Abstract

Objective

Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) have been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular complications, which largely drive diabetes’ health and economic burdens. Trial results indicated that SGLT2i are cost effective. However, these findings may not be generalizable to the real-world target population. This study aims to evaluate the cost effectiveness of SGLT2i in a routine care type 2 diabetes population that meets Dutch reimbursement criteria using the MICADO model.

Methods

Individuals from the Hoorn Diabetes Care System cohort (N = 15,392) were filtered to satisfy trial inclusion criteria (including EMPA-REG, CANVAS, and DECLARE-TIMI58) or satisfy the current Dutch reimbursement criteria for SGLT2i. We validated a health economic model (MICADO) by comparing simulated and observed outcomes regarding the relative risks of events in the intervention and comparator arm from three trials, and used the validated model to evaluate the long-term health outcomes using the filtered cohorts’ baseline characteristics and treatment effects from trials and a review of observational studies. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of SGLT2i, compared with care-as-usual, was assessed from a third-party payer perspective, measured in euros (2021 price level), using a discount rate of 4% for costs and 1.5% for effects.

Results

From Dutch individuals with diabetes in routine care, 15.8% qualify for the current Dutch reimbursement criteria for SGLT2i. Their characteristics were significantly different (lower HbA1c, higher age, and generally more preexisting complications) than trial populations. After validating the MICADO model, we found that lifetime ICERs of SGLT2i, when compared with usual care, were favorable (< €20,000/QALY) for all filtered cohorts, resulting in an ICER of €5440/QALY using trial-based treatment effect estimates in reimbursed population. Several pragmatic scenarios were tested, the ICERs remained favorable.

Conclusions

Although the Dutch reimbursement indications led to a target group that deviates from trial populations, SGLT2i are likely to be cost effective when compared with usual care.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40273-023-01286-3.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) have been recommended in diabetes guidelines and shown to be cost effective. However, existing model-based cost-effectiveness analyses of SGLT2i have limitations regarding their representativeness, the integration of all treatment effects and the lack of real-world evidence. |

| Dutch reimbursement criteria of SGLT2i represent 16% of individuals with diabetes. Their characteristics significantly differ from SGLT2i trial populations. for individuals who qualified for reimbursement, SGLT2i were cost effective at €5440/QALY compared with care-as-usual. Several pragmatic scenarios were tested; the cost effectiveness estimation remained favorable. the MICADO model well captured the benefit of SGLT2i, with less than 25% mean absolute percentage error in incidence prediction of complications over the trial’s follow-up period. |

| The MICADO model was a useful tool to simulate the disease progression of individuals with diabetes, keep track of costs and quality-adjusted life years, and support decision-making. Although the reimbursement criteria will result in a different target group compared with trials, SGLT2i can be considered cost effective in a routine care population. |

Introduction

Global health expenditures due to diabetes mellitus have increased from $232 billion in 2007 to $966 billion in 2021 for adults aged 20–79 years, representing a 316% increase over 15 years and accounting for 11.5% of total global health spending in 2021 [1]. Cardiovascular complications, accounting for nearly half of the total mortality rate in type 2 diabetes (T2D), are the main drivers of the diabetes-related economic burden [2], and around 30% of diabetes expenditure are related to treatments [3, 4]. Therefore, treatments reducing cardiovascular complication rates have great potential to achieve better cost-effectiveness than current treatment by reducing health-care expenditures and increasing quality-adjusted life years (QALYs).

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) are a new class of oral antidiabetic medication that, among other mechanisms not yet fully known, inhibit glucose reabsorption in the kidneys, leading to increased glucose excretion in the urine [5]. SGLT2i, including empagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and canagliflozin, have been studied in several randomized clinical trials (RCTs), such as the Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (EMPA-REG) for empagliflozin [6], the CANagliflozin cardioVascular Assessment Study (CANVAS) for canagliflozin [7], and the Multicenter Trial to Evaluate the Effect of Dapagliflozin on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Events (DECLARE-TIMI58) for dapagliflozin [8]. Based on these RCTs, SGLT2i are proven effective in terms of reducing risks for cardiovascular disease, including heart failure or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), in addition to their effect as oral antidiabetic agents [9, 10]. The cost and effectiveness of the three SGLT2i were comparable [11].

SGLT2i are now widely approved as antihyperglycemic therapies for individuals with T2D [12] and are recommended for individuals with T2D and established ASCVD in American [13] and European guidelines [14] in almost all cases, except when the cost is a major concern [13]. Compared to conventional glucose-lowering treatment such as metformin and sulfonylurea, SGLT2i are expensive. They cost on average €256.2 per patient per year (more than seven times as much as metformin or sulfonylurea) in 2021 in The Netherlands [15]. Nevertheless, they have been consistently shown to be cost effective in several healthcare systems (e.g., USA, UK, and Greece, etc.) [16].

However, three main challenges limit the generalizability of the current cost-effectiveness analyses. First, the inclusion criteria of the trial-recruited study population limit their generalizability to other populations. Although using trial-based evidence on treatment effects to support new reimbursement requests is conventional, trial-based economic evaluation analysis might not represent the cost-effectiveness of a different target population [17]. This general problem with trials holds for the SGLT2i studies because their study populations were quite specific [17]. For example, EMPA-REG included individuals with established ASCVD [6], which represents only 21% of the European T2D population [18].

Second, within diabetes models, cardiovascular risks are commonly estimated based on published risk equations (e.g., UKPDS risk engine [19] or Qrisk3 [20]), and treatment effects are conveyed through their impact on risk factors. However, the cardiovascular benefits of SGLT2i are beyond the modification of HbA1c and weight [14, 21]. Thus, the cardiovascular effects cannot be fully evaluated by treatment-induced risk-factor level changes in prediction models [22, 23]. Therefore, it is essential to investigate the impact on cost effectiveness in a model-based health economic evaluation where treatment effects are modeled by not only changes in risk factors, but also effects that are independent from the risk-factor changes.

Third, a recently published review showed discrepancies in effectiveness of SGLT2i in RCTs and real-world evidence (RWE). RCTs did not show preventive effects on major adverse cardiovascular events, while RWE did [24]. RCTs provide the best evidence for efficacy and causality, while RWE gives insights into effectiveness for target population. The question becomes how these discrepancies might affect the cost-effectiveness result.

Therefore, the current study explores the cost effectiveness of SGLT2i for a routine care population that reflects current Dutch reimbursement criteria (version 2022 [25]) and compares these individuals to populations that satisfy the selection criteria of the trials, considering RWE and hybrid treatment effects (i.e., both risk-factor level changes and effects that are independent from the risk-factor changes). To ensure the proper extrapolation, the health economic model, i.e., the Modeling Integrated Care for Diabetes based on Observational data (MICADO) model, will be validated over the trial follow-up periods.

Methods

We reported the economic evaluation following the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standard 2022 [26], and reported the model input and characteristics based on the Mount Hood Diabetes Challenge Network’s Checklist [27] to ensure the transparency of this simulation (Supplementary Appendix 1).

