Abstract

Background

Chronic stress poses risks for physical and mental well-being. Stress management interventions have been shown to be effective, and stress management apps (SMAs) might help to transfer strategies into everyday life.

Objective

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the quality and characteristics of SMAs to give potential users or health professionals a guideline when searching for SMAs in common app stores.

Methods

SMAs were identified with a systematic search in the European Google Play Store and Apple App Store. SMAs were screened and checked according to the inclusion criteria. General characteristics and quality were assessed by 2 independent raters using the German Mobile Application Rating Scale (MARS-G). The MARS-G assesses quality (range 1 to 5) on the following four dimensions: (1) engagement, (2) functionality, (3) esthetics, and (4) information. In addition, the theory-based stress management strategies, evidence base, long-term availability, and common characteristics of the 5 top-rated SMAs were assessed and derived.

Results

Of 2044 identified apps, 121 SMAs were included. Frequently implemented strategies (also in the 5 top-rated SMAs) were psychoeducation, breathing, and mindfulness, as well as the use of monitoring and reminder functions. Of the 121 SMAs, 111 (91.7%) provided a privacy policy, but only 44 (36.4%) required an active confirmation of informed consent. Data sharing with third parties was disclosed in only 14.0% (17/121) of the SMAs. The average quality of the included apps was above the cutoff score of 3.5 (mean 3.59, SD 0.50). The MARS-G dimensions yielded values above this cutoff score (functionality: mean 4.14, SD 0.47; esthetics: mean 3.76, SD 0.73) and below this score (information: mean 3.42, SD 0.46; engagement: mean 3.05, SD 0.78). Most theory-based stress management strategies were regenerative stress management strategies. The evidence base for 9.1% (11/121) of the SMAs could be identified, indicating significant group differences in several variables (eg, stress or depressive symptoms) in favor of SMAs. Moreover, 38.0% (46/121) of the SMAs were no longer available after a 2-year period.

Conclusions

The moderate information quality, scarce evidence base, constraints in data privacy and security features, and high volatility of SMAs pose challenges for users, health professionals, and researchers. However, owing to the scalability of SMAs and the few but promising results regarding their effectiveness, they have a high potential to reach and help a broad audience. For a holistic stress management approach, SMAs could benefit from a broader repertoire of strategies, such as more instrumental and mental stress management strategies. The common characteristics of SMAs with top-rated quality can be used as guidance for potential users and health professionals, but owing to the high volatility of SMAs, enhanced evaluation frameworks are needed.

Keywords: stress management, mobile app, mHealth, mobile health, quality assessment, review, evidence base, availability

Introduction

Stress is a public health problem that poses high risks for physical and mental well-being and is increasing in industrial societies where individuals are exposed to complex demands at work and in daily life [1-5]. The results of an American survey revealed that 75% of the participants felt significantly stressed [6], and a representative sample of the German population showed a point prevalence of perceived high chronic stress of 11% [1]. There are multiple reasons for the broad impact of stress as it affects many dimensions, such as cognition (eg, negative attributional style), affect (eg, affective dysregulation, such as increase in anxiety), physiology (eg, dysregulation of the endocrine response system), and behavior (eg, harmful behavioral changes, such as smoking or physical inactivity) [3]. As a result, chronic stress causes a higher risk for various somatic diseases and mental disorders, such as gastric ulcers, migraine, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and depression [3,5,7-11]. In addition to the substantial impact on health, work-related stress results in high costs for society, especially through productivity-related losses [12].

Due to these negative consequences, several stress management strategies have been developed and evaluated over the past decades [13,14]. Most of them refer to transactional stress models in which stress reactions are mainly determined by a subjective interpretation and the types of coping strategies employed [13-16]. Even though “stress management” is a widely and variably used term [17], Kaluza [13] proposed three categories of strategies: (1) instrumental stress management strategies with a focus on preventing and reducing stress in everyday life (eg, self-management or seeking support); (2) mental stress management strategies aiming at changing personal stress amplifiers (eg, acceptance or gratitude); and (3) regenerative stress management strategies aiming at recovery after stress exposure (eg, relaxation techniques or health behavior) [17-19]. Thereby, effective stress management seems to be characterized by a broad repertoire and a balance between instrumental, mental, and regenerative strategies [15]. Interventions use a variety of these different strategies and are often delivered in a group setting [17,18]. In particular, cognitive or behavioral-based interventions for stress management (which typically include all 3 categories of strategies) have been shown to be effective for reducing stress in different settings (eg, the occupational setting; Cohen d=1.16, 95% CI 0.46-1.87 [20]) and for different target groups (eg, university students; standardized mean difference=−0.77, 95% CI −0.97 to −0.57 [21]). The same is true for mindfulness-based stress reduction in healthy individuals [22-24] (eg, Hedges g=0.53, 95% CI 0.41-0.64 [22]). Relaxation training (with a focus on regenerative strategies) has been shown to be effective in healthy individuals [24] and in occupational settings (Cohen d=0.50, 95% CI 0.31-0.69 [20]) but appears to be inferior to cognitive-behavioral interventions [20]. Implementing previously learned health-related strategies in daily life is essential for their short- and long-term health benefits [25]. Internet- and mobile-based health interventions can help to integrate stress management strategies into daily routines and to overcome the barriers of face-to-face interventions, such as limited accessibility, location, time, and high costs [26,27]. As a result, the relevance of mobile phones for monitoring and delivering health interventions has increased over the last decade [27]. From 2013 to 2018, the number of downloaded health apps per year increased from 1.7 to 4.1 billion worldwide [28]. Regarding stress management apps (SMAs), about 6% of an American sample reported that they already use SMAs regularly and about 50% could imagine using them in the future [29]. An observational study showed that compared to a website, delivering a stress-management intervention via an app could offer the added benefit of more frequent use and access to more intervention content [30].

Accordingly, there is a broad and growing body of SMA research. Reviews already exist; however, they all focus on specific aspects and some might be outdated. Pre-existing SMA reviews focus on content alone [31,32], content in combination with transparency and functionality [33], efficacy [34], gamification elements [35], persuasive and behavior change strategies [36], or quality of apps, with a focus exclusively on mindfulness apps [37]. Regarding content, it was shown that mindfulness and meditation were the most commonly used strategies in the reviewed SMAs (34% to 78% of all apps included these strategies) [31,33,34], followed by breathing [31,33] or goal setting [34]. Further common strategies were personalization and self-monitoring, while social support strategies were rarely used [36]. The implementation of gamification elements is relatively scarce (on average 0.5 elements per app) [35]. Concerning the evidence base, Lau et al [34] revealed that among more than 1000 screened apps for well-being and stress management, only 2% were scientifically evaluated. The 2 studies that looked at data privacy and security features, such as privacy policy, contact information, and disclosures, revealed that only half of these criteria could be met on average [33]. In addition, most of the evaluated apps showed a lack of data privacy and security [37]. This confirms the results of other health, wellness, and medicine-related apps (eg, smoking cessation and diabetes) [38-40], showing major privacy and security risks, missing transparency, or data sharing with third parties, even when they were accredited [41].

Considering the quality of SMAs, only one of the existing reviews (which was exclusively performed for mindfulness apps and not for SMAs in general) [37] employed a valid scientific measure, that is, the Mobile Application Rating Scale (MARS), which is an instrument for assessing app quality on multiple dimensions [42,43]. This is of relevance as user star ratings and app store descriptions can be manipulated in favor of commercial interests [33].

Another challenge for users and health professionals who are seeking apps for long-term use, as well as for researchers aiming to present the most recent state of research, is the high volatility of apps [44,45]. In a study considering mental health apps, only 50% of the search results were available at the end of a 9-month period [44]. Considering the excessive supply of health apps in app stores, their high update rate, and their uncertain long-term availability, as well as the current lack of transparency of app quality [46], the question arises as to which SMAs should be used and recommended.

In light of all these gaps and issues, the aim of this study was to systematically search for SMAs, to assess their quality on multiple dimensions in a scientific manner, and to give a comprehensive overview of SMAs concerning their general characteristics, theory-based stress management strategies, evidence base, and long-term availability. A further aim was to inform potential users or health professionals about common characteristics that might indicate high quality of SMAs. The following research questions were addressed:

What are the general characteristics of SMAs, such as descriptive information, technical aspects, strategies, and functions?

