Abstract

The red blood cell distribution width (RDW) is a routinely available blood marker that measures the variation of the size/volume of red blood cells. The aim of our study was to investigate the prognostic value of RDW in cardiac arrest patients and to assess whether RDW improves the prognostic value of three cardiac arrest-specific risk scores. Consecutive adult cardiac arrest patients admitted to the ICU of a Swiss university hospital were included. The primary outcome was poor neurological outcome at hospital discharge assessed by Cerebral Performance Category. Of 702 patients admitted to the ICU after cardiac arrest, 400 patients (57.0%) survived, of which 323 (80.8%) had a good neurological outcome. Higher mean RDW values showed an independent association with poor neurological outcomes at hospital discharge (adjusted OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.41; p < 0.001). Adding the maximum RDW value to the OHCA- CAHP- and PROLOGUE cardiac arrest scores improved prognostic performance. Within this cohort of cardiac arrest patients, RDW was an independent outcome predictor and slightly improved three cardiac arrest-specific risk scores. RDW may therefore support clinical decision-making.

Subject terms: Prognostic markers, Outcomes research, Cardiovascular diseases

Introduction

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) is an important cause of death worldwide, and survivors frequently suffer from physical, psychological, and cognitive sequelae1–4. As many patients in an early stage after cardiac arrest remain unconscious, prognosis and therapeutic options often need to be discussed with family members who act as surrogate decision-makers5. In these early goals of care discussions, expected outcomes, such as neurological outcome, including mortality or disabilities, might have an important impact on decision-making6. Therefore, early and reliable prognostic tools may help provide further therapeutic management guidance6. So far, some well-validated prognostic models for the prediction of good neurological outcome at hospital discharge after cardiac arrest have been proposed, such as the Out-of-hospital Cardiac Arrest [OHCA] score, the Cardiac Arrest Hospital Prognosis [CAHP] score, and the Prognostication using logistic regression model for unselected adult cardiac arrest patients in the early stages [PROLOGUE] score7–10.

A previous study assessed the short-term prognostic value of various routine blood markers, whereas some markers, such as procalcitonin and lactate were able to improve the prognostic performance of a parsimonious clinical prediction model for mortality and neurological outcome11. Thus, addition of routine blood markers to clinical prediction models seems to be a promising approach, as these parameters are usually inexpensive and widely available. Among routine blood markers, the red blood cell distribution width (RDW), measures the variation of the size/volume of red blood cells and is often reported routinely as part of the complete blood count12, 13. RDW is calculated by dividing the standard deviation (SD) of erythrocytes volume by the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) of erythrocytes expressed as percentage14, 15. Commonly, RDW is used in anemia diagnostics, but it recently gained attention for prognostic research by acting as an independent risk factor for death in acute coronary syndrome, lung cancer, acute pulmonary embolism, and unselected intensive care unit [ICU] patients13, 14, 16–20. However, only a few studies assessed the prognostic value of RDW in cardiac arrest patients. In the Korean Cardiac Arrest Research Consortium Study [KoCARC study], RDW was found to be independently associated with poor neurological outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with a good prognostic performance (area under the curve [AUC] 0.63)21. Herein, our aim was to validate the results of the KoCARC Study in a large prospective Swiss cohort of cardiac arrest survivors and to investigate if the addition of RDW to three cardiac arrest specific scores (i.e., OHCA-, CAHP-, and PROLOGUE score) improves prediction model performance.

Methods

Study setting

Data were prospectively collected on patients in the ongoing COMMUNICATE/PROPHETIC study at a tertiary teaching hospital in Switzerland (University Hospital Basel). Details of the study procedure have been published previously4, 11, 22–31. Depending on the patients’ cognitive abilities, the informed consent was given by the patient or a medical guardian. If a medical guardian could not be located, an independent physician acted as the surrogate decision-maker.

The Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis [TRIPOD] statement guided us through the analysis and reporting of this study32–34.

Participants

Adult patients with return of spontaneous circulation [ROSC] after out-of-hospital [OHCA] or in-hospital [IHCA] cardiac arrest who were admitted to the intensive care unit [ICU] of the University Hospital Basel after cardiac arrest were eligible for inclusion in this study. Monitored patients (e.g., ICU, operating room, cardiac catheterization laboratory) and those who refused informed consent were excluded. Patients’ treatment was based on the standardized local treatment protocol in accordance with the guidelines of the European Resuscitation Council35, 36.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was poor neurological outcome at hospital discharge after cardiac arrest as assessed by the Cerebral Performance Category [CPC] scale37. The scale is divided into five categories of functional outcomes: A score of 1 implies good recovery with readmission of everyday life, however, mild neurological or psychological symptoms might be present, a score of 2 implies moderate disability with independence regarding activities of daily living, a score of 3 implies severe disability with dependence on others for activities of daily living, a score of 4 implies any state of coma or persistent vegetative state and a score of 5 includes death or brain death37. The secondary outcome was in-hospital mortality. According to previous studies, we dichotomized levels 1 (good recovery) and 2 (moderate disability) as good neurological outcome, whereas levels 3 (severe disability), 4 (vegetative state) and 5 (death) were defined as poor neurological outcome5, 6.

Data collection

The routine blood markers, including RDW, were collected at ICU admission (day 0) and on day 1, 3, 5, 7, as well as on the day of discharge from the ICU. RDW was assessed by the ADVIA hematology system (SIEMENS Healthineers International, Zurich, Switzerland) using impedance with hydrodynamic focusing. RDW is a percentage value with a theoretical range from 0 to 100. For the purpose of this study referred to as ‘RDW value’.

The following data was extracted from the electronic patient record: Demographics (i.e. gender, age), coexisting morbidities (i.e,. coronary artery disease, heart failure, neurologic disease, diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], chronic kidney disease, liver cirrhosis and malignancy), resuscitation details (setting of cardiac arrest, observed cardiac arrest, provision of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation [CPR], initial rhythm, no-flow time, time until ROSC), etiology of cardiac arrest, clinical and laboratory values (i.e. blood pressure on ICU admission, Glasgow Coma Scale [GCS], red blood cell distribution width, hematocrit, blood pH, lactate) and CPC score at hospital discharge.

