Abstract

Phase-shift droplets provide a flexible and dynamic platform for therapeutic and diagnostic applications of ultrasound. The spatiotemporal response of phase-shift droplets to focused ultrasound, via the mechanism termed acoustic droplet vaporization (ADV), can generate a range of bioeffects. Although ADV has been used widely in theranostic applications, ADV-induced bioeffects are understudied. Here, we integrated ultra-high-speed microscopy, confocal microscopy, and focused ultrasound for real-time visualization of ADV-induced mechanics and sonoporation in fibrin-based, tissue-mimicking hydrogels. Three monodispersed phase-shift droplets—containing perfluoropentane (PFP), perfluorohexane (PFH), or perfluorooctane (PFO)—with an average radius of ∼6 μm were studied. Fibroblasts and tracer particles, co-encapsulated within the hydrogel, were used to quantify sonoporation and mechanics resulting from ADV, respectively. The maximum radial expansion, expansion velocity, induced strain, and displacement of tracer particles were significantly higher in fibrin gels containing PFP droplets compared to PFH or PFO. Additionally, cell membrane permeabilization significantly depended on the distance between the droplet and cell (d), decreasing rapidly with increasing d. Significant membrane permeabilization occurred when d was smaller than the maximum radius of expansion. Both ultra-high-speed and confocal images indicate a hyper-local region of influence by an ADV bubble, which correlated inversely with the bulk boiling point of the phase-shift droplets. The findings provide insight into developing optimal approaches for therapeutic applications of ADV.

Phase-shift droplets, comprising a perfluorocarbon core and a stabilizing shell, have emerged as versatile particles for a wide range of biomedical ultrasound applications1–4 due to their superior stability both in vitro and in vivo compared to conventional contrast microbubbles.5–8 When exposed to focused ultrasound above a certain pressure threshold (i.e., in the megapascal range), phase-shift droplets are transformed into bubbles through a process known as acoustic droplet vaporization (ADV).9 Due to the low surface tension and high vapor pressure of the perfluorocarbon core in phase-shift droplets, ultrasound can trigger a phase transition without substantial generation of heat when the liquid is under tension during the peak rarefactional half cycle of the ultrasound pulse. Earlier studies showed that ADV begins with the formation of a single vapor nucleus within the droplet.10–13 The nucleation site, resulting from pressure amplification due to the superharmonic focusing effect,14 depended on the ratio of droplet size to the incoming wavelength. ADV physics and the effect of critical parameters have been reviewed in prior articles.15–17 The acoustic response of phase-shift droplets can be tailored depending on the perfluorocarbon liquid, droplet size, and acoustic parameters to generate either a stable or transient bubble.15,18 Both ADV-induced stable and transient bubble formation have utility in specific applications. For example, transient bubble formation offers superior localization of the bubble signal from its surrounding between consecutive ultrasound pulses.19 Comparatively, stable bubble formation can be utilized to alter the microstructure of hydrogels20 or modulate drug release kinetics.21 The occurrence of ADV is accompanied by mechanical forces acting on the surrounding media due to the following processes: (i) the rapid volumetric expansion during phase-transition, (ii) subsequent oscillations of the generated bubble during ultrasound (e.g., stable oscillation, inertial cavitation, bubble displacement, and fragmentation), and (iii) further growth of the bubble due to passive diffusion or Ostwald ripening after ultrasound. The ADV-induced expansion factor, defined as the ratio of an expanded bubble during ADV to the corresponding initial droplet diameter, varies greatly depending on the initial diameter of the phase-shift droplet and the bulk boiling point of the perfluorocarbon liquid (i.e., volatility). Using the ideal gas law and the Young–Laplace equation, along with certain assumptions such as negligible gas diffusion during phase conversion, an expansion factor of approximately 5 was reported for droplets larger than 3 μm in diameter in water.22,23

The determination of spatiotemporally occurring mechanics and cellular bioeffects of ADV is critical for developing safe and effective diagnostic and therapeutic applications. The localized mechanical impact associated with acoustic cavitation (i.e., stable and inertial) as well as acoustic radiation forces in the presence of conventional contrast microbubbles have been recognized as important factors in sonoporation, the ultrasound-mediated disruption of a cell membrane. Sonoporation is a promising technique for gene and drug delivery to cells that depends on acoustic parameters and cell type.24–27 While the bioeffects of ultrasound-induced cavitation in the presence of conventional microbubbles have been extensively studied,28–31 our understanding of the bioeffects of ADV bubbles on nearby cells and biological constructs is limited.32 Additionally, most ADV studies have relied on post-ultrasound assays, yielding indirect association of ultrasound parameters with treatment outcome. Due to the inherently complex, microscopic, and transient nature of ADV, real-time assessment of ADV is limited.

Prior studies on the cellular bioeffects of ADV have used lower bulk boiling point phase-shift droplets in conjunction with 2D cell monolayers (i.e., cells on a coverslip or in an Opticell chamber)33 or a cell suspension.34 Although ADV may generate a range of bioeffects, prior studies have primarily focused on sonoporation35 and the stretching of endothelial tight junctions (i.e., blood brain barrier opening)36 for applications in drug/gene delivery. Reversible or irreversible cell membrane permeabilization caused by sonoporation depended on droplet concentration, driving pressure, pulse duration, and droplet to cell distance.33,35,37 However, little is known concerning ADV-induced sonoporation on cell membrane permeability when higher bulk boiling point phase-shift droplets are used. Furthermore, cells in 2D and 3D environments interact differently with their surroundings38 with the latter environment more closely recapitulating native tissue. For tissue regeneration applications, phase-shift droplets are incorporated in 3D tissue-mimicking hydrogels that can be implanted in vivo. A hydrogel, which resembles the extracellular matrix, enables delivery of exogenous cells and facilitates regenerative processes. Therefore, there is a need to study both ADV dynamics and resulting sonoporative effects in 3D in vitro models using tissue mimicking hydrogels.

