Abstract

The significance of youth suicide as a public health concern is underscored by the fact that it is the second leading cause of death for youth globally. While suicide rates for White groups have declined, there has been a precipitous rise in suicide deaths and suicide-related phenomena in Black youth; rates remain high among Native American/Indigenous youth. Despite these alarming trends, there are very few culturally tailored suicide risk assessment measures or procedures for youth from communities of color. This paper attempts to address this gap in the literature by examining the cultural relevancy of currently widely used suicide risk assessment instruments, research on suicide risk factors, and approaches to risk assessment for youth from communities of color. It also notes that researchers and clinicians should consider other, nontraditional but important factors in suicide risk assessment, including stigma, acculturation, and racial socialization, as well as environmental factors like health care infrastructure and exposure to racism and community violence. The paper concludes with recommendations for factors that should be considered in suicide risk assessment for youth from communities of color.

Keywords: mental health disparities, suicide risk, risk assessment, cultural responsiveness

Suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs) are a serious public health crisis. Worldwide, suicide is the second leading cause of death among individuals ages 10–24. While rates of other public health crises have declined over recent decades, rates of suicide have remained alarmingly high and have increased disproportionately among groups of color in the United State (Martínez-Alés et al., 2021). From 1991 through 2017, suicide death rates significantly increased among Black youth (CBC, 2019) and Latine1 females (Silva & Van Orden, 2018); they remain highest among Native American/Indigenous youth (Curtin & Hedegaard, 2019). Indeed, there has been a disproportionate rise in suicide deaths among youth of color in this age range over the past two decades (Martínez-Alés et al., 2021).

The term “suicide,” often used synonymously with “suicide death,” involves intentional self-injurious behavior that results in a fatality (Silverman et al., 2007). Suicidal ideation refers to having active or passive thoughts about killing oneself. A suicide attempt is often characterized as self-injurious but nonlethal behavior that has some degree of intent to end one’s life. This paper refers to these terms collectively as STBs.

More youth experience STBs than suicide deaths (Ivey-Stephenson et al., 2020). Rates of STBs differ across ethnoracial minoritized groups in the United States. Recent data from a nationally representative sample suggest that 18.8% of United States high school students reported having experienced suicidal ideation in the previous year, 15.7% having made a suicide plan, and 8.9% having made a suicide attempt (Ivey-Stephenson et al., 2020). When these data are broken down across non-Latine Black, Latine, and non-Latine White youth, a concerning picture arises for Black and Latine youth, particularly girls. Black non-Latine youth reported a higher rate of suicide attempts (11.8%) than Latine (8.9%) and White non-Latine youth (7.9%). The suicide attempt rate was highest among Black non-Latine girls (15.2%). Latine females reported the next highest suicide attempt rate at 11.9%, compared to 9.4% for White non-Latine females (Ivey-Stephenson et al., 2020). Data show that 25.5% of Indigenous/Native American youth, 7.7% of Asian youth, and 12.9% of youth with multiple races reported a suicide attempt in the past year (WISQARS, 2021).

One place to begin addressing these increasing disparities is examining how STBs are assessed in racially and ethnically minoritized youth. The first part of this manuscript describes the current state of assessment tools and techniques available for youth of color. The second part describes considerations for culturally responsive assessment for youth of color in the United States—factors that may not be amenable to formal measurement instruments. Throughout this manuscript, the term “youth of color” comprises youth in Black, Asian, Latine, Native American/Indigenous, and multicultural communities. The authors acknowledge that much of the literature is underdeveloped and collapses across the rich diversity within ethnoracial groups (e.g., Black youth, Latine youth). Inherent to this literature is the risk that the current choice of terms may not stand up to future scholarship in this area.

Part 1: Existing Suicide Assessment Instruments and Approaches to Risk Assessment Adaptations of Current Suicide Assessment Instruments

Overall, there is limited research available regarding the effectiveness of evidence-based suicide assessment instruments used with youth of color in the United States. Very little work has been conducted to formally validate existing evidence-based assessment instruments in youth of color. Table 1 outlines some instruments that have not been specifically culturally adapted but have been used in samples with youth of color. Although there is some evidence to suggest validity and reliability in widely used suicide risk assessment tools, many remain to be empirically tested in youth of color; at the time of writing, no tool had been developed specifically for use with this population. Moreover, establishing reliability and validity of these assessment tools within samples of youth of color does not provide information regarding whether assessment tools function equally across ethnoracial groups.

Table 1.

Suicide assessment measures and strength of evidence for use with youth of color.

| Year | Author | Scale Name | Suicide Outcome | Sample Size, Age, Race, Recruitment | Psychometric Findings | YOC Rating a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening Instrument | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 2022 | Horowitz et al. | Ask Suicide Screening Questionnaires | SI, SB | 1,083, ages 10–21, 30.5% non-Hispanic Black, pediatric medical patients | SN, SP | 2 |

| 2004 | Shaffer et al. | Columbia Suicide Screen | SI, SB | 1,729, ages 11–19, 56% White, school | SN, SP, PV, TR, IC | 2 |

|

| ||||||

| Clinical Interview | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 2011 | Posner et al. | Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale | SI, SB | Sample 1: 124, ages 12–18, 67% White, outpatient; Sample 2: 317, ages 11–17, 76% White, outpatient | SN, SP, PV, IC, CV, DVV | 1 |

| 2007 | Nock et al. | Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview | SI, SP, SB | 94, ages 12–19, 73% White, clinical and community | TR, CV, IR, II | 1 |

| 2021 | Gratch et al. | Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview—Revised | SI, SP, SB | 206, ages 12–19, 33% White, community | CV, IR, II | 2 |

| 1990 | Reynolds | Suicidal Behaviors Interview | SI, SB | 352, ages 12–19, 67% White, school | IC, IR, CN, CSV | 1 |

| 1979 | Pfeffer et al. | Child Suicide Potential Scales | SI, SB | 58, ages 6–12, 49% Latine, clinical | IR, IC | 2 |

|

| ||||||

| Self-Report Survey | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 1993 | Steer et al. | Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation | SI, SB | 108, ages 12–17, 66% White, inpatient | CV, CNV, DSV | 1 |

| 2002 | Joiner et al. | Depressive Symptom Inventory—Suicidality Subscale | SI | 2,851, ages 15–24, 90% born in Australia, outpatient | IC, CNV, DSV | 1 |

| 2002 | Osman et al. | Positive and Negative Suicide Ideation Inventory | SI | 195, ages 14–17, 84% White, inpatient | TR, IC, CV, CSV, DSV | 1 |

| 2003 | Osman et al. | Positive and Negative Suicide Ideation Inventory | SI | 217 school, 30 inpatient, ages 14–19, 79% White, school and inpatient | SN, SP, CV, IC, DSV | 1 |

| 2010 | Muehlenkamp et al. | Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire | SI, SP, SB | 1,386, mean age 15.5, 43% White, school | IC, CV, DSV, MI | 2 |

| 2001 | Osman et al. | Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire–Revised | SI, SB | Sample 1: 110, ages 14–17, inpatient, 80% White; Sample 2: 148, ages 14–18, 87% White, school | IC, CV, DSV | 1 |

| 1999 | Reynolds & Mazza | Suicide Ideation Questionnaire | SI | 91, ages 11–15, 91% Black, school | TR, IC, DSV, CNV | 2 |

| 1996 | Spirito et al. | Suicide Intent Scale | SI | 190, ages 12–17, 80% White, clinical | IC, CV, CNV | 1 |

| 2009 | Pettit et al. | Modified Scale for Suicide Ideation | SI, SB | 102, ages 13–17, 40% Latine, inpatient | IC, IR, CV, CNV | 2 |

|

| ||||||

| Self-Report Survey With Risk Factors | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 1993 | Tatman et al. | Suicide Probability Scale | SI | 217, ages 15–19, 27% White, school | IC, DSV | 2 |

Note. SI = suicidal ideation; SB = suicide attempts/behavior; SP = suicide plans; SN = sensitivity; SP = specificity; PV = predictive validity; CV = convergent validity; DVV = divergent validity; IR = interrater reliability; TR = test-retest reliability; II = inter-informant agreement; CN = content validity; IC = internal consistency; CSV = construct validity; DSV = discriminant validity; MI = measurement invariance; CNV = concurrent validity.

