Abstract

Sweet Syndrome presents as acute fever, leucocytosis and characteristic skin plaques. It can involve many organ systems but rarely affects the nervous system. We report the case of a 51-year-old female that presented with fever, rash, headache and encephalopathy. Brain magnetic resonance imaging showed extensive T2 hyperintensities involving cerebral hemispheres, cerebellum, and brainstem. A skin biopsy revealed dermal infiltration by neutrophils consistent with Sweet Syndrome. She started steroid treatment with a good clinical response. Further questioning revealed that she had a similar episode 10 years prior that had been diagnosed as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Neuro-Sweet Syndrome can present with a great array of symptoms and relapses over long periods of time making the diagnosis difficult without a high degree of suspicion. Clinicians should consider this syndrome in the setting of acute encephalitis with white matter lesions that are highly responsive to steroids particularly in the presence of previous similar symptoms.

Keywords: sweet syndrome, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, magnetic resonance imaging, delayed diagnosis

Background

Sweet syndrome (SS), or acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is a syndrome consisting of the acute onset of fever, leukocytosis and characteristic tender, erythematous plaques, and nodules. Histologically, the skin lesions are comprised of dermal infiltration by neutrophils without epidermal involvement or evidence of vasculitis. 1

First described in 1999, neurologic involvement in Sweet Syndrome is rare with fewer than 70 cases reported in the literature.2,3 Neuro-Sweet syndrome (NSS) refers to the neurological manifestations of Sweet Syndrome and most commonly presents with encephalitis and aseptic meningitis. 4 Neurologic symptoms vary at presentation depending on the regions involved, but headache and altered mental status are most common. Imaging findings most commonly demonstrate asymmetric signal abnormalities particularly involving the brainstem, cortex and thalamus. 4 CSF findings include increased protein concentration and pleocytosis. 4 The clinical and imaging findings have significant overlap with other entities including viral encephalitis, systemic autoimmune disorders (Behcet’s disease in particular) and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) which can delay diagnosis and appropriate treatment. 3

Case

A 51-year-old woman of Japanese and German descent, with a remote episode of diplopia, disequilibrium, headache, confusion and fever ten years prior, was transferred from another hospital for evaluation and treatment of presumed Japanese encephalitis.

She had travelled to Thailand a month earlier and developed symptoms of upper respiratory infection at the conclusion of her ten-day trip. Three weeks prior to admission, upon returning to the United States, she developed fevers, headache, blurry and double vision, dizziness, a purpuric rash and periorbital edema. Prior to being transferred to our hospital, she became increasingly encephalopathic, with fevers exceeding 41°C, leukocytosis of 16,000 and elevated protein in her cerebrospinal fluid.