The three clinical risk scores used in this study are composed as follows: The OHCA score is calculated by five clinical (no-flow and low-flow interval, initial rhythm) and laboratory values (creatinine, lactate)7, 31. The CAHP score contains additional information on resuscitative measures (location of cardiac arrest, epinephrine dosage) and another laboratory parameter (pH) at ICU admission8, 31. The PROLOGUE score omits the no-flow time and includes different resuscitation details (unwitnessed arrest, low-flow time, non-shockable rhythm), clinical and laboratory values (age, GCS, pupillary light reflex, adrenaline dose, phosphate, creatinine, hemoglobin, lactate, potassium)10, 31.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed by STATA 15.0 using descriptive statistics to specify our cohort with mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and frequencies for binary and categorical variables. Continuous variables were visually inspected for normal distribution. A two-sided T-test was used for the analysis of continuous variables, whereas a chi-square test was used for binary and categorical variables. The discrimination of RDW values was calculated by receiver operating characteristics [ROCs] and the corresponding AUC.

To evaluate the association of RDW with our primary and secondary outcomes, univariate and multivariable analyses were performed. The models were adjusted for predefined known confounders of RDW13, 38–40 such as age, gender, hematocrit, and comorbidities. Odds ratios [OR] with 95% confidence interval [CI] were calculated using logistic regression for poor neurological outcome and mortality.

The multivariable model was performed by adding the OHCA-, CAHP- and PROLOGUE score to assess the effect of the maximum RDW values over days 0, 1, 3, 5, 7 and ICU discharge on the association with outcomes. In line with the KoCARC study21 we calculated 4 quartiles of the mean RDW value with the following ranges: < 13.5, 13.5–14.3, 14.3–15.5, > 15.5.

We investigated specificity and sensitivity using cut-offs regarding poor neurological outcome at hospital discharge. The highest specificity for poor neurological outcome was observed at a maximum RDW value of 13.2, and maximum sensitivity was observed at a maximum RDW value of 16.6. Maximum specificity for mortality at hospital discharge was observed at a maximum RDW value of 13.2, and maximum sensitivity was observed at a maximum RDW value of 17 using the Youden Index.

In addition, RDW cut-offs for the prediction of good neurological outcome at hospital discharge (mean RDW value; cut-off 14.6) and survival to hospital discharge (mean RDW value; cut-off 15.5) as defined by Cheng et al. were validated41. The mean RDW values on day 0 and day 7 were compared using a two-tailed paired t-test.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was permitted by the Ethics Committee of North-western and Central Switzerland (www.eknz.ch) and led by the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Seven hundred and two consecutive patients admitted to the ICU with ROSC after cardiac arrest were included. Overall, every patient had at least one RDW measurement.

Until hospital discharge 400 patients (57.0%) survived, of which 323 (80.8%) had a good neurological outcome. Table 1 depicts the baseline characteristics stratified by neurological outcome at hospital discharge. The mean age was approximately 65 years, and 506 patients (72.1%) were male. The majority of cases were out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (83.5%), whereas 16.5% were survivors of an in-hospital cardiac arrest. The most frequent cause of cardiac arrest was coronary artery disease (333 patients, 47.8%). Patients with poor neurological outcome at hospital discharge were older (mean ± SD age 67.2 years, ± 13.9 vs. 61.8 years, ± 14.2; p < 0.001) and had a higher rate of pre-cardiac arrest comorbidities: COPD (15.3% vs. 5.6%; p < 0.001), malignant disease (14.9% vs. 6.8%; p < 0.001), neurological disease (19.0% vs. 9.3%; p < 0.001), diabetes (24.3% vs. 18.0%; p = 0.04) However, survivors with a good neurological outcome more often had pre-cardiac arrest evidence of coronary artery disease (64.1% vs. 52.9%; p = 0.003). Patients with a poor neurological outcome at hospital discharge had a longer mean no-flow time (4.71 min vs. 1.18 min; p < 0.001) and less often received bystander CPR (60.3% vs. 83.9%; p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Factor | All patients (N = 702) |

Good neurological outcome: CPC 1–2 (N = 323) |

Poor neurological outcome: CPC 3–5 (N = 379) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age [years], mean (SD) | 64.7 (14.3) | 61.8 (14.2) | 67.2 (13.9) | < 0.001 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 506 (72.1%) | 255 (78.9%) | 251 (66.2%) | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 407 (58.1%) | 207 (64.1%) | 200 (52.9%) | 0.003 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 100 (14.3%) | 38 (11.8%) | 62 (16.4%) | 0.08 |

| COPD, n (%) | 76 (10.8%) | 18 (5.6%) | 58 (15.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Liver disease, n (%) | 19 (2.7%) | 5 (1.5%) | 14 (3.7%) | 0.1 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 362 (51.6%) | 169 (52.3%) | 193 (51.1%) | 0.76 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 150 (21.4%) | 58 (18.0%) | 92 (24.3%) | 0.04 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 95 (13.6%) | 37 (11.5%) | 58 (15.3%) | 0.15 |

| Malignant disease, n (%) | 78 (11.1%) | 22 (6.8%) | 56 (14.9%) | < 0.001 |

| Neurological disease, n (%) | 102 (14.6%) | 30 (9.3%) | 72 (19.0%) | < 0.001 |

| Resuscitation measures | ||||

| No-flow Time [min], mean (SD) | 3.01 (5.27) | 1.18 (2.66) | 4.71 (6.41) | < 0.001 |

| Time until ROSC [min], mean (SD) | 22.02 (18.38) | 16.19 (13.75) | 27.41 (20.38) | < 0.001 |

| Observed cardiac arrest, n (%) | 572 (81.6%) | 293 (90.7%) | 279 (73.8%) | < 0.001 |

| Bystander CPR, n (%) | 499 (71.2%) | 271 (83.9%) | 228 (60.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Setting of cardiac arrest | < 0.001 | |||

| At home, n (%) | 258 (37.2%) | 92 (29.0%) | 166 (44.1%) | |

| Public, n (%) | 321 (46.3%) | 173 (54.6%) | 148 (39.4%) | |

| IHCA, n (%) | 114 (16.5%) | 52 (16.4%) | 62 (16.5%) | |

| Cause of cardiac arrest | < 0.001 | |||

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 333 (47.8%) | 195 (61.3%) | 138 (36.4%) | |

