Abstract

In 1995, the rate of isolation of Enterobacter aerogenes in the Saint-Pierre University Hospital in Brussels, Belgium, was higher than that in the preceding years. A total of 45 nosocomial E. aerogenes strains were collected from 33 patients of different units during that year, and they were isolated from 19 respiratory specimens, 13 pus specimens, 7 blood specimens, 4 urinary specimens, 1 catheter specimen, and 1 heparin vial. The strains were analyzed to determine their epidemiological relatedness and were characterized by their antibiotic resistance pattern determination, plasmid profiling, and genomic fingerprinting by macrorestriction analysis with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). The majority of the strains (82%) were multiply resistant to different commonly used antibiotics. Two major plasmid profiles were found: most strains (64%) harbored two plasmids of different sizes, whereas the others (20%) contained a single plasmid. PFGE with SpeI and/or XbaI restriction enzymes revealed that a single clone (80%) was responsible for causing infections or colonizations throughout the year, and this result was concordant with those obtained by plasmid profiling, with slight variations. By comparing the results of these three methods, PFGE and plasmid profiling were found to be the techniques best suited for investigating the epidemiological relatedness of E. aerogenes strains, and they are therefore proposed as useful tools for the investigation of nosocomial outbreaks caused by this organism.

The genus Enterobacter is one of the members of the family Enterobacteriaceae and consists of 13 species (8). Among them, Enterobacter cloacae and Enterobacter aerogenes are the most frequently isolated species, causing infections in hospitalized and debilitated patients (10, 29). In recent years, E. aerogenes has emerged as an important nosocomial bacterial pathogen (6, 20). The strains are usually characterized by their high levels of resistance to ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, and expanded-spectrum cephalosporins or imipenem (3, 14, 23, 25). E. aerogenes outbreaks are often found to occur among intensive care unit (ICU) patients, and colonization usually occurs in the respiratory, urinary, and gastrointestinal tracts and less frequently in skin and surgical wounds (1, 5, 7, 11, 21).

Nosocomial bacterial infections are an important cause of morbidity and mortality in both developing and developed countries. Transmission of nosocomial outbreak-related bacteria may be effectively controlled by taking appropriate control measures. Before that is done, however, it may be necessary to identify a particular clone or clones of bacteria. The recognition that a single clone is spreading a number of infections is an essential early step in the investigation of a possible outbreak in a hospital. To do that, epidemiological typing of the strains is performed by using possible genotypic and phenotypic methods. Phenotypic techniques are insufficient for discriminating different isolates of Enterobacter spp. However, a number of genotype-based techniques have been successfully applied for demonstrating the differences between the strains (4, 11–13, 15). In 1995, the isolation rate of E. aerogenes in the Saint-Pierre University Hospital was higher than those in the preceding years and in the following year. To determine whether the strains were epidemiologically linked, we analyzed them by using biotyping, antibiotyping, plasmid profiling, and genomic fingerprinting by macrorestriction analysis with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

(This work was presented in part at the 97th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, Miami Beach, Fla., 4 to 8 May 1997 [14a].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains: origin and identification.

The Saint-Pierre University Hospital is a 450-bed teaching hospital located in the center of Brussels, Belgium. It has two ICUs (internal medicine and surgery) of 13 beds each and several departments. The 45 E. aerogenes strains were collected from 33 patients hospitalized in different wards, and their hospital records were reviewed by two investigators to confirm nosocomial acquisition according to the criteria of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (9). The strains were isolated from 19 (42.2%) respiratory specimens, 13 (28.9%) pus specimens, 7 (15.6%) blood specimens, 4 (8.9%) urinary specimens, 1 (2.2%) catheter specimen, and 1 (2.2%) heparin vial specimen.

E. aerogenes isolates were primarily identified in the microbiology laboratory by standard culture techniques (8). Subsequently, the identities of the strains were confirmed by the BBL crystal E/NF identification system (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.). This system provides the interpretation of the results of 30 different biochemical tests including a manual oxidase and indole tests. It is more reliable and cost-effective, can be performed more quickly and simply, and is safer to use than other commercially available microbial identification systems described in several reports (24, 28, 32).

Screening of environmental specimens.

