Abstract

PURPOSE

The aim of this study was to document the available resources and needs for the detection, diagnosis, and treatment of retinoblastoma (RB) in Ethiopia.

METHODS

A health services needs assessment focused on RB care in Ethiopia was conducted. Information was obtained through a web-based survey and field visits. Facilities offering RB service delivery were categorized into three tiers, on the basis of the ability to detect (tier 1) and manage simple (tier 2) or complex (tier 3) patients with RB. Descriptive statistics were performed to quantify human and material resources available at each facility.

RESULTS

The web survey received 29 responses from ophthalmologists at 19 health care facilities. Of the 19 units surveyed, seven (36.8%) had an ophthalmologist dedicated to RB treatment, classifying them as either a tier 2 or 3 facility. All tier 3 facilities had an affiliated health facility offering access to off-site pediatric oncology and pathology services. Of the focal therapies offered at tier 3 facilities, none included local chemotherapy or brachytherapy. Enucleation was offered at all tier 2 facilities, but availability of orbital implants and ocular prostheses was variable. None of the health facilities offered genetics services.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrated that the human and material resources needed for RB care in Ethiopia are constrained. Tier 3 RB facilities are rare and concentrated in urban areas, which could make it difficult for many patients to access. With focused capacity-building efforts, it is possible to increase the efficiency of RB therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Retinoblastoma (RB) is the most common intraocular malignancy of childhood.1 It represents approximately 4% of all pediatric malignancies.2 Two thirds of patients are diagnosed before age 2 years, and 95% before age 5 years.3 The burden of disease is highest in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where an estimated 82% of all children with cancer reside.4

CONTEXT

Key Objective

What are the retinoblastoma (RB)-specific nationwide resources of Ethiopian institutions and their distribution?

Knowledge Generated

The assessment revealed that the human and material resources needed for RB care were technically available but could have been more cohesive in their varied distribution among care facilities.

Relevance

To our knowledge, this is Ethiopia's first RB care assessment. The generated data can help develop a targeted national strategy for RB management.

Although RB is relatively easy to diagnose and treat, early detection and survival with good ocular outcome are fairly uncommon in resource-limited contexts. In LMICs, presentation is often late and characterized by orbital involvement and metastasis.5-7 Specifically in sub-Saharan Africa, survival from RB is <30%, because of late presentation associated with delays in diagnosis of more than 24 months.2,8 Cancer relapse and metastasis are common; abandonment of therapy is observed in 30%-40% of patients, contributing further to poor outcomes.9,10 Early detection of disease, high-quality and accessible ophthalmic and oncologic resources, and strong interdisciplinary teams have led to >90% chance of survival in well-resourced nations.11-13

Published clinical guidelines for RB care generally suggest that referral of suspect patients with RB to a specialized center should ideally occur within 72 hours of identification.14,15 The successful management of RB requires a multidisciplinary team of well-trained ophthalmologists, pediatric oncologists, nurses, pathologists, radiologists, and radiation oncologists, as well as infrastructure and equipment to support basic diagnostics and multimodal therapy.14,15 The management of RB requires rigorous follow-up and, at times, aggressive treatment. In cases where survival is not possible, palliative care is essential to support end of life.

In a microsimulation of global childhood cancer incidence, the estimated total incident patients with RB in Eastern Africa is 2,310, the second highest after Western Africa with 7,824.16 In Ethiopia, the total number of incident patients with RB in 2015 was estimated to be 50516; by birth cohort analysis, the number of annual new RB diagnoses is estimated to be 193.17 It is unclear if and to what extent Ethiopia's public health system, the primary source of health care for the general population, is equipped to manage this relatively large RB population. Ethiopia's public health system is governed by a 20-year health sector development strategy implemented through successive 5-year health sector development programmes.18 A number of private clinics and hospitals exist in parallel to the public system, primarily in urban areas. Yet, an estimated 80% of children with cancer in Ethiopia are still not being diagnosed or referred to a pediatric hematology-oncology treatment center.19 There is no cancer registry in the country, making it difficult to inform health resource planning for cancer management.