What is the quality of SMAs regarding multiple dimensions (ie, engagement, functionality, esthetics, and information)?

Which theory-based stress management strategies are used in SMAs?

What is the evidence base of SMAs?

How reliable are SMAs in terms of their long-term availability?

What are the common characteristics of SMAs with top-rated quality?

Methods

Overview

This study involved a systematic search and assessment of the quality and characteristics of SMAs. It was registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) of the Center for Open Science [47].

Search Strategy and Procedure

The search terms were generated through a 3-step process. First, a narrative literature search was conducted to collect terms and keywords that were used in studies focusing on SMA interventions for the general population. Second, relevant search terms were identified based on interest group interviews with 3 psychotherapists and 3 potential SMA users. Third, the identified search terms from the literature search and results of the interest group interviews were merged, leading to the following search terms: “stress,” “stress management,” “stress reduction,” “stress prevention,” “stress coach,” “stress recovery,” “relaxation,” and “relaxation training.” An automated search using these search terms (in English and German language) was conducted in the European Apple App Store and Google Play Store with a search engine (web crawler). It was developed as part of the Mobile Health App Database Project [48], and it automatically extracts information, such as app name, description, and user rating, from the stores (for further details, please see [49]).

Apps from both app stores were identified and listed in a central database. Duplicates were automatically removed. In the first step and based on the description in the app stores, apps were screened for the following inclusion criteria: (1) the word “stress” was included in the title or in the app store description; (2) the app was developed for adults in the general population without mental or somatic disorders; (3) the focus of the app was primarily on stress management; (4) at least two different stress management strategies were applied with the aim of including apps that potentially take a holistic approach to stress management; (5) the app could be used without further equipment, devices, or programs; (6) the app was free of cost in the basic version; and (7) the app was provided in German or English language. In the second step, the app was downloaded and rechecked for criteria 1 to 7. Apps that did not work after the download were excluded.

Data Collection of General Characteristics and Quality Assessment

The general characteristics and quality of each SMA were collected and rated between March and May 2020 by 2 independent raters (EM, SP, Hannah Besel, RW, or VH) with the German Mobile Application Rating Scale (MARS-G) [42]. All raters had a psychology or sports science degree and completed an online training, which included the following components: (1) background information on the development of the MARS-G; (2) description of the dimensions and items; (3) application instructions; and (4) an exercise example [50]. Subsequently, 3 SMAs were assessed per rater in order to compare and discuss the results and to ensure a common standard as well as high data quality. According to the standardized procedure, each rater had to test an app for at least 15 minutes. Data collection and quality assessment, including the actual average time spent per rating, have been fully documented.

General Characteristics

General characteristics were mainly based on the classification section of the original MARS and MARS-G [42,43] and included (1) descriptive information on the app (ie, app name, URL, platform, user star rating, full version price, content-related app category, declared aims of the app, theoretical background, and certification); (2) technical aspects (eg, links to social media or type of support); (3) strategies (eg, relaxation or goal setting); and (4) functions (eg, feedback or reminder).

Owing to the high relevance of data privacy and security, the list of the MARS-G [42] has been supplemented with 7 additional features (ie, passive informed consent; complex passwords; anonymization or pseudonymization; creation of an access token; automatic display of the privacy policy; permanent availability of the privacy policy; and transparency regarding the right of withdrawal [51,52]). The privacy policy of each included SMA was reviewed against the listed features. It was assessed whether information was provided for each feature (“yes” or “no”), but not whether it was technically and legally realized and complied with by the respective providers.

Quality Assessment

The multidimensional quality evaluation based on the MARS-G [42] comprised 4 subscales: user engagement (5 items: entertainment, interest, customization, interactivity, and target group), functionality (4 items: performance, ease of use, navigation, and gestural design), esthetics (3 items: layout, graphics, and visual appeal), and information quality (7 items: accuracy of app description, goals, quality of information, quantity of information, quality of visual information, credibility, and evidence base). For the interpretation, the cutoff score of 3.5 (indicating above-average quality) defined by Terhorst et al [53] was used.

Additionally, the subjective quality (4 items: expected use frequency within 1 year, willingness to pay for the app, willingness to recommend the app, and subjective star rating) and the perceived impact on the user (6 items: awareness, knowledge, attitudes, intention to change, help-seeking, and behavioral change) were assessed. All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=inadequate, 2=poor, 3=acceptable, 4=good, and 5=excellent). The MARS is a well-validated instrument [43,54]. The validation of the German version also yielded excellent internal consistency (ω=0.84, 95% CI 0.77-0.88) and high levels of interrater reliability (interclass correlation [ICC]=0.83, 95% CI 0.82-0.85 [42]).

Theory-Based Stress Management Strategies

To depict the variety of existing stress management strategies in more detail, we developed a list of theory-based stress management strategies [13,31]. This list contains 23 instrumental, mental, and regenerative stress management strategies (see Textbox 1). Some of the included theory-based strategies (eg, breathing, hypnosis, and mindfulness) overlapped with the strategies covered in the MARS-G. The assessment of theory-based stress management strategies was performed for each SMA by 2 independent raters.

List of theory-based stress management strategies (adapted from Kaluza [13] and Christmann et al [31]).

Instrumental stress management strategies

Enhancing professional competencies (eg, learning)

Seeking support (eg, network)

Developing social-communicative skills (eg, self-assertion)

Self-management

Mental stress management strategies

Accepting reality (also included in the German Mobile Application Rating Scale [MARS-G])

Seeing difficulties as challenges (not as threats)

Changing personal stress amplifiers

Self-efficacy

Regenerative stress management strategies

Acupressure

Autogenic training (the MARS-G includes the category “relaxation,” which is differentiated in more detail here)

Biofeedback

Breathing (also included in the MARS-G)

Euthymic methods

Food or nutrition

Guided imagination or visualization

Hypnosis or self-hypnosis (also included in the MARS-G)

Meditation or mindfulness (also included in the MARS-G)

Music

Muscle relaxation (the MARS-G includes the category “relaxation,” which is differentiated in more detail here)

Physical stress relief techniques

Self-massage

Sounds

Sport (also included in the MARS-G)

Evidence Base of Included SMAs and Long-Term Availability

All included SMAs were unsystematically searched in a common web search engine for scholarly literature by applying the app name and screening the first pages of the results. Information on study design, app usage in weeks, sample and target groups, age, gender, measurement time points, measured variables, and main results were assessed from the studies found (with the exception of pilot studies).

In terms of long-term availability, all included SMAs were searched again in the app stores in August 2022. It was checked whether the app was still available (on the original platform), when the last update was made, and whether the basic version was still free of cost.

Characteristics of the 5 Top-Rated SMAs

Owing to the multitude of information, a concise overview of the common characteristics of the 5 top-rated SMAs (based on the MARS-G overall quality score) has been provided. This overview contains information on quality ratings, technical aspects, strategies and functions (all derived from the MARS-G), theory-based stress management strategies, evidence base, and long-term availability.

Data Analyses

To ensure consistency between raters, the ICC (2-way mixed) was calculated according to the report by Koo and Li [55]. An ICC below 0.50 is considered poor, 0.51 to 0.75 is moderate, 0.76 to 0.89 is good, and above 0.90 is excellent [56]. For all descriptive data (such as aims, background, and data security features), frequency and percentage were calculated. The mean score and standard deviation have been presented for each dimension of the MARS-G. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 21; IBM Corp).

