Abstract

Purpose of Review

In this article, we review the most recent advancements in the approaches to EOS diagnosis and assessment, surgical indications and options, and basic science innovation in the space of early-onset scoliosis research.

Recent Findings

Early-onset scoliosis (EOS) covers a diverse, heterogeneous range of spinal and chest wall deformities that affect children under 10 years old. Recent efforts have sought to examine the validity and reliability of a recently developed classification system to better standardize the presentation of EOS. There has also been focused attention on developing safer, informative, and readily available imaging and clinical assessment tools, from reduced micro-dose radiographs, quantitative dynamic MRIs, and pulmonary function tests. Basic science innovation in EOS has centered on developing large animal models capable of replicating scoliotic deformity to better evaluate corrective technologies. And given the increased variety in approaches to managing EOS in recent years, there exist few clear guidelines around surgical indications across EOS etiologies. Despite this, over the past two decades, there has been a considerable shift in the spinal implant landscape toward growth-friendly instrumentation, particularly the utilization of MCGR implants.

Summary

With the advent of new biological and basic science treatments and therapies extending survivorship for disease etiologies associated with EOS, the treatment for EOS has steadily evolved in recent years. With this has come a rising volume and variation in management options for EOS, as well as the need for multidisciplinary and creative approaches to treating patients with these complex and heterogeneous disorders.

Keywords: Early-onset scoliosis, Thoracic insufficiency syndrome, Serial casting, Bracing, Growth-friendly instrumentation, VEPTR, MCGR, TGR, Spinal implant technology, Spinal imaging, Clinical assessment tools, Large animal models

Introduction

EOS, defined as scoliosis >10° diagnosed at onset in a child under 10 years old, emerges alongside a complex, varied set of etiologies and pathologies affecting the spine and/or thorax. Given the heterogeneous presentation of EOS, in recent years, there has been a concerted effort to better standardize the definition of EOS. As our understanding of the effect that scoliosis deformity has on the development of the chest wall, as well as on cardiopulmonary function and development, has solidified, these findings have significantly shifted the EOS treatment landscape. With this have come major recent advancements in the knowledge, technology, and techniques available to address rib and spinal deformities in patients with EOS. Here, we seek to provide an updated review of the trends and developments in the classification, management, and research surrounding EOS.

Diagnosis of EOS

The introduction of the Classification of Early-Onset Scoliosis (C-EOS) in recent years has sought to standardize the heterogeneous presentation of early-onset scoliosis using a continuous age prefix and four deformity characteristics: etiology, major curve magnitude, annual progression rate (APR), and kyphosis [1]. This classification system groups EOS into four etiologies (neuromuscular scoliosis, congenital/structural scoliosis, syndromic scoliosis, and idiopathic scoliosis), classifies major curve angle using four stages [1–4], denotes kyphosis using a (+) or (-), and describes the APR modifier using P0, P1, or P2.

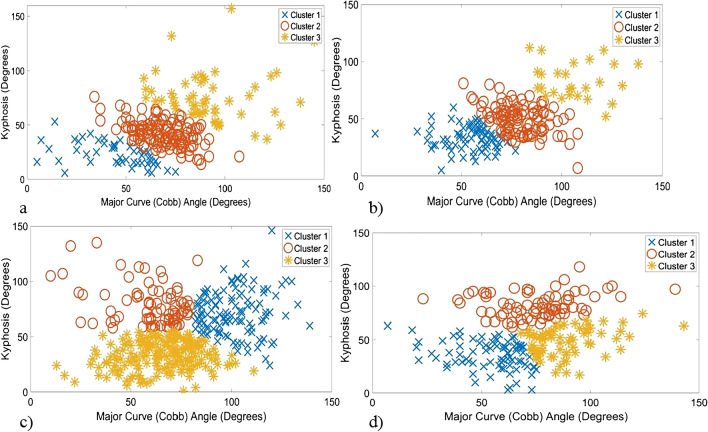

While existing literature reinforces the C-EOS classification’s efficacy and validity [2], recent studies have sought to evaluate the C-EOS system’s reproducibility and reliability for clinical and research purposes. A 2020 study by Dragsted et al. reported substantial agreement for disease etiology, strong reliability of major curve magnitude, moderate reliability for kyphosis, and a somewhat less reliable APR consensus [3]. And Cyr et al. found there to be high levels of interobserver and intra-observer agreement of the C-EOS scheme [4]. These studies support the notion that this prognostic tool can be reliably utilized in clinical and research spaces while suggesting that there is room for revision around APR. And to build on this C-EOS system, Viraraghavan and Balasubramanian et al. recently developed an automated, data-driven method to more systematically cluster EOS patients and ultimately improve the standardization of clinical decision-making (Fig. 1a–d) [5••].

Fig. 1.

(a–d) Scatter plot diagrams to visualize three clusters identified using pre-operative clinical indices (major curve (Cobb) angle, kyphosis) to distinguish sub-groups in each C-EOS etiology category: (a) congenital etiology, (b) idiopathic EOS etiology, (c) neuromuscular etiology, and (d) syndromic etiology. Reproduced with permission from Viraraghavan G, Cahill PJ, Vitale MG, Williams BA, Pediatric Spine Study G, Balasubramanian S. Automated Clustering Technique (ACT) for early onset scoliosis: a preliminary report. Spine Deform. 2023). Permission was received from SpringerLink to reproduce these figures

Recent efforts have also been made to characterize more systematically an older, heterogenous EOS patient population (“tweeners”) who are clinically indicated for multiple growth-friendly treatment options or definitive fusion due to their age and skeletal maturity [6].

