Abstract

Background and aims

Diabetes mellitus (DM) may have different adverse effects on the male reproductive system. Zinc (Zn) is one of the necessary elements in the human and mammalian diet that plays an important role in scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) by providing antioxidant and anti-apoptotic properties. The aim of this study was to determine the protective effects of zinc supplements on sperm chromatin and the evaluation of sperm deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) integrity in diabetic men.

Methods

In this interventional study, 43 infertile Iranian men in diabetic and non-diabetic groups were included. They were then randomly divided into two subgroups: normal saline intake and zinc sulfate intake (25 mg orally for 64 days each). Different indices of sperm analysis (number, morphology and motility) and testosterone levels were evaluated in four groups. Protamine deficiency and DNA fragmentation were assessed using chromomycin A3 (CMA3) and sperm chromatin dispersion (SCD) methods, respectively.

Results

Zinc supplementation reduced the deformity of neck and head of sperms (p < 0.05), as well as deformity of sperm tail in infertile diabetic men. Zinc administration ameliorated sperm motility types A, B and C (p < 0.05). Moreover, zinc administration reduced abnormal morphology and DNA fragmentation of sperms, which increased the SCD1 and SCD2 and reduced the SCD3 and SCD4 in both treated groups.

Conclusion

Zinc supplementation, as a powerful complement, is able to balance the effect of diabetes on sperm parameters, sperm chromatin and DNA integrity. Consequently, zinc supplementation can probably be considered a supportive compound in the diet of diabetic infertile men.

Keywords: Sperm, Infertile, Male, Semen, Zinc

Background

Infertility is a prevalent condition defined by failure in spontaneous pregnancy after one year of regular unprotected intercourse [1]. Approximately 50% of infertility is due to male factor, and about 15–30% of male infertility is caused by genetic disorders [2, 3]. In most infertile men, there is a defect in sperm production that disrupts the formation and maturity of sperm in the testis and epididymis [4]. As spermatogenesis proceeds, 85% of the histone nucleoproteins are replaced by transition proteins, which are consequently replaced by small, arginine-rich proteins known as protamine [5]. These alterations give a compact, denaturation-resistant structure to the chromatin. This protects the chromatin against environmental stresses and facilitates sperm motility [6]. Sperm protamine deficiency has been widely reported in infertility investigations. Protamine-1 and protamine-2 concentrations have an inverse correlation with deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fragmentation; in such a way that DNA fragmentation occurs more frequently in protamine-deficient sperm [7].

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic disorder that manifests with hyperglycemia, often associated with impaired insulin secretion with other metabolic problems, including disruption of protein, lipid and carbohydrate metabolism [8]. In patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, the prevalence of infertility was reported to be 35.1%. About one-half of these patients were overweight, and 29.1% were obese [9]. The results of the study show that DM reduces serum levels of testosterone, luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), causing loss of sperm count and impotence, which in some cases may lead to infertility [10]. Study done by Ghasemi et al. has shown that high serum glucose levels caused lower fertility potential in diabetic men; hyperglycemia changes the quality of the sperm and its function by inducing molecular modification and sperm chromatin quality [11].

Zinc (Zn) is a micronutrient abundantly present in meat and seafood. Zinc is a cofactor for more than 80 metalloid enzymes involved in DNA transcription and protein synthesis that play an essential role in scavenging reactive oxygen species through anti-apoptotic and antioxidant properties [12]. Our previous study found that zinc supplements had a protective effect on sperm parameters and chromatin health in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats [13]. The zinc concentration in seminal human plasma is higher than in other tissues. Also, zinc is a metalloid protein cofactor for DNA-binding proteins with Zn fingers. It is part of copper(Cu)/zinc superoxide dismutase and several proteins involved in the repair of damaged DNA (e.g., P53, which is mutated in half of the human tumors) and in the transcription and translation processes [12]. Zinc has an important role in testes development and sperm physiologic functions, and decreasing its levels causes hypogonadism, a decrease in testes volume and atrophy of seminiferous tubules; recent studies assumed that zinc insufficiency could impair antioxidant defences and may be an important risk factor in oxidant release, compromising the mechanism of DNA repair and making the sperm cell highly susceptible to oxidative damage [12–14]. Considering the antioxidant properties of zinc sulfate against reproductive system defects and sperm disorders, we are interested in investigating the protective effects of zinc supplementation on sperm quality and chromatin parameters in diabetic patients.

