Abstract

Previous research has mostly ignored that citizens could experience information overload from a single issue extensively covered in the news. Especially when it comes to issues upon which citizens decide directly in a referendum, overload and avoidance would be problematic from a democracy theory perspective. This study investigates overload and avoidance at the issue level based on a three-wave panel survey on a referendum in Switzerland and finds weak information overload at the aggregate level. However, citizens become increasingly overloaded during the period of extensive news coverage which leads to avoidance of news on the issue but not of interpersonal discussions.

Keywords: news overload, news avoidance, referendum news exposure

Today’s news media environment provides citizens with an abundance of political information (van Aelst et al., 2017). From a democracy theory perspective, citizens should be well informed about current political issues to make informed choices (Aalberg & Curran, 2012; Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996). This is particularly important during a referendum when citizens accept or reject a specific policy (Stucki et al., 2018) rather than vote on political representatives. Thus, citizens’ knowledge about the policy issue has direct effects on their voting decision. It is assumed that intensive information about the referendum has a positive impact on voters; high amounts of information lead to stable attitudes and competent vote choices (Dvořák, 2013; Hobolt, 2005; Leduc, 2002). In referendums, voters are often more volatile than during elections, and their voting choices are often influenced by short-term political factors and based less on party affiliation than during elections (Leduc, 2002; Marcinkowski & Donk, 2012). The news media plays a central role by covering the latest developments and presenting the arguments of different actors involved (de Vreese & Semetko, 2006; Schmitt-Beck, 2000). Thus, referendums can be accompanied by high-intensity campaigns with high amounts of media coverage (Kriesi, 2005).

Agenda-setting research assumes that media attention to issues generally guides public attention to these issues and that media coverage positively influences the perceived importance of an issue and the public’s interest in it (e.g., Matthes, 2008; McCombs, 2007). Vice versa, public attention to and interest in issues impact media attention to these issues (Brosius & Kepplinger, 1990). However, for some issues, such as a referendum, media coverage remains extensive for a prolonged period.

While news media coverage is key for an informed voting choice, the question arises as to whether the sheer amount of election or referendum news coverage also has negative effects on news users’ information behavior and opinion formation. The concepts of information overload and news overload deal with the negative effects of high amounts of information on individuals and news users, respectively. Information overload refers to “receiving too much information” (Eppler & Mengis, 2004, p. 326); it occurs if the amount of information exceeds the recipient’s cognitive capacities to process it, leading to negative feelings, such as distress (Eppler & Mengis, 2004; Jackson & Farzaneh, 2012). Correspondingly, news overload refers to feeling overwhelmed with the amount of news available (Goyanes, 2014; Ji et al., 2014). Several studies have shown that news overload causes news avoidance (A. M. Lee et al., 2019; Song et al., 2017). While there may be positive consequences of news avoidance such as increased mental health (de Bruin et al., 2021), news users who experience overload and, consequently, avoid news about the issue, learn less about politics (van Erkel & van Aelst, 2021).

Thus, the question arises as to whether the amount of news available helps or hinders citizens to become informed (Andersen, 2022). Previous research has not yet investigated news overload and avoidance at the level of single political issues in the news. Especially when it comes to direct political decision-making, such as in referendums, how citizens form their opinions about the issue in question is of utmost importance. Against this background, this study addresses the questions to what extent news users feel overloaded by information on a referendum issue which is covered extensively prior to voting day, and whether this leads to avoiding information on that issue.

The vast majority of studies analyzing the effects of news overload have relied on cross-sectional data (S. K. Lee et al., 2016, 2017; Song et al., 2017). However, these studies can only find correlational relationships between overload and news avoidance. In our study, we used a three-wave panel survey to model the effects of news overload on information avoidance within individuals, which allowed for identifying causal effects.

Information and News Overload

The concept of information overload is rooted in information and management sciences, where the effects of information overload on decision quality and performance are of significant interest (Eppler & Mengis, 2004; Hwang & Lin, 1999; Jackson & Farzaneh, 2012; Roetzel, 2018). Information overload occurs if the amount of information exceeds the individual’s cognitive capacities to process it (Eppler & Mengis, 2004; Hwang & Lin, 1999; Lang, 2000). It results in a state of feeling overwhelmed and distressed (Williamson & Eaker, 2012). First, the quantity of received information in a time period is a cause of information overload (Eppler & Mengis, 2004; Jackson & Farzaneh, 2012). Second, individual characteristics, such as general information processing capacity and motivation, are influential (Eppler & Mengis, 2004; Jackson & Farzaneh, 2012). Third, the characteristics of the information affect information overload. Information overload is facilitated by uncertainty, diversity, ambiguity, novelty, complexity, intensity, and the negative quality of the information (Eppler & Mengis, 2004; Jackson & Farzaneh, 2012; Roetzel, 2018; Schneider, 1987).

Regarding the changing news media environment, especially the proliferation of news outlets, communication research has begun to investigate the differential effects of the significant amounts of information distributed by news media to users. Early inquiries into information overload have already taken into account the increased amount of information being produced through computer-mediated communication (Hiltz & Turoff, 1985). The concept of news overload has gained importance over the past decades, as the Internet and social media have multiplied the amount of news everyone is confronted with on a daily basis (A. M. Lee et al., 2019; Park, 2019; Song et al., 2017). News overload is thus a special case of information overload and occurs because of cumulative news exposure (York, 2013). Data from the Reuters Institute Digital News Report from 2019 showed that 28% of the respondents perceived too much news and felt worn out by it (Newman et al., 2019). The Pew Research Center found that 66% were worn out by the amount of news in 2019; in 2016, 59% made the same claim (Gottfried, 2020). It is important to note here that scholarly literature deals with people’s perceptions of news overload and their feeling of being overloaded (e.g., S. K. Lee et al., 2016). Such perceptions can be different from actual overload and can possibly also occur when there is no particularly extensive media coverage.

Extant research has identified several causes for people experiencing news overload. The intensity of news exposure and the amount of news consumed can lead to news overload. York (2013) and Chen and Masullo Chen (2020) showed that increased levels of news exposure are related to higher levels of overload. While some studies found that the use of online news and social media (Chen & Masullo Chen, 2020; S. K. Lee et al., 2016) and specific news formats, for instance, push notifications (Schmitt et al., 2018), positively predict news overload, previous studies yielded different results on the role of traditional news media use. Chen and Masullo Chen (2020) showed that consumption of TV news most strongly correlated with news overload while in Holton and Chyi’s (2012) study TV news consumption was negatively related to news overload. York (2013) found that news enjoyment moderated the effects of news exposure on news overload. Higher levels of news enjoyment reduced the likelihood of news overload in cases of high amounts of news exposure.

