Abstract

A potentially beneficial method in laser irradiation is currently gaining popularity. The biosynthesis of low-power lasers has also been applied to the therapy of disease in biological tissues. This study used laser pre-treatments of Silybum marianum (S. marianum) fruit extract as a stabilising agent to bio-fabricate a low-power laser. The silybin A and silybin B of the S. marianum fruit, which are derived from seedlings before S. marianum undergoes therapy with an He-Ne laser at various intervals, were assessed for their expressive properties in this study. The findings revealed that 6-min laser pre-treatments increased silybin A + B and bacterial inhibition and improved the medicinal property of S. marianum. The analysis of the reaction records was performed using ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) limit for the sphere dispersion approach’s antimicrobial effect on the microorganisms under investigation was 50 to 100 g/mL. With an IC50 of 0.69 mg/mL, the laser-treated S. marianum (6 min) demonstrated radical scavenging activity. At MIC concentration, the laser-treated S. marianum (6 min) did not exhibit cytotoxicity in the MCF-7 cell line. Additionally, Salmonella typhi, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and E. coli were more susceptible to the antimicrobial effects of ethanolic fruit extract with a greater silybin level. It was observed that the laser-treated S. marianum (6 min) showed beneficial antioxidant and antibacterial properties and could be employed without risk in several medical applications.

Keywords: Silybin, He-Ne laser, Antibacterial, Disc diffusion assay

1. Introduction

Silybum marianum L. Gaertn (S. marianum), sometimes known as milk thistle, is a yearly or evergreen medicinal herb that is primarily found in the Middle East and Mediterranean Sea regions. These fruits and seeds produce chemically bioactive compounds that are crucial in medicinal and pharmacological applications (Fierascu et al., 2020, Karasawa and Mohan, 2018). A mixture of stereoisomeric flavonolignans, silymarin, which is derived from S. marianum fruits, is used to treat a number of liver disorders. It is the most notable secondary metabolite of S. marianum (El-Garhy et al., 2016, Yap et al., 2021). Natural silybin combines silybin A and silybin B and is a crucial component of silymarin. It also provides silymarin with the most hepatoprotective effects (Bhilegaonkar and Kolhe, 2023, Guerrini and Tedesco, 2023, Yap et al., 2021). Since ancient times, the derived compound of the S. marianum fruit has been regarded as a ‘liver tonic’ and it plays a significant role in the prevention or treatment of toxicity of reactive drug by-products or naturally present toxic materials in the liver (Mariappan et al., 2023). Silymarin and phenolic acids comprise most of the milk thistle’s active ingredients (Behl et al., 2020, Yao et al., 2020). The flavonolignans silybin A and B, isosilybin A and B, silydianin, and silychristin, as well as the flavonoids taxifolin and quercetin, make up the actual product known as silymarin, which is the plant’s medicinal component. Polymeric and oxidised polyphenolic compounds constitute the rest, between 20 and 40 percent of the concentrate (Hurtová et al., 2022).

There has been interest in using lasers in agriculture for some time (Wu et al., 2023). However, this technology has recently experienced a true revival; according to studies have shown that it is the only effective way to produce wholesome, better quality food (Ali et al., 2020). Pre-sown seed is exposed to laser light to germinate better and more quickly in various, frequently unfavourable, habitat circumstances (Klimek-Kopyra & Czech, 2022).

Typhoid fever is caused by Salmonella typhi (S. typhi), an acute systemic illness prevalent in underdeveloped nations and associated with low socioeconomic status and unsanitary environments (Maślak et al., 2023). Sole humans are asymptomatic carriers and the only natural reservoirs (Bhilegaonkar & Kolhe, 2023). Ingestion of tainted food or water typically results in transmission via the faecal-oral route (Bhilegaonkar & Kolhe, 2023). Pyogenic liver abscesses (PLA) covering hepatic melanoma metastases exacerbate typhoid fever (Dey & Ray Chaudhuri, 2022).

At a dose of 226 g/plate, the S. marianum extract considerably lowered (by 35.8%) the speed of opposite modifications that were brought on by its action on NPD (Gad et al., 2020). Among the silymarin compounds, silybin A and B are thought to be the physiologically active components (Foghis et al., 2023).

This research has been undertaken to assess the impacts of silybin A and silybin B extract from S. marianum fruit which pre-treatment He-Ne laser and from a control group and to determine how S. typhi affects human liver function when treated with S. marianum extract and laser radiation.

