Abstract

PURPOSE

This prospective Brazilian single-arm trial was conducted to determine response to chemotherapy and survival after response-based radiotherapy in children with intracranial germinomas, in the setting of a multi-institutional study in a middle-income country (MIC) with significant disparity of subspecialty care.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Since 2013, 58 patients with histologic and/or serum and CSF tumor marker evaluations of primary intracranial germ cell tumors were diagnosed; 43 were germinoma with HCGβ levels ≤200 mIU/mL and five between 100 and 200 mIU/mL. The treatment plan consisted of four cycles of carboplatin and etoposide followed by 18 Gy whole-ventricular field irradiation (WVFI) and primary site(s) boost up to 30 Gy; 24 Gy craniospinal was prescribed for disseminated disease.

RESULTS

Mean age 13.2 years (range, 4.7-25.5 years); 29 were males. Diagnosis was made by tumor markers (n = 6), surgery (n = 25), or both (n = 10). Two bifocal cases with negative tumor markers were treated as germinoma. Primary tumor location was pineal (n = 18), suprasellar (n = 14), bifocal (n = 10), and basal ganglia/thalamus (n = 1). Fourteen had ventricular/spinal spread documented by imaging studies. Second-look surgery occurred in three patients after chemotherapy. Thirty-five patients achieved complete responses after chemotherapy, and eight showed residual teratoma/scar. Toxicity was mostly grade 3/4 neutropenia/thrombocytopenia during chemotherapy. At a median follow-up of 44.5 months, overall and event-free survivals were 100%.

CONCLUSION

The treatment is tolerable, and WVFI dose reduction to 18 Gy preserves efficacy; we have demonstrated the feasibility of successfully conducting a prospective multicenter trial in a large MIC despite resource disparity.

INTRODUCTION

Primary intracranial germ cell tumors (GCT) are divided into germinomas (G) and nongerminomatous (NG) GCT.1-4 They are primarily located in the midline, at the pineal, suprasellar region, both locations (bifocal), and rarely at other sites such as thalamus, basal ganglia, and posterior fossa.1-3,5 Germinomas account for two thirds of these tumors4,6 and are extremely radiosensitive with excellent cure rates.7 However, to reduce dose and volume of irradiation, several groups are trying to refine treatment approach through efforts to minimize the late effects without jeopardizing the outcomes.8-10

CONTEXT

Key Objective

Intracranial germinomas are extremely radiosensitive with excellent cure rates, with several groups trying to refine the treatment approach to reduce dose and volume of irradiation. This prospective single-arm trial in children with newly diagnosed intracranial germinoma explores the feasibility of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by reduced dose of whole-ventricular field irradiation (WVFI) in a large middle-income country (MIC).

Knowledge Generated

Recommended neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by reduced dose of WVFI. Also, the importance of second-look surgery after four cycles of chemotherapy if less than complete response.

Relevance

This study supports the need of collaborative practices in MIC to face inherent difficulties in countries with fewer resources to achieve an excellent survival with quality of life for these patients.

In this context, the Brazilian consortium performed a single-arm trial to explore the feasibility of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by reduced dose of whole-ventricular field irradiation (WVFI) for intracranial germinomas, demonstrating the ability to conduct a multidisciplinary prospective trial in a large middle-income country (MIC). It is important to emphasize that the Brazilian health care system is characterized by a unified health system called Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS), which provides universal access to all citizens. There are also patients who have private health insurance that would cover treatment in private hospitals. In this study, however, all services and patients involved were covered by the SUS.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A multicenter prospective trial of patients diagnosed with intracranial GCT at IOP/GRAACC/Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), Hospital do Amor de Barretos, Hospital Santa Marcelina/TUCCA, São Paulo State, Brazil, was performed between 2013 and 2021. Data were analyzed in March 2022.

The primary objectives of this study were to determine the event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) at 3 and 5 years of follow-up from diagnosis for patients with intracranial germinoma. The secondary objectives were to implement second-look surgery for patients without radiologic complete response (CR) after induction chemotherapy and observe its impact on survival.

The study was approved by the institutional review boards at each of the institutions. The patients' legal guardians consented to treatment and the patients themselves assented (children age 6 years or older) or consented (age 18 years or older) when age was appropriate.

Eligibility Criteria

The following criteria were required for enrollment in the study1: Patients with newly diagnosed intracranial germinoma regardless of age, without irradiation or previous chemotherapy (except corticosteroids), and with biopsy-proven and/or serum/CSF tumor marker elevations according to recommended values2; human chorionic gonadotropin-beta (HCGβ) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels in both lumbar CSF and serum determined in the perioperative period3; CSF collection for the determination of leptomeningeal dissemination by cytology performed preoperatively, intraoperatively, or 14 days after surgery, by lumbar puncture4; and craniospinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without contrast obtained in the preoperative period and 48 hours perioperatively or after 14 days of surgery.

Pathology Review

All histopathologic diagnoses were made by a board-certified pathologist at each of the institutions. The time required for biopsy results was 14-21 days.

Staging Procedures

Patients were staged with craniospinal MRI and lumbar CSF cytology and tumor markers at baseline unless clinically contraindicated. Positive CSF cytology and/or more than one intracranial focus, spinal metastases, or metastases outside the CNS, except bifocal disease, were defined as metastatic disease. Tumor markers, both HCGβ and AFP, were obtained in serum and CSF to exclude secreting tumor elements at initial diagnosis and follow-up. For the diagnosis of germinoma, the levels of AFP had to be undetectable and HCGβ levels ≤200 IU/L, preferable with biopsy. Any detectable elevation of AFP (generally, serum [5-10 ng/dL]; CSF [2-5 ng/dL]) and marked CSF elevation of HCGβ >200 IU/L in this series were considered diagnostic of NGGCT without histologic confirmation. All patients with negative tumor markers were submitted to tumor biopsy for histopathologic diagnosis. Synchronous bifocal intracranial tumors, defined as masses in the pineal and suprasellar region or pineal tumors with confirmed diagnosis of diabetes insipidus, for purposes of irradiation treatment, were treated as localized disease and received irradiation boost at both sites, in addition to WVFI.

Treatment

All patients received a platinum-based chemotherapy regimen consisting of four cycles once every 3 weeks of 2 consecutive days of carboplatin (300 mg/m2) and etoposide (225 mg/m2), a scheme already used in our previous Protocol,11 as outpatient, without necessity of hyperhydration. The final concentration of carboplatin should be between 0.5 and 2 mg/mL in dextrose 5% or saline 0.9%, and for etoposide should not be >0.5 mg/mL in saline 0.9%. Before each cycle, the absolute neutrophil count was required to be >500/mm3, platelet count >100,000/mm3, creatinine level <1.5 mg/dL, transaminases <5× the institutional normal level, and bilirubin <2.0 mg/dL. Therapy was delayed if the patient did not meet criteria, but episodes of fever and slow recovery neutropenia would not require dose reduction in subsequent cycles. In case of absolute neutrophil <500/mm3, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor should be used (5 mcg/kg/d, subcutaneous) until postnadir white cell count is >10,000/mm3.

Assessment of disease was repeated after recovery from every two chemotherapy cycles with serum/CSF tumor markers and craniospinal MRI. Second surgical resection was considered if residual disease was present on imaging studies after the four cycles of chemotherapy. Patients without evidence of tumor progression (by either imaging or tumor marker increases) during induction chemotherapy received response-adjusted radiotherapy.

Radiotherapy was delivered after chemotherapy using intensity-modulated radiation therapy and volumetric modulated arc therapy. The prescribed dose fraction, including the tumor bed boost, varied from 1.5 to 2 Gy per day, with five fractions per week. For patients achieving CR to either induction chemotherapy alone or with the addition of second-look surgery consisted of WVFI of 18 Gy with a tumor bed boost of 12 Gy. In case of partial response (PR) and histopathology consisting of mature and immature teratoma, a tumor bed boost dose of 22 and 36 Gy, respectively, was considered. Patients with metastatic disease received craniospinal irradiation after neoadjuvant chemotherapy to a dose of 24 Gy and 12 Gy boost to the primary site.

All adverse events were categorized according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0.

Evaluations and Follow-Up

Craniospinal MRI with and without gadolinium contrast and serum/lumbar CSF tumor markers were performed after the second and fourth chemotherapy cycles, approximately 6 weeks after irradiation, every 4 months in the first 3 years after treatment, every 6 months until the fifth year, and annually thereafter.

Tumor measurements were assessed by certified neuroradiologists at each of the institutions and response was graded using the revised RECIST criteria12: CR was defined as no radiologic evidence of tumor and normalization of both serum and lumbar CSF tumor markers; PR as 50% reduction in the product of the two greatest tumor diameters on imaging and reduction of previously elevated HCGβ levels in both serum and CSF; minor response as 25%-50% reduction on imaging and some reduction of previously elevated serum/CSF HCGβ; stable disease as <25% decrease in imaging size; and progressive disease as 25% increase in the tumor size or increasing elevations of either HCGβ or AFP in either serum or CSF. Patients with residual disease and negative tumor markers were discussed as case by case in a multidisciplinary board meeting.

Statistical Considerations

Patient characteristics were described using the absolute and relative frequencies for the qualitative variables and average, median, minimum, and maximum values for the quantitative variables.

The nonparametric EFS and OS curves were calculated using the product-limit (Kaplan-Meier) estimates. EFS was defined as the time to disease progression, disease relapse, occurrence of a second neoplasm, or death from any cause measured from the time of study enrollment. OS was defined as the time elapsed from diagnosis to the time of death due to all causes or the last follow-up visit. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software for Windows (version 28.0).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

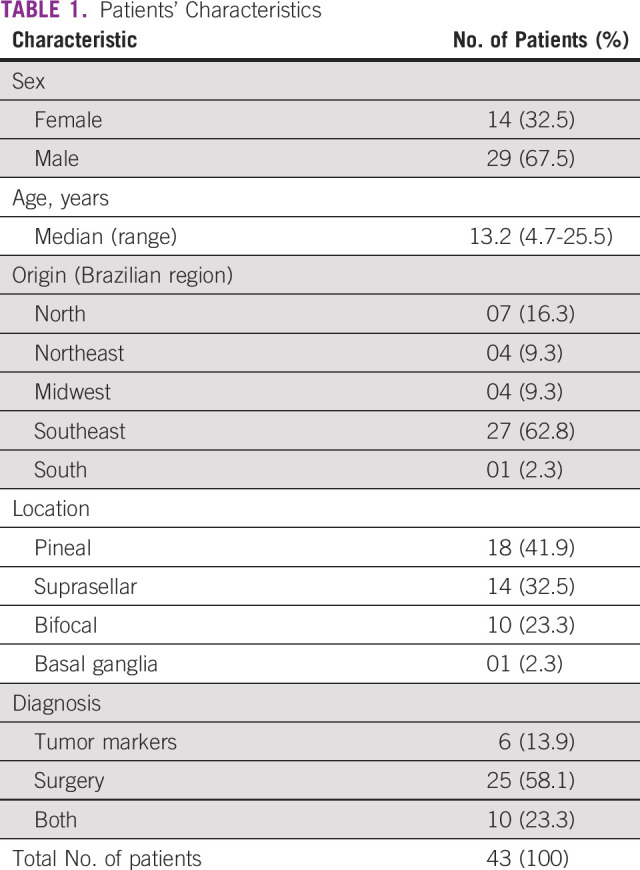

Fifty-eight patients (42 male and 16 female) with primary intracranial GCT were enrolled, 43 with germinomas. The 15 patients with NGGCT will be described separately. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Patients' Characteristics

The median age at diagnosis was 13.2 years (range, 4.7-25.5 years); 29 were males. The tumor was located in the pineal in 18 patients, suprasellar in 14, bifocal in 10, and one in the basal ganglia. Diagnosis was made by tumor markers (n = 6), surgery (n = 25), or both (n = 10). Two bifocal cases with negative tumor markers were treated as germinoma. Five patients had HCGβ serum and/or lumbar CSF between 100 and 200 IU/mL. Disseminated disease was observed in 14 patients, nine in the ventricular area, three in the spinal axis, one in the posterior fossa, and one patient presented with positive lumbar CSF cytology at diagnosis without spinal lesions on MRI.

