Highlights

-

•

Continuous glucose monitoring devices provide similar results on repeat testing in the home setting regarding time spent >140 mg/dL of 17.5% or more and time spent >180 mg/dL of 3.4% or more.

-

•

Continuous glucose monitoring devices provided discrepant results regarding time spent >140 mg/dL of 4.5% in 1/4 cases.

-

•

At-home mixed meal tolerance tests can safely be assessed on continuous glucose monitoring devices, but methods to ensure protocol adherence and thresholds to define abnormality are needed.

Keywords: Cystic Fibrosis Related Diabetes, Continuous glucose monitor, Reproducibility, Screening

Abstract

Background

Cystic fibrosis related diabetes (CFRD) is associated with insulin-remediable pulmonary decline, so early detection is critical. Continuous glucose monitors (CGM) have shown promise in screening but are not recommended by clinical practice guidelines. Little is known about the reproducibility of CGM results for a given patient.

Methods

Twenty non-insulin treated adults and adolescents with CF placed an in-home CGM and wore it for two 14-day periods. Participants underwent a mixed meal tolerance test (MMTT) on day 5 of each 14-day period. Glycemic data from CGM 1 and CGM 2 were compared regarding published thresholds to define abnormality: percent time >140 mg/dL of ≥4.5%, percent time >140 mg/dL of >17.5%, and percent time >180 mg/dL of >3.4%. Results of the repeat MMTT were compared for peak glucose and 2-hour glucose thresholds: >140 mg/dL, >180 mg/dL, and >200 mg/dL.

Results

For percent time >140 mg/dL of ≥ 4.5%, five of 20 subjects had conflicting results between CGM 1 and CGM 2. For percent time >140 mg/dL of >17.5% and >180 mg/dL of >3.4%, only one of 20 subjects had conflicting results between CGM 1 and CGM 2. On the MMTT, few participants had a 2-hour glucose >140 mg/dL. Peak glucose >140 mg/dL, 180 mg/dL, and 200 mg/dL were more common, with 10–37% of participants demonstrating disagreement between CGM 1 and CGM 2.

Conclusions

Repeated in-home CGM acquisitions show reasonable reproducibility regarding the more stringent thresholds for time >140 mg/dL and >180 mg/dL. More data is needed to determine thresholds for abnormal mixed meal tolerance tests in CFRD screening.

Introduction

Cystic fibrosis related diabetes (CFRD) is a common extrapulmonary complication of cystic fibrosis (CF), impacting approximately 20% of youth and 40–50% of adults living with CF [1]. CFRD is associated with a decline in weight and pulmonary function that is preventable with early initiation of insulin therapy [2], [3]. Therefore, CFRD screening is critical to prolonging the lives of people living with CF.

Current guidelines recommend annual oral glucose tolerance testing (OGTT) for all people with CF over age 10 years [1]. Unfortunately, adherence with recommended OGTT is poor with fever than 50% of eligible adult patients performing the screening test each year at most centers [4]. Cited barriers to OGTT completion include the 2-hour time commitment, lack of perceived benefit, and distaste of the concentrated glucose drink [5]. OGTTs have also been observed to have low reproducibility, with repeat testing often providing a different diagnosis, undermining the confidence of patients and healthcare providers [5], [6], [7], [8]. Low OGTT completion rates have prompted investigation into alternative CFRD screening methodologies such as the use of continuous glucose monitor (CGM) devices [9], [10], [11], [12].

A major challenge in the implementation of CGM for CFRD screening is the absence of identified thresholds above which CFRD should be diagnosed and insulin initiated [11]. Hameed and colleagues in 2010 identified 4.5% of time >140 mg/dL as being associated with poor weight gain in children with CF and, later, found improved weight and lung function with insulin therapy [12], [13]. Frost later demonstrated improvement in pulmonary function using insulin in people with CF (pwCF) exceeding this threshold, though importantly, these were not randomized trials [12], [14]. In 2022 Scully and colleagues found that spending 3.5% of time >180 mg/dL or 17.4% of time >140 mg/dL predicted an abnormal OGTT [15]. While these cutoffs are not yet accepted for use in CFRD diagnosis, the evidence base for using CGM in diabetes screening is building.

Several studies have demonstrated that average glucose and coefficient of variation (CV), a measure of glucose variability, are similar on repeated CGM acquisitions [15], [16], [17]. Clinical application of CGM as a screening tool will require that repeated CGM acquisitions provide consistent results with regard to diagnostic thresholds, as lack of reproducibility has undermined confidence in the OGTT [5], [6], [7]. Additional questions about the dietary advice given to patients during the CGM acquisition and whether a standardized meal or meal replacement drink may help with data interpretation also remain to be addressed. We sought to address these questions by performing two consecutive at-home CGM acquisitions with mixed meal tolerance tests in non-insulin treated adolescents and adults with CF.

Methods:

Study Population

Twenty adult and adolescent patients (ages 14–50 years) not treated with insulin or anti-hyperglycemic agents were recruited from the LeRoy W. Matthews CF Center between April and December 2021. Individuals with an adhesive allergy, routine ingestion of high doses of vitamin C (>500 mg per day), intentional adherence to a low carbohydrate diet (<100 g per day), pregnancy, recent hospitalization or pulmonary exacerbation or glucocorticoid use within the past month were excluded. All participants provided informed consent and the study was approved by the University Hospitals Institutional Review Board. Due to the limitations associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, the study was designed such that all study activities were performed virtually.

CGM use

Each subject wore a blinded CGM (Freestyle Libre Pro, Abbott, Abbott Park, IL) for two separate 14-day periods with 1–3 weeks off between CGM wear periods [18], [19], [20]. During each 14-day wear period, subjects kept a 3-day dietary log during days 2–4 and performed a fasting mixed meal tolerance test (MMTT) on day 5 (Boost High Protein, Very Vanilla, Nestle Health Sciences, Veley, Switzerland). Boost High Protein Vanilla (237 mL, 250 calories, 6 g of fat, 20 g of protein, and 31 g of carbohydrate) was selected because the higher protein content may reduce risk for post-prandial hypoglycemia and this product has been used in large studies of patients with type 1 diabetes [21]. Participants fasted from food or drink for eight hours before and three hours following Boost ingestion and were instructed to eat their typical diet for the remaining days of CGM wear. Subjects were provided a study booklet to record their three-day meal log and the time of Boost ingestion.

Demographic data

Demographic and historical data including age, body mass index (BMI), pulmonary function, CFTR variants, Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) results, OGTT results and history of insulin use was collected from the electronic medical record. HbA1C was collected if it was taken within 1 year of the CGM start. Glycemic category was assigned based on the most abnormal clinical OGTT within the past 5 years.

Glucose data

Glucose data was extracted from the CGM sensors using LibreView software (Abbott, Abbot Park, IL) and transferred to SAS v. 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA) for analysis. Days with <24 h of complete data, often day 1 and day 15 of each CGM, were excluded from analysis to avoid uneven weighting of day and night time measures. The day of Boost ingestion was analyzed separately and excluded from calculation of glycemic averages. Therefore, a maximum of 13 days of full data were available for calculation of averages. If additional days were missing, the missing days were excluded from both CGMs.

Statistical methods

As this was designed as a descriptive study, no formal statistical tests were employed for the primary outcome. Data listings are provided, and proportions given in the text as appropriate. Average glucose for all non-MMTT days with respective coefficient of variation (CoV) is listed for each subject; percent time >140 mg/dL and percent time >180 mg/dL was determined for each CGM and presented as percent of total time. The following thresholds were used to define a positive screen: percent time >140 mg/dL of ≥4.5%, percent time >140 mg/dL of >17.4%, and percent time >180 mg/dL of >3.4%. The primary outcome is the classification of a positive or negative screen. For each subject, CGM 1 and CGM 2 were assessed for agreement based on this classification. Secondarily, as an added description of data, the difference between the average glucose at CGM1 and CGM2 was determined for each subject and a paired t-test was used to determine if the mean difference was statistically different from zero.

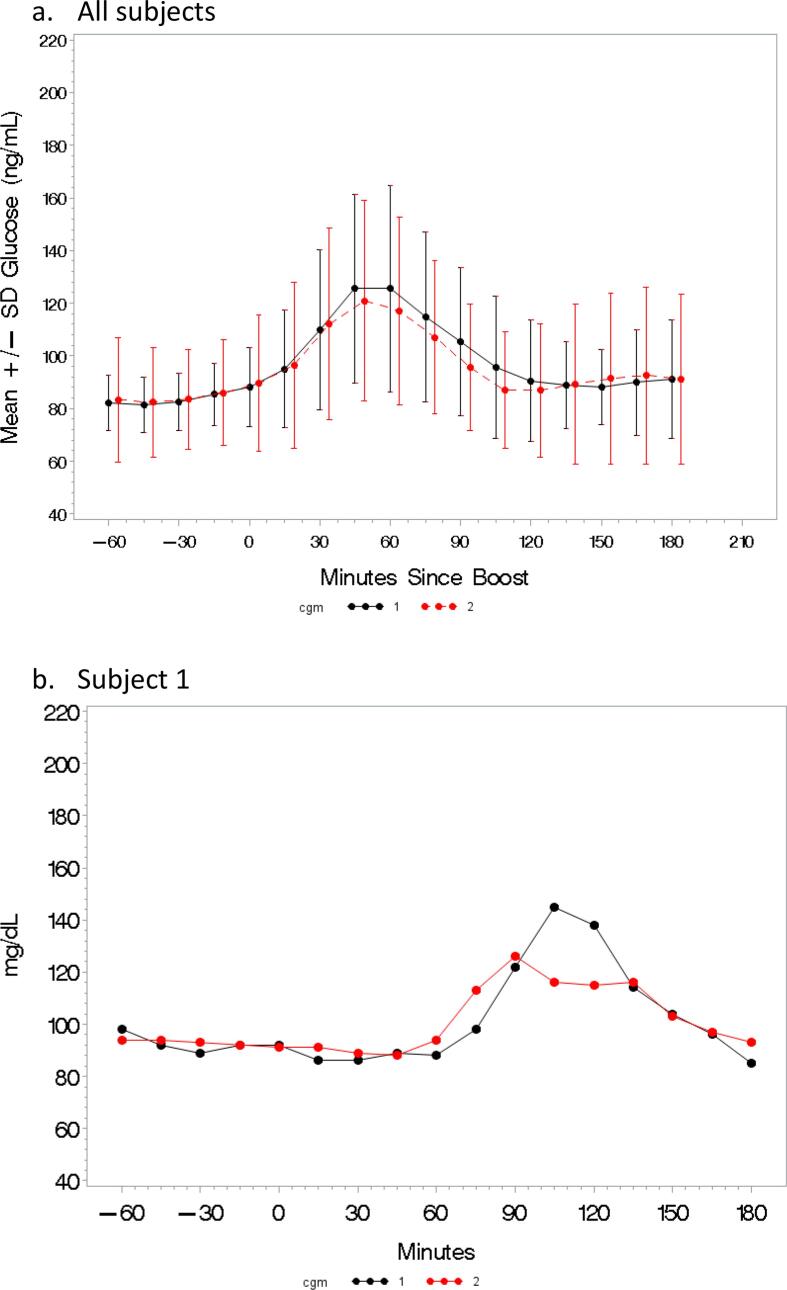

Analysis of glycemic excursions after Boost ingestion was performed for each CGM wear period by evaluating both 2-hour glucose and peak glucose as potentially useful endpoints. Baseline glucose was assigned based on the glucose value immediately preceding the Boost ingestion and two-hour glucose was 120 min after the baseline value. Peak glucose was the highest glucose within 3 h of Boost ingestion. The first and second Boost challenges were compared for agreement regarding the following thresholds: 2-hour glucose >200 mg/dL, 2-hour glucose >180 mg/dL, 2-hour glucose >140 mg/dL and peak glucose >200 mg/dL, peak glucose >180 mg/dL, and peak glucose >140 mg/dL. Thresholds were selected to explore potentially useful degrees of dysglycemia, as there are not validated glycemic cut-offs after MMTT. The mean (+/- SD) glucose was plotted for each time point for CGM1 and CGM2 (Fig. 2a). To further appreciate the intra-subject differences in glucose and timing of peak after boost, select subjects were graphed individually (Fig. 2b,c, and d). Subjects who failed to record the time of Boost ingestion were excluded from the analysis. Time of Boost ingestion was adjusted for CGM 1 for a single subject (subject 3) with CFRD who mis-recorded the time of Boost ingestion.

Fig. 2.

Graphical depiction of the time of peak glucose for CGM 1 (black) and CGM 2 (red) for each subject. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Results

Cohort characteristics

Of the twenty subjects who completed the study 14 were male and six were female. Age at placement of the first CGM device ranged from 14.9 to 51.2 years (median 25.5 years). Percent predicted FEV1 (ppFEV1) ranged from 38 to 123% (median 95%). Body mass index (BMI) for adult subjects ranged from 19.4-37.6 kg/m2 (median 25.5 kg/m2) and for pediatric subjects 31–96% (median 66 %le). All subjects had at least one copy of a severe loss of function CFTR variant (class 1 or 2) and 19/20 subjects were pancreatic exocrine insufficient. All subjects were diagnosed with CF in infancy or early childhood. Most subjects (19/20) were treated with CFTR modulator therapy, and all subjects were on stable modulator therapy for at least one year prior to the study with no change to modulator use between the CGM acquisitions. Three subjects exceeded the threshold for CFRD based on prior OGTT and one subject met criteria for CFRD based on HbA1C level. Seven subjects had an OGTT indicating impaired glucose tolerance and nine subjects had an OGTT indicating normal glucose tolerance. (TABLE 1) One subject (subject 2) whose prior OGTT showed CFRD had previously been treated with insulin in the past. The mean duration between completion of CGM 1 and placement of CGM 2 was 1.5 weeks with a range of 1 to 3 weeks. No patients had a pulmonary exacerbation between the CGM wear periods.

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics for subjects in the study. Body mass index (BMI), BMI percentile, and percent predicted FEV1 (FEV1) from the most recent in person clinic visit. Oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) results from within 5 years. OGTT results indicate cystic fibrosis related diabetes (CFRD) if the fasting glucose is ≥126 mg/dL or the two-hour glucose is ≥200 mg/dL. OGTT results indicate Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) if the two-hour glucose exceeds 140 mg/dL. OGTT indicates normal glucose tolerance (NGT) if the fasting glucose is < 100 mg/dL and two-hour glucose is < 140 mg/dL. Hemoglobin A1C (A1C) result is reported from within one year of CGM 1. Abbreviations: y (years), m (months), M (male), F (female), ETI (elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor), Iva (Ivacaftor).

| No. | Age (y) | Sex | BMI (kg/m2) |

FEV1 | Mutation 1 (class) | Mutation 2 (class) | Exocrine Status | A1C | OGTT | Time since OGTT | CFTR Mod and duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25.2 | M | 26.2 | 109 | F508del (2) | F508del (2) | PI | 4.9 | CFRD | 8 m | ETI 1y1m |

| 2 | 22.2 | M | 19.9 | 101 | F508del (2) | F508del (2) | PI | 5.2 | CFRD | 1 m | ETI 1y10m |

| 3 | 41.3 | M | 21.6 | 84 | F508del (2) | 1898 1G > A (1) | PI | 5.6 | CFRD | 2y9m | ETI 2y9m |

| 4 | 34.7 | M | 25.5 | 38 | F508del (2) | R1066C (2) | PI | 6.5 | n/a | n/a | ETI 1y2m |

| 5 | 29.4 | M | 25.7 | 94 | F508del (2) | F508del (2) | PI | 5.4 | IGT | 5 m | ETI 1y1m |

| 6 | 32.1 | F | 22.4 | 39 | F508del (2) | F508del (2) | PI | 5.2 | IGT | 3y | ETI 1y5m |

| 7 | 36.3 | M | 27.3 | 92 | F508del (2) | 621 + 1 -->G > T (1) | PI | 5.4 | IGT | 1y | ETI 1y5m |

| 8 | 16.5 | M | 23 74 %le |

97 | F508del (2) | F508del (2) | PI | 5.1 | IGT | 5 m | ETI 1y3m |

| 9 | 22.5 | F | 23.4 | 66 | F508del (2) | F508del (2) | PI | 5.3 | IGT | 3 m | ETI 1y11m |

| 10 | 25.7 | M | 27.7 | 89 | F508del (2) | N1303K (2) | PI | 5.8 | IGT | 1 m | ETI 1y10m |

| 11 | 21.1 | F | 19.4 | 80 | F508del (2) | 621 + 1G > T (1) | PI | 5.6 | IGT | 1y6m | ETI 2y1m |

| 12 | 14.9 | M | 21.4 66 %le |

97 | F508del (2) | 1717- 1G > A (1) | PI | 5.4 | NGT |

1 m | ETI 1y4m |

| 13 | 15.9 | M | 28.2 96 %le |

97 | R117H (4) | G542X (1) | PS | 5.2 | NGT | 2y | Iva 5y |

| 14 | 48.7 | F | 25.9 | 97 | F508del (2) | G551D (4) | PI | 5.3 | NGT | 5 m | ETI 1y5m |

| 15 | 31.2 | M | 32.5 | 98 | F508del (2) | E822X (1) | PI | 4.4 | NGT | 0 m | ETI 1y1m |

| 16 | 15.2 | M | 20.8 57 %le |

96 | F508del (2) | 1717––1 G > A (1) | PI | 5.2 | NGT | 7 m | ETI 1y5m |

| 17 | 31.3 | M | 19.6 | 75 | F508del (2) | G542X (1) | PI | 5.2 | NGT | 3y2m | None |

| 18 | 17 | F | 19 31 %le |

109 | F508del (2) | R347P (4) | PI | 5.5 | NGT | 3 m | ETI 1y8m |

| 19 | 51.2 | F | 37.6 | 44 | 3849 + 10kbC-> T (5) | 2184insA (1) | PI | 5.5 | NGT | 6 m | Iva 3y8m |

| 20 | 22.2 | M | 23.3 | 123 | F508del (2) | 1717 G1G > A (1) | PI | 5.3 | NGT | 4 m | ETI 1y6m |

Agreement by time dependent threshold

Average glucose, coefficient of variation (CoV), percent of time >140 mg/dL and percent of time >180 mg/dL for CGM 1 and CGM 2 for each subject is presented in TABLE 2. Average glucose for CGM 1 and CGM 2 showed no clinically meaningful difference in most cases, with the greatest difference seen in subject 19 with average glucose 89.1 mg/dL for CGM 1 vs. 105.1 mg/dL for CGM 2. CoV was also generally consistent between CGM 1 and CGM 2 for most subjects.

Table 2.

Average glucose, Coefficient of Variation (CoV), percent time >140 mg/dL (%t>140), and percent time >180 mg/dL (%t>180) for continuous glucose monitor acquisition 1 (CGM 1) and continuous glucose monitor acquisition 2 (CGM 2) for each subject. The rightward most three columns describe whether CGM 1 and CGM 2 agreed (Y) or did not agree (N) with regard to each threshold. (+) indicates that the subject exceeded the threshold on both CGMs; (−/+) and (+/−) indicate that the subject exceeded the threshold on one CGM and not on the other; (-) indicates that the subject did not exceed the threshold on either CGM. * indicates subjects who previously exceeded the OGTT or A1C criteria for diabetes.

| CGM 1 |

CGM 2 |

Agreement |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub ject |

Average glucose | CV glucose | % t>140 | % t>180 | Average glucose | CV glucose | % t>140 | % t>180 | % t>140 > 4.5% | % t>140 > 17.5% | % t>180 > 3.4% |

| 1* | 89.0 | 25.4 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 82.4 | 29.1 | 3.2 | 0.1 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 2* | 107.2 | 27.6 | 13.2 | 3.0 | 102.3 | 29.1 | 10.7 | 2.1 | Y (+) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 3* | 111.2 | 25.1 | 16.1 | 3.0 | 108.1 | 27.0 | 13.7 | 3.0 | Y (+) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 4* | 140.2 | 48.5 | 36.8 | 24.3 | 140.3 | 42.3 | 37.1 | 19.0 | Y (+) | Y (+) | Y (+) |

| 5 | 91.9 | 34.3 | 8.5 | 3.0 | 112.7 | 45.2 | 20.7 | 11.1 | Y (+) | N (−/+) | N (−/+) |

| 6 | 75.9 | 30.0 | 2.0 | 0.1 | 78.6 | 40.8 | 6.7 | 0.6 | N (−/+) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 7 | 101.0 | 26.1 | 6.5 | 3.0 | 104.1 | 24.7 | 7.6 | 2.3 | Y (+) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 8 | 92.3 | 26.6 | 5.6 | 0.9 | 85.4 | 26.6 | 4.0 | 0.5 | N (+/−) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 9 | 95.5 | 36.2 | 11.9 | 3.9 | 101.7 | 40.8 | 16.1 | 6.5 | Y (+) | Y (−) | Y (+) |

| 10 | 100.7 | 24.3 | 7.2 | 1.8 | 98.5 | 25.7 | 6.9 | 1.1 | Y (+) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 11 | 117.8 | 37.4 | 23.6 | 11.2 | 114.2 | 34.9 | 20.2 | 7.9 | Y (+) | Y (+) | Y (+) |

| 12 | 104.9 | 25.6 | 10.0 | 2.1 | 106.9 | 22.1 | 9.2 | 1.9 | Y (+) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 13 | 92.6 | 15.0 | 0.1 | 0 | 88.0 | 16.6 | 0.3 | 0 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 14 | 99.2 | 30.2 | 10.5 | 1.6 | 94.0 | 32.9 | 10.0 | 1.6 | Y (+) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 15 | 97.7 | 36.6 | 9.9 | 3.6 | 87.4 | 54.8 | 13.8 | 4.7 | Y (+) | Y (−) | Y (+) |

