Abstract

Background

The associations of oral contraceptive (OC) use with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and all‐cause death remains unclear. We aimed to determine the associations of OC use with incident CVD and all‐cause death.

Methods and Results

This cohort study included 161 017 women who had no CVD at baseline and reported their OC use. We divided OC use into ever use and never use. Cox proportional hazard models were used to calculate hazard ratios and 95% CIs for cardiovascular outcomes and death. Overall, 131 131 (81.4%) of 161 017 participants reported OC use at baseline. The multivariable‐adjusted hazard ratios for OC ever users versus never users were 0.92 (95% CI, 0.86–0.99) for all‐cause death, 0.91 (95% CI, 0.87–0.96) for incident CVD events, 0.88 (95% CI, 0.81–0.95) for coronary heart disease, 0.87 (95% CI, 0.76–0.99) for heart failure, and 0.92 (95% CI, 0.84–0.99) for atrial fibrillation. However, no significant associations of OC use with CVD death, myocardial infarction, or stroke were observed. Furthermore, the associations of OC use with CVD events were stronger among participants with longer durations of use (P for trend<0.001).

Conclusions

OC use was not associated with an increased risk of CVD events and all‐cause death in women and may even produce an apparent net benefit. In addition, the beneficial effects appeared to be more apparent in participants with longer durations of use.

Keywords: all‐cause death, cardiovascular disease, oral contraceptive use, women's health

Subject Categories: Cardiovascular Disease, Epidemiology, Women

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

Oral contraceptive use was associated with lower risk of all‐cause death, cardiovascular disease events, coronary heart disease, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation, but no significant associations were found for cardiovascular disease death, myocardial infarction, or stroke.

The beneficial effects of oral contraceptive use appeared to be more apparent in participants with longer durations of use.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Oral contraceptive use did not increase the risk of cardiovascular disease events and all‐cause death in the general population.

Women with oral contraceptive use throughout their reproductive life span may have a previously unrecognized protective factor for all‐cause death over time.

Oral contraceptives (OCs) are widely used as the contraception method in women of reproductive age worldwide. The risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) with the use of oral hormonal contraception is an important scientific issue. Previous studies have assessed the associations between OC use and the risk of CVD as well as all‐cause death, but have yielded inconsistent and even contradictory results. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Several clinical studies stated a slightly increased risk of CVD events with OCs. 6 , 7 , 8 In contrast, some studies reported that the use of OCs did not raise a woman's risk of subsequent CVD 9 and death, 10 whereas another study found that prior OC use was associated with lower longer‐term all‐cause and CVD death. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 Notably, previous evidence that use of OCs was associated with the risk of CVD events was mainly limited among users of second‐generation OCs, 17 , 18 whereas the risk of third‐generation OCs was still unclear. However, this evidence regarding the associations between OC use and the risk of CVD events is more limited and less inconclusive, with limited sample sizes. In particular, to our knowledge, prospective high‐quality evidence focusing on the relationships between OC use with CVD and death in the large‐scale general population is scarce.

Therefore, complementary information regarding the associations of OC use with CVD events and death is needed to investigate in real‐life settings of larger‐scale prospective studies and fill the knowledge gaps. In this prospective cohort study from UK Biobank, we aimed to examine the associations of OC use with the risk of CVD events, including coronary heart disease (CHD), myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure (HF), atrial fibrillation (AF), stroke, and CVD death as well as all‐cause death. Furthermore, we explored potential modifying factors that might affect these associations.

Methods

Publicly available data from the UK Biobank study were analyzed in this study. All data analyzed in this study are available to researchers through an open application via https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/register‐apply/.

Study Setting and Participants

The UK Biobank study design and population have been described in detail previously. 19 Briefly, between 2006 and 2010, the study recruited >500 000 participants, aged 40–69 years, from the general population at 22 assessment centers across England, Scotland, and Wales. 20 Participants completed a touchscreen questionnaire and a face‐to‐face interview containing health information and medical conditions. Various physical measurements were taken, and biological samples were also provided. Data from 502 490 participants were available for this study. Considering that the OC users were women, men (n=229 114) were then excluded from the study. We also excluded women who had a self‐reported or inpatient history of CVD (n=7069) at baseline assessment, had no available data on OC use (n=1418), used hormone‐replacement therapy (n=103 678), were pregnant (n=147), or withdrew the informed consent during the follow‐up (n=47). In total, 161 017 women were included in the current analysis (Figure S1).

The UK Biobank received ethical approval from the National Research Ethics Service North West Ethics Committee, Manchester, UK (REC reference for UK Biobank 21/NW/0157), and all participants provided informed consent.

Ascertainment of Exposure

The use of OCs was defined as ever or never use according to an electronic questionnaire when participants attended the UK Biobank cohort study. Participants were asked, “Have you ever taken the contraceptive pill? (including the ‘mini‐pill’)?” The answer options included “Yes,” “No,” “Do not know,” and “Prefer not to answer.” Participants who had answered “Do not know” or “Prefer not to answer” were excluded from all analyses.