Here, an integrated approach combining ultra-high-speed microscopy, ultrasound, and time-lapse confocal microscopy was used to spatiotemporally study ADV-generated mechanics and sonoporation in real-time using a 3D in vitro model. We developed fibrin-based acoustically responsive scaffolds (ARSs) containing three phase-shift droplets with different perfluorocarbon cores: perfluoropentane (PFP, bulk boing point: ∼29 °C), perfluorohexane (PFH, bulk boing point: ∼56 °C), and perfluorooctane (PFO, bulk boing point: ∼100 °C). Higher bulk boiling point droplets offer enhanced thermal stability and distinct ADV dynamics, leading to their predominant use in tissue regeneration applications. To study the full-field mechanical deformations induced by ADV, tracer particles were co-encapsulated within ARSs. ADV-induced mechanics and downstream sonoporative effects were assessed by employing ultra-high-speed imaging of up to 10 × 106 frames per second and tracking the displacement of tracer particles during and after ultrasound. Additionally, we employed time-lapse, 3D confocal microscopy to study the effect of ADV on cell membrane permeability in real time. The combination of these microscopy techniques provides a mechanistic understanding of sonoporation and provides further insight into optimizing ADV for therapeutic applications and accelerates the translation of this approach to the clinic.

Micron-sized, monodisperse droplets with a water (W1)-in-perfluorocarbon-in-water (W2) morphology were produced using a microfluidic chip (Cat# 3200146, junction: 14 × 17 μm2, Dolomite, Royston, United Kingdom).18 The W1 phase consisted of Cascade Blue dextran (10 kDa, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Life Technologies), stabilized by a fluorinated surfactant. The W2 phase was 50 mg/ml Pluronic F68 (CAS# 9003‐11-6, Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS. PFP (CAS# 355‐42-0, Strem Chemicals, Newburyport, MA, USA), PFH (CAS# 355‐42-0, Strem Chemicals), or PFO (CAS# 307‐34-6, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used as the perfluorocarbon phase. The resulting diameters (Ø) and the corresponding coefficient of variation (CV) were as follows: PFP (Ø: 12.7 ± 0.4 μm, CV: 3.0%), PFH (Ø: 12.5 ± 0.4 μm, CV: 3.5%), and PFO (Ø: 12.7 ± 0.4 μm, CV: 3.4%). These larger diameter phase-shift droplets were studied due to their use in ARSs, which are implanted subcutaneously or intramuscularly for regenerative applications. Comparatively, smaller diameter droplets are typically used for intravascular administration or in applications that require extravasation.

To fabricate ARSs, fibrinogen solution was prepared by reconstituting bovine fibrinogen (Sigma-Aldrich) in FluoroBrite Dulbecco's Eagle's medium (DMEM, Life Technologies) followed by degassing in a vacuum chamber (at ∼6 kPa for 60 min, Isotemp vacuum oven, model 282A, Fisher Scientific, Dubuque, IA, USA). The final concentrations of fibrin, bovine lung aprotinin (Sigma-Aldrich), phase-shift droplets, and recombinant human thrombin (Recothrom, Baxter, Deerfield, IL, USA) were 10 mg/ml, 0.05 U/ml, 0.006% v/v (0.01% (v/v) for confocal imaging), and 2 U/ml, respectively. A fibrin density of 10 mg/ml was selected since it has been commonly used in prior in vitro and in vivo studies.39,40 For ultra-high-speed tracking, coated polystyrene microbeads (diameter: ∼3.2 μm, 0.06% (v/v), Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fremont, CA, USA) were embedded in ARSs (height: ∼1.5–2 mm). For confocal microscopy studies, ARSs contained 39 μg/ml Alexa Fluor 647-labeled fibrinogen (F35200, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) to facilitate visualization. Normal human dermal fibroblasts (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) were cultured in complete media consisting of DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Corning, Glendale, AZ, USA), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Fibroblasts were seeded at a density of 0.5 × 106 cells/ml in ARSs and subsequently cultured in a standard tissue culture incubator for four days. Propidium iodide (PI, 15 μM, Molecular Probes) and calcein AM (1 μM, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were added to media overlying the ARSs and then incubated for one hour before the experiments. The effect of ADV on membrane permeability was studied by measuring the mean fluorescence intensities of PI and calcein in cells adjacent to droplets before and up to 10 min after ultrasound using NIS-Elements software (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA).

To generate ADV, a calibrated, spherically focused transducer (2.5 MHz, H108, f-number = 0.83, radius of curvature = 50 mm, Sonic Concepts, Inc., Bothell, WA, USA) was confocally aligned with the microscope objective. The transducer was calibrated experimentally in free field using a fiber optic hydrophone (sensitivity: 16.6 mV/MPa). The transducer was driven by a single, sine-wave ultrasound burst (pulse duration: 6 μs, number of cycles: 15, peak rarefactional pressure (Pr): 6.5 MPa) generated by a function generator (33500B, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and amplified by a radio frequency amplifier (GA-2500A Ritec, Inc., Warwick, RI, USA). The selected pressure, which is close to the highest output of the transducer, was suprathreshold for all phase-shift droplets studied here.41 The acoustic parameters were chosen according to our prior publications, which are commonly used for therapeutic applications.39,40,42 An ultra-high-speed framing camera (SIM802 model, Specialized Imaging Ltd., Pitstone, UK) was paired with a customized upright microscope (Eclipse, Nikon LV100ND) equipped with a water-immersion objective at 100× (NA: 1.1, WD: 2.5 mm, Plan, Nikon) [Fig. 1(a)]. A high-intensity pulsed laser (400 W, 640 nm, Cavitar Ltd., Tampere, Finland) was used in a back illumination configuration to provide high intensity illumination. Particle displacement was quantified using an in-house developed MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) script. For confocal microscopy, the same transducer was confocally aligned to the optical focus of an inverted microscope (AX, Nikon) and driven at the same acoustic parameters [Fig. 1(b)]. The tight focus of the transducer (f-number: 0.8) as well as use of a single burst of ultrasound minimized formation of a complex standing wave field at the gel–coverslip interface in confocal microscopy experiments. The maximum region of interference due to a standing wave field was ∼1 mm from a free interface (i.e., air–water) using the same transducer.22,43–45 Therefore, in the current study, data were collected at mid-thickness of ARSs (∼1 mm above the coverslip). The temperature was maintained at 37 °C using a heater with thermostat (Cobalt aquatics, USA) and changing the overlying media every 20 min in high-speed and confocal microscopy studies, respectively.