Assessment

For thorough management of EOS, the main considerations include the age and medical history of the patient, their pulmonary status, the magnitude and progression rate of rib deformity, and the severity of the spinal deformity.

Medical History/Physical Examination

When evaluating a patient with EOS, a clinician’s careful review of a patient’s past and current medical history is crucial. At an initial visit, it is necessary to better contextualize the deformity by determining factors like when the deformity was first observed, who it was noticed by, and what prior treatments have been utilized. A thorough review of their overarching medical history is important – including birth history, past surgical history, underlying syndromes or neuromuscular conditions, respiratory events or infections, oxygen support, or hospitalization episodes. Any additional clinical updates, including neurological, urological, cardiological, neurosurgical, and endocrinological findings, should also be inquired about [7].

A thorough physical assessment is needed at each appointment. Carefully inspecting the chest for dimpling, sinus tracts, or scars allows clinicians to note any cutaneous signs of spinal dysraphism [8]. And the skin pinch test allows clinicians to qualitatively determine a patient’s tendency to handle a spinal device by observing their soft-tissue sleeve thickness. If it is possible to conduct, a full neurologic exam is crucial to monitor upper and lower extremity motor and sensory function and abdominal and deep tendon reflexes. An examination of the posterior chest wall is also needed to identify prominences from the corresponding deformity, fused rib cages or absent ribs, and test for flexibility of the deformity. A thumb excursion test is also an important tool to evaluate any loss of chest wall motion [9]. Recent literature also demonstrates how pulmonary function testing (PFT) to measure the lung volume of a child with EOS, particularly their forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume (FEV1), and total lung capacity (TLC), are valuable assessments to have in EOS management [10–14, 15••]. Several centers are now utilizing point-of-care spirometry assessments in their orthopedic outpatient clinics [16, 17].

Radiographic Evaluation

Radiographic evaluation is necessary to consistently monitor the magnitude and progression of the spinal and rib deformity. Radiographic measures like the Sanders hand score, status of the triradiate cartilage, and Risser sign can be utilized to assess a patient’s skeletal maturity and remaining growth potential, although in this patient population, the majority of children will likely present with open triradiate cartilage, Sanders score of 2 or below, and Risser of 0. Radiographic parameters capable of quantifying rib deformity are also valuable to assess pulmonary function.

The efficacy of biplanar EOS low-dose radiographs has been well studied [18, 19], particularly their ability to decrease radiation exposure while maintaining sufficient image quality. Pederson et al. recently reported on a new reduced micro-dose protocol for 3d reconstructions that their team determined to be an effective, reduced radiation option for patients with mild scoliosis [19]. And in 2023, Skaggs et al. sought to determine the effectiveness of pre-operative single supine radiographs in evaluating curve flexibility compared to side-bending radiographs among EOS patients, expanding on the work of Ramachandran et al., who examined this among AIS patients [20, 21]. Skaggs et al. determined that a single supine radiograph was highly predictive of side-bending radiographs, suggesting that side-bending radiographs – which can be difficult to obtain in this younger EOS population – might not be necessary for pre-operative planning. Standardization and best practice guidelines on pre-operative EOS evaluations are being prioritized in current multi-center study group efforts.

Advanced 3d imaging, such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging, are important tools to obtain to facilitate patient care, as they allow surgeons to visualize the deformity in three dimensions [22]. This can be crucial for complex pre-operative planning. And to further assess pulmonary function, quantitative dynamic MRI assessment can be appropriate, as it is a radiation-free image acquisition method that allows for the characterization of volume changes of lungs using the 4-d methodology, illustrating thoracic-abdominal organ structures and their movement [23, 24]. Using this methodology, QdMRI is able to quantify volumetric changes during the respiratory cycle, to assess regional differences and dynamic biomechanical deficits of respiratory function, and to quantify the impact of surgical intervention among EOS patients [25–27, 28•]. In 2021, a normative database of quantitative metrics of regional ventilatory or thoracic features, dynamics, and function during normal childhood development was developed by Tong et al. [28•] They determined that this quantitative data may ultimately provide clinicians with benchmark measures for quantifying surgical outcomes for patients with EOS or thoracic insufficiency syndrome (TIS).

Indications for Surgery

Considerations for operative intervention generally include an assessment of a child’s peak growth velocity, their curve magnitude and flexibility, and the potential for and rate of curve progression, all while assessing available spinal growth. Current surgical options for patients with EOS include posterior-based, growth-friendly instrumentation, including the magnetically controlled growing rod (MCGR), the vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib (VEPTR), and traditional growing rods (TGR), Shilla/growth guidance, as well as posterior spinal fusion.

Given the ever-evolving nature of EOS care, there exist no clear guidelines for when surgical intervention is most appropriate across complex EOS etiologies. In 2020, Hughes et al. examined this question, presenting six controversial EOS cases to ascertain whether expert consensus on surgical intervention (≥80%) could be reached [29••]. They found no consensus across these cases, suggesting the need for a universal clinical standard of care that can guide technological innovation. Recent studies have worked to elucidate surgical indications in general cases across EOS etiologies [30, 31].

In idiopathic early-onset scoliosis, surgical intervention is generally pursued when conservative treatment can no longer reliably control idiopathic curve progression [31]. In neuromuscular EOS, since nonoperative treatment is generally not as effective and rapid curve progression in this population can negatively influence their cardiac and pulmonary status, earlier surgical intervention has proven to be optimal [32]. Surgery is generally recommended in cases where a patient’s severe deformity leads to trunk imbalance, poor posture, back pain, and major pulmonary challenges. In syndromic scoliosis, treatment is generally dependent on the syndrome type and patient characteristics, including trunk size, functional status, and disability. And among patients with congenital EOS, surgery may be indicated when the congenital curve is progressive or when multiple congenital vertebral anomalies contribute toward exacerbating the curve progression.