Strength of Support for use with YOC (youth of color): 1 = tested in majority White sample; 2 = tested in ethnoracially diverse sample (i.e., at least 40% of participants identified as being from a racial/ethnic minority background); 3 = culturally adapted and validated in youth of color (N/A because no measures fell into this category).

Because there are cultural differences in a person’s thinking, perceptions, and discussions about suicide, Chu et al. (2013) developed a suicide risk assessment tool that integrates culturally relevant risk and protective factors for suicide to supplement more traditional suicide assessment scales. The Cultural Assessment of Risk for Suicide (CARS) captures factors associated with suicide, such as cultural values on the acceptability of suicide (Cultural Sanctions); verbal and nonverbal expressions of suicidal thoughts or behavior (Idioms of Distress); social identity stressors, including discrimination (Minority Stress); and alienation or conflict (Social Discord). Providing comprehensive utility, the CARS is the only suicide assessment tool specifically developed to integrate cultural factors related to suicide risk and to evaluate the psychometric properties of the tool specifically with ethnoracial minoritized populations. While the CARS has initial promising support in adults, it has not been widely adopted in research applications or tested with adolescents.

Alternatively, some researchers have combined non–culturally formatted (less culturally explicit) items across multiple scales for use with youth of color to better capture suicide risk. For example, one study combined seven different scales to detect acute suicide risk and referral or intervention services among 221 eighth-grade youth in South Africa with low economic resources (Vawda et al., 2017). Specifically, the screening tool pooled across depressive symptoms, hopelessness, perceived stress, anger, mastery, self-esteem, and social support. In the final 12-item suicide screen, researchers observed a low sensitivity of 38% and accuracy of 80% (Vawda et al., 2017). Even with this approach, cultural influences on suicide risk are not directly measured in such assessment approaches.

Well-established community research collaborations were used to adapt the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ; Reynolds & Mazza, 1994) for assessment and intervention in a sample of 304 Native American/Indigenous youth and young adults (ages 10–24). After more than 2 years of collaboration, White Mountain Apache Tribal members and Johns Hopkins Center for American Indian Health Team members reviewed the SIQ and each item’s face validity to identify culturally irrelevant items. Some items on the SIQ were reworded slightly to be more literal. Modification of the SIQ also included deleting three items from the SIQ: Item 6 “thinking about death”), 8 (“writing a will”), and 9 (“telling people”) because they contributed to poor model fit. The SIQ item that asks about whether the individual has a “will” was flagged because “drafting wills is not a common practice” in this tribal community. Furthermore, spiritual beliefs are associated with tribal values; therefore, SIQ-JR Item 5 (“I thought about people dying”) may include idiomatic expression of spirituality and thus not perform as intended (Hill et al., 2020). These adaptations are critical to account for understanding suicide risk in communities that have differing cultural and language traditions surrounding death and suicide.

Different from traditional suicide risk assessments, computerized adaptive testing (CAT) (Gibbons et al., 2017) represents a paradigm shift from traditional assessment tools by beginning with a large “bank” of items and then adaptively administering the test based on the respondent’s ongoing answers. CAT shows great promise for assessing suicide risk among youth of color because the result is a statistically optimal set of items that maintain strong correlations with the entire bank of items with a high degree of sensitivity and specificity (Gibbons et al., 2017). This approach to suicide risk assessment may be particularly important for Black youth, whose suicidal ideation is often missed (Anderson et al., 2015), because it can detect risk factors (e.g., depression) that often emerge before suicidal ideation.

Risk Factors and Risk Assessments With Youth of Color

Suicide risk screening involves identifying youth who may be experiencing suicidal ideation or at risk of a suicide attempt. Risk assessment is a specific clinical skill set used to methodically assess imminent risk, which involves examining additional risk and protective factors. Risk factors for suicide increase the likelihood of suicidal ideation, attempts, or death. However, even with one or many risk factors, an individual may not be at imminent suicide risk. The paper next briefly describes how risk factors and risk assessments should take culture into account when assessing youth of color for suicide risk.

Risk Factors.

Risk factors increase the likelihood that a person will develop mental health challenges, maladaptive behaviors, or both (Rutter, 2006). In general, risk factors for suicide include being a victim or perpetrator of bullying or having a family history of suicide attempts or death, history of depression or other mental health challenges, trauma, impaired daily functioning, easy access to lethal means, and substance use (Borowsky et al., 2013; di Giacomo et al., 2018). There is considerable complexity in the relationship between risk factors for STBs. For example, research suggests that in general, children and adolescents who have been bullied are more likely to report STBs, but whether there is a direct causal relationship between bullying and STBs is unclear (Borowsky et al., 2013). Additionally, identifying as an individual from a sexual or gender minority background is associated with increased STB risk; however, there is nothing inherently causal about sexual or gender status and suicide risk. Rather, it is the environmental context in which youth exist that likely increases suicide risk (e.g., unsupportive home environment; (Meyer, 2003). Thus, risk factors must be considered with environmental context.

Very few studies have examined risk factors for STBs in youth of color. The research to date suggests that internalizing and externalizing behaviors, poor family support, and ethnoracial discrimination are risk factors for suicidal ideation and attempts among youth of color (Molock et al., 2006; O’Donnell et al., 2004). Even when risk factors are similar across ethnoracial groups, the mechanism for STBs may be different. For example, Joe et al. (2009) found that female sex, older age, and the presence of a mental disorder were risk factors in an ethnically diverse sample of Black adolescents, but the Black adolescents who attempted suicide were less likely to be diagnosed with a mental health disorder than those who did not attempt suicide. In a study of 518 youth and young adults ages 12–21, results suggested that among youth with a mood, anxiety, or substance-related diagnosis at baseline, race/ethnicity did not predict a suicide attempt at follow-up, but among those without a diagnosis, race/ethnicity was a significant predictor. Specifically, relative to White teens, Black and Asian teens had over 8 times higher odds of a suicide attempt within a 4- to 6-year follow-up period, adjusting for sex, lifetime suicide attempts, and exposure to suicide attempts (Kline et al., 2022).