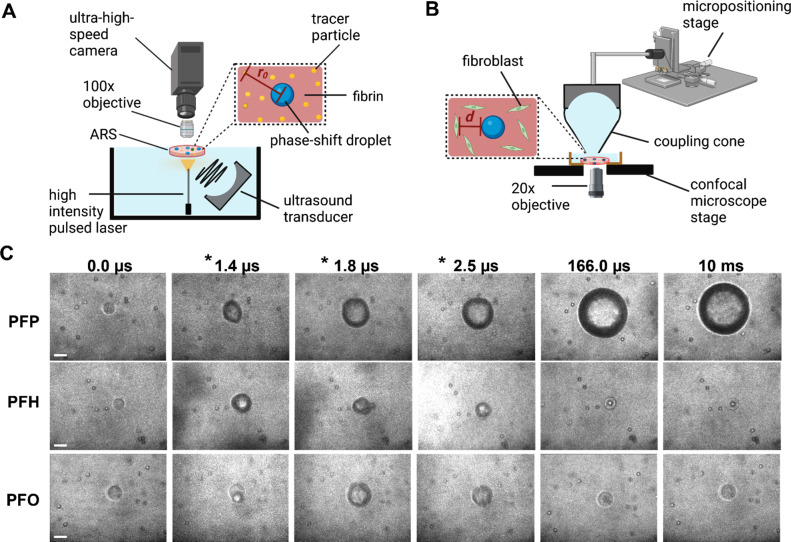

FIG. 1.

Ultra-high-speed and confocal microscopies were integrated with focused ultrasound to study the sonoporative effects of acoustic droplet vaporization (ADV) in acoustically responsive scaffolds (ARSs). Schematics show the experimental setups for (a) ultra-high-speed microscopy, where tracer particles were embedded in fibrin-based ARSs and (b) confocal microscopy, where ARSs contained fibroblasts. The initial distance of each tracer particle from a droplet center is denoted as r0. For confocal studies, the initial distance of each cell from a droplet is denoted as d. (c) High-speed images were recorded, at frame rates up to 10 × 106 frames per second to quantify the radial dynamics of ADV bubbles as well as ADV-induced displacement of tracer particles during and after ultrasound in ARSs containing perfluoropentane (PFP), perfluorohexane (PFH), and perfluorooctane (PFO) phase-shift droplets. The acoustic parameters were as follows: a single burst of 6 μs, 2.5 MHz, and 6.5 MPa. ARSs contained 10 mg/ml fibrin. Frames containing ultrasound are denoted with an asterisk. Scale bar: 15 μm.

Representative ultra-high-speed microscopy images demonstrated significantly different ADV dynamics for similar size phase-shift droplets of varying perfluorocarbon cores [Fig. 1(c)]. A single burst of ultrasound initiated ADV in the phase-shift droplets in ARSs. Consistent with our previous work,18 both PFP and PFH droplets formed stable bubbles after ultrasound was turned off, although the growth rate was significantly slower (up to an order of magnitude) for the latter. It should be noted that only PFP droplets were superheated (i.e., above their bulk boiling point) under the experimental conditions; therefore, once triggered, the ADV process is irreversible leading to stable bubble formation.44,45 Although the vapor pressure of PFH (∼46 kPa) is significantly lower than that for PFP (∼135 kPa) at the experimental ambient temperature (37 °C), stable bubble formation can be attributed to inward gas diffusion during ADV enhanced by the higher amplitude and long pulse durations used here (i.e., rectified diffusion). Contrastingly, PFO droplets recondensed. The significantly lower vapor pressure (∼1 kPa) as well as lower solubility and mass diffusivity of oxygen reduced the volume of non-condensed gas and, thus, the likelihood of survival of a bubble in a PFO droplet.41

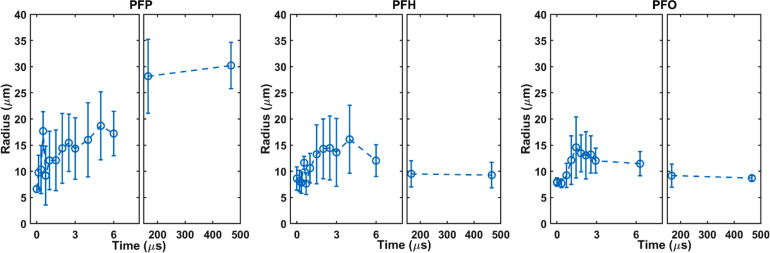

The maximum radial expansion/oscillation with respect to the initial radius of the droplet, expansion velocity during ultrasound, and the final bubble size after ultrasound were significantly higher for PFP droplets (Fig. 2). The maximum radii and corresponding expansion ratios (ʌmax) during ultrasound were 20.1 ± 4.2 μm (ʌmax: 3.6 ± 0.8), 17.0 ± 6.2 μm (ʌmax: 2.5 ± 0.5), and 15.0 ± 4.1 μm (ʌmax: 2.5 ± 0.4) for PFP, PFH, and PFO droplets in ARSs, respectively. ʌmax was significantly higher for PFP droplets compared to PFH (p-value = 0.005) and PFO droplets (p-value = 0.02). In applications where maintaining an upper limit on bubble size is critical, careful consideration should be given to the selection of the perfluorocarbon liquid and droplet size. ADV-generated bubbles in ARSs containing PFP droplets remained stable after ultrasound, settling to a resting size of 31.4 ± 2.0 μm (ʌmax: 4.8 ± 0.4) at 10 ms. However, ʌmax was close to 1 for PFH and PFO droplets at 10 ms after ultrasound. Similarly, the maximum expansion velocity during ultrasound was significantly higher for PFP droplets (15.7 ± 11.1 m/s) compared to PFH (5.7 ± 2.7 m/s) (p-value = 0.007) and PFO (6.4 ± 3.6 m/s) (p-value = 0.01) droplets. The maximum expansion velocity was not significantly different for PFH and PFO droplets (p-value: 0.9).