Results

Search Results

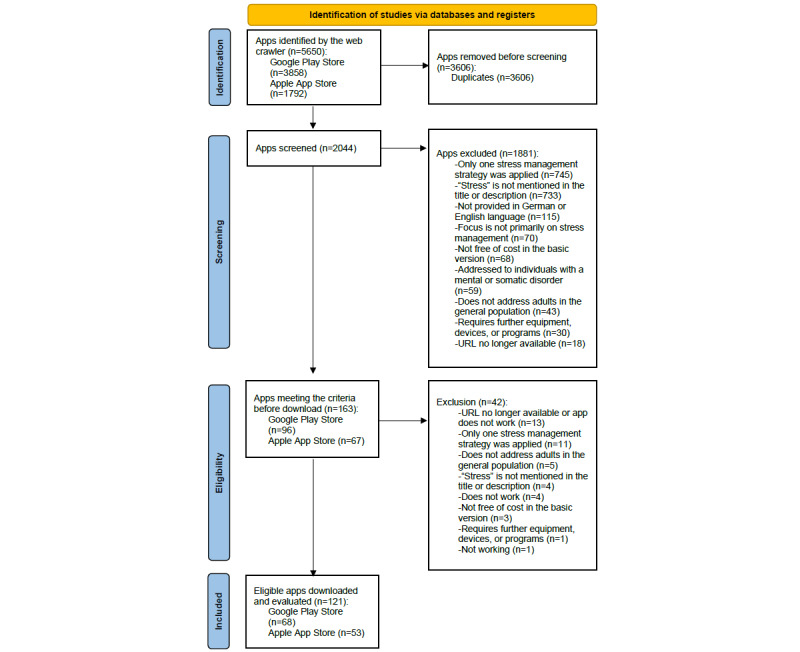

The web crawler identified 5650 potential SMAs (Google Play Store, n=3580; Apple App Store, n=1792). After removing duplicates, 2044 apps were screened. This screening resulted in 163 apps, of which 121 were eligible for inclusion after the download (Figure 1 [57]). On average, each SMA was used and evaluated for 30 minutes by each rater (mean 30.2, SD 4.0 minutes).

Figure 1.

Flowchart according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement 2020.

General Characteristics and Quality Rating

Descriptive Information

Of the 121 included SMAs, 68 (56.2%) were derived from the Google Play Store and 53 (43.8%) from the Apple App Store. The user star rating in the app stores could be identified for 96 (79.3%) apps. The mean user star rating was 4.27 (SD 0.56), and the number of ratings per app ranged from 1 to 126,183. Of all rated SMAs, 83 (68.6%) could be upgraded to a premium version (from 1 month [with costs between 0.99 EUR and 15.99 EUR] up to a permanent upgrade [with costs between 1.09 EUR and 449.99 EUR]; 1 EUR=1.1197 USD). Regarding content-related categories, most apps were listed under “health and fitness” (107/121, 88.4%). Further assigned categories were “lifestyle” (6/121, 5.0%), “medicine” (6/121, 5.0%), and others (3/121, 2.5%; including “learning,” “entertainment,” and “audio/music”). According to the description, all apps aimed at reducing stress (121/121, 100%). Further aims were improvement of well-being (113/121, 93.4%), reduction of anxiety (90/121, 74.4%), improvement of physical health (50/121, 41.3%), and emotion regulation (58/121, 47.9%). Some SMAs focused on the reduction of depressive symptoms (33/121, 27.3%), behavioral change (21/121, 17.4%), and entertainment (3/121, 2.5%). Moreover, 81 (66.9%) apps reported additional goals, such as relaxation, increasing motivation and focus, improvement of sleep, and concentration or self-awareness. The most often assigned theoretical background was third-wave behavioral therapy (106/121, 87.6%), followed by behavioral therapy (30/121, 24.8%) and cognitive behavioral therapy (24/121, 19.8%). Overall, more than 100 SMAs (111/121, 91.7%) were developed with a commercial background, 5 (4.1%) were developed by a nongovernmental organization, and only few SMAs were developed by a university (2/121, 1.7%) or a governmental institution (1/121, 0.8%). No SMA was certified according to the European Union Medical Device Regulation [58].

Technical Aspects

Data exchange with other users (eg, via social media) was possible in 40 (33.1%) SMAs, and an app community existed in 20 (16.5%) SMAs. SMAs were unguided (74/121, 61.2%), technically guided (70/121, 57.9%), asynchronously guided by humans (4/121, 3.3%), or synchronously guided by humans (1/121, 0.8%). All data privacy and security features are presented in Table 1. The 3 most common features were provision of privacy policy (111/121, 91.7%), provision of contact details or imprint (111/121, 91.7%), and passive informed consent (80/121, 66.1%).

Table 1.

Frequency of declared data privacy and security features based on the German Mobile Application Rating Scale [42].a

| Data privacy and security feature | Number of apps that specify this feature (N=121), n (%) |

| Provision of a privacy policy | 111 (91.7) |

| Contact or imprint | 111 (91.7) |

| Passive informed consentb | 80 (66.1) |

| Automatic display of the privacy policyb | 76 (62.8) |

| Allows password protection | 74 (61.1) |

| Requires login | 66 (54.5) |

| Security of data transfer | 64 (52.9) |

| Permanent availability of the privacy policyb | 55 (45.5) |

| Active confirmation of informed consent | 44 (36.4) |

| Financial background/conflict of interest | 42 (34.7) |

| Transparency regarding the right of withdrawalb | 34 (28.1) |

| Creation of an access tokenb | 26 (21.5) |

| Complex passwordsb | 25 (20.7) |

| Data sharing with third parties | 17 (14.0) |

| Security strategies in case of device loss | 17 (14.0) |

| Emergency function | 8 (6.6) |

| Anonymization or pseudonymizationb | 3 (2.5) |

| Place of storage | 2 (1.7) |

aA more descriptive presentation of the data can be found in Multimedia Appendix 1.

bAdditional feature that has been added to the original list.

Strategies

As shown in Table 2, more than half of all 121 SMAs included the strategies breathing (95/121, 78.5%), relaxation (94/121, 77.7%), mindfulness or gratitude (91/121, 75.2%), information or education (83/121, 68.6%), and tips or advice (70/121, 57.9%).

Table 2.

Frequency of the implemented strategies according to the German Mobile Application Rating Scale.a

| Strategy | Number of apps that include the strategy (N=121), n (%) |

| Breathing | 95 (78.5) |

| Relaxation | 94 (77.7) |

| Mindfulness/gratitude | 91 (75.2) |

| Information, education | 83 (68.6) |

| Tips, advice | 70 (57.9) |

| Acceptance | 49 (40.5) |

| Physical exercises | 38 (31.4) |

| Gamification | 33 (27.3) |

| Skills, training | 30 (24.8) |

| Resource orientation | 24 (19.8) |

| Goal setting | 22 (18.2) |

| Serious games | 5 (4.1) |

| Hypnosis | 4 (3.3) |

| Exposure | 0 (0.0) |

aA more descriptive presentation of the data can be found in Multimedia Appendix 2.

Functions

The most included function was monitoring or tracking (78/121, 64.5%), followed by reminder (76/121, 62.8%), data collection (49/121, 40.5%), feedback (48/121, 39.7%), and tailored intervention or real-time feedback (22/121, 18.2%).

Quality Rating

The agreement between raters was good (ICC=0.82, 95% CI 0.81-0.82). The mean overall quality score for the SMAs was 3.59 (SD 0.50; range 2.13-4.37), indicating acceptable to good quality exceeding the cutoff score of 3.5. The mean scores of the different dimensions were as follows: engagement, 3.05 (SD 0.78; range 1.40-4.60); functionality, 4.14 (SD 0.47; range 2.63-5.00); esthetics, 3.76 (SD 0.73; range 1.50-5.00); and information, 3.42 (SD 0.46; range 1.00-4.00). The mean score for subjective quality was 2.53 (SD 0.78; range 1.00-4.00) and that for perceived impact on the user was 2.64 (SD 0.77; range 1.25-4.25). The quality ratings of all SMAs can be found in Multimedia Appendix 3.

Theory-Based Stress Management Strategies

The most common theory-based stress management strategies were meditation or mindfulness (80/121, 66.1%), breathing (61/121, 50.4%), music (31/121, 25.6%), guided imagination or visualization (26/121, 21.5%), accepting reality (25/121, 20.7%), and enhancing professional competencies (21/121, 17.4%). In the 121 SMAs, theory-based stress management strategies were included 355 times. The most implemented strategies were regenerative stress management strategies (on average, each strategy [n=15] was mentioned 17 times and implemented 248 times, ie, 70%), followed by mental stress management strategies (on average, each strategy [n=4] was mentioned 14 times and implemented 57 times, ie, 16%) and instrumental stress management strategies (on average, each strategy [n=4] was mentioned 13 times and implemented 50 times, ie, 14%). Table 3 shows the frequencies of the investigated theory-based stress management strategies.