| Primary arrhythmia, n (%) | 100 (14.3%) | 53 (16.7%) | 47 (12.4%) | |

| Other/unknown, n (%) | 264 (37.9%) | 70 (22.0%) | 194 (51.2%) | |

| Initial rhythm | < 0.001 | |||

| Ventricular fibrillation, n (%) | 335 (47.9%) | 217 (67.2%) | 118 (31.3%) | |

| Ventricular tachycardia, n (%) | 33 (4.7%) | 18 (5.6%) | 15 (4.0%) | |

| Asystole, n (%) | 113 (16.1%) | 14 (4.3%) | 99 (26.3%) | |

| Pulseless electrical activity, n (%) | 159 (22.7%) | 36 (11.1%) | 123 (32.6%) | |

| Unknown, n (%) | 60 (8.6%) | 38 (11.8%) | 22 (5.8%) | |

| Initial Status at ICU admission | ||||

| Total GCS, mean (SD) | 6 (4) | 7 (5) | 4 (3) | < 0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure [mmHg], mean (SD) | 115 (25) | 116 (22) | 115 (28) | 0.45 |

| Diastolic blood pressure [mmHg], mean (SD) | 67 (17) | 69 (15) | 65 (18) | < 0.001 |

| Mean arterial pressure [mmHg], mean (SD) | 82 (18) | 84 (16) | 81 (19) | 0.01 |

| Initial pH, mean (SD) | 7.21 (.166) | 7.26 (.135) | 7.17 (.175) | < 0.001 |

| Initial lactate [mmol/l], mean (SD) | 6.45 (4.41) | 4.66 (3.5) | 7.89 (4.55) | < 0.001 |

| Hematocrit [l/l], mean (SD) | .395 (.0697) | .402 (.062) | .39 (.0751) | 0.03 |

| Diagnostic measures | ||||

| RDW max [%], mean (SD) | 14.77 (1.96) | 14.30 (1.64) | 15.18 (2.11) | < 0.001 |

| RDW max [%], median | 14.30 (13.50, 15.50) | 13.80 (13.20, 15.00) | 14.60 (13.80, 15.90) | < 0.001 |

COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CPC cerebral performance category scale, CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ICU intensive care unit, IHCA in-hospital cardiac arrest, GCS glasgow coma scale; n number, RDW red cell distribution width, ROSC return of spontaneous circulation, SD standard deviation.

Significant values are in Italic.

Association of RDW and risk scores with neurological outcome at hospital discharge

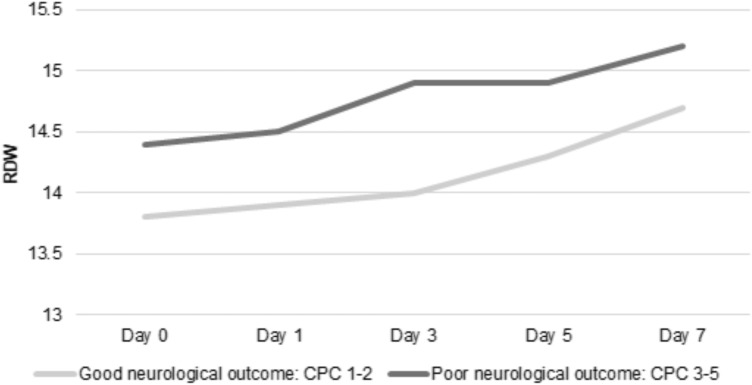

Higher mean RDW values were independently associated with poor neurological outcome at hospital discharge (mean, ± SD 15 ± 2 vs 14 ± 2, adjusted OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.14–1.41; p < 0.001; Table 2). Patients with poor neurological outcome at hospital discharge had higher mean RDW values on day 0, 1, 3 and 5. The highest mean RDW difference between patients with poor and good neurological outcome, as illustrated in Fig. 1, was found on day 3 (mean ± SD 14.9 ± 2.02 vs. 14 ± 1.51, adjusted OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.10–1.49; p = 0.002).

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis.

| Good neurological outcome: CPC 1–2 (N = 323) |

Poor neurological outcome: CPC 3–5 (N = 379) |

p-value | Univariate | Multivariable* adjusted | RDW and OHCA score: multivariable* adjusted | RDW and CAHP score: multivariable* adjusted | RDW and PROLOGUE score: multivariable* adjusted | Univariate | Multivariable* adjusted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI), p | OR (95%CI), p | OR (95%CI), p | OR (95%CI), p | OR (95%CI), p | AUC | AUC combined with RDW Max | ||||

| A Primary outcome: Neurological outcome at hospital discharge | ||||||||||

| RDW Max, mean (SD) | 14 (2) | 15 (2) | < 0.001 | 1.31 (1.19, 1.44), p < 0.001 | 1.27 (1.14, 1.41), p < 0.001 | 1.19 (1.06, 1.33), p = 0.002 | 1.19 (1.07, 1.34), p = 0.002 | 1.2 (1.08, 1.33), p = 0.001 | 0.65 | n.a |

| RDW Max, median (IQR) | 14 (13, 15) | 15 (14, 16) | < 0.001 | |||||||

| Quartiles of RDW Max., n (%) | 123 (38.1%) | 72 (19.0%) | < 0.001 | (Ref 1) | (Ref 1) | (Ref 1) | (Ref 1) | (Ref 1) | n.a | n.a |

| 2nd quartile, n (%) | 90 (27.9%) | 87 (23.0%) | 1.65 (1.09, 2.5), p = 0.02 | 1.4 (0.91, 2.17), p = 0.13 | 1.21 (0.72, 2.03), p = 0.48 | 1.09 (0.65, 1.84), p = 0.75 | 1.04 (0.64, 1.68), p = 0.89 | |||

| 3rd quartile, n (%) | 60 (18.6%) | 104 (27.4%) | 2.96 (1.92, 4.56), p < 0.001 | 2.41 (1.53, 3.8), p < 0.001 | 1.91 (1.11, 3.31), p = 0.02 | 1.88 (1.09, 3.25), p = 0.02 | 1.58 (0.95, 2.62), p = 0.08 | |||

