Abstract

Background

Intracranial dural arterio-venous fistulas are pathological anastomoses between arteries and veins located within dural sheets and whose clinical manifestations depend on location and hemodynamic features. They can sometimes display perimedullary venous drainage (Cognard type V fistulas—CVFs) and present as a progressive myelopathy. Our review aims at describing CVFs’ variety of clinical presentation, investigating a possible association between diagnostic delay and outcome and assessing whether there is a correlation between clinical and/or radiological signs and clinical outcomes.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search on Pubmed, looking for articles describing patients with CVFs complicated with myelopathy.

Results

A total of 72 articles for an overall of 100 patients were selected. The mean age was 56.20 ± 14.07, 72% of patients were man, and 58% received an initial misdiagnosis. CVFs showed a progressive onset in 65% of cases, beginning with motor symptoms in 79% of cases. As for the MRI, 81% presented spinal flow voids. The median time from symptoms’ onset to diagnosis was 5 months with longer delays for patients experiencing worse outcomes. Finally, 67.1% of patients showed poor outcomes while the remaining 32.9% obtained a partial-to-full recovery.

Conclusions

We confirmed CVFs’ broad clinical spectrum of presentation and found that the outcome is not associated with the severity of the clinical picture at onset, but it has a negative correlation with the length of diagnostic delay. We furthermore underlined the importance of cervico-dorsal perimedullary T1/T2 flow voids as a reliable MRI parameter to orient the diagnosis and distinguish CVFs from most of their mimics.

Keywords: Intracranial dural arterio-venous fistulas (iDAVFs), Intracranial vascular malformations, Myelopathy, Spinal cord disease

Introduction

Intracranial dural arterio-venous fistulas (iDAVFs) are rare malformations characterized by pathological anastomoses connecting arterial dural branches and dural sinuses, mostly the cavernous sinus and/or cortical veins. Arterial branches may arise from the external and internal carotid arteries and/or from the vertebrobasilar system. IDAVFs account for 10–15% of intracranial vascular malformations [1], representing about 6% of all supratentorial and 35% of all infratentorial vascular malformations [2]. They are generally acquired and associated with several predisposing factors such as history of craniotomy, head trauma, previous dural sinus infection or thrombosis, and genetic thrombosis predisposing mutations (heterozygous factor V Leiden and protein C/S deficiency) [1]. The mean age of diagnosis is between the fifth and the sixth decades, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.

Clinically, iDAVFs can present with both hemorrhagic and non-hemorrhagic symptoms, depending on the grade and anatomical localization. Hemorrhagic symptoms are typically characterized by lobar (or sublobar) hemorrhages, venous infarctions, and subdural hematomas; non-hemorrhagic symptoms are extremely variable, ranging from non-localizing signs such as intracranial hypertension with papilledema, headache, and nausea/vomiting to focal signs like seizures, cranial neuropathies, and pulsatile tinnitus. Chronic complications such as glaucoma, hydrocephalus, dementia, parkinsonism, and slowly progressive myelopathy are also possible [1].

IDAVFs are usually classified according to Borden-Shucart’s [3] or Cognard’s classifications [4], both strictly related to prognosis: the higher the grade, the worse the prognosis (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Cognard classification

| Cognard classification | Features |

|---|---|

| I | Drains into a dural sinus with anterograde flow |

| II | Drains with retrograde flow either into a sinus (IIA) or into cortical veins (IIB) |

| II A + B | Drains with retrograde flow into a sinus and into cortical veins |

| III | Drains into cortical veins without venous ectasia |

| IV | Drains into cortical veins with venous ectasia |

| V | Drains into spinal venous system |

Cognard type V fistulas (CVFs) display perimedullary venous drainage and are associated with myelopathy in 50% of cases [4, 5]. These entities are extremely rare; until 2016, only 54 cases of CVFs had been described [2]. In 2020 Hou et al. reported 73 patients with CVFs, 57 of which presented with either paraparesis or tetraparesis [6]. CVFs’ clinical presentation is highly variable, but the classical picture is that of a middle-aged man with ascending tetraparesis (62%), sphincter dysfunction (34%), bulbar symptoms (31%), and a sensory level typically developing over several months; nevertheless, up to 50% of cases can present with acute onset [7]. Small vessel thrombosis, infarct or hemorrhage, are believed to be responsible for rapid worsening or acute onsets [2].

The pathophysiology of myelopathy and brainstem engorgement is similar to that described for type I–IV fistulas, involving congestion and dilation of the venous system, but with the involvement of perimedullary veins instead of cortical veins [8]. However, as noted by Brunereau and colleagues, not all CVFs cause myelopathy [9]. Some authors speculate that in a subset of patients, a medullary-radicular vein connecting the spinal perimedullary venous network to the epidural venous system at the cervical level may prevent the establishment of spinal cord venous hypertension, while the absence of the communicating vein may predispose to engorgement of cervico-thoracic perimedullary veins, leading to medullary edema and rarely spinal infarct due to poor arterial supply [9]. Two other possible theories to explain spinal cord involvement in CVFs are arterial steal and direct compression of the spinal cord by enlarged veins, clot, or varicose vessels [2].

Due to their rarity, these entities are seldom suspected, resulting in a diagnostic delay up to many years (average time 220–343 days) [10]. Whether this delay affects patients’ life expectancy and the grade of residual disability is still a matter of debate. It is noteworthy that El Asri et al. postulated the absence of correlation between diagnostic delay and the clinical outcome in patients with paraparesis, quadriparesis, or bulbar dysfunction. They also found that 38% patients with CVFs died or did not improve significantly despite the treatment, whereas 26% of patients showed an improvement after the treatment but still had a moderate disability, highlighting that the outcome of CVFs can often be life changing. Nevertheless, treatment resulted in complete recovery or noticeable improvement (defined as persistence of only mild symptoms) in 36% of cases [10].

The objective of this article is to review the literature describing the clinical and radiological spectrum of CVF presentation, starting with a representative case, and to investigate whether there are any reliable clinical or radiologic parameters that could help clinicians in suspecting the diagnosis. The possibility of a misdiagnosis due to many “iDAVFs mimics” is another key point of our study; CVFs may cause clinical and radiological findings very similar to a variety of inflammatory, infectious, or vascular diseases (i.e., spinal dural fistulas) affecting the spinal cord. This virtual absence of pathognomonic signs makes the diagnosis extremely challenging and currently possible only in a few specialized centers.

Furthermore, we aim to assess whether specific clinical and radiological findings impact diagnostic delay and prognosis, and if there is a correlation between clinical and/or radiological signs and clinical outcomes.

A representative case

In December 2019, a 52-year-old man presented with subacute onset of severe neck pain, vertigo, nausea, and vomiting which completely resolved within a month. In April 2020, he reported progressive difficulty in walking with tripping, climbing stairs, and manipulating small objects. He sought medical attention on May 1st when he experienced acute urinary retention requiring hospitalization and catheterization. He denied any history of fever, insect bites, trauma, or recent vaccinations. His past medical history included hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, previous exposure to asbestos, and pulmonary fibrosis. There was no consanguinity between his parents, and family history was negative for neurological diseases. An urgent brain CT scan revealed a hypodense lesion in the right cerebellar hemisphere and subsequent MRI of the spine showed a gadolinium-enhancing spinal lesion suggestive of myelitis extending from the medulla to C7/D1. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis was inconclusive, and search for common pathogens in the CSF was negative. The patient was started on high doses of steroids with mild clinical improvement. At discharge, his neurological examination showed left gaze evoked nystagmus, mild central left facial paresis, hyperreflexic quadriparesis with ankle clonus, abolished pain, and temperature and proprioception below D10 along with urinary and bowel incontinence. Despite initial improvement, the patient relapsed in August 2020 with worsening in his upper limb strength, increased lower limb spasticity, and altered mentation. MRI revealed extension of the previously described lesion to the pons (see Fig. 1). CFS analysis was once again uninformative and the extensive search even for tropical microorganisms was inconclusive. Vasculitides, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders, and other autoimmune systemic diseases were ruled out. A total-body PET study with 18-FDG did not show any findings consistent with neoplasm, and no malignant cells were found in the CSF. After a multidisciplinary discussion, neuroradiologists carefully reviewed the spinal MRI and identified the presence of tortuous vessels behind the cervical spinal cord. Subsequent cerebral angiography (digital subtraction angiography, DSA) confirmed the presence of an arterio-venous fistula between the posterior meningeal artery and the straight sinus with drainage into the perimedullary venous plexus at cervical level (Cognard type V fistula, see Fig. 2). The patient underwent endovascular treatment, which resulted in almost complete obliteration of the fistula; he was discharged to a rehabilitation center 2 weeks later. One year after the embolization, the patient’s neurological examination remained unchanged and he continued to use a wheelchair. In October 2021, he underwent successful retreatment with the endovascular approach, resulting in complete obliteration of the fistula, with only slight improvement in upper limb strength noted after the procedure.

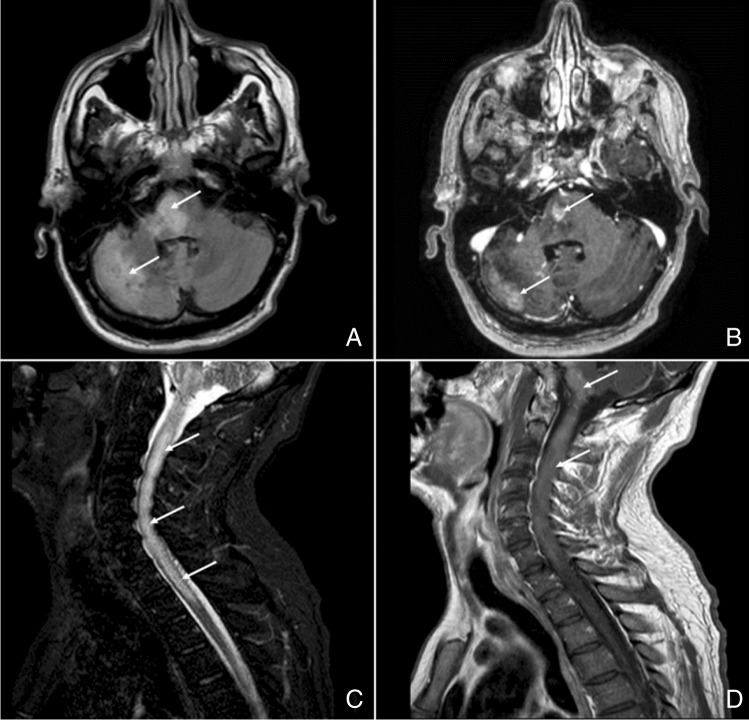

Fig. 1.

MRI at the diagnosis. A Axial FLAIR sequence shows hyperintensities in the pons and in the right cerebellar hemisphere (white arrows). B Axial T1-weight image obtained after gadolinium administration reveals enhancement of the same areas (white arrows). C Sagittal T2-weighted image shows intramedullary hyperintensity from the medulla oblongata to D2 vertebra level, with swollen cervical spinal cord (white arrows). D Gd-enhancement of the lesion shown in C (white arrows)

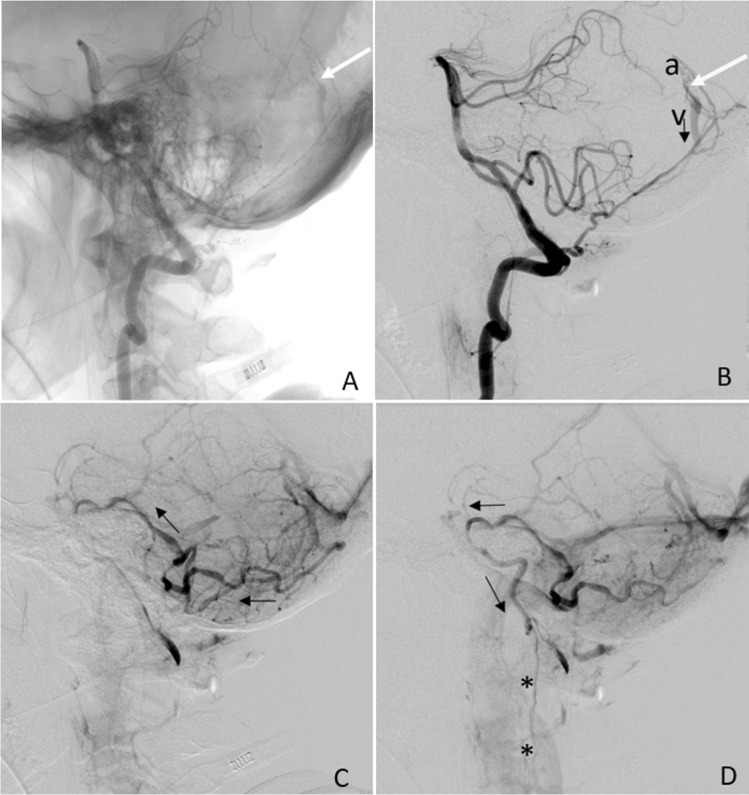

Fig. 2.

Cerebral angiography, vertebral artery injections. A The A-V shunt at the fistula site is indicated by the white arrow (LL view). The arterial feeder is the posterior meningeal artery (PMA), arising from the vertebral artery. B Same as in (A) but with digitally subtracted images showing the feeding artery (PMA, a), the fistula site (white arrow), and the precociously enhanced straight sinus (v). Retrograde venous drainage route is indicated by the black arrow. C Parenchimal-phase acquired image showing backward venous drainage route (black arrows) toward the perimedullary venous system. D Late acquisition image showing venous blood direction (black arrows) reaching the perimedullary venous system at cervical level (*)

Materials and methods

Literature search

We started identifying the published case reports and case series of patients having CVFs using a search strategy developed by three authors (ADG, ES, and CM) through an iterative process. We searched for published articles that mentioned iDAVF in title, abstract, and keywords using the following strategy: “Intracranial fistula AND spinal drainage,” “Intracranial fistula AND spinal cord,” “Intracranial fistula AND myelopathy,” and “Intracranial fistula AND myelitis,” since the inception of the database to March 2021. The language was restricted to English and Italian. The search was conducted independently by three experienced neurologists (ADG, ES, and CM) and was performed both (a) in PubMed electronic database and (b) through manual searches (i.e., reference lists of previously reported case reports/series and systematic reviews on this topic identified during the search).

Study selection and data extraction

Following the procedure detailed by El Asri and colleagues and by Kamio et al. [10, 11], we collected all case reports published from inception to March 2021, thus providing a greater sample size of patients with CVF. We included all articles which (a) described a case or a series of cases of CVFs and that (b) were written in English or Italian. We excluded (1) articles in which full text could not be obtained; (2) papers concerning the pediatric populations; (3) unrelated papers (i.e., spinal fistulas).

The screening process was conducted as follows: first, the three authors (ADG, ES, and CM) independently reviewed all abstracts and titles for eligibility: after a manual screening, full-text reports were obtained if a study was deemed eligible or where eligibility was unclear. Then, reports were finally examined for inclusion, with disagreement resolved through consensus by the three authors.

Regarding the data extraction, we adopted a standardized coding scheme to collect data referring to (1) age and sex of patients, (2) type of CVF onset (acute, progressive, or multiphasic; see below), (3) presence of predisposing factors, (4) symptoms at onset (motor, sensory, sphincteric disturbances, ataxia, brainstem symptoms, dizziness/nausea/vomiting, and others), (5) symptoms at diagnosis, (6) time interval to definite diagnosis, (7) presence of an initial misdiagnosis, (8) MRI findings at diagnosis, (9) CVF localization, (10) feeding artery, (11) type of treatment (surgery or endovascular), (12) outcome (outlined as good recovery/complete regression, moderate disability, severe disability/death), (13) presence of a relapse, (14) length of post-treatment follow-up, and (15) angiography outcome. The authors coded all available information reported in any part of the articles, including tables and figures. Under “brainstem signs” we included the following: dysphagia, dysphonia, dysarthria, respiratory failure, diplopia, gaze-evoked nystagmus, decreased gag reflex, cranial nerves palsies, and hiccups. “Acute” onset was defined as an abrupt onset over 1 day or two, “multiphasic” onset was defined as bouts of symptoms with complete or almost complete recovery between the episodes, and “progressive” onset was preferred when disturbs developed over time with no definite poussées. For clinical outcome assessment, we defined “good recovery” (GR) as the complete regression of symptoms, “moderate disability” (MD) either as the ability to walk with assistance or neurologic sequalae interfering with daily activities but not determining loss of independence, and “severe disability (SD)/death” either as the inability to walk or as neurologic sequelae severely interfering with daily activities or as death. Missing data were not imputed.

Statistical analysis

Data extracted from case series or case reports were then analyzed through descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages.

Further, we tested several hypotheses on the association between socio-demographic, clinical, and neurological variables, and CVF (i) type of onset (acute, progressive, or multiphasic), (ii) outcomes (dichotomized as good outcome vs disability/death), (iii) time interval to diagnosis, and (iv) presence of specific symptoms at onset, through univariate and multivariate statistics. Differences between frequencies of specific categories were tested through chi square tests (with the significantly different categories identified through the adjusted standardized residuals >|2| [12]. Further, non-parametric correlations, Mann–Whitney U tests and Kruskal–Wallis ANOVAs were adopted to test for the association between dichotomous and continuous variables and for the presence of significant differences between groups on continuous independent variables, respectively.

All analyses were performed with SPSS 26 (IBM, 2019). All statistical tests were two tailed, and a p ≤ 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

Literature search and study inclusion

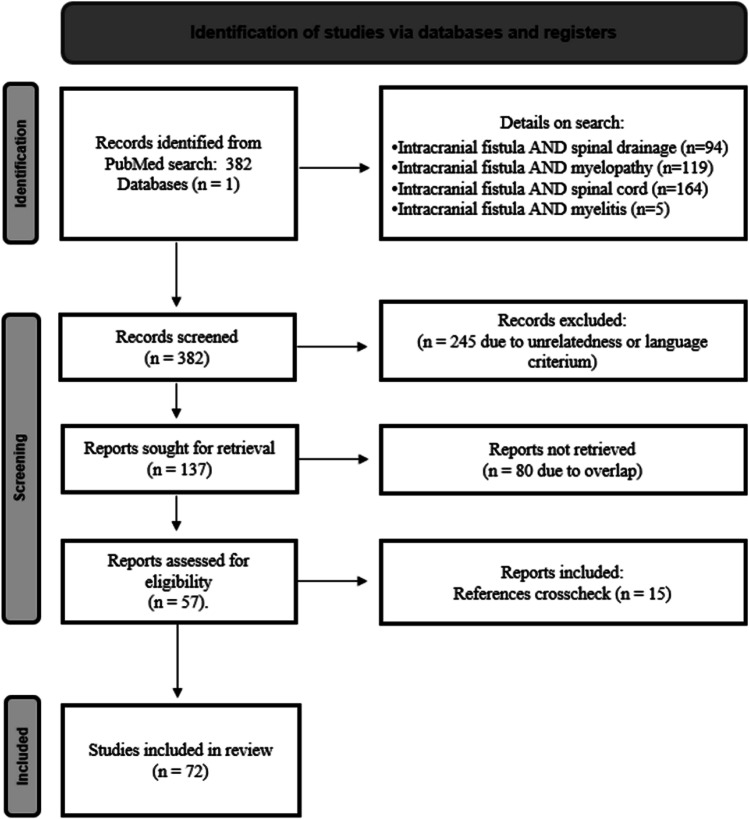

The literature search initially yielded 382 articles. After screening titles and abstracts, 245 articles were excluded due to unrelatedness or because they were written in languages other than Italian or English. Additionally, 80 duplicates were removed, and 16 records were identified through other sources such as manual searches among reference lists of previously published reviews. The PRISMA flow diagram, depicted in Fig. 3, provides a graphical representation of the screening process. In total, 72 studies, including 60 case reports and 12 case series, were included in the analysis, providing data on a total of 100 patients with CVF. The median year of publication for the 72 studies was 2006, with a range from 1988 to 2020.

Fig. 3.

Flow chart of the searching strategy

Socio-demographic, clinical, and radiological features

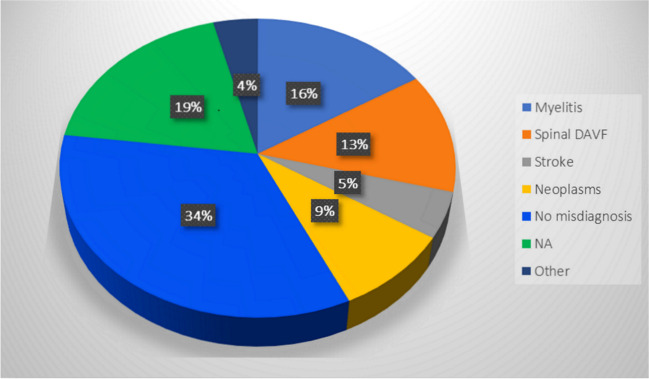

Table 2 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the patients with CVF. Most of the patients were middle aged, with a mean age of 56.20 ± 14.07 years and a range of 18–79 years and the majority were males (72%, N = 72). Predisposing factors, such as past head trauma, were reported in only 20.4% of the articles. The CVF’s onset was mostly progressive (N = 63, 64.9%), while multiphasic (N = 21, 21.6%) and acute (N = 13, 13.4%) onsets were less commonly reported. A total of 47 patients (58%) received an initial misdiagnosis. More details are provided in Fig. 4.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients with DAVF (N = 100)

| Author | Year | Age | Sex | Onset | Predisposing factors | Interval to definite diagnosis | Initial misdiagnosis | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelsadg et al.[2] | 2016 | 65 | F | Acute | No | 0 months | No | GR |

| Abud et al.[23] | 2015 | 66 | F | Progressive | NA | 1 month | No | GR |

| Aixut et al.[24] | 2011 | 67 | F | Multiphasic | NA | 0 months | No | NA |

| Akkoc et al.[13] | 2006 | 45 | M | Progressive | NA | 2 months | Stroke, transverse myelitis | SD |

| Asakawa et al.[25] | 2002 | 64 | M | Multiphasic | No | 0.5 months | No | SD |

| Bernard et al.[17] | 2018 | 65 | F | Progressive | No | 5 months | Neoplasm (glioma) | GR |

| Bousson et al.[26] | 1999 | 36 | M | Multiphasic | No | 12 months | No | MD |

| Bret et al.[15] | 1994 | 31 | M | Multiphasic | No | 4 months | Transverse myelitis | MD |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (1) | 1996 | 35 | F | Progressive | NA | NA | Spinal dural A-V fistula | NA |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (2) | 1996 | 37 | M | Progressive | NA | NA | Spinal dural A-V fistula | NA |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (3) | 1996 | 53 | M | Progressive | NA | NA | Spinal dural A-V fistula | NA |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (4) | 1996 | 69 | M | Progressive | NA | NA | Spinal dural A-V fistula | NA |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (5) | 1996 | 68 | F | Progressive | NA | NA | Spinal dural A-V fistula | NA |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (6) | 1996 | 69 | M | Progressive | NA | NA | Spinal dural A-V fistula | NA |

| Chen CJ et al.[27] (1) | 1998 | 36 | F | Progressive | NA | 1 month | No | SD |

| Chen CJ et al.[27] (2) | 1998 | 47 | M | Progressive | Occipital skull fracture 2 years before | 12 months | No | SD |

| Chen PM et al.[28] | 2018 | 25 | F | Acute | Occipital trauma 1 month prior | NA | Brainstem encephalitis, myelitis | NA |

| Chen PY et al.[29] | 2019 | 66 | M | Multiphasic | NA | 1 month | Neoplasm | GR |

| Chng et al.[30] | 2004 | 67 | M | Acute | NA | 0 months | No | MD |

| Clayton et al.[31] | 2020 | 32 | M | Progressive | No | 1 month | Myelitis, GBS | MD |

| Copelan et al.[20] (1) | 2018 | 59 | M | Multiphasic | NA | 1.25 months | Neoplasm | GR |

| Copelan et al.[20] (2) | 2018 | 72 | M | Progressive | Previous neurosurgery | 3 months | NA | NA |

| Copelan et al.[20] (3) | 2018 | 35 | F | Progressive | Previous pilocytic astrocytoma | 1 month | No | GR |

| Copelan et al.[20] (4) | 2018 | 64 | F | Progressive | NA | 6 months | Transverse myelitis | SD |

| Deopujari et al.[32] | 1995 | 50 | F | Progressive | Intracranial hypertension/pseudotumor cerebri | 6 months | No | GR |

| El Asri et al.[10] | 2013 | 48 | M | Acute | No history of trauma | 0.3 months | Spinal dural A-V fistula | SD |

| Enokizono et al.[22] (1) | 2017 | 60 | M | Multiphasic | NA | 7 months | NA | NA |

| Enokizono et al.[22](2) | 2017 | 60 | M | Progressive | NA | 2 months | Transverse myelitis, Demyelinating lesion | NA |

| Ernst et al.[33] (1) | 1997 | 71 | M | Progressive | No | NA | No | MD |

| Ernst et al.[33] (2) | 1997 | 47 | M | Progressive | No | 5 months | No | MD |

| Ernst et al.[33] (3) | 1997 | 58 | F | Progressive | No | NA | No | SD |

| Foreman et al.[34] | 2013 | 59 | M | Multiphasic | Muscular effort a few days before symptoms’ onset (moving boxes in his home); chiropractic manipulation the day of onset | 0.75 months | Spinal cord trauma | SD |

| Gaensler et al.[35] | 1989 | 50 | M | Multiphasic | NA | 48 months | NA | MD |

| Gobin et al.[36] (1) | 1992 | 35 | F | Progressive | NA | 6 months | NA | GR |

| Gobin et al.[36] (2) | 1992 | 37 | M | Multiphasic | NA | 9 months | NA | SD |

| Gobin et al.[36] (3) | 1992 | 53 | M | Progressive | Laminectomy | 5 months | Cervical stenosis with spinal cord compression | SD |

| Gobin et al.[36] (4) | 1992 | 69 | M | Multiphasic | NA | 12 months | NA | GR |

| Gobin et al.[36] (5) | 1992 | 68 | F | Progressive | NA | 4 months | NA | MD |

| Gross et al.[37] (1) | 2014 | 69 | M | Acute | NA | 5 days | GBS | GR |

| Gross et al.[37] (2) | 2014 | 34 | F | Progressive | Whole brain irradiation | 0.25 months | Transverse myelitis | GR |

| Hähnel et al.[38] | 1998 | 67 | M | Progressive | No | 6 months | No | GR |

| Haryu et al.[39] | 2014 | 62 | M | Progressive | No | 4 months | Demyelinating lesion | MD |

| Iwase et al.[40] | 2020 | 76 | M | Acute | No | 1 month | NMOSD | MD |

| Joseph et al.[41] | 2000 | 42 | M | Multiphasic | NA | 24 months | Spinal cord infarction | MD |

| Jun Li et al.[18] | 2004 | 73 | M | Multiphasic | No | 12 months | Stroke (twice) | MD |

| Kalamangalam et al.[21] | 2002 | 68 | M | Acute | No | 4 months | Stroke | MD |

| Kamio et al.[11] | 2015 | 66 | F | Progressive | NA | 8 months | Spinal dural A-V fistula | GR |

| Khan et al.[42] | 2009 | 20 | F | Acute | NA | 0.5 months | Meningoencephalitis, NMOSD, sarcoidosis, Transverse myelitis | SD |

| Kim HJ et al.[43] | 2015 | 61 | M | Progressive | No | 18 months | Myelitis, Neoplasm | SD |

| Kim NH et al.[44] | 2011 | 45 | M | Progressive | No | 6 months | Demyelinating lesion | MD |

| Kim WY et al.[45] | 2016 | 60 | M | Progressive | NA | No delay (0 months) | Spinal dural A-V fistula | GR |

| Kleeberg et al.[46] | 2010 | 60 | M | Progressive | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kulwin et al.[47] | 2012 | 44 | F | Acute | No | NA | Stroke | SD |

| Kvint et al.[48] | 2020 | 48 | M | Multiphasic | No | 6 months | Neoplasm | GR |

| Lagares et al.[49] | 2007 | 65 | M | Multiphasic | NA | 3 months | Stroke | GR |

| Lv et al.[50] | 2011 | 18 | M | Progressive | NA | NA | NA | MD |

| Mascalchi et al. [51] (1) | 1996 | 69 | M | Progressive | Head trauma at age 25 | 48 months | No | NA |

| Mascalchi et al.[51] (2) | 1996 | 53 | M | Progressive | No | 24 months | No | NA |

| Narita et al.[52] | 1992 | 45 | F | Acute | Previous treatment of CCF | 0 months | No | GR |

| Ogbonnaya et al.[53] | 2011 | 64 | F | Progressive | No | 3 months | No | NA |

| Pannu et al.[54] | 2004 | 42 | M | Progressive | No | 12 months | No | MD |

| Partington et al.[55] (1) | 1992 | 63 | M | Progressive | NA | 4 months | NA | GR |

| Partington et al.[55] (2) | 1992 | 74 | M | NA | NA | 6 months | NA | SD |

| Patsalides et al.[16] | 2010 | 53 | M | Progressive | NA | NA | Neoplasm (lymphoma), encephalitis, demyelinating lesion | GR |

| Peethambar et al.[16] | 2018 | 64 | M | Progressive | No | 1.5 months | Transverse myelitis | MD |

| Peltier et al.[56] | 2011 | 58 | F | Multiphasic | NA | 2 months | NA | MD |

| Perkash et al.[57] | 2002 | 79 | M | Progressive | No | 8 months | No | SD |

| Pop et al.[58] | 2015 | 38 | M | Multiphasic | No | 2 months | Myelitis, GBS | MD |

| Renner et al.[59] | 2006 | 58 | M | Progressive | NA | NA | Spinal dural A-V fistula | GR |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (1) | 1998 | 69 | M | Progressive | NA | 36 months | No | SD |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (2) | 1998 | 53 | M | Acute | NA | NA | No | MD |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (3) | 1998 | 40 | F | Multiphasic | NA | 0 months | No | SD |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (4) | 1998 | 75 | F | Multiphasic | NA | NA | Transverse myelitis | GR |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (5) | 1998 | 51 | F | NA | NA | 5 months | Subarachnoid hemorrhage | GR |

| Rocca et al.[61] | 2019 | 67 | M | Progressive | NA | 7 months |

Transverse myelitis, neoplasm, spinal dural A-V fistula, TB, vasculitis, paraneoplastic syndrome, NMOSD, Lyme disease |

SD |

| Rodriguez Rubio et al.[62] | 2019 | 68 | M | Acute | NA | NA | NA | MD |

| Roelz et al.[63] | 2015 | 76 | M | Multiphasic | No | 8 months | Neoplasm, Demyelinating lesion | MD |

| Satoh et al.[64] | 2005 | 38 | F | Acute | No | 0 months | Stroke | MD |

| Shimizu et al.[65] | 2019 | 75 | M | Progressive | No | 6 months | No | MD |

| Singh et al.[66] | 2013 | NA | M | NA | No | 5 months | Periodic paralysis, myelitis | GR |

| Sorenson et al.[67] | 2019 | 57 | M | Progressive | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Sugiura et al.[68] | 2009 | 69 | F | Multiphasic | No | 2 months | No | MD |

| Sun et al.[69] | 2019 | 50 | M | Progressive | NA | 5 months | NA | GR |

| Tanaka et al.[70] | 2017 | 64 | M | Progressive | No | NA | No | MD |

| Tanoue et al.[71] | 2005 | 70 | M | Progressive | No | 24 months | No | MD |

| Trop et al.[72] | 1998 | 74 | M | Progressive | No | 12 months | No | MD |

| Tsutsumi et al.[73] | 2008 | 62 | F | Progressive | No | 12 months | Neoplasm, myelitis | MD |

| Van Rooij et al.[74] (1) | 2007 | 58 | M | Progressive | NA | 3 months | NA | GR |

| Van Rooij et al.[74] (2) | 2007 | 65 | M | Progressive | NA | 12 months | NA | SD |

| Van Rooij et al.[74] (3) | 2007 | 72 | F | Progressive | NA | 24 months | NA | SD |

| Versari et al.[75] (1) | 1993 | 50 | M | Progressive | No | 7 months | No | MD |

| Versari et al.[75] (2) | 1993 | 71 | M | Progressive | No | 9 months | No | GR |

| Wang et al.[76] | 2019 | 57 | M | Progressive | NA | 3 months | No | GR |

| Wiesmann et al.[14] | 2000 | 46 | M | Multiphasic | NA | 0.1 months | No | GR |

| Willinsky et al.[77] | 1990 | 57 | M | Progressive | No | 36 months | No | SD |

| Wrobel et al.[78] (1) | 1988 | 43 | M | Progressive | NA | 36 months | NA | MD |

| Wrobel et al.[78] (2) | 1988 | 68 | M | Progressive | NA | 6 months | Spinal dural A-V fistula | SD |

| Wrobel et al.[78] (3) | 1988 | 42 | M | Progressive | NA | NA | Multiple sclerosis, Spinal dural A-V fistula, transverse myelitis | SD |

| Yoshida et al.[79] | 1999 | 68 | M | Progressive | No | 6 months | No | MD |

| Zhang et al.[80] | 2018 | 33 | M | Progressive | No | 2 months | Transverse myelitis | MD |

NA, not available; CCF, carotid-cavernous fistula; GBS, Guillain-Barrè syndrome; GR, good recovery/complete remission; MD, moderate Disability; NMOSD, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders; SD, severe disability or death; TB, tuberculosis

Fig. 4.

Misdiagnosis rate. Note. NA, not available

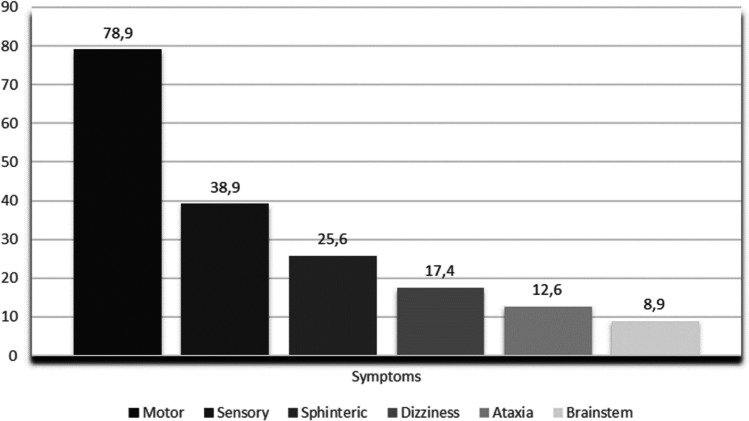

The median time from symptoms onset to diagnosis was 5 months (range: 0–48 months). Figure 5 provides a graphical depiction of the prevalence of symptoms at onset.

Fig. 5.

Symptoms at onset

MRI findings at diagnosis included flow voids (81.6%, N = 71), T2 hyperintensities (80.5%, N = 70), and swelling (56.3%, N = 49). DWI abnormalities, thrombosis, and T2* effects were rare (2 cases each, 2.3%), and contrast enhancement assessment was performed in only 55.8% of cases (N = 29).

As for clinical outcomes after treatment, 57 patients experienced a moderate-to-severe disability or died (N = 57; 67.1%; moderate disability, N = 33, 41.3%; severe disability/death = 19, 23.8%), while 28 experienced a partial-to-full recovery (32.9%).

Patients underwent endovascular treatment (N = 45, 48.9%), open surgery (N = 28, 30.4%), or both (N = 20, 21.3%); a total of 10 patients experienced a relapse after the first treatment attempt (11.9%).

Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 report all the clinical and radiological variables hitherto described.

Table 3.

Additional clinical and neurological characteristics of patients with DAVF (N = 100)

| Author | Year | DAVF localization | Feeding artery | Treatment | Relapse | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelsadg et al.[2] | 2016 | Left petrosal sinus | MHT, MMA | Endovascular | No | 3 months |

| Abud et al.[23] | 2015 | Right sigmoid sinus | Right OA | Endovascular | No | 3 months |

| Aixut et al.[24] | 2011 | Upper margin of the right petrosal bone | APhA | Endovascular | No | 9 months |

| Akkoc et al.[13] | 2006 | Posterior fossa | Left OA, APhA | Endovascular (twice) | Yes | 6 months |

| Asakawa et al.[25] | 2002 | CCJ | Left APhA | Endovascular + surgery | No | 3 months |

| Bernard et al.[17] | 2018 | Right Jugular Foramen | Right APhA | Surgery | No | 1 month |

| Bousson et al.[26] | 1999 | Tentorium cerebelli | Left OA | Endovascular | No | 0,5 months |

| Bret et al.[15] | 1994 | Tentorium cerebelli | ICA (siphon) | Surgery | No | 5 months |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (1) | 1996 | Left transverse sinus | Left MMA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (2) | 1996 | Left petrosal sinus | Left MMA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (3) | 1996 | Tentorium cerebelli | Left MHT | Surgery | NA | NA |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (4) | 1996 | Left petrosal sinus | Left APhA, left OA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (5) | 1996 | Left petrosal sinus | Left APA, left MMA, left OA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (6) | 1996 | Tentorium cerebelli | Left MHT | NA | NA | NA |

| Chen CJ et al.[27] (1) | 1998 | Torcular region | Left MMA, left VA | Surgery | No | 3 months |

| Chen CJ et al.[27] (2) | 1998 | Torcular region | Left VA | Surgery | No | 2 months |

| Chen PM et al.[28] | 2018 | Posterior fossa | Right VA | Endovascular | No | After the embolization |

| Chen PY et al.[29] | 2019 | NA | Right OA, right distal VA | Endovascular | No | 3 months |

| Chng et al.[30] | 2004 | CCJ | Right APhA | Endovascular | No | 2 days |

| Clayton et al.[31] | 2020 | Petrous apex | Cavernous ICA | Endovascular + surgery | Yes | 48 months |

| Copelan et al.[20] (1) | 2018 | Left superior petrosal sinus | OA, APhA, MMA | Endovascular + surgery | No | 36 months |

| Copelan et al.[20] (2) | 2018 | Anterior condilar vein | Right APhA | Endovascular | No | 5 months |

| Copelan et al.[20] (3) | 2018 | Superior petrosal sinus | OA | Endovascular | No | 3 months |

| Copelan et al.[20] (4) | 2018 | Superior petrosal sinus | IFLT | Endovascular + surgery | Yes | 12 months |

| Deopujari et al.[32] | 1995 | Overlying the right cerebellar hemisphere | MMA, OA | Endovascular + surgery | No | 1 month |

| El Asri et al.[10] | 2013 | Left tentorial (posterior fossa) | Tentorial artery of Bernasconi and Cassinari | Surgery | No | 2 months |

| Enokizono et al.[22] (1) | 2017 | Tentorium cerebelli | Right MHT, MMA and AMA | Surgery | No | NA |

| Enokizono et al.[22](2) | 2017 | Tentorium cerebelli | MMA | Endovascular + surgery | No | NA |

| Ernst et al.[33] (1) | 1997 | Superior Petrosal sinus | NA | Surgery | No | 18 months |

| Ernst et al.[33] (2) | 1997 | Occipital condyle | Right APhA | Endovascular | No | 48 months |

| Ernst et al.[33] (3) | 1997 | Skull Base | Ascending cervical, vertebral, ophthalmic | Endovascular | Yes | 48 months |

| Foreman et al.[34] | 2013 | CCJ | MHT | Surgery | No | NA |

| Gaensler et al.[35] | 1989 | Anterior foramen magnum | VA and APhA | Endovascular | No | 24 months |

| Gobin et al.[36] (1) | 1992 | Left lateral sinus | MMA and OA | Endovascular | No | 6 months |

| Gobin et al.[36] (2) | 1992 | Left petrous apex | MMA | Endovascular + surgery | NV | No follow-up (death) |

| Gobin et al.[36] (3) | 1992 | Left tentorium cerebelli | MHT | Endovascular | No | 6 months |

| Gobin et al.[36] (4) | 1992 | Left superior petrous sinus | APhA and OA | Endovascular + surgery | No | 12 months |

| Gobin et al.[36] (5) | 1992 | Left superior petrous sinus | Left MMA, APhA, OA | Endovascular | No | 8 months |

| Gross et al.[37] (1) | 2014 | Posterior fossa | Left MMA, left ICA, OA and PA | Endovascular | No | 2,5 months |

| Gross et al.[37] (2) | 2014 | Left transverse sigmoid junction | Left OA | Endovascular | No | 3 months |

| Hähnel et al.[38] | 1998 | NA | APhA, OA | Endovascular | No | 2.5 months |

| Haryu et al.[39] | 2014 | Tentorium cerebelli | MMA | Surgery | No | NA |

| Iwase et al.[40] | 2020 | NA | OA | Endovascular + surgery | No | 2 months |

| Joseph et al.[41] | 2000 | NA | Left MMA, PMA, and both OA | Endovascular | No | 2 months |

| Jun Li et al.[18] | 2004 | Left transverse sinus | Left MMA, OA, right APhA | Endovascular | No | 5 days |

| Kalamangalam et al.[21] | 2002 | Clivus | ICA | Surgery | No | 4 months |

| Kamio et al.[11] | 2015 | Left transverse-sigmoid sinus | Left OA, MMA | Endovascular | No | 3 months |

| Khan et al.[42] | 2009 | Left tentorium cerebelli | Tentorial artery of Bernasconi and Cassinari | Surgery | No | 3 months |

| Kim HJ et al.[43] | 2015 | Petrous ridge | MMA | Endovascular | No | 6 months |

| Kim NH et al.[44] | 2011 | Left petrous region | ICA | Surgery | No | 1 month |

| Kim WY et al.[45] | 2016 | Posterior fossa (prepontine vein) | MHT, artery of foramen rotundum, right MMA | Endovascular | No | 12 months |

| Kleeberg et al.[46] | 2010 | Tentorium cerebelli | Tentorial artery of Bernasconi and Cassinari | Endovascular + surgery | NA | NA |

| Kulwin et al.[47] | 2012 | Superior Petrosal sinus | MMA, VA | Surgery | No | NA |

| Kvint et al.[48] | 2020 | Tentorium cerebelli | SCA | Surgery | No | 3 months |

| Lagares et al.[49] | 2007 | Torcular Herophilii | NA | Surgery | No | 6 months |

| Lv et al.[50] | 2011 | Tentorium cerebelli | Left MHT, MMA | Endovascular | No | 5 months |

| Mascalchi et al. [51] (1) | 1996 | Skull base | APhA, VA | Surgery | NA | NA |

| Mascalchi et al.[51] (2) | 1996 | Condylar channel | APhA | Endovascular | NA | NA |

| Narita et al.[52] | 1992 | CCF | VA, ICA | Surgery | No* | 2 months |

| Ogbonnaya et al.[53] | 2011 | NA | NA | Endovascular | NA | NA |

| Pannu et al.[54] | 2004 | Right tentorium cerebelli | Cavernous segment of ICA | Endovascular + surgery | No | 12 months |

| Partington et al.[55] (1) | 1992 | Left foramen magnum | PMA | Surgery | No | 9 months |

| Partington et al.[55] (2) | 1992 | Right foramen magnum | PMA | None (died) | NA | NA |

| Patsalides et al.[16] | 2010 | Superior petrosal sinus | MHT, MMA | Endovascular | No | 9 months |

| Peethambar et al.[16] | 2018 | Left tentorium cerebelli | Tentorial artery of Bernasconi and Cassinari | Endovascular + surgery | No | 3 months |

| Peltier et al.[56] | 2011 | CCJ | Left VA | Endovascular + surgery | No | 6 months |

| Perkash et al.[57] | 2002 | Petrous apex | VA, APhA, PA | None (refused) | NA | NA |

| Pop et al.[58] | 2015 | Foramen magnum | OA, APhA | Endovascular | Yes | 6 months |

| Renner et al.[59] | 2006 | Tentorium cerebelli | Right MHT | Surgery | No | 3 months |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (1) | 1998 | Tentorium cerebelli | Artery of foramen rotundum, C5 ICA | Endovascular | NA | NA |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (2) | 1998 | Tentorium cerebelli | MMA and C5 ICA | Endovascular + surgery | Yes | 24 months |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (3) | 1998 | Right cavernous sinus | ICA and ECA | Endovascular twice | Yes | NA |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (4) | 1998 | Left superior petrosal sinus | Left MMA, OA, right APhA | Endovascular | No | 60 months |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (5) | 1998 | Right sigmoid sinus | Right OA, MMA | Endovascular | No | 12 months |

| Rocca et al.[61] | 2019 | Right lateral region of foramen magnum | APhA | Surgery | No | NA |

| Rodriguez Rubio et al.[62] | 2019 | Tentorium cerebelli | Right PMA | Endovascular + surgery | NA | No follow-up |

| Roelz et al.[63] | 2015 | Petrous ridge | MMA, APhA, OA | Endovascular + surgery | Yes | 6 months after first treatment and 0.5 months after the 2nd one |

| Satoh et al.[64] | 2005 | Left tranverse-sigmoid sinus | Right MMA, OA, APhA, VA, Left MHT | Endovascular | No | 1 month |

| Shimizu et al.[65] | 2019 | Anterior cranial fossa | Anterior ethmoidal artery | Surgery | No | 2 months |

| Singh et al.[66] | 2013 | Left tentorium cerebelli | MMA, ICA | Endovascular + surgery | No | NA |

| Sorenson et al.[67] | 2019 | CCJ | PICA | Endovascular + surgery | Yes | NA |

| Sugiura et al.[68] | 2009 | Sigmoid sinus and superior petrosal sinus | OA | Endovascular | No | 0.75 months |

| Sun et al.[69] | 2019 | Foramen magnum | Left VA | Surgery | No | 0.3 months |

| Tanaka et al.[70] | 2017 | Occipital sinus | PMA | Endovascular | No | 8 months |

| Tanoue et al.[71] | 2005 | Anterior condylar vein | APhA, OA | Endovascular | No | 12 months |

| Trop et al.[72] | 1998 | Foramen magnum | VA | Surgery | No | NA |

| Tsutsumi et al.[73] | 2008 | Petrosal and cavernous sinus | APhA and OA | Endovascular | No | NA |

| Van Rooij et al.[74] (1) | 2007 | Tentorium cerebelli | APhA, MMA | Endovascular | No | 12 months |

| Van Rooij et al.[74] (2) | 2007 | Petrous ridge | Stylomastoid artery | Endovascular + surgery | No | 12 months |

| Van Rooij et al.[74] (3) | 2007 | Marginal sinus of the foramen magnum | OA | Endovascular | No | 24 months |

| Versari et al.[75] (1) | 1993 | Superior Petrosal sinus | MHT | Surgery | No | 24 months |

| Versari et al.[75] (2) | 1993 | Sigmoid sinus | OA, MMA | Endovascular + surgery | No | 6 months |

| Wang et al.[76] | 2019 | Dorsal sellae | Right MHT, ophthalmic artery, MMA | Endovascular | Yes | 24 months |

| Wiesmann et al.[14] | 2000 | Anteromedian pontine vein | Left APhA | Endovascular | No | 12 months |

| Willinsky et al.[77] | 1990 | Foramen magnum | APhA | Endovascular | No | 18 months |

| Wrobel et al.[78] (1) | 1988 | Right petrous apex | OA, ICA | Endovascular | No | 9 months |

| Wrobel et al.[78] (2) | 1988 | Petrous apex | OA, ICA | Surgery | No | 3 months |

| Wrobel et al.[78] (3) | 1988 | Tentorium cerebelli | MHT, OA, APhA | Surgery | No | 3 months |

| Yoshida et al.[79] | 1999 | CCJ | VA | Surgery | No | NA |

| Zhang et al.[80] | 2018 | NA | MHT | Endovascular | No | 1 month |

NA, not available; APhA, ascending pharyngeal artery; CCJ, cranio-cervical junction; CCF, carotid-cavernous fistula; ECA, external carotid artery; ICA, internal carotid artery; IFLT, inferolateral trunk; MHT, meningohypophyseal trunk; MMA, middle meningeal artery; OA, occipital artery; PA, posterior auricular; PICA, posterior inferior cerebellar artery; PMA, posterior meningeal artery; SCA, superior cerebellar artery; VA, vertebral artery

*This episode itself is a relapse

Table 4.

Symptoms at onset among patients with DAVF (N = 100)

| Author | Year | Motor | Sensory | Sphincteric disturbance | Ataxia | Brainstem symptoms | Dizziness, nausea, vomiting | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelsadg et al.[2] | 2016 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Vertigo |

| Abud et al.[23] | 2015 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Aixut et al.[24] | 2011 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Acute neck pain |

| Akkoc et al.[13] | 2006 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Occipital headache |

| Asakawa et al.[25] | 2002 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Bernard et al.[17] | 2018 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Bousson et al.[26] | 1999 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Bret et al.[15] | 1994 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (1) | 1996 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (2) | 1996 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (3) | 1996 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (4) | 1996 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (5) | 1996 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (6) | 1996 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Chen CJ et al.[27] (1) | 1998 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Chen CJ et al.[27] (2) | 1998 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Chen PM et al.[28] | 2018 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Chen PY et al.[29] | 2019 | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Vertigo |

| Chng et al.[30] | 2004 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Clayton et al.[31] | 2020 | Yes | No | Yes | NA | No | No | No |

| Copelan et al.[20] (1) | 2018 | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Vertigo |

| Copelan et al.[20] (2) | 2018 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Copelan et al.[20] (3) | 2018 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Copelan et al.[20] (4) | 2018 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Deopujari et al.[32] | 1995 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | NA | No | No |

| El Asri et al.[10] | 2013 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Enokizono et al.[22] (1) | 2017 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Enokizono et al.[22](2) | 2017 | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | No | No |

| Ernst et al.[33] (1) | 1997 | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Ernst et al.[33] (2) | 1997 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ernst et al.[33] (3) | 1997 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Foreman et al.[34] | 2013 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Cervical and lumbar pain |

| Gaensler et al.[35] | 1989 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Gobin et al.[36] (1) | 1992 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Headache, ear bruit |

| Gobin et al.[36] (2) | 1992 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Gobin et al.[36] (3) | 1992 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Lumbar and upper extremities pain |

| Gobin et al.[36] (4) | 1992 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Gobin et al.[36] (5) | 1992 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Headache |

| Gross et al.[37] (1) | 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Gross et al.[37] (2) | 2014 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Hähnel et al.[38] | 1998 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Haryu et al.[39] | 2014 | Yes | No | Yes | NA | No | No | No |

| Iwase et al.[40] | 2020 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Joseph et al.[41] | 2000 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Lumbar pain |

| Jun Li et al.[18] | 2004 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Kalamangalam et al.[21] | 2002 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Dizziness |

| Kamio et al.[11] | 2015 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Khan et al.[42] | 2009 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| Kim HJ et al.[43] | 2015 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Kim NH et al.[44] | 2011 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Kim WY et al.[45] | 2016 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Kleeberg et al.[46] | 2010 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Kulwin et al.[47] | 2012 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Altered mental status |

| Kvint et al.[48] | 2020 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Lagares et al.[49] | 2007 | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Lv et al.[50] | 2011 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Mascalchi et al. [51] (1) | 1996 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mascalchi et al.[51] (2) | 1996 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Narita et al.[52] | 1992 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Ogbonnaya et al.[53] | 2011 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Pannu et al.[54] | 2004 | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Partington et al.[55] (1) | 1992 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Erectile dysfunction |

| Partington et al.[55] (2) | 1992 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | No | NA |

| Patsalides et al.[16] | 2010 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Drop attacks |

| Peethambar et al.[16] | 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Erectile dysfunction |

| Peltier et al.[56] | 2011 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Occipital neuralgia |

| Perkash et al.[57] | 2002 | NA | NA | NA | NA | No | No | NA |

| Pop et al.[58] | 2015 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Seizure (GTCS) |

| Renner et al.[59] | 2006 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (1) | 1998 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Erectile dysfunction, left ear bruit, postural hypotension |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (2) | 1998 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (3) | 1998 | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Right exophthalmos, conjunctival hyperaemia, headache |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (4) | 1998 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Dysautonomia |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (5) | 1998 | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Headache |

| Rocca et al.[61] | 2019 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Rodriguez Rubio et al.[62] | 2019 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Roelz et al.[63] | 2015 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Satoh et al.[64] | 2005 | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Shimizu et al.[65] | 2019 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Singh et al.[66] | 2013 | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Sorenson et al.[67] | 2019 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Sugiura et al.[68] | 2009 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Pulsatile tinnitus |

| Sun et al.[69] | 2019 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tanaka et al.[70] | 2017 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Tanoue et al.[71] | 2005 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Trop et al.[72] | 1998 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tsutsumi et al.[73] | 2008 | No | No | No | No | No | No | Tinnitus, occipital neuralgia |

| Van Rooij et al.[74] (1) | 2007 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Van Rooij et al.[74] (2) | 2007 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Van Rooij et al.[74] (3) | 2007 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Versari et al.[75] (1) | 1993 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Versari et al.[75] (2) | 1993 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Brachialgia |

| Wang et al.[76] | 2019 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Wiesmann et al.[14] | 2000 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Occipital neuralgia |

| Willinsky et al.[77] | 1990 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Chest pain |

| Wrobel et al.[78] (1) | 1988 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Wrobel et al.[78] (2) | 1988 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Spasm |

| Wrobel et al.[78] (3) | 1988 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Yoshida et al.[79] | 1999 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Zhang et al.[80] | 2018 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

NA, not available; GTCS, generalized tonic–clonic seizure

Table 5.

Symptoms at diagnosis among patients with DAVF (N = 100)

| Author | Year | Motor | Sensory | Sphincteric disturbance | Ataxia | Brainstem symptoms | Dizziness, nausea, vomiting | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelsadg et al.[2] | 2016 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Vertigo |

| Abud et al.[23] | 2015 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Aixut et al.[24] | 2011 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Akkoc et al.[13] | 2006 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Asakawa et al.[25] | 2002 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Bernard et al.[17] | 2018 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Tinnitus |

| Bousson et al.[26] | 1999 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Bret et al.[15] | 1994 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (1) | 1996 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (2) | 1996 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (3) | 1996 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (4) | 1996 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (5) | 1996 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (6) | 1996 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Chen CJ et al.[27] (1) | 1998 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Chen CJ et al.[27] (2) | 1998 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Erectile dysfunction |

| Chen PM et al.[28] | 2018 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Chen PY et al.[29] | 2019 | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Vertigo |

| Chng et al.[30] | 2004 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Clayton et al.[31] | 2020 | Yes | No | NV | No | Yes | No | No |

| Copelan et al.[20] (1) | 2018 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Copelan et al.[20] (2) | 2018 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Copelan et al.[20] (3) | 2018 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Copelan et al.[20] (4) | 2018 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Deopujari et al.[32] | 1995 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| El Asri et al.[10] | 2013 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Enokizono et al.[22] (1) | 2017 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Enokizono et al.[22](2) | 2017 | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | No | No |

| Ernst et al.[33] (1) | 1997 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Ernst et al.[33] (2) | 1997 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ernst et al.[33] (3) | 1997 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Foreman et al.[34] | 2013 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Gaensler et al.[35] | 1989 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Erectile dysfunction |

| Gobin et al.[36] (1) | 1992 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Gobin et al.[36] (2) | 1992 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Gobin et al.[36] (3) | 1992 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Gobin et al.[36] (4) | 1992 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Gobin et al.[36] (5) | 1992 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Cervical pain |

| Gross et al.[37] (1) | 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Gross et al.[37] (2) | 2014 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Hähnel et al.[38] | 1998 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Haryu et al.[39] | 2014 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Iwase et al.[40] | 2020 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Joseph et al.[41] | 2000 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Jun Li et al.[18] | 2004 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Kalamangalam et al.[21] | 2002 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Kamio et al.[11] | 2015 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Khan et al.[42] | 2009 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Kim HJ et al.[43] | 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Kim NH et al.[44] | 2011 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Kim WY et al.[45] | 2016 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Kleeberg et al.[46] | 2010 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Kulwin et al.[47] | 2012 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Kvint et al.[48] | 2020 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Lagares et al.[49] | 2007 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Lv et al.[50] | 2011 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Mascalchi et al. [51] (1) | 1996 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Mascalchi et al.[51] (2) | 1996 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Narita et al.[52] | 1992 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Ogbonnaya et al.[53] | 2011 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Pannu et al.[54] | 2004 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Partington et al.[55] (1) | 1992 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Partington et al.[55] (2) | 1992 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Patsalides et al.[16] | 2010 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Peethambar et al.[16] | 2018 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Peltier et al.[56] | 2011 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Perkash et al.[57] | 2002 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Pop et al.[58] | 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Renner et al.[59] | 2006 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (1) | 1998 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (2) | 1998 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (3) | 1998 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (4) | 1998 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (5) | 1998 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Postural hypotension |

| Rocca et al.[61] | 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Rodriguez Rubio et al.[62] | 2019 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Roelz et al.[63] | 2015 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Blurred vision |

| Satoh et al.[64] | 2005 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Shimizu et al.[65] | 2019 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Singh et al.[66] | 2013 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Sorenson et al.[67] | 2019 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Sugiura et al.[68] | 2009 | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Sun et al.[69] | 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Tanaka et al.[70] | 2017 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Tanoue et al.[71] | 2005 | Yes | Yes | No | NV | No | No | No |

| Trop et al.[72] | 1998 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Tsutsumi et al.[73] | 2008 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Van Rooij et al.[74] (1) | 2007 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Van Rooij et al.[74] (2) | 2007 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Van Rooij et al.[74] (3) | 2007 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Versari et al.[75] (1) | 1993 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Versari et al.[75] (2) | 1993 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Wang et al.[76] | 2019 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Wiesmann et al.[14] | 2000 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Willinsky et al.[77] | 1990 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Wrobel et al.[78] (1) | 1988 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Wrobel et al.[78] (2) | 1988 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Wrobel et al.[78] (3) | 1988 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Yoshida et al.[79] | 1999 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Zhang et al.[80] | 2018 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

NA, not available

Table 6.

Brain MRI findings at diagnosis among patients with DAVF (N = 100)

| Author | Year | Swelling | Hyper T2 | Flow voids or abnormal vessels | Contrast enhancement | DWI abnormality | Thrombosis | T2* effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelsadg et al.[2] | 2016 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Abud et al.[23] | 2015 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Aixut et al.[24] | 2011 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| Akkoc et al.[13] | 2006 | NA | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Asakawa et al.[25] | 2002 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Bernard et al.[17] | 2018 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Bousson et al.[26] | 1999 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Bret et al.[15] | 1994 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (1) | 1996 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (2) | 1996 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (3) | 1996 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (4) | 1996 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (5) | 1996 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brunereau et al.[9] (6) | 1996 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Chen CJ et al.[27] (1) | 1998 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Chen CJ et al.[27] (2) | 1998 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Chen PM et al.[28] | 2018 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Chen PY et al.[29] | 2019 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Chng et al.[30] | 2004 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Clayton et al.[31] | 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Copelan et al.[20] (1) | 2018 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Copelan et al.[20] (2) | 2018 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Copelan et al.[20] (3) | 2018 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Copelan et al.[20] (4) | 2018 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Deopujari et al.[32] | 1995 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| El Asri et al.[10] | 2013 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Enokizono et al.[22] (1) | 2017 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Enokizono et al.[22](2) | 2017 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Ernst et al.[33] (1) | 1997 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Ernst et al.[33] (2) | 1997 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Ernst et al.[33] (3) | 1997 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Foreman et al.[34] | 2013 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Gaensler et al.[35] | 1989 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Gobin et al.[36] (1) | 1992 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Gobin et al.[36] (2) | 1992 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Gobin et al.[36] (3) | 1992 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Gobin et al.[36] (4) | 1992 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Gobin et al.[36] (5) | 1992 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Gross et al.[37] (1) | 2014 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Gross et al.[37] (2) | 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Hähnel et al.[38] | 1998 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Haryu et al.[39] | 2014 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Iwase et al.[40] | 2020 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Joseph et al.[41] | 2000 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Jun Li et al.[18] | 2004 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Kalamangalam et al.[21] | 2002 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Kamio et al.[11] | 2015 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Khan et al.[42] | 2009 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Kim HJ et al.[43] | 2015 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Kim NH et al.[44] | 2011 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Kim WY et al.[45] | 2016 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Kleeberg et al.[46] | 2010 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Kulwin et al.[47] | 2012 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Kvint et al.[48] | 2020 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Lagares et al.[49] | 2007 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Lv et al.[50] | 2011 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Mascalchi et al. [51] (1) | 1996 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Mascalchi et al.[51] (2) | 1996 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Narita et al.[52] | 1992 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Ogbonnaya et al.[53] | 2011 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Pannu et al.[54] | 2004 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Partington et al.[55] (1) | 1992 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Partington et al.[55] (2) | 1992 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Patsalides et al.[16] | 2010 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Peethambar et al.[16] | 2018 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Peltier et al.[56] | 2011 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Perkash et al.[57] | 2002 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Pop et al.[58] | 2015 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Renner et al.[59] | 2006 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (1) | 1998 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (2) | 1998 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (3) | 1998 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (4) | 1998 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Ricolfi et al.[60] (5) | 1998 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Rocca et al.[61] | 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Rodriguez Rubio et al.[62] | 2019 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Roelz et al.[63] | 2015 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Satoh et al.[64] | 2005 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Shimizu et al.[65] | 2019 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Singh et al.[66] | 2013 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Sorenson et al.[67] | 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Sugiura et al.[68] | 2009 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Sun et al.[69] | 2019 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Tanaka et al.[70] | 2017 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Tanoue et al.[71] | 2005 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Trop et al.[72] | 1998 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Tsutsumi et al.[73] | 2008 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Van Rooij et al.[74] (1) | 2007 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Van Rooij et al.[74] (2) | 2007 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Van Rooij et al.[74] (3) | 2007 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Versari et al.[75] (1) | 1993 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Versari et al.[75] (2) | 1993 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Wang et al.[76] | 2019 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Wiesmann et al.[14] | 2000 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Willinsky et al.[77] | 1990 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Wrobel et al.[78] (1) | 1988 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Wrobel et al.[78] (2) | 1988 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wrobel et al.[78] (3) | 1988 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Yoshida et al.[79] | 1999 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Zhang et al.[80] | 2018 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

NA, not available

Associations between sociodemographic, clinical and MRI variables, and CVF’s onset and outcomes

We initially investigated the association between age, gender, and outcome among the 100 patients with CVFs through non-parametric correlations and crosstabs, respectively. In both cases, results were not significant, suggesting that outcome was not related to the age (r = 0.065, p = 0.56) or gender (χ2 = 3.163, p = 0.075). We then tested for an association between an initial misdiagnosis and the disease’s outcome, but the chi square test was not significant (χ2 = 0.194, p = 0.66), suggesting that those who had an initial misdiagnosis had similar outcomes compared to those whose CVFs were diagnosed correctly at symptoms’ onset.

As for the association between diagnostic delay (in months) and type of onset, a non-parametric ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis test (2) = 15.540, p < 0.001) evidenced that those with an acute onset had a significantly lower interval to diagnosis compared to those with a progressive (p < 0.001) or multiphasic one (p = 0.049). All other comparisons were not significant. Interestingly, the association between diagnostic delay and outcome was also significant (U = 432.000, z = − 1.960, p = 0.050), with patients who experienced a disability or exited receiving their diagnosis months later compared to patients who experienced a good recovery.

As for the association between the presence of specific symptoms at onset (e.g., ataxia, sphincteric disturbances, motor or sensory ones) and diagnostic delay, those who experienced sensory symptoms at onset received their diagnosis of CVFs later than those who did not experience them (U = 749.000, z = 2.247, p = 0.025), while all other comparisons were not significant. As a follow-up analysis, and to better understand the unique contribution of sensory symptoms in explaining the diagnostic delay, we tested for the presence of significant differences in diagnostic delay between those who experienced only sensory symptoms at onset (N = 8) and those who experienced sensory symptoms together with other ones (N = 16). Though the Mann–Whitney U test is non-significant (U = 75.500, z = 1.308, p = 0.20), the between-groups effect size was medium (Hedge’s g = 0.65), suggesting that—with a larger sample size—this comparison would have reached the significance. As for the association between the presence of specific symptoms at onset and outcome, none of the chi square tests reached the significance.

Finally, we examined the association between spinal MRI findings at diagnosis, diagnostic delay, and outcome. In these analyses we focused exclusively on MRI swelling, T2 hyperintensities, flow voids, and contrast enhancement due to extremely low incidence of other MRI findings (DWI, T2* abnormalities, and thrombosis). Results showed that MRI findings were unrelated with both diagnostic delay and CVF outcome.

Detailed results, including frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations, separately for each group, are reported in the Supplementary Materials.

Discussion

The diagnosis of CVFs is challenging and often requires the expertise of highly specialized centers, leading to potential delays in diagnosis that can impact clinical outcomes and patients’ quality of life. Many patients, including the case discussed, receive a correct diagnosis only months or years after the onset of symptoms, when irreversible damage may have already occurred. One of the major challenges in diagnosing CVFs is that they are rarely considered in the initial diagnostic workup of myelopathies. Our CVF case was a starting point to conduct an analysis on the possible way to improve the outcome and to look for reliable clinical or radiological signs that could aid an earlier diagnosis.

Demographic features

Our analysis outlined that the mean age of onset was 56 years old, with most patients being males. These findings are in line with what has been described in a similar review conducted in 2013 [10], confirming CVFs as being a disease mainly affecting middle-aged patients, even though a few pediatric cases have been reported [7].