Ascertainment of Outcomes

The main outcomes of the current study included the incidence of total CVD events, specific CVD events (CHD, MI, HF, AF, and stroke), CVD death, and all‐cause death. Data on hospital admissions were collected regularly through linkages to Health Episode Statistics (England), the Patient Episode Database (Wales), and the Scottish Morbidity Records (Scotland). Data on death were obtained from National Health Service Digital for participants in England and Wales and from the National Health Service Central Register, part of the National Records of Scotland, for participants in Scotland. For the analysis of cardiovascular outcomes and deaths, we censored follow‐up on November 30, 2020, or the date of death, whichever occurred first. Incident events and death outcomes were coded according to International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD‐10) codes: I20‐I25, I50, and I60 to I64 for CVD and CVD death; I20 to I25 for CHD; I21 to I23, I241, and I252 for MI; I50 for HF; I48 for AF; and I60 to I64 for stroke.

Ascertainment of Covariates

Information on sociodemographic factors (age, ethnicity [participants in UK Biobank were asked to define their own ethnicity (data‐field 21000) within the following major categories: “White,” “Mixed,” “Asian or Asian British,” “Black or Black British,” “Chinese,” or “Other ethnic group”; in view of the small numbers of people in the “non‐White” groups, our analyses use pooled self‐defined ethnicity groups of “White” or “Non‐White”], education, and household income), lifestyle (smoking status, drinking status, and physical activity), physical measurements (body mass index [BMI], systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure), medications (antihypertensive drug use, lipid‐lowering medication, and aspirin use), medical history (hypertension, diabetes, and stroke), and history of menstruation and fertility (menarche and parity) was obtained from the baseline questionnaire. BMI was calculated by dividing weight (kg) by height squared (m2). Biochemical measurements, including total cholesterol level, glycated hemoglobin, and C‐reactive protein, were measured at baseline. Further details of covariate measurements can be found in the UK Biobank online protocol (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Two‐sided P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Baseline characteristics are presented as mean±SD or median (interquartile range) for the continuous variables and number (percentage) for categorical variables. Multiple imputations with chained equations were performed for missing covariate data, assuming data were conditionally missing at random. 21 , 22 , 23 , 24

Baseline characteristics of study participants were compared among groups using general linear models for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. Cox proportional hazard models were used to calculate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for the associations between OC use and cardiovascular outcomes as well as death. Proportional hazards assumptions were checked by Schoenfeld residuals, Martingale residuals plots were used to evaluate linearity, and deviance residual plots were used to examine influential observations. The multivariable model (model 1) was adjusted for age. Model 2 was further adjusted for academic degree (university/college degree or others), ethnicity (White or others [others include Asian, Black, Chinese, Mixed and other (subjects categorized as “other” are those whose race or ethnicity was not categorized as White, mixed, Asian, Black, or Chinese, per the UK Biobank documentation)]), baseline systolic blood pressure, baseline diabetes (yes or no), baseline total cholesterol level, age at menarche, parity (0, 1, ≥2), family history of CVD or stroke (yes or no), menopause status (yes, no, hysterectomy, or other reason), aspirin use, lipid‐lowering medication use, and antihypertensive drug. Model 3 was additionally adjusted for smoking status (never, past, or current), drinking status (never, past, or current), BMI, and metabolic equivalent.

Stratified analyses were performed according to the duration of OC use into 4 intervals (≤1 year, 1–5 years, 5–10 years, or >10 years), 5 , 9 BMI (<30 kg/m2 or ≥30 kg/m2), current smoker (yes or no), physical activity (low, moderate, or high), parity (0, 1, or ≥2), age at menarche (<14 years or ≥14 years), age at OC use (≤18 years, 19–24 years, or 25–55 years), history of hypertension (yes or no), history of diabetes (yes or no), hypertriglyceridemia (yes or no), menstrual cycle (regular or irregular), and C‐reactive protein (<3.0 mg/dL, or ≥3.0 mg/dL). The potential effect modification was examined using the interaction models to investigate whether the associations between OC use and cardiovascular outcomes as well as death differed by these stratification variables. Sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding participants who developed CVD events during the first 2 years of follow‐up, including hormone replacement therapy users at baseline, and excluding those who were aged >60 years at baseline. In addition, we conducted further analyses after propensity score matching.

Patient and Public Involvement

No participants were involved in setting the study design, the outcome measures, the implementation of the study, or the interpretation of the results. No participants were invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this article.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the women stratified by OC use status (never users versus ever users). Of the 161 017 participants with a mean age of 53.5 years, 93.2% participants were White individuals, and 49.1% participants had university or college degrees. Overall, 131 131 (81.4%) reported OC use at baseline. Compared with never users, OC ever users were younger, had lower BMI, and were more likely to be current smokers. In addition, they had a higher rate of being current drinkers but a lower history of hypertension and diabetes. OC users were also less likely than never users to take aspirin, antihypertensive drugs, and lipid‐lowering medication.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of OC Ever Users and Never Users

| Overall (n=161 017) | Never users (n=29 886) | Ever users (n=131 131) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 53.5 (8.0) | 57.9 (8.6) | 52.5 (7.6) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity, White, % | 93.2 | 86.7 | 94.7 | <0.001 |