| 4th quartile, n (%) | 50 (15.5%) | 116 (30.6%) | 3.96 (2.55, 6.16), p < 0.001 | 3.14 (1.91, 5.15), p < 0.001 | 2.32 (1.3, 4.14), p = 0.005 | 2.17 (1.21, 3.9), p = 0.01 | 2.33 (1.36, 4.01), p = 0.002 | |||

| RDW Day 0, mean (SD) | 13.8 (1.36) | 14.4 (1.87) | < 0.001 | 1.29 (1.16, 1.44), p < 0.001 | 1.18 (1.05, 1.33), p = 0.006 | 1.1 (0.97, 1.26), p = 0.13 | 1.11 (0.97, 1.26), p = 0.12 | 1.12 (0.99, 1.27), p = 0.07 | ||

| RDW Day 1, mean (SD) | 13.9 (1.34) | 14.5 (1.81) | < 0.001 | 1.35 (1.2, 1.52), p < 0.001 | 1.26 (1.1, 1.44), p = 0.001 | 1.17 (1.02, 1.35), p = 0.03 | 1.19 (1.03, 1.36), p = 0.02 | 1.19 (1.05, 1.36), p = 0.009 | ||

| RDW Day 3, mean (SD) | 14 (1.51) | 14.9 (2.02) | < 0.001 | 1.37 (1.19, 1.57), p < 0.001 | 1.28 (1.1, 1.49), p = 0.002 | 1.24 (1.06, 1.45), p = 0.007 | 1.25 (1.07, 1.46), p = 0.005 | 1.26 (1.08, 1.46), p = 0.003 | ||

| RDW Day 5, mean (SD) | 14.3 (1.65) | 14.9 (1.8) | 0.007 | 1.23 (1.05, 1.44), p = 0.009 | 1.2 (1, 1.44), p = 0.06 | 1.16 (0.95, 1.41), p = 0.15 | 1.17 (0.96, 1.42), p = 0.11 | 1.18 (0.98, 1.42), p = 0.08 | ||

| RDW Day 7, mean (SD) | 14.7 (1.8) | 15.2 (1.74) | 0.063 | 1.19 (0.99, 1.44), p = 0.07 | 1.18 (0.95, 1.46), p = 0.14 | 1.11 (0.89, 1.4), p = 0.34 | 1.15 (0.93, 1.44), p = 0.21 | 1.17 (0.94, 1.45), p = 0.16 | ||

| RDW at ICU discharge, mean (SD) | 14.1 (1.6) | 15.1 (2.13) | < 0.001 | 1.39 (1.26, 1.54), p < 0.001 | 1.33 (1.19, 1.49), p < 0.001 | 1.23 (1.09, 1.39), p = 0.001 | 1.23 (1.09, 1.39), p = 0.001 | 1.25 (1.11, 1.4), p < 0.001 | ||

| OHCA, mean (SD) | 8 (18) | 30 (18) | < 0.001 | 1.07 (1.06, 1.08), p < 0.001 | 1.07 (1.06, 1.09), p < 0.001 | n.a | n.a | n.a | 0.82 | 0.83, p < 0.05 |

| CAHP, mean (SD) | 128 (39) | 185 (42) | < 0.001 | 1.03 (1.03, 1.04), p < 0.001 | 1.03 (1.03, 1.04), p < 0.001 | 0.83 | 0.84, p = 0.03 | |||

| PROLOGUE, mean (SD) | 231 (103) | 332 (106) | < 0.001 | 1.01 (1.01, 1.01), p < 0.001 | 1.01 (1.01, 1.01), p < 0.001 | 0.75 | 0.77, p = 0.02 | |||

| Survivors (N = 400) |

Non-Survivors (N = 302) |

p-value | Univariate | Multivariable* adjusted | RDW and OHCA score: multivariable* adjusted | RDW and CAHP score: multivariable* adjusted | RDW and PROLOGUE score: multivariable* adjusted | Univariate | Multivariable* adjusted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI), p | OR (95%CI), p | OR (95%CI), p | OR (95%CI), p | OR (95%CI), p | AUC | AUC combined with RDW Max | ||||

| B Secondary endpoint: Mortality at hospital discharge | ||||||||||

| RDW Max, mean (SD) | 14.5 (1.87) | 15.1 (2.04) | < 0.001 | 1.16 (1.07, 1.25), p < 0.001 | 1.1 (1.01, 1.21), p = 0.04 | 1.03 (0.93, 1.14), p = 0.59 | 1.03 (0.92, 1.14), p = 0.63 | 1.04 (0.94, 1.15), p = 0.46 | 0.61 | n.a |

| RDW Max, median (IQR) | 14 (13, 15) | 15 (14, 16) | < 0.001 | |||||||

| Quartiles of RDW Max, n (%) | 135 (33.8%) | 60 (19.9%) | < 0.001 | (Ref 1) | (Ref 1) | (Ref 1) | (Ref 1) | (Ref 1) | n.a | n.a |

| 2nd quartile, n (%) | 106 (26.5%) | 71 (23.5%) | 1.51 (0.98, 2.31), p = 0.06 | 1.32 (0.85, 2.07), p = 0.22 | 1.14 (0.67, 1.93), p = 0.63 | 1.05 (0.61, 1.8), p = 0.85 | 0.91 (0.54, 1.52), p = 0.71 | |||

| 3rd quartile, n (%) | 80 (20.0%) | 84 (27.8%) | 2.36 (1.53, 3.64), p < 0.001 | 1.97 (1.25, 3.1), p = 0.003 | 1.42 (0.83, 2.45), p = 0.2 | 1.47 (0.85, 2.53), p = 0.17 | 1.13 (0.67, 1.91), p = 0.65 | |||

| 4th quartile, n (%) | 79 (19.8%) | 87 (28.8%) | 2.48 (1.61, 3.81), p < 0.001 | 1.81 (1.12, 2.94), p = 0.02 | 1.19 (0.67, 2.1), p = 0.55 | 1.11 (0.62, 1.98), p = 0.73 | 1.19 (0.69, 2.06), p = 0.54 | |||

