and IP3. DAG activates PKC, which in turn activates the small GTPase CDC42 that plays a crucial role in regulating actin cytoskeleton organization and dynamics. IP3 causes the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores leading to CaMKII and CaN activation. CaMKII phosphorylates TAK1, which activates NLK, thus inhibiting canonical WNT signaling. CaN activates NFAT, which then translocates to the nucleus and regulates the expression of target genes. (B) WNT/PCP is initiated by WNT binding to FZD and ROR receptors to convey the signal to DVL. Activation of DVL-DAAM-1 complex is followed by JNK and ROCK activation and cytoskeletal rearrangement. AP-1, activator protein 1; CaMKII, Ca2+/calmodulin dependent kinase II; CaN, calcineurin; CDC42, cell division cycle 42; DAG, diacylglycerol; DAAM-1, DVL associated activator of morphogenesis; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinases; NLK, nemo like kinase; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T-cells; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate; PKC, protein kinase C; PLC, phospholipase C; RAC, Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate; RHO, Ras homolog gene family; ROCK, Rho-associated kinase; TAK1, transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1.

The level of WNT5a is reduced in HCCs compared to adjacent non-tumorous tissues.41 Reduced expression of WNT5a and ROR2 in HCC tissues correlates well with tumor stage.42 Moreover, overexpression of WNT5a inhibits the proliferation, motility, and colony-forming potential of HCC cells suggesting that WNT5a acts as a tumor-suppressing ligand in HCC.43 Trafficking of FZD2 and ROR1 to the plasma membrane followed by activation of the WNT/PCP pathway has been associated with elevated expression of vesicle protein sorting 35 (VPS35), pointing to VPS35 as a potential prognostic biomarker in HCC.44

WNT/β-catenin signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma, from genetic landscape to microenvironmental impact

Multiple mechanisms leading to activation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway can be triggered during HCC initiation and progression. These mechanisms include somatic mutations and epigenetic alterations, among which promoter methylation and aberrant expression of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are the most studied in HCC.

Genetic alterations in genes encoding components of the WNT/β-catenin pathway

WNT/β-catenin signaling is essential for liver function, from hepatobiliary development to repair processes. While the β-catenin level is low in normal hepatocytes of healthy liver and β-catenin is mainly membrane-localized, its level is increased in the cytoplasm and nucleus during HCC development indicating that canonical WNT signaling is re-activated.21,45, 46, 47 CTNNB1, encoding β-catenin, is one of the most prevalently mutated genes in HCC.45,48 The frequency of mutations in CTNNB1 varies depending on the region and race, and it is higher in HCC patients in Asia and Europe than in Africa.45,49 Moreover, it varies depending on HCC etiology, and a much higher frequency of CTNNB1 mutations is found in HCV-related HCCs (28%) and non-viral HCCs (26%) than in HBV-related HCCs (11%). The highest frequency of CTNNB1 mutations is associated with alcohol-related HCCs (42%).50,51 Most of the mutations, mainly gain-of-function, arise in exon 3 of CTNNB1 at the serine/threonine sites preventing β-catenin from phosphorylation and degradation. Ser 45 phosphorylated by CK1α and Ser 33 phosphorylated by GSK3β are the most commonly altered residues of β-catenin in HCCs.48,52 These gain-of-function mutations of CTNNB1 contribute to β-catenin stabilization and its translocation from cytoplasm to nucleus. Large in-frame exon 3 deletions and point mutations occurring at codons for Asp32-Ser 37 produce a strong β-catenin signal, mutations located at the codon for Thr 41 give moderate β-catenin activity, whereas mutations located in codons for Ser 45, Lys 335, and Asn 387 result in a weak β-catenin activity. HCC patients with Ser 45 mutation have a better prognosis than those with mutations introducing changes in codons 32–37 or 41.53 Alterations leading to amino acid substitutions and reduced binding to APC have been detected in armadillo repeat domains 5/6.54 Other mutations occur in AXIN1 and APC, encoding important components of degradation complex.55,56 Mutations in AXIN1 and APC, mainly missense mutations or deletions, result in loss of suppressive activity of AXIN1 and APC.57 AXIN1 and APC mutations are rare, 8% and 3% respectively. It is thought that in the liver, which is a low-proliferative organ in comparison to the small intestine and colon, a single mutation in CTNNB1 is more likely to occur than biallelic mutations in APC or AXIN1.58 Based on genomic approaches, HCCs belong either to a proliferating class with loss-of-function mutations in AXIN1 and chromosomal instability or to a nonproliferating/inflammatory class with gain-of-function mutations in CTNNB1 and chromosomal stability.59 It has been also suggested that mutated genes encoding CTNNB1 and AXIN1, representing themselves a negative epistatic interaction, participate in positive epistatic interactions with mutations in different genes: CTNNB1 mutations with mutations in TERT promoter, ARID2, and NFE2L2, whereas AXIN1 mutations with mutations in ARID1A and RPS6KA3.51 Rearrangement of gene encoding RSPO2 is considered as another mechanism that functionally substitutes for the CTNNB1 mutation-driven activation of WNT signaling during development of HCC.60 Tissue microarray has shown the enhanced expression of RSPO2 in HCC clinical samples compared with adjacent normal tissue, and overexpression of RSPO2 has been associated with increased expression of β-catenin indicating that RSPO2 might contribute to HCC promotion via the WNT/β-catenin pathway.61

Epigenetic alterations via promoter methylation affecting WNT/β-catenin signaling in HCC

Alterations in epigenetic regulation contribute to WNT signaling activation and hepatocarcinogenesis.62 It has been found that HCV core protein induces epigenetic silencing of SFRP1 by hypermethylation of its promoter leading to the re-activation of WNT signaling, thus contributing to the development of HCC aggressiveness through induction of EMT.63 APC is inactivated by hypermethylation in more than 80% of HCC samples.62 WIF1 promoter hypermethylation is suggested as a primary cause of loss of WIF1 function in HCC, and the restoration of WIF1 expression in tumor cells decreased canonical WNT signaling leading to inhibition of HCC cell proliferation.64 Reduced expression of WIF1 has been observed in HCC tissue compared to adjacent non-cancerous tissues.65 The epigenetic inactivation of DKK2,66 DKK3,65 WIF1,64,65 and SFRPs67 results in enhanced WNT/β-catenin signaling. DKK3 mRNA level has been found significantly lower in Edmonson stage III than that in stage I/II suggesting that reduced expression of DKK3 is associated with invasive properties of HCC cells.65

Non-coding RNAs affecting WNT/β-catenin signaling in HCC

Aberrant expression of ncRNAs, such as long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), and microRNAs (miRNAs) contributes to liver carcinogenesis and progression, and changes in ncRNA levels have been associated with alterations of the WNT/β-catenin pathway activity in HCC as reviewed recently.68,69