Treatment Outcomes

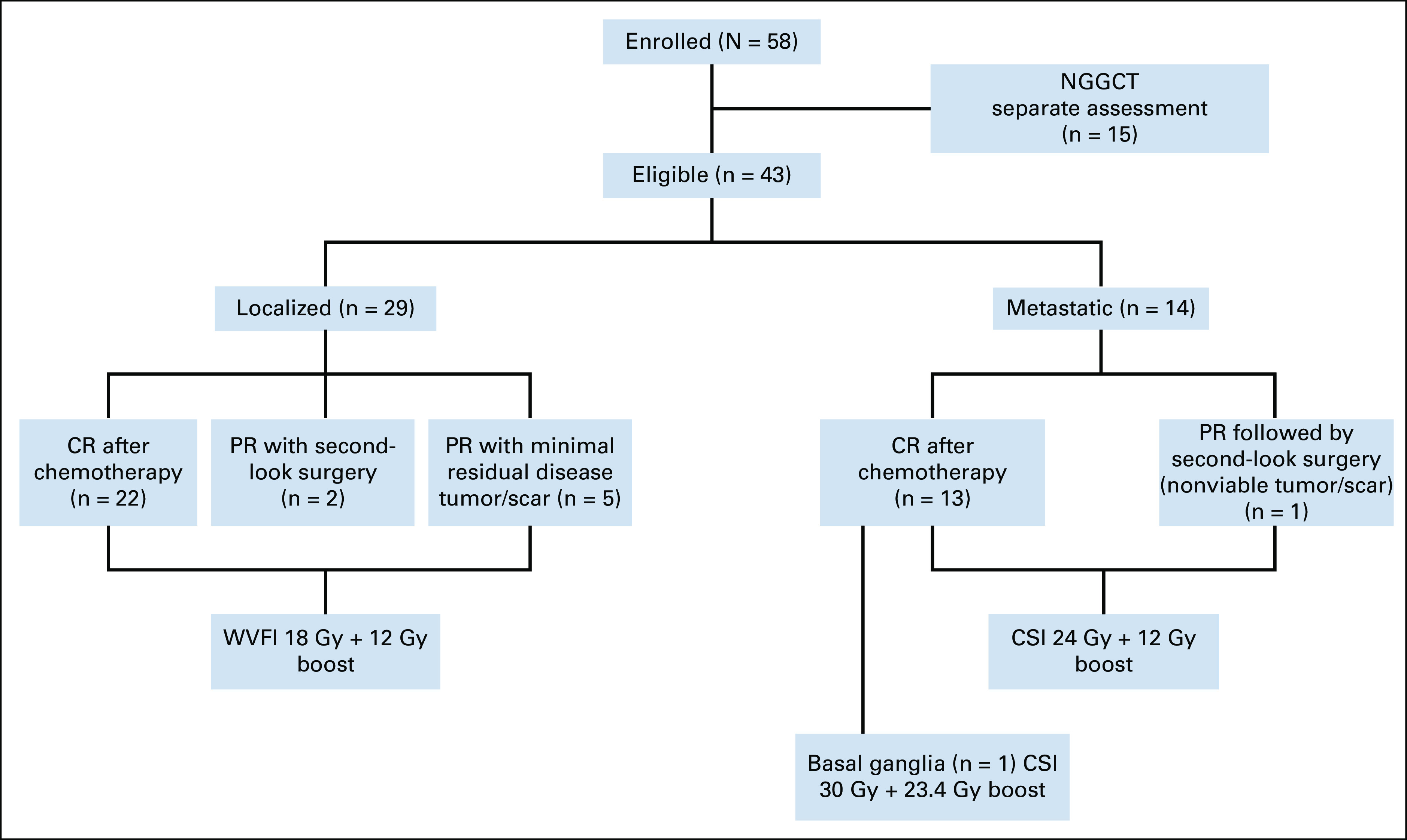

All patients completed the induction chemotherapy as scheduled, except for one who underwent radiotherapy (RT) in CR after two cycles because of grade 4 infection toxicity. The extent of disease and respective responses and RT doses and field are detailed in the Figure 1. The median interval between chemotherapy cycles was 21 days (range, 21-34 days).

FIG 1.

Enrolled patients diagram. CR, complete response; CSI, craniospinal irradiation; NGGCT, nongerminomatous germ cell tumors; PR, partial response; WVFI, whole-ventricular field irradiation.

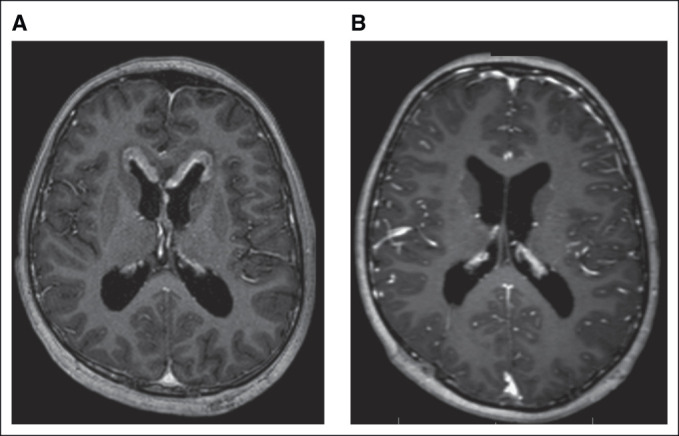

The tumor status after induction chemotherapy was CR in 35 patients (28 after two cycles): 22 with localized disease and 13 metastatic disease. Figure 2 shows an example of ventricular dissemination at diagnosis with CR after four cycles of chemotherapy.

FIG 2.

Male, age 12 years. (A) Ventricular dissemination at diagnosis. (B) Complete response after four chemotherapy cycles.

Eight patients showed a partial imaging response after the end of chemotherapy, however, with a minimal unresectable residual disease in five cases. Second-look surgery was performed in three cases showing teratoma on histopathology in two localized ones (one growing teratoma). The third patient with disseminated disease showed fibrosis at second-look.

Of the five patients with HCGβ between 100 and 200 IU/mL, three underwent biopsy at diagnosis, one had bifocal tumor, and the other was a girl with suprasellar lesion and panhypopituitarism. Only one had disseminated disease in the ventricular area. Four patients achieved CR after four cycles and one patient showed minimal residual lesion (fibrosis/scar) on MRI. The irradiation occurred as CR with 18 Gy WVFI + 12 Gy boost.

The patient with basal ganglia presented with metastatic disease at diagnosis and despite achieving CR after four cycles of chemotherapy, the medical decision was to deliver 30 Gy CSI and a tumor bed boost of 23.4 Gy.

No recurrences or deaths were observed before the study evaluation closing data, with a median follow-up of 44.5 months (range, 6-111 months) and an EFS and OS in 3 and 5 years of 100%. Only one patient lost follow-up after 42 months.

Toxicity

The most common toxicity observed was grade 3/4 hematologic toxicities. Toxicities consisted predominantly of anemia (n = 19), neutropenia (n = 72), and thrombocytopenia (n = 81) in all assessable cycles. Eleven episodes of febrile neutropenia occurred. One patient had grade 4 infection with positive blood cultures for Candida sp, Pseudomonas sp, and Klebsiella sp multiresistant. None developed symptoms relating to electrolyte disturbances.

DISCUSSION

This study represents the implementation of a Brazilian consortium Protocol for patients with newly diagnosed intracranial GCT, with neoadjuvant chemotherapy treatment as a strategy to promote tailored reduction of radiotherapy doses. Despite the rarity of CNS GCT accounting for only 3%-5% of CNS tumors,2,4 it was possible through this consortium to gather a meaningful number of patients and demonstrate the importance of uniform standards of practices for the care of these pediatric and young adult neuro-oncology patients.

Epidemiologically, and in accordance with literature reports, our series demonstrated the prevalence of CNS GCT in adolescent patients, age 10-14 years,2,4,6 with pineal location predominance (41.8%), one rare basal ganglia tumor,5 and the majority of suprasellar cases in female patients (71.4%).2,3,6 By contrast, a greater number of patients with bifocal disease were found (23.2%).2,3 All our patients with bifocal disease had pineal and suprasellar lesions on MRI, although it is imperative to highlight the importance of an accurate diagnosis and appropriate subsequent treatment of a patient with a pineal region only lesion but clinical signs of diabetes insipidus, as a case of bifocal germinoma.13

The histologic confirmation of these midline brain tumors can be a major challenge in some MIC. Nonetheless, the requirement for an adequate open biopsy is strongly recommended in cases with no tumor marker elevations,2,6,13 even in bifocal cases as described in recent publications,13,14 reinforcing the need for consensus practices and treatment at specialized centers. In our study, 25 patients with negative tumor markers had the diagnosis confirmed upon biopsy. Two bifocal cases with negative tumor markers were treated as pure germinoma, one because of an inconclusive stereotactic biopsy and the other because of visual loss considered to require emergency treatment by the local institution. Also, Khatua et al15 and the Japanese experience16-18 already suggested that the approach with chemotherapy and involved-field irradiation seems to be adequate even for patients with HCGβ up to 200 IU/mL. The Japanese Brain Tumor Study Group showed excellent survival rates for this group of patients, reporting 39 patients with germinoma having HCGβ secretion in serum or CSF up to 200 mIU/mL, with no difference in recurrence-free survival (90.1% v 84.6%) or OS (98.3% v 100%), compared with 131 patients without HCGβ secretion, and no difference in time to achieve CR with pre-RT chemotherapy.18 In fact, the five patients described in our series with HCGβ from 100 to 200 IU/mL showed excellent responses with no recurrence at this point.

Historically, several multinational prospective clinical trials have been undertaken to streamline optimal treatment approaches for these tumors. Radiotherapy alone can achieve excellent cure rates, approaching 90% EFS,8 but because of concerning late effects, especially neuroendocrines and cognitive, chemotherapy schemes were incorporated. Three chemotherapy studies without radiotherapy were performed showing, however, inferior outcomes, with increased risk of periventricular relapses in the germinoma group, proving the necessity for irradiation in these areas.11,19,20

Currently, induction chemotherapy with platinum agents (carboplatin or cisplatin) and etoposide, followed by whole-ventricular or extended locoregional field radiotherapy, has been the backbone of treatment, as described by Khatua et al,15 the Japanese Group,16,17 Société Internationale d’Oncologie Pédiatrique (SIOP),21 and the North American Children's Oncology Group (COG)22 experiences. Regarding chemotherapy options, the carboplatin regime efficacy is well documented and used in other series15,22,23 because of the associated higher risk of significant sensorineural ototoxicity, neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity associated with cisplatin and especially, the avoidance of hyperhydration in patients with diabetes insipidus that can lead to severe endocrine complications regarding sodium management.24,25 We have demonstrated not only the efficacy of carboplatin-etoposide regimen with a great proportion of patients achieving a CR, as well as mostly nonendrocrinal toxicities, although highlighting the necessity of blood count control for the expected hematologic toxicities, especially thrombocytopenia.

The minimum radiotherapy dose that is enough to treat a patient with CNS germinoma is one of the major challenges confronted over recent decades. The SIOP-96 trial achieved a good initial response with a 5-year EFS rate of 88% ± 4% for localized germinomas treated with chemotherapy followed by focal field radiotherapy, but this treatment was insufficient to control subependymal growth in the ventricular area suggesting the need to enlarge the irradiation field.21 The Japanese Group demonstrates excellent results with enlarged locoregional radiotherapy fields, with a 5-year EFS rate of 95.7% for patients with germinoma,17 and the recently published results of COG ACNS 1123 for localized germinoma (n = 137), with carboplatin-etoposide chemotherapy followed by WVFI, despite the failure to achieve the objective of at least 95% 3-year EFS, indicate excellent outcomes with 3-year estimated EFS and OS rates of 94.5% ± 2.7% and 100% for 18 Gy and 93.75% ± 6.1% and 93.75% ± 6.1% for 24 Gy.22 Our study, despite the smaller patient size, similarly demonstrates that neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by 18 Gy WVFI preserves efficacy with no recurrences and deaths at 5-year EFS analysis.

Another important controversy to discuss is the necessity of craniospinal irradiation (CSI) RT to patients with ventricular dissemination and for CSF-positive cytology without MRI spinal lesions, 9/14 and 1/14, respectively in our series. Toronto experience reported three patients with ventricular dissemination who received either whole-ventricular or whole-brain radiation excluding the spinal axis.26 The recent COG study ACNS 1123 showed seven patients with ventricular-based lesions and only one spinal relapse after WVI and a boost to the tumor bed strategy.22 Regarding CSF-positive cytology, Kanamori et al27 reported comparable EFS between patients treated with and without CSI, however, on the basis of institutionally reported positive CSF cytology. Future studies should access the opportunity to decrease the radiotherapy field for these groups of patients; however, it is important to reinforce the critical role of central review of imaging and CSF cytospins in such cases.

The role of second-look surgery has also been explored in prior studies, both in small institutional, mainly retrospectives,28,29 and multicenter prospective trials.21,22 The main purpose is to identify residual viable germinoma (or NGGCT elements), nonviable residual scar and/or gliosis/neovascularization, and mature/immature teratoma—the optimal treatment for which is gross total resection and, in the case of immature teratoma, higher-dose of focal irradiation up to 54 Gy.30 The ACNS1123 study showed that germinoma patients with residual disease of more than 1.5 cm2 but no viable malignant cells on histopathology experienced no negative effects on the excellent outcomes. In our series, the recommendation for patients with residual radiographic lesions and normalized serum/lumbar CSF tumor markers after induction chemotherapy to undergo open generous biopsy and resection if safely possible was based on the possibility of reducing the dose of focal radiotherapy depending on histology. In the assessed group, eight patients demonstrated imaging with PR after four cycles of chemotherapy, but mostly with minimal residual disease with no possibility of surgical intervention (presumed to be fibrosis/scar). Two additional patients, however, were submitted to second-look surgery showing mature teratoma components, one of them having presented as growing teratoma syndrome after one cycle of chemotherapy, a rare phenomenon in intracranial GCT (5%) and even more so in the pure germinoma group.31

Brazil is a very large and highly diverse country with geographic and economic inequality including in cancer distribution and care, so it is a possibility that collaborative practices in MIC, such as this consortium, would have a crucial role in pediatric cancer care. Grabois et al32 in 2011 reported a greater concentration of chemotherapy administration in the Center South of Brazil and reduced rates in the North and peripheral regions of the Northeast. Furthermore, the same author demonstrated the access to pediatric cancer care in Brazil, showing 12 main cities as the health districts of Brazil (São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte, Curitiba, Porto Alegre, Brasília, Goiania, Fortaleza, Recife, Salvador, Manaus, and Belem), also suggesting the existence of a deficit in access to cancer treatment for children and adolescents living in the North and Northeast.33 The present consortium, composed of centers in the Southeast, was responsible for the entire treatment of the patients. Sixteen patients (37.2%) from other regions of Brazil came as newly diagnosed patients referenced by the unified health system (SUS). Other retrospectives experiences in MIC also shows the importance of cooperative practices in other MIC34,35 and barriers to be addressed such as late diagnosis, poor adherence to treatment, and treatment-related complications.36,37

This study presents certain limitations. First, it was not possible to conduct a more encompassing multicenter trial in a country of the continental dimensions, compounded by the substantial diversity of available health care facilities and expertise throughout the country. Second, it proved impossible to engage or identify appropriate multidisciplinary team to undertake and accomplish prospective quality-of-life assessments on the enrolled patients. Both limitations largely reflect the insufficiency of financial support for the conduct of clinical trials in Brazil.

Ultimately, our experience, as evidenced by the 100% EFS and OS at 5 years, documents that collaborative practices in MIC can play a crucial role in the worldwide effort to define standards of care, maximize cure, and help improve the quality of life of patients with CNS malignancies.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Andrea Maria Cappellano, Natalia Dassi, Patricia A. Dastoli, Simone S. Aguiar, Gustavo R. Teixeira, Nasjla S. Silva, Jonathan L. Finlay

Financial support: All authors

Administrative support: Andrea Maria Cappellano, Natalia Dassi, Nasjla S. Silva, Jonathan L. Finlay

Provision of study materials or patients: Andrea Maria Cappellano, Bruna Mançano, Daniela B. Almeida, Sergio Cavalheiro, Maria Teresa Seixas, Jardel M. Nicacio, Frederico A. Silva, Simone S. Aguiar, Gustavo R. Teixeira, Nasjla S. Silva

Collection and assembly of data: Andrea Maria Cappellano, Natalia Dassi, Bruna Mançano, Sidnei Epelman, Daniela B. Almeida, Sergio Cavalheiro, Patricia A. Dastoli, Carlos R. Almeida, Michael Chen, Maria Luisa Figueiredo

Data analysis and interpretation: Andrea Maria Cappellano, Natalia Dassi, Patricia A. Dastoli, Maria Teresa Seixas, Jardel M. Nicacio, Marcos D. Costa, Frederico A. Silva, Nasjla S. Silva, Jonathan L. Finlay

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kong Z, Wang Y, Dai C, et al. Central nervous system germ cell tumors: A review of the literature. J Child Neurol. 2018;33:610–620. doi: 10.1177/0883073818772470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Osorio DS, Allen JC. Management of CNS germinoma. CNS Oncol. 2015;4:273–279. doi: 10.2217/cns.15.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frappaz D, Dhall G, Murray MJ, et al. EANO, SNO and Euracan consensus review on the current management and future development of intracranial germ cell tumors in adolescents and young adults. Neuro Oncol. 2022;24:516–527. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aridgides P, Janssens GO, Braunstein S, et al. Gliomas, germ cell tumors, and craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68:e28401. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28401. suppl 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Graham RT, Abu-Arja MH, Stanek JR, et al. Multi-institutional analysis of treatment modalities in basal ganglia and thalamic germinoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68:e29172. doi: 10.1002/pbc.29172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fetcko K, Dey M. Primary central nervous system germ cell tumors: A review and update. Med Res Arch. 2018;6:1719. doi: 10.18103/mra.v6i3.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bamberg M, Kortmann RD, Calaminus G, et al. Radiation therapy for intracranial germinoma: Results of the German cooperative prospective trials MAKEI 83/86/89. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2585–2592. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hill-Kayser CE, Indelicato DJ, Ermoian R, et al. Pediatric central nervous system germinoma: What can we understand from a worldwide effort to maximize cure and minimize risk? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;107:227–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takami H, Nakamura H, Ichimura K, et al. Still divergent but on the way to convergence: Clinical practice of CNS germ cell tumors in Europe and North America from the perspectives of the East. Neurooncol Adv. 2022;4:vdac061. doi: 10.1093/noajnl/vdac061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O'Neil S, Ji L, Buranahirun C, et al. Neurocognitive outcomes in pediatric and adolescent patients with central nervous system germinoma treated with a strategy of chemotherapy followed by reduced-dose and volume irradiation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:669–673. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. da Silva NS, Cappellano AM, Diez B, et al. Primary chemotherapy for intracranial germ cell tumors: Results of the third international CNS germ cell tumor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:377–383. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kanamori M, Takami H, Yamaguchi S, et al. So-called bifocal tumors with diabetes insipidus and negative tumor markers: Are they all germinoma? Neuro Oncol. 2021;23:295–303. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noaa199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nakamura H, Takami H, Yanagisawa T, et al. The Japan Society for Neuro-Oncology guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of central nervous system germ cell tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2022;24:503–515. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khatua S, Dhall G, O'Neil S, et al. Treatment of primary CNS germinomatous germ cell tumors with chemotherapy prior to reduced dose whole ventricular and local boost irradiation. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55:42–46. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matsutani M, Japanese Pediatric Brain Tumor Study Group Combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy for CNS germ cell tumors—The Japanese experience. J Neurooncol. 2001;54:311–316. doi: 10.1023/a:1012743707883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Matsutani M. Treatment of intracranial germ cell tumors: The second phase II study of Japanese GCT study group. Neuro Oncol. 2008;10:420–421. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fujimaki T, Matsutani M, The Japanese Pediatric Brain Tumor Study Group HCG-producing germinoma: Analysis of Japanese Pediatric Brain Tumor Study Group results. Neurooncol. 2005;7:518. abstr G5. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Balmaceda C, Heller G, Rosenblum M, et al. Chemotherapy without irradiation—A novel approach for newly diagnosed CNS germ cell tumors: Results of an international cooperative trial. The First International Central Nervous System Germ Cell Tumor Study. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2908–2915. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.11.2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kellie SJ, Boyce H, Dunkel IJ, et al. Intensive cisplatin and cyclophosphamide-based chemotherapy without radiotherapy for intracranial germinomas: Failure of a primary chemotherapy approach. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;43:126–133. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Calaminus G, Kortmann R, Worch J, et al. SIOP CNS GCT 96: Final report of outcome of a prospective, multinational nonrandomized trial for children and adults with intracranial germinoma, comparing craniospinal irradiation alone with chemotherapy followed by focal primary site irradiation for patients with localized disease. Neuro Oncol. 2013;15:788–796. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/not019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bartels U, Onar-Thomas A, Patel SK, et al. Phase II trial of response-based radiation therapy for patients with localized germinoma: A Children's Oncology Group Study. Neuro Oncol. 2022;24:974–983. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Worawongsakul R, Sirachainan N, Rojanawatsirivej A, et al. Carboplatin-based regimen in pediatric intracranial germ-cell tumors (IC-GCTs): Effectiveness and ototoxicity. Neurooncol Pract. 2020;7:202–210. doi: 10.1093/nop/npz043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Afzal S, Wherrett D, Bartels U, et al. Challenges in management of patients with intracranial germ cell tumor and diabetes insipidus treated with cisplatin and/or ifosfamide based chemotherapy. J Neurooncol. 2010;97:393–399. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-0033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wong J, Goddard K, Laperriere N, et al. Long term toxicity of intracranial germ cell tumor treatment in adolescents and young adults. J Neurooncol. 2020;149:523–532. doi: 10.1007/s11060-020-03642-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cheng S, Kilday JP, Laperriere N, et al. Outcomes of children with central nervous system germinoma treated with multi-agent chemotherapy followed by reduced radiation. J Neurooncol. 2016;127:173–180. doi: 10.1007/s11060-015-2029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kanamori M, Takami H, Suzuki T, et al. Necessity for craniospinal irradiation of germinoma with positive cytology without spinal lesion on MR imaging—A controversy. Neuro Oncol Adv. 2021;3:vdab086. doi: 10.1093/noajnl/vdab086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Friedman JA, Lynch JJ, Buckner JC, et al. Management of malignant pineal germ cell tumors with residual mature teratoma. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:518–523. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200103000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Weiner HL, Lichtenbaum RA, Wisoff JH, et al. Delayed surgical resection of central nervous system germ cell tumors. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:727–734. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200204000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murray MJ, Bartels U, Nishikawa R, et al. Consensus on the management of intracranial germ-cell tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:e470–e477. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00244-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Michaiel G, Strother D, Gottardo N, et al. Intracranial growing teratoma syndrome (iGTS): An international case series and review of the literature. J Neurooncol. 2020;147:721–730. doi: 10.1007/s11060-020-03486-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Grabois MF, de Oliveira EXG, Carvalho MS. Childhood cancer and pediatric oncologic care in Brazil: Access and equity. Cad Saude Publica. 2011;27:1711–1720. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2011000900005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grabois MF, de Oliveira EXG, Sá Carvalho M. Assistencia ao cancer entre criancas e adolescentes: Mapeamento dos fluxos origem-destino no Brasil. Rev Saude Publica. 2013;47:368–378. doi: 10.1590/S0034-8910.2013047004305. Portuguese. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baroni LV, Oller A, Freytes CS, et al. Intracranial germ cells tumour: A single institution experience in Argentina. J Neurooncol. 2021;152:363–372. doi: 10.1007/s11060-021-03709-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lo AC, Hodgson D, Dang J, et al. Intracranial germ cell tumors in adolescents and young adults: A 40-year multi-institutional review of outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020;106:269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rajagopal R, Leong SH, Jawin V, et al. Challenges in the management of childhood intracranial germ cell tumors in middle-income countries: A 20-year retrospective review from a single tertiary center in Malaysia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2021;43:e913–e923. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000002116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Amayiri N, Sarhan N, Yousef Y, et al. Feasibility of treating pediatric intracranial germ cell tumors in a middle-income country: The Jordanian experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2022;69:e30011. doi: 10.1002/pbc.30011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]