In 2023, Matsumoto et al. sought to determine whether consensus and uncertainty over treatment options for EOS patients had substantially changed among expert surgeons between 2010 and 2020 [33]. They found that, in 2020, conservative intervention and distraction-based techniques were most often selected as interventions for EOS. Consensus for surgical intervention was reached for EOS patients older in age (6- or 9-year-olds) with increased (30°) curve progression, greater curve degree, and those with rigid over-flexible curves. They also found an increase in the preference of conservative treatment over distraction-based techniques for patients ≤3 years old, relative to 10 years ago. This preference for delayed surgical intervention in younger EOS patients has been partly driven by the desire to prevent complications associated with early EOS surgical intervention [34, 35].

Multidisciplinary Management of EOS

As treatment options and patient management evolve to meet the complexity of EOS, a multidisciplinary approach is now vital to comprehensively treat EOS. Interdepartmental collaboration and consistent communication with specialists who treat patients with EOS, including neurosurgery, gastroenterology, pulmonology, general surgery, and radiology, can clearly outline recommendations and important considerations to keep in mind during surgical planning. The unique perspectives of these specialties, including insights around factors like pre- and post-operative nutritional goals, preferred wound closure techniques, or appropriate anesthetic care, provide a fuller picture of patient care [23, 36–38].

Implant Selection

Given the recent evolution of EOS care, one major area of contention is appropriate implant selection [39, 40•]. A 2022 PSSG study led by Murphy et al. elucidated the trends in implant utilization among index surgical EOS cases, revealing how the spinal implant landscape has dramatically changed since 1994 [39]. They demonstrated how growth-friendly instrumentation has exponentially increased over the past 20 years and how currently MCGR implants are the predominant type of device utilized for index surgical intervention relative to TGR and VEPTR. Klyce et al. reported on similar findings in 2020, concluding that between 2007 and 2017, the utilization of VEPTR implants had decreased considerably (from 48 to 6%), as did the use of growth-guidance devices (from 10 to 3%), while the adoption of MCGR implants had increased from <5% between 2007 and 2009 to over 80% between 2015 and 2017 [40•].

MCGR

The magnetically controlled growing rod (MCGR) is a primary fusionless spinal instrumentation option for patients with EOS. Patients are periodically distracted at intervals ranging from 6 weeks to 6 months using an external remote control (ERC) in an outpatient clinical setting [41]. This implant has grown in popularity because it does not require recurrent open lengthenings, making it less invasive and reducing perioperative and intraoperative complications. Despite this, implant-related and wound-related complications emerge with the MCGR technology, ranging from implant or ERC malfunction to implant breakage or loosening, some of which require revision surgery [42, 43, 44•].

A 2022 study by Matsumuto et al. delineated the contraindications to MCGR, reporting that expert surgeon consensus suggests patients with insufficient spinal height, inadequate skin and soft tissue cover, a stiff spinal curve, a sagittal curve apex above T3, hyperkyphosis, or patients requiring repetitive MRI for their care should avoid MCGR implantation [45•].

Another recent article by Heyer et al. applied the concept of the “law of diminishing returns,” coined by Sankar et al., to describe the decreasing ability of TGRs to lengthen over consecutive lengthenings to MCGR rods [46••]. They found that MCGRs had a significantly diminished ability to lengthen over subsequent lengthenings across the primary, secondary, and conversion MCGR implant groups. They also found a significantly decreased lengthening ability in secondary MCGR implant types, suggesting that an initial MCGR implant has a better capacity for lengthening. They also elucidated that 70-mm actuators were more impacted by the law of diminishing returns than 90-mm actuators and that across etiologies, only syndromic scoliosis did not experience the law of diminishing returns, suggesting that the optimal MCGR candidate may be a syndromic EOS patient with no prior surgical treatment who can accommodate a 90-mm rod actuator.

VEPTR

The Vertical Expandable Prosthetic Titanium Rib or VEPTR (Synthes Spine, Westchester, PA) was developed by Dr. Robert M. Campbell as a treatment modality to control spinal and rib deformities in patients with TIS and EOS. VEPTR constructs can be attached from rib to rib, rib to spine, or rib to the pelvis and can use either the ribs, spine, or pelvis as anchors. Relative to traditional growing rods, which primarily work to control a child’s scoliosis, VEPTRs primarily work to control the chest wall deformity to facilitate respiratory stabilization.

El-Hawary et al. recently published updated 5-year follow-up data for EOS patients without rib anomalies treated with VEPTR [47]. They concluded that, at 5 years of VEPTR treatment, 79% of patients had an overall improvement of scoliosis and increased T1-T12 and T1-S1 height. Patients with less severe pre-operative major curves experienced significantly increased coronal spinal growth and preserved sagittal spine growth during the distraction period, while patients with more severe initial major curves experienced increases in their secondary scoliosis curve and kyphosis, findings consistent with prior literature [48].

TGR

Traditional growing rods (TGRs) are a distraction-based technique that target progressive early-onset scoliosis. There exists some ambiguity around when it is appropriate to utilize TGR compared to other distraction-based methods, like MCGR or VEPTR. Varley et al. sought to illuminate the preferred profile for patients treated with TGR amidst the MCGR era [49]. They found that TGR implants are preferential when treating stiff hyperkyphotic curves, more commonly noted in patients with congenital scoliosis and among patients with short stature. In these cases, TGR provides a more powerful distraction option. These findings are supported by the 2023 review by Matsumuto et al., which found a consensus among expert surgeons for TGR implant selection among patients 6 years of age presenting with large, rigid curves with hyperkyphosis [33].