2. Materials and methodology

2.1. Disc diffusion assay to verify the antimicrobial property of fruit product derived from S. marianum methanolic extract

2.1.1. Production of S. marianum test compounds with the help of fruit extract derived from S. marianum

Three different plants were acquired to obtain methanolic extracts from each treatment group, including the control and low-power laser groups. Both of these were dissolved separately in a solution of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and water, with a ratio of 1:1 by weight. This process generated substances for S. marianum screening solutions with 5 mg of extract/mL for the disc diffusion technique. A total of nine products (three from control plants, three from low-power laser-treated plants, and three from laser-treated plants) were stored at 4 °C until needed.

2.1.2. Disc diffusion assay

S. typhi, E. coli ATCC 8739, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacterial strains were acquired from King Faisal University’s College of Medicine. The disc diffusion assay was carried out in accordance with Aldayel et al., 2021, Aldayel et al., 2022, and Rana et al. (2023) and nutrient broth was used for the cultivation of all microbial strains (Sigma Aldrich, Cat. no. 7014). 100 µL of an overnight bacterial culture was obtained and mixed with the 10 mL of nutrient broth as an inoculum, and the cultures were cultivated at 37 °C at 200 rpm until their turbidity reached 0.3 at 600 nm. Bacterial cultures (5 mL) of each bacterial strain were obtained and placed in plates full of nutritional agar to ensure that the medium was divided and placed equally. Each bacterial strain was placed onto nine agar plates. Before the test solution discs were applied to the agar, all infected plates were placed in a biosafety cabinet uncapped to allow any extra liquid to sink into the agar. On each inoculation plate’s agar surface, five 6 mm diameter plates were wetted with different test solutions. Discs used as the positive control contained a DMSO:water solution at a ratio of 1:1, while S. marianum screening compounds made from methanolic fruit products of the control and low-power laser-altered plants were placed on the other two discs. The disc used as the positive control contained 10 µg imipenem (cat. no. 7052) and was bought from Condalab in Madrid, Spain. The diameters of all plates were analysed and confirmed after an overnight incubation of the inhibited zone and measured at 37 °C.

2.2. Determination of antioxidant activity

A DPPH radical removal assay was employed to measure the low-power laser’s protective and antioxidant effects (Aldayel, 2023). At 517 nm, the decrease of DPPH was measured spectrophotometrically, with gallic acid serving as the standard. Evaluations were made on the IC50 and % activity (Ameen et al., 2021).

Ac is the absorbance of the control.

As is the absorbance of the low-power laser mixture.

2.3. Cytotoxicity study

With the aid of an MTT cell proliferation test kit, the cytotoxicity of the low-power laser was determined by gauging cell viability. For 48 h, cells were placed in plates and exposed to different quantities of the low-power laser. PBS was used to wash the cells, which were then incubated in a fresh medium with MTT. An ELISA plate reader was used to measure optical density, which was 550 nm (Aldayel, 2023).

2.4. Data analysis

ANOVA and MANOVA procedures were carried out to evaluate the data using Statistica software for data analysis, 6th edition (StatSoft Inc.). The Lowest Significant Analysis (LSD) test was applied to test the reliability of average variance at p = 0.05 (Suppakul et al., 2003).

2.5. Investigation of the silybin (A + B) composition by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

2.5.1. Procedure

An individual treatment group with three biological replicates provided air-dried fruit samples. To assess the quantity of silybin (A + B), the samples were analysed with Waters 2690 Alliance HPLC equipment (USA) coupled with a Waters 996 photoelectric matrix reader.

2.5.2. Preparation of the stock solution

The genuine silybin (A + B) benchmark that was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. in the USA (catalogue no. sc-473918) was used to generate the silybin (A + B) stock solution that was 1 mg/mL in methanol. Five serial dilutions totalling 750 g/mL, 500 g/mL, 250 g/mL, 100 g/mL, and 50 g/mL were produced. After purifying each diminished solution with a 0.22 mL injection filtering process, 10 L of every compound was individually added to the HPLC setup.

2.5.3. Manufacturing the fruit product of Silybum

After the weight of each air-dried fruit was measured, a conical flask was used to place the fruit, to which 50 cc of methanol was then added. Sonication of the samples was performed for 30 min and then they were exposed to darkness for 24 h. The suspension was then filtered, and the filtrate was collected and set aside. The resulting filtrate leftover was combined using 50 cc of newly generated methanol, and the removal operation was performed on three separate occasions. The dry residue of the individual sample was obtained from a rotary evaporator at 40 °C. When the actual weight of the dried residue was mixed in the ethanol (5 mL), a 0.22 m filter was used to purify the individual sample.

