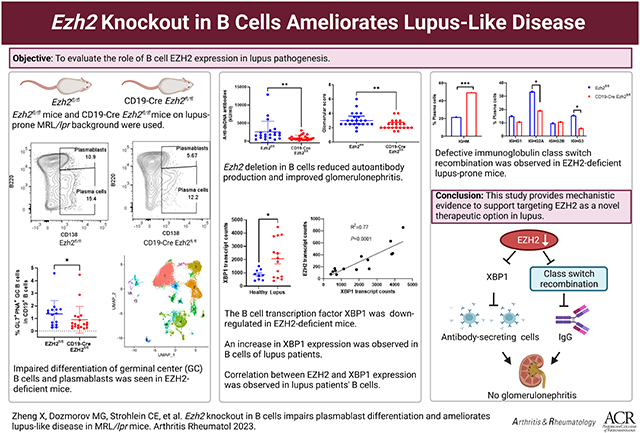

Abstract

Objectives:

Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) regulates B cell development and differentiation. We have previously demonstrated increased EZH2 expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from lupus patients. The goal of this study was to evaluate the role of B cell EZH2 expression in lupus pathogenesis.

Methods:

We generated an MRL/lpr mouse with floxed Ezh2, which was crossed with CD19-Cre mice to examine the effect of B cell EZH2 deficiency in MRL/lpr lupus-prone mice. Differentiation of B cells was assessed by flow cytometry. Single-cell RNA sequencing and single-cell B cell receptor sequencing were performed. In vitro B cell culture with an XBP1 inhibitor was performed. EZH2 and XBP1 mRNA levels in CD19+ B cells isolated from lupus patients and healthy controls were analyzed.

Results:

We show that Ezh2 deletion in B cells significantly decreased autoantibody production and improved glomerulonephritis. B cell development was altered in the bone marrow and spleen of EZH2-deficient mice. Differentiation of germinal center B cells and plasmablasts was impaired. Single-cell RNA sequencing showed that XBP1, a key transcription factor in B cell development, is downregulated in the absence of EZH2. Inhibiting XBP1 in vitro impairs plasmablast development similar to EZH2-deficient mice. Single-cell B cell receptor RNA sequencing revealed defective immunoglobulin class switch recombination in EZH2-deficient mice. In human lupus B cells, we observed a strong correlation between EZH2 and XBP1 mRNA expression levels.

Conclusion:

EZH2 overexpression in B cells contributes to disease pathogenesis in lupus.

Keywords: Lupus, EZH2, B cells, Plasmablast, Germinal Center

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE or lupus) is a multi-system autoimmune disease characterized by B cell autoreactivity and autoantibody production. Substantial research has pointed to the involvement of both genetic and epigenetic mechanisms in the pathogenesis of lupus (1, 2). In particular, abnormal DNA methylation has been shown to play crucial roles in this disease (3-5). We have previously demonstrated that the expression of the key epigenetic modulator Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) is dysregulated in lupus peripheral blood mononuclear cells compared to healthy controls (6). EZH2, a core component of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), is a histone methyltransferase that catalyzes methylation of lysine 27 in histone H3 (H3K27) (7). We have shown that overexpression of EZH2 in lupus CD4+ T cells is associated with pro-inflammatory epigenetic changes with potential pathogenic consequences in lupus patients (5, 8, 9). Further, we demonstrated that inhibiting EZH2 ameliorates lupus-like disease in animal models (6), which was subsequently confirmed by others (10, 11). However, the role of EZH2 and EZH2-regulated genes in lupus B cells has not been adequately explored.

EZH2 plays a critical role in B cell development and differentiation (12). EZH2 is required for germinal center (GC) B cell development and function, and EZH2 gain of function leads to GC hyperplasia (13). Spontaneous and expanded GCs are a feature of murine and human lupus (14). EZH2 regulates immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement in progenitor B (Pro-B) cells (12), and represses germline transcription of immunoglobulin κ-chain complex in precursors of B (Pre-B) cells (15). Further, EZH2-dependent regulation of transcriptional activity and cellular metabolism is required for antibody production (16).

We have previously shown that EZH2 is overexpressed in lupus B cells compared to normal healthy controls (6). This observation was independently confirmed (17), with additional data demonstrating correlation between EZH2 expression levels in B cells with disease activity and autoantibody production in lupus patients (17). Activation of Syk and mTORC1 synergistically induce EZH2 expression in B cells (17). Indeed, both Syk and mTORC1 are activated in B cells from lupus patients, providing a mechanism explaining EZH2 overexpression in lupus B cells (17, 18).

In this study, we generated CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice on lupus-prone MRL/lpr background to investigate the pathogenic role of EZH2 in lupus B cells. Our results showed that Ezh2 deletion in B cells significantly decreased autoantibody production and alleviated lupus glomerulonephritis. Differentiation of antibody secreting cells and class switch recombination were significantly impaired in EZH2-deficient mice. B-cell specific EZH2 deficiency led to reduced expression of XBP1, which is a key transcription factor involved in plasmablast/plasma cell development and immunoglobulin production. Further, in human lupus B cells, the mRNA expression of EZH2 was very strongly correlated with XBP1 expression.

Methods

Mice.

