Abstract

A PCR was developed for the detection of Escherichia coli O157 based on the rfbE O-antigen synthesis genes. A 479-bp PCR product was amplified specifically from E. coli O157 in cell lysates containing 200 or 2 CFU following crude DNA extraction. The PCR detected <1 CFU of E. coli O157 per ml in raw milk following enrichment.

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) strains have emerged as important human enteric pathogens. Strains which express the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) O-antigen 157 (O157 strains) are commonly associated with severe clinical manifestations, including bloody diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis, and hemolytic uremic syndrome (19). Illness caused by E. coli O157 occurs sporadically, in small clusters and outbreaks, and may be transmitted in a variety of ways, including through food and water and through person-to-person and animal-to-person contact (1). Ruminants have been established as important reservoirs of E. coli O157, and foods derived from or contaminated by animals and their products are an important source.

Since the recognition of E. coli O157 as an important human pathogen, a large number of methods have been designed specifically for the isolation of this serotype in clinical, food, animal, and environmental specimens. Selective agars and enrichment broths are available, the selectivity of which is based on the specific phenotypic characteristics of most E. coli O157:H7 strains, namely, lack of sorbitol fermentation, failure to produce β-glucuronidase, and resistance to antibiotics and other inhibitory agents, such as tellurite (1). Immunologically based assays have been developed for the detection of STEC by detection of Shiga toxin production and, more specifically, for the detection of E. coli O157 based on detection of the O157 LPS antigen (3). With E. coli O157 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits, few cells can be detected following enrichment in selective medium and can be isolated by immunomagnetic separation (2, 3).

An alternative approach is the detection of genes characteristic of enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) or specific to the serogroup. Hybridization with DNA probes or amplification of specific gene fragments by PCR has been successfully used to detect virulence factors of EHEC, such as the stx, eae, and hly genes (4, 8–10, 12, 16, 18). Genes more specific for the O157 serotype have been identified. Feng (7) identified E. coli O157:H7 by using a DNA probe and by PCR, both of which targeted a unique base substitution in the uidA gene encoding production of the enzyme β-glucuronidase (6, 7). Meng et al. (14) designed a PCR which amplifies a fragment of a gene encoding an outer membrane protein of E. coli O157:H7 and O55.

Because of the potential clinical severity of infections due to E. coli O157, a rapid response is required in outbreak investigations and case management. There is a need for sensitive, specific, and rapid methods which will alert the clinician and the public health microbiologist to the presence of E. coli O157 in clinical and other specimens. In addition, there is a need for a sensitive, rapid, and specific technique to identify pathogenic E. coli O157 in polymicrobial substances such as food and water, in which the number of pathogenic organisms may be low (11, 17, 20). The isolation and identification of E. coli O157 finally depend on the confirmation of E. coli and identification of the O157 antigen. We designed a PCR specific for E. coli O157 by using chromosomal sequences that encode the enzymes necessary for the biosynthesis of the O157 lipopolysaccharide. The PCR was subsequently evaluated by the analysis of raw milk.

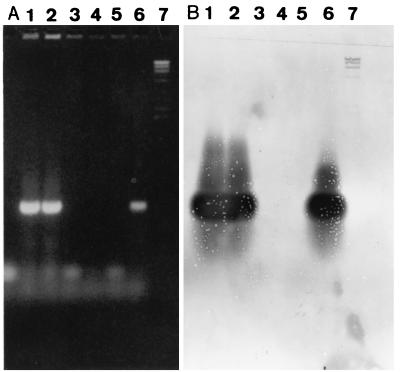

PCR primers were chosen from a region contiguous to the rfbE gene of E. coli O157 (5) by using the software program OLIGO V5.0 (National Biosciences, Inc.), which amplified a 497-bp fragment. For PCR amplification, a whole-cell preparation and a boiled-cell lysate of E. coli O157:H7 (strain EDL933, kindly provided by M. Doyle, University of Georgia, Athens) were tested as crude DNA templates. A whole-cell suspension was prepared by suspending a bacterial colony from nutrient agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) in sterile distilled water. A boiled-cell lysate was prepared by heating the suspension for 10 min in a boiling water bath and centrifuging it for 5 min at 17,000 × g to pellet cellular debris. Boiled-cell lysates were also treated with Instagene (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Whole-cell preparations produced poor results, and because the boiled-cell lysates with or without the Instagene clean up were suitable templates for pure culture preparations, a boiled-cell lysate was used in subsequent experiments. Following optimization, the PCR mixture (total volume of 25 μl) contained 2 μl of crude cell lysate, 67 mM Tris (pH 8.8), 16.6 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.2 mg of gelatin per ml, 4.5% Trixon X-100 (Bresatec, Adelaide, Australia), 3 mM MgCl2, 200 μM (each) deoxynucleotide triphosphates, 400 ng of bovine serum albumin (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) per ml, 5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Bresatec), and 1.5 μM (each) forward primer O157AF (5′ AAG ATT GCG CTG AAG CCT TTG3′) and reverse primer O157AR (5′ CAT TGG CAT CGT GTG GAC AG 3′), synthesized by Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, Md.). Thermocycling was performed in a Hybaid Omnigene thermocycler (Hybaid, Middlesex, United Kingdom) with simulated tube control and the following three-step PCR cycling conditions: an initial denaturation of 1 cycle at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles, each consisting of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 66°C, and 30 s at 72°C. The amplified PCR product was visualized by ethidium bromide staining of PCR product separated by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gels (Progen, Brisbane, Australia) at 100 V for 40 min in Tris-acetate buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]). The identity of the 497-bp PCR product was confirmed by Southern blotting (13) of the electrophoresed product with a digoxigenin (DIG)-labelled probe synthesized with a PCR DIG probe synthesis kit (Boehringer Mannheim) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Probe signals of 497 bp were detected for strains which were amplified in the O157 rfb PCR (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel of O157 rfb PCR products (A) and Southern hybridization of the gel with the O157 rfb PCR product probe (B). Lanes: 1 and 2, E. coli O157 isolates; 3 to 5, untyped animal STEC isolates; 6, O157:H7; 7, DIG λ ladder II (Boehringer Mannheim).

The O157 rfb PCR primers were tested with crude boiled-cell lysates from 60 E. coli strains and 6 strains belonging to other genera (Table 1). All E. coli O157:H7 and O157:H− isolates produced a 497-bp PCR product. No other E. coli serotype or other species tested produced a PCR product of any size, including Salmonella Angoda, which reacts with E. coli O157 antiserum (Oxoid) in a latex slide agglutination test. The sensitivity of the O157 rfb PCR was determined by amplification of serial 10-fold dilutions in 1% peptone water of an overnight broth culture of E. coli O157:H7 EDL933. Boiled-cell lysates were tested directly and after treatment with Instagene (Bio-Rad). A 497-bp PCR product was amplified from dilutions of EDL933 containing as few as 200 CFU per PCR mixture and from dilutions containing as few as 2 CFU per PCR mixture when the boiled-cell lysate was further purified with Instagene.

TABLE 1.

E. coli serotypes tested with the O157 rfb PCR

| Serotype or species | No. of strains tested |

|---|---|

| O157:H7 and H− | 39a |

| O55:H7 | 7 |

| O26:H−; H2; H11 | 4 |

| O111:H− | 2 |

| O6:H10 | 1 |

| O85:H− | 1 |

| O103:H2 | 1 |

| O103:H6 | 1 |

| Untyped animal STEC | 4 |

| Vibrio cholerae | 1 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1 |

| Citrobacter freundii | 1 |

| Brucella abortus | 1 |

| Yersinia enterocolitica (serotype O9) | 1 |

| Salmonella Angoda (group N) | 1 |

Note that for O157:H7 and O157:H−, all 39 strains tested had a positive PCR result. None of the other strains of the serotypes listed had a positive PCR result.

The O157 rfb PCR was evaluated as a screening test for the detection of E. coli O157 in raw milk, and the results were compared with those of the Tecra visual immunoassay (VIA) (Tecra, Sydney, Australia) and the visual immunoprecipitate (VIP) assay kit (BioControl). Isolation was by direct plating onto selective agar following immunocapture with the Tecra E. coli O157 immunocapture confirmation system and Dynabeads anti-E. coli O157 immunocapture system (Dynal, Oslo, Norway). Raw milk samples were diluted 1 in 10 in 250 ml (each) of modified Trypticase soy broth without novobiocin (mTSB−n) and mTSB containing novobiocin at a final concentration of 20 mg/liter (mTSB+n) (15). The diluted milk samples were inoculated with 1 ml (each) of serial 10-fold dilutions of E. coli O157 isolates, CL8 (human isolate kindly supplied by M. Doyle), and EC200 (beef carcass isolate; Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation). Strain CL8 was agglutinable with an O157 latex agglutination test (Oxoid). Strain EC200 was typed by agglutination with O157 antiserum on isolation in 1996 and was stored in glycerol at −70°C. EC200 was recovered from stock culture, and during repeated subculture and storage in artificial medium gave inconsistent agglutination reactions. The enrichments were incubated at 37°C for 18 ± 2 h in an incubator fitted with a rotary shaker. The concentration of each inoculum was determined by plate counting on nonselective nutrient agar (Oxoid). The Tecra ELISA, Tecra immunocapture confirmation system, VIP, and Dynabead systems were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The O157 rfb PCR was performed with milk enrichments as described above. A 1-ml volume of enrichment was centrifuged to deposit cellular material, and the supernatant was discarded. A crude DNA template was prepared with Instagene (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

By each of the screening methods (PCR, ELISA, and VIP assay), a positive result was obtained when 10 CFU of CL8 was inoculated into 250 ml of diluted raw milk, equivalent to a final concentration of 0.4 CFU/ml in the raw milk (Table 2). CL8 was isolated from the enrichments at the same concentration by both the Tecra immunocapture and Dynabead systems. Enrichment in mTSB+n improved the limit of detection 10- to 100-fold. The PCR had similar limits of detection with strain EC200, which was detected at concentrations of 10 and 1 CFU with mTSB−n and mTSB+n, respectively. Detection of EC200 was less consistent with the antibody-based assays. No positive results were obtained with the Tecra VIA or VIP assay when up to 1.3 × 103 CFU of EC200 inoculated into raw milk was enriched in mTSB−n. The limit of detection was lower after enrichment in mTSB+n, and an inoculum of 1.3 × 103 CFU was required to produce a positive reaction with both assays. Isolates were recovered with the Tecra immunocapture from mTSB−n inoculated with 1.3 × 103 CFU and from mTSB+n inoculated with as few as 1 CFU. Isolates were not recovered by using the Dynabeads at any of the concentrations included with either enrichment. EC200 produced colonies inconsistently agglutinable with O157 antiserum in the latex slide agglutination. The proportions of cells with O157 antigens available for agglutination in the enrichment broths used in the antigen-based assays would similarly have been variable and would have affected the level of inoculum detectable. It was concluded that the methods used had comparable limits for the detection of E. coli O157 in raw milk. The PCR was subsequently used to screen 147 samples of raw milk collected during a pilot study preliminary to a larger study of raw milk produced along the East Coast of Australia. No O157 rfb PCR amplification product was detected in any samples. Inoculated control milk samples were tested in parallel and verified the performance of the PCR.

TABLE 2.

Detection and isolation of E. coli O157 by PCR, immunoassay, and immunocapture techniques

| Inoculum level (CFU) | Detection of E. coli O157 in raw milk enriched witha:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mTSB−n

|

mTSB+n

|

|||||||||

| Screening

|

Isolation

|

Screening

|

Isolation

|

|||||||

| rfb PCR | VIP | Tecra VIA | Dynabeads | Tecra immunocapture | rfb PCR | VIP | Tecra VIA | Dynabeads | Tecra immunocapture | |

| CL-8 (uninoculated) | − | − | − | − | − | − | NT | − | − | − |

| 1.3 × 103 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 1.3 × 102 | + | NT | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 13 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 1 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| <1 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| EC200 (uninoculated) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 1.3 × 103 | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| 1.3 × 102 | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| 13 | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| 1 | − | NT | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + |

| <1 | − | NT | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

−, E. coli O157 undetected; +, E. coli O157 detected; NT, not tested.