| Education, university or college degree, % | 49.1 | 40.8 | 51.0 | <0.001 |

| Income, % | <0.001 | |||

| <$52 000 | 71.7 | 84.6 | 69.1 | |

| $52000–$100 000 | 22.4 | 12.5 | 24.4 | |

| >$100 000 | 5.9 | 2.9 | 6.5 | |

| Smoking status, % | <0.001 | |||

| Never smoker | 63.5 | 72.5 | 61.5 | |

| Former smoker | 27.8 | 21.3 | 29.2 | |

| Current smoker | 8.7 | 6.3 | 9.3 | |

| Alcohol consumption, % | <0.001 | |||

| Never drinker | 6.0 | 14.3 | 4.1 | |

| Former drinker | 3.2 | 3.6 | 3.1 | |

| Current drinker | 90.8 | 82.1 | 92.8 | |

| Physical activity, % | <0.001 | |||

| Low | 54.8 | 56.7 | 54.4 | |

| Moderate | 21.0 | 19.1 | 21.4 | |

| High | 24.3 | 24.3 | 24.3 | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.9 (5.3) | 27.3 (5.5) | 26.8 (5.2) | <0.001 |

| Age at menarche, y | 13.0 (1.6) | 13.0 (1.6) | 13.0 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Parity | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.7 (1.4) | 1.8 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| History of hypertension, % | 18.2 | 25.1 | 16.7 | <0.001 |

| History of diabetes, % | 3.2 | 5.0 | 2.8 | <0.001 |

| Family history of CVD, % | 39.2 | 40.1 | 39.0 | <0.001 |

| Family history of stroke, % | 23.3 | 25.7 | 22.7 | <0.001 |

| Aspirin use, % | 6.2 | 9.1 | 5.5 | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive drug, % | 8.1 | 11.5 | 7.4 | <0.001 |

| Lipid‐lowering medication, % | 7.6 | 12.9 | 6.4 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.27 (0.93–1.78) | 1.38 (1.00–1.92) | 1.25 (0.91–1.74) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.82 (1.07) | 5.92 (1.12) | 5.79 (1.06) | <0.001 |

| LDL‐C, mmol/L | 3.59 (0.83) | 3.68 (0.87) | 3.57 (0.82) | <0.001 |

| HDL‐C, mmol/L | 1.59 (0.36) | 1.57 (0.36) | 1.59 (0.36) | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose, mmol/L | 4.91 (4.62–5.22) | 4.98 (4.68–5.32) | 4.89 (4.60–5.20) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as the mean (SD), median (interquartile range), or numbers (percentages). CVD indicates cardiovascular disease; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; and OC, oral contraceptive.

Table 2 shows the associations of OC use with the outcomes. During a median of 11.8 years follow‐up, 9672 participants developed CVD events, with 7590 (4.7%) derived from OC users; and 5970 participants developed death events, with 4204 (2.6%) derived from OC users. In the analyses, we found that OC use was significantly associated with the lower risks of all‐cause death and the incidence of CVD events, CHD, MI, HF, and AF after adjustment for age (all P<0.05). In the multivariable‐adjusted models (model 3), the adjusted HRs associated with OC use were 0.92 (95% CI, 0.86–0.99) for all‐cause death, 0.91 (95% CI, 0.87–0.96) for CVD events, 0.88 (95% CI, 0.81–0.95) for CHD, 0.87 (95% CI, 0.76–0.99) for HF, and 0.92 (95% CI, 0.84–0.99) for AF (all P<0.05). However, no significant associations of OC use with CVD death (HR, 0.94 [95% CI, 0.81–1.09]; P=0.400), MI (HR, 0.89 [95% CI, 0.76–1.03]; P=0.124), and stroke (HR, 1.03 [95% CI, 0.91–1.18]; P=0.625) were observed.

Table 2.

Associations of OC Use With the Risk of Cardiovascular Outcomes and All‐Cause Death

| Outcomes | Never users (n=29 886), n (%) | Ever users (n=131 131), n (%) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |||

| CVD | 3167 (10.6) | 7590 (5.8) | 0.87 (0.83–0.90) | <0.001 | 0.90 (0.86–0.94) | <0.001 | 0.91 (0.87–0.96) | 0.001 |

| CHD | 1535 (5.1) | 3709 (2.8) | 0.84 (0.79–0.89) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.82–0.93) | <0.001 | 0.88 (0.81–0.95) | <0.001 |

| CVD death | 465 (1.6) | 886 (0.7) | 1.05 (0.93–1.18) | 0.406 | 1.06 (0.93–1.19) | 0.433 | 0.94 (0.81–1.09) | 0.400 |

| All‐cause death | 1766 (5.9) | 4204 (3.2) | 0.90 (0.85–0.96) | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.87–0.98) | 0.011 | 0.92 (0.86–0.99) | 0.026 |

| MI | 393 (1.3) | 933 (0.7) | 0.84 (0.74–0.95) | 0.007 | 0.87 (0.76–0.99) | 0.030 | 0.89 (0.76–1.03) | 0.124 |

| HF | 601 (2.0) | 1078 (0.8) | 0.76 (0.68–0.84) | <0.001 | 0.84 (0.75–0.93) | 0.001 | 0.87 (0.76–0.99) | 0.043 |

| AF | 1289 (4.3) | 2649 (2.0) | 0.90 (0.84–0.96) | 0.003 | 0.92 (0.85–0.99) | 0.021 | 0.92 (0.84–0.99) | 0.049 |

| Stroke | 539 (1.8) | 1331 (1.0) | 0.93 (0.84–1.04) | 0.207 | 0.97 (0.87–1.08) | 0.522 | 1.03 (0.91–1.18) | 0.625 |