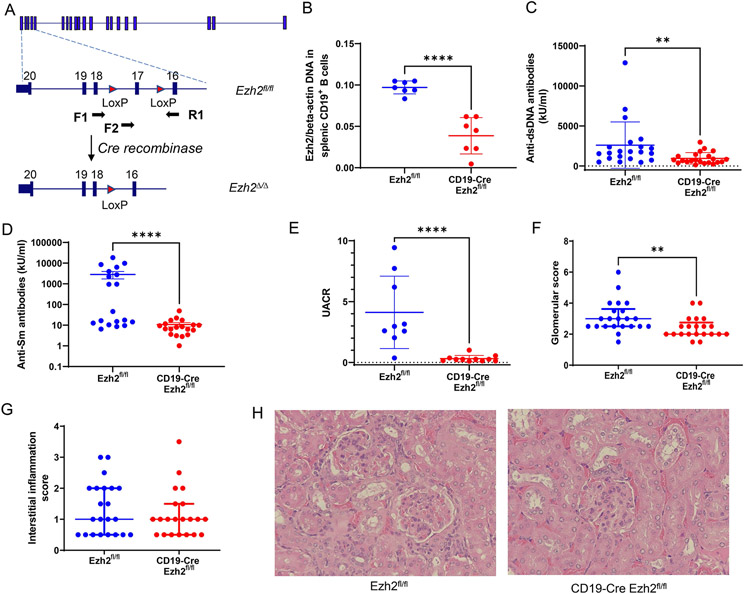

An Ezh2fl/fl mouse on the MRL/lpr lupus-prone background was generated by genetic engineering using CRISPR/Cas9 technology at the Innovative Technologies Development Core and the Mouse Embryo Services Core (Department of Immunology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine). LoxP/LoxP alleles were flanked on Ezh2 exon 17, whose deletion mediated by Cre will cause a frameshift and ultimately an absence of transcription (Figure 1A). CD19-Cre MRL/lpr mice were a gift from Dr. Mark Shlomchik at the University of Pittsburgh (19). CD19-Cre MRL/lpr mice were crossed with Ezh2fl/fl mice, then heterozygous CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/wt mice were bred with Ezh2fl/fl mice. CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice were used as the experimental mouse group and littermate Ezh2fl/fl mice lacking the Cre transgene as controls. Genotyping primers were as follows: Ezh2 F1: GAACAAGGGGTTCGGGATCA; Ezh2 R1: AGCACACCCACTTACACAGG. CD19 forward primer: AATGTTGTGCTGCCATGCCTC; CD19-Cre reverse primer: TTCTTGCGAACCTCATCAC; CD19 reverse primer: GTCTGAAGCATTCCACCGGAA. Q5 high-fidelity DNA polymerases (NEW ENGLAND BioLabs) were used for genotyping (Supplementary Methods). DNA (DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit, QIAGEN) isolated from CD19+ B cells (stained with brilliant violet (BV) 421 anti-mouse CD19 antibody, Clone 6D5, BioLegend) sorted by FACS Arial II (BD Biosciences) were used to measure deletion efficiency of Ezh2. The primers used were Ezh2 F2: GTGTTCTAACAGTCTTGACCA; Ezh2 R1: AGCACACCCACTTACACAGG (as shown in Figure 1A). Beta-actin primers used were Actb F1: CATTGCTGACAGGATGCAGAAGG; Actb R1: TGCTGGAAGGTGGACAGTGAGG. CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl experimental mice and Ezh2fl/fl control mice were housed under the same pathogen-free conditions for 24 weeks before they were sacrificed. Ezh2 deletion was confirmed with DNA isolated from CD19+ splenocytes in the CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl compared to the Ezh2fl/fl littermate control mice (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. EZH2 deficiency in CD19+ B cells decreases serum autoantibody levels and ameliorates lupus nephritis.

(A) Ezh2 genomic targeting strategy in MRL/lpr mice. Exon 17 in the SET methyltransferase domain of Ezh2 was flanked by LoxP sites to be deleted by Cre recombinase. F1, F2, and R1 indicate primer loci. F1-R1 primers were used for Ezh2fl/fl genotyping and F2-R1 primers were to check Ezh2 deletion efficiency. (B) DNA Ezh2 measured with F2-R1 primers in qPCR normalized to beta-actin in CD19+ B cells sorted with flow cytometry. (C) Serum anti-double stranded (ds) DNA antibody levels, (D) anti-Smith (Sm) antibody levels, (E) urine albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR), (F) glomerular scores and (G) interstitial inflammation scores, and (H) representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) images in the female Ezh2fl/fl and CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice. Data in (B, C and E) are presented as mean ± SD, data in (D) are presented as mean ± SEM, data in (F and G) are presented as median with interquartile range, ** p<0.01, ****p<0.0001, unpaired two-tailed t test in (B) and two-tailed Mann-Whitney test in (C) to (G). Magnification in (H), 400X.

Flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow and spleen B cells.

Bone marrow cells were isolated from both the femur and tibia. The spleen was mashed and prepared into single-cell suspension. Red bloods cells (RBC) from the bone marrow and spleen were lysed with RBC lysis buffer (Invitrogen) in room temperature for 5 minutes. Cells were resuspended in PBS containing 1% FBS and incubated with mouse FcR blocking reagent (Miltenyi Biotec) for 10 minutes at 4°C before antibody staining with 1:50 dilution for 30 minutes at 4°C. Flow cytometry data were acquired by LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences) and analyzed by FlowJo software (version 10.8, BD Biosciences).

The following antibodies were used to detect B cell populations in the bone marrow: brilliant violet (BV) 421 anti-mouse CD19 antibody (Clone 6D5, BioLegend), PE/Cyanine5 anti-mouse/human CD45R/B220 (Clone RA3-6B2, BioLegend), PE-Dazzle 594 rat anti-mouse CD43 (Clone 1B11, BioLegend), VioBright 515 anti-mouse IgM (Clone REA979, Miltenyi Biotec), SuperBright 702 rat anti-mouse IgD (Clone 11-26c, eBioscience), and fixable near-IR dead cells stain kit (Invitrogen).

To analyze B cell subsets in the spleen, the following antibodies were used: BV786 rat anti-mouse CD93 (Clone 493, BD Biosciences), BV480 rat anti-mouse CD21/CD35 (Clone 7G6, BD Biosciences), BV605 anti-mouse CD23 (Clone B3B4, BD Biosciences), PerCP/Cyanine5.5 anti-mouse/human GL7 (Clone GL7, BioLegend), rhodamine anti-peanut agglutinin (PNA, Vector Laboratories), APC anti-mouse CD38 (Clone 90, BioLegend), PE/Cyanine7 anti-mouse CD138 (Syndecan-1) (Clone 281-2, BioLegend), and the same anti-CD19, anti-B220, anti-IgM, anti-IgD, and live/dead staining used for bone marrow cells.

Plasma autoantibody measurement.

Plasma samples were collected from mice at 24 weeks of age. Anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) antibody and anti-Smith (anti-Sm) antibody were measured by ELISA following the manufacturer’s instructions (Catalog numbers 5110 and 5405, respectively, Alpha Diagnostic International, San Antonio, USA).

Assessment of proteinuria and nephritis.

Urine was collected within one week before mice were sacrificed. Urine albumin and creatinine were measured using ELISA kits (Alpha Diagnostic International, San Antonio, USA, and R&D systems, Minneapolis, USA, respectively). Urine samples were diluted to fit within the standards range of each kit. Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) was calculated to assess proteinuria.

Kidneys were harvested, fixed with formalin for 2 days, then dehydrated in 70% ethanol and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Glomerulonephritis and interstitial inflammation were reviewed by a renal pathologist in a blinded manner. Glomerulonephritis was scored on a scale from 1 to 6, and interstitial inflammation was scored on a scale from 0 to 4, as previously described (20).

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq).

Splenocytes isolated from four female mice (two Ezh2fl/fl and two CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl) were stained with BV421 anti-mouse CD19 antibody (Clone 6D5, BioLegend) and live/dead dye, and sorted with FACS Arial II (BD Biosciences). Splenic B cells from each mouse were incubated with a unique TotalSeq-C anti-mouse hashtag antibody conjugated to a Feature Barcode oligonucleotide (BioLegend) to label each mouse at 4°C in 100 μl PBS+0.04% BSA for 30 minutes. Splenic B cells from four mice were pooled and gel beads in emulsion were formed. Single-cell 5’ gene expression sequencing library, single-cell V(D)J enriched library for B cell receptor (BCR) sequencing, and cell surface protein Feature Barcode library were prepared following 10X Genomics instructions in the Single Cell Core, University of Pittsburgh. Sequencing was performed with 100-cycle NovaSeq v1.5 to achieve a total of 800M reads, including ~5000 reads per cell for the BCR library and 5000 reads for Feature Barcode library and the rest for gene expression library.

Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis.