Methods

Chemicals

Phosphate-buffered saline(PBS), Tris(hydroxyl methyl)amino methane, dithiothreitol (DTT), sodium dodecyl sulfate(SDS), ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), borate and chromomycin A3 (CMA3) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich chemical company (St Louis, MO, USA). All chemicals and reagents used were analytical grades.

Patients and study plan

This study was completed in 2016, and all the patients available to the researcher were included. Since only 43 samples were available to the researcher, sampling was not done, and all these cases were included in the study. The study's small sample size is due to the lack of samples, and the researcher has used all available samples.

These patients referred to the Afzalipour infertility center in Kerman, Iran, ages 25-40 years old, classified as male infertility, were randomly assigned to this s interventional study. Patients were divided into two groups: diabetic and non-diabetic groups. The target samples and patients were examined by an endocrinologist, and their diabetic status was confirmed. Patients were divided into two groups, diabetic and non-diabetic, after endocrinologist’s opinion. Each group was randomly allocated into two subgroups by administration of normal saline orally (25 mg) or syrup zinc sulfate supplement orally (25 mg) once daily for 64 days. Sperm parameters were measured before and after zinc sulfate administration within four groups. Semen analysis and sperm parameters were determined by the World health organization (WHO) criteria.

Sample collection and semen analysis

Semen samples were taken after 3–7 days of abstinence and collected into a non-toxic sterile container. Semen analyses were performed according to the WHO criteria: Sperm concentration less than 10 × 106/ml, and progressive motile spermatozoa less than 32% were considered to be male infertility factors [15].

Specific parameters of sperm, including morphological and structural characteristics (head, neck and tail deformity), sperm motility and chromatin abnormalities, were evaluated by the HFT 6.5 computer-aided semen analysis (CASA) method. Analysis of all forms of deformity in the head, neck and tail of the sperm was measured.

Sperm chromatin dispersion (SCD)

In the current study, sperm DNA integrity was assessed via SCD test (Halosperm kit, INDAS laboratories, Spain); sperm's DNA dispersion disrupts DNA strands rearrangement and causes the absence of a halo or observation of a very small halo around the sperm's head. The clinical threshold of SCD is 30%, which means that the specimens can have up to 30% of chromatin dispersion and are still normal. SCD cannot distinguish between single-stranded and double-stranded DNA damage. As it is not fluorescent dependent, it can be used as a simple, fast, and reliable method. It also does not require an experienced operator to analyze the test results [16].

Protamine deficiency assessment

Protamine deficiency was measured using chromomycin A3(CMA3) staining method [17]. Briefly, semen samples were washed with PBS and centrifuged three times (3000 rpm for 5 min). An equal volume of the fixations Carnoy’s solution (methanol and acetic acid: 3/1) was added to the washed sperm and placed at 4 °C for 5 minutes. It consequently was spread onto glass slides and stained with 100 μl of 0.25 % CMA3 solution (0.25 mg CMA3 in 1 ml Mc-Elvin's Buffer, pH 7.0) in a dark environment for 20 minutes.

The slides were washed by using PBS and then mounted. A total of 200 sperms per slide were examined using a fluorescence microscope (Japan-Nikon-Eclipse600) with a suitable filter (460–470 nm) at a magnification of 100 X, and the percentage of CMA3 positive and negative CMA3 sperms were calculated.