Furthermore, individual traits such as age, gender, and income are related to perceptions of information overload (Holton & Chyi, 2012; Ji et al., 2014; Schmitt et al., 2018). Although the influence of individual factors differs among countries, people who are younger, female, less affluent, and less educated generally experience higher levels of news overload (Goyanes, 2014; Ji et al., 2014; S. K. Lee et al., 2016; Schmitt et al., 2018). In addition, people with lower information-seeking self-efficacy (Schmitt et al., 2018) and news efficacy (Park, 2019) are more likely to experience news overload. Also, the topic of news can influence perceptions of news overload, with political news contributing strongest to news overload (A. M. Lee et al., 2019).

The majority of studies on news overload have focused on overload from news in general (Chen & Masullo Chen, 2020; Holton & Chyi, 2012; Song et al., 2017; York, 2013). However, some studies have found and various journalists have noted that overload and fatigue from the amount of news on single issues can emerge in certain instances, such as the presidential election campaign in the United States in 2016 (Gottfried, 2016), the COVID-19 coverage (Bedingfield, 2020; Groot Kormelink & Klein Gunnewiek, 2022), and Brexit (Gurr & Metag, 2022; Newman et al., 2019). Knowledge is lacking on whether news overload at the level of a single issue intensively covered over a prolonged period can emerge. We thus asked the following research questions:

Research question 1 (RQ1): To what extent do news media users feel overloaded by news on a single issue?

Research question 2 (RQ2): How does overload from a single news issue emerge over time?

Avoidance as a Consequence of News Overload

Studies on information overload point to consequences of information overload for the individual, namely for their productivity and decision-making abilities (Eppler & Mengis, 2004; Hwang & Lin, 1999). The negative cognitive and affective psychological state of information overload can lead to behavioral countermeasures (Eppler & Mengis, 2004; Schmitt et al., 2018). Some studies on news overload specifically have considered news avoidance as a consequence (S. K. Lee et al., 2017; A. M. Lee et al., 2019; Park, 2019; Song et al., 2017).

Communication research applies different understandings of news avoidance (Gurr & Metag, 2021; Skovsgaard & Andersen, 2020). Avoidance is often conceptualized as limited exposure to news or not selecting news because of a preference for other media content (Karlsen et al., 2020; Ksiazek et al., 2010; Strömbäck, 2017; Trilling & Schoenbach, 2013). This type of news avoidance is unintentional. Studies found a decline in news use in the past decades and observed increasing gaps between news seekers and news avoiders (Aalberg et al., 2013; Shehata et al., 2015; Strömbäck et al., 2013). While some citizens increasingly use news, others increasingly avoid it altogether.

While unintentional news avoidance is not an active decision, intentional news avoidance results from a conscious choice (Skovsgaard & Andersen, 2020). In line with this, information science has described active or intentional information avoidance as an individual’s purposeful decision to stay away from available information (Howell & Shepperd, 2016). According to the Reuters Institute Digital News Report, 32% of the Internet users actively avoided the news at least sometimes in 2019, pointing to an increase since 2017, when 29% said that they had done so (Newman et al., 2019). Disinterest in politics and low levels of news self-efficacy (Edgerly, 2021) are causes of news avoidance.

Previous cross-sectional findings on news overload and avoidance suggested that news overload leads to news avoidance. Park (2019) and S. K. Lee et al. (2016) found that news overload is positively associated with the intention to avoid news. The findings by A. M. Lee et al. (2019) revealed selective scanning as a strategy related to news overload. Selective scanning refers to users selectively choosing information while ignoring information that does not fit their preferences (A. M. Lee et al., 2019). Recently, Groot Kormelink and Klein Gunnewiek (2022) found that news overload from COVID-19 leads young people to withdraw from news about it and de Bruin et al. (2021) found similar evidence for the Dutch population in general. In addition, factors mediating the relationship between news overload and news avoidance have been examined. Park (2019) found that news overload leads to decreased news efficacy, which in turn increases news avoidance on social media. Since extant research shows that feeling overloaded by news in general leads to news avoidance, we assumed that feeling overloaded by news on a specific issue in the news leads to avoiding news on that specific issue. Thus, we proposed the following:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Higher levels of perceived information overload from news on the issue lead to higher levels of avoidance of news on that issue.

Within news overload research, it has not yet been investigated whether news overload can also lead to avoiding interpersonal communication about news. Interpersonal discussions are social situations that involve other individuals and social norms (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005). Avoiding interpersonal discussions demands greater effort and potentially entails more unpleasant social consequences than avoidance of media content. Nonetheless, research has identified several causes of avoiding interpersonal discussions: dodging dissonance or conflict (Eveland et al., 2011) and anxiety and uncertainty (Duronto et al., 2005). When it comes to political news, individuals avoid talking about public issues because of a lack of interest or knowledge (Wyant et al., 2020). However, research has not yet investigated whether news overload leads to the avoidance of news in interpersonal discussions. Thus, it is also unclear whether feeling overloaded by news on a single issue leads to avoidance of discussions about it. However, this would be problematic because interpersonal discussions are an important source of news and information about politics (Bennet et al., 2000; Boomgaarden, 2014), also during a referendum (de Vreese, 2007). This uncertainty led to our third research question (RQ):

Research question 3 (RQ3): Does issue-specific news overload perceptions lead to avoidance of interpersonal discussions about that issue?

We investigated how feeling overloaded from extensive news coverage of a specific political issue leads to avoidance of information on that issue. More precisely, we focused on a referendum issue, where informed citizens are particularly important from a normative perspective.

Method

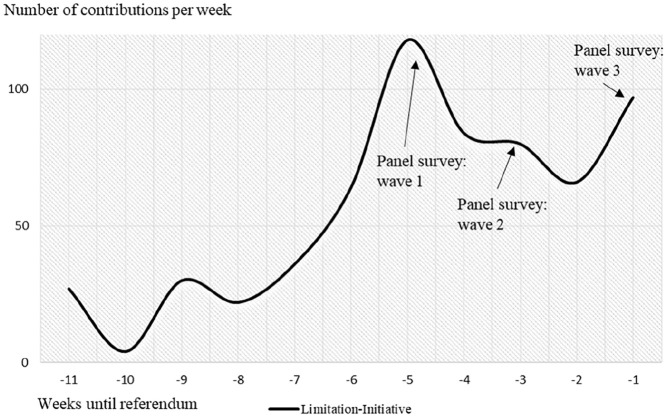

This study analyzed information overload and avoidance for the referendum “For moderate immigration (Limitation Initiative)” put to the vote on September 27, 2020, in Switzerland. The initiative aims to end the free movement of persons with the European Union (EU) as specifically provided for in the bilateral agreements between Switzerland and the EU. It was launched by the right-wing Swiss People’s Party (SVP) and the “Action for an independent and neutral Switzerland” (AUNS). The limitation initiative received the most media attention on all issues put to the vote on September 27, 2020, in the 12 weeks before the polling day (Udris, 2020a) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of media contributions per week before the referendum.