Finally, regarding ethnoracial differences in antecedents of suicide deaths, a recent study using postmortem data with 3,996 United States youth found that White decedents had a higher rate of mental health problems than Black, Native American/Indigenous, Latine, and Asian Pacific Islander American decedents (Lee & Wong, 2020). Asian Pacific Islander American decedents had lower rates of mental health problems than White youth; were less likely than Latine youth to have disclosed suicidal intent; were more likely than Latine, Native American/Indigenous, and Black decedents to have left a suicide note; and were more likely than Black youth to have experienced interpersonal problems (Lee & Wong, 2020). These differences likely are the result of a complex interplay between cultural and contextual factors.

Risk Assessments.

Forms of risk assessments will vary across mental health settings, but typically, suicide risk screening involves assessment of current STBs in addition to risk factors for suicide attempts (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2001). Youth may be screened for suicide risk through a combination of self-report instruments and clinical interviews. Typically, youth and parents are interviewed separately and asked explicitly about suicidal ideation, plans, access to lethal means, non-suicidal self-injury, and any previous suicide attempts. In addition, clinicians usually assess research-established suicide risk factors (e.g., social support, social network, social resources), which may or may not apply well to youth of color. Dispositions of cases are typically made based on level of assessed risk (e.g., low, medium, high, imminent) and can range from recommendations for monitoring to creating a safety plan to stepping up to a higher level of care (e.g., intensive outpatient treatment or hospitalization). However, current recommendations and best practices are based largely on research conducted predominantly by White research groups with predominantly White samples and on guidelines that are developed without considering unique factors for youth of color.

How well do suicide risk assessments apply to youth of color?

Although depression anxiety, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder confer risk for suicide attempts among Black youth, research indicates that even Black youth without diagnosed mental health disorders may be at increased suicide risk (Joe et al., 2009; Sheftall et al., 2022). Additionally, risk assessments for youth of color must consider environmental context and expectations for the self and surrounding others. In geographically isolated or highly interconnected communities, social bonds may represent both a risk and protective factor, depending on context and on the needs of the individual child. For example, family support is considered a protective factor (Else et al., 2007), while family conflict is considered a risk factor (Consoli et al., 2013) for suicide.

Culturally responsive suicide risk assessment also needs to focus on untangling the complex relationship between culture and geographic location. Although the purpose of the study was to examine the measurement development process, in their work with Yup’ik communities in Alaska, Gonzalez and Trickett (2014) distinguish between population characteristics (i.e., the culture of a particular ethnic group) and community characteristics (i.e., the culture of the local setting). They describe differences in perspectives on suicide risk assessment across two Yup’ik communities, one that had experienced multiple suicide deaths and one that had no suicides in 25 years. Both communities had a shared cultural belief that asking directly about STBs and other risk behaviors was inappropriately intrusive and could be spiritually harmful. The community that had experienced suicide deaths directly was more open to suicide risk assessment, given that they perceived the problem as existing in their community. This difference demonstrates the importance of understanding local culture, history, and context, particularly for geographically distinct or separate communities.

Compounded with the sensitive nature of inquiring about suicide risk factors during assessment, assessors ought to know that youth of color may be inclined to provide socially desirable responses, be less forthcoming to formal assessment procedures, or both (Anderson et al., 2015). Additionally, discrepancies between parent and youth reports of suicidal ideation may be greater among racial families of color than among White families (Bell et al., 2021). Because acknowledging and inquiring about suicide can reduce suicidal ideation (Dazzi et al., 2014), clinicians may need to apply creativity and nuanced probing to modify or adapt suicide risk assessment to diverse linguistic, sociocultural, family, and economic influences.

In sum, current instruments, research on risk factors, and approaches to risk assessments are limited for youth of color. Current standard approaches are not identifying youth at risk. Even if youth of color are identified with screening instruments and current approaches, a given suicidal crisis was likely preceded by numerous cultural factors that are undetected by existing assessment instruments and approaches.

Part 2: Broader Issues in Culturally Responsive Risk Assessment

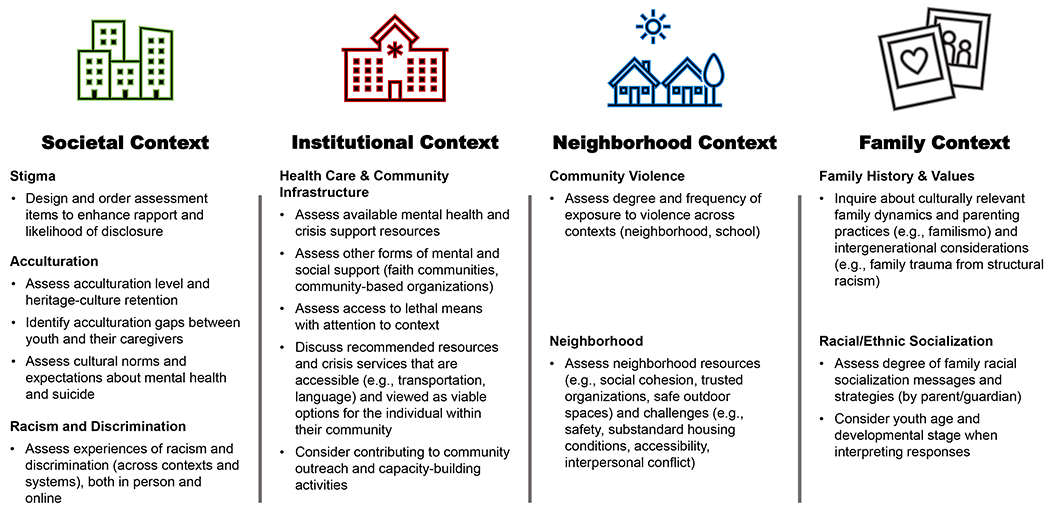

This section covers broader issues in culturally responsive risk assessment across societal, institutional, neighborhood, and family contexts. Although these areas are discussed separately, in reality, they are all interrelated. The presentation of these areas for consideration is not meant to prioritize any one over the other. Figure 1 offers potential ways to assess for each of the issues raised for each context.

Figure 1.

Recommended approach for a culturally responsive suicide risk assessment

Societal Context

Stigma.

Most suicide-related stigma research has not been conducted with youth and none specifically has focused on youth of color. However, research has demonstrated that youth who endorse a previous suicide attempt (or even thinking about a suicide attempt) frequently experience stigma and shame from family members, friends, and even health care professionals (Fortune et al., 2008). Moreover, research shows that the public holds many negative stereotypes of individuals who have made a previous suicide attempt. For example, in a large community survey, 40% of adult respondents viewed suicide as a “punitive, selfish, offensive, or a reckless act” (Batterham et al., 2013). Other studies show that individuals with a previous suicide attempt can be deeply ashamed of their history and tend to hide these behaviors from others. In a narrative review, feeling this stigma was associated with a higher risk for future suicide attempts (Carpiniello & Pinna, 2017). It is also important to recognize that stigma not only affects those individuals who previously attempted suicide, but also leads to prejudice and discrimination among those associated with these individuals, oftentimes parents, a concept referred to as courtesy stigma (Goffman, 1963). Both self-stigma and courtesy stigma have significant effects on a youth’s ability to self-disclose STBs and on many parents’ willingness to seek help (Carpiniello & Pinna, 2017). Thus, it is essential to structure the assessment process in a way that enhances rapport and minimizes stigma so that youth feel comfortable disclosing information necessary for a complete risk assessment.

Acculturation.

Contemporary models of acculturation have drawn on and extended Berry’s (1980) bidimensional conceptualization of acculturation, casting host-culture acquisition and heritage-culture retention as independent dimensions (Schwartz et al., 2010). Bidimensional models of acculturation depict a process by which individuals can acquire the culture of the host society without discarding their own cultural heritage (Berry, 2017).