Statistical analysis

Graph pad prism software version 5 was utilized for data analysis. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM, and all statistical comparisons were made by means of a one-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

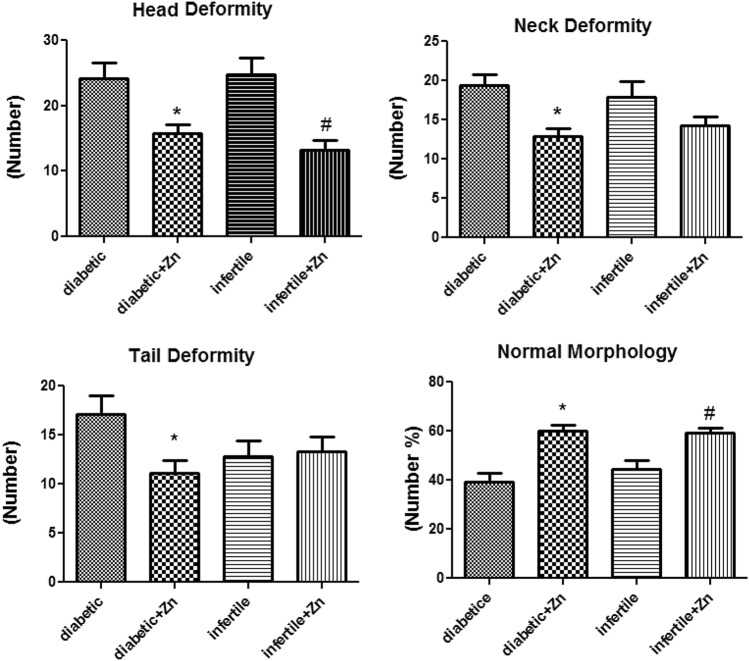

In the present study, sperm parameters, protamine deficiency and DNA fragmentation of samples from infertile and diabetic infertile men were measured. Sperm analysis with computer-aided semen analysis (CASA) method showed that administration of zinc sulfate resulted in a significant reduction in neck deformity (p value: 0.021) and head deformity (p value: 0.001) in both infertile and infertile diabetic men (p < 0.05). It also increased the normal morphology in both treated groups (p value: 0.03) (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Assessment of human sperm morphology and deformity following 64 days of treatment with zinc sulfate supplement in infertile patients. Control group (n: 10): the infertile men that received normal saline. Infertile+ Zn group (n: 11): the infertile men that received zinc sulfate supplement. Diabetic group (n: 11): the diabetic men that received normal saline. Diabetic+ Zn group (n: 11): the diabetic men that received zinc sulfate supplement. *Significantly different from the control groups (*p < 0.05). # Significantly different from the zinc sulfate administration group (#p < 0.05)

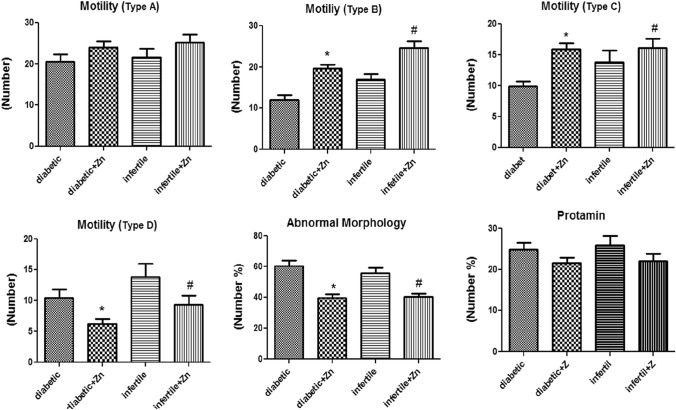

In addition, zinc sulfate treatment in infertile diabetic men caused a significant reduction in tail deformity (p value: 0.028). Zinc administration also increased sperm motility type A, B, and C in both infertile and infertile diabetic men. The increase in motility of sperm type B (p value: 0.01) and sperm type C (p value: 0.024) was significantly higher after treatment. In terms of motility of sperm type D, zinc supplementation decreased motility in both groups (p value: 0.02).

Zinc administration significantly decreased abnormal morphology (p value: 0.02). The protamine deficiency was reduced in groups where zinc was administered, but no statistically significant difference was observed (p value: 0.07). The reduction in abnormal morphology was significant in both groups (p value: 0.014) (Figure 2).

Fig. 2.