Cell Ranger v. 6.0.1 (10X Genomics, Pleasanton, CA, USA) was used to process raw sequencing data. Data analysis was performed using Seurat v.4.1 R package. Integration of two Ezh2fl/fl and two CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl datasets was performed as described (21) (“Introduction to scRNA-seq integration” vignette) with minor modifications. All genes were used for integration. 11,356 cells were analyzed from two female Ezh2fl/fl mice with an average of 21,318 reads per cell and 1,652 median genes per cell. 4,971 cells were sequenced and analyzed from two female CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice with an average of 10,808 reads per cell and 1,211 median genes per cell. The standard workflow for visualization and clustering was used ("Seurat - Guided Clustering Tutorial” vignette). Clustering resolution (“resolution” parameter in the FindClusters function) was set to 0.5 to obtain biologically expected number of clusters. Cluster-specific conserved markers were detected using the FindConservedMarkers function. Clusters were manually annotated based on cluster-specific differentially expressed genes; selected clusters were merged to represent major cell types (“GC cells,” “Plasmablast,” “Plasma cells”). B-cell receptor sequencing data for each condition were integrated with scRNA-seq data based on cellular barcode, then annotated by the B cell identities defined at the RNA-seq analysis step. “RBC, DCs and monocytes,” “T cells and NK cells,” “Neutrophil,” and “RBC” clusters were removed. Immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH) data from filtered contig annotations were selected, and the proportions of the constant region gene family per cluster were quantified. Plots were made using Seurat’s visualization functions or the ggplot2 v3.3.5 R package. All computations were performed in R/Bioconductor v.4.1.0 (22).

In vitro XBP1 inhibition in cultured B cells.

Splenic B cells from 24-week old Ezh2fl/fl and CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice were isolated with a Pan B Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). B cells were cultured with RPMI-1640 medium (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 100 μg/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco, Waltham, MA USA) and 50 μM 2-Mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA), and with 3 μg/ml TLR7 agonist imiquimod (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) for 3 days. Imiquimod-stimulated B cells were treated simultaneously with or without the XBP1 inhibitor 4μ8c (23) (20 μM, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) dissolved in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) for 3 days.

Analysis of CD19+ B cells from human SLE patients and healthy controls.

EZH2 and XBP1 mRNA levels in CD19+ B cells isolated from 14 female lupus patients and 9 female age-matched healthy controls were downloaded from GEO database (accession number GDS4185) (24, 25). Patients were 38.9 ± 11.9 years old (mean ± SD). Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index (SLEDAI) scores at the time of blood draw were 8.8 ± 5.0 (mean ± SD), and median SLEDAI score was 8.

Statistics.

Data were reported as mean ± SD/SEM or median ± interquartile range. To compare two groups, 2-tailed Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test was used as indicated. Two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test was used in the in vitro XBP1 inhibition experiments. In single-cell sequencing data, Fisher’s exact test of normalized cell frequencies after excluding non-B cell clusters was used. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.2.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA).

Study approval.

This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Mouse protocol #19085735).

Results

B cell-specific Ezh2 deletion decreases autoantibody production in MRL/lpr mice.

Plasma anti-dsDNA antibody levels were significantly lower in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice compared to Ezh2fl/fl littermate controls (Figure 1C). Female Ezh2fl/fl MRL/lpr mice had high anti-dsDNA antibody level compared to male Ezh2fl/fl MRL/lpr mice, and Ezh2 deletion in B cells significantly decreased anti-dsDNA levels in female but not male mice (Supplementary Figure 1A). RNA-associated anti-Smith (Sm) antibody levels were significantly decreased with EZH2 deficiency in B cells compared to littermate controls (Figure 1D), which was observed in both male and female mice (Supplementary Figure 1B). These results indicate that EZH2 is required to produce high levels of anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm antibodies in MRL/lpr mice, and that EZH2 deficiency in B cells significantly repressed autoantibody production in this lupus-prone mouse model.

Ezh2 deletion in B cells alleviates lupus nephritis.

We examined the effect of B cell-Ezh2 deletion on lupus nephritis in MRL/lpr mice. Urine albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR) was used to evaluate renal disease severity. UACR was significantly lower in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice compared to littermate controls (Figure 1E), both in female and male mice (Supplementary Figure 1D). In addition, mice kidneys were fixed, sectioned, stained with H&E, and blindly reviewed by a renal pathologist. Glomerulonephritis scores were significantly lower in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice compared to Ezh2fl/fl mice (Figure 1F), but not interstitial nephritis scores (Figure 1G, supplementary Figure 1D and 1E). Representative kidney H&E staining images from CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl and control mice are shown in Figure 1H. Ezh2 deletion in B cells had sex-specific effects on peripheral lymphoproliferation, males had significantly larger spleens and similar size of lymph nodes, while females had a trend of smaller spleens and significantly smaller lymph nodes compared to Ezh2fl/fl mice (Supplementary Figure 2). There was no significant difference in survival and skin lesions between CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl and control mice (data not shown).

Ezh2 deletion in B cells influences B cell development and differentiation in the bone marrow and spleen.

B cell lymphopoiesis starts in the bone marrow and matures in secondary lymphoid organs, such as the spleen, with linear and stepwise processes as shown in Figure 2A. Genes for immunoglobin (Ig) heavy chain and light chain are rearranged at the Pro-B and Pre-B stages, respectively. With cell surface IgM (sIgM) expressed, immature B cells are formed, which will egress to peripheral lymph organs as transitional B cells. In the spleen, B cells will mature and develop into marginal zone (MZ) B cells because of low BCR reactivity and NOTCH2 signaling, or follicular (FO) B cells due to intermediate BCR reactivity (26). Encountered with antigens, MZ B cells will differentiate into plasmablasts, and produce low- and high-affinity antibodies (26). FO B cells will become germinal center (GC) B cells and differentiate into memory B cells or plasmablasts/plasma cells and produce high-affinity antibodies (27).

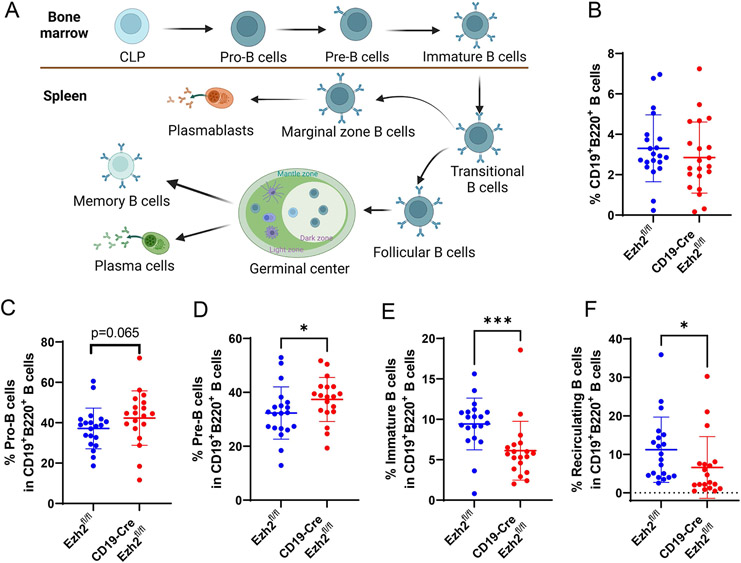

Figure 2. EZH2 deficiency negatively affects B cell development in the bone marrow.