Considerable diversity exists within ethnoracial minoritized communities. For instance, Latine populations differ by national origin, socioeconomic status, culture, dialect, history with the United States, skin tone, and ability to fit into mainstream United States society, as well as many other factors (Ennis et al., 2011). Although there are common factors among the experiences of Latine youth, it is critical to acknowledge these within-group differences in assessments of risk for suicide among Latine youth. Indeed, prior studies have found important differences in the prevalence of suicidal ideation and attempts across Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and other Latine adults living in the United States (Baca-Garcia et al., 2011), with Puerto Rican adults reporting the highest prevalence of lifetime suicidal ideation and attempts. Possible explanations for this elevated risk are that Puerto Ricans are more likely than other Latine subgroups to be United States born, have higher levels of acculturation (i.e., high United States cultural acquisition) (Alegría et al., 2008), and live below the poverty line (Ungemack & Guarnaccia, 1998; United States Census Bureau, 2020). Thus, suicide risk for youth of color may be best understood through the lens of intersectionality (Opara et al., 2020; Standley, 2022). Youth are defined not solely by their race, for instance, but also by their ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, age, nationality, ability, and immigration status. Indeed, the framework of intersectionality asserts that the impact of these multiple identities on a youth’s experiences of social inequality cannot be understood in isolation from each other (Bowleg, 2012; Crenshaw, 1989). Rather, these identities synergistically shape individuals’ life chances and experiences of the social world. The same is true for understanding how risk for suicide for youth of color may be the result of interactions among various intersecting identities.

The link between acculturation and STB risk is inconclusive, warranting careful assessment. Some studies find that high levels of acculturation (i.e., United States cultural acquisition) are related to higher risk for suicide attempts (Borges et al., 2009), whereas others find that less-acculturated adolescents (i.e., low United States cultural acquisition) are at higher risk for suicidal ideation (Olvera, 2001). Additionally, differences between adolescents and parents in levels of United States cultural acquisition, cultural heritage retention or acquisition, or both may lead to acculturation gaps, which have been linked to high levels of family conflict, communication problems, and negative outcomes in offspring (Zayas & Pilat, 2008). In fact, acculturation gaps in which adolescents have a higher United States cultural acquisition than their caregivers have been associated with self-harm and suicidal ideation in Latine adolescents (Gulbas et al., 2015). Other research has failed to replicate these findings and has even suggested the opposite (Ortin et al., 2017). Thus, possible acculturation gaps should be considered when assessing suicide risk among Latine adolescents (Ortin et al., 2017). Furthermore, acculturation may also affect access to care, and thus the assessment of suicide risk, as studies have shown that Latine young adults and adults with a low United States cultural acquisition are less likely to engage and remain in treatment (Burnett-Zeigler et al., 2018).

The term Asian American refers to a heterogeneous group in terms of demographic characteristics such as national origin, language, religion, socioeconomic status, and generation status. More than 20 countries are represented under the umbrella of Asian American. Mental health research in the United States has largely focused on the groups with the longest history in the United States, such as Chinese Americans, while overlooking both the diversity within Chinese American communities and the ways in which distinct cultural context, history, and forms of emotional expression are associated with each country of origin. Distinctions in each group’s experience in the United States with regard to discrimination, marginalization, and socioeconomic opportunity are also key to understanding the different stressors and life experiences of each group. For example, Asian Americans, often labeled the “model minority,” are perceived as a group to have a higher socioeconomic status than other United States ethnoracial groups; however, the number of Asian Americans who live at or below the United States poverty level varies from 7.5% among Filipino Americans to 35% among Burmese Americans (Budiman & Ruiz, 2021). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders also vary among different Asian subgroups, as well as by gender and level of acculturation (Sue et al., 2012).

Understanding the role of acculturation on STB risk in Asian American youth is challenging, because Asian youth often are not represented in national epidemiological surveys assessing STBs (e.g., Underwood et al., 2020). The Youth Risk Behavior Survey used to derive data on rates of STBs among Black, Latine, and White youth typically relegates Asian youth to an “other” category comprising Native American/Indigenous, Asian, Hawaii Native, Pacific Islander, and non-Latine multiracial youth (10.6% of the sample in 2019; Underwood et al., 2020). Some of the few studies that examined the role of acculturation on suicide attempts have mixed findings. Some researchers found that more-acculturated Asian American adolescents were more likely to be depressed (Park & Park, 2020), whereas others showed that less-acculturated Asian American youth were at greater risk for STBs (Lau et al., 2002).

Acculturation may affect risk assessment among Asian American youth in additional important ways. For example, disclosure of STBs can be affected by whether a given Asian American youth and family hold a collectivistic orientation, believe in emotional restraint, tend to express depression via somatic complaints, and de-emphasize internalizing (compared to externalizing) symptoms (Gudiño et al., 2008). Because broad cultural norms are not necessarily experienced by or adhered to in the same way by individuals, suicide risk assessment can include assessing relevant norms and expectations for the individual. A great example of one such item on the CARS states, “Suicide would bring shame to my family,” with responses ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree (Chu et al., 2013).

Racism and Discrimination.

Experience with racism and discrimination should be considered during STB risk assessment. When presenting a conceptual model of suicide risk among Black youth, Opara et al. (2020) identify that racism occurs in the immediate environment, the community, and as part of society. Studies have linked racism, discrimination, or both with STBs in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Argabright et al., 2022; Madubata et al., 2022). Racism that occurs via the internet and social media needs also to be considered for targeted risk assessment. For example, a study of Black and Latine adolescents showed that those exposed to videos of discrimination against those of their race/ethnicity were more likely to exhibit depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms (Tynes et al., 2019).

Institutional Context

Youth who live in settings with limited health and mental health infrastructure are in two types of resource-challenged communities in the United States: geographically isolated communities (e.g., Puerto Rico, tribal lands, rural communities) and communities where youth still experience limited health service access due to low socioeconomic status (e.g., urban communities with high population density and concentrated poverty).

Health Care and Community-Level Infrastructure.

Low economic resources, increased access to lethal means, and few health care professionals account for some of the suicide risks in resource limited settings (Rathod et al., 2017). Observed increases in suicide rates in metropolitan areas from 2005 to 2010 share some similarities with suicide rate increases in rural and small metropolitan counties in 2007–2008 (Ivey-Stephenson et al., 2017). Among both urban and rural populations, foreclosures, unemployment, and poor social support increase suicide risk. In the United States, use of a firearm was the most prevalent suicide method in urban and rural communities (Ivey-Stephenson et al., 2017).

Geographic location, access to mental health services, and the means by which services are provided are interwoven influences on suicide risk. In rural and geographically isolated communities, mental health services may not be available at all, may be inaccessible because of distance, may be avoided because of stigma, or may be perceived as an external imposition contrary to community values and preferences (Williams & Polaha, 2014). Strengthening assessment at organizational levels contributes to more efficient suicide prevention in limited resource settings. Larger institutions (e.g., churches, schools, government care agencies, community-based programs) may be positioned in resource-limited settings to broker referrals to mental health clinicians. Advantages to using nontraditional mental health resources include navigating medical systems, waitlists, reduced stigma, and affordability (Molock et al., 2008). Therefore, assessment of available resources for youth of color should broadly include systems that will buffer against the burden to provide individual clinical resources, including availability of trained (lay or professional) providers, train-the-trainer programs, and assessment tools to evaluate adequate use of all available resources.