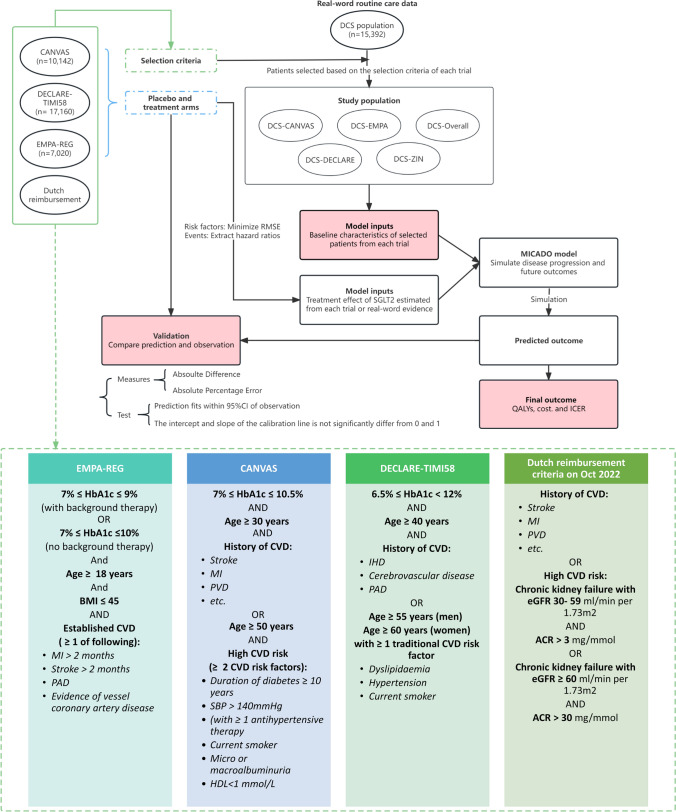

The flowchart overview of the study is presented in Fig. 1. The MICADO model [28–30], simulating the Dutch population of individuals with T2D, was used to evaluate the lifetime cost effectiveness of different scenarios. Scenarios were informed by real-world data from a Dutch routine care cohort [Hoorn Diabetes Care System (DCS)] [31] regarding patient characteristics, while information on the effectiveness of the medication was taken from the SGLT2i trials [32–34] and the review of RWE [24, 35]. For the effect on risk factors levels, the trajectories of treatment-induced differences of treatment compared with placebo over the follow-up time of the trial were extracted. For the effect on the incidence of complications, hazard ratios of complication incidences were extracted, and corrected for double counting within the model to capture only treatment effects unrelated to risk-factor level changes.

Fig. 1.

The flowchart of the study. We filtered the DCS population by the selection criteria of the respective SGLT2i trials or Dutch reimbursement criteria (full selection criteria are listed in Supplementary Appendix 2), and compared the baseline characteristics of filtered cohorts. The MICADO model uses the baseline characteristics of filtered cohorts and the treatment effects observed and estimated in each trial (i.e., CANVAS, DECLARE, and EMPA) to simulate the incidence and progression of complications, risk factor progression (i.e., the progression of HbA1c and cholesterol etc.), QALYs, and costs. For the filtered cohorts fulfilling the reimbursement criteria, the weighted average of all trials was used for the effectiveness and compared with using RWE-based treatment effect estimates [24]. The model was then validated for the placebo and treatment groups of the trials by investigating the model’s ability to predict the cumulative incidence of complications and relative risks between treatment and control groups over the trial follow-up time, using each trial’s filtered cohort. Finally, the cost effectiveness for each filtered group was calculated from lifetime simulations (40 years) of QALYs and costs. In summary, this study compared the baseline characteristics of trial-filtered routine care individuals, validated the MICADO model, and evaluated the cost effectiveness of SGLT2i for different routine care filtered cohorts. ACR albumin: creatinine ratio, CANVAS CANagliflozin cardioVascular Assessment Study, CI confidence interval, CVD cardiovascular disease, DECLARE Multicenter Trial to Evaluate the Effect of Dapagliflozin on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Events, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, EMPA Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patient, DCS The Hoorn Diabetes Care System, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, IHD ischemic heart disease, MI myocardial infarction, PAD peripheral arterial disease, PVD peripheral vascular disease, QALY quality-adjusted life year, RMSE root mean square error, SBP systolic blood pressure, SGLT2i sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors

Study Population

The DCS is a dynamic prospective cohort study of individuals with T2D treated by 103 general practitioners (GPs) in the West Friesland region of The Netherlands [31]. The DCS cohort started in 1998 with currently over 15,000 individuals with T2D. Detailed laboratory measurements have been described in previous studies [31]. The study has been approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Vrije Universiteit University Medical Center, Amsterdam. Written informed consent was obtained.

To analyze the generalizability of cost-effectiveness result and the impact of selection criteria, we filtered the DCS population (called DCS-Overall) by the selection criteria of the respective SGLT2i trials, including CANVAS [7], DECLARE-TIMI58 [8], EMPA-REG [6], and by the indication criteria of Dutch reimbursement criteria (version October 2022 [25]). This resulted in four DCS-based filtered cohorts, satisfying these selection criteria and called DCS-CANVAS, DCS-DECLARE, DCS-EMPA, and DCS-ZIN, respectively (selection process listed in Supplementary Appendix 2).

Statistical Analysis

We compared the baseline characteristics [e.g., age, HbA1c, body mass index (BMI), etc.] among the four filtered cohorts and the overall DCS population (DCS-CANVAS, DCS-EMPA, DCS-DECLARE, DCS-ZIN, and DCS-Overall) by chi-squared test and pairwise test, i.e., Games–Howell test with false discovery rate correction for multiple comparisons [36]. We also tested for differences in baseline characteristics between each trial-filtered DCS-based cohort and its corresponding trial cohort (based on risk factors’ mean and standard deviation in published evidence) by two-sample t tests. We omitted missing values because they were sufficiently low [37, 38] (1.41% on average and less than 5% observations for each variable were missing in DCS; see details in Supplementary Table 2.5).

The MICADO Diabetes Model

The MICADO diabetes model is a state-transition simulation model based on the multistate life table method using an annual cycle and based on the Dutch Chronic Disease model developed by the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment [28–30]. The MICADO model simulates microvascular complications (e.g., diabetic foot, nephropathy, and retinopathy) and macrovascular complications [e.g., acute myocardial infarction (AMI), cerebrovascular disease (CVA), and congestive heart failure (CHF)] in relation to their risk factors [e.g., category of age, sex, HbA1c, smoking status, BMI, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and total cholesterol]. The MICADO model has been validated both internally and externally [29, 39] and was cross validated in several Mount Hood Challenges [27, 40]. The current model is an update and revision of the 2010 version [29], which described the change of marginal distributions, whereas the current version of the model describes joint distributions.

Model Input and Outcomes

Key assumptions and inputs are presented in Table 1. Other input parameters including quality of life estimates and costs are listed in Supplementary Appendix 3. The baseline characteristics of each DCS-based cohort were entered into the MICADO model to predict future outcomes.

Table 1.

Key assumptions

| Required input | Input assumption |

|---|---|

| Target population and subgroups | Dutch routine care population qualified for reimbursement criteria of SGLT2i, and each of the three SGLT2i trials (CANVAS [7], DECLARE-TIMI58 [8], EMPA-REG [6]) |

| Setting and location | Dutch setting, located in The Netherlands |

| Study perspective | Third-party payer perspective |

| Interventions | SGLT2i (dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, and canagliflozin) |

| Comparators | Care-as-usual |

| Time horizon | 40 years [the median (quantiles) age of the DCS population is 67 (59–75), so 40 years is considered as lifetime] |

| Discount rate | Cost 4%; Effect 1.5% (according to Dutch guidelines [64]) |

| Choice of health outcomes |

Incidence of complications for validation QALY and cost for cost-effectiveness analysis |

| Currency, price date, and conversion | 2021 price level in euros |

| Choice of model | MICADO model [29] |

| Estimating resources and costs | Published evidence [15, 68–73] (details in Supplementary Table 3.1) |

| Intervention cost | €256.2 per patient per year (this cost of SGLT2i is sourced from local price lists [15, 74], in addition to the routine care costs of T2D [75]) |

| Disutility weights | Published evidence [76, 77] (details in Supplementary Table 3.1) |

| Treatment effects and algorithm |

Two aspects of treatment effects are considered: effects on risk factor values and on the incidence of complications Details are listed in Supplementary Appendix 4 For the effect on risk factors levels, the trajectory of treatment-induced differences of each treatment and placebo arm observed in CANVAS [7], DECLARE-TIMI58 [8], and EMPA-REG [6] over the follow-up time of trial were extracted by WebPlotDigitizer [78] for the risk factors, including HbA1c, SBP, BMI, and total cholesterol Treatment parameters were then calibrated towards the best-fit trajectory defined by the lowest root mean square error (RMSE; with a lower RMSE indicating a better fit) of treatment-induced differences between the model’s estimated trajectory and the observed trajectory over the respective trials’ follow-up time For the effect on the incidence of complications, hazard ratios of complication incidences were extracted from published evidence [32–34], and corrected for double counting within the model to capture only treatment effects unrelated to risk-factor level changes Trial-based treatment effect was estimated from three trials [32–34], and RWE-based treatment effect was extracted from a review [24] |

CANVAS CANagliflozin cardioVascular Assessment Study, DECLARE-TIMI58 Multicenter Trial to Evaluate the Effect of Dapagliflozin on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Events, EMPA-REG Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patient, RWE real-world evidence, SGLT2i sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, T2D type 2 diabetes, QALY quality-adjusted life years

Outcomes are the lifetime incidence of complications (e.g., AMI, CVA, and CHF), costs, QALYs, and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICERs). SGLT2i are considered cost effective if the ICER is less than the Dutch willingness-to-pay threshold of €20,000/QALY or €50,000/QALY when considering the burden of disease for diabetes using the proportional shortfall method [41, 42].