Table 3.

| Theory-based stress management strategy | Number of apps that include the strategy (N=121), n (%) | |

| Regenerative stress management strategy |

|

|

|

|

Meditation or mindfulnessb | 80 (66.1) |

|

|

Breathingb | 61 (50.4) |

|

|

Music | 31 (25.6) |

|

|

Guided imagination or visualization | 26 (21.5) |

|

|

Sounds | 20 (16.5) |

|

|

Food and nutrition | 8 (6.6) |

|

|

Muscle relaxation | 7 (5.8) |

|

|

Sportb | 3 (2.5) |

|

|

Techniques for physical stress relief | 3 (2.5) |

|

|

Autogenic training | 3 (2.5) |

|

|

Self-massage | 2 (1.7) |

|

|

Hypnosis or self-hypnosisb | 2 (1.7) |

|

|

Euthymic methods | 1 (0.8) |

|

|

Acupressure | 1 (0.8) |

|

|

Biofeedback | 0 (0.0) |

| Mental stress management strategy |

|

|

|

|

Accepting realityb | 25 (20.7) |

|

|

Seeing difficulties as challenges (not as threats) | 17 (14.0) |

|

|

Self-efficacy | 8 (6.6) |

|

|

Changing personal stress amplifiers | 7 (5.8) |

| Instrumental stress management strategy |

|

|

|

|

Enhancing professional competencies | 21 (17.4) |

|

|

Self-management | 18 (14.9) |

|

|

Developing social-communicative skills | 6 (5.0) |

|

|

Seeking support | 5 (4.1) |

aA more descriptive presentation of the data can be found in Multimedia Appendix 4.

bTheory-based stress management strategy that is also included in the German Mobile Application Rating Scale.

Evidence Base and Long-Term Availability

Scientific evaluations could be found in 11 (9.1%) of the 121 apps. Study designs varied and included randomized controlled trials (n=5), a partially randomized trial (n=1), a panel study (n=1), and pilot studies (n=3). One app was tested for its quality, and the results were summarized in a published conference paper (n=1). Target groups were university students (n=5), the general population (n=2), employed individuals (n=1), caregivers (n=1), adults with mild to moderate anxiety or depression (n=1), and nurses (n=1). Different health outcome variables were studied. In the 5 randomized controlled trials, significant group differences at postintervention in favor of the app could be found for the variables stress (n=2), self-efficacy (n=2), mindfulness (n=2), anxiety symptoms (n=4), and depression symptoms (n=4). Details of the evaluations (excluding the pilot studies and the conference paper) can be found in Multimedia Appendix 5 [59-77].

Two years after screening, 46 (38.0%) of the 121 SMAs were no longer available in the 2 app stores. Three apps did not exist anymore in English and were only available in another language (German). Nine apps were only available through other platforms that had less stringent review procedures compared with the official app stores. Among the 75 SMAs that were still accessible, 10 apps now had costs even in the basic version. Of the 121 SMAs, 46 (38.0%) had their last update in 2022 and 11 (9.1%) had not been updated since 2020.

Characteristics of the 5 Top-Rated SMAs

The 5 apps with the highest overall MARS-G ratings are presented in Table 4. None of these apps was developed by a public institution (such as a government or university). However, in all apps, it was emphasized that they were developed by different experts (such as psychologists, psychotherapists, and neuroscientist), or researchers with experience in mindfulness, meditation, or coaching. Furthermore, 3 of these 5 SMAs were part of scientific studies (study design: randomized controlled trial). All apps integrated different forms of psychoeducation and information via text or audio, provided advice, and implemented breathing and mindfulness. Monitoring or tracking and reminders were also included in all apps. Additional theory-based stress management strategies were guided imagination or visualization and music. All apps were technically guided. Moreover, 3 of the 5 apps were tailored to the users’ needs based on a screening at the beginning or provided real-time feedback. Additionally, 1 SMA included messenger coaching and a contact list with therapists in different US states. Furthermore, 3 of the 5 apps offered an app community. All apps provided a specific login area (including password), privacy policy, and contact information or imprint. Moreover, 2 of the 5 apps offered an emergency function.

Table 4.

Overview of the 5 top-rated apps.

| Variable | Appa | |||||

| App 1 | App 2b | App 3 | App 4 | App 5 | ||

| Overall quality (MARS-Gc) | 4.36 | 4.22 | 4.21 | 4.19 | 4.16 | |

| Quality dimensions (MARS-G) |

|

|||||

|

|

Engagement | 4.30 | 4.10 | 3.80 | 4.00 | 4.30 |

|

|

Functionality | 4.63 | 4.38 | 3.50 | 4.75 | 4.25 |

|

|

Esthetics | 4.50 | 4.83 | 4.83 | 4.17 | 4.50 |

|

|

Information | 4.00 | 3.57 | 3.71 | 3.86 | 3.57 |

| Technical aspects (MARS-G)d |

|

|||||

|

|

Privacy and security featurese | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

|

|

Technical guidance | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

Tailored interventions, real time feedback | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

|

|

App community | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Strategies (MARS-G)d |

|

|||||

|

|

Information, education | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

Tips, advice | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

Breathingf | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

Mindfulness, gratitudef | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

Relaxationf | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

|

|

Acceptancef | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Functions (MARS-G)d |

|

|||||

|

|

Monitoring, tracking | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

Reminder | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

|

|

Data collection | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

|

|

Automated feedback | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Theory-based stress management strategiesg |

|

|||||

|

|

Guided imagination, visualization (RSMSh) | ✓ | ✓ | |||

|

|

Music (RSMS) | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Evidence basei | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Long-term availability |

|

|||||

|

|

App still available after 2 yearsj | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Year of the last update | 2022 | 2022 | 2022 | 2020 | 2022 | |

aApp 1, Happify: bei Ärger und Stress (English translation: Happify: Anger and Stress); App 2, Sanvello: Stress & Anxiety Help; App 3, Headspace: Meditation & Schlaf (English translation: Headspace: Meditation & Sleep); App 4, go4health – gesund leben (English translation: go4health – living healthy); App 5, BamBu: Meditation & Achtsamkeit (English translation: BamBu: Meditation & Mindfulness).

bName of this app after the second search in August 2022: “Sanvello: Anxiety and Depression.” The app may no longer meet inclusion criterion 2 (“the app was developed for adults in the general population without mental or somatic disorders”). At the time of the screening process in 2020, we listed this app as “Sanvello: Stress & Anxiety Help,” and it met the inclusion criteria.

cMARS-G: German Mobile Application Rating Scale.

dWith the exception of “privacy and security features,” all general characteristics of the categories “technical aspects,” “strategies,” and “functions” of the MARS-G are listed, which were included in at least three of the top 5 apps.

eThe number of statements made regarding 19 possible security features is provided.

fStrategies that were included in the MARS-G and also in the list of theory-based stress management strategies.

gAll theory-based stress management strategies (according to Kaluza [13] and Christmann et al [31]) are listed, when they were included in at least two of the top 5 apps. Theory-based stress management strategies that are already listed in the MARS-G strategies are not listed again (breathing [regenerative stress management strategy], relaxation [regenerative stress management strategy], mindfulness [regenerative stress management strategy], and acceptance [mental stress management strategy]).

hRSMS: regenerative stress management strategy.

iAll studies were randomized controlled trials.

jApp 4 was still available but only in the Google Play Store and was not available anymore in the Apple App Store, where it was found in 2020.

Discussion

Principal Findings

This systematic app search and standardized multidimensional assessment aimed to evaluate the general characteristics, quality, theory-based stress management strategies, evidence base, and long-term availability of SMAs. Furthermore, characteristics that might indicate high quality were derived from the 5 top-rated SMAs.