| RDW Day 0, mean (SD) | 13.9 (1.55) | 14.4 (1.82) | < 0.001 | 1.17 (1.07, 1.29), p = 0.001 | 1.08 (0.98, 1.21), p = 0.13 | 1.01 (0.89, 1.14), p = 0.9 | 1.01 (0.89, 1.14), p = 0.93 | 1.03 (0.91, 1.15), p = 0.68 | ||

| RDW Day 1, mean (SD) | 14 (1.59) | 14.5 (1.66) | 0.001 | 1.17 (1.06, 1.3), p = 0.002 | 1.09 (0.97, 1.22), p = 0.16 | 1 (0.87, 1.14), p = 0.98 | 1.02 (0.89, 1.16), p = 0.79 | 1.03 (0.91, 1.17), p = 0.63 | ||

| RDW Day 3, mean (SD) | 14.3 (1.77) | 14.8 (1.91) | 0.004 | 1.18 (1.05, 1.32), p = 0.005 | 1.1 (0.96, 1.26), p = 0.16 | 1.07 (0.93, 1.24), p = 0.32 | 1.08 (0.93, 1.24), p = 0.31 | 1.08 (0.94, 1.24), p = 0.25 | ||

| RDW Day 5, mean (SD) | 14.5 (1.75) | 14.8 (1.73) | 0.24 | 1.09 (0.94, 1.27), p = 0.24 | 1.09 (0.92, 1.3), p = 0.33 | 1.07 (0.89, 1.28), p = 0.5 | 1.07 (0.89, 1.28), p = 0.5 | 1.08 (0.91, 1.29), p = 0.37 | ||

| RDW Day 7, mean (SD) | 14.9 (1.86) | 15.1 (1.59) | 0.51 | 1.07 (0.88, 1.3), p = 0.50 | 1.04 (0.83, 1.31), p = 0.74 | 1.02 (0.8, 1.29), p = 0.89 | 1.03 (0.81, 1.31), p = 0.83 | 1.03 (0.81, 1.3), p = 0.84 | ||

| RDW at ICU discharge, mean (SD) | 14.3 (1.76) | 15.1 (2.14) | < 0.001 | 1.26 (1.16, 1.38), p < 0.001 | 1.19 (1.07, 1.32), p = 0.001 | 1.11 (0.99, 1.25), p = 0.07 | 1.11 (0.99, 1.24), p = 0.09 | 1.12 (1, 1.25), p = 0.04 | ||

| OHCA, mean (SD) | 11 (19) | 33 (17) | < 0.001 | 1.08 (1.07, 1.09), p < 0.001 | 1.07 (1.06, 1.09), p < 0.001 | n.a | n.a | n.a | 0.81 | 0.81, p = 0.36 |

| CAHP, mean (SD) | 135 (42) | 190 (40) | < 0.001 | 1.03 (1.03, 1.04), p < 0.001 | 1.03 (1.03, 1.04), p < 0.001 | 0.83 | 0.83, p = 0.58 | |||

| PROLOGUE, mean (SD) | 236 (102) | 350 (101) | < 0.001 | 1.01 (1.01, 1.01), p < 0.001 | 1.01 (1.01, 1.01), p < 0.001 | 0.78 | 0.79, p = 0.31 | |||

AUC area under curve, CAHP cardiac arrest hospital prognosis score, CI confidence interval, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CPC cerebral performance category scale, ICU intensive care unit; n number, n.a. not available, OHCA out-of-hospital cardiac arrest score, OR odds ratio, PROLOGUE prognostication using logistic regression model for unselected adult cardiac arrest patients in the early stages, RDW red cell distribution width

*Adjusted for age, gender, hematocrit, comorbidities.

Figure 1.

The dynamic of mean RDW values during ICU stay, stratified by the primary outcome (CPC). CPC Cerebral performance category scale; RDW Red blood cell distribution width.

All three risk scores were associated with poor neurological outcome with AUCs for the OHCA-, CAHP- and PROLOGUE score of 0.82, 0.83 and 0.75. When adding the maximum RDW values to these scores, the prognostic performance of all scores slightly improved: OHCA score from AUC 0.82 to 0.83; p = 0.047; CAHP score from AUC 0.83 to 0.84; p = 0.03 and PROLOGUE score from AUC 0.75 to 0.77; p = 0.02.

Association of RDW with mortality at hospital discharge

Regarding secondary outcome, higher mean RDW values were independently associated with mortality at hospital discharge (mean ± SD 15.1 ± 2.04 vs 14.5 ± 1.87, adjusted OR 1.1, 95% CI 1.01–1.21; p = 0.04). Further, the third (RDW values 14.3–15.5) and fourth (RDW values < 15.5) quartile were independently associated with mortality at hospital discharge (adjusted OR 1.97, 95% CI 1.25–3.1; p = 0.003 and OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.12–2.94; p = 0.02).

The maximum RDW values did not improve the prognostic performance of the OHCA-, CAHP- and PROLOGUE score regarding mortality.

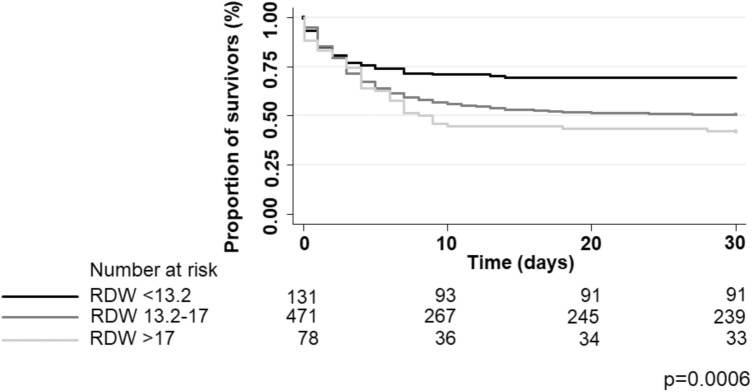

A Kaplan–Meier-curve for 30-day all-cause-mortality stratified by the two different optimal cut-offs of mean maximum RDW values (< 13.2 and > 17) calculated by Youden Index is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier-curve for 30-day all-cause mortality stratified according to low (< 13.2), moderate (13.2–17) and high (> 17) RDW values. RDW Red blood cell distribution width.