| 16 | 107.1 | 15.0 | 3.4 | 0.2 | 110.4 | 17.4 | 6.8 | 0.0 | N (−/+) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 17 | 88.3 | 29.2 | 6.6 | 0.9 | 98.1 | 24.8 | 6.9 | 1.3 | Y (+) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 18 | 92.0 | 21.3 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 98.9 | 22.4 | 5.5 | 0.5 | N (−/+) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 19 | 89.1 | 19.1 | 0.8 | 0 | 105.1 | 19.2 | 7.1 | 0.4 | N (−/+) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 20 | 110.2 | 19.3 | 10.6 | 0.8 | 97.7 | 24.5 | 6.6 | 1.0 | Y (+) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

TABLE 2 demonstrates whether there was agreement between CGM 1 and CGM 2 for the three published thresholds: percent time >140 mg/dL of ≥4.5% (t140 ≥4.5%); percent time >140 mg/dL of >17.5% (t140 > 17.5%); and percent time >180 mg/dL of >3.4% (t180 > 3.4%). The threshold t140 ≥4.5% showed the greatest discrepancy between CGM 1 and CGM 2 in our cohort. Five subjects (25%) had disagreement between CGM 1 and CGM 2, meaning one CGM exceeded the threshold, and one did not. Fifteen subjects (75%) showed agreement on this criterion, with 12 subjects exceeding the threshold on both CGMs, and only two subjects not exceeding the threshold on either CGM.

The threshold t140 > 17.5% showed high levels of agreement between CGM 1 and CGM 2. Only one subject did not exceed the threshold on CGM 1 and did on CGM 2; while 19 of 20 subjects (95%) showed agreement for this threshold between CGM 1 and CGM 2. Of note, only two subjects exceeded t140 > 17.5% on both CGMs; while 17 subjects did not exceed this threshold on either CGM.

The threshold t180 > 3.4% also showed high levels of agreement between CGM 1 and CGM 2, with only one subject (5%) having discordant results. Four subjects exceeded this threshold on CGM 1 and CGM 2; while 15 subjects did not exceed this threshold on either CGM 1 or CGM 2.

Glycemic averages for CGM 1 and CGM 2

The average glucose for CGM 1 across all subjects was 100.2 mg/dL (SD 13.6) and the average glucose for CGM 2 was 100.7 mg/dL (SD 13.7). The mean of the individual differences between CGM 1 and CGM 2 was 0.55 mg/dL (SD 8.43), which was not statistically different from zero, p = 0.77.

Results of mixed meal tolerance test

Seventeen subjects completed two MMTTs at home and the results are summarized in TABLE 3. Three subjects who did not record any time of Boost ingestion were not included in the analysis. Baseline glucose prior to Boost ingestion did not show clinically relevant differences for most subjects. Noteworthy exceptions include: subject 4, whose fasting glucose was 112 mg/dL on CGM 1 and 69 mg/dL on CGM2, subject 7, whose fasting glucose was 85 mg/dL on CGM 1 and 160 mg/dL on CGM 2, and subject 19 whose fasting glucose was 104 mg/dL on CGM 1 and 126 mg/dL on CGM 2. Food diaries were reviewed wholistically, and no major differences were noted between CGM 1 and CGM 2.

Table 3.

Results of Mixed Meal Tolerance Test as recorded on the Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM). CGM 1 is the first acquisition and CGM 2 is the second acquisition. Baseline glucose represents the CGM glucose value at or immediately before the time of boost ingestion. 2-hour glucose represents the CGM glucose value 2- hour after the baseline glucose. Peak glucose is the highest CGM glucose value during the 3-hour mixed meal tolerance test. 2-Hour Glucose Agreement and Peak Glucose Agreement demonstrate whether CGM 1 and CGM 2 agreed (Y) or did not agree (N) for each glycemic threshold. (+) indicates that CGM1 and CGM 2 agreed and did exceed the threshold; (−) indicates that CGM1 and CGM2 agreed and did not meet the threshold; For tests that did not agree, (+/−) and (−/+) indicate which test exceeded the threshold (CGM1/CGM2). * Indicates subjects who previously exceeded the OGTT or A1C criteria for diabetes.

| Sub ject |

Baseline glucose |

2 Hour glucose |

Peak glucose |

2 Hour Glucose Agreement |

Peak Glucose Agreement |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGM 1 | CGM 2 | CGM 1 | CGM 2 | CGM 1 | CGM 2 | >200 | >180 | >140 | >200 | >180 | >140 | |

| 1* | 92 | 91 | 138 | 115 | 145 | 126 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | N (+/−) |

| 2* | 108 | 104 | 85 | 99 | 177 | 178 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (+) |

| 3* | 98 | 98 | 69 | 58 | 151 | 213 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | N (−/+) | N (−/+) | Y (+) |

| 4* | 112 | 69 | 144 | 116 | 189 | 123 | Y (−) | Y (−) | N (+/−) | Y (−) | N (+/−) | N (+/−) |

| 5 | 72 | 89 | 64 | 129 | 96 | 197 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | N (−/+) | N (−/+) |

| 6 | 60 | 77 | 67 | 91 | 98 | 101 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 7 | 85 | 160 | 81 | 88 | 188* | 167 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | N (+/−) | Y (+) |

| 8 | 78 | 70 | 89 | 56 | 104 | 126 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 9 | 67 | 73 | 74 | 62 | 160 | 131 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | N (+/−) |

| 10 | 95 | 91 | 86 | 100 | 122 | 130 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 12 | 99 | 95 | 108 | 86 | 166* | 117 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | N (+/−) |

| 13 | 84 | 79 | 87 | 78 | 101 | 104 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 14 | 93 | 79 | 70 | 55 | 171 | 114 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | N (+/−) |

| 15 | 80 | 40 | 88 | 40 | 128 | 79 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 16 | 98 | 99 | 110 | 102 | 128 | 115 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) |

| 17 | 73 | 84 | 92 | 92 | 161 | 147 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (+) |

| 19 | 104 | 126 | 88 | 111 | 125 | 207 | Y (−) | Y (−) | Y (−) | N (−/+) | N (−/+) | N (−/+) |

Two-hour glucose after Boost

Nearly all the 2-hour glucose measurements after Boost agreed between CGM 1 and CGM 2; though, notably the thresholds for 2-hour glucose >200 mg/dL, >180 mg/dL or >140 mg/dL were rarely exceeded. Subject 4 had discordant results with 2 h glucose >140 mg/dL on CGM 1 and not on CGM 2.

Peak glucose after Boost

Disagreement between CGM 1 and CGM 2 was relatively common when considering the thresholds of peak glucose >200 mg/dL, >180 mg/dL, and >140 mg/dL. Peak glucose exceeded 200 mg/dL in two subjects [3], [19] and did not occur on both CGM acquisitions. Five subjects exceeded 180 mg/dL on one CGM, but this was not repeated on the second CGM in any subject. Four subjects exceeded 140 mg/dL on both CGM 1 and CGM 2, seven subjects exceeded 140 mg/dL on only one of the CGMs, and six subjects never exceeded 140 mg/dL. The three patients who had previously demonstrated CFRD on at least one OGTT (subjects 1, 2, 3) did not invariably exceed any threshold for peak glucose. The single subject who met criteria for CFRD by HbA1C (subject 4) did exceed each threshold.

Graphical representation of Boost responses

Fig. 1 demonstrates the mean and standard deviation of the glucose at each time-point for CGM 1 and CGM 2 for all subjects, in addition to the glycemic curves for subjects (1-3) who previously met criteria for CFRD by OGTT. Subjects 1 and 2 show very similar curves on CGM 1 and CGM 2 albeit with slightly altered peaks. Subject 3 demonstrated a blunted peak on CGM 2. Fig. 2 depicts the variability in the time to reach peak glucose between CGM 1 (red) and CGM 2 (black) for each subject.

Fig. 1.

Mean glucose (dot) and standard deviation (error bars) for all subjects for CGM 1 (black) and CGM 2 (red). (a) Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) tracings during OGTT assessments for three subjects whose previous non-study OGTT showed CFRD. CGM 1 (black) and CGM 2 (red) are super-imposed on each other and demonstrate similar glycemic curves. (b,c,d). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Discussion

The objectives of this study were to assess the reproducibility of at-home CGM acquisitions in non-insulin treated patients at risk for CFRD and assess the utility of an in-home MMTT to generate standardized glycemic data. As there are no universally accepted thresholds to define an abnormal CGM for CFRD screening, we assessed agreement between CGM 1 and CGM 2 on published thresholds. We found disagreement between CGM 1 and CGM 2 in 25% of patients using the 2010 Hameed threshold of t140 ≥4.5%, which was associated with poor weight gain in the previous year in children with CF [12]. We only found disagreement in 5% of patients using the more recently published Scully thresholds t140 > 17.5% and t180 > 3.4%, which are designed to predict a diagnosis of CFRD on a standard OGTT [15]. For the mixed meal tolerance test, we compared several peak glucose and 2-hour glucose thresholds. Two-hour glucose rarely exceeded 140 mg/dL, consistent with prior studies, thus, there was agreement between CGM 1 and CGM 2 for most subjects but limited ability to discriminate normal and abnormal results [22]. Peak glucose was much more variable between the two CGM acquisitions, though the three subjects with a history of abnormal OGTT did show similar glycemic curves, suggesting that an at-home mixed meal tolerance test could be useful if a clinically relevant threshold for a positive screen were defined.

Interest in the use of CGM as a possible alternative to the OGTT for CFRD screening has grown considerably since CGM was first validated for use in people with CF in 2003 and again in 2009 [16], [22]. Though glycemia tends to worsen over time, lack of reproducibility in year-over-year OGTT has undermined the confidence of some patients and clinicians [6], [7], [8]. Advocates argue that a CGM, gathering real-world data, may be more relevant and better able to predict clinically important hyperglycemia [11], [14].

Indeed, Hameed in 2010 studied 25 children with CGM and found that having BG > 140 mg/dL 4.5% of the time predicted decline in weight standard deviation with 89% sensitivity and 86% specificity [12]. Frost later demonstrated that targeting insulin therapy at adult pwCF who exceeded Hameed’s threshold of percent time >140 mg/dL 4.5% resulted in improved weight and FEV1 and Hameed and colleagues found improved weight and lung function in children with early dysglycemia, but these were not randomized controlled trials [13], [14]. Results from the CF-IDEA (Cystic Fibrosis- Insulin Deficiency, Early Action) trial, a randomized trial of early insulin therapy prior to the onset of diabetes, should be available soon. Notably, the Hameed threshold is intended to predict the most clinically relevant outcome in CFRD care, insulin remediable weight loss; but was developed prior to the availability of highly effective modulator therapy. In our study, we found that many patients exceeded Hameed's relatively low threshold, who were not otherwise underweight or meeting other criteria for CFRD. Several other studies have attempted to identify predictors of BMI and lung-function decline in pwCF, suggesting that peak glucose or number of excursions above 200 mg/dL may predict decline in pulmonary function, but not yet defining actionable cut-points [9], [23].

As previously referenced, Scully recently studied 77 adults with CF (31 with CFRD) and used ROC curves to suggest cut-offs with good sensitivity and specificity for predicting CFRD on OGTT. Percent time >140 mg/dL of >17.5% had 87% sensitivity and 95% specificity for CFRD diagnosed by OGTT. Percent time >180 mg/dL of >3.4% had 90% sensitivity and a 95% specificity. We chose to evaluate the reproducibility of these cutoffs in our patient population, as they provide a practical threshold above which further investigation for CFRD is merited. Importantly, these cutoffs predict abnormal OGTT, not decline in pulmonary function or BMI [15]. Our study found that relatively few patients exceeded the cutoffs suggested by Scully. Three subjects had t140 > 17.5% of the time on either CGM, one of whom had previously met criteria for CFRD by HbA1C. Four subjects in our study had t180 > 3.4% on either CGM, including the individual with elevated HbA1C. All but one subject had the same result with regard to Scully’s thresholds on both CGMs, suggesting that separate CGM acquisitions are relatively reproducible with regard to these thresholds. Notably, three subjects [1], [2], [3] with a history of CFRD by OGTT did not exceed the Scully threshold on either CGM, suggesting validation of these cutoffs in additional populations is needed.

Several studies have compared between group differences in repeated CGM acquisitions. In 2009, O’Riordan reported a mean difference between CGMs done one year apart of 16.2 mg/dL with a standard deviation of 42.8 mg/dL [16]. Prentice in 2020 evaluated three repeat CGM acquisitions in 11 youth < 10 years of age at baseline, 1 year and 2 years. They found similar group-wide averages at all time points, but high variability over time regarding the presence or absence of peak glucose >200 mg/dL [17]. As glycemic status is known to evolve in early childhood, these differences may reflect changes in the patient’s glycemic status rather than lack of reliability of the measurement. In a subset of 53 subjects from their original cohort, Sully reports lower average glucose (117 mg/dL vs 110 mg/dL) and lower time >140 mg/dL (20.9% vs. 17.4%) between the baseline and completion visit [15]. Importantly, all these studies compared group means for these outcomes and often had long time intervals between assessments. Mean glucose for the two CGMs were more similar in our study (100.2 mg/dL vs. 100.7 mg/dL), possibly due to the shorter interval between acquisitions. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to evaluate the reproducibility of separate CGM acquisitions regarding specific thresholds to define abnormality.

Though prior studies have examined the feasibility of in-home OGTT and found good acceptability by participants, ours is also the first study to explore CGM for glycemic screening solely in the home environment [24]. As virtual care for people with CF grows in popularity, remote monitoring has become more important. Application of the CGM at home was very feasible using a virtual meeting for CGM 1 placement. In-home use of the mixed meal tolerance test proved more challenging, as four participants had trouble documenting the time of Boost ingestion. While inability to closely monitor the timing of MMTT may prove a barrier to in-home standardized meal testing for some, overall, our study results suggest that repeat CGM acquisitions provide useful data and lends support to the stability of the data provided by at-home CGM acquisitions regarding t140 > 17.5% and t180 > 3.4%.

Our study has several limitations, first being the relatively small sample size and lack of enrichment with subjects who had more severe glycemia. This largely stems from the fact that most patients in our center with dysglycemia are started on insulin. Furthermore, as there are no established guidelines to define an abnormal CGM, we used published thresholds to define “abnormal” CGM and assess reproducibility. Additionally, as a fully at-home study we relied on the participant to fast on the MMTT day, record the time of Boost ingestion, and ensure no other food or drink for at least 3 h. Use of the MMTT, without the gold-standard OGTT, was performed due to high rates of hypoglycemia with the OGTT and safety concerns about performing OGTTs in the home environment, but is a limitation [25]. As there are no established thresholds for abnormal glycemic response to MMTT, we chose >140 mg/dL, >180 mg/dL, and >200 mg/dL, but these are not expected to correlate with the gold-standard OGTT due to lower glycemic load of the mixed meal test. The study is also limited by lack of data on subject activity levels during the CGM wear period.

In conclusion, we present an at-home study evaluating the reproducibility of consecutive CGM acquisitions and mixed meal tolerance testing. Overall, our data supports the reproducibility of CGM acquisitions with regards to the thresholds for abnormality published by Scully, but shows more variability for the Hameed thresholds. We found that at-home MMTT show similar glycemic curves, but utility is limited by lack of established thresholds to define an abnormal MMTT result. Future studies should evaluate the reproducibility of CGM acquisitions in larger populations enriched with higher rates of dysglycemia. This will hopefully provide the additional data to inform CGM thresholds for CFRD screening and clinical practice guidelines.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Katherine Kutney reports financial support was provided by Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.

Acknowledgements

Study was performed with support from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (KUTNEY19GEO) and data collection was performed with RedCap.

References

- 1.Moran A, Brunzell C, Cohen RC, Katz M, Marshall BC, Onady G, et al. Clinical care guidelines for cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: A position statement of the American Diabetes Association and a clinical practice guideline of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, endorsed by the Pediatric Endocrine Society. Diabetes Care [Internet]. 2010;33(12):2697–708. Available from: [PMID:21115772 DOI:10.2337/dc10-1768]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Moran A., Pekow P., Grover P., Zorn M., Slovis B., Pilewski J., et al. Insulin Therapy to Improve BMI in Cystic Fibrosis – Related Diabetes Without Fasting Hyperglycemia. Diabetes Care [Internet] 2009;32(10):1783. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0585. Available from: [PMID:19592632 DOI:10.2337/dc09-0585l] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohan K, Israel KL, Miller H, Grainger R, Ledson MJ, Walshaw MJ. Long-term effect of insulin treatment in cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. Vol. 76, Respiration. 2008. p. 181–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry. Bethesda, MD; 2019.

- 5.Walshaw M. Routine OGTT screening for CFRD - No thanks. J R Soc Med. 2009;102(1_suppl):40–44. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2009.s19009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheuing N., Holl R.W., Dockter G., Hermann J.M., Junge S., Koerner-Rettberg C., et al. High variability in oral glucose tolerance among 1,128 patients with cystic fibrosis: A multicenter screening study. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sterescu A.E., Rhodes B., Jackson R., Dupuis A., Hanna A., Wilson D.C., et al. Natural History of Glucose Intolerance in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis: Ten-Year Prospective Observation Program. J Pediatr. 2010;156(4):613–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reynaud Q., Rabilloud M., Roche S., Poupon-Bourdy S., Iwaz J., Nove-Josserand R., et al. Glucose trajectories in cystic fibrosis and their association with pulmonary function. J Cyst Fibros. 2018;17(3):400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan C.L., Vigers T., Pyle L., Zeitler P.S., Sagel S.D., Nadeau K.J. Continuous glucose monitoring abnormalities in cystic fibrosis youth correlate with pulmonary function decline. J Cyst Fibros. 2018;17(6):783–790. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan C.L., Hope E., Thurston J., Vigers T., Pyle L., Zeitler P.S., et al. Hemoglobin A 1c Accurately Predicts Continuous Glucose Monitoring-Derived Average Glucose in Youth and Young Adults With Cystic Fibrosis. Diabetes Care [Internet] 2018;41(7):1406–1413. doi: 10.2337/dc17-2419. http://care.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/doi/10.2337/dc17-2419 Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan C.L., Ode K.L., Granados A., Moheet A., Moran A., Hameed S. Continuous glucose monitoring in cystic fibrosis – A practical guide. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18:S25–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2019.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hameed S., Morton J.R., Jaffé A., Field P.I., Belessis Y., Yoong T., et al. Early glucose abnormalities in cystic fibrosis are preceded by poor weight gain. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):221–226. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hameed S., Morton J.R., Field P.I., Belessis Y., Yoong T., Katz T., et al. Once daily insulin detemir in cystic fibrosis with insulin deficiency. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(5):464–467. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.204636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frost F., Dyce P., Nazareth D., Malone V., Walshaw M.J. Continuous glucose monitoring guided insulin therapy is associated with improved clinical outcomes in cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. J Cyst Fibros. 2018;17(6):798–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scully KJ, Sherwood JS, Martin K, Ruazol M, Marchetti P, Larkin M, et al. Continuous Glucose Monitoring and HbA1c in Cystic Fibrosis: Clinical Correlations and Implications for CFRD Diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2022 Apr 1;107(4):E1444–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.O'Riordan S.M.P., Hindmarsh P., Hill N.R., Matthews D.R., George S., Greally P., et al. Validation of continuous glucose monitoring in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis: A prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(6):1020–1022. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prentice B.J., Ooi C.Y., Verge C.F., Hameed S., Widger J. Glucose abnormalities detected by continuous glucose monitoring are common in young children with Cystic Fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2020;19(5):700–703. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2020.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edge J., Acerini C., Campbell F., Hamilton-Shield J., Moudiotis C., Rahman S., et al. An alternative sensor-based method for glucose monitoring in children and young people with diabetes. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102(6):543–549. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bailey T., Bode B.W., Christiansen M.P., Klaff L.J., Alva S. The Performance and Usability of a Factory-Calibrated Flash Glucose Monitoring System. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17(11):787–794. doi: 10.1089/dia.2014.0378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sato T., Oshima H., Nakata K., Kimura Y., Yano T., Furuhashi M., et al. Accuracy of flash glucose monitoring in insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig. 2019;10(3):846–850. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenbaum C.J., Mandrup-Poulsen T., McGee P.F., Battelino T., Haastert B., Ludvigsson J., et al. Mixed-meal tolerance test versus glucagon stimulation test for the assessment of β-cell function in therapeutic trials in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(10):1966–1971. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dobson L., Sheldon C.D., Hattersley A.T. Dobson 2003 Validation of CGM in CF. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(6):1940–1941. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1940-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor-Cousar J., Janssen J.S., Wilson A., Clair C.G.S., Pickard K.M., Jones M.C., et al. Glucose > 200 mg / dL during Continuous Glucose Monitoring Identifies Adult Patients at Risk for Development of Cystic Fibrosis Related Diabetes. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/1527932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumarasamy M., Peters C., Drew S., Gordon H., Dawson C., Suri R., et al. G559 Acceptability of a home-use oral glucose tolerance test kit for screening cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. In. BMJ. 2019:A226. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hicks R., Marks B.E., Oxman R., Moheet A. Spontaneous and iatrogenic hypoglycemia in cystic fibrosis. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2021;26:100267. doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2021.100267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]