Assessment of human sperm motility, abnormal morphology and protamine deficiency following 64 days of treatment with zinc sulfate supplement in infertile patients. Data were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Control group (n: 10): the infertile men that received normal saline. Infertile+ Zn group (n: 11): the infertile men that received zinc sulfate supplement. Diabetic group (n: 11): the diabetic men that received normal saline. Diabetic+ Zn group (n: 11): the diabetic men that received zinc sulfate supplement. *Significantly different from the control groups (*p < 0.05). # Significantly different from the zinc sulfate administration group (#p< 0.05)

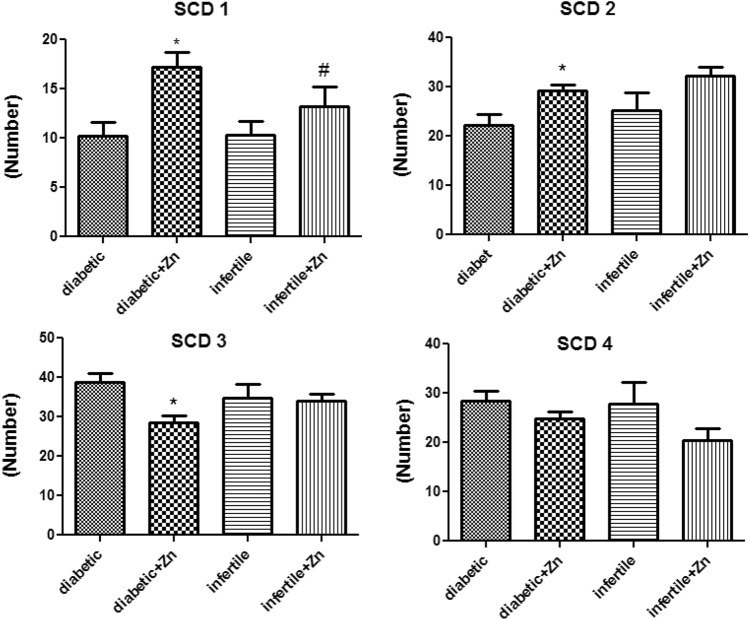

For better evaluation of the effect of zinc on the sperm, DNA fragmentation was also assessed by the sperm chromatin dispersion (SCD) methods. It showed that zinc sulfate could increase SCD1 and SCD2 and reduce SCD3 and SCD4 in both treated groups (Figure 3).

Fig. 3.

Assessment of sperm chromatin dispersion (SCD) after 64 days of treatment with zinc sulfate supplement in infertile patients. Data were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Control group (n: 10): the infertile men that received normal saline. Infertile+ Zn group (n: 11): the infertile men that received zinc sulfate supplement. Diabetic group (n: 11): the diabetic men that received normal saline. Diabetic+ Zn group (n: 11): the diabetic men that received zinc sulfate supplement. *Significantly different from the control groups (*p < 0.05). # Significantly different from the zinc sulfate administration group (#p < 0.05)

Discussion

The disorders of male reproductive system play an important role in infertility; at the molecular level, fertility results from a successful connection between sperm and oocyte [17, 18]. The quality and the number of sperm are among the leading factors affecting reproductive quality [19].

According to the present study, sperm parameters in the groups administered zinc sulfate were improved; in other words, sperm count, normal sperm motility and the amount of sperm protamine were significantly improved. The human sperm DNA fragmentation may have adverse effects on reproduction; accordingly, 10% of the sperm from fertile men and a higher percentage (20-25%) of the sperm from infertile men possess assessable levels of DNA abnormality [20].

