Abstract

Lymphodepleting pre-conditioning is a nearly universal component of T cell adoptive transfer protocols. The side effects of pre-conditioning regimens used in adoptive cell therapy are clinically significant and include pan-cytopenia, immune suppression, and reactive myelopoiesis. We conducted studies to test the hypothesis that the mechanisms underlying effective engraftment are cell autonomous and not dependent on a lymphodepleted host immune status. These studies leveraged mouse models to examine the role of Stat5 signaling during T cell adoptive transfer. We observed that, by transiently expressing a constitutively active mutamer of Stat5b during the process of adoptive transfer, we could completely obviate the need for lymphodepletion prior to adoptive transfer. Using several functional assays, we benchmark the function of the engrafted T cells against T cells transferred after conventional lymphodepletion. These studies identify a cell-autonomous mechanism driven by transient Stat5b signaling with lasting effects on T cell phenotype and function. Furthermore, the results presented suggest that adoptive T cell therapy could be improved by removing lymphodepletion protocols entirely and replacing them with RNA transfection of T cells with transcripts encoding active Stat5.

Keywords: adoptive transfer, tumor, T cell, Stat5, CRS, cytokine signaling, lymphodepletion, cell therapy, mRNA

Graphical abstract

O’Neil and colleagues demonstrate that T cell engraftment is cell autonomous and that transient activation of Stat5b signaling within the T cell product during infusion is sufficient to drive efficient engraftment, obviating the need for lymphodepletion.

Introduction

The success of adoptive cell therapy (ACT) using tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) or chimeric antigen receptor- (CAR) or T cell receptor (TCR)-engineered T cells relies on efficient engraftment of the cellular product. Historically, pre-conditioning regimens designed to lymphodeplete patients prior to infusion1,2 have been used to facilitate engraftment of adoptively transferred cells. Lymphodepleting regimens, such as chemotherapy and total body irradiation (TBI), work by eliminating endogenous cytokine-responsive cells that act as cytokine sinks.3 Further, lymphodepletion eradicates suppressive cell populations within the host immune system by eliminating immunosuppressive cell types, including regulatory T cells4,5 and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs).6 Patients who undergo lymphodepleting regimens prior to ACT exhibit increased survival and antitumor immunity.1,7 However, while these regimens are critical for maximizing clinical benefit, the agents used, like fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, are largely nonspecific agents with significant toxicity profiles.8,9

Lymphodepleting regimens can induce a variety of side effects, including leukopenia, pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, and reactive myelopoiesis.10 These side effects have contributed to patient exclusion and have hindered wider adoption of clinical trials leveraging engineered T cell-based therapeutics. In addition to the significant side effects, the physiological response to lymphodepletion can adversely affect the efficacy of ACT in qualifying patients.11 Moreover, management of these toxicities often necessitates long-term inpatient support and hospitalization, causing extreme financial burden on both patients and healthcare providers. Despite the fact that lymphodepletion regimens carry many drawbacks, it is clear that they promote functional engraftment and persistence of transferred T cells,12,13 while ACT without prior lymphodepletion results in poor engraftment of adoptively transferred T cells14 and reduces clinical benefit. This led us to explore cell-autonomous methods for promoting functional engraftment of engineered T cells that would obviate the need for lymphodepletion.

Functional engraftment is characterized by expansion and persistence of T lymphocytes and antitumor function. The specific mechanisms that contribute to effective engraftment are thought to be related to homeostatic T cell proliferation. The increased availability of homeostatic cytokines that occurs after lymphodepletion leads to an enhanced state of T cell proliferation thought to be regulated through γc cytokines, including interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-7, and IL-15. These cytokines play pivotal roles in regulating T cell homeostasis and inflammatory responses through critical signaling pathways. Current lymphodepleting regimens eliminate cellular cytokine sinks, thus increasing the availability of homeostatic cytokines to support the effectiveness of adoptively transferred T cells.3

Conventionally, the cytokines IL-2, IL-7, and IL-15 signal through the JAK-STAT pathway, primarily through the activation of JAK1/3 and STAT5, known mediators of T cell antitumor immunity.15,16 In response to cytokine stimulation, the C-terminal tyrosine (mY699, hY694) of Stat5b becomes phosphorylated, mediating Stat5b activation and dimerization, thus facilitating nuclear translocation and DNA binding.17,18 We chose to utilize a form of constitutively active Stat5b, which mimics structural aspects of phosphorylated Stat5b independently of tyrosine phosphorylation by substituting histidine 298 for arginine, referred to as Sta5b∗ in this article.16

In this study, we aimed to test our central hypothesis that transient Stat5b activation during the initial phase of adoptive transfer obviates the need for prior lymphodepletion. Herein, we describe that transient Stat5b activation during the initial phase of adoptive transfer leads to functional T cell engraftment and eliminates the spike in IL-6, a driving factor for cytokine release syndrome (CRS).19 We observe that Stat5b∗-expressing cells engrafted in lymphoreplete mice have superior recall response and improved tumor control in multiple immunocompetent tumor models. These results show that our novel engraftment strategy may represent an opportunity to remove lymphodepletion regimens from ACT protocols and, at the same time, improve the quality of the engrafted product.