FIG. 2.

The radial expansion/oscillation was recorded for three perfluorocarbon phase-shift droplets during and after ultrasound using ultra-high-speed imaging: perfluoropentane (PFP) (n = 14), perfluorohexane (PFH) (n = 11), and perfluorooctane (PFO) (n = 10). Acoustic parameters were as follows: a single burst of 6 μs at 2.5 MHz (Pr: 6.5 MPa) in acoustically responsive scaffolds containing 10 mg/ml fibrin. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation.

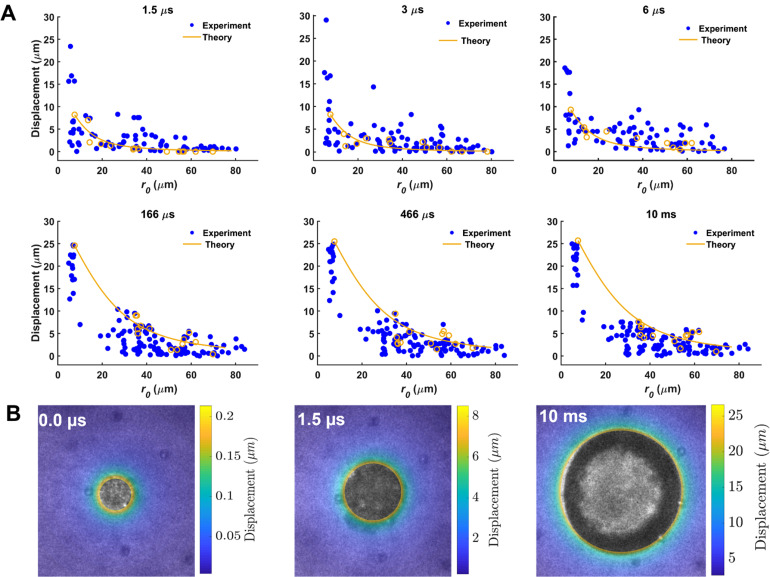

Ultra-fast tracking of particle displacement induced by ADV during and after ultrasound indicated a highly localized deformation field (Fig. 3). Displacement of tracer particles depended on the initial distance (r0) from the droplet center with a rapid and significant decrease in displacement as r0 increased. For tracer particles located at r0 < 10 μm, the maximum particle displacement was 14.0 ± 6.6 μm (radial strain ( ): 2.1 ± 1.3), 9.1 ± 4.5 μm ( : 0.9 ± 0.5), and 7.6 ± 2.0 μm ( : 0.9 ± 0.3) for PFP, PFH, and PFO droplets, during ultrasound, respectively (Figs. 3 and 4). Similarly, at r0 < 10 μm, the maximum displacement reached 23.7 ± 3.7 μm ( : 3.7 ± 0.8), 2.8 ± 0.9 μm ( : 0.1 ± 0.08), and 2.5 ± 0.9 μm ( : 0.07 ± 0.05) for PFP, PFH, and PFO droplets 10 ms after ultrasound, respectively. The displacement significantly decayed for particles further from the droplets. For example, for tracer particles at r0 = ∼25 μm from a PFP droplet, the average displacement was 2.0 ± 1.6 μm and 5.8 ± 1.5 μm, during and 10 ms after ultrasound, respectively. The quantified ADV-induced radial displacement and the resulting radial strain in a 3D in vitro model provide useful information with respect to high-rate, strain-induced sonoporation. Critical injury strain threshold varies for different cell types. For example, critical injury strain thresholds of ∼0.07 and ∼0.14 were reported for neuronal dendritic spines and filamentous actin, respectively.46

FIG. 3.

(a) Ultra-high-speed particle tracking was used to visualize and quantify particle displacement induced by acoustic droplet vaporization during and after ultrasound in acoustically responsive scaffolds containing 10 mg/ml fibrin and 0.006% (v/v) perfluoropentane phase-shift droplets (n = 15 droplets). Acoustic parameters were as follows: a single burst of 6 μs at 2.5 MHz (Pr: 6.5 MPa). Numerical predictions are only shown for one set of experimental data, shown in orange open circles, using Eq. (1). (b) Representative displacement maps were generated before (0 μs), during (1.5 μs), and after (10 ms) ultrasound for color-coded data in (a).

FIG. 4.

Ultra-high-speed particle tracking was used to visualize and quantify mechanical effects induced by acoustic droplet vaporization during and after ultrasound in acoustically responsive scaffolds containing 10 mg/ml fibrin and 0.006% (a) perfluorohexane and (b) perfluorooctane phase-shift droplets (n = 12–15 droplets).

Experimental data were further compared with theoretical predictions using the following equation:47

| (1) |

where the relationship in Eq. (1) arises from the specific problem of a spherically symmetric bubble of initial radius R0 changing to a new radial size R(t) at time (t) in an assumed near-incompressible material.47 Notably, this theoretical relationship depends solely on the measured bubble radii R0 and R(t). The referential radial coordinate in the surrounding material (r0) was measured from the center of the bubble where R0 < r0 < . The results of the theoretical prediction are in good agreement with experimental data, indicating a significant displacement of particles close to the induced bubble. For each time point in Fig. 3(a), the root mean square errors between experimental measurements and theoretical predictions were 0.67 (1.5 μs), 0.8 (3.0 μs), 0.9 (6 μs), 1.2 (166 μs), 2.2 (466 μs), and 1.5 (10.0 ms).

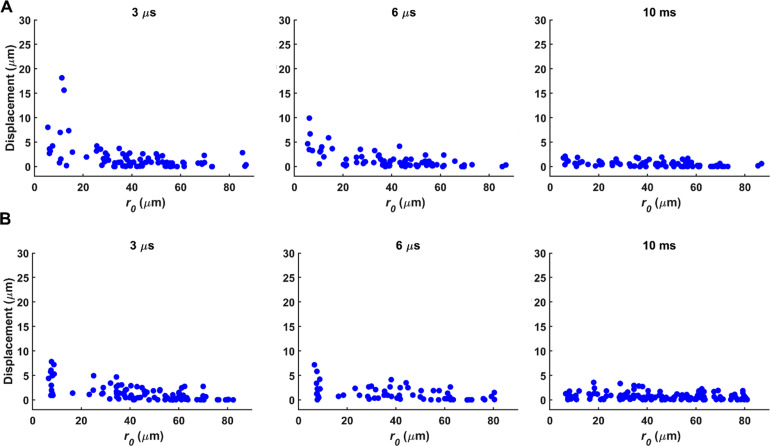

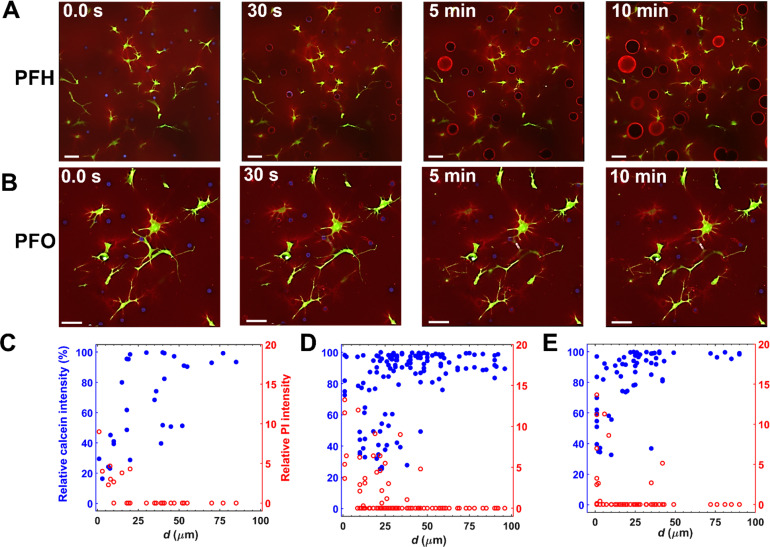

Representative real-time fluorescence images (Fig. S1) displayed a significant decrease in the calcein intensity and an increase in the uptake of PI induced via ADV of a PFH droplet at a droplet-to-cell distance (d) of ∼21 μm. As can be seen in Figs. 5(a), 5(b), and Fig. S2 (zoomed regions), both ADV-induced stable and transient bubble formation from PFH and PFO droplets, respectively, impacted cell membrane permeability, which strongly depended on d. Transient bubble formation in ARSs containing PFO droplets, after a single burst of ultrasound, was evident by the elevated fibrinogen intensity (Fig. S3) in the surrounding fibrin due to repetitive ADV-induced strain, a reduction in the payload intensity (14.5% ± 6.8%, n = 30), and a reduction in diameter (18.8% ± 11.7%, n = 30).

FIG. 5.

Real-time confocal microscopy was used to visualize and quantify the effects of acoustic droplet vaporization (ADV) on fibroblasts co-encapsulated in acoustically responsive scaffolds (ARSs). Representative confocal images (z-stack height: 46 μm) of ARSs containing (a) perfluorohexane (PFH) and (b) perfluorooctane (PFO) droplets are shown before and up to 10 min after ultrasound. For higher magnification confocal images of ARSs before and after ADV see Figs. S1 and S2. Fibrin, phase-shift droplets, and fibroblasts appear red, blue, and green due to inclusion of Alexa Fluor 647 fibrinogen, Cascade Blue dextran, and calcein, respectively. Scale bar: 50 μm. (c) Relative change in calcein and PI is plotted as a function of the droplet-to-cell distance [denoted as d as shown in Fig. 1(b)] for (c) PFP, (d) PFH, and (e) PFO droplets 10 min after ultrasound. Similar acoustic parameters were used.

Photobleaching decreased the maximum intensity by no more than 15% in our control studies (i.e., ARSs containing only fibroblasts) with sham ultrasound. Thus, a loss in the calcein intensity greater than 15% was attributed to ADV. Since nuclear staining was not performed in this study, in instances where multiple cells were present around a droplet, the closest distance was measured. We defined the critical threshold distance as the maximum distance from a droplet over which cells experienced either a decrease in the calcein intensity or an increase in the PI intensity. For calcein, the critical threshold distance was 22.5 ± 15.4, 21.0 ± 13.1, and 14.0 ± 10.5 μm (the average major axis length of fibroblasts: 56.5 ± 22.1 μm) for PFP [Fig. 5(c)], PFH [Fig. 5(d)], and PFO [Fig. 5(e)] droplets, respectively. The critical threshold distance was significantly larger for PFP and PFH compared to PFO droplets (p-values = 0.01). However, the critical threshold distance was not significantly different for PFP and PFH droplets. Threshold distances determined based on decreases in the calcein signal or increases in the PI signal were not significantly different (p-value = 0.08). Within the threshold distance, the percent PI positive cells were 40%, 29%, and 19% for PFP, PFH, and PFO droplets, respectively. Note that in some cells, a significant decrease in the calcein intensity was observed without any uptake of PI. In the context of sonoporation, increased permeability without loss of viability has been attributed to resealing of the induced pores.26,27 In the present study, two distinct patterns of signal intensity change were observed for calcein and PI within the critical threshold distance under similar ultrasound exposure. First, a pronounced decrease (increase) in the calcein (PI) intensity within 30 s of ADV; the intensities then remained relatively constant [Fig. S4(a)]. Second, a sharp decrease (increase) in the calcein (PI) signal within 30 s of ADV; the intensities then continued to decrease (increase) [Fig. S4(b)]. Further investigations are required to understand the underlying physics and correlate the time-dependent signal intensity change with the observed bubble dynamics. In this study, high-speed and confocal studies were conducted in two separate experiments. Integrating confocal and high-speed microscopy for real-time brightfield and fluorescence imaging can shed light on the intricate interplay between ADV bubble dynamics and the resultant cellular responses. Due to thermal instability and spontaneous vaporization, experimental data on PFP droplets were limited.

The measured critical threshold distance determined via confocal microscopy correlated with the maximum radial expansion and particle displacement in the ultra-high-speed microscopy studies. For example, the maximum radial expansion and critical threshold distance for ADV-induced sonoporation were 20.1 ± 4.2 μm and 22.5 ± 15.4 μm, respectively, for a PFP droplet. This indicates that a significant decrease in calcein and increase in PI occurred when d was smaller than the maximum radius of expansion of a phase-shift droplet. In prior studies, cell membranes were permeabilized by cavitation of ultrasound- or laser-induced bubbles when the ratio of d to the bubble diameter was ∼0.75.48,49 In our studies, ADV-induced cell membrane poration was observed when the ratio of d to initial droplet diameter (i.e., Ø) was 1.9 ± 1.2, 1.1 ± 0.7, and 1.1 ± 0.8 for PFP, PFH, and PFO droplets, respectively. The d/Ø ratio was significantly larger for PFP droplets compared to both PFH (p-value = 0.03) and PFO (p-value = 0.007) droplets. These findings suggest that ADV-induced sonoporation has a greater reach compared to conventional contrast microbubbles, likely due to the volumetric expansion caused by the phase-transition, which could be beneficial for drug delivery and therapeutic applications.

Due to the slower temporal resolution of confocal microscopy, the present study characterized the combined effect of ADV, subsequent bubble oscillation, and passive-diffusion driven growth of the generated bubble on cell membrane permeability. In our study, a high amplitude pressure, relevant to therapeutic applications, was used which could have generated large amplitudes of oscillations and inertial cavitation. To precisely differentiate the contribution of ADV (i.e., the volumetric expansion from the liquid droplet to a gas/vapor bubble) from the subsequent oscillation of the generated ADV-bubble in inducing sonoporation, high-speed fluorescence microscopy is required. While the studies here explored the effect of a single acoustic setting on the membrane level cellular responses, future studies should investigate different acoustic parameters, particularly the driving pressure, on overall cell morphology and cytoskeletal structure. The findings here provide useful information to optimize ADV for more tailored therapeutic applications. For example, insight gained from the critical threshold distance can be applied to the formulation of ARSs with droplet and cell densities that facilitate sonoporation. ADV-induced strain within an ARS can potentially alter cell behavior that is dependent on cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion.

See the supplementary material for details on real-time visualization of focused ultrasound and 3D confocal microscopy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grants [Nos. R01HL139656 (M.L.F.) and S10RR022425 (O.D.K.)] and startup funding from the Michigan Department of Mechanical Engineering (J.B.E.). The authors would like to thank Frank Kosel (Specialised Imaging Ltd.), Andrew Kosel (Specialised Imaging Ltd.), and Wai Chan (Specialised Imaging Ltd.) for helpful discussions on high-speed imaging, and Dr. William Weadock (Department of Radiology) for helping with 3D printing of CAD designs. We would like to dedicate this work in memoriam to Frank Kosel whose insight and experience were invaluable to this research.

AUTHOR DECLARATIONS

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Author Contributions

Mitra Aliabouzar: Conceptualization (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (lead); Methodology (equal); Resources (equal); Visualization (lead); Writing – original draft (lead). Bachir Ahmed Abeid: Formal analysis (equal); Methodology (equal); Writing – review & editing (supporting). Oliver D. Kripfgans: Resources (equal); Writing – review & editing (supporting). Brian Fowlkes: Writing – review & editing (supporting). Jonathan B. Estrada: Conceptualization (equal); Resources (equal); Supervision (equal); Writing – review & editing (supporting). Mario L. Fabiilli: Conceptualization (equal); Funding acquisition (lead); Methodology (equal); Resources (lead); Supervision (equal); Writing – original draft (supporting); Writing – review & editing (lead).