Bachabi et al. also recently compared the long-term clinical and radiographic outcomes of traditional growing rods and VEPTR rods among idiopathic early-onset scoliosis [50]. They found that among this population, TGRs produced greater initial curve correction, less kyphosis, greater thoracic height gains, and a lower incidence of wound-related complications relative to VEPTR.

Anchor Selection

It is generally unclear what type of effect anchor selection in distraction-based interventions has on a patient’s outcomes and risk for complications. A recent review better characterized the use of MCGR proximal and distal anchor fixation for EOS between 2014 and 2017 [40•]. It concluded that, in that time period, spine-based proximal anchors were most often used (86%), with no change over time in the use of rib-based anchors for proximal fixation; and they observed an increase in the use of pelvic anchors as a distal fixation point over the three-year period.

Recent studies have sought to specifically assess whether anchor selection has an effect on the final spinal length and overall outcomes in EOS patients. A 2021 study by El-Bromboly et al. showed that both rib-based and spine-based proximal anchor types increased sagittal spine length for patients with non-idiopathic EOS undergoing distraction-based surgeries and also found that spine-based implants are more kyphogenic relative to rib-based implants in this patient population [51]. And in 2021, Matsumoto et al. examined the complication rates between patients treated with spine- vs. rib-based proximal anchors in growing instrumentation, finding a similar rate of implant-related complications across both groups, but a better overall curve correction among spine-based anchors [52]. These findings were similar to those reported by Meza et al. in 2020, who reported that proximal spine anchors in MCGR imparted greater deformity correction but did not have a significantly different risk of device complications compared to rib-based constructs [53].

Basic Science in EOS

Large animal models have been readily designed in recent years to induce – and eventually evaluate correction techniques for – scoliosis. Scoliotic deformity simulation in a porcine model has shown to be particularly effective due to their spine’s close anatomic resemblance to that of a human’s [54, 55]. Additionally, they have large spinal growth potential between 3 and 6 months of age, and their weight can replicate that of a child with EOS if timed appropriately.

In 2017, Bogie et al. sought to develop a porcine early-onset scoliosis model with the use of a radiopaque ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene posterior spinal tether to create a progressive lordoscoliosis curve and ultimately allow for preclinical testing of fusionless scoliosis correction techniques [56]. This model, however, was met with some challenges, including high rates of instrument and wound-related complications and regression of the deformity after tether release. Similarly, Sinder and the study authors described the development of a growing pig model dedicated to evaluating how tether-based modulation affects intervertebral disc development and potential deformation [57]. And in a growing porcine model with tether-induced bending, Moore et al. demonstrated how scoliotic deformity occurred in both the intervertebral disc and the vertebral body through 12 weeks of development before transitioning to only occurring in the vertebral body by 19 weeks; they posited that by 19 weeks, the deformity became related to growth modulation rather than disc degeneration [58].

In 2020, Gross et al. were successful in their creation of a thoracic hyperkyphotic deformity in a porcine model with a comparable size and growth potential to that of a child undergoing treatment for EOS deformity, concluding that their model can be used in future studies to evaluate the effect of corrective growth instrumentation on the immature spine [59•].

Mini-pig models have also recently been utilized as a model of scoliosis to demonstrate how the biomechanical properties of the flexible, growing spine can be harnessed to induce a scoliotic deformity [60, 61].

Management of Certain Diagnoses

Spinal Muscular Atrophy

One of the major recent advancements in the treatment of EOS has involved the care of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). SMA is a neuromuscular disorder resulting from a deficiency in SMN1 protein and subsequent alpha motor neuron degeneration. This disease is classically characterized by proximal muscle weakness, trunk weakness, and a decrease in pulmonary function. Children with SMA often develop spinal deformities associated with this neuromuscular condition [62–64].

With the advent of biologic treatments, such as nusinersin, risdiplam, and onasemnogene abeparvovec, survivorship curves are improving compared to the morbid natural history of this disease [65]. Now that these children are living longer, pediatric orthopedic surgeons are being asked to manage and treat pathology in a population who we historically did not evaluate. These circumstances require adaptive treatment options and techniques.

In defining expert consensus for surgical treatment in SMA patients, Hughes et al. found a near-consensus to treating SMA patients with growth-friendly instrumentation, specifically MCGR (75%), and they reported varied responses around proximal and distal anchor fixation choice, with 58% of surgeons reporting rib-based proximal anchors and 53% reporting iliac or sacral screws for distal anchor fixation [29••]. A 2020 study expanded on the impact of growth-friendly instrumentation on curve correction and pulmonary function in SMA patients, finding that these constructs improved spinal deformity and significantly improved hemithorax height, suggesting that these constructs can reliably control spinal deformity and may be effective in delaying respiratory decline [66]. And using the validated EOSQ-24, Matsumuto et al. reported similar findings on improvements in pulmonary function among children with SMA who received growth-friendly instrumentation [13].