RDW dynamic over time

The mean RDW values increased over time, with the highest values observed at day 7. Overall a significant difference between day 0 and day 7 (14.1 vs. 14.9, mean difference 0.8, 95% CI 0.61–1.04, p < 0.001) was observed. This could also be observed when stratifying the increase of RDW values over time according to the primary outcome: Day 0 vs. day 7 in patients with poor neurological outcome (14.2 vs. 15.2, mean difference 1.0, 95% CI 0.74–1.33, p < 0.001) and day 0 vs. day 7 in patients with good neurological outcome (14.0 vs. 14.7, mean difference 0.7, 95% CI 0.32–0.94, p = 0.001), respectively.

Sensitivity and specificity

We also assessed the sensitivity and specificity of maximum RDW values at different cut-offs (Table 3). For poor neurological outcome, the optimal cut-off at a maximum RDW value (Youden Index) of 13.2 had a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 23.5%. A cut-off at a maximum RDW value of 16.6 resulted in a sensitivity of 20.6% and a specificity of 89.8%.

Table 3.

Sensitivity and specificity.

| Poor neurological outcome: CPC 3–5 | Mortality at hospital discharge | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDW Max* cut-off 13.2 | RDW Max* cut-off 16.6 | RDW Max* cut-off 13.2 | RDW Max* cut-off 17 |

||

| Prevalence | Pr(A) | 54.00% | 54.00% | 43.00% | 43.00% |

| Sensitivity | Pr(+ A) | 91.00% | 20.60% | 91.10% | 15.20% |

| Specificity | Pr(-N) | 23.50% | 89.80% | 20.80% | 90.00% |

| Likelihood ratio ( +) | Pr(+ A)/Pr(+ N) | 1.19 | 2.01 | 1.15 | 1.52 |

| Likelihood ratio (-) | Pr(-A)/Pr(-N) | 0.38 | 0.88 | 0.43 | 0.94 |

| Odds ratio | LR( +)/LR(-) | 3.12 | 2.28 | 2.67 | 1.62 |

| Positive predictive value | Pr(A +) | 58.30% | 70.30% | 46.50% | 53.50% |

| Negative predictive value | Pr(N-) | 69.10% | 49.10% | 75.50% | 58.40% |

CPC cerebral performance category scale, RDW red cell distribution width.

*RDW Max indicates the mean of each patients maximum RDW value.

For mortality at hospital discharge, a cut-off at a maximum RDW value of 13.2 had a sensitivity of 91.1% and a specificity of 20.8%. A cut-off at a maximum RDW value of 17 had a sensitivity and specificity of 15.2% and 90%.

The proposed cut-offs by Cheng et al.41 had a sensitivity of 52% and specificity of 70% for poor neurological outcome, and a sensitivity of 30.8% and specificity of 79.2% for mortality (Supplementary Table S1).

Discussion

In our cohort of cardiac arrest patients, RDW is an independent predictor of poor neurological outcome at hospital discharge, with mean RDW values on day three showing the strongest association. These findings persisted when adjusting the results for known RDW confounders such as age, gender, hematocrit, and comorbidities13, 38–40. Also, a higher mean RDW value was found to be an independent predictor of mortality at hospital discharge.

As an inexpensive, routinely available blood marker, RDW might be a promising prognostic factor to support clinical decision-making. It could help to stewardship the management in a early course after cardiac arrest, especially if patient are unconscious and thus difficult to be neurologically assessed. Also, when integrated into established clinical prediction models such as OHCA-, CAHP- or PROLOGUE score, it might improve their predictive value.

Several studies found RDW to be an independent risk factor for death in acute coronary syndrome, lung cancer, acute pulmonary embolism, and unselected ICU patients13, 14, 16–20. Many factors are associated with an increase in RDW, such as age, sex, anemia, inflammatory markers (e.g. C-reactive protein [CRP]), metabolic syndromes, or blood transfusion13, 38, 39, 42–44. As cardiac arrest patients usually face a relevant phase of hypoxemia, one possible explanation for elevated RDW levels are hypoxia-induced elevated erythropoietin levels which also occur in patients with other acute conditions such as pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, cardiac disease or sepsis45. This might also explain the higher mean RDW values in patients with non-observed cardiac arrest and a consecutively longer no-flow time. Accordingly, these criteria are part of modern risk prediction scores for neurological outcome after cardiac arrest9.

RDW was also elevated in patients with chronic kidney disease38 and might be an indication for an underlying inflammatory state38, 43, 46. However, it is unclear if in our cohort the elevated RDW is an acute response to the cardiac arrest, to pre-existing comorbidities or to ICU treatment.

Our results are mostly in line with previous studies investigating the prognostic performance of RDW in cardiac arrest patients where RDW was found to be an independent predictor of poor neurological outcome and mortality at hospital discharge or 30-days after hospital discharge21, 41, 47. Differences in study setting, study population and severity of illness may cause variations in results. Generally, two studies collected blood samples immediately after admission to the emergency department whereas we only included patients who survived until ICU admission21, 47. Woo et al. reported much more patients with poor neurological outcome (70.6%), due to cultural and legal differences, as in Korea withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy was not allowed until 201810, 48. Also, patients in their cohort received less bystander CPR (54.1%) compared to our cohort (71.2%) and the no-flow time as a marker for hypoxemic burden was not reported21. Also, the pre-existing cut-offs from the KoCARC-study were not adequate for our cohort which may be attributed to different analytic techniques and the resulting lack of harmonization12, 15. Consistent with previous studies, we found RDW values to be independent predictors of 30-day mortality21, 47. However, in our cohort the prognostic value regarding mortality was not as strong. This may be due to the previously mentioned differences in study setting and population.

Importantly, there was a slight improvement of prognostic value of existing cardiac arrest scoring systems (OHCA-, CAHP- and PROLOGUE score) by adding RDW. Thus, RDW brings a benefit as a marker of no-flow time, since this clinical parameter is often missing or unprecise31. Previous studies have found RDW to be elevated with age49, 50. Also, in our study, RDW was associated with increasing age, however, RDW remained an independent predictor of poor neurological outcome even after adjusting the statistical model for age.

In our cohort, we found an increase in RDW values during the ICU stay. Only few studies have looked at the progression of RDW over time after an initial event. In an observational study, looking at the relationship between RDW and long-term neurological outcome after cardiac arrest, RDW did not increase over time, however, the sampling time was restricted to the first 72 h after cardiac arrest, which prohibits conclusions for longer than 72 h post-cardiac arrest51. In a cohort of patients with post-hypoxia (e.g., heart failure, pneumonia, atelectasis, pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, and sepsis), RDW reached its maximum level within one month after the index event and remained elevated for three months in total45.

This study has several strengths. First, the presented data is the result of a large and well-established cardiac arrest cohort over several years. Second, the analysis and reporting followed the TRIPOD statement. Third, the score values were calculated by the study team and were not communicated to the treating physicians, which reduces the concern of self-fulfilling prophecies, a common issue in unblinded prognostic research in cardiac arrest patients52–54.

This study also has several limitations. First, our setting of an observational, single-center study limits the transfer to cohorts from other regions or countries. Second, we could not assess causes for elevated RDW and / or death, so there may be nondependent causes. Third, the lack of harmonization in RDW measurement technique may influence the different cut-offs and render our results difficult to compare to other studies15. Finally, we did not collect any data about blood transfusions or nutritional state which could also increase RDW values38, 44.

Conclusion

In our prospective cohort of unselected adult cardiac arrest patients, RDW was an independent predictor of poor neurological outcome at hospital discharge. Therefore, RDW could act as an inexpensive and easily available prognostic marker in cardiac arrest patients. Further studies should focus on the prognostic value of RDW for neurological long-term outcome.

Supplementary Information

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under the curve

- CAHP

Cardiac arrest hospital prognosis

- CI

Confidence interval

- COMMUNICATE

Communication in out-of hospital cardiac arrest events

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CPC

Cerebral performance category

- CPR

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- EEG

Electroencephalogram

- EKNZ

Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz (Ethics committee of north-western and central Switzerland)

- GCS

Glasgow coma scale

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- IHCA

In-hospital cardiac arrest

- KoCARC

Korean Cardiac Arrest Research Consortium

- MCV

Mean corpuscular volume

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- OHCA

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

- OR

Odds ratio

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- PROLOGUE

Prognostication using logistic regression model for unselected adult cardiac arrest patients in the early stages

- PROPHETIC

Prognostication of outcome in patients with out-of hospital cardiac arrest hospitalized in intensive care

- RDW

Red blood cell distribution width

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic curve

- ROSC

Return of spontaneous circulation

- SCA

Sudden cardiac arrest

- SD

Standard deviation

- TRIPOD

Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis

Author contributions

T.U., S.H. and S.A. were the main contributors regarding conceptualization, methodology, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, as well as writing, editing and visualizing the manuscript. S.H. was the supervisor and administrator of the project. C.B., S.G. and A.A. made substantial contributions to the data acquisition and to the editing and revision of the manuscript. K.T., R.S., H.P. and S.M. provided resources for the data acquisition and revised the manuscript substantially. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Sabina Hunziker and her research team were supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) and the Swiss Society of General Internal Medicine (SSGIM) during the conduct of the study. Grant References 10001C_192850/1 and 10531C_182422 and the Gottfried Julia Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation (8472/HEG-DSV). Dr. Amacher received a research grant from the Mach-Gaensslen Foundation Switzerland.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Tabita Urben and Simon A. Amacher

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-41984-8.