Model 1: adjusted for age. Model 2: further adjusted for academic degree (university/college degree or others), ethnicity (White or others), baseline systolic blood pressure, baseline diabetes (yes or no), and baseline total cholesterol level, age at menarche, parity (0, 1, or ≥2), family history of CVDs (others include CVD, CHD, HF, AF, and MI) or stroke (yes or no), menopause status (yes, no, hysterectomy, or other reason), aspirin use (yes or no), lipid‐lowering medication (yes or no), antihypertensive drug (yes or no). Model 3: additionally adjusted for smoking status (never, past, or current), drinking status (never, past, or current), BMI, and metabolic equivalent. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; MI, myocardial infarction; and OC, oral contraceptive.

In addition, we conducted stratified analyses according to the durations of OC use (Table 3). Compared with the OC never users, individuals with a duration of OC use for >5 years were significantly associated with lower risks of all‐cause death, CVD events, CHD, and HF in the multivariable‐adjusted models, and those with a duration of OC use of 1 to 5 years were significantly associated with lower risks of CHD (P for trend<0.05). In addition, those with a duration of OC use of >10 years were significantly associated with lower risks of AF (P for trend<0.05). No significant associations between OC use and CVD death, MI, or stroke were observed according to the duration of OC use (all P for trend>0.05). Likewise, no significant associations between OC use and incident CVD events as well as death were observed among individuals with a duration of OC use of <5 years (both P for trend<0.05).

Table 3.

HRs for Risk of Cardiovascular Outcomes and All‐Cause Death According to the Duration of Contraceptive Use

| Never users (n=29 886) | ≤1 y (n=12 015) | 1–5 y (n=23 248) | 5–10 y (n=29 713) | >10 y (n=66 155) | P for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVD | ||||||

| No. of events | 3167 | 1010 | 1581 | 1703 | 3296 | |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.90–1.07) | 0.94 (0.87–1.01) | 0.91 (0.85–0.98) | 0.87 (0.81–0.93) | <0.001 |

| CHD | ||||||

| No. of events | 1535 | 500 | 737 | 833 | 1639 | |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.82–1.05) | 0.87 (0.78–0.97) | 0.88 (0.79–0.97) | 0.86 (0.78–0.94) | <0.001 |

| CVD death | ||||||

| No. of events | 465 | 120 | 160 | 184 | 422 | |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.12 (0.87–1.44) | 0.97 (0.77–1.21) | 0.89 (0.71–1.10) | 0.89 (0.75–1.06) | 0.109 |

| All‐cause death | ||||||

| No. of events | 1766 | 515 | 851 | 897 | 1941 | |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.85–1.08) | 0.94 (0.86–1.04) | 0.87 (0.79–0.96) | 0.92 (0.84–0.99) | 0.023 |

| MI | ||||||

| No. of events | 393 | 114 | 176 | 214 | 429 | |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.88 (0.69–1.13) | 0.85 (0.69–1.05) | 0.90 (0.73–1.10) | 0.91 (0.76–1.08) | 0.351 |

| HF | ||||||

| No. of events | 601 | 164 | 224 | 212 | 478 | |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.79–1.20) | 0.87 (0.72–1.05) | 0.79 (0.65–0.96) | 0.89 (0.76–0.99) | 0.033 |

| AF | ||||||

| No. of events | 1289 | 353 | 610 | 597 | 1089 | |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.91 (0.79–1.05) | 0.99 (0.88–1.12) | 0.93 (0.83–1.05) | 0.85 (0.77–0.95) | 0.009 |

| Stroke | ||||||

| No. of events | 539 | 188 | 273 | 280 | 590 | |

| HR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.20 (0.98–1.47) | 1.09 (0.92–1.30) | 0.95 (0.79–1.13) | 0.98 (0.85–1.15) | 0.392 |

HRs were adjusted for age, academic degree (university/college degree or others), ethnicity (White or others), baseline systolic blood pressure, baseline diabetes (yes or no) and baseline total cholesterol level, age at menarche, parity (0, 1, or ≥2), family history of CVDs (others include CVD, CHD, HF, AF, and MI) or stroke (yes or no), menopause status (yes, no, hysterectomy, or other reason), aspirin use (yes or no), lipid‐lowering medication (yes or no), antihypertensive drug (yes or no), smoking status (never, past, or current), drinking status (never, past, or current), body mass index, and metabolic equivalent. AF indicates atrial fibrillation; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; and MI, myocardial infarction.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

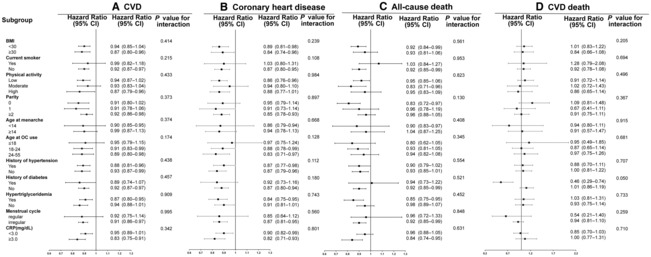

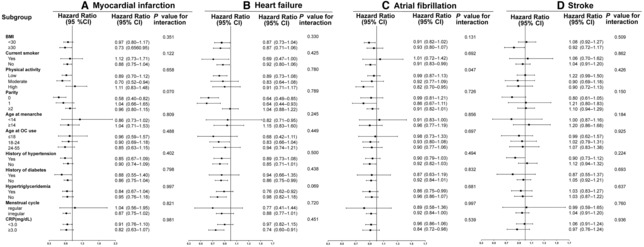

Subgroup analyses were conducted according to potential risk factors (Figures 1 and 2). No significant interactions on risks of CVD events (Figure 1A), CHD (Figure 1B), all‐cause death (Figure 1C), CVD death (Figure 1D), MI (Figure 2A), HF (Figure 2B), and stroke (Figure 2D) were observed between OC use with BMI, smoking status, physical activity levels, parity, age at menarche, age at OC use, history of hypertension, history of diabetes, hypertriglyceridemia, menstrual cycle, or C‐reactive protein (all P for interaction>0.05). However, the association of OC use with AF (Figure 2C) was stronger among participants with more active physical activity (P for interaction=0.047).

Figure 1. Subgroup analysis for the associations between OC use and risk of CVD events (A), coronary heart disease (B), all‐cause death (C), and CVD death (D).

Analyses were conducted with a multiple imputation approach for missing data. OC never users are included as referent (1.00). Hazard ratios were adjusted for age, academic degree (university/college degree or others), ethnicity (White or others), baseline systolic blood pressure, baseline diabetes (yes or no), baseline total cholesterol level, age at menarche, parity (0, 1, or ≥2), family history of cardiovascular diseases or stroke (yes or no), menopause status (yes, no, hysterectomy, or other reason), aspirin use (yes or no), lipid‐lowering medication (yes or no), antihypertensive drug (yes or no), smoking status (never, past, or current), drinking status (never, past, or current), BMI, and metabolic equivalent. BMI indicates body mass index; CRP, C‐reactive protein; CVD, cardiovascular disease; and OC, oral contraceptive.

Figure 2. Subgroup analysis for the associations between OC use and risk of myocardial infarction (A), heart failure (B), atrial fibrillation (C), and stroke (D).

Analyses were conducted with a multiple imputation approach for missing data. OC never users are included as referent (1.00). Hazard ratios were adjusted for age, academic degree (university/college degree or others), ethnicity (White or others), baseline systolic blood pressure, baseline diabetes (yes or no), baseline total cholesterol level, age at menarche, parity (0, 1, or ≥2), family history of cardiovascular diseases or stroke (yes or no), menopause status (yes, no, hysterectomy, or other reason), aspirin use (yes or no), lipid‐lowering medication (yes or no), antihypertensive drug (yes or no), smoking status (never, past, or current), drinking status (never, past, or current), BMI, and metabolic equivalent. BMI indicates body mass index; CRP, C‐reactive protein; and OC, oral contraceptive.

Sensitivity analyses showed no substantial change when we excluded participants who developed CVD events during the first 2 years of follow‐up, including hormone replacement therapy users (Tables S1 and S2). When excluding OC users aged >60 years at baseline, the results showed that OC use was significantly associated with lower risks of all‐cause death, the incidence of CVD events, CHD, and HF (all P<0.05) (Table S3). Regarding this case, we further conducted stratified analyses according to the duration of OC use and showed similar results (Table S4). Table S5 shows baseline characteristics of OC ever users and never users after propensity score matching. Compared with the OC never users, individuals with OC use were associated with lower risks of all‐cause death, CVD events, CHD, MI, HF, and AF in the multivariable‐adjusted models (all P<0.05; Table S6). There were no significant associations between OC use and CVD death or stroke (P=0.619 and P=0.128, respectively; Table S6).

Discussion

In the large prospective study of 161 017 participants, we provide new evidence that OC use was not associated with an increased risk of CVD events and all‐cause death in women. The results showed that OC use reduced a 9% risk of CVD events and an 8% risk of all‐cause death. Furthermore, our findings indicated that OC use reduced an 8% to 13% lower risk of CHD, HF, and AF. These associations were independent of traditional risk factors, including age, ethnicity, education, income, smoking status, alcohol intake, metabolic equivalent, BMI, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, drug use, C‐reactive protein, and other supplement use. In addition, we observed that decreased CVD events as well as all‐cause death with longer durations of OC use. Besides, we found that the inverse association of OC use with AF were significantly modified by physical activity.