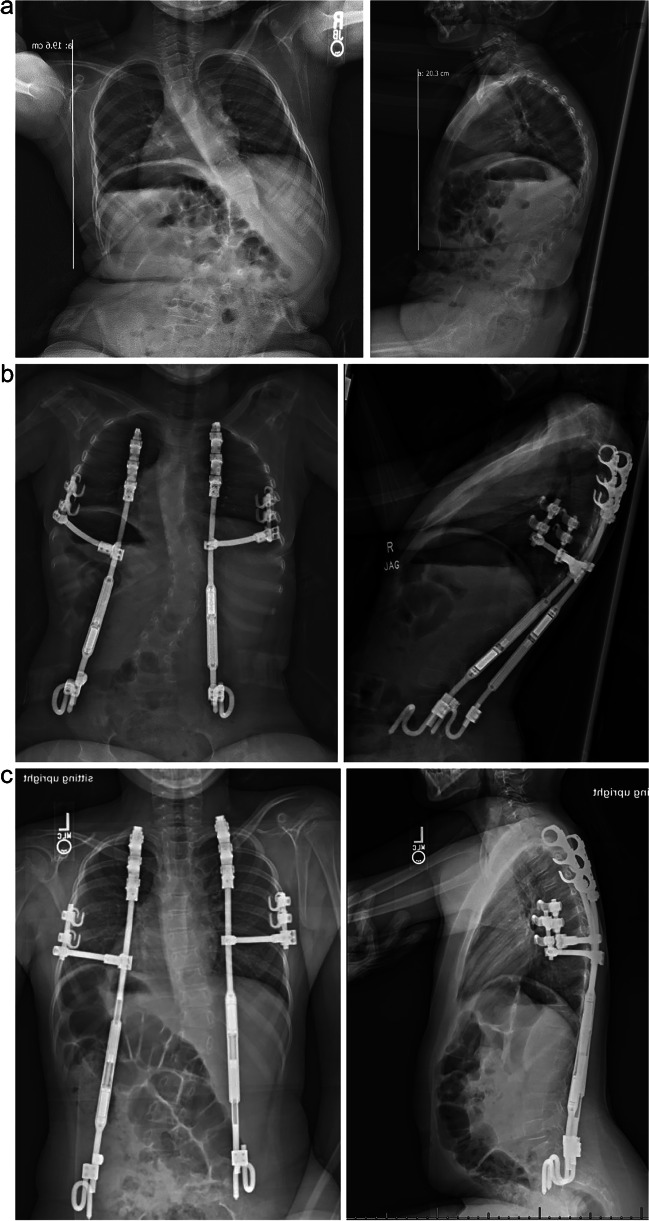

Our institution has adopted a new surgical treatment option for SMA patients with severe early-onset scoliosis to address both the parasol rib and spinal deformity: the Vertical Expandable Prosthetic Titanium Rib (VEPTR) with the rib gantry construct. This modification to the rib-based MCGR-VEPTR system includes a lateral rod structured to support the down-sloping ribs, which acts like out-riggers in a fishing vessel or a gantry crane. We believe that this technique, when paired with spinal deformity correction, most closely returns chest wall structure to normal in hopes of restoring then thoracic dynamics to preserve pulmonary function [67]. It also utilizes anchor points lateral to the spine on the ribs and pelvis, facilitating ease of access to the spinal canal, to more easily facilitate intrathecal administration of medications (Fig. 2a–c).

Fig. 2.

(a) Pre-operative radiographs of a 5-year-old male with SMA type 1 and thoracic insufficiency syndrome who presented with progressive scoliosis and parasol deformity. Imaging reveals a prominent dextrocurvature at the thoracolumbar junction and thoracic kyphosis. (b) 6-week post-operative radiographs of the 5-year-old male with SMA type 1 and thoracic insufficiency syndrome, highlighting implanted VEPTR anchors, MCGR rods, and one gantry on the left and right. Decreased scoliosis can be noted

Cerebral Palsy

Among patients with neuromuscular scoliosis associated with cerebral palsy (CP), there has been focused attention on comparing outcomes in patients treated with growth-friendly instrumentation versus definitive spinal fusion. Two major multicenter spine registries were recently queried to compare the radiographic outcomes, rates of complication and unplanned return to the operating room (UPROR), and quality of life outcomes between juvenile patients (8–10-year-olds) with CP who receive spinal fusion compared to growing rod treatment [68••]. This study found that spinal fusion treatment in this patient population resulted in better curve correction, fewer complications and UPRORs, as well as better radiographic and health-related quality of life outcomes. These findings were supported by an earlier review by Yaszay et al., which found that definitive spinal fusion in curves approaching 90 degrees resulted in good clinical and radiographic outcomes in a small cohort of CP patients [69].

Further examining differences in growth-friendly treatment options among this patient population, Sun et al. recently compared the risk of UPROR and the amount of deformity correction between CP patients treated with MCGR versus TGRs [70]. They found that MCGR implants demonstrated better maintenance of scoliosis correction than TGRs and that there was no difference in the risk of UPROR within the first 2 years postoperatively between patients treated with TGRs or MCGRs. Their study suggests that more intentional investigation is needed into ways to decrease the risk of complications associated with newer growth-friendly treatment options like MCGR.

Infantile Idiopathic Scoliosis

Conservative intervention in infantile idiopathic scoliosis (idiopathic scoliosis in patients ≤3 years) has been pivotal in correcting scoliosis and ultimately delaying or even preventing the need for surgical treatment [71–73]. Conservative management includes serial body casting and bracing. With serial body casting, as casts are periodically changed every 2–3 months, important considerations related to behavioral and brain development arise around the impact of repeated anesthetic exposure in young children [74]. In response to this, LaValva et al. recently compared the radiographic and clinical outcomes of patients who underwent serial body casting with and without general anesthesia [75•]. They found a higher rate of casting success (≥10° major curve angle improvement) in awake patients and a similar curve progression rate between groups, suggesting that general anesthesia might not be necessary during casting in cooperative patients and families.

And with growing interest in bracing for IIS, recent studies have sought to evaluate the effects of brace treatment for mild-to-severe IIS [76, 77]. In 2021, Negrini et al. examined the long-term radiographic outcomes of severe IIS patients undergoing bracing treatment, finding progressive improvements over time in 74% of IIS cases, concluding that bracing can be an effective treatment option for high-degree IIS [77]. A new multi-center, prospective study is underway to compare the clinical and radiographic outcomes between patients undergoing serial casting and bracing [78].