Note. The figure shows the number of media contributions on the limitation initiative per week. The starting point is just under 12 weeks before the voting date, and the end point is one week before the voting date (n= 628 contributions). The media sample consists of 14 websites (online appearances) from newspapers, six Sunday newspapers or magazines (print), and five TV news series from German-speaking Switzerland and Suisse Romande, based on data from Udris (2020a).

Since the limitation initiative is an important national issue for Switzerland and has received high amounts of media attention, it is a useful issue to study in terms of potential news overload and avoidance on an issue level. A representative three-wave online panel survey was conducted by a professional market and research institute during the five weeks prior to voting day, which is normally a period of extensive news coverage of an issue.

Quota sampling was applied with respect to age and gender. Wave 1 (n = 1,300, 50% female, Mage = 48, SD = 15.60, 49% higher education) took place from August 20–31, 2020; Wave 2 (n = 973, 48% female, Mage = 49, SD = 15.88, 49% higher education) from September 3–14, 2020; and Wave 3 (n = 783, 46% female, Mage = 49, SD = 15.91, 50% higher education) from September 17–28, 2020.

Measures

Previous studies on news overload and avoidance have applied different measures of avoidance, that is, the intention to avoid news (S. K. Lee et al., 2016, 2017; Park, 2019; Song et al., 2017), selective scanning (A. M. Lee et al., 2019), and selective exposure to particular news outlets (S. K. Lee et al., 2016, 2017). However, these measures do not align with the understanding of intentional news avoidance as an intentional behavior (see Skovsgaard & Andersen, 2020).

Research on media avoidance in other contexts has offered more precise measures of avoidance behavior. First, avoidance can occur during the media selection process, such as ignoring and skipping unwanted content. Findings on advertising avoidance point to avoidance strategies such as ignoring the ads, turning the page, and discarding content (Kim & Sang, 2017; Speck & Elliott, 1997). Second, avoidance occurs during exposure to a selected program or report. There is the possibility that users see a media report and start reading or watching it intentionally or incidentally (Oeldorf-Hirsch, 2018), but then take countermeasures, such as interrupting or terminating the exposure situation, reducing their attention, or doing something else (Schramm & Wirth, 2007, 2008).

We oriented our operationalization of issue-specific news avoidance toward Toff and Kalogeropoulos’s (2020) measure of news avoidance, namely, how frequently respondents were “actively trying to avoid news these days.” We chose five items on avoidance strategies during selection and exposure concerning other media content to measure avoidance more comprehensively with several items. We adapted the items to a single issue. We asked respondents to indicate how often they did the following during the past week. Response alternatives ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (very often): “Concerning an article or report, I . . .”: “did not even read it or look at it, when I noticed it was the limitation initiative issue”; “ignored it and instead I read or looked at something else”; “stopped reading it or looking at it before it was finished”; “kept following it, but I was inwardly disconnected,” and “kept following it while doing something else” (Wave 1: M = 2.32, SD = .90, and α = .83; Wave 2: M = 2.41, SD = .95, and α = .83; Wave 3: M = 2.47, SD = 1.00, and α = .85). For internal consistency measures, see Table 5 in the Supplemental Appendix.

Interpersonal avoidance was measured by one item (Wave 1: M = 2.03 and SD = 1.18; Wave 2: M = 2.03 and SD = 1.20; Wave 3: M = 2.08 and SD = 1.23): “I avoided discussing the issue with others.”

Information overload was measured by four items on a five-point scale from 1 (I totally disagree) to 5 (I totally agree): “I currently feel overloaded by the amount of news available on this issue,” “I receive more information on this issue than I can actually process,” “I am confronted with too much information on this issue,” and “I feel overloaded from the amount of news on this issue,” (Wave 1: M = 2.04, SD = .85, and α = .83; Wave 2: M = 2.19, SD =.91, and α = .86; Wave 3: M = 2.23, SD =.96, and α =.88). These items were oriented toward the news and information overload scales by Song et al. (2017), Williamson and Eaker (2012), and A. M. Lee et al. (2019).

To compare the effects of information overload on avoidance with the effect of alternative predictors of avoiding information on an issue, we included issue-specific control variables in the analysis. 1 Issue importance was measured by two items taken from Matthes (2013) on a five-point scale from 1 (I totally disagree) to 5 (I totally agree) (Wave 1: M = 4.20, SD =.91, and r = .60; Wave 2: M = 4.20, SD =.84, and r = .51; Wave 3: M = 4.19, SD =.88, and r = .64): “I personally think that this issue is important” and “This issue is important to Switzerland.” Interest in the issue was measured by one item (Wave 1: M = 3.72 and SD = 1.16; Wave 2: M = 3.64 and SD = 1.16; Wave 3: M = 3.66 and SD = 1.14) on a scale from 1 (not interested at all) to 5 (very interested): “How interested are you in the limitation initiative issue?” Self-perceived knowledge about the issue was measured by two items on a five-point scale from 1 (I totally disagree) to 5 (I totally agree) (Wave 1: M = 3.52, SD = 1.09, and r = .77; Wave 2: M = 3.67, SD = 1.02, and r = .74; Wave 3: M = 3.85, SD = .92, and r = .72): “I know the main arguments of the various parties involved in this issue” and “I know the main facts about this issue” (Geiss, 2015). A negative attitude toward the issue was measured by four items (Wave 1: M = 3.61, SD = 1.18, and α = .87; Wave 2: M = 3.57, SD = 1.17, and α = .86; Wave 3: M = 3.61, SD = 1.78, and α = .88): “If the free movement of people were to cease to exist, the Swiss would finally be able to decide for themselves again who comes to Switzerland. (recoded),” “Limited immigration would enable Swiss children to have a better education (recoded),” “The elimination of the free movement of persons would have negative effects on the Swiss economy,” and “The adoption of the limitation initiative would jeopardize good relations with the EU.” Response alternatives ranged from 1 (I totally disagree) to 5 (I totally agree).

Finally, we included general predictors of news exposure as control variables, which could influence exposure to and avoidance of news about a specific issue. The perceived duty to stay informed was measured by three items during Wave 2 (M = 3.39, SD = .50, and α = .69): “It is important to be informed about news and current events,” “We all have a duty to keep ourselves informed about news and current events,” and “So many other people follow the news and keep informed about it that it doesn’t matter much whether I do or not (recoded),” which were taken from Poindexter and McCombs (2001). Response alternatives ranged from 1 (I totally disagree) to 5 (I totally agree). News enjoyment was measured during Wave 3 by one item: “Keeping up with the news is not my idea of fun (recoded)” on a scale from 1 (I totally disagree) to 5 (I totally agree) (Wave 3: M = 2.91 and SD = 1.26). Political interest was measured by the question of how interested respondents were in information about what was going on in politics and public affairs during Wave 1 on a five-point scale from 1 (not interested at all) to 5 (very interested) (Wave 1: M = 3.48 and SD = 1.03) (for descriptive statistics and overtime changes per wave, see Table 3 in the Supplemental Appendix). In addition, age, gender, and education were included.