(A) A schematic representation of B cell development and differentiation in the bone marrow and spleen. The figure was created using Biorender.com. Proportion of (B) CD19+B220+ B cells, and proportion of (C) Pro-B cells, (D) Pre-B cells, (E) immature B cells, and (F) recirculating B cells in CD19+B220+ B cells in Ezh2fl/fl and CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice. CLP, common lymphoid progenitor. Data are shown as mean ± SD. * p<0.05, *** p<0.001, two-tailed Mann-Whitney test.

We found that the proportion of total CD19+B220+ B cells in the bone marrow was not significantly different in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice compared to Ezh2fl/fl (Figure 2B). Gating strategies are shown in Supplementary Figure 3. Focusing on B cell subsets, Pro-B cells showed a trend for being increased (Figure 2C), Pre-B cells were significantly increased (Figure 2D), whereas immature B cells (Figure 2E) and recirculating B cells (Figure 2F) were significantly decreased in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice compared to littermate controls. Male and female mice exhibited similar changes in bone marrow B cells (Supplementary Figure 4). Taken together, these results indicate that Ezh2 deletion in B cells negatively affected immature B cell differentiation in the bone marrow. An increase in Pro-B cells may reflect a negative feedback loop in the bone marrow to generate more functional B cells.

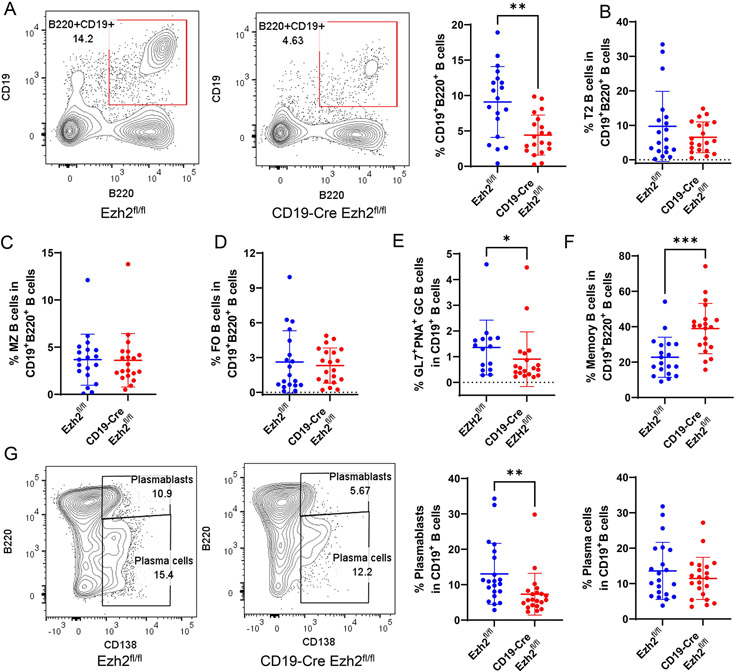

In the spleen, CD19+B220+ B cells were significantly reduced with EZH2 deficiency (Figure 3A, gating strategies are in Supplementary Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure 6). Proportions of transitional B cells (T2 B cells, Figure 3B), MZ B cells (Figure 3C), FO B cells (Figure 3D) were not significantly changed in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice compared to controls. The proportion of GC B cells was significantly decreased with EZH2 deficiency compared to controls (Figure 3E). Higher percentages of memory B cells were found in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice (Figure 3F). Differentiation of plasmablasts (Figure 3G) was inhibited in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl compared to controls. We found sex differences in B cell development in the spleen. CD19+B220+ B cells, proportion of T2 B cells, and GC B cells were significantly decreased in male CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice compared to littermate controls, but not in female mice (Supplementary Figure 7), which might relate to the inherent difference that male controls had higher percentage of splenic B cells compared to female Ezh2fl/fl mice (Supplementary Figure 7A). These results indicate that B cell differentiation in the spleen was disrupted with EZH2 deficiency. Antibody-secreting cells (ASCs) were significantly reduced, which might explain lower autoantibody production in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice.

Figure 3. EZH2 deficiency in splenic B cells inhibits antibody secreting cell differentiation.

(A) Representative flow cytometry plots, and summary data of splenic CD19+B220+ B cells in Ezh2fl/fl (n=19) and CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl (n=20) mice. (B) Proportion of transitional (T2) B cells, (C) marginal zone (MZ) B cells, (D) follicular (FO) B cells, (E) geminal center (GC) B cells and (F) memory B cells in CD19+B220+ B cells in Ezh2fl/fl and CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice. (G) Representative flow cytometry plots and frequency data of CD19+B220highCD138+ plasmablasts and CD19+B220low-mediumCD138+ plasma cells in CD19+B220+ B cells in Ezh2fl/fl (n=19) and CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl (n=20) mice. Data are shown as mean ± SD. ** p<0.01, ***p<0.001, two-tailed Mann-Whitney test.

Single-cell RNA-seq reveals B cell subset compositional and functional changes with Ezh2 deletion.

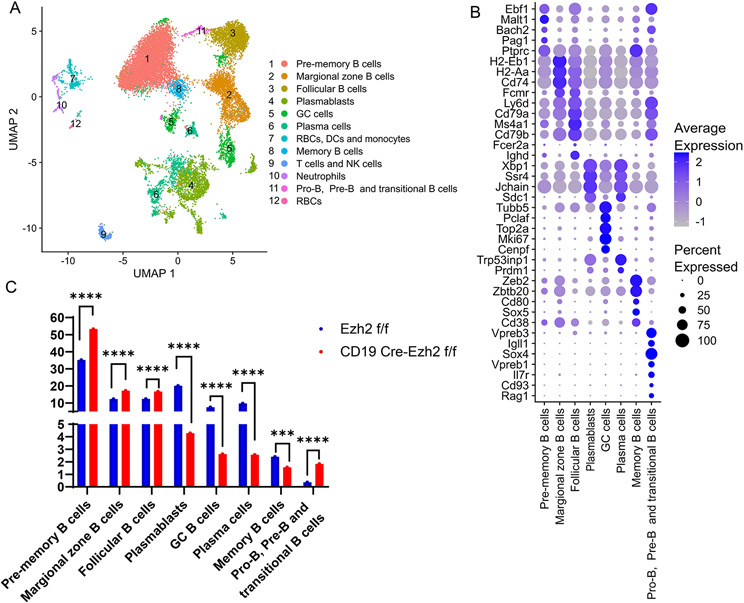

To explore why EZH2 deficiency in B cells inhibited ASC differentiation, single-cell RNA sequencing was performed in FACS-sorted splenic CD19+ B cells. In total, 21 splenic cell populations were clustered based on cell transcriptional profile. Cell identity of each cluster was determined by evaluating differentially expressed genes within the clusters (Supplementary Table 1). We annotated each cluster and combined two GC B cell clusters, six plasmablast clusters, and 5 plasma cell clusters into single clusters. Twelve final cell clusters were retained (Figure 4A), 4 of which were non-B cell clusters which were excluded from subsequent analysis (clusters 7, 9, 10, and 12). Marker genes defining each B cell cluster are presented in Figure 4B. Signature genes for pre-memory B cells (cluster 1) included Bach2 and Ptprc (28), and genes essential in B cell development including Ebf1, Malt1, and Pag1. Marker genes of MZ B cells (cluster 2) included high expression of MHC II genes (H2-Eb1, H2-Aa, Cd74) and Fcmr (encodes an Fc receptor of IgM) (29). FO B cells (cluster 3) are characterized by high expression of Ly6d (30), Cd79a, Ighd, Fcer2a (28), Ms4a1, and Cd79b. ASCs including plasmablasts and plasma cells highly expressed Xbp1 and Sdc1(31). It has been reported that Prdm1 is highly induced in plasma cells but not plasmablasts (32), based on which we distinguished plasmablasts with low Prdm1 expression and high levels of Jchain and Ssr4 (cluster 4) from plasma cells with high expression levels of Prdm1 and one of its target genes Trp53inp1 (cluster 6). GC B cells (cluster 5) were characterized by expression of Tubb5, Mki67, Top2a (28), Pclaf (33), and Cenpf (34). Memory B cells (cluster 8) overexpressed Zeb2, Cd38 (30), Cd80 (35), Zbtb20 (31), and Sox5(36). A cluster (cluster 11) characterized by genes important for Pro-B cells and Pre-B cells including Vpreb3, Igll1, Sox4, Vpreb1, Il7r, Cd93, and Rag1 was also present.

Figure 4. Single-cell RNA sequencing of female splenic B cells from Ezh2fl/fl (n=2) and CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl (n=2) mice.

(A) UMAP plot of B cells and other cell types combining Ezh2fl/fl and CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice. (B) Marker genes defining B cell clusters using single-cell RNA sequencing data from Ezh2fl/flmice. (C) Frequencies of B cell identities in Ezh2fl/fl and CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice. ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, Fisher’s exact test of normalized cell frequencies in each B cell subtype. GC, germinal center; RBC, red blood cells; DCs, dendritic cells; NK cells, natural killer cells.

We analyzed the proportions of each cell cluster to determine differences in B cell subset composition after excluding non-B cell clusters between EZH2-deficient and control mice. Transitional B cells, MZ B cells and FO B cells were significantly expanded in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl compared to Ezh2fl/fl mice (Figure 4C). Further, scRNA-seq results showed reduced differentiation of GC B cells, plasmablasts, and plasma cells in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice, confirming our flow cytometry data (Figure 4C). Pre-memory B cells were significantly expanded, while memory B cells were reduced in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice compared to controls.

XBP1 as a downstream target of EZH2 in B cells regulating plasmablast/plasma cell differentiation.

Because we observed reduced autoantibody production with B cell-Ezh2 deletion, and reduced plasmablasts/plasma cells (ASCs), we hypothesized that reduced ASC differentiation is probably key in explaining disease amelioration in our mouse model. To understand why ASC differentiation was defective with EZH2 deficiency in lupus mouse B cells, and because T cell-dependent and T cell-independent ASCs primarily arise from GC and MZ B cells (37), we examined differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in GC and MZ B cell subsets in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice compared to Ezh2fl/fl control mice (Complete lists of DEGs in all clusters are shown in Supplementary Table 2). There were 322 and 371 significant DEGs in GC B and MZ B cell subsets, respectively, with 73 common differentially expressed genes in both GC and MZ B cell subsets (Figure 5A). Functional enrichment analysis of these 73 DEGs (50/73 were used for analysis, the other 23 were mouse immunoglobulin heavy and light chain genes) was performed using ToppGene (https://toppgene.cchmc.org/enrichment.jsp), and revealed one Gene Ontology related to B cell activation (GO: 0042113, Supplementary Table 3), which included 7 genes: MZB1, BATF, IGHG1, XBP1, CD79A, CD81, and LGALS1 (Supplementary Table 4). The expression of XBP1, which is a key regulator for B cell development and plasmablast/plasma cell differentiation was significantly downregulated with Ezh2 deletion (P= 1.4X10−3 and 7.2X10−6, in GC and MZ B cells, respectively). The expression of BACH2, which has been previously shown to regulate XBP1 expression in B cells (17), was not different between EZH2-deficient and control mice (not shown), suggesting the involvement of alternative mechanisms for XBP1 regulation in our disease model.

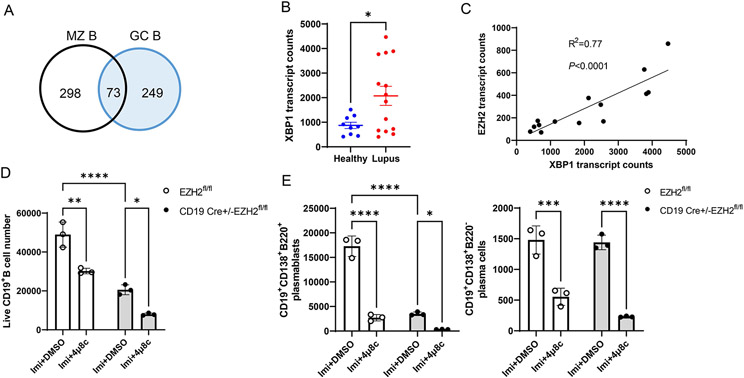

Figure 5. XBP1 expression in human CD19+ cells and XBP1 inhibition in B cells from MRL/lpr mice.

(A) Venn diagrams depicting the number of differentially expressed genes in marginal zone (MZ) B cells and germinal center (GC) B cells between Ezh2fl/fl and CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice in single-cell RNA sequencing. (B) XBP1 transcript counts in CD19+ B cells from female healthy controls (n=9) and female lupus patients (n=14) in RNA-sequencing. Data are presented as mean ± SE. * p<0.05, unpaired two-tailed t test. (C) Correlation plot of XBP1 and EZH2 mRNA expression levels from female lupus patients (n=14). (D) CD19+ B cells, and (E) plasmablasts and plasma cells isolated from the spleen of Ezh2fl/fl and CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice after stimulation with 3 μg/ml TLR7 agonist imiquimod (Imi) with and without 20 μM XBP1 inhibitor 4μ8c for 3 days. 250,000 cells from each sample were harvested for analysis. Plasmablasts and plasma cells were gated from live CD19+ B cells. DMSO was used as vehicle control. Results are presented as mean ± SD, data are representative of 3 independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

Analyzing mRNA expression levels in peripheral blood B cells, comparing lupus patients with normal healthy controls, revealed significant increase in XBP1 expression in lupus patients (Figure 5B). Indeed, there was a strong correlation between EZH2 expression and XBP1 expression levels in CD19+ B cells from lupus patients (R2=0.77, Figure 5C).

To determine if decreased XBP1 leads to reduced plasmablast and plasma cell differentiation in MRL/lpr mice, we isolated B cells from the spleen of Ezh2fl/fl and CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice and stimulated them in vitro with imiquimod to induce plasmablast differentiation in the presence or absence of the XBP1 inhibitor 4μ8c. XBP1 inhibition resulted in significant suppression of imiquimod-induced B cell expansion from Ezh2fl/fl and CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice (Figure 5D, Supplementary Figure 8A), and defective plasmablast and plasma cell differentiation (Figure 5E, Supplementary Figure 8B). The numbers of CD19+ B cells and plasmablasts were significantly lower in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice compared to Ezh2fl/fl after imiquimod stimulation, which is consistent with what we found in splenocytes without stimulation (Figure 3G). These data suggest that XBP1 downregulation in EZH2-deficient B cells might at least partly explain reduced plasmablast and plasma cell differentiation in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice.

Class switch recombination (CSR) is defective in B cell EZH2-deficient mice.

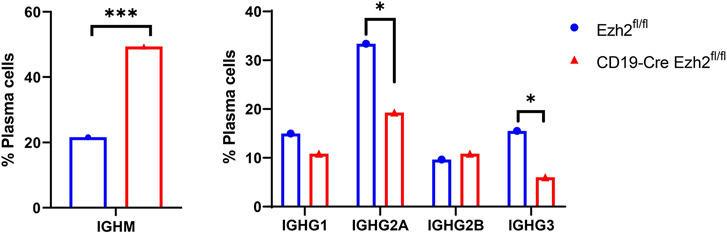

Upon T cell priming, B cells will undergo an intrachromosomal DNA recombination process to change the immunoglobulin (Ig) heavy chain constant region, a process called class switch recombination (CSR), to better protect against pathogens. IgM or IgD isotypes can be replaced by IgG, IgA, or IgE through CSR without altering antigen specificity (38). Dysregulation of CSR can lead to autoimmunity (39). We performed single-cell BCR sequencing, and integrated the results with scRNA-seq-defined clusters to investigate whether CSR was affected with EZH2 deficiency in B cells. We found different Ig heavy chain isotype distribution across the two mouse groups (Supplementary Figure 9). Specifically, IGHM (immunoglobulin heavy constant mu) which defines the IgM isotype was significantly higher, and IGHGs (immunoglobulin heavy constant gamma) including IGHG2A and IGHG3, which encode IgG2a and IgG3, respectively, were significantly lower in the plasma cells from CD19 Cre-Ezh2fl/fl mice compared to Ezh2fl/fl control mice (Figure 6). This implies that IGHM switching to IGHGs was impaired. These results suggest that EZH2 deficiency inhibits IGHM class switch recombination (CSR), resulting in the accumulation of IGHM and decreased IGHG isotypes in MRL/lpr mice.

Figure 6. Single-cell B cell receptor (BCR) sequencing of splenic B cells from Ezh2fl/fl and CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice.

Percentage of plasma cells with IGHM and IGHG isotypes out of all plasma cells expressing heavy chain genes (plasma cell n=1518 in Ezh2fl/fl mice and n=166 in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl). * p<0.05, ***p<0.001, Fisher’s exact test of normalized cell frequencies in plasma cells.

Discussion

We found that MRL/lpr mice with EZH2 deficiency in B cells developed less severe lupus-like phenotypes, including lowered levels of serum autoantibodies and proteinuria, and improved glomerulonephritis. B cell differentiation into ASCs was inhibited with EZH2 deficiency, possibly in part as a result of XBP1 downregulation. In addition, class switch recombination appears to be defective in MRL/lpr mice with EZH2 deficiency in B cells.

B cells play an important role in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases, including lupus. B cell targeting therapies, such as BAFF inhibitors, are successfully used in the treatment of lupus and lupus-related renal involvement (40). EZH2 is a key epigenetic regulator that is critically involved in B cell development and differentiation (41). We found that EZH2 deficiency significantly decreased total splenic B cell populations, and inhibited the differentiation of ASCs. These data provided supporting evidence that EZH2 is indispensable for peripheral B cell development. At the same time, memory B cells were significantly increased in EZH2-deficient MRL/lpr lupus-prone mice. In NP-CGG25-36 (4-Hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetyl-Chicken Gamma Globulin) immunized mice models, both GC B cell and memory B cell formation were impaired by EZH2 inactivation (42), which is contrary to what we observed in lupus-like MRL/lpr mice. This discrepancy may be because antigen exposure is consistent in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice compared to one-time immunization models. Our data suggest that in MRL/lpr mice, EZH2 deficiency possibly results in inefficient differentiation of memory B cells into GC B cells and plasmablasts/plasma cells, explaining accumulation and therefore increased numbers of memory B cells. However, recent evidence suggests that differentiation of memory B cells into GC B cells is a rare event (43). Therefore, an alternative explanation of our findings might be that EZH2 deficiency impairs the relative proportion of activated B cells that differentiate into memory B cells versus plasmablasts/plasma cells. Furthermore, some memory B cells in the CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl model may arise from activated B cells in the follicle in GC-independent way (44), which were not reduced by EZH2 deficiency in our model.

Our data demonstrated downregulation of XBP1 in EZH2-deficient B cells, which is a key transcription factor that mediates B cell differentiation (45). This suggest that the effect of EZH2 deficiency upon the differentiation of B cells could be at least partly mediated through XBP1 reduction. Indeed, we demonstrate similar effects on B cell differentiation in MRL/lpr mice, ex vivo, with an XBP1 inhibitor. We also demonstrate a strong positive correlation between mRNA expression levels of EZH2 and XBP1 in human lupus B cells. How EZH2 regulates transcription factor XBP1 needs more investigation. Zhang et al. showed that EZH2 epigenetically suppresses BACH2 expression in human CD19+ cells from healthy donors, resulting in increased expression of downstream PRDM1 and XBP1 (17). In our scRNA-seq data, the expression of BACH2 in B cell clusters was not affected by Ezh2 deletion. Therefore, our data suggest that XBP1 might be regulated by EZH2 through other mechanisms independent of the BACH2/PRDM1 axis.

Our data suggest that EZH2 might regulate other potential targets to promote the differentiation of GC B cells and ASCs, including marginal zone B and B1 cell specific protein (MZB1) and basic leucine zipper ATF-like transcription factor and (BATF), (Supplementary Table 4). MZB1 has been shown to be overexpressed in lymph nodes from lupus patients compared to healthy controls, and higher MZB1 mRNA levels in peripheral blood B cells were observed in active lupus patients compared to controls (46). Further, MZB1 mRNA levels were downregulated in a hepatocellular cancer cell line treated with an EZH2 inhibitor (47). Batf−/− mice demonstrated defective GC B cell differentiation and impaired CSR (48), similar to our findings in EZH2 deficient mice. EZH2 expression was shown to be induced by BATF/IRF4 complex and EBF1-PAX5-BACH2 pathway in plasma cells (49), implying a regulatory loop between EZH2 and BATF.

CSR happens before GC formation and also in the GC to switch IgD and IgM to IgG, IgA, and IgE isotypes (50). Our single-cell BCR sequencing suggests impaired ability of IGHM to switch to IGHGs in the plasma cells from CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice. Previous studies showed that IgG anti-dsDNA was positively correlated with glomerulonephritis in lupus patients, while IgM anti-dsDNA was protective from lupus nephritis in mouse models and negatively correlated with human glomerulonephritis (51, 52). This is consistent with our results in CD19-Cre Ezh2fl/fl mice.

We have previously demonstrated a pathogenic role for EZH2 in lupus CD4+ T cells (8). We showed that increased EZH2 expression in CD4+ T cells leads to increased T cell adhesion to endothelial cells in lupus. This effect is mediated by upregulation of the adhesion molecule JAM-A in lupus T cells (8). JAM-A is regulated by EZH2 and inhibiting either EZH2 or JAM-A restored normal T cell adhesion in lupus CD4+ T cells (8). In addition, recent findings implicated EZH2 in defective cytotoxicity in lupus CD8+ T cells, which helps to explain increased susceptibility to infections in lupus patients (53). Inhibiting EZH2 restores cytotoxicity in lupus CD8+ T cells, and therefore, has the potential to limit infections in lupus patients (53).