The current needs assessment study is a crucial first step in understanding the available human and material resources available for RB management in Ethiopia. Generating these data is essential to improving the national survival of RB by informing the development of a targeted, national strategy for RB management.

METHODS

Study Design

This cross-sectional study was conducted as a part of a larger study titled “Health Systems, Treatment, and Outcomes of RB in Ethiopia, and Mental Health of Primary Caregivers” with ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of Addis Ababa University (Protocol No. 101/17/Oph). Informed consent was obtained from parents or guardians of the participants. The article represents original and valid work and that neither this article nor one with substantially similar content under our authorship has been published or is being considered for publication elsewhere. We agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All identifying information of patients involved in the study has been appropriately anonymized.

Study Setting

Ethiopia, a Federal Democratic Republic established under a 1994 constitution, is composed of nine regional states and two city administrations. The Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) governs a health care delivery system consisting of three levels. The primary level of care comprises a primary hospital (serving a catchment area of 60,000-100,000 people), health centers (serving a catchment area of 15,000-25,000 people), and health posts (serving a catchment area of 3,000 to 5,000 people). Each primary hospital supports five health centers; in rural settings, each health center then in turn supports five health posts (there are no health posts in urban areas). The secondary level of care is provided by general hospitals (serving a catchment of 1.5 million people), and the tertiary level of care is composed of specialized hospitals (serving a catchment area of 3.5 to 5 million people; Data Supplement [File 1]).

The study was focused on eye care units; as the primary signs of RB (ie, leukocoria, proptosis, strabismus) affect the eye, it is expected that patients with RB will first present to an eye center. Eye care is structured with primary, secondary, and Tertiary Eye Care Units (TECUs), aligned with the FMOH levels of care. Primary Eye Care Units (PECUs) are staffed with an ophthalmic nurse or an Integrated Eye Care Worker and provide mainly preventative or promotive services. Secondary Eye Care Units (SECUs) are staffed with an ophthalmologist or cataract surgeon, and the service provision mainly focuses on cataract, refraction, trachoma, and glaucoma. TECUs are staffed with at least two subspecialist ophthalmologists and provide subspecialty services. There are seven TECUs (five public and two private), 47 SECUs, and 547 PECUs available in the country. It is not known if TECUs or SECUs are sufficiently staffed and resourced to provide comprehensive RB care.

Study Participants

This was a two-part, sequential study consisting of a web-based survey and field visits. To identify eligible participants, first, a list of health facilities was created by the authors F.W. and S.T.S. after consultation with the office of Ophthalmological Society of Ethiopia (OSE) and the FMOH. The health facilities met the following inclusion criteria: (1) government, private for-profit, or nongovernmental organizations (NGOs); (2) located in any of the nine regional states or two city administrations of Ethiopia; and (3) provide child eye health services with or without pediatric oncology services. Next, the OSE membership list was cross-referenced to identify ophthalmologists currently practicing in any of the identified health facilities. These ophthalmologists were contacted by e-mail and invited to complete the web-based survey. Field visits followed for health facilities that had at least one ophthalmologist staff member complete the survey; facilities with incomplete data were excluded from the analysis. A support letter was written by the FMOH to the health facilities by the responsible bodies to encourage participation.

Data Collection

Survey.

The web-based survey (Data Supplement [File 2]) was distributed to all members of the OSE by e-mail in January 2018. Resource availability, on-site/off-site location, and confidence of use were collected. The availability of services for children's eye health, in general, and RB, in particular, was queried. Reminder e-mails were sent requesting the completion of the survey.

Field visits.

Data focusing on the available human and material resources available to manage RB (Data Supplement [File 3]) were obtained through field visits to the included facilities and interviews with selected delegates. The data were supplemented by consulting with publications from the FMOH.