Data Analysis

A balanced (i.e., complete) sample of respondents who participated in all panel waves (n = 723; Mage = 49.49, 46% female, 52% tertiary education) was used for the analyses, while dropouts were excluded. This sample differed only slightly from the original sample. To avoid a further decrease in the number of observations in addition to the panel dropout, we conducted a within-mean imputation at the wave level. The available variables of a scale were used to replace every missing value with the individual mean of the available variables from the same scale in the same wave (Graham, 2012). The remaining missing values were replaced by the sample means. 2

To answer RQ1, descriptive statistics were computed, and for RQ2, dependent t tests were run at the aggregate level to compare the values for issue-specific news overload in the panel samples for Wave 1, Wave 2, and Wave 3.

H1 and RQ3 presumed causal effects of issue-specific information overload on issue-specific avoidance within an individual. Since we relied on hierarchical data—measurement occasions nested within individuals (Snijders & Bosker, 2012)—we could separate the variance within individuals over time from the variance among individuals in a multilevel model. We thus considered the panel data as hierarchical data (Level 1 = measurement occasions; Level 2 = individuals). This results in within-person independent variables, which indicate change within the same person in the measurement occasions, and between-person independent variables, which indicate variance between individuals in the sample. In the first step, we ran an empty model containing only random intercepts by an individual for both dependent variables to calculate the intra-class correlation (ICC). The ICC indicates the variance accounted for by the higher level (Level 2) (Snijders & Bosker, 2012), in this case the individual. The ICC was .54 for the avoidance of media information and .35 for interpersonal avoidance. Thus, 54% of the variance in avoidance of media information was accounted for by the differences among individuals. Forty-six percent of the variance in avoidance of media information was due to the variation among the measurement occasions. Thirty-five percent of the variance in interpersonal avoidance was accounted for by differences among the individuals. Since we wanted to test not only the effects from variables at Level 1, for example, information overload, but also the effects of Level 2 variables, for example, political interest, we opted for a random coefficient model (Snijders & Bosker, 2012). The effects of time-invariant Level 2 predictors cannot be considered in models based on within-variation only, such as fixed effects models (Allison, 2009; Wooldridge, 2010). Thus, in the second step, we built a random intercept model with different within- and between-group regressions (Snijders & Bosker, 2012) and included the explanatory variables at the measurement and individual levels (Hox, 2010). 3 Within-individual relations can be different from between-individual relations (Snijders & Bosker, 2012). The model thus included both fixed and random effects; we decomposed the variables’ variations into within- and between-variation. This allows testing the effects of time-invariant Level 2 predictors and of the time-varying Level 1 predictors, considering the within and between effects of the latter separately. 4 The within-group coefficient indicated the independent variable’s effect within the group, in this case, the individual. The between-group coefficient showed the effect of the group mean of the independent variable on the group mean of the dependent variable. For our hypotheses, we focused on the within-group coefficients, testing whether increases in information overload within an individual lead to higher levels of avoidance of media information about the issue and of interpersonal conversations about the issue. The between effects allowed us to compare the within effects of information overload with the alternative predictors.

Results

RQ1 asked to what extent the population feels overloaded by news on a single issue in the news. The descriptive results showed that the Swiss population was, on average, not overloaded by news about the limitation-initiative issue (Mwave1 = 2.04, Mwave2 = 2.19, and Mwave3 = 2.23). However, news overload from the issue increased over the five weeks prior to voting day (RQ2). There was a significant increase in the information overload during Wave 1 (M = 2.04 and SD = .85) compared with Wave 2 (M = 2.19 and SD = .92), t(616) = −5.05, p < .001. There was no further significant increase in information overload during Wave 2 (M = 2.19 and SD = .92) compared with Wave 3 (M = 2.24 and SD = .95), t(680) = −1.62, p = .053.

H1 presumed that information overload from the issue leads to avoiding media information about that issue. The results from the random effects within-between model (Table 1) showed that an increase in information overload within an individual led to an increase in the avoidance of media information about the issue within the same individual (within effect). Issue-specific information overload had a significant positive effect on issue-specific media avoidance, which supported H1. Individuals with higher levels of information overload avoided media information on the issue more frequently than individuals with lower levels of information overload (between effect). The between effect of information overload was stronger than the within effect. In addition, a decrease in interest in the issue within one individual led to an increase in avoidance of media information within that individual (within effect). However, the within effect from information overload was stronger than from the other issue predispositions. Individuals with lower levels of interest in the issue and lower levels of news enjoyment avoided media information on the issue more frequently (between effects). The model could explain 69% of the variance of avoidance of media information on the referendum issue.

Table 1.

Random Effects Within-Between Regression Model Predicting Avoidance of Media Information.

| Independent variable | b | SE |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.472*** | .246 |

| Information overload within | .204*** | .028 |

| Information overload between | .478*** | .037 |

| Interest within | −.106*** | .026 |

| Interest between | −.116** | .040 |

| Importance within | −.055 | .032 |

| Importance between | −.026 | .047 |

| Negative attitude within | −.030 | .036 |

| Negative attitude between | −.001 | .024 |

| Self-perceived knowledge within | −.091*** | .024 |

| Self-perceived knowledge between | −.062 | .032 |

| News enjoyment | −.101*** | .021 |

| Social norm | −.031 | .032 |

| Political interest | .013 | .032 |

| Age | .000 | .002 |

| Gender (female = 1) | .032 | .051 |

| Education (higher = 1) | .080 | .042 |

| N (observations) | 2,169 | |

| n (individuals) | 723 |

p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

RQ3 tested the effects of issue-specific information overload on the avoidance of interpersonal discussions about the issue in question. The results (Table 2) showed that information overload did not significantly predict avoidance of interpersonal discussions on the issue (within effect). However, individuals with higher levels of information overload from the issue avoided conversations about the issue more frequently than individuals with lower levels of information overload (between effect). Also, none of the other issue predispositions exerted a significant within effect. Individuals with lower levels of attributed importance to the issue, lower levels of political interest, and the perceived duty to keep informed avoided conversations about the issue more frequently (between effects). Fifty-two percent of the variance in interpersonal avoidance of the issue was explained by the model.

Table 2.