Environmental specimens were screened for E. aerogenes by culturing premoistened swabs from the suspected surfaces and liquid samples obtained from different environmental sources or devices. The samples included swabs of the table surfaces near the infected or colonized patients (n = 10), disinfectants when they were available at the bedside of the patients from ICUs and geriatric units (n = 7), humidifying cascades from the mechanical ventilators of the patients admitted to the ICUs (n = 15), oxygen humidifier bottles for nebulizers (n = 5), tap water and hot and cold water faucets (n = 5), and a heparin vial used for one patient admitted to an ICU (n = 1). No specimens from the hands of the hospital personnel were available.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed on Mueller-Hinton agar (Oxoid Ltd., Hampshire, United Kingdom) medium by a tablet disk diffusion method with Neo-sensitabs (Rosco Diagnostica, Taastrup, Denmark) against a panel of 14 antimicrobial drugs. Neo-sensitabs are produced according to the guidelines of the World Health Organization (33) and are standardized according to the MIC breakpoints recommended by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (22). The zone sizes were interpreted according to the guidelines of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (22). The tablet disks contained the following antimicrobial agents: ampicillin, gentamicin, co-trimoxazole, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, piperacillin-tazobactam, aztreonam, temocillin, ceftazidime, cefazolin, cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, imipenem, ciprofloxacin, and amikacin. Strains with intermediate zones were considered resistant.

Plasmid profile analysis.

Plasmid DNA of the 45 strains was prepared by the method described by Portnoy et al. (26). By this method, the lysis solution destroys the cell wall as well as the cell membrane and denatures the chromosomal DNA in a single step by the combined action of sodium dodecyl sulfate and an alkaline solution. The technique is based on the fact that a narrow pH range (pH 12.00 to 12.55) can denature only the linear chromosomal DNA and not the covalently closed circular plasmid DNA.

Plasmids were separated by electrophoresis run at 80 V for 4 h in a 0.7% agarose gel containing 1× TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) buffer. The gels were stained in a 1-μg/ml ethidium bromide solution, visualized under UV light, and photographed with a Polaroid camera. The sizes of the plasmids were determined by using as a standard Escherichia coli V517, which contains seven different plasmids (16).

DNA macrorestriction and PFGE.

Genomic DNA was prepared by a protocol devised from different methods published elsewhere (2, 17, 19, 30). Bacterial cells were grown in 5.0 ml of Trypticase soy broth at 37°C overnight in a shaking water bath with agitation, and the optical density at 600 nm was measured. The optical density at 600 nm was adjusted with sterile Trypticase soy broth so that it had a cell concentration of 109 CFU/ml. For each isolate, 100 μl of the cell suspension was pelleted by centrifugation and washed with EET buffer (100 mM sodium EDTA, 10 mM sodium EGTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5]), and the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of the same buffer, an equal volume of 2% melted InCert agarose (FMC Bio Products, Vallensbaek Strand, Denmark) was mixed in, and the mixture was dispensed into two wells of the plug mold. After solidification, the plugs were incubated at 37°C for 1 h in 500 μl of lysis solution (lysozyme, 1 mg/ml; Tris-HCl, 10 mM; NaCl, 50 mM; sodium deoxycholate, 0.2%; sodium-N-lauroylsarcosine, 0.5%) and washed once with T10E1 buffer (Tris-HCl, 10 mM; sodium EDTA, 1 mM [pH 7.5]). The agarose plugs were subsequently deproteinized in 500 μl of proteinase K solution (proteinase K, 1 mg/ml; EDTA, 100 mM [pH 8.0]; sodium deoxycholate, 0.2%; sodium-N-lauroylsarcosine, 1%) at 50°C overnight, and the protein digestion products were removed by washing the plugs six times for 30 min each time with 1.0 ml of T10E1 buffer. During the second wash 15 μl of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (100 mM) was added to inactivate the residual proteinase K activity.

The E. aerogenes plugs were digested with 25 U of SpeI restriction enzyme, and a duplicate set of plugs was also digested with 40 U of XbaI restriction enzyme according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resultant fragments were resolved in the CHEF DRII system (Bio-Rad, Nazareth, Belgium) with a 1% agarose gel prepared and run in 0.5× TBE buffer. The gels were run at 6 V/cm for 20 h at 14°C. The pulse time ramped from 5 to 15 s for 20 h for SpeI-restricted plugs and two linear ramps of 5 to 40 s for 12 h followed by 3 to 8 s for 8 h for XbaI-restricted plugs. The PFGE marker-I (Boehringer Mannheim, Brussels, Belgium) was used as a molecular size standard. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide (1 μg/ml) and photographed under UV light.

The PFGE patterns were compared initially by visual comparison and were interpreted according to the guidelines of Tenover et al. (31). Patterns were considered indistinguishable if every band was shared, closely related if they differed from one another by only two or three clearly visible bands, and different if they differed by seven or more bands.

With the Molecular Analyst Software Fingerprinting, version 1.0 (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.), PFGE patterns were also compared and clustered into a dendrogram.

RESULTS

Bacterial strains.

In this investigation, 45 E. aerogenes isolates originating from 33 hospitalized patients were available. These patients represented 84.6% of the 39 hospitalized patients from whom the organism was recovered in the year 1995. Single isolates were obtained from 26 patients, two isolates were obtained from 4 patients, three isolates were obtained from 2 patients, four isolates were obtained from 1 patient, and one isolate was obtained from a heparin vial specimen (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Phenotypic and genotypic characters of E. aerogenes isolates isolated from patients in Saint-Pierre University Hospital in 1995a

| Isolate no. | Patient designation | Strain identification | Antimicrobial susceptibilityb (antibiotype) | Biotypec | Plasmid profiled | PFGE profilee

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpeI | XbaI | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | FH-49 | Gm, SXT, AMC, PTZ, ATM, TEM, CTAZ, AK, CIP, IMP (6) | 1 | NP | NC | NC |

| 2 | 2 | FH-51 | Gm, SXT, PTZ, ATM, TEM, CTAZ, CXM, CTX, AK, CIP, IMP (5) | 1 | C | IIa | IIa |

| 3 | 2 | FH-52 | Gm, SXT, PTZ, ATM, TEM, CTAZ, CXM, CTX, AK, CIP, IMP (5) | 1 | C | IIa | IIa |

| 4 | 2 | BG-59 | Gm, SXT, PTZ, ATM, TEM, CTAZ, CXM, CTX, AK, CIP, IMP (5) | 13 | C | IIa | IIa |

| 5 | 3 | FH-53 | Gm, SXT, PTZ, ATM, TEM, CTAZ, CTX, AK, CIP, IMP (7) | 2 | B | NC | NC |

| 6 | 4 | FH-54 | Gm, TEM, AK, IMP (1) | 4 | A | I | I |

| 7 | 4 | BG-60 | Gm, TEM, AK, IMP (1) | 14 | A | I | I |

| 8 | 5 | FH-55 | Gm, TEM, AK, IMP (1) | 5 | A | I | I |

| 9 | 6 | FH-56 | Gm, TEM, AK, IMP (1) | 12 | A | I | I |

| 10 | 7 | FH-57 | Gm, AMC, TEM, AK, IMP (2) | 5 | A | I | I |

| 11 | 8 | FH-58 | Gm, AMC, TEM, AK, IMP (2) | 6 | A | I | I |

| 12 | 8 | BG-61 | Gm, AMC, TEM, AK, IMP (2) | 14 | A | I | I |

| 13 | 8 | BG-63 | Gm, AMC, TEM, AK, IMP (2) | 7 | A | I | I |

| 14 | 9 | FH-59 | Gm, TEM, AK, IMP (1) | 5 | A | I | I |

| 15 | 10 | FH-60 | Gm, TEM, AK, IMP (1) | 6 | A | I | I |

| 16 | 11 | FH-63 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, AK, IMP (3) | 3 | A | I | I |

| 17 | 12 | FH-64 | Gm, TEM, AK, IMP (1) | 7 | B | I | I |

| 18 | 12 | BG-62 | Gm, TEM, AK, IMP (1) | 7 | A | I | I |

| 19 | 13 | FH-65 | Gm, AMC, TEM, AK, IMP (2) | 4 | A | I | I |

| 20 | 14 | FH-67 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, AK, IMP (3) | 6 | A | I | I |

| 21 | 15 | FH-70 | Gm, AMC, TEM, AK, IMP (2) | 4 | A | I | I |

| 22 | 15 | FH-76 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, AK, IMP (3) | 4 | A | I | I |

| 23 | 16 | FH-71 | Gm, AMC, TEM, AK, IMP (2) | 4 | A | I | I |

| 24 | 16 | FH-74 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, CTX, AK, IMP (4) | 9 | B | I | I |

| 25 | 16 | FH-80 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, CTX, AK, IMP (4) | 4 | A | I | I |

| 26 | 16 | FH-81 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, CTX, AK, IMP (4) | 5 | A | I | I |

| 27 | 17 | FH-72 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, CTX, AK, IMP (4) | 8 | A | IIb | IIb |

| 28 | 18 | FH-73 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, AK, IMP (3) | 5 | A | I | I |

| 29 | 19 | FH-75 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, CTX, AK, IMP (4) | 5 | B | I | I |

| 30 | 20 | FH-77 | Gm, SXT, AMC, TEM, AK, CIP, IMP (8) | 3 | NP | NC | NC |

| 31 | 21 | FH-78 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, CTX, AK, IMP (4) | 5 | B | I | I |

| 32 | 21 | FH-85 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, CTX, AK, IMP (4) | 10 | A | I | I |

| 33 | 21 | FH-86 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, CTX, AK, IMP (10) | 5 | A | I | I |

| 34 | 22 | FH-79 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, CTX, AK, IMP (4) | 5 | B | I | I |

| 35 | 23 | FH-82 | Gm, SXT, AMC, PTZ, ATM, TEM, CTAZ, CFZ, CXM, CTX, AK, CIP, IMP (9) | 1 | C | IIa | IIa |

| 36 | 24 | FH-83 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, CTX, AK, IMP (4) | 10 | A | I | I |

| 37 | 25 | FH-84 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, AK, IMP (3) | 5 | A | I | I |

| 38 | 26 | FH-87 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, AK, IMP (3) | 3 | B | I | I |

| 39 | 27 | FH-88 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, CTX, AK, IMP (4) | 3 | B | I | I |

| 40 | 28 | FH-89 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, CTX, AK, IMP (4) | 9 | A | I | I |

| 41 | 29 | FH-90 | Gm, SXT, AMC, PTZ, ATM, TEM, CTAZ, CTX, AK, CIP, IMP (11) | 11 | MP | IIb | IIb |

| 42 | 30 | FH-91 | Gm, AMC, PTZ, TEM, CTX, AK, IMP (4) | 9 | A | I | I |

| 43 | 31 | FH-92 | GM, AMC, PTZ, TEM, CTX, AK, IMP (4) | 4 | B | I | I |

| 44 | 32 | BG-57 | Gm, TEM, AK, IMP (1) | 7 | A | I | I |

| 45 | 33 | BG-64 | Gm, TEM, AK, IMP (1) | 1 | A | I | I |

A total of 45 E. aerogenes isolates were obtained.

Susceptibility to different antimicrobial agents. Abbreviations are as follows: Gm, gentamicin; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; AMC, amoxicillin-clavulanate; PTZ, piperacillin-tazobactam; ATM, aztreonam; TEM, temocillin; CTAZ, ceftazidime; CFZ, cefazolin; CXM, cefuroxime; AK, amikacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; IMP, imipenem.

Biotypes are based on the different numerical profiles generated from the BBL Crystal E/NF system.

Plasmid profile A, 2 plasmids (30 to 40 and 5 to 6 MDa, respectively); profile B, one plasmid (5 to 6 MDa); profile C, three plasmids (20 to 30, 15 to 20, and 5 to 6 MDa, respectively); NP, no plasmid; MP, multiple plasmids of various sizes.

PFGE profiles were generated after restriction digestion of chromosomal DNA with SpeI and XbaI restriction enzymes. NC, nonclonal.

Biotyping.

Fourteen different biotypes were generated among the 45 E. aerogenes isolates on the basis of the formulated profile found after positive and negative reactions in different wells of the BBL crystal E/NF identification system. The biotypes were arbitrarily designated 1 to 14. In a few patients the biotypes differed among the strains according to the site of isolation (Table 1).

Screening of environmental specimens.

E. aerogenes was isolated from the heparin vial specimen only. No E. aerogenes was found in any of the other environmental specimens.

Antibiotyping.

E. aerogenes isolates were grouped into 11 different antibiotypes depending upon their susceptibilities to 14 different antimicrobial drugs. Almost all strains were resistant to ampicillin, cefazolin, and cefuroxime but were sensitive to gentamicin, temocillin, amikacin, and imipenem. The antimicrobial resistance patterns were pooled, and it was found that 91 to 100% of the strains were resistant to ampicillin, cefazolin, and cefuroxime; 82 to 84% were resistant to co-trimoxazole, aztreonam, ceftazidime, and ciprofloxacin; 56% were resistant to ceftriaxone, 40% were resistant to piperacillin-tazobactam; 31% were resistant to amoxicillin-clavulanate; and 2% were resistant to temocillin. The antibiotypes are presented in Table 1.

Plasmid profile analysis of E. aerogenes.

Plasmids were found in 43 (96%) of the 45 E. aerogenes isolates. Only one strain (from patient 29) harbored five plasmids of different sizes, whereas the rest of the strains were grouped into three different profiles depending upon the sizes and the numbers of the plasmids.

Profile A consists of a big (30 to 40 MDa) and a small (5 to 6 MDa) plasmid. A total of 29 (64%) strains belonged to this profile. Ten (22%) strains belonged to profile B, which contained a single plasmid of 5 to 6 MDa. Profile C was found for four strains (9%), which contained three plasmids (20 to 30, 15 to 20, and 5 to 6 MDa, respectively). The plasmid data are listed in Table 1.

PFGE.

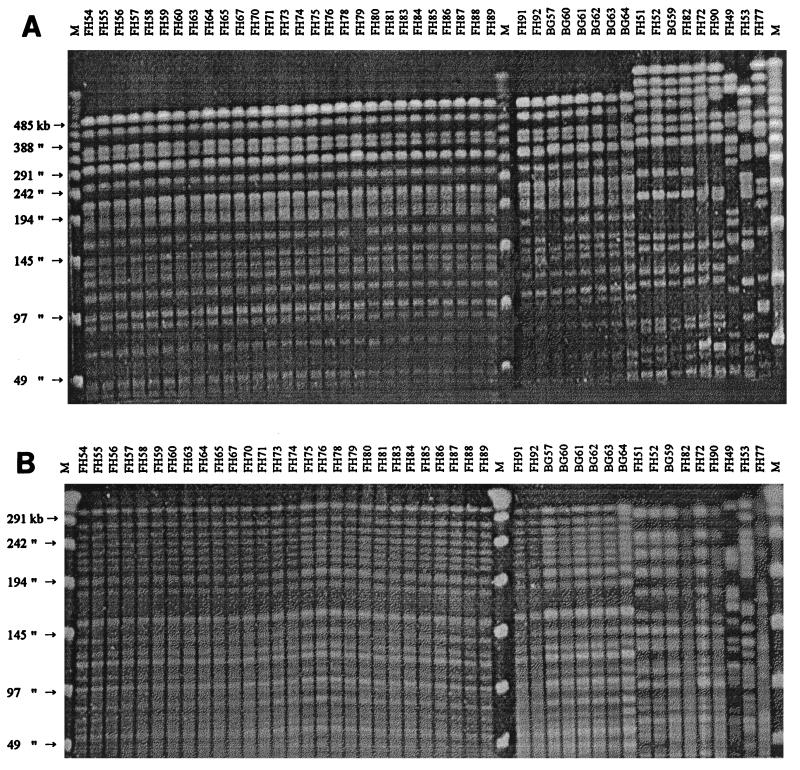

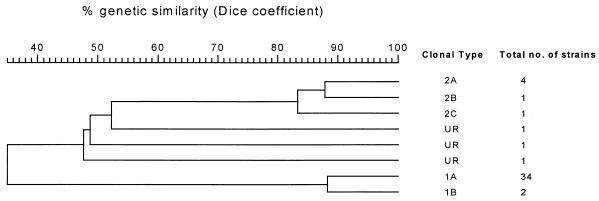

All 45 strains were typeable, and the fingerprints generated with both SpeI and XbaI restriction endonucleases equally demonstrated that 36 (80%) strains were derived from a single clone, designated clone I. Six (13%) strains were closely related and were designated as being derived from clones IIa and IIb, and only three (7%) strains were found to be nonclonal. The XbaI-digested fragments were more easily interpretable than the SpeI-digested fragments (Fig. 1). The dendrogram generated from PFGE patterns gave similar information (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

PFGE fingerprints of 45 E. aerogenes isolates (1995) after digestion with the XbaI restriction enzyme (A) and the SpeI restriction enzyme (B). Lane FH54 to lane BG64, profile IA and profile IB (broadly clone I); lane FH51 to lane FH90, profiles IIA, IIB, and IIC (broadly, clone II); lane FH49 to lane FH77, unrelated strains (nonclonal); lanes M, molecular size markers (PFGE marker I, λ ladder).

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram generated from PFGE patterns of nosocomial E. aerogenes strains (n = 45) by Molecular Analyst Software Fingerprinting, version 1.0. Major clones are designated with arabic numerals, and subtypes are indicated by letter suffixes. Clustering was done with the unweighted pair group method with arithmatic averages algorithm by using fine correlation on gel tracks.

Primary analysis of the clinical data from colonized and infected patients.

The 45 E. aerogenes isolates were recovered from 33 patients, of whom 22 (66.7%) were infected and 11 (33.3%) were considered colonized. Most of the patients were elderly, were suffering from chronic underlying diseases, and were hospitalized in either the medical or the surgical ICU. During their hospitalization, 13 patients died (crude mortality rate, 39%). The clinical features are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Clinical features of the 33 patients infected or colonized with E. aerogenes strains in Saint-Pierre University Hospital in 1995

| Patient no. | Unit or ward | Patient age (yr) | First isolation date (day-mo-yr) | Source of isolation | Colonization or infection | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Geriatric | 58 | 24-01-1995 | Tracheal aspirate | Pneumonia and urinary tract infection | Death |

| 2 | Surgical ICU | 70 | 07-04-1995 | Blood | Septicemia | Death |

| 3 | Coronary care unit | 42 | 03-07-1995 | Blood | Septicemia | Recovered |

| 4 | Medical ICU | 63 | 19-07-1995 | Blood | Pneumonia | Death |

| 5 | Geriatric | 72 | 24-07-1995 | Decubitus ulcer | Colonization | Recovered |

| 6 | Medicine | 69 | 25-07-1995 | Tracheal aspirate | Bronchopneumonia | Recovered |

| 7 | Medical ICU | 54 | 27-07-1995 | Sputum + peritoneal fluid | Abdominal infection | Recovered |

| 8 | Medical ICU | 90 | 08-08-1995 | Catheter | Colonization | Death |

| 9 | Surgical ICU | 71 | 23-08-1995 | Pleural fluid | Pleural empyema | Death |

| 10 | Medical ICU | 71 | 23-08-1995 | Sputum | Pneumonia | Recovered |

| 11 | Medical ICU | 43 | 25-08-1995 | Tracheal aspirate | Pneumonia | Death |

| 12 | Geriatric | 73 | 28-08-1995 | Wound swab + urine | Urinary tract infection | Death |

| 13 | Medicine | 77 | 29-08-1995 | Sputum | Colonization | Recovered |

| 14 | Medical ICU | 51 | 09-09-1995 | Blood | Ascites infection | Death |

| 15 | Medical ICU | 63 | 09-09-1995 | Blood | Septicemia | Recovered |

| 16 | Geriatric | 97 | 19-09-1995 | Nasopharyngeal aspirate | Pneumonia | Death |

| 17 | Geriatric | 76 | 22-09-1995 | Decubitus ulcer + urine | Urinary tract infection | Recovered |

| 18 | Surgical ICU | 88 | 27-09-1995 | Abdominal wound | Abdominal infection | Death |

| 19 | Medical ICU | 72 | 12-10-1995 | Tracheal aspirate | Pneumonia | Recovered |

| 20 | Recovery unit | 70 | 15-10-1995 | Tracheal aspirate | Bronchitis | Recovered |

| 21 | Geriatric | 81 | 23-10-1995 | Rectal swab | Colonization | Death |

| 22 | Surgery | 28 | 27-10-1995 | Abdominal liquid | Abdominal infection | Recovered |

| 23 | Medical ICU | 64 | 31-10-1995 | Tracheal aspirate | Pneumonia | Death |

| 24 | Medicine | 71 | 07-11-1995 | Sputum | Colonization | Recovered |

| 25 | Medical ICU | 80 | 11-11-1995 | Tracheal aspirate | Pneumonia | Death |

| 26 | Geriatric | 88 | 13-11-1995 | Urine | Urinary tract infection | Recovered |

| 27 | Recovery unit | 81 | 18-11-1995 | Decubitus ulcer | Colonization | Recovered |

| 28 | Medicine | 60 | 21-11-1995 | Tongue swab | Colonization | Recovered |

| 29 | Otorhinolaryngology | 7 | 25-11-1995 | Urine | Colonization | Recovered |

| 30 | Medical ICU | 86 | 04-12-1995 | Sputum | Colonization | Recovered |

| 31 | Medical ICU | 51 | 05-12-1995 | Sputum | Colonization | Recovered |

| 32 | Surgery | 44 | 06-12-1995 | Sputum | Colonization | Recovered |

| 33 | Recovery unit | 50 | 27-12-1995 | Urine | Urinary tract infection | Recovered |

DISCUSSION

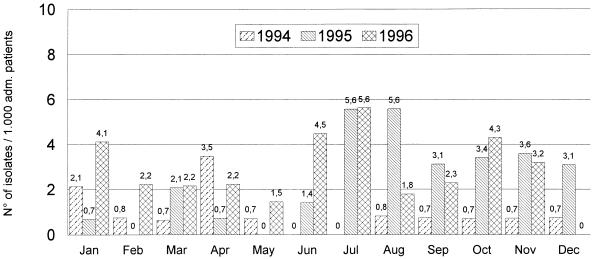

E. aerogenes is able to cause nosocomial infections, like other members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. In 1995, the incidence of E. aerogenes in our hospital was higher than those in the preceding and the following years (Fig. 3). Among the 33 patients, the ratio of colonization and infection (1:2), as well as the high crude mortality rate (39%) among the E. aerogenes-infected patients, led us to be particularly concerned so we studied the epidemiology of this bacterium. In our study, we found that E. aerogenes colonizations or infections were endemic in the year 1995 and continued to the following year (unpublished data). The first isolated strain belonging to clone I (80% of the total isolates) appeared in January and infected a 58-year-old patient in the geriatric unit. This patient was colonized after 8 days of hospitalization and developed pneumonia and subsequently a urinary tract infection. The second acquisition occurred in April and was of a nonclonal strain that infected a 70-year-old patient in the surgical ICU; the patient developed septicemia, followed by death. From July until December, we found a real nosocomial outbreak caused by the two major clonal groups, groups I and II (Table 2). Most of the acquisitions occurred among elderly patients admitted to the two ICUs and the geriatric unit or transferred among these units. In this period, patients were probably colonized or infected through patient-to-patient transmission, via hospital personnel, or from other unknown hospital devices or environmental sources. The cause of the disappearance of the predominant clonal strain (clone I) in the months of February until June is not known, but infection control measures were probably strictly maintained at that time.

FIG. 3.

Incidence of E. aerogenes at Saint-Pierre University Hospital from January 1994 to December 1996.

We analyzed some environmental specimens (n = 43), but only one E. aerogenes isolate was recovered from a patient’s heparin vial (strain 4 of patient 2) used for parenteral treatment. The E. aerogenes isolate from this source did not belong to the predominant clone I and had the same antibiotype, plasmid profile, and PFGE pattern as those of two other blood isolates of the same patient. This indicates that for this patient transmission occurred through the heparin vial, which could possibly have been contaminated by the hands of the hospital personnel.

Epidemiologic typing of the bacterial strains is being performed by using phenotypic and genotypic techniques. Phenotypic techniques are insufficient for discriminating among the isolates of different Enterobacter spp. In the present investigation, we found 14 different biotypes and 11 antibiotypes among the 45 E. aerogenes isolates, and these typing patterns failed to give any particular association between the strains. It was evident, however, that most of the strains were resistant to ampicillin, co-trimoxazole, aztreonam, ceftazidime, cefazolin, cefuroxime, and ciprofloxacin. DNA-based techniques have successfully been applied to demonstrating the differences between E. aerogenes strains in several studies (7, 11, 12, 13). In this study, we compared the results of plasmid profiling and PFGE analysis for the typing of E. aerogenes strains and demonstrated that a single clone was present over a period of 1 year. Plasmid analysis has been used most widely as a molecular method for comparing nosocomial isolates. In our study, the strains were divided into two major profiles, whereas two strains did not contain any plasmid. Instability of the plasmid profiles caused by the acquisition or loss of the plasmids is a great disadvantage of this method. Nevertheless, we found a good correlation between plasmid profiling and the other DNA-based method that we used, i.e., PFGE. Furthermore, no correlation could be found between plasmid profiles and antibiotypes (Table 1).

To date, PFGE is the most powerful method for the analysis of nosocomial isolates because of its high reproducibility and discriminatory power (18, 27). Until now it is recommended as the “gold standard” for defining a clone in various nosocomial bacterial populations. In the present study, we found that almost all strains were clonal and that 80% of all strains were derived from a single clone that caused infection or colonization throughout the year. We evaluated two low-frequency-cleaving enzymes, SpeI and XbaI, and found that the results obtained with both enzymes were equally reproducible but that the results were more easily interpretable with XbaI-resolved fragments (Fig. 1A and B). Moreover, use of the XbaI restriction enzyme was more cost-effective than use of SpeI (about 1/10 the price of SpeI [GIBCO-BRL]).

Our study emphasizes the value of molecular typing methods for detecting the clonalities of strains in the investigation of nosocomial outbreaks caused by E. aerogenes. In conclusion, we found that plasmid profiling and PFGE with XbaI and/or SpeI macrorestriction were both useful for the epidemiologic typing of nosocomial E. aerogenes isolates. In most cases both techniques provided the same information that differentiated the unrelated strains and identified nosocomial outbreak-related organisms. Plasmid profile analysis is faster and requires less expertise than the PFGE method. It is suggested that it can be used as a screening method, whereas PFGE is more confirmatory but requires the use of expensive instruments and more expertise.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank George Zissis for critical review of the manuscript and Olivier Vandenberg and Van den Abbeele Rudy for providing clinical data and cooperation during the preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Vesalius Foundation (foundation for medical research) to Jeanne-Marie Devaster.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arpin C, Coze C, Rogues A M, Gachie J P, Bebear C, Quentin C. Epidemiological study of an outbreak due to multidrug-resistant Enterobacter aerogenes in a medical intensive care unit. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2163–2169. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2163-2169.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bio-Rad Laboratories. GenePath Group 3 Reagent Kit—for use with Pseudomonas, Enterobacter. Catalog no. 310-0004. Bio-Rad Laboratories, Nazareth, Belgium.

- 3.Chow J W, Shlaes D M. Imipenem resistance associated with the loss of a 40 KDa outer membrane protein of Enterobacter aerogenes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991;28:499–504. doi: 10.1093/jac/28.4.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davin-Regli A, Monnet D, Saux P, Bosi C, Charrel R, Barthelemy A, Bollet C. Molecular epidemiology of Enterobacter aerogenes acquisition: one-year prospective study in two intensive care units. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1474–1480. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1474-1480.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Champs C, Henquell C, Guelon D, Sirot D, Gazuy N, Sirot J. Clinical and bacteriological study of nosocomial infections due to Enterobacter aerogenes resistant to imipenem. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:123–127. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.1.123-127.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Champs C, Guelon D, Joyon D, Sirot D, Chanal M, Sirot J. Treatment of a meningitis due to Enterobacter aerogenes producing a derepressed cephalosporinase and a Klebsiella pneumoniae producing an extended-spectrum beta-lactamase. Infection. 1991;19:181–183. doi: 10.1007/BF01643247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Gheldre Y, Maes N, Rost F, De Ryck R, Clevenbergh P, Vincent J L, Struelens M J. Molecular epidemiology of an outbreak of multidrug-resistant Enterobacter aerogenes infections and in vivo emergence of imipenem resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:152–160. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.152-160.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farmer J J., III . Enterobacteriaceae: introduction and identification. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 438–449. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garner J S, Jarvis W R, Emori T G, Horan T C, Hughes J M. CDC definitions for nosocomial infections. Am J Infect Control. 1988;16:128–140. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(88)90053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaston M A. Enterobacter: an emerging nosocomial pathogen. J Hosp Infect. 1988;11:197–208. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(88)90098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Georghiou P R, Hamill R J, Wright C E, Versalovic J, Koeuth T, Watson D A, Lupski J R. Molecular epidemiology of infections due to Enterobacter aerogenes: identification of hospital outbreak-associated strains by molecular techniques. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:84–94. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grattard F, Pozetto B, Tabard L, Petit M, Ros A, Gaudin O G. Characterization of nosocomial strains of Enterobacter aerogenes by arbitrarily primed PCR analysis and ribotyping. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1995;16:224–230. doi: 10.1086/647094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grattard F, Pozzeto B, Berthelot P H, Berthelot P, Rayet I, Ros A, Lauras B, Gaudin O G. Arbitrarily primed PCR, ribotyping, and plasmid pattern analysis applied to investigation of a nosocomial outbreak due to Enterobacter cloacae in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:596–602. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.596-602.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hopkins J M, Towner K J. Enhanced resistance to cefotaxime and imipenem associated with outer membrane protein alterations in Enterobacter aerogenes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;25:49–55. doi: 10.1093/jac/25.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14a.Jalaluddin S, Devaster J-M, Scheen R, Gerard M, Butzler J-P. Abstracts of the 97th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1997. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1997. Molecular epidemiological study of nosocomial infections caused by Enterobacter aerogenes in a Belgian hospital, abstr. L-24; p. 378. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lambert-Zechovsky N, Bingen E, Denamur E, Brahimi N, Brun P, Mathieu H, Elion J. Molecular analysis provides evidence for the endogenous origin of bacteremia and meningitis due to Enterobacter cloacae in an infant. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:30–32. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macrina F L, Kopecko D J, Jones K R, Ayers D J, McCowen S M. A multiple plasmid-containing Escherichia coli strain: conventional source of size reference plasmid molecules. Plasmid. 1978;1:417–420. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(78)90056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maslow J, Mulligan M E. Epidemiologic typing systems. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1996;17:595–604. doi: 10.1086/647395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maslow J N, Slutsky A M, Arbeit R D. Application of pulsed field gel electrophoresis to molecular epidemiology. In: Persing D H, Smith T F, Tenover F C, White T J, editors. Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 563–572. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matushek M G, Bonten M J M, Hayden M K. Rapid preparation of bacterial DNA for pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2598–2600. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2598-2600.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mellencamp M A, Roccaforte J S, Preheim L C, Sanders C C, Anene C A, Bittner M J. Isolation of Enterobacter aerogenes susceptible to beta-lactam antibiotics despite high level beta-lactamase production. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;9:827–830. doi: 10.1007/BF01967384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyers H B, Fontanilla E, Mascola L. Risk factors for development of sepsis in an hospital outbreak of Enterobacter aerogenes. Am J Infect Control. 1988;16:118–122. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(88)90050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility testing. 6th ed. M2A6. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neuwirth C, Siebor E, Lopez J, Pechinot A, Kazmierzak A. Outbreak of TEM-24-producing Enterobacter aerogenes in an intensive care unit and dissemination of the extended-spectrum β-lactamase to other members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:76–79. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.1.76-79.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peele D, Bradfield J, Pryor W, Vore S. Comparison of identifications of human and animal source gram-negative bacteria by API 20E and Crystal E/NF systems. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:213–216. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.213-216.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pitout J D D, Moland E S, Sanders C C, Thomson K S, Fitzsimmons S R. β-Lactamases and detection of β-lactam resistance in Enterobacter spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:35–39. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Portnoy D A, Moseley S L, Falkow S. Characterization of plasmids and plasmid-associated determinants of Yersinia enterocolitica pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 1981;31:775–782. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.2.775-782.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richard V G. Molecular epidemiology of nosocomial infection: analysis of chromosomal restriction fragment patterns by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1993;14:595–600. doi: 10.1086/646645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson A, McCarter Y S, Tetreault J. Comparison of crystal enteric/nonfermenter system, API 20E system, and Vitec automicrobic system for identification of gram-negative bacilli. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:364–370. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.364-370.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanders W E J, Sanders C C. Enterobacter spp.: pathogens poised to flourish at the turn of the century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:220–241. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.2.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Struelens M J, Rost F, Deplano A, Maas A, Schwam V, Serruys E, Cremer M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia after biliary endoscopy: an outbreak investigation using DNA macrorestriction analysis. Am J Med. 1993;95:489–497. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90331-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wauters G, Boel A, Voorn G P, Verhaegen J, Meunier F, Janssens M, Verbist L. Evaluation of a new identification system, Crystal Enteric/Non-Fermenter, for gram-negative bacilli. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:845–849. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.845-849.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. Expert Committee on Biological Standardization. Requirements for antibiotic susceptibility tests. Requirements for Biological Substances No. 26. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1981. [Google Scholar]