Abstract

Background:

Early introduction of palliative care can improve patient-centered outcomes for older adults with complex medical conditions. However, identifying the need for and introducing palliative care with patients and caregivers is often difficult. We aim to identify how and why a multi-setting approach to palliative care discussions may improve the identification of palliative care needs and how to facilitate these conversations.

Methods:

Descriptive qualitative study to inform the development and future pilot testing of a model to improve recognition of, and support for, unmet palliative care needs in home health care (HHC). Thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews with providers across inpatient (n = 11), primary care (n = 17), and HHC settings (n = 10).

Results:

Four key themes emerged: 1) providers across settings can identify palliative care needs using their unique perspectives of the patient’s care, 2) identifying palliative care needs is challenging due to infrequent communication and lack of shared information between providers, 3) importance of identifying a clinical lead of patient care who will direct palliative care discussions (primary care provider), and 4) importance of identifying a care coordination lead (HHC) to bridge communication among multi-setting providers. These themes highlight a multi-setting approach that would improve the frequency and quality of palliative care discussions.

Conclusions:

A lack of structured communication across settings is a major barrier to introducing and providing palliative care. A novel model that improves communication and coordination of palliative care across HHC, inpatient and primary care providers may facilitate identifying and addressing palliative care needs in medically complex older adults.

Keywords: palliative care, team-based care, care coordination, end-of-life care, communication, home health care

Introduction

People who receive home health care (HHC) are often older adults with complex medical conditions and have multiple teams managing their care across settings. Poor communication between inpatient, primary care, and HHC can exacerbate patients’ risk for negative outcomes. Prior research shows that communication failures between HHC and providers in other settings (i.e., inpatient, primary care) are associated with a higher probability of hospital readmission, medication errors, and suboptimal patient safety.1,2 Systematic reviews confirm that the transition from hospital to HHC is a vulnerable point for patients and have called for research that supports these transitions within the context of palliative care provision.3

Older Medicare beneficiaries referred for HHC have hospital readmission rates that can exceed those of patients discharged to skilled nursing facilities and an 18% mortality rate within the first year of starting HHC.4–6 Despite the high risk for mortality and hospital readmissions in older adults receiving HHC, few studies have identified approaches to meet and address unmet palliative care needs for this patient population. While palliative care can reduce healthcare utilization, much palliative care is delivered in the hospital near the end of life1 rather than at home.7–11

One barrier to the early introduction of palliative care is provider reluctance to discuss palliative care with patients and caregivers.12 For example, some providers feel that palliative care is incompatible with other treatments and that it conveys “giving up” on the patient.13 Additionally, solutions to address these challenges often focus on support for individual or specialist providers, such as oncologists, rather than improving coordination and information sharing across settings and providers.3,14–16

To guide development and future pilot testing of a model to identify and address unmet palliative care needs among older adult HHC patients and their family caregivers across multiple settings, we conducted a qualitative descriptive study that addresses the following questions: (1) how can a coordinated multi-setting (i.e., inpatient, primary care, HHC) approach improve the early identification of palliative care needs, and (2) what is the best way to overcome existing communication challenges to facilitate these conversations?

Methods

Study Design

We conducted semi-structured interviews with key individuals involved in the care of older adults with complex medical conditions from hospitalization to HHC. This included providers across inpatient (physicians, nurse practitioners, social workers), primary care (physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, social workers), and HHC (nurses, social workers, occupational therapists, and leadership) settings. These data were collected as part of a larger study aiming to inform the development and future pilot testing of a model to improve recognition of, and support for, unmet palliative care needs in HHC. Reporting follows the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) guidelines.17 Ethical approval was obtained from the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board (#20-0259). Participation was voluntary and all participants provided informed consent.

Participants & Recruitment

Interviewees were recruited from HHC agencies (n = 2), hospitals (n = 2, academic and Veterans Administration (VA)), and primary care clinics (n = 7) in Colorado. Our rationale was that these individuals could inform priorities for the planned pilot. Interviewees were recruited using purposeful sampling through team members with pre-existing clinical relationships. One non-clinician member of the team with qualitative research experience conducted interviews to minimize potential bias from preexisting relationships. Recruitment continued until saturation for each subgroup was reached.18

Data Collection

The interview guide was developed using the Practical Robust Implementation Sustainability Model (PRISM).19 Questions included participants’ experiences and needs around identifying and addressing palliative care needs across inpatient, primary care, and HHC settings (Supplementary Material Appendix 1). Participants provided brief demographic information following the interviews. Interviews were conducted by phone, audio recorded, professionally transcribed by a University-affiliated, HIPAA approved transcription service, and de-identified. ATLAS.ti (version 9.0) software was used to facilitate data management.

Data Analysis

Study members with qualitative research training and experience analyzed the interview data using thematic analysis.20 First, a list of codes was developed from iterative review of transcripts. Codes were applied to transcripts. A subset of the transcripts was double coded by another team member to ensure coding consistency.21 Coded data were analyzed within individual interview transcripts and across all interviews in the dataset to identify major themes. This process involved (1) combining, comparing, and making connections between codes based on review of coded data reports, (2) writing analytic memos to summarize coded data reports and record salient themes, quotes, and impressions, and (3) frequent team meetings to discuss emerging patterns. Investigator triangulation (multiple investigators with multiple areas of expertise) was used to establish the trustworthiness of our findings.22

Results

The 38 interview participants in this study included inpatient providers (n = 11) (physicians, nurse practitioner, social worker) and primary care providers (PCPs) (n = 17) (physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, social workers) from two health systems (University and VA), and HHC providers (nurses, social workers, occupational therapists, and leaders) at agencies affiliated with the University and VA (n = 10) (Table 1). The mean age was 46.7 years, 29 (76.3%) were female, and 31 (81.6%) were white. On average, interviews lasted 37 minutes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants.

| Characteristic | Mean (range) | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 47 (30-74) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 9 (23.7%) | |

| Female | 29 (76.3%) | |

| Race | ||

| White | 31 (81.6%) | |

| Asian | 6 (15.8%) | |

| Mixed | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Setting/Discipline | ||

| Inpatient | 11 (28.9%) | |

| Physician | 9 (81.8%) | |

| Nurse Practitioner | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Social worker | 1 (9.1%) | |

| Primary care | 17 (44.7%) | |

| Physician | 11 (64.7%) | |

| Nurse practitioner | 2 (11.8%) | |

| Social worker | 3 (17.6%) | |

| Other | 1 (5.9%) | |

| Home health | 10 (26.3%) | |

| Leadership (administrators, managers, directors) | 4 (40%) | |

| RN/PT/OT | 2 (20%) | |

| Social work | 2 (20%) | |

| Hospice | 2 (20%) | |

| Facility | ||

| University hospital | 20 (71.4%) | |

| VA medical center | 8 (28.6%) | |

| Highest degree | ||

| Associate | 3 (7.9%) | |

| Bachelor’s | 0 (0%) | |

| Master’s | 11 (28.9%) | |

| Doctoral | 23 (60.5%) | |

| Other | 1 (2.6%) |

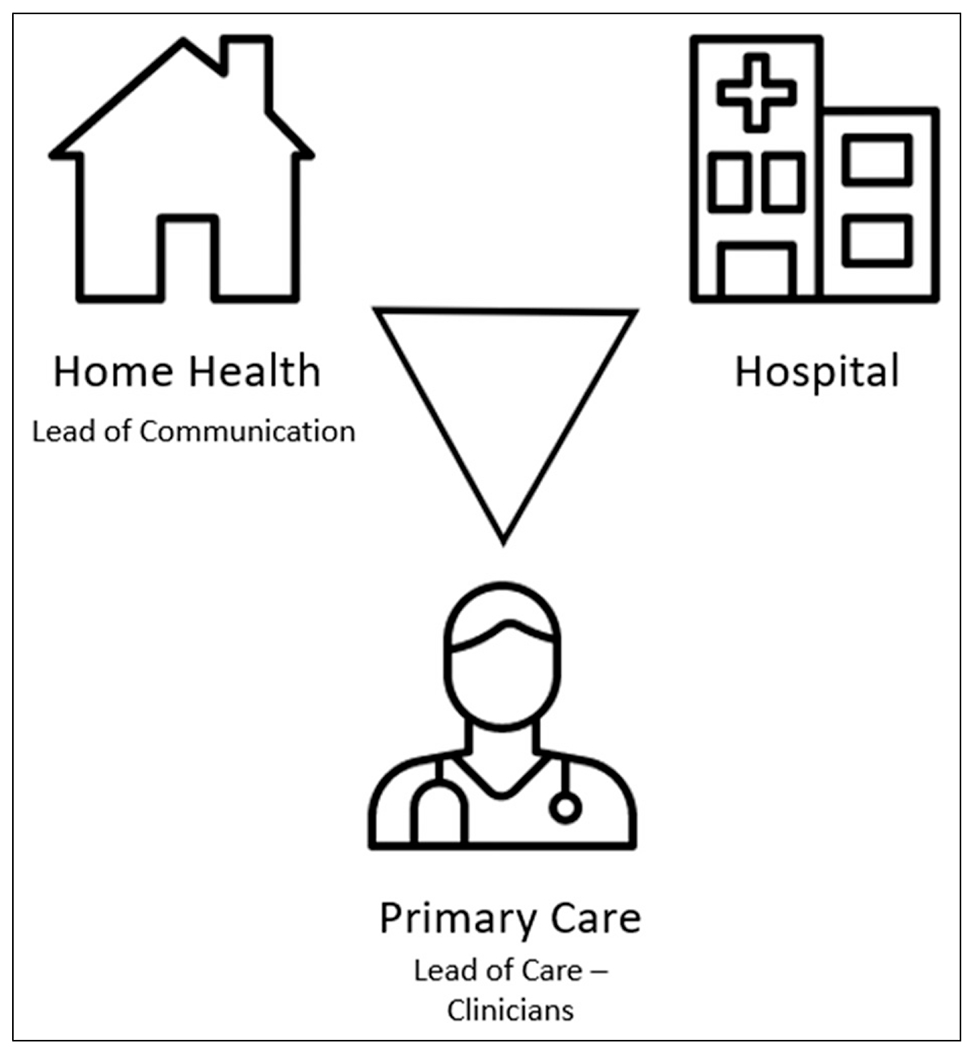

We identified four high-level themes: (1) providers across settings can identify palliative care needs based on their unique perspective of each patient, (2) identifying palliative care needs is challenging due to infrequent communication and lack of shared information among providers across settings, (3) importance of identifying a clinical lead of patient care to direct palliative care discussions, and (4) importance of identifying a care coordination lead to bridge communication among multi-setting providers. Together, these themes highlight the need for a triadic communication approach (Figure 1) for identifying and addressing palliative care needs for HHC patients. This approach could help improve the frequency and quality of palliative care discussions.

Figure 1.

Multi-setting approach to palliative care discussions with medically complex patients.

Providers Across Settings Can Identify Palliative Care Needs

Participants felt that older adults with complex medical conditions, poor prognoses, and/or caregiver burden could benefit from earlier introduction to palliative care. They explained that these patients receive frequent care from providers across multiple settings, particularly primary care, HHC, and inpatient care:

“[I had] a patient that was living at home with her husband and she was falling all the time and was back and forth into the hospital…It was almost to the point where I was [considering] calling Adult Protective Services because the husband really couldn’t take care of her…But palliative care wasn’t involved in that, and sometimes I think most people consider palliative care for cancer patients or patients in a lot of pain, but I think that palliative care could have been beneficial for this patient.” (PCP-14)

Interviewees reported that providers across different settings could help identify palliative care needs for patients by drawing on each provider’s unique perspective. That is, participants explained that each provider has access to different cues that palliative care may be needed based on their setting and relationship to the patient. For example, one HHC clinical manager explained that “we may [have] a little more insight into [the patient’s] actual behaviors [and] actual medical status just because we’ve had more time with them…in their real-world context” (HHC-2). Participants reported that inpatient providers (inclusive of physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses and others) could identify repeated hospitalizations, escalations in disease progression or limited prognosis, or new symptoms during the hospitalization, while PCPs could draw on their knowledge of the patient’s medical history to identify palliative care needs. As one HHC participant explained:

“Probably all of them [can identify palliative care needs]…definitely the PCP because he knows the patient the best, because they’ve been with them for…in a lot of cases, years. Sometimes twenty, thirty years. The [inpatient provider], they see things from a different perspective because I think they’re a little bit more realistic with okay, here’s where we’re at and, you know, the patient keeps coming into the hospital… and this is why.” (HHC-1)

Together, providers across primary care, HHC, and inpatient settings have many opportunities to collectively identify and address palliative care needs. Then, as part of a model of care, inpatient providers at the time of discharge can communicate the relevant palliative care needs and changes that occurred throughout the hospitalization. Participants felt that unifying perspectives across settings added value by painting a more complete picture of the patient’s health status:

“You never know who’s going to see the situation that triggers ‘hey, something’s wrong here, right?’…if it’s the nurse that’s seeing the patient on a regular basis and is in the room a hell of a lot more than the doctor…If it’s the care management team that’s working on this complicated discharge and had multiple family meetings with the primary care doc…for the system to work, everybody has to feel comfortable saying ‘hey, I see a problem’.” (PCP-18)

Identifying Palliative Care Needs Is Challenging due to Infrequent Communication and Lack of Shared Information Among Providers Across Settings

Despite identifying opportunities to detect patient and caregiver needs across these care settings, participants reported that doing so is challenging due to infrequent communication and lack of shared information among providers across these settings. Without an established means to connect these perspectives and knowledge, each provider lacks the full picture of the patient’s health and may not independently identify palliative care needs.

Participants reported that without established, structured communication across this triad of PCP, HHC and inpatient providers, there can be confusion about what each provider knows, recommends, and is responsible for. As a result, providers described hesitation initiating sensitive palliative care conversations—even if the need has been identified—without coordinating with other providers. As one inpatient physician explained, they ‘hope for the best’ since this multi-setting communication structure does not exist:

“Unfortunately, I don’t actually indicate to the home health team… that the patient needs something. My hope is that if I’m arranging community palliative care, that they’re thinking about [how] the patient’s needs have changed, but I do not directly communicate with the home health team…I’m hoping that our care managers are setting it up like talking through some of the complexities of their situation…” (Inpatient physician-22)

Additionally, participants explained that deciding how and when to initiate a palliative care discussion also depended on factors such as the patient’s history, living situation, family dynamics, and physical or mental health status. PCPs offer a longitudinal, but intermittent, perspective on these factors that HHC providers can supplement with current observations in patients’ homes. Inpatient providers have high touch contact with patients and can assess how this hospitalization may result in changes in subsequent physical and mental status. However, participants explained that this information is not uniformly communicated across these providers, which can lead to missed opportunities to initiate palliative care:

“[The patient] so hung up on… who is going to feed my cat and take care of my apartment and make sure I don’t get evicted if I go to the hospital…[I think] that palliative care might have been a really good option because it could… [help her] make a decision…there was a big lack of communication from the hospital…I don’t know that they explained or discussed it with the patient because…they didn’t understand where she was with her mental status and her decision-making skills.” (HHC-4)

Identifying a Clinical Lead of Patient Care to Direct Palliative Care Discussions

Although participants thought that the lack of structured communication between inpatient, primary care, and HHC providers made it more difficult to identify palliative care needs and to determine the best way to introduce palliative care, they felt that these problems could be resolved with two changes. The first strategy participants described was to identify a lead of care for each patient. Participants felt that the PCP would likely serve as the lead of care, though they acknowledged that this may differ for some patients (e.g., oncology patients):

“I think the communication piece, the goal setting piece, the coming to grips with the reality of progressive grim chronic illness, my bias is that’s a clinician piece and not something for the home health aide or even the nurse and so I guess that aspect of care I view as being mainly in the clinician’s domain.” (PCP-12)

While each team member has the capacity to identify palliative care needs based on their unique perspective, participants felt that the task of initiating this conversation was best done by the lead of care because this clinician would be most likely to have an ongoing long-term relationship with the patient. As one home health social worker explained, “a lot of our people who are much older have a very trusting relationship with the PCP [and] trust them more than us, so if they hear [about palliative care] from them first, that’s always more beneficial” (HHC-6). However, participants felt that it was important for the lead of care to receive input from the HHC team before initiating a conversation about palliative care:

“I think the best suited will be the primary care doctor with feedback and input from the home health staff [who]…see the patient more often. If a patient has a home health order usually we see them at least once or twice a week so we can give feedback to the [PCP] and [they] can take our feedback and combine with [their knowledge of the patient’s] medical condition.” (HHC-3)

This strategy would improve the frequency of palliative care discussions by clarifying which provider across multiple settings would be responsible for initiating the introduction of palliative care (and ordering palliative care when needed)—thus, removing hesitation about division of labor that might otherwise prevent a provider from having this discussion or assuming someone else would be taking care of it.

Identifying a Care Coordination Lead to Bridge Communication Among Multi-Setting Providers

The second suggestion participants described was to identify a lead of care coordination to bridge communication among multi-setting providers. Participants felt that designating this responsibility would improve palliative care discussions by providing a structured means to integrate team perspectives and share them with the lead of care prior to palliative care discussions. Most participants felt that HHC providers would be best suited to serve as the care coordination lead because they have the most current view of the patient’s health in their own (home) context. One participant explained how this makes HHC providers uniquely positioned to facilitate communication about palliative care:

“A lot of our patients aren’t going in for regular doctor’s appointments ‘cause they can’t get out or they don’t want to. It’s just that disconnect too and the doctor is like ‘hey, I haven’t even seen this person, let alone [know] if they’re appropriate for palliative or hospice’, but a lot of the times the doctor really trusts us.” (HHC-6)

Participants recognized that although direct communication channels between HHC, PCP, and inpatient providers were desired, they were largely unavailable. Participants across roles reported that the best solution to this problem was simple: a phone call or instant message. For the few HHC participants who did have access to a direct phone number for a patient’s PCP, this arrangement worked out well:

“We had each other’s phone numbers and would text. I always find that to be amazingly helpful…to be able to bypass the phone tree [and] just get straight to the doctor and nurse practitioner…we had a very cordial relationship and we’re able to communicate quickly.” (HHC-15)

A Multi-Setting Approach to Palliative Care Discussions with Medically Complex Patients

Together, these suggestions inform a multi-provider approach to identifying, communicating, and addressing palliative care needs that could improve early use of palliative care for medically complex older patients. This approach involves clearly defining provider roles and creating structured communication channels to facilitate information sharing. As shown in Figure 1, inpatient providers can communicate with HHC on discharge to share observations of patients’ needs such as repeated hospitalizations and escalations in disease progression indicating potential palliative care needs as they transition from hospital care into HHC and primary care. HHC providers serve as the care coordination lead and take responsibility for collecting patient information across providers, and communicating this holistic patient perspective with the clinical lead of patient care (likely, the PCP). After receiving input from the care coordination lead, PCPs can then initiate discussions about palliative care with patients and tailor them to each patient’s medical history and current circumstances.

Discussion

Addressing palliative care needs for medically complex patients improves quality of life and symptom burden and can lower healthcare utilization.7 However, few studies have addressed palliative care supports for patients receiving HHC in the US.23 We address this gap by highlighting the perspectives of multiple stakeholders to show that clinicians across settings can help identify palliative care needs using their unique perspectives of the patient’s care. However, we also found that doing so is challenging due to infrequent communication and lack of shared information. We identified two strategies to address these issues, including a) identifying a clinical lead of patient care to direct palliative care discussions, and b) identifying a care coordination lead to bridge communication among providers in different settings.

This multi-setting approach to identifying palliative care needs for HHC patients could improve the early introduction of palliative care supports by addressing confusion among team members regarding who is responsible for initiating palliative care.16 Our findings actually split the notion of “initiating palliative care” into two distinct dimensions: the need for one team member to integrate communications about unmet palliative needs (theme 4) and the need for another to direct those palliative care discussions with patients and caregivers (theme 3). Our findings that PCPs may optimally serve as the lead of care aligns with other studies that recognize PCPs’ desire to introduce the topic and participate in the delivery of primary palliative care for patients with serious illness.24 However, our approach relies on establishing a more direct line of communication between HHC, PCP, and inpatient providers. This aligns with previous work that has called for direct phone lines between clinicians to improve inadequate communication and its consequences, but may be difficult to implement consistently.1,25 Our findings suggest that direct communication via secure e-messaging platforms—an indicator of high-quality care coordination among teams that include HHC—may be an alternative.26 Secure e-messaging platforms are used to send texts both in hospital and home health settings, and can help reduce conflicting information.27,28 However, secure texts may be most effective when they are concise and when used in combination with follow-up phone calls.29,30

Although our multi-stakeholder theme that positions HHC as lead of care coordination may seem aspirational, some of the infrastructure to support this already exists. For example, many home health agencies are already incurring the cost to have access to the hospital’s EHR to pull together clinical information necessary to start care ordered in the hospital and continue a plan of care ordered by the PCP. However, for HHC to become the lead of care coordination, the communication would need to become structured, concise, and bidirectional between HHC and the PCP.

While previous research shows that many older adults could benefit from palliative care,7 this could be especially relevant for patients and caregivers who are experiencing HHC for the first time and may have unclear expectations of care.31,32 Because this study included a range of stakeholder perspectives across university medical center and VA settings, our findings may be applicable to multiple populations and medical contexts.

This study has some limitations. Data was collected in one geographic location and represented HHC clinicians from only two organizations. However, our sample of clinicians and staff reflects national workforce characteristics and included clinicians practicing in both a university-affiliated academic medical center and a VA medical center. Yet, the perspectives expressed by individuals we interviewed may not be generalizable to a broader population. Future work should examine the feasibility and adaptations that may be required in other locations and settings. Additionally, there is a need to address institutional and policy considerations that impact palliative care delivery (e.g., reimbursement).

In summary, this study suggests that the outcomes of patients receiving HHC could be improved with early identification of unmet palliative care needs and coordinated introduction of palliative care. However, care coordination across providers in multiple settings does not readily account for involvement of HHC providers. We outline an approach that emphasizes the roles of primary care, inpatient and HHC providers in early identification and coordination of palliative care that could support patients’ and caregivers’ preferences. This approach could apply to other contexts involving patients with complex health conditions who receive care from multiple providers across settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants who contributed to this work by sharing their perspectives. The authors would also like to thank the members of our expert advisory panel, whose insights helped to guide this work. This work is funded by a National Institute on Aging grant (R21AG067038), which supports effort for the following authors: Caroline K. Tietbohl, Ashley Dafoe, Sarah R. Jordan, Amy G. Huebschmann, Hillary D. Lum, and Christine D. Jones. The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of the article. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Aging, the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This work was presented at the 2021 International Conference on Communication in Healthcare.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Pesko MF, Gerber LM, Peng TR, Press MJ. Home Health Care: Nurse-Physician Communication, Patient Severity, and Hospital Readmission. Health Service Research; 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones CD, Jones J, Richard A, et al. “Connecting the dots”: A qualitative study of home health nurse perspectives on coordinating care for recently discharged patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(10):1114–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Killackey T, Lovrics E, Saunders S, Isenberg SR. Palliative care transitions from acute care to community-based care: a qualitative systematic review of the experiences and perspectives of health care providers. Palliat Med. 2020;34(10):1316–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avalere, Home Health Chartbook. Prepared for the Alliance for Home Health Quality and Innovation; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werner RM, Coe NB, Qi M, Konetzka RT. Patient outcomes after hospital discharge to home with home health care vs to a skilled nursing facility. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(5):617–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sullivan SS, Hewner S, Chandola V, Westra BL. Mortality risk in homebound older adults predicted from routinely collected nursing data. Nurs Res. 2019;68(2):156–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(20):2104–2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Min L, Saul DA, Firn J, Chang R, Wiggins J, Khateeb R. Interprofessional geriatric and palliative care intervention associated with fewer hospital days. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(2):398–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SL, Tarn DM. Effect of primary care involvement on end-of-life care outcomes: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(10):1968–1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller SC, Lima JC, Intrator O, Martin E, Bull J, Hanson LC. Palliative care consultations in nursing homes and reductions in acute care use and potentially burdensome end-of-life transitions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):2280–2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative care for the seriously ill. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(8):747–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leclerc-Loiselle J, Legault A. Introduction of a palliative approach in the care trajectory among people living with advanced MS: perceptions of home-based health professionals. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2018;24(6):264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schenker Y, Crowley-Matoka M, Dohan D, et al. Oncologist factors that influence referrals to subspecialty palliative care clinics. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(2):e37–e44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hay CM, Lefkowits C, Crowley-Matoka M, et al. Strategies for introducing outpatient specialty palliative care in gynecologic oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13(9):e712–e720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brighton LJ, Koffman J, Hawkins A, et al. A systematic review of end-of-life care communication skills training for generalist palliative care providers: Research quality and reporting guidance. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54(3):417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sussman T, Kaasalainen S, Lee E, et al. Condition-specific pamphlets to improve end-of-life communication in long-term care: staff perceptions on usability and use. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(3):262–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Fiel Meth. 2006;18(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCreight MS, Rabin BA, Glasgow RE, et al. Using the practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) to qualitatively assess multilevel contextual factors to help plan, implement, evaluate, and disseminate health services programs. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(6):1002–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saldaña J. In: Angeles L, Calif, eds The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 3rd edition. London: SAGE; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denzin NK. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods. 1st edition. Somerset: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ratner E, Norlander L, McSteen K. Death at home following a targeted advance-care planning process at home: the kitchen table discussion. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(6):778–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nowels D, Jones J, Nowels CT, Matlock D. Perspectives of primary care providers toward palliative care for their patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(6):748–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones CD, Vu MB, O’Donnell CM, et al. A failure to communicate: a qualitative exploration of care coordination between hospitalists and primary care providers around patient hospitalizations. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(4):417–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fathi R, Sheehan OC, Garrigues SK, Saliba D, Leff B, Ritchie CS. Development of an interdisciplinary team communication framework and quality metrics for home-based medical care practices. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(8):725–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh C, Siegler EL, Cheston E, et al. Provider-to-provider electronic communication in the era of meaningful use: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):589–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gandhi TK, Keating NL, Ditmore M, et al. Improving referral communication using a referral tool within an electronic medical record. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches. Bethesda: National Institute of Health, 3; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy DR, Reis B, Kadiyala H, et al. Electronic health record-based messages to primary care providers: valuable information or just noise? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(3):283–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh H, Thomas EJ, Mani S, et al. Timely follow-up of abnormal diagnostic imaging test results in an outpatient setting: are electronic medical records achieving their potential? Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(17):1578–1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones CD, Jones J, Bowles KH, et al. Patient, caregiver, and clinician perspectives on expectations for home healthcare after discharge: a qualitative case study. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(2):90–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones CD, Jones J, Bowles KH, et al. Quality of hospital communication and patient preparation for home health care: results from a statewide survey of home health care nurses and staff. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 20, 487, 491, . 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.