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Fowlkes J. B., Kripfgans O. D., and Carson P. L., “ Microbubbles for ultrasound diagnosis and therapy,” in 2004 2nd IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging: Nano to Macro, IEEE Cat. No. 04EX821 (IEEE, 2004), pp. 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kee A. L. Y. and Teo B. M., “ Biomedical applications of acoustically responsive phase shift nanodroplets: Current status and future directions,” Ultrason. Sonochem. 56, 37–45 (2019). 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Durham P. G. and Dayton P. A., “ Applications of sub-micron low-boiling point phase change contrast agents for ultrasound imaging and therapy,” Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 56, 101498 (2021). 10.1016/j.cocis.2021.101498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aliabouzar M. and Fabiilli M. L., “ Building blood vessels and beyond using bubbles,” Acoust. Today 18(2), 14–23 (2022). 10.1121/AT.2022.18.2.14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rapoport N. Y., Nam K.-H., Gao Z., and Kennedy A., “ Application of ultrasound for targeted nanotherapy of malignant tumors,” Acoust. Phys. 55, 594–601 (2009). 10.1134/S1063771009040162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kalayeh K., Fowlkes J. B., Claflin J., Fabiilli M. L., Schultz W. W., and Sack B. S., “ Ultrasound contrast stability for urinary bladder pressure measurement,” Ultrasound Med. Biol. 49(1), 136–151 (2023). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2022.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Escoffre J.-M. and Bouakaz A., Therapeutic Ultrasound ( Springer, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kalayeh K., Fowlkes J. B., Chen A., Yeras S., Fabiilli M. L., Claflin J., Daignault-Newton S., Schultz W. W., and Sack B. S., “ Pressure measurement in a bladder phantom using contrast-enhanced ultrasonography—A path to a catheter-free voiding cystometrogram,” Invest. Radiol. 58(3), 181–189 (2023). 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kripfgans O. D., Fowlkes J. B., Miller D. L., Eldevik O. P., and Carson P. L., “ Acoustic droplet vaporization for therapeutic and diagnostic applications,” Ultrasound Med. Biol. 26(7), 1177–1189 (2000). 10.1016/S0301-5629(00)00262-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shpak O., Kokhuis T. J., Luan Y., Lohse D., de Jong N., Fowlkes B., Fabiilli M., and Versluis M., “ Ultrafast dynamics of the acoustic vaporization of phase-change microdroplets,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 134(2), 1610–1621 (2013). 10.1121/1.4812882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li D. S., Kripfgans O. D., Fabiilli M. L., Brian Fowlkes J., and Bull J. L., “ Initial nucleation site formation due to acoustic droplet vaporization,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 104(6), 063703 (2014). 10.1063/1.4864110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kripfgans O. D., Fabiilli M. L., Carson P. L., and Fowlkes J., “ Acoustic vaporization micrometer-sized droplets,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 116(1), 272–281 (2004). 10.1121/1.1755236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shpak O., Stricker L., Versluis M., and Lohse D., “ The role of gas in ultrasonically driven vapor bubble growth,” Phys. Med. Biol. 58(8), 2523 (2013). 10.1088/0031-9155/58/8/2523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shpak O., Verweij M., Vos H. J., de Jong N., Lohse D., and Versluis M., “ Acoustic droplet vaporization is initiated by superharmonic focusing,” Appl. Phys. Sci. 111(5), 1697–1702 (2014). 10.1073/pnas.1312171111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aliabouzar M., Kripfgans O. D., Fowlkes J. B., and Fabiilli M. L., “ Bubble nucleation and dynamics in acoustic droplet vaporization: A review of concepts, applications, and new directions,” Z. Medizinische Phys. (2023). 10.1016/j.zemedi.2023.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Burgess M. T. and Porter T. M., “ On-demand cavitation from bursting droplets,” Acoust. Today 11(4), 35–41 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sheeran P. S. and Dayton P., “ Phase-change contrast agents for imaging and therapy,” Curr. Pharm. Des. 18(15), 2152–2165 (2012). 10.2174/138161212800099883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aliabouzar M., Kripfgans O. D., Estrada J. B., Fowlkes J. B., and Fabiilli M. L., “ Multi-time scale characterization of acoustic droplet vaporization and payload release of phase-shift emulsions using high-speed microscopy,” Ultrason. Sonochem. 88, 106090 (2022). 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burgess M. T., Aliabouzar M., Aguilar C., Fabiilli M. L., and Ketterling J. A., “ Slow-flow ultrasound localization microscopy using recondensation of perfluoropentane nanodroplets,” Ultrasound Med. Biol. 48(5), 743–759 (2022). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2021.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aliabouzar M., Davidson C. D., Wang W. Y., Kripfgans O. D., Franceschi R. T., Putnam A. J., Fowlkes J. B., Baker B. M., and Fabiilli M. L., “ Spatiotemporal control of micromechanics and microstructure in acoustically-responsive scaffolds using acoustic droplet vaporization,” Soft Matter 16(28), 6501–6513 (2020). 10.1039/D0SM00753F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lu X., Dong X., Natla S., Kripfgans O. D., Fowlkes J. B., Wang X., Franceschi R., Putnam A. J., and Fabiilli M. L., “ Parametric study of acoustic droplet vaporization thresholds and payload release from acoustically-responsive scaffolds,” Ultrasound Med. Bio. 45(9), 2471–84 (2019). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2019.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Matsunaga T. O., Sheeran P. S., Luois S., Streeter J. E., Mullin L. B., Banerjee B., and Dayton P. A., “Phase-change nanoparticles using highly volatile perfluorocarbons: Toward a platform for extravascular ultrasound imaging,” Theranostics 2(12), 1185 (2012). 10.7150/thno.4846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Evans D. R., Parsons D. F., and Craig V. S., “ Physical properties of phase-change emulsions,” Langmuir 22(23), 9538–9545 (2006). 10.1021/la062097u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Suzuki R., Takizawa T., Negishi Y., Utoguchi N., and Maruyama K., “ Effective gene delivery with novel liposomal bubbles and ultrasonic destruction technology,” Int. J. Pharm. 354(1–2), 49–55 (2008). 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mitragotri S., “ Healing sound: The use of ultrasound in drug delivery and other therapeutic applications,” Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 4(3), 255–260 (2005). 10.1038/nrd1662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang M., Zhang Y., Cai C., Tu J., Guo X., and Zhang D., “ Sonoporation-induced cell membrane permeabilization and cytoskeleton disassembly at varied acoustic and microbubble-cell parameters,” Sci. Rep. 8(1), 3885 (2018). 10.1038/s41598-018-22056-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Haugse R., Langer A., Murvold E. T., Costea D. E., Gjertsen B. T., Gilja O. H., Kotopoulis S., Ruiz de Garibay G., and McCormack E., “ Low-intensity sonoporation-induced intracellular signalling of pancreatic cancer cells, fibroblasts and endothelial cells,” Pharmaceutics 12(11), 1058 (2020). 10.3390/pharmaceutics12111058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hwang J. H., Tu J., Brayman A. A., Matula T. J., and Crum L. A., “ Correlation between inertial cavitation dose and endothelial cell damage in vivo,” Ultrasound Med. Biol. 32(10), 1611–1619 (2006). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Caskey C. F., Stieger S. M., Qin S., Dayton P. A., and Ferrara K. W., “ Direct observations of ultrasound microbubble contrast agent interaction with the microvessel wall,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 122(2), 1191–1200 (2007). 10.1121/1.2747204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maxwell A. D., Wang T.-Y., Cain C. A., Fowlkes J. B., Sapozhnikov O. A., Bailey M. R., and Xu Z., “ Cavitation clouds created by shock scattering from bubbles during histotripsy,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 130(4), 1888–1898 (2011). 10.1121/1.3625239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Qin P., Han T., Alfred C., and Xu L., “ Mechanistic understanding the bioeffects of ultrasound-driven microbubbles to enhance macromolecule delivery,” J. Controlled Release 272, 169–181 (2018). 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Seda R., Li D. S., Fowlkes J. B., and Bull J. L., “ Characterization of bioeffects on endothelial cells under acoustic droplet vaporization,” Ultrasound Med. Biol. 41(12), 3241–3252 (2015). 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2015.07.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fan C.-H., Lin Y.-T., Ho Y.-J., and Yeh C.-K., “ Spatial-temporal cellular bioeffects from acoustic droplet vaporization,” Theranostics 8(20), 5731 (2018). 10.7150/thno.28782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu W. W., Huang S. H., and Li P. C., “ Synchronized optical and acoustic droplet vaporization for effective sonoporation,” Pharmaceutics 11(6), 279 (2019). 10.3390/pharmaceutics11060279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Qin D., Zhang L., Chang N., Ni P., Zong Y., Bouakaz A., Wan M., and Feng Y., “ In situ observation of single cell response to acoustic droplet vaporization: Membrane deformation, permeabilization, and blebbing,” Ultrason. Sonochem. 47, 141–150 (2018). 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wu S. Y., Fix S. M., Arena C. B., Chen C. C., Zheng W., Olumolade O. O., Papadopoulou V., Novell A., Dayton P. A., and Konofagou E. E., “ Focused ultrasound-facilitated brain drug delivery using optimized nanodroplets: Vaporization efficiency dictates large molecular delivery,” Phys. Med. Biol. 63(3), 035002 (2018). 10.1088/1361-6560/aaa30d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kang S.-T., Lin Y.-C., and Yeh C.-K., “ Mechanical bioeffects of acoustic droplet vaporization in vessel-mimicking phantoms,” Ultrason. Sonochem. 21(5), 1866–1874 (2014). 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2014.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Duval K., Grover H., Han L.-H., Mou Y., Pegoraro A. F., Fredberg J., and Chen Z., “ Modeling physiological events in 2D vs. 3D cell culture,” Physiology 32(4), 266–277 (2017). 10.1152/physiol.00036.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 39. Jin H., Quesada C., Aliabouzar M., Kripfgans O. D., Franceschi R. T., Liu J., Putnam A. J., and Fabiilli M. L., “ Release of basic fibroblast growth factor from acoustically-responsive scaffolds promotes therapeutic angiogenesis in the hind limb ischemia model,” J. Controlled Release 338, 773–783 (2021). 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Huang L., Quesada C., Aliabouzar M., Fowlkes J. B., Franceschi R. T., Liu Z., Putnam A. J., and Fabiilli M. L., “ Spatially-directed angiogenesis using ultrasound-controlled release of basic fibroblast growth factor from acoustically-responsive scaffolds,” Acta Biomater. 129, 73–83 (2021). 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.04.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Aliabouzar M., Kripfgans O. D., Wang W. Y., Baker B. M., Brian Fowlkes J., and Fabiilli M. L., “ Stable and transient bubble formation in acoustically-responsive scaffolds by acoustic droplet vaporization: Theory and application in sequential release,” Ultrason. Sonochem. 72, 105430 (2021). 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Aliabouzar M., Quesada C., Chan Z. Q., Fowlkes J. B., Franceschi R. T., Putnam A. J., and Fabiilli M. L., “ Acoustic droplet vaporization for on-demand modulation of microporosity in smart hydrogels,” Acta Biomater. 164, 195–208 (2023). 10.1016/j.actbio.2023.04.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aliabouzar M., Jivani A., Lu X., Kripfgans O. D., Fowlkes J. B., and Fabiilli M. L., “ Standing wave-assisted acoustic droplet vaporization for single and dual payload release in acoustically-responsive scaffolds,” Ultrason. Sonochem. 66, 105109 (2020). 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sheeran P. S., Matsunaga T. O., and Dayton P. A., “ Phase change events of volatile liquid perfluorocarbon contrast agents produce unique acoustic signatures,” Phys. Med. Biol. 59(2), 379 (2014). 10.1088/0031-9155/59/2/379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Doinikov A. A., Sheeran P. S., Bouakaz A., and Dayton P. A., “ Vaporization dynamics of volatile perfluorocarbon droplets: A theoretical model and in vitro validation,” Med. Phys. 41(10), 102901 (2014). 10.1118/1.4894804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Estrada J. B., Cramer H. C. III, Scimone M. T., Buyukozturk S., and Franck C., “ Neural cell injury pathology due to high-rate mechanical loading,” Brain Multiphysics 2, 100034 (2021). 10.1016/j.brain.2021.100034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Estrada J. B., Barajas C., Henann D. L., Johnsen E., and Franck C., “ High strain-rate soft material characterization via inertial cavitation,” J. Mech. Phys. Solids 112, 291–317 (2018). 10.1016/j.jmps.2017.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Le Gac S., Zwaan E., van den Berg A., and Ohl C.-D., “ Sonoporation of suspension cells with a single cavitation bubble in a microfluidic confinement,” Lab Chip 7(12), 1666–1672 (2007). 10.1039/b712897p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhou Y., Yang K., Cui J., Ye J., and Deng C., “ Controlled permeation of cell membrane by single bubble acoustic cavitation,” J. Controlled Release 157(1), 103–111 (2012). 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.09.068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See the supplementary material for details on real-time visualization of focused ultrasound and 3D confocal microscopy.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.