Model Validation

Model validation was performed by comparing MICADO predictions to observations of the cumulative incidences at the endpoint of each trial follow-up, that is, the “calibration-in-the-large” [43]. The differences between observed and predicted cumulative incidence were compared by two measures, including (1) absolute difference and (2) mean absolute percentage error (MAPE; the average of the error in percentage terms) [43]. MAPE is a relative measure, and values closer to zero indicate better accuracy [43]. We generated plots to visualize both predicted and observed cumulative incidence of events and relative risks of events in the treatment group as compared with the control group, and statistical validation was assessed by two methods, including (1) the prediction fits within the 95% confidence interval (CI) of observation [44] and (2) a non-significant test indicates good calibration, i.e., the deviation of the intercept and the slope of the calibration line (prediction against observation) from the ideal values of 0 and 1, respectively [45].

Scenario and Sensitivity Analyses

To account for different scenarios of diminishing treatment effects over time, for treatment effects estimated from both RCT and RWE, we evaluated four scenarios (see Supplementary Appendix 4), including (1) a base case scenario—assuming treatment effects diminish gradually over time (based on the estimated trajectory), (2) a worst-case scenario—assuming treatment effects diminish immediately after the trial period, (3) a best-case scenario—assuming treatment effects remain present relatively long (based on the longest estimated duration), and (4) a scenario ignoring all direct treatment effects on hazard ratios—that is, the treatment effect is only conveyed by risk-factor level changes and is assumed not to have an effect on disease incidences directly, reflecting the approach in the majority of published model-based evaluations [17].

A subgroup analysis for GP-practice was also considered; because not everyone who meets the reimbursement criteria will ultimately use SGLT2i, a subgroup of reimbursed population was defined based on current Dutch GP-practice to only prescribe SGLT2i to individuals with a remaining life expectancy of more than 5 years and an HbA1c larger than 7% or 53 mmol/mol [46].

Deterministic sensitivity analysis (DSA) was performed for RWE on the risk-factor level changes of HbA1c, cholesterol, SBP, and BMI, and on the cost of SGLT2i with ± 20% relative changes. Hazard ratios of cardiovascular events were varied using upper or lower bound value of their 95% CI. The results were summarized in a tornado diagram, ranking parameters from high to low according to their effect on the ICER.

Following publications calling for greater focus on short- and intermediate-term outcomes in economic evaluations [47], different time horizons from 1 year to 39 years were applied to investigate the impact of the time horizon.

All analyses were performed in R (version 4·1·0: https://www.r-project.org/) and R studio (version 1·4·1717: https://www.rstudio.com/).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Table 2, Supplementary Table 3.2, and Supplementary Figs. 3.1–3.3 show the baseline characteristics of the DCS populations filtered for each trial. We found that 8.17%, 36.98%, 2.67%, and 15.79% of the individuals in the DCS cohort meet the selection criteria of CANVAS, DECLARE-TIMI58, EMPA-REG, and Dutch reimbursement, respectively. When comparing the three trial-filtered cohorts, we found significant differences in the baseline characteristics of all risk factors, except LDL cholesterol (Supplementary Fig. 3.1). Comparing the reimbursement criteria-filtered cohort (DCS-ZIN) with the trial-filtered cohorts (Supplementary Fig. 3.2), the DCS-ZIN cohort had significantly lower HbA1c and higher age than the other three trial-filtered cohorts.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics

| DCS-CANVAS | DCS-DECLARE | DCS-EMPA | DCS-ZIN | DCS-Overall | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count (% overall)a | 998 (8.17) | 4517 (36.98) | 326 (2.67) | 1928 (15.79) | 12214 (100) | |

| Age, years | 66.17 (8.82) | 70.57 (8.64) | 69.13 (9.58) | 71.63 (9.61) | 66.02 (12.22) | < 0.001 |

| Duration of diabetes, years | 9.98 (7.49) | 8.68 (7.84) | 10.25 (7.02) | 10.16 (7.02) | 6.79 (7.17) | < 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/liter | 4.31 (1.03) | 4.36 (1.02) | 4.18 (0.96) | 4.29 (1.04) | 4.54 (1.09) | < 0.001 |

| HbA1c, % | 7.89 (0.81) | 7.40 (0.96) | 7.74 (0.69) | 6.87 (1.05) | 6.87 (1.18) | < 0.001 |

| HbA1c, mmol/mol | 62.77 (8.88) | 57.34 (10.50) | 61.13 (7.50) | 51.62 (11.48) | 51.60 (12.91) | < 0.001 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 81.78 (15.85) | 73.49 (18.71) | 73.90 (18.79) | 67.73 (19.92) | 78.04 (19.90) | < 0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 31.51 (5.57) | 30.23 (5.34) | 30.13 (4.65) | 29.92 (5.19) | 30.26 (5.57) | < 0.001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 149.79 (20.23) | 141.33 (18.26) | 145.43 (20.94) | 143.74 (22.62) | 140.60 (20.88) | < 0.001 |

| DBP, mmHg | 79.29 (10.19) | 77.71 (8.23) | 76.39 (10.02) | 76.35 (9.00) | 78.89 (8.78) | < 0.001 |

| Male, count (%) | 642 (64.3) | 2629 (58.2) | 226 (69.3) | 1199 (62.2) | 6549 (53.6) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking status, count (%) | < 0.001 | |||||

| Current | 326 (33.0) | 790 (17.8) | 64 (19.7) | 334 (17.5) | 2289 (19.1) | |

| Former | 406 (41.1) | 2224 (50.0) | 184 (56.6) | 1112 (58.1) | 5667 (47.3) | |

| Never | 257 (26.0) | 1436 (32.3) | 77 (23.7) | 468 (24.5) | 4022 (33.6) | |

| Using CVD medicationb, count (%) | 942 (94.4) | 4102 (90.9) | 318 (97.5) | 1879 (97.5) | 10017 (82.2) | < 0.001 |

| Using metformin, count (%) | 998 (100.0) | 3298 (73.0) | 247 (75.8) | 1347 (69.9) | 7860 (64.6) | < 0.001 |

| Using sulfonylureas, count (%) | 383 (38.4) | 1396 (30.9) | 158 (48.5) | 604 (31.3) | 2420 (19.9) | < 0.001 |

| Using insulin, count (%) | 384 (38.5) | 1439 (31.9) | 133 (40.8) | 677 (35.1) | 3034 (24.9) | < 0.001 |

| Previous AMI, count (%) | 81 (8.1) | 203 (4.5) | 122 (37.4) | 378 (19.6) | 378 (3.1) | < 0.001 |

| Previous CVA, count (%) | 72 (7.2) | 166 (3.7) | 89 (27.3) | 335 (17.4) | 335 (2.7) | < 0.001 |

| Previous CHF, count (%) | 33 (3.3) | 133 (2.9) | 51 (15.6) | 235 (12.2) | 235 (1.9) | < 0.001 |

