Abstract

This case report describes a 12-year-old Arabian mare with granulocytic ehrlichiosis. Clinical signs included fever, apathy, anorexia, icterus, limb edema, and reluctance to move. Examination of buffy coat smears revealed Ehrlichia organisms in neutrophils and eosinophils. A band of 1,428 bp was amplified from DNA of leukocytes via nested PCR and was identified as part of the Ehrlichia 16S rRNA gene. It differed from the gene sequences of Ehrlichia phagocytophila and E. equi at two and three positions, respectively. Interestingly, the nucleotide sequence of the 16S rRNA was 100% identical to that of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis.

Equine granulocytic ehrlichiosis (EGE) is a generalized disease of horses characterized by seasonal occurrence and fever and caused by an organism that is closely related to the Ehrlichia phagocytophila genogroup. Equine ehrlichiosis has been reported in the United States (7), Germany (4), Switzerland (8), Sweden (3), and Great Britain (10, 14). Because of the seasonality of the disease, vector-associated transmission has long been suspected; recently, the causative agent was identified in ticks of the species Ixodes (19). Characteristic clinical signs include fever, depression, lethargy, limb edema, petechia, icterus, ataxia, and reluctance to move (13). Often, there is leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia, and the causative organisms may be detected in neutrophils and less often in eosinophils. The diagnosis of EGE is based on clinical signs and identification of Ehrlichia organisms in blood smears. EGE may be diagnosed retrospectively based on seroconversion as determined by indirect immunofluorescence of paired serum samples (12). Specific and sensitive molecular methods for identifying Ehrlichia DNA have recently been described (2, 6, 16).

At present, sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene is used for Ehrlichia taxonomy (20). Although EGE has been reported in many European countries, there is little data concerning sequencing of isolates. In 1995, the causative agent of granulocytic ehrlichiosis in horses and dogs in Sweden was identified and found to be closely related to Ehrlichia phagocytophila and E. equi, based on its nucleotide sequence (9).

This case report describes a horse with granulocytic ehrlichiosis. The causative agent was characterized via PCR and sequencing of the cloned PCR product.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient.

A 12-year-old Arabian mare from an area where ticks are endemic was referred to the Clinic of Large Animal Medicine and Surgery, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, because of colic. The mare underwent surgery for correction of volvulus of the jejunum and had an uneventful recovery. Twelve days after the operation, the mare had clinical signs of ehrlichiosis. At that time, the horse was not receiving any medication.

Clinical, hematological, and serological examinations.

The horse underwent a thorough clinical examination, and blood was collected for determination of a complete blood count and the concentrations of plasma protein and fibrinogen. Paired serum samples were examined for antibody to E. phagocytophila via indirect immunofluorescence on day 1 and 30 days later (17).

PCR, cloning, and sequencing.

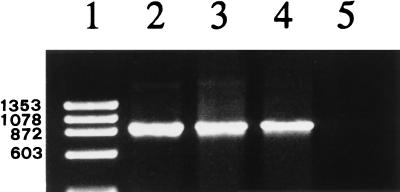

A washed leukocyte pellet was obtained from a sodium citrate blood sample. DNA isolation and the nested-PCR procedure were done as described previously (16). PCR products were resolved on a 1.2% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and examined under UV illumination. The DNAs of E. phagocytophila (Swiss strain) and a recent canine granulocytic Ehrlichia isolate (18) were used as positive controls.

The amplified DNA was extracted from the gel by using a Geneclean Spin Kit (BIO 101, Vista, Calif.). Cloning was done with the pGEM T Vector System (Promega, Wallisellen, Switzerland) and Escherichia coli JM 109. Purification of the plasmid DNA was carried out by using a commercial plasmid kit (Qiagen, Basel, Switzerland).

For bidirectional DNA sequencing of the insert, the following primers were used: for the pGEM T Vector, SP6 (5′-ATTTAGGTGACACTATAGAATAC-3′) and T7 (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGA-3′); for the plus strand, EE-3 (5′-GTCGAACGGATTATTCTTTATAGCTTGC-3′) and EP-751 (5′- GATACCCTGGTAGTCCAC-3′); for the minus strand, EE-4 (5′-CCCTTCCTGTAAGAAGGATCTAATCTCC-3′), EP-1324 (5′-CGATTACTAGCGAATCCGAC-3′), and Nic-1 (GGCTCATCTAATAGCGAT-3′). The nucleotide sequence was detected with a fluorescence-based automated sequencing system (ABI 377A DNA sequencer) by Microsynth, Balgach, Switzerland.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The 16S RNA sequence of the horse isolate described here has been deposited in the GenBank database and assigned accession no. AF057707.

RESULTS

Clinical, hematological, and serological findings.

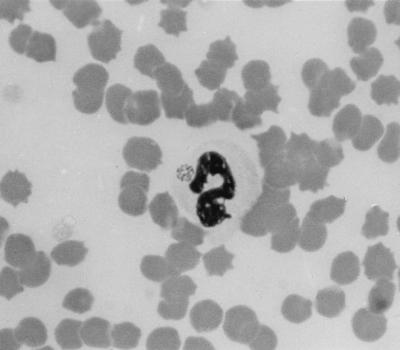

Clinical examination of the horse revealed apathy, anorexia, and a rectal temperature of 39.6°C. Heart and respiratory rates, intestinal motility, and fecal consistency were normal. The mucous membranes were mildly icteric, and the capillary refill time was 2 s. The horse was reluctant to move and had bilateral hind limb edema. There was no evidence of ataxia. No ticks were found on the horse at the time of examination. There was marked leukocytosis (16,100 cells/μl) with absolute neutrophilia. The number of thrombocytes was in the low normal range (110,000 platelets/μl). Other hematological parameters and the concentrations of protein and fibrinogen in plasma were normal. Ehrlichia organisms were identified in neutrophils and eosinophils (Fig. 1), and the infection rate was 6% (966 infected leukocytes/μl of blood). The horse was treated with 10 mg of oxytetracycline (Engemyzin 10%; Veterinaria AG, Zurich, Switzerland) per kg of body weight administered intravenously once a day for 5 days. The general condition of the horse improved markedly 12 h after initiation of treatment; the rectal temperature returned to normal, and the limb edema decreased.

FIG. 1.

Ehrlichia organisms in a neutrophil of a 12-year-old Arabian mare. Buffy coat smear; May-Grünwald Giemsa stain. Magnification, ×1,000.

On day 1, the titer of antibody to E. phagocytophila was 20. Thirty days later, the horse had seroconverted, with a fourfold rise in the indirect immunofluorescent-antibody titer to 320.

DNA sequencing.

The DNA isolated from the organisms from the horse was compared to that isolated from a cow infected with E. phagocytophila and that from a dog infected with the agent of granulocytic ehrlichiosis. The nested PCR and subsequent electrophoresis yielded distinct bands identical in size from all three isolates (Fig. 2). Sequencing of the cloned 1,428-bp PCR product of the horse identified it as part of the 16S rRNA gene of Ehrlichia spp. The nucleotide sequence of the 16S rRNA gene of the horse differed from the gene sequences of E. phagocytophila and E. equi (1) at two and three positions, respectively (Table 1). The sequence was 100% identical to the gene sequence of a human granulocytic ehrlichia (5) and that of a recently described Ehrlichia species of dogs (18).

FIG. 2.

Ethidium bromide-stained 1.2% agarose gel with amplification products of nested PCR. Lanes: 1, molecular size standard marker with molecular sizes (in daltons) indicated on the left (ΦX174 digested with HaeIII); 2, horse isolate; 3, E. phagocytophila isolate; 4, granulocytic Ehrlichia isolate of a dog; 5, water (negative control).

TABLE 1.

Differences among nucleotide sequences of the 16S rRNA genes of an equine Ehrlichia isolate, E. phagocytophila, E. equi, a human granulocytic ehrlichia isolate, and a canine granulocytic ehrlichia isolate

DISCUSSION

Sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene has been widely used for the phylogenetic examination and taxonomical classification of numerous bacteria (15). Molecular analysis is the method of choice for the identification and classification of bacteria that cannot be cultured or characterized by conventional methods, such as Ehrlichia spp. Clinical, hematological, and serological findings and the morphology of the causative agent are not sufficient for the differentiation of closely related members of the E. phagocytophila genogroup. In this study, the nucleotide sequence of the 16S rRNA gene was identified, via PCR and subsequent sequencing of the cloned product, as a segment of the Ehrlichia 16S rRNA gene.

The clinical history of the horse in this study and the onset of the disease seemed unique. Clinical signs appeared 12 days after a colic operation, during the convalescence period, when no medication was being administered. We assume that immunosuppression, attributable to the colic and the operation, played a role in the pathogenesis of ehrlichiosis. In the present case, clinical signs apparently were first recognized at a relatively early stage. The symptoms observed were indicative of a mild, yet typical, form of granulocytic ehrlichiosis (13). The hematological changes were minimal, and the final diagnosis was based on the identification of Ehrlichia organisms in neutrophils and eosinophils. The seroconversion observed indicated that the agent is a member of the E. phagocytophila genogroup.

Over the last several years, the diagnosis of ehrlichiosis has been improved considerably with the introduction of PCR (1, 3, 5). The two primer pairs used in this study allowed us to extend the diagnostic spectrum to the entire E. phagocytophila group (2, 16). As expected, DNA fragments equal in size were amplified with simple and nested PCRs from the horse isolate and from the two controls, the E. phagocytophila and canine isolates. This suggested a marked homology among the organisms involved. Partial sequencing of the PCR product allowed us to identify the horse isolate. The nucleotide sequence differed from those of E. phagocytophila and E. equi at two and three positions, respectively. However, the analyzed segment of the 16S rRNA gene of the horse isolate was identical to that of the human granulocytic ehrlichia described by Chen et al. (5) in the United States, to that of the granulocytic ehrlichia of dogs and horses described by Johansson et al. (9) in Sweden, and to that of the recently described granulocytic ehrlichia from dogs in Switzerland (18). In addition, an identical sequence from an unpublished study (11) of an equine isolate was found in GenBank (accession no. U77389). It thus appears that EGE may be caused by at least two closely related but geographically separate species of Ehrlichia. One is E. equi, occurring in the United States, and the other is a granulocytic Ehrlichia closely related to the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, occurring in the United States and in Europe.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Kommission zur Förderung des akademischen Nachwuchses.

We thank Ueli Braun for critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson B E, Dawson J E, Jones D C, Wilson K H. Ehrlichia chaffeensis, a new species associated with human ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2838–2842. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.12.2838-2842.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barlough J E, Madigan J E, DeRock E, Bigornia L. Nested polymerase chain reaction for detection of Ehrlichia equi genomic DNA in horses and ticks (Ixodes pacificus) Vet Parasitol. 1996;63:319–329. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(95)00904-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Björsdorff A, Christensson D, Johnson A, Madigan J E. Program and abstracts of the IVth International Symposium on Rickettsiae and Rickettsial Diseases. 1990. Granulocytic ehrlichiosis in the horse, the first verified cases in Sweden; p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Büscher G, Gandras R, Apel G, Friedhoff K T. Der erste Fall von Ehrlichiosis beim Pferd in Deutschland. Dtsch Tierärztl Wochenschr. 1984;91:408–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen S-M, Dumler J S, Bakken J S, Walker D H. Identification of a granulocytotropic Ehrlichia species as the etiologic agent of human disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:589–595. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.589-595.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engvall E O, Pettersson B, Persson M, Artursson K, Johansson K-E. A 16S rRNA PCR assay for detection and identification of granulocytic Ehrlichia species in dogs, horses, and cattle. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2170–2174. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2170-2174.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gribble D H. Equine ehrlichiosis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1969;155:462–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hermann M, Baumann D, Lutz H, Wild P. Erster diagnostizierter Fall von equiner Ehrlichiose in der Schweiz. Pferdeheilkunde. 1985;1:247–250. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansson K-E, Pettersson B, Uhlén M, Gunnarsson A, Malmqvist M, Olsson E. Identification of the causative agent of granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Swedish dogs and horses by direct solid phase sequencing of PCR products from the 16S rRNA gene. Res Vet Sci. 1995;58:109–112. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(95)90061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korbutiak E, Schneiders D H. First confirmed case of equine ehrlichiosis in Great Britain. Equine Vet Educ. 1994;6:303–304. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liz, J. S., J. W. Sumner, and W. L. Nicholson. 1996. Unpublished data.

- 12.Madigan J E, Hietala S, Chalmers S, DeRock E. Seroepidemiologic survey of antibodies to Ehrlichia equi in horses in northern California. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1990;196:1962–1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madigan J E. Equine ehrlichiosis. Vet Clin N Am Equine Pract. 1993;9:423–428. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0739(17)30408-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNamee P T, Cule A P, Donnelly J. Suspected ehrlichiosis in a gelding in Wales. Vet Rec. 1989;124:634–635. doi: 10.1136/vr.124.24.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsen G J, Woese C, Overbeek R. The winds of (evolutionary) change: breathing new life into microbiology. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1–6. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.1-6.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pusterla N, Huder J, Wolfensberger C, Braun U, Lutz H. Laboratory findings in cows after experimental infection with Ehrlichia phagocytophila. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:643–647. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.6.643-647.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pusterla N, Wolfensberger C, Gerber-Bretscher R, Lutz H. Comparison of indirect immunofluorescence for Ehrlichia phagocytophila and Ehrlichia equi in horses. Equine Vet J. 1997;29:490–492. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1997.tb03165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pusterla N, Huder J, Wolfensberger C, Litschi B, Parvis A, Lutz H. Granulocytic ehrlichiosis in two dogs in Switzerland. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2307–2309. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2307-2309.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richter P J, Kimsey R B, Madigan J E, Barlough J E, Dumler J S, Brooks D L. Ixodes pacificus (Acari: Ixodidae) as a vector of Ehrlichia equi (Rickettsiales: Ehrlichieae) J Med Entomol. 1996;33:1–5. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/33.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rikihisa Y. The tribe Ehrlichieae and ehrlichial diseases. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;4:286–308. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.3.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]