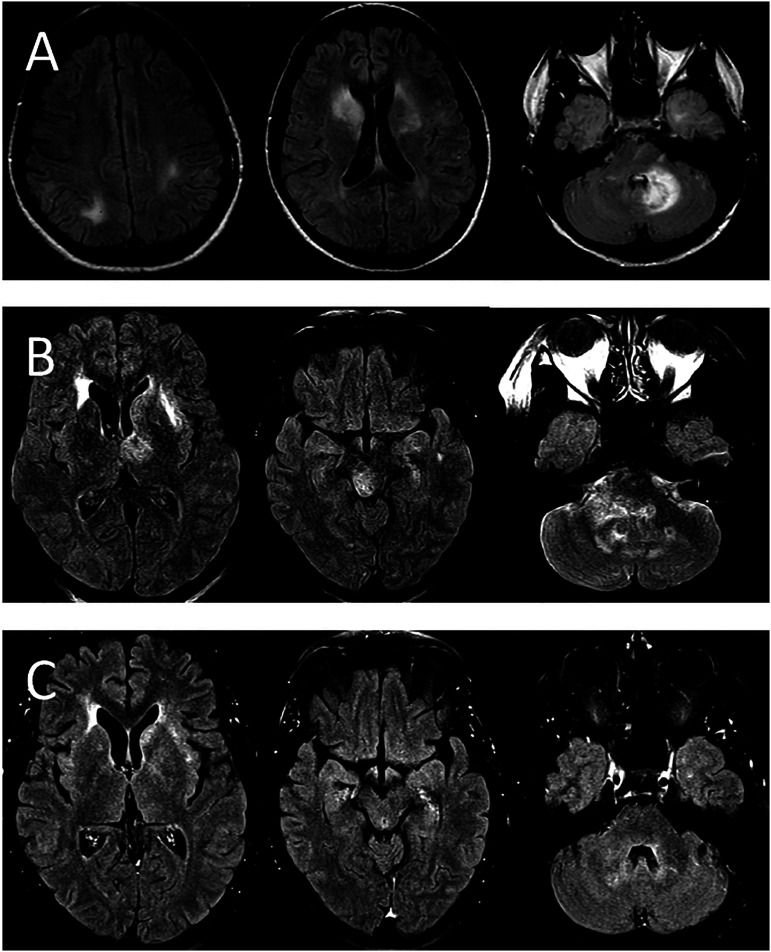

She had developed multiple small, round purpuric cutaneous lesions on her left shoulder, left breast and right hand. Despite her having no recollection of being bitten by insects, these were presumed to be insect bites and a provisional diagnosis of Japanese encephalitis was made. A brain MRI was performed which showed extensive T2 hyperintensities involving the bilateral cerebral hemispheres, cerebellum and brainstem (Figure 1A). She was started on empiric intravenous antibiotics as well as acyclovir with no improvement and was eventually transferred to our hospital.

Figure 1.

MRI imaging from both of the patient’s neurologic presentations. (A) Selected FLAIR images from the patient’s MRI from her most recent presentation. There are bilateral FLAIR hyper-intense lesions with associated vasogenic edema and local mass effect, this time predominantly involving the left thalamus, left basal ganglia, right brainstem and right cerebellar hemisphere. No diffusion restriction or enhancement is present. (B) Selected FLAIR images are shown from an MRI from the patient’s first episode 10 years prior. Multiple FLAIR hyper-intense lesions are seen predominantly affecting the bilateral right greater than left basal ganglia and left cerebellar hemisphere. No diffusion restriction or enhancement was seen. (C) Selected FLAIR images at similar levels from the follow-up MRI approximately 1 month after initial presentation following treatment with steroids. These images demonstrate near complete interval resolution of the FLAIR signal abnormalities, edema and regional mass effect.

By the time the patient arrived at our facility her symptoms had substantially improved. Her fever, headache, and diplopia had completely resolved, although her purpuric skin lesions remained. Cognitive exam was normal aside from some distractibility and disinhibition. Strength, coordination and sensory exams were fully intact despite the diffuse MRI findings.

It was discovered that the patient had been given IV dexamethasone the night before her transfer and this was believed to be the source of her rapid improvement. She also described a transient improvement 2 weeks earlier after receiving antibiotics and a 5-day oral prednisone course from an urgent care facility for suspected pneumonia.

Further questioning revealed that the patient had a similar presentation approximately 10 years prior. MRI images from this episode revealed similar ill-defined T2 hyperintensities with local edema and mass effect (Figure 1B). She was initially treated for bacterial meningitis, but eventually received IV corticosteroids and IVIG with complete symptom resolution. She was diagnosed with ADEM during that admission. The patient recalled that she had similar skin lesions at that time, although they were not investigated.

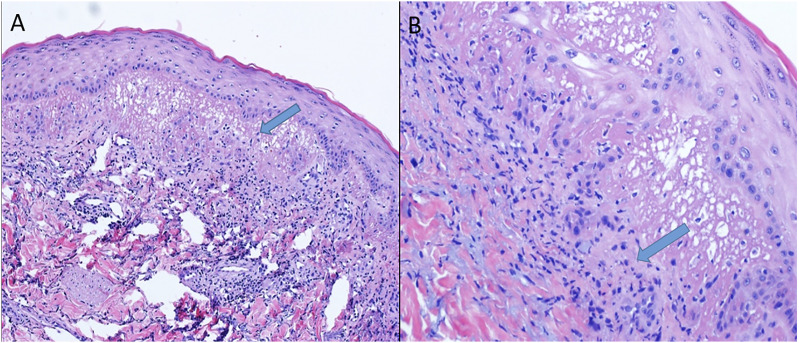

A skin biopsy obtained during her most recent hospitalization demonstrated dermal infiltration by neutrophils characteristic of Sweet Syndrome (Figure 2). A cerebral angiogram performed to rule out a systemic vasculitis process such as Behcet’s disease was normal. A leptomeningeal-brain biopsy was not performed as the patient already fulfilled criteria for probable NSS.

Figure 2.

Skin biopsy, H&E stain. (A) 10X and (B) 40X magnification images showing superficial dermal edema with dense neutrophilic infiltrate and karyorrhexis.

The patient was discharged on a steroid taper. Her repeat MRI brain 1 month later showed near complete interval resolution of the FLAIR signal abnormalities, edema and regional mass effect (Figure 1C). At follow up 2 months after initial presentation, she had completed her steroid taper and experienced complete return to her neurologic baseline.

Discussion

Sweet syndrome (SS) usually affects individual in their sixth decade of life and predominantly impacts females in a 4:1 distribution. 5 SS can present as an idiopathic disease or in association with drugs, such as colony stimulating factors, oral tretinoin, chemotherapies and antimicrobials; infections, mainly involving the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract, malignancy, inflammatory conditions, and pregnancy. 6 It can affect multiple organs besides the skin including liver, heart, lung, mouth, bones, central nervous system although most commonly affect the eyes in 17-72% of cases. 1 Neurologic involvement is uncommon and has been mainly reported in Asian population. 3

Neuro-Sweet Syndrome (NSS) affects males and females with a similar frequency, and it encompasses a wide age range affecting individuals from 7 weeks to 76 years, although most commonly manifesting near the fifth decade of life. 3 NSS can present in association with various types of cancers and inflammatory conditions, although this association seems infrequent. In our case, the patient presented symptoms of SS 10 days after experiencing a probable upper respiratory infection, this is consistent with the usual timeline of the disease with the infection preceding the SS manifestations by 1-3 weeks. 3

NSS involves a myriad of neurologic manifestations that include headaches, altered mental status, seizures, focal weakness, ataxia, dysarthria, as well as psychiatric and movement disturbances. These symptoms usually present after the development of skin lesions but can present before, concomitantly or without them. The disease can be self-remitting but frequently relapses over time and can uncommonly result in residual neurologic sequelae like memory disturbances, focal neurologic impairment and depression.3,7 The case presented here is consistent with a relapse of the disease 10 years after an initial presentation that was diagnosed as ADEM and brings to notice the underrecognition of the disease and the importance of considering the possibility of a relapse even after a long-term period in patients with NSS.

The use of diagnostic support methods is not always helpful as many features of the disease are nonspecific. MRI findings typically appear as T2/FLAIR hyperintense lesions or contrast enhancing lesions with no predilection for a location in the CNS. CSF analysis can be normal or show mild elevation of proteins or leucocytes particularly lymphocytes. The presence of oligoclonal bands, immunoglobulins or elevation in the IgG index has also been reported. Skin biopsy in patients with SS usually reveals dermal neutrophilic infiltrate commonly with nuclear fragmentation and absence of vasculitis. In contrast, the few pathological reports of central nervous tissue in NSS demonstrated neutrophilic infiltrate of blood vessels with vasculitis probably as a manifestation of an active process underlying the disease.6,8

The diagnosis of NSS can be difficult and requires a high degree of suspicion. In 2005, Hisanaga developed diagnostic criteria based on a cohort of Japanese patients. 4 These criteria consider (1) the presence of neurologic features responsive to steroid treatment, (2) dermatological manifestations, (3) absence of uveitis or cutaneous vasculitis typical of Behçet’s disease and (4) the identification of HLA-Cw1 or HLA-B54. Patients who fulfil the first 3 items are diagnosed with probable NSS. However, the applicability of these criteria in different populations has yet to be proved. 7 The differential diagnosis of NSS is broad as this disorder can mimic several conditions like autoimmune disease, especially Neuro Behçet’s Disease (NBD), demyelinating conditions and viral encephalitis. 9 As they share many common characteristics, NBD should be considered in the diagnostic process. Importantly, NBD usually presents with a typical uveitis, vasculitis in skin biopsies and carries a worse prognosis than NSS. 7

SS is responsive to steroids in most reports and doses of 1 mg/kg/d of prednisone tapered to 10 mg/day by 4-6 weeks have been frequently used. In a similar fashion, most cases of NSS have been successfully treated with steroids. 3 Alternatives to the use of steroids include common immunosuppressants like cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, tacrolimus and azathioprine as well as other medications like indomethacin, colchicine and acitretin. 5 A recent study using the latter showed a 70% remission rate in 2 weeks although these patients did not have neurologic involvement. 10 It is believed that this response is based on its ability to prevent neutrophil migration making it an appealing choice for avoiding immunosuppressants. 11 There have also been reports of remission of the disease by treating the underlying neoplastic disorder or discontinuing the offending drug.3,5

This case highlights the difficulty in making an accurate diagnosis of NSS as it is a rare entity that can have significant overlap with other conditions including viral encephalitis, ADEM and systemic autoimmune conditions. In fact, our patient had at least 1 prior treated episode that was labelled as ADEM, further emphasizing the importance of an accurate diagnosis to prevent delays in appropriate management. NSS should be considered in the differential of acute encephalitis with white matter lesions that are highly responsive to steroids, particularly in the setting of purpuric skin lesions, and biopsy of these lesions is key for differentiation from other neurocutaneous disorders such as Behcet’s disease. 3

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from the patient before the submission of this article.

ORCID iD

Karlos Acurio https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0550-5190

References

- 1.Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome--a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:34. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hisanaga K, Hosokawa M, Sato N, Mochizuki H, Itoyama Y, Iwasaki Y. Neuro-sweet disease”: Benign recurrent encephalitis with neutrophilic dermatosis. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(8):1010-1013. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.8.1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drago F, Ciccarese G, Agnoletti AF, Sarocchi F, Parodi A. Neuro sweet syndrome: A systematic review. A rare complication of sweet syndrome. Acta Neurol Belg. 2017;117(1):33-42. doi: 10.1007/s13760-016-0695-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hisanaga K, Iwasaki Y, Itoyama Y, Neuro-Sweet Disease Study Group . Neuro-sweet disease: Clinical manifestations and criteria for diagnosis. Neurology. 2005;64(10):1756-1761. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000161848.34159.B5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joshi TP, Friske SK, Hsiou DA, Duvic M. New practical aspects of sweet syndrome. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(3):301-318. doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00673-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallach AI, Magro CM, Franks AG, Shapiro L, Kister I. Protean neurologic manifestations of two rare dermatologic disorders: sweet disease and localized craniofacial scleroderma. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2019;19(3):11. doi: 10.1007/s11910-019-0929-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maxwell G, Archibald N, Turnbull D. Neuro-sweet’s disease. Pract Neurol. 2012;12(2):126-130. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2011-000067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charlson R, Kister I, Kaminetzky D, Shvartsbeyn M, Meehan SA, Mikolaenko I. CNS neutrophilic vasculitis in neuro-sweet disease. Neurology. 2015;85(9):829-830. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh JS, Costello F, Nadeau J, Witt S, Trotter MJ, Goyal M. Case 176: Neuro-sweet syndrome. Radiology. 2011;261(3):989-993. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11092052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rujiwetpongstorn R, Chuamanochan M, Tovanabutra N, Chaiwarith R, Chiewchanvit S. Efficacy of acitretin in the treatment of reactive neutrophilic dermatoses in adult-onset immunodeficiency due to interferon-gamma autoantibody. J Dermatol. 2020;47(6):563-568. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pilkington T, Brogden RN. Acitretin: A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic use. Drugs. 1992;43(4):597-627. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199243040-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]