Because there are a limited number of mental health professionals in resource-limited settings to perform individual youth STB risk assessments, providers may extend their roles to serve as assessment liaisons and administrators to suicide prevention programs. For example, Wu et al. (2021) considered that providers can collaborate with media professionals to assess suicide messaging on social media. Alternatively, mental health professionals can partner with community leaders or elders who will monitor development of youth suicide safety, suicide awareness, and problem-solving skills (Hobfoll et al., 2002). Many studies have incorporated capacity-building approaches in trainings (e.g., gatekeeper trainings) to identify STB risk among youth in resource-limited settings (e.g., Holliday et al., 2018).

Neighborhood Context

Community Violence.

Community violence can be experienced in multiple ways, including through being directly victimized, witnessing violence, hearing about violence, and living in violent neighborhoods (Guterman et al., 2000). Black and Latine youth are disproportionately exposed to community violence compared to White youth, and youth classified as “Other” or “Multiracial” may also have higher exposure (Browning et al., 2017; Crouch et al., 2020). Research supports that community violence exposure has direct effects on youth STBs (Castellvi et al., 2017). Community violence can also indirectly affect suicidal ideation and behaviors through internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Lambert et al., 2008). Furthermore, violence exposure that occurs in school, which is categorized as community violence, is also a major concern and risk for youth suicide. For example, a recent study showed that Asian American and Pacific Islander youth who experienced more STBs were more likely to have experienced school violence (Rajan et al., 2022). As a result of the prevalence and deleterious effect of community violence exposure on suicide risk, it is important to assess whether youth are exposed in their various contexts as well as the type and frequency of exposure.

Neighborhood.

In addition to specific exposures to community violence, neighborhood effects such as available resource capital (or lack thereof) should be incorporated into suicide assessments for youth of color. As a result of structural racism and policies in the United States, youth of color are more likely than White youth to live in neighborhoods that have lower resources and assets and higher levels of crime and violence (Woods-Jaeger et al., 2021; Zimmerman & Messner, 2013). On the other hand, racial discrimination may be particularly high for youth of color living in predominantly White neighborhoods (Stewart et al., 2009). A protective factor, neighborhood cohesion, including a sense of trust and social connection among community members, can mitigate the effects of violence exposure, economic disadvantage, and discrimination (Riina et al., 2013). As is true for other factors in this section, the relationship between neighborhoods and STB risk among youth of color is complex. Neighborhoods can be a source of both resilience and risk. Thus, careful assessment of the neighborhood context for youth of color will inform the determination of suicide risk.

Family Context

Family History and Values.

Family environment should be assessed for risk and protective factors for youth STBs. For youth of color, it is paramount to consider family and parenting through the lens of culture. For example, findings from a study of youth ages 6–12 years who were receiving inpatient psychiatric services revealed that authoritarian parenting style was associated with fewer suicide attempts among Black youth who reported more depressive symptoms; however, there was not a significant association among Black youth who reported fewer depressive symptoms or among White youth across depression severity. These findings suggest a particular protective influence of authoritarian parenting style for Black youth at risk, although this style has generally been viewed negatively (Greening et al., 2010).

Another example is the concept of familismo in Latine culture, in which the importance of family is valued over individualism. In a study of Latine adolescents, familismo was more likely in families characterized by high cohesion/low conflict, and this type of family was less likely to have adolescents who made a suicide attempt than were families with lower cohesion/higher conflict (Peña et al., 2011). A qualitative study by Gulbas et al. (2019) found that Latine youth who attempted suicide were more likely to experience sexual violence, not know about their mother’s history of gender-based violence, and not know why their parents set rules. Familismo as a cultural concept maps onto established risk and protective factors for youth suicide, demonstrating direct implications for culturally informative suicide assessment among Latine families.

A final example is gathering information about family trauma and experiences. A study of Indigenous adults demonstrated a cumulative STB risk on lifetime STBs from having one or two generations of family members living in residential centers (McQuaid et al., 2017). Although this study did not focus on youth, it provides clear evidence of intergenerational family trauma that resulted from structural racism, or racial biases in policies and practices across multiple re-enforcing systems (e.g., education, health care, economic) that concentrates social, political, and economic power and allocation of resources to dominant (e.g., White) populations. Thus, inquiring about cultural family topics and types of experiences is crucial for understanding a youth’s familial context. These examples highlight cultural family topics important for a culturally informed STB risk assessment.

Ethnoracial Socialization.

Ethnoracial socialization refers to specific verbal and nonverbal messages and strategies transmitted to youth for the development of values, beliefs, and knowledge regarding race/ethnicity, intergroup and intragroup interactions, and ethnoracial identity (Hughes et al., 2006). Families of color socialize their children in regard to race/ethnicity, and this socialization includes preparing their children to encounter and cope with racism and discrimination (e.g., Anderson & Stevenson, 2019). Research clearly demonstrates that ethnoracial socialization has a positive association with youth adjustment (Umaña-Taylor & Hill, 2020). A meta-analysis of parental ethnoracial socialization among children of color showed that socialization was positively associated with higher self-perceptions, greater interpersonal relationship quality, and more internalizing symptoms but not associated with externalizing symptoms (Wang et al., 2020). Although there is paucity of research directly measuring family ethnoracial socialization and youth STBs, it is an important construct in youth development and a potential protective factor. In assessing racial socialization of youth of color, researchers and clinicians should gather information about each parent, as well as family racial socialization messages and strategies, while also considering the youth’s age and developmental stage.

Part 3: Conclusions and Recommendations

In conclusion, suicide risk assessments for youth of color need to consider the social and community context and the meaning of these experiences and expectations for the self and surrounding others. A contextualized approach may be particularly important in these communities because risk assessment is often the first step in the treatment process. Culturally informed risk assessment can also be used to encourage the development of more culturally relevant treatment because the assessment process can help identify both risk and protective factors at the individual, family, and societal levels. Figure 1 illustrates major domains to assess for suicide risk across societal, institutional, neighborhood, and family contexts.

The following further recommendations stem from the paper.

Recommendation 1: To conduct a culturally informed investigation of reasons for living or dying, explore structural-level issues that might manifest in individual-level symptoms; do not rely exclusively on youth reports. For example, a Black bisexual youth who is being assessed for suicide risk might report overwhelming anxiety. A culturally unresponsive interviewer might interpret the youth’s anxiety as an individual factor instead of considering it a response to societally sanctioned heterosexism that is both racialized and discriminatory aggression. One of the pernicious features of structural oppression is that its effects are not always apparent to the individual. Although some youth might be able to recognize and articulate the role of structural oppression in their current suicidal crisis, some, particularly younger, youth may not.

Recommendation 2: Consider structural factors that may exacerbate or protect against suicide risk for youth of color. For example, school climate (e.g., tolerating white supremacy, affirming historically underrepresented groups in curriculum and policies, explicitly addressing homophobia and transphobia in anti-bullying policies), access to resources (e.g., affordable food and culturally relevant health care services), and acculturative stressors (e.g., deportation, language-based discrimination) may all influence a clinician’s assessment of the youth’s suicide risk given the specific context.