General Characteristics

Learning and maintaining stress management strategies requires regular engagement for not only changing the stress-enhancing cognitions and emotions, but also changing behavior [14]. Most of the included SMAs support this learning process by providing information on the background of the intervention and thus about stress management, tracking progress, or the use of reminder functions. Especially, the frequent presence of reminder functions was found to be similar in previous reviews [78]. A subgroup analysis of apps for mental health problems showed a moderate effect of reminder functions in reducing stress levels [79]. However, information on background, and tracking and reminder functions have been shown to improve long-term engagement within health apps [80], which might improve effectiveness through more intense and long-term usage. Similar to the results of Lau et al [34], most SMAs in this study were oriented toward self-help as merely 5 SMAs included the possibility to communicate synchronously (1/121, 0.8%) or asynchronously (4/121, 3.3%) with practitioners. This might be subject to change in future app development as a meta-analysis showed that professional guidance within mental health apps could significantly reduce stress levels compared with unguided apps (g=0.57 vs g=0.24) [79].

Support in terms of app communities was implemented in 16.5% (20/121) of the included SMAs. This is a positive trend compared with earlier findings showing only 4% of all included mindfulness-based apps providing this kind of support [78]. Since the availability of a community has beneficial effects on user engagement [80] and social support can positively influence the stress response [81], this seems to be a desirable trend.

Even though chronic stress is a major public health problem [1,9,12], only 3 SMAs were developed by institutions in the public sector (eg, universities or health authorities) and no SMA was officially certified (eg, according to the European Union Medical Device Regulation). This, together with the finding that only 5 SMAs were evaluated in randomized controlled trials, could indicate that thoroughly developed and evaluated apps might not find their way into the most popular app stores.

This study also focused on the declaration of the privacy and safety features within each identified SMA. The high percentage of SMAs providing a privacy policy (111/121, 91.7%) is promising. However, for 63.6% (77/121) of SMAs, no active confirmation of informed consent was required, and for 71.9% (87/121) of SMAs, there was no transparency regarding the right of withdrawal of informed consent. Data sharing with third parties was disclosed in the privacy policies of 17 (14.0%) SMAs. Regarding the actual practice of data security measures, Huckvale et al [40] showed that user data of health apps (depression and smoking cessation) have been shared with third parties, even without the necessary disclosure in the privacy policy. These results might be transferable to other health apps, including SMAs. Since the lack of data security is a common reason for user dissatisfaction with health apps and leads to the app being discontinued [82], improving data security measures may lead to increased engagement.

Quality

The 121 included SMAs showed an acceptable to good overall quality (mean score 3.59, SD 0.50). The scores of the dimensions functionality and esthetics were above the cutoff value of 3.5. The scores of the dimensions engagement (mean 3.05, SD 0.78) and information (mean 3.42, SD 0.46) did not exceed this cutoff score. Overall quality was similar to that of other (mental) health apps, such as mindfulness apps (mean score 3.66, SD 0.48 [37]), physical activity apps (mean score 3.60, SD 0.59 [83]), depression apps (mean score 3.01, SD 0.56 [53]), or apps for posttraumatic stress disorder (mean score 3.36, SD 0.65 [84]). The rating below the cutoff score in the information dimension was also consistent with the findings of previous systematic reviews [33,34,37,83]. One explanation is the limited evidence base of SMAs. Only 9% of the included SMAs were scientifically evaluated. The rating below the cutoff score in the dimension engagement implies that the content and functions of SMAs might currently not be sufficient to bind the users in the long term. Implementation of diverse content or the possibility of personalization could help as these aspects are particularly relevant for the users of mental health apps [82].

Theory-Based Stress Management Strategies

The examination of 3 types of theory-based stress management strategies resulted in 2.9 strategies per app. This is similar to the results in the study by Christmann et al [31], who reported 2.8 stress management strategies per app in their content analysis. Three of the four most implemented strategies are similar to the present results: meditation or mindfulness, breathing, and music (all categorized as regenerative stress management strategies). The results showed that instrumental and mental stress management strategies, which tend to be designed for prevention, are implemented less often than regenerative stress management strategies, which tend to be used for calming down after exposure to stress [13]. Therefore, the increased implementation of instrumental and mental strategies should be considered for a holistic approach to stress management in SMAs that seem to be relevant for effective prevention and coping with stress [13,15].

Evidence Base and Long-Term Availability

For 11 of the 121 (9.1%) SMAs, a scientific evaluation could be found. Moreover, 5 (4.1%) of the SMAs were evaluated in randomized controlled trials and 1 (0.8%) in a partially randomized controlled trial showing improvement in different outcomes such as stress, self-efficacy, mindfulness, anxiety, and depressive symptoms [59-65]. Previous reviews of mental health apps for other target groups included similar or even fewer efficacy studies [37,53,83-86]. This might be explained by the high rate of updates and the high volatility of apps [34,44,45], which could also be confirmed in this study. Of 163 apps, 13 (8.0%) became unavailable during the app rating period, and only 62.0% (75/121) of all SMAs were still available after 2 years, with most of them (64/75, 85.3%) being updated. This poses a great challenge for not only users and health professionals, but also researchers regarding the use, recommendation, and evaluation of SMAs or other health apps [44]. In addition, the trustworthiness of the information about the content and functions within app descriptions is questionable. In this study, 163 apps were included based on the information in the description. However, 24 (14.7%) apps had to be excluded after downloading because the actual content did not meet the previously described content. This confirms the findings of Coulon et al [33], who found that 33% of SMAs did not contain the content advertised in their descriptions. Potential users must check any eligible app for accuracy after overcoming the hurdles of downloading the app, installing the app, and, if required, registering an account. New evaluation frameworks are needed and do exist, but in a systematic review, it was concluded that none out of 45 evaluation frameworks for medical apps was rated as being fully suitable [87]. A different approach to deal with the fast-moving nature of apps has been proposed by a group of international and diverse stakeholders [88]. They harmonized elements of different frameworks into 5 priority levels (background info, data privacy and security, app effectiveness, user experience and adherence, and data integration) with the aim to enable informed app decision-making rather than to constantly evaluate the apps.

Overview of the Implications of the 5 Top-Rated SMAs

By presenting SMAs with top-rated MARS-G quality together with their characteristics in a comparative overview, a broad information and decision basis can be provided for researchers, health professionals, and users. The 5 top-rated SMAs showed both common characteristics and consistencies with existing evidence. Three of the 11 evidence-based apps were rated in the top 5 SMAs in terms of quality. Furthermore, some strategies, functions, and technical aspects previously shown to be effective in reducing stress or shown to improve engagement were found among the top-rated apps, such as providing psychoeducation [80], including breathing [89] and mindfulness [64], providing monitoring and tracking [80], using reminders [79], tailoring the content to the users’ needs [90,91], and providing technical guidance and a privacy policy [82]. Across all SMAs and within the 5 top-rated SMAs, there were some aspects not covered by the MARS-G (eg, theory-based stress management strategies such as guided imagination, visualization, or music). This demonstrates the value of the overview of the top-rated SMAs (eg, compared with simple app rankings), in particular when special weight is given to certain aspects or app characteristics. In addition, the joint presentation of MARS-G content and additional uncovered aspects reveals certain revision potentials of the MARS-G.

Limitations

There were some limitations. First, owing to the rapid development of the app market and the short lifespan of apps, the content and quality of the reviewed SMAs may have already changed, some SMAs may no longer be available, or new SMAs may have been launched. However, this seems to be a challenge in general for health technology evaluation [44,87], and a screenshot of the current status might help to derive implications for improving SMA quality and effectiveness, and improving the evaluation frameworks for apps in the future. Second, the search results per search term were limited to 200 results and screening was based on the titles and descriptions of the apps. It is possible that apps that met the inclusion criteria were overlooked because relevant information was not provided or the word “stress” was not present in the titles or descriptions. Furthermore, only SMAs that were free of cost or provided a free basic version were evaluated. Further evaluation of paid (full version) SMAs could show whether there is a difference in quality, declaration of data privacy and security features, or access to professional support. Third, there was only a descriptive evaluation (not a technical evaluation; eg, for data privacy issues), and no conclusions about the overall effectiveness of the included SMAs could be drawn. Fourth, the number of SMAs including “breathing” as a strategy differed in the MARS rating and in the assessment of theory-based stress management strategies. Therefore, it should be emphasized that the discriminant differentiation of the related and partially overlapping concepts or strategies of “mindfulness” and “breathing” cannot be assessed conclusively (especially considering that “breathing” can also be practiced as a concrete strategy within the context of mindfulness). However, the fact that “breathing” and “mindfulness” were listed in the top 3 strategies remains unchanged. Finally, the review and evaluation of each app took an average of 30 minutes. It is possible that specific content could not be discovered owing to the limited amount of time spent evaluating each app.