Random Effects Within-Between Regression Model Predicting Interpersonal Avoidance.

| Independent variable | b | SE |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.980*** | .307 |

| Information overload within | .045 | .041 |

| Information overload between | .448*** | .045 |

| Interest within | −.029 | .039 |

| Interest between | .015 | .048 |

| Importance within | −.085 | .047 |

| Importance between | −.114* | .058 |

| Negative attitude within | .047 | .052 |

| Negative attitude between | .008 | .029 |

| Self-perceived knowledge within | .018 | .035 |

| Self-perceived knowledge between | .063 | .039 |

| News enjoyment | −.008 | .026 |

| Social norm | −.101* | .045 |

| Political interest | −.098* | .039 |

| Age | .000 | .002 |

| Gender (female = 1) | .018 | .062 |

| Education (higher = 1) | .067 | .051 |

| N (observations) | 2,169 | |

| n (individuals) | 723 |

p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Discussion

Over the past few decades, news use has declined, and news avoiders have become increasingly more common (Aalberg et al., 2013; Newman et al., 2019; Strömbäck et al., 2013). Feeling overwhelmed by the amount of news these days—news overload—is discussed as an explanation for news avoidance (Skovsgaard & Andersen, 2020; Villi et al., 2022). While previous studies have addressed the idea that news users become overloaded by news and, consequently, avoid news altogether (A. M. Lee et al., 2019; Song et al., 2017), they have so far largely ignored whether news users experience overload from news about a single issue and avoid information about that issue (a an exception see de Bruin et al., 2021). This study investigated to what extent news users experience overload from news about a referendum issue in Switzerland and how this leads to the avoidance of information about that issue.

First, the findings showed that the Swiss population was, on average, not or only partly overloaded from information about the referendum issue. However, information overload increased significantly during the sixth and fifth weeks prior to voting day, when the issue’s news coverage increased sharply and reached its peak (Udris, 2020a). This period resembles the phases of growth of coverage and boom in the issue attention cycle (Waldherr, 2014). Although the average overload perception was not that high, this observation suggested that news users felt more overloaded by the amount of information about the issue the more extensive the news coverage became closer to voting day.

Second, the results from multilevel regressions based on three-wave panel data revealed that increasingly perceived news overload from the issue led to increasing avoidance of news about the issue. Issue-specific information overload was the strongest within-person predictor of avoidance of news about the issue. This supports the assumption that, first, news overload, and, second, the effects of news overload on news avoidance also occur at an issue level. Thus, the question of what amount of news available in today’s media environment helps citizens to become informed (Andersen, 2022) is also relevant at the level of single issues in the news. When considering the between effects, this study showed that even if information overload is not that high on average in the population, citizens who feel more overloaded than others are more prone to avoidance of information on the issue, which makes this correlation all the more relevant. The findings align with previous cross-sectional findings on the effects of general news overload on news avoidance. What is more, they add to previous cross-sectional findings by demonstrating a causal effect of overload on avoidance within individuals, based on longitudinal data.

In high-choice media environments, users can easily be selective; personal preferences are the central driver of media selection (Prior, 2007). According to this study, when overloaded with news about a single issue, news users avoid news about it. They potentially turn to other issues in the news or to other media content more generally, such as entertainment. Issue-specific news overload thus contributes to selective news exposure.

Third, this study found that when individuals’ overload from the issue increases, they do not increasingly avoid conversations with others about the issue. This suggests that avoidance because of overload perceptions is reserved for information provided by the news media. In fact, individuals might encounter the issue less in conversations than in the news. In addition, they are not confronted with high amounts of written or visual information in interpersonal conversations. Thus, information overload might result less from interpersonal conversations and trigger the avoidance of conversations less strongly than in news exposure situations. Furthermore, overloaded individuals could possibly benefit from interpersonal conversations to become informed about the issue (Bandura, 2001) as an alternative to news and, therefore, not avoid them despite information overload.

Especially when it comes to direct democracy, citizens should be well informed about different positions and current events regarding the policy in question (Stucki et al., 2018). The results from this study indicated that high amounts of referendum campaign coverage did not only have positive effects, as assumed by previous research (Dvořák, 2013; Hobolt, 2005; Leduc, 2002), but also detrimental effects on citizens. Even though the amount of coverage on this issue was high, studies on media coverage on other referendum issues show that other issues are covered even more, but many are also covered less (e.g., Udris, 2020b). This demonstrates that journalists have to navigate between their duty to inform and citizens’ potential overload perceptions.

Thus, both the characteristics of campaign coverage, such as strategic framing (Elenbaas & de Vreese, 2008; Schuck et al., 2013; Shehata, 2014) and the amount of news coverage, can affect citizens’ perceptions and behavior regarding the issue not only positively but also negatively. However, while from a normative democratic perspective news avoidance is conceptualized as negative, there is also scholarly debate on potential positive consequences of news avoidance such as increased mental well-being (de Bruin et al., 2021). News avoidance can thus serve as a coping strategy (Goyanes et al., 2021).

Interpersonal discussions are another relevant source of political information (Eveland, 2004; Scheufele, 2000). Since information overload from the referendum issue did not lead individuals to avoid conversations about it, they could still have become informed by others during conversations. Further research could investigate the interplay between the avoidance of news about an issue and the reception of information on that issue through interpersonal discussions.

It is important to note that we—like most of the scholarly literature on news and information overload—investigated perceived overload. However, it is an open question to what degree such perceived overload is also actual overload, that is, an actual overexertion of processing capacities, or whether perceived overload rather serves as self-rationalization for people’s little interest in an issue or their selective exposure to and motivated reasoning of information on this issue. It is possible that people are not actually overloaded by the amount of information but use it as an excuse for not wanting to deal with information that do not fit their ideological stance.

Limitations and Outlook

The findings from this study are limited primarily because issue-specific information overload and avoidance were investigated for only one issue. Future research should study both the emergence of issue-specific information overload over time and its effects on different avoidance forms for issues that differ from the referendum issue to increase the findings’ generalizability. Questions have arisen as to whether information overload and its effects on avoidance are weaker or stronger for international issues or more obtrusive issues than the referendum issue in this study. In addition, potential contextual effects should be considered. News avoidance depends on country-specific factors, such as levels of press freedom and political stability (Toff & Kalogeropoulos, 2020; Villi et al., 2022). Thus, the effects of information overload on avoidance also likely differ between information environments.

Our measurement of interpersonal avoidance is a methodological limitation. Several forms of interpersonal avoidance, such as changing the topic or terminating conversations, should be considered in future studies. Also, a linkage analysis of media content and survey data could have reduced the problem of self-assessment.

A three-wave panel survey is a better approach to information overload that emerges as a result of cumulative news exposure than cross-sectional or two-wave panel surveys, which allow neither for tracking change nor for calculating causal effects (Johnson, 2005). More measurements, however, could better determine the development of information overload over time and detect potential thresholds of information overload (Jackson & Farzaneh, 2012).