Recommendation 3: Consider what important cultural factors need to be included in the training of psychologists and other behavioral health providers so that these factors are part of the providers’ socioecological framework when assessing youth for suicide risk. Although a culturally responsive assessment may be perceived as taking an extensive time to conduct, there is no empirical evidence to support that perception. We are recommending a framework for suicide risk assessment that emphasizes considerations of multiple influences on mental health and wellbeing that is grounded in development and social-ecological perspectives. It is important that training for suicide risk assessment involves explaining how cultural issues (e.g., ethnicity, gender, sexual diversity, religion, disability, and socioeconomic status) and their intersectionality impact the selection and scoring of suicide screenings, interviews, and measures and interpretation of their findings. This also involves raising trainees’ awareness of the ways in which their own implicit biases influence the assessment process, as well as that their own social ecological frameworks, affect their perception of presenting problems, assessment results, and recommendations in ways that are incongruent with the client’s sociocultural reality.

Recommendation 4: Increase diversity of researchers and clinicians, as well as of research samples. Several factors have continued to limit progress in this area, including what Polanco-Roman and Miranda (2022) refer to as a “cycle of exclusion” that leads researchers who work with diverse populations to face “undue burdens across the research cycle” (p.1). These factors include barriers faced in obtaining representative samples, lack of available opportunities for funding and publication, and an undervaluing of research designs (e.g., qualitative methods) employed in community-based research.

Recommendation 5: Take what Sheftall and Miller (2021) termed “a ground zero approach” that moves away from an overreliance on quantitative methods and, instead, includes a mix of qualitative and quantitative approaches to better understand the unique set of circumstances that precede STBs among youth of color. This approach includes viewing STBs through a lens of justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion in the conceptualization and data collection for research and practice (Bath & Njoroge, 2021).

Recommendation 6: When developing suicide risk assessment tools, take steps to mitigate the historical harms caused by psychological assessments developed in the context of structural racism. Implementing this recommendation might include taking an intersectional lens that recognizes multiple parts of a youth’s identity that influence suicide risk (e.g., sexual + ethnoracial minoritized identities). Additionally, it could include involving youth of color and their parents in developing suicide risk assessments, which will not change structural racism but will minimize its damage when a youth is in a suicidal crisis.

Public Significance:

Suicide rates are increasing in youth of color. Yet, the prevailing approach to assessment of suicide risk in youth comes from decades of research that has not prioritized culturally responsive approaches that consider unique risk and protective factors for youth of color. This manuscript outlines initial steps towards a culturally responsive suicide risk assessment.

Acknowledgements:

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by grants MH091873 (Miranda), R01MH112147-04S1 (Zullo), K23MH112841 (Alvarez), P50MH127511 (Boyd), K01MH116325 (Miller).

Footnotes

The authors use the term “Latine” in this paper to refer to individuals of Latin American and Caribbean descent residing in the United States. There is not one agreed-upon term to refer to individuals of Latin American and Caribbean descent. With “Latine,” the authors have sought to be deliberately inclusive of all gender identities and to reflect a pronunciation more familiar to speakers of Spanish.

Contributor Information

Sherry D. Molock, The George Washington University.

Rhonda Boyd, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Kiara Alvarez, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Christine Cha, Teachers College, Columbia University.

Ellen-ge Denton, College of Staten Island, City University of New York.

Catherine R. Glenn, Old Dominion University; Virginia Consortium Program in Clinical Psychology.

Colleen C. Katz, Hunter College, City University of New York.

Anna S. Mueller, Indiana University.

Alan Meca, The University of Texas at San Antonio

Jocelyn I. Meza, University of California Los Angeles.

Regina Miranda, Hunter College and The Graduate Center, City University of New York

Ana Ortin-Peralta, Yeshiva University.

Lillian Polanco-Roman, The New School.

Jonathan B. Singer, Loyola University Chicago.

Lucas Zullo, University of California Los Angeles.

Adam Bryant Miller, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; RTI International.

References

- Alegría M, Canino G, Shrout PE, Woo M, Duan N, Vila D, Torres M, Chen C-N, & Meng X-L (2008). Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant U.S. Latino groups. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(3), 359–369. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. (2001). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behavior. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(7 Suppl), 24S–51S. 10.1097/00004583-200107001-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LM, Lowry LS, & Wuensch KL (2015). Racial Differences in Adolescents’ Answering Questions About Suicide. Death Studies, 39(10), 600–604. 10.1080/07481187.2015.1047058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, & Stevenson HC (2019). RECASTing racial stress and trauma: Theorizing the healing potential of racial socialization in families. The American Psychologist, 74(1), 63–75. 10.1037/amp0000392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argabright ST, Visoki E, Moore TM, Ryan DT, DiDomenico GE, Njoroge WFM, Taylor JH, Guloksuz S, Gur RC, Gur RE, Benton TD, & Barzilay R (2022). Association Between Discrimination Stress and Suicidality in Preadolescent Children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 61(5), 686–697. 10.1016/jjaac.2021.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baca-Garcia E, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Keyes KM, Oquendo MA, Hasin DS, Grant BF, & Blanco C (2011). Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Hispanic subgroups in the United States: 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45(4), 512–518. 10.1016/jjpsychires.2010.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bath E, & Njoroge WFM (2021). Coloring Outside the Lines: Making Black and Brown Lives Matter in the Prevention of Youth Suicide. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(1), 17–21. 10.1016/jjaac.2020.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batterham PJ, Calear AL, & Christensen H (2013). Correlates of suicide stigma and suicide literacy in the community. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 43(4), 406–417. 10.1111/sltb.12026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell K-A, Gratch I, Ebo T, & Cha CB (2021). Examining Discrepant Reports of Adolescents’ Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors: A Focus on Racial and Ethnic Minority Families. Archives of Suicide Research, 1–15. 10.1080/13811118.2021.1925607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW (1980). Acculturation as varieties of adaptation. In Padilla AM (Ed.), Acculturation: Theory, models and some new findings (pp. 9–25). Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW (2017). Theories and models of acculturation. The Oxford Handbook of Acculturation and Health, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Breslau J, Su M, Miller M, Medina-Mora ME, & Aguilar-Gaxiola S (2009). Immigration and suicidal behavior among Mexicans and Mexican Americans. American Journal of Public Health, 99(4), 728–733. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.135160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky IW, Taliaferro LA, & McMorris BJ (2013). Suicidal thinking and behavior among youth involved in verbal and social bullying: Risk and protective factors. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(1 Suppl), S4–12. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.10.280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2012). The Problem With the Phrase Women and Minorities: Intersectionality—an Important Theoretical Framework for Public Health. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1267–1273. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Calder CA, Ford JL, Boettner B, Smith AL, & Haynie D (2017). Understanding Racial Differences in Exposure to Violent Areas: Integrating Survey, Smartphone, and Administrative Data Resources. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 669(1), 41–62. 10.1177/0002716216678167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budiman A, & Ruiz NG (2021). Key facts about Asian Americans, a diverse and growing population. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett-Zeigler I, Lee Y, & Bohnert KM (2018). Ethnic Identity, Acculturation, and 12-Month Psychiatric Service Utilization Among Black and Hispanic Adults in the U.S. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 45(1), 13–30. 10.1007/s11414-017-9557-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpiniello B, & Pinna F (2017). The Reciprocal Relationship between Suicidality and Stigma. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 35. 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellví P, Miranda-Mendizábal A, Parés-Badell O, Almenara J, Alonso I, Blasco MJ, Cebrià A, Gabilondo A, Gili M, Lagares C, Piqueras JA, Roca M, Rodríguez-Marín J, Rodríguez-Jimenez T, Soto-Sanz V, & Alonso J (2017). Exposure to violence, a risk for suicide in youths and young adults. A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 135(3), 195–211. 10.1111/acps.12679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caucus CB (2019). Ring the alarm: The crisis of Black youth suicide in America. [Google Scholar]