Data Cleaning and Analysis

Data were cleaned by checking for the range and structure of answers. A selected set of checks was used to ensure internal consistency. Web survey and field visit data were categorized into human resources, material resources (ie, diagnostic and therapeutic), and patient burden. The International Society of Pediatric Oncology-Pediatric Oncology in Developing Countries guidelines for RB20 were consulted to guide the development of an asset-based tier categorization system for RB service delivery. RB service delivery was categorized into three tiers.

Tier 1: no availability of an ophthalmologist dedicated to treat RB.

Tier 2: availability of an ophthalmologist, examination under anesthesia, enucleation, chemotherapy, and ophthalmic pathology; no availability of focal treatment modalities (therefore no opportunities for ocular salvage).

Tier 3: all tier 2 resources plus eye-sparing therapies for treatment of intraocular disease (ie, chemotherapy and focal therapies) and radiotherapy for treatment of extraocular disease.

Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage) were reported for survey questions.

RESULTS

Study Participants

Twenty health facilities were eligible for the study and included seven TECUs (four public, three private) and 13 SECUs (four public, seven private). From the 157 members of OSE, 43 ophthalmologists were working at the eligible health facilities at the time of the study. In total, 29 of 43 ophthalmologists (67.4% response rate) successfully completed the survey. Some feedback was obtained from those who declined participation; they noted that poor internet access and technical difficulty in completing the survey precluded their participation. The 29 study survey participants represented 19 of 20 eligible health facilities; one of the TECUs (one public) was excluded from the analysis because of incomplete data on the web survey.

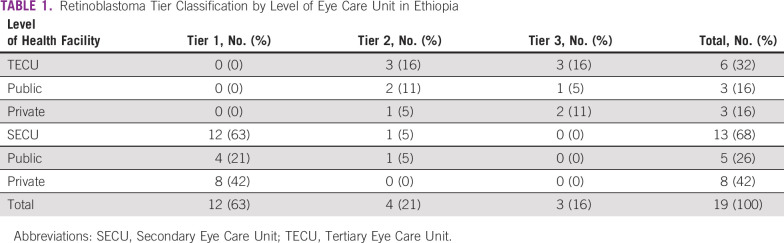

RB Facility Tiers

Of all facilities evaluated, 3 of 19 (16%) were tier 3, 4 of 19 (21%) were tier 2, and 12 of 19 (63%) were tier 1 (Table 1). Of the six TECUs, three (one public, two private) fulfilled tier 3 RB facility status and three (two public, one private) fulfilled tier 2 status. Of the 13 SECUs, one (public) fulfilled tier 2 status and 12 (four publics, eight private) fulfilled tier 1 status.

TABLE 1.

Retinoblastoma Tier Classification by Level of Eye Care Unit in Ethiopia

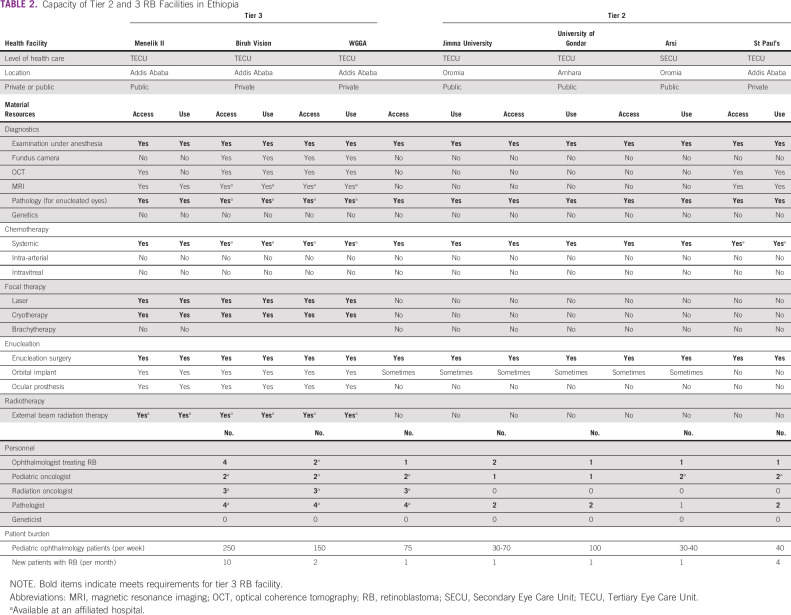

All tier 3 facilities were located in Addis Ababa (Table 2). Only three regions (Addis Ababa, Amhara, and Oromia) had a tier 2 or 3 RB facility; the majority (4 of 7, 57.1%) were located in Addis Ababa. A map of tier 2 and 3 RB facilities is provided in the Data Supplement ([File 4]).

TABLE 2.

Capacity of Tier 2 and 3 RB Facilities in Ethiopia

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Resources in Tier 2 and 3 RB Facilities

Table 2 summarizes the specific resources available for RB care at tier 2 and 3 RB facilities. Although all tier 3 facilities had ocular ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) available for diagnostics, just two, both private, had a fundus camera available. Of the focal therapies offered at tier 3 facilities, none included local chemotherapy or brachytherapy. Enucleation was offered with orbital implant and ocular prosthesis at all tier 3 centers. All the tier 3 facilities had access to off-site pathology services. External Beam Radiation Therapy was available in all tier 3 facilities.

Most (2 of 3) tier 2 facilities had an ocular ultrasound, and one (private) had OCT and MRI; however, none had a fundus camera. Systemic chemotherapy was available at 3 of 4 tier 2 facilities (a requirement for tier 3 only), but 0 of 4 had focal therapies, precluding eye salvage. Although enucleation was available at all tier 2 facilities, orbital implants and ocular prosthesis availability were either inconsistent or not available at all. Pathology was offered on-site at 4 of 4 (100%) tier 2 facilities. No tier 2 or 3 facility offered genetics services (Table 2).

Human Resources in Tier 2 and 3 RB Facilities

Of the 19 units surveyed in the study, seven (36.8%) had an ophthalmologist who treated RB, classifying them as either a tier 2 or 3 facility (Table 2). These were 6 of 6 TECUs and 1 of 13 SECUs (Table 2). Although all tier 3 facilities had a pediatric oncologist and pathologist providing care to patients with RB, they were located off-site at an affiliated health facility.

Just 2 of 4 (50%) tier 2 facilities (both public TECUs) had a pediatric oncologist. Pathologists were available at 3 of 4 (75%) tier 2 facilities. None of the facilities had geneticists or genetic counselors (Table 2).

Tier 1 facilities had no personnel dedicated to RB treatment and management (Data Supplement [File 5]).

Patient Burden

The pediatric ophthalmology patients seen per week ranged from 75 to 250/week at tier 3 facilities and 30-100 at tier 2 facilities (Table 2). The number of new RB patients seen per month ranged from 10 patients per month at the public tier 3 facility and one patient/month at the private tier 3 facility. Public tier 2 facilities saw an average of one new patient with RB per month, and the private tier 2 facility saw four patients with RB per month (Table 2).

Tier 1 facilities reported seeing 10-150 pediatric ophthalmology patients per week and an average of 0-2 patients with RB per month (Data Supplement [File 5]).

DISCUSSION

Despite the significant documented burden of RB in Ethiopia, a clear understanding of the human and material resources for health available for the management of RB has been lacking. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study performed to evaluate multidisciplinary capacity in Ethiopia for managing RB.

Having enough personnel with the requisite training and well-equipped facilities to provide quality, evidence-based RB service remains a major challenge in Ethiopia. Investment in cancer infrastructure should cover the entire range from prevention to palliative care.21 The minimum clinical requirements for a full package of curative RB treatment include a dedicated ophthalmologist with adequate skill in eye enucleation in children; safe pediatric anesthesiology to facilitate diagnosis and treatment; pathology services and a pathologist to evaluate the extent of extraocular involvement; a pediatric oncologist familiar with chemotherapy administration and management of its side effects; focal therapies, when eye salvage is possible; and radiotherapy for management of extraocular disease.22,23 In our study, we noted that human and material resources needed for RB diagnosis and treatment were technically available, but somewhat fragmented in their varied distribution among facilities providing care. Although the 19 facilities covered in our study provided specialized pediatric ophthalmology services, just seven of them (six TECUs and one SECU) had an ophthalmologist trained to provide RB care. Furthermore, of all nine regions and two administrative cities in Ethiopia, only two regions (Amhara and Oromia) and one city administration (Addis Ababa) had a facility that met our study's criteria for tier 2 or 3 RB facility. Our findings are consistent with a web-based assessment of capacity to treat RB in the Middle East, North Africa, and West Asia, which revealed that centralization of resources and cohesive multidisciplinary teams remain the primary gaps in patient care.24

All tier 3 RB facilities were located in the capacity city, Addis Ababa. The restriction of specialty RB care to selected regions and mainly urban settings can pose difficulties to patients living in other parts of the country, particularly rural areas. For example, the additional travel burden may increase the chance of treatment abandonment.25 Furthermore, perceived travel burden may cause delays in seeking or accessing care. Our previous research reveals that Ethiopian patients with RB have an average delay of 5.2 months between presenting to a primary health facility and arriving at a facility able to provide specialized RB care; travel burden was a factor influencing this delay.26 Combined with the findings of the current study, results suggest that building capacity to care for RB in more regions of Ethiopia may reduce treatment delays, thereby improving survival. Our previous study also revealed ineffective referral pathways, as a significant number of patients visited two facilities before reaching a final treatment center, thereby significantly increasing the delay to treatment.26 There is a need to intervene at the health system level to generate effective referral pathways that facilitate timely connection of patients to appropriate care.

Our study indicated that enucleation was the most commonly available curative treatment. Yet, enucleation refusal is common in LMICs, because of complex and interconnected factors such as social stigma, lack of support for the visually impaired, and the belief in alternative medicine or religious rites as potentially curative.27 The availability and use of prosthetic eyes immediately after surgery to avoid an empty socket is a crucial factor for enucleation acceptability and can assist in the elimination of stigma.20 However, within the public facilities, our study revealed that prosthetic eyes and orbital implants were available only at Menelik II hospital, through partners support, limiting their reach to families around the country. Prosthetic eyes are currently available from India for around $10 USD. Ministry of Health initiatives could focus on improving the availability and accessibility of prosthetic eyes in Ethiopian domestic market. Furthermore, the absence of eye salvage treatment options, like laser and cryotherapy, in the majority of health facilities might contribute to mistrust of the health system and intensify enucleation refusal by prompting parents to shop around and seek care at one of the few centers where focal therapy was offered.

The use of radiotherapy for RB treatment remains important in LMICs, where a greater proportion of patients present with extraocular disease; radiotherapy is often the only curative option. Although all three tier 3 facilities had radiotherapy available (Table 2), this was through collaboration with a single affiliate hospital. Radiotherapy access is limited in much of sub-Saharan Africa and remains a challenge for overall cancer management.28-30

Because of the complex, specialized care that children with RB need, referral to TECU is often the first step. But three of the TECUs in this study did not fulfill the tier 3 RB facility classification, which may impede swift management of patients with RB. Our data reveal that two public and one private TECUs could be upgraded from tier 2 to tier 3 status by simply improving capacity to deliver radiotherapy and focal therapy. This would have a great impact for patients living outside Addis Ababa, particularly Amhara and Oromia regions (Table 2). The one SECU in our study that met tier 2 status could undergo a similar capacity improvement for radiotherapy and focal therapy and expand to offer systemic chemotherapy.