Since individuals who feel overloaded are more prone to avoid information on an issue, it would be important to tease out further what makes people more likely to feel overloaded. Since studies have mostly looked at news consumption as well as traits such as age, gender, and income and their influence on general news overload (Chen & Masullo Chen, 2020; Schmitt et al., 2018; York, 2013), one could assume that variables which served as control variables for effects on avoidance could be predictors of issue-specific information overload. The correlation matrix in the Supplemental Appendix (Table 6) shows that news enjoyment, issue interest, political interest, and education are negatively while age, issue importance, negative attitudes toward the issue, issue knowledge, and social norms are positively correlated with information overload. Which of these variables, however, exactly predict overload needs to be studied. One could ask, for example, whether perceived overload is a result of having adequate knowledge, for example, received through information seeking (Li & Zheng, 2022), or whether it is a cause for insufficient knowledge. Also, psychological research on the optimal level of complexity of a stimulus to avoid boredom or feelings of overload (e.g., Silvia, 2008) suggests that the perceived complexity of a news item could predict overload perceptions. While the focus of this study was on the influence of issue-specific overload on issue-specific avoidance, future research should analyze predictors of overload on an issue level further.

The findings from this study call for research on whether issue-specific overload and avoidance lead to general news overload and avoidance in the long term. For instance, repeated issue avoidance due to overload could lead to general news avoidance over time. As an example, Brexit and COVID-19 have been discussed as causes of increasing news avoidance in the United Kingdom (Kalogeropoulos et al., 2020; Newman et al., 2019). Villi et al. (2022) found that exposure to extensively covered issues and the resultant overload perceptions drive general news avoidance. These long-term effects would make the study of issue-specific overload even more important.

From a policy perspective, it would be important to consider the effects of information overload and information avoidance on voting behavior. Particularly during referenda, where voting behavior is more volatile it is crucial to investigate how these mechanisms affect voting behavior. For instance, it could be possible that citizens who feel overloaded and avoid information are more prone to oppose a proposition and to retain the status quo, thus reinforcing the status quo effect often visible in direct democratic systems (Christin et al., 2002).

Conclusion

This study investigated to what extent citizens experience overload from a single issue extensively covered in the news and how this leads them to avoid the issue. Findings revealed that information overload from the issue in question was not very high at the aggregate level, but increased over the period of extensive news coverage. Information overload from the issue led individuals to avoid news on the issue, while avoidance of interpersonal discussions was not a consequence of increased overload. Thus, this study contributes to the study of news exposure in today’s news environment by providing new insights into issue-specific news overload and avoidance.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jmq-10.1177_10776990221127380 for Too Much Information? A Longitudinal Analysis of Information Overload and Avoidance of Referendum Information Prior to Voting Day by Julia Metag and Gwendolin Gurr in Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly

Author Biographies

Julia Metag (PhD, University of Muenster) is a professor at the Department of Communication at the University of Muenster, Germany. Her research interests include science communication, political communication, online communication, and media effects.

Gwendolin Gurr (PhD, University of Fribourg) is senior research and teaching assistant at the Department of Communication and Media Research (DCM), Université de Fribourg/Universität Freiburg, Switzerland. Her research interests include political communication, news media use and effects and attitudes toward news media and politics.

Table 6 in the Supplemental Appendix displays the correlations between all predictor variables.

Table 4 in the Supplemental Appendix displays the missing values per variable.

Therefore, the independent variables were group-mean- and grand-mean-centered (Hox, 2010).

The empty models, models including Level 1 predictors only, models including Level 2 predictors only, and models including Level 1 and Level 2 predictors without grand-mean- and group-mean-centering, are displayed in the Supplemental Appendix (Tables 1 and 2). Models with random slopes of all predictors could not be identified.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Schweizerischer Nationalfonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung (Swiss National Science Foundation), grant no. 100017_176356.

ORCID iD: Julia Metag  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4328-6419

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4328-6419

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Aalberg T., Blekesaune A., Elvestad E. (2013). Media choice and informed democracy: Toward increasing news consumption gaps in Europe? The International Journal of Press/Politics, 18(3), 281–303. 10.1177/1940161213485990 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aalberg T., Curran J. (2012). Introduction. In Aalberg T., Curran J. (Eds.), How media inform democracy: A comparative approach (pp. 4–14). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Allison P. D. (2009). Fixed effects regression models. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen K. (2022). Realizing good intentions? A field experiment of slow news consumption and news fatigue. Journalism Practice, 16, 848–863. 10.1080/17512786.2020.1818609 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology, 3(3), 265–299. 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0303_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bedingfield W. (2020, April 17). Coronavirus news fatigue is real and it could become a big problem. WIRED. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/coronavirus-news-fatigue

- Bennet S. E., Flickinger R. S., Rhine Staci L. (2000). Political talk over here, over there, over time. British Journal of Political Science, 30(1), 99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Boomgaarden H. (2014). Interpersonal and mass communicated political communication. In Reinemann C. (Ed.), Political communication: Handbooks of communication science (pp. 469–488). De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Brosius H.-B., Kepplinger H. M. (1990). The agenda-setting function of television news: Static and dynamic views. Communication Research, 17(2), 183–211. 10.1177/009365090017002003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen V. Y., Masullo Chen G. (2020). Shut down or turn off? The interplay between news overload and consumption. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 28(2), 125–137. 10.1080/15456870.2019.1616738 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christin T., Hug S., Sciarini P. (2002). Interests and information in referendum voting: An analysis of Swiss voters. European Journal of Political Research, 41, 759–776. [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin K., de Haan Y., Vliegenthart R., Kruikemeier S., Boukes M. (2021). News avoidance during the Covid-19 crisis: Understanding information overload. Digital Journalism, 9(9), 1286–1302. 10.1080/21670811.2021.1957967 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delli Carpini M. X., Keeter S. (1996). Political knowledge, political power, and the democratic citizen. In Delli Carpini M. X., Keeter S. (Eds.), What Americans know about politics and why it matters (pp. 1–21). Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Vreese C. H. (2007). The dynamics of referendum campaigns: An international perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- de Vreese C. H., Semetko H. A. (2006). Routledge research in political communication: Political campaigning in referendums: Framing the referendum issue. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Duronto P. M., Nishida T., Nakayama S. (2005). Uncertainty, anxiety, and avoidance in communication with strangers. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29(5), 549–560. 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dvořák T. (2013). Referendum campaigns, framing and uncertainty. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 23(4), 367–386. 10.1080/17457289.2013.764531 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edgerly S. (2021). The head and heart of news avoidance: How attitudes about the news media relate to levels of news consumption. Journalism, 23, 1828–1845. 10.1177/14648849211012922 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elenbaas M., de Vreese C. H. (2008). The effects of strategic news on political cynicism and vote choice among young voters. Journal of Communication, 58(3), 550–567. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00399.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eppler M. J., Mengis J. (2004). The concept of information overload: A review of literature from organization science, accounting, marketing, MIS, and related disciplines. The Information Society, 20(5), 325–344. 10.1080/01972240490507974 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eveland W. P., Jr. (2004). The effect of political discussion in producing informed citizens: The roles of information, motivation, and elaboration. Political Communication, 21(2), 177–193. 10.1080/10584600490443877 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eveland W. P., Jr., Morey A. C., Hutchens M. J. (2011). Beyond deliberation: New directions for the study of informal political conversation from a communication perspective. Journal of Communication, 61(6), 1082–1103. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01598.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geiss S. (2015). Die Aufmerksamkeitsspanne der Öffentlichkeit. Eine Studie zur Dauer und Intensität von Meinungsbildungsprozessen [The public’s attention span. A study on the duration and intensity of opinion formation processes]. Nomos. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried J. (2016, July 14). Most Americans already feel election coverage fatigue. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/07/14/most-americans-already-feel-election-coverage-fatigue/