References

- 1.Gräsner J-T, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines 2021: epidemiology of cardiac arrest in Europe. Resuscitation. 2021;161:61–79. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsao CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2023 Update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;147:e93–e621. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yaow CYL, et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder after cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2022;170:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincent A, et al. Post-intensive care syndrome in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients: A prospective observational cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0276011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0276011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geocadin RG, et al. Standards for studies of neurological prognostication in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;140:e517–e542. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garza EG, Rumbak MJ. Prediction of mortality from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is key to decrease morbidity and mortality from cardiac, neurologic, and other major organ damage*. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:503. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000000829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adrie C, et al. Predicting survival with good neurological recovery at hospital admission after successful resuscitation of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: the OHCA score. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2840–2845. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maupain C, et al. The CAHP (Cardiac Arrest Hospital Prognosis) score: A tool for risk stratification after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3222–3228. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amacher SA, et al. Predicting neurological outcome in adult patients with cardiac arrest: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prediction model performance. Crit. Care. 2022;26:382. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-04263-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bae DH, et al. PROLOGUE (PROgnostication using LOGistic regression model for Unselected adult cardiac arrest patients in the Early stages): Development and validation of a scoring system for early prognostication in unselected adult cardiac arrest patients. Resuscitation. 2021;159:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isenschmid C, et al. Routine blood markers from different biological pathways improve early risk stratification in cardiac arrest patients: Results from the prospective, observational COMMUNICATE study. Resuscitation. 2018;130:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lippi G, Pavesi F, Bardi M, Pipitone S. Lack of harmonization of red blood cell distribution width (RDW): Evaluation of four hematological analyzers. Clin Biochem. 2014;47:1100–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fava C, Cattazzo F, Hu ZD, Lippi G, Montagnana M. The role of red blood cell distribution width (RDW) in cardiovascular risk assessment: Useful or hype? Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:581. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.09.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salvagno GL, Sanchis-Gomar F, Picanza A, Lippi G. Red blood cell distribution width: A simple parameter with multiple clinical applications. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2015;52:86–105. doi: 10.3109/10408363.2014.992064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lippi, G., Plebani, M. Red blood cell distribution width (RDW) and human pathology. One size fits all. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med.52, 1247–1249 (2014). 10.1515/cclm-2014-0585 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Nabais S, et al. Association between red blood cell distribution width and outcomes at six months in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Rev Port Cardiol. 2009;28:905–924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zorlu A, et al. Usefulness of admission red cell distribution width as a predictor of early mortality in patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koma Y, et al. Increased red blood cell distribution width associates with cancer stage and prognosis in patients with lung cancer. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim CH, et al. An increase in red blood cell distribution width from baseline predicts mortality in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. Crit Care. 2013;17:R282. doi: 10.1186/cc13145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunziker S, Celi LA, Lee J, Howell MD. Red cell distribution width improves the simplified acute physiology score for risk prediction in unselected critically ill patients. Crit. Care. 2012;16:R89. doi: 10.1186/cc11351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woo SH, Lee WJ, Kim DH, Cho Y, Cho GC. Initial red cell distribution width as a predictor of poor neurological outcomes in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survivors in a prospective, multicenter observational study (the KoCARC study) Sci Rep. 2020;10:17549. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74842-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herzog, N. et al. Association of Taurine with in-hospital mortality in patients after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: Results from the prospective, observational COMMUNICATE study. J Clin Med9 (2020). 10.3390/jcm9051405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Keller, A. et al. Arginine and arginine/ADMA ratio predict 90-day mortality in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest-results from the prospective, observational COMMUNICATE Trial. J. Clin. Med.9 (2020). doi:10.3390/jcm9123815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Boerlin, A. et al. Low plasma sphingomyelin levels show a weak association with poor neurological outcome in cardiac arrest patients: Results from the prospective, observational COMMUNICATE Trial. J Clin Med9 (2020). 10.3390/jcm9040897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Loretz N, et al. Activation of the kynurenine pathway predicts mortality and neurological outcome in cardiac arrest patients: A validation study. J Crit Care. 2022;67:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2021.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isenschmid C, et al. Performance of clinical risk scores to predict mortality and neurological outcome in cardiac arrest patients. Resuscitation. 2019;136:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metzger K, et al. Depression and anxiety in relatives of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients: Results of a prospective observational study. J Crit Care. 2019;51:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2019.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hochstrasser SR, et al. Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) predicts short- and long-term mortality and poor neurological outcome in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;59:393–402. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Widmer M, et al. Association of acyl carnitines and mortality in out-of-hospital-cardiac-arrest patients: Results of a prospective observational study. J Crit Care. 2020;58:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luescher T, et al. Neuron-specific enolase (NSE) improves clinical risk scores for prediction of neurological outcome and death in cardiac arrest patients: Results from a prospective trial. Resuscitation. 2019;142:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blatter R, et al. External validation of the PROLOGUE score to predict neurological outcome in adult patients after cardiac arrest: A prospective cohort study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2023;31:16. doi: 10.1186/s13049-023-01081-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD Statement. Ann. Internal Med.162, 55–63 (2015). 10.7326/m14-0697%m25560714 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.TRIPOD: A New Reporting Baseline for Developing and Interpreting Prediction Models. Annals of Internal Medicine162, 73–74 (2015). 10.7326/m14-2423%m25560717 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): Explanation and Elaboration. Ann. Internal Med.162, W1–W73 (2015). doi:10.7326/m14-0698%m25560730 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Nolan JP, et al. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine guidelines 2021: Post-resuscitation care. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:369–421. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06368-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nolan JP, et al. European resuscitation council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine 2015 guidelines for post-resuscitation care. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:2039–2056. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet. 1975;1:480–484. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92830-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Förhécz Z, et al. Red cell distribution width in heart failure: Prediction of clinical events and relationship with markers of ineffective erythropoiesis, inflammation, renal function, and nutritional state. Am Heart J. 2009;158:659–666. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weiss G, Goodnough LT. Anemia of chronic disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:1011–1023. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lippi G, Turcato G, Cervellin G, Sanchis-Gomar F. Red blood cell distribution width in heart failure: A narrative review. World J Cardiol. 2018;10:6–14. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v10.i2.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng, Y. et al. Associations between red cell distribution width and outcomes of adults with in-hospital cardiac arrest: A retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore)101, e28750 (2022). 10.1097/md.0000000000028750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Laufer Perl, M. et al. High red blood cell distribution width is associated with the metabolic syndrome. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc63, 35–43 (2015). 10.3233/ch-151978 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Lippi, G. et al. Relation between red blood cell distribution width and inflammatory biomarkers in a large cohort of unselected outpatients. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med.133, 628–632 (2009). 10.5858/133.4.628 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Spadaro, S. et al. The effects of blood transfusion on red blood cell distribution width in critically ill patients: a pilot study. Transfusion58, 1863–1869 (2018). 10.1111/trf.14759 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Yčas JW, Horrow JC, Horne BD. Persistent increase in red cell size distribution width after acute diseases: A biomarker of hypoxemia? Clin. Chim. Acta. 2015;448:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tonelli M, et al. Relation between red blood cell distribution width and cardiovascular event rate in people with coronary disease. Circulation. 2008;117:163–168. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.727545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim J, et al. Red blood cell distribution width as an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in out of hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2012;83:1248–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryu JY, et al. Physicians’ attitude toward the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment: A comparison between Korea, Japan, and China. Death Stud. 2016;40:630–637. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2016.1203375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alis, R., Fuster, O., Rivera, L., Romagnoli, M. & Vaya, A. Influence of age and gender on red blood cell distribution width. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. (CCLM)53, e25–e28 (2015). 10.1515/cclm-2014-0756 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Hoffmann, J. J., Nabbe, K. C. & van den Broek, N. M. Effect of age and gender on reference intervals of red blood cell distribution width (RDW) and mean red cell volume (MCV). Clin Chem Lab Med53, 2015–2019 (2015). 10.1515/cclm-2015-0155 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Fontana, V. et al. Can red blood cell distribution width predict outcome after cardiac arrest? Minerva Anestesiol84, 693–702 (2018). 10.23736/s0375-9393.17.12102-4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Izzy S, Compton R, Carandang R, Hall W, Muehlschlegel S. Self-Fulfilling prophecies through withdrawal of care: Do they exist in traumatic brain injury, too? Neurocrit Care. 2013;19:347–363. doi: 10.1007/s12028-013-9925-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Geocadin RG, Peberdy MA, Lazar RM. Poor survival after cardiac arrest resuscitation: A self-fulfilling prophecy or biologic destiny?*. Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:979–980. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182410146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mertens M, King OC, van Putten M, Boenink M. Can we learn from hidden mistakes? Self-fulfilling prophecy and responsible neuroprognostic innovation. J Med Ethics. 2022;48:922–928. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-106636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.