Abstract

Aim

Previous behavioral pharmacology studies involving rodents suggested riluzole had potential to be an ideal psychotropic drug for psychiatric disorders with anxiety or fear as primary symptoms. Several clinical studies have recently been conducted. The purpose of this study was to gather information about the efficacy and tolerability of riluzole for patients with those symptoms.

Methods

We searched PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, EMBASE, and the Cochrane database from inception until April 2021, and performed manual searches for additional relevant articles. This review included: (1) studies involving participants that were patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive‐compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), acute stress disorder, or phobias; and (2) randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or intervention studies (e.g., single arm trials) examining the effects and safety of riluzole.

Results

Of the 795 identified articles, four RCTs, one RCT subgroup‐analysis, and three open‐label trials without control groups met the inclusion criteria. Most trials evaluated the efficacy of riluzole as an augmentation therapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and other antidepressants for PTSD, OCD, or GAD. However, there was insufficient evidence to confirm the effects of riluzole for patients with these psychiatric disorders. Most trials demonstrated adequate study quality.

Conclusions

This review found insufficient evidence to confirm the effects of riluzole for psychiatric disorders with anxiety or fear as primary symptoms. It would be worthwhile to conduct studies that incorporate novel perspectives, such as examining the efficacy of riluzole as a concomitant medication for psychotherapy.

Keywords: anxiety, fear, intervention, riluzole, systematic review

The purpose of this study was to gather information about the efficacy and tolerability of riluzole for patients with psychiatric disorders with anxiety or fear as primary symptoms. This review found insufficient evidence to confirm the effects of riluzole for psychiatric disorders with anxiety or fear as primary symptoms. It would be worthwhile to conduct studies that incorporate novel perspectives, such as examining the efficacy of riluzole as a concomitant medication for psychotherapy.

1. INTRODUCTION

Drugs with pharmacological effects that modulate glutamatergic neurotransmission have attracted increased attention as promising novel candidates for psychiatric disorders with anxiety and fear as primary symptoms, such as generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive‐compulsive disorder (OCD), and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). 1 Riluzole is one such drug, which is a therapeutic agent that slows the progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) by acting as an inhibitory modulator of glutamatergic neurotransmission. 2 Although the molecular mechanisms of riluzole are not yet fully understood, riluzole has been shown to block the glutamatergic system at the presynaptic or postsynaptic level, primarily by the following mechanisms: inhibiting voltage‐activated sodium channels, 3 inhibiting voltage‐activated Ca2+ channels, 4 inhibiting GABA uptake, 5 potentiating glutamate uptake, 6 and blocking postsynaptic glutamate receptors without a direct receptor interaction. 7

Previous behavioral pharmacology studies in rats and mice showed that riluzole had potential to be a breakthrough and ideal psychotropic drug with unprecedented characteristics for psychiatric disorders with anxiety or fear as primary symptoms. For example, riluzole was reported to have antidepressant‐like effects 8 and anxiolytic‐like effects. 9 Although benzodiazepines are associated with several side effects, including motor incoordination and memory/cognitive dysfunction, 10 , 11 , 12 riluzole does not impair these functions. 9 , 13 Furthermore, recent studies showed that riluzole enhanced extinction learning of fear memory, 14 and may also have an inhibitory effect on fear memory reconsolidation. 15 These results suggest riluzole could be an ideal concomitant medication with exposure therapy.

Clinical trials have examined the effects of riluzole on GAD, 16 OCD, 17 and PTSD. 18 In addition, systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for OCD or depression reported that riluzole had favorable safety and tolerability with few serious adverse events, although no statistically significant effect of riluzole was shown compared with the control groups. 19 , 20 However, previous systematic reviews had several limitations. For example, they did not include a recent study focused on PTSD 18 that indicated riluzole may be effective, and they only included RCTs, meaning the information was limited. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to systematically and comprehensively accumulate information from both intervention studies (e.g., single arm trials) and RCTs on the efficacy and tolerability of riluzole for psychiatric disorders with anxiety and fear as primary symptoms.

2. METHOD

2.1. Search strategy

The protocol for this systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD: 42017077873). 21 We conducted this systematic review in accordance with the published protocol, and the reporting was consistent with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 22 We searched several electronic bibliographic databases from inception to April 2021, including: PubMed (from 1949), PsycINFO (from 1806), CINAHL (from 1981), EMBASE (from 1974), and the Cochrane database (from 1993). The search terms used were as follows: (riluzole) AND ((anxiet*) OR (phobi*) OR (fear*) OR (panic*) OR (social*) OR (GAD) OR (obsessive‐compulsive‐disorder*) OR (OCD) OR (posttraumatic‐stress‐disorder*) OR (PTSD) OR (acute‐stress*) OR (ASD)). We also examined reference lists of the included studies and clinical trial registries (e.g., ClinicalTrials.gov, UMIN) to identify additional relevant studies.

2.2. Study eligibility

Studies were included in this review if they were as follows: (1) studies in which the participants were patients with GAD, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, OCD, PTSD, acute stress disorder, or phobias; and (2) randomized controlled trials or intervention studies (e.g., single arm trials) examining the effectiveness and safety of riluzole. We excluded studies that were reviews, commentaries, editorials, conference abstracts, or case reports.

2.3. Review process

After removing duplicate records, the titles and abstracts of studies identified by the database and manual searches were screened by at least two of the present authors independently to identify studies that potentially met the eligibility criteria for this review. The full texts of articles that were identified as eligible candidates were reviewed by at least two authors against the eligibility criteria. In cases of disagreement, a final decision was made through discussion among the researchers.

2.4. Data extraction

The information and data extracted from the reviewed studies included: the study design, inclusion/exclusion criteria, characteristics of study participants (age, psychiatric disorder), number of participants, dosage of riluzole, dosing period, administration route, adherence to interventions, proportion of participants who were followed up, scores for symptom scales and psychological measurements, and the number of patients with any adverse effects. Next, we created summary tables of the included studies. However, we did not perform a meta‐analysis because of the large variability in outcomes across studies. Research ethics committee approval was not necessary because this review was based on published articles.

2.5. Efficacy and tolerability indicators

We evaluated changes in scores for the symptom scales and psychological measurements as efficacy indicators. In addition, we evaluated the number of patients with any adverse effects and adherence to the intervention as tolerability indicators.

2.6. Assessment of risk of bias

We assessed the risk of bias for RCTs using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool version 2, as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2. 23 For each included study, we judged bias relating to the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcomes, selection of the reported results, and other potential threats to validity.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Searches and article selection

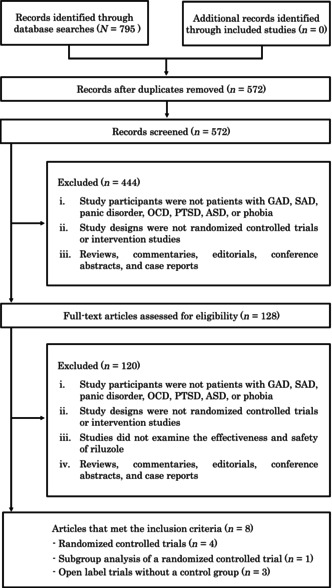

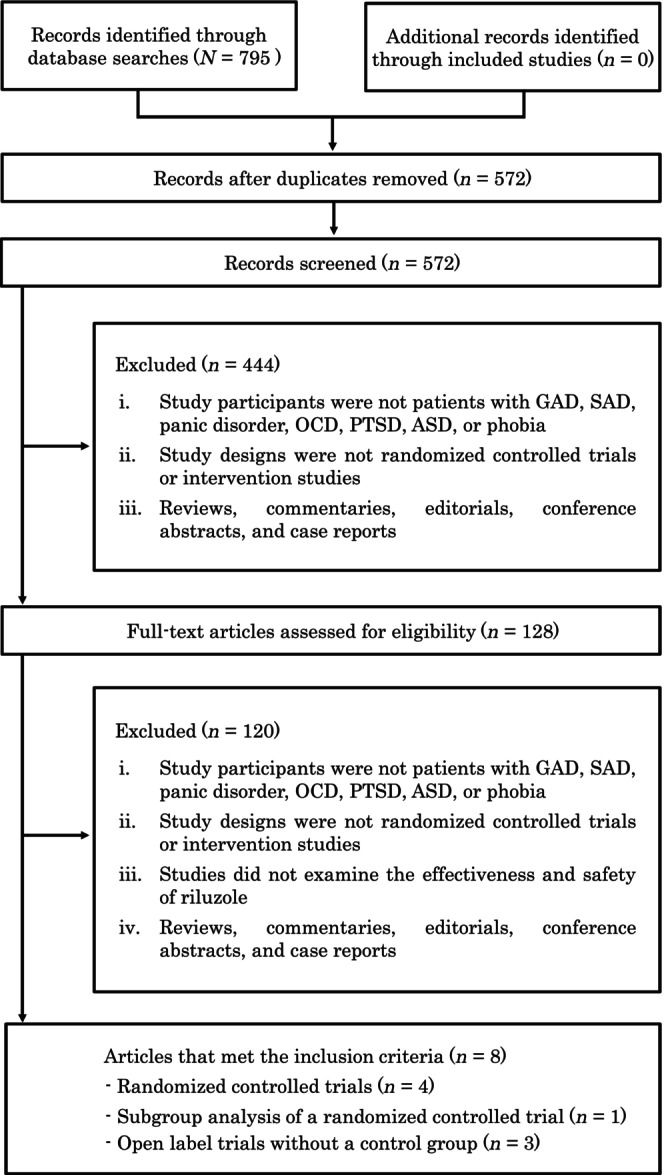

Our search strategy identified 795 records (Figure 1): PubMed (n = 124), PsycINFO (n = 82), CINAHL (n = 21), EMBASE (n = 518), and the Cochrane database (n = 50). No records were retrieved by the manual searches. Of these 795 records, 572 articles were retained after removing duplicates. After screening the titles and abstracts against the study inclusion criteria, the full texts of 128 articles were obtained for further assessment of eligibility. Of these 128 articles, eight studies met our inclusion criteria and examined the effects of riluzole for patients: four RCTs, 17 , 18 , 24 , 25 one subgroup analysis 26 of the RCT by Spangler et al. (2020), 18 and three open label trials without control groups 16 , 27 , 28 (Table 1). In this study, there was insufficient number of RCT reports to perform meta‐analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process. ASD, acute stress disorder; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; OCD, obsessive‐compulsive disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SAD, social anxiety disorder.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the eight included studies.

| Author (year), country | Study design | Intervention group (n) | Control group (n) | Intervention duration | Measurement of efficacy | Adverse events and side effects in intervention group | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | |||||||

|

Spangler et al., 13 |

RCT | Riluzole 100 mg/day b + stable dose of SSRI/SNRI (n = 36) | Placebo + stable dose of SSRI/SNRI (n = 38) | 8 weeks | CAPS, PCL‐S, MADRS, HAM‐A, SDS | Gastrointestinal symptoms, difficulty concentrating, fatigue, sleepiness | No significant differences between the riluzole and placebo groups in CAPS, PCL‐S, MADRS, HAM‐A, SDS scores. |

| Obsessive‐compulsive disorder in adults | |||||||

| Coric et al., 22 US | OLT | Riluzole 100 mg/day + antidepressant c (n = 13) | — | 6–12 weeks d | Y‐BOCS, CGI/GI, HAM‐D, HAM‐A | No serious adverse events | Y‐BOCS (p = 0.001), CGI/GI (p = 0.0003), HAM‐D (p = 0.012), and HAM‐A (p = 0.017) scores improved significantly over time. |

| Pittenger et al., 19 US | RCT | Riluzole 100 mg/day + SSRI/clomipramine (n = 20) | Placebo + SSRI/clomipramine (n = 18) | 12 weeks | Y‐BOCS, HAM‐D, HAM‐A | No serious adverse events e , but nausea, poor coordination | No significant differences between the riluzole and placebo groups in Y‐BOCS, HAM‐A, and HAM‐D scores. |

| Emamzadehfard et al., 20 Iran | RCT | Riluzole 100 mg/day + fluvoxamine 100–200 mg/day f (n = 27) | Placebo + fluvoxamine 100–200 mg/day f (n = 27) | 10 weeks | Y‐BOCS | No serious adverse events | Significant differences in improvements between the riluzole and placebo groups in Y‐BOCS total (p = 0.04) and Y‐BOCS compulsion subscale scores (p = 0.03). |

| Obsessive‐compulsive disorder in children | |||||||

| Grant et al., 23 US | OLT | Riluzole increased by 10 mg every few days, with a maximum dose of 120 mg/day g (n = 6) | — | 12 weeks | CY‐BOCS, CGI‐I | No serious adverse events | Four participants showed a clear effect, with a reduction of 46% or more (overall average 39%) in CY‐BOCS scores and “Much Improved” or “Very Much Improved” on the CGI‐I. |

| Grant et al., 12 US | RCT | Riluzole 100 mg/day h , i (n = 30) | Placebo h (n = 30) | 12 weeks | CY‐BOCS, CGI‐S, CGI‐I, CGAS, RBSR, MASC, CDI | Pancreatitis, asymptomatic elevations of transaminases | No significant differences between the riluzole and placebo groups in CY‐BOCS, CGI‐S, CGI‐I, CGAS, RBSR, MASC, and CDI scores. |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | |||||||

| Mathew et al., 11 US | OLT | Riluzole 100 mg/day j (n = 18) | — | 8 weeks | HAM‐A, HAM‐D, ASI, PDSS | No serious adverse events | At the 8‐week endpoint, eight of the 15 participants that completed the intervention achieved a HAM‐A score indicating remission of anxiety. The endpoint HAM‐D and ASI scores for these 15 participants were reduced compared with baseline scores. |

Abbreviations: ASI, Anxiety Sensitivity Index; CAPS, Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; CDI, Child Depression Inventory; CGAS, Children's Global Assessment Scale; CGI/GI, Clinical Global Impression/Global Improvement item; CGI‐I, Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement; CGI‐S, Clinical Global Impressions‐Severity; CY‐BOCS, Children's Yale‐Brown Obsessive‐Compulsive Scale; HAM‐A, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HAM‐D, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MADRS, Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale; MASC, Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; OLT, open‐label trial without a control group; PCL‐S, PTSD Checklist‐Specific; PDSS, Panic Disorder Severity Scale; RBSR, Repetitive Behavior Scale‐Revised; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; SNRI, serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SRI, serotonin reuptake inhibitors; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; Y‐BOCS, Yale‐Brown Obsessive‐Compulsive Scale.

Subgroup analysis of RCT by Spangler et al. (2020). 13

Riluzole was increased to 200 mg/day for participants not demonstrating at least a 10‐point improvement on the PCL‐S at 2 weeks.

Fluvoxamine, clomipramine, escitalopram, and fluoxetine were used.

Based on initial results, the intervention duration was extended to 6 weeks, 9 weeks, and then 12 weeks.

There was an adverse event unrelated to study participation in one case.

Fluvoxamine was administered at 100 mg/day until 4 weeks after the start of the study and at 200 mg/day for weeks 5–10.

Some participants received an SSRI and other medication.

Most participants received an SSRI plus another medication.

Flexible design, starting with a low dose and increasing the dose flexibly.

The initial dose of riluzole was 50 mg/day.

3.2. Characteristics of the eight included studies

3.2.1. Posttraumatic stress disorder

We identified one RCT focused on PTSD. 18 Participants (N = 74) in that study were active‐duty military service members or veterans with PTSD symptoms that were resistant to treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). The mean age was 37.4 years in the riluzole group and 38.1 years in the placebo group, and females accounted for 14% of the riluzole group and 16% of the placebo group. Riluzole medication was started at 100 mg/day (50 mg bis in die). The dose was increased to 200 mg/day (100 mg bis in die) if the PTSD Checklist‐Specific (PCL‐S) score did not drop to 10 at 2 weeks. The treatment duration was 8 weeks. Regarding adherence to the intervention, five participants in the riluzole group dropped out of treatment because of clinical deterioration (n = 1), changed treatment plan (n = 1), family/work demands (n = 2), and moving out of the area (n = 1). In addition, three participants dropped out of the placebo group because of the clinical deterioration (n = 1) and family/work demands (n = 2). The participants that dropped out were younger, had a lower education level, and reported less than full‐time employment compared with those that did not drop out.

An intention‐to‐treat analysis 18 showed no significant differences between the riluzole and placebo groups in scores on the clinician‐administered PTSD scale (CAPS) (as a primary outcome), PCL‐S, Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM‐A), or Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS). However, a subgroup analysis focused on participants with high hyperarousal 26 demonstrated that the riluzole group (n = 20) had significantly greater reductions on the CAPS (p = 0.049, Hedge's g = −0.34) and PCL‐S hyperarousal subscale (p = 0.03, Hedge's g = −0.37) compared with the placebo group (n = 14). Regarding safety and tolerability, participants in the riluzole group reported more difficulty in concentrating than the placebo group (p = 0.03). In addition, two participants in the riluzole group had gastrointestinal symptoms, with one severe case that required emergency medical care. Furthermore, there were near‐significant differences between the two groups for greater fatigue (p = 0.06) and sleepiness (p = 0.08). The assessment of risk of bias showed the study had a low risk of bias except for “bias due to missing outcome data” (Table 2).

TABLE. 2.

Assessment of risk of bias in four randomized controlled trials.

| Author (year) | Bias arising from the randomization process | Bias due to deviations from intended interventions | Bias due to missing outcome data | Bias in measurement of the outcome | Bias in selection of the reported result | Overall risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spangler et al. 13 | Low | Low | Some | Low | Low | Low |

| Pittenger et al. 19 | Low | Low | Some | Low | Some | Some |

| Emamzadehfard et al. 20 | Low | Low | Some | Low | Low | Low |

| Grant et al. 12 | Low | Low | Some | Low | Low | Some |

3.2.2. Obsessive‐compulsive disorder in adults

We identified two RCTs and one open label trial without a control group that focused on OCD among adults. In an open label trial without a control group conducted by Coric et al. (2005), 27 participants (N = 13) were patients with OCD who had failed to respond clinically to at least 8 weeks of treatment with SSRIs and other antidepressants. Riluzole medication was started at 100 mg/day (50 mg bis in die) and maintained. The treatment duration was initially 6 weeks. Results from these participants suggested that the therapeutic effect was sustained over time, so the treatment period was extended to 9 weeks and then to 12 weeks. Regarding medication adherence, one of the 13 participants dropped out for family reasons. There were significant improvements over time in the scores for the Yale‐Brown Obsessive‐Compulsive Scale (Y‐BOCS, p = 0.001), Clinical Global Impression/Global Improvement item (CGI/GI, p = 0.0003), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM‐D, p = 0.012), and HAM‐A (p = 0.017). No serious adverse effects were reported.

Based on the findings reported by Coric et al. (2005), 27 Pittenger et al. conducted a RCT 24 involving OCD patients (N = 38) who were prescribed SSRIs/clomipramine, and who had failed at least one clinical trial of adequate‐dose SSRIs. The mean age was 41.5 years in the riluzole group and 36.4 years in the placebo group, and females accounted for 42% in the riluzole group and 50% in the placebo group. The dose of riluzole was fixed at 100 mg/day (50 mg bis in die). The treatment duration was 12 weeks. Regarding adherence to the intervention, three of the 20 participants dropped out of treatment in the riluzole group because of transportation difficulties (n = 1) and protocol violations (n = 2). None of the 18 participants in the placebo group dropped out. There were no significant differences between the riluzole and placebo groups in Y‐BOCS scores as the primary outcome, Y‐BOCS subscale scores, HAM‐A scores, and HAM‐D scores. Regarding safety and tolerability, the reported side effects were nausea (riluzole group: n = 3 vs. placebo group: n = 1), poor coordination (riluzole: n = 3 vs. placebo n = 1), constipation (riluzole: n = 1 vs. placebo: n = 6), poor memory (riluzole: n = 1 vs. placebo: n = 6), and pounding heartbeat (riluzole: n = 0 vs. placebo n = 3). The risk of bias assessment indicated that study had a low risk of bias except for “bias due to missing outcome data,” “bias in selection of the reported results,” and “overall risk of bias” (Table 2).

In another RCT by Emamzadehfard et al. (2016), 25 participants (N = 54) were patients with moderate to severe OCD. The mean age was 33.7 years in the riluzole group and 36.0 years in the placebo group, and the majority of participants were female (64% in the riluzole group and 76% in the placebo group). Participants in intervention group received 100 mg/day of riluzole (50 mg bis in die) plus fluvoxamine. Participants in the placebo group received a placebo plus fluvoxamine. In both groups, fluvoxamine was administered at 100 mg/day until 4 weeks after the start of the study and then at 200 mg/day for weeks 5–10. The treatment duration was 10 weeks. Regarding adherence to the intervention, two of the 27 participants in the riluzole group dropped out of treatment. One participant withdrew consent (reason not stated), and one participant was excluded from the study because of substance dependence. Two of the 27 participants in the placebo group dropped out of treatment because of withdrawn consent. There were significant differences in improvements between the riluzole and placebo groups in Y‐BOCS total scores (p = 0.04, Cohen's d = 0.59) and Y‐BOCS compulsion subscale scores (p = 0.03, Cohen's d = 0.64). Regarding safety and tolerability, no serious adverse events were reported. However, there were reported cases of drowsiness (riluzole group: n = 6 vs. placebo: n = 5), constipation (riluzole: n = 5 vs. placebo: n = 5), dizziness (riluzole: n = 4 vs. placebo: n = 4), abdominal pain (riluzole: n = 5 vs. placebo: n = 4), increased appetite (riluzole: n = 4 vs. placebo: n = 5), decreased appetite (riluzole: n = 3 vs. placebo: n = 4), nausea (riluzole: n = 6 vs. placebo n = 5), headache (riluzole: n = 4 vs. placebo: n = 4), dry mouth (riluzole: n = 3 vs. placebo: n = 3), cough (riluzole: n = 4 vs. placebo: n = 3), diarrhea (riluzole: n = 6 vs. placebo: n = 4), and increased liver‐function tests (riluzole: n = 1 vs. placebo: n = 0). There were no statistically significant differences in these events between the two groups. The risk of bias assessment showed the study had a low risk of bias except for “bias due to missing outcome data” (Table 2).

3.2.3. Obsessive‐compulsive disorder in children

It is possible that the effect of riluzole may be different between children and adult patients with OCD. The children's version of Yale‐Brown Obsessive‐Compulsive Scale was used to assess symptoms in children. Therefore, we distinguish the results between adult and children's outcomes for OCD in our study.

We identified one RCT and one open label trial without a control group that focused on OCD among children. In the open label trial without a control group, 28 the participants (N = 6) were children with treatment‐resistant OCD. The mean age was 14.4 years. All participants had been symptomatic for months or years, had not responded to treatment with at least one antidepressant (SSRIs), and had generally received treatment at doses that were usually effective and for a sufficient length of time. Riluzole was increased by 10 mg every few days, with a maximum dose of 120 mg. The treatment duration was 12 weeks. All six participants were taking at least 100 mg/day (50 mg bis in die) of riluzole by the end of the treatment period, except one participant whose drowsiness had worsened after the addition of riluzole. Four of the six patients showed clear effects, with a reduction of 46% or more (overall average 39%) in scores on the Children's Yale‐Brown Obsessive‐Compulsive Scale (CY‐BOCS) and were classified as “Much Improved” or “Very Much Improved” on the Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement (CGI‐I) scale. No serious adverse events were reported.

Based on the findings of the study by Grant et al. (2007), 28 Grant et al. (2014) 17 conducted a RCT involving treatment‐resistant children (N = 60) with OCD only or OCD and autism spectrum disorder. The mean age was 14.8 years in the riluzole group and 14.2 years in the placebo group, and females accounted for 27% of participants in both groups. Riluzole was started at a low dose and increased daily to a maximum dose of 100 mg/day (50 mg bis in die). The treatment duration was 12 weeks. Regarding adherence to the intervention, eight of the 30 participants in the riluzole group dropped out of treatment because of depression (n = 1), pancreatitis (n = 1), elevated transaminase levels (n = 5), and lost to follow up (n = 1). Of the 30 participants in the placebo group, one participant withdrew consent without providing an explanation. There were no significant differences between the riluzole and placebo groups in four primary outcomes (CY‐BOCS, CGI‐Severity, CGI‐Improvement, Children's Global Assessment Scale) and three secondary outcomes (Repetitive Behavior Scale‐Revised: RBSR, Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children: MASC, and Child Depression Inventory: CDI). In the riluzole group, pancreatitis (n = 1) was reported as a serious adverse event along with asymptomatic elevations of transaminases (n = 5). However, there were no statistically significant differences in any adverse events between the two groups. The risk of bias assessment showed the study had a low risk of bias except for “bias due to missing outcome data” and “overall risk of bias” (Table 2).

3.2.4. Generalized anxiety disorder

We identified one open label trial without a control group 16 that included participants (N = 18) who were patients with GAD. The mean age was 33.6 years and 67% of participants were female. The initial dose of riluzole was 50 mg/day and subsequent doses were fixed at 100 mg/day (50 mg bis in die) for the duration of the study. The treatment duration was 8 weeks. Regarding medication adherence, two participants dropped out because of dizziness and nausea (n = 1) and cognitive slowing (n = 1), and one participant was excluded from the study because of a protocol violation. At the 8‐week endpoint, eight of the 15 patients who completed the 8‐week intervention achieved a HAM‐A score indicating remission of anxiety. In addition, the endpoint HAM‐D and Anxiety Sensitivity Index scores for these 15 participants were reduced compared with baseline scores. There were no serious adverse events reported.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Overview of the eligible studies

Our systematic review summarized recent information on the efficacy and safety of riluzole for psychiatric disorders with anxiety or fear as primary symptoms. We identified one RCT focused on PTSD 18 and a subgroup analysis of that RCT, 26 two RCTs 24 , 25 and one open label trial without a control group 27 focused on OCD in adults, one RCT 17 and one open label trial without a control group 28 focused on OCD in children, and one open label trial without a control group 16 that examined GAD. Most included studies demonstrated adequate study quality. There were no trials that focused on acute stress disorder, panic disorder, or phobias.

Our systematic review identified several new trials 18 , 26 that were published after the research periods covered by the previous three systematic reviews. 19 , 20 , 29 Our study therefore provides the most recent findings on the efficacy and safety of riluzole for psychiatric disorders with anxiety or fear as primary symptoms.

4.2. Effectiveness and safety of riluzole

Most trials evaluated the efficacy of riluzole as an augmentation therapy with SSRIs and other antidepressants for PTSD, OCD, and GAD. Some trials showed the effectiveness of riluzole. However, most of them were open label trial without a control group, and only one trial 25 in four RCTs showed the effectiveness of riluzole. Therefore, there is insufficient evidence to confirm the effects of riluzole for patients with these psychiatric disorders. The molecular mechanisms of riluzole are not yet sufficiently clear, and riluzole may not act directly on N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate (NMDA) receptor.

Except for studies examining OCD in children and PTSD, riluzole was found to cause few serious adverse events. Therefore, it may safely be used for psychiatric disorders where the primary symptoms are anxiety and fear.

4.3. Challenges for novel clinical trials

D‐cycloserine and ketamine, like riluzole, are medications that act on NMDA‐type glutamate receptors. These medications have been examined for their ability to augment the effects of cognitive behavioral therapy for OCD, 30 , 31 PTSD, 32 , 33 and anxiety disorder. 34 Previous behavioral pharmacology studies involving rats and mice suggested that riluzole facilitated extinction learning of fear memories 14 and may also have inhibitory effects on fear memory reconsolidation. 15 It would therefore be worthwhile conducting a further study to examine the effects of riluzole in augmenting the benefits of psychotherapies such as exposure therapy.

4.4. Strengths and limitations

A limitation of our systematic review was the small number of studies that were identified. Therefore, no definite conclusions can be reached regarding the efficacy and safety of riluzole. In addition, seven of the eight eligible studies were conducted in the United States, showing a bias toward the country of implementation.

5. CONCLUSION

Our systematic review found insufficient evidence to confirm the effects of riluzole for psychiatric disorders with anxiety or fear as primary symptoms. It would be worthwhile to conduct further studies that incorporate novel perspectives, such as examining the efficacy of riluzole as an augmentation therapy to enhance the effectiveness of psychotherapy.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

YK was responsible for conducting this study. YK and Mitsuhiko‐Y conceptualized and planned the entire study. YK drafted the manuscript and provided administrative and technical support. All authors contributed to the study concept and design. YK, Misa‐Y, HF, HK, KA, TK, TN, and Mitsuhiko‐Y performed the review and extracted the data and information from the eligible articles. TN provided comments from a clinical perspective and all authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approval of the Research Protocol by an Institutional Reviewer Board: As this was a review of published articles, ethical approval was not required.

Informed Consent: As this was a review of published articles, the patient consent statement is not applicable.

Registry and the Registration No. of the Study/Trial: N/A.

Animal Studies: N/A.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ms. Mayumi Matsutani and Ms. Hiromi Muramatsu for their research assistance. In addition, we thank Dr. Yoshiyuki Tachibana from the National Center for Child Health and Development (Tokyo, Japan) for his helpful assistance in searching for research articles. We also thank Audrey Holmes, MA, from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript. This research was supported by KAKENHI grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (22K07630), an Intramural Research Grant (3‐1) for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders, and a TMC Young Investigator Fellowship Grant (29‐30) from the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry.

Kawashima Y, Yamada M, Furuie H, Kuniishi H, Akagi K, Kawashima T, et al. Effects of riluzole on psychiatric disorders with anxiety or fear as primary symptoms: A systematic review. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2023;43:321–328. 10.1002/npr2.12364

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sartori SB, Singewald N. Novel pharmacological targets in drug development for the treatment of anxiety and anxiety‐related disorders. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;204:107402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miller RG, Mitchell JD, Moore DH. Riluzole for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)/motor neuron disease (MND). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(3):CD001447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benoit E, Escande D. Riluzole specifically blocks inactivated Na channels in myelinated nerve fibre. Pflugers Arch. 1991;419(6):603–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kretschmer BD, Kratzer U, Schmidt WJ. Riluzole, a glutamate release inhibitor, and motor behavior. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1998;358(2):181–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mantz J, Laudenbach V, Lecharny JB, Henzel D, Desmonts JM. Riluzole, a novel antiglutamate, blocks GABA uptake by striatal synaptosomes. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;257(1–2):R7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frizzo ME, Dall'Onder LP, Dalcin KB, Souza DO. Riluzole enhances glutamate uptake in rat astrocyte cultures. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2004;24(1):123–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Doble A. The pharmacology and mechanism of action of riluzole. Neurology. 1996;47:S233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Takahashi K, Murasawa H, Yamaguchi K, Yamada M, Nakatani A, Yoshida M, et al. Riluzole rapidly attenuates hyperemotional responses in olfactory bulbectomized rats, an animal model of depression. Behav Brain Res. 2011;216(1):46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sugiyama A, Saitoh A, Iwai T, Takahashi K, Yamada M, Sasaki‐Hamada S, et al. Riluzole produces distinct anxiolytic‐like effects in rats without the adverse effects associated with benzodiazepines. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(8):2489–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thiébot MH. Some evidence for amnesic‐like effects of benzodiazepines in animals. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1985;9(1):95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Venault P, Chapouthier G, de Carvalho LP, Simiand J, Morre M, Dodd RH, et al. Benzodiazepine impairs and beta‐carboline enhances performance in learning and memory tasks. Nature. 1986;321(6073):864–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Woods JH, Katz JL, Winger G. Benzodiazepines: use, abuse, and consequences. Pharmacol Rev. 1992;44(2):151–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sasaki‐Hamada S, Sacai H, Sugiyama A, Iijima T, Saitoh A, Inagaki M, et al. Riluzole does not affect hippocampal synaptic plasticity and spatial memory, which are impaired by diazepam in rats. J Pharmacol Sci. 2013;122(3):232–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sugiyama A, Saitoh A, Inagaki M, Oka J, Yamada M. Systemic administration of riluzole enhances recognition memory and facilitates extinction of fear memory in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2015;97:322–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Akagi K, Yamada M, Saitoh A, Oka J, Yamada M. Post‐reexposure administration of riluzole attenuates the reconsolidation of conditioned fear memory in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2018;131:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mathew SJ, Amiel JM, Coplan JD, Fitterling HA, Sackeim HA, Gorman JM. Open‐label trial of riluzole in generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(12):2379–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grant PJ, Joseph LA, Farmer CA, Luckenbaugh DA, Lougee LC, Zarate CA Jr, et al. 12‐week, placebo‐controlled trial of add‐on riluzole in the treatment of childhood‐onset obsessive‐compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(6):1453–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Spangler PT, West JC, Dempsey CL, Possemato K, Bartolanzo D, Aliaga P, et al. Randomized controlled trial of riluzole augmentation for posttraumatic stress disorder: efficacy of a glutamatergic modulator for antidepressant‐resistant symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(6):20m13233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Boer JN, Vingerhoets C, Hirdes M, McAlonan GM, Amelsvoort TV, Zinkstok JR. Efficacy and tolerability of riluzole in psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and preliminary meta‐analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2019;278:294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yao R, Wang H, Yuan M, Wang G, Wu C. Efficacy and safety of riluzole for depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized placebo‐controlled trials. Psychiatry Res. 2020;284:112750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kawashima Y, Akagi K, Yamada M, Furuie H, Yamada M. Effect and safety of riluzole for patients with anxiety disorders: a systematic review. PROSPERO. 2017; CRD42017077873.

- 22. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Higgins JT, Chandler J, Cumpston M. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.2 (updated February 2021), 2021. Cochrane. [cited 2021 Apr 30]. Available from: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- 24. Pittenger C, Bloch MH, Wasylink S, Billingslea E, Simpson R, Jakubovski E, et al. Riluzole augmentation in treatment‐refractory obsessive‐compulsive disorder: a pilot randomized placebo‐controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(8):1075–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Emamzadehfard S, Kamaloo A, Paydary K, Ahmadipour A, Zeinoddini A, Ghaleiha A, et al. Riluzole in augmentation of fluvoxamine for moderate to severe obsessive‐compulsive disorder: randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;70(8):332–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. West JC, Spangler PT, Dempsey CL, Straud CL, Graham K, Thiel F, et al. Riluzole augmentation in posttraumatic stress disorder: differential treatment effect in a high hyperarousal subtype. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2021;41(4):503–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Coric V, Taskiran S, Pittenger C, Wasylink S, Mathalon DH, Valentine G, et al. Riluzole augmentation in treatment‐resistant obsessive‐compulsive disorder: an open‐label trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(5):424–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grant P, Lougee L, Hirschtritt M, Swedo SE. An open‐label trial of riluzole, a glutamate antagonist, in children with treatment‐resistant obsessive‐compulsive disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(6):761–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zarate CA, Manji HK. Riluzole in psychiatry: a systematic review of the literature. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008;4(9):1223–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rodriguez CI, Wheaton M, Zwerling J, Steinman SA, Sonnenfeld D, Galfalvy H, et al. Can exposure‐based CBT extend the effects of intravenous ketamine in obsessive‐compulsive disorder? An open‐label trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(3):408–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Leeuw AS, van Megen HJ, Kahn RS, Westenberg HG. d‐cycloserine addition to exposure sessions in the treatment of patients with obsessive‐compulsive disorder. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;40:38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. de Kleine RA, Hendriks GJ, Kusters WJ, Broekman TG, van Minnen A. A randomized placebo‐controlled trial of D‐cycloserine to enhance exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(11):962–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shiroma PR, Thuras P, Wels J, Erbes C, Kehle‐Forbes S, Polusny M. A proof‐of‐concept study of subanesthetic intravenous ketamine combined with prolonged exposure therapy among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(6):20l13406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ori R, Amos T, Bergman H, Soares‐Weiser K, Ipser JC, Stein DJ. Augmentation of cognitive and behavioural therapies (CBT) with d‐cycloserine for anxiety and related disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(5):CD007803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.