- Gottfried J. (2020, February 26). Americans’ news fatigue isn’t going away—About two-thirds still feel worn out. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/02/26/almost-seven-in-ten-americans-have-news-fatigue-more-among-republicans/

- Goyanes M. (2014). News overload in Spain: The role of demographic characteristics, news interest, and consumer paying behavior. El Profesional de la Informacion, 23(6), 618–624. 10.3145/epi.2014.nov.09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goyanes M., Ardèvol-Abreu A., Zúñiga H. (2021). Antecedents of news avoidance: Competing effects of political interest, news overload, trust in news media, and “news finds me” perception. Digital Journalism. Advance online publication. 10.1080/21670811.2021.1990097 [DOI]

- Graham J. W. (2012). Statistics for social and behavioral sciences: Missing data: Analysis and design. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Groot Kormelink T., Klein Gunnewiek A. (2022). From “far away” to “shock” to “fatigue” to “back to normal”: How young people experienced news during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journalism Studies, 23, 669–686. 10.1080/1461670X.2021.1932560 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gurr G., Metag J. (2021). Examining avoidance of ongoing political issues in the news: A longitudinal study of the impact of audience issue fatigue. International Journal of Communication, 15, 1789–1809. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr G., Metag J. (2022). Fatigued by ongoing news issues? How repeated exposure to the same news issue affects the audience. Mass Communication and Society, 25(4), 578–599. 10.1080/15205436.2021.1956543 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hiltz S. R., Turoff M. (1985). Structuring computer-mediated communication systems to avoid information overload. Communications of the ACM, 28(7), 680–689. 10.1145/3894.3895 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hobolt S. B. (2005). When Europe matters: The impact of political information on voting behaviour in EU referendums. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 15(1), 85–109. 10.1080/13689880500064635 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holton A. E., Chyi H. I. (2012). News and the overloaded consumer: Factors influencing information overload among news consumers. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(11), 619–624. 10.1089/cyber.2011.0610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell J. L., Shepperd J. A. (2016). Establishing an information avoidance scale. Psychological Assessment, 28(12), 1695–1708. 10.1037/pas0000315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hox J. J. (2010). Quantitative methodology series: Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang M. I., Lin J. W. (1999). Information dimension, information overload and decision quality. Journal of Information Science, 25(3), 213–218. 10.1177/016555159902500305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson T. W., Farzaneh P. (2012). Theory-based model of factors affecting information overload. International Journal of Information Management, 32(6), 523–532. 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2012.04.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Q., Ha L., Sypher U. (2014). The role of news media use and demographic characteristics in the prediction of information overload. International Journal of Communication, 8, 699–714. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. R. (2005). Two-wave panel analysis: Comparing statistical methods for studying the effects of transitions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(4), 1061–1075. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00194.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalogeropoulos A., Fletcher R., Nielsen R. K. (2020). Initial surge in news use around coronavirus in the UK has been followed by significant increase in news avoidance. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/initial-surge-news-use-around-coronavirus-uk-has-been-followed-significant-increase-news-avoidance [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen R., Beyer A., Steen-Johnsen K. (2020). Do high-choice media environments facilitate news avoidance? A longitudinal study 1997–2016. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 64(5), 794–814. 10.1080/08838151.2020.1835428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. K., Sang H. S. (2017). An exploration of advertising avoidance by audiences across media. International Journal of Contents, 13(1), 76–85. 10.5392/IJoC.2017.13.1.076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kriesi H. (2005). Direct democratic choice: The Swiss experience. Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ksiazek T. B., Malthouse E. C., Webster J. G. (2010). News-seekers and avoiders: Exploring patterns of total news consumption across media and the relationship to civic participation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 54(4), 551–568. 10.1080/08838151.2010.519808 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A. (2000). The limited capacity model of mediated message processing. Journal of Communication, 50(1), 46–70. 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02833.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapinski M. K., Rimal R. N. (2005). An explication of social norms. Communication Theory, 15(2), 127–147. 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2005.tb00329.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leduc L. (2002). Opinion change and voting behaviour in referendums. European Journal of Political Research, 41(6), 711–732. 10.1111/1475-6765.00027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A. M., Holton A. E., Chen V. (2019). Unpacking overload: Examining the impact of content characteristics and news topics on news overload. Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies, 8(3), 273–290. 10.1386/ajms_00002_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. K., Kim K. S., Koh J. (2016). Antecedents of news consumers’ perceived information overload and news consumption pattern in the USA. International Journal of Contents, 12(3), 1–11. 10.5392/IJoC.2016.12.3.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. K., Lindsey N. J., Kim K. S. (2017). The effects of news consumption via social media and news information overload on perceptions of journalistic norms and practices. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 254–263. 10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Zheng H. (2022). Online information seeking and disease prevention intent during COVID-19 outbreak. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 99(1), 69–88. 10.1177/1077699020961518 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcinkowski F., Donk A. (2012). The deliberative quality of referendum coverage in direct democracy. Javnost—The Public, 19(4), 93–109. 10.1080/13183222.2012.11009098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matthes J. (2008). Need for orientation as a predictor of agenda-setting effects: Causal evidence from a two-wave panel study. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 20(4), 440–453. 10.1093/ijpor/edn042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matthes J. (2013). The affective underpinnings of hostile media perceptions: Exploring the distinct effects of affective and cognitive involvement. Communication Research, 40(3), 360–387. 10.1177/0093650211420255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCombs M. E. (2007). Agenda-setting. In Ritzer G. (Ed.), The Blackwell encyclopedia of sociology (Vol. 36, pp. 1–2). John Wiley. 10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosa025.pub2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newman N., Fletcher R., Kalogeropoulos A., Nielsen R. K. (2019). Reuters Institute digital news report 2019. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [Google Scholar]