In spermatogenesis, almost 85% of the histone proteins are replaced by protamine; it caused condensing of the sperm's nucleus, which is important for protecting the sperm's genome [21]. The relationship between chromatin abnormalities and abnormal sperm morphology with fertilization rates has been extensively investigated in assisted reproductive techniques such as in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) [22]. In agreement with our data, Simon et al. distinguished that sperm morphology and chromatin anomalies have the highest relationship with infertility rate [23]. Sperm with chromatin anomalies disrupts the fertilization process due to the inadequacy of the mitoses promoting factor (MPF). In the present study, the administration of zinc supplements significantly improved sperm chromatin deficiency and increased the protamine content; also, in agreement with our data, Ni K et al. showed a significant relationship between protamine deficiency and fertilization rates [7]. Therefore, the spermatogenesis process associated with the lowest DNA fragmentation and the genetic structure of the sperm nucleus is preserved [24]. As a result, in the development and formation of sperm chromatin, zinc supplementation effectively controlled the testicular function in a way that differentiates the highest quality sperm 13. In another research by McKelvey-Martin and colleagues, the rate of DNA fragmentation in the sperm of fertile and infertile men was investigated. Their findings showed that the average level of damage in the sperm DNA was 20% [25]. Administration of zinc sulfate supplement has improved the function of the cellular protamine; it also effectively maintains the sperm's fertility characteristics by conserving the DNA structure of the nucleus and forming the spherical hydrodynamic head, which improved sperm motility in agreement with our data. It seems expected the overproduction of ROS in seminal plasma in diabetic cases can affect the testicular activity and sperm quality through seminal antioxidant defence mechanisms.

Limitation

One of the most critical limitations of the current study is the small sample size, which challenges the study's conclusion, considering that the researcher has used all the available samples. Therefore, conducting future studies with a larger sample size is recommended to get more detailed information.

Conclusion

DNA fragmentation and protamine deficiency rates were reduced after zinc sulfate administration in infertile men. This may be due to zinc’s antioxidant role. The generation of ROS in seminal plasma in diabetic men can induce cell failure and disturb the male reproductive function; furthermore, it causes an adverse change in chromatin quality and sperm parameters. The present study confirmed that zinc sulfate administration in diabetic men enhanced sperm fertility characteristics and reduced DNA fragmentation. These protective effects may be due to the antioxidant effect of zinc and elimination of free radicals.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank of Afzalipour infertility center of Kerman. Also, this work was supported by the grant number of [IR.GERUMS.RE.1396.1077] provided by the deputy of research affairs of Gerash university of medical sciences, Gerash, Iran.

Abbreviations

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- CMA3

Chromomycin A3

- SCD

Sperm chromatin dispersion

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- DTT

Dithiothreitol

- SDS

Sodium dodecyl sulfate

- EDTA

Ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid

Funding

The Deputy of Research Affairs of Gerash University of Medical Sciences [IR] provided funding for this research.GERUMS.RE.1396.1077]. The Deputy of Research Affairs of Gerash University of Medical Sciences had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and writing of the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was received from the ethics committee of the deputy of research affairs of Gerash University of medical sciences. Reference Number: IR.GERUMS.RE.1396.1077. All procedures performed in this study were performed in accordance with the ethical standards contained in the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Conscious consent was also obtained in writing from all study participants.