Conclusion

The management of EOS has continued to evolve steadily, given recent innovations in treatments of diseases with historically high morbidity, like spinal muscular atrophy. Spinal deformity surgery requires creative, multidisciplinary approaches to meet these new advancements in biological and basic science treatments. These considerations will become especially important as spinal surgeons work to optimize treatment in the complex and heterogenous EOS patient population.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors have no relevant conflicts of interest pertaining to this manuscript.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Williams BA, Matsumoto H, McCalla DJ, et al. Development and initial validation of the classification of early-onset scoliosis (C-EOS) J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(16):1359–1367. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park HY, Matsumoto H, Feinberg N, et al. The classification for early-onset scoliosis (C-EOS) correlates with the speed of vertical expandable prosthetic titanium rib (VEPTR) proximal anchor failure. J Pediatr Orthop. 2017;37(6):381–386. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dragsted C, Ohrt-Nissen S, Hallager DW, et al. Reproducibility of the classification of early onset scoliosis (C-EOS) Spine Deform. 2020;8(2):285–293. doi: 10.1007/s43390-019-00006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cyr M, Hilaire TS, Pan Z, et al. Classification of early onset scoliosis has excellent interobserver and intraobserver reliability. J Pediatr Orthop. 2017;37(1):e1–e3. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.•• Viraraghavan G, Cahill PJ, Vitale MG, Williams BA, Pediatric Spine Study G, Balasubramanian S. Automated clustering technique (ACT) for early onset scoliosis: a preliminary report. Spine Deform. 2023. Original research reporting on a new C-EOS classification system that provides an automated data-driven framework to increase standardization of EOS categorization and clinical decision-making. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Quan T, Matsumoto H, Bonsignore-Opp L, et al. Definition of tweener: consensus among experts in treating early-onset scoliosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2023;43(3):e215–e222. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fletcher ND, Bruce RW. Early onset scoliosis: current concepts and controversies. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2012;5(2):102–110. doi: 10.1007/s12178-012-9116-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sewell MJ, Chiu YE, Drolet BA. Neural tube dysraphism: review of cutaneous markers and imaging. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(2):161–170. doi: 10.1111/pde.12485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell RM, Jr, Smith MD, Mayes TC, et al. The characteristics of thoracic insufficiency syndrome associated with fused ribs and congenital scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(3):399–408. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200303000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xue X, Shen J, Zhang J, et al. An analysis of thoracic cage deformities and pulmonary function tests in congenital scoliosis. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(7):1415–1421. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang JG, Wang W, Qiu GX, Wang YP, Weng XS, Xu HG. The role of preoperative pulmonary function tests in the surgical treatment of scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(2):218–221. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000150486.60895.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsumoto H, Marciano G, Redding G, et al. Association between health-related quality of life outcomes and pulmonary function testing. Spine Deform. 2021;9(1):99–104. doi: 10.1007/s43390-020-00190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumoto H, Mueller J, Konigsberg M, et al. Improvement of Pulmonary function measured by patient-reported outcomes in patients with spinal muscular atrophy after growth-friendly instrumentation. J Pediatr Orthop. 2021;41(1):1–5. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Redding GJ. Early onset scoliosis: a pulmonary perspective. Spine Deform. 2014;2(6):425–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jspd.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redding G, Mayer OH, White K, et al. Maximal respiratory muscle strength and vital capacity in children with early onset scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2017;42(23):1799–1804. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redding GJ, Mayer OH. Structure-respiration function relationships before and after surgical treatment of early-onset scoliosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(5):1330–1334. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1621-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao ZH, Bao HD, Tseng CC, Zhu ZZ, Qiu Y, Liu Z. Prediction of respiratory function in patients with severe scoliosis on the basis of the novel individualized spino-pelvic index. Int Orthop. 2018;42(10):2383–2388. doi: 10.1007/s00264-018-3877-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ilharreborde B, Ferrero E, Alison M, Mazda K. EOS microdose protocol for the radiological follow-up of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(2):526–531. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-3960-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pedersen PH, Vergari C, Alzakri A, Vialle R, Skalli W. A reduced micro-dose protocol for 3D reconstruction of the spine in children with scoliosis: results of a phantom-based and clinically validated study using stereo-radiography. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(4):1874–1881. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5749-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skaggs KF, Bainton NM, Boby AZ, et al. Reliability of preoperative supine versus bending radiographs in estimating the structural nature of curves in EOS. J Pediatr Orthop. 2023;43(2):70–75. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000002305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramchandran S, Monsour A, Mihas A, George K, Errico T, George S. Impact of supine radiographs to assess curve flexibility in the treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Global Spine J. 2022;12(8):1731–1735. doi: 10.1177/2192568220988271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anari JB, Flynn JM, Campbell RM. Evaluation and treatment of early-onset scoliosis: a team approach. JBJS Rev. 2020;8(10)

- 23.Udupa JK, Tong Y, Capraro A. Understanding respiratory restrictions as a function of the scoliotic spinal curve in thoracic insufficiency syndrome: a 4D dynamic MR imaging study. J Pediatr Orthop. 2020;40(4):6. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tong Y, Udupa JK, Wileyto EP, et al. Quantitative dynamic MRI (QdMRI) volumetric analysis of pediatric patients with thoracic insufficiency syndrome. Proc SPIE Int Soc. Opt Eng. 2018;10578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Song J, Udupa JK, Tong Y, et al. Architectural analysis on dynamic MRI to study thoracic insufficiency syndrome. Proc SPIE Int Soc. Opt Eng. 2018;10576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Tong Y, Udupa JK, McDonough JM, et al. Lung parenchymal characterization via thoracic dynamic MRI in normal children and pediatric patients with TIS. Proc SPIE Int Soc. Opt Eng. 2021:11598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Tong Y, Udupa JK, McDonough JM, et al. Quantitative dynamic thoracic MRI: application to thoracic insufficiency syndrome in pediatric patients. Radiology. 2019;292(1):206–213. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019181731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong Y, Udupa JK, JM MD, et al. Thoracic quantitative dynamic MRI to understand developmental changes in normal ventilatory dynamics. Chest. 2021;159(2):712–723. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.07.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughes MS, Swarup I, Makarewich CA, et al. Expert consensus for early onset scoliosis surgery. J Pediatr Orthop. 2020;40(7):e621–e628. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Striano BMRC, Garg S. How often do you lengthen? A physician survey on lengthening practice for prosthetic rib devices. Spine Deform. 2018;6:4. doi: 10.1016/j.jspd.2017.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schlosser TPKMC, Tsirikos AI. Surgical management of early-onset scoliosis: indications and currently available techniques. Orthop Trauma. 2021;35(6):10. doi: 10.1016/j.mporth.2021.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim HS, Kwon JW, Park KB. Clinical issues in indication, correction, and outcomes of the surgery for neuromuscular scoliosis: narrative review in pedicle screw era. Neurospine. 2022;19(1):177–187. doi: 10.14245/ns.2143246.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsumoto H, Fano AN, Quan T. Re-evaluating consensus and uncertainty among treatment options for early onset scoliosis: a 10-year update. Spine Deform. 2023;11(1):14. doi: 10.1007/s43390-022-00561-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bess S, Akbarnia BA, Thompson GH, et al. Complications of growing-rod treatment for early-onset scoliosis: analysis of one hundred and forty patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(15):2533–2543. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Upasani VV, Parvaresh KC, Pawelek JB. Age at initiation and deformity magnitude influence complication rates of surgical treatment with traditional growing rods in early-onset scoliosis. Spine Deform. 2016;4:344–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jspd.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li X, Li Z, Lin Y, Tan H, Chen C, Shen J. Growing-rod implantation improves nutrition status of early-onset scoliosis patients: a case series study of minimum 3-year follow-up. BMC Surg. 2021;21(1):106. doi: 10.1186/s12893-021-01120-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ward JFD, Paul J. Wound closure in nonidiopathic scoliosis: does closure matter? J Pediatr Orthop. 2017;37(3):4. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldstein MJ, Kabirian N, Pawelek JB, et al. Quantifying anesthesia exposure in growing rod treatment for early onset scoliosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2017;37(8):e563–e566. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphy RF, Neel GB, Barfield WR, et al. Trends in the utilization of implants in index procedures for early onset scoliosis from the pediatric spine study group. J Pediatr Orthop. 2022;42(9):e912–e916. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000002221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klyce W, Mitchell SL, Pawelek J, et al. Characterizing use of growth-friendly implants for early-onset scoliosis: a 10-year update. J Pediatr Orthop. 2020;40(8):e740–e746. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.La Rosa G, Oggiano L, Ruzzini L. Magnetically controlled growing rods for the management of early-onset scoliosis: a preliminary report. J Pediatr Orthop. 2017;37(2):79–85. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abdelaal A, Munigangaiah S, Trivedi J, Davidson N. Magnetically controlled growing rods in the treatment of early onset scoliosis: a single centre experience of 44 patients with mean follow-up of 4.1 years. Bone Jt Open. 2020;1(7):405–414. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.17.BJO-2020-0099.R1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi E, Yaszay B, Mundis G, et al. Implant complications after magnetically controlled growing rods for early onset scoliosis: a multicenter retrospective review. J Pediatr Orthop. 2017;37(8):e588–e592. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lebel DE, Rocos B, Helenius I, et al. Magnetically controlled growing rods graduation: deformity control with high complication rate. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2021;46(20):E1105–E1112. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000004044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsumoto H, Sinha R, Roye BD. Contraindications to magnetically controlled growing rods: consensus among experts in treating early onset scoliosis. Spine Deform. 2022;10(6):8. doi: 10.1007/s43390-022-00543-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.•• Heyer JH, Anari JB, Baldwin KD, et al. Lengthening behavior of magnetically controlled growing rods in early-onset scoliosis: a multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2022; Study concluding that the MCGR rod experiences its own “law of diminishing returns” in EOS patients, finding that only 21.7% of MCGRs in their cohort reached maximum excursion, suggesting high failure rates and a need for rod revision in this patient population.

- 47.El-Hawary R, Morash K, Kadhim M, et al. VEPTR treatment of early onset scoliosis in children without rib abnormalities: long-term results of a prospective, multicenter study. J Pediatr Orthop. 2020;40(6):e406–e412. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.El-Hawary R, Samdani A, Wade J, et al. Rib-based Distraction Surgery Maintains Total Spine Growth. J Pediatr Orthop. 2016;36(8):841–846. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Varley ES, Pawelek JB, Mundis GM, Jr, et al. The role of traditional growing rods in the era of magnetically controlled growing rods for the treatment of early-onset scoliosis. Spine Deform. 2021;9(5):1465–1472. doi: 10.1007/s43390-021-00332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bachabi M, McClung A, Pawelek JB, et al. Idiopathic early-onset scoliosis: growing rods versus vertically expandable prosthetic titanium ribs at 5-year follow-up. J Pediatr Orthop. 2020;40(3):142–148. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.El-Bromboly Y, Hurry J, Padhye K, et al. The effect of proximal anchor choice during distraction-based surgeries for patients with nonidiopathic early-onset scoliosis: a retrospective multicenter study. J Pediatr Orthop. 2021;41(5):290–295. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matsumoto H, Fields MW, Roye DP. Complications in the treatment of EOS: is there a difference between rib vs. spine-based proximal anchors? Spine Deform. 2021;9(1):247–253. doi: 10.1007/s43390-020-00200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meza BC, Shah SA, Vitale MG, et al. Proximal anchor fixation in magnetically controlled growing rods (MCGR): preliminary 2-year results of the impact of anchor location and density. Spine Deform. 2020;8(4):793–800. doi: 10.1007/s43390-020-00102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bobyn JD, Little DG, Gray R, Schindeler A. Animal models of scoliosis. J Orthop Res. 2015;33(4):458–467. doi: 10.1002/jor.22797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Terhune EA, Monley AM, Cuevas MT, Wethey CI, Gray RS, Hadley-Miller N. Genetic animal modeling for idiopathic scoliosis research: history and considerations. Spine Deform. 2022;10(5):1003–1016. doi: 10.1007/s43390-022-00488-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bogie R, Roth AK, Willems PC, Weegen W, Arts JJ, van Rhijn LW. The development of a representative porcine early-onset scoliosis model with a standalone posterior spinal tether. Spine Deform. 2017;5(1):2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jspd.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sinder B, Fusco A, Anari JB. Tether-based modulation of scoliosis reflects IVD deformation: development of growing pig model. St. Louis, Missouri, USA: Scoliosis Research Society; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moore AC, Barba A, Newman HR. Progressive intervertebral disc and vertebral body adaptations induced by posterolateral tethering in a porcine scoliosis model. Stockholm, Sweden: Scoliosis Research Society; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gross RH, Wu Y, Bonthius DJ, et al. Creation of a porcine kyphotic model. Spine Deform. 2019;7(2):213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jspd.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wijdicks SPJ, Lemans JVC, Overweg G, et al. Induction of a representative idiopathic-like scoliosis in a porcine model using a multidirectional dynamic spring-based system. Spine J. 2021;21(8):1376–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2021.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cervera-Irimia J, Gonzalez-Miranda A, Riquelme-Garcia O, et al. Scoliosis induced by costotransversectomy in minipigs model. Med Glas (Zenica). 2019;16(2) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Evans GA, Drennan JC, Russman BS. Functional classification and orthopaedic management of spinal muscular atrophy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63B(4):516–522. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.63B4.7298675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Granata C, Merlini L, Magni E, Marini ML, Stagni SB. Spinal muscular atrophy: natural history and orthopaedic treatment of scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1989;14(7):760–762. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198907000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Phillips DP, Roye DP, Jr, Farcy JP, Leet A, Shelton YA. Surgical treatment of scoliosis in a spinal muscular atrophy population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990;15(9):942–945. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199009000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Darras BT, et al. Nusinersen versus sham control in infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1723–1732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Swarup I, MacAlpine EM, Mayer OH, et al. Impact of growth friendly interventions on spine and pulmonary outcomes of patients with spinal muscular atrophy. Eur Spine J. 2021;30(3):768–774. doi: 10.1007/s00586-020-06564-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Campbell R. VEPTR expansion thoracoplasty. In: Akbarnia B, editor. The Growing Spine. Stockholm, Sweden: Springer; 2016. pp. 669–690. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hariharan AR, Shah SA, Sponseller PD. Definitive fusions are better than growing rod procedures for juvenile patients with cerebral palsy and scoliosis: a prospective comparative cohort study. Spine Deform. 2023;11(1):145–152. doi: 10.1007/s43390-022-00577-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yaszay B, Sponseller PD, Shah SA, et al. Performing a definitive fusion in juvenile CP patients is a good surgical option. J Pediatr Orthop. 2017;37(8):e488–e491. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sun MM, Buckler NJ, Al Nouri M, et al. No difference in the rates of unplanned return to the operating room between magnetically controlled growing rods and traditional growth friendly surgery for children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2022;42(2):100–108. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sanders JO, D'Astous J, Fitzgerald M, Khoury JG, Kishan S, Sturm PF. Derotational casting for progressive infantile scoliosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29(6):581–587. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181b2f8df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ballhause TM, Moritz M, Hattich A. Serial casting in early onset scoliosis: syndromic scoliosis is no contraindication. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):554. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2938-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mehta MH. Growth as a corrective force in the early treatment of progressive infantile scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(9):1237–1247. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B9.16124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ganzberg S, The FDA. Warning on Anesthesia Drugs. Anesth Prog. 2017;64(2):57–58. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006-64.2.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.LaValva SM, MacAlpine EM, Kawakami N, et al. Awake serial body casting for the management of infantile idiopathic scoliosis: is general anesthesia necessary? Spine Deform. 2020;8(5):1109–1115. doi: 10.1007/s43390-020-00123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McAviney J, Brown BT. Treatment of infantile idiopathic scoliosis using a novel thoracolumbosacral orthosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s13256-021-03168-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Negrini S, Donzelli S, Jurenaite G, Negrini F, Zaina F. Efficacy of bracing in early infantile scoliosis: a 5-year prospective cohort shows that idiopathic respond better than secondary-2021 SOSORT award winner. Eur Spine J. 2021;30(12):3498–3508. doi: 10.1007/s00586-021-06889-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weinstein SL. Casting vs bracing for idiopathic early-onset scoliosis (CVBT). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04500041. 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04500041