Abstract

Background

Patients with relapsed/refractory T-cell malignancies have limited treatment options. The use of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy for T-cell malignancies is challenging due to possible blast contamination of autologous T-cell products and fratricide of CAR-T cells targeting T-lineage antigens. Recently, allogeneic double-negative T cells (DNTs) have been shown to be safe as an off-the-shelf adoptive cell therapy and to be amendable for CAR transduction. Here, we explore the antitumor activity of allogeneic DNTs against T-cell malignancies and the potential of using anti-CD4-CAR (CAR4)-DNTs as adoptive cell therapy for T-cell malignancies.

Methods

Healthy donor-derived allogeneic DNTs were ex vivo expanded with or without CAR4 transduction. The antitumor activity of DNTs and CAR4-DNTs against T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) and peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) were examined using flow cytometry-based cytotoxicity assays and xenograft models. Mechanisms of action were investigated using transwell assays and blocking assays.

Results

Allogeneic DNTs induced endogenous antitumor cytotoxicity against T-ALL and PTCL in vitro, but high doses of DNTs were required to attain therapeutic effects in vivo. The potency of DNTs against T-cell malignancies was significantly enhanced by transducing DNTs with a third-generation CAR4. CAR4-DNTs were manufactured without fratricide and showed superior cytotoxicity against CD4+ T-ALL and PTCL in vitro and in vivo relative to empty-vector transduced-DNTs. CAR4-DNTs eliminated T-ALL and PTCL cell lines and primary T-ALL blasts in vitro. CAR4-DNTs effectively infiltrated tumors, delayed tumor progression, and prolonged the survival of T-ALL and PTCL xenografts. Further, pretreatment of CAR4-DNTs with PI3Kδ inhibitor idelalisib promoted memory phenotype of CAR4-DNTs and enhanced their persistence and antileukemic efficacy in vivo. Mechanistically, LFA-1, NKG2D, and perforin/granzyme B degranulation pathways were involved in the DNT-mediated and CAR4-DNT-mediated killing of T-ALL and PTCL.

Conclusions

These results demonstrate that CAR4-DNTs can effectively target T-ALL and PTCL and support allogeneic CAR4-DNTs as adoptive cell therapy for T-cell malignancies.

Keywords: receptors, chimeric antigen; immunotherapy; hematologic neoplasms; T-lymphocytes

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy is challenging for T-cell malignancies due to possible blast contamination of autologous T-cell products, alloreactivity of donor-derived cell products, and fratricide of CAR-T cells targeting T-lineage antigens.

Allogeneic double-negative T cells (DNTs) have been shown to be safe as an off-the-shelf adoptive cell therapy and to be amendable for CAR transduction. However, the potential of using allogeneic DNTs and CAR-DNTs as an adoptive cell therapy for T-cell malignancies has not been explored.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This is the first study to demonstrate that allogeneic DNTs induce endogenous antitumoral activity against T-cell malignancies in an LFA-1 and NKG2D dependent manner.

Allogeneic CD4-CAR-DNTs can be manufactured without fratricide or additional genetic modifications to more effectively target CD4+ T-cell malignancies in vitro and in xenograft models.

CAR4 enables DNTs to use perforin/granzyme B degranulation pathway in addition to the endogenous LFA-1 and NKG2D dependent mechanisms to target T-cell malignancies.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

This study supports the potential of using allogeneic CD4-CAR-DNTs as a novel treatment strategy for T-cell malignancies and opens up the opportunity of using allogeneic DNTs as a vehicle for other available CARs to target T-cell malignancies.

Background

T-cell malignancies are hematological cancers of the T-cell lineage. Among the more aggressive are T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), accounting for 15–25% of newly diagnosed ALL cases,1 and peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), representing 10–15% of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma cases.2 The current first-line therapy for T-ALL and PTCL is intensive combination chemotherapy. However, 20–40% of patients with T-ALL and more than 60% of patients with PTCL experience refractory or relapsed disease with limited second-line treatment options.2 3 Overall, the prognoses of patients with refractory/relapsed T-ALL or PTCL are dismal, with a reported median survival of 5–8 months.2 3

Recently, chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cell (CAR-T) therapies targeting B-lineage antigens have achieved significant clinical success against B-cell malignancies.4 5 Yet, for T-cell malignancies, the application of CAR-T therapies is met with several unique challenges.6 7 For autologous T-cell therapy, there is a risk of lymphoblast contamination in T-cell products.6 7 While this promotes the use of donor-derived allogeneic T cells for therapy, severe toxicities such as graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) can arise.6 8 Also, infused donor cells are subject to host-rejection by recipient immune cells. Moreover, due to the shared expression of T-lineage antigens on malignant and effector T cells,6 9 CAR-T cells engineered to target T-lineage antigens can undergo self-killing, or fratricide, during manufacture without additional gene editing to remove the targeted antigens on CAR-T cells, limiting their clinical availability.

Current approaches to avoid GvHD and host rejection in allogeneic CAR-T therapies include knocking-out endogenous T-cell receptors (TCRs), human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I molecules, and CD52 from CAR-T cells10 or by using donor-derived innate immune cells, such as natural killer (NK) cells, as a vehicle for CAR.11 Nonetheless, both approaches have major drawbacks. Introducing multiple genetic modifications is associated with the risk of off-target effects,10 a lower yield of CAR-T cell products, and a higher cost of production. Innate immune cells have been shown to lack persistence and long-term efficacy in xenograft models and patients.12

Double-negative T cells (DNTs) are a rare subset of mature T cells that express CD3 but not CD4 or CD8.13–18 DNTs comprise 3–5% of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and can be ex vivo expanded from healthy donors under clinically compliant conditions.14 We and others demonstrated that ex vivo expanded allogeneic DNTs can elicit potent anticancer effects against various cancer types.13–15 19 Unlike conventional CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, allogeneic DNTs target various cancers without off-tumor toxicities, including GvHD, and show resistance to the alloreactivity of conventional T cells (Tconv) without any genetic modifications in preclinical models.13 16 The safety and potential efficacy of allogeneic DNT therapy for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) have been demonstrated in a recent phase I clinical trial,18 in which 6 out of 10 patients with relapsed AML post allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation achieved complete remission following infusion of third-party donor-derived DNTs with no signs of GvHD or other >grade 2 treatment-associated adverse events.18 However, whether DNTs can target T-cell malignancies have not been studied previously.

DNTs are amendable for CAR-transduction, and anti-CD19-CAR-DNTs (CAR19-DNTs) elicit potent anticancer activity against B-cell malignancies comparable to that of CAR19-Tconv while maintaining their safety profile and resistance to the alloreactivity of Tconv.20 CD4 is a T-lineage marker reportedly expressed on 45–80% of T-ALL21 and PTCL.22 CD4 is an attractive candidate antigen for CAR-redirected targeting of T-cell malignancies because it is not expressed on hematopoietic stem cells, restricting the on-target and off-tumor effect of CAR to the T-lineage cells. Since DNTs lack CD4 expression, it allows for the transduction of CD4-CAR without undergoing fratricide during manufacture.

In this study, we evaluated the potential of using DNTs as an allogeneic adoptive cell therapy against T-cell malignancies by assessing the endogenous anticancer effects of DNTs and the potential of anti-CD4-CAR (CAR4)-DNTs against T-ALL and PTCL. DNTs exhibited considerable cytotoxicity against T-ALL and PTCL in vitro and in xenograft models. Further, DNTs transduced with anti-CD4-CARs (CAR4-DNTs) induced superior efficacy against T-ALL and PTCL in vitro and in xenograft models relative to empty-vector (EV)-transduced DNTs. Mechanistically, LFA-1, NKG2D, and perforin/granzyme B pathways were significantly involved in CAR4-DNT-mediated killing of T-ALL and PTCL. Collectively, these results support the use of DNTs as an off-the-shelf allogeneic CAR-T cell platform for T-cell malignancies.

Methods

Cell lines

CCRF-CEM was obtained from ATCC (American Type Culture Collection) and cultured in RPMI (Roswell Park Memorial Institute) 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). KARPAS-299 was obtained from Sigma and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 20% FBS and 2 mM Glutamine. Phoenix-GP cells were generously supplied by Dr Daniel Abate-Daga (University of South Florida). Phoenix GP cells20 were cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with L-glutamine and HEPES.

Ex vivo isolation and expansion of DNTs

DNT isolation and expansion were performed as previously described.13 14 Briefly, healthy donor-derived PBMCs were depleted of CD4+ and CD8+ cells using CD4-depletion and CD8-depletion cocktails (STEMCELL Technologies) and cultured on anti-CD3 antibody-coated plates (5 µg/mL; OKT3; Miltenyi Biotec) for 3–4 days in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and interleukin (IL)-2 (250 IU/mL; Proleukin, Novartis Pharmaceuticals). The purity of DNTs was assessed by staining cells with fluorochrome-conjugated antihuman CD3, CD4, and CD8 antibodies and flow cytometry analysis. DNTs were used for the production of EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs, 3–4 days after expansion.

CAR4 retroviral particle production

The anti-CD4 CAR construct CD4 scFv-CD28-41BB-CD3ζ CAR (CAR4) was generated in retroviral vector MSGV1, and CAR4 retroviral particles were generated as described earlier.20 Briefly, the coding sequence of a single-chain variable fragment(scFv) derived from humanized monoclonal ibalizumab and the intracellular domains of CD28 and 4-1BB co-activators fused to the CD3ζ T-cell activation signaling domain23 was cloned in the MSGV1 retroviral vector. One day before transfection, Phoenix-GP cells were split and plated on poly-D-lysine-coated plates (Corning/WVR). The DNA-Lipofectamine complex was prepared in Opti-MEM medium (Gibco) and included the RD114 envelope plasmid (Addgene) and CAR4 retroviral plasmid. The complex was then added to the plates of Phoenix-GP cells, and the first and second viral harvests were collected 48 and 72 hours after transfection, respectively. CAR4 retroviral particle harvests were pooled and stored at −80°C and then thawed for CAR4 transduction.

CAR4 transduction and expression

Transduction was performed as previously described.20 Briefly, non-tissue culture-treated plates were coated with RetroNectin (5 µg/mL; Takara). On the following day, the plates were blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin-phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), loaded with CAR4 or EV retroviral particles, and centrifuged at 3300 rpm for 2.5–3 hours at 30°C, and the supernatants were discarded. DNTs expanded for 3–4 days were resuspended at a concentration of 0.25×106 to 0.4×106 cells/mL in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, IL-2 (250 IU/mL), and anti-CD3 antibody (0.05 µg/mL; OKT3) and added to the viral loaded plates. DNTs were split on day 3 after transduction and every 3–4 days thereafter, where fresh RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, IL-2 (250 IU/mL), and soluble anti-CD3 antibody (0.1 ug/mL; OKT3) were added. DNTs were harvested 10–20 days post expansion for subsequent experiments. To evaluate the level of CAR4 expression, cells were stained with biotinylated protein L antibody (3 µg/100 µl; Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by phycoerythrin-conjugated streptavidin (2 µg/100 µl; BioLegend), and analyzed by flow cytometry.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay

Target cells were labeled with 2 µM PKH26 fluorescent dye (Sigma) according to the manufacturer’s instruction and cocultured with EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs in a 96-well plate at various effector-to-target ratios for 2 hours or 24 hours at 37°C. Subsequently, cells were stained with annexin V, and apoptosis of the target cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. Per cent specific killing was calculated using the formula: as previously described. For transwell assays, an HTS Transwell 96-well permeable support (Sigma) with 0.4 µm pore size was used. For blocking assays, anti-CD18 (TS1/18, BioLegend), NKG2D (1D11, BioLegend), DNAM-1 (DX11, BD Bioscience), TNF-α (MAb11, BioLegend), IFN-γ (MD-1, BioLegend), TRAIL (RIK-2, BioLegend), and FasL (NOK-1, BioLegend) antibodies or immunoglobulin 1 (IgG1) isotype control (QA16A12, BioLegend) was added at 10 µg/mL. For blocking assays with concanamycin A (CMA), EV-DNTs or CAR4-DNTs were treated with CMA (100 nM; Sigma) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 30 min prior to use for in vitro cytotoxicity assay.

Antibodies and flow cytometry

The following antihuman antibodies were used for cell staining: CD3-PECy7 or CD3-AF700, CD4-FITC, CD8-APC, CD45-PE, CD56-PE, iNKT TCR (Vα24-Jα18 TCR)-APC, CD45RA-FITC, CD62L-PECy7, TIM3-FITC, PD1-APC, LAG3-PECy7, HLA-A2-FITC, HLA-A3-APC, HLA-B7-PECy7, and Annexin V-FITC or Annexin V-Pacific Blue and were purchased from BioLegend. Data acquisition was performed using either a BD Accuri C6 Flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) or an Attune NXT cytometer (Thermo Fisher). Flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Xenograft models

NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were housed in the Animal Research Centre at University Health Network (UHN). Animals used for experiments were age-matched and sex-matched and housed in the same animal room. Five to 12 experimental mice per group were used and each experiment was done at least two times. The sample size was decided to determine the reproducibility and statistical significance of the findings. There was no exclusion of experimental mice.

For studies involving leukemia models, 6–12 week-old female NSG mice were sublethally irradiated (250 cGy; Gammacell 40, Theratonics) 24 hours prior to intravenous injection with 2–5×106 CCRF-CEM cells. Mice were randomly allocated to treatment groups. On days 3, 7, and 10 after CCRF-CEM infusion, mice were intravenously treated with various dosages of EV-DNTs, CAR4-DNTs, or PBS. Since human DNTs require IL-2 for survival and function but do not produce IL-2, mice received 104 IU recombinant IL-2 (Proleukin) intraperitoneally at the times of T-cell infusion and once a week until the end of the experiments. For survival studies, mice were sacrificed when they reached the humane endpoint of 20% loss in original body weight. Mouse tissues, including the bone marrow, spleen, liver, lungs, and peripheral blood, were harvested. Liver and lung tissues were digested with collagenase D at 37°C for 30 min, filtered through a 40 µm cell strainer, and centrifuged with Ficoll-paque density gradient at 1200×g for 20 min. Subsequently, the mononuclear cell layer was collected. All mouse tissues were stained with various antihuman antibodies to examine T-ALL engraftment and CAR4-DNT persistence by flow cytometry.

For studies involving lymphoma models, 6–12 weeks old male NSG mice were sublethally irradiated 24 hours prior to subcutaneous inoculation with 5×105 KARPAS-299 cells in a solution of 50% Matrigel (Corning). Mice were randomly allocated to treatment groups. On days 7, 10, and 13 after KARPAS-299 injection, mice were treated with peritumoral injections of 5×106 CAR+ CAR4-DNTs, an equivalent number of EV-DNTs, or PBS. Mice received 104 IU recombinant IL-2 intraperitoneally at the times of T-cell infusion and two times a week until the end of the experiments. Tumor volume was measured using a digital caliper and calculated using the formula: ½ × (length × width2). Measurements were conducted in a blinded manner. For survival studies, mice were sacrificed when they reached the humane endpoint of 1.7 cm3 in tumor volume. For investigation of T-cell infiltration into tumors, mice were sacrificed on days 17, 22 or 30 after KARPAS-299 injection. Excised tumors were digested with collagenase D at 37°C for 15 min. Tumor samples were stained with various antihuman antibodies to identify CAR4-DNT infiltration by flow cytometry.

Mouse sickness scoring

Mouse health was monitored and scored based on the sickness criteria used by the UHN animal facility (online supplemental table S2).

jitc-2023-007277supp001.pdf (2.4MB, pdf)

Mouse tissue fixing, staining, and imaging

Sections of mouse liver tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin at the time of sacrifice. Fixed tissues were sent to the STTARR Pathology Laboratory at UHN for H&E staining. H&E-stained slides were imaged at the Advanced Optical Microscopy Facility (AOMF) imaging facility at UHN. Image files were viewed and analyzed using QuPath software V.0.4.3.

Human samples

Human blood was collected from healthy adult donors and patients with T-ALL.

Statistical analysis

All graphs and statistical analyses were generated using GraphPad Prism V.9 (GraphPad Software). Data in Results were expressed as means and SD or SEM, and error bars represent±SD or SEM, as indicated. Two-tailed unpaired or paired Student’s t-test, one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with multiple comparisons post-test, or two-way ANOVAs with multiple comparisons post-test were performed where applicable. For survival studies, a log-rank test was used. ns, not significant; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****, p<0.0001.

Results

DNTs have endogenous cytotoxicity against T-ALL and PTCL

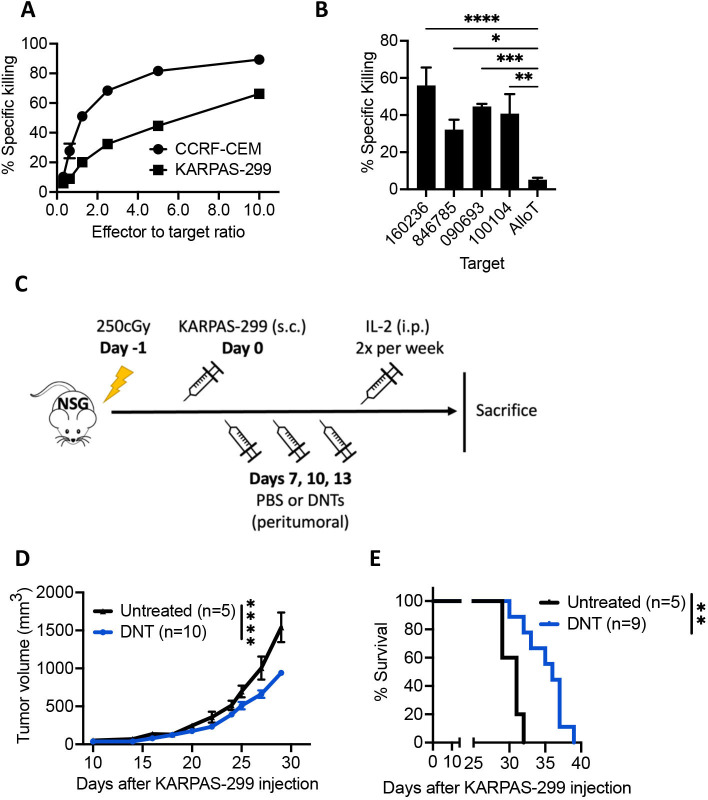

DNTs effectively and selectively target AML blasts in vitro and in vivo.13 14 However, the cytotoxicity of DNTs towards T-cell malignancies has not been investigated previously. To evaluate the potential of using allogeneic DNTs as a new therapy for T-ALL and PTCL, we isolated and expanded DNTs from healthy donors using our previously developed protocols13 14 (online supplemental figure S1). To determine the antileukemic activity of DNTs against T-cell malignancies, DNTs were cocultured overnight with a T-ALL cell line, CCRF-CEM, a PTCL cell line, KARPAS-299, and primary T-ALL blasts from four patients. DNTs showed considerable cytotoxicity against both CCRF-CEM and KARPAS-299 in a dose-dependent manner (figure 1A). Furthermore, DNTs exhibited potent cytotoxicity against all four primary T-ALL blasts tested but spared normal allogeneic T cells (figure 1B; patient with T-ALL characteristics are shown in online supplemental table S1).

Figure 1.

DNTs have endogenous cytotoxicity against T-ALL and PTCL. (A) DNTs were cocultured with T-ALL cell line, CCRF-CEM (circles), and PTCL cell line, KARPAS-299 (squares), overnight at indicated effector-to-target ratios. Per cent specific killing of the target is shown. Dots represent mean per cent specific killing of triplicates and error bars represent SD. The experiment was independently performed three times, and representative data are shown. (B) DNTs were cocultured overnight with primary T-ALL blasts from four patients or normal allogeneic T cells obtained from healthy donors (AlloT) at a 4:1 effector-to-target ratio. Each experiment was done in technical duplicates using DNTs obtained from two different donors. Column bars represent mean per cent specific killing of each target and error bars represent SEM. Numbers on the x-axis represent patient sample identifications. One-way ANOVA Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used for statistical analysis. (C) Schematic outline of in vivo experiments. NSG mice were sublethally irradiated (250 cGy) on day −1 and subcutaneously (s.c.) injected with 5×105 KARPAS-299 cells on day 0. On days 7, 10, and 13, mice received PBS or 2x107 DNTs via peritumoral injections. All mice received intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of IL-2 two times a week. (D) Mean tumor volumes of KARPAS-299-engrafted mice treated with PBS (black, n=5) or DNTs (blue, n=10) are shown. Error bars represent SEM. Two-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. (E) Kaplan-Meier curve showing the per cent survival of KARPAS-299-engrafted mice treated with PBS (black, n=5) or 2x107 DNTs (blue, n=9). Log-rank test was used for statistical analysis. *p<0.05; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001. ANOVA, analysis of variance; DNTs, double-negative T cells; IL, interleukin; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; T-ALL, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia

To examine the ability of DNTs to target T-cell malignancies in vivo, a PTCL xenograft model was established by subcutaneously infusing 5×105 KARPAS-299 cells into NSG mice. Once palpable tumors were formed, mice were treated with three infusions of PBS or 2×107 DNTs peritumorally on days 7, 10 and 13 (figure 1C). Treatment with DNTs significantly delayed the tumor growth and improved the survival of the lymphoma-bearing mice (figure 1D,E). Together, these results demonstrate that DNTs have endogenous antitumoral activity against T-cell malignancies in vitro and in vivo. However, DNTs were unable to completely eliminate T-ALL and PTCL cell lines and primary T-ALL blasts in vitro after overnight incubation. Moreover, high doses of DNTs were used to attain therapeutic effect against T-cell tumors in vivo. These results suggest the need to further improve the potency of the anticancer activity of DNTs against T-cell malignancies.

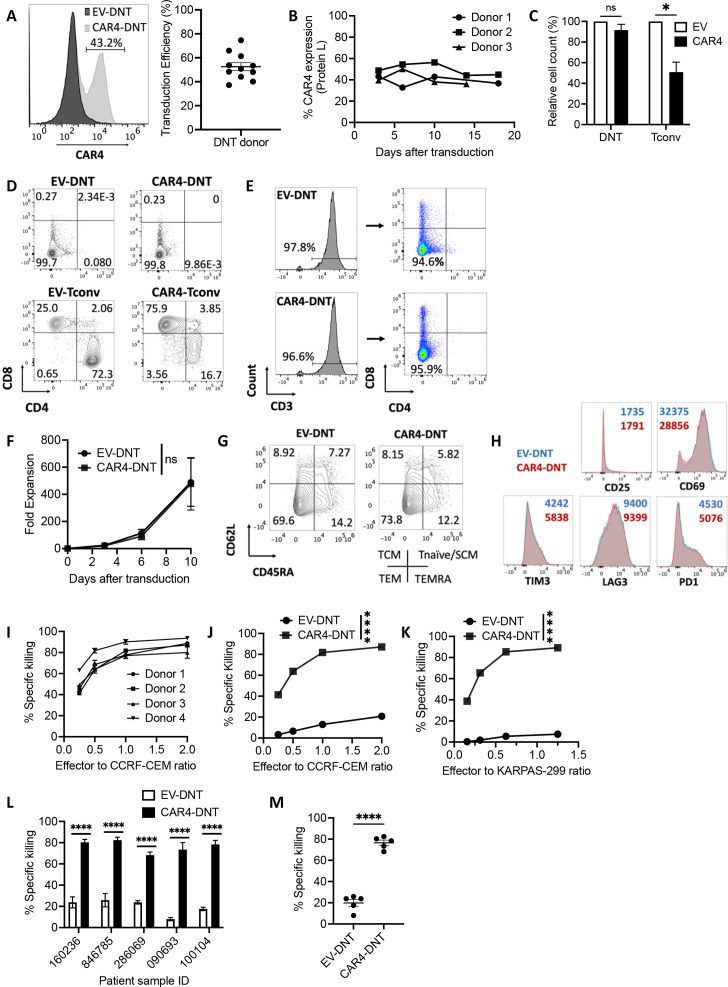

CAR4-DNTs are superior to non-transduced DNTs at targeting T-ALL and PTCL in vitro

To improve the potency of DNTs against CD4+ T-cell cancers, we developed anti-CD4-CAR-DNTs (CAR4-DNTs). Healthy donor-derived DNTs were transduced with a retroviral vector expressing a third generation CD4 scFv-CD28-41BB-CD3ζ CAR (CAR4). An average transduction efficiency of 52.54±3.37% was achieved with DNTs obtained from 11 healthy donors (figure 2A), and CAR4 expression was maintained on DNTs until at least 18 days after transduction (figure 2B). To compare the degree of fratricide, DNTs and Tconv were transduced with CAR4 or EV control. After the transduction, a significantly lower total cell number and frequency of CD4+ cells were obtained from CAR4-Tconv culture than that of EV-Tconv (figure 2C,D, online supplemental figure S2). In contrast, CAR4-DNTs maintained CD4−CD8− phenotype and showed a comparable cell count to EV-DNTs (figure 2C,D, online supplemental figure S2), supporting that CAR4-DNTs can be manufactured without fratricide. To compare the expansion profile, EV-DNTs, CAR4-DNTs, EV-Tconv, and CAR4-Tconv were expanded for 10 days after transduction. EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs showed similar fold expansion and yield, whereas CAR4-Tconv showed a lower fold expansion and yield compared with EV-Tconv (online supplemental figure S3). CAR4-DNTs showed a higher fold expansion and a similar yield per milliliter of blood compared with CAR4-Tconv (online supplemental figure S3).

Figure 2.

CAR4-DNTs are able to target CD4+ T-ALL and PTCL in vitro. (A) Donor-derived DNTs were transduced with a retroviral vector expressing CAR4 or an EV control. Three days after transduction, the expression of CAR4 on DNTs was measured by protein L. Left: Representative histogram showing the protein L staining on EV-DNTs (black) and CAR4-DNTs (gray). Right: Summary of CAR4 expression level on CAR4-DNTs from 11 independent experiments. Each dot represents transduction efficiency of DNTs from an individual donor. Horizontal line represents the mean, and error bars represent SEM. (B) Expression of CAR4 measured on DNTs over the course of 18 days after transduction (n=3) from three independent experiments. (C–D) DNTs and Tconv derived from the same donors (n=3) were transduced with EV and CAR4. Four days after transduction, cell counts and expression of CD4 and CD8 on transduced T cells were measured by flow cytometry. (C) Bar graphs showing cell counts of CAR4-DNTs and CAR4-Tconv relative to their EV-transduced counterparts. Error bars represent SEM. Two-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis. (D) Representative flow plots showing the frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells within each transduced T-cell population. (E) Ex vivo expanded EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs were stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD4, and anti-CD8 antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. (F) EV-DNTs or CAR4-DNTs were expanded for 10 days (n=4) in four independent experiments. Mean fold expansion for EV-DNTs (circles) or CAR4-DNTs (squares). Error bars represent SEM. Two-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. (G) Memory status of EV-DNTs (left) and CAR4-DNTs (right) expanded from the same donor on day 10 after transduction. Cells were stained with CD45RA and CD62L. Flow plots are representative of three independent experiments. (H) Expression of activation and exhaustion markers, CD25, CD69, TIM3, LAG3, and PD1, on the surface of EV-DNTs or CAR4-DNTs on day 14 after transduction. Histograms are representative of three independent experiments, and numbers represent mean fluorescence intensity. (I) CAR4-DNTs from four different donors were cocultured with CCRF-CEM for 2 hours at indicated effector-to-target ratios. Per cent specific killing of the target is shown. Symbols represent mean per cent specific killing of triplicates, and error bars represent SD. (J and K) EV-DNTs (circles) or CAR4-DNTs (squares) were cocultured with T-ALL cell line, CCRF-CEM (J), or PTCL cell line, KARPAS-299 (K), for 2 hours at indicated effector-to-target ratios. Per cent specific killing of the target is shown. The experiment was independently performed seven (J) or three (K) times each with triplicates, and representative data are shown. Two-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. (L) EV-DNTs (white bars) and CAR4-DNTs (black bars) were cocultured with five primary T-ALL blasts for 2 hours at a 2:1 effector-to-target ratio. Per cent specific killing of T-ALL blasts is shown. Data represent mean per cent specific killing of the target using DNTs obtained from two different donors. Each experiment was done in technical duplicates. Error bars represent SEM. Numbers on the x-axis represent patient sample identifications. Two-way ANOVA Sidak’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis. (M) Comparison of specific killing of the five primary T-ALL samples by EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs. Dots represent per cent specific killing, horizontal lines represent the mean, and the error bars represent SEM. Paired t-test was used for statistical analysis. *p<0.05; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001. ANOVA, analysis of variance; CAR4, CD4-CAR; DNTs, double-negative T cells; EV, empty-vector; PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; T-ALL, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; TCM, central memory T cell; Tconv, conventional T cells; TEM, memory T cells; TEMRA, terminally differentiated effector memory T cells; Tnaïve/SCM, naïve/stem cell memory T cell.

To see if CAR4-transduction changed the nature of DNTs, phenotype and expansion profile of CAR4-DNTs were determined relative to EV-DNTs. CAR4-DNTs retained similar phenotype (figure 2E), expansion kinetics (figure 2F), and memory status (figure 2G) as EV-DNTs during the 2 weeks of expansion. In addition, CAR4-DNTs and EV-DNTs expressed similar levels of exhaustion markers, TIM3, LAG3, and PD1, (figure 2H) during expansion, indicating no signs of DNT exhaustion due to the tonic signals from the CAR.

To evaluate the potency of the antileukemic activity of CAR4-DNTs, CAR4-DNTs from four different donors were cocultured with CCRF-CEM at varying effector-to-target ratios. CAR4-DNTs derived from different donors showed a similar dose-dependent killing of the leukemia target (figure 2I). CAR4-DNTs and CAR4-Tconv derived from the same donor showed similar levels of cytotoxicity against CCRF-CEM (online supplemental figure S4). To further determine the ability of CAR4-DNTs against different T cell leukemia targets, EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs were cocultured with CD4+ T-ALL cell line, CCRF-CEM, CD4+ PTCL cell line, KARPAS-299, and CD4+ primary T-ALL blasts from five patients. CAR4-DNTs showed superior cytotoxicity against CCRF-CEM, KARPAS-299, and all five primary T-ALL blasts compared with EV-DNTs (figure 2J–L). After a 2-hour incubation, the average specific killing across the five primary T-ALL blasts was 76.53±2.00% by CAR4-DNTs compared with 19.78±2.14% by EV-DNTs (figure 2M).

To assess off-tumor toxicity, EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs were cocultured with normal allogeneic PBMCs containing CD4+ and CD4− cells. Compared with EV-DNTs, CAR4-DNTs induced a higher level of cytotoxicity against normal CD4+ cells, but not against normal CD4− cells (online supplemental figure S5), showing that CAR4-DNTs selectively target CD4+ cells. Collectively, these results demonstrate that DNTs can be successfully transduced with CAR4 to better target CD4+ T-ALL and PTCL in vitro.

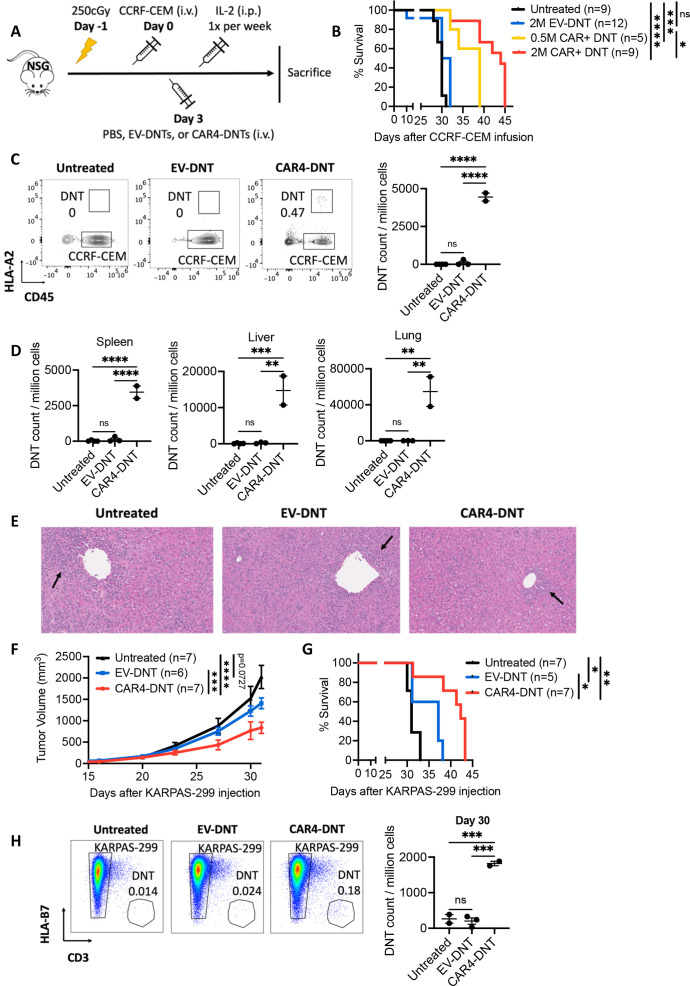

CAR4-DNTs can effectively target T-ALL and PTCL in xenograft models

In light of the potency of CAR4-DNTs against T-cell malignancies in vitro, we next investigated the efficacy of CAR4-DNTs against T-ALL and PTCL in vivo. To assess the efficacy of CAR4-DNTs against T-ALL in vivo, a previously reported xenograft model of disseminated T-ALL24–26 was used. Briefly, NSG mice were intravenously administered with 2–5×105 CCRF-CEM cells, and subsequently treated systemically with a single dose of PBS, 0.5×106 or 2×106 CAR4-DNTs, or the equivalent number of EV-DNTs (figure 3A). At this reduced cell dose, EV-DNTs failed to prolong the survival of the leukemia-bearing mice. In contrast, treatment with CAR4-DNTs significantly improved the survival of the leukemia-bearing mice in a dose-dependent manner compared with PBS and EV-DNT treated mice (figure 3B). CCRF-CEM mice treated with one dose versus three doses of 2×106 CAR4-DNTs achieved similar survival (online supplemental figure S6).

Figure 3.

CAR4-DNTs can target CD4+ T-ALL and PTCL in xenograft models. (A) Schematic outline of in vivo experiments. NSG mice were sublethally irradiated (250 cGy) on day −1 and intravenously (i.v.) injected with 2–5×105 CCRF-CEM cells on day 0. On days 3, mice were i.v. treated with PBS or various dosages of EV-DNTs or CAR4-DNTs. All mice received intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of IL-2 one time per week. Mice were sacrificed when they reached the end point of the survival experiment. (B) Kaplan-Meier curve showing the per cent survival of CCRF-CEM-engrafted mice treated with PBS (black, n=9), 0.5×106 (yellow, n=5), 2×106 (red, n=9) CAR+ CAR4-DNTs, or 2×106 EV-DNTs (blue, n=12). Data are summary of three independently performed experiments. Log-rank test was used for statistical analysis. (C) CCRF-CEM engrafted mice were sacrificed on day 32 and bone marrow was examined. DNTs were identified via staining with anti-CD45 and anti-HLA-A2 antibody. Left: Representative flow plots for CD45 and HLA-A2 staining of bone marrow cells from untreated, EV-DNT-treated, and CAR4-DNT-treated mice on day 32. CCRF-CEM cells are HLA-A2−; an HLA-A2+ donor was used to manufacture EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs. Right: Number of DNTs detected by flow cytometry on day 32. Each dot represents the DNT count per million cells in the bone marrow of one mouse, horizontal line represents the mean, and error bar represents SEM. One-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis. (D) Number of DNTs in the spleen, liver, and lungs of CCRF-CEM engrafted mice on day 32 as detected by flow cytometry. Each dot represents the DNT count per million cells in the spleen (left), liver (middle), or lung (right) of one mouse, horizontal line represents the mean, and error bar represents SEM. One-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis. (E) Representative images (×20 magnification) of H&E-stained slides of liver sections taken from CCRF-CEM engrafted mice in PBS (left), EV-DNT (middle), or CAR4-DNT (right) treatment group (n=2 per group) at the endpoint of the experiment, showing tissue histology and lymphocytic blast infiltration (black arrow). (F) Tumor volume of KARPAS-299-engrafted mice treated with PBS (black, n=7), CAR4-DNTs (red, n=7), or EV-DNTs (blue, n=6). Dots represent mean tumor volume and error bars represent SEM. Two-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis. (G) Kaplan-Meier curve showing the per cent survival of KARPAS-299-engrafted mice treated with PBS (black, n=7), CAR4-DNTs (red, n=7), or EV-DNTs (blue, n=5). Log-rank test was used for statistical analysis. (H) KARPAS-299 engrafted mice were sacrificed on day 30. Tumors were excised and KARPAS-299 cells were identified via staining with anti-HLA-B7 antibody. Left: Representative flow plots for CD3 and HLA-B7 staining of tumor samples from untreated, EV-DNT-treated, and CAR4-DNT-treated mice on day 30. KARPAS-299 cells are HLA-B7+; an HLA-B7− donor was used to manufacture EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs. Right: Number of DNTs detected by flow cytometry on day 30. Each dot represents the DNT count in the tumor sample of one mouse, horizontal line represents the mean, and error bar represents SEM. One-way ANOVA Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001. ANOVA, analysis of variance; CAR4, CD4-CAR; DNTs, double-negative T cells; EV, empty-vector; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; IL, interleukin; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; T-ALL, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

To examine the ability of CAR4-DNTs to infiltrate organs in disseminated T-ALL, the number of infiltrating DNTs was measured in the bone marrow, spleen, liver, and lungs of the leukemia-bearing mice on day 32. A mismatched HLA, HLA-A2, between CCRF-CEM and DNTs was used to identify DNTs (online supplemental figure S7). CAR4-DNTs were detected in all organs examined while EV-DNTs were not detected (figure 3C,D), suggesting that CAR4-DNTs can better infiltrate organs and persist to target T-ALL compared with EV-DNTs.

To assess the safety of CAR4-DNTs, the body weight change and health condition of the leukemia-bearing mice were monitored. Health condition was scored based on weight loss, posture, activity loss, fur loss, scruffiness, and skin loss according to mouse sickness criteria (online supplemental table S2). Untreated and EV-DNT-treated mice showed comparable trends of body weight loss and sickness scores (online supplemental figures S8 and S9). CAR4-DNT-treated mice had significantly delayed body weight loss and change in sickness scores, suggesting that the treatment delayed leukemia progression (online supplemental figures S8 and S9). At the humane endpoint, the liver of the leukemia-bearing mice was examined by histology and flow cytometry. A mismatched HLA, HLA-B27, between CCRF-CEM and DNTs was used to distinguish the cells (online supplemental figure S10). H&E staining showed lymphocytic blast infiltration in the liver for all treatment groups, among which CAR4-DNT-treated mice showed the least amount of blast infiltration (figure 3E). This is consistent with the flow cytometry data, where CCRF blasts were detected in the liver for all treatment groups (online supplemental figure S11). No signs of tissue damage were observed in the liver histology of any treatment groups (figure 3E).

Next, to determine the ability of CAR4-DNTs to target PTCL in vivo, KARPAS-299-engrafted mice were treated peritumorally with three doses of PBS, 5×106 CAR4-DNTs, or an equivalent number of EV-DNTs, according to the schedule shown in figure 1C. While EV-DNTs moderately alleviated tumor burden and improved survival compared with PBS, CAR4-DNTs conferred superior delay in tumor growth and significantly extended the survival of the lymphoma-bearing mice compared with both PBS and EV-DNT treated group. (figure 3F,G).

In order to investigate the ability of CAR4-DNTs to infiltrate tumors, tumors were excised from lymphoma-bearing mice on various days and the number of tumor infiltrating DNTs was measured. Mismatched HLA, HLA-B7, between KARPAS-299 and DNTs was used to identify DNTs (online supplemental figure S12). CAR4-DNTs were detectable in the tumors on days 17, 22 (online supplemental figure S13) and 30 (figure 3H), while EV-DNTs were not detected.

To evaluate the safety of CAR4-DNTs, the body weight and health condition of the lymphoma-bearing mice were monitored. For all treatment groups, the body weight (online supplemental figure S14) and health condition (online supplemental figure S15) remained stable throughout the experiment, suggesting that infusion of CAR4-DNTs is safe as shown in CAR19-DNTs.20 Together, these results demonstrate that CAR4-DNTs can effectively and safely target T-ALL and PTCL in vivo and exhibit better tumor infiltration and persistence compared with EV-DNTs.

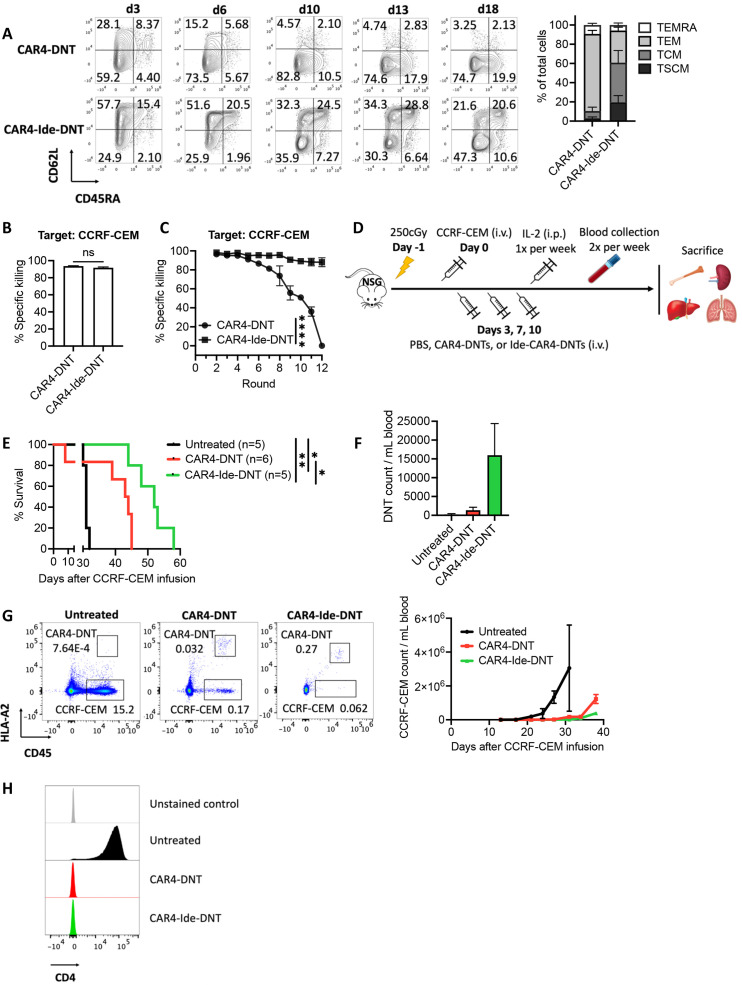

PI3Kδ inhibitor can further improve the persistence and function of CAR4-DNTs in vitro and in vivo in T-ALL model

Exhaustion and limited persistence of CAR-T cells are major issues that hinder the therapeutic effects of CAR-T cells. Here, the effect of CAR4-DNTs on T cell tumor growth was significant but limited (figure 3B and D). PI3Kδ inhibitor, idelalisib (Ide), has previously been shown to enhance the memory phenotype, in vivo persistence, and antileukemic activity of DNTs against AML cells,17 but its effect on CAR-DNT is not known. With the aim to improve the in vivo function of CAR4-DNTs, we assessed the effect of Ide on CAR4-DNTs. During the production of CAR4-DNTs, culture media were supplemented with Ide (CAR4-Ide-DNT). The memory status of CAR4-Ide-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs were compared. During 2 weeks of expansion, higher frequencies of central memory T cell (TCM; CD45RA− CD62L+) and naïve/stem cell memory T cell (Tnaïve/SCM; CD45RA+ CD62L+) were observed in CAR4-Ide-DNTs. In contrast, effector memory T cells (TEM; CD45RA− CD62L−) were the dominant phenotype in CAR4-DNTs with an increased frequency of terminally differentiated effector memory T cells (TEMRA; CD45RA+ CD62L−) (figure 4A).

Figure 4.

PI3K inhibitor can further improve the persistence and function of CAR4-DNTs in vitro and in the T-ALL xenograft model. (A) Left: Representative flow plots showing the memory status of CAR4-DNTs and CAR4-Ide-DNTs obtained and expanded from the same donor over the course of 18 days after transduction. Cells were stained with CD45RA and CD62L. Right: Summary bar graph of memory phenotype of CAR4-DNTs and CAR4-Ide-DNTs on day 13 post transduction. Error bars represent SEM. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (B) CAR4-DNTs or CAR4-Ide-DNTs were cocultured with T-ALL cell line, CCRF-CEM, for 2 hours at a 1:1 effector-to-target ratio. Per cent specific killing of the target is shown. Bars represent mean of technical triplicates, and error bars represent SEM. The experiment was independently performed two times, and representative data are shown. Two-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. (C) CAR4-DNTs (circles) and CAR4-Ide-DNTs (squares) were cocultured with CCRF-CEM at a 4:1 effector-to-target ratio. Every 24 hours following coculture, per cent specific killing of the target was measured, and fresh target cells were added to the coculture at the original effector-to-target ratio. Mean per cent specific killing of triplicates are shown and error bars represent SEM. The experiment was independently performed two times, and representative data are shown. (D) Schematic outline of experiments. NSG mice were sublethally irradiated (250 cGy) on day −1 and intravenously (i.v.) injected with 2–5×105 CCRF-CEM cells on day 0. On days 3, 7, and 10, mice were intravenously treated with PBS, or 2×106 CAR+ CAR4-DNTs or CAR4-Ide-DNTs. All mice received intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of IL-2 once per week. Mice were sacrificed when they reached the end point of the survival experiment, and cells were harvested from the bone marrow, spleen, liver, and lungs. Human cells were identified via staining with anti-CD45 antibody. HLA-A2 antibody was used to distinguish between CCRF-CEM cells and donor DNTs; CCRF-CEM cells are HLA-A2− and donor DNTs are HLA-A2+. (E) Kaplan-Meier curve showing the per cent survival of CCRF-CEM-engrafted mice treated with PBS (black, n=5), CAR4-DNTs (red, n=6), CAR4-Ide-DNTs (green, n=5). Data are representative of two independently performed experiments. Log-rank test was used for statistical analysis. (F) DNT cell counts in the peripheral blood of mice 7 days after the last infusion with PBS, CAR4-DNTs and CAR4-Ide-DNTs (n=3–4 for each treatment group). Column bars represent mean DNT cell count per milliliter of blood of mice, and error bars represent SEM. (G) Left: Representative flow plots for HLA-A2 and CD45 staining of blood cells from untreated, CAR4-DNT-treated, and CAR4-Ide-DNT-treated mice 26 days after CCRF-CEM engraftment. Right: CCRF-CEM cell counts in the peripheral blood of mice after treatment with PBS, CAR4-DNTs and Ide-CAR4-DNTs (n=3–4 for each treatment group). Each dot represents mean CCRF-CEM cell count per milliliter of blood of mice on each day after CCRF-CEM infusion and the error bars represent SEM. (H) Representative histograms showing CD4 staining of CCRF-CEM cells harvested from tissues from untreated, EV-DNT-treated, CAR4-DNT-treated, and CAR4-Ide-DNT-treated mice at the end point of the survival experiment. **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001. ANOVA, analysis of variance; CAR4, CD4-CAR; DNTs, double-negative T cells; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; Ide, idelalisib; IL, interleukin; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; T-ALL, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; TCM, central memory T cell; TEM, memory T cells; TEMRA, terminally differentiated effector memory T cells; Tnaïve/SCM, naïve/stem cell memory T cell.

CAR4-DNTs and CAR4-Ide-DNTs mediated similar levels of cytotoxicity against the targets (figure 4B), demonstrating that Ide does not affect their cytotoxic activities. To mimic in vivo prolonged tumor antigen exposure, the ability of CAR4-DNTs and CAR4-Ide-DNTs to target CCRF-CEM cells on repeated exposures was assessed by adding fresh CCRF-CEM cells every 24 hours to CAR4-DNT or CAR4-Ide-DNT culture. CAR4-Ide-DNTs maintained the ability to specifically kill more than 88% CCRF-CEM cells for at least 12 rounds of tumor stimulation, whereas specific killing by CAR4-DNTs started to significantly decline after five rounds and showed negligible killing against CCRF-CEM cells added on the 12th round (figure 4C). Prior to the last round of CCRF-CEM exposure, a higher number of persisting CAR4-Ide-DNTs was found in the culture compared with CAR4-DNTs (online supplemental figure S16). These results suggest that CAR4-Ide-DNTs can mediate a more durable response against T-ALL cells with continuous exposure to the tumor.

To evaluate the in vivo potency of CAR4-Ide-DNTs, CCRF-CEM-engrafted NSG mice were treated with three doses of PBS, CAR4-DNTs, or CAR4-Ide-DNTs (figure 4D). Treatment with CAR4-Ide-DNTs significantly improved the survival of mice relative to untreated and CAR4-DNT treated mice (figure 4E). In the peripheral blood, CAR4-Ide-DNT-treated mice showed higher levels of DNT counts and reduced CCRF-CEM cell counts compared with untreated and CAR4-DNT-treated mice after CCRF-CEM infusion (figure 4F and G).

To further compare antileukemic efficacy, CCRF-CEM-engrafted mice were treated with CAR4-Ide-DNTs or CAR4-Ide-Tconv derived from the same donor according to the schedule depicted in figure 4D. Both CAR4-Ide-DNTs and CAR4-Ide-Tconv reduced leukemic load (online supplemental figure S17) and prolonged the survival (online supplemental figure S18) of leukemia bearing mice to a similar degree compared with untreated mice. However, CAR4-Ide-Tconv-treated mice showed possible signs of acute GvHD 10 days post CAR-T cell infusion, as evident by greater body weight loss and higher sickness scores compared with untreated and CAR4-Ide-DNT groups (online supplemental figure S19).

At the humane endpoint, leukemic cells were detected in the bone marrow, spleen, liver, and lungs for all treatment groups. Unlike the untreated mice, CD4-negative CCRF-CEM cells were detected in both CAR4-DNT-treated and CAR4-Ide-DNT-treated mice (figure 4H), suggesting a CD4 downregulation in CCRF-CEM cells after encountering CAR4-DNTs. When CD4+ and CD4− CCRF-CEM cells were harvested from mice and cocultured with fresh EV-DNTs or CAR4-DNTs, a high degree of cytotoxicity toward CD4+ CCRF-CEM cells, and a low degree of cytotoxicity toward CD4− CCRF-CEM cells were observed in CAR4-DNT cocultures (online supplemental figure S20). CAR4-DNTs and EV-DNTs elicited low but comparable levels of cytotoxicity against CD4− CCRF-CEM cells (online supplemental figure S20), suggesting that CD4− CCRF-CEM cells remain susceptible to endogenous DNT cytotoxicity but are resistant to CAR4-mediated effects. Combined, these results demonstrated that the in vivo function of CAR4-DNTs can be improved by Ide and that T-ALL cells can evade CAR4-mediated immunity through antigen escape.

CAR4-DNTs target T-cell malignancies through LFA-1, NKG2D, and perforin/granzyme B degranulation pathway

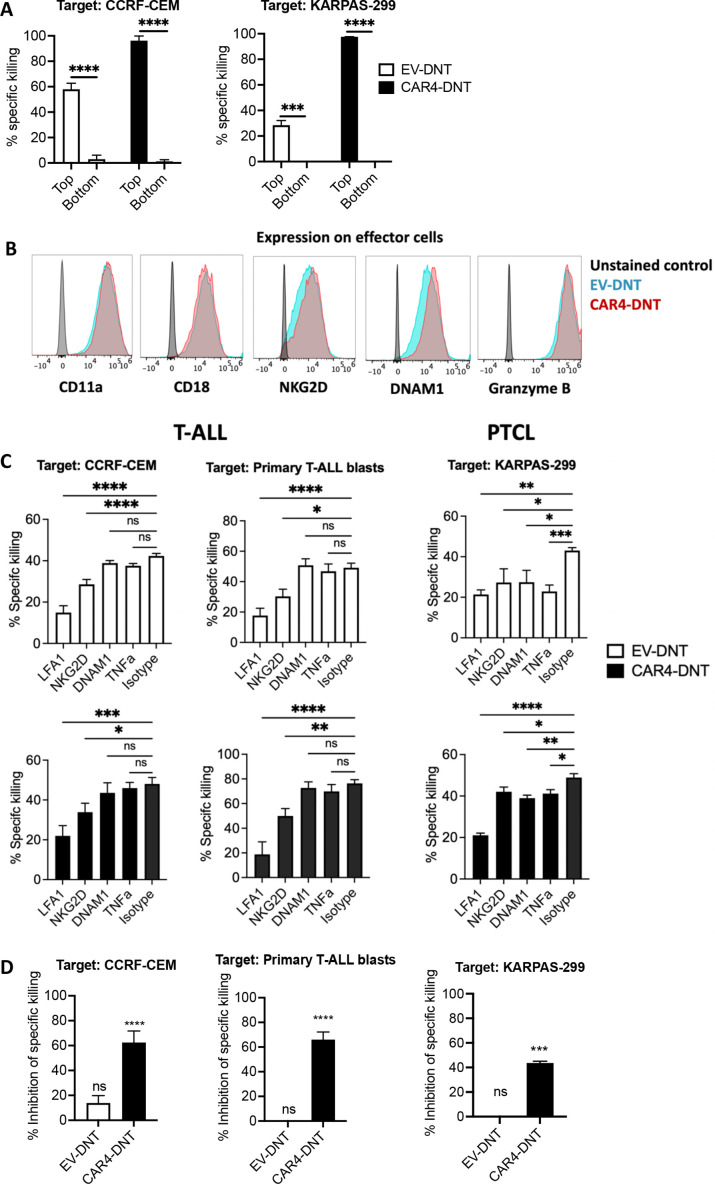

To elucidate the mechanisms involved in EV-DNT-mediated and CAR4-DNT-mediated killing of T-cell malignancies, we first determined the importance of direct contact between EV-DNTs or CAR4-DNTs and T-ALL and PTCL through transwell assays. CCRF-CEM and KARPAS-299 were cocultured with EV-DNTs or CAR4-DNTs in the top compartment, and tumor cells alone were in the bottom compartment. While EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs effectively killed CCRF-CEM and KARPAS-299 in the top compartment, no significant killing of either target was shown in the bottom compartment relative to controls with only media in the top compartment and target cells in the bottom compartment (figure 5A). This indicates that EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs induce cytotoxicity against T-ALL and PTCL largely in a contact-dependent manner.

Figure 5.

Molecular mechanism involved in EV-DNT-mediated and CAR4-DNT-mediated killing of T-cell malignancies. (A) An in vitro transwell assay was conducted with a 0.4 µm pore membrane that separates the top and bottom compartments. The target cells, CCRF-CEM and KARPAS-299, were cocultured with EV-DNTs (white bars) and CAR4-DNTs (black bars) in the top compartment, while only target cells were alone in the bottom compartment. Per cent specific killing of the target in each compartment is shown, and error bars represent SEM. The experiment was independently performed two times, and representative data are shown. Two-way ANOVA Sidak’s multiple comparison test was used for statistical analysis. (B) Representative flow plots showing expression of LFA-1 subunits, CD11a and CD18, NKG2D, DNAM-1, and granzyme B on EV-DNTs (blue) and CAR4-DNTs (red). Histograms are representative of two independent experiments. (C) An in vitro cytotoxicity assay was conducted using EV-DNTs (white bars) and CAR4-DNTs (black bars) against CCRF-CEM, primary T-ALL blasts, and KARPAS-299, in the presence of LFA-1, NKG2D, DNAM-1, or TNF-α blocking antibody, or isotype controls. EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs were cocultured with the targets for 24 hours. The effector-to-target ratio was 2:1 or 4:1 for EV-DNT cocultures and 0.2:1 for CAR4-DNT cocultures. Per cent specific killing of the target in the presence of each blocking antibody or the isotype control is shown. Error bars represent SEM. Each experiment was done in triplicates, and data are a combination of three independently performed experiments. One-way ANOVA Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used for statistical analysis. (D) EV-DNTs (white bars) and CAR4-DNTs (black bars) were pretreated with DMSO or 100 nM CMA for 30 min and cocultured with CCRF-CEM (left), KARPAS-299 (middle), or primary T-ALL blasts (right) for 2 hours at a 2:1 effector-to-target ratio. Per cent inhibition of specific killing of targets by CMA pretreated effector cells relative to the DMSO control is shown, and error bars represent SEM. Data are a combination of three independently performed experiments. Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001. ANOVA, analysis of variance; CAR4, CD4-CAR; CMA, concanamycin A; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; DNAM-1, DNAX accessory molecule-1; DNTs, double-negative T cells; EV, empty-vector; LFA-1, lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1; NKG2D, natural killer group 2D; PTCL, peripheral T-cell lymphoma; T-ALL, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

DNTs can kill different types of cancers using different mechanisms.14 15 19 To determine the mechanisms used by CAR4-DNTs to kill T-cell tumors, we first stained a panel of molecules that are known to be involved in DNT-mediated killing of AML and lung cancers.14 15 We found that EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs express high levels of lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) subunits, CD11a and CD18, natural killer group 2D (NKG2D), DNAX accessory molecule-1 (DNAM-1), and granzyme B (figure 5B). Next, to investigate the involvement of these molecules in EV-DNT-mediated and CAR4-DNT-mediated killing of T-ALL and PTCL, an in vitro cytotoxicity assay was conducted using EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs against CCRF-CEM, KARPAS-299, and primary T-ALL blasts in the presence of blocking antibodies against these molecules. Relative to isotype controls, LFA-1 and NKG2D blocking significantly inhibited specific killing of CCRF-CEM, KARPAS-299, and primary T-ALL blasts by both EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs (figure 5C). DNAM-1 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α blocking significantly lowered specific killing of KARPAS-299 by EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs (figure 5C). No significant inhibition of specific killing was seen with interferon (IFN)-γ, Fas ligand (FasL), and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) blocking (online supplemental figure S21).

To investigate the role of the perforin/granzyme B pathway in EV-DNT-mediated and CAR4-DNT-mediated killing of T-cell malignancies, EV-DNTs and CAR4-DNTs were pretreated with CMA, an inhibitor of degranulation, prior to cytotoxicity assays against CCRF-CEM, KARPAS, and primary T-ALL cells. CMA significantly reduced the specific killing of all targets by CAR4-DNTs but not EV-DNTs (figure 5D). This indicates that the perforin/granzyme B pathway plays an important role in the cytotoxic capacity of CAR4-DNTs against T-ALL and PTCL. Collectively, these results show that CAR4-DNTs can target T-cell malignancies through LFA-1, NKG2D, and perforin/granzyme B degranulation pathway, and that CAR4 equip DNTs with an additional cytotoxic pathway, degranulation-mediated killing, to more effectively target T-cell malignancies.

Discussion

Allogeneic DNTs have been shown to be a promising candidate for an off-the-shelf adoptive cell therapy for AML.13 14 18 Here, we evaluated the potential of allogeneic DNTs as a therapy for T-cell malignancies. We showed that DNTs induce endogenous cytotoxicity toward T-ALL, PTCL, and primary T-ALL blasts in vitro, but high doses of DNTs are required to achieve therapeutic efficacy in vivo. DNTs were previously shown to be amendable for second generation CAR19 transduction and CAR19-DNTs exhibit potent cytotoxicity against CD19+ B-cell malignancies.20 To increase the potency of DNTs against T-cell malignancies, we successfully transduced allogeneic DNTs with a third generation CAR4 and demonstrated that CAR4-DNTs can be manufactured without fratricide and have superior cytotoxicity against CD4+ T-ALL and PTCL relative to EV-DNTs. CAR4-DNTs eliminated CD4+ T-ALL and PTCL cell lines and primary T-ALL blasts in vitro, and significantly delayed tumor progression and prolonged survival in xenograft models of T-ALL and PTCL. Together, these results show the feasibility of using DNTs as an allogeneic off-the-shelf therapy for T-cell malignancies.

Various molecules are known to be involved in DNT-mediated killing of cancer.14 15 19 DNTs express activating receptors, including NKG2D, DNAM-1, NKp30, and membrane TRAIL, which can be used to target AML and/or lung cancer.14 15 Further, DNTs can secrete cytotoxic molecules, including IFN-γ, soluble TRAIL, and FasL, which have been shown to be involved in killing AML, lung cancer, and pancreatic cancer, respectively.14 15 19 Here, we showed that LFA-1, NKG2D, DNAM-1, and/or TNF-α are significantly involved in EV-DNT-mediated and CAR4-DNT-mediated killing of T-ALL and PTCL. Moreover, perforin/granzyme B pathway plays a significant role in the killing of T-ALL and PTCL by CAR4-DNTs. In contrast, IFN-γ, TRAIL, and FasL have a minimal effect on EV-DNT-mediated and CAR4-DNT-mediated killing of T-ALL and PTCL. These results demonstrate that different molecules may be used by DNTs to target different types of cancer. In addition, CAR-DNTs may enhance the endogenous mechanisms of DNTs or enable new cytotoxic machinery to better kill malignant T-cell targets.

CAR-T cell therapy for T-cell malignancies is associated with unique limitations, including potential contamination of CAR-T cell products with patient-derived malignant T cells, as CAR-transduction of malignant cells has been shown to cause antigen-positive relapse.27 In clinical trials, several selection and sorting strategies have been used to eliminate malignant T cells from autologous CAR-T cell products.28 29 However, these strategies are often not universally applicable and there is the risk of residual malignant cells. To overcome this limitation, allogeneic CAR-T cells that lack TCRs, HLA class I and/or CD52 are manufactured,10 25 30 but multiple genetic modifications can be costly and complicated, with risks of causing off-target effects and toxicities. In a preclinical study, allogeneic CAR19-DNTs have been shown to be a safe off-the-shelf therapy with no observed GvHD and other treatment-related toxicities.20 Here, we further demonstrated the potential of allogeneic CAR4-DNTs as an off-the-shelf CAR-T cell therapy to offer a safer and more cost-effective strategy for targeting T-cell malignancies. We showed that allogeneic CAR4-DNTs and CAR4-Tconv have similar yield per milliliter of blood and antitumor efficacy in vitro and in vivo, while allogeneic CAR4-Tconv-treated mice showed possible signs of acute GvHD in vivo. We expect that TCR and β2M knockout would improve the safety profile of allogeneic CAR4-Tconv. However, these genetic modifications would likely lead to a lower yield, as based on previous publications, the expansion fold of CAR-Tconv with TCR and β2M knockout was less than one-third of that of non-genome-edited Tconv.23 31 This, along with the risk of mutagenesis and the necessary quality control during multiple genetic modifications, highlights the potential manufacturing advantage of CAR4-DNTs.

CAR-T cells therapy for T-cell malignancies is further challenged by the fratricide of CAR-T cells during manufacture, which may result in a lower yield of CAR-T cells and CAR-T cell exhaustion due to repeated CAR-mediated activation. A current approach to prevent the fratricide of CAR-T cells is by knocking out the target T-cell antigen, such as CD3, CD5, and CD7, from Tconv prior to CAR-transduction.24 25 30 However, genetic manipulations of common T-lineage antigens can be detrimental to T cells. For instance, disruption of the TCR/CD3 complex to target CD3+ T-cell malignancies has been shown to negatively affect T-cell proliferation.30 Here, we demonstrated that compared with Tconv, DNTs are not affected by fratricide during transduction with CAR4. This study offers a strategy to manufacture fratricide-free CAR-DNTs without further genetic modifications to target a common T-lineage antigen.

An alternative strategy for developing CAR-based therapy for T-cell malignancies involves the use of innate immune cells, such as NK cells. NK cells are non-alloreactive, lack T-lineage antigens, and have endogenous antitumor function. However, donor-derived NK cells have been shown to be difficult to expand and more resistant to CAR transduction than conventional T cells.32 As a result, all reported CAR-NK cells for T-cell malignancies have used NK-92 cells,26 33–35 which are more standardized and susceptible to genetic manipulations. Since NK-92 cells are a lymphoma cell line, it requires irradiation prior to clinical use, rendering it more short-lived and limiting its endogenous antitumor function. In contrast, donor-derived DNTs can be expanded to therapeutic numbers and the feasibility of using DNT-based therapy in clinic has been demonstrated.13 18 Here, we demonstrated that CAR4-DNTs retain a similar expansion profile as EV-DNTs, supporting the clinical feasibility of CAR4-DNT therapy.

CAR-T cell persistence and memory have been associated with better outcomes in preclinical and clinical studies.36 37 Various methods have been investigated to improve CAR-T cell persistence and overcome CAR-T cell exhaustion, including altering CAR-T cell metabolism.38 39 Previously, PI3K inhibitors, including Ide, have been shown to enhance the memory phenotype and in vivo efficacy of CAR19-Tconv against chronic lymphocytic leukemia.40 41 Further, Ide has been shown to improve the persistence, memory phenotype and antileukemic function of DNTs against AML.17 Here, we showed that pretreatment of CAR4-DNTs with Ide can increase their frequencies of TCM and Tnaïve/SCM phenotype and improve their antileukemic functions in vitro and in the T-ALL xenograft model. These results suggest that consistent with previous reports of CAR19-Tconv, the function of CAR4-DNTs can be augmented by Ide. In the xenograft model, three-dose treatment schedule was used for CAR4-Ide-DNTs. In the recently completed phase I clinical trial using allogeneic DNTs to treat patients with relapsed AML, three infusions of DNTs were given to patients, and no dose-limiting toxicities were observed.18 Once the clinical trial data became available, we used the three-dose treatment schedule for CAR4-Ide-DNTs as we saw that three doses were more relevant clinically.

Antigen-negative relapse has been observed in clinical trials following treatment with CAR-T cell therapy for B-cell malignancies.42 43 Consistent with prior findings, we presently demonstrated that antigen escape is a major contributor to leukemia progression in our T-ALL xenograft model. CD4-negative relapse was observed following treatment with CAR4-DNTs and CAR4-Ide-DNTs, which may be attributed to the survival advantage of CD4-negative subclone within the T-ALL cell line or CD4-downregulation or loss. These results suggest the need for additional strategies to further improve therapeutic efficacy of CAR4-DNTs. Various strategies to overcome antigen escape have been examined, including targeting more than one antigen through the development of bispecific or multispecific CAR-T cells or simultaneous or sequential administration of CAR-T cells of different specificities.44 45 Further, combination of CAR-T cells with other types of therapy, such as radiotherapy, checkpoint inhibitors, and vaccines has been suggested to help induce epitope spreading and counter antigen escape.40 These strategies can be further considered for CAR-DNTs in order to more effectively target T-cell malignancies.

Since CD4 is expressed on normal peripheral T cells, CAR4-DNT therapy may lead to aplasia of CD4+ T cells. CAR-target specific T-cell aplasia has been reported in clinical trials.28 46–50 In most studies, no unmanageable infections are reported.28 46–50 Some studies report that T-cell aplasia is transient and resolved within 9 days to 3 months27 46 48 while other studies show an elevation of antigen-negative T cells.47 49 50 However, the function of antigen-negative T cells against infections is unclear. We showed here that allogeneic CAR4-DNTs do not attack CD4− cells. Since CD4 is expressed on a subset of peripheral T cells, the extent of T-cell aplasia is expected to be limited. Further, various approaches used to mitigate on-target-off-tumor toxicities of CAR-T cells, such as engineering a safety switch and using CAR-T cells as a bridge to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation can be considered for CAR4-DNTs in order to limit the side effects associated with T-cell aplasia.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that allogeneic DNTs have endogenous cytotoxicity against T-cell leukemia and lymphoma, and transduction with a third generation CAR4 can significantly enhance the antitumor efficacy of allogeneic DNTs. CAR4-DNTs are effective against CD4+ T-cell malignancies and overcome several limitations of allogeneic CAR-T cell therapy for T-cell malignancies. These findings open a new window for targeting T-cell malignancies using allogeneic DNTs and CAR4-DNTs and could be expanded to other available CAR targets to target T-cell malignancies.

Acknowledgments

We thank all healthy donors and patients for donating their blood for this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: KF designed and performed experiments and wrote the manuscript. JL designed experiments and edited the manuscript. IK performed experiments and edited the manuscript. YN performed experiments. LZ conceptually designed experiments, supervised the study, edited and reviewed the manuscript, and provided funding. LZ is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding: This work is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant number PJT166038 to LZ).

Competing interests: LZ has financial interests (eg, holdings/shares) in Wyze Biotech Co Ltd and previously received research funding and consulting fee/honorarium from the Company. LZ and JL are inventors of several DNT cell technology-related patents and intellectual properties. JL, IK, and LZ are inventors of a patent related to this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Human samples were collected with consent and used in accordance with a UHN Research Ethics Board-approved protocol (05-0221-T). Animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of UHN (AUP: 741.41) and carried out in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care Guidelines.

References

- 1. Raetz EA, Teachey DT. T-cell acute Lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2016;2016:580–8. 10.1182/asheducation-2016.1.580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mak V, Hamm J, Chhanabhai M, et al. Survival of patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma after first relapse or progression: spectrum of disease and rare long-term survivors. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:1970–6. 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.7524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fielding AK, Richards SM, Chopra R, et al. Outcome of 609 adults after relapse of acute Lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL); an MRC Ukall12/ECOG 2993 study. Blood 2007;109:944–50. 10.1182/blood-2006-05-018192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davila ML, Brentjens RJ. Cd19-targeted CAR T cells as novel cancer Immunotherapy for Relapsed or refractory B-cell acute Lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2016;14:802–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sheykhhasan M, Manoochehri H, Dama P. Use of CAR T-cell for acute Lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) treatment: a review study. Cancer Gene Ther 2022;29:1080–96. 10.1038/s41417-021-00418-1 Available: 10.1038/s41417-021-00418-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fang KK-L, Lee JB, Zhang L. Adoptive cell therapy for T-cell malignancies. Cancers (Basel) 2022;15:94. 10.3390/cancers15010094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fleischer LC, Spencer HT, Raikar SS. Targeting T cell malignancies using CAR-based Immunotherapy: challenges and potential solutions. J Hematol Oncol 2019;12:141. 10.1186/s13045-019-0801-y Available: 10.1186/s13045-019-0801-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sanber K, Savani B, Jain T. Graft-versus-host disease risk after Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy: the Diametric opposition of T cells. Br J Haematol 2021;195:660–8. 10.1111/bjh.17544 Available: 10.1111/bjh.17544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alcantara M, Tesio M, June CH, et al. CAR T-cells for T-cell malignancies: challenges in distinguishing between therapeutic, normal, and neoplastic T-cells. Leukemia 2018;32:2307–15. 10.1038/s41375-018-0285-8 Available: 10.1038/s41375-018-0285-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Depil S, Duchateau P, Grupp SA, et al. Off-the-shelf’ allogeneic CAR T cells: development and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2020;19:185–99. 10.1038/s41573-019-0051-2 Available: 10.1038/s41573-019-0051-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pan K, Farrukh H, Chittepu VCSR, et al. CAR race to cancer Immunotherapy: from CAR T, CAR NK to CAR macrophage therapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2022;41:119. 10.1186/s13046-022-02327-z Available: 10.1186/s13046-022-02327-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Elahi R, Heidary AH, Hadiloo K, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-engineered natural killer (CAR NK) cells in cancer treatment; recent advances and future prospects. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2021;17:2081–106. 10.1007/s12015-021-10246-3 Available: 10.1007/s12015-021-10246-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee JB, Kang H, Fang L, et al. Developing allogeneic double-negative T cells as a novel off-the-shelf adoptive cellular therapy for cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:2241–53. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee J, Minden MD, Chen WC, et al. Allogeneic human double negative t cells as a novel Immunotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia and its underlying mechanisms. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24:370–82. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yao J, Ly D, Dervovic D, et al. Human double negative T cells target lung cancer via ligand-dependent mechanisms that can be enhanced by IL-15. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:17. 10.1186/s40425-019-0507-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Achita P, Dervovic D, Ly D, et al. Infusion of ex-vivo expanded human TCR-Αβ+ double-negative regulatory T cells delays onset of Xenogeneic Graft- versus -Host disease. Clin Exp Immunol 2018;193:386–99. 10.1111/cei.13145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kang H, Lee JB, Khatri I, et al. Enhancing therapeutic efficacy of double negative t cells against acute myeloid leukemia using Idelalisib. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:5039. 10.3390/cancers13205039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tang B, Lee JB, Cheng S, et al. Allogeneic Double‐Negative T cell therapy for Relapsed acute myeloid leukemia patients post allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A First‐In‐Human phase I study. Am J Hematol 2022;97:E264–7. 10.1002/ajh.26564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lu Y, Hu P, Zhou H, et al. Double-negative T cells inhibit proliferation and invasion of human Pancreatic cancer cells in Co-culture. Anticancer Res 2019;39:5911–8. 10.21873/anticanres.13795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vasic D, Lee JB, Leung Y, et al. Allogeneic double-negative CAR-T cells inhibit tumor growth without off-tumor toxicities. Sci Immunol 2022;7:eabl3642. 10.1126/sciimmunol.abl3642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Noronha EP, Marques LVC, Andrade FG, et al. The profile of Immunophenotype and genotype aberrations in Subsets of pediatric T-cell acute Lymphoblastic leukemia. Front Oncol 2019;9:316. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pu Q, Qiao J, Liu Y, et al. Differential diagnosis and identification of Prognostic markers for peripheral T-cell lymphoma subtypes based on flow Cytometry Immunophenotype profiles. Front Immunol 2022;13:1008695. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1008695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu X, Zhang Y, Cheng C, et al. CRISPR-Cas9-mediated Multiplex gene editing in CAR-T cells. Cell Res 2017;27:154–7. 10.1038/cr.2016.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gomes-Silva D, Srinivasan M, Sharma S, et al. Cd7-edited T cells expressing a Cd7-specific CAR for the therapy of T-cell malignancies. Blood 2017;130:285–96. 10.1182/blood-2017-01-761320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cooper ML, Choi J, Staser K, et al. “An “off-the-shelf” Fratricide-resistant CAR-T for the treatment of T cell hematologic malignancies”. Leukemia 2018;32:1970–83. 10.1038/s41375-018-0065-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen KH, Wada M, Pinz KG, et al. Preclinical targeting of aggressive T-cell malignancies using anti-Cd5 Chimeric antigen receptor. Leukemia 2017;31:2151–60. 10.1038/leu.2017.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ruella M, Xu J, Barrett DM, et al. Induction of resistance to Chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy by Transduction of a single Leukemic B cell. Nat Med 2018;24:1499–503. 10.1038/s41591-018-0201-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lu P, Liu Y, Yang J, et al. Naturally selected Cd7 CAR-T therapy without genetic manipulations for T-ALL/LBL: first-in-human phase I clinical trial. Blood 2022. 10.1182/blood.2021014498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang M, Chen D, Fu X, et al. Autologous Nanobody-derived Fratricide-resistant Cd7-CAR T-cell therapy for patients with Relapsed and refractory T-cell acute Lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 2022;28:2830–43. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-4097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rasaiyaah J, Georgiadis C, Preece R, et al. TCRαβ/Cd3 disruption enables Cd3-specific Antileukemic T cell Immunotherapy. JCI Insight 2018;3:e99442. 10.1172/jci.insight.99442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ren J, Liu X, Fang C, et al. Multiplex genome editing to generate universal CAR T cells resistant to Pd1 inhibition. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:2255–66. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang L, Meng Y, Feng X, et al. CAR-NK cells for cancer Immunotherapy: from bench to bedside. Biomark Res 2022;10. 10.1186/s40364-022-00364-6 Available: 10.1186/s40364-022-00364-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pinz KG, Yakaboski E, Jares A, et al. Targeting T-cell malignancies using anti-Cd4 CAR NK-92 cells. Oncotarget 2017;8:112783–96. 10.18632/oncotarget.22626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Raikar SS, Fleischer LC, Moot R, et al. Development of Chimeric antigen receptors targeting T-cell malignancies using two structurally different anti-Cd5 antigen binding domains in NK and CRISPR-edited T cell lines. Oncoimmunology 2018;7:e1407898. 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1407898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xu Y, Liu Q, Zhong M, et al. 2B4 Costimulatory domain enhancing cytotoxic ability of anti-Cd5 Chimeric antigen receptor engineered natural killer cells against T cell malignancies. J Hematol Oncol 2019;12:49. 10.1186/s13045-019-0732-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Biasco L, Izotova N, Rivat C, et al. Clonal expansion of T memory stem cells determines early anti-Leukemic responses and long-term CAR T cell persistence in patients. Nat Cancer 2021;2:629–42. 10.1038/s43018-021-00207-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Arcangeli S, Bove C, Mezzanotte C, et al. CAR T-cell manufacturing from naive/stem memory T-lymphocytes enhances antitumor responses while curtailing cytokine release syndrome. J Clin Invest 2022;132:e150807. 10.1172/JCI150807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang M, Jin X, Sun R, et al. Optimization of metabolism to improve efficacy during CAR-T cell manufacturing. J Transl Med 2021;19:499. 10.1186/s12967-021-03165-x Available: 10.1186/s12967-021-03165-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gumber D, Wang LD. Improving CAR-T immunotherapy: overcoming the challenges of T cell exhaustion. EBioMedicine 2022;77:103941. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103941 Available: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Funk CR, Wang S, Chen KZ, et al. Pi3Kδ/Γ inhibition promotes human CART cell epigenetic and metabolic Reprogramming to enhance antitumor cytotoxicity. Blood 2022;139:523–37. 10.1182/blood.2021011597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stock S, Übelhart R, Schubert M-L, et al. Idelalisib for Optimized Cd19-specific Chimeric antigen receptor T cells in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. Int J Cancer 2019;145:1312–24. 10.1002/ijc.32201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Majzner RG, Mackall CL. Tumor antigen escape from car t-cell therapy. Cancer Discov 2018;8:1219–26. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0442 Available: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gardner R, Wu D, Cherian S, et al. Acquisition of a Cd19-negative myeloid phenotype allows immune escape of MLL-rearranged B-ALL from Cd19 CAR-T-cell therapy. Blood 2016;127:2406–10. 10.1182/blood-2015-08-665547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Han X, Wang Y, Wei J, et al. Multi-antigen-targeted Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol 2019;12:128. 10.1186/s13045-019-0813-7 Available: 10.1186/s13045-019-0813-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sterner RC, Sterner RM. CAR-T cell therapy: Current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J 2021;11:69. 10.1038/s41408-021-00459-7 Available: 10.1038/s41408-021-00459-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Feng J, Xu H, Cinquina A, et al. Treatment of aggressive T-cell lymphoma/leukemia with anti-Cd4 CAR T cells. Front Immunol 2022;13. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.997482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pan J, Tan Y, Shan L, et al. Phase I study of donor-derived Cd5 CAR T cells in patients with Relapsed or refractory T-cell acute Lymphoblastic leukemia. JCO 2022;40:7028. 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.7028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Feng J, Xu H, Cinquina A, et al. Treatment of aggressive T cell Lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia using anti-Cd5 CAR T cells. Stem Cell Rev Rep 2021;17:652–61. 10.1007/s12015-020-10092-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhao L, Pan J, Tang K, et al. Autologous Cd7-targeted CAR T-cell therapy for refractory or Relapsed T-cell acute Lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. JCO 2022;40:7035. 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.7035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pan J, Tan Y, Wang G, et al. Donor-derived Cd7 Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for T-cell acute Lymphoblastic leukemia: first-in-human. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:3340–51. 10.1200/JCO.21.00389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2023-007277supp001.pdf (2.4MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.