Comparison With Other Studies

Although numerous studies have assessed the association between OC use and the risk of CVD events as well as death, the results are inconsistent and even contradictory. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Previous clinical studies reported that OC use was associated with a slightly increased risk of CVD events. 6 , 7 , 8 A prospective study of 119 061 nurses found that the use of OCs did not materially raise the risk of subsequent CVD. 9 Graff‐Iversen et al 10 reported that CVD risk was not elevated in 29 053 women with use of OCs during a 14‐year follow‐up. In contrast, the Women's Health Initiative study showed that OC use was associated with significant CVD risk reductions in 161 089 women, especially among those whose duration of OC use was >1 year. 16 Another cohort study also found that low‐dose estrogen combined OCs were associated with a lower risk of CVD events in 5 million French women. 25 However, these studies did not provide conclusive information on the associated risk of CVD events and death in the large‐scale general population. Our findings showed that OC use was associated with a 9% lower risk of CVD events, and the association was significantly modified by the duration of OC use. In addition, we found that OC use was associated with an 8% lower risk of all‐cause death. Consistently, previous studies also reported that OC users had a significantly lower rate of all‐cause death 26 , 27 or may not increase the risk of death in the prospective cohort study with 36 years’ follow‐up. 5 These findings support that OC use is safe for women of reproductive age and may even produce an apparent net benefit.

Regarding specific types of CVD outcomes, our findings demonstrated that OC use was not associated with MI. Consistently, Dunn et al 2 found no association between OC use and MI among 448 women in a case–control study. However, Victory and colleagues 16 reported that OC use was associated with a lower risk of MI in women with a history of OC use. In contrast, other prospective cohort studies found that OC use was not associated with an increased risk of MI. 28 Also, a previous study reported that OCs were not a typical atherogenic risk factor. 15 In addition, we observed that OC use was not associated with a 13% lower risk of HF. In consistent with our findings, the results from the Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation showed that past OC use is associated with a lower risk of CHD among postmenopausal women with suspected myocardial ischemia. 29 Moreover, our findings showed that OC use was associated with a 13% lower risk of HF. The Multi‐Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis assessed the association of OC use and incident HF in 3594 women and reported no overall increase in the risk of HF with OC use. 30

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the relationship between OC use and AF. Our data showed that OC use was associated with an 8% lower risk of AF. In addition, the results indicated that there was no association between OC use and stroke. A study from the French national health insurance database showed that OCs combining an estrogen dose of 20 μg versus 30 to 40 μg was associated with lower risks of ischemic stroke and MI. 25 These findings may imply that OC use in women of reproductive age does not portend an increased risk of specific types of CVD outcomes. Furthermore, these findings suggest that OC use may be beneficial to the prevention of CVD events in women of reproductive age. However, these associations appear to be modified by the duration of OC use and the dosage of estrogen. 1 Future studies are needed to determine the appropriate formulations or dosages of OCs on CVD outcomes.

Biological Plausibility

Several potential mechanisms could explain the observed relationships between OC use and the incidence of CVD as well as death. First, OCs are mainly a combination of different formulations and doses of estrogen and progestin. OC use is significantly related to multiple CVD risk factors, including lipoproteins, blood pressure, glucose tolerance, and diabetes. 31 The effects of OC use on serum lipid profiles primarily result from estrogen‐receptor–mediated effects on the hepatic expression of apoprotein genes. 12 , 32 , 33 Estrogen reduces low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol oxidation and binding and platelet aggregation, and increases cyclooxygenase‐2 activity. 12 Clinical studies also showed that some types of OCs produced lower blood pressure and no adverse effects on glucose. 34 , 35 Second, OC administration can directly prevent atherosclerosis in animal models, 13 , 36 , 37 which is the leading cause of subsequent CVD events. Accordingly, this may be another mechanism that could explain the benefits for CVD events derived from OC use. In addition, OC has evolved through time and begun to more closely resemble endogenous molecules, which may further decrease thrombotic effects. 38 , 39 Consistently, our analysis showed that OC use did not increase the risk of subsequent CVD events, and the risk may decrease when the duration of OC use is >1 year.

In addition, OCs help to ameliorate countless ailments, including dysmenorrhea, fibroid‐related symptoms, acne, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Extensive evidence showed that disruption of ovulatory cycling, indicated by estrogen deficiency and hypothalamic dysfunction, or irregular menstrual cycling in premenopausal women may increase the risk of coronary atherosclerosis and CVD events. 40 , 41 , 42 Therefore, OC use may be beneficial for CVD events since it plays a protective role in improving the above reproductive disorders. In light of death analyses, OC use can reduce the risks of uterine body cancer, ovarian cancer, and maternal death. 43 Indeed, other mechanisms might also be involved. Future investigations are needed to explore the functional roles and mechanisms of OC use in cardiovascular health.

Strengths and Limitations of this Study

Our study has several strengths, including the large sample size of UK Biobank participants, the prospective population‐based design, and the long‐time follow‐up, which provided enough cases of CVD outcomes and death and adequate support for sufficient statistical power. Besides, the wealthy information on socioeconomic characteristics, lifestyle habits, history of menstruation and fertility, comorbidity, medication, and other covariates was available, which enhanced the validity of the conclusions through adjustments for multiple potential confounding factors in our study.