- Chu J, Floyd R, Diep H, Pardo S, Goldblum P, & Bongar B (2013). A tool for the culturally competent assessment of suicide: The Cultural Assessment of Risk for Suicide (CARS) measure. Psychological Assessment, 25(2), 424–434. 10.1037/a0031264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consoli A, Peyre H, Speranza M, Hassler C, Falissard B, Touchette E, Cohen D, Moro M-R, & Révah-Lévy A (2013). Suicidal behaviors in depressed adolescents: Role of perceived relationships in the family. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 7(1), 8. 10.1186/1753-2000-7-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch E, Radcliff E, Probst JC, Bennett KJ, & McKinney SH (2020). Rural-Urban Differences in Adverse Childhood Experiences Across a National Sample of Children. The Journal of Rural Health, 36(1), 55–64. 10.1111/jrh.12366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin SC, & Hedegaard H (2019). Suicide Rates for females and males by race/ethnicity: United States: 1999 and 2014 (pp. 1–6). NCHS Health E-Stat. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/suicide/rates_1999_2017.htm [Google Scholar]

- Dazzi T, Gribble R, Wessely S, & Fear NT (2014). Does asking about suicide and related behaviours induce suicidal ideation? What is the evidence? Psychological Medicine, 44(16), 3361–3363. 10.1017/S0033291714001299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Giacomo E, Krausz M, Colmegna F, Aspesi F, & Clerici M (2018). Estimating the Risk of Attempted Suicide Among Sexual Minority Youths: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(12), 1145–1152. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else IRN, Andrade NN, & Nahulu LB (2007). Suicide and suicidal-related behaviors among indigenous Pacific Islanders in the United States. Death Studies, 31(5), 479–501. 10.1080/07481180701244595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Ríos-Vargas M, & Albert NG (2011). The hispanic population: 2010. US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US …. [Google Scholar]

- Fortune S, Sinclair J, & Hawton K (2008). Adolescents’ views on preventing self-harm. A large community study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(2), 96–104. 10.1007/s00127-007-0273-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RD, Kupfer D, Frank E, Moore T, Beiser DG, & Boudreaux ED (2017). Development of a Computerized Adaptive Test Suicide Scale-The CAT-SS. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(9), 1376–1382. 10.4088/JCP.16m10922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Simon and schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez J, & Trickett EJ (2014). Collaborative measurement development as a tool in CBPR: Measurement development and adaptation within the cultures of communities. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(1–2), 112–124. 10.1007/s10464-014-9655-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greening L, Stoppelbein L, & Luebbe A (2010). The moderating effects of parenting styles on African-American and Caucasian children’s suicidal behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(4), 357–369. 10.1007/s10964-009-9459-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudiño OG, Lau AS, & Hough RL (2008). Immigrant Status, Mental Health Need, and Mental Health Service Utilization Among High-Risk Hispanic and Asian Pacific Islander Youth. Child & Youth Care Forum, 37(3), 139. 10.1007/s10566-008-9056-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbas LE, Guz S, Hausmann-Stabile C, Szlyk HS, & Zayas LH (2019). Trajectories of Well-Being Among Latina Adolescents Who Attempt Suicide: A Longitudinal Qualitative Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 29(12), 1766–1780. 10.1177/1049732319837541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbas LE, Hausmann-Stabile C, De Luca SM, Tyler TR, & Zayas LH (2015). An exploratory study of nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behaviors in adolescent Latinas. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(4), 302–314. 10.1037/ort0000073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guterman NB, Cameron M, & Staller K (2000). Definitional and measurement issues in the study of community violence among children and youths. Journal of Community Psychology, 28(6), 571–587. 10.1002/1520-6629 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill K, Van Eck K, Goklish N, Larzelere-Hinton F, & Cwik M (2020). Factor structure and validity of the SIQ-JR in a southwest American Indian tribe. Psychological Services, 17(2), 207–216. 10.1037/ser0000298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Jackson A, Hobfoll I, Pierce CA, & Young S (2002). The impact of communal-mastery versus self-mastery on emotional outcomes during stressful conditions: A prospective study of Native American women. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30(6), 853–871. 10.1023/A:1020209220214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday CE, Wynne M, Katz J, Ford C, & Barbosa-Leiker C (2018). A CBPR Approach to Finding Community Strengths and Challenges to Prevent Youth Suicide and Substance Abuse. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 29(1), 64–73. 10.1177/1043659616679234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, & Spicer P (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 747–770. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivey-Stephenson AZ, Crosby AE, Jack SPD, Haileyesus T, & Kresnow-Sedacca M-J (2017). Suicide Trends Among and Within Urbanization Levels by Sex, Race/Ethnicity, Age Group, and Mechanism of Death—United States, 2001-2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries (Washington, D.C.: 2002), 66(18), 1–16. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6618a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivey-Stephenson AZ, Demissie Z, Crosby AE, Stone DM, Gaylor E, Wilkins N, Lowry R, & Brown M (2020). Suicidal Ideation and Behaviors Among High School Students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Supplements, 69(1), 47–55. 10.15585/mmwr.su6901a6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe S, Baser RS, Neighbors HW, Caldwell CH, & Jackson JS (2009). 12-month and lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among black adolescents in the National Survey of American Life. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(3), 271–282. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318195bccf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline EA, Ortin-Peralta A, Polanco-Roman L, & Miranda R (2022). Association Between Exposure to Suicidal Behaviors and Suicide Attempts Among Adolescents: The Moderating Role of Prior Psychiatric Disorders. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 53(2), 365–374. 10.1007/s10578-021-01129-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert SF, Copeland-Linder N, & lalongo NS (2008). Longitudinal associations between community violence exposure and suicidality. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 43(4), 380–386. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, Jernewall NM, Zane N, & Myers HF (2002). Correlates of suicidal behaviors among Asian American outpatient youths. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 8(3), 199–213. 10.1037/1099-9809.8.3.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, & Wong YJ (2020). Racial/ethnic and gender differences in the antecedents of youth suicide. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 26(4), 532–543. 10.1037/cdp0000326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madubata I, Spivey LA, Alvarez GM, Neblett EW, & Prinstein MJ (2022). Forms of Racial/Ethnic Discrimination and Suicidal Ideation: A Prospective Examination of African-American and Latinx Youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 51(1), 23–31. 10.1080/15374416.2019.1655756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Alés G, Pamplin JR, Rutherford C, Gimbrone C, Kandula S, Olfson M, Gould MS, Shaman J, & Keyes KM (2021). Age, period, and cohort effects on suicide death in the United States from 1999 to 2018: Moderation by sex, race, and firearm involvement. Molecular Psychiatry, 26(7), 3374–3382. 10.1038/s41380-021-01078-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid RJ, Bombay A, McInnis OA, Humeny C, Matheson K, & Anisman H (2017). Suicide Ideation and Attempts among First Nations Peoples Living On-Reserve in Canada: The Intergenerational and Cumulative Effects of Indian Residential Schools. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 62(6), 422–430. 10.1177/0706743717702075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molock SD, Matlin S, Barksdale C, Puri R, & Lyles J (2008). Developing Suicide Prevention Programs for African American Youth in African American Churches. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 38(3), 323–333. 10.1521/suli.2008.38.3.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molock SD, Puri R, Matlin S, & Barksdale C (2006). Relationship Between Religious Coping and Suicidal Behaviors Among African American Adolescents. The Journal of Black Psychology, 32(3), 366–389. 10.1177/0095798406290466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell L, O’Donnell C, Wardlaw DM, & Stueve A (2004). Risk and resiliency factors influencing suicidality among urban African American and Latino youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 33(1–2), 37–49. 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000014317.20704.0b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olvera RL (2001). Suicidal ideation in Hispanic and mixed-ancestry adolescents. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 31(4), 416–427. 10.1521/suli.314.416.22049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opara I, Assan MA, Pierre K, Gunn JF, Metzger I, Hamilton J, & Arugu E (2020). Suicide among Black Children: An Integrated Model of the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide and Intersectionality Theory for Researchers and Clinicians. Journal of Black Studies, 51(6), 611–631. 10.1177/0021934720935641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortin A, Miranda R, Polanco-Roman L, & Shaffer D (2017). Parent-Adolescent Acculturation Gap and Suicidal Ideation among Adolescents from an Emergency Department. Archives of Suicide Research: Official Journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research, 22(4), 529–541. 10.1080/13811118.2017.1372828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S-Y, & Park S-Y (2020). Immigration and Language Factors Related to Depressive Symptoms and Suicidal Ideation in Asian American Adolescents and Young Adults. Community Mental Health Journal, 56(1), 139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña JB, Kuhlberg JA, Zayas LH, Baumann AA, Gulbas L, Hausmann-Stabile C, & Nolle AP (2011). Familism, family environment, and suicide attempts among Latina youth. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 41(3), 330–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanco-Roman L, & Miranda R (2022). A cycle of exclusion that impedes suicide research among racial and ethnic minority youth. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 52(1), 171–174. 10.1111/sltb.12752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan S, Arora P, Cheng B, Khoo, Olivia, & Verdeli H (2022). Suicidality and Exposure to School-Based Violence Among a Nationally Representative Sample of Asian American and Pacific Islander Adolescents. School Psychology Review, 51(3), 304–314. [Google Scholar]

- Rathod S, Pinninti N, Irfan M, Gorczynski P, Rathod P, Gega L, & Naeem F (2017). Mental Health Service Provision in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Health Services Insights, 10, 1178632917694350. 10.1177/1178632917694350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM, & Mazza JJ (1994). Suicide and Suicidal Behaviors in Children and Adolescents. In Reynolds WM & Johnston HF (Eds.), Handbook of Depression in Children and Adolescents (pp. 525–580). Springer US. [Google Scholar]

- Riina EM, Martin A, Gardner M, & Brooks-Gunn J (2013). Context matters: Links between neighborhood discrimination, neighborhood cohesion and African American adolescents’ adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(1), 136–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M (2006). Implications of resilience concepts for scientific understanding. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094, 1–12. 10.1196/annals.1376.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, & Szapocznik J (2010). Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. The American Psychologist, 65(4), 237–251. 10.1037/a0019330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheftall AH, & Miller AB (2021). Setting a Ground Zero Research Agenda for Preventing Black Youth Suicide. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(9), 890–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheftall AH, Vakil F, Ruch DA, Boyd RC, Lindsey MA, & Bridge JA (2022). Black Youth Suicide: Investigation of Current Trends and Precipitating Circumstances. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 61(5), 662–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva C, & Van Orden KA (2018). Suicide among Hispanics in the United States. Current Opinion in Psychology, 22, 44–49. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman MM, Berman AL, Sanddal ND, O’Carroll PW, & Joiner TE Jr (2007). Rebuilding the tower of babel: A revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors Part 1: Background, rationale, and methodology. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 37(3), 248–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standley CJ (2022). Expanding our paradigms: Intersectional and socioecological approaches to suicide prevention. Death Studies, 46(1), 224–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart EA, Baumer EP, Brunson RK, & Simons RL (2009). Neighborhood Racial Context and Perceptions of Police-Based Racial Discrimination Among Black Youth*. Criminology, 47(3), 847–887. 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00159.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Yan Cheng JK, Saad CS, & Chu JP (2012). Asian American mental health: A call to action. The American Psychologist, 67(7), 532–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tynes BM, Willis HA, Stewart AM, & Hamilton MW (2019). Race-Related Traumatic Events Online and Mental Health Among Adolescents of Color. The Journal of Adolescent Healt, 65(3), 371–377. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, & Hill NE (2020). Ethnic–Racial Socialization in the Family: A Decade’s Advance on Precursors and Outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 244–271. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood JM, Brener N, Thornton J, Harris WA, Bryan LN, Shanklin SL, Deputy N, Roberts AM, Queen B, Chyen D, Whittle L, Lim C, Yamakawa Y, Leon-Nguyen M, Kilmer G, Smith-Grant J, Demissie Z, Jones SE, Clayton H, & Dittus P (2020). Overview and Methods for the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System—United States, 2019. MMWR Supplements, 69(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungemack JA, & Guarnaccia PJ (1998). Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts among Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans and Cuban Americans. Transcultural Psychiatry, 35(2), 307–327. 10.1177/136346159803500208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. (2020, April 29). The Hispanic Population in the United States: 2019. Census.Gov. [Google Scholar]

- Vawda NBM, Milburn NG, Steyn R, & Zhang M (2017). The development of a screening tool for the early identification of risk for suicidal behavior among students in a developing country. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 9(3), 267–273. 10.1037/tra0000229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M-T, Henry DA, Smith LV, Huguley JP, & Guo J (2020). Parental ethnic-racial socialization practices and children of color’s psychosocial and behavioral adjustment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Psychologist, 75(1), 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SL, & Polaha J (2014). Rural parents’ perceived stigma of seeking mental health services for their children: Development and evaluation of a new instrument. Psychological Assessment, 26(3), 763–773. 10.1037/a0036571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WISQARS. (2021, December 2). CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

- Woods-Jaeger B, Briggs EC, Gaylord-Harden N, Cho B, & Lemon E (2021). Translating cultural assets research into action to mitigate adverse childhood experience-related health disparities among African American youth. The American Psychologist, 76(2), 326–336. 10.1037/amp0000779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C-Y, Lee M-B, Liao S-C, Chan C-T, & Chen C-Y (2021). Adherence to World Health Organization guideline on suicide reporting by media in Taiwan: A surveillance study from 2010 to 2018. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 120(1 Pt 3), 609–620. 10.1016/j.jfma.2020.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, & Pilat AM (2008). Suicidal behavior inLatinas: Explanatory cultural factors and implications for intervention. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 38(3), 334–342. 10.1521/suli.2008.38.3.334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman GM, & Messner SF (2013). Individual, family background, and contextual explanations of racial and ethnic disparities in youths’ exposure to violence. American Journal of Public Health, 103(3), 435–442. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]