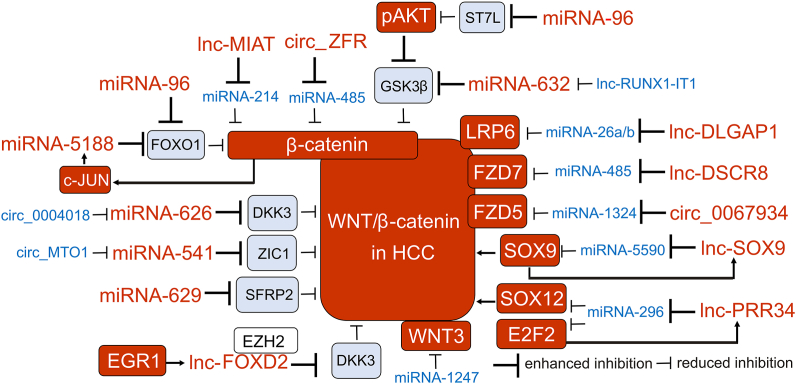

lncRNAs can affect DNA methylation, histone modification, chromatin remodeling, mRNA, and proteins by regulating their stability and activity. Several lncRNAs contribute to HCC progression. Over-activated lncRNA-CRNDE through regulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway and WNT/β-catenin pathway promotes proliferation of HCC cells70; lncRNA-ASB16-AS1 by regulating the miR-1827/FZD/WNT/β-catenin axis promotes growth and invasion of HCC cells71; lncRNA-FOXD2-AS1 up-regulation induced by epidermal growth factor receptor 1 (EGR1) via epigenetically silencing DKK1 and activation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway promotes the progression of HCC cells72; lncRNA-RAB5IF via LGR5-mediated enhancement of cellular myelocytomatosis (c-MYC) and β-catenin promotes the proliferation of HCC cells73; lncRNA-DAW by mediating enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) degradation de-represses WNT2 transcription and re-activates WNT/β-catenin signaling in HCC cells74; lncRNA-LINC00662 by reducing expression levels of miRNA-15a, miRNA-16, and miRNA-107 enhances secretion of WNT3a, which activates β-catenin in HCC cells and in a paracrine manner in macrophages mediating their M2 polarization75; lncRNA-HOMER3-AS1 via up-regulating HOMER3 and WNT/β-catenin signaling stimulates HCC progression by modulating the behavior of both HCC cells and macrophages.76 LncRNA-CR594175, increasingly expressed during the development of HCC, by sponging miR-142-3p interferes with its negative regulation of CTNNB1.77 Several over-activated lncRNAs contribute to EMT, invasion, and metastasis of HCC cells via WNT/β-catenin signaling.78 lncRNA-MUF interacts with Annexin A2 and promotes WNT/β-catenin signaling and EMT, and its overexpression has been correlated with poor clinical outcome for HCC patients79; lncRNA-DLGAP1-AS1 serves as a sponge sequestering the HCC-inhibitory miRNA-26a/b-5p to positively regulate CDK8 and LRP680; lncRNA-SNHG5 by regulating miRNA26a/GSK3β axis promotes HCC progression and metastasis81; lncRNA-SNHG7 by sponging miRNA-425 and upregulation of WNT/β-catenin signaling enhances proliferation, migration, and invasiveness of HCC cells82; lncRNA-SOX9-AS1 contributes to HCC metastasis through a SOX9-AS1/miR-5590-3p/SOX9 positive feedback loop and up-regulation of WNT/β-catenin pathway83; lncRNA-PRR34-AS1 promotes HCC development by sequestering miRNA-296-5p and positively regulating E2F2/SOX12/WNT/β-catenin axis84; lncRNA-DSCR8 acts as a sponge for miRNA-485-5p to up-regulate FZD7 expression and WNT/β-catenin pathway activity to promote HCC progression85; lncRNA-MIAT by sponging miRNA-214 up-regulates β-catenin86; and lncRNA-HANR inhibits apoptosis and induces chemoresistance in HCC by binding to GSK3β interacting protein (GSKIP) and regulating GSK3β phosphorylation.87 RUNX1-IT1, TP53TG1, NEF, ANCR, and CASC2c are examples of lncRNAs potentially acting as HCC-suppressors by preventing WNT/β-catenin signaling activation, however, their expression is substantially reduced in HCCs. As hypoxia-driven HDAC3 down-regulates lncRNA-RUNX1-IT1 in HCC, this lncRNA is not capable to act as a sponge for miRNA-632, which could otherwise directly targets GSK3β and hyperactivates WNT/β-catenin signaling.88 lncRNA-TP53TG1 exerts its tumor-suppressive effects by interacting with peroxiredoxin 4 (PRDX4) and promoting its ubiquitin-mediated degradation, which leads to the inactivation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway, but lncRNA-TP53TG1 is down-regulated in HCCs.89 lncRNA-NEF, transcriptionally activated by EMT suppressor forkhead box A2 (FOXA2) by supporting the binding of β-catenin with GSK3β can suppress WNT/β-catenin signaling, however, lncRNA-NEF is down-regulated in HCCs.90 lncRNA-ANCR that enhances the GSK3β expression and decreases WNT1 expression and lncRNA-CASC2c that inhibits β-catenin expression also belong to suppressors of WNT/β-catenin signaling down-regulated in HCCs.91,92 WNT/β-catenin signaling can also support the expression of lncRNAs that promote HCC. For example, activation of β-catenin/TCF-4/LINC01278/miRNA-1258/SMAD2/3 feedback loop promotes HCC metastasis.93 However, LINC01278 can also bind to β-catenin protein promoting its proteasomal degradation.94 More information about the role of lncRNAs in mediating WNT/β-catenin in HCC can be found in the review article published recently.95

circRNAs are non-coding RNAs that regulate a wide range of cellular processes such as gene transcription, RNA splicing, and miRNA sponging,96,97 and their aberrant expression contributes to cancer, including HCC.98 Cancer-promoting circRNAs are up-regulated in HCCs, whereas the expression of circRNAs with tumor-suppressing activity is usually reduced in HCCs. circRNA_MTO1 has the potential to suppress tumor progression via the miRNA-541-5p/Zic family member 1 (ZIC1)/WNT/β-catenin axis,99 and circRNA_0004018 by targeting miRNA-626/DKK3,100 but they are down-regulated in HCC. circRNA-ITCH, which is associated with a favorable survival of HCC,101 inhibits the WNT/β-catenin pathway likely via decreasing the level of miRNA-7 and miRNA-214.102 HCC progression associated with re-activation WNT/β-catenin pathway is enhanced by circRNA_104348 via targeting miRNA-187-3p,103 circRNA_ZFR via regulating miRNA-3619-5p/CTNNB1 axis,104 and circRNA_0067934 via regulating miR-1324/FZD5/β-catenin axis.105

miRNAs can affect WNT/β-catenin signaling either directly by binding to the β-catenin transcript or indirectly by regulating upstream mediators of β-catenin. Among tumor-suppressing miRNAs, miR-214 directly targets 3′-UTR of β-catenin RNA.106 The miR-125 b-5p level negatively correlates with HCC progression, and the miR-125 b-5p/STAT3 axis inhibits HCC growth, migration, and invasion by inactivating the WNT/β-catenin pathway.107 miR-1247-5p, which targets WNT3 transcript, is down-regulated in HCCs,108 whereas miRNA-329-3p can suppress proliferation and migration of HCC cells by inhibiting the ubiquitin-specific peptidase 22 (USP22)/WNT/β-catenin axis.109 miRNA-466 exerts its inhibitory effects on HCC progression by regulating formin-like 2 (FMNL2)-mediated activation of WNT/β-catenin signaling.110 Indirect inhibitory effects on the WNT/β-catenin pathway impairing HCC growth and metastasis have been demonstrated for miRNA-26 b, miRNA-342, and miRNA-186. miRNA26b inhibits the expression of zinc ribbon domain-containing 1 (ZNRD1).111 miRNA-342 and miRNA-186 reduce expression of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) and microspherule protein 1 (MCRS1), respectively.112,113 Binding miRNA-629-5p to 3′-UTR of SFRP2 mRNA reduces its expression and activates β-catenin.114 Promotion of HCC metastasis linked with re-activation of WNT/β-catenin signaling has been associated with miRNA-197 targeting negative regulators of this pathway such as naked cuticle 1 (NKD1), AXIN2, and DKK2.115 miRNA-376c-3p and miRNA-19a-3p reduce SOX6 expression and subsequently induce WNT/β-catenin signaling.116 Targeting suppression of tumorigenicity 7 like (ST7L) by miRNA-23 b,117 or inhibition of forkhead box class O family member 1 (FOXO1) by miRNA-96118 activates the AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin signaling. miRNA-5188, whose expression is induced by hepatitis X protein (HBX) and positively correlated with HBV infection, down-regulates FOXO1 expression, thus promoting the activation of WNT signaling and downstream c-JUN expression, which in turn transcriptionally up-regulates miRNA-5188 expression generating a positive feedback loop that promotes HCC stemness and EMT.119

These few examples indicate that most of the non-coding RNAs associated with dysregulation of the WNT/β-catenin pathway can act as tumor promoters re-activating β-catenin signaling in HCC, whereas ncRNAs that exert tumor-suppressive activity are usually down-regulated in HCC (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Modulation of WNT/β-catenin signaling by non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) in HCC. Selected ncRNAs (lncRNAs, circRNAs, miRNAs) with tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressing capacity are shown. Several ncRNAs with tumor-promoting activities are up-regulated in HCC, whereas ncRNAs with suppressing activity are down-regulated in most HCC cases, which limits their suppressive influence on HCC cells. The levels of ncRNAs and proteins in HCC are color-coded: up-regulated ncRNAs, red; down-regulated ncRNAs, blue; proteins with an increased/decreased level in HCC are depicted on a red/blue background, respectively.