Besides its potential pathogenic roles in lupus, EZH2 has been found to be overexpressed in solid tumors or mutated to result in gain/loss of function in hematologic malignancies (54, 55). Therefore, inhibitors that target wild-type and mutant EZH2 have been developed. Recently, tazemetostat, an EZH2 inhibitor, was approved to treat advanced epithelioid sarcoma (54, 56). We have previously shown that a non-selective EZH2 inhibitor, DZNep, improves lupus-like disease in MRL/lpr mice (6). With a better understanding of the pathogenic effects EZH2 plays in lupus, repurposing EZH2 inhibitors to treat lupus in the future might be worth pursuing. Further, the identification of specific cell types, mechanisms, and EZH2-regulated genes involved can help the development of additional novel and more specific therapeutic targets in lupus.

In conclusion, EZH2 deficiency in B cells ameliorated lupus-like disease in MRL/lpr mice. EZH2 deficiency impeded B cell development and differentiation in the bone marrow and spleen. B cell Ezh2 deletion led to significant reduction in ASCs. Single-cell transcriptomics and in vitro data showed that XBP1 is a downstream target of EZH2 in MRL/lpr mice, and reduction in XBP1 might at least in part mediate the effects of EZH2 deficiency upon B cell development. CSR was also defective with EZH2 deficiency in B cells, possibly impairing pathogenic autoantibody production. Our results provided mechanistic evidence supporting targeting EZH2 as a potential novel therapeutic option for lupus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant number R01 AI097134. We are grateful to Dr. Mark Shlomchik for providing CD19-Cre MRL/lpr mice for our studies. We are also grateful to Dr. Sebastien Gingras of the Innovative Technologies Development Core (Department of Immunology, University of Pittsburgh) for his help with the design and identification of the Ezh2 floxed mouse on MRL/lpr background, as well as Dr. Chunming Bi and Zhaohui Kou of the Mouse Embryo Services Core (Department of Immunology, University of Pittsburgh) for microinjection of zygotes and production of the mice. We thank Joshua Michel and Valerie Miller in the Rangos Research Flow Core for their help with flow cytometry data analysis and sorting. We thank Tracy Tabib of the Single Cell Core for preparing single-cell sequencing libraries and help with data analysis. We thank Michele Mulkeen of the histology core for her help with tissue sectioning and staining. We also thank Luis Espinoza and Mckenna M. Bowes for helping to collect mouse tissues.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None of the authors report any relevant financial conflict of interest

References

- 1.Wu H, Zhao M, Tan L, Lu Q. The key culprit in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus: Aberrant DNA methylation. Autoimmunity reviews. 2016;15(7):684–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohan C, Putterman C. Genetics and pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11(6):329–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hedrich CM, Mabert K, Rauen T, Tsokos GC. DNA methylation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Epigenomics. 2017;9(4):505–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coit P, Jeffries M, Altorok N, Dozmorov MG, Koelsch KA, Wren JD, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation study suggests epigenetic accessibility and transcriptional poising of interferon-regulated genes in naive CD4+ T cells from lupus patients. J Autoimmun. 2013;43:78–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coit P, Dozmorov MG, Merrill JT, McCune WJ, Maksimowicz-McKinnon K, Wren JD, et al. Epigenetic Reprogramming in Naive CD4+ T Cells Favoring T Cell Activation and Non-Th1 Effector T Cell Immune Response as an Early Event in Lupus Flares. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(9):2200–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohraff DM, He Y, Farkash EA, Schonfeld M, Tsou PS, Sawalha AH. Inhibition of EZH2 Ameliorates Lupus-Like Disease in MRL/lpr Mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(10):1681–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCabe MT, Graves AP, Ganji G, Diaz E, Halsey WS, Jiang Y, et al. Mutation of A677 in histone methyltransferase EZH2 in human B-cell lymphoma promotes hypertrimethylation of histone H3 on lysine 27 (H3K27). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(8):2989–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsou PS, Coit P, Kilian NC, Sawalha AH. EZH2 Modulates the DNA Methylome and Controls T Cell Adhesion Through Junctional Adhesion Molecule A in Lupus Patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(1):98–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng X, Tsou PS, Sawalha AH. Increased Expression of EZH2 Is Mediated by Higher Glycolysis and mTORC1 Activation in Lupus CD4(+) T Cells. Immunometabolism. 2020;2(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhen Y, Smith RD, Finkelman FD, Shao WH. Ezh2-mediated epigenetic modification is required for allogeneic T cell-induced lupus disease. Arthritis Res Ther. 2020;22(1):133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu L, Jiang X, Qi C, Zhang C, Qu B, Shen N. EZH2 Inhibition Interferes With the Activation of Type I Interferon Signaling Pathway and Ameliorates Lupus Nephritis in NZB/NZW F1 Mice. Front Immunol. 2021;12:653989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ih Su, Basavaraj A, Krutchinsky AN, Hobert O, Ullrich A, Chait BT, et al. Ezh2 controls B cell development through histone H3 methylation and Igh rearrangement. Nature Immunology. 2003;4(2):124–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beguelin W, Popovic R, Teater M, Jiang Y, Bunting KL, Rosen M, et al. EZH2 is required for germinal center formation and somatic EZH2 mutations promote lymphoid transformation. Cancer Cell. 2013;23(5):677–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Domeier PP, Schell SL, Rahman ZS. Spontaneous germinal centers and autoimmunity. Autoimmunity. 2017;50(1):4–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandal M, Powers SE, Maienschein-Cline M, Bartom ET, Hamel KM, Kee BL, et al. Epigenetic repression of the Igk locus by STAT5-mediated recruitment of the histone methyltransferase Ezh2. Nature Immunology. 2011;12(12):1212–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo M, Price MJ, Patterson DG, Barwick BG, Haines RR, Kania AK, et al. EZH2 Represses the B Cell Transcriptional Program and Regulates Antibody-Secreting Cell Metabolism and Antibody Production. J Immunol. 2018;200(3):1039–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang M, Iwata S, Hajime M, Ohkubo N, Todoroki Y, Miyata H, et al. Methionine Commits Cells to Differentiate Into Plasmablasts Through Epigenetic Regulation of BTB and CNC Homolog 2 by the Methyltransferase EZH2. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(7):1143–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwata S, Yamaoka K, Niiro H, Jabbarzadeh-Tabrizi S, Wang SP, Kondo M, et al. Increased Syk phosphorylation leads to overexpression of TRAF6 in peripheral B cells of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2015;24(7):695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teichmann LL, Kashgarian M, Weaver CT, Roers A, Müller W, Shlomchik MJ. B cell-derived IL-10 does not regulate spontaneous systemic autoimmunity in MRL. Faslpr mice. The Journal of Immunology. 2012;188(2):678–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tilstra JS, John S, Gordon RA, Leibler C, Kashgarian M, Bastacky S, et al. B cell–intrinsic TLR9 expression is protective in murine lupus. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2020;130(6):3172–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stuart T, Butler A, Hoffman P, Hafemeister C, Papalexi E, Mauck WM 3rd, et al. Comprehensive Integration of Single-Cell Data. Cell. 2019;177(7):1888–902.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biology. 2004;5(10):R80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cross Benedict CS, Bond Peter J, Sadowski Pawel G, Jha Babal K, Zak J, Goodman Jonathan M, et al. The molecular basis for selective inhibition of unconventional mRNA splicing by an IRE1-binding small molecule. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109(15):E869–E78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hutcheson J, Scatizzi JC, Siddiqui AM, Haines GK, Wu T, Li Q-Z, et al. Combined Deficiency of Proapoptotic Regulators Bim and Fas Results in the Early Onset of Systemic Autoimmunity. Immunity. 2008;28(2):206–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker AM, Dao KH, Han BK, Kornu R, Lakhanpal S, Mobley AB, et al. SLE peripheral blood B cell, T cell and myeloid cell transcriptomes display unique profiles and each subset contributes to the interferon signature. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cerutti A, Cols M, Puga I. Marginal zone B cells: virtues of innate-like antibody-producing lymphocytes. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2013;13(2):118–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akkaya M, Kwak K, Pierce SK. B cell memory: building two walls of protection against pathogens. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2020;20(4):229–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathew NR, Jayanthan JK, Smirnov IV, Robinson JL, Axelsson H, Nakka SS, et al. Single-cell BCR and transcriptome analysis after influenza infection reveals spatiotemporal dynamics of antigen-specific B cells. Cell Rep. 2021;35(12):109286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palm A-KE, Kleinau S. Marginal zone B cells: From housekeeping function to autoimmunity? Journal of Autoimmunity. 2021;119:102627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laidlaw BJ, Duan L, Xu Y, Vazquez SE, Cyster JG. The transcription factor Hhex cooperates with the corepressor Tle3 to promote memory B cell development. Nat Immunol. 2020;21(9):1082–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhattacharya D, Cheah MT, Franco CB, Hosen N, Pin CL, Sha WC, et al. Transcriptional profiling of antigen-dependent murine B cell differentiation and memory formation. J Immunol. 2007;179(10):6808–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kallies A, Hasbold J, Tarlinton DM, Dietrich W, Corcoran LM, Hodgkin PD, et al. Plasma Cell Ontogeny Defined by Quantitative Changes in Blimp-1 Expression. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2004;200(8):967–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nguyen HTT, Guevarra RB, Magez S, Radwanska M. Single-cell transcriptome profiling and the use of AID deficient mice reveal that B cell activation combined with antibody class switch recombination and somatic hypermutation do not benefit the control of experimental trypanosomosis. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17(11):e1010026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen Y, Iqbal J, Xiao L, Lynch RC, Rosenwald A, Staudt LM, et al. Distinct gene expression profiles in different B-cell compartments in human peripheral lymphoid organs. BMC Immunol. 2004;5:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson SM, Tomayko MM, Ahuja A, Haberman AM, Shlomchik MJ. New markers for murine memory B cells that define mutated and unmutated subsets. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;204(9):2103–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ehrhardt GRA, Hijikata A, Kitamura H, Ohara O, Wang J-Y, Cooper MD. Discriminating gene expression profiles of memory B cell subpopulations. J Exp Med. 2008;205(8):1807–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malkiel S, Barlev AN, Atisha-Fregoso Y, Suurmond J, Diamond B. Plasma Cell Differentiation Pathways in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Front Immunol. 2018;9:427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roco JA, Mesin L, Binder SC, Nefzger C, Gonzalez-Figueroa P, Canete PF, et al. Class-Switch Recombination Occurs Infrequently in Germinal Centers. Immunity. 2019;51(2):337–50.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Durandy A, Kracker S. Immunoglobulin class-switch recombination deficiencies. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(4):218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee WS, Amengual O. B cells targeting therapy in the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunol Med. 2020;43(1):16–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nutt SL, Keenan C, Chopin M, Allan RS. EZH2 function in immune cell development. Biol Chem. 2020;401(8):933–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caganova M, Carrisi C, Varano G, Mainoldi F, Zanardi F, Germain PL, et al. Germinal center dysregulation by histone methyltransferase EZH2 promotes lymphomagenesis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(12):5009–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mesin L, Schiepers A, Ersching J, Barbulescu A, Cavazzoni CB, Angelini A, et al. Restricted Clonality and Limited Germinal Center Reentry Characterize Memory B Cell Reactivation by Boosting. Cell. 2020;180(1):92–106 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takemori T, Kaji T, Takahashi Y, Shimoda M, Rajewsky K. Generation of memory B cells inside and outside germinal centers. European Journal of Immunology. 2014;44(5):1258–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reimold AM, Iwakoshi NN, Manis J, Vallabhajosyula P, Szomolanyi-Tsuda E, Gravallese EM, et al. Plasma cell differentiation requires the transcription factor XBP-1. Nature. 2001;412(6844):300–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyagawa-Hayashino A, Yoshifuji H, Kitagori K, Ito S, Oku T, Hirayama Y, et al. Increase of MZB1 in B cells in systemic lupus erythematosus: proteomic analysis of biopsied lymph nodes. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2018;20(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu TP, Hong YH, Tung KY, Yang PM. In silico and experimental analyses predict the therapeutic value of an EZH2 inhibitor GSK343 against hepatocellular carcinoma through the induction of metallothionein genes. Oncoscience. 2016;3(1):9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ise W, Kohyama M, Schraml BU, Zhang T, Schwer B, Basu U, et al. The transcription factor BATF controls the global regulators of class-switch recombination in both B cells and T cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(6):536–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ochiai K, Kondo H, Okamura Y, Shima H, Kurokochi Y, Kimura K, et al. Zinc finger–IRF composite elements bound by Ikaros/IRF4 complexes function as gene repression in plasma cell. Blood Advances. 2018;2(8):883–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stavnezer J, Guikema JEJ, Schrader CE. Mechanism and Regulation of Class Switch Recombination. Annual Review of Immunology. 2008;26(1):261–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Förger F, Matthias T, Oppermann M, Becker H, Helmke K. Clinical significance of anti-dsDNA antibody isotypes: IgG/IgM ratio of anti-dsDNA antibodies as a prognostic marker for lupus nephritis. Lupus. 2004;13(1):36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Witte T. IgM Antibodies Against dsDNA in SLE. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 2008;34(3):345–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Katsuyama E, Suarez-Fueyo A, Bradley SJ, Mizui M, Marin AV, Mulki L, et al. The CD38/NAD/SIRTUIN1/EZH2 Axis Mitigates Cytotoxic CD8 T Cell Function and Identifies Patients with SLE Prone to Infections. Cell Rep. 2020;30(1):112–23 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eich M-L, Athar M, Ferguson JE III, Varambally S. EZH2-Targeted Therapies in Cancer: Hype or a Reality. Cancer Research. 2020;80(24):5449–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim KH, Roberts CWM. Targeting EZH2 in cancer. Nature Medicine. 2016;22(2):128–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zeng J, Zhang J, Sun Y, Wang J, Ren C, Banerjee S, et al. Targeting EZH2 for cancer therapy: From current progress to novel strategies. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2022;238:114419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.