2.5.4. Investigation parameters for HPLC

HPLC was carried out at ambient temperature employing a C18 Kromasil phase (4.6 × 150 mm, 5 m). Two solvents, Solvent A and Solvent B, were used to achieve differential elimination; each solvent was composed of methanol, water, and phosphoric acid in proportions of 80:20:0.5 by weight. The mobile phase’s speed of flow remained 1 mL/min and was sustained at the same level, and the eluate was picked up at a wavelength of 288 nm (Table1).

Table 1.

HPLC quantification analysis of silybin (A + B) content as milligram (mg) per 100 g of fruit dried weight (D.W.).

| Laser treatments (min) | Silybin (A + B) mg/100 g D.W. |

|---|---|

| Control | 48.98 ab |

| 2 min | 30.55 b |

| 4 min | 42.81 ab |

| 6 min | 58.66 a |

| 8 min | 54.24 a |

| 10 min | 50.62 ab |

*Values with repeating alphabets for individual bacterial species show no significant difference at 0.05 (as mentioned by LSD).

3. Results

3.1. Disc diffusion assay

In vitro, the agar well diffusion method determined susceptibilities to the selected bacteria’s materials The outcomes from determining the dimension of the region of restriction encircling the plates for assessing botanical products’ antimicrobial capacity are shown in Table 2. Investigations demonstrated that the S. marianum product’s low-power laser therapy was effective against S. Typhimurium and MRSA but impotent against E. coli.

Table 2.

Effects of extracts of S. marianum plant altered by low-power laser treatment on different bacterial species determined by zone of inhibition by agar well diffusion method.

| Test Solution |

Inhibition Zone (mm) |

Bacillus sp | S. aureus | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmonella typhi | E. coli | MRSA | |||

| S. marianum extract (control) | 15 ± 1 d* | 8 ± 2c | 10 ± 2 d | 10 ± 2c | 9 ± 1b |

| S. marianum extract (laser 6 min) | 24 ± 2b | 11 ± 2b | 12 ± 1b | 16 ± 1b | 15 ± 3c |

| Imipenem 10 µg | 20 ± 3 a | 20 ± 2 a | 21 ± 2 a | 19 ± 2 a | 18 ± 2 a |

*The positive control for the antimicrobial assay is an antibiotic, imipenem, 10 µg. The remaining compounds were derived from plants in the laboratory and developed in two types of media, including a control and one consisting of Aloe Syli. Nine replicates, including three biological replicates and three technical replicates, were used to calculate each mean value. Mentioned values represent mean ± SD.

*Values with repeating alphabets for individual bacterial species show no significant difference at 0.05 (as mentioned by LSD).

3.2. Antioxidant activity

Based on the transition from violet to yellow, the DPPH radical scavenging activity for low-power laser-treated samples of the dose was assessed (Fig. 1). With scavenging effectiveness of 60.50% at 1 mg/mL laser treatment, and gallic acid demonstrated the strongest reducing action laser-treated samples of laser treated S. marianum had half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of and 0.55 mg/mL, while gallic acid had an IC50 of 0.13 mg/mL.

Fig. 1.

The estimation of antioxidant activities of laser-treated S. marianum (6 min), and the estimation of DPPH radical scavenging activity, Red is gallic acid, and blue is the laser-treated S. marianum (6 min).

According to Duncan’s test, there is a significant difference due to the presence of different alphabets (p < 0.05).

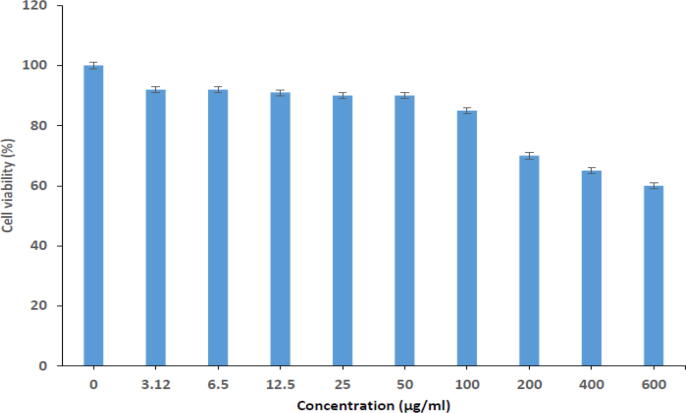

3.3. Cytotoxicity studies

Cell survival after laser radiation was investigated by employing an MTT assay on the MCF-7 cell line. Laser radiation displayed cytotoxicity at concentrations higher than the MIC (100 g/mL), as seen in Fig. 2 (Ameen, 2022).