Clinical characteristic

The most prevalent type of onset was “progressive,” while the “acute” one was much less represented (13%) compared to the 25% reported in the literature [2], possibly because “multiphasic” onsets were considered “acute” in those other studies. The most common complaints at beginning were motor deficits (either paraparesis or quadriparesis) followed by sensory symptoms, sphincteric disturbances, dizziness, ataxia, and brainstem symptoms (Fig. 5). Interestingly, we found that only 9% of patients had brainstem signs, whereas El Asri and colleagues reported their presence in one-third of the patients [10]; this discrepancy may be due to the different definition of “brainstem signs” between the studies. It was also found that patients presenting with brainstem signs tended to have a shorter time to reach a correct diagnosis (see the “Diagnostic delay” section), which is consistent with current literature [11]. This may be because patients with brainstem signs are often mistaken for having a stroke and are promptly admitted to the emergency room. In cases where the onset is progressive and the pattern is that of an ascending myelopathy (which is the most common pattern), brainstem signs are less likely to appear early, and by the time they do, other symptoms may already be irreversible [2]. Another interesting finding is that patients presenting with only sensory symptoms tended to receive a correct diagnosis much later than those presenting with other symptoms. The most likely explanation is that sensory symptoms are common, easily missed during neurological examination, and their importance is often underestimated by clinicians and by patients themselves. Sensory symptoms are considered less disabling than motor symptoms, so patients may not consult a neurologist until motor symptoms occur, while neurologists may underestimate the subtle onset of sensory findings, often attributing them to radiculopathies or peripheral neuropathies.

Diagnostic delay

In this study the mean diagnostic delay was 5 months, a result slightly shorter than what had been previously reported (6–12 months) [7, 10]; this minimal difference with studies conducted years ago imply that very few progresses have been made in diagnosing CVFs during the last few decades. Interestingly, our patients with acute symptoms were more likely to be diagnosed correctly and sooner compared to those with progressive or multiphasic onsets. This could be because patients with acute symptoms are more likely to seek medical attention promptly, while those with progressive symptoms may delay seeking medical help for months, as stated in the “Clinical characteristics” section. This concept is of utmost importance since our analysis outlined that diagnostic delay has a significant impact on the outcome (see the “Outcome” section). As a matter of fact, patients experiencing the poorest prognoses (severe disability or death) had the longest time-to-correct diagnosis interval implying a relationship between these two variables. In other words, a longer diagnostic delay was often associated with a worse clinical outcome, suggesting that early diagnosis could not only lead to a reduction in mortality rate but also to a noticeable reduction of the residual disability. Although several studies have drawn the same conclusion in the past, our study managed to statistically support this hypothesis. In contrast, another study by Kamio et al. did not find a correlation between disease duration and prognosis, but did emphasize the importance of prompt and accurate diagnosis for improving symptoms and avoiding poorer outcomes (see the “Outcome” section) [11]. Of note, in the past some authors reported that even paraplegia can be reversible if the fistula is treated before the occurrence of ischemic and gliotic changes, pointing out the importance of early diagnosis and treatment [13, 14].

Misdiagnosis

In this setting, reaching the correct diagnosis in the shortest possible time and minimizing the misdiagnosis rate is pivotal. According to our numbers, more than half of the patients were initially misdiagnosed as having other diseases, including our own patient. This is a much more discouraging result than the previous 40.2% misdiagnosis rate reported by Kun Hou et al. in their review [6]. The most common reported misdiagnoses were spinal dural A-V fistulas [9], myelitis [15], tumors (mainly lymphoma [16] and glioma [17]), and strokes [13] (see Fig. 4). In one case stroke was suspected twice before the fistula was discovered [18], suggesting that CVF diagnosis is still challenging. Even if in terms of outcome, we did not find any statistically relevant difference between patients who received misdiagnosis and the ones who did not; misdiagnosis could potentially contribute to diagnostic delay, which in turn is associated with poorer outcomes.

It is important to notice that (1) mildly elevated CSF protein and absence of CSF pleocytosis (“albumino-cytological dissociation”) may occur in arteriovenous fistula and therefore should not necessarily be attributed to idiopathic transverse myelitis or Guillain-Barrè syndrome; (2) post steroid worsening should raise the suspicion about a non-inflammatory disease of the spinal cord, particularly a spinal or an intracranial fistula [19].

Imaging

While conventional angiography is still to be considered the gold standard for definite diagnosis of CVFs, MRI can strongly aid the diagnosis and dramatically shorten the time to diagnosis, especially when MRA sequences or contrast studies are carried out. Abnormal vascular flow voids, which are tortuous and dilated veins generally found on the dorsal or ventral surface of the spinal cord, were eventually found in 81.6% of patients, even when they were not reported initially [20, 21]. A high index of clinical suspicion is then required to carefully evaluate MRI images looking for flow voids so to reduce the interval to diagnosis and, accordingly, achieve a better outcome. Moreover, in the appropriate clinical context, flow voids help distinguishing CVFs from all other mimics (except spinal fistulas). Unfortunately, all other imaging features (i.e., T2/FLAIR hyperintensities and spinal cord swelling) are nonspecific. An interesting description was made by Copelan et al. who reported spinal edema as having a “a tigroid pattern” with geographic central medullary edema and sparing of the periphery as well as internal linear segments [20]. However, they did not include all cases of CVFs, making this differentiation based on tigroid appearance less suitable for generalization. Several other studies tried to find peculiar image findings (i.e., the “black butterfly sign” by Enokizono and colleagues [22]) but these remain isolated observations.

Outcome

Our analysis did not disclose any relationship between age, sex, and outcome, supporting the current knowledge about CVFs [10] and implying that the prognosis can be severe even in otherwise healthy young subjects. In our study sample, the percentages of moderate and poor recovery/death were 41.3% and 23.8%, respectively, while good recovery was only 32.9% which is consistent with the literature [10] and highlights that CVFs can still result in moderate/severe disability in two-thirds of cases. Moreover, there was no statistical relationship found between the presence of a specific subset of symptoms at onset and the outcome, suggesting that more compromised patients at onset do not necessarily have a worse prognosis. Similar findings have been reported in the literature, particularly regarding the lack of correlation between the severity of symptoms at onset and prognosis, except when signs of brainstem dysfunction are present, possibly due to the involvement of respiratory and cardiovascular centers in the brainstem [10, 11]. Unfortunately, no highly suggestive pattern of CVF symptoms that could shorten the time to diagnosis and lead to a better prognosis was identified in the analysis (see the “Diagnostic delay” section above).

Limitations

Our review has some intrinsic limitations: (1) it only includes Italian- and English-written articles, excluding some potentially interesting reports written in other languages; (2) it encompasses studies ranging from 1988 to 2021 during which time myelography has been substituted by MRI and MRI itself has become progressively more sophisticated so it was sometimes difficult to compare radiological data among the studies; (3) publications are mostly limited to single case reports and small case series; (4) many patients were lost on follow-up or received a very close range follow-up so that their actual long-term outcome is unknown; (5) in some cases, clinical data were scarce.

Conclusions and future directions

CVFs are rare and treatable conditions but, since their first clinical description, few progresses have been made in their early diagnosis. Despite the several innovations in surgery and neuroimaging introduced during the last four decades, CVFs still carry a moderate/severe grade of disability in two-third of cases; among the reasons we recognize late diagnosis and treatment. Our analyses show that diagnostic delay is more often associated with worse clinical outcomes, suggesting that early diagnosis could not only lead to a reduction of mortality rate but also to a noticeable reduction in residual disability. Interestingly, the latter is not associated with the severity of clinical picture, so more compromised patients do not necessarily show a worse outcome. Misdiagnosis itself is not associated with a poorer outcome but it can increase diagnostic delay which is, in turn, associated with poorer recoveries.

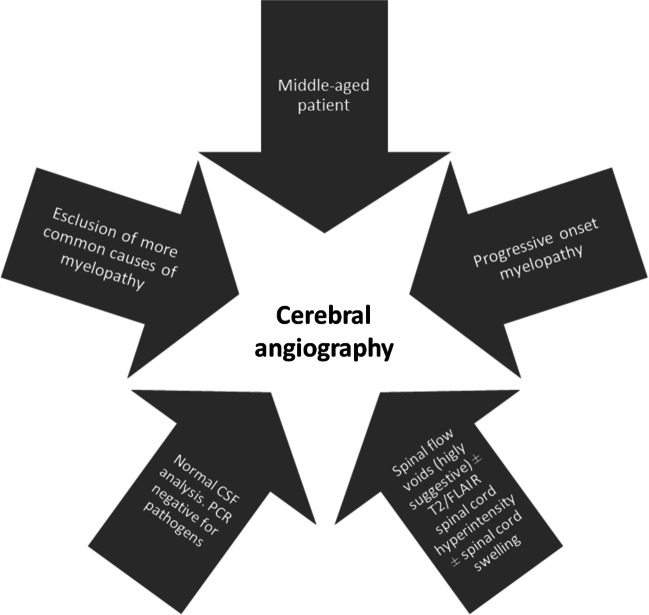

Unfortunately, we were not able to recognize any highly suggestive (“red flags”) CVF’s pattern of symptoms to shorten the time to diagnosis, but we can empirically suggest considering CVFs and conduct an angiography including cerebral vessels in a patient with slowly progressing/relapsing myelopathy when myelitis routine work-up is inconclusive.

The findings also emphasize the importance of careful investigation of spinal flow voids in appropriate clinical contexts, as they can provide valuable clues for CVFs and help distinguish them from other mimics, except for spinal fistulas. Prompt extension of angiographic studies to intracranial vessels is suggested when spinal angiography is unremarkable in suspected cases of CVFs [9-11]. Other imaging features were found to be non-specific and could potentially lead to misdiagnosis. Suggestions on when to perform a cerebral angiography are reported in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Red flags for performing a cerebral angiography