Conclusion

In this comprehensive review including a systematic search and a standardized multidimensional assessment, the overall quality of 121 SMAs was rated as acceptable to good, with a rating below the cutoff score in the dimensions of information quality and engagement. The top-rated apps included psychoeducation, breathing and mindfulness, monitoring, reminder functions, tailoring, technical guidance, and a privacy policy. However, even though most SMAs provided a privacy policy, there is still a need for better personal data protection and transparency of data processing, such as the use of a password or information about data sharing with third parties. Theory-based strategies were mostly regenerative stress management strategies. For a holistic stress management approach, SMAs could benefit from the integration of more mental and instrumental stress management strategies. The evidence base for 11 (9.1%) of the 121 included apps showed that SMAs can reduce stress and improve further outcome variables such as self-efficacy, mindfulness, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. Moreover, SMAs have high scalability. Therefore, they have a high potential to reach and help a broad audience coping with increasing stress and demands in their work and daily living. However, the rather moderate information quality, the scarce evidence base of the included SMAs, and the fact that many SMAs changed or were unavailable after a 2-year period pose challenges for users and health professionals who are searching for high-quality apps that are effective and for long-term use. The common characteristics of SMAs with top-rated quality and evidence base of SMAs can be used as guidance for this search or even for SMA development. In addition, it is difficult for researchers to keep up to date with the latest research in this volatile field and provide potential users with helpful information. Enhanced evaluation frameworks are needed that might complement or even advance the idea of a continuous effectiveness and quality assessment to an approach that enables informed decision-making.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Hannah Besel and Joshua Kannapin for assisting in the project. The study was self-funded (University of Freiburg). The article processing charge was partly funded by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Freiburg.

Abbreviations

- ICC

interclass correlation

- MARS

Mobile Application Rating Scale

- MARS-G

German Mobile Application Rating Scale

- SMA

stress management app

Frequency of declared data privacy and security features based on the German Mobile Application Rating Scale presented as a bar graph. The asterisk (*) indicates additional features that have been added to the original list.

Frequency of the implemented strategies according to the German Mobile Application Rating Scale presented as a bar graph.

Quality ratings of all included stress management apps.

Theory-based stress management strategies according to Kaluza [13] and Christmann et al [31] presented as a bar graph. Regenerative stress management strategies (RSMSs) are indicated with black, mental stress management strategies (MSMSs) are indicated with vertical lines, and instrumental stress management strategies (ISMSs) are indicated with horizontal lines. The asterisk (*) indicates theory-based stress management strategies that are also included in the German Mobile Application Rating Scale.

Overview of stress management apps with an evidence base.

Data Availability

Data will be made available to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal, not already covered by other researchers. All requests should be directed to the corresponding author. Data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement. Provision of data is subject to data security regulations. Support depends on available resources.

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: SP, EM, EMM, and HB designed the trial and initiated this study. SP, EM, RW, and VH conducted the German Mobile Application Rating Scale (MARS-G) ratings. SP supervised all MARS-G ratings. YT and DS conducted the statistical analyses. JS was involved as an expert in the field of stress research. MW was involved in the conceptualization and drafting of the manuscript and in the second assessment as part of an update in August 2022. SP wrote the first draft. All authors revised the manuscript, and read and approved the final report.

Conflicts of Interest: HB and EMM received payments for talks and workshops in the context of e-mental health. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Hapke U, Maske UE, Scheidt-Nave C, Bode L, Schlack R, Busch MA. Chronischer Stress bei Erwachsenen in Deutschland [Chronic stress among adults in Germany: results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1)] Bundesgesundheitsblatt. 2013;56(5-6):749–754. doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1690-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yaribeygi H, Panahi Y, Sahraei H, Johnston TP, Sahebkar A. The impact of stress on body function: A review. EXCLI J. 2017;16:1057–1072. doi: 10.17179/excli2017-480. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28900385 .2017-480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen S, Murphy MLM, Prather AA. Ten Surprising Facts About Stressful Life Events and Disease Risk. Annu Rev Psychol. 2019;70:577–597. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102857. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/29949726 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvey SB, Modini M, Joyce S, Milligan-Saville JS, Tan L, Mykletun A, Bryant RA, Christensen H, Mitchell PB. Can work make you mentally ill? A systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occup Environ Med. 2017;74(4):301–310. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2016-104015.oemed-2016-104015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneiderman N, Ironson G, Siegel SD. Stress and health: psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:607–628. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144141. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/17716101 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Psychological Association. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2015. [2023-07-11]. Stress in America: Paying with our health. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2014/stress-report.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Everly GS, Lating JM. A Clinical Guide to the Treatment of the Human Stress Response. New York, NY: Springer; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu M, Li N, Li WA, Khan H. Association between psychosocial stress and hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Res. 2017;39(6):573–580. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2017.1317904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergmann N, Gyntelberg F, Faber J. The appraisal of chronic stress and the development of the metabolic syndrome: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Endocr Connect. 2014;3(2):R55–R80. doi: 10.1530/EC-14-0031. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24743684 .EC-14-0031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammen CL. Stress and depression: old questions, new approaches. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015;4:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.12.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swanson SA, Zeng Y, Weeks M, Colman I. The contribution of stress to the comorbidity of migraine and major depression: results from a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(3):e002057. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002057. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=23474788 .bmjopen-2012-002057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hassard J, Teoh KRH, Visockaite G, Dewe P, Cox T. The cost of work-related stress to society: A systematic review. J Occup Health Psychol. 2018;23(1):1–17. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000069.2017-14292-001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaluza G. Calm and Confident Under Stress: The Stress Competence Book: Recognize, Understand, Manage Stress. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaluza G, Chevalier A. Stressbewältigungstrainings für Erwachsene [Stress management training for adults] In: Fuchs R, Gerber M, editors. Handbuch Stressregulation und Sport. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2018. pp. 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazarus RS, Launier R. Stressbezogene Transaktionen zwischen Person und Umwelt [Stress-related transactions between person and environment] In: Nitsch JR, editor. Stress. Theorien, Untersuchungen, Maßnahmen. Bern, Stuttgart, Wien: Verlag Hans Huber; 1981. pp. 213–259. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ong L, Linden W, Young S. Stress management: what is it? J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(1):133–137. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00128-4.S0022399903001284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy LR. Stress management in work settings: a critical review of the health effects. Am J Health Promot. 1996;11(2):112–135. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-11.2.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaluza G. Gelassen und sicher im Stress: Das Stresskompetenz-Buch: Stress erkennen, verstehen, bewältigen [The Stress Competence Book: Recognize, Understand, Manage Stress] Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richardson KM, Rothstein HR. Effects of occupational stress management intervention programs: a meta-analysis. J Occup Health Psychol. 2008;13(1):69–93. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.13.1.69.2008-00533-007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regehr C, Glancy D, Pitts A. Interventions to reduce stress in university students: a review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2013;148(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.026.S0165-0327(12)00779-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khoury B, Sharma M, Rush SE, Fournier C. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2015;78(6):519–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009.S0022-3999(15)00080-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharma M, Rush SE. Mindfulness-based stress reduction as a stress management intervention for healthy individuals: a systematic review. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2014 Oct;19(4):271–86. doi: 10.1177/2156587214543143.2156587214543143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: a review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(5):593–600. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rippe JM. Lifestyle Medicine: The Health Promoting Power of Daily Habits and Practices. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2018;12(6):499–512. doi: 10.1177/1559827618785554. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/30783405 .10.1177_1559827618785554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ebert DD, Van Daele T, Nordgreen T, Karekla M, Compare A, Zarbo C, Brugnera A, Øverland S, Trebbi G, Jensen KL, Kaehlke F, Baumeister H. Internet- and Mobile-Based Psychological Interventions: Applications, Efficacy, and Potential for Improving Mental Health. European Psychologist. 2018;23(2):167–187. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baig MM, GholamHosseini H, Connolly MJ. Mobile healthcare applications: system design review, critical issues and challenges. Australas Phys Eng Sci Med. 2015;38(1):23–38. doi: 10.1007/s13246-014-0315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anzahl der Downloads von mHealth-Apps weltweit in den Jahren 2013 bis 2018. Statista. 2018. [2021-08-02]. https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/695434/umfrage/anzahl-der-weltweiten-downloads-von-mhealth-apps/