Results

Stat5b∗ supports CD8+ T cell engraftment in the absence of lymphodepletion

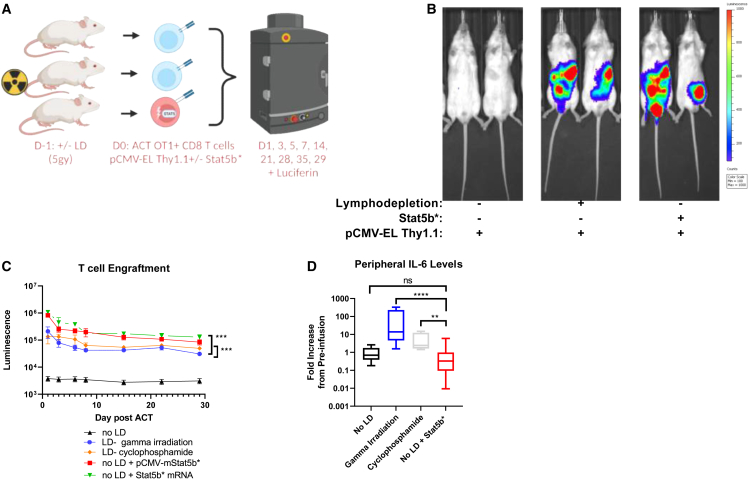

To evaluate the ability of T cells to engraft, we first modified murine OT-I T cells with a piggyBac transposon encoding enhanced firefly luciferase20 and a Thy1.1 marker driven by the CMV promoter (pT-effluc-thy1.1). Luciferase modification enabled us to track the T cells in vivo and quantify engraftment and persistence by measuring luciferase longitudinally. Using this model system, we transiently transfected a plasmid encoding a constitutively active version of murine Stat5b (pCMV-mStat5b∗) or Stat5b∗ mRNA into OT-I T lymphocytes prior to adoptive transfer (Figure 1A). We hypothesized that this novel engraftment strategy would activate pathways downstream of the γc cytokine receptors to facilitate T cell engraftment without prior lymphodepletion. We observed engraftment of adoptively transferred luciferase+ cells to lymphatic tissues in lymphodepleted recipients, as well as lymphoreplete animals transferred with T cells expressing constitutively active Stat5b∗ plasmid or mRNA (Figure 1B). This luciferase signal peaked at 24 h, followed by a luciferase signal decay over time, in accordance with the expected kinetics in a host without ovalbumin (OVA) antigen expression (Figure 1C). We evaluated aspects of the endogenous T cell compartment by flow cytometry after Stat5b∗-mediated adoptive transfer and noted a significant increase in CD4+ CD25+ T regulatory cells in the lymph nodes, but not the spleens, of mice transferred with T cells expressing constitutively active Stat5b∗ compared with mice treated after lymphodepletion (Figure S1A). The relevance of this observation is not clear but could be related to the effects of lymphodepleting radiation on CD25+CD4+ T cell compartment. We did not note any alterations in the CD4+ T helper cells (Figure S1B) or the CD8+ T cells (Figure S1C) that appeared to deviate from normal lymphodeleted mice after adoptive transfer. Importantly, we noted that cells transfected with pCMV-mStat5b∗ or Stat5b∗ mRNA engrafted more efficiently than the cells transferred into the lymphodepleted host. This suggests that Stat5b∗ expression during ACT could result in more efficient engraftment and could provide an opportunity to reduce the number of cells required to effectively treat patients.

Figure 1.

Transient expression of Stat5b∗ promotes CD8+ T cell engraftment in the absence of lymphodepletion

(A) Experimental schematic demonstrating three groups of animals that underwent adoptive cell transfer (ACT) using either conventional 5 Gy irradiation lymphodepletion (LD), no LD followed by ACT, or no LD followed by ACT with cells transfected with a plasmid encoding STAT5∗ immediately prior to ACT. (B) Representative ventral images of ffLuc-Thy1.1-engineered CD8+ T cells 3 days after ACT. (C) Animals were measured for 29 days post-ACT, and the intensity of the signal emitted by the ffLuc-Thy1.1+ T cells was expressed as luminescence. Quantification of total (dorsal + ventral) luminescence is plotted (n = 10 for LD, LD pCMV-mStat5b∗, and no LD; n = 5 for Stat5b∗ mRNA). (D) Peripheral IL-6 cytokine levels 24 h prior to ACT and 4 days post-ACT (n = 5 for no LD, gamma irradiation, and cyclophosphamide; n = 10 for no LD with Stat5b∗). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by unpaired Student’s t test (C and D). Error bars indicate the SEM.