- Oeldorf-Hirsch A. (2018). The role of engagement in learning from active and incidental news exposure on social media. Mass Communication and Society, 21(2), 225–247. 10.1080/15205436.2017.1384022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park C. S. (2019). Does too much news on social media discourage news seeking? Mediating role of news efficacy between perceived news overload and news avoidance on social media. Social Media + Society, 5(3), 1–12. 10.1177/2056305119872956 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poindexter P. M., McCombs M. E. (2001). Revisiting the civic duty to keep informed in the new media environment. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 78(1), 113–126. 10.1177/107769900107800108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prior M. (2007). Post-broadcast democracy: How media choice increases inequality in political involvement and polarizes elections. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roetzel P. G. (2018). Information overload in the information age: A review of the literature from business administration, business psychology, and related disciplines with a bibliometric approach and framework development. Business Research, 12, 479–522. 10.1007/s40685-018-0069-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheufele D. A. (2000). Talk or conversation? Dimensions of interpersonal discussion and their implications for participatory democracy. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 77(4), 727–743. 10.1177/107769900007700402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt J. B., Debbelt C. A., Schneider F. M. (2018). Too much information? Predictors of information overload in the context of online news exposure. Information, Communication & Society, 21(8), 1151–1167. 10.1080/1369118X.2017.1305427 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt-Beck R. (2000). Politische Kommunikation und Wählerverhalten: Ein internationaler Vergleich [Political communication and voter behavior: An International Comparison]. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. 10.1007/978-3-322-80381-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S. C. (1987). Information overload: Causes and consequences. Human Systems Management, 7(2), 143–153. 10.3233/HSM-1987-7207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm H., Wirth W. (2007). Emotionen und Emotionsregulation bei der Medienrezeption aus appraisaltheoretischer Perspektive [Emotion and emotion regulation during media exposure from the perspective of appraisal theory]. In Trepte S., Witte E. H. (Eds.), Sozialpsychologie und Medien [Social psychology and the media] (pp. 35–59). Pabst Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Schramm H., Wirth W. (2008). A case for an integrative view on affect regulation through media usage. Communications, 33(1), 27–46. 10.1515/COMMUN.2008.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck A. R., Boomgaarden H. G., de Vreese C. H. (2013). Cynics all around? The impact of election news on political cynicism in comparative perspective. Journal of Communication, 63(2), 287–311. 10.1111/jcom.12023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shehata A. (2014). Game frames, issue frames, and mobilization: Disentangling the effects of frame exposure and motivated news attention on political cynicism and engagement. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 26(2), 157–177. 10.1093/ijpor/edt034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shehata A., Wadbring I., Hopmann D. N. (2015, May 21). A longitudinal analysis of news-avoidance over three decades: From public service monopoly to smartphones [Paper presentation]. 65th Annual Conference of the International Communication Association (ICA), San Juan, Puerto Rico. [Google Scholar]

- Silvia P. J. (2008). Interest—The curious emotion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(1), 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Skovsgaard M., Andersen K. (2020). Conceptualizing news avoidance: Towards a shared understanding of different causes and potential solutions. Journalism Studies, 21(4), 459–476. 10.1080/1461670X.2019.1686410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders T. A. B., Bosker R. J. (2012). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling (2nd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Song H., Jung J., Kim Y. (2017). Perceived news overload and its cognitive and attitudinal consequences for news usage in South Korea. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 94(4), 1172–1190. 10.1177/1077699016679975 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Speck P. S., Elliott M. T. (1997). Predictors of advertising avoidance in print and broadcast media. Journal of Advertising, 26(3), 61–76. 10.1080/00913367.1997.10673529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strömbäck J. (2017). News seekers, news avoiders, and the mobilizing effects of election campaigns: Comparing election campaigns for the national and the European parliaments. International Journal of Communication, 11, 237–258. [Google Scholar]

- Strömbäck J., Djerf-Pierre M., Shehata A. (2013). The dynamics of political interest and news media consumption: A longitudinal perspective. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 25(4), 414–435. 10.1093/ijpor/eds018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stucki I., Pleger L. E., Sager F. (2018). The making of the informed voter: A split-ballot survey on the use of scientific evidence in direct-democratic campaigns. Swiss Political Science Review, 24(2), 115–139. 10.1111/spsr.12290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toff B., Kalogeropoulos A. (2020). All the news that’s fit to ignore: How the information environment does and does not shape news avoidance. Public Opinion Quarterly, 84(1), 366–390. 10.1093/poq/nfaa016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trilling D., Schoenbach K. (2013). Skipping current affairs: The non-users of online and offline news. European Journal of Communication, 28(1), 35–51. 10.1177/0267323112453671 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Udris L. (2020. a). Abstimmungsmonitor: Vorlagen vom 27. September 2020 [Voting monitor. Submissions from September 27, 2020]. fög—Forschungsinstitut Öffentlichkeit und Gesellschaft / Universität Zürich. 10.5167/uzh-197881 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Udris L. (2020. b). Abstimmungsmonitor: Vorlagen vom 29. November 2020 [Voting monitor. Submissions from November 29, 2020]. fög—Forschungsinstitut Öffentlichkeit und Gesellschaft / Universität Zürich. https://www.foeg.uzh.ch/dam/jcr:1fa14c2f-b22e-4572-9fcc-20a6157a3c4c/Abstimmungsmonitor_Zwischenbericht_November_2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- van Aelst P., Strömbäck J., Aalberg T., Esser F., de Vreese C. H., Matthes J., Hopmann D. N., Salgado S., Hubé N., Stępińska A., Papathanassopoulos S., Berganza R., Legnante G., Reinemann C., Sheafer T., Stanyer J. (2017). Political communication in a high-choice media environment: A challenge for democracy? Annals of the International Communication Association, 41(1), 3–27. 10.1080/23808985.2017.1288551 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Erkel P. F. A., van Aelst P. (2021). Why don’t we learn from social media? Studying effects of and mechanisms behind social media news use on general surveillance political knowledge. Political Communication, 38(4), 407–425. 10.1080/10584609.2020.1784328 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villi M., Aharoni T., Tenenboim-Weinblatt K., Boczkowski P. J., Hayashi K., Mitchelstein E., Tanaka A., Kligler-Vilenchik N. (2022). Taking a break from news: A five-nation study of news avoidance in the digital era. Digital Journalism, 10, 148–164. 10.1080/21670811.2021.1904266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waldherr A. (2014). Emergence of news waves: A social simulation approach. Journal of Communication, 64(5), 852–873. 10.1111/jcom.12117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson J., Eaker C. (2012, October 28). The information overload scale [Paper presentation]. 75th Annual Conference of the American Society for Information Science & Technology 2012, Baltimore, MD, United States. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data (2nd ed.). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wyant M. H., Hurst E. H., Reedy J. (2020). Political socialization of international students: Public-issue discourse and discussion on the college campus. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, 49(4), 372–393. 10.1080/17475759.2020.1785529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- York C. (2013). Overloaded by the news: Effects of news exposure and enjoyment on reporting information overload. Communication Research Reports, 30(4), 282–292. 10.1080/08824096.2013.836628 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jmq-10.1177_10776990221127380 for Too Much Information? A Longitudinal Analysis of Information Overload and Avoidance of Referendum Information Prior to Voting Day by Julia Metag and Gwendolin Gurr in Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly