Abstract

Background

Niacin-derived nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide is an essential cofactor for many dehydrogenase enzymes involved in vitamin A (VA) metabolism. Several countries with high prevalence of VA deficiency rely on maize, a poor source of available niacin, as a dietary staple.

Objectives

This study evaluated the interaction of dietary niacin on VA homeostasis using male Sprague-Dawley rats, aged 21 d (baseline body weight 88.3 ± 6.6 g).

Methods

After 1 wk of acclimation, baseline samples were collected (n = 4). Remaining rats (n = 54) were split into 9 groups to receive low tryptophan, VA-deficient feed with 3 different amounts of niacin (0, 15, or 30 mg/kg) and 3 different oral VA doses (50, 350, or 3500 nmol/d) in a 3 × 3 design. After 4 wk, the study was terminated. Serum, livers, and small intestine were analyzed for retinoids using high-performance liquid chromatography. Niacin and metabolites were evaluated with nuclear magnetic resonance. Plasma pyridoxal-P (PLP) was measured with high-performance liquid chromatography.

Results

Niacin intake correlated with serum retinol concentrations (r = 0.853, P < 0.001). For rats receiving the highest VA dose, liver retinol concentrations were lower in the 30-mg/kg niacin group (5.39 ± 0.27 μmol/g) than those in the 0-mg/kg and 15-mg/kg groups (9.18 ± 0.62 and 8.75 ± 0.07 μmol/g, respectively; P ≤ 0.05 for both). This phenomenon also occurred in the lower VA doses (P ≤ 0.05 for all). Growth and tissue weight at endline were associated with niacin intake (P ≤ 0.001 for all). Plasma PLP correlated with estimated niacin intake (r = 0.814, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Optimal niacin intake is associated with lower liver VA and higher serum retinol and plasma PLP concentrations. The extent to which vitamin B intake affects VA homeostasis requires further investigation to determine if the effects are maintained in humans.

Keywords: niacin, nutrient interactions, pyridoxal-P, small intestine, vitamin A

Introduction

Vitamin A (VA) deficiency affects an estimated 200 million children and women in the Americas, Southeast Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa [1]. The WHO estimates that Zambia has severe VA deficiency based on ≥20% of children presenting with serum retinol concentrations of <0.7 μmol/L; however, 59% of a cohort of rural Zambian children were determined to have hypervitaminosis A by sensitive retinol isotope dilution testing [2,3]. Zambia has many interventions to address VA deficiency, including high-dose VA supplements for children aged <5 years, fortification of common staple foods, such as sugar and cooking oil, and biofortification of orange maize and sweet potato with enhanced provitamin A carotenoids. The overlap of these interventions likely causes excessive VA intake in some groups, which may lead to hypervitaminosis A [4,5]. Typical VA intake of these children indicated adequate intake and not excessive [6], suggesting that other factors contributed to the documented hypervitaminosis A.

Zambia relies on maize as a dietary staple, providing >50% of available energy in the food supply [7]. Maize is naturally a poor source of available niacin and tryptophan, the latter of which can partially meet niacin needs by enzymatic conversion to NAD [8]. Analysis of food records from Zambian children revealed that <40% consumed a diet adequate in niacin equivalents [9]. Studies feeding niacin-restricted diets have demonstrated that rat tissue and human erythrocyte NAD+ concentrations decrease within 1 wk [10,11]. In addition, only 22%–40% of these Zambian children consumed adequate amounts of vitamin B-6 [9], which is concerning because PLP, the active form of vitamin B-6, is an essential cofactor for kynureninase [12,13], and the rate-limiting step for enzymatic conversion of tryptophan to NAD. Furthermore, low serum vitamin B-6 concentrations were determined in 79% of the children, reported as serum PLP <20 nmol/L [3]. Therefore, inadequate intakes of vitamin B-6 and niacin and low serum PLP may have altered NAD concentrations in these Zambian children.

Studies in mice demonstrated that knocking out the dehydrogenase enzymes in the VA metabolic pathway leads to enhanced sensitivity to hypervitaminosis A [14]. Several of these enzymes require NAD+ as an essential cofactor, reducing it to NADH (Figure 1). Flux through the VA metabolic pathway is partially influenced by cofactor supply [15]. Large doses of VA acutely shifted the liver NAD+:NADH ratio in favor of the reduced form in rats [16]. Increased cellular NADH inhibited VA metabolism in a model developed to mimic in vivo conditions [17]. Therefore, we hypothesized that impaired niacin status can disrupt flux through the VA pathway leading to elevated liver VA. The objective of this work was to determine the effect of inadequate niacin intake on VA homeostasis in rats to inform VA intervention programs in Zambia and other maize-consuming countries.

FIGURE 1.

A schematic of the pathway of vitamin A metabolism. CYP26, cytochrome P450 26; LRAT, lecithin:retinol acyltransferase; RALDH, retinaldehyde dehydrogenase; RDH, retinol dehydrogenase; REH, retinyl ester hydrolase; SDR, short-chain dehydrogenase/reductases.

Methods

Rat feed

Three custom feeds were developed to be VA-free, low tryptophan, and have 3 different concentrations of added niacin (0, 15, and 30 mg/kg) (Supplemental Table 1). The basal feed contained 7% casein and added essential amino acids (except tryptophan) to balance the amino acid profile. Additional synthetic amino acids were included to meet needs and avoid complications of an imbalanced amino acid profile potentially caused by alternative low tryptophan sources, such as gelatin [11]. Additional tryptophan was not included to restrict the amount available for conversion to NAD. Previous work demonstrated that 7% casein feed without additional niacin will not support niacin status in rats [11]. The NRC indicates that 15 mg added niacin/kg feed will be sufficient to prevent deficiency in rats consuming feed with adequate tryptophan [18]; therefore, 15 mg/kg in diets having inadequate tryptophan may not completely meet niacin needs. Standard AIN-93 laboratory rat feed contains 30 mg/kg added niacin [19]; thus, the 3 experimental feeds were considered: deficient dietary niacin (DN; 0 mg/kg), marginally deficient dietary niacin (MN; 15 mg/kg), and adequate dietary niacin (AN; 30 mg/kg). Feed was analytically confirmed to be VA free.

The VA doses were retinyl acetate dissolved in soybean oil (∼100 μL) and administered orally each day by positive displacement pipet. To maintain liver retinol concentrations in the low VA group, daily needs were estimated to be met with 50 nmol/d with minimal storage [18]. To achieve liver retinol concentrations of 1 μmol/g, similar to those observed in Zambian children [3], a daily dose of 350 nmol/d was estimated to meet this threshold. Finally, to achieve very high liver VA stores, 3500 nmol/d was administered.

Rats

Weanling male Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 58) aged 21 d (Charles River Laboratories) were triple-housed in plastic shoebox cages during 1-wk acclimation in which they had ad libitum access to VA-deficient feed and water. Rats were weighed daily. Room temperature and humidity were held constant with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. This protocol was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s College of Agricultural and Life Sciences Animal Care and Use Committee.

Study design

After 1 wk, rats (n = 4) were subjected to baseline measures and killed by cardiac puncture with a syringe while under isoflurane anesthesia. Large rats were selected for baseline measures to ensure adequate sample collection. Blood was collected into serum separator tubes and lithium heparin plasma tubes. Tissues were collected and snap frozen. The remaining rats (n = 54) were moved to wire bottom cages to reduce coprophagy, which could affect niacin recycling. The rats were randomly assigned by cage in a 3 × 3 design to 9 groups of 6 rats and assigned to one of 3 different niacin-fortified feeds (0, 15, and 30 mg/kg) and to one of 3 different oral VA dosage regimens (50, 350, and 3500 nmol/d) (Supplemental Figure 1). After 28 d of treatment, blood was collected under anesthesia, and tissues were harvested.

Serum and liver retinoids and histologic evaluation

Serum and liver analyses were adapted from published procedures [20]. For serum, 250-μL ethanol was added to 200-μL serum to denature proteins; 100-μL C23-β-apo-carotenol was added as an internal standard prior to 3 extractions with 500 μL hexanes. Hexanes were dried under nitrogen and residue redissolved in 100 μL of 75:25 methanol:dichloroethane before injection onto the HPLC. Liver (0.6 g) was ground with 3 g anhydrous sodium sulfate and C23-β-apo-carotenol, extracted repeatedly with dichloromethane, and filtered into a 50-mL volumetric flask. An aliquot was dried under nitrogen and redissolved in 100 μL of 75:25 methanol:dichloroethane; 50 μL was injected into a Waters Resolve C18 column (5 μm, 3.9 × 300 mm) equipped with a guard column on the HPLC. The mobile phases were acetonitrile:water (95:5, vol:vol; solvent A) and acetonitrile:methanol:dichloroethane (80:10:10, vol:vol:vol; solvent B), both containing 10 mmol/L ammonium acetate. Samples were analyzed at 2 mL/min using a published gradient: 1) 100% A for 3 min, 2) 7-min linear gradient to 100% B, 3) 12-min hold, and 4) 2-min reverse gradient to 100% A [21]. Chromatograms were generated at 325 nm to quantify retinol and retinyl esters.

A subset of liver samples (n = 18 from treatments and 1 baseline) was sent for histologic evaluation. Prepared slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or Masson trichrome to evaluate collagen content. Slides were evaluated by a pathologist blinded to group allocation and a report generated.

Plasma PLP

Plasma PLP was analyzed using a published procedure [22] with minor modifications. Plasma proteins were precipitated with 0.5 mL 10% trichloroacetic acid while mixing by vortex and centrifuged. The supernatant was extracted twice with 3 mL diethyl ether and once with 3 mL dichloromethane. A 100-μL aliquot was injected. The semicarbazone derivative was analyzed by a reverse-phase fluorometric HPLC equipped with a dual pump system for mobile phase delivery and postcolumn alkalinization with 4% NaOH (wt:vol) to enhance fluorescence. A Jasco fluorescence detector was used (excitation wavelength: 367 nm; emission wavelength: 478 nm). The flow rates were 1.1 and 0.1 mL/min for the solvent and postcolumn reagent pumps, respectively.

NMR metabolite profile

Analysis of niacin-related metabolites was adapted from a published procedure [23]. Two grams mechanically separated frozen liver or small intestine or 0.6 mL packed erythrocytes were homogenized (T10 ULTRA-TURRAX; IKA) in 2 mL ice-cold methanol and 425 μL ice-cold water by 30-s pulses over 2 min. After mixing by vortex for 10 s, 1 mL cold chloroform was added, and the sample mixed for 30 s, placed on ice for 15 min, and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 15 min at 4°C to generate 3 phases. The polar metabolites in the top methanol/water phase were collected and dried for 1 h with a speed vacuum concentrator at 45°C. For small intestine, the chloroform and tissue layers were kept for further analysis.

The dried polar fractions were solubilized by adding 600-μL buffer (100 mmol/L sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, in D2O, containing 0.5 mmol/L 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid [DSS] and 0.4% NaN3). The solutions were transferred to 5-mm NMR tubes and kept at −20°C prior to acquiring spectra. All spectra were recorded at 25°C on a Bruker Advance III 600 MHz spectrometer (operating at 600.08 MHz for 1H) equipped with a cryogenic probe (QCI). The 1H NMR water signal from the polar fraction was suppressed by means of excitation sculpting. All 1H NMR spectra were the means of 256 transients acquired with 32K points, an acquisition time of 1.70 s, and a repetition delay of 2 s between transients. The chemical shifts of the polar fractions were referenced to DSS peak at 0.0 ppm. Spectra were manually phased and baseline corrected using Bruker Topspin 3.5.7 software. Metabolites were identified using the Chenomx NMR Suite 8.3 (Chenomx) relative to DSS as an internal standard. NAD+, NAD (phosphate), oxidized form [NAD(P)+], niacinamide, and tryptophan concentrations in liver, small intestine, and erythrocytes were assessed. Liver ATP, kynurenine, 3-hydroxykynurenine, creatinine, and 3-methylhistidine concentrations were evaluated from spectral data.

Small intestine retinoids

The chloroform layer from the small intestine extract was transferred to a glass tube for a modified extraction procedure [24]. Ethanol (1.5 mL; 0.025 mol/L KOH) and 1-mL deionized water were added to the remaining homogenized tissue to extract nonpolar and polar retinoids. Internal standard C23-β-apo-carotenol was added, and the samples were mixed by vortex. Nonpolar retinoids were extracted with 1-mL hexanes; samples were vortexed and centrifuged. The hexane layer was collected and pooled with the chloroform, and the extraction was repeated. To extract retinoic acid, 160-μL HCl (4 mol/L) was added to each sample, followed by 2 hexane extractions. The combined hexanes and chloroform extracts were dried under nitrogen, redissolved in 100 μL 75:25 methanol:dichloroethane, and 50 μL was injected onto the HPLC system equipped with a Waters Sunfire C18 column (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm) [25]. The mobile phases were methanol:water (70:30, vol:vol; solvent A) and methanol:dichloroethane (80:20, vol:vol; solvent B), both containing 10 mmol/L ammonium acetate. Samples were analyzed at 0.9 mL/min using a published gradient: 1) 100% A initial conditions, 2) 20-min linear gradient to 100% B, 3) 20-min hold, and 4) 1-min reverse gradient to 100% A and hold for 9-min prior to the next injection. Chromatograms were generated at 325 nm to quantify retinoids.

Statistical analysis

All values are reported as means ± SD. Values for the NMR metabolites are relative concentration (mmol/L) to the DSS internal standard. Data were analyzed using the PROC MIXED statement in the Statistical Analysis System software (SAS Institute, version 9.4). Mixed models were performed with fixed effects for niacin, the VA dose, and the interaction. Models included a random effect for the treatment allocation. The LSMEANS statement with the Tukey-Kramer method was used for multiple group comparisons of treatment groups. For variables of interest with uneven intercage variance, as evidenced by Levene test P ≤ 0.05, a REPEATED statement was included. The SLICE function was included to assess the effect of different amounts of dietary niacin on variables of interest within each VA dose group when an interaction occurred. One-factor ANOVAs were performed to compare treatment values with baseline using the LSMEANS statement with the Dunnett correction. For variables where only the factor for dietary niacin was significant, the variable for VA and the interaction were dropped, and 1-factor ANOVA was used to assess the effect of niacin on the variable of interest. The Proc Corr statement was used to compare trends in variables of interest with Spearman correlation coefficients. All analyses were conducted with 2-sided tests (α = 0.05).

Results

Rat growth and physical appearance

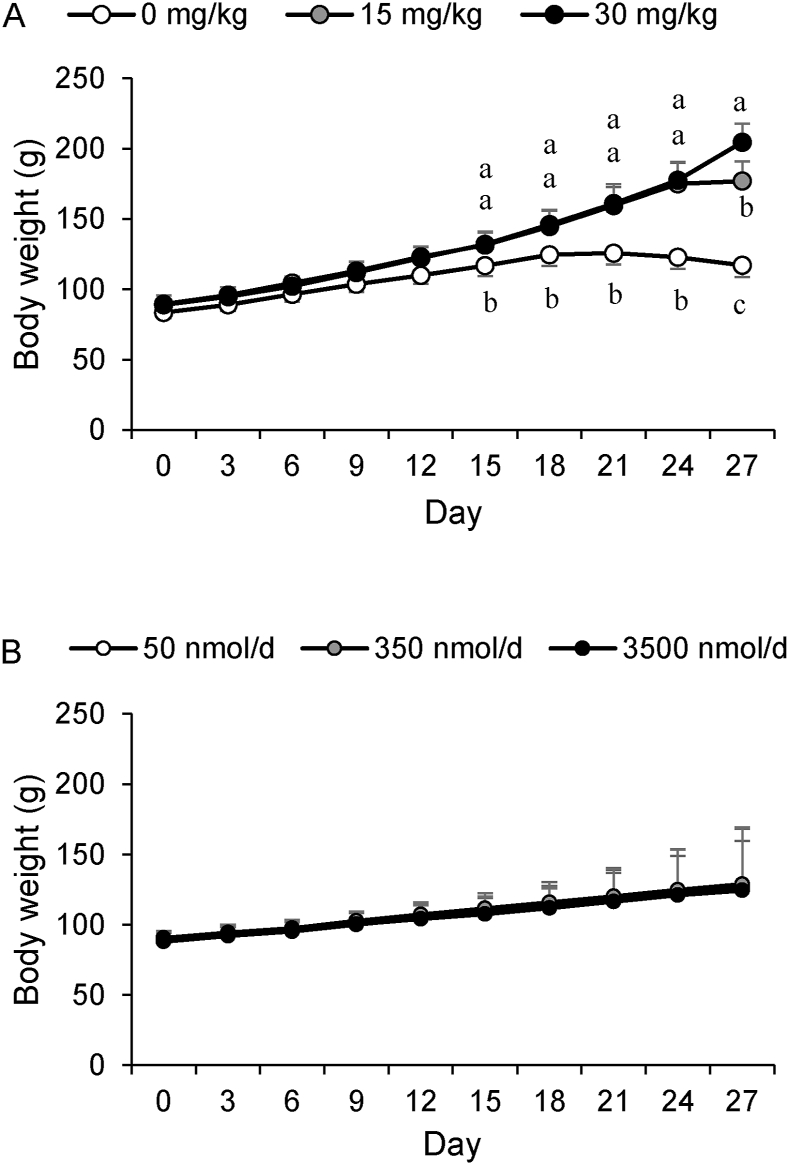

Growth was significantly affected by dietary niacin (P < 0.0001) (Figure 2A) but not by VA dose amount (P = 0.66) (Figure 2B) or the interaction with niacin (P = 0.28). By 21 d, the rats consuming the DN feed stopped gaining weight (Figure 2A). At day 27 (1 d earlier than planned), the DN groups were killed because weight loss was 10% from peak weight. In addition to the smaller mass, these rats were secreting porphyrin, which first appeared by 13 d. At 21 d, the DN rats showed signs of behavioral change (aggression and lethargy) and feed avoidance (Table 1). By 21 d, the MN groups had porphyrin staining around the eyes, nose, and ears, but it did not progress further by the end of the study, and no behavior change was observed. The AN groups did not show adverse effects. Feed, estimated niacin equivalents, and estimated pyridoxine intakes were significantly affected by dietary niacin treatment (P ≤ 0.001) (Table 1). The amount of dietary niacin significantly affected mean liver and small intestine weights (P < 0.001 for both), but only liver weight was affected by the VA dose (P = 0.008) and the interaction with niacin (P < 0.001) (Table 1). This relationship is further demonstrated by the strong correlations between the estimated intake of dietary niacin and end of study body weight (r = 0.89, P < 0.001), liver weight (r = 0.87, P < 0.001), and small intestine weight (r = 0.74, P < 0.001).

FIGURE 2.

Rat growth curves: (A) Effect of dietary niacin on rat growth (P < 0.0001 for end of study mean weights). (B) Effect of vitamin A dosage amount on rat growth (P = 0.66 for end of study weights). Differing letters indicate significance at P < 0.05, determined by 2-factor ANOVA with an interaction statement mean comparisons by LSMEANS with Tukey-Kramer correction.

TABLE 1.

Body and organ weights and feed intake for combined dietary niacin amount groups1

| Baseline | Dietary niacin amount (mg/kg)2 |

P3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 15 | 30 | |||

| Rats (n) | 4 | 18 | 18 | 18 | — |

| Baseline body weight (g)4 | 103 ± 1.00 | 83.8 ± 4.03† | 88.5 ± 3.27† | 91.6 ± 6.66† | 0.083 |

| Final body weight (g)4 | — | 112 ± 8.77c | 177 ± 14.1b,† | 205 ± 13.4a,† | <0.0001 |

| Liver weight (g)∗ | 7.8 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 0.6c,† | 5.2 ± 0.9b,† | 9.6 ± 0.8a,† | <0.0001 |

| Liver (% body weight)∗ | 7.7 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.5b,† | 3.0 ± 0.4b,† | 4.7 ± 0.5a,† | <0.0001 |

| Small intestine weight (g) | 5.0 ± 1.0 | 4.4 ± 0.6c | 5.3 ± 0.8b | 6.1 ± 0.7a,† | <0.0001 |

| Small intestine (% body weight) | 4.9 ± 1.0 | 3.9 ± 0.5a,† | 3.0 ± 0.5b,† | 3.0 ± 0.3b,† | <0.0001 |

| Estimated feed intake (g/rat/d) | NA5 | 45.5 ± 2.8c | 55.7 ± 6.4b | 62.3 ± 4.7a | <0.0001 |

| Estimated total niacin equivalent intake (μg/rat)6 | NA5 | 31.6 ± 1.9c | 60.4 ± 6.9b | 91.8 ± 7.0a | <0.0001 |

| Estimated pyridoxine intake (μg/cage) | NA5 | 8.28 ± 0.5b | 10.1 ± 1.2a | 11.3 ± 0.9a | <0.0001 |

All values are mean ± SD. Values in rows with superscripts without common letter differ, P < 0.05, determined by LSMEANS with Tukey-Kramer correction.