The O157 rfb PCR is a sensitive, specific, and rapid method for the confirmation of the O157 serotype and has potential as a screening test for evidence of the presence of E. coli O157 in fecal, food, and environmental samples. The O157 rfb PCR should detect strains of both the sorbitol-fermenting and nonfermenting phenotypes, although sorbitol-fermenting E. coli O157 strains were not tested here. The PCR does not discriminate between strains which produce the Shiga toxins and those which do not, although it is possible to include the O157 rfb PCR in a multiplex system. The PCR has an additional advantage in terms of the detection of isolates that have a masked O antigen or when isolates become rough. In the past, we have isolated E. coli and received isolates from industry laboratories, which autoagglutinate and require heating to determine the serotype. Given the implications of the detection of E. coli O157 from clinical cases of infection and foods, accuracy in identification is essential.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance of M. Fegan, the University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, with the use of the OLIGO program and T. Whittam, University of Pennsylvania, for providing cultures of E. coli O55:H7.

The work conducted at the Children’s Hospital and Medical Center was funded by USDA National Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program grant 96-01601.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong G L, Hollingsworth J, Morris G., Jr Emerging foodborne pathogens: Escherichia coli O157:H7 as a model of entry of a new pathogen into the food supply of the developed world. Epidemiol Rev. 1996;18:29–51. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett A R, MacPhee S, Betts R P. Evaluation of methods for the isolation and detection of Escherichia coli O157 in minced beef. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1995;20:375–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1995.tb01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett A R, MacPhee S, Betts R P. The isolation and detection of Escherichia coli O157 by use of immunomagnetic separation and immunoassay procedures. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1996;22:237–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1996.tb01151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beutin L, Geier D, Zimmermann S, Karch H. Virulence markers of Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains originating from healthy domestic animals of different species. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:631–635. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.631-635.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bilge S S, Vary J C, Jr, Dowell S F, Tarr P I. Role of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 O side chain in adherence and analysis of an rfb locus. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4795–4801. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4795-4801.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cebula T A, Payne W L, Feng P. Simultaneous identification of strains of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 and their Shiga-like toxin type by mismatch amplification mutation assay-multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:248–250. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.248-250.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng P. Identification of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 by DNA probe specific for an allele of uidA gene. Mol Cell Probes. 1993;7:151–154. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1993.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fratamico P M, Sackitey S K, Wiedmann M, Deng M Y. Detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2188–2191. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.2188-2191.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gannon V P J, King R K, Kim J Y, Golsteyn Thomas E J. Rapid and sensitive method for detection of Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli in ground beef using the polymerase chain reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3809–3815. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.12.3809-3815.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karch H, Meyer T. Single primer pair for amplifying segments of distinct Shiga-like-toxin genes by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2751–2757. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.12.2751-2757.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keene W E, McAnulty J M, Hoesly F C, Williams L P J, Hedberg K, Oxman G L, Barrett T J, Pfaller M A, Fleming D W. A swimming-associated outbreak of hemorrhagic colitis caused by Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Shigella sonnei. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:579–584. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409013310904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Louie M, De Azavedo J, Clarke R, Borczyk A, Lior H, Richter M, Brunton J. Sequence heterogeneity of the eae gene and detection of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli using serotype-specific primers. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;112:449–461. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800051153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meng J, Zhao S, Doyle M P, Mitchell S E, Kresovich S. Polymerase chain reaction for detecting Escherichia coli O157:H7. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996;32:103–113. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(96)01110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neaves P, Deacon J, Bell C. A survey of the incidence of Escherichia coli O157 in the UK dairy industry. Int Dairy J. 1994;4:679–696. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paton A W, Paton J C, Goldwater P N, Heuzenroeder M W, Manning P A. Sequence of a variant Shiga-like toxin type-I operon of Escherichia coli O111H−. Gene. 1993;29:87–92. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90700-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paton A W, Ratcliff R M, Doyle R M, Seymour-Murray J, Davos D, Lanser J A, Paton J C. Molecular microbiological investigation of an outbreak of hemolytic-uremic syndrome caused by dry fermented sausage contaminated with Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1622–1627. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1622-1627.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pollard D R, Johnson W M, Lior H, Tyler S D, Rozee K R. Rapid and specific detection of verotoxin genes in Escherichia coli by the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:540–545. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.540-545.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarr P I. Escherichia coli O157:H7: clinical, diagnostic, and epidemiological aspects of human infection. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;20:1–10. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tilden J J, Young W, McNamara A M, Custer C, Boesel B, Lamber-Fair M A, Majkowski J, Vugia D, Werner S B, Hollingsworthe J, Morris J G J. A new route of transmission for Escherichia coli: infection from dry fermented salami. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1142–1145. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.8_pt_1.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]