Fig. 2.

Cytotoxicity of laser-treated S. marianum (6 min) on the MCF-7 cell line. The dose-dependent effect of low-power laser treatment was evaluated using an MTT assay after 24 h of treatment.

4. Discussion

The aqueous extract, chloroform, ethyl acetate, butanol, and raw extract are in order of best flavonoid performance. The efficiency of the extraction is correlative, and it is supposed to be paralleled with inherited characteristics of the type of bacteria used, structural characteristics of the same species (Pharmacognosie, 1999), the genesis of specie (Narayana et al., 2001), the conditions of harvesting (Lin & Weng, 2006), and the extraction methods used (Merghem et al., 1995). As a result, it is challenging to compare these results with those of the literature.

Imipenem, a type of antibiotic that belongs to the beta-lactam category, works against bacteria of all kinds, including MRSA and other tolerant ones (Moglad & Altayb, 2022).

The region of suppression has an initial width of 10 mm and an upper limit width of 24 mm for all of the investigated isolates of bacteria. Spiramycin, a macrolide, halts the production of protein in bacteria by attaching to the unit 50S ribosome and preventing the last synthesis stage from coming together (Yala et al., 2001). These bacteria are sized between 20 and 22 mm and are susceptible to imipenem 10 g.

The flavonoid extracts are listed according to their effects after analysis of their antibacterial activity and sensitivity. S. marianum extract with laser irradiation has a positive sensitivity for tested bacteria and is regarded as the most active extract. This compound has a negative impact on S. typhi, resulting in the depression of its growth and development of a zone of inhibition of greater diameters (15 mm to 24 mm) compared to S. aureus (8 mm to 11 mm). It has no significant effect on E. coli, presenting with moderate sensitivity and zone of inhibition diameters of between 8- and 11-mm S. marianum extract control and the laser-treated S. marianum (6 min), respectively. Previous studies have shown that S. marianum fruit had antibacterial effects against different bacterial species, including E. coli (Liu et al., 2023, Moglad and Altayb, 2022). In a study of methanolic extracts (Almuhayawi et al., 2021), the authors found that plates inoculated with S. typhi had larger inhibitory zones than plates inoculated with E. coli or MRSA. In contrast, inhibitory zones of comparable diameters among dishes infected with S. aureus and E. coli were seen by the authors in another work using ethanolic extract (Liu et al., 2023) and are consistently present in the current study. Increased antibacterial activity against MRSA and S. typhi, but not against E. coli, Bacillus, MRSA and S. aureus, were seen in the methanolic extracts from laser-treated S. marianum samples. HPLC confirms the separation, and it helps to recognise samples of flavonoids presenting with the different extracts. As mentioned in the standards used, we demonstrated the presence of silybin in S. marianum (control and laser treated). Mahmoudi Rad et al. (2022) and Rad et al. (2021) likewise recorded comparable outcomes (Alavi et al., 2022). With the uplifting of the silybin compound of the laser radiation, S. marianum ethanolic extract had a smaller boosting effect on antibacterial activity against E. coli than that of S. typhi. Also, bioactive components in S. marianum impact the liver and our results indicated that the laser radiation S. marianum affects S. typhi, one of the bacteria that affects the liver in the human body.

According to Hanafi et al. (2023), the decline of gram (+) microbes is due to silybin’s interference with the production of proteins and RNA; based on the efficacy of the ethyl acetate extract in our investigation, which showed the presence of the flavonolignans silibinin, discovered by high-performance liquid chromatography, against gram (+) bacteria (Hanafi et al., 2023). Geng et al. (2023) describe the effects of polyphenols on gram-positive bacteria, either by preventing the activity of enzymes required for the bacterial cell to produce energy by altering the permeability of the cell or by preventing the synthesis of ARN (Geng et al., 2023).

The laser treatment for S. marianum affects gram (+) and gram (-) bacteria. Some investigations (Falleh et al., 2008, Hayouni et al., 2007, Koné et al., 2004, Shan et al., 2007, Turkmen et al., 2007) revealed that gram (+) microbes are more vulnerable than gram-negative microbes. This can be explained by the variation between gram-positive and gram-negative units’ exterior coats.

The exterior membrane of gram (-) has an extra layer consisting of phospholipids, proteins, and lipopolysaccharides that is impenetrable to hydrophobic compounds (Georgantelis et al., 2007). However, the laser-treated S. marianum (6 min) impact on gram (-) more effectively specially on S. typhi and this regard to laser irradiation which increases silybin A + B. The control extract has an intermediate degree of sensitivity to the bacteria utilised, which results in halos that are no larger than 15 mm compared to those with laser treatment. It is significantly less active than the prior extract. When the antimicrobial efficacy of the examined compounds is assessed in relation to that of the antibiogram, the widths of the inhibitory regions established by phenolic concentrates on the development of gram (+) and gram (-) bacteria clearly vary from those generated by antimicrobial medications.

The antimicrobial capability of flavonoids is due to multiple processes of contaminants towards toxic microbes, such as the creation of hydrogen bonds with intracellular and extracellular amino acids or enzymatic agents, the electrostatic attraction of metal ions, reduced metabolic activity of bacteria, or the decomposition of substances required for bacterial development (Bessam and Mehdadi, 2014, Lobiuc et al., 2023).

There have been claims that plant extracts and numerous other phytochemical preparations high in flavonoids have antibacterial properties (Veiko et al., 2023). Important antibacterial compounds include polyphenols like tannins and flavonoids including epigallocatechin, catechin, myricetin, quercetin, luteolin, and silybin (Sun and Shahrajabian, 2023, Tawaha et al., 2023). Naringenin, quercetin, and certain catechins (flavan-3-ols) have an antimicrobial action that alters membrane permeability (Górniak et al., 2019). Flavonoids would function on several levels. It seems that the B ring plays a significant role in the intercalation with nucleic acids, which prevents the creation of DNA and RNA. The B ring’s hydroxylation appears necessary for the function of the DNA gyrase in E. coli, which Nucleic acids can also inhibit (Górniak et al., 2019).

Almuhayawi et al. (2021) identified the antioxidant function of biosynthesised lasers. They suggested using a laser as a potential free radical scavenger. Similarly, Pirvu et al. (2022) used Plantago lanceolata extract to assess the antioxidant action of lasers and found considerable free radical scavenging activity (Pirvu et al., 2022). Significant antioxidant potential was also found by Sassi Aydi et al. (2023) (IC50: 24 g/mL). The polyphenols in the extract that serve as antioxidant components and the laser that acts as a catalyst might account for the high antioxidant property of the laser (Pavon et al., 2021). Several flavonoids in the S. marianum L. extracts have antioxidant effects against DPPH radicals (Javeed et al., 2022). Therefore, before using lasers in human applications, it is crucial to assess their antioxidant activity and the laser treatment. Our findings demonstrated the potential use of laser S. marianum in vivo in clinical research by proving the safety of its use in animal cells. Laser cytotoxicity towards human cells depended on the reducing agent (Javeed et al., 2022, Miladi et al., 2019, Ameen et al., 2023). Plants may act as a reducing and stabilising agent to reduce laser toxicity by stabilising the cells.

5. Conclusion

According to our findings, the flavonoid extracts from laser-treated S. marianum (6 min) fruit have antibacterial effects on the tested microbial strains.

Due to its numerous applications in industry and healthcare, laser treatment has recently grown in importance as a subject of study. We were the first to use laser treatment with S. marianum L. extract in this study. When tested against pathogenic bacteria, S. marianum L. - laser showed broad-spectrum antibacterial activity. Furthermore, the laser exhibited no cytotoxicity at the MIC value while exhibiting strong antioxidant activity. Furthermore, the rise in silybin (A + B) level of compound in plant products after applying a 6-min laser treatment also produced an increase in antimicrobial activity towards S. typhi and MRSA, S. aureus, Bacillus and E. coli but was more effective against S. typhi.

This study highlights different flavonoid samples with antimicrobial tendency against S. marianum, and more research is required to assess the new biological activities (such as antifungal and antidiabetic) and the mechanisms of action.

Funding

The research was funded by Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice presidency for Graduate studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Al-Ahsa 31982, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Grant number Annual grant 3555.

7. Authors' contributions

The author confirms sole responsibility for the following: study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The author also acknowledges Dr. Fadia Elsherif from the department of biological sciences at the King Faisal University for providing the Silybum marianum that was used throughout the study.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Alavi M., Li L., Nokhodchi A. Metal, metal oxide and polymeric nanoformulations for the inhibition of bacterial quorum sensing. Drug Discov. Today. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2022.103392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldayel M.F. The synergistic effect of capsicum aqueous extract (Capsicum annuum) and chitosan against multidrug-resistant bacteria. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2023;35(2) [Google Scholar]

- Aldayel M.F., Al Kuwayti M.A., El Semary N.A. Investigating the production of antimicrobial nanoparticles by Chlorella vulgaris and the link to its loss of viability. Microorganisms. 2022;10(1):145. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10010145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldayel F., Alsobeg M., Khalifa A. In vitro antibacterial activities of silver nanoparticles synthesised using the seed extracts of three varieties of Phoenix dactylifera. Braz. J. Biol. 2021;82 doi: 10.1590/1519-6984.242301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S.I., Gaafar A.A., Metwally S.A., Habba I.E. The reactive influences of pre-sowing He-Ne laser seed irradiation and drought stress on growth, fatty acids, phenolic ingredients, and antioxidant properties of Celosia argentea. Sci. Hortic. 2020;261 [Google Scholar]

- Almuhayawi, M. S., Hassan, A. H. A., Abdel-Mawgoud, M., Khamis, G., Selim, S., Al Jaouni, S. K., & AbdElgawad, H. 2021. Laser light as a promising approach to improve the nutritional value, antioxidant capacity and anti-inflammatory activity of flavonoid-rich buckwheat sprouts. Food Chem, 345, 128788. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128788. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ameen F., Stephenson S.L., AlNadhari S. Isolation, identification and bioactivity analysis of an endophytic fungus isolated from Aloe vera collected from Asir desert, Saudi Arabia. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2021;44:1063–1070. doi: 10.1007/s00449-020-02507-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameen F., Al-Homaidan A.A., Al-Sabri A. Anti-oxidant, anti-fungal and cytotoxic effects of silver nanoparticles synthesized using marine fungus Cladosporium halotolerans. Appl. Nanosci. 2023;13:623–631. doi: 10.1007/s13204-021-01874-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ameen, F.2022. Green synthesis spinel ferrite nanosheets and their cytotoxicity and antibacterial activity. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 10.1007/s13399-022-03638-z. [DOI]

- Behl T., Bungau S., Kumar K., Zengin G., Khan F., Kumar A., Kaur R., Venkatachalam T., Tit D.M., Vesa C.M. Pleotropic effects of polyphenols in cardiovascular system. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020;130 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessam F., Mehdadi Z. Evaluation of the antibacterial and antifongigal activity of different extracts of flavonoïques Silybum Marianum L. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2014;8:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bhilegaonkar K.N., Kolhe R.P. Present Knowledge in Food Safety. Elsevier; 2023. Transfer of viruses implicated in human disease through food; pp. 786–811. [Google Scholar]

- Dey P., Ray Chaudhuri S. Cancer-associated microbiota: from mechanisms of disease causation to microbiota-centric anti-cancer approaches. Biology. 2022;11(5):757. doi: 10.3390/biology11050757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Garhy H.A., Khattab S., Moustafa M.M., Abou Ali R., Azeiz A.Z.A., Elhalwagi A., El Sherif F. Silybin content and overexpression of chalcone synthase genes in Silybum marianum L. plants under abiotic elicitation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016;108:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falleh H., Ksouri R., Chaieb K., Karray-Bouraoui N., Trabelsi N., Boulaaba M., Abdelly C. Phenolic composition of Cynara cardunculus L. organs, and their biological activities. C. R. Biol. 2008;331(5):372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierascu R.C., Sieniawska E., Ortan A., Fierascu I., Xiao J. Fruits by-products – A source of valuable active principles. A short review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020;8:319. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foghis M., Bungau S.G., Bungau A.F., Vesa C.M., Purza A.L., Tarce A.G., Tit D.M., Pallag A., Behl T., ul Hassan S.S. Plants-based medicine implication in the evolution of chronic liver diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023;158 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.114207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gad D., Elhaak M., Pompa A., Mattar M., Zayed M., Fraternale D., Dietz K.-J. A new strategy to increase production of genoprotective bioactive molecules from cotyledon-derived Silybum marianum L. Callus. Genes. 2020;11(7):791. doi: 10.3390/genes11070791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y., Yuan Y., Bao Y., Huang S., Wang X., Huang L., She C., Gong X., Xiong M. pH window for high selectivity of ionizable antimicrobial polymers toward bacteria. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023;15(18):21781–21791. doi: 10.1021/acsami.2c23240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgantelis D., Ambrosiadis I., Katikou P., Blekas G., Georgakis S.A. Effect of rosemary extract, chitosan and α-tocopherol on microbiological parameters and lipid oxidation of fresh pork sausages stored at 4 C. Meat Sci. 2007;76(1):172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Górniak I., Bartoszewski R., Króliczewski J. Comprehensive review of antimicrobial activities of plant flavonoids. Phytochem. Rev. 2019;18(1):241–272. doi: 10.1007/s11101-018-9591-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini A., Tedesco D.E.A. Restoring activity of milk thistle (Silybum marianum L.) on serum biochemical parameters, oxidative status, immunity, and performance in poultry and other animal species, poisoned by mycotoxins: A review. Animals. 2023;13(3):330. doi: 10.3390/ani13030330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanafi A., Safa K.D., Rezazadeh S. Nanoemulsion of Silybum marianum seeds extract: Evaluation of stability, antioxidant and antibacterial activity. Colloid J. 2023:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hayouni, E. A., Abedrabba, M., Bouix, M., & Hamdi, M. 2007. The effects of solvents and extraction method on the phenolic contents and biological activities in vitro of Tunisian Quercus coccifera L. and Juniperus phoenicea L. fruit extracts. Food Chemistry, 105(3), 1126-1134. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.02.010. [DOI]

- Hurtová M., Káňová K., Dobiasová S., Holasová K., Čáková D., Hoang L., Biedermann D., Kuzma M., Cvačka J., Křen V. Selectively halogenated flavonolignans—Preparation and antibacterial activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23(23):15121. doi: 10.3390/ijms232315121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javeed, A., Ahmed, M., Sajid, A. R., Sikandar, A., Aslam, M., Hassan, T. u., Samiullah, Nazir, Z., Ji, M., & Li, C. 2022. Comparative assessment of phytoconstituents, antioxidant activity and chemical analysis of different parts of milk thistle Silybum marianum L. Molecules, 27(9), 2641. https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/27/9/2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Karasawa M.M.G., Mohan C. Fruits as prospective reserves of bioactive compounds: a review. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2018;8:335–346. doi: 10.1007/s13659-018-0186-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimek-Kopyra A., Czech T. Complementary photostimulation of seeds and plants as an effective tool for increasing crop productivity and quality in light of new challenges facing agriculture in the 21st century—A case study. Plants. 2022;11(13):1649. doi: 10.3390/plants11131649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koné W.M., Atindehou K.K., Terreaux C., Hostettmann K., Traoré D., Dosso M. Traditional medicine in north Côte-d'Ivoire: screening of 50 medicinal plants for antibacterial activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004;93(1):43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.-K., Weng M.-S. Flavonoids as nutraceuticals. Sci. Flavonoids. 2006:213–238. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Li Y., Chen G.-J., Chen D.-Y., Sun B., Yin Z. Coupling amino acid with THF for the synergistic promotion of CO2 hydrate micro kinetics: Implication for hydrate-based CO2 sequestration. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023;11(15):6057–6069. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c00593. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lobiuc A., Pavăl N.-E., Mangalagiu I.I., Gheorghiță R., Teliban G.-C., Amăriucăi-Mantu D., Stoleru V. Future antimicrobials: Natural and functionalized phenolics. Molecules. 2023;28(3):1114. doi: 10.3390/molecules28031114. https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/28/3/1114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi Rad Z., Nourafcan H., Mohebalipour N., Assadi A., Jamshidi S. Antibacterial effect of methanolic extract of milk thistle seed on 8 species of gram-positive and negative bacteria. J. Plant Res. (Iran. J. Biol.) 2022;35(4):776–785. [Google Scholar]

- Mariappan B., Kaliyamurthi V., Binesh A. Recent Advances in Aquaculture Microbial Technology. Elsevier; 2023. Medicinal plants or plant derived compounds used in aquaculture; pp. 153–207. [Google Scholar]

- Maślak E., Arendowski A., Złoch M., Walczak-Skierska J., Radtke A., Piszczek P., Pomastowski P. Silver nanoparticle targets fabricated using chemical vapor deposition method for differentiation of bacteria based on lipidomic profiles in laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. Antibiotics. 2023;12(5):874. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12050874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merghem R., Jay M., Viricel M.-R., Bayet C., Voirin B. Five 8-C-benzylated flavonoids from Thymus hirtus (Labiateae) Phytochemistry. 1995;38(3):637–640. [Google Scholar]

- Miladi, M., Khemais, A., Ben Hamouda, A., Boughattas, I., Mhafdhi, M., Acheuk, F., & Ben Halima, M. 2019. Physiological, histopathological and cellular immune effects of Pergularia tomentosa extract on Locusta migratoria nymphs. 2-13. 10.1016/S2095-3119(19)62704-8. [DOI]

- Moglad E.H., Altayb H.N. Antibiogram, prevalence of methicillin-resistant and multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus spp. in different clinical samples. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022;29(12) doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2022.103432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayana K.R., Reddy M.S., Chaluvadi M., Krishna D. Bioflavonoids classification, pharmacological, biochemical effects and therapeutic potential. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2001;33(1):2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pavon J., Agurto Muñoz A., Figueroa C., Agurto C. Current analytical techniques for the characterization of lipophilic bioactive compounds from microalgae extracts. Biomass Bioenergy. 2021;149 doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2021.106078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacognosie, B. J. 1999. phytochimie, plantes médicinales. Revue et Augmentée, Tec & Doc, Paris.