Significant values (P < 0.05) compared with baseline determined by LSMEANS with Dunnett correction.

Groups are combined so that 3 different VA dose amounts are within each niacin amount. VA did not significantly affect growth or intake unless denoted by asterisk (∗), which indicates significant effect of VA dosages (P < 0.05).

P values for treatment effect of the dietary niacin amount determined by 1-factor ANOVA with Dunnett correction.

Body weight was not monitored during acclimation; reported weight was collected at baseline.

Feed intake was not monitored during the acclimation period; therefore, intake of niacin and vitamin B-6 were not estimated.

Niacin equivalents estimated by multiplying total feed intake niacin concentration for each group and by adding the converted tryptophan by dividing total tryptophan intake from feed by a conversion factor of 30 (18).

Similarly, the percentage that liver or small intestine weight contributed to total body weight was significantly affected by niacin treatment (P ≤ 0.001 for both). The liver as a percentage of total body weight was affected by the VA dose (P < 0.001) and the interaction (P = 0.006). The AN groups had significantly higher percentage body weight from the liver compared with the DN and MN groups (P ≤ 0.001). For the small intestine, the DN groups had a higher percentage of body weight from the small intestine compared with the AN and MN groups (P ≤ 0.001) (Table 1). Strong correlations existed between liver and body weights (r = 0.86, P ≤ 0.001), small intestine and body weights (r = 0.79, P < 0.001), and liver and small intestine weights (r = 0.63, P < 0.001).

Serum retinol and retinyl esters

Serum retinol concentrations were significantly different among groups by the amount of dietary niacin and VA dose and the interaction (P < 0.001 for each) (Table 2). The amount of dietary niacin significantly affected serum retinol concentrations such that the AN groups had higher serum retinol concentrations than the DN groups within each VA dosage group.

TABLE 2.

Serum and tissue retinol concentrations and total tissue amount in rats fed 3 different amounts of dietary niacin and receiving 3 different daily doses of retinyl acetate1

| Treatment2 | Serum retinol (μmol/L) | Serum total retinyl ester (μmol/L) | Percentage retinyl ester of serum total VA | Liver retinol (μmol/g) | Liver total retinol (μmol)3 | Small intestine (nmol/g) | Small intestine total retinol (nmol)3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 2.05 ± 0.09 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.92 ± 0.21 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.69 ± 0.08 | 0.91 ± 0.33 | 4.69 ± 2.32 |

| 50 nmol | |||||||

| 0 mg/kg | 1.04 ± 0.15d,† | 0.06 ± 0.05c | 5.23 ± 4.30d | 0.22 ± 0.04e | 0.76 ± 0.16f | 2.15 ± 1.51cd | 8.61 ± 5.61c |

| 15 mg/kg | 2.12 ± 0.26a | 0.02 ± 0.01c | 1.15 ± 0.51d | 0.15 ± 0.05f | 0.81 ± 0.13f | 1.18 ± 0.28d | 6.54 ± 1.34c |

| 30 mg/kg | 2.59 ± 0.40a | 0.03 ± 0.01bc | 1.12 ± 0.15d | 0.08 ± 0.01g | 0.80 ± 0.07f | 0.96 ± 0.21d | 5.93 ± 1.26c |

| 350 nmol | |||||||

| 0 mg/kg | 1.19 ± 0.32cd,† | 0.05 ± 0.02b | 4.18 ± 1.94c | 0.98 ± 0.11c,† | 3.66 ± 0.81e | 4.97 ± 1.90bc | 22.9 ± 9.35c |

| 15 mg/kg | 1.89 ± 0.39b | 0.04 ± 0.02bc | 2.30 ± 1.25d | 0.92 ± 0.05c,† | 4.98 ± 0.92d | 12.6 ± 7.58b | 61.3 ± 41.3c |

| 30 mg/kg | 2.31 ± 0.13a | 0.05 ± 0.02bc | 2.00 ± 0.80d | 0.60 ± 0.05d | 5.67 ± 0.32c | 6.33 ± 1.35b | 39.6 ± 9.03c |

| 3500 nmol | |||||||

| 0 mg/kg | 1.51 ± 0.38bc | 0.62 ± 0.26a,† | 39.4 ± 9.93a,† | 9.18 ± 0.73a,† | 36.3 ± 8.42b,† | 188 ± 79.3a,† | 859 ± 341b,† |

| 15 mg/kg | 2.32 ± 0.35a | 0.41 ± 0.12a,† | 18.4 ± 6.31b,† | 8.75 ± 0.70a,† | 41.4 ± 6.34b,† | 229 ± 53.4a,† | 1230 ± 286ab,† |

| 30 mg/kg | 2.70 ± 0.62a,† | 0.62 ± 0.31a,† | 21.8 ± 7.06b,† | 5.39 ± 0.63b,† | 52.3 ± 6.21a,† | 287 ± 121a,† | 1700 ± 672a,† |

| P4 | |||||||

| Niacin | <0.0001 | 0.042 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | NS | 0.07 |

| VA | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Interaction | 0.01 | 0.013 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.024 | 0.038 |

All values are mean ± standard deviation. Differing letters in columns indicate significance at P < 0.05 determined by 2-factor ANOVA (excluding baseline) with LSMEANS and TUKEY-KRAMER correction. †Significance at P < 0.05 compared with baseline values determined by 1-factor ANOVA with LSMEANS and Dunnet correction.

Treatments are 3 amounts of VA dosage (50, 350, and 3500 nmol/d) by 3 different amounts of dietary niacin (0, 15, and 30 mg/kg) in a 3 × 3 design.

Total retinol calculated by multiplying retinol concentration by organ weight for each rat. Liver and small intestine weight were significantly affected by niacin treatment (Table 1).

Treatment effect P values are from a 2-factor ANOVA that does not include the baseline group.

The percentage that retinyl esters contributed to total serum VA concentrations was also significantly affected by amount of dietary niacin, VA dose, and the interaction (P < 0.001 for each) (Table 2). However, the within VA group effect of niacin was only significant in the higher 2 VA dose groups such that the AN and MN groups had a lower percentage of serum total VA as retinyl esters. Because total serum retinol concentrations differed, absolute serum retinyl ester concentrations were assessed (Table 2). Ester concentrations were significantly affected by the VA dose (P < 0.0001) and to a lesser degree by niacin (P = 0.042) and the interaction (P = 0.013). Estimated niacin intake was positively correlated with serum retinol concentrations (r = 0.770, P < 0.001) but not with percentage esters (r = −0.060, P = 0.89) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Correlation coefficients between niacin intake, tissue and serum retinol, and plasma PLP concentrations1

| Estimated niacin intake | Serum retinol (μmol/L) | Serum retinyl esters (μmol/L) | Liver retinol (μmol/g) | Small intestine retinol (nmol/g) | Plasma PLP (nmol/g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated niacin intake | 1.00 | 0.770∗∗ | −0.060 | −0.315∗ | −0.068 | 0.800∗∗ |

| Serum retinol | — | 1.00 | 0.137 | −0.109 | 0.098 | 0.708∗∗ |

| Serum retinyl esters | — | — | 1.00 | 0.755∗∗ | 0.716∗∗ | −0.073 |

| Liver retinol | — | — | — | 1.00 | 0.896∗∗ | −0.279∗ |

| Small intestine retinol | — | — | — | — | 1.00 | −0.028 |

| Plasma PLP | — | — | — | — | — | 1.00 |

Values are Spearman correlation coefficients: ∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.0001.

Tissue retinoids and histology

Liver retinol concentrations were significantly different among the groups by the of dietary niacin, VA dose, and the interaction (P < 0.001 for each). The within VA group effect of niacin was significant such that within each VA dose amount, the AN group had lower liver retinol concentrations than the DN group (Table 2). Similarly, total liver retinol was predicted by niacin, VA dose, and the interaction (P < 0.001 for each). However, because of the different liver sizes among groups at endline (Table 1), the AN group had the highest total liver retinol within the 350-nmol/d and 3500-nmol/d VA dosage groups (Table 2).

In the small intestine, only the VA dose (P < 0.001) and the interaction with niacin (P = 0.024) predicted retinol concentrations. Similar to liver, small intestine weight was different among the niacin intake amounts (Table 1), and the AN group had higher total liver retinol within the 3500-nmol/d VA dosage group (Table 2). Retinoic acid was not quantifiable.

Estimated niacin intake was associated with liver retinol concentrations (r = −0.315, P = 0.03) but not small intestine retinol concentrations (r = −0.068, P = 0.90) (Table 3) even though liver and small intestine retinol concentrations were correlated (r = 0.896, P < 0.001). Liver retinol concentration also correlated with serum total retinyl esters (r = 0.755, P < 0.001) (Figure 3A) and the percentage serum retinyl esters of total VA (r = 0.896, P < 0.001) (Figure 3B) but not with serum total retinol (Figure 3C). Small intestine retinol concentration correlated with serum total retinyl esters (r = 0.716, P < 0.001) and percentage serum retinyl esters of total VA (r = 0.833, P < 0.001). Serum retinol concentration was not correlated with liver retinol concentration (r = −0.109, P = 0.43) and small intestine retinol concentration (r = 0.098, P = 0.48) but was correlated with serum retinyl esters (r = 0.739 and r = 0.716 for percentage and total, respectively; P < 0.001 for both).

FIGURE 3.

Scatterplots and Spearman correlations of liver retinol concentrations with (A) serum total retinyl esters (r = 0.857, P < 0.0001), (B) percentage retinyl esters of serum total retinol (r = 0.896, P < 0.0001), and (C) serum total retinol (r = −0.109, P = 0.43).

Several abnormal findings were noted in the histology of the slides. Four rat livers were considered to be lipid laden with stellate cell hypertrophy and increased collagen (Figure 4). The mean retinol concentration of these rat livers was 8.90 ± 1.06 μmol/g. In 1 rat with a value of 4.7 μmol/g liver, multiple stellate cells were swollen, but the collagen appeared normal. In VA-deficient rats with a mean liver VA concentration of 0.10 ± 0.046 μmol/g, increased collagen, necrosis, and cystic degeneration were noted (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Histology of representative livers (scale bar is 200 μm). The panels on the left are hematoxylin and eosin staining and those on the right are the corresponding trichrome staining for collagen: (A) A vitamin A–deficient rat (0.092 μmol/g liver) with widespread necrosis and cystic degeneration noted in the hematoxylin and esosin staining. The corresponding trichrome revealed thickened collagen consistent with fibrosis (white arrows). (B) A rat with an adequate amount of vitamin A (0.29 μmol/g liver) revealed normal histology and collagen findings. (C) A rat with a toxic amount of vitamin A (7.85 μmol/g liver) was lipid laden with stellate cell hypertrophy noted in the hematoxylin and esosin staining as white circles in the field of view and collagen tendrils extending into the parenchyma (white arrows).

NMR metabolite profile

The relative concentration of liver NAD+ was not affected by the amount of dietary niacin in liver, erythrocytes, or the small intestine (P > 0.05 for all) (Table 4). Liver NAD(P)+ was not affected by the amount of dietary niacin; however, niacin did significantly affect NAD(P)+ in erythrocytes and the small intestine (P ≤ 0.01 for both). In the small intestine, the AN group had significantly higher NAD(P)+ than the DN group (P ≤ 0.05). In the erythrocyte, both the AN and MN groups had significantly higher NAD(P)+ than the DN group (P ≤ 0.05 for both).

TABLE 4.

Relative concentration of metabolites identified by NMR in rats fed differing amounts of dietary niacin1

| Metabolite relative concentration (mM) | Baseline | Dietary niacin amount |

P2 | P3,∗ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 mg/kg | 15 mg/kg | 30 mg/kg | ||||

| Liver | ||||||

| NAD+ | 0.16 ± 0.04 | 0.22 ± 0.15 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | NS | NS |

| NAD(P)+ | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 0.17 ± 0.05 | 0.09 | NS |

| Niacinamide | 1.07 ± 0.28 | 1.48 ± 0.34a | 1.32 ± 0.45ab | 1.12 ± 0.26b | 0.02 | 0.006 |

| ATP4 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.06b | 0.14 ± 0.06ab | 0.16 ± 0.06a,† | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Tryptophan | 0.16 ± 0.04 | 0.28 ± 0.09a,† | 0.22 ± 0.08b | 0.19 ± 0.05b | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Kynurenine | 0.21 ± 0.08 | 0.25 ± 0.02a | 0.22 ± 0.04ab | 0.17 ± 0.02b | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| 3-Hydroxy-kynurenine | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.11 ± 0.09 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | NS | NS |

| Creatinine | 0.46 ± 0.17 | 1.00 ± 0.32a,† | 0.77 ± 0.19b | 0.53 ± 0.13c | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| 3-Methylhistidine | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.03a,† | 0.08 ± 0.03ab | 0.07 ± 0.03b | 0.048 | 0.02 |

| Small intestine | ||||||

| NAD+ | 0.016 ± 0.012 | 0.009 ± 0.009 | 0.008 ± 0.006 | 0.008 ± 0.005 | NS | NS |

| NAD(P)+ | 0.004 ± 0.000 | 0.003 ± 0.002b | 0.004 ± 0.001ab | 0.005 ± 0.002a | 0.003 | 0.005 |

| Niacinamide | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.03b,† | 0.38 ± 0.02a,† | 0.39 ± 0.03a,† | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Tryptophan4 | 0.65 ± 0.06 | 0.76 ± 0.15 | 0.89 ± 0.15 | 0.73 ± 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| Erythrocyte | ||||||

| NAD+ | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.05 | NS | NS |

| NAD(P)+ | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01b,† | 0.02 ± 0.01a | 0.02 ± 0.01a | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Niacinamide4 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.03 ± 0.02b,† | 0.05 ± 0.02a | 0.07 ± 0.03a | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Tryptophan | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | NS | NS |

Values are mean ± standard deviation.

Treatment effect of dietary niacin amount determined by 1-factor ANOVA (excludes baseline group). Rows with differing letters indicate significance (P < 0.05) determined by LSMEANS with Tukey-Kramer correction.

Treatment effect of dietary niacin amount determined by 1-factor ANOVA (includes baseline group).

Significant effect of VA dosage amount at P < 0.05.

Significant values compared with baseline determined by LSMEANS with Dunnett correction.

The relative concentration of liver niacinamide was significantly affected by the amount of dietary niacin (P < 0.01) such that the DN group had higher amounts than the AN group (P < 0.05) (Table 4). In the small intestine, the treatment effect for niacin was significant (P < 0.001). Niacinamide did not differ between the AN and MN groups, but both were higher than the DN group (P ≤ 0.05) and all were higher than baseline (P ≤ 0.001). Erythrocyte niacinamide was significantly affected by the amount of dietary niacin and the VA dose (P < 0.001 for both), but the interaction was NS. The DN group had a lower relative amount than baseline and the AN and MS groups (P < 0.05 for all).

Relative liver tryptophan concentrations were significantly higher in the DN group than those at baseline (P = 0.008) and in the AN and MN groups (P ≤ 0.05 for both). Similarly, the relative amount of liver kynurenine was higher in the DN group than that in the AN group (P ≤ 0.05), but no differences compared with baseline were observed. Tryptophan and kynurenine amounts were correlated in the liver (r = 0.334, P = 0.02) (Supplemental Table 2). Liver 3-hydroxykynurenine was not different among groups, although it correlated with both tryptophan (r = 0.293, P = 0.02) and kynurenine (r = 0.804, P < 0.001). No differences were observed in the relative amounts of tryptophan in erythrocytes or small intestines.

The amount of ATP in the liver was significantly affected by the amount of dietary niacin (P < 0.04) such that the AN group had higher amounts compared with the DN group and baseline (P < 0.05 for both). Liver creatinine concentrations decreased significantly with increasing dietary niacin such that the DN group creatinine was higher than baseline, MN, and AN groups; and the MN group was higher than the AN group (P ≤ 0.05 for each). A similar effect of dietary niacin (P = 0.04) was observed in liver 3-methylhistidine relative concentrations, in which the DN group showed higher than the baseline and the AN group (P ≤ 0.05 for both). Liver creatinine and 3-methylhistidine were strongly correlated (r = 0.589, P < 0.001).

Plasma PLP

Plasma PLP concentrations were not affected by the VA dose but were affected by the amount of dietary niacin (P < 0.001), and an interaction occured (P = 0.009) (Figure 5). The AN groups maintained PLP concentrations similar to baseline, but the MN and DN groups had lower concentrations (P ≤ 0.001 for both). The MN group had higher concentrations than the DN group (P < 0.05), and AN had higher plasma PLP compared with both MN and DN groups (P ≤ 0.05). Plasma PLP concentration was positively correlated with estimated dietary niacin intake (r = 0.800, P < 0.001) (Supplemental Table 2) and serum retinol concentrations (r = 0.708, P < 0.001) (Table 3). In addition, plasma PLP was inversely correlated with markers of protein catabolism in the liver including tryptophan (r = −0.356, P = 0.041), creatinine (r = −0.560, P < 0.001), and 3-methylhistidine (r = −0.355, P = 0.002) (Supplemental Table 2).

FIGURE 5.

PLP concentration (nmol/L) of rats consuming 3 different amounts of dietary niacin: 0 mg/kg (DN), 15 mg/kg (MN), 30 mg/kg (AN). Differing letters indicate significance of P < 0.05, determined by 2-factor ANOVA (excluding baseline) with an interaction statement and mean comparisons by LSMEANS with Tukey-Kramer correction. †Significance of P < 0.05, determined by 1-factor ANOVA (including baseline) and mean comparisons by LSMEANS with Dunnet correction.

Discussion

Inadequate niacin intake caused significant alterations in VA distribution demonstrated by lower serum retinol concentrations, higher percentage of serum VA in the esterified form, and higher liver VA concentrations. Liver retinol concentrations responded positively to the VA dose amount where the 50-nmol/d dose resulted in concentrations that were similar to baseline, 350 nmol/d nearly achieved 1 μmol/g, and 3500 nmol/d resulted in toxic liver stores, confirmed by circulating serum retinyl esters and liver histologic examination. A retinyl acetate dose of 50 nmol/d is considered adequate to maintain VA balance in rats [18,26] with limited effect on liver retinol concentrations. Interestingly, among rats receiving the 50-nmol/d VA dose, AN was associated with no change compared with baseline liver retinol values, whereas the rats consuming DN and MN amounts of dietary niacin had significantly higher liver retinol concentrations than to AN. This phenomenon was maintained in each of the higher VA dose amounts (350 and 3500 nmol/d), demonstrating that optimal niacin intake results in lower VA concentration in the liver. A previous study showed that a vitamin B-complex supplement that included niacin prevented teratogenic effects of excess VA in laboratory rats [27], suggesting that B-vitamins are important for VA homeostasis.

When accounting for the different liver sizes for total liver VA, the AN group had higher values than the DN and MN groups within the highest VA dose amount (3500 nmol/d). In the middle VA dose (350-nmol/d) group, each amount of dietary niacin had higher total liver retinol values. However, there were no differences in the total liver VA within the lower VA dose amount (50 nmol/d). These findings, in conjunction with liver VA concentrations and differences in weights, suggest that the lack of dietary niacin did not cause lower liver VA concentrations in the DN rats because the total liver VA was not lower. It is likely that the lower liver retinol concentrations are a reflection of the effect of differing niacin amounts on growth.

Serum retinol concentrations were positively associated with the VA dose but to a lesser extent than dietary niacin. The percentage of serum total VA comprising retinyl esters was elevated in the DN groups. The DN groups did not receive an oral dose of VA the final day, and retinyl acetate was not detected in the serum retinyl ester analysis; thus, the elevations are not an artifact of postprandial absorption. Likely, the differences in the percentage serum esters are because of decreased serum total VA in the DN groups. This is further supported by fewer differences observed in absolute serum retinyl ester concentrations. Future human studies should assess both absolute ester concentrations and percentage of total VA until further validation with total liver reserves occurs. The changes in serum retinol, percentage retinyl esters in the serum, and liver retinol concentrations observed with differing amounts of dietary niacin provide evidence that niacin intake may indirectly affect VA homeostasis through subclinical alterations in growth. These findings are in line with mouse knockout studies of several of the dehydrogenase enzymes involved in VA metabolism, showing that knockout of these important enzymes impairs growth [14]. VA is essential for growth [20], but the interactions with other vitamins affecting homeostasis need further study.

Plasma PLP was significantly affected by the amount of dietary niacin but not the VA dose. The DN group had the lowest and the AN group had the highest plasma PLP concentrations. Plasma PLP is a biomarker of vitamin B-6 that is affected by several factors other than vitamin B-6 intake, including intakes of protein and riboflavin and inflammation [28]. Most of the PLP in circulation is albumin bound. The decreased body and organ weights and increased markers of protein catabolism suggest that the DN and, to a lesser extent, the MN groups were undergoing metabolic shifts due to malnutrition. Serum albumin (and albumin-bound PLP) decreases with malnutrition, which could explain the decreased plasma PLP in the DN and MN groups.

The cohort of Zambian children mentioned above with hypervitaminosis A had elevated markers of inflammation [3], exhibiting inverse associations with serum PLP [29] and vitamin B-6 intake [30], the latter of which was shown to be inadequate in over half of the cohort [9]. PLP is an essential cofactor for tryptophan conversion to niacinamide through the kynurenine pathway [12,13], and thus, it is possible that inadequate intake of and marginal vitamin B-6 status [3,9] contributed, along with inadequate intake [9], to a secondary functional niacin deficiency. It has been demonstrated that cardiac patients with low serum PLP concentration have decreased tryptophan to NAD conversion [31] and that the tryptophan:kynurenine ratio and vitamin B-6 status are positively associated with serum retinol [32], which may be related to inflammation.

The relative amount of liver NAD+ was not different among niacin treatment groups, which is in contrast to that found by Rawling et al. [11] who demonstrated that rats consuming 7% casein feed for 3 wks had decreased liver NAD+ concentrations. It is possible that due to the chronic nature of this study, metabolic adaptation to preserve liver NAD+ occurred. This is supported by the inverse association of dietary niacin and relative concentrations of tryptophan and kynurenine in the liver, which suggest increased kynurenic pathway activity when dietary niacin is inadequate. The relative concentrations of niacinamide in erythrocytes responded to treatment, demonstrating the effectiveness of the experimental feeds to change status in this study despite the liver NAD+ findings.

This study is limited due to the effect of niacin on growth and because the DN rats had to be killed a day earlier than the rest of the rats due to extreme weight loss. The AN group rats were significantly larger than both the lower intake groups, and the MN group rats were larger than the DN group rats at endline. These changes in growth are further supported by the differences observed in the liver and small intestine weights. The effect of restricted dietary niacin on growth is associated with the observed aggressive behavior in the DN group, which is consistent with rats on low tryptophan feed [33] and the potential for increased skeletal muscle catabolism demonstrated by higher creatinine and 3-methylhistidine in the livers of the DN and MN groups. The changes in growth make it difficult to determine if the changes in VA homeostasis are due to niacin status or the effect of niacin on growth, and it remains unknown what effects may occur in humans. Large VA doses acutely reduced the amount of NAD+ and increased the amount of the reduced form (NADH) in rat livers [16]. The shift in the ratio of NAD+ to NADH is in line with what would be expected with increased VA metabolism because the associated dehydrogenase enzymes reduce NAD+ to NADH. Evidence suggests that an increased amount of cellular NADH inhibits VA metabolism [17]. Furthermore, the amount of NAD+ available as an essential cofactor is predictive of the activity of the dehydrogenase enzymes in VA metabolism [15]. Low-niacin diets reduce the amount of erythrocyte NAD+ in humans [10], but the interaction with VA remains to be determined.

The present study is further limited by the inclusion of only male rats. Morbidity and mortality due to niacin deficiency was more severe among females than that in males [34], possibly because of sex hormone–related differences in rates of tryptophan to NAD conversion [35]. Therefore, it is possible that the present findings would have been more pronounced in female rats. Future studies should explore these findings in female and male rats under the same experimental conditions.

These findings may be important for VA status surveys and intervention programs in areas, such as Zambia that rely on maize, a poor source of niacin, as a dietary staple [7]. Due to the reliance on serum retinol concentrations for estimating VA deficiency prevalence, it is concerning that low-niacin intake was more strongly associated with lower serum retinol concentrations than VA intake. However, niacin is a potent modulator of inflammation [36]; therefore, it is unclear if the alterations in VA homeostasis caused by niacin restriction in this study are directly due to functional impairments of VA metabolism or if inflammation, which is a known confounder of VA status [37], mediated these results. Future human studies are warranted because population studies of VA status may need to consider niacin intake and status.

Author contributions

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows – TJT: designed the study, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the first draft of the paper; MSK: assisted with the sample analysis and rat care; SBSC: analyzed samples; FF, PFC, JLM: performed NMR experiments and identified metabolites; JFG: assessed plasma PLP; SAT: assisted in study design, suggested analyses, and revised the manuscript; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Supported by the Wisconsin Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Research Support Award (TJT) and the Cargill-Benevenga Research Stipend (SBSC). This study made use of the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison, which is supported by NIH grant P41GM103399 (NIGMS) (previous number: P41RR002301). Equipment was purchased with funds from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, NIH (P41GM103399, S10RR02781, S10RR08438, S10RR023438, S10RR025062, S10RR029220), NSF (DMB-8415048, OIA-9977486, BIR-9214394), and USDA.

Acknowledgments

We thank Barbara Mickelson of Envigo for assistance in feed design; Christopher Davis for assistance with animal care; Brian Parks for lending us a tissue homogenizer; and Peter Crump of the CALS Consulting Lab at UW-Madison for statistical consultations.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the Wisconsin Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics in March 2019.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.06.026.

Contributor Information

Tyler J. Titcomb, Email: tyler-titcomb@uiowa.edu.

Sherry A. Tanumihardjo, Email: sherry@nutrisci.wisc.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2009. Global Prevalence of Vitamin A Deficiency in Populations at Risk 1995-2005: Global Database on Vitamin A Deficiency.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44110 [Internet] cited 5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gannon B.M., Kaliwile C., Arscott S.A., Schmaelzle S., Chileshe J., Kalungwana N., et al. Biofortified orange maize is as efficacious as a vitamin A supplement in Zambian children even in the presence of high liver reserves of vitamin A: a community-based, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014;100(6):1541–1550. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.087379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mondloch S., Gannon B.M., Davis C.R., Chileshe J., Kaliwile C., Masi C., et al. High provitamin A carotenoid serum concentrations, elevated retinyl esters, and saturated retinol-binding protein in Zambian preschool children are consistent with the presence of high liver vitamin A stores. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015;102(2):497–504. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.112383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sowa M., Mourao L., Sheftel J., Kaeppler M., Simons G., Grahn M., et al. Overlapping vitamin A interventions with provitamin A carotenoids and preformed vitamin A cause excessive liver retinol stores in male Mongolian gerbils. J. Nutr. 2020;150(11):2912–2923. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxaa142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanumihardjo S.A., Kaliwile C., Boy E., Dhansay M.A., van Stuijvenberg M.E. Overlapping vitamin A interventions in the United States, Guatemala, Zambia, and South Africa: case studies. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2019;1446(1):102–116. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmaelzle S., Kaliwile C., Arscott S.A., Gannon B., Masi C., Tanumihardjo S.A. Nutrient and nontraditional food intakes by Zambian children in a controlled feeding trial. Food Nutr. Bull. 2014;35(1):60–67. doi: 10.1177/156482651403500108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suri D.J., Tanumihardjo S.A. Effects of different processing methods on the micronutrient and phytochemical contents of maize: from A to Z. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016;15(5):912–926. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine . National Academies Press; Washington (DC): 1998. Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamine, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Titcomb T.J., Schmaelzle S.T., Nuss E.T., Gregory J.F., III, Tanumihardjo S.A. Suboptimal vitamin B intakes of Zambian preschool children: evaluation of 24-hour dietary recalls. Food Nutr. Bull. 2018;39(2):281–289. doi: 10.1177/0379572118760373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu C.S., Swendseid M.E., Jacob R.A., McKee R.W. Biochemical markers for assessment of niacin status in young men: levels of erythrocyte niacin coenzymes and plasma tryptophan. J. Nutr. 1989;119(12):1949–1955. doi: 10.1093/jn/119.12.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rawling J.M., Jackson T.M., Driscoll E.R., Kirkland J.B. Dietary niacin deficiency lowers tissue poly(ADP-ribose) and NAD+ concentrations in Fischer-344 rats. J. Nutr. 1994;124(9):1597–1603. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.9.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badawy A.A. Kynurenine pathway of tryptophan metabolism:regulatory and functional aspects. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 2017;10 doi: 10.1177/1178646917691938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuwatari T., Shibata K. Nutritional aspect of tryptophan metabolism. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 2013;6:3–8. doi: 10.4137/IJTR.S11588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar S., Sandell L.L., Trainor P.A., Koentgen F., Duester G. Alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases: retinoid metabolic effects in mouse knockout models. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1821(1):198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kedishvili N.Y. Enzymology of retinoic acid biosynthesis and degradation. J. Lipid Res. 2013;54(7):1744–1760. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R037028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dileepan K.N., Singh V.N., Ramachandran C.K. Early effects of hypervitaminosis A on gluconeogenic activity and amino acid metabolizing enzymes of rat liver. J. Nutr. 1977;107(10):1809–1815. doi: 10.1093/jn/107.10.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chase J.R., Poolman M.G., Fell D.A. Contribution of NADH increases to ethanol’s inhibition of retinol oxidation by human ADH isoforms. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2009;33(4):571–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00871.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Research Council . Fourth Revised Edition; Washington (DC): 1995. Nutrient Requirements of Laboratory Animals. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reeves P.G., Nielsen F.H., Fahey G.C., Jr. AIN-93 purified diets for laboratory rodents: final report of the American Institute of Nutrition ad hoc writing committee on the reformulation of the AIN-76A rodent diet. J. Nutr. 1993;123(11):1939–1951. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.11.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riabroy N., Dever J.T., Tanumihardjo S.A. α-Retinol and 3,4-didehydroretinol support growth in rats when fed at equimolar amounts and α-retinol is not toxic after repeated administration of large doses. Br. J. Nutr. 2014;111(8):1373–1381. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513003851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanumihardjo S.A., Howe J.A. Twice the amount of alpha-carotene isolated from carrots is as effective as beta-carotene in maintaining the vitamin A status of Mongolian gerbils. J. Nutr. 2005;135(11):2622–2626. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.11.2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ubbink J.B., Serfontein W.J., de Villiers L.S. Stability of pyridoxal-5-phosphate semicarbazone: applications in plasma vitamin B6 analysis and population surveys of vitamin B6 nutritional status. J. Chromatogr. 1985;342(2):277–284. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)84518-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fathi F., Brun A., Rott K.H., Falco Cobra P., Tonelli M., Eghbalnia H.R., et al. NMR-based identification of metabolites in polar and non-polar extracts of avian liver. Metabolites. 2017;7(4):61. doi: 10.3390/metabo7040061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kane M.A., Folias A.E., Napoli J.L. HPLC/UV quantitation of retinal, retinol, and retinyl esters in serum and tissues. Anal. Biochem. 2008;378(1):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gannon B.M., Davis C.R., Nair N., Grahn M., Tanumihardjo S.A. Single high-dose vitamin A supplementation to neonatal piglets results in a transient dose response in extrahepatic organs and sustained increases in liver stores. J. Nutr. 2017;147(5):798–806. doi: 10.3945/jn.117.247577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green M.H., Green J.B. Vitamin A intake and status influence retinol balance, utilization and dynamics in rats. J. Nutr. 1994;124(12):2477–2485. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.12.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Millen J.W., Woollam D.H. Effect of vitamin B complex on the teratogenic activity of hypervitaminosis A. Nature. 1958;182(4640):940. doi: 10.1038/182940a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ueland P.M., Ulvik A., Rios-Avila L., Midttun O., Gregory J.F., III Direct and functional biomarkers of vitamin B6 status. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2015;35:33–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071714-034330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakakeeny L., Roubenoff R., Obin M., Fontes J.D., Benjamin E.J., Bujanover Y., et al. Plasma pyridoxal-5-phosphate is inversely associated with systemic markers of inflammation in a population of U.S. adults. J. Nutr. 2012;142(7):1280–1285. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.153056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris M.S., Picciano M.F., Jacques P.F., Selhub J. Plasma pyridoxal 5'-phosphate in the US population: the national health and nutrition examination survey, 2003-2004. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008;87(5):1446–1454. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Midttun O., Ulvik A., Ringdal Pedersen E., Ebbing M., Bleie O., Schartum-Hansen H., et al. Low plasma vitamin B-6 status affects metabolism through the kynurenine pathway in cardiovascular patients with systemic inflammation. J. Nutr. 2011;141(4):611–617. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.133082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olsen T., Vinknes K.J., Blomhoff R., Lysne V., Midttun O., Dhar I., et al. Creatinine, total cysteine and uric acid are associated with serum retinol in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020;59(6):2383–2393. doi: 10.1007/s00394-019-02086-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kantak K.M., Hegstrand L.R., Whitman J., Eichelman B. Effects of dietary supplements and a tryptophan-free diet on aggressive behavior in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1980;12(2):173–179. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(80)90351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park Y.K., Sempos C.T., Barton C.N., Vanderveen J.E., Yetley E.A. Effectiveness of food fortification in the United States: the case of pellagra. Am. J. Public Health. 2000;90(5):727–738. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.5.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shibata K., Toda S. Effects of sex hormones on the metabolism of tryptophan to niacin and to serotonin in male rats. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1997;61(7):1200–1202. doi: 10.1271/bbb.61.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu B.J., Yan L., Charlton F., Witting P., Barter P.J., Rye K.A. Evidence that niacin inhibits acute vascular inflammation and improves endothelial dysfunction independent of changes in plasma lipids. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010;30(5):968–975. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.201129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suri D.J., Tanumihardjo J.P., Gannon B.M., Pinkaew S., Kaliwile C., Chileshe J., et al. Serum retinol concentrations demonstrate high specificity after correcting for inflammation but questionable sensitivity compared with liver stores calculated from isotope dilution in determining vitamin A deficiency in Thai and Zambian children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015;102(5):1259–1265. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.113050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.