Gene expression changes in mouse CD8+ T cells transfected with Stat5b∗

Based on the outcomes of the studies highlighted here, we propose that ACT could be improved by RNA transfection of a constitutively active Stat5 transcript prior to adoptive transfer. To evaluate this process, we leveraged Stat5b∗ plasmid DNA or mRNA to transfect OT-I+ CD8+ T cells and measured gene expression using the nanoString (Seattle, WA, USA) platform using the NS_MM_EXHAUSTION CSO code set. We first evaluated overall survival and transfection efficiency of T cells after RNA and DNA electroporation (Figure S2) and found that RNA transfection was associated with lower cellular toxicity (Figures S2A and S2B) and higher transfection efficiency (Figure S2C and S2D). We then harvested RNA from cells and analyzed them using an off-the-shelf nanoString Immune Exhaustion Panel (NS_MM_EXHAUSTION Panel: cat# PSTD-M-EXHAUST-12). The results of this analysis clearly indicate that, in CD8+ T cells, Stat5b∗ RNA transfection increases the expression of genes normally associated with Stat5b activation (Socs genes, Grzmb, Ccr5) while decreasing the expression of genes known to be downregulated by Stat5b activation (Il7r, Jak3, Ccr7) (Figure S3).21,22

Engrafting T cells without prior lymphodepletion eliminates pre-clinical correlates of CRS

One of the most frequent and serious adverse effects of T cell-based therapies is termed CRS. CRS has been linked to excessive production of IL-6 during T cell engraftment. This excessive IL-6 is not produced by the engrafting CAR-T cells but rather by recipient myeloid cells in response to the production of cytokines like IL-1β by the proliferating T cells and as a result of reactive myelopoiesis induced by lymphodepleting regimens.19 To investigate the differences in cytokine levels before and after ACT in the context of transient Stat5b∗, serum concentrations were assessed using a mouse cytokine proinflammatory focused 10-plex discovery assay (Eve Technologies, Calgary, AB, Canada) for mice of each treatment group. Consistent with previous observations regarding CRS and the cytokine levels noted above, the only cytokine whose levels increased after ACT was IL-6. Remarkably, this increase in serum IL-6 was not observed in mice that did not undergo lymphodepletion (Figure 1D). Furthermore, changes in other peripheral cytokine levels were not statistically significant (Figure S4). Taken together, this suggests that ACT of CAR-T cells without prior lymphodepletion may represent an opportunity to reduce or eliminate the risk of CRS in patients.

Adoptively transferred T cells maintain functional surveillance of OVA-expressing tumor cells long after engraftment

In addition to tracking the persistence of T cells in vivo, luciferase modification allowed us to evaluate their ability to respond to antigen challenge. To this end, as initial luminescence faded, we injected OVA-expressing Lewis Lung Carcinoma cells (LLC-OVAs) subcutaneously into the flank of each mouse (Figure 2A). We observed a rapid response of antigen-specific memory CD8+ T cells, indicated by the increase in bioluminescence at 24 h post-injection in both the lymphodepleted cohort and the lymphoreplete cohort engrafted with constitutively active Stat5b∗ plasmid or mRNA (Figures 2B and 2C).

Figure 2.

Stat5b∗ drives superior recall response in the absence of LD

(A) Experimental schema for (B and C). (B) Representative images of ffLuc-Thy1.1-engineered CD8+ T cells 40 days post-ACT and 24 h after rechallenging with LLC-OVA cells. (C) Animals were measured 24 and 72 h following LLC-OVA challenge, and the intensity of the signal emitted by the ffLuc-Thy1.1-transfected T cells was expressed as luminescence. (D) Tumor growth kinetics and (E) survival of mice challenged with LLC-OVA. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by unpaired Student’s t test (C), linear regression of tumor growth (D), and log-rank, Mantel-Cox test of survival proportions (E). Error bars indicate the SEM.

To further evaluate the functional fitness of T cells engrafted using transient Stat5b∗, we next evaluated the effector function of the engrafted antigen-specific T cells. As expected, the engrafted T cells provided significant tumor control in the lymphodepleted group, although this group resulted in a lesser antitumor effect than that of the Stat5b∗ plasmid or mRNA counterparts. Strikingly, many of the mice engrafted with ACT using Stat5b∗ (without lymphodepletion) experienced complete tumor control and significantly enhanced overall survival in host mice (Figures 2D and 2E). This result implies that this engraftment method yields functionally superior T cells prompting us to investigate the phenotype of cells generated by the respective modes of engraftment.

Stat5b∗ promotes development of a noncanonical effector memory cell phenotype

We examined the phenotype of cells that had undergone adoptive transfer under each condition by collecting cells from spleens of mice 3 days after engraftment (Figure 3A). Interestingly, we observed that cells engrafted using the transient Stat5b∗ protocol failed to upregulate CD62L after adoptive transfer, in contrast to what we observed using conventional lymphodepletion regimens (Figures 3B and 3C). To further investigate if lymphodepletion or Stat5b∗ had a dominant effect on suppressing CD62L expression, we conducted a competition assay where mice were lymphodepleted and then engrafted with Stat5b∗-transfected Thy1.1+ cells at a 1:1 ratio with pCMV-GFP-transfected cells (Figure 3D). Comparison of CD62L expression between the Stat5b∗+ and Stat5b∗− cells further supported a model where Stat5b∗ drives dominant alterations in cell phenotype, as defined by CD62L (Figures 3E and 3F). Historically, CD62L expression has been used to differentiate effector memory (CD62Llow) from central memory (CD62Lhigh) T cells. However, more recent evidence challenges the utility of this model and suggests that there are long-lived effector memory cells that remain CD62Llow after adoptive transfer.23

Figure 3.

CD62L expression is reduced by transient expression of Stat5b∗

(A) Experimental workflow: mice received unmodified cells after conventional LD or cells with transient expression of Stat5b∗ with no LD. (B and C) Representative contour plots and summary data of flow cytometry analysis of CD62L and CD44 expression. (D) Schematic diagram of a competition study exploring the role of LD vs. Stat5b∗ on T cell phenotype. (E and F) Representative contour plots and summary data comparing the phenotype of GFP+ and Thy1.1+ (Stat5∗-transfected) cells from the same spleens that were all lymphodepleted prior to ACT. Error bars represent SEM. ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

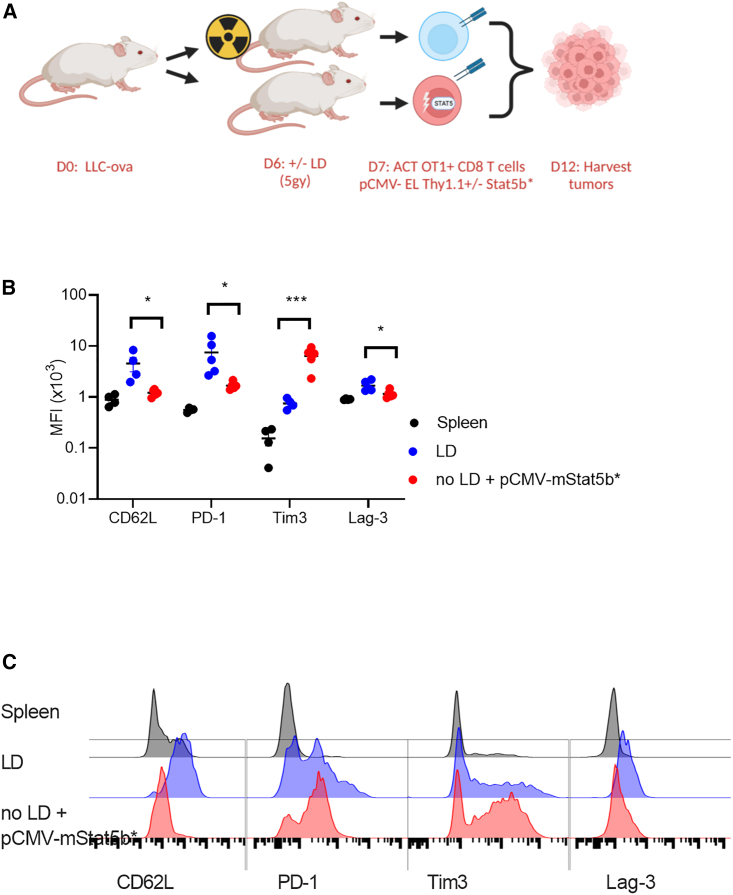

Transient expression of Stat5b∗ during engraftment alters T cell phenotype in solid tumors

To determine if antitumor function would be altered in Stat5b∗ T cell-engrafted mice, we conducted studies to examine the phenotype of adoptively transferred T cells within an immunosuppressive tumor model. Cells were adoptively transferred using conventional lymphodepletion or by transiently expressing Stat5b∗ during engraftment. Tumors were harvested 6 days after ACT, and cell phenotype was characterized by flow cytometry (Figure 4A). Similar to the findings observed in Figure 3, we continued to observe a CD62Llow phenotype in our cells engrafted with Stat5b∗ as compared with cells engrafted after conventional lymphodepletion. Further, we observed a unique cell phenotype in the Stat5b∗-modification group where the T cells displayed a significant reduction in PD1 expression compared with cells engrafted using conventional lymphodepletion (Figure 3B). Consistent with previous observations,24 Tim3 expression increased as a result of transient Stat5b∗ expression compared to tumor-infiltrating cells engrafted using conventional lymphodepletion. Tim3 has often been identified as a marker of exhaustion when combined with PD1 and Lag3 expression25; however, we see independent regulation of the three genes in response to Stat5b∗ (Figures 4B and 4C).

Figure 4.

ACT without LD using transient Stat5∗ results a unique phenotype of tumor-infiltrating T cell

(A) Schematic diagram of experiments: subcutaneous tumors were initiated prior to ACT. Tumors were harvested 6 days after adoptive transfer, and the phenotype of engrafted cells was assessed by flow cytometry for markers associated with T cell exhaustion. (B) CD62L, PD1 levels, Tim3 levels, and Lag-3 levels expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), and (C) representative histograms of flow cytometry analysis of the aforementioned surface markers on the adoptively transferred T cells after recovery. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Transient expression of Stat5b∗ during engraftment promotes control of established tumors

We next sought to assess the functional consequences of Stat5b∗ activation on tumor control in lymphoreplete hosts, as depicted in Figure 5A. Control luciferase-labeled T cells or Stat5b∗ luciferase-labeled T cells were infused into LLC-OVA (Figures 5B and 5C) or B16-F10 (Figures 5D and 5E) tumor-bearing mice. Strikingly, Stat5b∗ T cells exhibited potent and durable tumor control that posed a similar effect to that of T cell counterparts engrafted through standard lymphodepletion regimens (Figures 5B and 5D). As expected, treating lymphoreplete hosts with control T cells abrogated tumor control and diminished survival in both tumor models, supporting the previously described role for lymphodepletion in sustaining antitumor immunity of adoptively transferred T cells.1,2 In line with these data, survival was substantially enhanced in lymphodepleted mice infused with antigen-specific T cells and in lymphoreplete hosts with Stat5b∗-conditioned T cells compared with the respective control T cells in lymphoreplete hosts (Figures 5C and 5E). Taken together, these data demonstrate that Stat5b∗ is crucial for T cell-mediated tumor control in lymphoreplete hosts.

Figure 5.

Adoptive transfer using transient Stat5b∗ without LD leads to functional control of tumors

(A) Experimental schema for (B–E). (B) Tumor growth kinetics and (C) survival of mice bearing LLC-OVA tumors infused with OT-I− T cells engrafted via conventional LD (blue) or Stat5b∗ (red) (n = 5 mice per group). (D) Tumor growth kinetics and (E) survival of mice bearing B16-F10 tumors infused with PMEL− T cells engrafted via conventional LD (blue) or Stat5b∗ (red) (n = 5 mice per group). Linear regression analysis of tumor growth and log-rank, Mantel-Cox test of survival proportions were used (C and E). Error bars indicate the SEM. ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

Discussion

Lymphodepleting regimens used in ACT protocols condition the host for optimal engraftment and persistence of the adoptively transferred cells. Various mechanistic explanations for this phenomenon have been suggested, including liberation of physical space and of homeostatic cytokines, induction of homeostatic cytokine production, and elimination of suppressive cell types.3,4,5,6 Our central hypothesis in this study is that liberated homeostatic cytokines drive activation of Stat5b when engrafting T cells into a lymphodepleted host, which promotes engraftment and survival of the adaptively transferred cells. Furthermore, we hypothesize that engraftment could be promoted in a cell-autonomous manner and that transient activation of Stat5b signaling during adoptive transfer was sufficient to promote engraftment.

We observe that transient expression of Stat5b∗ via plasmid or RNA transfection strongly promotes engraftment of adoptively transferred T cells. The concept that transient modification of Stat5 signaling is sufficient to modify the function and phenotype of adoptively transferred T cells is unique in the context of previous studies leveraging stable modification of T cells with activated signaling molecules.26 By using T cells adoptively transferred using conventional lymphodepletion as a benchmark, we make comparisons about the magnitude, phenotype, and function in the context of transient Stat5b∗ expression. On a per-cell basis, transient Stat5∗ expression appears to improve ACT, suggesting that this approach could be deployed to lower cell dose requirements and reduce manufacturing time of cell therapies. Differences in the phenotypes of cells engrafted using the Stat5b∗ approach were observed in the spleens of nontumor-challenged mice and in T cells obtained from tumors several days after ACT. The lack of CD62L upregulation and the superior control of delayed tumor challenge (40 days after initial ACT; Figure 2) supports a model where a long-lived effector memory-like phenotype is generated by transient Stat5b∗ expression.23 CD62L is considered to be critically involved in the trafficking of naive T cells to the lymphatics. The relevance of CD62L for homing in inactivated T cells is less clear, as supported by the clear presence of CD62Llow cells within the spleen in our in vivo models of adoptive transfer. The reduction in PD1 and Lag3 expression in the tumor-associated T cells engrafted using transient Stat5∗ suggests that this engraftment protocol could produce T cells that are less likely to be exhausted within a tumor. Tim3 upregulation was observed in the tumor model when cells underwent Stat5b∗ transfection. The Tim3 gene is thought to be directly regulated by several Stat transcription factors,27 so increased Tim3 expression could be a direct or an indirect effect of Stat5b∗ activity.

In addition to depleting lymphocytes, conventional regimens of lymphodepletion result in mild myelosuppression, which is followed by a recovery phase termed “reactive myelopoiesis.”11 During this recovery phase, immature hematopoietic progenitor cells can differentiate into highly immunosuppressive myeloid-derived cells. These cells are highly reactive to cytokines like IL-1β and produce large amounts of IL-6 during T cell adoptive transfer, a contributing factor in CRS. Using cell-autonomous approaches, such as transient Stat5b∗ modification described in the current study, may reduce CRS. Furthermore, reactive myelopoiesis caused by lymphodepletion could contribute to direct inhibition of the infused T cell product. Indeed, clinical data indicate that IL-6 levels after ACT not only directly correlate with CRS but that they also predict therapeutic response.28

As a whole, these studies strongly support the initiation of clinical trials exploring the utility of transient Stat5b∗ to augment adoptive transfer and potentially replace lymphodepletion. If successful, this strategy could lead to improved outcomes for patients, allow for more frequent redosing as needed, reduce cell dose and time to treat, and play an important role in expanding the application of engineered T cells to different therapeutic indications beyond hematologic malignancies.

Materials and methods

Molecular biology

Transfection-grade plasmids were prepared according to the manufacturers protocol using endotoxin-free buffers and ZymoPURE II Plasmid Maxiprep Kits (ZYMO Research, Irvine, CA, USA) The plasmid vectors pT-effluc-thy1.120 and pRP--CAG>hyPBase,29 pTPB-CMV-GFP, pCMV-mStat5b∗, pT7-mStat5b∗, and pT7-hStat5b∗ were synthesized by Vector Builder Biosciences (Chicago, IL, USA). All plasmid vectors were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Transfection-grade plasmids were prepared according to the manufacturer’s protocol using endotoxin-free buffers and ZymoPURE II Plasmid Maxiprep Kits (ZYMO Research).

Mice

OT-I (C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/J), PMEL (B6.Cg-Thy1a/Cy Tg(TcraTcrb)8Rest/J), and B6 albino (B6(Cg)-Tyrc−2J/J) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. Luciferase (β-actin-luc) was obtained from Taconic Bioscience. All animal experiments were approved by the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC-2021-01329), and the Division of Laboratory Animal Resources at MUSC maintained all mice.

Cell culture

B16-F10 and LLC-OVA tumor lines, as well as HEK293T cells, were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS. All cell lines were determined to be mycoplasma free in December 2021. OT-I T cells, human CD4+ T cells, and human CD8+ T cells were maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS, 300 mg/L L-glutamine, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 μM NEAA, 1 mM HEPES, and 55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol. For OT-I and PMEL T cell activation and expansion, whole splenocytes from OT-I or PMEL mice were activated with 1 μg/mL OVA 257–264 peptide or 1 μg/mL glycoprotein 100 (gp100). For Luc+ T cell isolation, CD8+ lymphocytes were purified from the spleen using the MACS mouse CD8a+ T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA). Purified CD8+ lymphocytes were then activated with anti-CD3e 2.5 μg/mL (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA) and anti-CD28 2 μg/mL (BD Bioscience). All T cells were expanded for 3 days with 200 U/mL rhIL-2 (NCI). T cells were split on day 3 and expanded in rhIL-2 or IL-15 (50 ng/mL) through day 7.

In vitro transcription

mRNA was transcribed using the mMessage mMachine T7 ULTRA Transcription Kit (Ambion, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). The protocol provided by the manufacturer was used. The mRNA was resuspended in nuclease-free water and stored at −80°C prior to transfection.

Adoptive transfer models

After in vitro expansion, lymphocytes cells were washed briefly in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by centrifugation and transfected with the Neon (Life Technologies) transfection system according to the manufacturer’s instructions for mouse T cells. In-vitro-expanded OT-I T cells were prepared for adoptive transfer by transfection with 5 μg pRP--CAG>hyPBase and 10 μg pCMV-EL-Thy1.1 or 10 μg pT-GFP and 10 μg pCMV-mStat5b∗. For mRNA transfections, OT-I T cells were transfected with the indicated concentrations of GFP mRNA or with 20 μg Stat5b∗ mRNA using the previously described settings.30 Transfected T cells were rested in complete T cell medium for 1 h before resuspending cells in PBS and directly transferring the cells into recipient mice. Luc+ T cells were transfected with 20 μg Stat5b∗ mRNA. Prior to adoptive transfer, mice were pre-conditioned by exposure to 5 Gy lymphodepleting radiation using a cesium irradiator or using cyclophosphamide (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) dissolved in PBS administered by intraperitoneal injection at a dose of 200 mg/kg unless otherwise indicated. T cells were transfected as described above, allowed to recover in complete T cell medium (TCM) for 1 h and then adoptively transferred via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. For ex vivo analysis of ELThy1.1 or GFP transferred T cells, mice were sacrificed 3 days after transfer, and organs were processed to single-cell suspensions for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis.

Tumor cell challenge

For primary challenges, mice were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) with 2.5 × 105 LLC-OVA tumor cells on day 40 after initial adoptive transfer of OT-I+ T cells.

Tumor models

For adoptive cellular therapy experiments, LLC-OVA adenocarcinomas or B16-F10 melanomas were established s.c. by injecting 2.5 × 105 cells into the right flank of male B6(Cg)-Tyrc−2J/J mice, and tumor-bearing hosts were irradiated with 5 Gy 24 h prior to T cell transfer. After 7 days of tumor growth, 1 × 107 OT-I or PMEL T cells were transfected using the Neon transfection system prior to infusion in 100 μL PBS via i.p. injection into mice. Tumor growth was measured every other day with calipers, and survival was monitored with an experimental endpoint of tumor growth ≥400 mm2. For ex vivo analysis of ff-Luc-Thy1.1 transferred T cells, mice were sacrificed 5 days after transfer, and organs were processed to single-cell suspensions for FACS analysis.

Bioluminescent imaging

Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane and injected i.p. with luciferin substrate (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) at a standard concentration of 150 mg/kg in PBS. Approximately 10 min after luciferase injections, mice were imaged on the AMI-HT (Spectral Imaging, Tucson, AZ, USA). All data shown represent mean luminescence observed by summing dorsal and ventral measurements obtained from identical regions of interest drawn over the trunk and head of each individual mouse.

Assessment of serum cytokines

Blood was collected in Microvette CD300 Potassium EDTA collection tubes (Sarstedt, Newton, NC, USA) by retroorbital vein bleeding. Serum was measured using the Mouse Cytokine Pro-inflammatory Focused 10-Plex Discovery Assay (MDF10) (Eve Biotechnologies).

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained with Live/Dead Fixable Aqua dead stain cell kit (Invitrogen) prior to extracellular staining. Fluorescent dye-conjugated antibodies were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA, USA), eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA), or BD Pharmigen (Mountain View, CA, USA). Cells were stained extracellularly with CD90.1 (HIS51)-PE, CD8a (53–6.7)-PerCP-eFluor 710, CD44 (IM7)-PECy7, CD62L (MEL-14)-BV421, PD-1 (29F.1A12)-APC, Tim-3 (RMT3-23)-FITC, Lag-3 (C9B7W)-APC-eFluor 780, CD3 (145-2C11)-FITC, (GK1.5)-APC-eFluor 780, and CD25 (PC61.5)-PECy7 or isotype control, and subsequently, cell surface antibody staining was done in PBS containing 2% FBS. Antibody-stained cells were run directly on a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter Life Sciences, Indianapolis, IN, USA), and analysis was performed with FlowJo software.

Nanostring gene expression analysis

RNA isolation

Cells were immediately pelleted by centrifugation at 4°C and resuspended in homogenization buffer containing thioglycerol provided in the purification kit. RNA was extracted with a Promega Maxwell RSC 16 using the Maxwell RSC simplyRNA Cells kit (cat# AS1390) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and RNA concentration was measured using a NanoDrop 8000.

Gene quantitation

Direct quantitation of selected transcripts was performed using 100 ng total RNA on a Nanostring nCounter system using markers within the NS_MM_EXHAUSTION code set. RCC files were imported into nSolver 4.0 software and analyzed using the default analysis pipeline for normalization, differential expression, and agglomerative clustering.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism was used to calculate p values with one-way analysis of variation (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, unpaired Student’s t test, or paired Student’s t test as indicated in the figure legends. Tumor growth curves were analyzed by simple linear regression. Values of p <0.05 were considered significant. p <0.05 values were ranked as ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the MUSC Translation Research Laboratory, a university-supported shared research resource supported by the Hollings Cancer Center Support grant (P30 CA138313), and grants IK2BX004585-01A1 (R.T.O.) and T32 DE01755 (M.D.T.). Schematics were created with BioRender.com.

Author contributions

M.D.T. and R.T.O. conceived, designed, and executed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. C.N. and L.M.R.F. conducted experiments and assisted with data analysis.

Declaration of interests

A provisional patent based on results from this work has been filed by M.D.T. and R.T.O.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.07.015.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

All original data are available from the authors without any restrictions.

References

- 1.Lee D.W., III, Stetler-Stevenson M., Yuan C.M., Shah N.N., Delbrook C., Yates B., Zhang H., Zhang L., Kochenderfer J.N., Rosenberg S.A., et al. Long-Term Outcomes Following CD19 CAR T Cell Therapy for B-ALL Are Superior in Patients Receiving a Fludarabine/Cyclophosphamide Preparative Regimen and Post-CAR Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Blood. 2016;128:218. doi: 10.1182/blood.V128.22.218.218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turtle C.J., Hanafi L.A., Berger C., Hudecek M., Pender B., Robinson E., Hawkins R., Chaney C., Cherian S., Chen X., et al. Immunotherapy of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma with a defined ratio of CD8+ and CD4+ CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016;8:355ra116. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf8621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gattinoni L., Finkelstein S.E., Klebanoff C.A., Antony P.A., Palmer D.C., Spiess P.J., Hwang L.N., Yu Z., Wrzesinski C., Heimann D.M., et al. Removal of homeostatic cytokine sinks by lymphodepletion enhances the efficacy of adoptively transferred tumor-specific CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:907–912. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antony P.A., Restifo N.P. CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells, immunotherapy of cancer, and interleukin-2. J. Immunother. 2005;28:120–128. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000155049.26787.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antony P.A., Piccirillo C.A., Akpinarli A., Finkelstein S.E., Speiss P.J., Surman D.R., Palmer D.C., Chan C.C., Klebanoff C.A., Overwijk W.W., et al. CD8+ T cell immunity against a tumor/self-antigen is augmented by CD4+ T helper cells and hindered by naturally occurring T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 2005;174:2591–2601. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bronte V., Apolloni E., Cabrelle A., Ronca R., Serafini P., Zamboni P., Restifo N.P., Zanovello P. Identification of a CD11b(+)/Gr-1(+)/CD31(+) myeloid progenitor capable of activating or suppressing CD8(+) T cells. Blood. 2000;96:3838–3846. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dudley M.E., Yang J.C., Sherry R., Hughes M.S., Royal R., Kammula U., Robbins P.F., Huang J., Citrin D.E., Leitman S.F., et al. Adoptive cell therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: evaluation of intensive myeloablative chemoradiation preparative regimens. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:5233–5239. doi: 10.1200/jco.2008.16.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muranski P., Boni A., Wrzesinski C., Citrin D.E., Rosenberg S.A., Childs R., Restifo N.P. Increased intensity lymphodepletion and adoptive immunotherapy--how far can we go? Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2006;3:668–681. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen C.I., Abraham R., Tsang R., Crump M., Keating A., Stewart A.K. Radiation-associated pneumonitis following autologous stem cell transplantation: predictive factors, disease characteristics and treatment outcomes. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2001;27:177–182. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bechman N., Maher J. Lymphodepletion strategies to potentiate adoptive T-cell immunotherapy - what are we doing; where are we going? Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2021;21:627–637. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2021.1857361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Innamarato P., Kodumudi K., Asby S., Schachner B., Hall M., Mackay A., Wiener D., Beatty M., Nagle L., Creelan B.C., et al. Reactive Myelopoiesis Triggered by Lymphodepleting Chemotherapy Limits the Efficacy of Adoptive T Cell Therapy. Mol. Ther. 2020;28:2252–2270. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dudley M.E., Wunderlich J.R., Yang J.C., Hwu P., Schwartzentruber D.J., Topalian S.L., Sherry R.M., Marincola F.M., Leitman S.F., Seipp C.A., et al. A phase I study of nonmyeloablative chemotherapy and adoptive transfer of autologous tumor antigen-specific T lymphocytes in patients with metastatic melanoma. J. Immunother. 2002;25:243–251. doi: 10.1097/01.Cji.0000016820.36510.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dudley M.E., Wunderlich J.R., Robbins P.F., Yang J.C., Hwu P., Schwartzentruber D.J., Topalian S.L., Sherry R., Restifo N.P., Hubicki A.M., et al. Cancer Regression and Autoimmunity in Patients After Clonal Repopulation with Antitumor Lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298:850–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1076514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramos C.A., Rouce R., Robertson C.S., Reyna A., Narala N., Vyas G., Mehta B., Zhang H., Dakhova O., Carrum G., et al. In Vivo Fate and Activity of Second- versus Third-Generation CD19-Specific CAR-T Cells in B Cell Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphomas. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:2727–2737. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rochman Y., Spolski R., Leonard W.J. New insights into the regulation of T cells by gamma(c) family cytokines. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:480–490. doi: 10.1038/nri2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grange M., Buferne M., Verdeil G., Leserman L., Schmitt-Verhulst A.-M., Auphan-Anezin N. Activated STAT5 Promotes Long-Lived Cytotoxic CD8+ T Cells That Induce Regression of Autochthonous Melanoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:76–87. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-11-2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gouilleux F., Wakao H., Mundt M., Groner B. Prolactin induces phosphorylation of Tyr694 of Stat5 (MGF), a prerequisite for DNA binding and induction of transcription. EMBO J. 1994;13:4361–4369. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06756.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Onishi M., Nosaka T., Misawa K., Mui A.L., Gorman D., McMahon M., Miyajima A., Kitamura T. Identification and characterization of a constitutively active STAT5 mutant that promotes cell proliferation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:3871–3879. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris E.C., Neelapu S.S., Giavridis T., Sadelain M. Cytokine release syndrome and associated neurotoxicity in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022;22:85–96. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00547-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabinovich B.A., Ye Y., Etto T., Chen J.Q., Levitsky H.I., Overwijk W.W., Cooper L.J.N., Gelovani J., Hwu P. Visualizing fewer than 10 mouse T cells with an enhanced firefly luciferase in immunocompetent mouse models of cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:14342–14346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804105105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bitar M., Boldt A., Freitag M.-T., Gruhn B., Köhl U., Sack U. Evaluating STAT5 Phosphorylation as a Mean to Assess T Cell Proliferation. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:722. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tripathi P., Kurtulus S., Wojciechowski S., Sholl A., Hoebe K., Morris S.C., Finkelman F.D., Grimes H.L., Hildeman D.A. STAT5 is critical to maintain effector CD8+ T cell responses. J. Immunol. 2010;185:2116–2124. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Renkema K.R., Huggins M.A., Borges da Silva H., Knutson T.P., Henzler C.M., Hamilton S.E. KLRG1(+) Memory CD8 T Cells Combine Properties of Short-Lived Effectors and Long-Lived Memory. J. Immunol. 2020;205:1059–1069. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1901512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mo F., Yu Z., Li P., Oh J., Spolski R., Zhao L., Glassman C.R., Yamamoto T.N., Chen Y., Golebiowski F.M., et al. An engineered IL-2 partial agonist promotes CD8(+) T cell stemness. Nature. 2021;597:544–548. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03861-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wherry E.J., Kurachi M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015;15:486–499. doi: 10.1038/nri3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shum T., Omer B., Tashiro H., Kruse R.L., Wagner D.L., Parikh K., Yi Z., Sauer T., Liu D., Parihar R., et al. Constitutive Signaling from an Engineered IL7 Receptor Promotes Durable Tumor Elimination by Tumor-Redirected T Cells. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:1238–1247. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones R.B., Ndhlovu L.C., Barbour J.D., Sheth P.M., Jha A.R., Long B.R., Wong J.C., Satkunarajah M., Schweneker M., Chapman J.M., et al. Tim-3 expression defines a novel population of dysfunctional T cells with highly elevated frequencies in progressive HIV-1 infection. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:2763–2779. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Locke F.L., Rossi J.M., Neelapu S.S., Jacobson C.A., Miklos D.B., Ghobadi A., Oluwole O.O., Reagan P.M., Lekakis L.J., Lin Y., et al. Tumor burden, inflammation, and product attributes determine outcomes of axicabtagene ciloleucel in large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2020;4:4898–4911. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yusa K., Zhou L., Li M.A., Bradley A., Craig N.L. A hyperactive piggyBac transposase for mammalian applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:1531–1536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008322108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aksoy P., Aksoy B.A., Czech E., Hammerbacher J. Viable and efficient electroporation-based genetic manipulation of unstimulated human T cells. bioRxiv. 2019 doi: 10.1101/466243. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All original data are available from the authors without any restrictions.