- Pirvu, L. C., Nita, S., Rusu, N., Bazdoaca, C., Neagu, G., Bubueanu, C., Udrea, M., Udrea, R., & Enache, A. 2022. Effects of laser irradiation at 488, 514, 532, 552, 660, and 785 nm on the aqueous extracts of plantago lanceolata L.: A comparison on chemical content, antioxidant activity and Caco-2 viability. Applied Sciences, 12(11), 5517. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/12/11/5517.

- Rad Z.M., Nourafcan H., Mohebalipour N., Assadi A., Jamshidi S. Effect of salicyllc acid foliar application on phytochemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of silybum marianum. Iraqi J. Agric. Sci. 2021;52(1):63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Rana A., Chaudhary A.K., Saini S., Srivastava R., Kumar M., Sharma S.N. Ultrafast transient absorption spectroscopic (UFTAS) and antibacterial efficacy studies of phytofabricated silver nanoparticles using Ocimum Sanctum leaf extract. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2023;147 [Google Scholar]

- Sassi Aydi S., Aydi S., Ben Khadher T., Ktari N., Merah O., Bouajila J. Polysaccharides from South Tunisian Moringa alterniflora leaves: Characterization, cytotoxicity, antioxidant activity, and laser burn wound healing in rats. Plants. 2023;12(2):229. doi: 10.3390/plants12020229. https://www.mdpi.com/2223-7747/12/2/229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan B., Cai Y.Z., Brooks J.D., Corke H. The in vitro antibacterial activity of dietary spice and medicinal herb extracts. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007;117(1):112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W., Shahrajabian M.H. Therapeutic potential of phenolic compounds in medicinal plants—Natural health products for human health. Molecules. 2023;28(4):1845. doi: 10.3390/molecules28041845. https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/28/4/1845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppakul P., Miltz J., Sonneveld K., Bigger S.W. Antimicrobial properties of basil and its possible application in food packaging. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51(11):3197–3207. doi: 10.1021/jf021038t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawaha A.R.A., Abukhader R., Qaisi A., Dey A., Al-Tawaha A.R., Ali I. In: Recent Frontiers of Phytochemicals. Pati S., Sarkar T., Lahiri D., editors. Elsevier; 2023. Chapter 36 - Bioactivity of essential oils and its medicinal applications; pp. 617–628. [Google Scholar]

- Turkmen N., Velioglu Y.S., Sari F., Polat G. Effect of extraction conditions on measured total polyphenol contents and antioxidant and antibacterial activities of black tea. Molecules. 2007;12(3):484–496. doi: 10.3390/12030484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiko, A. G., Olchowik-Grabarek, E., Sekowski, S., Roszkowska, A., Lapshina, E. A., Dobrzynska, I., Zamaraeva, M., & Zavodnik, I. B. 2023. Antimicrobial activity of quercetin, naringenin and catechin: Flavonoids inhibit staphylococcus aureus-induced hemolysis and modify membranes of bacteria and erythrocytes. Molecules, 28(3). 10.3390/molecules28031252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wu X., Shin S., Gondhalekar C., Patsekin V., Bae E., Robinson J.P., Rajwa B. Rapid food authentication using a portable laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy system. Foods. 2023;12(2):402. doi: 10.3390/foods12020402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yala, D., Merad, A., & Mohamedi, D., Ouar Korich, M. N. (2001). Classification et mode d'action des antibiotiques, médecine du Maghreb (91).

- Yao C., Huang W., Liu Y., Yin Z., Xu N., He Y., Wu X., Mai K., Ai Q. Effects of dietary silymarin (SM) supplementation on growth performance, digestive enzyme activities, antioxidant capacity and lipid metabolism gene expression in large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) larvae. Aquac. Nutr. 2020;26(6):2225–2234. [Google Scholar]

- Yap Y.-K., El-Sherif F., Habib E.S., Khattab S. Moringa oleifera leaf extract enhanced growth, yield, and silybin content while mitigating salt-induced adverse effects on the growth of Silybum marianum. Agronomy. 2021;11(12):2500. [Google Scholar]