Main transduction pathways and regulators interacting with canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling in HCC

Early studies in transgenic mice revealed that an overexpressed mutant β-catenin caused hepatomegaly, but not HCC.120 This suggests that hyperactivation of WNT/β-catenin might be insufficient and a second hit is required for HCC development. In addition, functional modulation of the WNT/β-catenin signaling might result from the dysregulation of other signaling pathways and the crosstalk between HCC cells and stroma cells.121 Hepatic steatosis is often accompanied by macrophage Infiltration, and WNT7a and WNT10a, secreted by these inflammatory cells, re-activate WNT/β-catenin signaling, thus supporting hepatocarcinogenesis.122 HCC-educated macrophages through WNT2b/β-catenin/c-MYC signaling could promote EMT of HCC cells.123 Interestingly, HCC is a sexually dimorphic cancer, with men more likely to develop this disease and have a worse prognosis than women.124 Inhibition of the WNT/β-catenin pathway by estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) has been shown to contribute to protection against HCC incidence and progression in women.125

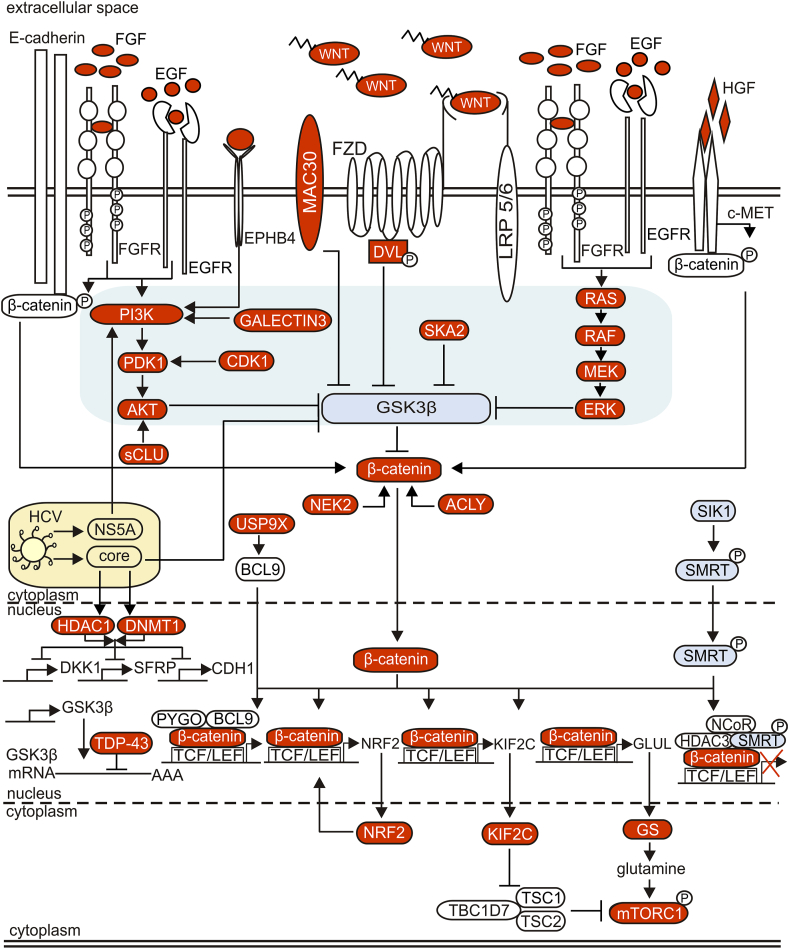

Figure 4 summarizes multiple signal transduction pathways and regulators cooperating with canonical WNT signaling in HCC. Several mechanisms of WNT/β-catenin signaling re-activation are associated with the down-regulation of GSK3β. Spindle and kinetochore-associated protein 2 (SKA2) that induces phosphorylation of GSK3β is overexpressed in HCC,126 galectin-3 by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway leads to inactivation of GSK3β,127 sCLU by increasing the AKT level induces GSK3β phosphorylation,128 meningioma-associated protein 30 (MAC30) contributes to GSK3β inactivation,129 and the trans-activation response DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa (TDP-43) by interfering with GSK3β mRNA inhibits GSK3β translation in HCC cells.130

Figure 4.

Main signal transduction pathways and transcriptional regulators that interact with the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway in HCC. While gain-of-function mutations of CTNNB1 or loss-of-function mutations of AXIN can yield impaired ability of the destruction complex to direct β-catenin to degradation, β-catenin signaling can be also re-activated by multiple interactions of the WNT/β-catenin pathway with other (oncogenic) signaling. These interactions are highly complex and context-dependent, and only some of them have been shown to associate with CTNNB1 mutations. Blocking GSK3β activity (shown on a light grey field) by active signaling pathways such as PI3K/AKT and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK and their upstream modulators plays a central role in CTNNB1 mutation-unrelated β-catenin re-activation in HCC. Environmental factors such as viruses can also modify interactions between major signaling pathways leading to enhanced activation of β-catenin, closely associated with hepatocarcinogenesis. Aberrant activation of different pathways including the WNT/β-catenin pathway by proteins of HCV is shown as an example. All these multiple interactions between diverse signaling pathways indicate that while targeting the WNT/β-catenin pathway alone might be insufficient therapeutic approach, a cooperation between WNT signaling and other signaling pathways might be exploited to develop novel therapeutic strategies.

WNT/β-catenin signaling is a key pathway in HCV-positive HCC.131 The HCV genome encodes a single polyprotein cleaved into 10 mature proteins, and 3 of them mediate activation of WNT/β-catenin signaling. HCV core protein is known to induce hepatocarcinogenesis by facilitating WNT/β-catenin signaling in hepatocytes.132 Core enhances β-catenin nuclear stabilization by inactivating GSK3β,132 and decreasing expression of WNT inhibitors SFRPs and DKK1 via up-regulation and recruitment of DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) and histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) to their promoter regions.61,133 Core also represses expression of E-cadherin via up-regulation of DNMT1 that leads to hypermethylation of CDH1 promoter,134 and down-regulation of E-cadherin influences the level of cytoplasmic β-catenin. Another HCV protein, nonstructural protein 5 A (NS5A) activates PI3K/AKT signaling leading to the inactivation of GSK3β and re-activation of WNT/β-catenin signaling.135 NS5A can also stabilize β-catenin directly.136 A crosstalk between re-activated WNT/β-catenin signaling and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) is an important part of HCV-induced HCC development.137 HCV induces the binding of EGF and FGF to EGFR and FGFR, respectively.131 Canonical WNT signaling and EGFR pathways activate each other, as binding of WNTs to FZD and LRP5/6 receptors transactivates EGFR signaling by matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-mediated release of soluble EGFR ligands, whereas EGFR signaling by stimulating PI3K/AKT and RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK cascades promotes β-catenin signaling through GSK3β inhibition.131 Moreover, EGFR and FGFR signaling can directly induce phosphorylation of β-catenin at residue Tyr654, thus destabilizing the binding between β-catenin and E-cadherin, thereby releasing β-catenin for nuclear signaling.131 WNT/β-catenin signaling can be also modulated by mesenchymal–epithelial transition factor (c-MET). c-MET is the receptor for a hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and the HGF/c-MET axis is involved in proliferation, differentiation, invasion, angiogenesis, and apoptosis.138,139 Aberrant activation of c-MET promotes both the initiation and metastasis of HCC and plays a crucial role in the development of resistance to treatment.140 Coordinated mutation of CTNNB1 and c-MET activation have been detected in about 11% of HCC samples.141 Moreover, β-catenin is associated with c-MET at the cell membrane, and upon HGF binding c-MET phosphorylates β-catenin leading to its dissociation from c-MET, cellular stabilization, and nuclear translocation.141,142

Diverse endogenous inhibitors of WNT, e.g., DKK1, SFRP1, SFRP4, SFRP5, and kallistatin are down-regulated in HCC, which enhances the interaction of WNT with their receptors and β-catenin re-activation.143, 144, 145 Reduced expression of kallistatin in HCC cells associates with increased β-catenin nuclear localization and decreased level of βII-Spectrin (SPTBN1), an adapter protein for SMAD3/SMAD4 complex formation.143 Never in mitosis gene-A (NIMA)-related expressed kinase 2 (NEK2) is up-regulated in HCC tissue, especially in advanced-stage disease, and overexpression of NEK2 can block β-catenin proteasomal degradation.146 Erythropoietin-producing hepatocyte receptor B4 (EPHB4) is involved in HCC cell migration and HCC progression by regulating β-catenin-mediated EMT.147 An elevated level of ubiquitin-specific peptidase 9 X-linked (USP9X) promotes the proliferation of HCC cells by regulating β-catenin expression.148 The USP9X-mediated BCL9 deubiquitination promotes the formation of the β-catenin-BCL9-PYGO complex leading to the increased transcriptional activity of β-catenin.149 Silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor (SMRT) when phosphorylated recruits nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR) to the promoter regions of β-catenin target genes, and inhibits their transcription.150 This, however, is inhibited in HCCs, because salt-inducible kinase 1 (SIK1), which phosphorylates SMRT and promotes its nuclear translocation is down-regulated in HCCs.150 Prospero-related homeobox 1 (PROX1) up-regulates expression of CTNNB1 by promoter stimulation, and PROX1 and β-catenin levels positively correlate in HCC tissues.151 HCC is a heterogenous tumor and some of these interactions are associated with a specific genetic background. Coordinated c-MET activation with CTNNB1 mutations is mentioned above.141 Another example is the nuclear erythroid 2 p45-related factor 2 (NRF2) detoxification pathway, which is enhanced in HCCs harboring CTNNB1 mutations.152 Concomitant CTNNB1 mutations and NRF2 activation has been detected in 9% of HCCs.153 As activation of β-catenin triggers pro-oxidative status and increases expression of NFE2L2, cooperation between activated β-catenin signaling and the NRF2 pathway might be therapeutically exploited in the context of redox balance. A positive relationship has been found between mutation-driven β-catenin activation and p-mTOR-S2448, which is an indicator of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) activation.154 Activating β-catenin mutations lead to increased expression of GLUL encoding glutamine synthetase (GS), which causes excessive glutamine levels, and in turn mTORC1 activation.154 This suggests a possible therapeutic benefit of mTORC1 inhibition in HCCs with mutated CTNNB1. mTORC1 signaling can be also activated by kinesin family member 2C (KIF2C), a direct target of the activated WNT/β-catenin pathway. KIF2C is up-regulated in HCCs and associated with poorer prognosis.155 Mechanistically, KIF2C binds to Tre2-Bub2-Cdc16 (TBC) 1 domain family, member 7 (TBC1D7), which is a part of TSC complex consisting of TBC1D7, tuberous sclerosis complex 1 (TSC1), and TSC2. TSC complex negatively regulates mTORC1 signaling. The interaction of KIF2C with TBC1D7 in HCC leads to the dissociation of the TSC complex, which in turn promotes mTORC1 signaling.155

Canonical WNT signaling and liver cancer stem cells (LCSCs)

HCC is a heterogeneous tumor, both at the histopathological and molecular levels. Extensive heterogeneity of the HCC is associated with the gradual loss of differentiation phenotype and acquisition of stemness properties.16, 17, 18, 19 While in well-differentiated HCC, high expression of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha (HNF4α) is accompanied by low expression of β-catenin and its targets,156 a subset of HCC cells with stem cell properties named LCSCs are largely controlled by the WNT/β-catenin pathway.16, 17, 18, 19 The nuclear accumulation of β-catenin is associated with an elevated level of epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) in the subpopulation of HCC exerting self-renewal potential, invasiveness, distant metastases, and early tumor recurrence.157,158 EpCAM is listed among the surface proteins (CD133, CD44, CD13, CD90, OV-6, CD47) that have been identified as markers of the LCSC subpopulation.16 Expansion of CD133-positive LCSCs has been found as regulated by Src-homology 2 domain-containing phosphatase 2 (Shp 2) with the β-catenin contribution.159 HCC cells grown as spheroids have shown an elevated level of β-catenin and significantly increased expression of LCSC markers, including EpCAM, CD44, CD133, and CD90.160,161 β-catenin signaling is involved in maintaining stem cell-like features of HCCs in collaboration with several proteins, including proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA)-associated factor (PAF),162 non-muscle myosin heavy chain IIA (MYH9),163 Krüppel-like factor 8 (KLF8),164 and a novel HCC stem cell marker, brain-expressed X-linked protein 1 (BEX1) that blocks RUNX3 otherwise down-regulating β-catenin level.165 ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY) stabilizes β-catenin by Lys 49 acetylation, and ACLY-regulated β-catenin level modulates stemness in HCC.166 Granulin-epithelin precursor (GEP) is another marker of stemness tightly associated with β-catenin levels in HCC clinical specimens.167 A positive TCF1/EPH receptor B2 (EPHB2)/β-catenin feedback loop has been shown to regulate HCC stemness and drug resistance.168 Stemness phenotype of HCC has been also associated with the high level of glutaminase 1 (GLS1) in the mitochondria, and targeting GLS1 contributes to the suppression of stemness properties by increasing ROS accumulation and reducing the β-catenin activity.169 Protein tyrosinase kinase 2 (PTK2), which supports nuclear localization of β-catenin, is suggested to act as an oncogene enhancing LCSC traits in HCC.170 Secretory clusterin (sCLU) has been demonstrated to promote LCSC properties through AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin axis, and the subset of HCC patients with co-expression of β-catenin and sCLU had the poorest prognosis.128 Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) has been found to increase the expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1), induce WNT signaling, and up-regulate OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG, which are essential for the stemness phenotype.171

Various functions of LCSCs are regulated by the ncRNAs/WNT/β-catenin axis.17,172,173 miR-5188 stimulates nuclear translocation of β-catenin and HCC stemness.119 miR-1246 via suppression of AXIN2 and GSK3β activates WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway and promotes stemness properties in CD133+ subpopulation.174 lncTCF7 supports self-renewal of LCSCs via activation of TCF7 expression through recruitment of the SWI/SNF complex to the promoter of TCF7.175 SAMMSON and lncRNA β-catenin methylation (lnc-β-Catm) promote stemness of HCCs via EZH2-dependent enhancement of β-catenin stability and activity,176,177 whereas lncAPC supports LCSC self-renewal via EXH2-mediated transcriptional inhibition of APC.178 Testis-associated highly conserved oncogenic long non-coding RNA (THOR) enhances the self-renewal capacity of liver CSCs by regulation of β-catenin signaling.179 All above indicates that the hyperactivated WNT/β-catenin pathway plays an indispensable role in maintaining the stemness of HCC, which is also well documented in other cancers.180

A short overview of the role of WNT/β-catenin signaling in metabolic reprogramming of HCC cells

Genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, phosphoproteomic, and metabolomic analyses of HCCs across etiologies and clinical stages led to the identification of several patient group-specific differences, however, due to the HCC heterogeneity application of these approaches in the patient stratification is still questionable. Therefore, clinically useful HCC classification based on molecular data is an important direction of worldwide efforts. Three types of molecular classification of HCC consider: (i) proliferative vs. non-proliferative (differentiated) status of HCC; (ii) HCC microenvironment and immunity; and (iii) metabolic reprograming.181 CTNNB1 mutation and activity of WNT/β-catenin signaling are considered in each of these classifications.

Growing evidence indicates that metabolic reprograming contributes to HCC initiation and progression. The impact of CTNNB1 mutations and enhanced β-catenin activity on metabolic reprograming is a complex issue as WNT/β-catenin signaling plays a crucial role also in the liver physiology, in the formation of liver tissue and maintenance of metabolic zonation in the hepatic lobules.182 Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 α (HNF4α) and β-catenin govern liver zonation with the differential spreading of metabolic function between the HNF4α-regulated periportal region and β-catenin-regulated perivenous region. β-catenin contributes to the development of diet-induced fatty liver, regulates the zonal distribution of steatosis on the high-fat diet, and affects hepatic fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and ketogenesis.183 Therefore, the metabolic reprograming in HCC is more complex than just a shift from oxidative to glycolytic bioenergetic metabolism. It has been shown that β-catenin-activated HCCs are not glycolytic and do not follow the Warburg effect but oxidase fatty acids at high rates, which is regulated by transcription factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), a β-catenin target.184 This might explain why β-catenin-activated HCCs do not display steatosis. While various cancers exert high plasticity in metabolic reprograming, β-catenin-activated HCCs represent a metabolic inflexibility, and therefore metabolic inhibitors of FAO may be considered as a potential therapy for this type of HCC.184 In recently published analyses comparing CTNNB1-mutant and CTNNB1-wild-type HCCs, among 3067 differentially expressed transcripts and 23 differentially expressed proteins, GLUL encoding glutamine synthetase, AMACR encoding α-methylacyl-CoA racemase, and ACSS3 encoding Acyl-CoA synthetase short-chain family member 3 (ACSS3) differentially expressed at both protein and transcript levels,185 have been already associated with CTNBB1 mutations in HCC.186,187 Glutamine synthetase has been shown to enhance HCC development by hyperactivating mTORC1 in a mouse model of β-catenin-driven HCC,179 and most recently increased expression of this enzyme and defective urea cycle has been detected in CTNNB1-mutated HCCs.188

Metabolic reprograming in the response to up-regulation of WNT/β-catenin signaling unrelated to CTNNB1 mutation has been also reported. For example, nucleotide diphosphate kinase 7 (NME7, nonmetastatic cells 7) can activate WNT/β-catenin signaling, which results in the up-regulation of methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase (MTHFD2) and promotion of one-carbon metabolism and the rapid division of cancer cells.189 A significant correlation has been found between expression levels of gankyrin and β-catenin in HCC biopsies.190 Gankyrin can stimulate glycolysis and glutaminolysis through up-regulating β-catenin and its downstream target c-MYC.190

Other aspects of metabolic reprograming in HCC, mostly unrelated to CTNBB1 mutations and enhanced β-catenin activity have been reviewed elsewhere.191, 192, 193, 194

A short overview of the role of WNT/β-catenin signaling in immune evasion and response to immunotherapy

Various aspects of the WNT/β-catenin signaling contribution to the crosstalk between HCC cells and diverse immune and stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment have been summarized recently.195,196 WNTs derived from HCC cells can activate WNT/β-catenin signaling in macrophages and promote their polarization to pro-tumorigenic M2-like phenotype.197 Mechanistically, LINC00662 by binding miR-15a/miR-16/miR-107 can up-regulate expression and secretion of WNT3a from HCC cells, thus activating WNT/β-catenin signaling in HCC cells and macrophages.75 WNT/β-catenin signaling can influence antitumor immunity. In the molecular and immunological classification of HCC, a CTNNB1-mutated subtype is characterized as immunosuppressive,198,199 and the correlation between a functional mutation of CTNNB1 and exclusion of immune cells has been demonstrated.200, 201, 202 Using a genetically engineered mouse model, it has been demonstrated that HCC can escape the immune response by up-regulating β-catenin, which is accompanied by a defective recruitment of dendritic cells (DCs), and as a consequence impaired activity of T cells.201 The immune surveillance can be restored by the expression of C–C motif chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5).201 A CTNNB1 mutation leading to up-regulation of β-catenin has been related to the suppression of tumor microenvironment infiltration by CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and DCs, and this limited immune cell migration into tumor has been associated with down-regulation of chemokine expression mediated by differential expression of miRNAs.202

The approved systemic therapies for advanced HCC include immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs),203 however, the clinical efficacy of ICIs is limited to a subset of HCC patients. Growing evidence indicates that the low effectiveness of immune checkpoint blockers such as anti-PD-1 therapy might be related to a subgroup of HCCs with mutations in CTNNB1.201,204 Most recently published WNT signature-related prognostic model predicting the survival time of HCC patients provides a further indication on the significant influence of the WNT/β-catenin pathway on immunotherapy outcomes.205 Mutation in CTNNB1 has been also considered in the prognostic model predicting the efficacy of immunotherapy in the aging microenvironment.206 Thus, (i) enhanced β-catenin activity promoting immune evasion and resistance to immunotherapies might be a potential biomarker for HCC patient exclusion, and/or (ii) combined treatment with WNT/β-catenin inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors might be a better therapeutic option than either treatment alone.201, 202, 203, 204, 205, 206

Targeting WNT/β-catenin signaling for tHCC treatment, challenges and hopes

HCC is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide207 with limited treatment options.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13,208,209 Given the important role of the WNT/β-catenin pathway in HCC, targeting this signaling is considered an attractive therapeutic option. Various approaches used in preclinical and clinical studies, aiming to modulate diverse pathway components are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 5. Although preclinical studies have shown promising effects of small molecules, monoclonal antibodies, and plant-derived agents, only a few of those agents have entered clinical trials. DKK1 is one of the most studied targets in many cancer types, and DKK1-neutralizing monoclonal antibody DKN-01 is currently being investigated in HCC patients (NCT03645980). The mechanism by which DKK1, the antagonist of WNT/β-catenin signaling, exerts its cancer-promoting activity is unknown.210 Targeting early steps of the WNT/β-catenin pathway with e.g., inhibitors of WNTs, porcupine (PORCN), or tankyrase (TNKS) might be ineffective for HCC patients that harbor either gain-of-function mutations in CTNNB1 or loss-of-function mutations in AXIN. Therefore, blocking the interaction of β-catenin with its nuclear co-factors seems to be a more universal strategy. In ongoing clinical trials, E7386, an orally active inhibitor of the interaction between β-catenin and CBP is currently investigated in combination with either lenvatinib (NCT04008797) or pembrolizumab (NCT05091346). The clinical development of WNT/β-catenin pathway inhibitors for HCC patients has serious limitations. Firstly, the WNT/β-catenin pathway plays an essential role in liver homeostasis and regeneration and severe adverse effects associated with blocking its activity are still an unresolved problem. Secondly, as the WNT/β-catenin pathway coordinates a very complex, largely uncovered network of interactions in the healthy and diseased liver, targeting WNT/β-catenin alone might be insufficient to trigger HCC regression.

Table 1.

Clinical (https://clinicaltrials.gov) and preclinical studies of agents targeting the WNT/β-catenin pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Agent | Company | Target/mode of action | Trial identifier (phase/status) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E7386 combined with lenvatinib | Eisai Inc. | inhibitor of the interaction between β-catenin and CBP | NCT04008797 (phase 2/recruiting) | – |

| E7386 combined with pembrolizumab | Eisai Inc. | inhibitor of the interaction between β-catenin and CBP | NCT05091346 (phase 2/recruiting) | – |

| CGX1321 | Curegenix Inc. | porcupine inhibitor | NCT03507998 (Phase 1/recruiting) | 220 |

| DKN-01-mAb (monotherapy or combined with sorafenib) | Gutenberg University Mainz | DKK1 inhibitor | NCT03645980 (Phase 1/2/recruiting) | – |

| OMP-54F28 (ipafricept) with sorafenib | OncoMed Pharmaceuticals | decoy fusion protein to compete with FZD8 for WNT ligand binding | NCT02069145 (Phase 1/completed) | – |

| all trans retinoic acid (ATRA) | – | PI3K/AKT/GSK3 β pathway inhibition | preclinical | 221 |

| aplykurodin A | – | β-catenin proteasomal degradation | preclinical | 222 |

| aspirin (ASP) | – | TCF4/LEF1 downregulation | preclinical | 223 |

| bruceine D (BD) | – | ICAT/β-catenin inhibitor | preclinical | 224 |

| canagliflozin (CANA) | – | PP2A mediated β-catenin phosphorylation | preclinical | 225 |

| compound from Phyllanthus urinariaL | – | inhibition of AKT/GSK3 β pathway | preclinical | 226 |

| curcumin | – | GPC3/WNT/β-catenin inhibition | preclinical | 227 |

| CWP232228 | – | β-catenin-TCF interaction | preclinical | 228 |

| evodiamine | – | inhibition of nuclear translocation of β-catenin | preclinical | 229 |

| FH535 | – | β-catenin/TCF mediated transcription | preclinical | 230 |

| homoharringtonine (HHT) | – | inhibition of EPHB4/PI3K/AKT GSK3 β pathway | preclinical | 172 |

| niclosamide-loaded polymeric micelles (NIC-NPs) | – | WNT3a, DVL and LRP5/6 inhibitor | preclinical | 231 |

| NVP-TNKS656 | – | tankyrase inhibitor | preclinical | 232 |

| Peg-IFN | – | RANBP3 mediated nuclear export of β-catenin | preclinical | 233 |

| pimozide (PMZ) | – | inhibition of PKA/GSK3 β pathway | preclinical | 234 |

| PRI-724 | – | β-catenin-CBP interaction | preclinical | 235 |

| quercetin | – | FZD7 | preclinical | 236 |

| RHPD-P1 | – | FZD7-DVL interaction | preclinical | 237 |

| RO3306 | – | inhibition of CDK1/PDK1/β-catenin axis | preclinical | 136 |

| salinomycin (sal) | – | GSK3β activation | preclinical | 238 |

| sFZD7 | – | FZD7 decoy receptor for WNT ligand binding | preclinical | 239 |

| shizukaol D | – | DVL and LRP5/6 inhibitor | preclinical | 240 |

| WM130 | – | GSK3 β activation inhibition of AKT/GSK3 β axis | preclinical | 241 |

| WNT1-Ab | – | anti-WNT1 polyclonal antibody | preclinical | 242 |

| WXL-8 | – | tankyrase inhibitor | preclinical | 243 |

| XAV939 | – | tankyrase inhibitor | preclinical | 243 |

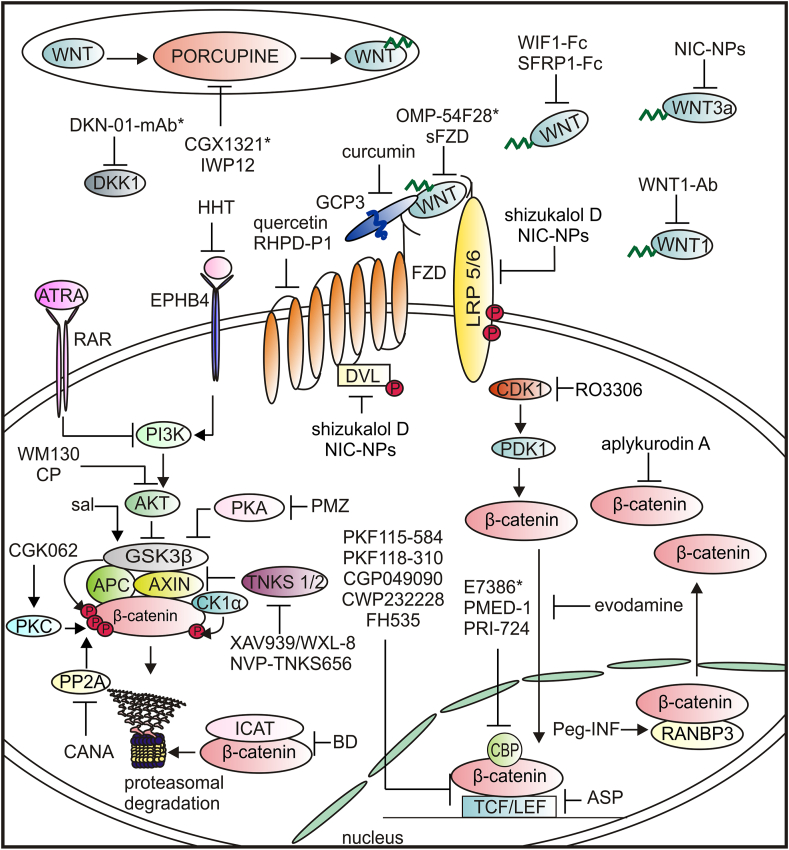

Figure 5.

Agents affecting the WNT signaling that have been investigated in hepatocellular carcinoma (∗an agent in clinical trial). ASP, aspirin; ATRA, all-trans retinoic acid; BD, bruceine D; CANA, canagliflozin; CP, compound from Phyllanthus urinaria L.; GPC3, glypican 3; HHT, homoharringtonine; ICAT, inhibitor of beta-catenin and T cell factor; NIC-NPs, niclosamide-loaded polymeric micelles; Peg-IFN, pegylated-Interferon-α2a; PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C; PMZ, pimozide; PP2A, protein phosphatase 2 A; RANBP3, RAN binding protein 3; RAR, retinoic acid receptor; sal, salinomycin; TKNS, tankyrase.

Non-coding RNA-targeted therapies

Aberrantly regulated ncRNAs are emerging as attractive targets for novel anticancer treatment modalities.211,212 Diverse RNA-based therapies have been developed, including small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs), anti-miRNAs (antimiRs), miRNA sponges, miRNA mimics, and CRISPR-Cas9-based editing.213 While FDA and/or EMA approved 12 RNA therapeutics, mainly aiming at gene modification in the liver, none of them is approved for treating cancer patients.211 Several RNA therapeutics, mainly antimiRs and miRNA mimics, are under clinical investigation.211 While there are no RNA therapeutics in clinical development against HCC, anti-miR-122 (Miravirsen, SPC3649) is investigated in phase II against HCV infection (NCT01646489, NCT01727934, NCT01872936, NCT01200420), a common cause of HCC. Preclinical studies of using RNA technology against HCC are continued, and components of WNT/β-catenin signaling are still considered possible targets. For example, miR-125 b-5p which suppresses EMT and LCSCs has been recently used as MRI-visible nanomedicine that identifies folate receptors internalized by HCC cells.107 One of the main problems restricting the exploitation of ncRNA in clinics is the safety and efficacy of their delivery to cancer cells. Several delivery strategies are under investigation,214 and rapid development of various RNA strategies against COVID-19 might be supportive.

Conclusions and future perspectives

HCC is a complex disease and highly heterogenous with molecular subtypes identified based on genetic profiling. Mutations of CTNNB1 belong to the most common genetic abnormalities in HCCs. Up-regulation of WNT/β-catenin signaling contributes to the generation of LCSCs with sustained self-renewing growth properties, cancer initiation, and progression. Considering the indispensable role of WNT/β-catenin signaling in HCC progression, different strategies targeting this pathway in HCC have been evaluated in preclinical studies and clinical trials. The successful therapeutic modulation of the canonical WNT signaling pathway is, however, limited by the complexity of this pathway, and its crucial role in liver development, homeostasis, metabolic zonation, regeneration, and the crosstalk with other signaling cascades. Therefore, it is rather implausible that in the coming years, the enhanced activity of the WNT/β-catenin signaling will be therapeutically inhibited in HCC patients. On the other hand, growing evidence indicates that the presence of CTNNB1 mutations may serve as a biomarker stratifying the patients for immune and targeted therapies.201,204,215, 216, 217, 218 In this respect, cooperation between WNT/β-catenin signaling and other signaling pathways can be exploited. For example, β-catenin activation results in mTORC1 activation, and since it has been shown that CTNNB1-mutated HCC is addicted to mTORC1 for metabolism, the selection of patients with mutations in CTNNB1 might improve the efficacy of mTOR inhibitors against HCCs.179 The estimation of the mutation status of the WNT/β-catenin pathway might be also helpful to match patients to immunotherapy. For example, a subgroup of HCCs with mutations in CTNNB1 has been associated with low effectiveness of immune checkpoint blockers such as anti-PD-1 therapy.201,204 This suggests that the assessment of CTNNB1 mutations may be useful for identifying the patients for whom immunotherapy would not be beneficial.215, 216, 217, 218 In recently released efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150 (NCT03434379), atezolizumab plus bevacizumab showed clinically meaningful survival benefit over sorafenib, 11 but no genetic analysis has been implemented in the patient exclusion process. Interestingly, patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)-driven HCC treated with anti-PD1 or anti-PDL1 have shown lower overall survival compared to patients with other etiologies.219 Thus, the question about the mutation status of HCCs in these or other clinical trials remains open, and the idea of clinical trials conducted separately for HCCs with wild-type and mutated CTNNB1 becomes attractive. This underlines the potential implications of prospective genotyping of HCC in guiding clinical decisions on matching patients to immune and targeted therapies.204 In conclusion, while our understanding of the role of WNT/β-catenin signaling in HCC remains incomplete, the assessment of alterations in genes encoding components of this signaling pathway in HCC specimens might enable better molecular classification of HCC and more detailed stratification of patients for treatments as well as identification of novel drugs exerting therapeutic efficacy in a subset of HCC patients.

Author contributions

AG-M collected the related papers, wrote the first draft, and prepared figures. MC conceptualized and wrote this review. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the research funding of the Medical University of Lódz (No. 503/1-156-01/503-11-001).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chongqing Medical University.

References

- 1.Ghouri Y.A., Mian I., Rowe J.H. Review of hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, etiology, and carcinogenesis. J Carcinog. 2017;16:1. doi: 10.4103/jcar.JCar_9_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desjonqueres E., Campani C., Marra F., et al. Preneoplastic lesions in the liver: molecular insights and relevance for clinical practice. Liver Int. 2022;42(3):492–506. doi: 10.1111/liv.15152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag H.B. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(6):1264–1273. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang D.Q., El-Serag H.B., Loomba R. Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(4):223–238. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-00381-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daher S., Massarwa M., Benson A.A., et al. Current and future treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: an updated comprehensive review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2018;6(1):69–78. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2017.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rimassa L., Pressiani T., Merle P. Systemic treatment options in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2019;8(6):427–446. doi: 10.1159/000499765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wehrenberg-Klee E., Goyal L. Combining systemic and local therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(12):976–978. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00388-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roudi R., D’Angelo A., Sirico M., et al. Immunotherapeutic treatments in hepatocellular carcinoma; achievements, challenges and future prospects. Int Immunopharm. 2021;101(Pt A):108322. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.108322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Z., Liu X., Liang J., et al. Immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: current status and future prospects. Front Immunol. 2021;12:765101. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.765101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu X.D., Li K.S., Sun H.C. Adjuvant therapies after curative treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma: current status and prospects. Genes Dis. 2020;7(3):359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2020.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng A.L., Qin S., Ikeda M., et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2022;76(4):862–873. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordan J.D., Kennedy E.B., Abou-Alfa G.K., et al. Systemic therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(36):4317–4345. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong K.M., King G.G., Harris W.P. The treatment landscape of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2022;24(7):917–927. doi: 10.1007/s11912-022-01247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marquardt J.U., Andersen J.B., Thorgeirsson S.S. Functional and genetic deconstruction of the cellular origin in liver cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(11):653–667. doi: 10.1038/nrc4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimri M., Satyanarayana A. Molecular signaling pathways and therapeutic targets in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers. 2020;12(2):491. doi: 10.3390/cancers12020491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y.C., Yeh C.T., Lin K.H. Cancer stem cell functions in hepatocellular carcinoma and comprehensive therapeutic strategies. Cells. 2020;9(6):1331. doi: 10.3390/cells9061331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J., Zhu Y. Recent advances in liver cancer stem cells: non-coding RNAs, oncogenes and oncoproteins. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:548335. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.548335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang X., Yan Q., Liu S., et al. Cancer stem cells in hepatocellular carcinoma: intrinsic and extrinsic molecular mechanisms in stemness regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(20):12327. doi: 10.3390/ijms232012327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lv D., Chen L., Du L., et al. Emerging regulatory mechanisms involved in liver cancer stem cell properties in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:691410. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.691410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raja A., Haq F. Molecular classification of hepatocellular carcinoma: prognostic importance and clinical applications. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2022;148(1):15–29. doi: 10.1007/s00432-021-03826-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khalaf A.M., Fuentes D., Morshid A.I., et al. Role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma, pathogenesis, and clinical significance. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2018;5:61–73. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S156701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perugorria M.J., Olaizola P., Labiano I., et al. Wnt–β-catenin signalling in liver development, health and disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16(2):121–136. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nusse R., Clevers H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell. 2017;169(6):985–999. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gajos-Michniewicz A., Czyz M. WNT signaling in melanoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(14):4852. doi: 10.3390/ijms21144852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu F., Yu C., Li F., et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in cancers and targeted therapies. Signal Transduct Targeted Ther. 2021;6:307. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00701-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiremath I.S., Goel A., Warrier S., et al. The multidimensional role of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in human malignancies. J Cell Physiol. 2022;237(1):199–238. doi: 10.1002/jcp.30561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grumolato L., Liu G., Mong P., et al. Canonical and noncanonical Wnts use a common mechanism to activate completely unrelated coreceptors. Genes Dev. 2010;24(22):2517–2530. doi: 10.1101/gad.1957710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Amerongen R., Mikels A., Nusse R. Alternative Wnt signaling is initiated by distinct receptors. Sci Signal. 2008;1(35):re9. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.135re9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niehrs C. The complex world of WNT receptor signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(12):767–779. doi: 10.1038/nrm3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fan J., Wei Q., Liao J., et al. Noncanonical Wnt signaling plays an important role in modulating canonical Wnt-regulated stemness, proliferation and terminal differentiation of hepatic progenitors. Oncotarget. 2017;8(16):27105–27119. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huber A.H., Weis W.I. The structure of the β-catenin/E-cadherin complex and the molecular basis of diverse ligand recognition by β-catenin. Cell. 2001;105(3):391–402. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mao B., Wu W., Davidson G., et al. Kremen proteins are Dickkopf receptors that regulate Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Nature. 2002;417(6889):664–667. doi: 10.1038/nature756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawano Y., Kypta R. Secreted antagonists of the Wnt signalling pathway. J Cell Sci. 2003;116(Pt 13):2627–2634. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jang E.S., Jeong S.H., Kim J.W., et al. Diagnostic performance of alpha-fetoprotein, protein induced by vitamin K absence, osteopontin, dickkopf-1 and its combinations for hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2016;11(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suda T., Yamashita T., Sunagozaka H., et al. Dickkopf-1 promotes angiogenesis and is a biomarker for hepatic stem cell-like hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5):2801. doi: 10.3390/ijms23052801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mukherjee A., Dhar N., Stathos M., et al. Understanding how Wnt influences destruction complex activity and β-catenin dynamics. iScience. 2018;6:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carmon K.S., Gong X., Lin Q., et al. R-spondins function as ligands of the orphan receptors LGR4 and LGR5 to regulate Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(28):11452–11457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106083108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Lau W., Peng W.C., Gros P., et al. The R-spondin/Lgr5/Rnf43 module: regulator of Wnt signal strength. Genes Dev. 2014;28(4):305–316. doi: 10.1101/gad.235473.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ring A., Kim Y.M., Kahn M. Wnt/catenin signaling in adult stem cell physiology and disease. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2014;10(4):512–525. doi: 10.1007/s12015-014-9515-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopez-Bergami P., Barbero G. The emerging role of Wnt5a in the promotion of a pro-inflammatory and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020;39(3):933–952. doi: 10.1007/s10555-020-09878-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Geng M., Cao Y.C., Chen Y.J., et al. Loss of Wnt5a and Ror2 protein in hepatocellular carcinoma associated with poor prognosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(12):1328–1338. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i12.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang T., Liu X., Wang J. Up-regulation of Wnt5a inhibits proliferation and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J Cancer Res Therapeut. 2019;15(4):904–908. doi: 10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_886_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wakizaka K., Kamiyama T., Wakayama K., et al. Role of Wnt5a in suppressing invasiveness of hepatocellular carcinoma via epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncol Lett. 2020;20(5):268. doi: 10.3892/ol.2020.12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y., Deng H., Liang L., et al. Depletion of VPS35 attenuates metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma by restraining the Wnt/PCP signaling pathway. Genes Dis. 2021;8(2):232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2020.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de La Coste A., Romagnolo B., Billuart P., et al. Somatic mutations of the beta-catenin gene are frequent in mouse and human hepatocellular carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(15):8847–8851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim S., Jeong S. Mutation hotspots in the β-catenin gene: lessons from the human cancer genome databases. Mol Cell. 2019;42(1):8–16. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2018.0436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gonzalez F.J. Role of beta-catenin in the adult liver. Hepatology. 2006;43(4):650–653. doi: 10.1002/hep.21154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miyoshi Y., Iwao K., Nagasawa Y., et al. Activation of the beta-catenin gene in primary hepatocellular carcinomas by somatic alterations involving exon 3. Cancer Res. 1998;58(12):2524–2527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elmileik H., Paterson A.C., Kew M.C. β-catenin mutations and expression, 249serine p53 tumor suppressor gene mutation, and hepatitis B virus infection in southern African Blacks with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91(4):258–263. doi: 10.1002/jso.20304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ding S.L., Yang Z.W., Wang J., et al. Integrative analysis of aberrant Wnt signaling in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(20):6317–6328. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i20.6317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schulze K., Imbeaud S., Letouzé E., et al. Exome sequencing of hepatocellular carcinomas identifies new mutational signatures and potential therapeutic targets. Nat Genet. 2015;47(5):505–511. doi: 10.1038/ng.3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Amit S., Hatzubai A., Birman Y., et al. Axin-mediated CKI phosphorylation of beta-catenin at Ser 45: a molecular switch for the Wnt pathway. Genes Dev. 2002;16(9):1066–1076. doi: 10.1101/gad.230302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rebouissou S., Franconi A., Calderaro J., et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation of CTNNB1 mutations reveals different ß-catenin activity associated with liver tumor progression. Hepatology. 2016;64(6):2047–2061. doi: 10.1002/hep.28638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu P., Liang B., Liu M., et al. Oncogenic mutations in Armadillo repeats 5 and 6 of β-catenin reduce binding to APC, increasing signaling and transcription of target genes. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(4):1029–1043. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.11.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou Q., Li Z., Song L., et al. Whole-exome mutational landscape of metastasis in patient-derived hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Genes Dis. 2020;7(3):380–391. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Satoh S., Daigo Y., Furukawa Y., et al. AXIN1 mutations in hepatocellular carcinomas, and growth suppression in cancer cells by virus-mediated transfer of AXIN1. Nat Genet. 2000;24(3):245–250. doi: 10.1038/73448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bugter J.M., Fenderico N., Maurice M.M. Mutations and mechanisms of WNT pathway tumour suppressors in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21(1):5–21. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-00307-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jackstadt R., Hodder M.C., Sansom O.J. WNT and β-catenin in cancer: genes and therapy. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 2020;4:177–196. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rebouissou S., Nault J.C. Advances in molecular classification and precision oncology in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2020;72(2):215–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Longerich T., Endris V., Neumann O., et al. RSPO2 gene rearrangement: a powerful driver of β-catenin activation in liver tumours. Gut. 2019;68(7):1287–1296. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yin X., Yi H., Wang L., et al. R-spondin 2 promotes proliferation and migration via the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(2):1757–1765. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hamilton J.P. Epigenetic mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of hepatobiliary malignancies. Epigenomics. 2010;2(2):233–243. doi: 10.2217/epi.10.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Quan H., Zhou F., Nie D., et al. Hepatitis C virus core protein epigenetically silences SFRP1 and enhances HCC aggressiveness by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene. 2014;33(22):2826–2835. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deng Y., Yu B., Cheng Q., et al. Epigenetic silencing of WIF-1 in hepatocellular carcinomas. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;136(8):1161–1167. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0763-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ding Z., Qian Y.B., Zhu L.X., et al. Promoter methylation and mRNA expression of DKK-3 and WIF-1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(21):2595–2601. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin Y.F., Li L.H., Lin C.H., et al. Selective retention of an inactive allele of the DKK2 tumor suppressor gene in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Takagi H., Sasaki S., Suzuki H., et al. Frequent epigenetic inactivation of SFRP genes in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(5):378–389. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li D., Fan X., Li Y., et al. The paradoxical functions of long noncoding RNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma: implications in therapeutic opportunities and precision medicine. Genes Dis. 2022;9(2):358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2020.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang D., Chen F., Zeng T., et al. Comprehensive biological function analysis of lncRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes Dis. 2021;8(2):157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2019.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tang Q., Zheng X., Zhang J. Long non-coding RNA CRNDE promotes heptaocellular carcinoma cell proliferation by regulating PI3K/Akt/β-catenin signaling. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;103:1187–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.04.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yao X., You G., Zhou C., et al. LncRNA ASB16-AS1 promotes growth and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma through regulating miR-1827/FZD4 axis and activating Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:9371–9378. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S220434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 72.Lei T., Zhu X., Zhu K., et al. EGR1-induced upregulation of lncRNA FOXD2-AS1 promotes the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma via epigenetically silencing DKK1 and activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Cancer Biol Ther. 2019;20(7):1007–1016. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2019.1595276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Koo J.I., Lee H.J., Jung J.H., et al. The pivotal role of long noncoding RNA RAB5IF in the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma via LGR5 mediated β-catenin and c-Myc signaling. Biomolecules. 2019;9(11):718. doi: 10.3390/biom9110718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liang W., Shi C., Hong W., et al. Super-enhancer-driven lncRNA-DAW promotes liver cancer cell proliferation through activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021;26:1351–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2021.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tian X., Wu Y., Yang Y., et al. Long noncoding RNA LINC00662 promotes M2 macrophage polarization and hepatocellular carcinoma progression via activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Mol Oncol. 2020;14(2):462–483. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pu J., Li W., Wang A., et al. Long non-coding RNA HOMER3-AS1 drives hepatocellular carcinoma progression via modulating the behaviors of both tumor cells and macrophages. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(12):1103. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-04309-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu Q., Yu X., Yang M., et al. A study of the mechanism of lncRNA-CR594175 in regulating proliferation and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vivo and in vitro. Infect Agents Cancer. 2020;15:55. doi: 10.1186/s13027-020-00321-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhong Z., Yu J., Virshup D.M., et al. Wnts and the hallmarks of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020;39(3):625–645. doi: 10.1007/s10555-020-09887-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yan X., Zhang D., Wu W., et al. Mesenchymal stem cells promote hepatocarcinogenesis via lncRNA-MUF interaction with ANXA2 and miR-34a. Cancer Res. 2017;77(23):6704–6716. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lin Y., Jian Z., Jin H., et al. Long non-coding RNA DLGAP1-AS1 facilitates tumorigenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma via the feedback loop of miR-26a/b-5p/IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 and Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(1):34. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2188-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li Y., Guo D., Zhao Y., et al. Long non-coding RNA SNHG5 promotes human hepatocellular carcinoma progression by regulating miR-26a-5p/GSK3β signal pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(9):888. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0882-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yao X., Liu C., Liu C., et al. lncRNA SNHG7 sponges miR-425 to promote proliferation, migration, and invasion of hepatic carcinoma cells via Wnt/β-catenin/EMT signalling pathway. Cell Biochem Funct. 2019;37(7):525–533. doi: 10.1002/cbf.3429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang W., Wu Y., Hou B., et al. A SOX9-AS1/miR-5590-3p/SOX9 positive feedback loop drives tumor growth and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Mol Oncol. 2019;13(10):2194–2210. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Qin M., Meng Y., Luo C., et al. lncRNA PRR34-AS1 promotes HCC development via modulating Wnt/β-catenin pathway by absorbing miR-296-5p and upregulating E2F2 and SOX12. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021;25:37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2021.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]