- 29.Percentage of U.S. adults that use apps for stress relief as of 2017, by gender. Statista. 2017. [2021-08-04]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/699523/us-adults-that-use-apps-to-relieve-stress-by-gender/

- 30.Morrison LG, Geraghty AWA, Lloyd S, Goodman N, Michaelides DT, Hargood C, Weal M, Yardley L. Comparing usage of a web and app stress management intervention: An observational study. Internet Interv. 2018;12:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2018.03.006. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214-7829(18)30006-X .S2214-7829(18)30006-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christmann CA, Hoffmann A, Bleser G. Stress Management Apps With Regard to Emotion-Focused Coping and Behavior Change Techniques: A Content Analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(2):e22. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.6471. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2017/2/e22/ v5i2e22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blázquez Martín D, De La Torre I, Garcia-Zapirain B, Lopez-Coronado M, Rodrigues J. Managing and Controlling Stress Using mHealth: Systematic Search in App Stores. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(5):e111. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.8866. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2018/5/e111/ v6i5e111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coulon SM, Monroe CM, West DS. A Systematic, Multi-domain Review of Mobile Smartphone Apps for Evidence-Based Stress Management. Am J Prev Med. 2016 Jul;51(1):95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.01.026.S0749-3797(16)00052-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lau N, O'Daffer A, Colt S, Yi-Frazier JP, Palermo TM, McCauley E, Rosenberg AR. Android and iPhone Mobile Apps for Psychosocial Wellness and Stress Management: Systematic Search in App Stores and Literature Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(5):e17798. doi: 10.2196/17798. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/5/e17798/ v8i5e17798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoffmann A, Christmann CA, Bleser G. Gamification in Stress Management Apps: A Critical App Review. JMIR Serious Games. 2017;5(2):e13. doi: 10.2196/games.7216. https://games.jmir.org/2017/2/e13/ v5i2e13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alhasani M, Mulchandani D, Oyebode O, Baghaei N, Orji R. A Systematic and Comparative Review of Behavior Change Strategies in Stress Management Apps: Opportunities for Improvement. Front Public Health. 2022;10:777567. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.777567. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/35284368 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schultchen D, Terhorst Y, Holderied T, Stach M, Messner E, Baumeister H, Sander LB. Stay Present with Your Phone: A Systematic Review and Standardized Rating of Mindfulness Apps in European App Stores. Int J Behav Med. 2021;28(5):552–560. doi: 10.1007/s12529-020-09944-y. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33215348 .10.1007/s12529-020-09944-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blenner SR, Köllmer M, Rouse AJ, Daneshvar N, Williams C, Andrews LB. Privacy Policies of Android Diabetes Apps and Sharing of Health Information. JAMA. 2016;315(10):1051–1052. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.19426.2499265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grundy Q, Chiu K, Bero L. Commercialization of User Data by Developers of Medicines-Related Apps: a Content Analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(12):2833–2841. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05214-0. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31529374 .10.1007/s11606-019-05214-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huckvale K, Torous J, Larsen ME. Assessment of the Data Sharing and Privacy Practices of Smartphone Apps for Depression and Smoking Cessation. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(4):e192542. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2542. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31002321 .2730782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huckvale K, Prieto JT, Tilney M, Benghozi P, Car J. Unaddressed privacy risks in accredited health and wellness apps: a cross-sectional systematic assessment. BMC Med. 2015;13:214. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0444-y. https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-015-0444-y .10.1186/s12916-015-0444-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Messner E, Terhorst Y, Barke A, Baumeister H, Stoyanov S, Hides L, Kavanagh D, Pryss R, Sander L, Probst T. The German Version of the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS-G): Development and Validation Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(3):e14479. doi: 10.2196/14479. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/3/e14479/ v8i3e14479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, Zelenko O, Tjondronegoro D, Mani M. Mobile app rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(1):e27. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3422. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2015/1/e27/ v3i1e27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larsen ME, Nicholas J, Christensen H. Quantifying App Store Dynamics: Longitudinal Tracking of Mental Health Apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4(3):e96. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.6020. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2016/3/e96/ v4i3e96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McIlroy S, Ali N, Hassan AE. Fresh apps: an empirical study of frequently-updated mobile apps in the Google play store. Empir Software Eng. 2015;21(3):1346–1370. doi: 10.1007/s10664-015-9388-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albrecht UV. Chancen und Risiken von Gesundheits-Apps (CHARISMHA); engl. Chances and Risks of Mobile Health Apps (CHARISMHA) Technische Universität Braunschweig. 2016. [2023-07-11]. https://leopard.tu-braunschweig.de/receive/dbbs_mods_00060000 .

- 47.Paganini S, Meier P, Messner E, Sander L, Baumeister H, Terhorst Y. A Systematic Review of Content and Quality of Apps for Stress Management. OSF. 2019. [2023-07-11]. https://osf.io/8vg5c .

- 48.Mobile Health App Database. [2023-07-15]. https://mhad.science/en/

- 49.Stach M, Kraft R, Probst T, Messner E, Terhorst Y, Baumeister H, Schickler M, Reichert M, Sander L, Pryss R. Mobile Health App Database - A Repository for Quality Ratings of mHealth Apps. 33rd International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS); July 28-30, 2020; Rochester, MN, USA. 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MARS - Mobile Anwendungen Rating Skala. YouTube. [2023-07-15]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5vwMiCWC0Sc .

- 51.Security tips. Android Developers. [2023-05-07]. https://developer.android.com/training/articles/security-tips .

- 52.Orientierungshilfe zu den Datenschutzanforderungen an App-Entwickler und App-Anbieter [Guidance on data protection requirements for app developers and app providers] Düsseldorfer Kreis - Bayerisches Landesamt für Datenschutzaufsicht. [2023-07-11]. https://datenschutz.hessen.de/sites/datenschutz.hessen.de/files/2022-08/oh_appentwicklung.pdf .

- 53.Terhorst Y, Rathner E, Baumeister H, Sander L. «Hilfe aus dem App-Store?»: Eine systematische Übersichtsarbeit und Evaluation von Apps zur Anwendung bei Depressionen. Verhaltenstherapie. 2018;28(2):101–112. doi: 10.1159/000481692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Terhorst Y, Philippi P, Sander LB, Schultchen D, Paganini S, Bardus M, Santo K, Knitza J, Machado GC, Schoeppe S, Bauereiß N, Portenhauser A, Domhardt M, Walter B, Krusche M, Baumeister H, Messner E. Validation of the Mobile Application Rating Scale (MARS) PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0241480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241480. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241480 .PONE-D-20-14930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koo TK, Li MY. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15(2):155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/27330520 .S1556-3707(16)00015-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research: applications to practice. Hoboken, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. http://www.bmj.com/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=33782057 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Regulation 2017/745 of the European parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on medical devices. Official Journal of the European Union. 2017. [2023-07-11]. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32017R0745 .

- 59.Parks AC, Williams AL, Tugade MM, Hokes KE, Honomichl RD, Zilca RD. Testing a scalable web and smartphone based intervention to improve depression, anxiety, and resilience: A randomized controlled trial. Intnl. J. Wellbeing. 2018;8(2):22–67. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v8i2.745. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nagel A, John D, Scheder A, Kohls N. Klassisches oder digitales Stressmanagement im Setting Hochschule? Präv Gesundheitsf. 2018;14(2):138–145. doi: 10.1007/s11553-018-0670-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Möltner H, Leve J, Esch T. [Burnout Prevention and Mobile Mindfulness: Evaluation of an App-Based Health Training Program for Employees] Gesundheitswesen. 2018;80(3):295–300. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-114004. http://www.thieme-connect.com/DOI/DOI?10.1055/s-0043-114004 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moberg C, Niles A, Beermann D. Guided Self-Help Works: Randomized Waitlist Controlled Trial of Pacifica, a Mobile App Integrating Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Mindfulness for Stress, Anxiety, and Depression. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(6):e12556. doi: 10.2196/12556. https://www.jmir.org/2019/6/e12556/ v21i6e12556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Richardson B, Little K, Teague S, Hartley-Clark L, Capic T, Khor S, Cummins RA, Olsson CA, Hutchinson D. Efficacy of a Smartphone App Intervention for Reducing Caregiver Stress: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(7):e17541. doi: 10.2196/17541. https://mental.jmir.org/2020/7/e17541/ v7i7e17541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Flett JAM, Conner TS, Riordan BC, Patterson T, Hayne H. App-based mindfulness meditation for psychological distress and adjustment to college in incoming university students: a pragmatic, randomised, waitlist-controlled trial. Psychol Health. 2020;35(9):1049–1074. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2019.1711089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bakker D, Rickard N. Engagement with a cognitive behavioural therapy mobile phone app predicts changes in mental health and wellbeing: MoodMission. Australian Psychologist. 2020;54(4):245–260. doi: 10.1111/ap.12383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Flett JAM, Hayne H, Riordan BC, Thompson LM, Conner TS. Mobile Mindfulness Meditation: a Randomised Controlled Trial of the Effect of Two Popular Apps on Mental Health. Mindfulness. 2018;10(5):863–876. doi: 10.1007/s12671-018-1050-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Best NI, Durham CF, Woods-Giscombe C, Waldrop J. Combating Compassion Fatigue With Mindfulness Practice in Military Nurse Practitioners. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2020;16(5):e57–e60. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2020.02.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee RA, Jung ME. Evaluation of an mHealth App (DeStressify) on University Students' Mental Health: Pilot Trial. JMIR Ment Health. 2018;5(1):e2. doi: 10.2196/mental.8324. https://mental.jmir.org/2018/1/e2/ v5i1e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Levin ME, Hicks ET, Krafft J. J Am Coll Health. 2022 Jan;70(1):165–173. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2020.1728281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hoffmann A, Faust-Christmann CA, Zolynski G, Bleser G. Gamification of a Stress Management App: Results of a User Study. In: Marcus A, Wang W, editors. Design, User Experience, and Usability. Application Domains. HCII 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 11585. Cham: Springer; 2019. pp. 303–313. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang E, Schamber E, Meyer R, Gold J. Happier Healers: Randomized Controlled Trial of Mobile Mindfulness for Stress Management. J Altern Complement Med. 2018;24(5):505–513. doi: 10.1089/acm.2015.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Howells A, Ivtzan I, Eiroa-Orosa FJ. Putting the ‘app’ in Happiness: A Randomised Controlled Trial of a Smartphone-Based Mindfulness Intervention to Enhance Wellbeing. J Happiness Stud. 2014;17(1):163–185. doi: 10.1007/s10902-014-9589-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wen L, Sweeney TE, Welton L, Trockel M, Katznelson L. Encouraging Mindfulness in Medical House Staff via Smartphone App: A Pilot Study. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(5):646–650. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0768-3.10.1007/s40596-017-0768-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Morrison Wylde C, Mahrer N, Meyer R, Gold J. Mindfulness for Novice Pediatric Nurses: Smartphone Application Versus Traditional Intervention. J Pediatr Nurs. 2017;36:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2017.06.008.S0882-5963(16)30278-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bennike IH, Wieghorst A, Kirk U. Online-based Mindfulness Training Reduces Behavioral Markers of Mind Wandering. J Cogn Enhanc. 2017;1(2):172–181. doi: 10.1007/s41465-017-0020-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Economides M, Martman J, Bell M, Sanderson B. Improvements in Stress, Affect, and Irritability Following Brief Use of a Mindfulness-based Smartphone App: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Mindfulness (N Y) 2018;9(5):1584–1593. doi: 10.1007/s12671-018-0905-4. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/30294390 .905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rosen K, Paniagua S, Kazanis W, Jones S, Potter J. Quality of life among women diagnosed with breast Cancer: A randomized waitlist controlled trial of commercially available mobile app-delivered mindfulness training. Psychooncology. 2018;27(8):2023–2030. doi: 10.1002/pon.4764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mani M, Kavanagh DJ, Hides L, Stoyanov SR. Review and Evaluation of Mindfulness-Based iPhone Apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(3):e82. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4328. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2015/3/e82/ v3i3e82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Linardon J, Cuijpers P, Carlbring P, Messer M, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M. The efficacy of app-supported smartphone interventions for mental health problems: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):325–336. doi: 10.1002/wps.20673. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31496095 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Szinay D, Jones A, Chadborn T, Brown J, Naughton F. Influences on the Uptake of and Engagement With Health and Well-Being Smartphone Apps: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(5):e17572. doi: 10.2196/17572. https://www.jmir.org/2020/5/e17572/ v22i5e17572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ditzen B, Heinrichs M. Psychobiology of social support: the social dimension of stress buffering. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2014;32(1):149–162. doi: 10.3233/RNN-139008.M0228K0TM4T20210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alqahtani F, Orji R. Insights from user reviews to improve mental health apps. Health Informatics J. 2020;26(3):2042–2066. doi: 10.1177/1460458219896492. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1460458219896492?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub0pubmed . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Paganini S, Terhorst Y, Sander LB, Catic S, Balci S, Küchler A, Schultchen D, Plaumann K, Sturmbauer S, Krämer L, Lin J, Wurst R, Pryss R, Baumeister H, Messner E. Quality of Physical Activity Apps: Systematic Search in App Stores and Content Analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021;9(6):e22587. doi: 10.2196/22587. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2021/6/e22587/ v9i6e22587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sander LB, Schorndanner J, Terhorst Y, Spanhel K, Pryss R, Baumeister H, Messner E. 'Help for trauma from the app stores?' A systematic review and standardised rating of apps for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2020;11(1):1701788. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2019.1701788. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32002136 .1701788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Terhorst Y, Messner E, Schultchen D, Paganini S, Portenhauser A, Eder A, Bauer M, Papenhoff M, Baumeister H, Sander LB. Systematic evaluation of content and quality of English and German pain apps in European app stores. Internet Interv. 2021;24:100376. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100376. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2214-7829(21)00016-6 .S2214-7829(21)00016-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Knitza J, Tascilar K, Messner E, Meyer M, Vossen D, Pulla A, Bosch P, Kittler J, Kleyer A, Sewerin P, Mucke J, Haase I, Simon D, Krusche M. German Mobile Apps in Rheumatology: Review and Analysis Using the Mobile Application Rating Scale (MARS) JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(8):e14991. doi: 10.2196/14991. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2019/8/e14991/ v7i8e14991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Moshi MR, Tooher R, Merlin T. Suitability of current evaluation frameworks for use in the health technology assessment of mobile medical applications: A systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2018;34(5):464–475. doi: 10.1017/S026646231800051X.S026646231800051X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Henson P, David G, Albright K, Torous J. Deriving a practical framework for the evaluation of health apps. The Lancet Digital Health. 2019;1(2):e52–e54. doi: 10.1016/s2589-7500(19)30013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hopper SI, Murray SL, Ferrara LR, Singleton JK. Effectiveness of diaphragmatic breathing for reducing physiological and psychological stress in adults: a quantitative systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2019;17(9):1855–1876. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Meyerowitz-Katz G, Ravi S, Arnolda L, Feng X, Maberly G, Astell-Burt T. Rates of Attrition and Dropout in App-Based Interventions for Chronic Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9):e20283. doi: 10.2196/20283. https://www.jmir.org/2020/9/e20283/ v22i9e20283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Alqahtani F, Meier S, Orji R. Personality-based approach for tailoring persuasive mental health applications. User Model User-Adap Inter. 2021;32(3):253–295. doi: 10.1007/s11257-021-09289-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials