This stepped-wedge cluster randomized clinical trial assesses whether implementation of an evidence-based goals-of-care (GOC) video intervention delivered by palliative care educators to older adults in a hospital setting improves GOC documentation.

Key Points

Question

Can implementing an evidence-based goals-of-care (GOC) video intervention delivered by palliative care educators (PCEs) in hospital settings improve GOC documentation among older patients?

Findings

In this pragmatic, stepped-wedge cluster randomized clinical trial that included 10 802 adults aged 65 years or older from 14 units at 2 US hospitals, patients randomized to hospital units receiving the GOC video intervention had more GOC documentation than patients randomized to hospital units receiving usual care.

Meaning

In this trial, the use of a GOC video intervention delivered by PCEs improved GOC documentation for older adults in hospital settings.

Abstract

Importance

Despite the benefits of goals-of-care (GOC) communication, many hospitalized individuals never communicate their goals or preferences to clinicians.

Objective

To assess whether a GOC video intervention delivered by palliative care educators (PCEs) increased the rate of GOC documentation.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This pragmatic, stepped-wedge cluster randomized clinical trial included patients aged 65 years or older admitted to 1 of 14 units at 2 urban hospitals in New York and Boston from July 1, 2021, to October 31, 2022.

Intervention

The intervention involved PCEs (social workers and nurses trained in GOC communication) facilitating GOC conversations with patients and/or their decision-makers using a library of brief, certified video decision aids available in 29 languages. Patients in the control period received usual care.

Main Outcome and Measures

The primary outcome was GOC documentation, which included any documentation of a goals conversation, limitation of life-sustaining treatment, palliative care, hospice, or time-limited trials and was obtained by natural language processing.

Results

A total of 10 802 patients (mean [SD] age, 78 [8] years; 51.6% male) were admitted to 1 of 14 hospital units. Goals-of-care documentation during the intervention phase occurred among 3744 of 6023 patients (62.2%) compared with 2396 of 4779 patients (50.1%) in the usual care phase (P < .001). Proportions of documented GOC discussions for Black or African American individuals (865 of 1376 [62.9%] vs 596 of 1125 [53.0%]), Hispanic or Latino individuals (311 of 548 [56.8%] vs 218 of 451 [48.3%]), non-English speakers (586 of 1059 [55.3%] vs 405 of 863 [46.9%]), and people living with Alzheimer disease and related dementias (520 of 681 [76.4%] vs 355 of 570 [62.3%]) were greater during the intervention phase compared with the usual care phase.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this stepped-wedge cluster randomized clinical trial of older adults, a GOC video intervention delivered by PCEs resulted in higher rates of GOC documentation compared with usual care, including among Black or African American individuals, Hispanic or Latino individuals, non-English speakers, and people living with Alzheimer disease and related dementias. The findings suggest that this form of patient-centered care delivery may be a beneficial decision support tool.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04857060

Introduction

Patients communicating their goals and values to their clinicians promotes patient-centered, high-quality care.1 The aim of such communication is to elicit patients’ preferences and empower them to guide their care.2 Goals-of-care (GOC) communication is not limited to patients facing serious or life-threatening illnesses; rather, it can support adults regardless of age or health status in sharing their preferences, values, and goals for medical care.3,4 Goals-of-care communication has been associated with less intensive medical care near death; reductions in stress, anxiety, and depression in surviving relatives; improvements in patient and family satisfaction; and receipt of goal-concordant care.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 A failure to provide care aligned with patients’ preferences is a medical error.1

Despite the benefits of GOC communication, clinicians often feel poorly prepared or lack sufficient time to engage in discussions about GOC,13,14,15 and patients and families often have difficulty understanding such conversations.16,17 Traditionally, clinicians focus on medical situations rather than patient values and goals and describe hypothetical scenarios and medical interventions to explore GOC. This approach is limited because it is challenging for clinicians to portray medical interventions and their outcomes accurately and for patients to realistically envision such scenarios. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the urgency of improving GOC communication.18,19 Video decision aids that address patient and clinician barriers to GOC discussions offer a potential scalable and rapid strategy to improve GOC communication.

Our team previously developed and studied GOC video decision aids and demonstrated increases in patient communication regarding goals and preferences across clinical settings and populations as well as increases in patients receiving goal-concordant care.11,12,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 The videos do not replace clinical conversations; rather, they provide a common set of video depictions and a shared vocabulary to promote patient-clinician communication. The decision aids, however, have not been studied in the inpatient setting or in a manner that has been integrated with clinical staff. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic and to rapidly increase GOC documentation, we studied the implementation of a suite of videos delivered by palliative care educators (PCEs), who were social workers and nurses trained in palliative care and GOC communication, to proactively engage patients and their caregivers with the videos. We hypothesized that implementing the intervention in hospital settings would increase the rate of GOC documentation for older adults.27

Methods

Trial Design and Oversight

We conducted the pragmatic, multicenter, stepped-wedge cluster randomized Video Inspired Discussions to Improve Ethical Outcomes with Palliative Care Educators (VIDEO-PCE) clinical trial (NCT04857060) to compare PCEs delivering video decision aids and facilitating GOC communication (intervention) with usual care (control). Because the intervention included communication with staff in clinical wards, randomization was performed at the inpatient unit level.28,29 The stepped-wedge cluster randomized clinical trial design was chosen to facilitate implementation of the intervention in all participating inpatient units while minimizing the risk of control units’ exposure to the intervention.30 The trial was conducted between July 1, 2021, and October 31, 2022. A data safety and monitoring board was established and convened biannually. Institutional review board approval was secured through Boston Medical Center. A protocol outlining all trial activities was previously published,27 and the trial protocol is given in Supplement 1. A waiver of individual informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization for the VIDEO-PCE intervention was granted by the Boston University Medical Campus institutional review board, acting as the single institutional review board of record for this study. The waiver was granted due to the determination that the research was not greater than minimal risk under 45 CFR §46. This study was prepared in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline.31

According to the stepped-wedge cluster randomized clinical trial design, each inpatient unit (cluster) began in the control phase and transitioned to the intervention phase at a randomly assigned time (wedge). Seven inpatient units were included from each of the 2 urban sites: Boston Medical Center (Boston, Massachussets) and North Shore University Hospital (Manhasset, New York). To promote covariate balance, prior to the start of data collection, each hospital unit to be included in the trial at Boston Medical Center was paired based on size and function with a matched unit at North Shore University Hospital to create 7 paired clusters. A set of uniform random numbers was generated and used to assign the order of paired clusters for intervention initiation. Following a 2-month baseline period in which no units were exposed to the intervention, a new paired cluster was exposed to the intervention every 2 months (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). Once units were exposed to the intervention, they remained exposed for the remainder of the study.

Patients

Patients aged 65 years or older who were admitted to 1 of the 14 inpatient units for at least 8 weekday daytime hours were eligible for inclusion in the study. We chose 8 hours as a reasonable opportunity for exposure to the intervention. There were no exclusion criteria.32

Intervention

The intervention involved the PCEs facilitating GOC conversations with patients and/or their decision-makers using a library of brief, certified video decision aids that addressed a range of topics (eg, GOC, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, hospice, palliative care, time-limited trials, Alzheimer disease and related dementias [ADRD], and COVID-19). The decision aids are grounded in the theory of shared decision-making33,34 and were designed to assist patients and decision-makers with envisioning their GOC.11,12,20,21,23,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42 The decision aids were available in 29 commonly spoken languages in the New York City and Boston areas and ranged from 2 to 9 minutes in duration. The PCEs were social workers and nurses hired to coordinate with the palliative care team at each site and who received VitalTalk communication skills training via a highly structured series of video conferences.27

Each morning, a list of eligible patients for intervention units was generated by each site’s clinical data warehouse and provided to the PCEs, who used their clinical judgment to triage which patients they would engage. Newly admitted patients without documented GOC discussions were prioritized over patients with documented GOC recorded prior to the start of the intervention. The PCEs did not engage patients with a documented GOC discussion at admission or those who were receiving palliative care services (eFigure in Supplement 2).

The engagement of PCEs was proactive; their services were not contingent on a request for consultation from the treating practitioner. The PCEs were able to tailor the encounter and choose which video to use according to the patient’s circumstances or to not use a video for uncomplicated discussions. The PCEs showed videos on a tablet computer but were also able to share videos via text or email for remote caregivers of patients who were incapacitated (eg, patients with ADRD, patients receiving mechanical ventilation) or for patients in isolation (eg, patients with COVID-19).

The PCEs saw patients independently, engaging patients with GOC shared decision-making conversations. After interacting with patients, PCEs documented findings in the electronic health record (EHR), coordinated care with the patient’s treating team, and stimulated a palliative care consultation in complex cases.

Monthly 1-hour group sessions were conducted with the PCEs throughout the study period by 2 palliative care clinicians (J.R.L. and P.M.R.). These sessions included audit and feedback, education about clinical decision-making, review of difficult cases, and coaching.

Outcomes and Data Collection

The primary end point was GOC documentation in the EHR during the index hospitalization for patients aged 65 years or older. We used ClinicalRegex, version 1.1.2 (Lindvall Lab, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute), a validated natural language processing (NLP) software for NLP-assisted human adjudication of GOC communication documented in the free text of clinical notes as our primary outcome, as previously reported.43,44,45,46,47,48 Goals-of-care communication included any documentation of a conversation about goals (including discussion of a surrogate decision-maker), limitation of life-sustaining treatment, palliative care, hospice, or time-limited trials (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Research staff who were unaware of patients’ treatment-group assignments performed the adjudication within the software.43 Specifically, text blocks identified by NLP from all EHR notes for each patient were presented in the software for evaluation by trained research staff at each site. Training data sets were used to conduct ongoing quality assurance and to ensure consistent adjudication at each site.

Patient-level demographic data were derived from the EHR, and patient-level race and ethnicity data were self-reported. Race and ethnicity categories included American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, non-Hispanic or non-Latino, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, White, and other (Guamanian or Chamorro, Middle Eastern, and other) or more than 1 race. Race and ethnicity were analyzed because the engagement in GOC conversations is not equally distributed among racial and ethnic minority groups, and our study sought to address that disparity. A full description of the data elements collected throughout the VIDEO-PCE trial has been published elsewhere.27

Statistical Power

For the primary outcome of GOC documentation, a sample size of 440 patients per wedge in a χ2 test for independent data provided 80% power at a 2-sided α = .05 to detect a difference in the proportion of patients with GOC documentation of 35% in the intervention group compared with 25% in the usual care group—values consistent with prior research49 and expectation based on clinical data from the 2 health systems. Based on our planned number of steps, enrollment per wedge, and an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.01, the design effect used was 2.72. Thus, we needed to obtain outcome data from the records of at least 2394 patients overall (1197 per health system) to provide 80% power for our analysis of intervention effectiveness. We anticipated that records from 9000 patients would be available for analyses, with the goal of providing adequate power to test for heterogeneity of treatment effects.

Statistical Analysis

The unit of analysis was patients, with an intention-to-treat principle used in which all patients eligible for the intervention were included independent of whether they received PCE services. Data were summarized using means (SDs) for continuous variables and counts with percentages for categorical variables. All hypothesis tests used 1-sided P < .05. Mixed-effects logistic regression models for correlated binary outcome data were used to estimate and test differences in the proportion of patients with GOC documentation in the intervention and usual care groups, accounting for clustering by inpatient unit. Varying secular trends across hospitals were applied for model estimation. We examined the heterogeneous treatment effects by race, ethnicity, language, and diagnosis of ADRD (determined by the presence of a prespecified “ADRD or related dementia” International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision code [eTable 4 in Supplement 2]). All data for evaluating the primary outcome were derived from the EHRs. Analyses relied on data from the patient’s index hospitalization; there was no crossover of data for patients with multiple hospital admissions. Patients who transferred between study units during their index hospitalization were assigned to contribute intervention data if they spent at least 8 daytime weekday hours in an intervention unit. We conducted all analyses using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

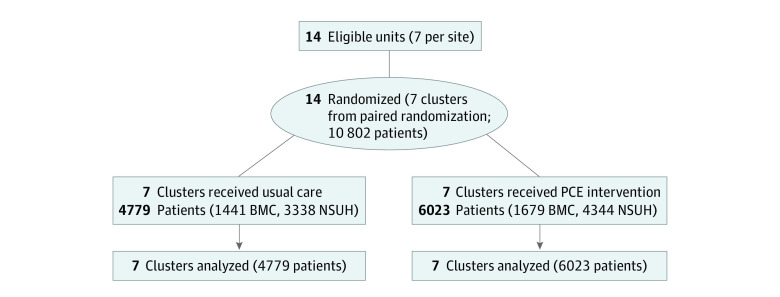

During the study period, 10 802 patients (mean [SD] age, 78 [8] years; 5218 female [48.3%]; 5574 male [51.6%]) were admitted to 1 of 14 inpatient units at 2 US hospitals (Figure 1). Overall, 4779 and 6023 patients were hospitalized during the usual care and intervention phases, respectively (Table 1). Of all patients, 0.3% were American Indian or Alaska Native; 8.3%, Asian; 23.2%, Black or African American; 9.2%, Hispanic or Latino; 88.3%, non-Hispanic or non-Latino; less than 0.1%, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; 51.8%, White, and 9.9% other or more than 1 race. Patients in the usual care and intervention groups were similar in baseline demographics (eTables 1 and 3 in Supplement 2).

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

BMC indicates Boston Medical Center; NSUH, North Shore University Hospital; PCE, palliative care educator.

Table 1. Characteristics of Eligible Patientsa.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (n = 4779) | PCE intervention (n = 6023) | Overall (N = 10 802) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 78 (8) | 78 (8) | 78 (8) |

| Sexb | |||

| Female | 2331 (48.8) | 2887 (47.9) | 5218 (48.3) |

| Male | 2440 (51.1) | 3134 (52.0) | 5574 (51.6) |

| Race | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 14 (0.3) | 16 (0.3) | 30 (0.3) |

| Asian | 386 (8.1) | 509 (8.5) | 895 (8.3) |

| Black or African American | 1125 (23.5) | 1376 (22.8) | 2501 (23.2) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 3 (0.1) | 2 (<0.1) | 5 (<0.1) |

| White | 2483 (52.0) | 3113 (51.7) | 5596 (51.8) |

| Other or >1 racec | 454 (9.5) | 617 (10.2) | 1071 (9.9) |

| Declined or missing | 314 (6.6) | 390 (6.5) | 704 (6.5) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 451 (9.4) | 548 (9.1) | 999 (9.2) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 4200 (87.9) | 5337 (88.6) | 9537 (88.3) |

| Declined or missing | 128 (2.7) | 138 (2.3) | 266 (2.5) |

| Language | |||

| English | 3864 (80.9) | 4909 (81.5) | 8773 (81.2) |

| Spanish | 315 (6.6) | 352 (5.8) | 667 (6.2) |

| Other | 548 (11.5) | 707 (11.7) | 1255 (11.6) |

| Unknown or missing | 52 (1.1) | 55 (0.9) | 107 (1.0) |

| ADRD diagnosisd | |||

| Yes | 570 (11.9) | 681 (11.3) | 1251 (11.6) |

| No | 4209 (88.0) | 5342 (88.7) | 9551 (88.4) |

Abbreviations: ADRD, Alzheimer disease and related dementias; PCE, palliative care educator.

All data were obtained from the electronic health records at each study site. Sex, race, and ethnicity were self-reported at each site.

Ten patients (8 receiving usual care; 2, PCE intervention) had unknown sex.

Other was composed of Guamanian or Chamorro, Middle Eastern, and other.

Determined by the presence of a prespecified “ADRD or related dementia” International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code. A full list of ICD-10 codes used to identify ADRD diagnoses is given in eTable 4 in Supplement 2.

Intervention Fidelity

Each hospital had 3 PCEs over the course of the trial. The 6 total PCEs worked Monday through Friday for a mean (SD) of 4.0 (0.6) full-time equivalent per month of the intervention period. The PCEs evaluated and wrote notes on 3355 of the 6023 patients hospitalized during the intervention phase (55.7%). During the final 6 months of the trial, a mean (SD) of 70.9 (7.1) patients per month were seen and had a PCE note for each monthly full-time equivalent of PCE effort.

There were 1672 videos viewed during the intervention period among 3355 patients evaluated by PCEs (49.8%).20,50 Most videos (1333 [79.7%]) were viewed past the 50% mark, and 470 videos (28.1%) were viewed remotely. Of the 1672 video views, 869 (52.0%) were about GOC; 293 (17.5%), ADRD; 273 (16.3%), advance directives; and 162 (9.7%), cardiopulmonary resuscitation, intubation, and ventilatory support. Of the 1672 views, 324 (19.4%) were non-English videos.

Outcomes

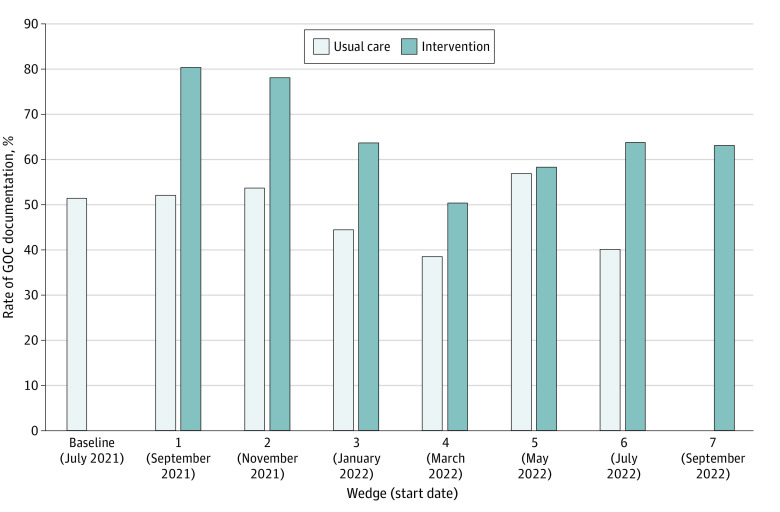

The proportion of hospitalized patients with GOC documentation was greater for patients during the intervention phase (3744 of 6023 [62.2%]) compared with the usual care phase (2396 of 4779 [50.1%]) (P < .001) (Table 2). When adjusted for mixed-effects logistic regression models for hospital and secular trend, there was an increased odds of GOC documentation among intervention-phase patients (odds ratio, 3.37; 95% CI, 2.90-3.92) (Table 2). The proportions of documented conversations of goals (3562 [59.1%] vs 2258 [47.2%]; P < .001), limitation of life-sustaining treatment (1979 [32.9%] vs 1242 [26.0%]; P < .001), and palliative care (2067 [34.3%] vs 700 [14.6%]; P < .001) were greater for patients during the intervention phase compared with the usual care phase (Table 2). Goals-of-care documentation rate by wedge is shown in Figure 2.

Table 2. Comparison of Goals-of-Care Documentation During the Usual Care Phase and PCE Intervention Phase.

| Documentation domain | Patients, No. (%) | OR (95% CI)a | P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (n = 4779) | PCE intervention (n = 6023) | |||

| Overall | 2396 (50.1) | 3744 (62.2) | 3.37 (2.90-3.92) | <.001 |

| Goals conversation | 2258 (47.2) | 3562 (59.1) | 3.22 (2.77-3.74) | <.001 |

| Limitation of life-sustaining treatment | 1242 (26.0) | 1979 (32.9) | 1.84 (1.57-2.17) | <.001 |

| Palliative care | 700 (14.6) | 2067 (34.3) | 4.33 (3.65-5.15) | <.001 |

| Hospice | 461 (9.6) | 597 (9.9) | 1.15 (0.92-1.44) | .23 |

| Time-limited trials | 20 (0.4) | 105 (1.7) | 1.55 (0.70-3.42) | .28 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; PCE, palliative care educator.

A mixed-effects logistic regression model for correlated binary data adjusted for hospital and secular trend was used.

P value for parameter estimates accounting for clustering by inpatient unit.

Figure 2. Comparison of Goals-of-Care (GOC) Documentation Rates by Cluster and Wedge.

The last date in the figure (September 2022) corresponds to the start date of the last 2-month intervention period of the trial. As such, the last date of the intervention was October 31, 2022.

The proportions of documented GOC discussions for Black or African American individuals (865 of 1376 [62.9%] vs 596 of 1125 [53.0%]), Hispanic or Latino individuals (311 of 548 [56.8%] vs 218 of 451 [48.3%]), non-English speakers (586 of 1059 [55.3%] vs 405 of 863 [46.9%]), and people living with ADRD (520 of 681 [76.4%] vs 355 of 570 [62.3%]) were greater for patients during the intervention phase compared with usual care phase (Table 3). There was no evidence of heterogeneity of treatment effects by race, ethnicity, language, or diagnosis of ADRD.

Table 3. Comparison of Goals-of-Care Documentation by Race and Ethnicity, Language, and ADRD Diagnosis During the Usual Care Phase and PCE Intervention Phasea.

| Subgroup | Patients, No./total No. (%) | OR (95% CI)b | P valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care | PCE intervention | |||

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| Asian | 179/386 (46.4) | 284/509 (55.8) | 3.25 (1.92-5.51) | <.001 |

| Black or African American | 596/1125 (53.0) | 865/1376 (62.9) | 3.51 (2.57-4.81) | <.001 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 218/451 (48.3) | 311/548 (56.8) | 2.10 (1.33-3.32) | .002 |

| White | 1232/2483 (49.6) | 2001/3113 (64.3) | 3.38 (2.74-4.17) | <.001 |

| Other or >1 raced | 224/454 (49.3) | 356/617 (57.7) | 2.59 (1.59-4.20) | <.001 |

| English speaker | ||||

| Yes | 1962/3864 (50.8) | 3120/4909 (63.6) | 3.49 (2.96-4.13) | <.001 |

| No | 405/863 (46.9) | 586/1059 (55.3) | 2.52 (1.77-3.59) | <.001 |

| ADRD diagnosise | 355/570 (62.3) | 520/681 (76.4) | 3.64 (2.24-5.90) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ADRD, Alzheimer disease and related dementias; OR, odds ratio; PCE, palliative care educator.

Goals-of-care documentation is the composite of conversations about goals, limitation of life-sustaining treatment, palliative care, hospice, and time-limited trials.

A mixed-effects logistic regression model for correlated binary data adjusted for hospital and secular trend was used.

P value for parameter estimates accounting for clustering by inpatient unit.

Other was composed of Guamanian or Chamorro, Middle Eastern, and other.

Determined by the presence of a prespecified “ADRD or related dementia” International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code. A full list of ICD-10 codes used to identify ADRD diagnoses is given in eTable 4 in Supplement 1.

Discussion

In this pragmatic, stepped-wedge cluster randomized clinical trial that included a racially and ethnically diverse population, an intervention in which PCEs shared decision-making video decision aids and facilitated GOC communication increased the proportion of hospitalized patients with GOC documentation. Video use was robust for patients seen by PCEs, demonstrating successful implementation. The intervention was also associated with increased GOC documentation for Black or African American individuals, Hispanic or Latino individuals, non-English speakers, and patients living with ADRD.

Providing optimal serious illness care involves understanding patient values, goals, and preferences. For many medical decisions, there often is not a clear superior path for treatment and multiple reasonable options exist that require engaging patient values and preferences.34 Videos offer concrete images to better inform discussions and to spark GOC communication. Improving clinician communication and preserving patient autonomy have been the focus of a large corpus of research and trials since at least the time of the Study to Understand Prognoses Preferences Outcomes and Risks of Treatment (SUPPORT) in the 1990s.51,52 Yet, despite the professional and societal commitment51 toward improving GOC communication, most patients still do not communicate their preferences and values to their clinicians.53 The VIDEO-PCE trial offers a potential path forward.

The VIDEO-PCE trial leveraged a proactive model in which PCEs engaged all patients aged 65 years or older in GOC communication by providing them with videos that raise patients’ awareness and understanding of treatment options and possible outcomes.34 Instead of relying on busy clinicians or waiting for a palliative care consultation to engage in GOC communication, patients or their caregivers were engaged in GOC discussions and shared decision-making as a routine part of medical care. Importantly, PCEs documented GOC communication in the EHR and followed up directly with the clinical team. The PCE model allows for more efficient use of limited staff resources and leverages videos to empower patients or their caregivers.

A key finding of the trial was increased GOC documentation across each racial and ethnic group. Prior research suggests that Black or African American and Hispanic or Latino individuals are less likely to engage or be engaged in GOC conversations.53,54,55 For many individuals and especially those from racial and ethnic communities disproportionally impacted by COVID-19, GOC discussions are real and no longer hypothetical. To date, the VIDEO-PCE trial is the third published large pragmatic trial since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic to suggest that GOC interventions can be designed that engage Black or African American and Hispanic or Latino patients in GOC conversations.20,56 Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, GOC discussions may be more salient, especially for individuals from communities that have been disproportionally impacted by COVID-19.

Notably, the intervention increased GOC documentation for English and non-English speakers as well as for persons living with ADRD. The videos were available in 29 languages, 19.4% of videos viewed were in languages other than English, and 17.5% of the videos viewed were related to caregiving for a person with ADRD. Engaging non-English speakers with videos in a patient’s or caregiver’s preferred language and sharing ADRD-specific videos via text or email with caregivers of persons living with ADRD who were often remote allowed for patients and caregivers to be meaningfully engaged in a shared decision-making discussion.

It is notable that the VIDEO-PCE model not only increased GOC documentation rates overall but also did so among groups that are least likely to have documented shared decision-making conversations. While the intervention improved GOC documentation in all groups, it did not narrow underlying racial and ethnic disparities. More research is needed to identify opportunities to ameliorate racial and ethnic disparities in GOC decision-making.

Limitations

Our findings must be considered in the context of several limitations. First, stepped-wedge designs have significant limitations (eg, partial confounding by time) and should be used sparingly and when appropriate.30,57,58 Although individually randomized or parallel cluster trials are frequently preferable, the circumstances of the inpatient setting (eg, shared rooms and shared staff for units) make contamination a significant concern, beyond what is tolerated in individual randomization designs.57,59 In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2 hospitals in our study were embarking on implementing the GOC intervention but agreed to stagger the rollout in a stepped-wedge fashion to more rigorously study outcomes. Nonetheless, the relatively short wedge lengths (ie, 2 months) and robust number of clusters helped allay some of the inherent design flaws of stepped-wedge trials.58 Second, we looked at GOC documentation rates during the index hospitalization. Long-term studies looking at care delivery and concordance with patient goals are ongoing; however, assessing GOC documentation suggests a shared decision-making encounter, which is the gold standard for patient-centered, high-quality care.34,60,61 Third, we did not analyze the quality of GOC documentation during the intervention and usual care phases. Qualitative analyses from both phases are ongoing. Fourth, the intervention was designed for PCEs to approach patients for a single encounter. Longitudinal interventions are likely to have more effect and may provide the opportunity to better support patients and families with lower levels of health literacy or trust and may be the key to managing racial and ethnic disparities. Fifth, this intervention was conducted with hospitalized patients; moving the intervention to the outpatient setting may provide a milieu that may be more effective, not influenced by an acute decompensation, and more amenable to longitudinal engagement. Sixth, the videos used in this intervention are intended to be support tools used in clinical encounters. Accordingly, we were not able to differentiate the effect of the videos from that of the PCEs.

Conclusions

The VIDEO-PCE randomized clinical trial demonstrated a significant and clinically meaningful increase in GOC documentation rates among hospitalized older adults receiving a GOC video intervention delivered by PCEs, a scalable intervention that could be quickly implemented across many hospitals, compared with usual care. Notably, the intervention resulted in an increase in GOC documentation for Black or African American individuals, Hispanic or Latino individuals, non-English speakers, and persons living with ADRD. Such benefits have been elusive. This trial found a benefit of a proactive model of care with social workers and nurses to facilitate GOC communication with video decision support tools that were available in 29 languages. To date, the VIDEO-PCE intervention represents one of the first rapidly adoptable paradigms with a clinically meaningful increase in GOC documentation, a widely used quality metric that reflects high-quality, patient-centered care delivery.

Trial Protocol

eFigure. Protocol for PCE Patient Interaction

eTable 1. VIDEO-PCE Trial Intervention Timeline

eTable 2. Natural Language Processing Keyword Library

eTable 3. Primary Discharge Diagnosis of Eligible Patients

eTable 4. List of ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes Used to Identify ADRD Patients

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Sanders JJ, Curtis JR, Tulsky JA. Achieving goal-concordant care: a conceptual model and approach to measuring serious illness communication and its impact. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(S2):S17-S27. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Secunda K, Wirpsa MJ, Neely KJ, et al. Use and meaning of “goals of care” in the healthcare literature: a systematic review and qualitative discourse analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1559-1566. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05446-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):821-832.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hickman SE, Lum HD, Walling AM, Savoy A, Sudore RL. The care planning umbrella: the evolution of advance care planning. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(7):2350-2356. doi: 10.1111/jgs.18287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665-1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernacki R, Paladino J, Neville BA, et al. Effect of the serious illness care program in outpatient oncology: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(6):751-759. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paladino J, Bernacki R, Neville BA, et al. Evaluating an intervention to improve communication between oncology clinicians and patients with life-limiting cancer: a cluster randomized clinical trial of the serious illness care program. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(6):801-809. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1203-1208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klement A, Marks S. The pitfalls of utilizing “goals of care” as a clinical buzz phrase: a case study and proposed solution. Palliat Med Rep. 2020;1(1):216-220. doi: 10.1089/pmr.2020.0063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Jawahri A, Mitchell SL, Paasche-Orlow MK, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a CPR and intubation video decision support tool for hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1071-1080. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3200-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Jawahri A, Traeger L, Greer JA, et al. Randomized trial of a hospice video educational tool for patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. Cancer. 2020;126(15):3569-3578. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Block SD. Medical education in end-of-life care: the status of reform. J Palliat Med. 2002;5(2):243-248. doi: 10.1089/109662102753641214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones L, Harrington J, Barlow CA, et al. Advance care planning in advanced cancer: can it be achieved? an exploratory randomized patient preference trial of a care planning discussion. Palliat Support Care. 2011;9(1):3-13. doi: 10.1017/S1478951510000490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wenrich MD, Curtis JR, Ambrozy DA, Carline JD, Shannon SE, Ramsey PG. Dying patients’ need for emotional support and personalized care from physicians: perspectives of patients with terminal illness, families, and health care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(3):236-246. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00694-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piggott KL, Patel A, Wong A, et al. Breaking silence: a survey of barriers to goals of care discussions from the perspective of oncology practitioners. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):130. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5333-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.You JJ, Downar J, Fowler RA, et al. ; Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network . Barriers to goals of care discussions with seriously ill hospitalized patients and their families: a multicenter survey of clinicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):549-556. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID data tracker. Accessed January 18, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#demographicsovertime

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Provisional COVID-19 deaths by week, sex, and age. Accessed July 24, 2023. https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/Provisional-COVID-19-Deaths-by-Week-Sex-and-Age/vsak-wrfu

- 20.Volandes AE, Zupanc SN, Paasche-Orlow MK, et al. Association of an advance care planning video and communication intervention with documentation of advance care planning among older adults: a nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e220354. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Jawahri A, Podgurski LM, Eichler AF, et al. Use of video to facilitate end-of-life discussions with patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):305-310. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.7502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):453-460. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Jawahri A, Paasche-Orlow MK, Matlock D, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an advance care planning video decision support tool for patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2016;134(1):52-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Barry MJ, et al. Video decision support tool for advance care planning in dementia: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;338:b2159. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Volandes AE, Lehmann LS, Cook EF, Shaykevich S, Abbo ED, Gillick MR. Using video images of dementia in advance care planning. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(8):828-833. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen SM, Volandes AE, Shaffer ML, Hanson LC, Habtemariam D, Mitchell SL. Concordance between proxy level of care preference and advance directives among nursing home residents with advanced dementia: a cluster randomized clinical trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57(1):37-46.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lakin JR, Zupanc SN, Lindvall C, et al. Study protocol for Video Images about Decisions to Improve Ethical Outcomes with Palliative Care Educators (VIDEO-PCE): a pragmatic stepped wedge cluster randomised trial of older patients admitted to the hospital. BMJ Open. 2022;12(7):e065236. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray DM. Design and Analysis of Group-Randomized Trials. Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murray DM, Taljaard M, Turner EL, George SM. Essential ingredients and innovations in the design and analysis of group-randomized trials. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:1-19. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hemming K, Taljaard M. Reflection on modern methods: when is a stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial a good study design choice? Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49(3):1043-1052. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, Group C; CONSORT Group . CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Int J Surg. 2011;9(8):672-677. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2011.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F, Donnan P, Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M. The PRECIS-2 tool: designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ. 2015;350:h2147. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barry MJ. Health decision aids to facilitate shared decision making in office practice. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(2):127-135. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-2-200201150-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making–pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780-781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Epstein AS, Volandes AE, Chen LY, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a cardiopulmonary resuscitation video in advance care planning for progressive pancreas and hepatobiliary cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(6):623-631. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCannon JB, O’Donnell WJ, Thompson BT, et al. Augmenting communication and decision making in the intensive care unit with a cardiopulmonary resuscitation video decision support tool: a temporal intervention study. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1382-1387. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Volandes AE, Ariza M, Abbo ED, Paasche-Orlow M. Overcoming educational barriers for advance care planning in Latinos with video images. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(5):700-706. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Volandes AE, Mitchell SL, Gillick MR, Chang Y, Paasche-Orlow MK. Using video images to improve the accuracy of surrogate decision-making: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(8):575-580. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Volandes AE, Ferguson LA, Davis AD, et al. Assessing end-of-life preferences for advanced dementia in rural patients using an educational video: a randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(2):169-177. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Volandes AE, Brandeis GH, Davis AD, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a goals-of-care video for elderly patients admitted to skilled nursing facilities. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(7):805-811. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Mitchell SL, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a video decision support tool for cardiopulmonary resuscitation decision making in advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(3):380-386. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.9570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Davis AD, Eubanks R, El-Jawahri A, Seitz R. Use of video decision aids to promote advance care planning in Hilo, Hawai’i. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1035-1040. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3730-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.ClinicalRegex . Version 1.1.2. Lindvall Lab, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. 2021. Accessed July 24, 2023. https://lindvalllab.dana-farber.org/

- 44.Lee RY, Brumback LC, Lober WB, et al. Identifying goals of care conversations in the electronic health record using natural language processing and machine learning. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(1):136-142.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Udelsman BV, Lee KC, Lilley EJ, Chang DC, Lindvall C, Cooper Z. Variation in serious illness communication among surgical patients receiving palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(3):411-414. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee KC, Udelsman BV, Streid J, et al. Natural language processing accurately measures adherence to best practice guidelines for palliative care in trauma. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;59(2):225-232.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lilley EJ, Lindvall C, Lillemoe KD, Tulsky JA, Wiener DC, Cooper Z. Measuring processes of care in palliative surgery: a novel approach using natural language processing. Ann Surg. 2018;267(5):823-825. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lindvall C, Lilley EJ, Zupanc SN, et al. Natural language processing to assess end-of-life quality indicators in cancer patients receiving palliative surgery. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(2):183-187. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Temel JS, Greer JA, Gallagher ER, et al. Electronic prompt to improve outpatient code status documentation for patients with advanced lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(6):710-715. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.2203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mitchell SL, Volandes AE, Gutman R, et al. Advance care planning video intervention among long-stay nursing home residents: a pragmatic cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(8):1070-1078. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.The SUPPORT Principal Investigators . A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients: the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA. 1995;274(20):1591-1598. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530200027032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Center for Ethics in Health Care, US Department of Veterans Affairs. The VA Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative. Accessed July 24, 2023. https://www.ethics.va.gov/LSTDI.asp

- 53.Institute of Medicine . Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Welch LC, Teno JM, Mor V. End-of-life care in black and white: race matters for medical care of dying patients and their families. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1145-1153. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53357.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.True G, Phipps EJ, Braitman LE, Harralson T, Harris D, Tester W. Treatment preferences and advance care planning at end of life: the role of ethnicity and spiritual coping in cancer patients. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30(2):174-179. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Curtis JR, Lee RY, Brumback LC, et al. Intervention to promote communication about goals of care for hospitalized patients with serious illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;329(23):2028-2037. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.8812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ellenberg SS. The stepped-wedge clinical trial: evaluation by rolling deployment. JAMA. 2018;319(6):607-608. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taljaard M, Magnus D. Grand rounds ethics and regulatory series December 9, 2022—the stepped wedge cluster randomized trial: friend or foe? NIH Pragmatic Trials Collaboratory. December 9, 2022. Accessed July 24, 2023. https://rethinkingclinicaltrials.org/news/grand-rounds-ethics-and-regulatory-series-december-9-2022-the-stepped-wedge-cluster-randomized-trial-friend-or-foe-monica-taljaard-phd-david-magnus-phd/

- 59.Hemming K, Taljaard M, Moerbeek M, Forbes A. Contamination: how much can an individually randomized trial tolerate? Stat Med. 2021;40(14):3329-3351. doi: 10.1002/sim.8958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barry M, Levin C, MacCuaig M, Mulley A, Sepucha K; Boston ISDM Planning Committee . Shared decision making: vision to reality. Health Expect. 2011;14(Suppl 1):1-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00641.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barry MJ. Shared decision making: informing and involving patients to do the right thing in health care. J Ambul Care Manage. 2012;35(2):90-98. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e318249482f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eFigure. Protocol for PCE Patient Interaction

eTable 1. VIDEO-PCE Trial Intervention Timeline

eTable 2. Natural Language Processing Keyword Library

eTable 3. Primary Discharge Diagnosis of Eligible Patients

eTable 4. List of ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes Used to Identify ADRD Patients

Data Sharing Statement