In tier 3 RB facilities, there were seven ophthalmologists providing care to patients with RB, yet radiotherapy, oncology, and pathology were often provided through affiliate hospitals, possibly reflective of an overall health human resource shortage. Tier 2 RB facilities contributed an additional five ophthalmologists, for a total of 12 serving the estimated 193 new patients per year. When considering that patients with RB need ophthalmology follow-up into adulthood, 12 ophthalmologists do not appear enough to serve the entire RB population in the country. In Ethiopia, currently, there are five ophthalmology residency programs, which include some training on RB, specifically interpretation of diagnostic testing (ie, B-scan ultrasound and radiology) and enucleation surgery. However, there is no local subspecialty fellowship for pediatric ophthalmology or RB, and such training must be sought at foreign institutions. Furthermore, ocular oncology is not a recognized subspeciality in Ethiopia. There is one pediatric hematology and oncology fellowship program in the country, delivered by Addis Ababa University. A pediatric ophthalmology fellowship program, which will include training for RB, is currently under development at Addis Ababa University in collaboration with the University of Toronto.31 These two fellowship programs are expected to help to fill the shortage of pediatric oncologists and ophthalmologists required for management of RB.

The study was limited by the fact that we did not collect information pertaining to the supportive and palliative care for RB, nor did we evaluate quality of care provided at any of the facilities. These could be assessed in future studies as capacity building initiatives are implemented and monitored. Since the study was focused on eye care units, it is possible that patients with RB presenting only at oncology centers might have been missed in the calculation of patient burden. In addition, because of a lack of data on the incidence of RB at the district level, it was difficult to relate the available resources to the patient burden in each district. Finally, this study was not designed to provide insight into centralization or decentralization of certain services related to the care of patients with RB; these could be addressed by future studies.

In conclusion, this study showed that there are limitations to human and material resources required for RB diagnosis and therapy in Ethiopia. Tier 3 RB facilities are few and centralized in urban settings, potentially presenting access challenges for many patients. However, there are opportunities to create more efficiency in RB treatment through targeted capacity-building efforts. Following a successful national strategy model used in Kenya,32 a national policy for RB is being drafted in Ethiopia, with involvement from all relevant stakeholders (ie, health care staff, eye care NGOs, and the government). This initiative holds promise to address the capacity needs for RB care in Ethiopia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge the executive Committee members of The Ophthalmological Society of Ethiopia and focal eye persons at the Ministry of Health. Special appreciation goes to Dr Sosina H/Mariam, Sr Tsehaynesh Tiruneh, and W/O Azeb Kebede for their outstanding role during data collection.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Sadik Taju Sherief, Fran Wu, Tiliksew Teshome

Administrative support: Fran Wu

Provision of study materials or patients: Fran Wu, Tiliksew Teshome

Collection and assembly of data: Sadik Taju Sherief, Fran Wu, Tiliksew Teshome

Data analysis and interpretation: Sadik Taju Sherief, Fran Wu, Tiliksew Teshome, Helen Dimaras

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jubran RF, Erdreich-Epstein A, Butturini A, et al. Approaches to treatment for extraocular retinoblastoma: Children's Hospital Los Angeles experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;26:31–34. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200401000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bowman RJ, Mafwiri M, Luthert P, et al. Outcome of retinoblastoma in east Africa. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:160–162. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stiller CA, Parkin DM. Geographic and ethnic variations in the incidence of childhood cancer. Br Med Bull. 1996;52:682–703. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Cancer Society . Global Cancer Facts & Figures. ed 4. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Badhu B, Sah SP, Thakur SK, et al. Clinical presentation of retinoblastoma in Eastern Nepal. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;33:386–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2005.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Owoeye JF, Afolayan EA, Ademola-Popoola DS. Retinoblastoma—A clinico-pathological study in Ilorin, Nigeria. Afr J Health Sci. 2006;13:117–123. doi: 10.4314/ajhs.v13i1.30825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schultz KR, Ranade S, Neglia JP, et al. An increased relative frequency of retinoblastoma at a rural regional referral hospital in Miraj, Maharashtra, India. Cancer. 1993;72:282–286. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930701)72:1<282::aid-cncr2820720149>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gichigo EN, Kariuki-Wanyoike MM, Kimani K, et al. Retinoblastoma in Kenya: Survival and prognostic factors. Ophthalmologe. 2015;112:255–260. doi: 10.1007/s00347-014-3123-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Friedrich P, Lam CG, Itriago E, et al. Magnitude of treatment abandonment in childhood cancer. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Naseripour M. “Retinoblastoma survival disparity”: The expanding horizon in developing countries. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2012;26:157–161. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Canturk S, Qaddoumi I, Khetan V, et al. Survival of retinoblastoma in less-developed countries impact of socioeconomic and health-related indicators. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:1432–1436. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.168062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurwitz R, Shields C, Shields J, et al. Retinoblastoma. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. ed 7. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2016. pp. 699–715. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shields CL, Shields JA. Recent developments in the management of retinoblastoma. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1999;36:8–9. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19990101-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Canadian Retinoblastoma Society National Retinoblastoma Strategy Canadian Guidelines for Care: Strategie therapeutique du retinoblastome guide clinique canadien. Can J Ophthalmol. 2009;44:S1–S88. doi: 10.3129/i09-194. suppl 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ministry of Health Kenya 2014. http://guidelines.health.go.ke/#/category/6,7/4/meta Retinoblastoma Best Practice Guidelines.

- 16. Ward ZJ, Yeh JM, Bhakta N, et al. Global childhood cancer survival estimates and priority-setting: A simulation-based analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:972–983. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dimaras H, Corson TW, Cobrinik D, et al. Retinoblastoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15021. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health . Health Sector Development Plan IV (HSDP IV) 2010/11-2014/15. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Ministry of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hailu D, Fufu Hordofa D, Adam Endalew H, et al. Training pediatric hematologist/oncologists for capacity building in Ethiopia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67:e28760. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chantada G, Luna-Fineman S, Sitorus RS, et al. SIOP-PODC recommendations for graduated-intensity treatment of retinoblastoma in developing countries. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:719–727. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta S, Howard S, Hunger S, et al. Treating childhood cancer in low- and middle-income countries Gelband H, Jha P, Sankaranarayanan R.Cancer: Disease Control Priorities ed 3Washington, DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 137-1402015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schvartzman E, Chantada G, Fandino A, et al. Results of a stage-based protocol for the treatment of retinoblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1532–1536. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.5.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mustafa MM, Jamshed A, Khafaga Y, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with vincristine, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide in the treatment of postenucleation high risk retinoblastoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1999;21:364–369. doi: 10.1097/00043426-199909000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burges M, Qaddoumi I, Brennan RC, et al. Assessment of retinoblastoma capacity in the Middle East, North Africa, and West Asia region JCO Glob Oncol 10.1200/GO.20.00321, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mirutse MK, Tolla MT, Memirie ST, et al. The magnitude and perceived reasons for childhood cancer treatment abandonment in Ethiopia: From health care providers' perspective. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22:1014. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08188-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sherief ST, Wu F, O’Banion J, et al. Referral patterns for retinoblastoma patients in Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23:172. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09137-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Olteanu C, Dimaras H. Enucleation refusal for retinoblastoma: A global study. Ophthalmic Genet. 2016;37:137–143. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2014.937543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Abdel-Wahab M, Bourque JM, Pynda Y, et al. Status of radiotherapy resources in Africa: An International Atomic Energy Agency analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e168–e175. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70532-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morhason-Bello IO, Odedina F, Rebbeck TR, et al. Challenges and opportunities in cancer control in Africa: A perspective from the African Organisation for Research and Training in Cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e142–e151. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70482-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schroeder K, Saxton A, McDade J, et al. Pediatric cancer in northern Tanzania: Evaluation of diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes JCO Glob Oncol 10.1200/JGO.2016.009027, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kletke SN, Soboka JG, Dimaras H, et al. Development of a pediatric ophthalmology academic partnership between Canada and Ethiopia: A situational analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:438. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02368-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hill JA, Kimani K, White A, et al. Achieving optimal cancer outcomes in East Africa through multidisciplinary partnership: A case study of the Kenyan National Retinoblastoma Strategy group. Glob Health. 2016;12:23. doi: 10.1186/s12992-016-0160-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.