Footnotes

Hakimeh Akbari: is an Assistant Professor at the Cellular and Molecular Research Center, Gerash University of Medical Sciences, Gerash, Iran; Leila Elyasi: is an Assistant Professor at the Neuroscience Research Center, Department of Anatomy, Golestan University of Medical Sciences, Gorgan, Iran; Ali Asghar Khaleghi: is an Assistant Professor at Cellular and Molecular Research Center, Gerash University of Medical Sciences, Gerash, Iran; Masoud Mohammadi is a faculty member, Cellular and Molecular Research Center, Gerash University of Medical Sciences, Gerash, Iran.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Salehi M, Akbari H, Heidari MH, Molouki A, Murulitharan K, Moeini H, et al. Correlation between human clusterin in seminal plasma with sperm protamine deficiency and DNA fragmentation. Mol Reprod Dev. 2013;80:718–724. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jamalvandi M, Motovali-Bashi M, Amirmahani F, Darvishi P, Goharrizi KJ. Association of T/A polymorphism in miR-1302 binding site in CGA gene with male infertility in Isfahan population. Mol Biol Rep. 2018;45:413–417. doi: 10.1007/s11033-018-4176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brugh VM, Lipshultz LI. Male factor infertility: evaluation and management. Med Clin. 2004;88:367–385. doi: 10.1016/S0025-7125(03)00150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan W. Male infertility caused by spermiogenic defects: lessons from gene knockouts. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;306:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zini A, San Gabriel M, Zhang X. The histone to protamine ratio in human spermatozoa: comparative study of whole and processed semen. Fertility Sterility. 2007;87:217–219. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steger K, Balhorn R. Sperm nuclear protamines: A checkpoint to control sperm chromatin quality. Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia. 2018;47(4):273–279. doi: 10.1111/ahe.12361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ni K, Spiess AN, Schuppe HC, Steger K. The impact of sperm protamine deficiency and sperm DNA damage on human male fertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Andrology. 2016;4:789–799. doi: 10.1111/andr.12216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diab Care. 2014;37:S81–S90. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bener A, Al-Ansari AA, Zirie M, Al-Hamaq AO. Is male fertility associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus? Int Urol Nephrol. 2009;41:777–784. doi: 10.1007/s11255-009-9565-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Qaisi J, Hussein Z. Effect of diabetes mellitus type 2 on pituitary gland hormones (FSH, LH) in men and women in Iraq. J Al-Nahrain Univ-Sci. 2012;15:75–79. doi: 10.22401/JNUS.15.3.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghasemi M, Talebi A, Rahmanyan M, Nahangi H, Ghanizadeh T. Effects of diabetes mellitus type 2 on semen parameters. SSU J. 2017;25:621–628. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebisch I, Thomas C, Peters W, Braat D, Steegers-Theunissen R. The importance of folate, zinc and antioxidants in the pathogenesis and prevention of subfertility. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;13:163–174. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forouzandeh H, Ghavamizadeh M. Protective effects of zinc supplement on chromatin deficiency and sperm parameters in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Int Med J. 2020;27(5):545–548. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colagar AH, Marzony ET, Chaichi MJ. Zinc levels in seminal plasma are associated with sperm quality in fertile and infertile men. Nutr Res. 2009;29:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamb DJ. World Health Organization laboratory manual for the examination of human semen and sperm-cervical mucus interaction. J Androl. 2000;21:32–32. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evenson DP. The Sperm Chromatin Structure Assay (SCSA®) and other sperm DNA fragmentation tests for evaluation of sperm nuclear DNA integrity as related to fertility. Anim Reprod Sci. 2016;169:56–75. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2016.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fortes MR, Satake N, Corbet D, Corbet N, Burns B, Moore S, Boe-Hansen G. Sperm protamine deficiency correlates with sperm DNA damage in B os indicus bulls. Andrology. 2014;2:370–378. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2014.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barratt CL, Mansell S, Beaton C, Tardif S, Oxenham SK. Diagnostic tools in male infertility—the question of sperm dysfunction. Asian J Androl. 2011;13:53. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee NP, Cheng CY. Nitric oxide/nitric oxide synthase, spermatogenesis, and tight junction dynamics. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:267–276. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.021329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agarwal A, Majzoub A, Esteves SC, Ko E, Ramasamy R, Zini A. Clinical utility of sperm DNA fragmentation testing: practice recommendations based on clinical scenarios. Transl Androl Urol. 2016;5:935. doi: 10.21037/tau.2016.10.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.García-Peiró A, Martínez-Heredia J, Oliver-Bonet M, Abad C, Amengual MJ, Navarro J, et al. Protamine 1 to protamine 2 ratio correlates with dynamic aspects of DNA fragmentation in human sperm. Fertility Sterility. 2011;95:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osman A, Alsomait H, Seshadri S, El-Toukhy T, Khalaf Y. The effect of sperm DNA fragmentation on live birth rate after IVF or ICSI: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2015;30:120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simon L, Zini A, Dyachenko A, Ciampi A. Carrell DTA systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the effect of sperm DNA damage on in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcome. Asian J Androl. 2017;19:80. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.182822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashkanani M, Farhadi B, Ghanbarzadeh E, Akbari H. Study on the protective effect of hydroalcoholic Olive Leaf extract (oleuropein) on the testis and sperm parameters in adult male NMRI mice exposed to Mancozeb. Gene Rep. 2020;21:100870. doi: 10.1016/j.genrep.2020.100870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis SE, Simon L. Clinical implications of sperm DNA damage. Hum Fertility. 2010;13:201–207. doi: 10.3109/14647273.2010.528823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]