DCS-CANVAS the subset of Hoorn Diabetes Care System cohort filtered by CANagliflozin cardioVascular Assessment Study [7], DCS-DECLARE the subset of Hoorn Diabetes Care System cohort filtered by Multicenter Trial to Evaluate the Effect of Dapagliflozin on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Events [8], DCS-EMPA the subset of Hoorn Diabetes Care System cohort filtered by Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patient [6], DCS-ZIN the subset of Hoorn Diabetes Care System cohort filtered by Dutch reimbursement criteria (version October 2022 [25]), DCS-Overall the overall Hoorn Diabetes Care System cohort, LDL low-density lipoprotein, HbA1c hemoglobin A1c, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, BMI body mass index, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, CVD cardiovascular disease, AMI acute myocardial infarction, CVA cerebrovascular accident, CHF chronic heart failure

Mean (one standard deviation) are presented unless otherwise stated

aThe proportion indicates the percentage to the DCS-Overall population, so it does not add up to 1

bCVD medication, cardiovascular disease medication including C02, C03A, C03B, C03E, C03DA, C07, C08, C09, C10, C01, C03, C04, C05, according to ATC code

Comparing each trial’s published baseline characteristics, we also found significant differences in the baseline characteristics between the filtered cohorts and original study populations (Supplementary Figs. 3.4–3.6). Filtered cohorts had a significantly higher baseline SBP and age but significantly lower HbA1c, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and BMI compared to their corresponding trials.

Model Validation

Figure 2 demonstrates a good alignment between the simulated and observed relative risks along a 45-degree perfect calibration line. In most cases, the simulation fell within the 95% confidence interval of the observation, indicating proper calibration. Overall, the weighted average bias was 1.90 and 2.05 per 1000 patient-years, and MAPE was around 20% for both the placebo and treatment arms (Supplementary Table 5.1). Of note, AMI was overestimated in both placebo and treatment arm with an average bias of 6.09 and 5.72 per 1000 patient-years, respectively (Supplementary Table 5.2). The calibration intercept and slope were not significantly different from 0 and 1 when excluding the estimation of AMI (Supplementary Fig. 5.1).

Fig. 2.

The validation of relative risks between treatment and control group. The black line at a 45-degree angle indicates perfect calibration, where the predictions match the simulations. Dashed grey line and ribbon indicate the calibration line with 95% confidence interval. The calibration line being closer to the 45-degree angle perfection calibration line indicates greater validation. Estimated equations and squared linear correlation coefficient of the calibration (R2) are listed in the top-left of both graphs. Point and error bar indicate the respective simulation and observation with its 95% confidence interval. More error bars crossing the perfect calibration line (i.e., the simulation is located within the 95% confidence interval of the observation) indicate greater validation. AMI acute myocardial infarction, CVA cerebrovascular disease, CHF congestive heart failure, CANVAS CANagliflozin cardioVascular Assessment Study, DECLARE Multicenter Trial to Evaluate the Effect of Dapagliflozin on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Events, EMPA Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patient

Scenario Analysis of Cost-effectiveness

Table 3 shows the cost-effectiveness results for DCS-filtered cohorts of SGLT2i compared with current standard of care. Risk-factor level changes for each scenario are presented in Supplementary Figs. 3.7–3.9. On average, the incremental QALY and cost of SGLT2i compared with care-as-usual is 1.36 and €7015, respectively. In all cases, SGLT2i were cost effective. Respectively, the ICER was €5382, €5001, and €7822 per QALY for CANVAS, DECLARE-TIMI58, and EMPA-REG in the base case.

Table 3.

Cost-effectiveness of each DCS sub-cohorts (in 2021, euro, Dutch unit costs, Dutch setting, 40 years)

| Scenario 1 (base case) | Scenario 2 (worst case) | Scenario 3 (best case) | Scenario 4 (no HR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial-based cohorts | ||||

| Canagliflozin (DCS-CANVAS) | ||||

| ∆QALY | 1.07 | 0.50 | 1.58 | 0.33 |

| ∆Cost | 5735 | 2330 | 10,057 | 1324 |

| ICER | 5382 | 4630 | 6376 | 3987 |

| Dapagliflozin (DCS-DECLARE) | ||||

| ∆QALY | 0.94 | 0.36 | 2.03 | 0.24 |

| ∆Cost | 4720 | 1980 | 12,298 | 1583 |

| ICER | 5001 | 5454 | 6045 | 6476 |

| Empagliflozin (DCS-EMPA) | ||||

| ∆QALY | 1.04 | 0.50 | 1.21 | 0.20 |

| ∆Cost | 8150 | 3884 | 9529 | 1505 |

| ICER | 7822 | 7782 | 7859 | 7538 |

| Reimbursed cohort (DCS-ZIN) | ||||

| Canagliflozin | ||||

| ∆QALY | 1.13 | 0.44 | 2.00 | 0.16 |

| ∆Cost | 6226 | 3003 | 12,404 | 1796 |

| ICER | 5495 | 6779 | 6192 | 11,509 |

| Dapagliflozin | ||||

| ∆QALY | 0.99 | 0.29 | 2.31 | 0.14 |

| ∆Cost | 5410 | 2371 | 13,880 | 1788 |

| ICER | 5476 | 8229 | 6007 | 12,839 |

| Empagliflozin | ||||

| ∆QALY | 1.26 | 0.53 | 1.50 | 0.16 |

| ∆Cost | 6698 | 3413 | 7838 | 1776 |

| ICER | 5320 | 6447 | 5228 | 11,303 |

| Weighted average of trials | ||||

| ∆QALY | 0.96 | 0.35 | 1.72 | 0.15 |

| ∆Cost | 5235 | 2591 | 10,089 | 1814 |

| ICER | 5440 | 7411 | 5870 | 11,902 |

| RWE of SGLT2i | ||||

| ∆QALY | 2.69 | 0.91 | 3.84 | 0.15 |

| ∆Cost | 13,124 | 4908 | 19,960 | 1814 |

| ICER | 4873 | 5390 | 5196 | 11,902 |

| For potential users in GP practice (using treatment effect from weighted average of trials) | ||||

| ∆QALY | 1.06 | 0.43 | 1.54 | 0.26 |

| ∆Cost | 4796 | 2221 | 7425 | 1591 |

| ICER | 4530 | 5190 | 4818 | 6035 |

| For potential users in GP practice (using treatment effect from RWE) | ||||

| ∆QALY | 2.45 | 0.85 | 3.65 | 0.26 |

| ∆Cost | 10,053 | 3742 | 16,699 | 1591 |

| ICER | 4098 | 4421 | 4577 | 6035 |

∆QALY incremental quality adjusted life years comparing SGLT2i to care-as-usual, ∆Cost incremental costs comparing SGLT2i to care-as-usual, DCS-CANVAS the subset of Hoorn Diabetes Care System cohort filtered by CANagliflozin cardioVascular Assessment Study [7], DCS-DECLARE the subset of Hoorn Diabetes Care System cohort filtered by Multicenter Trial to Evaluate the Effect of Dapagliflozin on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Events [8], DCS-EMPA the subset of Hoorn Diabetes Care System cohort filtered by Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patient [6], DCS-ZIN the subset of Hoorn Diabetes Care System cohort filtered by Dutch reimbursement criteria (version October 2022 [25]), GP general practitioner, HR hazard ratios, ICER incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, RWE real-world evidence, SGLT2i sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors

On average, individuals who qualified for the Dutch reimbursement criteria of SGLT2i showed on average a 11% higher QALY gain and a 7% lower ICER than the trial-filtered cohorts. For reimbursed individuals, the ICER was €5440/QALY using the trial-weighted average effectiveness, or €5495/QALY for canagliflozin (CANVAS), €5476/QALY for dapagliflozin (DECLARE-TIMI58), and €5320/ QALY for empagliflozin (EMPA-REG), respectively. Of note, using RWE-based effectiveness estimates resulted in the lowest ICER (€4873/QALY), since the effects were largest.

The ICER of worst-case (i.e., immediately diminish treatment effect) and best-case scenarios (i.e., long-last treatment effect) did not substantially differ from the base case (less than 20% difference on both sides on average). Not incorporating hazard ratios of events (scenario 4) estimated an average of 41% higher ICER. Nevertheless, SGLT2i remained cost effective. The subgroup analysis with reimbursed individuals who might prescribe SGLT2i based on GP practice resulted in lower ICER (€4530/QALY for trial-weighted average and €4098/QALY for RWE) than the general reimbursement.

Sensitivity Analysis of Cost Effectiveness

Supplementary Fig. 5.2 presents the tornado diagram (95% CI or ± 20% of input values) and the line graph of cost effectiveness for multiple time horizons as the DSA results. Drug cost had the most significant impact on the ICER estimation. In both the tornado diagram and line graph, all ICERs remained under the €20,000/QALY threshold. Thus, our conclusion that SGLT2i are cost effective compared with care-as-usual for the Dutch routine care population is robust for all parameters’ estimates. This conclusion holds not only in the period of a lifetime, but also in the short term (e.g., 5 years) and intermediate term (e.g., 10 years).

Discussion

Although the reimbursement criteria resulted in a target group with significantly different characteristics than the populations used in the clinical trials, SGLT2i could be considered cost effective at €5440/QALY, using effectiveness estimates from RCTs, from a third-party payer perspective using a lifetime horizon. Results were robust in various sensitivity analyses.

Inclusion criteria were strictest in the EMPA-REG trial, requiring established ASCVD individuals and representing only 3% of the Dutch diabetes population. This proportion is lower compared with previous findings [18], mainly because DCS is a well-managed diabetes routine care cohort with extra annual assessments of diabetes-related risk factors following the Dutch College of GP’s treatment guidelines (e.g., targeting HbA1c < 7%), while the trial excluded individuals with HbA1c < 7%. The inclusion criteria are broader in the CANVAS trial, allowing the inclusion of individuals with high cardiovascular risk (indicated by past events) and representing 8% of the Dutch routine care population. DECLARE-TIMI58 has the broadest criteria, allowing the inclusion of individuals with multiple risk factors for cardiovascular disease (e.g., dyslipidemia, hypertension, and tobacco use) and representing 37% of the Dutch routine care population. This confirms the previous finding that the DECLARE-TIMI58 trial had the largest representation of general T2D individuals in The Netherlands [18], compared with the other two trials. The current Dutch reimbursement criteria allow individuals with high cardiovascular risk (indicated by past events and eGFR) and resulted in qualifying 16% of individuals in routine care and as such seems in between DECLARE-TIMI58 and CANVAS.

Even when the same selection criteria were used, we found significant differences in the baseline characteristics between trial-filtered routine care cohorts and trial study populations. Routine care practice, as reflected in the (centrally organized) DCS cohort, tends to perform better in the management of HbA1c and BMI at baseline compared with trials, despite an older population, supporting the fact that trials frequently exclude older individuals [48]. We found QALY gains were higher and ICERs were lower for the older DCS-ZIN population than for the trial-filtered cohorts, offering economic support of a previous claim that SGLT2i are good therapeutic options for older individuals with diabetes [49].

Differences in baseline characteristics partly explain the discrepancies we found in ICERs compared with previously published evidence (e.g., €5476/QALY and €5502/QALY for dapagliflozin in our study and published evidence [50], respectively, both in a Dutch setting). Although a similar cost-effectiveness conclusion was found, our study indicated that using baseline characteristics of the patient cohort who qualified for the reimbursement criteria in routine care might estimate an average of 7% lower ICER compared with trial-filtered cohort. This finding deserves further attention when conducting economic evaluation for reimbursement purposes, not only for SGLT2i, but also for other new drugs which apply trial evidence for a target reimbursement audience [51]. Decision makers need to be aware of this difference between trial-based and reimbursement-based cost effectiveness for price negotiation.

In 2007, the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research Real-World Data Task Force published a statement supporting the use of RWE for coverage and reimbursement decision-making [52]. However, the majority of the current cost-effectiveness analysis of SGLT2i has been developed on the basis of RCT rather than RWE, due to the lack of real-world effectiveness evidence [16]. Also for SGLT2i, evidence on effectiveness in RWE is rare, with only two reviews on RWE [35, 53] having been identified in an umbrella review published in 2022 [24]. In those two reviews on RWE, 14 studies (3,157,259 patients) and 8 studies (1,536,339 patients) were included, respectively. This scarce RWE seemed to show a greater benefit of SGLT2i than RCT [24, 35, 54], which explains our finding that incorporating RWE leads to greater health benefit and cost effectiveness (i.e., 156% higher QALY gains and 10% lower ICER in the base case). However, these results should be interpreted with caution. It may seem counterintuitive to find RWE performing better than RCT. One explanation is that although propensity scores analytic approaches are extensively used in RWE studies to form comparable groups, they cannot eliminate the possible effect of confounding due to uncontrolled and unmeasured factors [24]. For example, possibly in RWE, only individuals with a good prognosis received the treatment and as a result treatment effects evaluated in RWE were larger than the RCT effects [54]. Our subgroup analysis of individuals with a good prognosis—defined as those with a remaining life expectancy of more than 5 years and an HbA1c greater than 7% according to current Dutch GP practice [46]—supports this finding. We found that SGLT2i provided greater health benefits (i.e., 18% higher incremental QALY on average for all scenarios) for individuals with good prognosis than for those who were reimbursed in general. These results may suggest that the observed benefit in RWE may be partially attributed to selection bias.

The cost-effective conclusion is nevertheless robust to all scenarios and sensitivity analysis. We found drug cost has the largest influence on the ICER of SGLT2i, which is consistent with a previous finding [55]. The inflation of drug cost over time or renegotiation of drug prices might change the conclusion on the cost effectiveness, but as long as the annual price is lower than €4105 in the real-word setting (Supplementary Fig. 5.3), our conclusion, i.e., SGLT2i are cost effective, will not be affected.

Previously published model-based cost-effectiveness analyses of SGLT2i mainly applied patient-level simulation models [56], such as the IQVIA/CORE model [57] and UKPDS-OM2 [19]. Our study indicated that the MICADO model, as a cohort-level model, also effectively simulated the placebo and treatment arm of SGLT2i in EMPA-REG, CANVAS, and DECLARE-TIMI58 and predicted their beneficial effect (e.g., reduced CHF). Specifically, the MICADO model overestimated the incidence of AMI, but it showed a good fit for CVA and CHF, confirming the results of its previous validation research [39].

Only a few cost-effectiveness analyses or diabetes models have incorporated direct evidence (e.g., hazard ratios) of treatment effects on event rates [17]. Most analyses modeled treatment effects only through risk-factor level changes (e.g., HbA1c and BMI) [17]. Our study used a hybrid approach to capture benefits that might be independent of changes in HbA1c and other risk factors. We found that treatment scenarios without incorporating hazard ratios in either RWE or RCT might lead to an ICER that is on average 41% higher compared with the base case. This finding highlights the necessity of incorporating hazard ratios for future decision-makers or modelers, especially regarding treatments that show a special ability to reduce cardiovascular risk.

The cost-effectiveness analysis of SGLT2i in a real-world setting is important, because SGLT2i have been proven to be potential preferred agents for T2D owing to their cardiovascular and renal benefit. However, SGLT2i are underused in current routine practice in many countries, including The Netherlands [55, 58, 59], partly due to their high cost and lack of RWE [55]. Our findings confirmed that SGLT2i were cost effective compared with care-as-usual in routine care individuals, which is consistent with earlier papers [16, 55]. However, we applied real-world reimbursement criteria, evaluated the lifetime outcomes of a routine care cohort, and attempted to incorporate RWE to the greatest extent. Moreover, Yoshida’s and Rahman’s reviews indicated that the majority of studies were conducted in a UK or US settings, and only one study evaluated the cost effectiveness of adding dapagliflozin to insulin in The Netherlands [16, 50, 55]. Our study filled the knowledge gap in the cost effectiveness of adding SGLT2i compared with care-as-usual in The Netherlands by focusing on the Dutch routine care cohort based on the Dutch model. Considering the Dutch population’s characteristics are more similar to those of other European populations, such as higher average age [60] and SBP [61] and milder obesity [62] than USA and UK, our study might provide cost-effectiveness evidence that is more generalizable to European countries.

There are several limitations to the current study. First, our study attempted to include RWE, but the evidence is scarce and insufficient (e.g., lack of details of risk factors trajectory). The larger effectiveness observed in the RWE than in the RCT was somewhat surprising. We evaluated one possible cause, i.e., treatment indication on good prognosis, in a subgroup analysis, but these findings might also be caused by publication bias or lower quantity and quality of RWE-based studies [24]. The accuracy of cost-effectiveness analysis using RWE is therefore limited. Rather than referencing previous publications, future studies could evaluate RWE-based treatment effects when more SGLT2i users and follow-up data are available (only 0.3% users in DCS until 2019). Second, we omitted some inclusion and exclusion criteria for filtering because of a lack of information (e.g., pregnancy). This likely did not affect our results, since we included the most important risk factors stratifying diabetes individuals, such as HbA1c and cardiovascular risks. Third, the potential side effects of SGLT2i, e.g., ketoacidosis, genital infection, and volume depletion, etc. [63], and the possibility that individuals stop taking SGLT2i when side effects occur, were not considered because the MICADO model did not include the corresponding relevant health states. This might lead to an underestimation of ICER; however, individuals that stop taking SGLT2i will no longer have costs and hence this will not affect the ICER to a large degree. Furthermore, our study utilized a third-party payer perspective, despite the Dutch guideline recommending a societal perspective [64]. Since we did not consider the impact of side effects, the only additional relevant outcome and costs would be gains in work productivity. These potential gains would result in additional savings, and therefore, the chosen perspective does not influence our conclusion that SGLT2i were cost effective. Fourth, we assumed treatment effects were the same in the reimbursement cohort as observed in RWE or RCTs, and this might be biased because we found significant differences in baseline characteristics between trial-filtered DCS cohorts and original trial cohorts. However, we aimed to compare the difference in ICER between trial-alike and reimburse-alike populations for Dutch diabetes individuals, and the best estimator of treatment effects for a trial-alike population is the trial-based effectiveness. Previous studies [2, 65] could be referred to if trial-based cost effectiveness (i.e., same baseline characteristics as trials) is of interest. Furthermore, we did not include probabilistic sensitivity analysis due to the unavailability of model parameters’ distribution, especially regarding the prevalence and incidence of diabetes events and their risks and computational burden. Our current study was not designed to support specific decision making, but rather to compare current Dutch reimbursement criteria with trial populations and considering the influence of RWE. Previous studies [2, 5, 66, 67] have already shown, more elaborately, the decision uncertainty regarding the cost effectiveness of SGLT2i compared with usual care. It is worth noting that these studies often consider probabilistic sensitivity analysis by assuming that cost parameters follow a gamma distribution and utility parameters follow a beta distribution [2, 5]. However, they may leave out some other important model parameters, such as the incidence of events, in their probabilistic sensitivity analysis [2, 5]. Finally, the current version of MICADO model could not directly capture the renal benefits of SGLT2i. However, via effects on HbA1c some of these effects have been included. Hence, we might somewhat underestimate the incremental QALYs and cost savings. Nevertheless, this limitation does not impact our conclusion that SGLT2i are cost effective.

Conclusions

The MICADO model developed from Dutch general practice registries is capable of capturing and predicting the benefit of SGLT2i with satisfactory accuracy. The Dutch reimbursement criteria for SGLT2i will result in a target group, which tends to be older, but with better controlled HbA1c and BMI than trial populations. SGLT2i can be considered cost effective in a routine care population in The Netherlands, reflecting current Dutch reimbursement criteria.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge all the Hoorn Diabetes Care System participants and all personnel at the Amsterdam University Medical Center who have helped with its creation and maintenance. The authors thank Sajad Emamipour MSc, Stefan R.A. Konings MSc, and Fang Li MSc for their scientific advice.

The current version of MICADO model and its results have been presented at Mount Hood Challenge 2022. We thank the Mount Hood organizers for the arrangement and allowing us to participate in the validation challenges.

Declarations

Funding

The Modelling Integrated Care for Diabetes based on Observational data (MICADO) model was originally developed within Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu (RIVM; The Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment), and main developers were Rudolf Hoogenveen from RIVM and Amber Van Der Heijden from Amsterdam University Medical Center, funded by ZonMw (The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development). The further development of the MICADO model was funded by Zorginstituut Nederland (The Netherlands National Health Care Institute). ZonMw had no role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, the preparation, review, or approval of the article, and the decision to submit the article for publication. Mohamed El Alili and Saskia Knies are employees of Zorginstituut Nederland, and as such Zorginstituut Nederland was involved via their coauthorships. The article reflects the opinion of the authors and not necessarily of their employers.

Conflict of Interest/Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Availability of Data and Material

All data analyzed during this work are from VU University Medical Center (VUmc), Amsterdam. The data are not publicly available, but can be requested from VUmc. The MICADO model used during this work is from ZonMw (The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development) and Zorginstituut Nederland (The Netherlands National Health Care Institute). The model is not publicly available, but can be requested from authors.

Code Availability

All analysis was performed in R 4.1.0, and is available on request from authors.

Ethics Approval

This was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the VUmc.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for Publication

This is not a case study analysis, and the information has been anonymized; therefore, consent for publication is not applicable.

Author Contributions

XL, RH, MA, SK, JW, JB, PE, GN, AG, and TF were involved in various aspects of this study. XL, RH, SK, AG, and TF were involved in the conception and design. XL, RH, MA, JW, PE, and GN were involved in data acquisition. XL, RH, MA, JW, JB, and PE were involved in the analysis and interpretation of data. XL and MA were involved in drafting the manuscript. XL, MA, SK, JB, PE, and GN were involved in critical revisions for important intellectual content. XL, RH, and JW were involved in statistical analysis. XL, RH, JW, and AG were involved in the development of the MICADO model. SK and TF were involved in acquiring funding for the project. MA, SK, JB, PE, GN, AG, and TF were involved in project supervision. All authors contributed to revising and approving the manuscript. XL and TF are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th edition. 25th May 2022]; https://diabetesatlas.org/atlas/tenth-edition/?dlmodal=active&dlsrc=https%3A%2F%2Fdiabetesatlas.org%2Fidfawp%2Fresource-files%2F2021%2F07%2FIDF_Atlas_10th_Edition_2021.pdf. Accessed 7 Jun 2023.

- 2.Gourzoulidis G, Tzanetakos C, Ioannidis I, Tsapas A, Kourlaba G, Papageorgiou G, et al. Cost-effectiveness of empagliflozin for the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus at increased cardiovascular risk in Greece. Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38(5):417–426. doi: 10.1007/s40261-018-0620-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez JM, Macomson B, Ektare V, Patel D, Botteman M. Evaluating drug cost per response with SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(6):309–318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assoc AD. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(4):1033–1046. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaku K, Haneda M, Sakamaki H, Yasui A, Murata T, Ustyugova A, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of empagliflozin in japan based on results from the asian subpopulation in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME Trial. Clin Ther. 2019;41(10):2021–2040. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ingelheim B. BI 10773 (Empagliflozin) Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients (EMPA-REG OUTCOME). [cited 2023 7 June]; Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01131676?cond=EMPA-REG&draw=2&rank=1.

- 7.Janssen Research & Development L. CANVAS - CANagliflozin cardioVascular Assessment Study (CANVAS). [cited 2022 26th April]; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01032629?cond=CANVAS&draw=2

- 8.AstraZeneca. Multicenter Trial to Evaluate the Effect of Dapagliflozin on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Events (DECLARE-TIMI58). [cited 2022 26th April]; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01730534

- 9.Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, Im K, Goodrich EL, Bonaca MP, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet. 2019;393(10166):31–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32590-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma S, McMurray JJV. SGLT2 inhibitors and mechanisms of cardiovascular benefit: a state-of-the-art review. Diabetologia. 2018;61(10):2108–2117. doi: 10.1007/s00125-018-4670-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Excellence NIfHaC. Canagliflozin, dapagliflozin and empagliflozin as monotherapies for type 2 diabetes (TA390). 2016.

- 12.Heerspink HJL, Perkins BA, Fitchett DH, Husain M, Cherney DZI. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in the treatment of diabetes mellitus: Cardiovascular and kidney effects, potential mechanisms, and clinical applications. Circulation. 2016;134(10):752–772. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Draznin B, Aroda VR, Bakris G, Benson G, Brown FM, American Diabetes Association Professional Practice C et al. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(Suppl 1):S125–S143. doi: 10.2337/dc22-S009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, Bailey CJ, Ceriello A, Delgado V, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(2):255–323. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.GIPdatabank.nl. GIPdatabank.nl. [cited 2022 26th April]; A10BK Natriumglucose-cotransporter-2-remmers (sglt-2-remmers)]. https://www.gipdatabank.nl/databank?infotype=g&label=00-totaal&tabel=B_01-basis&geg=vg_gebr&item=A10B.

- 16.Rahman W, Solinsky PJ, Munir KM, Lamos EM. Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of sodium-glucose transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin Pharmaco. 2019;20(2):151–161. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2018.1543408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McEwan P, Bennett H, Khunti K, Wilding J, Edmonds C, Thuresson M, et al. Assessing the cost-effectiveness of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A comprehensive economic evaluation using clinical trial and real-world evidence. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22(12):2364–2374. doi: 10.1111/dom.14162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birkeland KI, Bodegard J, Norhammar A, Kuiper JG, Georgiado E, Beekman-Hendriks WL, et al. How representative of a general type 2 diabetes population are patients included in cardiovascular outcome trials with SGLT2 inhibitors? A large European observational study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21(4):968–974. doi: 10.1111/dom.13612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayes AJ, Leal J, Gray AM, Holman RR, Clarke PM. UKPDS outcomes model 2: a new version of a model to simulate lifetime health outcomes of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus using data from the 30 year United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study: UKPDS 82. Diabetologia. 2013;56(9):1925–1933. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2940-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Brindle P. Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2017;23(357):j2099. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ali A, Bain S, Hicks D, Jones PN, Patel DC, Evans M, et al. SGLT2 Inhibitors: cardiovascular benefits beyond HbA1c-translating evidence into practice (vol 10, pg 1595, 2019) Diabetes Ther. 2019;10(5):1623–1624. doi: 10.1007/s13300-019-0670-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mcewan P, Foos V, Bennett H, Kartman B, Edmonds C, Gause-Nilsson IA. Assessing the performance of cardiovascular risk equations in the DECLARE-TIMI 58 population. Diabetes. 2019;1:68. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mcewan P, Foos V, Bennett H, Kartman B, Edmonds C, Gause-Nilsson IA. Assessing the performance of the ukpds 82 risk equations to predict cardiovascular events in the DECLARE-TIMI 58 Trial population. Diabetes. 2019;1:68. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seo B, Su J, Song Y. Exploring heterogeneities of cardiovascular efficacy and effectiveness of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes: an umbrella review of evidence from randomized clinical trials versus real-world observational studies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;78(8):1205–1216. doi: 10.1007/s00228-022-03327-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nederland Z. Zorginstituut Nederland. [cited 2022 10th July]; https://english.zorginstituutnederland.nl/publications/reports/2021/06/22/gvs-advice-sglt-2-inhibitors. Accessed 7 Jun 2023.

- 26.Husereau D, Drummond M, Augustovski F, de Bekker-Grob E, Briggs AH, Carswell C, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) Statement: Updated reporting guidance for health economic evaluations. Pharmacoeconomics. 2022;40(6):601–609. doi: 10.1007/s40273-021-01112-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer AJ, Si L, Tew M, Hua XY, Willis MS, Asseburg C, et al. Computer modeling of diabetes and its transparency: A report on the eighth mount hood challenge. Value Health. 2018;21(6):724–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barendregt JJ, Van Oortmarssen GJ, Van Hout BA, Van Den Bosch JM, Bonneux L. Coping with multiple morbidity in a life table. Math Popul Stud. 1998;7(1):29–49. doi: 10.1080/08898489809525445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Heijden AA, Feenstra TL, Hoogenveen RT, Niessen LW, de Bruijne MC, Dekker JM, et al. Policy evaluation in diabetes prevention and treatment using a population-based macro simulation model: the MICADO model. Diabet Med. 2015;32(12):1580–1587. doi: 10.1111/dme.12811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoogenveen RT, van Baal PHM, Boshuizen HC. Chronic disease projections in heterogeneous ageing populations: approximating multi-state models of joint distributions by modelling marginal distributions. Math Med Biol. 2010;27(1):1–19. doi: 10.1093/imammb/dqp014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Der Heijden AA, Rauh SP, Dekker JM, Beulens JW, Elders P, M‘t Hart L, et al. The Hoorn Diabetes Care System (DCS) cohort. A prospective cohort of persons with type 2 diabetes treated in primary care in the Netherlands. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e015599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, Hantel S, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. New Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117–2128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, Mosenzon O, Kato ET, Cahn A, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(4):347–357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, de Zeeuw D, Fulcher G, Erondu N, et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(7):644–657. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li CX, Liang S, Gao LY, Liu H. Cardiovascular outcomes associated with SGLT-2 inhibitors versus other glucose-lowering drugs in patients with type 2 diabetes: A real-world systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2021;16(2):e0244689. 10.1371/journal.pone.0244689. PMID: 33606705; PMCID: PMC7895346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Lee S, Lee DK. What is the proper way to apply the multiple comparison test? Korean J Anesthesiol. 2018;71(5):353–360. doi: 10.4097/kja.d.18.00242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White IR, Carlin JB. Bias and efficiency of multiple imputation compared with complete-case analysis for missing covariate values. Stat Med. 2010;29(28):2920–2931. doi: 10.1002/sim.3944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eekhout I, de Vet HCW, Twisk JWR, Brand JPL, de Boer MR, Heymans MW. Missing data in a multi-item instrument were best handled by multiple imputation at the item score level. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(3):335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emamipour S, Pagano E, Di Cuonzo D, Konings SRA, van der Heijden AA, Elders P, et al. The transferability and validity of a population-level simulation model for the economic evaluation of interventions in diabetes: the MICADO model. Acta Diabetol. 2022;59(7):949–957. 10.1007/s00592-022-01891-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Tew M, Willis M, Asseburg C, Bennett H, Brennan A, Feenstra T, et al. Exploring structural uncertainty and impact of health state utility values on lifetime outcomes in diabetes economic simulation models: Findings from the ninth mount hood diabetes quality-of-life challenge. Med Decis Making. 2022;42(5):599–611. doi: 10.1177/0272989X211065479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emamipour S, van Dijk PR, Bilo HJG, Edens MA, van der Galiën O, Postma MJ, et al. Personalizing the use of a intermittently scanned continuous glucose monitoring (isCGM) device in individuals with type 1 diabetes: a cost-effectiveness perspective in the netherlands (FLARE-NL 9). J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2022. 10.1177/19322968221109841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Cost-effectiveness in practice. 2015 [cited 2023 26th Jan]; https://www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/publicaties/rapport/2015/06/26/kosteneffectiviteit-in-de-praktijk. Accessed 7 Jun 2023.

- 43.Pagano E, Konings SRA, Di Cuonzo D, Rosato R, Bruno G, van der Heijden AA, et al. Prediction of mortality and major cardiovascular complications in type 2 diabetes: external validation of UK Prospective Diabetes Study outcomes model version 2 in two European observational cohorts. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(5):1084–1091. doi: 10.1111/dom.14311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rothman KJ. Epidemiology: an introduction. Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stevens RJ, Poppe KK. Validation of clinical prediction models: what does the “calibration slope” really measure? J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;118:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.NHG-werkgroep: Barents ESE BH, Bouma M, Dankers M, De Rooij A, Hart HE, Houweling ST, IJzerman RG, Janssen PGH, Kerssen A, Oud M, Palmen J, Van den Brink-Muinen A, Van den Donk M, Verburg-Oorthuizen AFE, Wiersma Tj. Diabetes mellitus type 2. [cited 2023 10 Jan]; https://richtlijnen.nhg.org/standaarden/diabetes-mellitus-type-2. Accessed 7 Jun 2023.

- 47.Asche CV, Hippler SE, Eurich DT. Review of models used in economic analyses of new oral treatments for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(1):15–27. doi: 10.1007/s40273-013-0117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blonde L, Khunti K, Harris SB, Meizinger C, Skolnik NS. Interpretation and impact of real-world clinical data for the practicing clinician. Adv Ther. 2018;35(11):1763–1774. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0805-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Custodio JS, Roriz J, Cavalcanti CAJ, Martins A, Salles JEN. Use of SGLT2 inhibitors in older adults: Scientific evidence and practical aspects. Drugs Aging. 2020;37(6):399–409. doi: 10.1007/s40266-020-00757-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Haalen HG, Pompen M, Bergenheim K, McEwan P, Townsend R, Roudaut M. Cost effectiveness of adding dapagliflozin to insulin for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Netherlands. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34(2):135–146. doi: 10.1007/s40261-013-0155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Nooten F, Holmstrom S, Green J, Wiklund I, Odeyemi IAO, Wilcox TK. Health economics and outcomes research wiihin drug development challenges and opportunities for reimbursement and market access within biopharma research. Drug Discov Today. 2012;17(11–12):615–622. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garrison LP, Neumann PJ, Erickson P, Marshall D, Mullins D. Using real-world data for coverage and payment decisions: The ISPOR real-world data task force report. Value Health. 2007;10(5):326–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singh AK, Singh R. Heart failure hospitalization with SGLT-2 inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled and observational studies. Expert Rev Clin Phar. 2019;12(4):299–308. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2019.1588110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palmer SC, Tendal B, Mustafa RA, Vandvik PO, Li SY, Hao QK, et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter protein-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists for type 2 diabetes: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2021;13:372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshida Y, Cheng X, Shao H, Fonseca VA, Shi L. A Systematic review of cost-effectiveness of sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibitors for type 2 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2020;20(4):1–19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Hong DZ, Si L, Jiang MH, Shao H, Ming WK, Zhao YN, et al. Cost effectiveness of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors: A systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(6):777–818. doi: 10.1007/s40273-019-00774-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Palmer AJ, Roze S, Valentine WJ, Minshall ME, Foos V, Lurati FM, et al. The CORE Diabetes Model: Projecting long-term clinical outcomes, costs and cost-effectiveness of interventions in diabetes mellitus (types 1 and 2) to support clinical and reimbursement decision-making. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20(Suppl 1):S5–26. doi: 10.1185/030079904X1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martens P, Janssens J, Ramaekers J, Dupont M, Mullens W. Contemporary choice of glucose lowering agents in heart failure patients with type 2 diabetes. Acta Cardiol. 2020;75(3):211–217. doi: 10.1080/00015385.2019.1569313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van der Linden N, Van Olst S, Nekeman S, Uyl-de Groot CA. The cost-effectiveness of dapagliflozin compared to DPP-4 inhibitors in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Netherlands. Diabet Med. 2021;38(4):e14371. 10.1111/dme.14371. PMID: 32745279; PMCID: PMC8048925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.WorldData.info. The average age in global comparison. 2022 [cited 2022 24th Aug]; https://www.worlddata.info/average-age.php. Accessed 7 Jun 2023.

- 61.Zhou B, Perel P, Mensah GA, Ezzati M. Global epidemiology, health burden and effective interventions for elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18(11):785–802. doi: 10.1038/s41569-021-00559-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Federation WO. Global Obesity Observatory Ranking. 2022 [cited 2022 24th Aug]; https://data.worldobesity.org/rankings/. Accessed 7 Jun 2023.

- 63.Qiu M, Ding LL, Zhang M, Zhou HR. Safety of four SGLT2 inhibitors in three chronic diseases: A meta-analysis of large randomized trials of SGLT2 inhibitors. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2021;18(2):14791641211011016. 10.1177/14791641211011016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Nederland Z. Guideline for economic evaluations in healthcare.[cited 2023 7 Jun 2023]; Available from: https://english.zorginstituutnederland.nl/publications/reports/2016/06/16/guideline-for-economic-evaluations-in-healthcare.

- 65.Kansal A, Reifsnider OS, Proskorovsky I, Zheng Y, Pfarr E, George JT, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of empagliflozin treatment in people with Type 2 diabetes and established cardiovascular disease in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial. Diabet Med. 2019;36(11):1494–1502. doi: 10.1111/dme.14076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nguyen E, Coleman CI, Nair S, Weeda ER. Cost-utility of empagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk. J Diabetes Complications. 2018;32(2):210–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cai X, Shi L, Yang W, Gu S, Chen Y, Nie L, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of dapagliflozin treatment versus metformin treatment in Chinese population with type 2 diabetes. J Med Econ. 2019;22(4):336–343. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2019.1570220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Struijs J, Mohnen S, Molema C, De Jong-van Til J, Baan C. Effects of bundled payment on curative health care costs in the Netherlands: an analysis for diabetes care and vascular risk management based on nationwide claim data, 2007-2010. 2012.

- 69.RIVM. Cost of Illness in the Netherlands. 2017 [cited 2022 21 Sep 2022]; https://statline.rivm.nl/#/RIVM/nl/dataset/50050NED/table?ts=1663785159573. Accessed 7 Jun 2023.

- 70.Emamipour S, van der Heijden AAWA, Nijpels G, Elders P, Beulens JWJ, Postma MJ, et al. A personalised screening strategy for diabetic retinopathy: a cost-effectiveness perspective. Diabetologia. 2020;63(11):2452–2461. doi: 10.1007/s00125-020-05239-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.OPENDISDATA. 2021 [cited 2022 21 Sep 2022]; https://opendisdata.nl/. Accessed 7 Jun 2023.

- 72.Romero-Aroca P, de la Riva-Fernandez S, Valls-Mateu A, Sagarra-Alamo R, Moreno-Ribas A, Soler N. Changes observed in diabetic retinopathy: eight-year follow-up of a Spanish population. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100(10):1366–1371. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mohnen SM, van Oosten MJM, Los J, Leegte MJH, Jager KJ, Hemmelder MH, et al. Healthcare costs of patients on different renal replacement modalities—analysis of Dutch health insurance claims data. PloS One. 2019;14(8):e0220800. 10.1371/journal.pone.0220800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Nederland Z. Medicijnkosten.nl. [cited 2022 22 Sep 2022];

- 75.Baan C, Bos G, Jacobs-van der Bruggen M. Modeling chronic diseases: the diabetes module. Justification of (new) input data. RIVM rapport 260801001. 2005.

- 76.Janssen LMM, Hiligsmann M, Elissen AMJ, Joore MA, Schaper NC, Bosma JHA, et al. Burden of disease of type 2 diabetes mellitus: cost of illness and quality of life estimated using the Maastricht Study. Diabet Med. 2020;37(10):1759–1765. doi: 10.1111/dme.14285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beaudet A, Clegg J, Thuresson PO, Lloyd A, McEwan P. Review of utility values for economic modeling in type 2 diabetes. Value Health. 2014;17(4):462–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rohatgi A. WebPlotDigitizer Version 4.5. https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer/. Accessed 7 Jun 2023.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.