Several limitations should also be considered in the present study. First, the UK Biobank did not record detailed information on the use of OCs, such as the formulation and dose. Therefore, it is difficult to evaluate dose–response associations between OC use and CVD outcomes as well as death, and assess whether the effects of various formulations of OCs on outcomes might differ. Second, although a series of known potential confounders have been adjusted in our analyses, we cannot completely exclude the possibility of residual confounders in the present study. Third, it is difficult to distinguish the effects of lifestyle and comorbidity from the use of OCs in determining the risks of CVD outcomes and death in an observational study. Thus, potential reverse causality might exist in the current study. Fourth, most of the UK Biobank participants were White people (93.2%); therefore, our findings cannot be generalized to other ethnic populations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings suggest that OC use was not associated with an increased risk of CVD events and all‐cause death in women and may even produce an apparent net benefit. In addition, the beneficial effects appeared to be more apparent in participants with longer durations of use (>5 year). These findings provide significant public health insights and may facilitate a shift in public perception because OC use is common in women of reproductive age, and previously negative publicity exists about the safety of OC use. Future studies are needed to determine the appropriate formulations or dosages of OCs on CVD outcomes in larger‐scale prospective studies.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project (No. 2018YFA0800404), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81970736), the Joint Funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U22A20288), and Key‐Area Clinical Research Program of Southern Medical University (No. LC2019ZD010 and 2019CR022). The funders of the study had no role in the study design, conduct, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, approval of the manuscript, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S6

Figure S1

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted using the UK Biobank resource under application 68376. We are grateful to the participants of UK Biobank. Dr H. Zhang had full access to all of the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs W. Dou and H. Zhang designed the study. Drs W. Dou, Y. Huang, X. Liu, and C. Huang conducted the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in the interpretation of the results and critical revision of the manuscript.

This manuscript was sent to Mahasin S. Mujahid, PhD, MS, FAHA, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.123.030105

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 9.

Contributor Information

Changqin Liu, Email: liuchangqin@126.com.

Huijie Zhang, Email: huijiezhang2005@126.com.

