Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to develop the nurses' Work Values Scale (WVS) to determine how important certain values are for nurses and to psychometrically test the scale.

Design

Instrument development and validation study.

Method

A two‐phase scale development process comprising item generation, scale improvement and psychometric property evaluation was used. In the first phase, scale items were identified. In the second phase, item and exploratory factor analyses were performed in Study 1, and confirmatory factor analysis, validity verification and reliability verification of the nurses' WVS were performed in Study 2.

Results

As a result of the analysis, a scale of 30 items with four subdomains was developed. In convergent validity and reliability verification, it was shown that the nurses' WVS has acceptable validity and reliability.

No Patient or Public Contribution

Patients or members of the public were not involved in this study.

Keywords: instrument development, nurses, nursing, work values, Work Values Scale

1. INTRODUCTION

The importance of measuring nurses' work values has been recognized over the past two decades. Nurses' work values are defined as enduring beliefs they want recognized through their work, favourable conditions and results they want to achieve, and the principles and standards that place importance on the work and guide their attitudes, judgements and behaviours (Hara & Asakura, 2021). To date, work values have been treated as a key concept in person‐environment fit theory (Van Vianen, 2018) and self‐determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017) and their relationships with various variables have been clarified. For example, it has become clear that nurses' work values affect psychosocial variables such as burnout (Saito et al., 2018) and employee satisfaction (Wang et al., 2019). However, few studies have adequately examined the concept of work values and scales that can be used to measure nurses' work values. Moreover, although past studies have used scales, the concept of nurses' work values remains ambiguous. Additionally, as different occupations emphasize varying sets of work values (Basinska & Dåderman, 2019), a scale that can adequately measure nurses' work values is needed.

In this study, the nurses' Work Values Scale (WVS) was designed based on the conceptual analysis of nurses' work values in a systematic review (Hara & Asakura, 2021), the four‐factor structure proposed by Ros et al. (1999), and the basic human value theory of Schwartz and Cieciuch (2022). In other words, this study developed a self‐report scale for nurses to evaluate their work values based on a conceptual analysis and theoretical foundation. The nurses' WVS will enable adequate measurement of the set of values on which nurses place importance. Furthermore, this scale can potentially measure nurses' work values with greater precision than previously used scales.

2. BACKGROUND

Work values are specific values about work (Ros et al., 1999) that guide various aspects of an individual's life. Work values include multiple values that an individual emphasizes or targets, such as values of self‐growth and salary (Hara & Asakura, 2021). It has become clear that values emphasized and prioritized by individuals differ (Schwartz & Cieciuch, 2022). Measuring work values leads to a numerical visualization of how an individual wants to work and what they are aiming for. It can be a guideline for individuals, and knowing others' work values leads to mutual respect.

Elucidating the function of work values and their impact on psychosocial variables helps nurses continue their work while ensuring their own well‐being. However, the scales used in previous studies may not be able to appropriately measure nurses' work values. For example, in Chen et al.'s (2016) study, job satisfaction is included as a subscale of work values. The definition of job satisfaction focuses on the global affective responses or attitudes that individuals have towards their jobs (Dilig‐Ruiz et al., 2018). In other words, job satisfaction should be treated as a result of work values, not included in work values, because job satisfaction is expressed as an attitude; for this reason, the scale used in the study conducted by Chen et al. (2016) cannot appropriately measure work values. Furthermore, the brief version of WVS developed by Eguchi and Tokaji (2009) is available in Japanese but does not include the values for job security. This is a factor that nurses have attached importance to in previous studies (Hampton & Welsh, 2019). Therefore, the content validity of the scale is low. It is important to use a scale that can adequately measure nurses' work values, as the use of inadequate scales can lead to erroneous results.

Since it is clear that emphasized work values differ depending on the group to which the individual belongs, such as occupation (Basinska & Dåderman, 2019), the scale that measures the work values of a group should include the values emphasized by that group. Therefore, the values that the target group attaches great importance to should be included items. For example, a scale that includes altruistic values and salary and employment security values (Hara & Asakura, 2021) that nurses consider important, as shown in previous studies, is more suitable.

In this study, we developed a scale that can appropriately measure nurses' work values. The scale was created in accordance with the psychological measurement scale development method (DeVellis, 2016), and a reliable and valid scale was developed. In this way, by using theoretical and empirical procedures to develop a scientifically reliable and valid scale, it is possible to properly measure the work values of nurses. The development of this scale is expected to further elucidate the relationship between nurses' attitudes, behaviours and outcome variables, which can contribute to the happier and more fulfilling work life of nurses.

3. THE STUDY

3.1. Aims

This study aimed to develop the nurses' WVS to determine how important certain values are for nurses and to validate the scale psychometrically.

3.2. Design

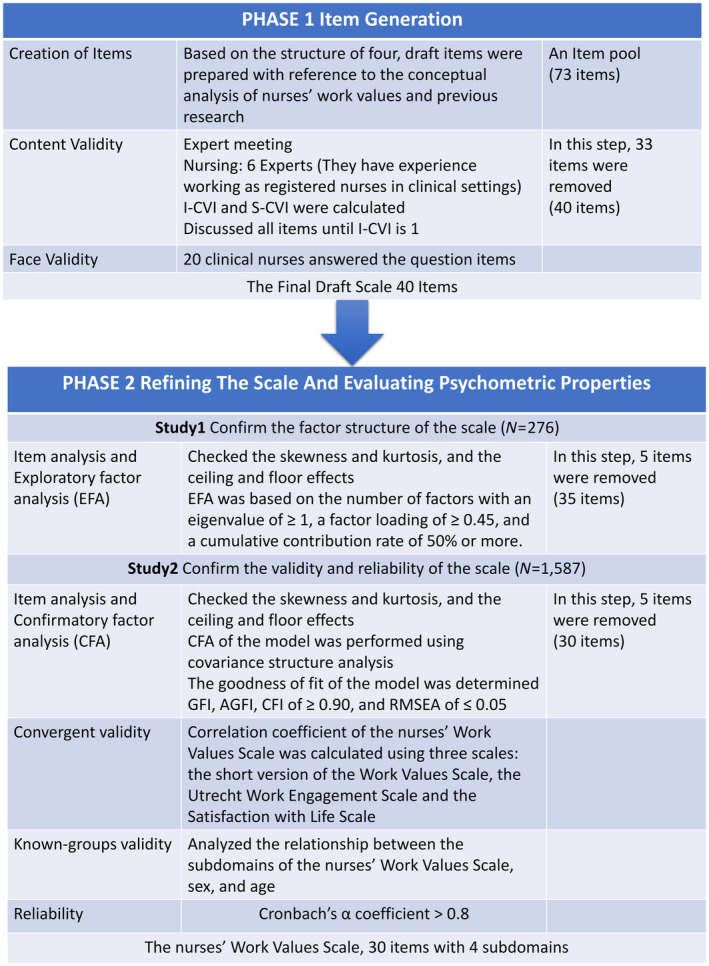

The scale development process consisted of two phases, shown in Figure 1 (DeVellis, 2016). In the first phase, scale items were identified and in the second phase, Studies 1 and 2 were conducted with two different samples to collect quantitative data for scale validation. In Study 1, item analysis and exploratory factor analysis (EFA) were performed; in Study 2, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of nurses' WVS, validity verification and reliability verification were performed.

FIGURE 1.

Phases in the development of the nurses' Work Values Scale.

Regarding the validity verification in Study 2, with reference to the COSMIN study design checklist (Mokkink et al., 2019), we determined that the nurses' WVS does not have a gold‐standard scale. Therefore, we decided to verify the convergent validity using similar scales along with the known‐groups validity. The COSMIN study design checklist recommends setting hypotheses at the study design stage (Mokkink et al., 2019). Table 1 shows the hypotheses and their basis to verify convergence validity, and Table 2 shows the hypotheses and their basis to verify the known group validity.

TABLE 1.

Hypotheses for testing convergent validity.

| Scale used | Basis for hypothesis | Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|

| The short version of the Work Vales Scale (Eguchi & Tokaji, 2009) | The short version of the WVS is based on Super's (1957) theory. Although the short version of the WVS and nurses' WVS are based on different theories, we hypothesized that there is a positive correlation between the corresponding subdomains in view of each theory and question item |

There is a positive correlation between the corresponding subdomains, and the corresponding subdomains of both scales are as follows: (1) internal value‐oriented and intrinsic work values, (2) external value‐oriented ‘economic reward’ and extrinsic work values, (3) altruistic value‐oriented and social work values and (4) external value‐oriented ‘social evaluation’ and prestige work values ※Internal value‐oriented includes ‘self‐growth’ and ‘feeling of accomplishment.’ Altruistic value‐oriented includes ‘contribution to society’, ‘contribution to colleagues’ and ‘contribution to affiliated organizations’ |

| The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (Shimazu et al., 2008) | Previous studies have clarified that work values are related to work engagement (Basinska & Dåderman, 2019; Saito et al., 2018). | In previous studies, (1) intrinsic work values are significantly positively associated with work engagement. (2) Extrinsic work values are not significantly associated and (3) social work values are significantly positively associated with intrinsic work values. Moreover, (4) prestige work values are significantly positively associated. Therefore, we hypothesized that similar results would be obtained in this study |

| The Satisfaction with Life Scale (Oishi, 2009) | Previous studies have shown that prioritizing intrinsic work values over extrinsic work values has a positive effect on life satisfaction (Vansteenkiste et al., 2007). In this study, the hypothesis of using social work values and prestige work values in addition to the two factors was proposed using the self‐determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017) | (1) Nurses who place importance on intrinsic work values are intrinsically motivated for work and have a high degree of satisfaction in life (there is a significant positive correlation). (2) Nurses who place importance on extrinsic work values have not acquired intrinsic motivation and are engaged in work for extrinsic purposes, and thus, their life satisfaction is low (there is a significant negative correlation). (3) As social work values were considered part of intrinsic work values in previous studies, a significant positive correlation is expected. (4) As prestige work values were considered part of extrinsic work values in previous studies, a significant negative correlation is expected |

TABLE 2.

Hypotheses for testing known group validity.

| Basis for hypothesis | Hypothesis |

|---|---|

| Previous studies have shown that men place more emphasis on status and power (Milfont et al., 2016) | (1) Men have significantly higher mean prestige work values |

| Previous studies have shown that women generally have higher social work values (Milfont et al., 2016) | (2) Women have significantly higher mean social work values |

| Previous studies have shown that the probability of selecting good pay and good hours as important decreases with age (Hajdu & Sik, 2018) | (3) There is a significant negative correlation between age and extrinsic work values |

Few studies have compared the subdomains of work values according to personal attributes. Therefore, the hypothesis regarding intrinsic work values could not be proposed.

4. METHODS

4.1. First phase: Item generation

First, a draft of 73 items was prepared with reference to the conceptual analysis of nurses' work values (Hara & Asakura, 2021) and previous research. These theoretical underpinnings were also based on the four‐factor structure proposed by Ros et al. (1999) and Schwartz and Cieciuch (2022) basic human values theory. Following this, at expert meetings of three researchers with doctoral degrees and three with master's degrees, using the draft of 73 items, we examined and carefully selected the question items. Six expert meetings were held between December 2019 and April 2020. In this study, the content validity was examined using the content validity index (Yusoff, 2019). The meeting members were asked to rate the instrument items in terms of clarity and relevancy to the construct underlying the study, according to the theoretical definitions of the four subdomains, on a 4‐point scale. These scores were presented at the meetings to calculate both the Content Validity Index Item (I‐CVI) and Scale (S‐CVI) levels. During the discussions held at the meetings, the items were corrected along with the scoring. Therefore, the scoring of items was not completed in all meetings and I‐CVI and S‐CVI were not strictly calculated. Generally, the I‐CVI was calculated by dividing the number of experts who scored each item 3 or 4 by the total number of experts (Yusoff, 2019). The S‐CVI was calculated by dividing I‐CVI by the total number of items; thus, if the I‐CVI is 1 for all items, then the S‐CVI is also 1. In this study, all items were discussed until all experts agreed (i.e., I‐CVI and S‐CVI = 1). In other words, after repeated discussions, we revised the question items to expressions that are easy for clinical nurses to understand, and deleted items with unclear questions and duplicate questions. In addition, as a verification of face validity, we asked 20 clinical nurses to answer the question items and confirmed whether there were any expressions that they could not understand. Finally, a scale draft consisting of 40 items was created.

4.2. Second phase: Study 1

4.2.1. Participants and procedure

The larger the sample size, the better the results of performing EFA. However, a prior study reported that there are no strict rules (Costello & Osborne, 2005). The COVID‐19 pandemic had excessively burdened the medical system at the time of Study 1; therefore, we confirmed the minimum sample size for performing EFA. The minimum sample size was 200, and the ratio of participants to items was 5:1 (De Winter et al., 2009). As the number of items in Study 1 was 40, the required sample size was at least 200. Considering the influence of COVID‐19, we expected the response rate of hospital nurses to be 70% and distributed 300 questionnaires. Additionally, to minimize the burden of the survey on medical institutions and nurses, the survey was conducted at one facility selected from among general hospitals in the Tohoku region of Japan through convenience sampling.

Data were collected from May to June 2020 through a self‐administered questionnaire retention method. We prepared 300 copies of a set of documents written in Japanese, including the questionnaire and a request for cooperation/informed consent declaration, and mailed them to the target facility along with 300 return envelopes. The deputy nursing director of the facility distributed the questionnaire to all 298 registered nurses working at the facility. After answering the questionnaire, nurses put them in the return envelope, sealed them and anonymously placed them in the collection envelope prepared for each department. The deputy nursing director of the facility compiled the collection envelope prepared for each department and mailed it to the investigators. The inclusion criterion for Study 1 was all the registered nurses working at the facility, excluding nurses who did not wish to participate or were on parental/sick leave.

4.2.2. Measures

In addition to the 40‐item version of nurses' WVS, we asked about their basic attributes such as age, sex, years of experience as a nurse, position, number of night shifts per month, educational background, marital status and number of children.

4.2.3. Data analysis

After calculating descriptive statistics for basic attributes, we checked the skewness and kurtosis, assessed ceiling and floor effects as item analysis of the scale draft, and performed item‐total (I–T) correlation analysis using the total score of all items. The criteria for normality confirmation were skewness and kurtosis >|1| (Orcan, 2020), and the criterion for I–T correlation was less than 0.2. The criteria for the ceiling and floor effects were that the mean–SD was less than 1.0 and the mean + SD was greater than 5.0, as reported in previous studies (Konda et al., 2018), because the answers to the questions were rated on a 5‐point Likert scale. Bartlett's test of sphericity was performed for the suitability of factor analysis, and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value was calculated for sample validity (Shrestha, 2021). Following this, an EFA (principal factor method, Promax rotation) was performed to carefully select the question items and confirm whether a factor structure equivalent to the assumed construct could be obtained. The EFA was performed based on the number of factors with an eigenvalue of ≥1, a factor loading of ≥0.45, and a cumulative contribution rate of 50% or more. In addition, to examine the internal consistency, Cronbach's α coefficient (α coefficient) of the subdomain was calculated. The standard for the α coefficient was 0.7 or higher (Shrestha, 2021). IBM SPSS ver. 26.0 for Windows (IBM Corporation) was used as the statistical analysis software; all the tests were performed using the two‐sided test, and the significance level was set to 5%.

4.3. Second phase: Study 2

4.3.1. Participants and procedure

The number of samples collected in Study 2 was 2600. Assuming that the variables used in the survey were compared between any two groups, the sample size was calculated using the unpaired t‐test. Using the power analysis software G * Power 3.1.9.4, the total sample size was 1302 when calculated with an α error of 0.05, detection power of 0.95 and an effect size of 0.2. Assuming that the collection rate by the mail method is 50%, the required number of samples will be 2604. Therefore, to round it off, we set the number of samples to be collected in this survey to 2600.

While conducting Study 2, it was considered that the hospital would be burdened if the number of participants per facility was large due to the ongoing COVID‐19 epidemic. Therefore, we decided to target 50 nurses in one facility and conducted a random sampling of 52 facilities from hospitals with 100 beds or more in six prefectures in the Tohoku region of Japan. We first requested a survey of 52 facilities and confirmed the facility consent rate. In September 2020, a set of documents containing explanatory documents, requests, consent forms and return envelopes were mailed to nursing managers at 52 facilities. Since there were replies from 23 facilities and the facility consent rate was 44%, random sampling was performed with 80 facilities for the second time, and a survey cooperation request was made to the nursing manager. The second time, there were replies from 37 facilities, and the response rate was 46%. Since more than 52 facilities responded, we notified the nursing managers of eight facilities that they would not be included in this survey. In addition, the participants of Studies 1 and 2 did not overlap.

Data were collected between October and December 2020. We mailed 50 copies of a set of documents in Japanese containing explanatory documents, survey forms and return envelopes to 52 target facilities. Informed consent was obtained in the survey cooperation request. The nurses were given a set of documents by the appointed nurse survey manager. After answering the questionnaires, the nurses placed them in the return envelopes, sealed them and posted them via mail anonymously. Following the inclusion criterion, 50 registered nurses nominated by the appointed nurse survey manager at each facility were recruited. However, as with Study 1, nurses who did not wish to participate or those on parental/sick leave were excluded.

4.3.2. Measures

Nurses' WVS

The 35 items of the nurses' WVS revised in Study 1 were used.

Demographics

We asked about respondents' basic attributes such as age, sex, years of experience as a nurse, position, number of night shifts per month, educational background, marital status and number of children.

The short version of the WVS

To verify the convergent validity of this Japanese scale, measurements were made using the short (21‐item) version of the WVS (Eguchi & Tokaji, 2009). It has three higher‐level factors, ‘internal value‐oriented’, ‘external value‐oriented’ and ‘altruistic value‐oriented’. Furthermore, it has seven subfactors, with three items for each subfactor. These were measured on a 6‐point Likert scale, where 1 = not important at all and 6 = very important. The higher the score, the more important it is for the worker. Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics and Cronbach's α coefficients in this study.

TABLE 3.

Descriptive statistics of the scales and Cronbach's α coefficient (N = 1587).

| Scale | Number of items | Range | Mean | SD | Cronbach's α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The short version of the Work Values Scale | |||||

| Internal value‐oriented | |||||

| Self‐growth | 3 | 3–18 | 12.7 | 2.9 | 0.93 |

| Sense of accomplishment | 3 | 3–18 | 10.2 | 3.2 | 0.93 |

| Altruistic value‐oriented | |||||

| Contribution to colleagues | 3 | 3–18 | 11.5 | 3.1 | 0.94 |

| Contribution to the organization to which they belong | 3 | 3–18 | 8.9 | 3.5 | 0.95 |

| Contribution to society | 3 | 3–18 | 11.1 | 3.4 | 0.94 |

| External value‐oriented | |||||

| Economic reward | 3 | 3–18 | 14.2 | 2.7 | 0.91 |

| Social evaluation | 3 | 3–18 | 8.0 | 3.0 | 0.91 |

| Utrecht Work Engagement Scale | 9 | 0–54 | 22.4 | 9.1 | 0.93 |

| Satisfaction with Life Scale | 5 | 5–35 | 20.3 | 5.6 | 0.90 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Work engagement

We used the Japanese translation by Shimazu et al. (2008) of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) developed by Schaufeli et al. (2002) produced for the verification of the convergent validity of the scale. It includes items such as ‘I am enthusiastic about my work’ and ‘I feel proud of my work’ measured on a 7‐point Likert scale where 0 = I have never felt to 6 = I always feel. The higher the score, the more vigorous and actively involved the nurses are in their work. Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics and Cronbach's α coefficients in this study.

Satisfaction with Life Scale

To verify the convergent validity of the scale, the SWLS developed by Diener et al. (1985) and translated into Japanese by Oishi (2009) was used. The SWLS is a five‐item scale that includes items such as ‘in most respects my life is close to my ideals’ and ‘I am satisfied with my life’. It is measured on a 7‐point Likert scale where 1 = Not applicable at all and 7 = Very applicable. The higher the score, the higher the satisfaction with life. Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics and Cronbach's α coefficients in this study.

4.3.3. Data analysis

For the statistical analysis, IBM SPSS ver. 26.0 for Windows and IBM SPSS AMOS ver. 26.0 were used, and all the tests were performed using two‐sided tests, with a significance level of 5%.

Participant characteristics and item analysis

After descriptive statistics were calculated for the basic attributes of the participants, the skewness and kurtosis were confirmed, the ceiling and floor effects were confirmed through item analysis, and the I–T correlation was calculated.

Confirmatory factor analysis

The four‐factor model obtained in Study 1 was fitted, and a CFA of the model was performed using covariance structure analysis. The goodness of fit of the model was determined using the following indicators: chi‐squared value, the goodness‐of‐fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness‐of‐fit index (AGFI), comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The evaluation criteria for the model were GFI, AGFI, CFI of ≥0.90, and RMSEA of ≤0.05 (Byrne, 2016). If the model's goodness‐of‐fit did not meet the criteria, we decided to reconsider the contents of the item. When we determined that deleting an item would reduce the validity of the scale's content, we decided to set the covariance between the error variables. It has been recommended to set the covariance between the error variables while confirming it is theoretically acceptable; for example, this can be done by ensuring that the contents of the items are similar (Byrne, 2016). Therefore, we decided to follow the rules of setting the covariance between the error variables in descending order of modification indices and limiting the items that set the covariance between the error variables to those that were evaluated as similar during item generation.

Verification of convergent validity

As mentioned previously, we verified convergent validity using three scales: the short version of the WVS, the UWES and the SWLS. The Pearson product–moment correlation coefficient of the subdomain score of each scale and the subdomain score of nurses' work values were calculated. Since psychological data such as values and attitudes are used in this study, the strength of the correlation coefficient was judged as follows (Akoglu, 2018): <0.1 was set to negligible, as it may be statistically significant when the data set is large (Schober et al., 2018); a weak correlation was denoted by values between 0.1 and 0.3; a moderate correlation was indicated by ≥0.3 and <0.5; and a value of ≥0.5 indicated a strong correlation.

Verification of known‐groups validity

To verify the known‐groups validity, we analysed the relationship between the subdomains of the nurses' WVS, sex and age. Regarding the analysis method, for sex, the total score of the subdomains of the nurses' WVS was used, and the analysis was performed using the unpaired t‐test. The relationship between the subdomains of the nurses' WVS and age was analysed using Pearson's product–moment correlation coefficient.

Reliability verification

The α coefficient of the subdomain was calculated to examine the internal consistency of the scale.

Scale score distribution

Descriptive statistics were calculated to confirm the distribution of subdomain scores of nurses' WVS.

4.4. Ethical considerations

The ethics committee of the institution to which the researcher belongs granted approval for this study. Participants were assured of their confidentiality and anonymity during the research and publication process. Previous their participation, we informed the participants of the purpose and design of the study and mentioned that participation was voluntary. Returned questionnaires were deemed to represent the consent to participate.

5. RESULTS

5.1. First phase: Item generation

Six expert meetings were held to revise and formulate a draft comprising 73 items, which were finally reduced to 40 items. The process of correction and selection of the 40 items is provided as supporting information in an Excel file.

5.2. Second phase: Study 1

5.2.1. Participant characteristics

A total of 298 questionnaires were distributed, and 282 were collected (recovery rate: 94.6%). Six questionnaires were excluded from the analysis due to missing answers, and 276 were used for the final analysis (valid response rate: 92.6%). Details of personal attributes are listed in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Participants' general attributes in Study 1 (N = 276) and Study 2 (N = 1587).

| Participants' attributes | Study 1 | Study 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Mean (SD) | N (%) | Mean (SD) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 262 (94.9) | 1464 (92.2) | ||

| Male | 14 (5.1) | 123 (7.8) | ||

| Age (years) | 40.6 (9.8) | 40.7 (10.3) | ||

| Years of nursing experience (SD) | 17.6 (9.6) | 17.9 (10.1) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 164 (59.4) | 1013 (63.9) | ||

| Single | 103 (37.3) | 529 (33.4) | ||

| Other (divorce, bereavement, etc.) | 9 (3.3) | 44 (2.8) | ||

| Number of children | ||||

| One or more | 142 (51.4) | 955 (60.3) | ||

| None | 133 (48.2) | 630 (39.7) | ||

| Educational background | ||||

| Baccalaureate program (4‐year program in nursing) or master's program in nursing | 37 (13.4) | 150 (9.5) | ||

| Vocational school or junior college for registered nurses | 239 (86.6) | 1435 (90.5) | ||

| Employment conditions | ||||

| Regular employees | 272 (98.6) | 1535 (96.7) | ||

| Non‐regular employees | 4 (1.4) | 52 (3.3) | ||

| Position | ||||

| Director, Deputy Director, Head Nurse, or Assistant Head Nurse | 45 (16.3) | 504 (31.8) | ||

| Regular nurse | 231 (83.7) | 1083 (68.2) | ||

| Number of night shifts per month | ||||

| One or more | 195 (70.7) | 1291 (81.3) | ||

| None | 81 (29.3) | 296 (18.7) | ||

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

5.2.2. Item analysis

There were no items that exceeded the criteria for skewness, kurtosis, I–T correlation or floor effect. Item 16 exceeded the standard for the ceiling effect. We discussed whether to exclude item 16 (Being able to afford the holiday one wants) and decided to review the item in Study 2. In Study 1, item 16 was also used for the EFA.

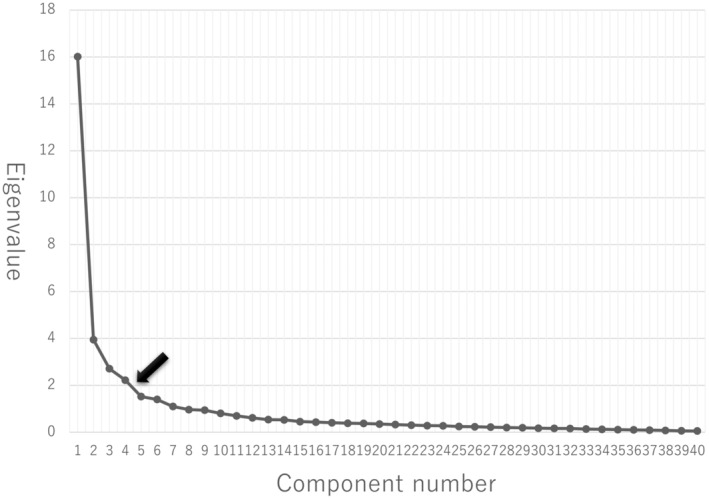

5.2.3. Exploratory factor analysis

The sample validity of KMO was 0.926, and Bartlett's test of sphericity resulted in p < 0.001, confirming the sample validity and suitability of the factor analysis. Further, EFA was performed. Seven factors had initial eigenvalues of ≥1, but there was also a difference in the eigenvalues between the fourth and fifth factors (Figure 2). Furthermore, since 62.2% of the total variance of 40 items was explained by four factors, the scree plot standard was adopted when determining the number of factors, and the four factors assumed in the conceptual analysis were adopted. Factor analysis was performed using the Principal Factor Method, Promax rotation and four‐factor fixation using 40 items. In total, three items (items 6, 20 and 34) with a factor loading of less than 0.45 and two items (items 19 and 37) with a factor loading of ≥0.3 for multiple factors were excluded. The final version of Study 1 had 35 items with four factors. The factor names used are similar to that of Ros et al. (1999): intrinsic work values, extrinsic work values, social work values and prestige work values. The results of the EFA are presented in Table 5.

FIGURE 2.

Scree plot for the exploratory factor analysis (EFA).

TABLE 5.

Results of the exploratory factor analysis.

| No. | Items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social work values | |||||

| 21 | Contributing to society by working as a nurse | 0.99 | −0.16 | −0.02 | −0.07 |

| 22 | Helping people around the world through nursing | 0.96 | −0.10 | 0.01 | −0.08 |

| 23 | Helping as many people as possible through nursing | 0.89 | 0.03 | −0.09 | −0.01 |

| 25 | Helping the staff by working in the same workplace | 0.81 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.04 |

| 26 | Contributing to the medical team as a nurse | 0.81 | 0.12 | −0.01 | −0.04 |

| 29 | Meeting people through work | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| 24 | Helping patients by providing nursing care | 0.67 | 0.15 | −0.04 | 0.06 |

| 30 | Feeling connected with people by working | 0.66 | 0.00 | 0.13 | −0.01 |

| 27 | Supporting the training of junior nurses | 0.64 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| 28 | Build good relationships with the staff working in the same workplace | 0.56 | 0.14 | −0.01 | 0.12 |

| Intrinsic work values | |||||

| 4 | To enhance nursing practice skills | −0.11 | 0.98 | −0.06 | 0.00 |

| 3 | To grow as a nurse | −0.01 | 0.89 | 0.00 | −0.06 |

| 9 | Develop expertise as a nurse | −0.01 | 0.83 | 0.06 | 0.00 |

| 2 | Seeking better ways of nursing care | −0.05 | 0.80 | −0.03 | −0.05 |

| 10 | Learning new knowledge and skills | 0.05 | 0.80 | −0.02 | −0.05 |

| 5 | To grow as a person | 0.10 | 0.67 | 0.04 | −0.01 |

| 1 | Devise your own way of working | −0.01 | 0.65 | −0.13 | 0.04 |

| 8 | Pursue things that interest you | 0.09 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| 7 | Caring for various patients to enhance one's experience as a nurse | 0.14 | 0.56 | 0.06 | −0.08 |

| Prestige work values | |||||

| 31 | To obtain a managerial position such as Head Nurse | −0.08 | −0.07 | 0.91 | −0.13 |

| 32 | To get promoted | −0.09 | −0.10 | 0.88 | −0.11 |

| 33 | Be an influencer in the workplace | 0.05 | −0.11 | 0.86 | −0.12 |

| 35 | Being highly praised by the staff working in the same workplace | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.64 | 0.06 |

| 40 | To be respected by junior nurses | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.63 | 0.08 |

| 38 | Being respected as a nurse | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.59 | 0.03 |

| 36 | Recognition of practical nursing skills by superiors | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.48 | 0.06 |

| 39 | Get high marks from patients | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.46 | 0.09 |

| Extrinsic work values | |||||

| 12 | Get a higher salary | −0.24 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.89 |

| 11 | Get a good living salary | −0.07 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.82 |

| 13 | Get an above‐average salary | −0.15 | −0.04 | 0.17 | 0.80 |

| 15 | Guaranteed long‐term employment | 0.14 | −0.12 | 0.10 | 0.72 |

| 14 | Working as a full‐time employee rather than a part‐time employee | 0.06 | −0.15 | 0.19 | 0.66 |

| 16 | Being able to afford the holiday one wants | 0.14 | 0.02 | −0.32 | 0.62 |

| 18 | Easy to obtain reduced working hours, child care leave, and family care leave | 0.07 | 0.12 | −0.24 | 0.55 |

| 17 | Being able to work in the desired work style, such as only day or night shifts, without changing the workplace | 0.14 | −0.02 | −0.23 | 0.48 |

| Correlation between factors | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 2 | 0.68 | ー | |||

| 3 | 0.58 | 0.57 | ー | ||

| 4 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.34 | ー | |

| Initial eigenvalues | 13.96 | 3.68 | 2.54 | 2.17 | |

| Contribution rate | 39.89 | 10.51 | 7.24 | 6.20 | |

| Cumulative contribution rate | 39.89 | 50.40 | 57.64 | 63.85 | |

Note: Factor loading >0.45 is shown in bold.

5.2.4. Reliability verification

The α coefficients of the four extracted factors of intrinsic, extrinsic, social and prestige work values were 0.93, 0.87, 0.95 and 0.92, respectively.

5.3. Second phase: Study 2

5.3.1. Participant characteristics

Of the 2600 questionnaires distributed to 52 hospitals with 100 beds or more in six prefectures of Tohoku and 50 nurses at each facility, 1627 were collected (recovery rate: 62.5%). Of these, 39 with incomplete responses were excluded, and 1587 were used for analysis (valid response rate: 61.0%). Details of personal attributes are listed in Table 4.

5.3.2. Item analysis

Item analysis was performed using the 35 items of the nurses' WVS revised in Study 1. No items exceeded the criteria for I–T correlation. On the contrary, items 11, 16 and 18 demonstrated a ceiling effect, and items 31 and 32 exhibited a floor effect. Additionally, items 31 and 32 exceeded the skewness and kurtosis criteria. The exclusion of these five items was examined at an expert meeting that included three researchers with doctoral degrees and three researchers with master's degrees conducting research in nursing management. As a result, for the following two reasons, we decided to exclude the five items and proceeded with the analysis of 30 items. First, unlike Study 1, which targeted only one facility, Study 2 selected the target facilities by random sampling and conducted a survey. Second, as a result of examining whether each concept was properly measured even if it was deleted from the contents of these five questions, it was judged that there was no problem even if it was deleted. Therefore, to verify the validity of the construct, we performed a CFA using the four‐factor structure obtained in Study 1.

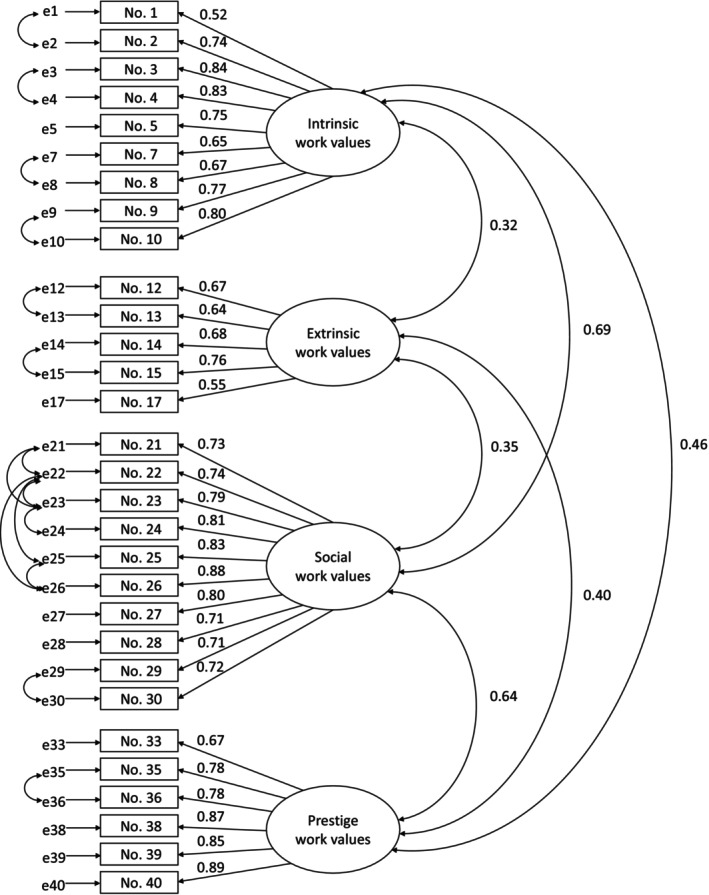

5.3.3. Confirmatory factor analysis

Covariance structure analysis was performed assuming a four‐factor structure comprising nine items of intrinsic work values, five of extrinsic work values, 10 of social work values, and six of prestige work values. The goodness of fit in the early models was χ 2 = 7574.7, df = 399, p < 0.001, GFI = 0.744, AGFI = 0.701, RMSEA = 0.106, CFI = 0.809. These values did not meet the criteria of GFI, AGFI, CFI of ≥0.90 and RMSEA of ≤0.05. As we considered that deleting the item would reduce the validity of the scale contents, we decided to set the covariance between the error variables according to the predetermined rule. The modification indices and item contents were examined, and the model was improved while paying sufficient attention to whether the setting of the covariance between the error variables was theoretically valid. Figure 3 shows the results obtained using the modified model. The range of the modification indices was 1075.50 to 109.42, where the covariance between the error variables was set, and these items were evaluated as similar in item generation. In other words, we did not set the covariance for items that were not evaluated as similar even if the modification indices were high. The coefficients in the figure indicate standardized estimates, the model goodness of fit is χ 2 = 2074.5, df = 384, p < 0.001, GFI = 0.920, AGFI = 0.903, RMSEA = 0.053, CFI = 0.955 and all the paths were significant.

FIGURE 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). χ 2 = 2074.5; df = 384; p < 0.001; GFI = 0.920; AGFI = 0.903; RMSEA = 0.053; CFI = 0.955.

5.3.4. Verification of convergent validity

To verify the convergent validity of the nurses' WVS, Pearson's product–moment correlation coefficient was calculated using three scales: the short version of the WVS, the UWES, and the SWLS (Table 6). First, regarding the correlation coefficients of each subdomain of nurses' WVS and the shortened WVS, the correlation coefficients corresponding to the subdomains of both scales showed moderate‐to‐strong positive correlations ranging from 0.31 to 0.63. Therefore, Hypotheses (1)–(4) were supported. Regarding the correlation coefficient using the total score of the UWES and the total score of the subdomains of nurses' work values, Hypotheses (1)–(4) were supported. Finally, regarding the correlation coefficient between the SWLS and nurses' work values, Hypotheses (1) and (3) were supported, but Hypotheses (2) and (4) were not.

TABLE 6.

Verification of convergent validity using three scales (N = 1587).

| Intrinsic work values | p | Extrinsic work values | p | Social work values | p | Prestige work values | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The short version of the Work Values Scale (WVS) | ||||||||

| Internal value‐oriented | ||||||||

| Self‐growth | 0.55 | *** | 0.13 | *** | 0.59 | *** | 0.51 | *** |

| Sense of accomplishment | 0.31 | *** | 0.14 | *** | 0.45 | *** | 0.45 | *** |

| External value‐oriented | ||||||||

| Social evaluation | 0.13 | *** | 0.24 | *** | 0.31 | *** | 0.53 | *** |

| Economic reward | 0.17 | *** | 0.54 | *** | 0.16 | *** | 0.24 | *** |

| Altruistic value‐oriented | ||||||||

| Contribution to society | 0.39 | *** | 0.09 | *** | 0.63 | *** | 0.50 | *** |

| Contribution to colleagues | 0.35 | *** | 0.13 | *** | 0.47 | *** | 0.47 | *** |

| Contribution to the organization to which they belong | 0.26 | *** | 0.10 | *** | 0.46 | *** | 0.49 | *** |

| Utrecht Work Engagement Scale | 0.35 | *** | 0.00 | 0.51 | *** | 0.44 | *** | |

| Satisfaction with Life Scale | 0.17 | *** | −0.05 | * | 0.27 | *** | 0.15 | *** |

Note: Pearson's product moment correlation coefficient.

Shaded cells show correlation coefficients for corresponding subdomains of nurses’ WVS and shortened WVS.

p < 0.05

p < 0.001.

5.3.5. Verification of known‐groups validity

Table 7 shows the results of unpaired t‐tests using the total score of the subdomains of nurses' work values by sex. Male nurses supported Hypothesis (1), because their mean prestige work values were significantly higher. However, there were no significant differences in social work values, and Hypothesis (2) was not supported. Regarding the correlation coefficient between the subdomains of the nurses' WVS and age, the extrinsic work values showed a significant negative weak correlation, thus supporting Hypothesis (3) (r = −0.21, p < 0.001). The correlation coefficient of social work values was significant but negligible (r = 0.09, p < 0.001). No significant correlation was found between the intrinsic and prestige work values.

TABLE 7.

Comparison of nurses' work values according to sex.

| N | Intrinsic work values | Extrinsic work values | Social work values | Prestige work values | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | p | Mean | SD | p | Mean | SD | p | Mean | SD | p | |||

| Sex | Female | 1464 | 35.2 | 5.8 | 0.474 | 18.6 | 4.1 | 0.057 | 36.4 | 7.2 | 0.327 | 16.7 | 5.3 | 0.014* |

| Male | 123 | 34.8 | 5.4 | 19.3 | 4.4 | 35.7 | 7.4 | 17.9 | 5.4 | |||||

Note: Unpaired t‐test: *p < 0.05; Significant p‐values are shown in bold. SD, standard deviation.

5.3.6. Reliability verification

Cronbach's α coefficients of intrinsic, extrinsic, social and prestige work values were 0.92, 0.83, 0.94 and 0.92, respectively.

5.3.7. Scale score distribution

Table 8 shows the results of the descriptive statistics for each subdomain of the nurses' WVS. Intrinsic, extrinsic, social and prestige work values were arranged in descending order of the item average values.

TABLE 8.

Descriptive statistics of the nurses' Work Values Scale (N = 1587).

| Number of items | Possible range | Range | Mean | SD | Item average value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic work values | 9 | 9–45 | 15–45 | 35.2 | 5.7 | 3.9 |

| Extrinsic work values | 5 | 5–25 | 7–25 | 18.6 | 4.1 | 3.7 |

| Social work values | 10 | 10–50 | 10–50 | 36.3 | 7.2 | 3.6 |

| Prestige work values | 6 | 6–30 | 6–30 | 16.8 | 5.3 | 2.8 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

6. DISCUSSION

6.1. Features of nurses' WVS

The results of this study suggest that the nurses' WVS has acceptable validity and reliability, overcomes the challenges of previously used scales, and can be used primarily for surveys of nurses working in hospitals. The previously used scales had three main challenges, as follows: the inclusion of extraneous concepts, ambiguity regarding nurses' work values and lack of inclusion of the concepts clearly valued by nurses. The nurses' WVS included question items that reflected the characteristics of nurses by referring to a conceptual analysis based on a systematic review (Hara & Asakura, 2021), and scientific procedures were used to assess their validity and reliability (DeVellis, 2016; Mokkink et al., 2019). Thus, the nurses' WVS includes values identified by nurses in previous studies that prior scales failed to address. Additionally, four subdomains proposed by Ros et al. (1999) were reproduced in the EFAs of this study. Therefore, it was empirically revealed that nurses' work values have a four‐component structure with basic human values (Schwartz & Cieciuch, 2022) as the conceptual foundation. Previously used scales did not account for this structure, leading to an incomplete conception of nurses' work values. The present study overcomes past challenges, and thus, may contribute to the appropriate measurement of nurses' work values in future studies. Conducting further research on nurses' work values using this scale can help elucidate the effects of nurses' work values on their attitudes, behaviours, and outcome variables.

Furthermore, the implementation of this newly developed scale has revealed novel findings. Even recent research has included social work values in intrinsic work values and prestige work values in extrinsic work values (Wang & Morav, 2021). In the present study, using the self‐determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017), we hypothesized that the prestige work values included in the extrinsic work values are negatively related to life satisfaction. However, the results showed that prestige work values were significantly positively correlated with life satisfaction. Furthermore, the scale developed in this study makes it possible to separately measure intrinsic work values and social work values and extrinsic work values and prestige work values. In other words, detailed results using the four factors of nurses' work values can be obtained using this scale, thus suggesting the usefulness of the scale.

According to the CFA results for the validity and reliability of nurses' WVS, the goodness of fit of the initial model did not meet the criteria. Therefore, the model was improved while paying sufficient attention to whether the covariance between the error variables was theoretically valid. The goodness‐of‐fit in the modified model did not meet the criteria for RMSEA of ≤0.05. However, if RMSEA is ≥0.1, the fit of the model is judged as bad (Byrne, 2016); therefore, an RMSEA value of 0.053 is considered acceptable. Additionally, as the question items comprising the subfactors of the scale are usually created with an emphasis on uniformity, a moderate correlation was assumed between question items. Therefore, setting the covariance between the error variables within a theoretically explainable range is considered appropriate. In contrast, the items for which the covariance between error variables was set in CFA were those for which similarity was evaluated during item generation. Numerous question items in a survey may induce an answer bias, making it preferable for the question items to be minimal and simple (Streiner et al., 2015). Therefore, in the future, it is necessary to develop a scale with fewer items, such as a short version of the nurses' WVS, with reference to the Item Response Theory.

Furthermore, as a summary of the verification of the convergent validity and known‐groups validity, 12 hypotheses were proposed, of which 10 were supported. In the verification of the known‐groups validity, three hypotheses were set, of which two were supported. Therefore, based on the COSMIN study design checklist (Mokkink et al., 2019), the nurses' WVS developed in this study was judged to have acceptable validity. From the aforementioned data, it can be inferred that nurses' work values are scales that are specialized for nurses and have scientifically acceptable reliability and validity.

6.2. Implications on the use of nurses' WVS

When using the nurses' WVS, this scale is not used by adding all the items, but the four factors of intrinsic, extrinsic, social and prestige work values are scored and used, respectively. Work values are a four‐factor structure based on the four dimensions of human basic values, which is a circular continuum (Schwartz & Cieciuch, 2022). Therefore, the four factors—intrinsic, extrinsic, social and prestige work values—have different vectors. Thus, it is recommended that the four factors be used independently.

Finally, regarding the use of scales for clinical nurses, it has been clarified that nurse work values influence the choice of nurse's place of work (Freeman et al., 2015) and their choice of speciality in nursing (Abrahamsen, 2015). Therefore, recognizing one's own work values may be an index for nurses to select a workplace or specialized field that suits them. Furthermore, if a nurse informs a manager of their own work values, the manager can know the work values of nurses, which may lead to the appropriate provision of support. For example, a nurse who places particular emphasis on intrinsic work values, including self‐growth and skill development, should be recommended seminars and training sessions to help meet the nurse's work values. In addition, by developing a support program that uses the framework of intrinsic, extrinsic, social, and prestige work values, nursing managers may be able to develop support tailored to the diversity of nurses' work values.

6.3. Limitations

This study carefully followed the procedures recommended in the literature for developing psychometric measures, but there are some limitations that must be addressed. First, the current study participants were limited to nurses working in hospitals. In the future, it will be necessary to include nurses working in various fields, such as home‐visit nursing and long‐term care facilities, to verify the efficacy of the scale. Moreover, in this study, the reliability was verified by calculating only the α coefficient, and the verification of stability was not performed. Therefore, further verification of reliability is required, such as verification using a test–retest method. In addition, the nurses' WVS was developed in Japanese and used to survey nurses working in the Tohoku region of Japan. This limits the generalization of results in other parts of the world. For this reason, the psychometric properties of the nurses' WVS need to be evaluated internationally in future studies. Finally, both Studies 1 and 2 were conducted during the COVID‐19 pandemic, and nurses' work values may have been affected. However, due to the cross‐sectional study design, the impact of COVID‐19 could not be determined. In the future, it is necessary to verify the impact of COVID‐19 by considering a longitudinal method of survey.

7. CONCLUSION

In this study, we developed the nurses' WVS based on the concept analysis of nurses' work values and conducted a survey of nurses working in hospitals in the Tohoku region of Japan to verify the reliability and validity of the scale. The results revealed that the 30‐item scale of nurses' work values, including the four factors of intrinsic, extrinsic, social and prestige work values, had acceptable validity and reliability. The nurses' WVS developed in this study should be used to elucidate the relationship between the functions of nurses' work values and outcome variables such as various attitudes and behaviours regarding work. This will enable nurses to lead a happier and more fulfilling work life.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yukari Hara was involved in all phases of the study, including study design, literature search, conduct of the study, data analysis and wrote the different versions of the article. Kyoko Asakura, Nozomu Takada and Shoko Sugiyama helped with the study design and with the interpretation of data. Masako Yamada contributed to the literature search and data analysis. Kyoko Asakura, Masako Yamada, Nozomu Takada and Shoko Sugiyama contributed to the critical review of the different versions of the study. All the authors approved the final version of the article.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research was funded by the JSPS KAKENHI (grant number 18K17425, 22K17434).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the nurses who participated in this study and provided support in data collection.

Hara, Y. , Asakura, K. , Yamada, M. , Takada, N. , & Sugiyama, S. (2023). Development and psychometric evaluation of the nurses' Work Values Scale. Nursing Open, 10, 6957–6971. 10.1002/nop2.1950

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Abrahamsen, B. (2015). Nurses' choice of clinical field in early career. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(2), 304–314. 10.1111/jan.12512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akoglu, H. (2018). User's guide to correlation coefficients. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine, 18(3), 91–93. 10.1016/j.tjem.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basinska, B. A. , & Dåderman, A. M. (2019). Work values of police officers and their relationship with job burnout and work engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 442. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. C. , Perng, S. J. , Chang, F. M. , & Lai, H. L. (2016). Influence of work values and personality traits on intent to stay among nurses at various types of hospital in Taiwan. Journal of Nursing Management, 24(1), 30–38. 10.1111/jonm.12268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello, A. B. , & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- De Winter, J. C. F. , Dodou, D. , & Wieringa, P. A. (2009). Exploratory factor analysis with small sample sizes. Multivariate Behavioural Research, 44, 147–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, R. F. (2016). Scale development: Theory and applications. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. , Emmons, R. A. , Larsen, R. J. , & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilig‐Ruiz, A. , MacDonald, I. , Varin, M. D. , Vandyk, A. , Graham, I. D. , & Squires, J. E. (2018). Job satisfaction among critical care nurses: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 88, 123–134. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi, K. , & Tokaji, A. (2009). Development of the short version of the Work Values Scale. Japanese Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(1), 84–92. 10.2130/jjesp.49.84 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, M. , Beaulieu, L. , & Crawley, J. (2015). Canadian nurse graduates considering migrating abroad for work: Are their expectations being met in Canada? Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 47(4), 80–96. 10.1177/084456211504700405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajdu, G. , & Sik, E. (2018). Age, period, and cohort differences in work centrality and work values. Societies, 8(1), 11. 10.3390/soc8010011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton, D. , & Welsh, D. (2019). Work values of generation Z nurses. Journal of Nursing Administration, 49(10), 480–486. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara, Y. , & Asakura, K. (2021). Concept analysis of nurses' work values. Nursing Forum, 56(4), 1029–1037. 10.1111/nuf.12638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konda, E. , Inagaki, M. , & Tasaki, K. (2018). Development of a measurement scale to evaluate self‐care stability for patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at an older age. Open Journal of Nursing, 8, 905–917. 10.4236/ojn.2018.812068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milfont, T. L. , Milojev, P. , & Sibley, C. G. (2016). Values stability and change in adulthood: A 3‐year longitudinal study of rank‐order stability and mean‐level differences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(5), 572–588. 10.1177/0146167216639245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokkink, L. B. , Prinsen, C. A. C. , Patrick, D. L. , Alonso, J. , Bouter, L. M. , de Vet, H. C. W. , & Terwee, B. T. (2019). COSMIN study design checklist for patient‐reported outcome measurement instruments. Version July. https://www.cosmin.nl/wp‐content/uploads/COSMIN‐study‐designing‐checklist_final.pdf

- Oishi, S. (2009). Doing the science of happiness: What we learned from psychology. Shinyosha. [Google Scholar]

- Orcan, F. (2020). Parametric or non‐parametric: Skewness to test normality for mean comparison. International Journal of Assessment Tools in Education, 7(2), 255–265. 10.21449/ijate.656077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ros, M. , Schwartz, S. H. , & Surkiss, S. (1999). Basic individual values, work values, and the meaning of work. Applied Psychology, 48(1), 49–71. 10.1111/j.1464-0597.1999.tb00048.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M. , & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self‐determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. The Guilford Press. 10.1521/978.14625/28806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saito, Y. , Igarashi, A. , Noguchi‐Watanabe, M. , Takai, Y. , & Yamamoto‐Mitani, N. (2018). Work values and their association with burnout/work engagement among nurses in long‐term care hospitals. Journal of Nursing Management, 26(4), 393–402. 10.1111/jonm.12550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W. B. , Salanova, M. , González‐romá, V. , & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92. 10.1023/A:1015630930326 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schober, P. , Boer, C. , & Schwarte, L. A. (2018). Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 126(5), 1763–1768. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S. H. , & Cieciuch, J. (2022). Measuring the refined theory of individual values in 49 cultural groups: Psychometrics of the revised portrait value questionnaire. Assessment, 29(5), 1005–1019. 10.1177/1073191121998760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazu, A. , Schaufeli, W. B. , Kosugi, S. , Suzuki, A. , Nashiwa, H. , Kato, A. , Sakamoto, M. , Irimajiri, H. , Amano, S. , Hirohata, K. , Goto, R. , & Kitaoka‐Higashiguchi, K. (2008). Work engagement in Japan: Validation of the Japanese version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Applied Psychology, 57(3), 510–523. 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00333.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, N. (2021). Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. American Journal of Applied Mathematics and Statistics, 9(1), 4–11. http://pubs.sciepub.com/ajams/9/1/2 [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D. L. , Norman, G. R. , & Cairney, J. (2015). Health measurement scales: A practical guide to their development and use (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. 10.1093/med/9780199685219.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Super, D. E. (1957). The psychology of careers: An introduction to vocational development. Harper & Bros. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vianen, A. E. (2018). Person–Environment fit: A review of its basic tenets. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 75–101. [Google Scholar]

- Vansteenkiste, M. , Neyrinck, B. , Niemiec, C. P. , Soenens, B. , Witte, H. , & Broeck, A. (2007). On the relations among work value orientations, psychological need satisfaction and job outcomes: A self‐determination theory approach. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80(2), 251–277. 10.1348/096317906X111024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K. Y. , Chou, C. C. , & Lai, J. C. (2019). A structural model of total quality management, work values, job satisfaction and patient‐safety‐culture attitude among nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(2), 225–232. 10.1111/jonm.12669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. , & Morav, L. (2021). Exploring extrinsic and intrinsic work values of British ethnic minorities: The roles of demographic background, job characteristics and immigrant generation. Social Sciences, 10(11), 419. 10.3390/socsci10110419 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yusoff, M. S. B. (2019). ABC of content validation and content validity index calculation. Resource, 11(2), 49–54. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.