Abstract

Chlamydia pneumoniae is an important human respiratory pathogen. Laboratory diagnosis of infection with this organism is difficult. To facilitate the detection of C. pneumoniae by PCR, an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for analysis of PCR products was developed. Biotin-labeled PCR products generated from the 16S rRNA gene of C. pneumoniae were hybridized to a digoxigenin-labeled probe and then immobilized to streptavidin-coated microtiter plates. Bound PCR product-probe hybrids were detected with antidigoxigenin peroxidase conjugate and a colorimetric substrate. This EIA was as sensitive as Southern blot hybridization for the detection of PCR products and 100 times more sensitive than visualization of PCR products on agarose gels. The diagnostic value of the PCR-EIA in comparison to cell culture was assessed in throat swab specimens from children with respiratory tract infections. C. pneumoniae was isolated from only 1 of 368 specimens tested. In contrast, 15 patient specimens were repeatedly positive for C. pneumoniae by PCR and Southern analysis. All of these 15 specimens were also identified by PCR-EIA. Of the 15 specimens positive by 16S rRNA-based PCR, 13 specimens could be confirmed by omp1-based PCR or direct fluorescent-antibody assay. Results of this study demonstrate that PCR is more sensitive than cell culture for the detection of C. pneumoniae. The EIA described here is a rapid, sensitive, and simple method for detection of amplified C. pneumoniae DNA.

Chlamydia pneumoniae has emerged as an important human pathogen in the last decade (10, 13). Pneumonia and bronchitis are the most common clinical manifestations of C. pneumoniae infections. Approximately 10% of cases of community-acquired pneumonia are associated with C. pneumoniae (12, 20). In addition, there is growing evidence that C. pneumoniae may be involved in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, as several studies have demonstrated the presence of the organism in atherosclerotic lesions (4, 18). Infection with C. pneumoniae is common. Since seroepidemiologic studies demonstrated that 50 to 70% of adults have antibody to C. pneumoniae, it is estimated that nearly everyone acquires at least one C. pneumoniae infection during his or her lifetime (25).

Laboratory methods for the diagnosis of C. pneumoniae infection include isolation of the organism in cell culture, serological assays, and DNA amplification tests (10). However, in contrast to C. trachomatis, C. pneumoniae is difficult to recover in cell cultures (17, 21). Despite efforts to improve the sensitivity of cell culture, few isolates of C. pneumoniae have been obtained worldwide. Serologic diagnosis by the microimmunofluorescence test is hampered by the slow antibody response to C. pneumoniae. Detection of a significant increase in antibody levels can take weeks (3, 19). Furthermore, the value of microimmunofluorescence serology has been questioned, since the lack of specific antibodies was observed in sera of patients from whom the organism could be isolated (2, 9).

In contrast to cell culture and serology, PCR provides a more rapid alternative for identification of C. pneumoniae infection. Successful amplification of C. pneumoniae DNA from patient specimens has been reported previously (3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11). However, so far most PCR assays have employed either a labor-intensive or insensitive detection system or they were hampered by a high risk of carryover contamination.

The objective of the present study was to improve the detection of C. pneumoniae by PCR. We developed a rapid and simple enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for detection of amplified C. pneumoniae DNA. This EIA has turned out to be as sensitive as Southern blot hybridization for the analysis of PCR products. In addition, when the diagnostic usefulness of the PCR-EIA was evaluated with throat swab specimens from children with respiratory tract infections the PCR-EIA was superior to cell culture.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and specimens.

Throat swab specimens were collected from hospitalized children with acute lower respiratory tract infections. Specimens were placed into 1.5 ml of sucrose-phosphate-glutamate buffer (pH 7.4) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, gentamicin (50 μg/ml), vancomycin (50 μg/ml), and amphotericin B (2.5 μg/ml). Prior to storage at −75°C a 300-μl aliquot of the patient specimen was withdrawn for PCR analysis.

Cell culture.

Patient specimens were thawed, vortexed, and sonicated briefly. Aliquots (100 μl) of each sample were inoculated in duplicate onto HEp-2 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) grown in two 96-well culture plates (Corning Costar, Bodenheim, Germany). Plates were centrifuged at 1,340 × g at 30°C for 1 h. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, the inoculum was replaced by 200 μl of Eagle’s minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 25 mM HEPES, 56 mM glucose, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1% (vol/vol) nonessential amino acids, 1% (vol/vol) vitamins, gentamicin (50 μg/ml), amphotericin B (2.5 μg/ml), and cycloheximide (1.5 μg/ml). Cultures were incubated for 72 h at 36°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The monolayers of one plate were fixed with methanol and stained for chlamydial inclusions with a fluorescein-conjugated genus-specific antibody to the Chlamydia lipopolysaccharide (Sanofi diagnostics Pasteur, Freiburg, Germany). On subsequent passages isolates were identified as C. pneumoniae by staining with a fluorescein-conjugated species-specific antibody (catalog no. K 6601; DAKO, Hamburg, Germany). Inclusion-negative cultures were passaged once. After freezing at −75°C, cultures were thawed and the cells were scraped off. Cell suspensions were transferred to microcentrifuge tubes, sonicated, and then inoculated onto new HEp-2 cells as described above.

C. pneumoniae TW-183 (Washington Research Foundation, Seattle, Wash.) was grown to high titers in cycloheximide-treated HEp-2 cells (21). Titrations of freshly harvested organisms were done in triplicate in shell vials as described previously (15).

Primers and probes.

The 16S rRNA gene and the major outer membrane protein gene (omp1) were used as targets for amplification of C. pneumoniae DNA. Oligonucleotide primers were synthesized and purified as described previously in detail (14). Patient specimens were routinely screened for C. pneumoniae by PCR with primers directed to the 16S rRNA gene. Primer CpnA and the biotinylated primer CpnB were used to amplify a 465-bp segment from the 16S rRNA gene of C. pneumoniae (Table 1) (7, 8). Primers CpnA and CpnF were used to generate a 446-bp internal probe, which was labeled by incorporation of digoxigenin (DIG)-11-dUTP during PCR (PCR DIG Labeling Mix; Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). This probe was used for the detection of PCR products by Southern hybridization and EIA.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligo- nucleotide | Position (5′-3′) | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| CpnA | 1012–1032a | TGACAACTGTAGAAATACAGC |

| CpnB | 1476–1459a | Biotin-CGCCTCTCTCCTATAAAT |

| CpnF | 1457–1437a | GGTTGAGTCAACGACTTAAGG |

| CP1 | 61–80b | TTACAAGCCTTGCCTGTAGG |

| CP2 | 393–373b | GCGATCCCAAATGTTTAAGGC |

| CPC | 100–120b | TTATTAATTGATGGTACAATA |

| CPD | 306–286b | ATCTACGGCAGTAGTATAGTT |

All specimens positive by 16S rRNA-based PCR were subjected to a confirmatory nested PCR with omp1-based primers (24). The external primers CP1 and CP2 amplified a 333 bp-fragment from the omp1 gene of C. pneumoniae. A 207-bp sequence of this PCR product was amplified in a second PCR with the internal primers CPC and CPD.

PCR.

A 300-μl aliquot of the patient specimen or 100 μl of serial 10-fold dilutions of C. pneumoniae TW-183 was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 30 min. The resulting pellet was treated with 100 μl of proteinase K-detergent buffer (PCR buffer with proteinase K [200 μg/ml], 0.5% Tween 20, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40) for 1 h at 58°C (15). After inactivation of proteinase K for 10 min at 98°C, specimens were placed on ice.

A 10-μl aliquot of proteinase K-treated clinical specimen or chlamydial suspension was processed in a 100-μl reaction volume containing PCR buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl); 200 μM dATP, dCTP, and dGTP; 400 μM dUTP; 2.5 mM MgCl2; a 0.5 μM concentration of each primer; 1.5 U of AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Weiterstadt, Germany); and 1 U of a heat-labile uracil-N-glycosylase (UNG) (Boehringer) (23). Amplifications were carried out in a GeneAmp 9600 DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer). To degrade contaminating amplification products from previous PCRs with UNG, reaction volumes were first incubated at 25°C for 10 min and then heated for 2 min at 95°C to inactivate the UNG. Forty amplification cycles of 15 s at 94°C, 15 s at 55°C, and 35 s at 72°C followed. After the last cycle, samples were incubated for 10 min at 72°C. If samples were not analyzed immediately, they were stored at −20°C. In the first round of amplification, patient specimens were tested for the presence of inhibitors. A 10-μl sample was withdrawn from the proteinase K-treated patient specimen, spiked with the DNA from approximately 1 inclusion-forming unit (IFU) of C. pneumoniae, and amplified by PCR. Specimens that did not yield a visible band after PCR on an ethidium bromide (EtBr)-stained agarose gel were subjected to phenol-chloroform extraction. Two positive controls containing the DNA from ∼7 and ∼0.7 IFU of C. pneumoniae and several randomly positioned negative controls (proteinase K detergent buffer) were included in each run. Negative controls were processed together with the patient specimens starting with the proteinase K treatment. Positive controls were handled separately. All specimens were analyzed twice by 16S rRNA-based PCR. When a sample was positive in only one of these two PCR runs, two additional assays were performed.

In addition to the dUTP-UNG protocol, precautions to prevent amplicon carryover included the setup and analysis of PCRs in separate rooms, use of positive-displacement pipettes and aerosol-resistant pipette tips, and UV irradiation of working places and laboratory equipment.

Analysis of PCR products by Southern blot hybridization.

PCR products (10 μl) were separated on 1.5% agarose gels and then transferred to nylon membranes (Boehringer) by capillary blotting. Hybridizations to the DIG-labeled 446-bp probe were carried out according to standard procedures (22). The probe-PCR product hybrid was visualized with anti-DIG alkaline phosphatase conjugate and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate toluidinium–nitroblue tetrazolium as the colorimetric substrate (DIG Nucleic Acid Detection Kit; Boehringer).

Detection of PCR products by EIA.

A 40-μl aliquot of the PCR product was mixed with 80 μl of 1× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.5% Tween 20 containing the DIG-labeled 446-bp probe (300 ng/ml). Denaturation (94°C for 15 min) and hybridization (68°C for 60 min) were carried out in solution in the thermal cycler. A 50-μl aliquot of the reaction volume was then transferred in duplicate to the wells of streptavidin-coated microtiter plates (Labsystems, Frankfurt, Germany) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Plates were washed twice with 200 μl of 0.1× SSC–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and two times with 200 μl Tris-buffered saline (TBS) (100 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl [pH 7.5])–0.05% Tween 20. A 50-μl aliquot of anti-DIG peroxidase conjugate (Boehringer) diluted 1:1,000 in TBS–1% bovine serum albumin–0.3% Tween 20 was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After four washes with 200 μl of TBS–0.05% Tween 20, color was developed by the addition of 50 μl of tetramethylbenzidine (Boehringer). Color development was stopped after incubation for 15 min at 37°C by the addition of 1 N H2SO4. Three positive controls consisting of serial 10-fold dilutions of PCR products generated from 4 IFU of C. pneumoniae and four negative controls (water) were included in each assay. The A450 of each specimen was determined with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reader as a net value after subtracting the A450 of the blank.

Analysis of discrepant results.

Specimens that were culture-negative but PCR-EIA positive were analyzed further by a direct fluorescent-antibody assay (DFA) and nested PCR (9, 24). For DFA, a 200-μl aliquot of the original specimen was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 30 min. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 20 μl of phosphate-buffered saline and examined with a genus-specific fluorescent monoclonal antibody. Specimens were examined by an experienced technician and scored a positive when two or more elementary bodies were clearly visible.

Specimens positive by 16S rRNA-based PCR were confirmed by a nested PCR with primers which amplify sequences from the omp1 gene of C. pneumoniae (24). PCR amplification products generated from the omp1 gene were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

A specimen was considered positive if it was cell culture positive. In addition, a culture-negative but 16S rRNA-based PCR-positive specimen was considered to be a true positive only if it could be verified by omp1-based PCR or DFA.

RESULTS

Detection of amplified C. pneumoniae DNA.

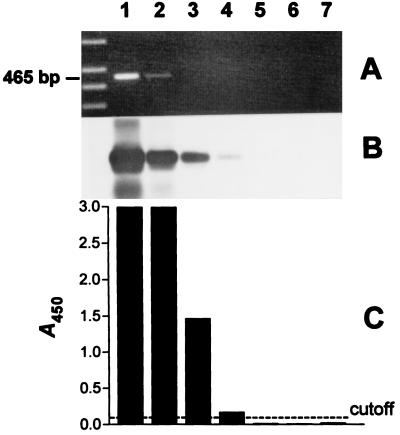

The target for detection of C. pneumoniae in clinical specimens was the 16S rRNA gene (8). We used a biotinylated and a nonbiotinylated primer for the amplification of a 465-bp fragment from the 16S rRNA gene. After amplification biotinylated PCR products were hybridized in solution to a DIG-labeled 446-bp internal probe and then were immobilized to streptavidin-coated microtiter wells and detected with anti-DIG peroxidase conjugate and a colorimetric substrate. All incubation steps and reaction components of this EIA were optimized prior to use with clinical specimens. To compare the level of detection of this assay with the sensitivities of EtBr staining of agarose gels and Southern blot hybridization, serial 10-fold dilutions of PCR products were analyzed in parallel by all three methods. In repeated experiments the EIA was as sensitive as Southern blot hybridization for the detection of PCR products from C. pneumoniae. Both methods were approximately 100 times more sensitive than EtBr staining of agarose gels (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of EtBr staining of agarose gel, Southern blot hybridization, and EIA for the detection of PCR products generated from C. pneumoniae DNA. A 465-bp sequence was amplified from the 16S rRNA gene of C. pneumoniae. PCR products were serially diluted 10-fold (lanes 1 to 7 [lane 1, undiluted; lane 2, 10-fold diluted, etc.]) and analyzed in parallel by all three detection methods. (A) EtBr-stained agarose gel (leftmost lane, DNA molecular weight marker); (B) Southern blot; (C) A450 of PCR products from panel B, obtained by EIA. Cutoff = 0.100.

Control of carryover contamination with UNG.

A heat-labile UNG was used to degrade contaminating amplification products from previous PCRs in the reaction mixtures (23). To determine whether the use of dUTP instead of dTTP had influenced the sensitivity of the PCR, amplifications were carried out with either dTTP or dUTP. The use of dUTP did not lead to a decrease of the sensitivity of the PCR (data not shown). To assess the efficiency of UNG inactivation, 10-μl aliquots of serial 10-fold dilutions of PCR products from the amplification of 4 IFU of C. pneumoniae were treated with 1, 0.5, 0.1, or 0.05 U of heat-labile UNG before reamplification. When reaction mixtures were incubated with 1 or 0.5 U of UNG, reamplification products were not detected by Southern analysis in all specimens tested. Incubation of reaction mixtures with 0.1 or 0.05 U of UNG did not prevent the reamplification of PCR products. In addition, UNG treatment did not influence the sensitivity of the PCR (data not shown).

Detection of C. pneumoniae in clinical specimens. (i) Cell culture.

A total of 368 throat swab specimens from children with lower respiratory tract infections were inoculated onto cycloheximide-treated HEp-2 cells. C. pneumoniae was isolated from only one of these specimens at the first passage.

(ii) PCR-EIA.

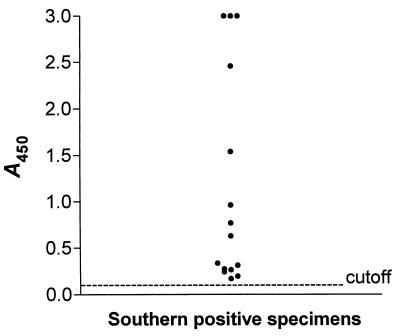

In addition to being examined by cell culture, specimens were examined for the presence of C. pneumoniae by 16S rRNA-based PCR. All specimens were routinely tested in two PCR assays. C. pneumoniae sequences amplified from the 16S rRNA gene were detected by EtBr staining of agarose gels, Southern blot hybridization, and EIA. Analysis of specimens by EIA was done blinded. A total of 15 specimens, including the culture-positive sample, were positive by 16S rRNA-PCR and Southern blot hybridization (Table 2). When a cutoff value of 0.100 was used, we found complete agreement between the results of Southern analysis and the EIA. The distribution of the A450 of Southern blot-positive specimens is shown in Fig. 2. The lowest A450 of a positive specimen was 0.171. The highest A450 of a Southern-blot negative specimen was 0.067. Thus, Southern blot-positive and -negative specimens were clearly distinguishable by the EIA. In contrast to Southern blot hybridization and EIA, EtBr staining of PCR products on agarose gels was much less sensitive. A band of the expected size was visible on the gel in only 8 (53%) of the Southern blot- and EIA-positive specimens (Table 2). Of 15 specimens that tested positive by 16S rRNA-based PCR, 11 were positive in two consecutive runs. The remaining four samples were positive in only one of two assays. For these samples one or two additional PCR runs with primers specific for the 16S rRNA gene were needed to obtain a second positive result.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of methods for detection of amplified C. pneumoniae DNA from 368 clinical specimens

| Method | No. (%) of clinical specimens with resulta

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | |

| Southern analysis | 15 (4) | 353 (96) |

| EIA | 15 (4) | 353 (96) |

| EtBr staining | 8 (2) | 360 (98) |

The results are from two runs.

FIG. 2.

Distribution of the A450 obtained by EIA of 15 clinical specimens which were positive by Southern blot hybridization. Cutoff = 0.100.

Altogether, 14 specimens were culture negative but positive by 16S rRNA-based PCR. These specimens were analyzed further by DFA and a nested PCR with primers specific for omp1. Of the 14 specimens, 12 could be confirmed as positive by omp1-based PCR and 10 were positive by DFA. The remaining 2 PCR-positive, culture-negative samples were negative by both omp1-based PCR and DFA. Therefore, these specimens were taken to be false positives (Table 3). The sensitivity of the PCR-EIA was 100%, and the specificity was 99.4%. The positive and negative predictive values of the PCR-EIA were 86.6 and 100%, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Test results of clinical specimens positive by 16S rRNA-based PCR-EIA

| Specimen no. | Result byc:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell culture | 16S rRNA-based PCRa | omp1-based PCR | DFA | |

| 1 | + | + (2) | + | + |

| 2 | − | + (2) | + | + |

| 3 | − | + (2) | + | + |

| 4 | − | + (4) | + | + |

| 5 | − | + (2) | + | + |

| 6 | − | + (4) | + | + |

| 7 | − | + (2) | + | + |

| 8 | − | + (2) | + | + |

| 9 | − | + (3) | + | + |

| 10 | − | + (2) | + | + |

| 11 | − | + (4) | + | + |

| 12 | − | + (2) | + | − |

| 13 | − | + (2) | + | − |

| 14 | − | + (2)b | − | − |

| 15 | − | + (2)b | − | − |

Numbers in parentheses are the number of assays needed to obtain two positive results.

False-positive result, because confirmatory omp1-based PCR and DFA were negative.

+, positive in assay; −, negative in assay.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, C. pneumoniae was detected in throat swab specimens from pediatric patients with lower respiratory tract infections by PCR-EIA and by isolation in cell culture. The organism was recovered in culture from only 1 of 368 specimens tested. The reasons for the low sensitivity of culture in this study are unknown. Sensitivity of cell culture depends on a number of factors, such as sufficient numbers of viable chlamydiae, collection method, transport and storage conditions of specimens, and choice of cell lines. We examined throat swab specimens, and it is possible that these samples did not include enough cells which harbored the organism. We cannot exclude the possibility that the isolation rate of C. pneumoniae might have been higher with other types of specimens. Comparative studies on the relative efficacy of throat swab, nasopharyngeal swab, and sputum samples for recovery of C. pneumoniae from culture revealed that positive results were most frequently obtained with sputum specimens (3). Furthermore, prolonged storage of specimens at −75°C might have influenced the viability of organisms. It has been previously demonstrated that freezing results in the loss of a significant proportion of C. pneumoniae (17). While this work was in progress it was reported that pretreatment of clinical specimens with trypsin leads to an increase in the isolation rate of C. pneumoniae (16). It remains to be determined in further studies whether this method will prove to be an efficient technique for recovery of C. pneumoniae from clinical specimens.

In contrast to the cell culture results, C. pneumoniae was detected by 16S rRNA-based PCR in 15 out of 368 specimens (Tables 2 and 3). Eleven of these samples were positive in two consecutive assays. For the remaining 4 samples, either three or four runs were necessary to obtain a second positive test result, which might have been due to a low number and/or unequal distribution of organisms in these samples. Of 15 specimens positive by 16S rRNA-based PCR, 13 could be confirmed as true positives by omp1-based PCR and 11 were positive by DFA. Two 16S rRNA-based PCR-positive specimens were negative by either omp1-based PCR or DFA and were taken to be false positives. In our study, patient specimens containing inhibitors were identified by monitoring the amplification of DNA from C. pneumoniae TW-183, which was added to a duplicate test sample. Therefore, it is possible that despite strict precautions the false-positive samples might have been contaminated with natural C. pneumoniae DNA during the setup of the reaction mixtures. To eliminate this possible source of contamination, we have constructed an internal control for monitoring PCR inhibition (our unpublished observations).

In the present study the 16S rRNA gene was used as the target for detection of C. pneumoniae (7, 8). Other targets commonly used for identification of C. pneumoniae are the omp1 gene and a specific DNA fragment (5, 24). Various PCR procedures for detection of C. pneumoniae by different detection systems are under investigation. However, these assays have not yet been compared with each other. Nested PCRs with omp1- or 16S rRNA-based primers have been reported to be more sensitive than single-step PCR (1, 3). At least part of this difference in sensitivity may be due to the use of agarose gel analysis for detection of PCR products, a method which lacks sensitivity. A serious disadvantage of nested PCRs is the high risk of carryover contamination. In our study omp1-based nested PCR was found to be useful only as a confirmatory test but not for routine testing of specimens. Furthermore, UNG, which destroys products from previous amplifications, can be used in a nested PCR only in the second round of amplification. This is the first PCR assay for detection of C. pneumoniae which includes a dUTP-UNG system for carryover prevention. We used a new heat-labile UNG. This UNG from a marine bacterium is inactivated more rapidly by heat and shows much less residual activity than the corresponding enzyme from Escherichia coli (23). The dUTP-UNG protocol was found to be highly efficient and had no negative effect on the sensitivity of the PCR.

A major objective of our study was the development and evaluation of a rapid, simple, and sensitive detection system for amplified C. pneumoniae DNA. Our previous studies with primers derived from a specific DNA fragment of C. pneumoniae suggested, when throat swab specimens were examined, that a single-step PCR followed by agarose gel analysis of PCR products lacks sensitivity (15). Since Southern analysis is too labor-intensive for routine use in diagnostic laboratories, an EIA for detection of PCR products was established. Detection of amplified C. pneumoniae sequences by EIA has been reported previously by Gaydos and coworkers (6). Compared to our assay, the EIA performed by Gaydos is a more complicated detection method, requiring the labor-intensive production and purification of an RNA probe. One of the advantages of our system is its simplicity. For example the DIG-labeled probe used for detection of PCR products can be easily generated by PCR. Results obtained with our EIA were compared to those obtained by EtBr staining of PCR products on agarose gels and Southern blot hybridization and demonstrated the high sensitivity of this detection system. When serial dilutions of PCR products from C. pneumoniae were analyzed, Southern analysis and EIA were equally sensitive and both were at least 100 times more sensitive than agarose gel electrophoresis and EtBr staining (Fig. 1). When clinical specimens were examined for the presence of C. pneumoniae, there was complete agreement between the results of Southern analysis and EIA. A total of 15 specimens were positive both by Southern hybridization and by EIA. In contrast, in only 8 of these specimens was a band of the expected size visible on EtBr-stained agarose gels (Table 2). These findings may be attributable to low numbers of chlamydiae in the specimens and/or inefficient amplification due to the presence of PCR inhibitors. Nevertheless, these observations clearly demonstrate that detection of PCR products on agarose gels is not sensitive enough for detection of C. pneumoniae sequences which were amplified by single-step PCR from throat swab specimens.

In conclusion, our study confirms and extends findings of previous studies which have demonstrated that PCR is more sensitive than cell culture for the detection of C. pneumoniae in clinical specimens. We developed and evaluated a new EIA for the analysis of amplified C. pneumoniae DNA. The advantages of this EIA are its simplicity, the use of a carryover prevention system, and its high sensitivity. This assay is comparable in sensitivity to Southern analysis but is less labor-intensive and much faster. Results of specimens which do not contain inhibitors can be obtained within 1 day. We hope that this assay will help to facilitate the diagnosis of C. pneumoniae infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the FAZIT-Stiftung and the Verband der Chemischen Industrie to J.H.H.

We thank Margit Pohl for excellent technical assistance and Ursula Fleig for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Black C M, Fields P I, Messmer T O, Berdal B P. Detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae in clinical specimens by polymerase chain reaction using nested primers. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:752–756. doi: 10.1007/BF02276060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Block S, Hedrick J, Hammerschlag M R, Cassell G H, Craft J C. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae in pediatric community-acquired pneumonia: comparative efficacy and safety of clarithromycin vs. erythromycin ethylsuccinate. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:471–477. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199506000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boman J, Allard A, Persson K, Lundborg M, Juto P, Wadell G. Rapid diagnosis of respiratory Chlamydia pneumoniae infection by nested touchdown polymerase chain reaction compared with culture and antigen detection by EIA. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1523–1526. doi: 10.1086/516492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell L A, O’Brien E R, Cappuccio A L, Kuo C C, Wang S P, Stewart D, Patton D L, Cummings P K, Grayston J T. Detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae TWAR in human coronary atherectomy tissues. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:585–588. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.2.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell L A, Perez Melgosa M, Hamilton D J, Kuo C C, Grayston J T. Detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:434–439. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.2.434-439.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaydos C A, Fowler C L, Gill V J, Eiden J J, Quinn T C. Detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae by polymerase chain reaction-enzyme immunoassay in an immunocompromised population. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:718–723. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.4.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaydos C A, Palmer L, Quinn T C, Falkow S, Eiden J J. Phylogenetic relationship of Chlamydia pneumoniae to Chlamydia psittaci and Chlamydia trachomatis as determined by analysis of 16S ribosomal DNA sequences. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:610–612. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-3-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaydos C A, Quinn T C, Eiden J J. Identification of Chlamydia pneumoniae by DNA amplification of the 16S rRNA gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:796–800. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.4.796-800.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaydos C A, Roblin P M, Hammerschlag M R, Hyman C L, Eiden J J, Schachter J, Quinn T C. Diagnostic utility of PCR-enzyme immunoassay, culture, and serology for detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:903–905. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.903-905.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grayston J T. Infections caused by Chlamydia pneumoniae strain TWAR. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:757–761. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.5.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grayston J T, Aldous M B, Easton A, Wang S P, Kuo C C, Campbell L A, Altman J. Evidence that Chlamydia pneumoniae causes pneumonia and bronchitis. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1231–1235. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.5.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grayston J T, Diwan V K, Cooney M, Wang S P. Community- and hospital-acquired pneumonia associated with Chlamydia TWAR infection demonstrated serologically. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:169–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grayston J T, Kuo C C, Wang S P, Altman J. A new Chlamydia psittaci strain, TWAR, isolated in acute respiratory tract infections. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:161–168. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198607173150305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jantos C A, Heck S, Roggendorf R, Sen-Gupta M, Hegemann J H. Antigenic and molecular analyses of different Chlamydia pneumoniae strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:620–623. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.620-623.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jantos C A, Wienpahl B, Schiefer H G, Wagner F, Hegemann J H. Infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae in infants and children with acute lower respiratory tract disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:117–122. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199502000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kazuyama Y, Lee S M, Amamiya K, Taguchi F. A novel method for isolation of Chlamydia pneumoniae by treatment with trypsin or EDTA. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1624–1626. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1624-1626.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuo C C, Grayston J T. Factors affecting viability and growth in HeLa 229 cells of Chlamydia sp. strain TWAR. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:812–815. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.5.812-815.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuo C C, Grayston J T, Campbell L A, Goo Y A, Wissler R W, Benditt E P. Chlamydia pneumoniae (TWAR) in coronary arteries of young adults (15–34 years old) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6911–6914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuo C C, Jackson L A, Campbell L A, Grayston J T. Chlamydia pneumoniae (TWAR) Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:451–461. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marrie T J, Grayston J T, Wang S P, Kuo C C. Pneumonia associated with the TWAR strain of Chlamydia. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:507–511. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-4-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roblin P M, Dumornay W, Hammerschlag M R. Use of HEp-2 cells for improved isolation and passage of Chlamydia pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1968–1971. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.8.1968-1971.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook J, Maniatis T, Fritsch E. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobek H, Schmidt M, Frey B, Kaluza K. Heat-labile uracil-DNA glycosylase: purification and characterization. FEBS Lett. 1996;388:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00444-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tong C Y, Sillis M. Detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae and Chlamydia psittaci in sputum samples by PCR. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46:313–317. doi: 10.1136/jcp.46.4.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang S P, Grayston J T. Population prevalence antibody to Chlamydia pneumoniae, strain TWAR. In: Bowie W R, Caldwell H D, Jones R P, Mardh P-A, Ridgway G L, Schachter J, Stamm W E, Ward M E, editors. Chlamydial infections. Proceedings of the Seventh International Symposium on Human Chlamydial Infections. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 402–405. [Google Scholar]