References

- 1. Lidegaard Ø, Løkkegaard E, Jensen A, Skovlund CW, Keiding N. Thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction with hormonal contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2257–2266. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1111840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dunn N, Lidegaard Ø, Thorogood M, Faragher B, de Caestecker L, MacDonald TM, McCollum C, Thomas S, Mann R. Oral contraceptives and myocardial infarction: results of the MICA case‐control study commentary: oral contraceptives and myocardial infarction: reassuring new findings. BMJ. 1999;318:1579–1584. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7198.1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carmina E. Oral contraceptives and cardiovascular risk in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol Investig. 2013;36:358–363. doi: 10.3275/8882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Karlsson T, Johansson T, Höglund J, Ek WE, Johansson Å. Time‐dependent effects of oral contraceptive use on breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancers. Cancer Res. 2021;81:1153–1162. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-2476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Charlton BM, Rich‐Edwards JW, Colditz GA, Missmer SA, Rosner BA, Hankinson SE, Speizer FE, Michels KB. Oral contraceptive use and mortality after 36 years of follow‐up in the Nurses' Health Study: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2014;349:g6356. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Roach REJ, Helmerhorst FM, Lijfering WM, Stijnen T, Algra A, Dekkers OM. Combined oral contraceptives: the risk of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2018:CD011054. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011054.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Acute myocardial infarction and combined oral contraceptives . Results of an international multicentre case‐control study. WHO Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Lancet. 1997;349:1202–1209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02358-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ge S, Tao X, Cai L, Deng X, Hwang M, Wang C. Associations of hormonal contraceptives and infertility medications on the risk of venous thromboembolism, ischemic stroke, and cardiovascular disease in women. J Investig Med. 2019;67:729–735. doi: 10.1136/jim-2018-000750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH. A prospective study of past use of oral contraceptive agents and risk of cardiovascular diseases. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1313–1317. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811173192004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Graff‐Iversen S, Hammar N, Thelle DS, Tonstad S. Use of oral contraceptives and mortality during 14 years' follow‐up of Norwegian women. Scand J Public Health. 2006;34:11–16. doi: 10.1080/14034940510032239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barsky L, Shufelt C, Lauzon M, Johnson BD, Berga SL, Braunstein G, Bittner V, Shaw L, Reis S, Handberg E, et al. Prior Oral contraceptive use and longer term mortality outcomes in women with suspected ischemic heart disease. J Women's Health. 2021;30:377–384. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mendelsohn ME, Karas RH. The protective effects of estrogen on the cardiovascular system. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1801–1811. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906103402306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Adams MR, Clarkson TB, Shively CA, Parks JS, Kaplan JR. Oral contraceptives, lipoproteins, and atherosclerosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:1388–1393. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91353-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaplan JR, Adams MR, Anthony MS, Morgan TM, Manuck SB, Clarkson TB. Dominant social status and contraceptive hormone treatment inhibit atherogenesis in premenopausal monkeys. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:2094–2100. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.15.12.2094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Engel H‐J, Engel E, Lichtlen PR. Coronary atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction in young women—role of oral contraceptives. Eur Heart J. 1983;4:1–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a061365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Victory R, D'Souza C, Diamond MP, McNeeley SG, Vista‐Deck D, Hendrix S. Adverse cardiovascular disease outcomes are reduced in women with a history of oral contraceptive use: results from the women's health initiative database. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:S52–S53. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.07.135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tanis BC, Helmerhorst FM. Oral contraceptives and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2001;7:1787–1793. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Spitzer WO. Oral contraceptives and cardiovascular outcomes: cause or bias? Contraception. 2000;62:S3–S9. doi: 10.1016/S0010-7824(00)00149-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J, Downey P, Elliott P, Green J, Landray M, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Collins R. What makes UK Biobank special? Lancet. 2012;379:1173–1174. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60404-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Millett ERC, Peters SAE, Woodward M. Sex differences in risk factors for myocardial infarction: cohort study of UK Biobank participants. BMJ. 2018;363:k4247. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huang C, Wei K, Lee PMY, Qin G, Yu Y, Li J. Maternal hypertensive disorder of pregnancy and mortality in offspring from birth to young adulthood: national population based cohort study. BMJ. 2022;379:e072157. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-072157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Romaniuk H, Patton GC, Carlin JB. Multiple imputation in a longitudinal cohort study: a case study of sensitivity to imputation methods. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180:920–932. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, Wood AM, Carpenter JR. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weill A, Dalichampt M, Raguideau F, Ricordeau P, Blotière P‐O, Rudant J, Alla F, Zureik M. Low dose oestrogen combined oral contraception and risk of pulmonary embolism, stroke, and myocardial infarction in five million French women: cohort study. BMJ. 2016;353:i2002. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hannaford PC, Iversen L, Macfarlane TV, Elliott AM, Angus V, Lee AJ. Mortality among contraceptive pill users: cohort evidence from Royal College of General Practitioners' Oral Contraception Study. BMJ. 2010;340:c927. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vessey M, Yeates D, Flynn S. Factors affecting mortality in a large cohort study with special reference to oral contraceptive use. Contraception. 2010;82:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Margolis KL, Adami H‐O, Luo J, Ye W, Weiderpass E. A prospective study of oral contraceptive use and risk of myocardial infarction among Swedish women. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Merz CNB, Johnson BD, Berga S, Braunstein G, Reis SE, Bittner V; WISE Study Group . Past oral contraceptive use and angiographic coronary artery disease in postmenopausal women: data from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute‐sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1425–1431. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Luo D, Li H, Chen P, Xie N, Yang Z, Zhang C. Association between oral contraceptive use and incident heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2021;8:2282–2292. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shufelt CL, Bairey Merz CN. Contraceptive hormone use and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jones DR, Schmidt RJ, Pickard RT, Foxworthy PS, Eacho PI. Estrogen receptor‐mediated repression of human hepatic lipase gene transcription. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:383–391. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2275(20)30144-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sitruk‐Ware RL, Menard J, Rad M, Burggraaf J, de Kam ML, Tokay BA, Sivin I, Kluft C. Comparison of the impact of vaginal and oral administration of combined hormonal contraceptives on hepatic proteins sensitive to estrogen. Contraception. 2007;75:430–437. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Suthipongse W, Taneepanichskul S. An open‐label randomized comparative study of oral contraceptives between medications containing 3 mg drospirenone/30 μg ethinylestradiol and 150 μg levonogestrel/30 μg ethinylestradiol in Thai women. Contraception. 2004;69:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2003.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oelkers W, Foidart JM, Dombrovicz N, Welter A, Heithecker R. Effects of a new oral contraceptive containing an antimineralocorticoid progestogen, drospirenone, on the renin‐aldosterone system, body weight, blood pressure, glucose tolerance, and lipid metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:1816–1821. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.6.7775629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Knowlton AA, Lee AR. Estrogen and the cardiovascular system. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;135:54–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Adams MR, Anthony MS, Manning JM, Golden DL, Parks JS. Low‐dose contraceptive estrogen‐progestin and coronary artery atherosclerosis of monkeys. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:250–255. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00891-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dragoman MV. The combined oral contraceptive pill‐ recent developments, risks and benefits. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28:825–834. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2014.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Peragallo Urrutia R, Coeytaux RR, McBroom AJ, Gierisch JM, Havrilesky LJ, Moorman PG, Lowery WJ, Dinan M, Hasselblad V, Sanders GD, et al. Risk of acute thromboembolic events with oral contraceptive use: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:380–389. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182994c43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Noel Bairey Merz C, Johnson BD, Sharaf BL, Bittner V, Berga SL, Braunstein GD, Hodgson TK, Matthews KA, Pepine CJ, Reis SE, et al. Hypoestrogenemia of hypothalamic origin and coronary artery disease in premenopausal women: a report from the NHLBI‐sponsored WISE study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:413–419. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02763-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Solomon CG, Hu FB, Dunaif A, Rich‐Edwards JE, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Manson JE. Menstrual cycle irregularity and risk for future cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2013–2017. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Snell‐Bergeon JK, Dabelea D, Ogden LG, Hokanson JE, Kinney GL, Ehrlich J, Rewers M. Reproductive history and hormonal birth control use are associated with coronary calcium progression in women with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2142–2148. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ahmed S, Li Q, Liu L, Tsui AO. Maternal deaths averted by contraceptive use: an analysis of 172 countries. Lancet. 2012;380:111–125. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60478-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S6

Figure S1